Abstract

Service robots are playing an increasingly relevant role in society. Humanoid robots, especially those equipped with social skills, could be used to address a number of people’s daily needs. Knowing how these robots are perceived and potentially accepted by ordinary users when used in common tasks and what the benefits brought are in terms, e.g., of tasks’ effectiveness, is becoming of primary importance. This paper specifically focuses on receptionist scenarios, which can be regarded as a good benchmark for social robotics applications given their implications on human-robot interaction. Precisely, the goal of this paper is to investigate how robots used as direction-giving systems can be perceived by human users and can impact on their wayfinding performance. A comparative analysis is performed, considering both solutions from the literature and new implementations which use different types of interfaces to ask for and give directions (voice, in-the-air arm pointing gestures, route tracing) and various embodiments (physical robot, virtual agent, interactive audio-map). Experimental results showed a marked preference for a physical robot-based system showing directions on a map over solutions using gestures, as well as a positive effect of embodiment and social behaviors. Moreover, in the comparison, physical robots were generally preferred to virtual agents.

1. Introduction

Continuous advancements in the field of robotics are paving the way for a significant expansion of application fields for such a technology [1]. In particular, service robots are becoming ever more commonplace in a number of daily life activities. Commercial products and research prototypes include robots used in home automation settings [2,3,4], entertainment [5,6], education [7,8], and elderly assistance applications [9,10], to name a few.

In a context in which robots are expected to be more and more integrated into human environments to assist and communicate with common people, humanoid robots featuring social interaction behaviors will reasonably play a key role, since their aspect and functionality may contribute at making them more acceptable compared to other robots [11].

Though a number of robots with human features are already available, research activities are needed to adjust their behavior based on the specific tasks they are expected to carry out in the selected context, in order to ensure consistency with end-users’ needs [12]. Moreover, since these robots are going to operate in human environments, special attention has to be devoted to develop their social attitudes and make their interaction capabilities as natural as possible [11].

This paper focuses on a specific application scenario that can be referred to as “robotic reception”, in which a robot can be used to assist people by giving directions and helping them to find the places of interest.

A robotic receptionist can be regarded both as a Socially Interactive Robot (SIR), a definition coined by Fong et al. to refer to robots equipped with social interaction skills as main features [13], and as a Socially Assistive Robot (SAR), since it aims to provide assistance to human users through social interaction [14].

A number of works have already explored the robotic receptionist domain and, more in general, systems for direction-giving and wayfinding tasks. Different solutions have been developed, using, e.g., audio feedback, deictic (in the following often intended as arm pointing) gestures, route tracing on a map, socially interactive embodied (physical or virtual) systems, unembodied systems without social interaction skills (like audio-maps), etc. However, an approach that can be regarded as the ultimate solution to perform the considered task has not been identified yet.

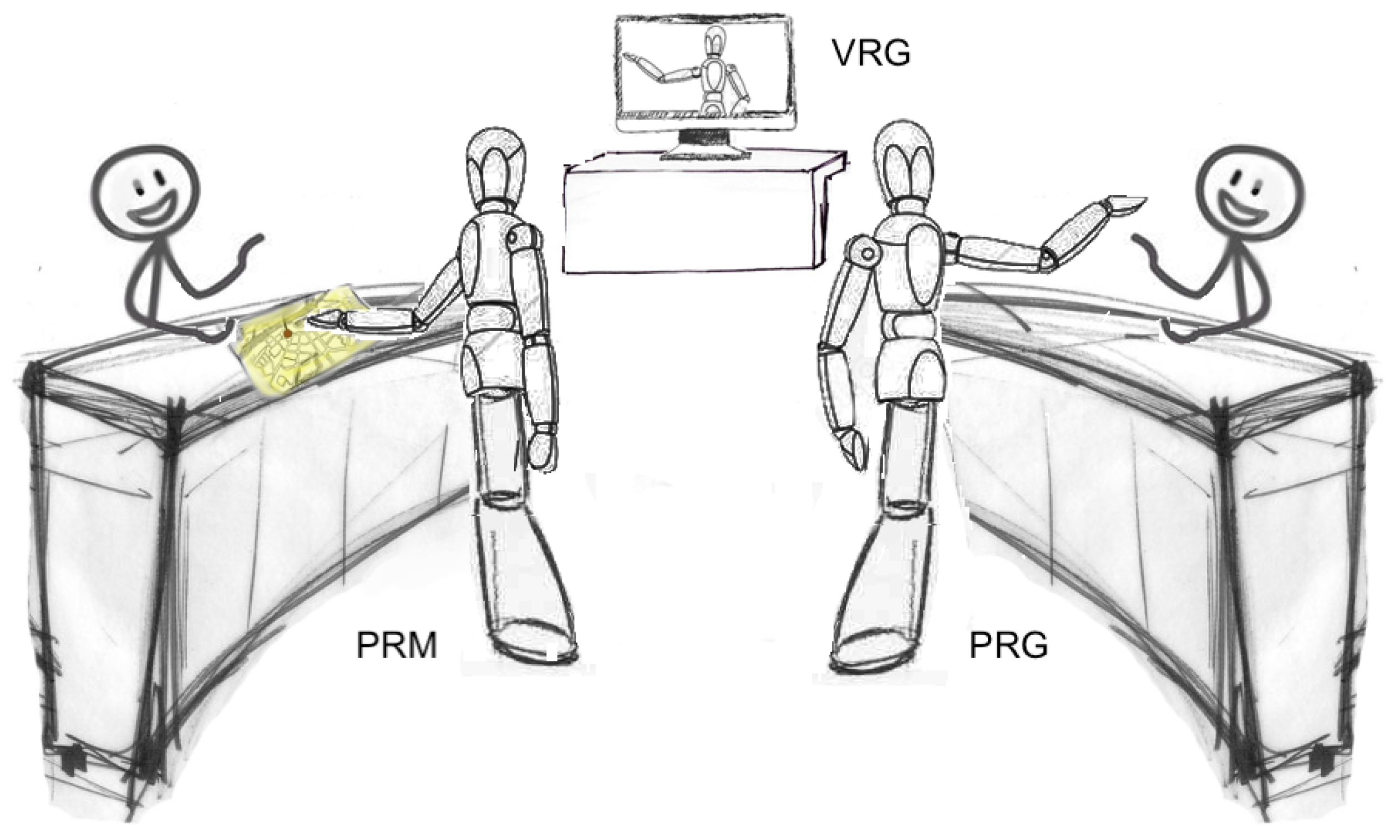

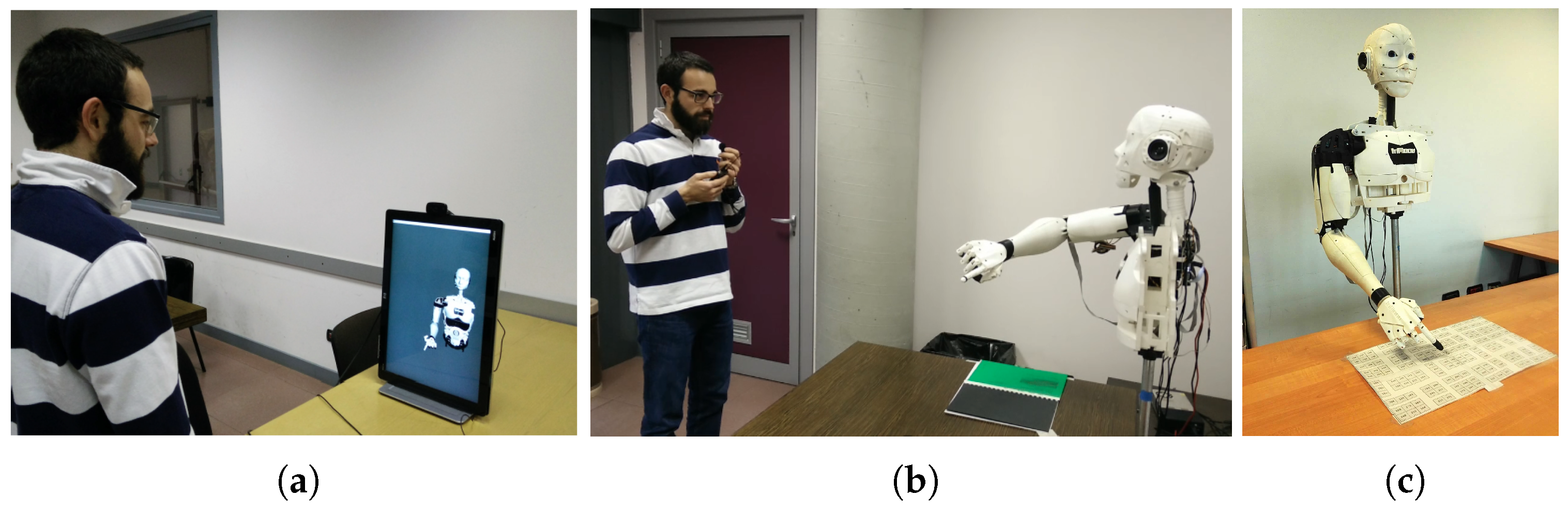

Thus, by moving from the above considerations, the aims of this paper are threefold. Firstly, it attempts to compare, through a user study, the usability and performance of receptionist systems using the most promising paradigms found in the literature for direction-giving applications. To this aim, a socially interactive physical humanoid robot capable of uttering directions and showing them on a map is compared with a robot featuring the same embodiment and social behaviors but leveraging gestures (precisely, arm pointing) for giving directions. For the sake of completeness, the virtual version of the latter configuration was also considered. Selected systems, which will be later referred to as PRM (Physical Robot with Map), PRG (Physical Robot with Gestures), and VRG (Virtual Robot with Gestures) are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Configurations considered in the first user study to evaluate the suitability and effectiveness of direction-giving systems developed so far: PRM (Physical Robot with Map), PRG (Physical Robot with Gestures), and—for the sake of completeness—VRG (Virtual Robot with Gestures).

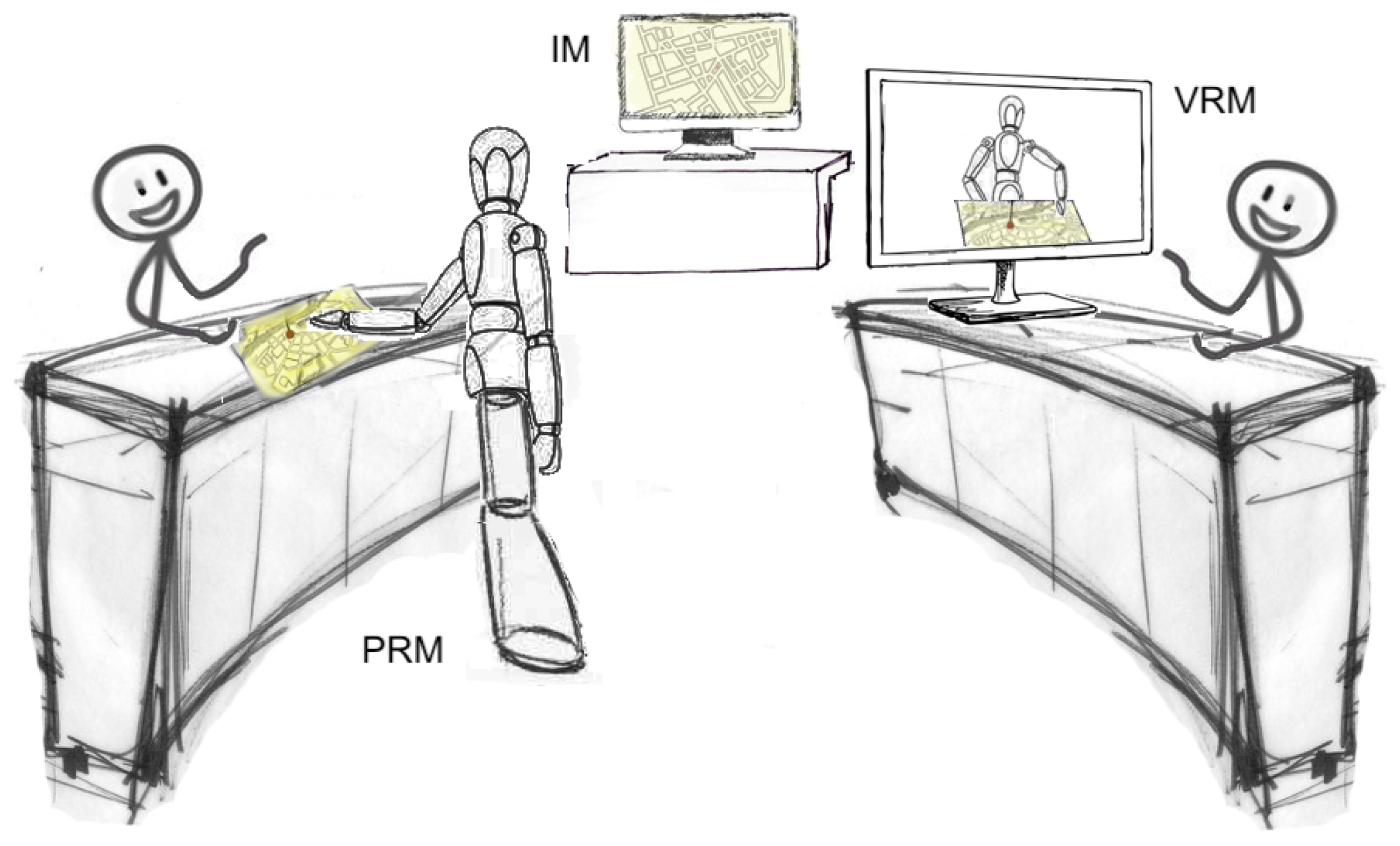

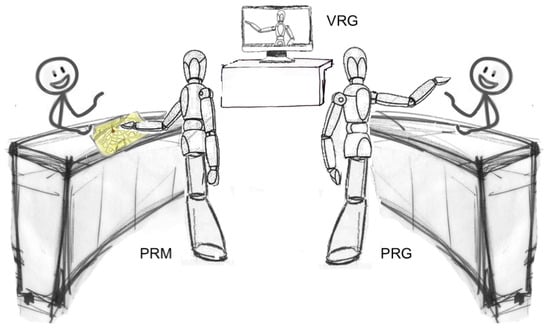

Secondly, starting from findings obtained from the above analysis regarding direction-giving interfaces, the focus is shifted onto evaluating how embodiment (either used, or not, and its type, i.e., physical or virtual) and social interaction aspects may influence the execution of wayfinding tasks. To this purpose, another user study is designed to compare the map-enabled, physically embodied robot of the first study with a virtual version of it (both endowed with social interaction behaviors), as well as with one of the most common approaches used today as a direction-giving system, i.e., an interactive audio-map (an unembodied system without social behaviors). Configurations considered in the study, illustrated in Figure 2, include again the PRM system and two other systems which will be later referred to as VRM (Virtual Robot with Map) and IM (Interactive Map).

Figure 2.

Map-based configurations considered in the second user study to assess the role of embodiment and social interaction behaviors in direction-giving systems: PRM, VRM (Virtual Robot with Map), and IM (Interactive-audio Map).

Thirdly, since differences between physical and virtual robotic receptionists in the previous analysis could be expected, in the second user study the roles of physical and virtual presence are also investigated.

Results of the first study indicated that the integration of a map in a physical, robot-based receptionist system can be beneficial in terms of user satisfaction, usability, and aesthetics. Moreover, experiments encompassing a virtual wayfinding task showed that completion rate and speed in reaching the intended destination are higher if directions are traced on a map rather than shown using in-the-air arm pointing gestures. Results of the second study suggested that embodiment and social behaviors have a positive effect on the above parameters, as well as in user ratings on usability and other aspects of the interaction. Experiments also showed that the physical version generally outperforms its virtual counterpart.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, relevant works in the field of reception, direction-giving, and wayfinding applications are reviewed. In Section 3, the motivations and the research goal, as well as the hypotheses formulated in this work, are introduced. Section 4 describes the receptionist systems considered in the study. Section 5 introduces the methodology adopted to perform the experimental tests and discusses results obtained. Lastly, Section 6 concludes the paper by providing possible directions for future research activities in this field.

2. Related Work

In this section, key research activities pertaining functionalities and embodiments of reception, direction-giving, and wayfinding solutions are reviewed.

2.1. Maps

Maps represent the most familiar navigation means used today for wayfinding tasks. In fact, the type of information, as well as its meaning, represent easily interpretable concepts for most people [15]. This is due to the fact that maps generally adopt conventions when used for navigation. An important aspect is the orientation used. The most common orientation is referred to as “forward-up” or “track-up”: The upper part of the map is aligned with the forward direction of movement [16]. Another important element pertains the way one localizes himself or herself on the map. In [17], Levin introduced the “You Are Here” (YAH) maps, where a symbol identifies the user’s location in relation to the surrounding environment.

Various methods have been experimented both by the industry and academics to enable the navigation of an environment through map-based direction-giving systems. For instance, in [18], a paper map (showing the user’s initial position and the destination of interest) was compared with a digital GPS-based map (showing the user’s current location, dynamically updated while he or she moves in space, and a static route to the destination) in wayfinding tasks. Direct experience was also added to the comparison; in this case, knowledge of the environment was obtained by physically walking in it. Authors’ goal was to examine how users acquire spatial navigation information. Results showed no difference between paper map and direct experience except for speed: Users with direct experience were faster than users with the map. Users with the GPS-based map traveled more slowly and made more direction errors than the other two user groups because of a lack of information about the surrounding environment. In fact, although the GPS-based system allowed users to follow the route on the screen by simply observing their current location on it, the small size of the map did not allow them to see the entire route. In the paper map, the starting point and the destination were shown together and a larger portion of the environment was actually displayed; however, performance was negatively influenced by the need for users to align their travel direction with the orientation of the map. Another study investigated the effectiveness of navigation aids provided through route maps (including inter-turn mileages, landmarks, etc.), voice directions, or both [19]. Authors found that auditory directional signals perform better than route maps both in terms of time needed to reach the destination and direction errors. This result shows that, even though voice directions require the precise knowledge of the users’ current location to be effective, the modality through which spatial information is acquired influences users’ performance. A similar and more recent study is reported in [20], where several methods for presenting route instructions ranging from spoken/written directions to 2D/3D map visualizations are compared. The 2D map was the solution preferred by the participants, both because it is the navigation means they were more familiar with, but also because they perceived to be able to locate and reach the target destination faster than with the other methods. These findings emphasize some drawbacks of the considered solutions. Specifically, voice and text instructions need accurate positional information to work and lack contextual information, but do not require users’ visual attention. 3D maps provide information about the surrounding environment, but have significant requirements from the technological point of view. Two-dimensional maps compensate possibly missing positional information and incorporate contextual information by demanding fewer resources. Another interesting study is reported in [21]: Here, a paper map was compared with a digital map. Results showed beneficial effects for both the proposed solutions, since they satisfy different needs. Precisely, paper maps provide the user with a better overview (and therefore a better understanding) of the surrounding environment thanks to their size and presentation perspective. Digital maps allow the user to interact with, to zoom and to query the map, as well as to see his or her current location on it. In [22], the attention was focused on the presentation of spatial information. In their work, authors compared two graphics representations: A real aerial photo and an abstract, generalized map. Results showed that users performed better with the generalized map: Users reported that the real map’s features were too cluttered and not easily discriminable compared to the minimalist map. In [23], Fewings claimed that whether static, interactive 2D or 3D, maps for indoor environments should always consider factors like user’s position visualization, size, color, lettering, and landmarks, etc. in order to maximize understandability.

In parallel to the above studies, other works focused on free-standing units endowed with interactive displays commonly found in public areas. These systems, generally referred to as “kiosks”, are meant to provide users with intuitive information about the current location and routes to reach a given destination. For instance, in [24], a kiosk system named Touch ‘n’ Speak was developed to provide users with information about restaurants in a specified area drawn on a touch-screen map. Voice commands could be issued together with touch inputs to specify filters, e.g., on food type or price. Even though this solution uses multimodal inputs, the speech recognition technique does not accept arbitrary inputs since it relies on a small vocabulary. In [25], the authors introduced Calisto, a system allowing users to plug in their smartphones to a touch-screen kiosk and to drag & drop interesting contents on their devices. Users could interact with the system both through touch and speech commands. In [26], a multimodal kiosk called MUSE and designed for shopping malls was introduced. Users could ask for shop locations via the touch menu or by connecting their mobile devices to the kiosk through a QR code displayed on the screen. The menu allowed users to search for shops’ information through a list (showing shops’ names in alphabetical order or grouped by category), whereas the mobile device could be used as a voice or a text interface. Directions were displayed on an animated map. In [27], a 3D touch-screen kiosk called i-Showcase was used in a shopping mall for allowing users to find the correct route to follow from their current location to the intended shop. Users could ask for shop locations via a category menu, a search bar, or a shortcut menu. A usability study was performed to compare the effectiveness of the above options. Results showed a high success rate in completing the task especially for those who were familiar with the kiosk experience. Users judged the kiosk as satisfactory, easy to use, and helpful for finding the right path to follow. Three-dimensional features were not considered as particularly helpful. In [28], a touch-screen kiosk was employed in a hospital for helping both patients and staff to find a particular location. The interface allowed users to look for the route to follow via a set of icons (representing places) grouped according to spatial criteria. After the selection of the intended destination, an animated path was displayed on a 2D map, accompanied by photographs, text, and (optionally) spoken directions. Experiments showed that the majority of users reached their destination without further assistance, with a high appreciation for the audio feedback.

Works considered in the above review have been selected as representative examples of the developments made by the academics. From a commercial perspective, it can be observed that map-based systems designed for wayfinding tasks often rely on a simplified version of architectural blueprints [29]. Some examples are Google Maps [30], HERE WeGo [31], Mapwize [32], and Cartogram [33]. Similarly, commercial wayfinding kiosks are often equipped with touch-screen displays exhibiting a YAH interactive map and animated paths drawn on it. Users can consult the map, e.g., by searching for places listed alphabetically, possibly grouped by category [34,35].

By taking into account advantages and drawbacks of the above solutions, the map-based receptionist system considered in this paper features a 2D digital YAH map like in [20,21]; as done in [19,28], the “forward-up” orientation and a voice output-based direction-giving system are used to support the users in acquiring spatial information. Rather than relying on a real picture of the place of interest, the devised map-based system uses a simplified, generalized visualization of the environment like in [22,30,31,32,33]. It also allows users to search for places by consulting a list in alphabetical order [26,34,35] and shows the entire [18] animated path on the map, like in [28,34,35].

2.2. Virtual Receptionist

The possibility to use virtual agents for providing assistance to human users has been extensively studied over the years. Historically, two main features were found to play a key role in their design: The adoption of natural user interfaces in the human-agent interaction (encompassing speech- and gesture-based communications, facial expressions, gaze tracking, etc.) and the choice to endow the agents with an embodiment [36,37]. Agents exhibiting these characteristics are generally referred to as Embodied Conversational Agents (ECAs) [38].

Many studies about ECAs investigated the use of these agents in reception and direction-giving applications. For instance, in [39], a virtual guide displayed on a screen is employed in a theater to help visitors in wayfinding tasks. When the user asks for the location of a given seat or place, the virtual guide provides him or her with indications on how to reach it by resorting to speech and in-the-air arm pointing gestures. A very minimalistic 2D map is displayed on the screen beside (to the right of) the virtual agent to show an animated path towards the destination. The main drawback of this solution is represented by the different reference systems adopted by the robot to point the way with arm gestures and by the map to show the path. In fact, arm gestures are performed in the agent’s (speaker’s) perspective, i.e., they are mirrored w.r.t. the map’s (listener’s) perspective, and this fact disoriented the users.

A similar configuration is reported in [40,41,42], where a kiosk featuring a conversational virtual robot named MACK (later evolved into NUMACK [43]) is used for providing route indications to human users. The agent is displayed on a screen. A small paper map is positioned on a table in front of it in order to create a “bridge” between the real and virtual worlds. MACK can assist the users in wayfinding tasks by leveraging three different interaction modalities: (1) Voice; (2) arm/hand gestures with head movements and eye gaze; and (3) an LCD projector that highlights a region of the map by allowing the agent to refer to it. Users can interact with the agent through a pen on the map or using voice. According to the authors, the system succeeded in engaging and entertaining users, but the kiosk setup made it difficult for users to understand when to look at the map and when to look at the agent. Specifically, authors reported that when users looked at the map, they did not pay attention to the agent’s gestures, and vice-versa. Investigating how users are involved by ECA’s gestures, the attention they devote to the map, and their preference or performance with the various configurations was deemed by the authors as an interesting evolution of the work done.

Another research direction focused on the social aspects of the interaction and on the level of engagement between a human user and a virtual receptionist. For instance, in [44], the authors presented Marve, a virtual receptionist able to recognize the users of a computer laboratory through face recognition, and to greet them with voice. Even though the agent was not able to give directions, it could understand humans’ speech, talk about weather or movies, tell jokes, or deliver messages. Experimental results showed that Marve was perceived as a true social being. The main limitation was the level of expertise required to interact with it. In fact, most of the users were computer scientists working in the laboratory, with the exception of the building guardian. The guardian interacted with Marve more often than any other user and, interestingly, his judgment on the level of engagement with the agent was higher than that of technical users. Authors concluded that different types of users might interact with and judge virtual agents’ social features in a diverse way.

By building on the above analysis, it was decided to incorporate in the virtual receptionist implementation considered in this paper the interaction modalities and social behaviors that are most commonly used in the reviewed works, i.e., head/gaze movement like in [41,42,43], face tracking like in [44], as well as speech and arm pointing gestures like in [39,40,41,42,43]. More precisely, as it will be shown in the next sections, user’s perspective gestures were used in order to align the virtual receptionist’s viewpoint with the user’s viewpoint, as learned from limitations reported in [39].

Considering the integration of a map into an embodied virtual receptionist system, it can be observed that two different approaches were used so far, based either on a virtual map or a physical map [39,40]. However, benefits possibly deriving from the use of a map on which an embodied receptionist can show the route, as well as the effectiveness, of such a direction-giving method compared to arm gestures are still open research questions. In this paper, route tracing on a virtual map is considered as a further interaction modality of the above receptionist system. To this aim, a map is placed on a virtual table in front of the robot at a distance that allows it to trace the route using its finger.

2.3. Robotic Receptionist

The receptionist role has been extensively studied also in the field of service robotics. By focusing on static, humanoid robot receptionist systems, a number of implementations have been developed, which can be classified in two main categories according to the level of embodiment: Robots with a physical body and a virtual face displayed on a screen, and fully physical robots. Examples of the former category were given in [45,46,47], where a robotic receptionist named Valerie was employed in a university to investigate robot’s social attraction and visitors’ engagement when interacting with the robot. Valerie is able to give directions using the voice, and exhibits its personality through a number of pre-defined facial expressions. Users can interact with the robot using voice commands or by typing text on a keyboard. Experimental results showed that even though users were attracted by and engaged with the robot, interaction methods had to be improved since in some circumstances they were restricted to using keyboard inputs. In [48], another robotic receptionist system named AVARI was introduced. The robot was employed in a university scenario, and was equipped with a knowledge repository which allowed it to answer questions about professors’ office location and email address through voice interactions. The limitation of this solution was the timing of the interaction, since robot’s answers were not synchronized with users’ questions. As studied in [49], the timing of interactions may influence social strategies and task performance, as well as turn taking and engagement. Other works focused on cross-cultural phenomena, by investigating how robot’s politeness, gender, and language could improve users’ acceptance and level of attention [50,51]. Results of experimental observations showed that design choices should be culture-aware: For instance, in the scenarios considered in [50,51], it was demonstrated that the use of local language, of a robot equipped with a female aspect and voice, as well as of a polite behavior could enhance the robotic receptionists’ social presence and acceptance.

Similar studies have been conducted also for fully physical robots. A number of works investigated the role of robotic receptionists by focusing on different factors ranging from more technical features to social interaction. For instance, in [52], a speech-oriented humanoid robot named ASKA was employed as a receptionist in a university. The robot is able to understand users’ questions concerning the route to a given location and provide directions through arm pointing gestures and voice. It is worth observing that, since the main goal of that work was to develop a robust dialog system in order to allow humans and robots to interact in a real-world scenario, no consideration was made concerning ASKA’s effectiveness as a direction-giving system. Similarly, in [53] authors focused on the dialog structure in the communication between robotic receptionists and human users in an office scenario, with the aim to create a system able to identify people and learn their names. The robot used voice to provide information about the office where an employee could be found, and was optionally able to give indications about office’s location. Again, no evaluation was performed on the effectiveness of the guidance provided. In [54,55], the attention was focused on the effectiveness of arm pointing gestures for referring to a given target. Specifically, in [54] the authors presented a robot equipped with a statistical model for estimating ambiguity in arm pointing gestures made by humans when used to refer to objects/places. They demonstrated that the distance between the human user and the indicated target, as well as the mutual distance between different targets, may introduce uncertainty in the detection phase. In [55], the authors investigated the use of arm pointing gestures in deictic interactions referring to a region in space, and identified the approach that is more effective for performing the considered task.

As mentioned, alternative approaches focused on social phenomena rather than on technical aspects. For instance, in [56], a Wizard-of-Oz receptionist robot providing voice directions is used to explore human-robot interaction and identify possible behavioral patterns. In [57], the authors showed that equipping a receptionist robot named SAYA with the ability to nod the head (robot’s body cannot move) could improve human-robot interaction in terms of human-likeness, understanding, and familiarity.

Other works specifically studied direction-giving tasks. For instance, in [58], the Robovie robot was employed to provide directions by integrating utterances and gestures; pauses were introduced in the dialog, timed on how humans speak and listen. Experimental results showed that, although voice was sufficient to let users understand the route, deictic gestures pleasantly enriched the utterances. Moreover, the listener’s pause-based interaction model was preferred to the speaker’s pause-based one. In [59], the NAO robot was used to track office workers through face detection and to provide them with directions by using voice and gestures. Experiments showed that the adopted approach was not effective for long paths, for which directions could be complicated and hard to remember. Similarly, in [60] an iCub robot placed at a reception desk was used to deliver route information by using voice, deictic gestures, or pointing the destination on a physical map. Like in other works, no qualitative or quantitative assessment of the considered direction-giving approaches was conducted.

By taking into account pros and cons of the above solutions, the robotic receptionist implementation considered in this work is a fully physical robot (from the torso up the head). The robot is endowed with (social) interaction capabilities that allow it to detect [59] and greet users by speaking the local language [50,51], and to provide them with route information using arm pointing gestures and utterances (with a female voice) [58,59,60]. Like in most of the works considered, users can receive spoken directions, while the robot’s head/gaze moves to track their face [57]. Considerations made in the previous section concerning the integration of a map into an embodied virtual receptionist system also hold for physical embodiments [60]. Hence, as said, one of the objectives of the present study will be to investigate whether the integration of a map in a physically embodied receptionist system and the possibility for the receptionist to trace the route on it can actually influence the users’ understanding of the directions given, and their ability to reach the place of interest in a different way than arm pointing gestures.

3. Research Goal

Since the panorama of receptionist systems is quite heterogeneous, information about the suitability and performance of a particular implementation compared to other solutions is needed.

Although most of the works considered in the above review did not focus on evaluation, some activities in this direction have been carried out already. For instance, in [61,62], authors compared two receptionist systems with different embodiments, i.e., an on-screen virtual ECA named Ana and a humanoid robot with a mechanical look named KOBIANA, both able to provide guidance to users about the position of two different rooms (red and blue) through the use of voice. Authors’ goal was to investigate how different visual appearances and voices (human-like vs. robotic), as well as different embodiments (physical vs. virtual), could influence humans’ judgment of the considered receptionists as social partners. Subjective observations showed that Ana was preferred to KOBIANA due to human-like aspect and voice. However, objective observations indicated that the number of participants who got lost with KOBIANA’s directions was much lower compared to those who received directions from Ana. Unfortunately, according to the authors, results were biased by the fixed order adopted by the users to test the two systems: Thus, no definitive conclusion on the impact of receptionists’ aspect could actually be drawn.

The authors of [63] performed a similar comparison on the effectiveness of two different embodiments for a receptionist system. However, they also compared the above solutions with a more conventional (unembodied) wayfinding means, i.e., a map. Precisely, they considered a virtual ECA (named NUMPACK), a humanoid robot (named KHR2-HV) and a GPS-based map. The two embodied receptionist systems (with different sizes) were capable to provide indications in three different ways: Voice only, voice and arm pointing gestures with listener’s perspective, and voice and arm pointing gestures with speaker’s perspective. The GPS-based system was configured to either show the map and provide voice guidance, or to just play back the audio directions without showing any map. The ultimate goal was to perform a study on what the authors called the “agent factor” (robot vs. ECA vs. map) and the “gesture factor” (no gesture/no map vs. speaker’s perspective/map vs. listener’s perspective/map) in wayfinding tasks. During the experiments, subjective and objective observations were collected in order to judge the effect of the embodiments and their social perception, as well as the effectiveness of navigation aids and their impact on users’ performance. Performance measures were based on a retelling task (in which users were asked to mention the indications received from the system) and a map task (in which users had to draw on the map the route they heard/saw). Objective results showed no difference in users’ performance based on the type of embodiment. However, a strong impact on both performance and perception was introduced by listener’s perspective gestures compared to speaker’s perspective and no gestures. Subjective results showed that the two embodied systems (ECA and robot) positively influenced users’ judgment in terms of social perception. Furthermore, the physical robot was preferred and judged as more understandable and co-present than the others solutions when listener’s perspective gestures were used. The virtual robot was judged as more familiar and enjoyable than both the physical robot and the map when the no gesture/no map configurations were experimented, confirming findings obtained in [61,62].

By summarizing results from the above studies, it can be observed that virtual embodied receptionist systems are preferred when used to give voice directions, whereas physical humanoid robots are perceived as better receptionists when gestures are employed. In particular, it can be noticed that listener’s perspective gestures lead to better performance compared to speaker’s perspective gestures (and voice directions alone).

Despite the relevance of these empirical cues, a comprehensive exploration of the extended design space for receptionist systems has not been conducted yet. For instance, only a few works explored the benefits possibly ensured by the integration of a map, by studying the resulting configurations (physical or virtual embodiment, combination of map and voice, as well as arm pointing gestures, etc.).

Based on the above considerations, three hypotheses were identified for the current work. The first hypothesis derives from the assumption that adding a map on which a physically embodied receptionist can show the route while giving directions might improve users’ correct understanding of the indications received and their ability to reach the place of interest compared to the best approach proposed in the literature, i.e., physical humanoid robot equipped with (listener’s perspective) arm pointing gestures (Figure 1).

Hypothesis 1.

The integration of a map in a physically embodied receptionist system and the possibility for the receptionist to trace the route on it would be more effective in direction-giving tasks compared to the use of arm pointing gestures.

Assuming that having a receptionist system that shows the path to follow on a map can increase likeability and performance, this work also purports to investigate the role played both by different embodiments (physical, virtual, unembodied) and social behaviors (with and without) in the considered context. To this purpose, like in [63] two robotic receptionist systems (physical and virtual) were compared with a conventional wayfinding solution, i.e., a map (Figure 2). The second hypothesis reads as reported below.

Hypothesis 2.

Embodied receptionist systems (both virtual and physical) endowed with social behaviors (gaze, face tracking) would be evaluated in a better way and would lead to better performance in wayfinding tasks compared to a map-only (unembodied) solution without social behaviors.

Should the latter hypothesis be verified, one could expect to observe measurable differences in users’ evaluations between physical and virtual receptionist robots. Thus, the third hypothesis of the present work serves to dig into these possible differences, by exploring the role of physical presence (robot co-located with the user) compared to virtual presence (robot displayed on a screen). To this purpose, the two embodied receptionist systems considered in this work were designed to share the same (robotic) visual appearance, though in one case the robot was displayed on a screen (Figure 2). The third hypothesis is given below.

Hypothesis 3.

The physical presence through a co-located robot would have a higher measurable impact on participants’ performance, as well as on their perception of social interactions, in wayfinding tasks compared to a virtual robot displayed on a screen [64,65].

4. Receptionist Systems

In the following, the embodied and map-based (socially interactive) receptionist systems developed for this study will be introduced, by providing also some implementation details. The order of presentation will follow the order in which the systems are introduced in the hypotheses discussed in the previous section. Accordingly, the physical robot will be introduced first, followed by the virtual robot and, finally, by the interactive audio-map.

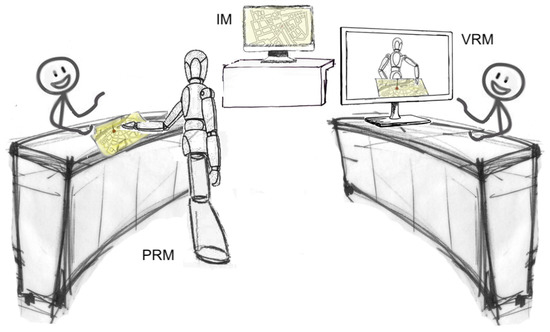

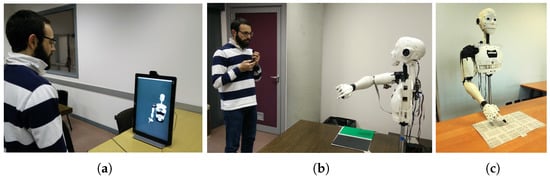

4.1. Physical Robot

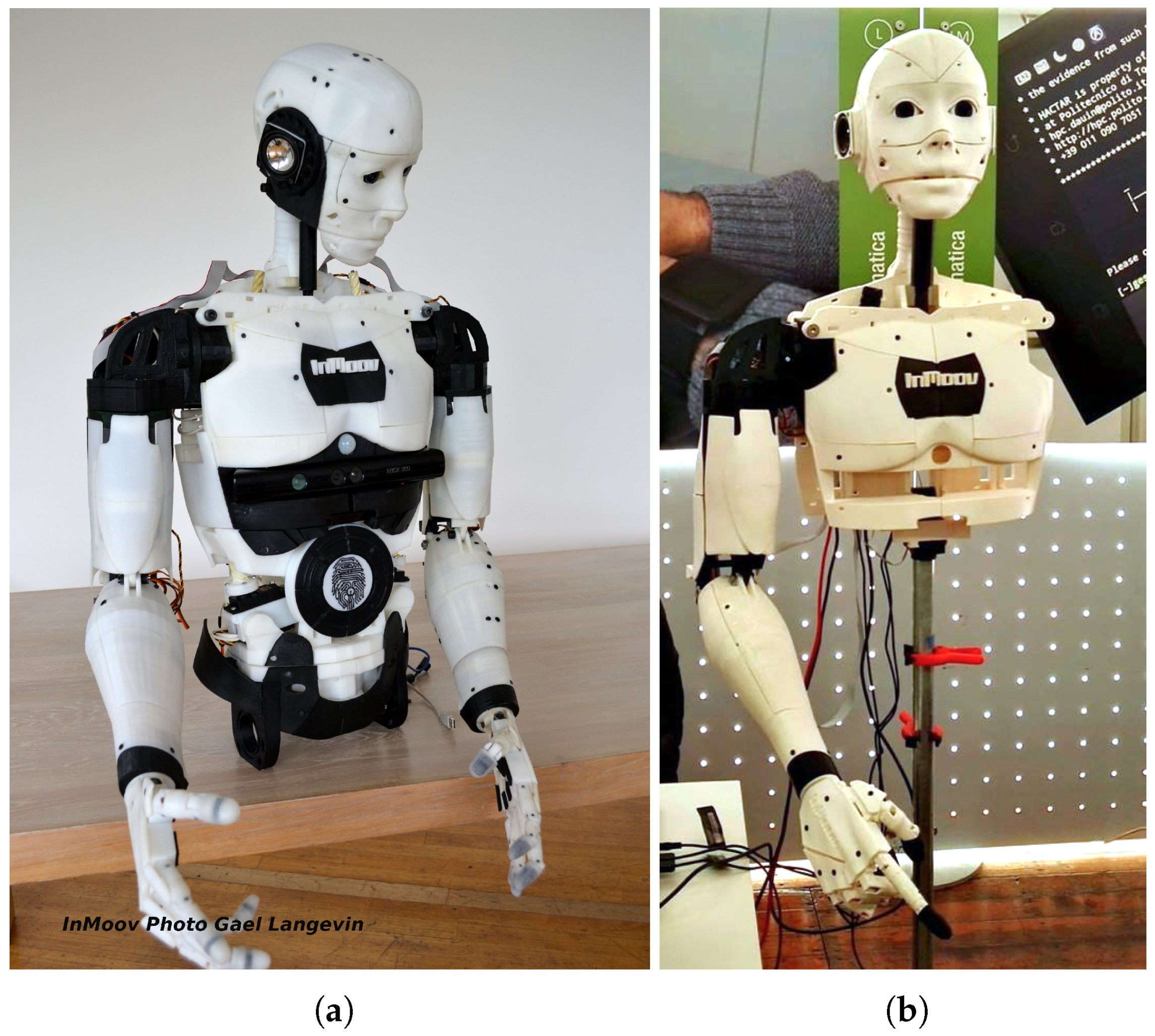

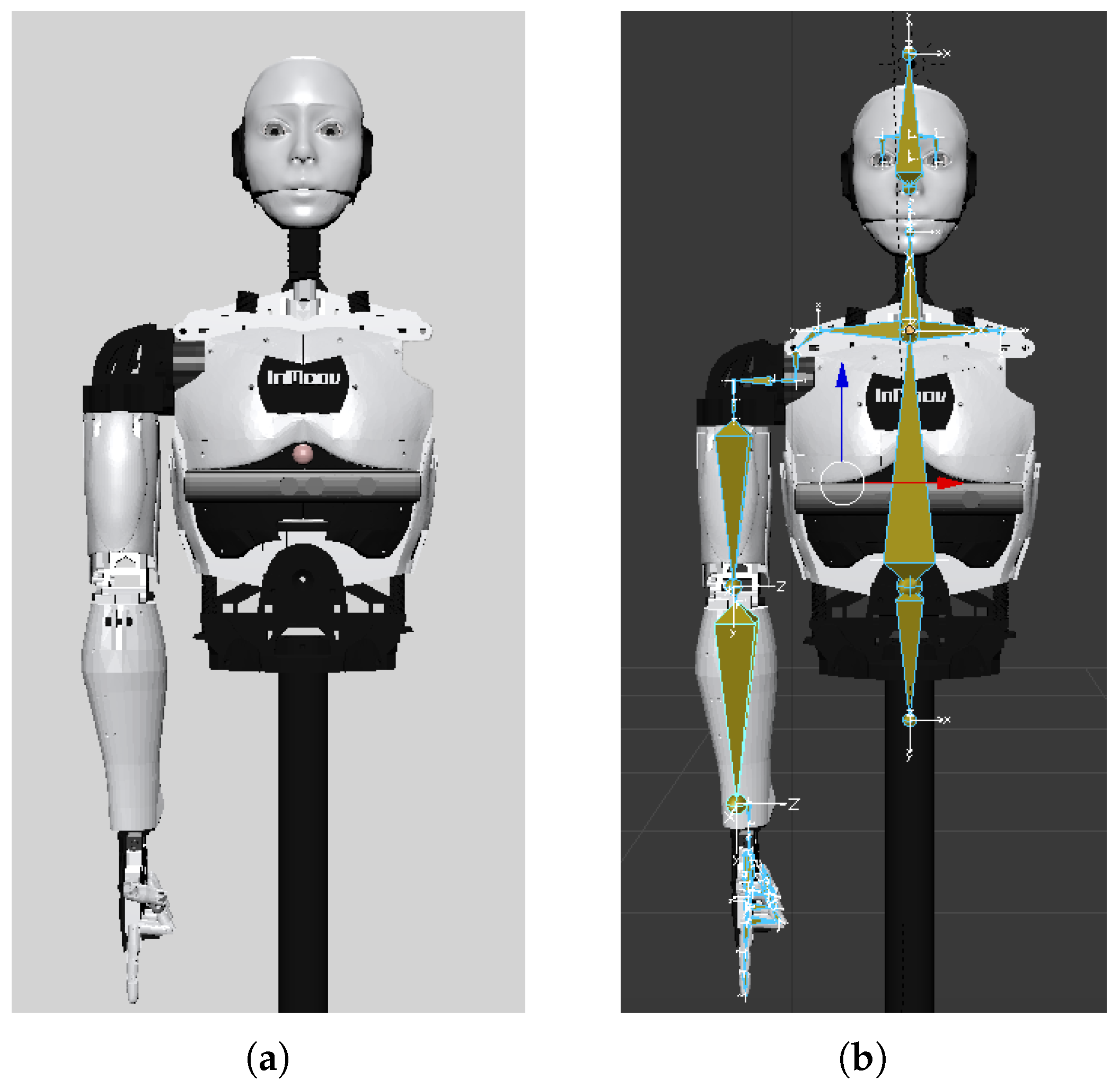

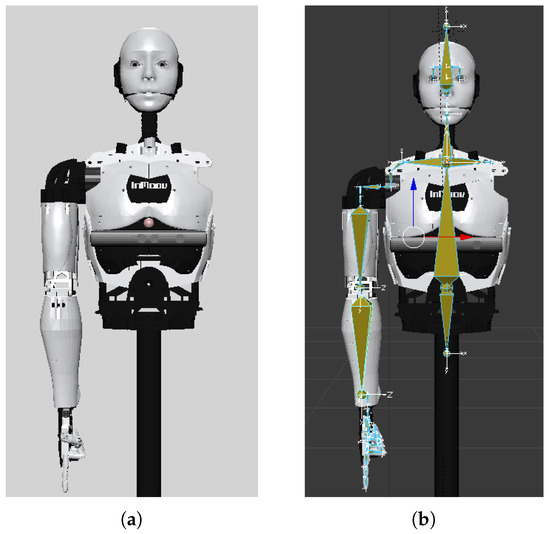

The robotic platform that was considered in this work to study the role of a physical receptionist is named InMoov [66]. InMoov is a humanoid robot designed by the French sculptor Gaël Langevin within an open source project initiated in 2012. It is entirely built out of 3D printing ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) filaments (Figure 3a). For the purpose of this research, only the upper torso, the head and the right arm (including the biceps, shoulder, and hand) were printed (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Robotic platform used in this study: (a) Original design of the InMoov robot, and (b) robotic receptionist implementation.

4.1.1. Hardware Components

The robot’s assembly includes 15 servomotors with different speeds and torques distributed on the body and providing a total of 16 degrees of freedom (DOFs): 5 DOFs for the head, 5 DOFs for the arm, 1 DOF for the wrist, and 5 DOFs for the fingers. All the arm servomotors were modified to allow the robot’s joints to perform unconstrained rotations not allowed in the original design. The arm chain (omoplate, shoulder, bicep, elbow, forearm, and wrist) consists of six revolute joints controlled using inverse kinematics (IK).

The central processing unit consists of an Arduino Mega ADK (https://store.arduino.cc/arduino-mega-adk-rev3) board. This micro-controller is responsible for collecting commands from various software modules running on a PC (discussed later) and transmitting them to the servomotors.

Two cameras were positioned in the robot’s eyes in order to reproduce the vision system. Concerning sound reproduction, two speakers were used; they were attached to an amplifier board and positioned in the robot’s ears. For the auditory system, an external microphone was used in order to limit the impact of noise produced by the servomotors on the perceived audio.

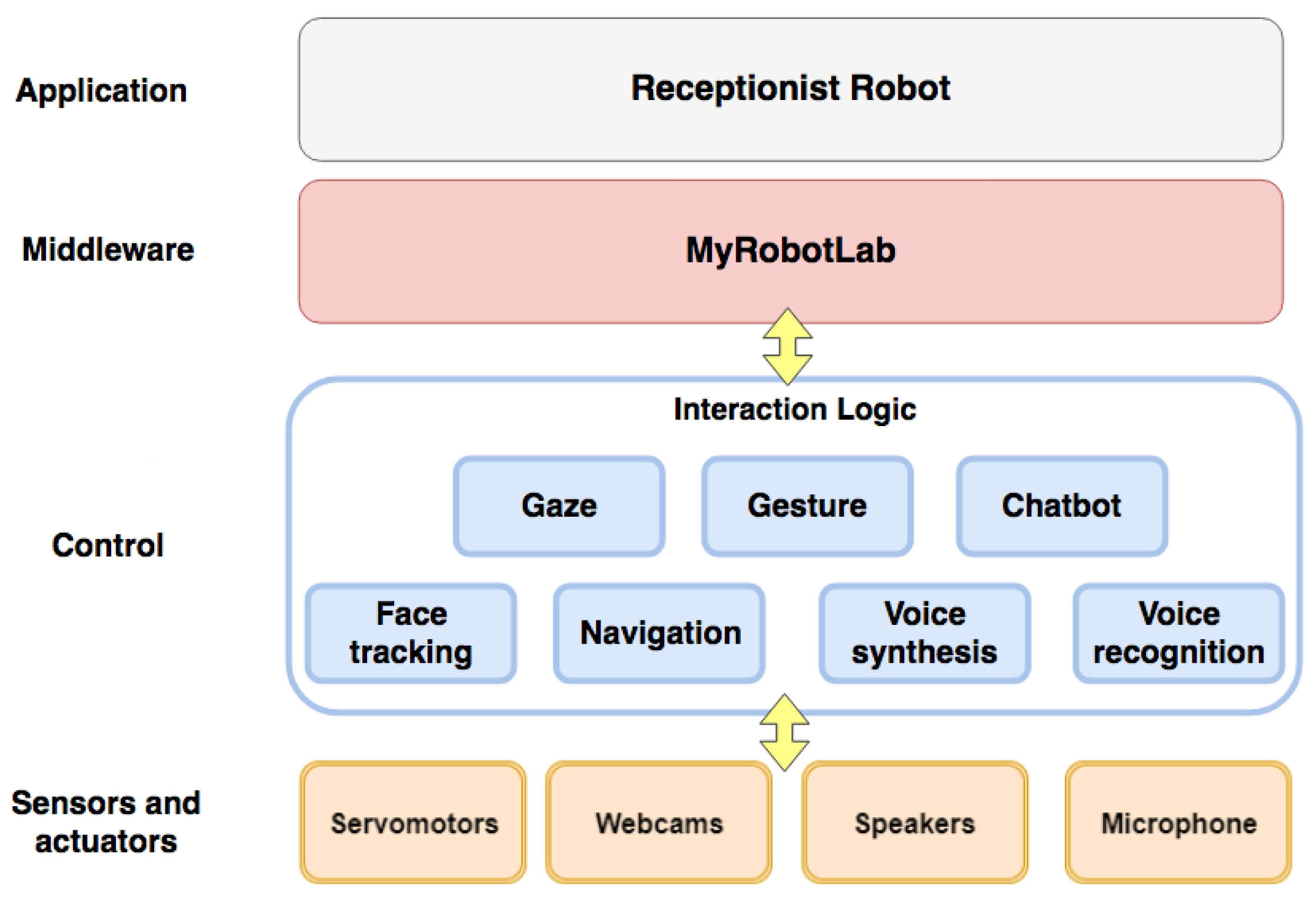

4.1.2. Software Components

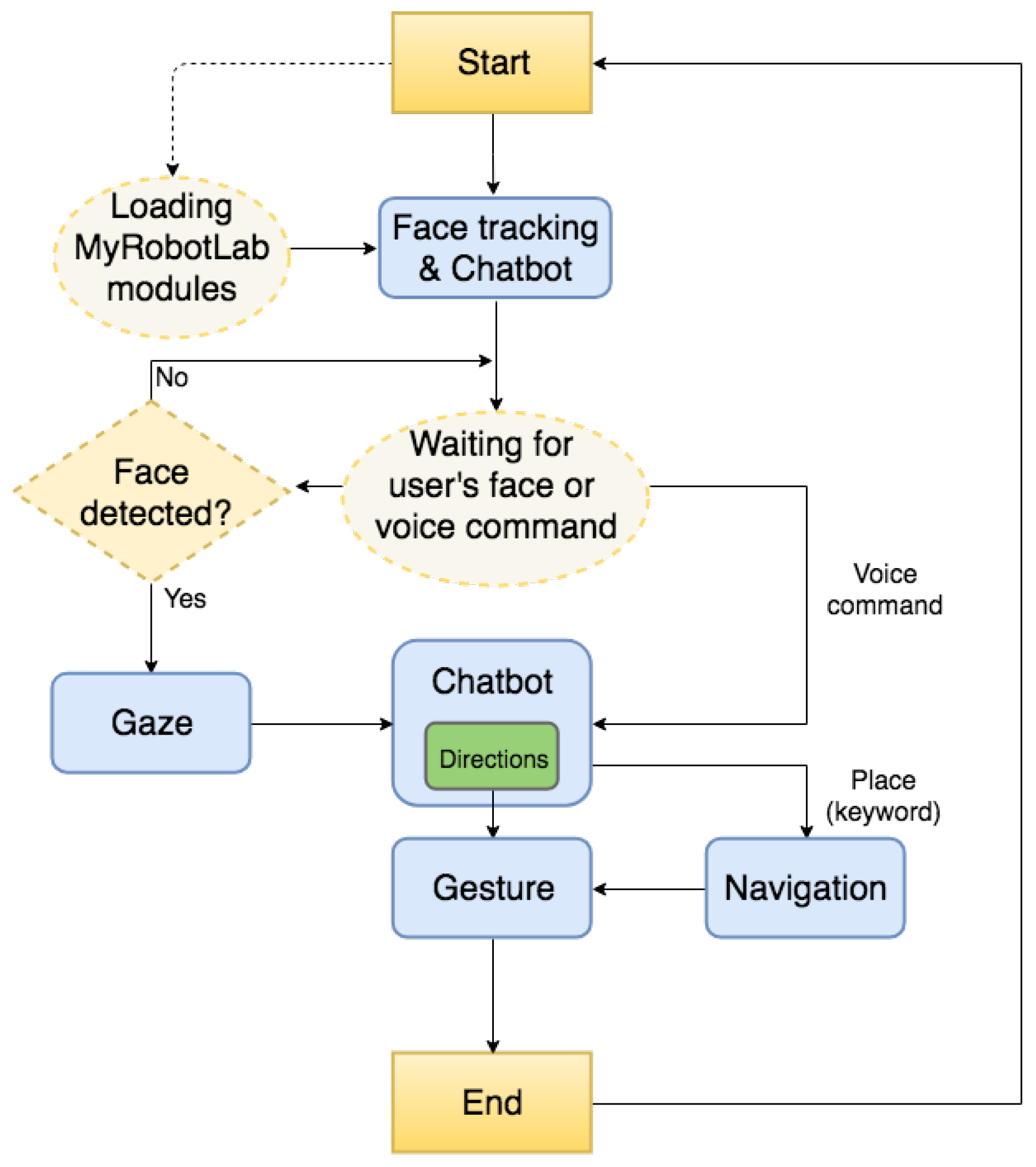

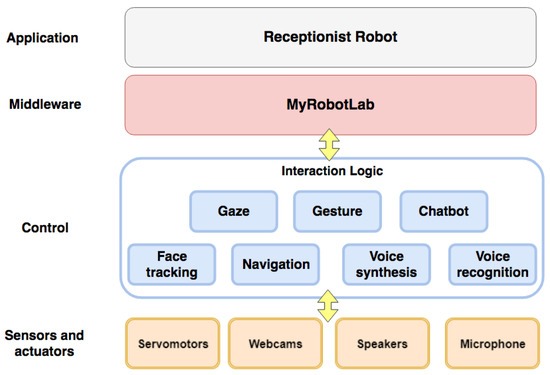

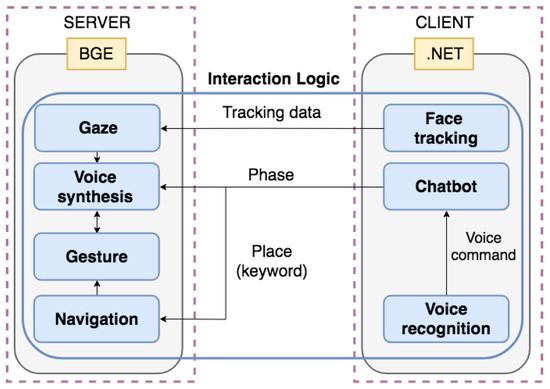

The logical components that were assembled and/or developed to implement the robotic receptionist system are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

High-level architecture of the robotic receptionist system.

In the devised architecture, which was inherited from the InMoov project, the lowest layer is represented by the physical robot’s sensors and actuators described in Section 4.1.1. The control layer consists of eight main modules, which are used to manage the robot’s direction-giving functionalities. Modules are described below.

- Face tracking: This module processes the video stream received from the cameras to detect the presence of human faces and their position in the robot’s field of view. It is based on MyRobotLab (http://www.myrobotlab.org) Tracking module, which can track human faces in real time through the OpenCV (https://opencv.org) library. When a face is tracked, the robot’s head is adjusted in order to keep the identified face in the center of its field of view. In a reception use case, in which the robot is expected to be placed in public and crowded areas, not all the detected people may want to start a conversation. Hence, in order to limit the number of unwanted activations, two events, i.e., foundFace and lostFace, were added to the original tracking module. The foundFace event is fired when a human face is detected in a given number of consecutive frames; similarly, the lostFace event is fired when no human face is detected in a pre-defined number of frames. Data produced by this module are sent the to Gaze module.

- Gaze: This module is responsible for managing robot’s head and eyes movements during the interaction with a human user. For instance, in the greetings and farewell phases, the robot’s gaze is oriented towards the user’s face. In the configuration studied in which the robot is giving directions by pointing destinations on a map, gaze is directed on the map.

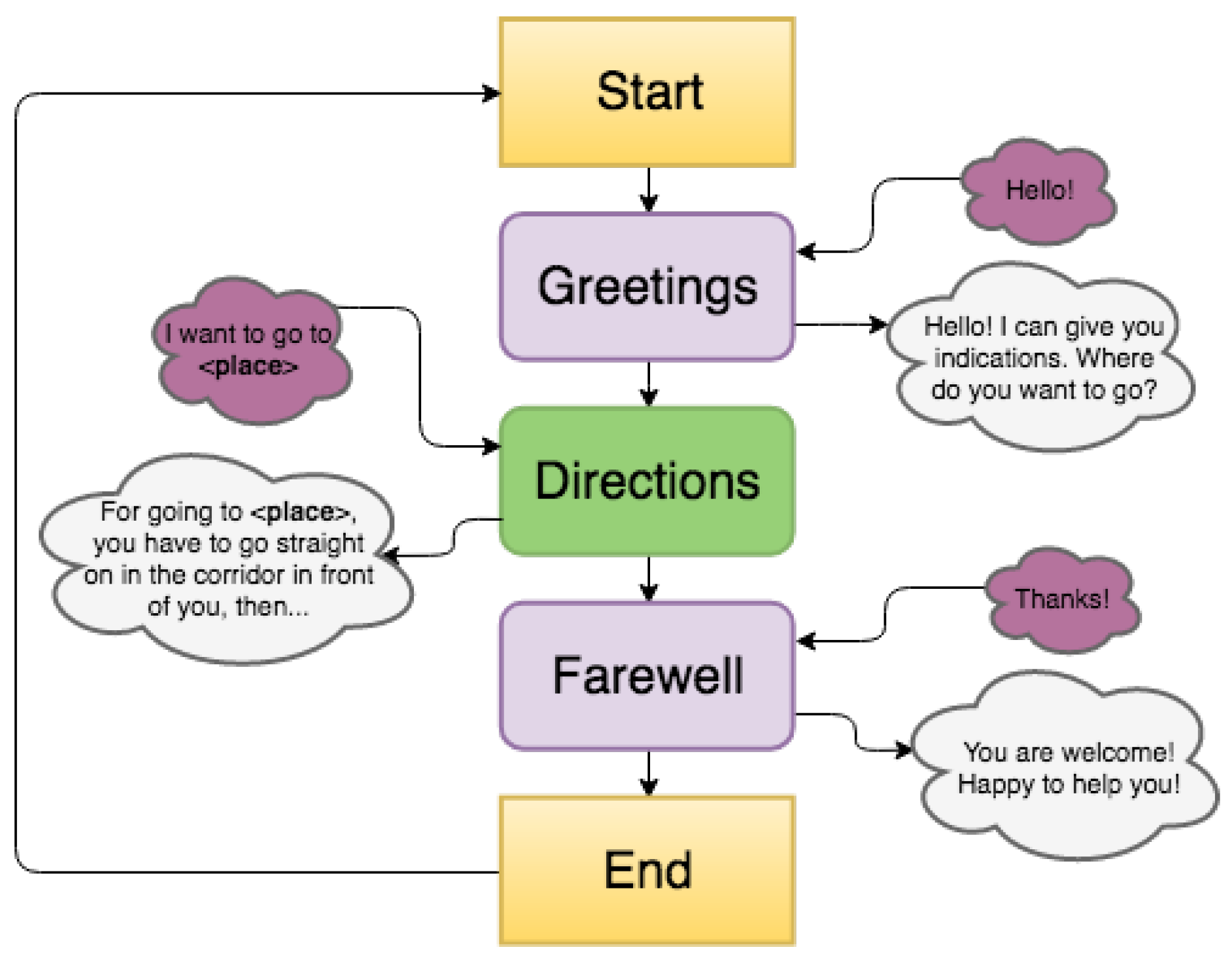

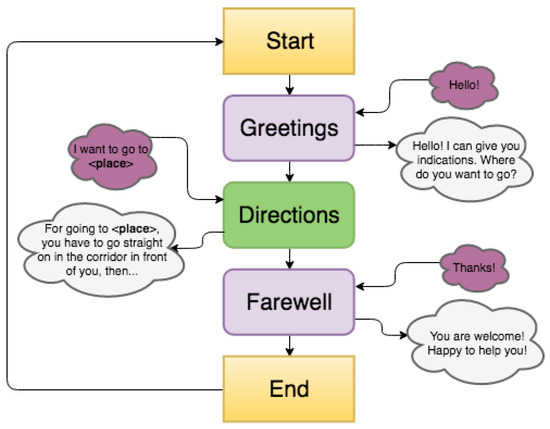

- Chatbot: This module represents the brain of the system, and generates text responses based on received text stimuli. It relies on the A.L.I.C.E. bot (http://www.alicebot.org), an open source natural language processing chatterbot that uses a XML schema called AIML (Artificial Intelligence Markup Language) to allow the customization of a conversation. With AIML it is possible to define the keywords/phrases that the robot should capture and understand (related to greeting/farewell phases, as well as to destinations) and the answers it should provide (greeting/farewell expressions and directions). In addition, when a keyword/phrase concerning a destination is spotted, the AIML language can be used to activate robot’s arm gestures for giving directions, by sending required information to the Navigation module. The conversation logic adopted by the robot is illustrated in Figure 5: purple clouds represent examples of possible user inputs, whereas grey clouds are examples of possible robot’s answers.

Figure 5. Robotic receptionist’s conversation logic.

Figure 5. Robotic receptionist’s conversation logic. - Voice recognition: This module receives voice commands from the microphone, converts them to text using the WebKit speech recognition APIs by Google, and sends the result to the Chatbot module.

- Voice synthesis: This module allows the robot to speak. It receives text messages from the Chatbot module, converts them into audio files through the MaryTTS (http://mary.dfki.de) speech synthesis engine, and sends them to the speakers. In addition, when a message is received, it triggers a moveMouth event, which makes the robot’s mouth move by synchronizing with words pronounced.

- Navigation: This is the main module that was developed in this work and integrated in MyRobotLab in order to provide users with directions for the requested destination. It is based on the IK module available in MyRobotLab, which was adapted to move the end-effector of robot’s arm and reproduce pointing gestures (in-the-air or on the map). The IK module does not guarantee that a runtime-computed solution always exhibits the same sequence of movements for the end-effector to reach the intended position. Moreover, should the solution fall in a kinematic singularity point, it would cause the robot’s arm to lose its ability to move, making it unusable. For these reasons, the module was modified to execute an IK pre-calculation phase, in which the end-effector is moved to the intended position by means of a controlled sequence of gestures made up of small displacements along the axes. When the desired position is reached, the gesture sequence is saved in the system and associated to the given destination. In order to make the robot move in a natural way, tracking data of a human arm executing the required gestures were recorded using a Microsoft Kinect depth camera and the OpenNI software (http://openni.ru/) and properly adapted to the considered scenario. When the destination is identified by the Chatbot module, the Navigation module loads the corresponding sequence and transmit gestures to the Gesture module, which actuates them.

- Gesture: This module was created within the present work. Its role is to make the robot execute the gesture sequence suitable for the particular direction-giving modality being considered (in-the-air or map pointing gestures) and the specific destination selected.

- Interaction logic: This module controls all the previous ones based on the flow of human-robot interaction and the direction-giving modality in use. As a matter of example, while the robot is speaking using the Voice synthesis module, the Voice recognition module needs to be stopped to avoid misbehavior.

The execution of the above modules is orchestrated by a middleware layer, which is represented by the MyRobotLab Java service and acts as an intermediary between the application layer and robot’s functionalities.

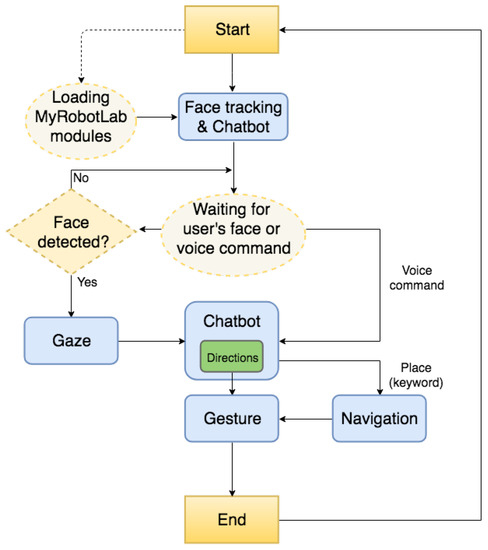

The stack is completed by the application layer, which actually implements the reception logic illustrated in Figure 6, thus making the robot interact with human users and give directions in a natural way.

Figure 6.

Robotic receptionist’s application logic.

When the system starts, it initializes the MyRobotLab modules and waits for external stimuli to initiate the interaction. Stimuli may be both a detected face or a voice command issued by the user. In the first case, the receptionist robot begins the interaction with the greetings phrase: “Hello! I can give you indications! Where do you want to go?”. Afterwards, the user can continue the interaction as shown in Figure 5. If no answer is detected, the robot returns in the waiting phase. In the second case, the user starts the interaction by greetings the robot or asking it about a given destination. Interaction continues as illustrated in Figure 5.

4.2. Virtual Robot

The robot’s virtual embodiment used in this work consists of an open source 3D model of the physical InMoov robot displayed on a 27-inch monitor with resolution.

The 3D model was chosen to exhibit the same appearance of the physical robot rather than that of a virtual human-like character because of Hypothesis 3 in Section 3. In fact, one of the goals of this work is to study whether a physically present, co-located receptionist system could influence users’ ability to find places of interest, as well as their sense of social presence compared to the same system displayed on a screen. The choice of a robotic aspect for both the physical and virtual robots can limit the presence of biases in the evaluation due to the receptionist’s appearance. Notwithstanding, it is worth saying that the use of a (2D) screen to display the 3D model could introduce differences in the way users perceive the virtual and the physical robots (e.g., in terms of size, tridimensionality, etc.). Hence, future work should be aimed to further dig into the above aspects.

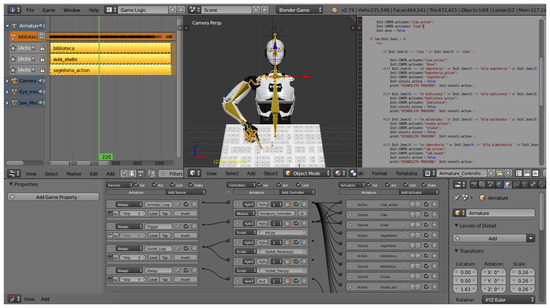

As illustrated in Figure 7a, the 3D model, later referred as VinMoov, includes the following parts: Head, upper torso, right arm (omoplate, shoulder, bicep, elbow, forearm, and wrist), and hand. Similarly to the physical robot where servomotors are used to control the movements of the various body parts, VinMoov is equipped with a virtual skeleton, or “rig”, made up of bones and joints which are articulated to make the 3D model assume intended poses (Figure 7b). All the DOFs in the physical robot were maintained.

Figure 7.

VinMoov: (a) aspect; and (b) rig used for controlling deformations (poses).

The workstation hosting VinMoov was equipped with a webcam positioned on top of the screen in order to replicate the vision system of the physical robot. Moreover, like in the physical robot, the auditory system was implemented by an external microphone, whereas two external speakers were placed on the sides of the screen for reproducing sound.

Like for the InMoov robot, MyRobotLab provides a so-called Virtual InMoov service to manage the operation of the virtual robot in two modalities: user and developer. The former allows users to work with the exact features available in InMoov, whether the latter allows them to develop or test new functionalities without the physical robot. However, without the physical robot, the timing of the virtual replica’s movements are not recreated in a proper way. This is due to the fact that, in the physical robot, the timing of movements is dictated by the real presence, type and physical features of the servomotors, which are only virtually recreated in the above service. Furthermore, although the user mode reached a stable version, the developer mode (the appropriate mode for the integration of the Navigation module developed in this work) is currently under development, and interfaces are changing rapidly.

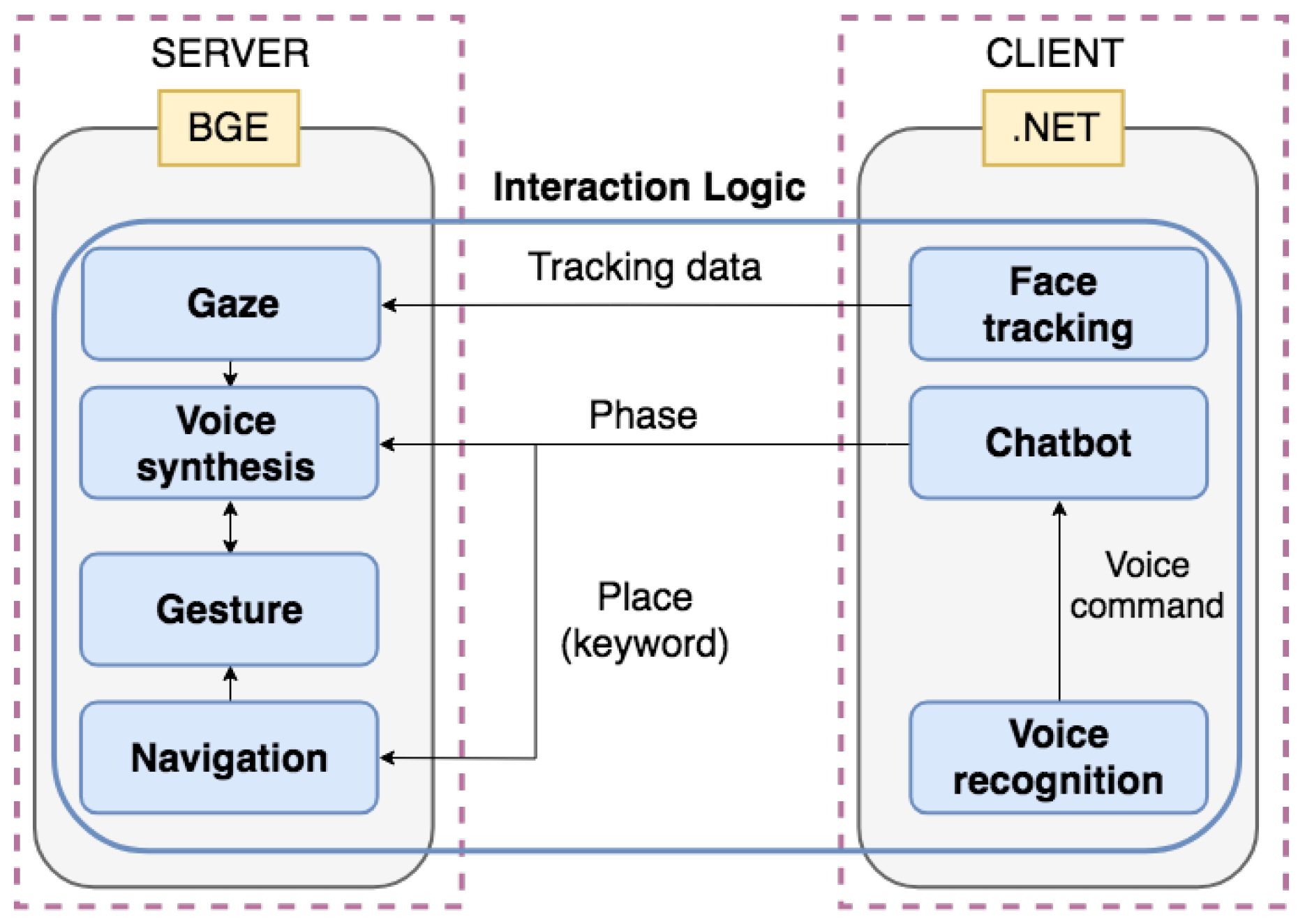

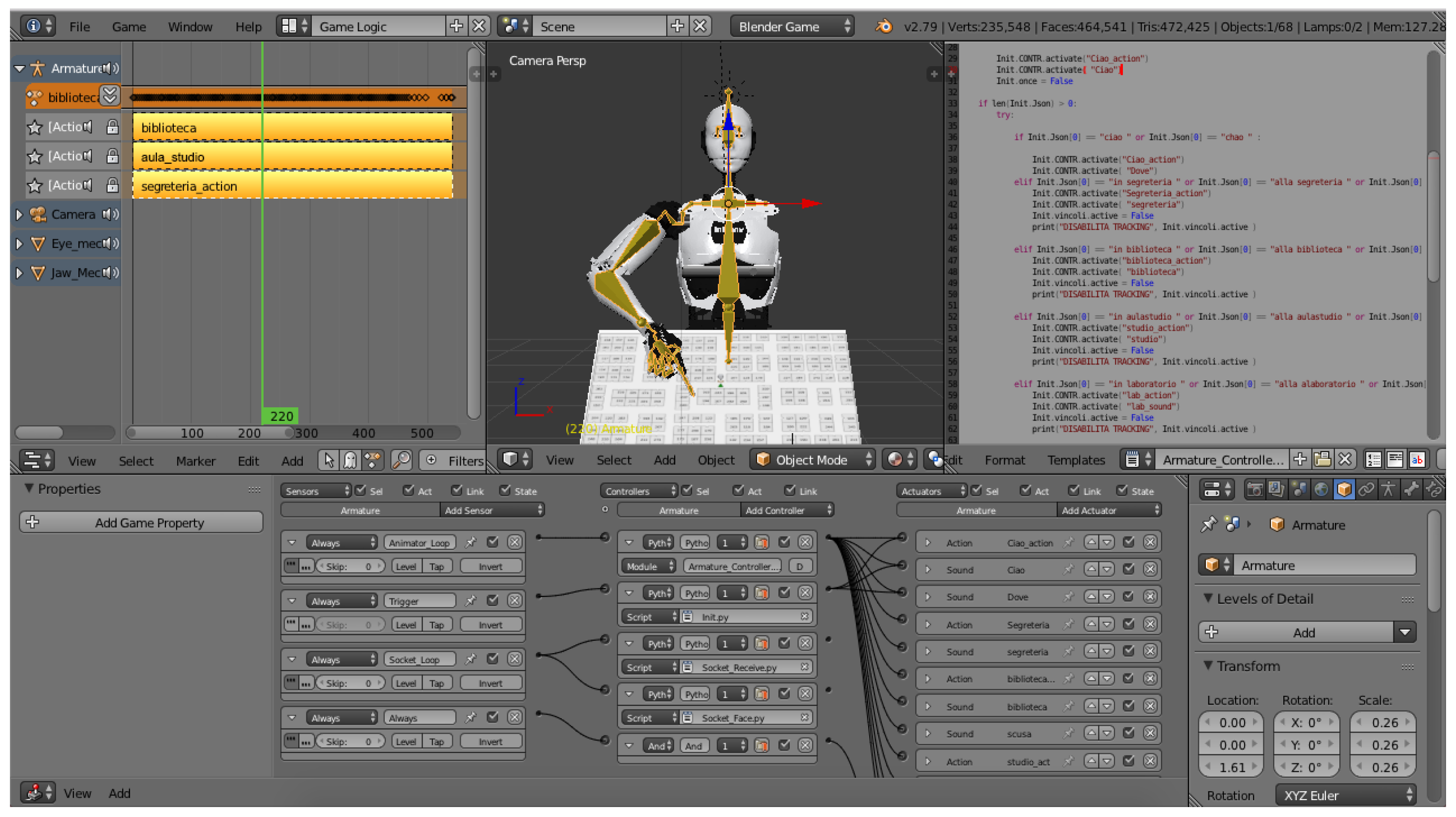

Thus, in this work, it was decided to discard the MyRobotLab for the virtual robot, and to develop a separate software for implementing the VinMoov-based reception service. Software architecture, developed according to the client-server paradigm, is depicted in Figure 8. The client side consists of a .NET application implementing the modules responsible for managing the interaction: Face tracking, Chatbot, and Voice recognition. The server side hosts the Blender Game Engine (https://www.blender.org) (BGE), which is responsible for handling the rendering of the 3D model and running the modules providing the interaction feedback: Gaze, Voice synthesis, Gesture, and Navigation.

Figure 8.

High-level architecture of the VinMoov receptionist system’s control logic.

The choice to implement the modules on the client or the server side was based on the availability of third-party libraries to ground developments onto.

Thus, the Face tracking module was implemented like in the physical robot, by using the OpenCV image processing library, applying the same filters, and handling the same events. Once the 2D position of the interacting user’s face in the robot’s field of view is determined, tracking data are sent to the Gaze module in order to allow the VinMoov’s head/eyes follow it. The Gaze module maps these data (two coordinates) on a 3D object placed in front of the virtual robot (third coordinate is fixed on the 3D world), which mimics the position of the face in the BGE reference system. A track-to constraint applied to the VinMoov’s head bone simulates the face tracking of the physical robot. The difference in the position of the camera(s) between the physical and the virtual robots did not affect the accuracy of the head’s movements.

Through the Chatbot module, it is possible to control (customize) the interaction by defining the inputs to be spotted, which are then sent to the Voice synthesis and Navigation modules like in the physical robot. The module was implemented through the Microsoft Grammar Builder service (http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/microsoft.speech.recognition.grammar.aspx), which was used to define the dictionary and the keywords/phrases to be detected. The Voice recognition module was built by leveraging the Microsoft Speech to Text API (https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/cognitive-services/speech/home), which converts voice inputs received by the users to text to be sent to the Chatbot module. The module receives detected keywords (greetings/farewell expressions and destinations) from the Chatbot module and makes VinMoov speak by playing audio files obtained from the conversion of text answers (greetings/farewell expressions and directions) into audio answers through the Microsoft Text to Speech API (https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/cognitive-services/speech/home). When a sound is to be reproduced, the robot’s face movements synchronization is activated, like in the physical robot.

The Navigation module is responsible for choosing the appropriate gestures from a pre-defined list like in the physical robot’s architecture.

Gestures were recorded in Blender using the keyframing technique, which required to define key poses of the bones and joints in the VinMoov’s rig on a timeline. It is worth observing that, in the VRM system, the map had to be slightly tilted towards the user in order to make it visible to him or her (the map placed on a plane orthogonal to the physical robot could not be seen on a screen). For this reason, the IK solutions used in the physical robot could not be directly applied to the virtual replica.

With the aim to guarantee that the VinMoov’s gestures are as much similar as possible to the physical robot’s sequence both in terms of bones’ and joints’ position as well as of timing, a functionality of Blender known as video reference was used. That is, a set of videos showing the physical robot while giving directions were recorded and projected on a semi-transparent plane (adjustable in size and position) placed on the VinMoov’s 3D model as a background reference for the VinMoov animation stage (basically leveraging the same idea of tracing paper to copy a drawing).

When the module receives the keywords identified by the Chatbot module, it loads the appropriate sequence of keyframes (an action, in the Blender’s terminology, representing a gesture) and the Gesture module deals with making the virtual robot use the correct direction-giving modality based on the current configuration.

Figure 9 illustrates the Interaction logic module, which was implemented by using the drag & drop-based Logic Editor integrated in Blender. To the left, the yellow blocks represent the Blender’s actions recorded in the Navigation module. To the bottom, the outputs of modules on the server side are connected to the inputs of modules on the client side through the scripts shown to the right.

Figure 9.

Implementation of the VinMoov’s interaction logic in Blender.

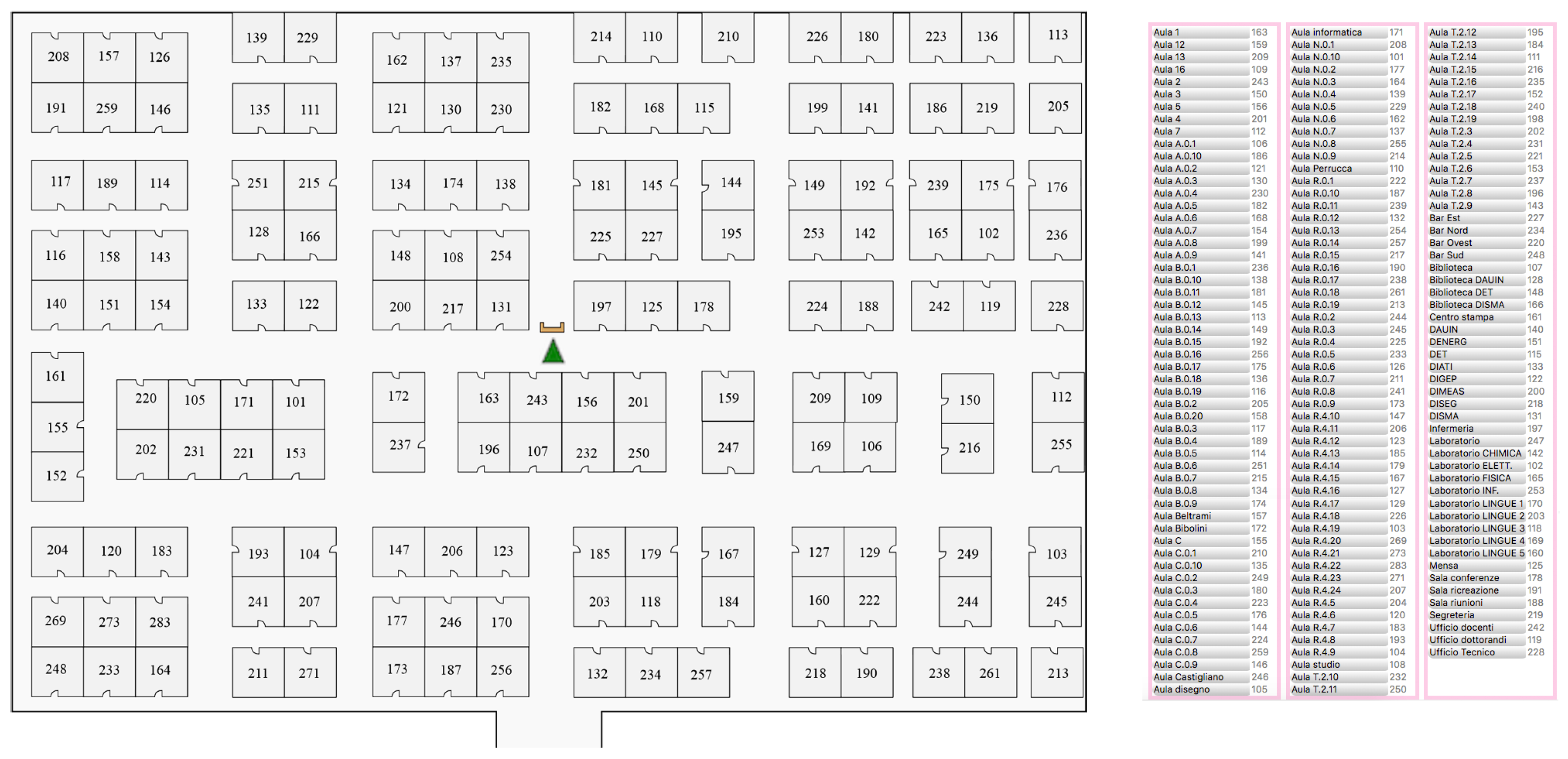

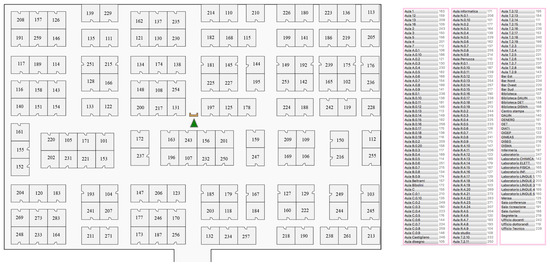

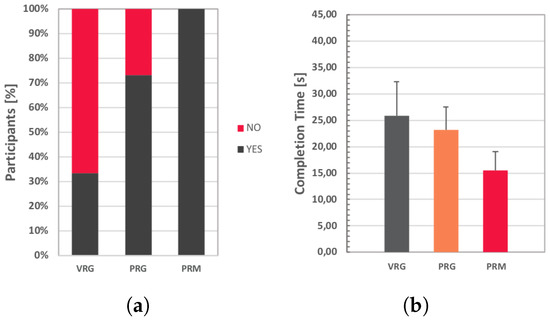

4.3. Interactive Map

A further receptionist system that was considered in this work is a 2D interactive audio-map, the appearance of which is illustrated in Figure 10. The map was displayed on the same monitor used for the virtual robot (though with a horizontal orientation, in this case). It uses a generalized and minimalistic visualization based on the architectural blueprint technique discussed in Section 2.1. Concerning orientation and user’s location, the map uses a YAH, forward-up representation. Precisely, a green triangle is used to indicate both the user’s location and orientation w.r.t. the environment. A light brown rectangle depicts the reception desk the map system is installed onto. The system is meant to refer to a number of destinations (rooms), which are listed in alphabetical order to the right of the map. Should the user select a destination by either clicking the corresponding box on the map or its name in the list, the map would display an animated colored path from the YAH mark to the requested destination. Based on the considerations emerging from the review in Section 2.1, and with the aim to limit the differences among receptionist systems considered in this work to their actual peculiarities in order to avoid biases as much as possible, it was decided to accompany the visual representation with the same voice directions that are uttered by the two receptionist robots. Voice input was not considered.

Figure 10.

Interactive map-based receptionist system.

The interactive map was implemented as a Web application by leveraging the wayfinding jQuery plugin (https://github.com/ucdavis/wayfinding), which allows for the creation of interactive SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics) maps. It supports the computation of the shortest path to a target location on the map based on information encoded in the SVG file and its visualization on the map. Information is stored in layers, which refer to rooms (defining clickable areas on the map), paths (line segments defining possible routes), and doors (end-points associating room names to paths’ ends).

Voice directions uttered while the path is drawn were developed by building on the Artyom JavaScript-based voice recognition and synthesis library (https://sdkcarlos.github.io/sites/artyom.html).

5. Experimental Results

In this section, experimental observations that were carried out to assess the effectiveness of the considered configurations in direction-giving tasks, as well as the way they were perceived as receptionist systems, are presented.

As discussed in Section 3, in this work three hypotheses were formulated, which were assessed by means of two user studies. The first study purported to assess whether the introduction of a map in a physically embodied robotic receptionist system could improve users’ understanding of the received route indications and their wayfinding abilities compared to an accepted direction-giving method found in the literature based on arm pointing gestures (Hypothesis 1). By grounding on findings of the first study, the second study was aimed, firstly, to investigate whether embodiment and social behaviors can boost users’ performance and acceptance of a receptionist system compared to no embodiment/no social behavior (Hypothesis 2) and, secondly, to study the added value of physical presence compared to a virtual representation (Hypothesis 3).

5.1. First User Study: Route Tracing on a Map or Arm Pointing Gestures?

This section illustrates the study performed to test the Hypothesis 1. Based on results from previous works discussed in Section 2, it can be recalled that the listener’s perspective represents the best option for embodied receptionist systems using arm pointing gestures. Moreover, when these gestures are used, physical robots are (to be) preferred to virtual ones. By leveraging the above considerations, this study compared a physical robot featuring a paper map on which it can show the route while giving voice directions (PRM) with a receptionist system featuring the same embodiment but using listener’s perspective arm pointing gestures (PRG). As mentioned previously, for the sake of completeness, for the latter configuration a virtual embodiment was also considered (VRG).

5.1.1. Experimental Setup and Procedure

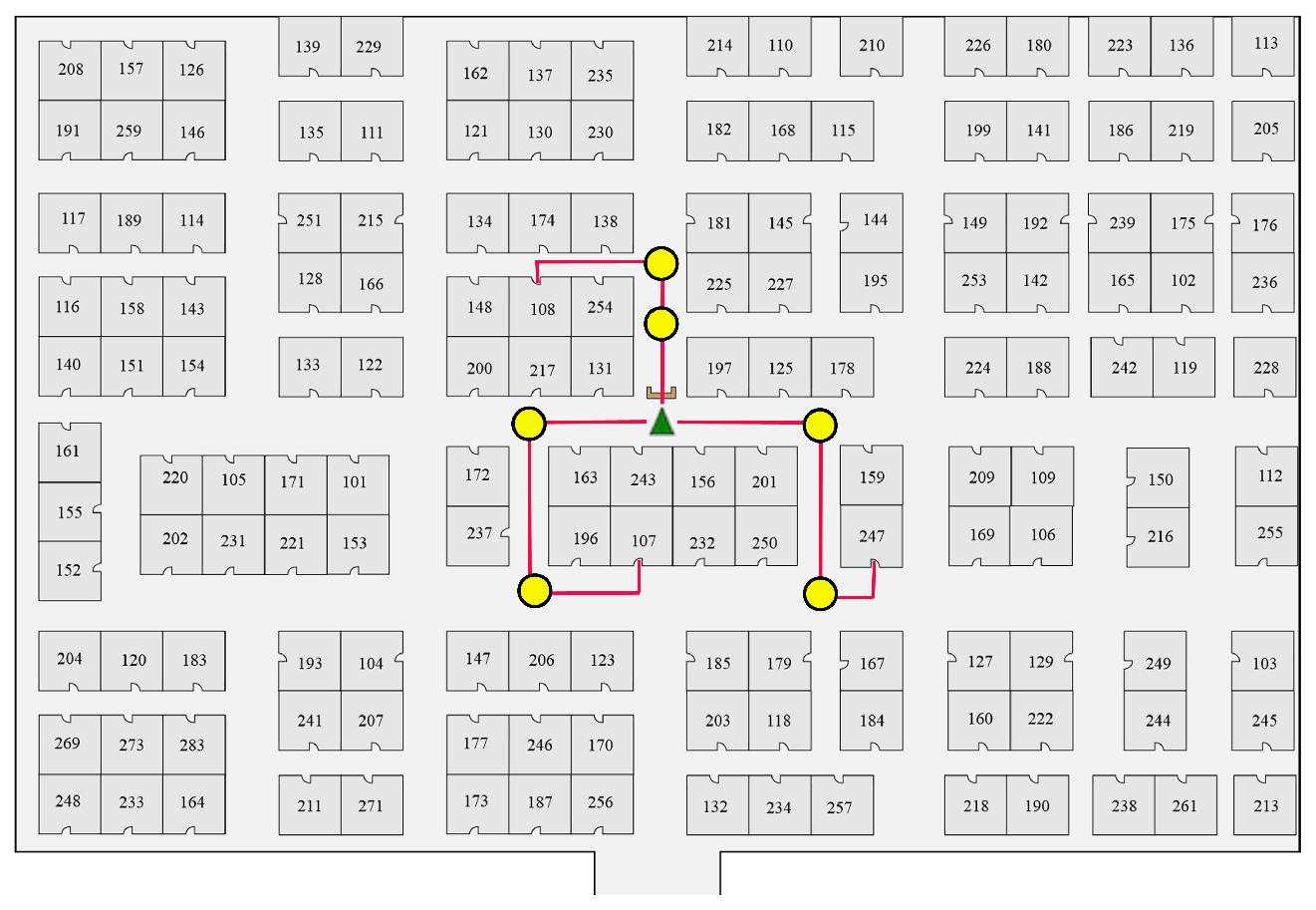

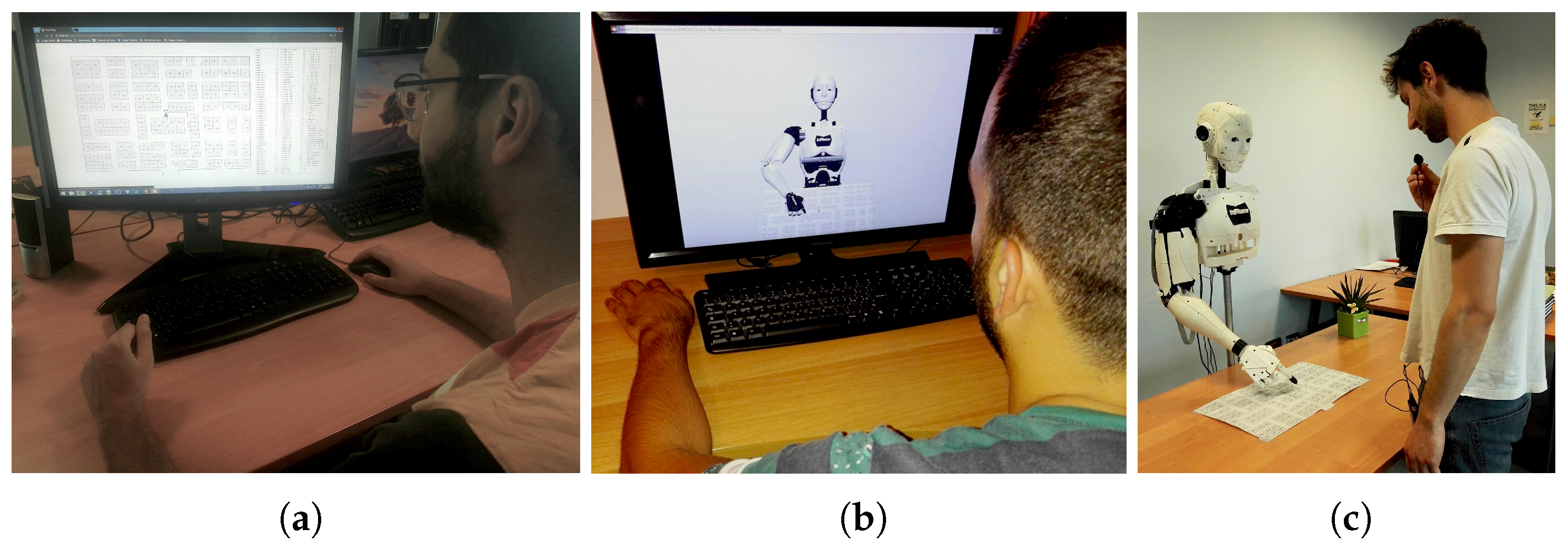

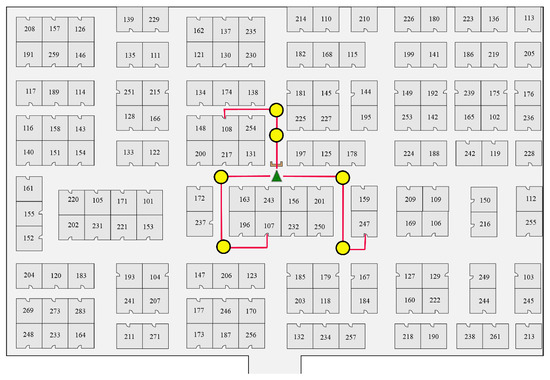

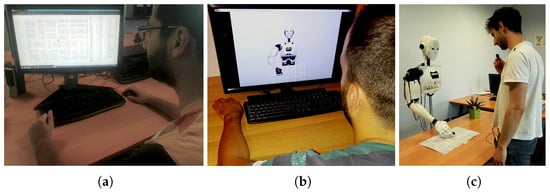

Experiments involved 15 volunteers (11 males and 4 females) aged between 21 and 29 years (M = 25.57 SD = 2.40), recruited among Italian-speaking students at Politecnico di Torino. Participants were told that, during the session, they had to interact with the three receptionist systems in Figure 11a–c (corresponding to configurations sketched in Figure 1) and ask them for directions to three different rooms—namely, library, secretary, and study room. Since the experiment had to solicit students’ wayfinding ability in an unknown university environment, a map representing a fictional environment was designed (Figure 12).

Figure 11.

First user study: (a) VRG; (b) PRG; and (c) PRM systems experimented.

Figure 12.

First user study: Configuration of the fictional environment considered to give directions.

Participants were informed that, at the end of each interaction with a receptionist system, they had to recall directions received to carry out a spatial navigation task. To this aim, a virtual environment was created by using a 3D simulator, thus giving participants the impression to navigate a realistic, though simplified, university location. The virtual environment was designed to create a strong connection with the experience just completed: To this aim, at the beginning of the simulation, participants faced a reception desk portraying the receptionist system considered.

To compensate for possible learning effects, the Latin square random ordering was used for choosing the order of both receptionist systems and rooms (one per receptionist system). The locations of the rooms and the paths to reach them were specifically designed in order to make them exhibit the same difficulty and make sure that possible differences in participants’ performance were only due to the particular receptionist system used. As shown in Figure 12, the path to each room always consisted of two consecutive crossing points (yellow circles in the figure).

It is worth observing that the use of the virtual navigation-based approach allowed to cope with possible biases in the evaluation that could be introduced, e.g., in strategies requiring the users to draw the route on a map (like in [63]). In fact, differently than users seeing the robot tracing the route on the map first, users getting gesture-based directions first would not see the map before being asked to draw it, with clear consequences on evaluation fairness. According to [16], the virtual navigation-based evaluation strategy is also more demanding than route drawing; hence, it should make differences between the various receptionist systems emerge in a clearer way.

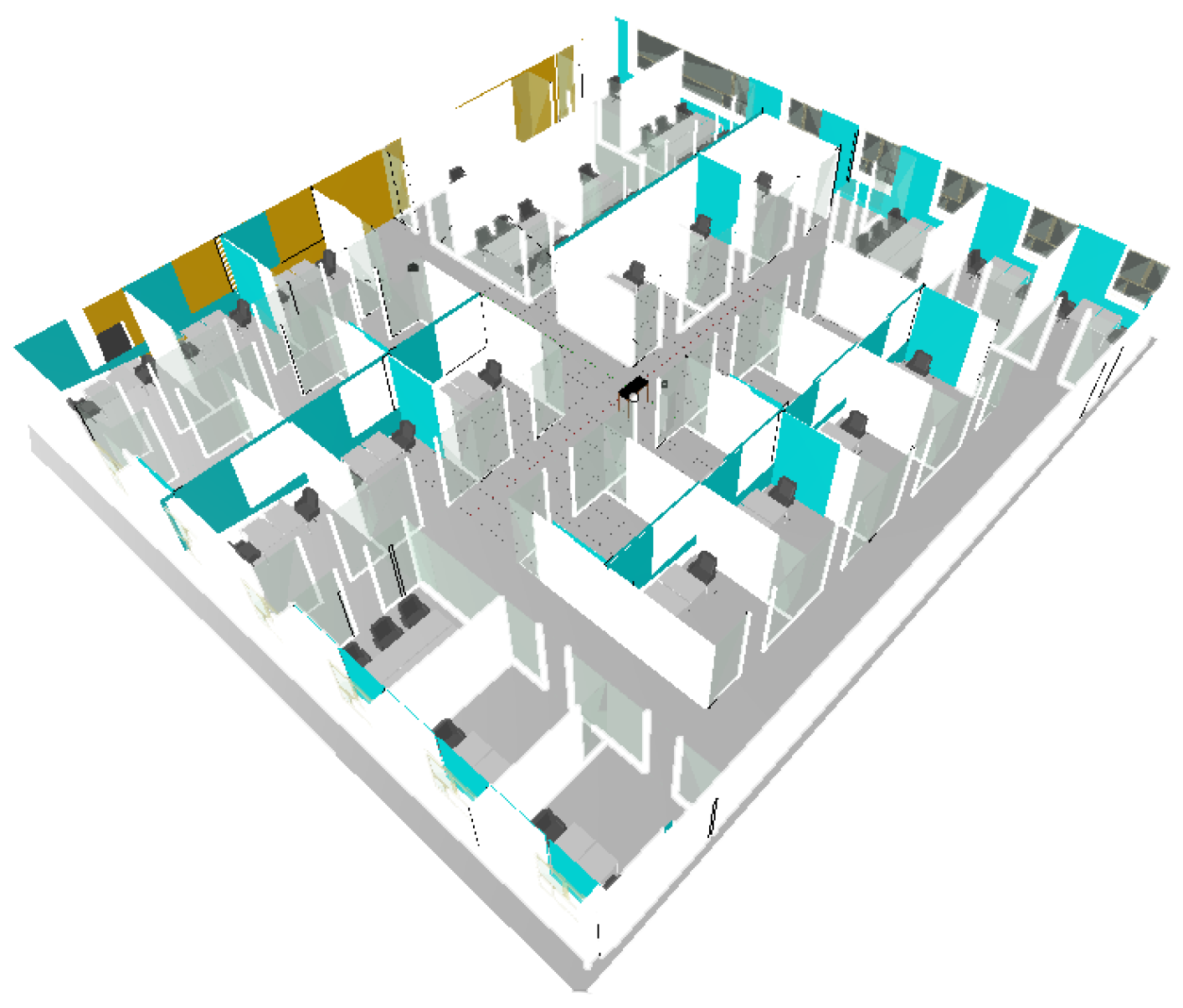

The 3D representation of the map used in the simulator is depicted in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

First user study: 3D reconstruction of the fictional university used during simulated navigation.

5.1.2. Measures

After having tested all the three receptionist systems (i.e., at the end of the session), participants were invited to fill in a usability questionnaire, by expressing their agreement with a number of questions/statements on a 5-point Likert scale (Table 1). A “Leave a comment below!” section was also provided in the questionnaire to collect participants’ comments.

Table 1.

First user study: Questions/statements in the questionnaire used for the subjective evaluation.

The questionnaire was split into two parts. The first part was designed by referring to three common usability factors. The first factor was related to participants’ satisfaction in using the systems, which was analyzed by leveraging questions Q1–Q4 selected (and adapted) from the Usefulness, Satisfaction, and Ease of use (USE) questionnaire [67] (only questions on satisfaction were considered). The second factor concerned users’ interaction with the receptionist system, which was investigated through questions Q5–Q14. These questions were adapted from the Virtual Reality Usability (VRUSE) questionnaire [68]. The third factor pertained visual feedback. Questions used to this purpose (Q15–Q17) were derived from a modified version of the VRUSE questionnaire [68]. The second part of the questionnaire was developed to assess the participants’ perception of each specific configuration as a receptionist system. As in [61,62], questions Q18–Q19 were used. For consistency reasons, scores for Q10, Q12, Q13, Q14, Q16, and Q17 were inverted so that higher scores reflect positive opinions.

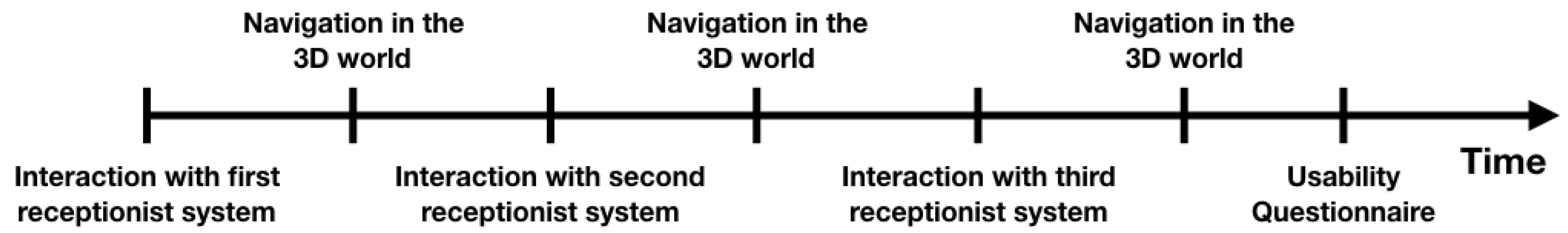

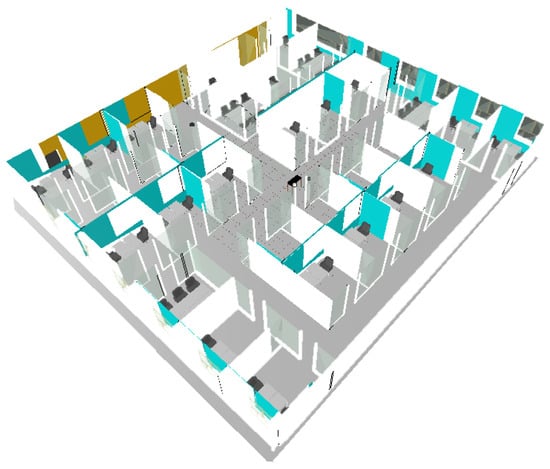

In order to ground the analysis also on objective data, for each receptionist system the time needed by the participants to reach the room, as well as its correctness (binary score, i.e., room correctly identified or not) were additionally recorded. The temporal organization of a session is reported in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

First user study: Temporal organization of the experiments.

Collected data were analyzed first through one-way repeated ANOVA test in order to check for possible differences in participants’ objective performance and subjective evaluation among the three receptionist systems. Afterwards, given the normal distribution of users’ ratings (Anderson-Darling Normality test), a post-hoc analysis was performed by using two-tailed paired t-tests for comparing the various systems.

5.1.3. Objective Observations

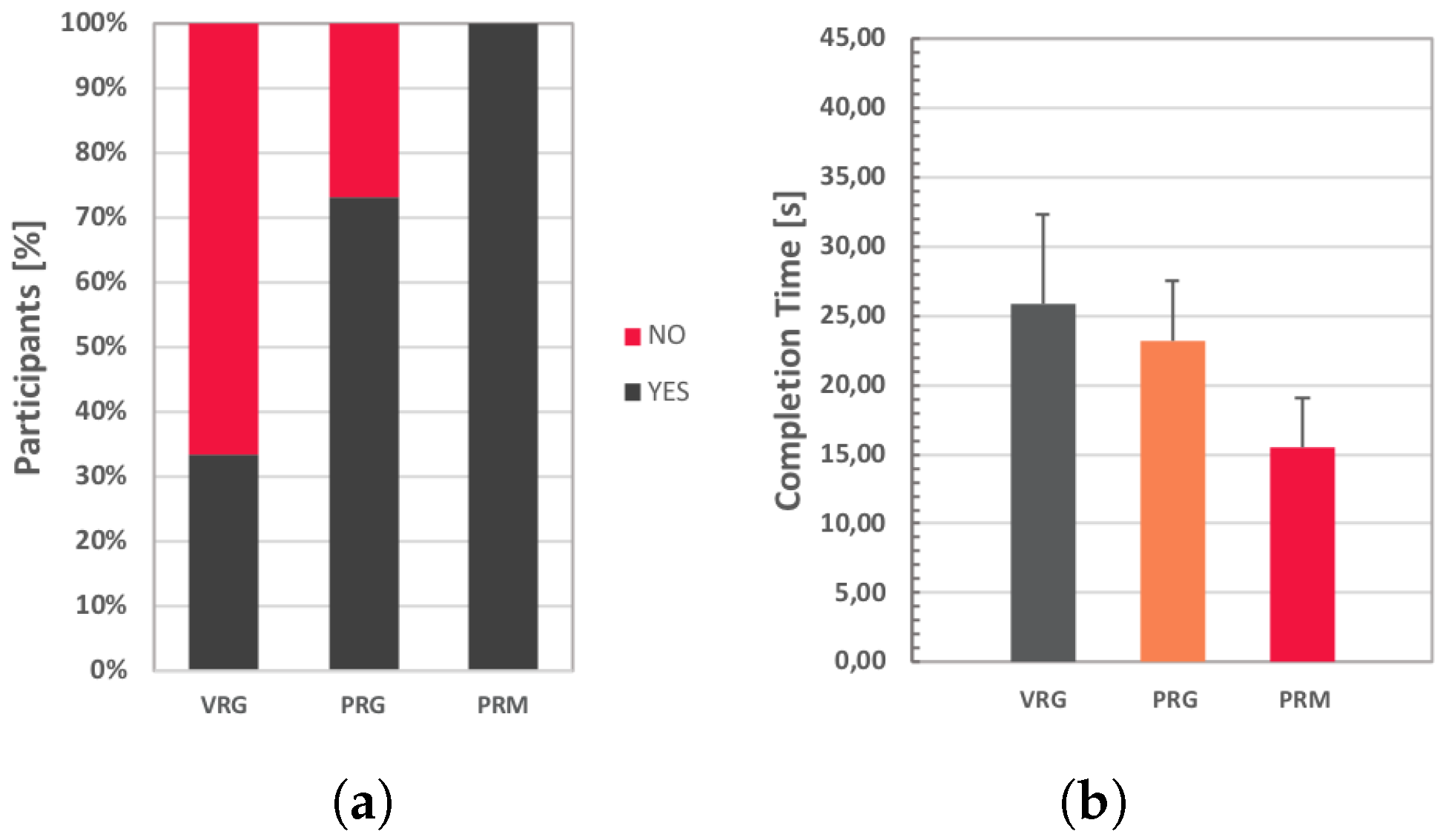

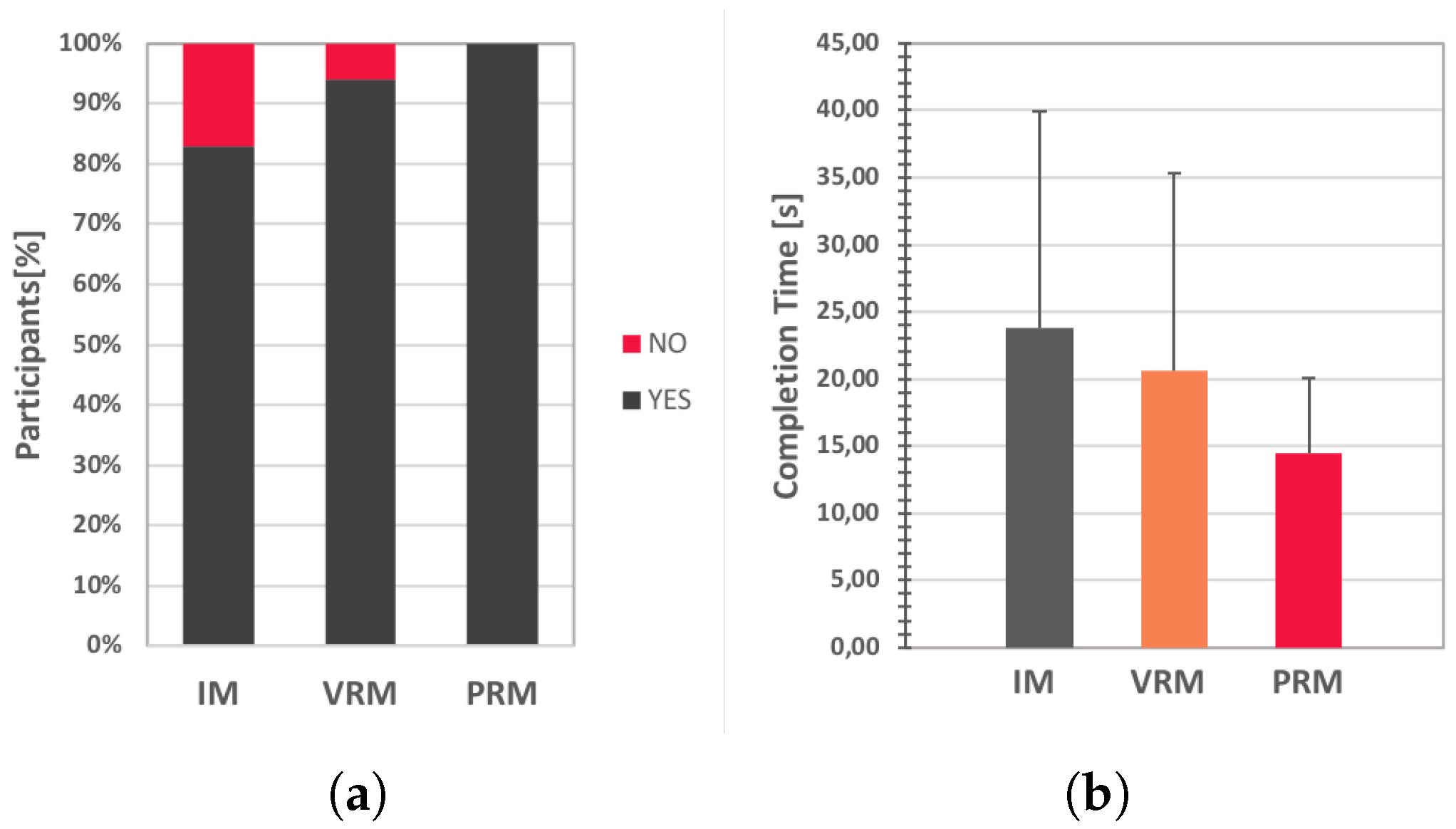

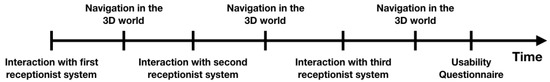

Results obtained in terms of correctness of room locations as well as of time spent are reported in Figure 15. From Figure 15a it can be immediately seen that when arm pointing gestures were used, only 33% and 73% of the participants were able to correctly identify the room (with the VRG and PRG systems, respectively). When a map was added (PRM system), 100% of the participants completed the task successfully.

Figure 15.

First user study: Objective results in terms of (a) success rate in finding the correct room and (b) average time needed to complete the task.

Average values for the completion time (Figure 15b) indicate that, with the configuration including the map (PRM), participants were faster than with arm pointing (VRG and PRG systems) in identifying the correct location of the room and draw the route to it (ANOVA: F(2,28) = , p = 1.72 ).

Post-hoc analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between VRG and PRG (t[14] = 1.89, p = 0.0799), confirming findings reported in [63]. However, differences between PRG and PRM (t[14] = 6.12, p = 2.66 ), as well as between VRG and PRM (t[14] = 4.96, p = 2.11 ), were found to be significant.

5.1.4. Subjective Observations

Results concerning the participants’ evaluations of the three receptionist systems gathered through the designed questionnaire and analyzed using ANOVA are illustrated in Table 2. Results were obtained by averaging scores among the participants. Table 3 shows the outcomes of the post-hoc analysis performed on the above results by using two-tailed paired t-tests. Statistically significant values are highlighted using a decremental lightness scale and + symbols.

Table 2.

First user study: Subjective results, average scores (and standard deviation); statistical significance determined with ANOVA is highlighted (+ p < 0.05, ++ p < 0.01, +++ p < 0.001).

Table 3.

First user study: Subjective results, post-hoc analysis with t-tests (+ p < 0.05, ++ p < 0.01, +++ p < 0.001).

By considering Table 2 and focusing on the satisfaction dimension, it can be observed that participants judged the PRM system as the most satisfactory receptionist solution (ANOVA: F(2,28) = 18.30, p = 8.27 ) in terms of pleasantness (Q1), operation expectations (Q2), fun (Q3), and satisfaction (Q4). This evidence is confirmed by the post-hoc analysis, indicating that PRM, on average, received higher scores that both the VRG and PRG solutions (all the questions in this category were statistically significant). When comparing the two versions that leverage arm pointing gestures, participants’ satisfaction was higher with the physical robot than with the virtual one.

Concerning user interaction, participants’ scores were higher with the PRM system than with the PRG and VRG systems (ANOVA: F(2,28) = 18.16, p = 8.78 ). However, according to post-hoc analysis, the difference between VRG and PRG systems is less marked than the differences between gesture-based and map-based receptionist systems. Focusing on statistically significant questions, participants were impressed by how simply they could interact with the PRM system compared to the PRG and VRG ones (Q6 and Q7), by also finding PRM system’s behavior more self-explanatory (Q11) than that of the other solutions. In fact, they felt disoriented when arm pointing gestures were used (Q10), with worse performance (Q12).

Participants’ judgments regarding visual feedback (including the appearance of the receptionist systems) indicated that the physical embodiments were more appreciated than the virtual embodiment (ANOVA: F(2,28) = 14.47, p = 4.83 ). This evidence is also confirmed by the post-hoc analysis. In fact, the difference between PRG and PRM system is not statistically significant, differently than differences between virtual and physically embodied systems. In particular, it is worth noticing that all the questions belonging to this category proved to be statistically significant only when virtual and physical embodiments were compared. The PRG and PRM systems were considered as more visually pleasant than the VRG (Q15), which in turn was regarded as less engaging (Q17) and as responsible for worse performance (Q16).

Regarding the evaluation of the considered configurations as receptionist systems (receptionist role dimension), the participants judged the PRM system more positively than the other two solutions (ANOVA: F(2,28) = 13.34 p = 8.53 ). Post-hoc analysis showed that there is no significant difference between VRG and PRG systems, whereas the PRM system was preferred to both the VRG and PRG systems (with both questions belonging to this category statistically significant).

5.1.5. Discussion

In this study, the impact of using a map integrated with a physical robot in a direction-giving task was addressed. Findings confirmed Hypothesis 1 and supported it both in terms of objective and subjective evaluations. In fact, participants found it easier and faster to find their destination when the robot showed them directions on a map rather than when it used arm pointing gestures. Based also on the comments provided after the experiments, preference appears to be mainly motivated by to fact that, with the introduction of the map, all the participants were able to better understand and remember the route described by the robot. A frequent quote gathered during the experiment was: “Merging robot’s voice directions with a visual illustration/image of the environment that I had to explore allowed me to mentally see the route I had to travel in order to reach the place I wanted to go”. The difference among the three configurations emerges in a rather clear way also considering the usability analysis conducted through the first part of the questionnaire. In fact, the robot with the map was the preferred configuration for what it concerns both satisfaction and user interaction, followed by the physical robot using arm pointing gestures. No significant difference was found in terms of visual feedback between map and arm pointing gestures for the physically embodied systems, whereas the virtual embodied robot was judged as responsible for worse performance. Another interesting quote was: “I was able to understand the directions given by both the physical robot and the virtual robot; however, when I had to use directions given by the virtual robot to find the right path to follow for reaching the indicated place, I realized that I had partially forgotten them”. Concerning questions related to the robots’ suitability as receptionists, the map-based configuration was evaluated as the best one, whereas no difference was found between the two systems using arm pointing gestures.

5.2. Second User Study: The Role of Embodiment and Social Behavior

In the study conducted in [63], which was discussed in Section 3, the authors demonstrated that there is no difference in the effectiveness of direction-giving solutions between physical/virtual robots using arm pointing gestures and voice-enabled map-based systems. By focusing only the type of embodiment, they inferred that this result was probably due to the fact that, in the scenario considered, the embodied systems were used to give directions to a destination which was not visible to participants. Thus, differences between physicality and virtuality did not come into play.

In the first user study reported in the present paper, a robot-based direction-giving solution based on arm pointing gestures was compared with a robotic receptionist system able to show the path to follow on a map. The application scenario is comparable to that tackled in [63], as a not visible, in this case even non-existing, destination is considered. However, a statistically significant preference was found for the use of the map, which also allowed participants to achieve better performance in localizing the intended destination. The difference, here, was in the direction-giving system used rather than in the type of embodiment adopted.

By moving from these results, this section reports on a second user study that was designed to investigate whether different embodiments (i.e., physical or virtual) of a socially interactive receptionist robot may influence users’ perception and performance in wayfinding tasks compared to a map-only (unembodied) solution without social behaviors (Hypothesis 2).

Moreover, like in [63], the second study also considered the type of embodiment, by investigating possible changes in participants’ preference or performance when physically vs. virtually embodied systems are used in wayfinding tasks (Hypothesis 3).

Hence, the receptionist systems (all featuring a map) experimented in this study are the PRM, the VRM, and the IM ones.

5.2.1. Experimental Setup and Procedure

Participants involved in the study (11 males and 7 females) aged between 21 and 26 years (M = 23.17, SD = 1.42), were selected from Politecnico di Torino’s students by avoiding overlaps with the group of subjects who participated in the first study. Participants were provided with the same instructions given in the first study, and were requested to interact with all the three receptionist systems in Figure 16a–c (corresponding to configurations depicted in Figure 2). Experiments were carried out like in the first study, with the receptionist systems selected according to the Latin square random order and rooms chosen in a random way.

Figure 16.

Second user study: (a) IM; (b) VRM; and (c) PRM systems experimented.

5.2.2. Measures

Similarly to the first study, quantitative data gathered during the second study concerned time required to reach the destination in the 3D environment and number of participants who get lost. Subjective feedback was collected by means of a questionnaire split in four parts, which included the same questions used in the first study plus new questions designed to investigate possible differences between the receptions systems’ embodiments in greater detail.

The first part was designed to study systems’ usability, taking into account a number of factors (measured on a 5-point Likert scale). First, ease of use, ease of learning, and participants’ satisfaction in using the systems were analyzed. For the first two factors, questions Q1–Q3 and Q4–Q6 in Table 4 were used, whereas satisfaction was measured using the same questions used in the first study (Table 1). Then the Nielsen’s attributes of usability (NAU) [58] were considered, in order to study learnability, efficiency, memorability, and errors perspectives. Lastly, an adapted version of the Virtual Reality Usability (VRUSE) questionnaire [68] was used to evaluate participants’ experience concerning five dimensions, i.e., functionality, user interaction, visual feedback, consistency, and engagement. Specifically, for the functionality dimension (control that participants had over the systems), Q7–Q10 in Table 4 were used. User interaction and visual feedback dimensions were investigated using questions used already in the first study (Table 1). Consistency dimension was assessed using questions Q11–Q15 in Table 4. Lastly, the engagement dimension was studied by means of questions Q16–Q23 in Table 4.

Table 4.

Second user study: Selection of statements in the questionnaire used for the subjective evaluation (not including those re-used from the first user study or concerning aspects addressed via other methods).

The second part was developed to evaluate the interaction with the considered systems and the way they are perceived in the receptionist role (on a 5-point Likert scale). The first perspective was assessed by pursuing the approach in [69], i.e., by asking participants to evaluate the entertainment of the interaction through six attributes: enjoyable, interesting, fun, satisfying, entertaining, boring, and exciting. The second perspective was investigated by questions Q24–Q27 in Table 4 (derived from [61,62,69]).

The third part consisted in a direct comparison of the three solutions. In particular, like in [69], participants were asked to rank them with respect to nine evaluation categories: Enjoy more, more intelligent, more useful, prefer as receptionist, more frustrating, more boring, more interesting, more entertaining, and chose from now on.

The fourth part was designed to investigate the role of the embodiment and its possible impact on perceived systems’ effectiveness and social attractiveness. Only the virtual and physical embodiments were considered in this part, by asking participants to evaluate the VRM and PRM systems w.r.t. five dimensions. The first three dimensions, i.e., companionship, usefulness, and intelligence had to be evaluated according to the semantic scale defined in [69,70]. The fourth dimension, social attraction, was assessed through questions Q28–Q31 in Table 4. The last dimension, social presence, was evaluated by means of an adapted version of the Interpersonal Attraction Scale [71] (unsociable/sociable, impersonal/personal, machine-like/life-like, insensitive/sensitive) and questions Q32–Q33 in Table 4. A 10-point scale was used for all the dimensions.

Data collected were analyzed using one-way repeated ANOVA and two-tailed paired t-test (given the normal distribution of user ratings assessed through Anderson-Darling Normality test), like in the first study.

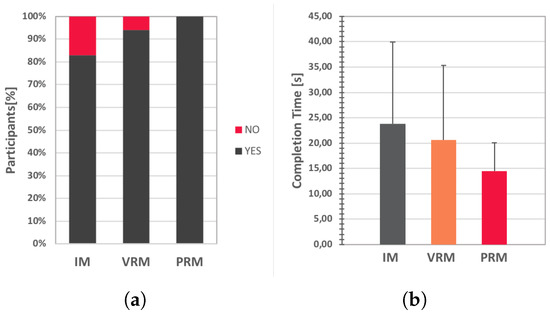

5.2.3. Objective Observations

Results obtained in terms of percentage of participants who succeeded in reaching the intended destination as well as of time requested to accomplish the task are reported in Figure 17. With the IM and the VRM systems, 17% and 6% of the participants were not able to reach the destination, respectively. Only when using the PRM system did 100% of the participants successfully completed the wayfinding task, like in the first user study.

Figure 17.

Second user study: Objective results in terms of (a) success rate in finding the correct room and (b) average time needed to complete the task.

Concerning completion time, ANOVA confirmed the statistical significance of differences among average values (ANOVA: F(2,34) = 3.95 p = 0.0286). According to the post-hoc analysis, participants were faster with the PRM system than with the IM and VRM systems (t[17] = 2.72, p = 0.0146 and t[17] = 2.13, p = 0.0476, respectively).

5.2.4. Subjective Observations

The results concerning participants’ evaluations (average scores) of the two embodied receptionist systems (with social skills) and the map-based system (without social skills) gathered by the first two parts of the questionnaire and analyzed with ANOVA are reported in Table 5. The outcomes of the post-hoc analysis on the same data are illustrated in Table 6.

Table 5.

Second user study: subjective results, average scores (and standard deviation); statistical significance determined with ANOVA is highlighted (+ p < 0.05, ++ p < 0.01, +++ p < 0.001).

Table 6.

Second user study: Subjective results (first two parts of the questionnaire), post-hoc analysis with t-tests (+ p < 0.05, ++ p < 0.01, +++ p < 0.001).

As can be seen from results in Table 5 concerning usability, the comparison showed a strong preference for the physical robot over the virtual robot and the map for all the dimensions considered, except the ease of learning and errors ones. All the receptionist systems were judged by participants as quick and easy to learn, and allowing them to easily recover from errors.

Concerning the ease of use dimension, the participants rated the PRM system as easier to use and more user-friendly that the VRM and the IM systems (although, according to the post-hoc analysis, the difference between the VRM and PRM systems was pronounced, but not reaching significance). A similar consideration applies also to the satisfaction dimension. In fact, by considering questions Q1–Q4, the PRM system was more satisfactory, fun and pleasant to use than the VRM and IM ones; however, no significant difference was found between the two embodied robots.

Considering the learnability and efficiency, dimensions, it can be noticed that participants perceived the PRM as capable to let them complete the task more easily the first time they used it and to be more effective once they learned to use it than with both the VRM and IM systems; IM and VRM are judged similarly for what it concerns learnability, whereas the VRM system is evaluated more positively than the IM one in terms of efficiency.