Actinobacteria–Plant Interactions in Alleviating Abiotic Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

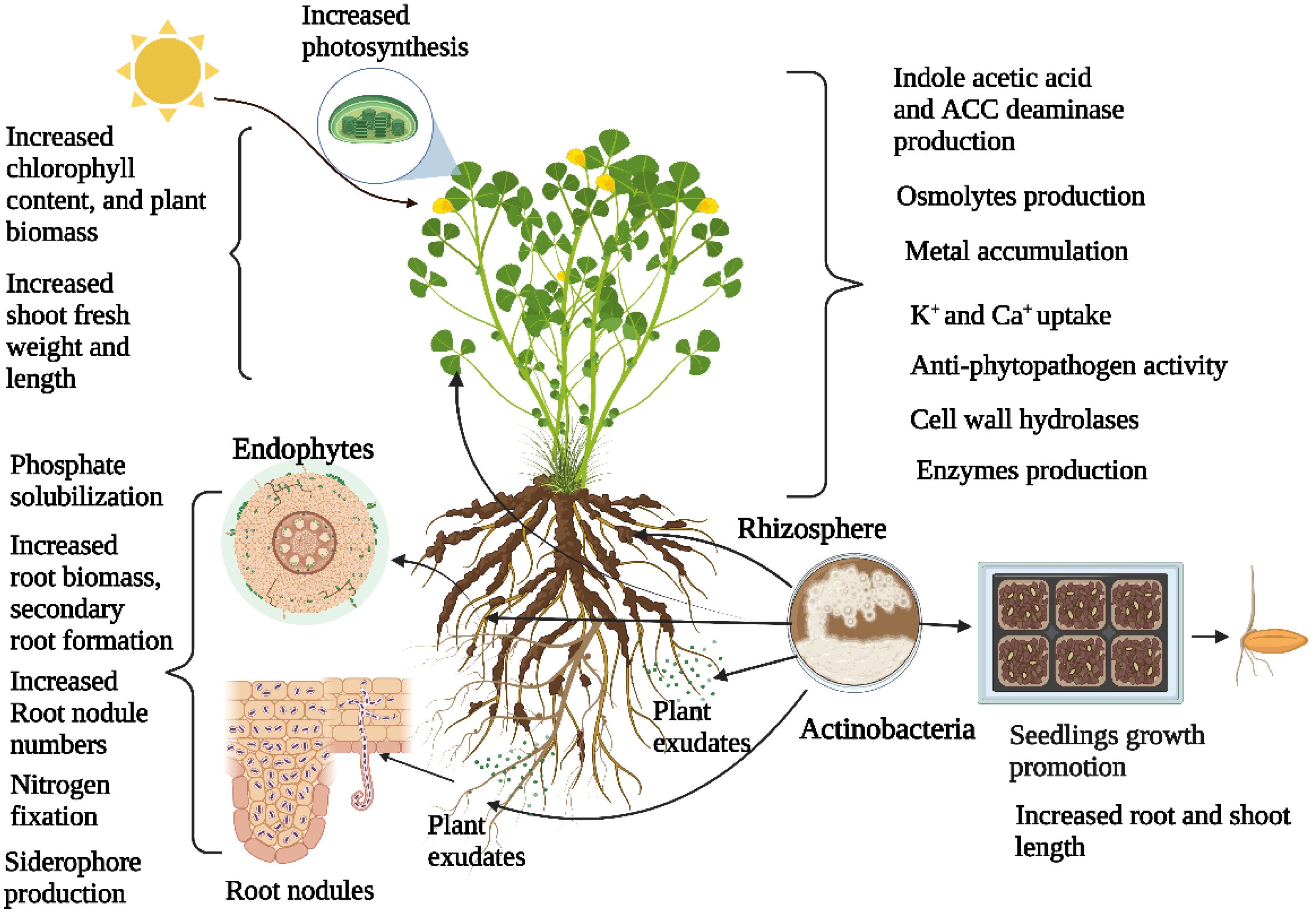

2. Actinobacteria Diversity Associated with Plants and Plant Growth Promotion

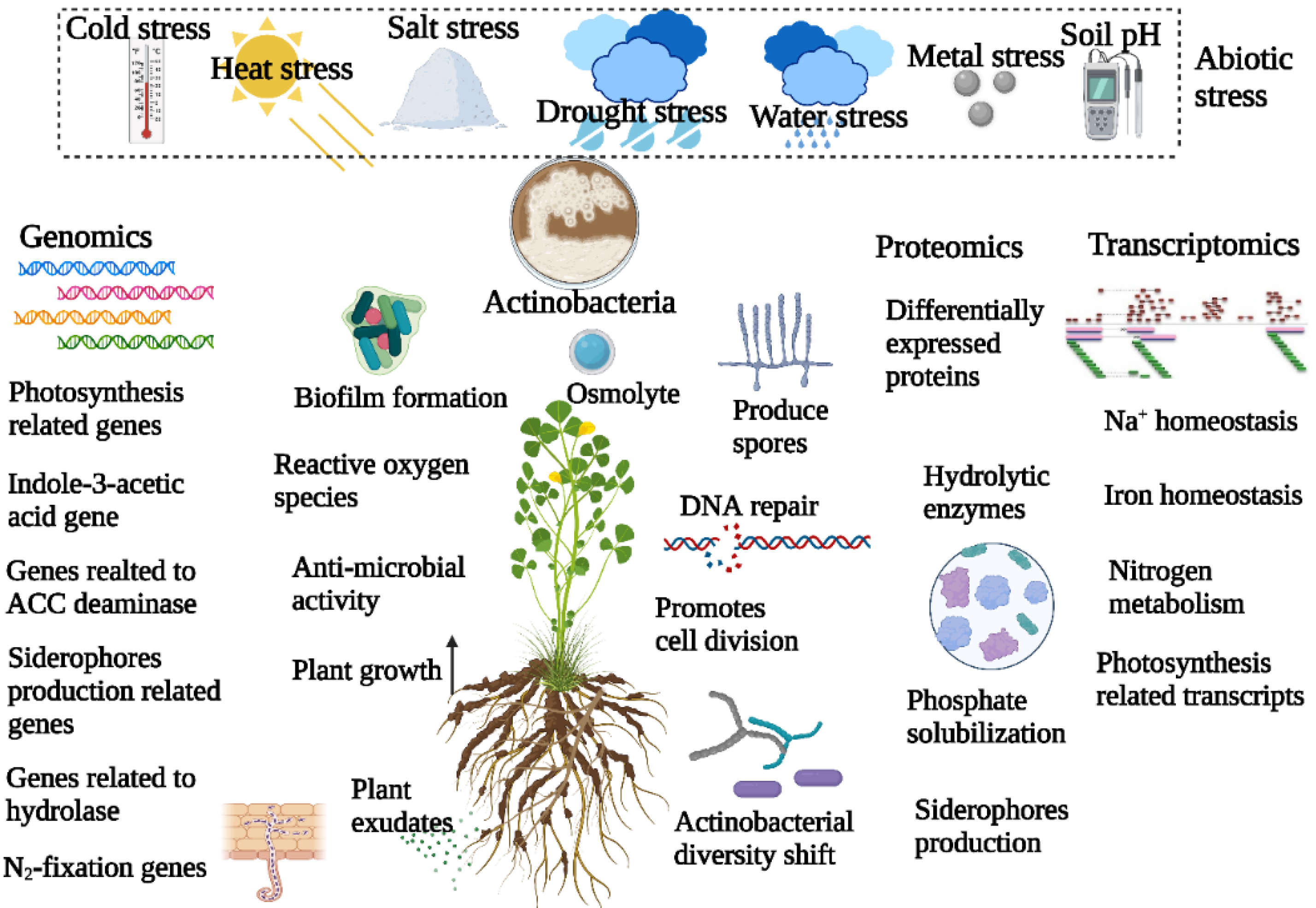

3. Effect of Abiotic Stress on Actinobacterial Diversity in Plant Microbiome

4. Role of Actinobacteria in Overcoming Plant Abiotic Stress

5. Genomics Approaches to Understand Actinobacteria-Mediated Alleviation of Abiotic Stress in Plants

6. Transcriptomics and Proteomics Approaches to Understand Actinobacterial Alleviation of Abiotic Stress in Plants

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Imran, Q.M.; Falak, N.; Hussain, A.; Mun, B.-G.; Yun, B.-W. Abiotic stress in plants; Stress perception to molecular response and role of biotechnological tools in stress resistance. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, J.-K. Thriving under stress: How plants balance growth and the stress response. Dev. Cell 2020, 55, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, J.S. Plant productivity and environment. Science 1982, 218, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahluwalia, O.; Singh, P.C.; Bhatia, R. A review on drought stress in plants: Implications, mitigation and the role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 5, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, G.R.; Urano, K.; Delrot, S.; Pezzotti, M.; Shinozaki, K. Effects of abiotic stress on plants: A systems biology perspective. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishna, A.; Ravishankar, G.A. Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2011, 6, 1720–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Osakabe, Y.; Osakabe, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Tran, L.S. Response of plants to water stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.A.; Hussain, S.; Khaliq, A.; Ashraf, U.; Anjum, S.A.; Men, S.; Wang, L. Chilling and drought stresses in crop plants: Implications, cross talk, and potential management opportunities. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, N.G.; Beerling, D.J.; Breshears, D.D.; Fisher, R.A.; Raffa, K.F.; Stitt, M. The interdependence of mechanisms underlying climate-driven vegetation mortality. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osakabe, K.; Osakabe, Y. Plant light stress. In Encyclopaedia of Life Sciences; Robinson, S., Ed.; Nature Publishing Group: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Su, D.; Yang, D.; Dong, T.; Tang, Z.; Li, H.; Han, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B. Chilling and heat stress-Induced physiological changes and microRNA-Related mechanism in sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazel, J.R. Thermal adaptation in biological membranes: Is homeoviscous adaptation the explanation? Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1995, 57, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; He, C.Q.; Ding, N.Z. Abiotic stresses: General defenses of land plants and chances for engineering multistress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narsing Rao, M.P.; Dong, Z.-Y.; Xiao, M.; Li, W.-J. Effect of salt stress on plants and role of microbes in promoting plant growth under salt stress. In Microorganisms in Saline Environments: Strategies and Functions; Giri, B., Varma, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 423–435. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, B.; Huang, B. Mechanism of salinity tolerance in plants: Physiological, biochemical, and molecular characterization. Int. J. Genom. 2014, 2014, 701596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghori, N.H.; Ghori, T.; Hayat, M.Q.; Imadi, S.R.; Gul, A.; Altay, V.; Ozturk, M. Heavy metal stress and responses in plants. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 1807–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Wei, Z.; Li, J.H. Effects of copper on leaf membrane structure and root activity of maize seedling. Bot. Stud. 2014, 55, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, A.; Zaidi, A.; Ameen, F.; Ahmed, B.; AlKahtani, M.D.F.; Khan, M.S. Heavy metal induced stress on wheat: Phytotoxicity and microbiological management. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 38379–38403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inbaraj, M.P. Plant-Microbe interactions in alleviating abiotic stress-A mini review. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 667903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, K.; Devi, S.; Singh, A.; Kaur, V.; Kumar, J.; Arya, S.S. Microorganisms: The viable approach for mitigation of abiotic stress. In Plant Stress Mitigators: Action and Application; Vaishnav, A., Arya, S.S., Choudhary, D.K., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 323–339. [Google Scholar]

- Yandigeri, M.S.; Meena, K.K.; Singh, D.; Malviya, N.; Singh, D.P.; Solanki, M.K.; Yadav, A.K.; Arora, D.K. Drought-Tolerant endophytic actinobacteria promote growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum) under water stress conditions. Plant Growth Regul. 2012, 68, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, G.; Köberl, M.; Rybakova, D.; Müller, H.; Grosch, R.; Smalla, K. Plant microbial diversity is suggested as the key to future biocontrol and health trends. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fix050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaemsaeng, R.; Jantasuriyarat, C.; Thamchaipenet, A. Molecular interaction of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase (ACCD)-Producing endophytic Streptomyces sp. GMKU 336 towards salt-stress resistance of Oryza sativa L. cv. KDML105. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastogeer, K.M.G.; Tumpa, F.H.; Sultana, A.; Akter, M.A.; Chakraborty, A. Plant microbiome—An account of the factors that shape community composition and diversity. Curr. Plant Biol. 2020, 23, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, L.; Birch, P. A systems biology perspective on plant-microbe interactions: Biochemical and structural targets of pathogen effectors. Plant Sci. 2011, 180, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compant, S.; Samad, A.; Faist, H.; Sessitsch, A. A review on the plant microbiome: Ecology, functions, and emerging trends in microbial application. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 19, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fierer, N.; Jackson, R.B. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Deng, Y.; Shen, L.; Wen, C.; Yan, Q.; Ning, D.; Qin, Y.; Xue, K.; Wu, L.; He, Z.; et al. Temperature mediates continental-scale diversity of microbes in forest soils. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Yao, Y.; Wang, R.; Wu, T.; Chai, B. Dynamics eelationship of phyllosphere and rhizosphere bacterial communities during the development of Bothriochloa ischaemum in copper tailings. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhu, K.; Wurzburger, N.; Zhang, J. Relationships between plant diversity and soil microbial diversity vary across taxonomic groups and spatial scales. Ecosphere 2020, 11, e02999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.J.; Wang, L.L.; Li, Q.; Shang, Q.M. Bacterial communities in the rhizosphere, phyllosphere and endosphere of tomato plants. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N. Embracing the unknown: Disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barka, E.A.; Vatsa, P.; Sanchez, L.; Gaveau-Vaillant, N.; Jacquard, C.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Klenk, H.P.; Clément, C.; Ouhdouch, Y.; van Wezel, G.P. Taxonomy, physiology, and natural products of Actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, D.H.; Abdallah, N.A.; Abolmaaty, A.; Tolba, S.; Wellington, E.M. Microbiological and molecular insights on rare Actinobacteria harboring bioactive prospective. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2020, 44, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackebrandt, E.; Rainey, F.A.; Ward-Rainey, N.L. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1997, 47, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, N.; Jiao, J.-Y.; Zhang, X.-T.; Li, W.-J. Update on the classification of higher ranks in the phylum Actinobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 1331–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, C. Morphological identification of actinobacteria. In Actinobacteria; Dhanasekaran, D., Jiang, Y., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016; pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, D.; Huber, K.J.; Tindall, B.; Hedrich, S.; Rojas-Villalobos, C.; Quatrini, R.; Dinamarca, M.A.; Ibacache-Quiroga, C.; Schwarz, A.; Canales, C.; et al. Acidiferrimicrobium australe gen. nov., sp. nov., an acidophilic and obligately heterotrophic, member of the Actinobacteria that catalyses dissimilatory oxido-reduction of iron isolated from metal-rich acidic water in Chile. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 3348–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.Y.; Wang, B.J.; Jiang, C.Y.; Liu, S.J. Micrococcus flavus sp. nov., isolated from activated sludge in a bioreactor. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, H.J. Review of the taxonomy of the genus Arthrobacter, emendation of the genus Arthrobacter sensu lato, proposal to reclassify selected species of the genus Arthrobacter in the novel genera Glutamicibacter gen. nov., Paeniglutamicibacter gen. nov., Pseudoglutamicibacter gen. nov., Paenarthrobacter gen. nov. and Pseudarthrobacter gen. nov., and emended description of Arthrobacter roseus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, D.M.; Quadri, S.R.; Cheng, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, W.; Yang, Y.; Hozzein, W.N.; Lingappa, K.; Li, W.J. Sinomonas mesophila sp. nov., isolated from ancient fort soil. J. Antibiot. 2015, 68, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locci, R.; Schaal, K.P. Apical growth in facultative Anaerobic actinomycetes as determined by immunofluorescent labeling. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. A 1980, 246, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Sakane, T.; Nihira, T.; Yamada, Y.; Imai, K. Corynebacterium terpenotabidum sp. nov., a bacterium capable of degrading squalene. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1999, 49 Pt 1, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lechevalier, M.P. Description of a new species, Oerskovia xanthineolytica, and emendation of Oerskovia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1972, 22, 260–264. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo, M.E.; Riesco, R.; Benito, P.; Carro, L. Endophytic actinobacteria and the interaction of Micromonospora and nitrogen fixing plants. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strap, J.L. Actinobacteria–plant interactions: A boon to agriculture. In Bacteria in Agrobiology: Plant Growth Responses; Maheshwari, D.K., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 285–307. [Google Scholar]

- Hamedi, J.; Mohammadipanah, F. Biotechnological application and taxonomical distribution of plant growth promoting actinobacteria. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 42, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Xie, L. Plant growth promoting and stress mitigating abilities of soil born microorganisms. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2020, 11, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, M.; Suresh, D. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria-Alleviators of abiotic stresses in soil: A review. Pedosphere 2020, 30, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narsing Rao, M.P.; Li, W.-J. Diversity of actinobacteria in various habitats. In Actinobacteria: Microbiology to Synthetic Biology; Karthik, L., Ed.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gouda, S.; Kerry, R.G.; Das, G.; Paramithiotis, S.; Shin, H.-S.; Patra, J.K. Revitalization of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for sustainable development in agriculture. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 206, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bais, H.P.; Weir, T.L.; Perry, L.G.; Gilroy, S.; Vivanco, J.M. The role of root exudates in rhizosphere interactions with plants and other organisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.N.; Verma, P.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, M.; Kumari Sugitha, T.C.; Singh, B.P.; Saxena, A.K.; Dhaliwal, H.S. Chapter 2-Actinobacteria from rhizosphere: Molecular diversity, distributions, and potential biotechnological applications. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Singh, B.P., Gupta, V.K., Passari, A.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 13–41. [Google Scholar]

- Jog, R.; Pandya, M.; Nareshkumar, G.; Rajkumar, S. Mechanism of phosphate solubilization and antifungal activity of Streptomyces spp. isolated from wheat roots and rhizosphere and their application in improving plant growth. Microbiology 2014, 160, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilagam, R.; Hemalatha, N. Plant growth promotion and chilli anthracnose disease suppression ability of rhizosphere soil actinobacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 126, 1835–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokala, R.K.; Strap, J.L.; Jung, C.M.; Crawford, D.L.; Salove, M.H.; Deobald, L.A.; Bailey, J.F.; Morra, M.J. Novel plant-microbe rhizosphere interaction involving Streptomyces lydicus WYEC108 and the pea plant (Pisum sativum). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 2161–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdElgawad, H.; Abuelsoud, W.; Madany, M.M.Y.; Selim, S.; Zinta, G.; Mousa, A.S.M.; Hozzein, W.N. Actinomycetes enrich soil rhizosphere and improve seed quality as well as productivity of legumes by boosting nitrogen availability and metabolism. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam Palaniyandi, S.; Yang, S.H.; Damodharan, K.; Suh, J.W. Genetic and functional characterization of culturable plant-beneficial actinobacteria associated with yam rhizosphere. J. Basic Microbiol. 2013, 53, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Han, L.; Jiang, B.; Long, C. Identification of a phosphorus-solubilizing Tsukamurella tyrosinosolvens strain and its effect on the bacterial diversity of the rhizosphere soil of peanuts growth-promoting. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamreihao, K.; Ningthoujam, D.S.; Nimaichand, S.; Singh, E.S.; Reena, P.; Singh, S.H.; Nongthomba, U. Biocontrol and plant growth promoting activities of a Streptomyces corchorusii strain UCR3–16 and preparation of powder formulation for application as biofertilizer agents for rice plant. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 192, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alekhya, G.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Biological control and plant growth-promotion traits of Streptomyces species under greenhouse and field conditions in chickpea. Agric. Res. 2017, 6, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Pérez, J.M.; González-García, S.; Cobos, R.; Olego, M.; Ibañez, A.; Díez-Galán, A.; Garzón-Jimeno, E.; Coque, J.J.R. Use of endophytic and rhizosphere Actinobacteria from grapevine plants to reduce nursery fungal graft infections that lead to young grapevine decline. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01564-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Carvalhais, L.C.; Crawford, M.; Singh, E.; Dennis, P.G.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Schenk, P.M. Inner plant values: Diversity, colonization and benefits from endophytic bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golinska, P.; Wypij, M.; Agarkar, G.; Rathod, D.; Dahm, H.; Rai, M. Endophytic actinobacteria of medicinal plants: Diversity and bioactivity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2015, 108, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhurama, G.; Sonam, D.; Urmil, P.G.; Ravindra, N.K. Diversity and biopotential of endophytic actinomycetes from three medicinal plants in India. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 8, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meij, A.; Willemse, J.; Schneijderberg, M.A.; Geurts, R.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; van Wezel, G.P. Inter- and intracellular colonization of Arabidopsis roots by endophytic actinobacteria and the impact of plant hormones on their antimicrobial activity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2018, 111, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaham, D.; Deltredici, P.; Torrey, J.G. Isolation and cultivation in vitro of the Actinomycete causing root nodulation in Comptonia. Science 1978, 199, 899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marappa, N.; Ramachandran, L.; Dharumadurai, D.; Nooruddin, T. Plant growth-promoting active metabolites from Frankia spp. of Actinorhizal Casuarina spp. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 191, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, V.C.; Gond, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, A.; Kharwar, R.N.; Gange, A.C. Endophytic actinomycetes from Azadirachta indica A. Juss.: Isolation, diversity, and anti-microbial activity. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 57, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombs, J.T.; Franco, C.M. Isolation and identification of actinobacteria from surface-sterilized wheat roots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 5603–5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessitsch, A.; Reiter, B.; Berg, G. Endophytic bacterial communities of field-grown potato plants and their plant-growth-promoting and antagonistic abilities. Can. J. Microbiol. 2004, 50, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Cui, K.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; He, Z.; Liu, C.; Tang, W.; et al. Biodiversity of culturable endophytic Actinobacteria isolated from high yield Camellia oleifera and their plant growth promotion potential. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, X. Endophytic actinomycetes from tea plants (Camellia sinensis): Isolation, abundance, antimicrobial, and plant-growth-promoting activities. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1470305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Vo, Q.A.T.; Barnett, S.J.; Ballard, R.A.; Zhu, Y.; Franco, C.M.M. Revealing the underlying mechanisms mediated by endophytic actinobacteria to enhance the rhizobia-chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) symbiosis. Plant Soil. 2022, 474, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruasuwan, W.; Thamchaipenet, A. Diversity of culturable plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes associated with sugarcane roots and their effect of growth by co-inoculation of diazotrophs and actinomycetes. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2016, 35, 1074–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baoune, H.; Ould El Hadj-Khelil, A.; Pucci, G.; Sineli, P.; Loucif, L.; Polti, M.A. Petroleum degradation by endophytic Streptomyces spp. isolated from plants grown in contaminated soil of southern Algeria. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 147, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, K.K.; Sorty, A.M.; Bitla, U.M.; Choudhary, K.; Gupta, P.; Pareek, A.; Singh, D.P.; Prabha, R.; Sahu, P.K.; Gupta, V.K.; et al. Abiotic stress responses and microbe-mediated mitigation in plants: The omics strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Dawwam, G.E.; Sehim, A.E.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, D. Drought stress triggers shifts in the root microbial community and alters functional categories in the microbial gene pool. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 744897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Medellín, C.; Edwards, J.; Liechty, Z.; Nguyen, B.; Sundaresan, V. Drought stress results in a compartment-specific restructuring of the rice root-associated microbiomes. mBio 2017, 8, e00764-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebre, P.H.; De Maayer, P.; Cowan, D.A. Xerotolerant bacteria: Surviving through a dry spell. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, T.; Styer, A.B.; Pierroz, G.; Gonçalves, A.P.; Pasricha, R.; Hazra, A.B.; Bubner, P.; Coleman-Derr, D. Drought drives spatial variation in the millet root microbiome. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, D.; DeGraaf, S.; Purdom, E.; Coleman-Derr, D. Drought and host selection influence bacterial community dynamics in the grass root microbiome. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2691–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Zhang, G.; Yu, Z.; Ding, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Effect of drought stress and developmental stages on microbial community structure and diversity in peanut rhizosphere soil. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, J.; Long, X.; Liu, Z.; Rengel, Z. Salinity altered root distribution and increased diversity of bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil of Jerusalem artichoke. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Ding, H.; Ci, D.; Dai, L.; Zhang, Z. Influence of salt stress on the rhizosphere soil bacterial community structure and growth performance of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Int. Microbiol. 2020, 23, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, S.; Chen, L.; Wang, D.; Zhao, C. The responses of a soil bacterial community under saline stress are associated with Cd availability in long-term wastewater-irrigated field soil. Chemosphere 2019, 236, 124372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msimbira, L.A.; Smith, D.L. The roles of plant growth promoting microbes in enhancing plant tolerance to acidity and alkalinity stresses. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhalnina, K.; Dias, R.; de Quadros, P.D.; Davis-Richardson, A.; Camargo, F.A.; Clark, I.M.; McGrath, S.P.; Hirsch, P.R.; Triplett, E.W. Soil pH determines microbial diversity and composition in the park grass experiment. Microb. Ecol. 2015, 69, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, X.; Guo, D.; Zhao, J.; Yan, L.; Feng, G.; Gao, Q.; Yu, H.; Zhao, L. Soil pH is the primary factor driving the distribution and function of microorganisms in farmland soils in northeastern China. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 1461–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Srinivas, V.; Sree Vidya, M.; Rathore, A. Plant growth-promoting activities of Streptomyces spp. in sorghum and rice. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.A.; Xiang, C.; Farooq, M.; Muhammad, N.; Yan, Z.; Hui, X.; Yuanyuan, K.; Bruno, A.K.; Lele, Z.; Jincai, L. Cold stress in wheat: Plant acclimation responses and management strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 676884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.J.; Guo, G.; Li, M.; Liang, X.Y.; Gu, Y.Y. Diversity of endophytic bacteria of mulberry (Morus L.) under cold conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 923162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K. Heavy metals toxicity in plants: An overview on the role of glutathione and phytochelatins in heavy metal stress tolerance of plants. S Afr. J. Bot. 2010, 76, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, W.; Yu, R.; Ye, Z. Illumina-based analysis of bulk and rhizosphere soil bacterial communities in paddy fields Under mixed heavy metal contamination. Pedosphere 2017, 27, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremion, F.; Chatzinotas, A.; Harms, H. Comparative 16S rDNA and 16S rRNA sequence analysis indicates that Actinobacteria might be a dominant part of the metabolically active bacteria in heavy metal-contaminated bulk and rhizosphere soil. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 5, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wipf, H.M.-L.; Bùi, T.-N.; Coleman-Derr, D. Distinguishing between the impacts of heat and drought stress on the root microbiome of Sorghum bicolor. Phytobiomes J. 2021, 5, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangseekaew, P.; Barros-Rodriguez, A.; Pathom-Aree, W.; Manzanera, M. Plant beneficial deep-sea Actinobacterium, Dermacoccus abyssi MT1.1(T) promote growth of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) under salinity stress. Biology 2022, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdarian, M.; Askari, H.; Shariati, J.V.; Nematzadeh, G. Transcriptional responses of wheat roots inoculated with Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus to salt stress. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, P.W.; Drew, M.C. Ethylene and plant responses to stress. Physiol. Plant 1997, 100, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattyn, J.; Vaughan-Hirsch, J.; Van de Poel, B. The regulation of ethylene biosynthesis: A complex multilevel control circuitry. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick, B.R. Stress control and ACC deaminase. In Principles of Plant-Microbe Interactions: Microbes for Sustainable Agriculture; Lugtenberg, B., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- Siddikee, M.A.; Chauhan, P.S.; Anandham, R.; Han, G.H.; Sa, T. Isolation, characterization, and use for plant growth promotion under salt stress, of ACC deaminase-Producing halotolerant bacteria derived from coastal soil. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 20, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palaniyandi, S.A.; Damodharan, K.; Yang, S.H.; Suh, J.W. Streptomyces sp. strain PGPA39 alleviates salt stress and promotes growth of ‘Micro Tom’ tomato plants. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Bai, J.L.; Yang, H.T.; Zhang, W.D.; Xiong, Y.W.; Ding, P.; Qin, S. Phylogenetic diversity and investigation of plant growth-promoting traits of actinobacteria in coastal salt marsh plant rhizospheres from Jiangsu, China. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 41, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoolong, S.; Kruasuwan, W.; Thanh Phạm, H.T.; Jaemsaeng, R.; Jantasuriyarat, C.; Thamchaipenet, A. Modulation of salt tolerance in Thai jasmine rice (Oryza sativa L. cv. KDML105) by Streptomyces venezuelae ATCC 10712 expressing ACC deaminase. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuneme, C.F.; Babalola, O.O.; Kutu, F.R.; Ojuederie, O.B. Characterization of actinomycetes isolates for plant growth promoting traits and their effects on drought tolerance in maize. J. Plant Interact. 2020, 15, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, Q.; Jing, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, Y.; Xue, Q.; Lai, H. Application of Streptomyces pactum Act12 enhances drought resistance in wheat. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Gao, Y.; Zi, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Xiong, X.; Yao, Q.; Qin, Z.; Chen, N.; Guo, L.; et al. The osmolyte-producing endophyte Streptomyces albidoflavus OsiLf-2 induces drought and salt tolerance in rice via a multi-level mechanism. Crop. J. 2022, 10, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silambarasan, S.; Logeswari, P.; Vangnai, A.S.; Kamaraj, B.; Cornejo, P. Plant growth-promoting actinobacterial inoculant assisted phytoremediation increases cadmium uptake in Sorghum bicolor under drought and heat stresses. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 307, 119489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathom-Aree, W.; Matako, A.; Rangseekaew, P.; Seesuriyachan, P.; Srinuanpan, S. Performance of Actinobacteria isolated from rhizosphere soils on plant growth promotion under cadmium toxicity. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2021, 23, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, P.; Pandey, A.; Sa, T. Chromate reducing and plant growth promoting activities of psychrotrophic Rhodococcus erythropolis MtCC 7,905. J. Basic Microbiol. 2007, 47, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuter, J.A.; Spacek, D.V.; Snyder, M.P. High-throughput sequencing technologies. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Feng, W.-W.; Wang, T.-T.; Ding, P.; Xing, K.; Jiang, J.-H. Plant growth-promoting effect and genomic analysis of the beneficial endophyte Streptomyces sp. KLBMP 5084 isolated from halophyte Limonium sinense. Plant Soil. 2017, 416, 117+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Solanki, M.K.; Yu, Z.X.; Yang, L.T.; An, Q.L.; Dong, D.F.; Li, Y.R. Draft genome analysis offers insights into the mechanism by which Streptomyces chartreusis WZS021 increases drought tolerance in sugarcane. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruasuwan, W.; Salih, T.S.; Brozio, S.; Hoskisson, P.A.; Thamchaipenet, A. Draft genome sequence of plant growth-promoting endophytic Streptomyces sp. GKU 895 isolated from the roots of sugarcane. Genome. Announc. 2017, 5, e00358-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Han, Y.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. A salt-tolerant Streptomyces paradoxus D2-8 from rhizosphere soil of Phragmites communis augments soybean tolerance to soda saline-Alkali stress. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2022, 71, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.Y.; Narsing Rao, M.P.; Wang, H.F.; Fang, B.Z.; Liu, Y.H.; Li, L.; Xiao, M.; Li, W.J. Transcriptomic analysis of two endophytes involved in enhancing salt stress ability of Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 686, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.A.; Achnine, L.; Kota, P.; Liu, C.J.; Reddy, M.S.; Wang, L. The phenylpropanoid pathway and plant defence-a genomics perspective. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2002, 3, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chen, L.-J.; Pan, S.-Y.; Li, X.-W.; Xu, M.-J.; Zhang, C.-M.; Xing, K.; Qin, S. Antifungal potential evaluation and alleviation of salt stress in tomato seedlings by a halotolerant plant growth-promoting actinomycete Streptomyces sp. KLBMP5084. Rhizosphere 2020, 16, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, I.; Mendes, V.M.; Marques, I.; Duro, N.; da Costa, M.; Ramalho, J.C.; Pawlowski, K.; Manadas, B.; Pinto Ricardo, C.P.; Ribeiro-Barros, A.I. Comparative proteomic analysis of nodulated and non-nodulated Casuarina glauca Sieb. ex Spreng. grown under salinity conditions using sequential window acquisition of all theoretical mass spectra (SWATH-MS). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 21, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Naylor, D.; Dong, Z.; Simmons, T.; Pierroz, G.; Hixson, K.K.; Kim, Y.M.; Zink, E.M.; Engbrecht, K.M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Drought delays development of the sorghum root microbiome and enriches for monoderm bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018, 115, E4284–E4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, B.J.; Labbé, J.L.; Jones, P.; Abraham, P.E.; Hodge, I.; Climer, S.; Jawdy, S.; Gunter, L.; Tuskan, G.A.; Yang, X.; et al. Phytobiome and transcriptional adaptation of Populus deltoides to acute progressive drought and cyclic drought. Phytobiomes J. 2018, 2, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Dong, Z.; Chiniquy, D.; Pierroz, G.; Deng, S.; Gao, C.; Diamond, S.; Simmons, T.; Wipf, H.M.L.; Caddell, D.; et al. Genome-resolved metagenomics reveals role of iron metabolism in drought-induced rhizosphere microbiome dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duro, N.; Batista-Santos, P.; da Costa, M.; Maia, R.; Castro, I.V.; Ramos, M.; Ramalho, J.C.; Pawlowski, K.; Máguas, C.; Ribeiro-Barros, A. The impact of salinity on the symbiosis between Casuarina glauca Sieb. ex Spreng. and N2-fixing Frankia bacteria based on the analysis of nitrogen and carbon metabolism. Plant Soil. 2016, 398, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stress | Actinobacteria | Genes | Host | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salinity | Streptomyces sp. KLBMP 5084 | ACC deaminase, cold shock proteins, glycine betaine transport ATP binding protein, heat shock proteins, heavy metal resistance, hydrogen cyanide synthase, chitinase, β-glucosidase, lipase, cellulase, protease, and amylase, IAA biosynthesis, K+ transporter, Na+/H+ antiporters, oxidative stress response: SOD, POD, and CAT, phenazine biosynthesis, phosphate solubilization, pyridoxal biosynthesis lyase, succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase, trehalose synthase | Limonium sinense | [113] |

| Streptomyces sp. GKU 895 | ACC deaminase, ectoine biosynthesis, family 18 and 19 chitinases, IAA biosynthesis, mineral phosphate solubilization: isocitrate dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, and purple acid phosphatase, nitrogen metabolism, salicylate hydroxylase | Sugarcane variety KK3 | [115] | |

| Streptomyces paradoxus D2-8 | ACC deaminase, aldehyde dehydrogenase (NAD), ammonia assimilation, ectoine, IAA biosynthesis, choline and glycine betaine uptake | Soybean | [116] | |

| Dermacoccus abyssi MT1.1 | Ammonium assimilation, betaine biosynthesis, catalase, choline and betaine uptake, ectoine biosynthesis, glutathionylspermidine synthase, glycerol uptake facilitator protein, IAA biosynthesis, iron acquisition and metabolism. nitrogen metabolism, osmotic stress response, oxidative stress response, phosphate metabolizing enzymes, phosphate solubilization, poly-phosphorus hydrolyzing enzymes, potassium homeostasis, proline synthesis, 4-hydroxyproline uptake and utilization, total soluble sugar production, trehalose biosynthesis, tryptophan synthesis, uptake and transport of inorganic phosphate | Solanum lycopersicum | [97] | |

| Drought | Streptomyces chartreusis WZS021 | ACC deaminase, choline dehydrogenase, glutamate dehydrogenase, cellulase, chitinase, xylanase, glucoamylase, α-amylase, malto-oligosyltrehalose trehalohydrolase, and lipase, IAA biosynthesis, ion transporter, Na+, Ca2+, and K+ transporters, oxidative stress response: SOD, phosphate transmembrane transporters, phosphate transport, proline dehydrogenase, succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | Sugarcane varieties ROC22 and B8 | [114] |

| Plant | Actinobacteria | Pathways | Upregulation | Downregulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triticum aestivum L. | Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus | Secondary metabolites, cysteine/methionine, diarylheptanoid, flavonoid/terpenoid/stillbenoid, glycerolipid, iron (Fe) acquisition, Na+ homeostasis, phenylpropanoid, photosynthesis, porphyrin/chlorophyll | Ascorbate/glutathione peroxidases, ATPase, cytochrome P450, hemethiolate enzyme, ion transporter, nicotinamide synthase, phosphatase, ABC transporter, sugar transporter, oligopeptide, amino acid/polyamine/folate-biopterin transporter | Cytochrome P450, metallothionein, RipA-like protein | [98] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Arthrobacter endophyticus SYSU 333322 Nocardiopsis alba SYSU 333140 | Carotenoid, glycerolipid, secondary metabolites, phenylalanine, phenylpropanoid, nitrogen metabolism | Auxin binding, homeostasis, efflux, transport, chlorophyll a reductase, cytokinin dehydrogenase, DUF1399 domain-containing proteins, legume lectin family RING-finger E3 ligase, peptide-methionine (R)-S-oxide reductase, potassium ion uptake, hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein | Phosphate starvation | [117] |

| Solanum lycopersicum cv. Jingpeng No.1 | Streptomyces sp. KLBMP5084 | Betalain synthesis, isoquinoline alkaloid, photosynthesis-antenna proteins, zeatin biosynthesis, protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum | Auxin-responsive IAA29, BOI-related E3, ubiquitin-protein ligase 3, calcineurin-like phosphoesterase, chitinase, chlorophyll a-b binding protein, 4,5-DOPA dioxygenase extradiol, elongation factor protein, glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase, glutamine synthetase, linoleate 13S-lipoxygenase 2-1, peroxidase, glutathione S-transferase, receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase, salicylic acid carboxyl methyltransferase, zeatin O-xylosyl transferase | Cytokinin dehydrogenase, ethylene-responsive transcription factor | [119] |

| Casuarina glauca | Frankia | Amino acids, carbohydrates, metabolic pathways, secondary metabolites, cysteine/methionine, energy metabolism, lipid metabolism, seleno compound, protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, plant-pathogen interaction | ROS defence, monodehydro ascorbate reductase, temperature-induced lipocalin, thioredoxin-dependent peroxidase, Photosynthesis, quinone-oxireductase, thylakoid luminal 19 kDa, stress-responsive proteins, lipocalin, universal-stress protein, thaumatin | [120] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Narsing Rao, M.P.; Lohmaneeratana, K.; Bunyoo, C.; Thamchaipenet, A. Actinobacteria–Plant Interactions in Alleviating Abiotic Stress. Plants 2022, 11, 2976. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11212976

Narsing Rao MP, Lohmaneeratana K, Bunyoo C, Thamchaipenet A. Actinobacteria–Plant Interactions in Alleviating Abiotic Stress. Plants. 2022; 11(21):2976. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11212976

Chicago/Turabian StyleNarsing Rao, Manik Prabhu, Karan Lohmaneeratana, Chakrit Bunyoo, and Arinthip Thamchaipenet. 2022. "Actinobacteria–Plant Interactions in Alleviating Abiotic Stress" Plants 11, no. 21: 2976. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11212976

APA StyleNarsing Rao, M. P., Lohmaneeratana, K., Bunyoo, C., & Thamchaipenet, A. (2022). Actinobacteria–Plant Interactions in Alleviating Abiotic Stress. Plants, 11(21), 2976. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11212976