Snatching Sundews—Analysis of Tentacle Movement in Two Species of Drosera in Terms of Response Rate, Response Time, and Speed of Movement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.2. Tentacle Type Specific Responses

2.3. Species-Specific Division of Labour

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

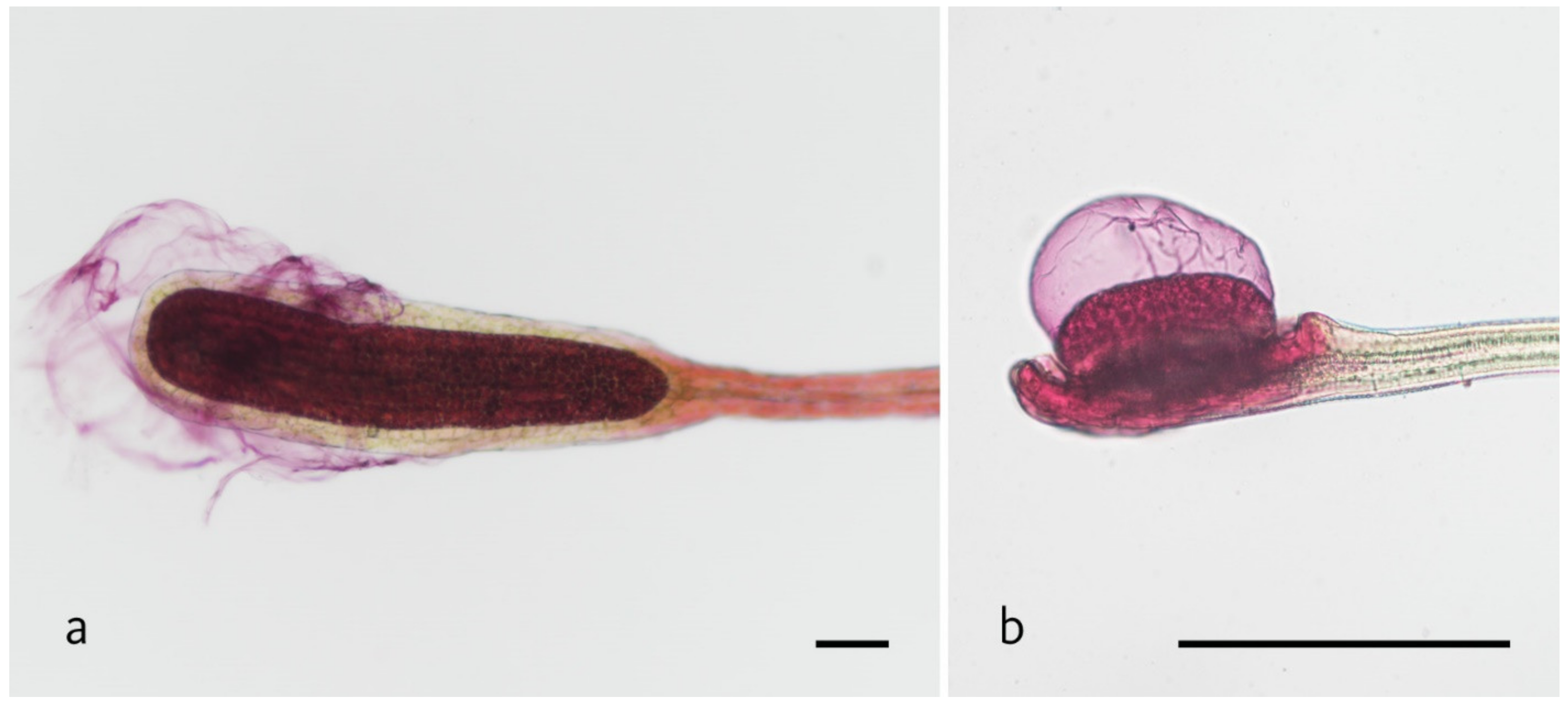

4.2. Mucilage Staining

4.3. Stimulation Experiment

- Response rate (RR): For each species, tentacle type, and stimulus, the number of tentacles responding within 5–7 min and non-responding tentacles were counted.

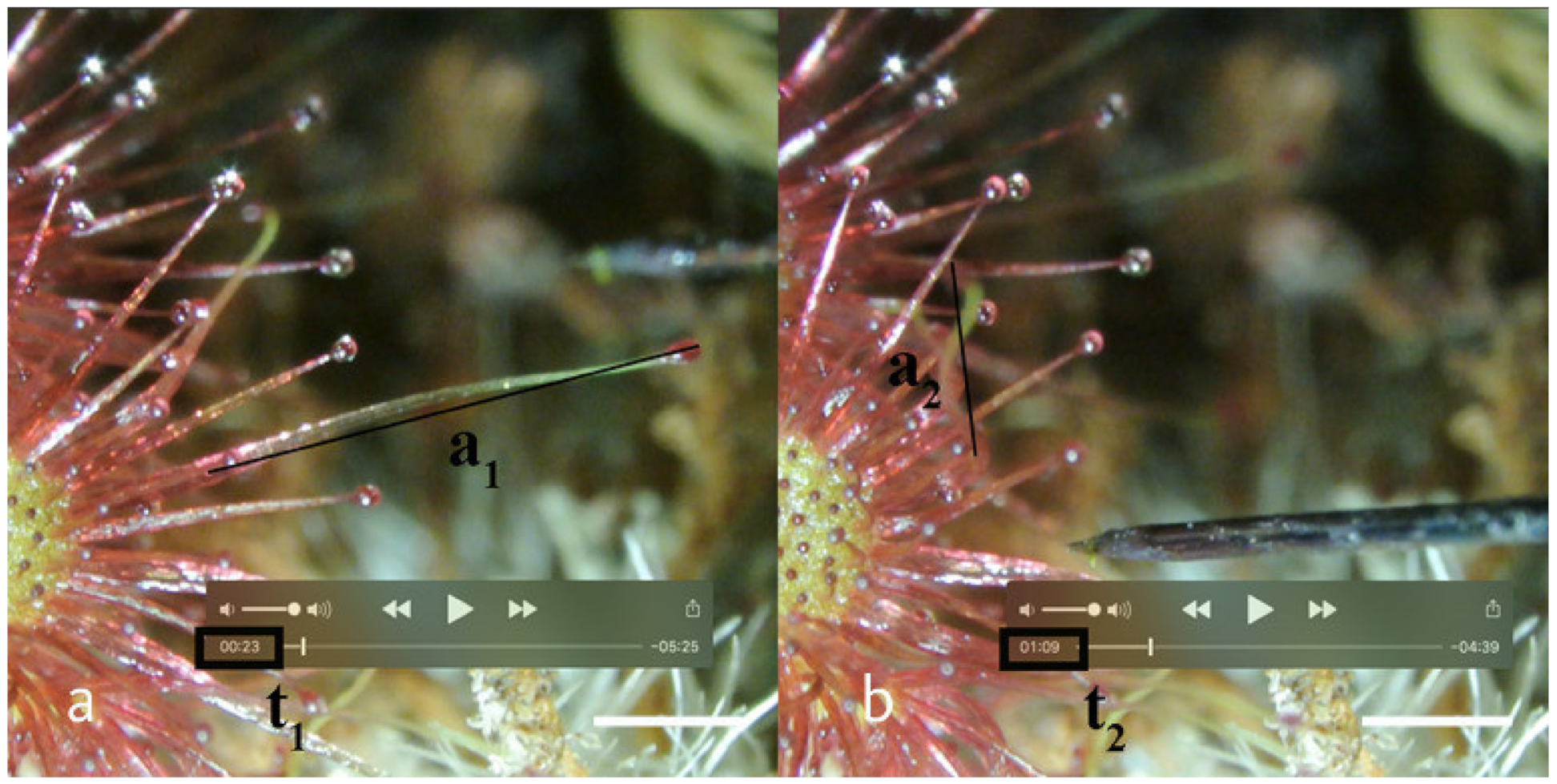

- Response time (RT) was defined as the times [s] passing between the first contact with the stimulus (t0) and the start of the motion (t1) (RT = t1 − t0). In case of electrical stimulation, multiple stimuli were applied; t0 was the time of the first triggering of the piezo igniter.

- Angular velocity (AV) was calculated by applying the trigonometric model following the description in Section 4.4.

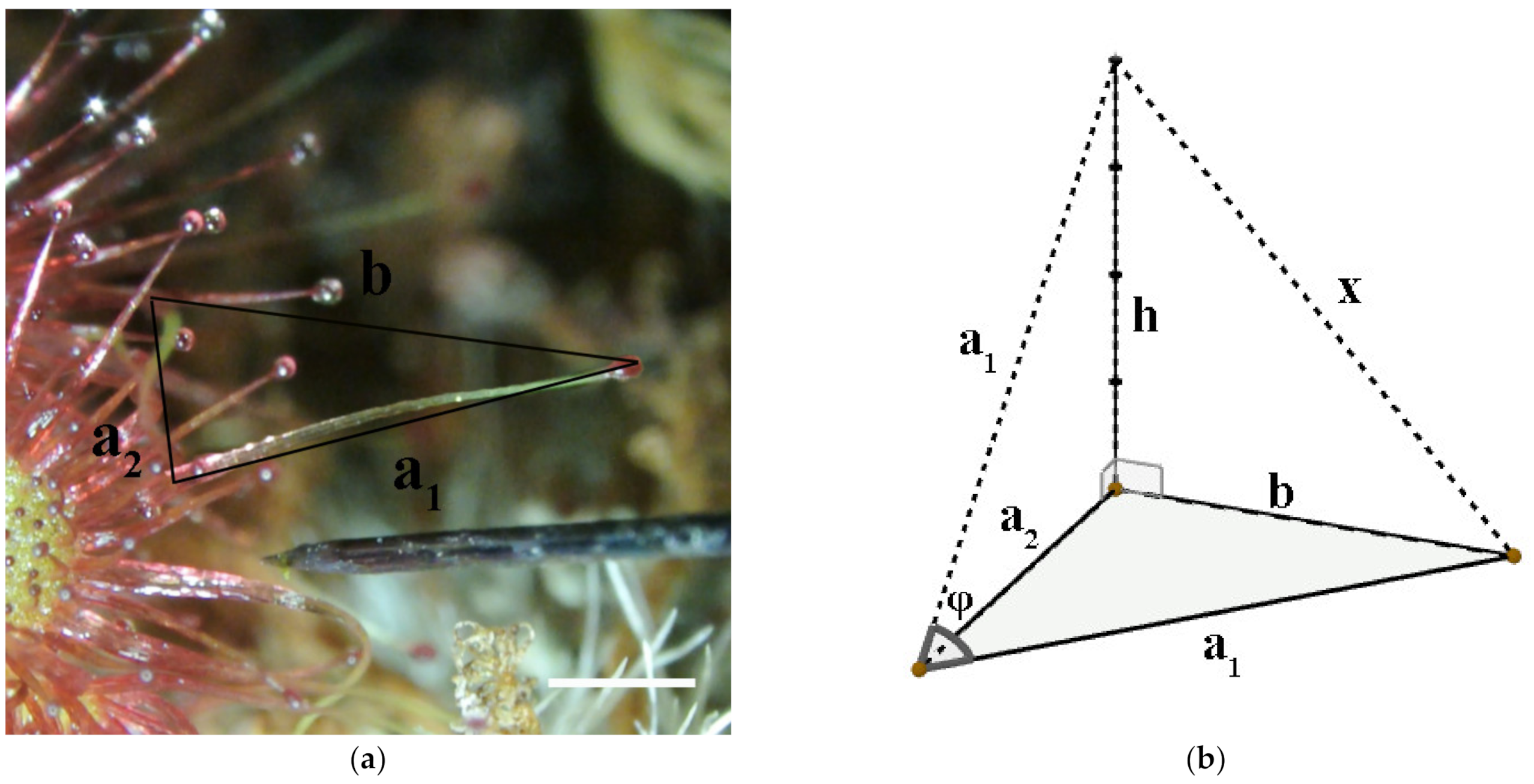

4.4. The Trigonometric Model for Approximation of Angular Velocity (AV)

5. Conclusions

- The type of stimulus plays a significant role in response rates and angular velocities. However, it does not influence the response time. Chemical and electrical stimulation produce virtually identical responses. In comparison, mechanically stimulated tentacles react less frequently, with the same response time and a higher angular velocity.

- Movement sequence parameters are strongly dependent on species. In D. allantostigma tentacles react more frequently, with a shorter response time and higher angular velocity compared to D. rotundifolia. Snap-tentacles respond less frequently but with shorter response times and higher angular velocities compared to peripheral tentacles.

- Tentacle responses are highly species-specific, with D. allantostigma exhibiting a specialization to mechanical stimulus, displayed by the highest angular velocities observed. This is especially pronounced in the movement sequence parameters of snap-tentacles in comparison to peripheral tentacles. D. rotundifolia is specialized in chemical triggers, and this type of stimulus leads to the highest response rates and angular velocities within this species.

- Finally, this study shows that behavior of snap-tentacles and peripheral tentacles varies between the species that were observed. D. allantostigma has snap-tentacles specialized in mechanic prey capture and retention, whereas snap-tentacles in D. rotundifolia behave similarly to peripheral tentacles, with adhesion and mechanical prey retention.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barthlott, W.; Porembski, S.; Seine, R.; Theisen, I. The Curious World of Carnivorous Plants: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Biology and Cultivation; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2007; 224p. [Google Scholar]

- Slack, A. Carnivorous Plants; MIT Press: Yeovil, UK, 2000; 240p. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, F.E. The Carnivorous Plants; Chronica Botanica Company: Waltham, MA, USA, 1942; 352p. [Google Scholar]

- Braem, G. Fleischfressende Pflanzen: Gattung und Arten im Porträt-Freiland-und Zimmerkultur-Vermehrung, 2nd ed.; Augustus: München, Germany, 2002; 134p. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, S. Glistening Carnivores: The Sticky-Leaved Insect-Eating Plants; Redfern Natual History Productions Limited: Poole, UK, 2008; 360p. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, C. Insectivorous Plants; John Murray: London, UK, 1875; 462p. [Google Scholar]

- Krausko, M.; Perutka, Z.; Šebela, M.; Šamajová, O.; Šamaj, J.; Novák, O.; Pavlovič, A. The role of electrical and Jasmonate signalling in the recognition of captured prey in the carnivorous sundew plant Drosera capensis. New Phytol. 2017, 213, 1818–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mithöfer, A.; Reichelt, M.; Nakamura, Y. Wound and insect-induced Jasmonate accumulation in carnivorous Drosera capensis: Two sides of the same coin. Plant Biol. 2014, 16, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Reichelt, M.; Mayer, V.E.; Mithöfer, A. Jasmonates trigger prey-induced formation of ‘Outer Stomach’ in carnivorous sundew plants. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20130228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Williams, S.E.; Pickard, B.G. Properties of action potentials in Drosera tentacles. Planta 1972, 103, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, D.K.; Yanthan, S.; Konhar, R.; Debnath, M.; Kumaria, S.; Tandon, P. Phylogeny and biogeography of the carnivorous plant family Droseraceae with representative Drosera species from Northeast India. F1000Research 2017, 6, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellison, A.M.; Adamec, L. Carnivorous Plants: Physiology, Ecology, and Evolution; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; 510p. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovič, A.; Krausko, M.; Adamec, L. A carnivorous sundew plant prefers protein over chitin as a source of Nitrogen from its traps. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 104, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtscheidl, I.; Lancelle, S.; Weidinger, M.; Adlassnig, W.; Koller-Peroutka, M.; Bauer, S.; Krammer, S.; Hepler, P.K. Gland cell responses to feeding in Drosera capensis, a carnivorous plant. Protoplasma 2021, 258, 1291–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rost, K.; Schauer, R. Physical and chemical properties of the mucin secreted by Drosera capensis. Phytochemistry 1977, 16, 1365–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butts, C.T.; Bierma, J.C.; Martin, R.W. Novel proteases from the genome of the carnivorous plant Drosera capensis: Structural prediction and comparative analysis. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2016, 84, 1517–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qiu, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, X.; Wu, H.; Ma, X.; Hu, J.; Qi, H.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Bao, G.; et al. A biomimetic Drosera capensis with adaptive decision-predation behavior based on multifunctional sensing and fast actuating capability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 32, 2110296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppinga, S.; Hartmeyer, S.; Masselter, T.; Hartmeyer, I.; Speck, T. Trap diversity and evolution in the family Droseraceae. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harmeyer, S.R.H.; Hartmeyer, I. Several pygmy sundew species possess catapult-flypaper traps with repetitive function, indicating a possible evolutionary change into aquatic snap traps similar to Aldrovanda. Carniv. Plant Newsl. 2015, 44, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowrie, A.; Nunn, R.; Robinson, A.; Bourke, G.; McPherson, S.; Fleischmann, A. Drosera of the World Volume 1 Oceania; Robinson, A., Ed.; Redfern Natural History Productions Limited: Poole, UK, 2017; Volume 1, 528p. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner, C.A. Beiträge Zur Kenntnis der Anatomie, Entwicklungsgeschichte und Biologie der Laubblätter und Drüsen einiger Insektivoren. Flora 1904, 93, 335–434. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmeyer, S.; Harmeyer, I. Snap-tentacles and runway lights: Summary of comparative examination of Drosera tentacles. Carniv. Plant Newsl. 2010, 39, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppinga, S.; Masselter, T.; Speck, T. Faster than their prey: New insights into the rapid movements of active carnivorous plants traps. BioEssays 2013, 35, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedrich, R.; Fukushima, K. On the origin of carnivory: Molecular physiology and evolution of plants on an animal diet. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021, 72, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlovič, A.; Mithöfer, A. Jasmonate signalling in carnivorous plants: Copycat of plant defence mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 3379–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libiaková, M.; Floková, K.; Novák, O.; Slováková, L.; Pavlovič, A. Abundance of Cysteine Endopeptidase Dionain in digestive fluid of Venus Flytrap (Dionaea muscipula Ellis) is regulated by different stimuli from prey through Jasmonates. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e104424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Böhm, J.; Scherzer, S.; Krol, E.; Kreuzer, I.; Von Meyer, K.; Lorey, C.; Mueller, T.D.; Shabala, L.; Monte, I.; Solano, R.; et al. The Venus Flytrap Dionaea Muscipula counts prey-induced action potentials to induce sodium uptake. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivadavia, F.; Kondo, K.; Kato, M.; Hasebe, M. Phylogeny of the Sundews, Drosera (Droseraceae), based on chloroplast RbcL and nuclear 18S ribosomal DNA sequences. Am. J. Bot. 2003, 90, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.E.; Spanswick, R.M. Propagation of the neuroid action potential of the carnivorous plant Drosera. J. Comp. Physiol. 1976, 108, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppinga, S.; Hartmeyer, S.; Seidel, R.; Masselter, T.; Hartmeyer, I.; Speck, T. Catapulting tentacles in a sticky carnivorous plant. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skotheim, J.M.; Mahadevan, L. Dynamics of poroelastic filaments. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2004, 460, 1995–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, L. Morphologische und Physiologische Analyse der Unterschiedlichen Tentakeltypen von Drosera. Bachelor's Thesis, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sera San Nature|Sera. Available online: https://www.sera.de/en/product/freshwater-aquarium/sera-san-nature/ (accessed on 8 January 2022).

| Stimulus Type | Tentacle Type | Species | RR | RT [s] | AV [°/s] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | LL | UL | M | Q1 | Q3 | M | Q1 | Q3 | |||

| Mechanical Stimulation | Snap- tentacles | D. allantostigma | 31.2% | 20.9% | 41.5% | 17.5 | 10.0 | 36.2 | 7.38 | 1.0 | 15.8 |

| D. rotundifolia | 15.0% | 8.6% | 21.4% | 38.0 | 16.0 | 65.0 | 0.65 | 0.3 | 1.2 | ||

| Peripheral tentacles | D. allantostigma | 56.8% | 45.5% | 68.1% | 15.0 | 10.0 | 33.0 | 4.08 | 1.9 | 7.3 | |

| D. rotundifolia | 19.7% | 14.9% | 24.5% | 26.0 | 18.0 | 41.5 | 0.98 | 0.6 | 1.2 | ||

| Chemical Stimulation | Snap- tentacles | D. allantostigma | 49.1% | 39.9% | 58.3% | 35.5 | 26.3 | 57.5 | 3.41 | 1.1 | 5.1 |

| D. rotundifolia | 44.0% | 32.8% | 55.2% | 19.0 | 10.0 | 48.0 | 1.24 | 0.4 | 2.3 | ||

| Peripheral tentacles | D. allantostigma | 71.2% | 60.8% | 81.6% | 28.0 | 17.0 | 58.3 | 1.25 | 0.5 | 2.9 | |

| D. rotundifolia | 78.0% | 71.7% | 84.3% | 25.0 | 16.5 | 35.5 | 1.11 | 0.7 | 1.8 | ||

| Electrical Stimulation | Snap- tentacles | D. allantostigma | 71.4% | 54.7% | 88.1% | 31.5 | 15.8 | 40.5 | 3.52 | 1.8 | 5.3 |

| D. rotundifolia | 54.5% | 39.8% | 69.2% | 51.0 | 17.8 | 75.8 | 0.84 | 0.4 | 1.4 | ||

| Peripheral tentacles | D. allantostigma | 70.9% | 63.0% | 78.8% | 9.0 | 6.0 | 36.0 | 3.85 | 2.1 | 6.1 | |

| D. rotundifolia | 62.8% | 57.2% | 68.4% | 39.0 | 17.0 | 73.0 | 0.76 | 0.5 | 1.4 | ||

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | n | R² | Prob > F | Species | Tentacle Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Values | Coefficient | p-Values | Coefficient | |||||

| RR | Electrical Stimulation | 481 | 0.01 | 0.095 | 0.042 | 1.54 | 0.419 | 0.81 |

| Chemical Stimulation | 430 | 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.806 | 0.95 | <0.001 | 0.29 | |

| Mechanical Stimulation | 530 | 0.07 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 4.06 | 0.004 | 0.51 | |

| RT | Electrical Stimulation | 310 | 0.11 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −35.29 | 0.078 | 14.03 |

| Chemical Stimulation | 266 | 0.04 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 24.77 | 0.852 | 1.53 | |

| Mechanical Stimulation | 135 | 0.05 | 0.034 | 0.012 | −23.69 | 0.358 | 9.22 | |

| AV | Electrical Stimulation | 311 | 0.27 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 3.16 | 0.998 | 0.00 |

| Chemical Stimulation | 272 | 0.12 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.43 | 0.026 | 0.73 | |

| Mechanical Stimulation | 134 | 0.19 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 7.53 | 0.014 | 4.45 | |

| Dependent Variable | n | R² | Prob > F | Species | Tentacle Type | Stimulus Chemical | Stimulus Mechanical | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Values | corr. coef | p-Values | corr. coef | p-Values | corr. coef | p-Values | corr. coef | ||||

| RR | 1441 | 0.13 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.73 | <0.001 | 0.45 | 0.451 | 1.12 | <0.001 | 0.21 |

| RT | 711 | 0.02 | 0.012 | 0.007 | −11.65 | 0.018 | 11.89 | 0.314 | −4.72 | 0.125 | −8.84 |

| AV | 717 | 0.15 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 3.35 | 0.008 | 1.16 | 0.087 | −0.69 | <0.001 | 1.85 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ivesic, C.; Adlassnig, W.; Koller-Peroutka, M.; Kress, L.; Lang, I. Snatching Sundews—Analysis of Tentacle Movement in Two Species of Drosera in Terms of Response Rate, Response Time, and Speed of Movement. Plants 2022, 11, 3212. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11233212

Ivesic C, Adlassnig W, Koller-Peroutka M, Kress L, Lang I. Snatching Sundews—Analysis of Tentacle Movement in Two Species of Drosera in Terms of Response Rate, Response Time, and Speed of Movement. Plants. 2022; 11(23):3212. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11233212

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvesic, Caroline, Wolfram Adlassnig, Marianne Koller-Peroutka, Linda Kress, and Ingeborg Lang. 2022. "Snatching Sundews—Analysis of Tentacle Movement in Two Species of Drosera in Terms of Response Rate, Response Time, and Speed of Movement" Plants 11, no. 23: 3212. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11233212

APA StyleIvesic, C., Adlassnig, W., Koller-Peroutka, M., Kress, L., & Lang, I. (2022). Snatching Sundews—Analysis of Tentacle Movement in Two Species of Drosera in Terms of Response Rate, Response Time, and Speed of Movement. Plants, 11(23), 3212. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11233212