A Systematic Review on the Therapeutic Effects of Ayahuasca

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

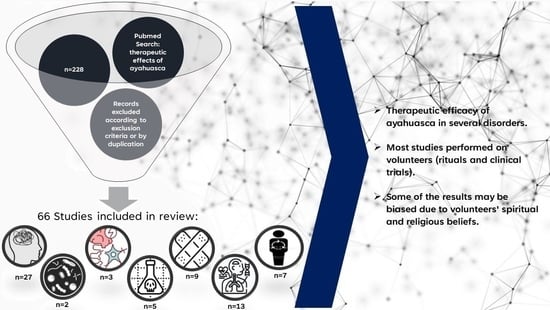

2.1. Study Selection

2.2. Effects Associated with Mental Health and Psychological Well-Being

2.3. Antimicrobial Properties

2.4. Anti-Inflammatory Properties

2.5. Other Therapeutic Effects

2.6. Effects on Metabolism

2.7. Physiological Effects

2.8. Toxicological Effects and Toxicity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Acquisition

3.2. Search Strategy

3.3. Eligibility Criteria

3.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonçalves, J.; Luís, Â.; Gallardo, E.; Duarte, A.P. Evaluation of the In vitro Wound-Healing Potential of Ayahuasca. Molecules 2022, 27, 5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camejo-Rodrigues, J.; Ascensão, L.; Bonet, M.À.; Vallès, J. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal and aromatic plants in the Natural Park of “Serra de São Mamede” (Portugal). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 89, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, E.S.; Luís, Â.; Gonçalves, J.; Rosado, T.; Pereira, L.; Gallardo, E.; Duarte, A.P. Julbernardia paniculata and Pterocarpus angolensis: From Ethnobotanical Surveys to Phytochemical Characterization and Bioactivities Evaluation. Molecules 2020, 25, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Luís, Â.; Gallardo, E.; Duarte, A.P. Psychoactive Substances of Natural Origin: Toxicological Aspects, Therapeutic Properties and Analysis in Biological Samples. Molecules 2021, 26, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Faro, A.F.; Di Trana, A.; La Maida, N.; Tagliabracci, A.; Giorgetti, R.; Busardò, F.P. Biomedical analysis of New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) of natural origin. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 179, 112945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, A.Y.; Gonçalves, J.; Duarte, A.P.; Barroso, M.; Cristóvão, A.C.; Gallardo, E. Toxicological Aspects and Determination of the Main Components of Ayahuasca: A Critical Review. Medicines 2019, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, J.; Luís, Â.; Gradillas, A.; García, A.; Restolho, J.; Fernández, N.; Domingues, F.; Gallardo, E.; Duarte, A.P. Ayahuasca Beverages: Phytochemical Analysis and Biological Properties. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaujac, A.; Dempster, N.; Navickiene, S.; Brandt, S.D.; De Andrade, J.B. Determination of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in beverages consumed in religious practices by headspace solid-phase microextraction followed by gas chromatography ion trap mass spectrometry. Talanta 2013, 106, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Clavé, E.; Soler, J.; Elices, M.; Pascual, J.C.; Álvarez, E.; de la Fuente Revenga, M.; Friedlander, P.; Feilding, A.; Riba, J. Ayahuasca: Pharmacology, neuroscience and therapeutic potential. Brain Res. Bull. 2016, 126, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.G.; Bouso, J.C.; Hallak, J.E.C. Ayahuasca, dimethyltryptamine, and psychosis: A systematic review of human studies. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 7, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Castilho, M.; Rosado, T.; Luís, Â.; Restolho, J.; Fernández, N.; Gallardo, E.; Duarte, A.P. In vitro Study of the Bioavailability and Bioaccessibility of the Main Compounds Present in Ayahuasca Beverages. Molecules 2021, 26, 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, R.G.; Hallak, J.E.C. Ayahuasca, an ancient substance with traditional and contemporary use in neuropsychiatry and neuroscience. Epilepsy Behav. 2021, 121, 106300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabec de Mori, B. The Power of Social Attribution: Perspectives on the Healing Efficacy of Ayahuasca. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 748131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, T.S.; de Oliveira, R.; da Silva, M.L.; Von Zuben, M.V.; Grisolia, C.K.; Domingues, I.; Caldas, E.D.; Pic-Taylor, A. Exposure to ayahuasca induces developmental and behavioral alterations on early life stages of zebrafish. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 293, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gable, R.S. Risk assessment of ritual use of oral dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and harmala alkaloids. Addiction 2007, 102, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sklerov, J.; Levine, B.; Moore, K.A.; King, T.; Fowler, D. A fatal intoxication following the ingestion of 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine in an ayahuasca preparation. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2005, 29, 838–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frison, G.; Favretto, D.; Zancanaro, F.; Fazzin, G.; Ferrara, S.D. A case of β-carboline alkaloid intoxication following ingestion of Peganum harmala seed extract. Forensic Sci. Int. 2008, 179, e37–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riba, J.; Valle, M.; Urbano, G.; Yritia, M.; Morte, A.; Barbanoj, M.J. Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion, and Pharmacokinetics. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 306, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.G.; Balthazar, F.M.; Bouso, J.C.; Hallak, J.E.C. The current state of research on ayahuasca: A systematic review of human studies assessing psychiatric symptoms, neuropsychological functioning, and neuroimaging. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1230–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riba, J.; Romero, S.; Grasa, E.; Mena, E.; Carrió, I.; Barbanoj, M.J. Increased frontal and paralimbic activation following ayahuasca, the pan-amazonian inebriant. Psychopharmacology 2006, 186, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, Ĺ.; Dos Santos, R.G.; Bouso, J.C.; Hallak, J.E. Risk assessment of ayahuasca use in a religious context: Self-reported risk factors and adverse effects. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2021, 43, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, Z.; Bosch, O.G.; Singh, D.; Narayanan, S.; Kasinather, B.V.; Seifritz, E.; Kornhuber, J.; Quednow, B.B.; Müller, C.P. Novel Psychoactive Substances-Recent Progress on Neuropharmacological Mechanisms of Action for Selected Drugs. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffell, S.G.D.; Netzband, N.; Tsang, W.; Davies, M.; Butler, M.; Rucker, J.J.H.; Tófoli, L.F.; Dempster, E.L.; Young, A.H.; Morgan, C.J.A. Ceremonial Ayahuasca in Amazonian Retreats-Mental Health and Epigenetic Outcomes From a Six-Month Naturalistic Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, F.S.; Silva, E.A.S.; De Sousa, G.M.; Maia-De-oliveira, J.P.; De Soares-Rachetti, V.P.; De Araujo, D.B.; Sousa, M.B.C.; Lobão-Soares, B.; Hallak, J.; Galvão-Coelho, N.L. Acute effects of ayahuasca in a juvenile non-human primate model of depression. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2019, 41, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, P.C.R.; Cazorla, I.M.; Giglio, J.S.; Strassman, R.S. A six-month prospective evaluation of personality traits, psychiatric symptoms and quality of life in ayahuasca-naïve subjects. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2009, 41, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuypers, K.P.C.; Riba, J.; de la Fuente Revenga, M.; Barker, S.; Theunissen, E.L.; Ramaekers, J.G. Ayahuasca enhances creative divergent thinking while decreasing conventional convergent thinking. Psychopharmacology 2016, 233, 3395–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulart da Silva, M.; Daros, G.C.; Santos, F.P.; Yonamine, M.; de Bitencourt, R.M. Antidepressant and anxiolytic-like effects of ayahuasca in rats subjected to LPS-induced neuroinflammation. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 434, 114007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa-Netto, N.F.; Masukawa, M.Y.; Nishide, F.; Galfano, G.S.; Tamura, F.; Shimizo, M.K.; Marcato, M.P.; Santos-Junior, J.G.; Linardi, A. An ontogenic study of the behavioral effects of chronic intermittent exposure to ayahuasca in mice. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. = Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Med. e Biol. 2017, 50, 1414–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, R.F.; De Lima Osório, F.; Santos, R.G.D.; Macedo, L.R.H.; Maia-De-Oliveira, J.P.; Wichert-Ana, L.; De Araujo, D.B.; Riba, J.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Hallak, J.E.C. Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression a SPECT study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 36, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.G.; Landeira-Fernandez, J.; Strassman, R.J.; Motta, V.; Cruz, A.P.M. Effects of ayahuasca on psychometric measures of anxiety, panic-like and hopelessness in Santo Daime members. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 112, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, M.N.; Altman, B.R.; Earleywine, M. Ayahuasca’s Antidepressant Effects Covary with Behavioral Activation as Well as Mindfulness. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2020, 52, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolli, L.M.; de Oliveira, D.G.R.; Alves, S.S.; von Zuben, M.V.; Pic-Taylor, A.; Mortari, M.R.; Caldas, E.D. Effects of the hallucinogenic beverage ayahuasca on voluntary ethanol intake by rats and on cFos expression in brain areas relevant to drug addiction. Alcohol 2020, 84, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talin, P.; Sanabria, E. Ayahuasca’s entwined efficacy: An ethnographic study of ritual healing from “addiction”. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 44, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizaga-Velder, A.; Verres, R. Therapeutic effects of ritual ayahuasca use in the treatment of substance dependence--qualitative results. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2014, 46, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apud Peláez, I.E. Personality Traits in Former Spanish Substance Users Recovered with Ayahuasca. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2020, 52, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, D.; Carvalho, M.; Cantillo, J.; Aixalá, M.; Farré, M. Potential Use of Ayahuasca in Grief Therapy. Omega 2019, 79, 260–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthaug, M.V.; van Oorsouw, K.; Kuypers, K.P.C.; van Boxtel, M.; Broers, N.J.; Mason, N.L.; Toennes, S.W.; Riba, J.; Ramaekers, J.G. Sub-acute and long-term effects of ayahuasca on affect and cognitive thinking style and their association with ego dissolution. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 2979–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthaug, M.V.; Mason, N.L.; Toennes, S.W.; Reckweg, J.T.; de Sousa Fernandes Perna, E.B.; Kuypers, K.P.C.; van Oorsouw, K.; Riba, J.; Ramaekers, J.G. A placebo-controlled study of the effects of ayahuasca, set and setting on mental health of participants in ayahuasca group retreats. Psychopharmacology 2021, 238, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, J.; Elices, M.; Franquesa, A.; Barker, S.; Friedlander, P.; Feilding, A.; Pascual, J.C.; Riba, J. Exploring the therapeutic potential of Ayahuasca: Acute intake increases mindfulness-related capacities. Psychopharmacology 2016, 233, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Gurel, L. A Study of Ayahuasca Use in North America. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2012, 44, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, P.C.R.; Giglio, J.S.; Dalgalarrondo, P. Altered states of consciousness and short-term psychological after-effects induced by the first time ritual use of ayahuasca in an urban context in Brazil. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2005, 37, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riba, J.; Rodríguez-Fornells, A.; Urbano, G.; Morte, A.; Antonijoan, R.; Montero, M.; Callaway, J.C.; Barbanoj, M.J. Subjective effects and tolerability of the South American psychoactive beverage Ayahuasca in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology 2001, 154, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Clavé, E.; Soler, J.; Pascual, J.C.; Elices, M.; Franquesa, A.; Valle, M.; Alvarez, E.; Riba, J. Ayahuasca improves emotion dysregulation in a community sample and in individuals with borderline-like traits. Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franquesa, A.; Sainz-Cort, A.; Gandy, S.; Soler, J.; Alcázar-Córcoles, M.Á.; Bouso, J.C. Psychological variables implied in the therapeutic effect of ayahuasca: A contextual approach. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 264, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frecska, E.; Móré, C.E.; Vargha, A.; Luna, L.E. Enhancement of creative expression and entoptic phenomena as after-effects of repeated ayahuasca ceremonies. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2012, 44, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B.; Miller, J.D.; Carter, N.T.; Keith Campbell, W. Examining changes in personality following shamanic ceremonial use of ayahuasca. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnoli, A.P.S.; Pereira, L.A.S.; Bueno, J.L.O. Subjective time under altered states of consciousness in ayahuasca users in shamanistic rituals involving music. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. = Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Med. e Biol. 2020, 53, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichter, S.; Klimo, J.; Krippner, S. Changes in spirituality among ayahuasca ceremony novice participants. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2009, 41, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussmann, R.W.; Malca-García, G.; Glenn, A.; Sharon, D.; Chait, G.; Díaz, D.; Pourmand, K.; Jonat, B.; Somogy, S.; Guardado, G.; et al. Minimum inhibitory concentrations of medicinal plants used in Northern Peru as antibacterial remedies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 132, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, M.; Tan, S.; Wang, C.; Fan, S.; Huang, C. Harmine is an inflammatory inhibitor through the suppression of NF-κB signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 489, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão-Coelho, N.L.; de Menezes Galvão, A.C.; de Almeida, R.N.; Palhano-Fontes, F.; Campos Braga, I.; Lobão Soares, B.; Maia-de-Oliveira, J.P.; Perkins, D.; Sarris, J.; de Araujo, D.B. Changes in inflammatory biomarkers are related to the antidepressant effects of Ayahuasca. J. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 34, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katchborian-Neto, A.; Santos, W.T.; Nicácio, K.J.; Corrêa, J.O.A.; Murgu, M.; Martins, T.M.M.; Gomes, D.A.; Goes, A.M.; Soares, M.G.; Dias, D.F.; et al. Neuroprotective potential of Ayahuasca and untargeted metabolomics analyses: Applicability to Parkinson’s disease. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 255, 112743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Garcia, J.A.; Calleja-Conde, J.; Lopez-Moreno, J.A.; Alonso-Gil, S.; Sanz-SanCristobal, M.; Riba, J.; Perez-Castillo, A. N,N-dimethyltryptamine compound found in the hallucinogenic tea ayahuasca, regulates adult neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samoylenko, V.; Rahman, M.M.; Tekwani, B.L.; Tripathi, L.M.; Wang, Y.H.; Khan, S.I.; Khan, I.A.; Miller, L.S.; Joshi, V.C.; Muhammad, I. Banisteriopsis caapi, a unique combination of MAO inhibitory and antioxidative constituents for the activities relevant to neurodegenerative disorders and Parkinson’s disease. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 127, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, M.J.; Houghton, P.J.; Rose, S.; Jenner, P.; Lees, A.D. Activities of extract and constituents of Banisteriopsis caapi relevant to parkinsonism. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003, 75, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouso, J.C.; Fábregas, J.M.; Antonijoan, R.M.; Rodríguez-Fornells, A.; Riba, J. Acute effects of ayahuasca on neuropsychological performance: Differences in executive function between experienced and occasional users. Psychopharmacology 2013, 230, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafrance, A.; Loizaga-Velder, A.; Fletcher, J.; Renelli, M.; Files, N.; Tupper, K.W. Nourishing the Spirit: Exploratory Research on Ayahuasca Experiences along the Continuum of Recovery from Eating Disorders. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2017, 49, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.G.; Grasa, E.; Valle, M.; Ballester, M.R.; Bouso, J.C.; Nomdedéu, J.F.; Homs, R.; Barbanoj, M.J.; Riba, J. Pharmacology of ayahuasca administered in two repeated doses. Psychopharmacology 2012, 219, 1039–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, J.H.; Sherwood, A.R.; Passie, T.; Blackwell, K.C.; Ruttenber, A.J. Evidence of health and safety in American members of a religion who use a hallucinogenic sacrament. Med. Sci. Monit. 2008, 14, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, S.M.; Soubhia, P.C.; Silveira, G.; Corrêa-Neto, N.F.; Lanaro, R.; Costa, J.L.; Linardi, A. Effect of Ritualistic Consumption of Ayahuasca on Hepatic Function in Chronic Users. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2018, 51, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid-Gambin, F.; Gomez-Gomez, A.; Busquets-Garcia, A.; Haro, N.; Marco, S.; Mason, N.L.; Reckweg, J.T.; Mallaroni, P.; Kloft, L.; van Oorsouw, K.; et al. Metabolomics and integrated network analysis reveal roles of endocannabinoids and large neutral amino acid balance in the ayahuasca experience. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 149, 112845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riba, J.; Anderer, P.; Morte, A.; Urbano, G.; Jané, F.; Saletu, B.; Barbanoj, M.J. Topographic pharmaco-EEG mapping of the effects of the South American psychoactive beverage ayahuasca in healthy volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 53, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenberg, E.E.; Alexandre, J.F.M.; Filev, R.; Cravo, A.M.; Sato, J.R.; Muthukumaraswamy, S.D.; Yonamine, M.; Waguespack, M.; Lomnicka, I.; Barker, S.A.; et al. Acute Biphasic Effects of Ayahuasca. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, D.I.; Davidson, C. Harmine augments electrically evoked dopamine efflux in the nucleus accumbens shell. J. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 27, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.G.; Valle, M.; Bouso, J.C.; Nomdedéu, J.F.; Rodríguez-Espinosa, J.; McIlhenny, E.H.; Barker, S.A.; Barbanoj, M.J.; Riba, J. Autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immunological effects of ayahuasca: A comparative study with d-amphetamine. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 31, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakic, V.; de Moraes Maciel, R.; Drummond, H.; Nascimento, J.M.; Trindade, P.; Rehen, S.K. Harmine stimulates proliferation of human neural progenitors. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riba, J.; Anderer, P.; Jané, F.; Saletu, B.; Barbanoj, M.J. Effects of the South American psychoactive beverage ayahuasca on regional brain electrical activity in humans: A functional neuroimaging study using low-resolution electromagnetic tomography. Neuropsychobiology 2004, 50, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viol, A.; Palhano-Fontes, F.; Onias, H.; De Araujo, D.B.; Viswanathan, G.M. Shannon entropy of brain functional complex networks under the influence of the psychedelic Ayahuasca. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, T.A.; Polesel, D.N.; Matos, G.; Garcia, V.A.; Costa, J.L.; Tufik, S.; Andersen, M.L. Can Ayahuasca and sleep loss change sexual performance in male rats? Behav. Processes 2014, 108, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbanoj, M.J.; Riba, J.; Clos, S.; Giménez, S.; Grasa, E.; Romero, S. Daytime Ayahuasca administration modulates REM and slow-wave sleep in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology 2008, 196, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riba, J.; Rodríguez-Fornells, A.; Barbanoj, M.J. Effects of ayahuasca on sensory and sensorimotor gating in humans as measured by P50 suppression and prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex, respectively. Psychopharmacology 2002, 165, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira-Lima, A.J.; Santos, R.; Hollais, A.W.; Gerardi-Junior, C.A.; Baldaia, M.A.; Wuo-Silva, R.; Yokoyama, T.S.; Costa, J.L.; Malpezzi-Marinho, E.L.A.; Ribeiro-Barbosa, P.C.; et al. Effects of ayahuasca on the development of ethanol-induced behavioral sensitization and on a post-sensitization treatment in mice. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 142, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitol, D.L.; Siéssere, S.; Dos Santos, R.G.; Rosa, M.L.N.M.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Scalize, P.H.; Pereira, B.F.; Iyomasa, M.M.; Semprini, M.; Riba, J.; et al. Ayahuasca Alters Structural Parameters of the Rat Aorta. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2015, 66, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, Y.A.; Barros-Santos, T.; Anjos-Santos, A.; Kisaki, N.D.; Jovita-Farias, C.; Leite, J.P.C.; Santana, M.C.E.; Coimbra, J.P.S.A.; de Jesus, N.M.S.; Sulima, A.; et al. Role of 5-HT2A receptors in the effects of ayahuasca on ethanol self-administration using a two-bottle choice paradigm in male mice. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frecska, E.; White, K.D.; Luna, L.E. Effects of ayahuasca on binocular rivalry with dichoptic stimulus alternation. Psychopharmacology 2004, 173, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frecska, E.; White, K.D.; Luna, L.E. Effects of the Amazonian psychoactive beverage Ayahuasca on binocular rivalry: Interhemispheric switching or interhemispheric fusion? J. Psychoact. Drugs 2003, 35, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummrow, F.; Maselli, B.S.; Lanaro, R.; Costa, J.L.; Umbuzeiro, G.A.; Linardi, A. Mutagenicity of Ayahuasca and Their Constituents to the Salmonella/Microsome Assay. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2019, 60, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colaço, C.S.; Alves, S.S.; Nolli, L.M.; Pinheiro, W.O.; de Oliveira, D.G.R.; Santos, B.W.L.; Pic-Taylor, A.; Mortari, M.R.; Caldas, E.D. Toxicity of ayahuasca after 28 days daily exposure and effects on monoamines and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in brain of Wistar rats. Metab. Brain Dis. 2020, 35, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pic-Taylor, A.; da Motta, L.G.; de Morais, J.A.; Junior, W.M.; de Fátima Andrade Santos, A.; Campos, L.A.; Mortari, M.R.; von Zuben, M.V.; Caldas, E.D. Behavioural and neurotoxic effects of ayahuasca infusion (Banisteriopsis caapi and Psychotria viridis) in female Wistar rat. Behav. Processes 2015, 118, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Motta, L.G.; de Morais, J.A.; Tavares, A.C.A.M.; Vianna, L.M.S.; Mortari, M.R.; Amorim, R.F.B.; Carvalho, R.R.; Paumgartten, F.J.R.; Pic-Taylor, A.; Caldas, E.D. Maternal and developmental toxicity of the hallucinogenic plant-based beverage ayahuasca in rats. Reprod. Toxicol. 2018, 77, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, A.Y.; Gonçalves, J.; Gradillas, A.; García, A.; Restolho, J.; Fernández, N.; Rodilla, J.M.; Barroso, M.; Duarte, A.P.; Cristóvão, A.C.; et al. Evaluation of the Cytotoxicity of Ayahuasca Beverages. Molecules 2020, 25, 5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLOS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Altman, D.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Estarli, M.; Barrera, E.S.A.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Studied Sample | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Ayahuasca beverage | Reduction in anxiety and depression behaviors | [27] |

| Increased anxiety (childhood), memory impairment (adolescence), unchecked changes (adult) | [28] | |

| Decreased depression, increased psychoactivity, increased blood perfusion in regions that regulate emotions and mood | [29] | |

| No change in anxiety, decrease in panic and hopelessness | [30] | |

| Mindfulness reduced the severity of depression and depressive symptoms | [31] | |

| No decrease in ethanol intake. Ethanol increased cFos expression after being treated with ayahuasca | [32] | |

| The effectiveness of ayahuasca in treating addiction depends on guidance during the ritual | [33] | |

| Potential substance addiction treatment and relapse prevention | [34] | |

| Improved impulsivity, compassion, attachment and spiritual acceptance, self-transcendence and novelty seeking. | [35] | |

| Benefits in some psychological and interpersonal dimensions, biographical memories, emotional release and contact experiences with the deceased | [36] | |

| Improvements in affect and thinking style, life satisfaction and mindfulness. Decreased depression and stress. Correlation between changes in affect, life satisfaction and mindfulness and the level of ego dissolution | [37] | |

| placebo-related beneficial mental health effects | [38] | |

| Decreased internal reactivity and judgmental processing of experiences. Increased decentralization capacity | [39] | |

| Increased healthier diets, reduced alcohol intake, improved mood, self-acceptance and relationships | [40] | |

| Improved tranquillity, visual phenomena, insights, numinosity. Decreased psychiatric symptoms. Increased serenity, vivacity/cheerfulness and assertiveness | [41] | |

| Improved psychological effects. Tolerability at the cardiovascular level. | [42] | |

| Improvement in emotional non-acceptance, emotional interference, lack of control, state of consciousness and decentralization. No change in mindfulness abilities. | [43] | |

| Decrease in the values of achievement in life, living valued, self in close relationships, self in social relationships and general self. Improved results for positive self and decentralization | [44] | |

| Enhancement of divergent creative thinking and increased psychological flexibility | [26] | |

| Increased phosphenic and original responses, visual creativity and entoptic activity | [45] | |

| Alteration of neuroticism and moderation of personality | [46] | |

| Decreased temporal distortion | [47] | |

| Increased Peak Experience Profile and Spiritual Well-being at Mysticism | [48] |

| Studied Sample | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 141 plant species | Inhibition of growth of E. coli and S. aureus | [49] |

| P. viridis, B. caapi, M. hostilis, P. harmala and a commercial mixture of beverages | Inhibition of bacterial growth in all strains. Anti-quorum sensing properties. Anti-biofilm activity in two samples on the same strain. | [7] |

| Studied Sample | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| P. viridis, B. caapi, M. hostilis, P. harmala and a commercial mixture beverages | Presentation of anti-inflammatory activity | [7] |

| Ayahuasca beverage | Negative correlation between C-reactive protein and serum cortisol levels. Decreased levels of C-reactive protein and correlation between greater reductions in C-reactive protein and less depressive symptoms | [51] |

| P. harmala beverage | Harmine showed anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the NF-kB signaling pathway | [50] |

| Studied Sample | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| P. viridis, B. caapi extracts and Harmine and DMT | Neuroprotective effect on crude extracts and hydroalcoholic fractions. Stimulation of cell proliferation and neuroprotection profile at lower doses | [52] |

| DMT | Increased proliferation of neural stem cells, migration of neuroblasts, promoting the generation of new neurons. Increased adult neurogenesis and improved learning tasks and spatial memory. | [53] |

| B. caapi extracts | Therapeutic potential of B. caapi stem extract in the treatment of Parkinsonism and other neurodegenerative disorders | [54] |

| B. caapi extract, harmine and harmaline | Therapeutic potential of B. caapi extract in Parkinson’s disease | [55] |

| P. viridis, B. caapi, M. hostilis, P. harmala and a commercial mixture beverages | Potential wound-healing effect | [1] |

| Ayahuasca beverage | Decreased working memory. Decreased disability by promoting neuromodulatory or compensatory effects on executive function | [56] |

| Reductions in thoughts and symptoms related to eating disorders, anxiety, depression, self-harm, suicide and problematic substance use | [57] | |

| Significant decrease in growth hormone, heart rate and systolic blood pressure. No differences in autonomic, neurophysiological or immunological effects | [58] | |

| Remission of individuals dependent on substances or with a psychiatric disorder after participation in the church | [59] |

| Studied Sample | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Ayahuasca beverage | No changes in liver function | [60] |

| Changes in several large neutral amino acids, decrease in 2-acyl-glycerol endocannabinoids and increase in N-acyl-ethanolamine endocannabinoids. Dysregulation of various neurotransmission pathways. Subjective effects associated with large neutral amino acids. Alkaloid concentrations unrelated to subjective effects or metabolism | [61] | |

| Decreased power in frequency bands. Increased total centroid activity. Support of 5-HT2 and dopamine receptor agonism in ayahuasca-induced effects | [62] | |

| Increased diastolic blood pressure, heart rate and systolic blood pressure. Increased urinary excretion of normetanephrine without decrease in deaminated monoamine metabolite levels. Results indicative of a predominantly peripheral metabolism of harmine | [18] | |

| Decreased alpha-band potency in the brain and increased slow- and fast-range potency associated with levels of DMT, harmine, harmaline and tetrahydroharmine and some of their metabolites | [63] | |

| Stimulation of neuroendocrine and immunomodulatory function and led to the appearance of sympathomimetic effects | [65] | |

| Harmine | Increased dopamine flux in the concha accumbens after harmine administration. Harmine leads to an increase in dopamine efflux by a presynaptic 5-HT(2A) receptor-dependent mechanism. Possible therapy for cocaine addiction | [64] |

| Studied Sample | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Harmine | Inhibition of the regulator of cell proliferation and brain development by harmine. Induction of proliferation of human neural progenitor cells by a harmine analog | [66] |

| Ayahuasca beverage | Decreased locomotor activity, loss of balance, delayed hatching, accumulation of red blood cells and edema | [14] |

| Significant differences in low-resolution electromagnetic tomography between groups. Decreased power density in the theta, alpha-2, delta and beta-1 frequency bands. Possible involvement of the unimodal and heteromodal association cortex and limbic structures in the psychological effects caused by ayahuasca. | [67] | |

| Increased blood perfusion in areas implicated in subjective feeling states, somatic awareness, emotional arousal and left amygdala/parahippocampal gyrus. Possible association of ayahuasca with the neurotransmission of neural systems involved in interoception and emotional processing. | [20] | |

| Increase in the Shannon entropy of the degree distribution of networks | [68] | |

| Ayahuasca ingestion, combined with sleep deprivation, decreased sexual performance | [69] | |

| Inhibition of rapid eye movement sleep by increasing onset latency. No induction of deterioration in sleep quality nor interruption of sleep. Increased power in the high-frequency range and slow-wave sleep power | [70] | |

| No significant changes in prepulse inhibition of startle, habituation rate or startle response. Significant decrease in P50 suppression. No effects on sensorimotor gating, but decreasing effect on sensory gating | [71] | |

| Prevention of the development of behavioral sensitization caused by ethanol. Block in the expression of sensitization. Inhibition and reversal of behaviors associated with ethanol dependence. | [72] | |

| Stretching and flattening of vascular smooth muscle cells. Changes in the arrangement and distribution of collagen and elastic fibers | [73] | |

| Potential therapeutic effect of ayahuasca in the treatment of alcohol dependence | [74] | |

| Increased dominance time under standard binocular rivalry conditions such as binocular rivalry | [75] | |

| Increased percept length, and decreased rivalry switching rates | [76] |

| Studied Sample | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| P. viridis and B. caapi beverages; Harmine and harmaline | Mutagenicity induced by ayahuasca beverages for TA98 TA100. Mutagenicity induced by harmaline and B. caapi drink for TA98. Drink of P. viridis and harmine without mutagenicity | [77] |

| Ayahuasca beverage | Increased serotonin (Aya2) levels and decreased 5-HIAA metabolite. No changes for dopamine and HVA metabolite, but increased DOPAC metabolite (Aya1 and Aya2), increased DOPAC/dopamine turnover (Aya2) and decreased HVA/DOPAC ratio in male groups (Aya0.5, Aya1 and Aya2). Increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor in female groups (FLX and Aya2). | [78] |

| Decreased locomotion in the open field test elevated plus maze tests. Increased movement in the forced swimming test and increased neuronal activation in all brain areas involved in serotonergic neurotransmission. No permanent damage | [79] | |

| 56% and 48% survival for 4× and 8× ayahuasca with kidney damage. Neuronal losses in the hippocampus and raphe nuclei, intrauterine growth retardation, induced embryonic deaths and increased occurrence of fetal anomalies | [80] | |

| P. viridis, B. caapi, M. hostilis, P. harmala and a commercial mixture beverages | Induction of cytotoxicity in the N27 cell line by harmine, harmaline and THH and by extracts of P. harmala, B. caapi and a commercial mixture. No cytotoxicity for DMT. | [81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonçalves, J.; Luís, Â.; Gallardo, E.; Duarte, A.P. A Systematic Review on the Therapeutic Effects of Ayahuasca. Plants 2023, 12, 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12132573

Gonçalves J, Luís Â, Gallardo E, Duarte AP. A Systematic Review on the Therapeutic Effects of Ayahuasca. Plants. 2023; 12(13):2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12132573

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonçalves, Joana, Ângelo Luís, Eugenia Gallardo, and Ana Paula Duarte. 2023. "A Systematic Review on the Therapeutic Effects of Ayahuasca" Plants 12, no. 13: 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12132573

APA StyleGonçalves, J., Luís, Â., Gallardo, E., & Duarte, A. P. (2023). A Systematic Review on the Therapeutic Effects of Ayahuasca. Plants, 12(13), 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12132573