RNA-Seq-Based WGCNA and Association Analysis Reveal the Key Regulatory Module and Genes Responding to Salt Stress in Wheat Roots

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. RNA-Seq Data Evaluation

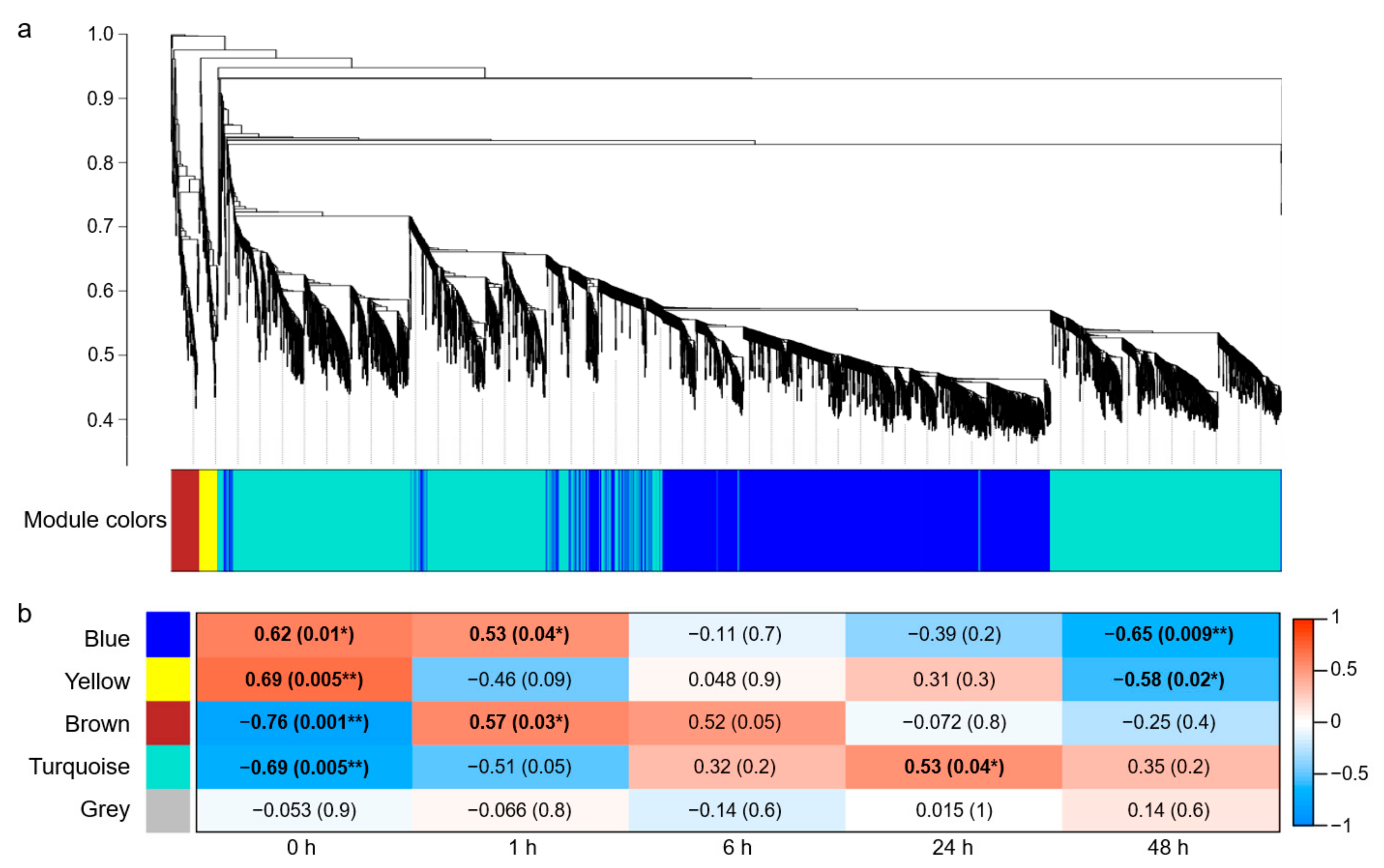

2.2. Gene Co-Expression Modules Responding to Salt Stress in Roots

2.3. The GO Enrichment of the Blue Module

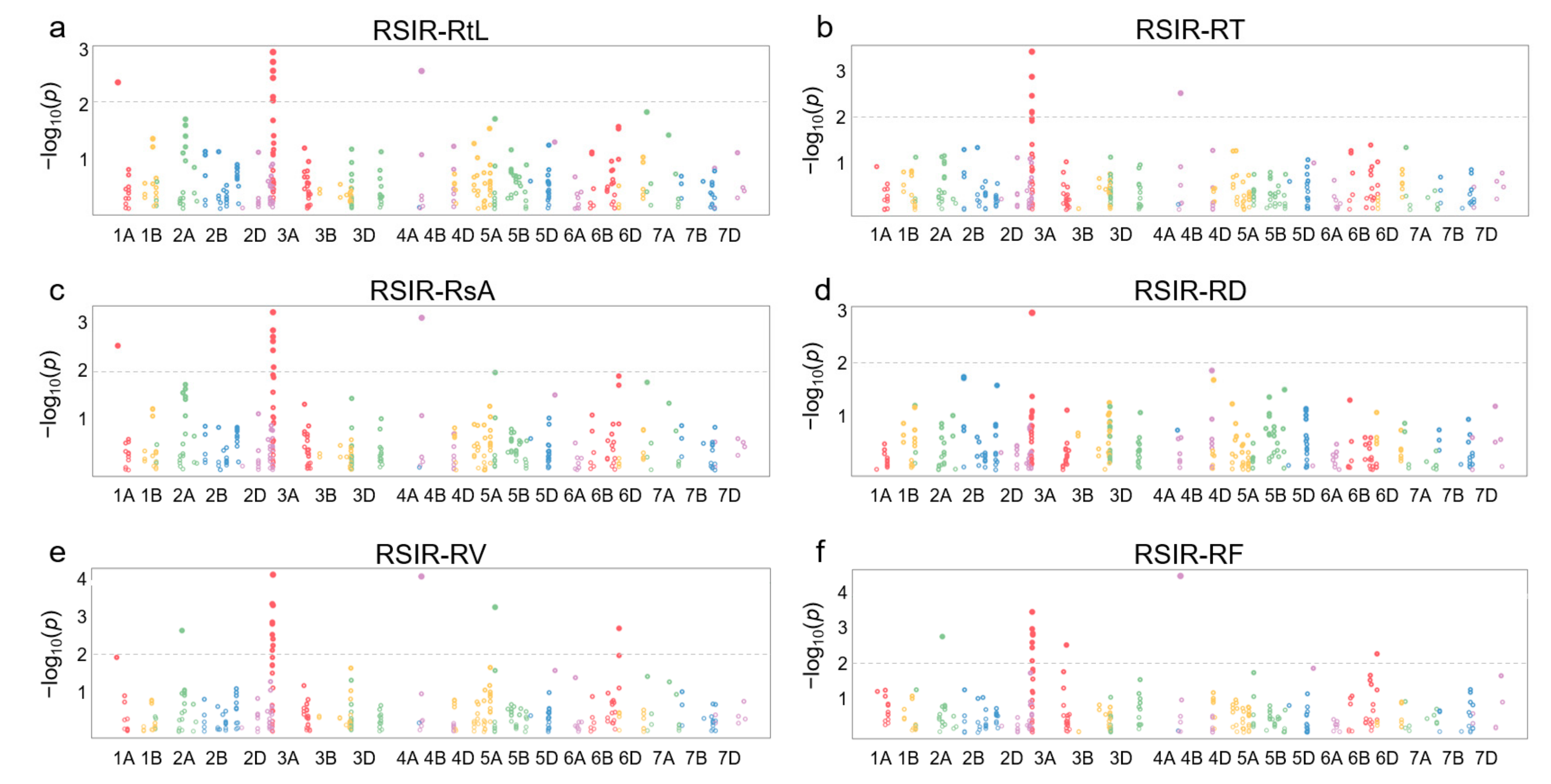

2.4. Association Analysis of the DEGs from the Key Terms

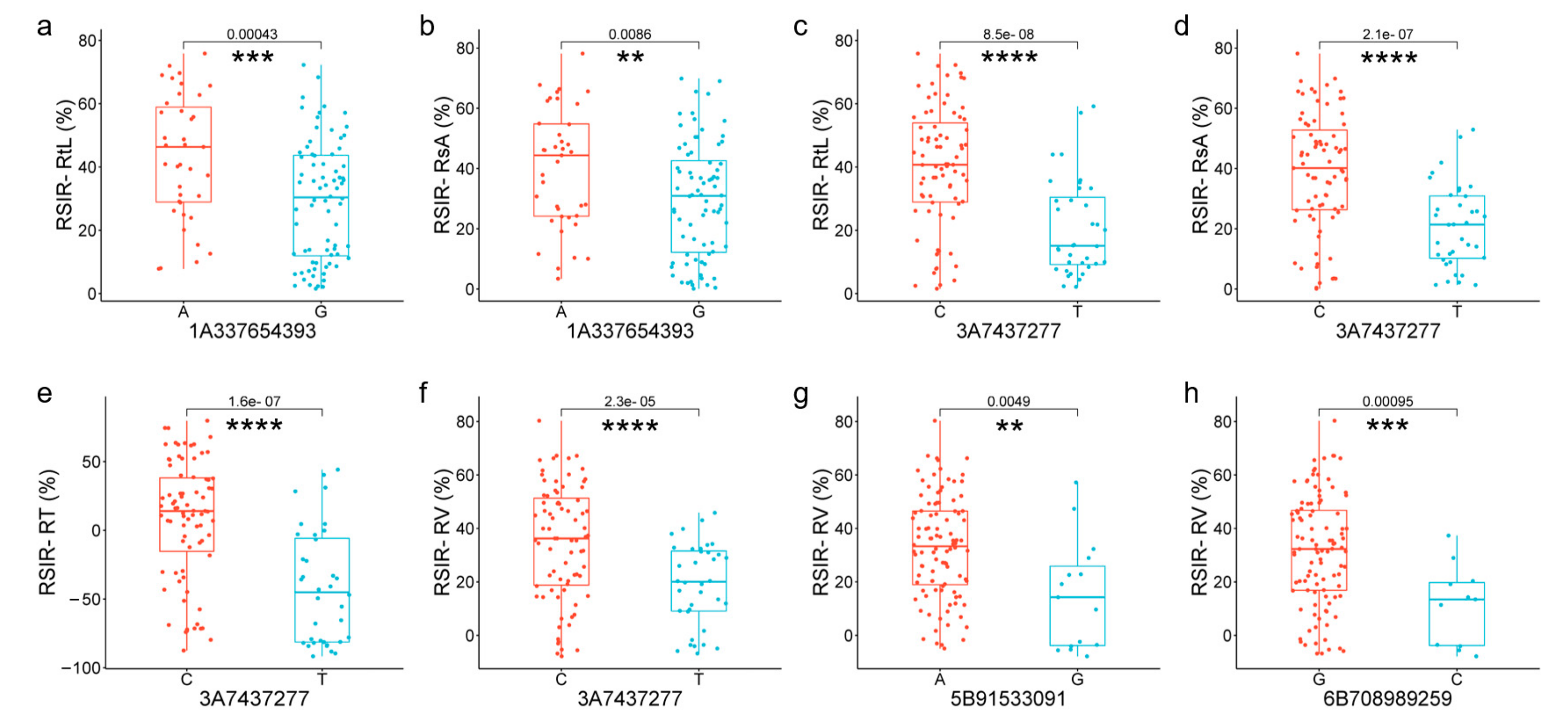

2.5. Candidate Genes Responding to Salt Stress in Roots

2.6. Gene Co-Expression Networks Responding to Short-Term Salt Stress in Roots

3. Discussion

3.1. The Blue Module Is Related to the Time Course of Salt-Stress Response in Wheat Roots

3.2. Four Novel Candidate Genes Responding to Salt Stress Discovered from the Blue Module

3.3. A Predicted Gene Co-Expression Network for Salt Tolerance

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Salt Treatment

4.2. RNA-Seq

4.3. Co-Expression Network Construction

4.4. Association Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hassani, A.; Azapagic, A.; Shokri, N. Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopmans, J.W.; Qureshi, A.S.; Kisekka, I.; Munns, R.; Grattan, S.R.; Rengasamy, P.; Ben-Gal, A.; Assouline, S.; Javaux, M.; Minhas, P.S.; et al. Chapter One—Critical knowledge gaps and research priorities in global soil salinity. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 169, pp. 1–191. [Google Scholar]

- Shewry, P.R.; Hey, S.J. The contribution of wheat to human diet and health. Food Energy Secur. 2015, 4, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Pan, W.; Cao, R.; Guo, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Cui, L.; Nie, X. Multi-omics reveals the key and specific miRNA-mRNA modules underlying salt tolerance in wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides L.). BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, M.; Kugler, K.G.; Sandve, S.R.; Zhan, B.; Rudi, H.; Hvidsten, T.R.; Mayer, K.F.; Olsen, O.A.; International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium. Genome interplay in the grain transcriptome of hexaploid bread wheat. Science 2014, 345, 1250091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Hua, L.; Zhao, S.; Hao, M.; Song, R.; Pang, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, W.; Shen, T.; et al. Cloning of the wheat leaf rust resistance gene Lr47 introgressed from Aegilops speltoides. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, N.; Wang, S.; Tian, H.; Liu, L.; Pei, D.; Yu, X.; Zhao, L.; Chen, F. A TaSnRK1α modulates TaPAP6L-mediated wheat cold tolerance through regulating endogenous jasmonic acid. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2303478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, E.; Amit, S.K.; Singh, R.S.; Mahato, A.K.; Chand, S.; Kanika, K. Transcriptome profiling of the salt-stress response in Triticum aestivum cv. Kharchia Local. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, M.M.; Goyal, E.; Singh, A.K.; Gaikwad, K.; Kanika, K. Transcriptome dynamics provide insights into long-term salinity stress tolerance in Triticum aestivum cv. Kharchia Local. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 121, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyahya, N.; Taybi, T. Comparative transcriptomic profiling reveals differentially expressed genes and important related metabolic pathways in shoots and roots of a Saudi wheat cultivar (Najran) under salinity stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1225541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Khan, A.A.; Lin, Q.; Han, Y.; Mu, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Meng, X.; et al. Expression partitioning of homeologs and tandem duplications contribute to salt tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Teng, W.; Fang, S.; Li, H.; Li, B.; Chu, J.; Li, Z.; Zheng, Q. Transcriptome analysis of salt-stress response in three seedling tissues of common wheat. Crop J. 2019, 7, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugasa, M.; Feng, X.; Wang, N.; Wang, J.; Wu, F. Comparative transcriptome and tolerance mechanism analysis in the two contrasting wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars in response to drought and salinity stresses. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 94, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cao, J.; Huang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Zou, J.; Wang, F.; Luo, M.; Zhang, J. Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics analyses provide insights into salt-stress response in germination and seedling stage of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Curr. Plant Biol. 2023, 33, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirbakhtiar, N.; Ismaili, A.; Ghaffari, M.R.; Mirdar Mansuri, R.; Sanjari, S.; Shobbar, Z.S. Transcriptome analysis of bread wheat leaves in response to salt stress. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boursiac, Y.; Chen, S.; Luu, D.T.; Sorieul, M.; van den Dries, N.; Maurel, C. Early effects of salinity on water transport in Arabidopsis roots. Molecular and cellular features of aquaporin expression. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 790–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demidchik, V.; Tester, M. Sodium fluxes through nonselective cation channels in the plasma membrane of protoplasts from Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Dietrich, D.; Ng, C.H.; Chan, P.M.; Bhalerao, R.; Bennett, M.J.; Dinneny, J.R. Endodermal ABA signaling promotes lateral root quiescence during salt stress in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Cell. 2013, 25, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.G.; Toyota, M.; Kim, S.H.; Hilleary, R.; Gilroy, S. Salt stress-induced Ca2+ waves are associated with rapid, long-distance root-to-shoot signaling in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 6497–6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Xie, H.; Wei, X.; Dossa, K.; Yu, Y.; Hui, S.; Tang, G.; Zeng, X.; Yu, Y.; Hu, P.; et al. WGCNA analysis of salt-responsive core transcriptome identifies novel hub genes in rice. Genes 2019, 10, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, J.; Qing, C.; He, S.; Zou, C.; Yuan, G.; Yang, C.; Peng, H.; Pan, G.; et al. GWAS and WGCNA uncover hub genes controlling salt tolerance in maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 3305–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; et al. Comparative transcriptome responses of leaf and root tissues to salt stress in wheat strains with different salinity tolerances. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1015599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, R.; Jia, J.; Yan, L.; Chang, Z. Genetic incorporation of genes for the optimal plant architecture in common wheat. Mol. Breed. 2022, 42, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zelm, E.; Zhang, Y.; Testerink, C. Salt tolerance mechanisms of plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 403–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maathuis, F.J. The role of monovalent cation transporters in plant responses to salinity. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, L.; He, K.; Higaki, T.; Wang, X.; Mao, T. Ethylene signaling modulates cortical microtubule reassembly in response to salt Stress. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Wu, R.; Wee, C.W.; Xie, F.; Wei, X.; Chan, P.M.; Tham, C.; Duan, L.; Dinneny, J.R. A spatio-temporal understanding of growth regulation during the salt stress response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 2132–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranocha, P.; Dima, O.; Nagy, R.; Felten, J.; Corratgé-Faillie, C.; Novák, O.; Morreel, K.; Lacombe, B.; Martinez, Y.; Pfrunder, S.; et al. Arabidopsis WAT1 is a vacuolar auxin transport facilitator required for auxin homoeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, W.; Chen, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, S. Transcriptomic analysis of salt tolerance-associated genes and diversity analysis using indel markers in yardlong bean (Vigna unguiculata ssp. sesquipedialis). BMC Genom. Data 2021, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho da Silva, T.L.; Belo Silva, V.N.; Braga, Í.O.; Rodrigues Neto, J.C.; Leão, A.P.; Ribeiro, J.A.A.; Valadares, L.F.; Abdelnur, P.V.; de Sousa, C.A.F.; Souza, M.T., Jr. Integration of metabolomics and transcriptomics data to further characterize Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Kunth under high salinity stress. Plant Genome 2022, 15, e20182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irizarry, I.; White, J.F. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens alters gene expression, ROS production and lignin synthesis in cotton seedling roots. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 124, 1589–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domec, J.C.; King, J.S.; Carmichael, M.J.; Overby, A.T.; Wortemann, R.; Smith, W.K.; Miao, G.; Noormets, A.; Johnson, D.M. Aquaporins, and not changes in root structure, provide new insights into physiological responses to drought, flooding, and salinity. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 4489–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; He, X.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, C.; Liang, Y.; Ge, R.; Shen, Y.; Huang, Z. Overexpressing a putative aquaporin gene from wheat, TaNIP, enhances salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010, 51, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Cai, R.; Deng, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, S.; Chen, M.; Chen, L.; Huang, C.; et al. Overexpression of a wheat aquaporin gene, TaAQP8, enhances salt stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 2127–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Fricke, W. Changes in root hydraulic conductivity in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in response to salt stress and day/night can best be explained through altered activity of aquaporins. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Vij, S.; Tyagi, A.K. Overexpression of a zinc-finger protein gene from rice confers tolerance to cold, dehydration, and salt stress in transgenic tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 6309–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, H.; Maruyama, K.; Sakuma, Y.; Meshi, T.; Iwabuchi, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis Cys2/His2-type zinc-finger proteins function as transcription repressors under drought, cold, and high-salinity stress conditions. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 2734–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chu, Z.; Luo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xia, J.; Kuang, H.; Ye, Z.; Ouyang, B. The C2H2 zinc-finger protein SlZF3 regulates AsA synthesis and salt tolerance by interacting with CSN5B. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 1201–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lv, J.; Zhao, X.; Ai, X.; Zhu, X.; Wang, M.; Zhao, S.; Xia, G. TaCHP: A wheat zinc finger protein gene down-regulated by abscisic acid and salinity stress plays a positive role in stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, G.G.; Mahan, J.R.; Roxas, V.P.; Allen, R.D. Transgenic cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) seedlings expressing a tobacco glutathione S-transferase fail to provide improved stress tolerance. Planta 2005, 222, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; He, Q.; Daud, M.K.; Chen, J.; Zhu, S. Glutathione S-transferase gene family in Gossypium raimondii and G. arboreum: Comparative genomic study and their expression under salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Cai, Z.; Ma, Q.; Wen, K.; Nian, H. GmGSTU23 encoding a Tau class glutathione S-transferase protein enhances the salt tolerance of soybean (Glycine max L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Martret, B.; Poage, M.; Shiel, K.; Nugent, G.D.; Dix, P.J. Tobacco chloroplast transformants expressing genes encoding dehydroascorbate reductase, glutathione reductase, and glutathione-S-transferase, exhibit altered anti-oxidant metabolism and improved abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011, 9, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Xia, Y.; Xie, Q.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hao, G.; Song, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, X. The protein kinase complex CBL10-CIPK8-SOS1 functions in Arabidopsis to regulate salt tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 1801–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ding, Y.; Yang, Y.; Song, C.; Wang, B.; Yang, S.; Guo, Y.; Gong, Z. Protein kinases in plant responses to drought, salt, and cold stress. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Han, H.; Liu, M.; Zuo, Z.; Zhou, K.; Lü, J.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y. Overexpression of the Arabidopsis photorespiratory pathway gene, serine: Glyoxylate aminotransferase (AtAGT1), leads to salt stress tolerance in transgenic duckweed (Lemna minor). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2023, 113, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Song, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Sui, N. NADP-malate dehydrogenase of sweet sorghum improves salt tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 5992–6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.S.; Xia, L.Q.; Chen, M.; Cheng, X.G.; Zhang, R.Y.; Li, L.C.; Zhao, Y.X.; Lu, Y.; Ni, Z.Y.; Liu, L.; et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of the Triticum aestivum L. ethylene-responsive factor 1 (TaERF1) that increases multiple stress tolerance. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 65, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, W.; Qi, L.; Wang, A.; Ye, X.; Du, L.; Liang, H.; Xin, Z.; Zhang, Z. The ERF transcription factor TaERF3 promotes tolerance to salt and drought stresses in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Ai, X.; Xu, F.; Quan, T.; Liu, S.; Xia, G. Isolation and characterization of a bread wheat salinity responsive ERF transcription factor. Gene 2012, 511, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaxiola, R.A.; Rao, R.; Sherman, A.; Grisafi, P.; Alper, S.L.; Fink, G.R. The Arabidopsis thaliana proton transporters, AtNhx1 and Avp1, can function in cation detoxification in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsugane, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Niwa, Y.; Ohba, Y.; Wada, K.; Kobayashi, H. A recessive Arabidopsis mutant that grows photoautotrophically under salt stress shows enhanced active oxygen detoxification. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, N.A.; Gill, R.; Kaushik, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Pereira, E.; Ahmad, I.; Tuteja, N.; Gill, S.S. ATP-sulfurylase, sulfur-compounds, and plant stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Li, Y.J.; Zhang, F.J.; Zhang, G.Z.; Jiang, X.Y.; Yu, H.M.; Hou, B.K. The Arabidopsis UDP-glycosyltransferases UGT79B2 and UGT79B3, contribute to cold, salt and drought stress tolerance via modulating anthocyanin accumulation. Plant J. 2017, 89, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Peng, L.; Xiong, J.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Yang, Y. AtSIBP1, a novel BTB domain-containing protein, positively regulates salt signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants 2019, 8, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Ma, Y.; Huang, X.; Mu, T.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Hou, B. Overexpression of OsUGT3 enhances drought and salt tolerance through modulating ABA synthesis and scavenging ROS in rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 192, 104653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Jiang, S.; Dai, M.; Shi, H.; Zhu, H.; Guo, Z. Zinc finger transcription factor MtZPT2-2 negatively regulates salt tolerance in Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodaira, K.S.; Qin, F.; Tran, L.S.; Maruyama, K.; Kidokoro, S.; Fujita, Y.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis Cys2/His2 zinc-finger proteins AZF1 and AZF2 negatively regulate abscisic acid-repressive and auxin-inducible genes under abiotic stress conditions. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 742–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Y.; Chao, D.Y.; Gao, J.P.; Zhu, M.Z.; Shi, M.; Lin, H.X. A previously unknown zinc finger protein, DST, regulates drought and salt tolerance in rice via stomatal aperture control. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lan, H.; Shao, Q.; Wang, R.; Chen, H.; Tang, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, J. An A20/AN1-type zinc finger protein modulates gibberellins and abscisic acid contents and increases sensitivity to abiotic stress in rice (Oryza sativa). J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.H.; Jiang, H.W.; Hsieh, E.J.; Chen, H.Y.; Chien, C.T.; Hsieh, H.L.; Lin, T.P. Drought and salt stress tolerance of an Arabidopsis glutathione S-transferase U17 knockout mutant are attributed to the combined effect of glutathione and abscisic acid. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Shen, X.; Guo, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Cheng, T.; Wen, H.; et al. RNA-Seq-Based WGCNA and Association Analysis Reveal the Key Regulatory Module and Genes Responding to Salt Stress in Wheat Roots. Plants 2024, 13, 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13020274

Chen J, Zhang L, Liu Y, Shen X, Guo Y, Ma X, Zhang X, Li X, Cheng T, Wen H, et al. RNA-Seq-Based WGCNA and Association Analysis Reveal the Key Regulatory Module and Genes Responding to Salt Stress in Wheat Roots. Plants. 2024; 13(2):274. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13020274

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jiating, Lei Zhang, Yingxi Liu, Xinyao Shen, Yujing Guo, Xiaofei Ma, Xiaojun Zhang, Xin Li, Tianling Cheng, Huiqin Wen, and et al. 2024. "RNA-Seq-Based WGCNA and Association Analysis Reveal the Key Regulatory Module and Genes Responding to Salt Stress in Wheat Roots" Plants 13, no. 2: 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13020274