Phytotoxicity, Morphological, and Metabolic Effects of the Sesquiterpenoid Nerolidol on Arabidopsis thaliana Seedling Roots

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Root Bioassays in Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0

2.2. Quantification of Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA)

2.3. In-Situ Semi-Quantitative Detection of H2O2

2.4. Quantification of Total Soluble Proteins, Lipid Peroxidation (Malondialdehyde, MDA), Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) and Catalase (CAT) Activities

2.5. Metabolite Extraction and Derivatization for GC-MS Based Untargeted Metabolomics

2.6. Analyses of GC-MS Metabolomics Data

2.7. Statistical Analyses

2.7.1. Statistical Assessment of Morpho-Physiological Parameters

2.7.2. Metabolomic Data Analysis

2.8. Raw Data Sharing

3. Results

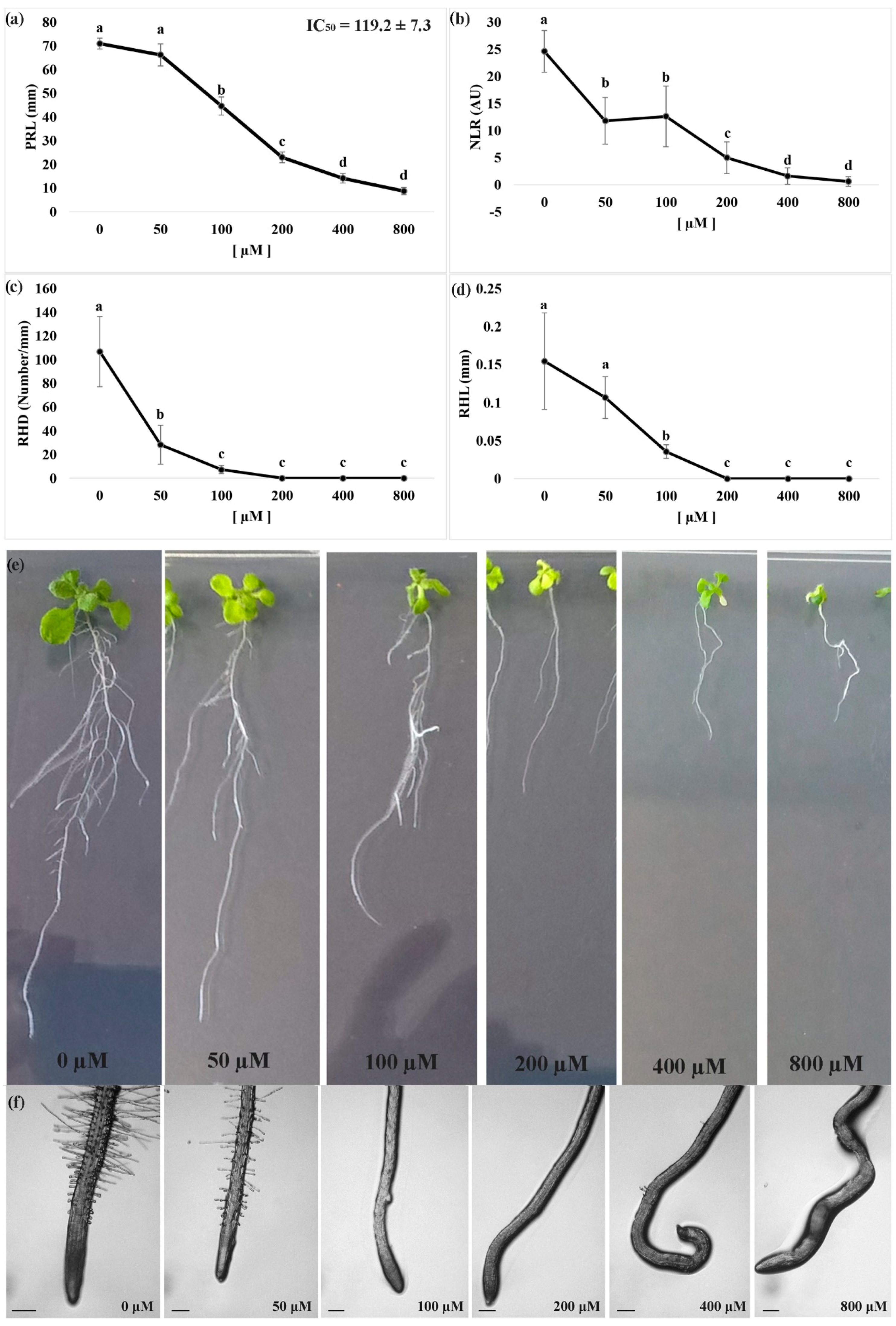

3.1. Dose-Response Curves to Measure the Effects of Nerolidol on Root Morphology

3.2. IAA Quantification and Morphological Malformations in Roots

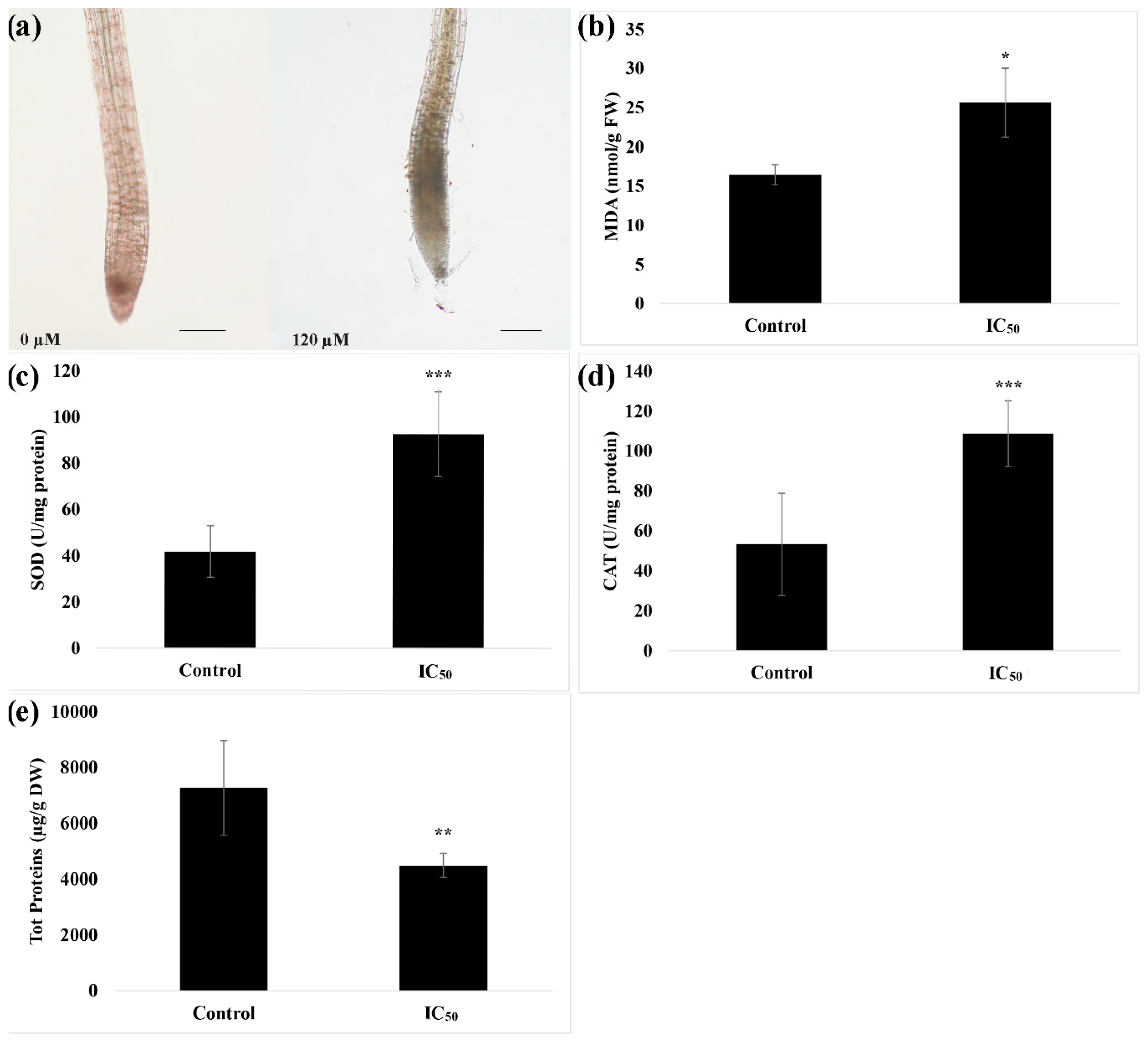

3.3. In-Situ Semi-Quantitative Detection of H2O2

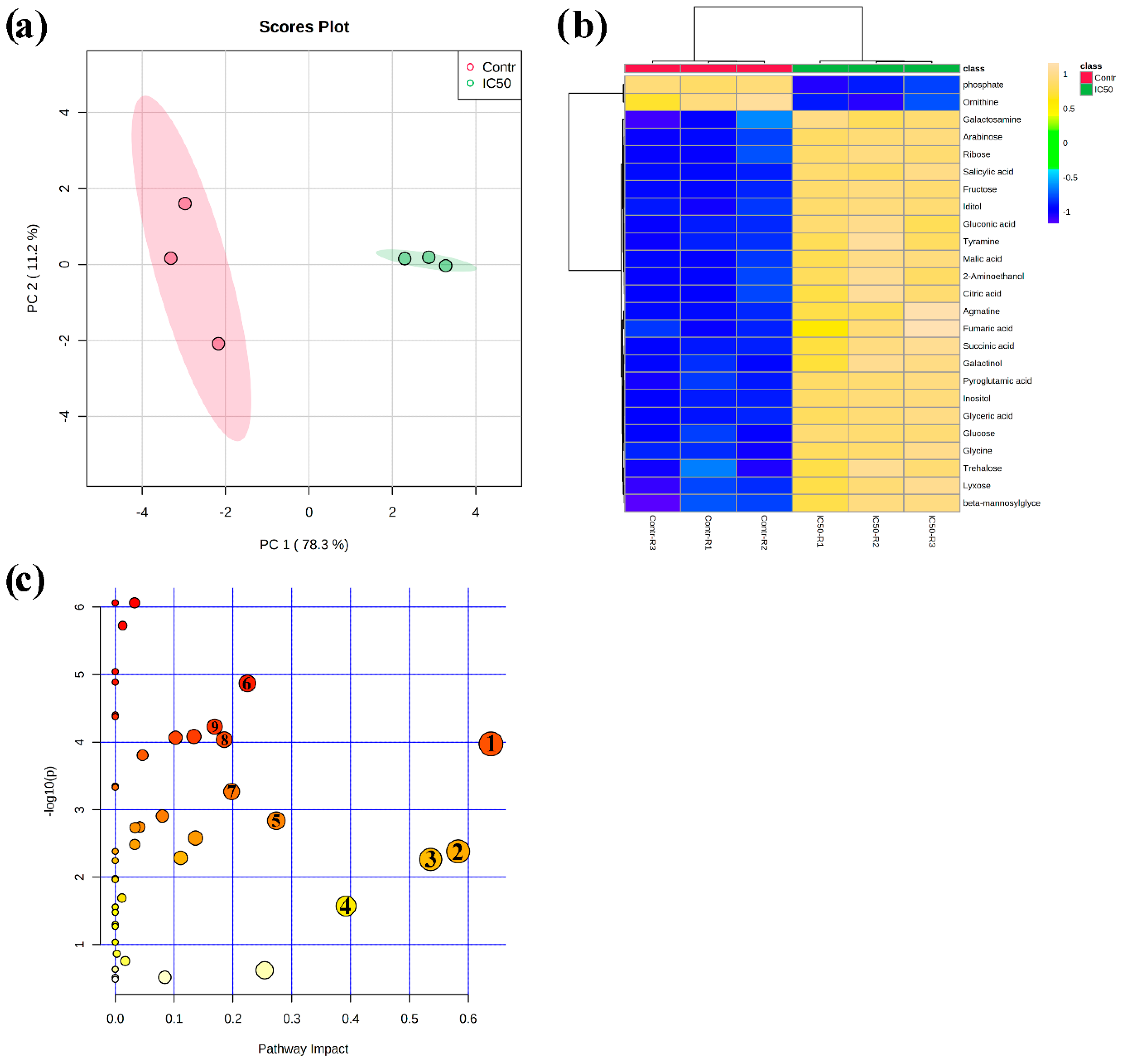

3.4. Metabolome-Wide Changes Induced by Nerolidol in A. thaliana Roots

| Metabolites | FC: Control/IC50 | p-Value (t-Test) | Biochemical Classes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine | 0.56342 | 0.033117 | Amino acids |

| Allothreonine | 0.5902 | 0.026942 | |

| Asparagine | 0.1398 | 0.004414 | |

| GABA | 0.19963 | 0.023587 | |

| Glutamic acid | 0.29068 | 0.000466 | |

| Glycine | 0.28728 | 1.30 × 10−5 | |

| Leucine | 0.59679 | 0.027607 | |

| Serine | 0.35456 | 0.011955 | |

| Cadaverine | 0.56438 | 0.010415 | Polyamines |

| Ornithine | 1.8154 | 0.000209 | |

| N-acetylornithine | 0.88723 | 0.001882 | |

| Putrescine | 0.56552 | 0.010855 | |

| Tyramine | 0.59957 | 4.16 × 10−5 | Amine |

| Agmatine | 0.54233 | 0.000113 | |

| O-Phosphoethanolamine | 0.26807 | 0.000623 | |

| Citric acid | 0.7364 | 6.54 × 10−5 | Organic acids |

| Fumaric acid | 0.57442 | 0.000446 | |

| Gluconic acid | 0.54372 | 1.08 × 10−5 | |

| Glyceric acid | 0.33833 | 3.78 × 10−6 | |

| Malic acid | 0.64095 | 1.78 × 10−5 | |

| Succinic acid | 0.58541 | 3.95 × 10−5 | |

| Threonic acid | 0.7115 | 0.001414 | |

| Arabinose | 0.5631 | 8.03 × 10−6 | Sugars |

| Fructose | 0.45831 | 4.50 × 10−7 | |

| Glucose | 0.45976 | 4.62 × 10−6 | |

| Lyxose | 0.57485 | 0.000108 | |

| Maltose | 0.55043 | 0.000644 | |

| Ribose | 0.61642 | 2.20 × 10−5 | |

| Trehalose | 0.47397 | 0.000268 | |

| Glucose 6-phosphate | 0.4793 | 0.005374 | |

| Galactinol | 0.30915 | 4.91 × 10−5 | Sugar alcohols |

| Iditol | 0.48601 | 5.64 × 10−6 | |

| Inositol | 0.24637 | 8.68 × 10−7 | |

| Maltitol | 0.64358 | 0.000988 | |

| meso-Erythritol | 0.82828 | 0.021309 | |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaric acid | 0.51926 | 0.000691 | Organic acids |

| 6-Aminohexanoic Acid | 0.76983 | 0.003172 | |

| beta-Mannosylglycerate | 0.57697 | 0.000237 | |

| Dehydroascorbic acid | 0.86524 | 0.000852 | |

| Palmitate | 1.3282 | 0.010824 | |

| Pyroglutamic acid | 0.6296 | 1.03 × 10−5 | |

| Phosphoric acid | 2.2766 | 2.08 × 10−5 | |

| Salicylic acid | 0.4143 | 1.61 × 10−6 | |

| Shikimic acid | 0.75721 | 0.001238 | |

| Sinapinic acid | 0.42289 | 0.001801 | |

| 2-Aminoethanol | 0.50229 | 3.40 × 10−5 | Miscellaneous |

| Galactosamine | 0.85845 | 0.00027 | |

| Glycero3-galactoside | 0.68749 | 0.00415 |

| Pathways | Total Compounds | Coverage | −log10(p) | FDR | Pathway Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch and sucrose metabolism (1) | 22 | 5 | 3.976 | 0.000406 | 0.63853 |

| Alanine aspartate and glutamate metabolism (2) | 22 | 7 | 2.3819 | 0.007982 | 0.58274 |

| Glycine serine and threonine metabolism (3) | 33 | 6 | 2.2637 | 0.00973 | 0.53598 |

| Arginine biosynthesis (4) | 18 | 6 | 1.5727 | 0.037307 | 0.39224 |

| Arginine and proline metabolism (5) | 34 | 4 | 2.8369 | 0.003639 | 0.27366 |

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism (6) | 29 | 7 | 4.8696 | 0.000113 | 0.22451 |

| Galactose metabolism (7) | 27 | 6 | 3.2689 | 0.001584 | 0.1978 |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) (8) | 20 | 3 | 4.0384 | 0.000381 | 0.18531 |

| Tyrosine metabolism (9) | 16 | 2 | 4.2311 | 0.000326 | 0.16892 |

| Butanoate metabolism | 17 | 3 | 2.5801 | 0.005717 | 0.13636 |

| Glutathione metabolism | 26 | 4 | 4.0848 | 0.000381 | 0.13362 |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | 46 | 8 | 2.285 | 0.009608 | 0.11111 |

| Inositol phosphate metabolism | 28 | 2 | 4.0674 | 0.000381 | 0.10251 |

| Phenylalanine tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis | 22 | 1 | 2.9072 | 0.003258 | 0.08008 |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 37 | 3 | 3.0159 | 0.002678 | 0.06525 |

| Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 46 | 1 | 2.7444 | 0.004173 | 0.0416 |

| Sphingolipid metabolism | 17 | 2 | 2.7361 | 0.004173 | 0.03365 |

| Sulphur metabolism | 15 | 2 | 2.485 | 0.006819 | 0.03315 |

| Phosphatidylinositol signalling system | 26 | 1 | 6.0615 | 2.17 × 10−5 | 0.03285 |

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 50 | 2 | 5.7243 | 3.14 × 10−5 | 0.0125 |

| Fatty acid biosynthesis | 56 | 3 | 1.6915 | 0.02992 | 0.01123 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Nerolidol Induced Root Morphological Alterations in a Dose-Dependent Manner That Involves IAA and ROS

4.2. Nerolidol Regulated Primary Metabolic Pathways to Divert Energy for Stress Tolerance

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oerke, E. Crop losses to pests. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, S. Integrated weed management (IWM): Why are farmers reluctant to adopt non-chemical alternatives to herbicides? Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranel, P.J.; Wright, T.R. Resistance of weeds to ALS-inhibiting herbicides: What have we learned? Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallett, K. Herbicide target sites: Recent trends and new challenges. In Proceedings of the Brighton Crop Protection Conference Weeds; British Crop Protection Council: Alton, UK, 1997; Volume 2, pp. 575–578. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, B.P.; Tranel, P.J. Target-site mutations conferring herbicide resistance. Plants 2019, 8, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallett, K. Can we expect new herbicides with novel modes of action in the foreseeable future? Outlooks Pest Manag. 2016, 27, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cole, D.; Pallett, K.; Rodgers, M. Discovering new modes of action for herbicides and the impact of genomics. Pestic. Outlook 2000, 11, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, N.; Abbas, T.; Tanveer, A.; Jabran, K. Allelopathy for weed management. In Co-Evolution of Secondary Metabolites; Spring: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 505–519. [Google Scholar]

- Araniti, F.; Marrelli, M.; Lupini, A.; Mercati, F.; Statti, G.A.; Abenavoli, M.R. Phytotoxic activity of Cachrys pungens Jan, a mediterranean species: Separation, identification and quantification of potential allelochemicals. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2014, 36, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araniti, F.; Lupini, A.; Sorgonà, A.; Statti, G.A.; Abenavoli, M.R. Phytotoxic activity of foliar volatiles and essential oils of Calamintha nepeta (L.) Savi. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhler, D.D. 50th Anniversary—Invited Article: Challenges and opportunities for integrated weed management. Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavo, A.; Mauromicale, G. Integrated weed management in herbaceous field crops. Agronomy 2020, 10, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, S.O.; Owens, D.K.; Dayan, F.E. Natural product-based chemical herbicides. In Weed Control: Sustainability, Hazards, and Risks in Cropping Systems Worldwide; Korres, N.E., Burgos, N.R., Duke, S.O., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Araniti, F.; Grana, E.; Krasuska, U.; Bogatek, R.; Reigosa, M.J.; Abenavoli, M.R.; Sanchez-Moreiras, A.M. Loss of gravitropism in farnesene-treated arabidopsis is due to microtubule malformations related to hormonal and ROS unbalance. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araniti, F.; Bruno, L.; Sunseri, F.; Pacenza, M.; Forgione, I.; Bitonti, M.B.; Abenavoli, M.R. The allelochemical farnesene affects Arabidopsis thaliana root meristem altering auxin distribution. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 121, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araniti, F.; Costas-Gil, A.; Cabeiras-Freijanes, L.; Lupini, A.; Sunseri, F.; Reigosa, M.J.; Abenavoli, M.R.; Sánchez-Moreiras, A.M. Rosmarinic acid induces programmed cell death in Arabidopsis seedlings through reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial dysfunction. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araniti, F.; Miras-Moreno, B.; Lucini, L.; Landi, M.; Abenavoli, M.R. Metabolomic, proteomic and physiological insights into the potential mode of action of thymol, a phytotoxic natural monoterpenoid phenol. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 153, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, S.O.; Dayan, F.E. Discovery of new herbicide modes of action with natural phytotoxins. In Discovery and Synthesis of Crop Protection Products; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, S.O.; Romagni, J.G.; Dayan, F.E. Natural products as sources for new mechanisms of herbicidal action. Crop Prot. 2000, 19, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.-K.; Tan, L.T.-H.; Chan, K.-G.; Lee, L.-H.; Goh, B.-H. Nerolidol: A sesquiterpene alcohol with multi-faceted pharmacological and biological activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.Y.; Rodriguez, A.A.M.; Vega, D.S.M.; Sussmann, R.A.; Kimura, E.A.; Katzin, A.M. Antimalarial activity of the terpene nerolidol. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 48, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceole, L.F.; Cardoso, M.D.G.; Soares, M.J. Nerolidol, the main constituent of Piper aduncum essential oil, has anti-Leishmania braziliensis activity. Parasitology 2017, 144, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araniti, F.; Sánchez-Moreiras, A.M.; Graña, E.; Reigosa, M.J.; Abenavoli, M.R. Terpenoid trans-caryophyllene inhibits weed germination and induces plant water status alteration and oxidative damage in adult Arabidopsis. Plant Biol. 2017, 19, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, S.; Cioni, P.; Flamini, G.; Pardossi, A. Weeds for weed control: Asteraceae essential oils as natural herbicides. Weed Res. 2017, 57, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araniti, F.; Lupini, A.; Mauceri, A.; Zumbo, A.; Sunseri, F.; Abenavoli, M.R. The allelochemical trans-cinnamic acid stimulates salicylic acid production and galactose pathway in maize leaves: A potential mechanism of stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 128, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araniti, F.; Scognamiglio, M.; Chambery, A.; Russo, R.; Esposito, A.; D’Abrosca, B.; Fiorentino, A.; Lupini, A.; Sunseri, F.; Abenavoli, M.R. Highlighting the effects of coumarin on adult plants of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. by an integrated-omic approach. J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 213, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, B.B.; Das, V.; Landi, M.; Abenavoli, M.; Araniti, F. Short-term effects of the allelochemical umbelliferone on Triticum durum L. metabolism through GC-MS based untargeted metabolomics. Plant Sci. 2020, 298, 110548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araniti, F.; Graña, E.; Reigosa, M.J.; Sánchez-Moreiras, A.M.; Abenavoli, M.R. Individual and joint activity of terpenoids, isolated from Calamintha nepeta extract, on Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 2297–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlinson, C.; Kamphuis, L.G.; Gummer, J.P.; Singh, K.B.; Trengove, R.D. A rapid method for profiling of volatile and semi-volatile phytohormones using methyl chloroformate derivatisation and GC–MS. Metabolomics 2015, 11, 1922–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araniti, F.; Lupini, A.; Sunseri, F.; Abenavoli, M.R. Allelopatic potential of Dittrichia viscosa (L.) W. Greuter mediated by VOCs: A physiological and metabolomic approach. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Cajka, T.; Kind, T.; Ma, Y.; Higgins, B.; Ikeda, K.; Kanazawa, M.; VanderGheynst, J.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. MS-DIAL: Data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopka, J.; Schauer, N.; Krueger, S.; Birkemeyer, C.; Usadel, B.; Bergmüller, E.; Dörmann, P.; Weckwerth, W.; Gibon, Y.; Stitt, M. GMD@ CSB. DB: The Golm metabolome database. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 1635–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horai, H.; Arita, M.; Kanaya, S.; Nihei, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Suwa, K.; Ojima, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Tanaka, S.; Aoshima, K. MassBank: A public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 45, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, L.W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M.H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C.A.; Fan, T.W.-M.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis. Metabolomics 2007, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belz, R.G.; Hurle, K.; Duke, S.O. Dose-response—A challenge for allelopathy? Nonlinearity Biol. Toxicol. Med. 2005, 3, nonlin.003.002.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J.; Soufan, O.; Li, C.; Caraus, I.; Li, S.; Bourque, G.; Wishart, D.S.; Xia, J. MetaboAnalyst 4.0: Towards more transparent and integrative metabolomics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W486–W494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reich, M.; Liefeld, T.; Gould, J.; Lerner, J.; Tamayo, P.; Mesirov, J.P. GenePattern 2.0. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 500–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araniti, F.; Mancuso, R.; Lupini, A.; Giofrè, S.V.; Sunseri, F.; Gabriele, B.; Abenavoli, M.R. Phytotoxic potential and biological activity of three synthetic coumarin derivatives as new natural-like herbicides. Molecules 2015, 20, 17883–17902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araniti, F.; Mancuso, R.; Lupini, A.; Sunseri, F.; Abenavoli, M.R.; Gabriele, B. Benzofuran-2-acetic esters as a new class of natural-like herbicides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graña, E.; Sotelo, T.; Díaz-Tielas, C.; Araniti, F.; Krasuska, U.; Bogatek, R.; Reigosa, M.J.; Sánchez-Moreiras, A.M. Citral induces auxin and ethylene-mediated malformations and arrests cell division in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. J. Chem. Ecol. 2013, 39, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gruber, M.Y.; Hegedus, D.D.; Lydiate, D.J.; Gao, M.-J. Effects of a coumarin derivative, 4-methylumbelliferone, on seed germination and seedling establishment in Arabidopsis. J. Chem. Ecol. 2011, 37, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Puertas, M.; McCarthy, I.; Gómez, M.; Sandalio, L.; Corpas, F.; Del Rio, L.; Palma, J. Reactive oxygen species-mediated enzymatic systems involved in the oxidative action of 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Plant Cell Environ. 2004, 27, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liptáková, L.u.; Bočová, B.; Huttová, J.; Mistrík, I.; Tamás, L. Superoxide production induced by short-term exposure of barley roots to cadmium, auxin, alloxan and sodium dodecyl sulfate. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 2189–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causin, H.F.; Roqueiro, G.; Petrillo, E.; Láinez, V.; Pena, L.B.; Marchetti, C.F.; Gallego, S.M.; Maldonado, S.I. The control of root growth by reactive oxygen species in Salix nigra Marsh. seedlings. Plant Sci. 2012, 183, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunand, C.; Crèvecoeur, M.; Penel, C. Distribution of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in Arabidopsis root and their influence on root development: Possible interaction with peroxidases. New Phytol. 2007, 174, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasternak, T.; Potters, G.; Caubergs, R.; Jansen, M.A. Complementary interactions between oxidative stress and auxins control plant growth responses at plant, organ, and cellular level. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 1991–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladimirov, Y.A.; Olenev, V.; Suslova, T.; Cheremisina, Z. Lipid peroxidation in mitochondrial membrane. In Advances in Lipid Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1980; Volume 17, pp. 173–249. [Google Scholar]

- Arpagaus, S.; Rawyler, A.; Braendle, R. Occurrence and characteristics of the mitochondrial permeability transition in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 1780–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Jander, G. Abscisic acid-regulated protein degradation causes osmotic stress-induced accumulation of branched-chain amino acids in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 2017, 246, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, W.L.; Tohge, T.; Ishizaki, K.; Leaver, C.J.; Fernie, A.R. Protein degradation–an alternative respiratory substrate for stressed plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dat, J.; Vandenabeele, S.; Vranova, E.; Van Montagu, M.; Inzé, D.; Van Breusegem, F. Dual action of the active oxygen species during plant stress responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2000, 57, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R.; Vanderauwera, S.; Gollery, M.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen gene network of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.S.; Singh, M.; Aggrawal, P.; Laxmi, A. Glucose and auxin signaling interaction in controlling Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings root growth and development. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairanen, I.; Novák, O.; Pěnčík, A.; Ikeda, Y.; Jones, B.; Sandberg, G.; Ljung, K. Soluble carbohydrates regulate auxin biosynthesis via PIF proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 4907–4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, S.; Rivoal, J. Consequences of oxidative stress on plant glycolytic and respiratory metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, V. Role of amino acids in plant responses to stresses. Biol. Plant. 2002, 45, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlešáková, K.; Ugena, L.; Spíchal, L.; Doležal, K.; De Diego, N. Phytohormones and polyamines regulate plant stress responses by altering GABA pathway. New Biotechnol. 2019, 48, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, F.; Yusuf, M.; Faizan, M.; Faraz, A.; Hayat, S. Role of sugars under abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 109, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, P.; Kamble, N.U.; Majee, M. Stress-inducible galactinol synthase of chickpea (CaGolS) is implicated in heat and oxidative stress tolerance through reducing stress-induced excessive reactive oxygen species accumulation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, M.; Skórzyńska-Polit, E.; Tukiendorf, A. Organic acids accumulation and antioxidant enzyme activities in Thlaspi caerulescens under Zn and Cd stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2006, 48, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairam, R.; Tyagi, A. Physiology and molecular biology of salinity stress tolerance in plants. Curr. Sci. 2004, 86, 407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, P.D.; Cress, W.A.; Van Staden, J. Dissecting the roles of osmolyte accumulation during stress. Plant Cell Environ. 1998, 21, 535–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, A.; Murata, N. The role of glycine betaine in the protection of plants from stress: Clues from transgenic plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, F.; Akram, N.A.; Ashraf, M. Osmoprotection in plants under abiotic stresses: New insights into a classical phenomenon. Planta 2020, 251, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Gautam, A.; Dubey, A.K.; Ranjan, R.; Pandey, A.; Kumari, B.; Singh, G.; Mandotra, S.; Chauhan, P.S.; Srikrishna, S. GABA mediated reduction of arsenite toxicity in rice seedling through modulation of fatty acids, stress responsive amino acids and polyamines biosynthesis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 173, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraire-Velázquez, S.; Balderas-Hernández, V.E. Abiotic stress in plants and metabolic responses. In Abiotic Stress—Plant Responses and Applications in Agriculture; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa, A.; Yabuta, Y.; Shigeoka, S. Galactinol and raffinose constitute a novel function to protect plants from oxidative damage. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouche, N.; Fromm, H. GABA in plants: Just a metabolite? Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnersley, A.M.; Turano, F.J. Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) and plant responses to stress. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2000, 19, 479–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, F.C.; Thompson, J.F.; Dent, C.E. γ-Aminobutyric acid: A constituent of the potato tuber? Science 1949, 110, 439–440. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, H. GABA signaling in plants: Targeting the missing pieces of the puzzle. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, eraa358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bor, M.; Turkan, I. Is there a room for GABA in ROS and RNS signalling? Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 161, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifikalhor, M.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Hassani, B.; Niknam, V.; Lastochkina, O. Diverse role of γ-aminobutyric acid in dynamic plant cell responses. Plant Cell Rep. 2019, 38, 847–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, A.G.; Zaplachinski, S.T. The effects of drought stress on free amino acid accumulation and protein synthesis in Brassica napus. Physiol. Plant. 1994, 90, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi-Abriz, S.; Ghassemi-Golezani, K. Improving amino acid composition of soybean under salt stress by salicylic acid and jasmonic acid. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2016, 89, 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, T.T.; Xu, H.H.; Zhang, K.X.; Guo, T.T.; Lu, Y.T. Glucose inhibits root meristem growth via ABA INSENSITIVE 5, which represses PIN1 accumulation and auxin activity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Dubey, R. Excess nickel modulates activities of carbohydrate metabolizing enzymes and induces accumulation of sugars by upregulating acid invertase and sucrose synthase in rice seedlings. Biometals 2013, 26, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couée, I.; Sulmon, C.; Gouesbet, G.; El Amrani, A. Involvement of soluble sugars in reactive oxygen species balance and responses to oxidative stress in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanović, J.; Mojović, M.; Milosavić, N.; Mitrović, A.; Vučinić, Ž.; Spasojević, I. Role of fructose in the adaptation of plants to cold-induced oxidative stress. Eur. Biophys. J. 2008, 37, 1241–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, H.; Paul, M.; Zu, Y.; Tang, Z. Exogenous trehalose largely alleviates ionic unbalance, ROS burst, and PCD occurrence induced by high salinity in Arabidopsis seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, M.M.; Pereira, J.S.; Maroco, J.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Ricardo, C.P.P.; Osório, M.L.; Carvalho, I.; Faria, T.; Pinheiro, C. How plants cope with water stress in the field? Photosynthesis and growth. Ann. Bot. 2002, 89, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, M.M.; Coelho, D.; Barrote, I.; Correia, M.J. Leaf age effects on photosynthetic activity and sugar accumulation in droughted and rewatered Lupinus albus plants. Funct. Plant Biol. 1998, 25, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, D.W.; Yoder, T.J.; Reiter, W.-D.; Gibson, S.I. Fumaric acid: An overlooked form of fixed carbon in Arabidopsis and other plant species. Planta 2000, 211, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernie, A.R.; Martinoia, E. Malate. Jack of all trades or master of a few? Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tohamy, W.; El-Abagy, H.; Badr, M.; Gruda, N. Drought tolerance and water status of bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) as affected by citric acid application. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2013, 86, 212–216. [Google Scholar]

- Minocha, R.; Majumdar, R.; Minocha, S.C. Polyamines and abiotic stress in plants: A complex relationship1. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yu, J.; Peng, Y.; Huang, B. Metabolic pathways regulated by abscisic acid, salicylic acid and γ-aminobutyric acid in association with improved drought tolerance in creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera). Physiol. Plant. 2017, 159, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Landi, M.; Misra, B.B.; Muto, A.; Bruno, L.; Araniti, F. Phytotoxicity, Morphological, and Metabolic Effects of the Sesquiterpenoid Nerolidol on Arabidopsis thaliana Seedling Roots. Plants 2020, 9, 1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9101347

Landi M, Misra BB, Muto A, Bruno L, Araniti F. Phytotoxicity, Morphological, and Metabolic Effects of the Sesquiterpenoid Nerolidol on Arabidopsis thaliana Seedling Roots. Plants. 2020; 9(10):1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9101347

Chicago/Turabian StyleLandi, Marco, Biswapriya Biswavas Misra, Antonella Muto, Leonardo Bruno, and Fabrizio Araniti. 2020. "Phytotoxicity, Morphological, and Metabolic Effects of the Sesquiterpenoid Nerolidol on Arabidopsis thaliana Seedling Roots" Plants 9, no. 10: 1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9101347

APA StyleLandi, M., Misra, B. B., Muto, A., Bruno, L., & Araniti, F. (2020). Phytotoxicity, Morphological, and Metabolic Effects of the Sesquiterpenoid Nerolidol on Arabidopsis thaliana Seedling Roots. Plants, 9(10), 1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9101347