1. Introduction

How do the resemblances of dialects relate to the distances between the places they are spoken? Do they have the same nature apart from the difference in location? Are there differences in this respect between lexicon and grammar?

This study analyzes the relationships between the resemblances of dialects and the distances between them using various dialectological atlases. Their relationships show similar characteristics in most places, excepting a few regions. The figures for the relationships appearing on the graphs differ by linguistic class and the width of the investigating area. In this paper, I show the common and peculiar characteristics of dialectal distributions.

2. Data Sources and Materials

This analysis investigates various data on correspondences and valid data in setting reference places and comparison places.

The Linguistic Atlas of Japan (LAJ:

NLRI 1966–1974) and the Grammar Atlas of Japanese Dialects (GAJ:

NLRI 1989–2006) are used for data over a wide area, and the Kamiina-no Hogen (

Mase 1980) is used for data over a narrow area.

The LAJ consists of six volumes including 300 maps that were published between 1966 and 1974; the data of the LAJ were collected between 1957 and 1965 at 2400 locations, and most items are lexical.

The GAJ consists of six volumes including 350 maps that were published between 1989 and 2006; the data of the GAJ were collected between 1979 and 1982 at 807 locations, and all items are grammatical.

The Kamiina-no Hogen (

Mase 1980), including 284 maps, was published in 1980; the data were collected between 1968 and 1974 at 240 locations. One hundred and ten lexical, 12 grammatical, and five phonological items are selected for this study.

3. Methods

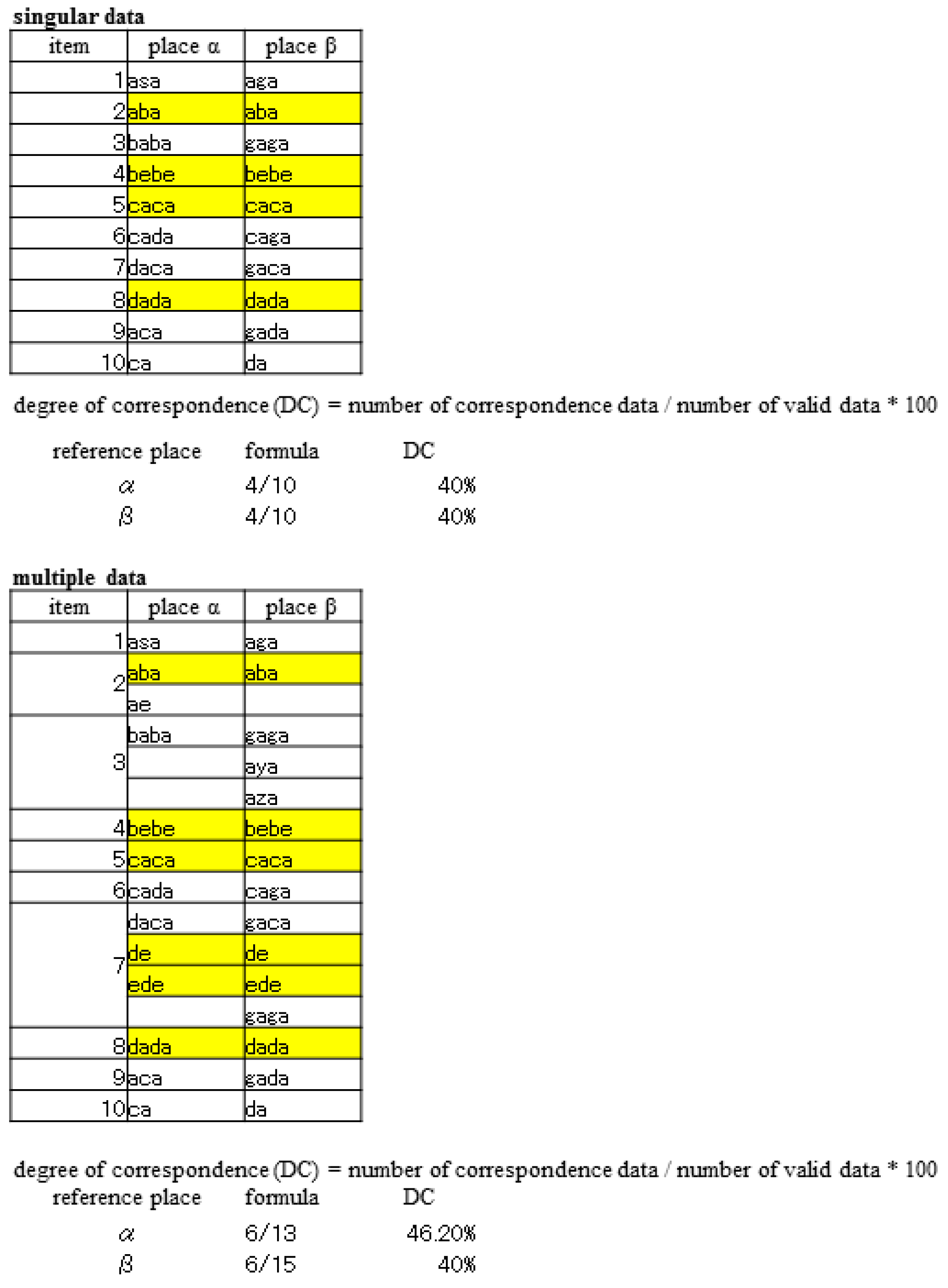

The degree of correspondence (DC) can be calculated to quantify the degree of resemblance between two sets of dialect data. DCs are the ratios of the number of correspondences in the data for each reference place matching those of the comparison place to the total number of correspondences compared.

Setting the reference and comparison data side by side, it is possible to calculate the DC with from the number of pieces of correspondence data and the number of pieces of valid data.

Valid data are data excluding data invalidated for comparison, such as NR (no response) and “others” in a map legend.

The DC is calculated with the following formula, and it is expressed as a percentage:

DC = number of correspondence data / number of valid data * 100.

DCs can be found after fixing a reference place. The comparison places are all the places in an atlas. The DC is calculated for each comparison place based on the fixed reference place.

When the data for both places are singular (one response), the results are the same regardless of which location is taken as the reference place, as shown in the upper example in

Figure 1. However, the results are different in the case of multiple data (multiple responses), as in the lower example in

Figure 1. In general, the figures differ since dialectal distribution data are never constructed entirely of singular data.

I adopt the great-circular distance for the distance between the reference and comparison places. The distances between the comparison places and the fixed reference place were obtained with the web system of the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI, formerly the Geographical Survey Institute).

It is possible to make graphs of the data with distances and DCs along the X and Y axes, respectively.

I selected 18 places as reference places, reflecting the traditional division into 16 dialects and two historical capitals (Kyoto and Tokyo); all of them are common to the LAJ and GAJ, from which the wide-area data of this study were collected (

Figure 2).

On the other hand, eight places were selected for narrow-area data (

Figure 3).

4. The Main Sequence

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 are based on a reference place in the Tohoku region. The DC shows an inverse relationship with distance in most places.

The inverse relationships are frequently confirmed, even if the reference places or atlases are changed, as in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 with reference places in Tokaitosan.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the same inverse relationships when the reference place is in Chugoku. Thus, this feature is referred to as the main sequence in this study.

Kumagai (

2016) referred to the feature obtained using data from the LAJ based not on degrees and graphs but on real numbers and maps. The relationships between DC and distance confirm those results. The general pattern in the main sequence, that is, the first result, is called the NS-FD law (near-similar, far-different).

On the other hand, peaks from exceptional places can be seen in the figures above (

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), in addition to the general pattern. This peculiar feature is treated in the next section.

5. Peculiar Groups

Two types of peculiar groups are found. Their characteristics are different. It would appear that one type is based on the history of the place and the other on geographical features.

5.1. In-Migration Place

The first type is a peak indicating a group mentioned in

Section 4. Classifying the comparison places of the graphs above, it is found that the locations of the peaks are on Hokkaido, as in the graphs of Tokaitosan (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11) and the graphs of Chugoku (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

Hokkaido is an in-migration place; standardization progresses well in Hokkaido. Standard Japanese is based on Tokyo in the Kanto district. The data indicate that Hokkaido speech behaves as a Kanto dialect regardless of distance and position.

The peculiar feature of the peaks for Hokkaido in the graphs was caused by in-migration. Therefore, with the reference place set in Hokkaido, intriguing graphs appear as in

Figure 16 and

Figure 17.

5.2. Ryukyu Islands

Another peculiar group is found on the Ryukyu Islands, with narrow land areas divided by the sea.

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 set the reference place on Okinawa Island. The NS-FD law holds only within 500 km. It is difficult to find a relationship between DC and distance beyond 500 km (outside of the Ryukyu dialect area). The NS-FD law holds in a main divisional dialect group located on a broad land area, and it becomes ambiguous in solitary islands because of the narrowness of the land area.

6. Differences in the Shape of the Graph between Wide and Narrow Areas

The main sequence shows a precise linear relationship over a narrow area, as in

Figure 20. The graph of the main sequence over a wide area shows a triangular form as in the figures above (e.g.,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 of the same dialectal division).

Classifying the comparison places in the local district resolves the narrow data into multiple lines (

Figure 21). We may suppose that the triangle of the main sequence over a wide area is composed of a large number of such lines.

7. Difference in the Relationships of Grammatical and Lexical Data between Wide and Narrow Areas

Comparing the grammatical and lexical data for a wide area, the lexical data of the LAJ show a wider range and higher DC than the grammatical data of the GAJ for a wide area, as in

Figure 22.

On the other hand, the relationship is different for a narrow area. Grammatical data show a higher DC than lexical data for a narrow area, as in

Figure 23.

The grammatical data do not vary over a narrow communicative area, since grammar is a core feature of language. If grammar was so diverse, it would be difficult to communicate with each other in a small village. However, despite the similarity of grammar in a narrow area, grammar is not necessarily common between far areas, since people in those places do not communicate as frequently. The differences between the grammatical and lexical data show the importance of sharing a dialect as a means of communication.

8. Conclusions

DC and distance in dialectal data generally show relationships following the NS-FD law (near-similar, far-different), here called the main sequence.

In-migration places like Hokkaido and narrow land areas divided by the sea like Ryukyu show peculiar graphs different from the main sequence.

Graphs of DC versus distance in narrow areas show distinct lines. The lines differ in comparison districts. The triangular shapes in wide areas appear to also be composed of such lines.

DC is higher for grammar than lexicon over a narrow area, though this relationship is the opposite over a wide area. This appears to reflect the importance of commonalities in grammar for communication in a narrow area.