3. Hypothesis and Design of Variables

With the object of verifying the efficacy of our proposal, during 2018 we contacted several NGOs working with migrant groups under risk of social exclusion in the city of Malaga. We came to the conclusion that Málaga Acoge (Malaga Welcomes You) was the one that fulfilled all the requirements to implement our model:

It had active courses of Spanish as a foreign language.

The students were classified into groups according to their level of knowledge of the Spanish language. The criteria and proposals of ECFR were employed in the evaluation of their idiomatic command of the language.

Every level had a sufficient number of students.

Additionally, there was more than one group for each different level of knowledge of the language.

In a first approximation, we believed it convenient to work with Spanish B1 level students as the course had already started at the beginning of our research. We did not have more than a quarter of them to carry out our experiment and it seemed convenient to put our model into practice at that intermediate level. It was also important to keep a control group which during their learning process, did not receive any stimulus by way of the Proximity lexicon and if it did, the stimulus was not to be given in the systematic and controlled manner required by our research.

Both groups constitute the independent variable of our work and from its design, we were able to build the main hypotheses of the present research:

Hypothesis of personal satisfaction. After the implementation of the didactic model which supports this work, there will be a statistically superior and significative difference in the experimental group in contrast with the control group in its perception of local integration, wellbeing and personal satisfaction.

Hypothesis of integration. Likewise, it is to be expected that the positive perception of vital wellbeing among the individuals which form the experimental group may lead them to formulate plans of possible plans of a future and integration in the host community to a greater degree than the members of the control group.

With the objective of confirming both hypotheses, we carried out an analysis of correlations between dependent and independent variables with the results which are presented in the following chapter. The dependent variables were built on the bases of the answers given by the informants to the items included in the sociological questionnaire of wellbeing (

Appendix A). The results were correlated with the independent variable (group to which the individual belonged: experimental group, Group A; control group, Group B). The idea was to establish a cause-effect relation between the variables under study so that the belonging to each group should justify the level of satisfaction as formulated initially in the hypotheses.

We had a total sample of 40 students. Half of them (N = 20) were offered the learning system which contained the “Food and drink” unit. We chose this unit because of its traditional use in foreign language teaching. In addition, a previous study gave us enough local terms connected with this unit. As we will mention later, it is important a previous study of specific situations to use the proposal model in other didactic units. At the same time, as mentioned, a control group of 20 students was kept to which the model was not applied (Group B), even though the rest of educational process was identical (same learning system, same didactic unit Food and drink). The main difference was the systematic way that the experimental group learnt local lexicon. As obvious, the teachers in the control group could use this lexical forms eventually. The difference was the systematic and conscious way that defines the experimental group.

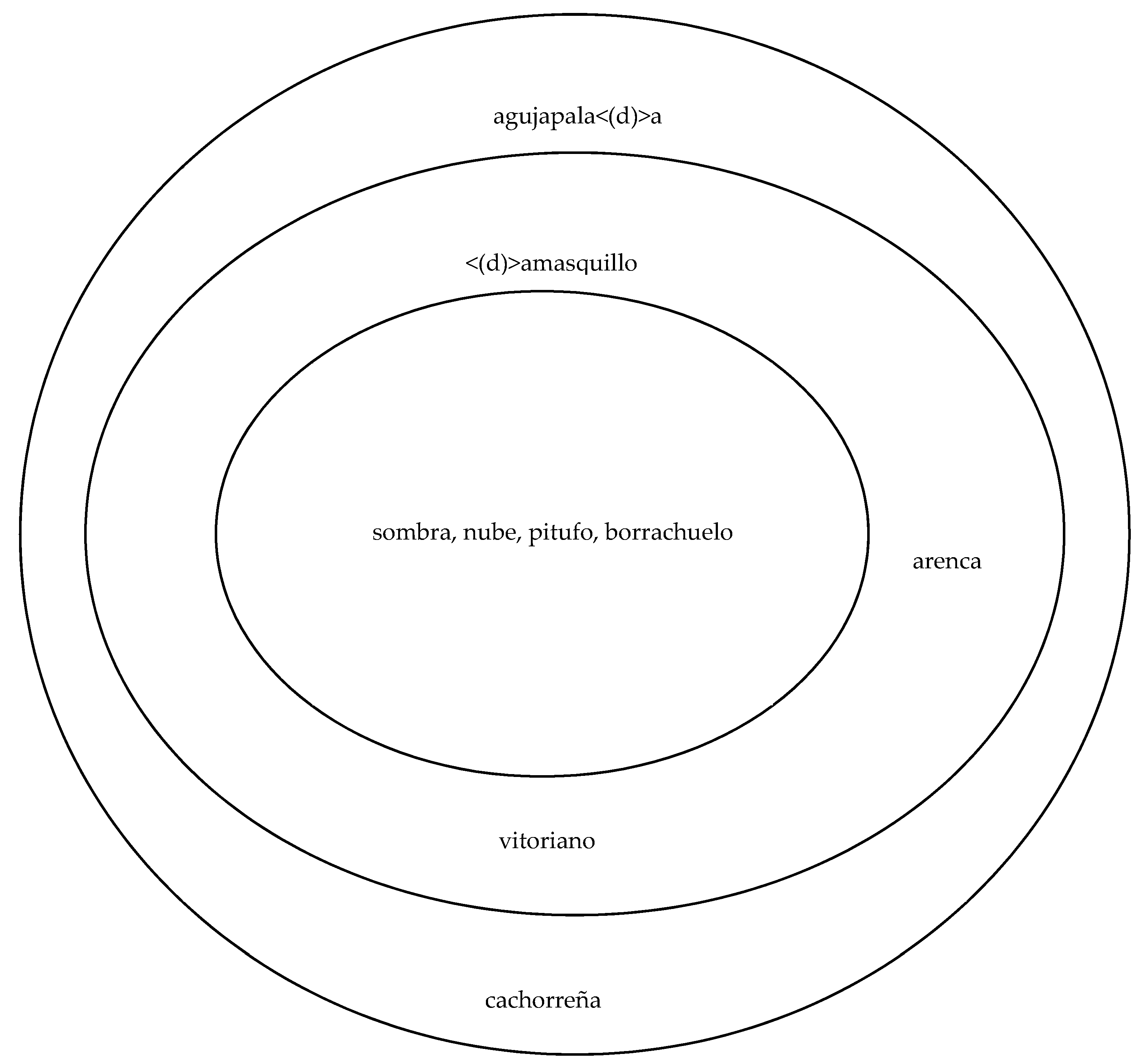

Throughout the last quarter of the course (from March to June 2018), the teachers under contract to the NGO, were asked to apply the proximity-based model to the members of Group A. Naturally, the teachers were previously informed of the nature of the activity and the lexicon model methodology better suited to be implemented with Group A. Furthermore, a group of students who had been previously informed and trained, volunteered as auxiliary instructors during that quarter. The auxiliary group helped to organise workshops and activities related to the selected didactic unit: local cooking workshops, excursions to gastronomic provincial fairs and an end-of-course celebration, where local food and drinks were exchanged. The exchange also included food and drinks from the migrants’ homelands. As mentioned before, the lexical items employed came from the previous study and selection (

Ávila-Muñoz 2017) and were shown in

Table 2.

At the end of the course, the students were asked to fill the wellbeing questionnaire shown as

Appendix A. In the following section comments are given on the more significative results from the analysis of those questionnaires, that were created ad hoc to improve the actual research from previous studies (

Diener et al. 1985;

Atienza et al. 2000;

Pons et al. 2002)

4. Sample

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of ECOPASOS (FFI2015-68171-C5-1-P).

The main social and personal characteristics of our informants are synthesised in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 and provide the description of our sample.

Most of the migrants came from Africa, although in both groups there were people from Asia and only one was from a European country in Group A (

Table 3). The number of males was somewhat higher than that of females, but the imbalance was identical in both groups (M = 12, F = 8).

A recodified version more adjusted to the informants’ educational reality was done based on the data in

Table 4. Thus, the values were reorganised into two variants according to the degree of completion of some educational stages (Level 1, N = 23) or not (Level 0, N = 17). We believe that the reorganisation shown in

Table 5 is a better representation of our informants’ situation than that of

Table 4 and it is more adjusted to the prevalent academic situation in the western world.

Most of the individuals in Group A fit in Level 1 (N = 15), the opposite situation occurring in Group B, since almost all its members belong to educational level 0.

Table 6 shows that most males indicated that their study rank corresponded to Level 1 in our recodification (N = 18), while most females belonged to Level 0 (N = 11).

Most of the members of the sample had arrived to Malaga between a year and less than a year (Group A = 17; Group B = 15) and only one had been more than five years in the city. The rest had been between 1 and 5 years in Malaga (Group A = 3; Group B = 4). Almost all had had very frequent contact with their country (between two or more times every week and every day). Only 2 informants from Group A indicated that they kept very sporadic contact with their country (more than twice monthly). Half of the sample did not answer the questions related to the work they had (Group A = 11; Group B = 9), which made us think they were unemployed or in an illegal situation at the time of the interview. It is relevant to point out that of those who answered those questions, almost all expressed that they were very little/little satisfied with their work and only one person of Group B stated that (s)he was very satisfied with her or his employment situation. Additionally, it was lamentable that 30 of our informants had suffered some racist or xenophobic incidents since the time they arrived in Spain (Group A = 16; Group B = 14), whereas 4 classified such incidents as grave and 26 as Not grave.

Most of the informants indicated that they shared their free time only with people of the same origin or culture (Group A = 13; Group B = 17). However, 6 people from Group A and only 1 from Group B also socialised with Spaniards. Almost none of the migrants belonged to associations or social groups (Group A = 18; Group B = 18) and only 4 participated in associations, which were anyway formed by people of their own origin or culture (Group A = 2; Group B = 2).

As can be appreciated by the data so far, the initial conditions of the members of Groups A and B were very similar, except for their educational level. Nonetheless, their education showed no correlation or a very weak one with the variables we will use further on to measure the wellbeing shown by the migrant towards the population and their host region or area (see below, regression analysis by steps).

5. From Theory to Practice. Does the Model Work?

It is important for the objectives of our work that 9 people from Group A indicated that since they began their study of Spanish, they had fewer integration problems in contrast with only 3 informants who chose the same answer in Group B. This part of our data may turn out to be very significative because until the implementation of the proximity model in March 2018, the learning conditions of both groups were the same: identical language learning procedures in so far as contents, teaching and methods (at any rate, without the systematic employment of the Proximity lexicon as a working tool). In Group B, only 2 people stated they had no integration problems in contrast with 7 who chose the same option in Group A. Likewise, we believe that data in

Table 7 are relevant because we could interpret that the teaching method based on the Proximity lexicon as we propose it, could have some incidence on the social integration ease of the immigrants in the local communities.

Notice how 8 members of Group B did not even look for contacts; no member of Group A chose this option. Besides, the number of people from Group B (N = 6) doubles that of those in Group A (N = 3) who prefer to be with members of the same culture. In Group A, we find 16 people who state they have no integration problems or that they have been reduced since they study Spanish (options 0 + 1, N = 16) in contrast with only 5 in Group B.

When we analyse the answers referring to students´ integration with Malaga values and customs, the answers pointed in the same direction as shown in

Table 8.

By adding the answers to None and Very little we observe that 9 people belong to Group B and only 3 to Group A (besides, in this group, nobody chose the option None). Additionally, 6 members of Group A indicated that they were between Enough and Quite a lot integrated in the Malaga society and only 1 person from Group B agreed with that position.

With regard to the migrants´ intentions in the short and the medium term, the data again consolidate the tendencies indicated: the members of Group A are the ones who in the majority consider, as a probable option, to remain in Malaga both in the short term (less than 5 years: Group A = 6; Group B = 1) as well as in the medium one (more than 5 years: Group A = 5; Group B = 0). Nevertheless, the truth is that most of the migrants we have studied, either do not know what they will do in the short/medium term or have in mind to go to some other countries.

We have left for the end of our analysis some of the items which in our opinion, will be the most useful in the evaluation of the efficacy of the proposed teaching model based on the proximity lexicon as a social integrational tool. We are referring to the gradation migrants make of (A) their feelings towards the assertions shown in items 39–41 of our questionnaire (

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11) and (B) their level of wellbeing in Malaga (

Table 12, item 42 of the questionnaire). To evaluate these 4 items, the informants had to place them in a continuous scale from less to more (0–6).

The only grade 3 evaluations shown in

Table 9 belong to Group A subjects (N = 5); notice that 16 people from Group B chose the lower levels of the scale (grades 0 and 1) in contrast to 7 of Group A. Additionally, only 4 people from Group B chose option 2, which was half of those in Group A (N = 8).

The media analysis shows a weak signification index, although with an Eta

2 of low intensity (

Table 10).

The Mann–Whitney test was applied for differences of means in independent samples

| Measures of Association | Eta | Eta2 |

| Group * Positive Evaluation of life in Malaga | 0.506 | 0.256 |

Similar tendencies are observed when analysing the data from the evaluation of life conditions in Malaga (

Table 11). Nevertheless, on this occasion, the values of the means and the measures of association are very significative (

Table 12). It calls our attention that all members of Group B chose the lowest proposed grades (N = 20, grades 0 and 1). Only 6 people from Group A opted for the same levels, in contrast with the 14, who chose 2 or 3.

The Mann–Whitney test was applied for mean differences in independent samples

| Measures of Association | Eta | Eta2 |

| Group * Sentence2 | 0.789 | 0.622 |

To think of moving dear relatives to a new country to start a new life is a very difficult decision, which requires a high degree of certainty and determination. However, as can be observed (

Table 13) most of the subjects in Group A chose the highest option in this aspect (grade 2, N = 18), while the 20 subjects of Group B chose option 0 (N = 16) or 1 (N = 4). Nobody in this group chose option 3 in contrast with 1 person in Group A.

The strong signification values obtained from the media analysis led to a possible positive effect of the proposed teaching model (

Table 14).

The Mann–Whitney test was applied for the media differences in independent samples

| Measures of association | Eta | Eta2 |

| Group * Expectations of moving the family to Malaga | 0.959 | 0.920 |

Table 15 shows very similar results, although in this occasion, the tendency towards a more positive evaluation of wellbeing in Malaga seems even more evident among members of Group A. Nobody in Group B indicated grade 4 and only one chose option 3. This option was selected by 6 members of Group A, who also indicated their preference for option 4 three times. More than half of the subjects of Group B opted for the lower grades of the scale (0 or 1, N = 15) while only 6 did the same in Group A.

As

Table 16 shows, the signification and association measures were more moderate in this case.

The Mann–Whitney test was applied for media differences in independent samples

| Measures of association | Eta | Eta2 |

| Group * Wellbeing in Malaga | 0.515 | 0.265 |

The signification index of the positive correlations in

Table 17 is high enough in all cases so that the belonging to learning groups can be considered a relevant explanatory factor of the variables that measure the migrants´ degree of wellbeing in their host community. The form of the variables correlated in

Table 17 were recodified on the basis of a fictitious variable in which Group B = 0 and Group A = 1. Variables Sentence 1, Sentence 2, Sentence 3 and Wellbeing in Malaga were measured on a scale of

gradation from 0 (completely in disagreement) to 6 (completely in agreement).

At the end, we made a recodification of some of the items of the questionnaire, whose scales were compatible and from them, two new variables were made in order to measure: (1) the informant´s global subjective satisfaction (Individual Subjective Satisfaction, ISS) and (2) the individual sensation of general wellbeing (General Wellbeing Index, GWI).

The first case deals with the original questionnaire variables, which measure on a scale from minor to major (1 to 5) the integration and opening of the analysed migrants to the host region and its inhabitants. Variable 25 was recodified to adapt it to the new scale.

23. You have meetings in your free time

Only with members of my family

Only with people of my origin or culture

Never with people of my origin or culture, except with Spaniards

With every type of people, including Spaniards

24. You participate in associations or groups in free time

No

Yes, only with people of my origin or culture

Yes, but never with people of my origin or culture

Yes, with every type of people, except with Spaniards

Yes, with every type of people, including Spaniards

25. Do you have difficulties to integrate with Malaganians or groups of them? Think, for example. if you feel comfortable when you are with these people and consider you an equal or if, on the contrary, when you are with these people you feel a foreigner

Yes, I have many difficulties to integrate

No, but I only prefer to be with people of my zone or culture

No, I do not look for this type of contact

Since I study Spanish I find it easier to integrate

I do not have any problems

28. How do you evaluate the native population of Malaga?

31. In what way do you feel integrated with the customs of the Malaga society? (traditions like Easter, Carnival, etc.)

Not at all

Very little

Little

Enough

Quite a lot

33. What are your intentions now?

To make money and go back in less than a year

To make money to build a better life in my country of origin

To start a new life in another country

To go back and stay with my family

To stay in Malaga

34. What do you think you will do in the next 5 years?

Going back to my country

Moving to another country

Moving to another Spanish autonomous community

Moving to another city in Andalusia

Staying in Malaga

35. What do you think of doing after the next 5 years? (As a life project)

Going back to my country

Moving to another country

Moving to another Spanish autonomous community

Moving to another city of Andalusia

Staying in Malaga

The resulting variable of the reformulation of the previous ones (ISS calculated as a function of the number of times informants opted for the values of the scale 1–5 in all the considered variables) showed a normal distribution with some differences of means of a low potency (

Table 18).

The Mann–Whitney test was applied for the differences of means in independent samples

| Measures of association | Eta | Eta2 |

| ISS * Group | 0.490 | 0.240 |

| Z punctuation (ISS) * Group | 0.490 | 0.240 |

The second recodification was done from the individual original variables, which measured on a 0–6 scale certain wellbeing parameters related to the informants´ stay in Malaga (variables 39–42 in the questionnaire). In this occasion, the new recodified scale in three levels of intervals according to the informants´ original answers (0–2 = Level 0; 3 = Level 1; 4–6 = Level 2). The differences of means show results of very high significance, now with values de Eta

2 of high potency (

Table 19).

The Mann–Whitney test was applied for differences of means in independent samples

| Measures of Association |

| | Eta | Eta2 |

| GWI * Group | 0.872 | 0.761 |

Test of independent samples

| GWI | Levene Test for Equality of Variances | T test for the Equality of Variances |

| F | Sig. | t | df | Bilateral Sig. | Differences of Means |

| | Equal variances have been assumed | 4.457 | 0.041 | −19.000 | 38 | 0.000 | −0.95000 |

| Equal variances have not been assumed | | | −19.000 | 19.000 | 0.000 | −0.95000 |

Our significative results, and a final analysis of regression by steps, helped us to design a statistical model, which confirms: (1) the high correlation observed between group belonging and the variable GWI and (2) the weak correlation between the variables

gender and

education and the dependent variable (GWI, both variables were excluded from the model,

Table 20). Thus, we discarded that the internal group imbalance with regard to the educational level of their members (

Table 5 and

Table 6) was camouflaging a possible covert effect of this variable on the results.

| Eliminated Variables |

| Model | Beta in | t | Sig. | Partial Correlation | Colinearity Statistics |

| Tolerance | VIF | Minimal Tolerance |

| 1 | Gender | 0.041 b | 0.813 | 0.422 | 0.132 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Recodified Education | −0.029 b | −0.536 | 0.595 | −0.088 | 0.875 | 1.143 | 0.875 |

| Summary of the Model |

| Model | R | R square | Corrected R square | Standard error in the estimate | Durbin-Watson |

| 1 | 0.951 a | 0.905 | 0.902 | 0.15811 | 2.108 |

| ANOVA a |

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

| 1 | Regression | 9.025 | 1 | 9.025 | 361,000 | 0.000 b |

| Residual | 0.950 | 38 | 0.025 | | |

| Total | 9.975 | 39 | | | |

| Coefficients |

| Model | Non-Standardised Coefficients | Typified Coefficients | T | Sig. |

| B | Standard Error | Beta |

| 1 | (Constant) | 1.000 | 0.035 | | 28.284 | 0.000 |

| Group | 0.950 | 0.050 | 0.951 | 19.000 | 0.000 |