Perfect-Perfective Variation across Spanish Dialects: A Parallel-Corpus Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| (1) | Ana | ha | desayunado | en | ese | café |

| Ana | have.3sg.prs | have-breakfast.ptcp | at | that | café | |

| ‘Ana has had breakfast at that café’ | ||||||

| (2) | Ana | desayunó | en | ese | café | |

| Ana | have-breakfast.3sg.pst.prfv | at | that | café | ||

| ‘Ana had breakfast at that café’ | ||||||

2. Perfect-Perfective Past Variation

2.1. Present Perfect and Perfective Past Markers Crosslinguistically

| (3) | Resultative: | Mary has read Middlemarch. | [Portner 2003: 459, ex. (2)] |

| (4) | Experiential: | Mary has gone to that bar (and she might go again). | |

| (5) | Continuative: | Mary has lived in London for 5 years (and she still does). | |

| (6) | Hot news/hodiernal: | Mary has won the contest (just now) | |

2.2. The Use of the Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto and the Pretérito Indefinido

2.3. Dialectal Variation in Spanish in the Perfect-Perfective Domain: Synchrony and Diachrony

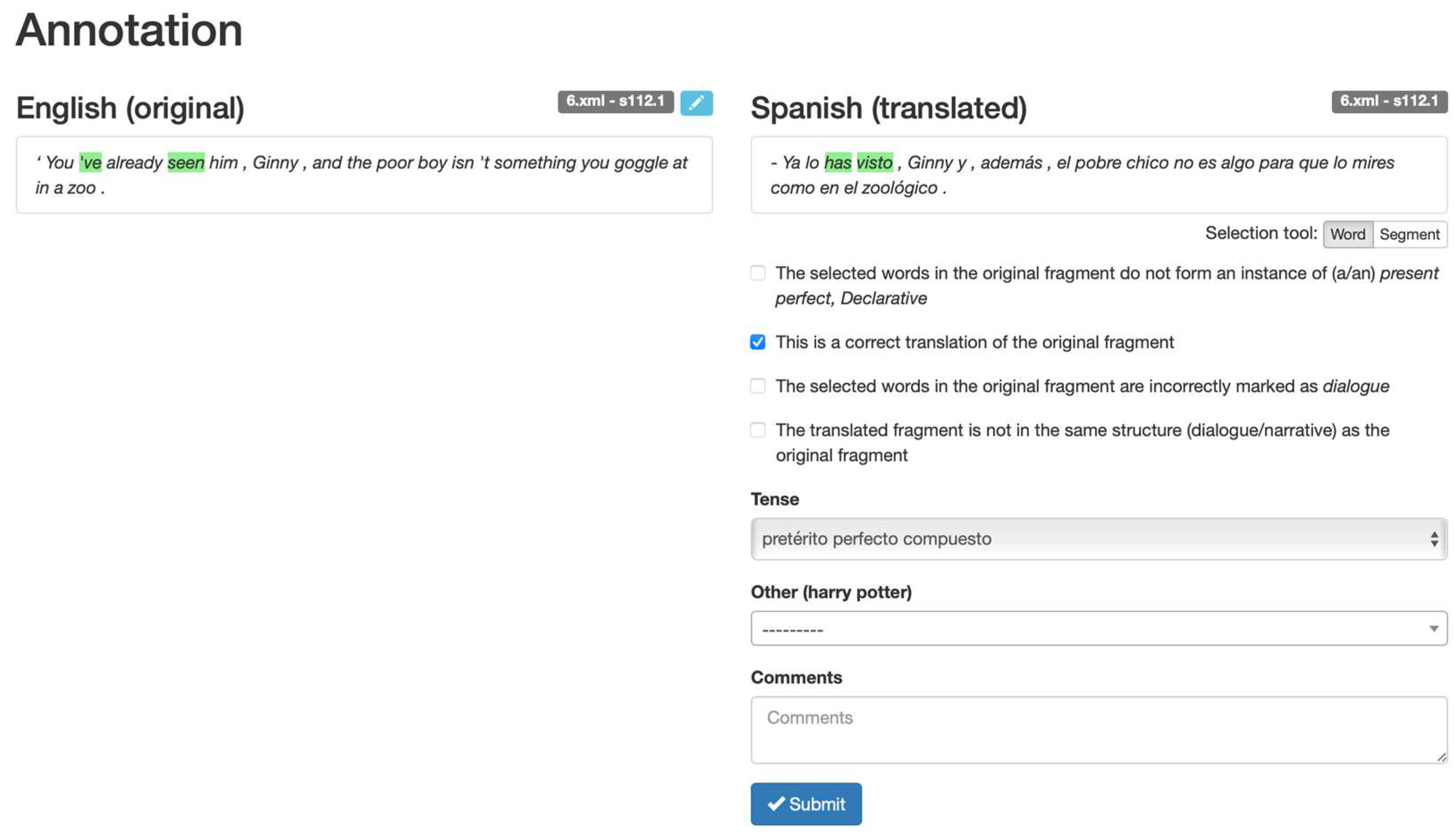

3. Methodology: Parallel Corpus and Multidimensional Scaling

4. Results

5. Interim Discussion: The Need for a Triangulation of Methods

6. Variables at Play in the Selection of Perfect-Perfective Forms across Spanish Dialects

6.1. Inherent Aspect

| (7) | Terminative: “And finally, bird watchers everywhere have reported that the nation’s owls have been behaving very unusually today”. |

| (8) | Durative: “I have form only when I can share another’s body… but there have always been those willing to let me into their hearts and minds”. |

6.2. Polarity

| (9) | Affirmative: “Unicorn blood has strengthened me, these past weeks…” |

| (10) | Negative: “My mistake, my mistake—I didn’t see you—of course, you’re invisible”. |

6.3. Clause Type

| (11) | Main: “My scar keeps hurting me. It’s happened before, but never as often as this”. |

| (12) | Subordinate: “Mr. Ronald Weasley and Miss Granger will be most relieved you have come round, they have been extremely worried”. |

6.4. Sentential Force

| (13) | Declarative: “Snape’s already got past Fluffy”. |

| (14) | Non-declarative: “’How did you know it was me?’, she asked”. |

6.5. Grammatical Person

| (15) | First: “Snape came out and asked me what I was doing, so I said I was waiting for Flitwick”. |

| (16) | Second: “Haven’t you heard what it was like when he was trying to take over?”. |

| (17) | Third: “A lot of the greatest wizards haven’t got an ounce of logic; they’d be stuck in here forever”. |

6.6. Grammatical Number

| (18) | Singular: “The Potters, that’s right, that’s what I heard”. |

| (19) | Plural: “We’ve had Sprout, that was the Devil’s Snare”. |

6.7. Reading

| (20) | Continuative: “Since then, I have served him faithfully”. |

| (21) | Experiential: “My dear Professor, I’ve never seen a cat sit so stiffy”. |

| (22) | Hodiernal: “… there have been hundreds of sightings of these birds flying in every direction since sunrise” |

| (23) | Resultative: “As for the Stone, it has been destroyed”. |

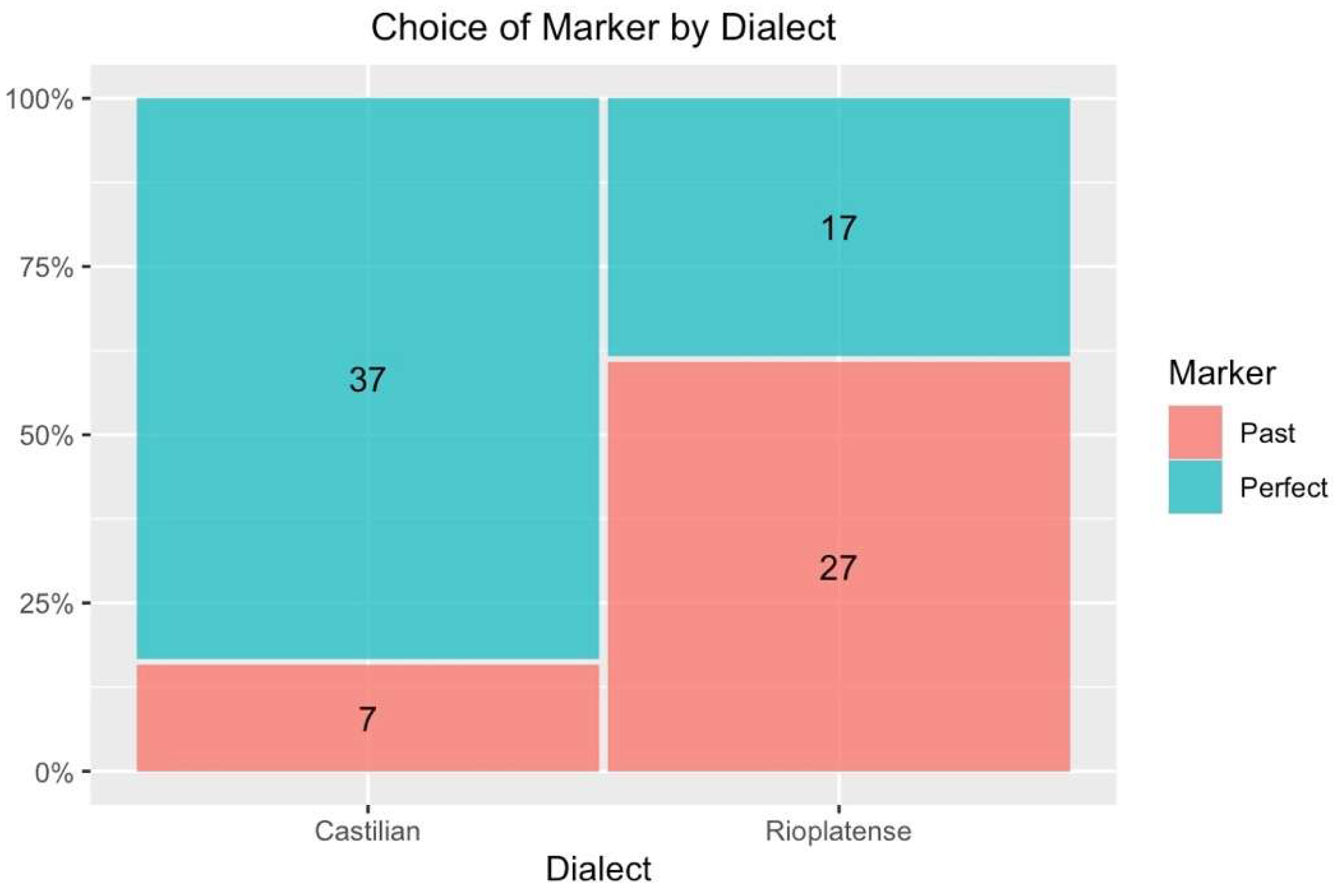

7. Results from Variable Coding

8. General Discussion

| (24) | English: “I have form only when I can share another’s body… but there have always been those willing to let me into their hearts and minds”. |

| (25) | Castilian Spanish: “Tengo forma sólo cuando puedo compartir el cuerpo de otro… pero siempre ha habido seres deseosos de dejarme entrar en sus corazones y en sus mentes.” |

| (26) | Rioplatense Spanish: “Tengo forma sólo cuando puedo compartir el cuerpo de otro… pero siempre han estado aquellos deseosos de dejarme entrar en sus corazones y en sus mentes.” |

| (27) | English: “… there have been hundreds of sightings of these birds flying in every direction since sunrise”. |

| (28) | Castilian Spanish: “… se han producido cientos de avisos sobre el vuelo de estas aves en todas direcciones, desde la salida del sol.” |

| (29) | Rioplatense Spanish: “… hubo cientos de avisos sobre el vuelo de esos pájaros en todas direcciones, desde la salida del sol.” |

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | We use small caps to indicate a crosslinguistic marker type comprising a set of language-specific forms, such as perfect for the Present Perfect in English, the Passé Composé in French, the Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto in Spanish, and so forth. We reserve italics to indicate language-specific forms, and we use plain text to refer to meanings. |

| 2 | All interlinear glosses follow Leipizg Glossing Rules. |

| 3 | By Castilian Spanish, we refer to the variety of Peninsular Spanish spoken in Central Spain (e.g., Madrid and its surroundings). |

| 4 | We use the term Mexican Altiplano Spanish to refer to the Spanish spoken in Mexico City and its surroundings. |

| 5 | Rioplatense Spanish, in this paper, indicates the Spanish spoken in Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

| 6 | We are very much aware that there is more diversity in the Spanish spoken within these regions. For instance, the Spanish spoken in Chile is lexically very different from the Spanish spoken in Argentina, but these are the idealized divisions made by the publishing house, with the intention to appeal to the readers of these (broad) geographical areas. |

| 7 | The edition intended for Spain was published in Barcelona because the headquarters of the publishing house are in that city. However, the translation was done into the standard norm of the Spanish spoken in Spain, which reflects the Spanish spoken in the Central regions: Castilian Spanish. |

| 8 | One anonymous reviewer points out that dialect zones are usually divided on the basis of spoken language, so that a notion like ‘Rioplatense Spanish’ normally refers to an urban spoken vernacular, the Spanish spoken in Buenos Aires. Written registers, on the other hand, would follow some sort of standard norm. We agree with this point, but still consider that describing consistent grammatical patterns found in different written standards of Spanish can shed light into native speakers’ grammars from the same geographical areas where these translations were done. |

| 9 | Sundell (2010) works with the fifth book in the HP series, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, and its translations to Spanish. In that case, there was an original translation into Castilian Spanish that later was adapted for the Southern Cone by an Argentinian translator, and to the rest of Latin America by a Mexican translator. For details about those translations, see Sundell (2010, chap. 2). It seems that a similar process (but from Rioplatense Spanish to the other two varieties) occurred when the first book was published, since the original publishing house of the first book was in Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

| 10 | A reviewer asks how the dimensions in the figures should be interpreted. In MDS, dimensions do not have an inherent linguistic meaning, but are the result of applying the method to the data, which compares similarities across contexts based on the forms chosen by each language to express a given meaning (van der Klis and Tellings 2022). While some studies (e.g., Wälchli and Cysouw 2012) assign linguistic features to the different axes in their maps, our approach is based not on axis interpretation, but on the analysis of clusters of datapoints in the maps. We argue that every cluster of points can point to a relevant linguisic distinction with respect to the distribution of the markers under comparison, since different clusters indicate that at least one language/dialect has changed the grammatical form used to express that context/meaning. |

| 11 | One reviewer asks about the rationale for annotating the corpus in the English original and not in one (or more) of the Spanish translations. We assume that staying as close as possible to the meaning intended in the original allows us to control for any artifact introduced by the translators (i.e., ‘translation-induced variation’, as opposed to grammatical variation). |

References

- Alarcos Llorach, Emilio. 1947. Perfecto simple y compuesto en español. Revista de Filología Española 31: 108–39. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcos Llorach, Emilio. 1970. Estudios de Gramática Funcional del Español. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Azpiazu, Susana. 2013. Antepresente y pretérito en el español peninsular: Revisión de la norma a partir de evidencias empíricas. Anuario de Estudios Filológicos 36: 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Azpiazu, Susana. 2014. Del perfecto al aoristo en el antepresente peninsular: Un fenómeno discursivo. In Formas Simaples y Compuestas de Pasado en el Verbo Español. Edited by Susana Azpiazu. Lugo: Axac, pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Azpiazu, Susana. 2015. La variación antepresente/pretérito en dos áreas del español peninsular. Verba 42: 269–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azpiazu, Susana. 2021. Uso evidencial del perfecto compuesto en el español de Ecuador. In La Interconexión de las Categorías Semántico-Funcionales en Algunas Variedades del Español. Edited by Verónica Böhm and Anja Hennemann. Berlin: Peter Lang, pp. 237–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Maechler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berschin, Helmut. 1975. A propósito de la teoría de los tiempos verbales: Perfecto simple y perfecto compuesto en el español peninsular y colombiano. Thesaurus 30: 539–56. [Google Scholar]

- Berschin, Helmut. 1976. Präteritum und Perfektgebrauch im Heutigen Spanisch. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, Anne, Yurika Aonuki, Sihwei Chen, Joash Gambarage, Laura Griffin, Marianne Huijsmans, Lisa Matthewson, Daniel Reisinger, Hotze Rullmann, Raiane Salles, and et al. 2022. Nobody’s Perfect. Languages 7: 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaards, Maarten. 2022. The Discovery of Aspect: A heuristic parallel corpus study of ingressive, continuative and resumptive viewpoint aspect. Languages, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan, Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca. 1994. The Evolution of Grammar: The Grammaticalization of Tense, Aspect and Modality in the Languages of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Camus Bergareche, Bruno. 2008. El perfecto compuesto (y otros tiempos compuestos) en las lenguas románicas: Formas y valores. In Tiempos Compuestos y Formas Verbales Complejas. Edited by Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez. Madrid: Iberoamericana, pp. 65–102. [Google Scholar]

- Condoravdi, Cleo, and Ashwini Deo. 2014. Aspect shifts in Indo-Aryan and trajectories of semantic change. In Language change at the Syntax-Semantics Interface. Edited by Chiara Gianollo, Agnes Jäger and Doris Penka. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 261–92. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Östen. 1985. Tense and Aspect Systems. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge, Bob. 1999. El tiempo de todos los tiempos: El uso del presente perfecto en el español bonaerense. In Actas del XI Congreso Internacional de la ALFAL. Edited by José A. Samper Padilla and Magnolia T. Déniz. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, pp. 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge, Bob. 2001. El valor del presente perfecto y su desarrollo histórico en el español americano. In Estudios Sobre el Español de América, Actas del V Congreso Internacional de El Español de América. Edited by Hermógenes Perdiguero and Antonio Álvarez. Burgos: Universidad de Burgos, pp. 838–48. [Google Scholar]

- De Kock, Josse. 1989. Pretéritos perfectos simples y compuestos en España y América. In El Español de América: Actas del III Congreso Internacional del Español de América. Valladolid: Junta de Castilla y León, pp. 481–94. [Google Scholar]

- de Swart, Henriëtte. 2007. A cross-linguistic discourse analysis of the Perfect. Journal of Pragmatics 39: 2273–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischman, Suzanne. 1983. From pragmatics to grammar: Diachronic reflections on complex pasts and futures in Romance. Lingua 60: 183–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanella de Weinberg, María Beatriz. 1992. La estandarización del español bonaerense. In Scripta Philologica: In Honorem Juan M. Lope Blanch. Edited by Elisabeth Luna Traill. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 425–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Martín. 2020. On the Synchrony and Diachrony of the Spanish Imperfective Domain: Contextual Modulation and Semantic Change. Ph.D. thesis, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- González, Paz. 2003. Aspects on Aspect: Theory and Applications of Grammatical Aspect in Spanish. Ph.D. thesis, Utrecht Institute of Linguistics—OTS, Utrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- González, Paz, and Carmen Kleinherenbrink. 2021. Target variation as a contributing factor in TAML2 production. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación 87: 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Paz, and Henk J. Verkuyl. 2017. A binary approach to Spanish tense and aspect: On the tense battle about the past. Borealis—An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 6: 97–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González, Paz, Margarita Jara Yupanqui, and Carmen Kleinherenbrink. 2019. The microvariation of the Spanish Perfect in three varieties. Isogloss 4: 115–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Martin. 1982. The ‘past simple’ and the present perfect in Romance. In Studies in the Romance Verb: Essays Offered to Joe Cremona on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday. Edited by Nigel Vincent and Martin Harris. London: Croom Helm, pp. 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn, Torsten, Frank Bretz, and Peter Westfall. 2008. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometrical Journal 50: 346–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Howe, Chad. 2006. Cross-Dialectal Features of the Spanish Present Perfect: A Typological Analysis of Form and Function. Ph.D. thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Iatridou, Sabine, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Roumyana Izvorski. 2001. Observations about the form and meaning of the perfect. In Ken Hale: A Life in Language. Edited by Michael Kenstowicz. Cambridge and London: MIT Press, pp. 189–238. [Google Scholar]

- Jara Yupanqui, Margarita. 2012. Peruvian Amazonian Spanish: Linguistic variation, language ideologies, and identities. Sociolinguistic Studies 6: 445–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kany, Charles. 1945. American-Spanish Syntax. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Wolfgang. 1992. The Present Perfect puzzle. Language 68: 525–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubarth, Hugo. 1992. El uso del pretérito simple y compuesto en el español hablado de Buenos Aires. In Scripta Philologica: In Honorem Juan M. Lope Blanch. Edited by Elisabeth Luna Traill. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 553–66. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bruyn, Bert, Martijn van der Klis, and Henriëtte de Swart. 2019. The perfect in dialogue: Evidence from Dutch. Linguistics in the Netherlands 36: 162–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbner, Sebastian. 2002. Is the German Perfekt a Perfect Perfect? In More Than Words: A Festschrift for Dieter Wunderlich. Edited by Ingrid Kaufmann and Barbara Stiebels. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, pp. 369–91. [Google Scholar]

- McCawley, James D. 1971. Tense and time reference in English. In Studies in Linguistic Semantics. Edited by Charles J. Fillmore and Terence Langendoen. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, pp. 96–113. [Google Scholar]

- McCawley, James D. 1981. Notes on the English present perfect. Australian Journal of Linguistics 1: 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoard, Robert William. 1978. The English Perfect: Tense-Choice and Pragmatic Inferences. Amsterdam: North-Holland (Elsevier). [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis, Laura A. 1994. The ambiguity of the English present perfect. Journal of Linguistics 30: 111–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreno de Alba, José. 1978. Valores de las Formas Verbales en el Español de México. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, Gijs, Gert-Jan Schoenmakers, Olaf Hoenselaar, and Helen de Hoop. 2022. Tense and aspect in a Spanish literary work and its translations. Languages, in press. [Google Scholar]

- NGRAE. 2009. Real Academia Española y Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española. In Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, Atsuko, and Jean-Pierre Koening. 2010. What is a Perfect State? Language 86: 611–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portner, Paul. 2003. The (Temporal) semantics and (Modal) pragmatics of the perfect. Linguistics and Philosophy 26: 459–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potterglott. 2022. Harry Potter and the Spanish Tykes. Available online: https://www.potterglot.net/harry-potter-and-the-spanish-tykes/ (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Reichenbach, Hans. 1947. Elements of Symbolic Logic. New York: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Louro, Celeste. 2009. Perfect Evolution and Change: A Sociolinguistic Study of the Preterit and Present Perfect Usage in Contemporary and Earlier Argentina. Ph.D. thesis, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Louro, Celeste. 2012. Los tiempos de pasado y los complementos adverbiales en el español rioplatense argentino: Del siglo XIX al presente. Signo and Seña 22: 215–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Louro, Celeste, and Margarita Jara Yupanqui. 2011. Otra mirada a los procesos de gramaticalización del presente perfecto en español: Perú y Argentina. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 4: 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaden, Gehrard. 2009. Present Perfects compete. Linguistics and Philosophy 32: 115–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaden, Gehrard. 2012. Modelling the ‘aoristic drift of the Present Perfect’ as Inflation. An Essay in Historical Pragmatics. International Review of Pragmatics 4: 261–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenter, Scott. 1994. The grammaticalization of an anterior in progress: Evidence from a Castilian Spanish dialect. Studies in Language 18: 71–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenter, Scott, and Rena Torres Cacoullos. 2008. Defaults and indeterminacy in temporal grammaticalization: The ‘perfect’ road to perfective. Language Variation and Change 20: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soto, Guillermo. 2015. El pretérito perfecto compuesto en el español estándar de nueve capitales americanas: Frecuencia, subjetivización y deriva aorística. In Formas Simples y Compuestas de Pasado en el Verbo Español. Edited by Susana Azpiazu. Lugo: Axac, pp. 131–46. [Google Scholar]

- Squartini, Mario, and Pier Marco Bertinetto. 2000. The simple and compound past in Romance languages. In Tense and aspect in the languages of Europe. Edited by Östen Dahl. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, vol. 6, pp. 385–402. [Google Scholar]

- Sundell, David. 2010. El Español Neutro en la Traducción Intralingüística. Un Estudio Sobre el uso del Español Neutro en las Traducciones Intralingüísticas de Harry Potter y la Orden del Fénix. Master’s thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Tarantino, Patricio. 2018. Historia Secreta del Mundo Mágico. Buenos Aires: Numeral. [Google Scholar]

- van der Klis, Martijn, Bert Le Bruyn, and Henriëtte de Swart. 2017. Mapping the Perfect via Translation Mining. In Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Volume 2—Short Papers. Edited by Mirella Lapata, Phil Blunsom and Alexander Koller. Valencia: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 497–502. [Google Scholar]

- van der Klis, Martijn, Bert Le Bruyn, and Henriëtte de Swart. 2021. A multilingual corpus study of the competition between PAST and PERFECT in narrative discourse. Journal of Linguistics 58: 423–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Klis, Martijn, and Jos Tellings. 2022. Multidimensional scaling and linguistic theory. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, advance online version. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyl, Henk J. 1972. On the Compositional Nature of the Aspects. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyl, Henk J. 1993. A Theory of Aspectuality. The Interaction between Temporal and Atemporal Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyl, Henk J. 1999. Aspectual Issues. Studies of Time and Quantity. Stanford: CLSI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Vet, Co. 1992. Le passé composé: Contextes d’emploi et interprétation. Cahiers de Praxématique 19: 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wälchli, Bernhard, and Michael Cysouw. 2012. Lexical typology through similarity semantics: Toward a semantic map of motion verbs. Linguistics 50: 671–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westmoreland, Maurice. 1988. The distribution and the use of the present perfect and the past perfect forms in American Spanish. Hispania 71: 379–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, Bodo. 2019. Statistics for Linguistics. An Introduction Using R. New York and London: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

| Dialect | Only Mexican PPC | All Dialects PI | All Dialects PPC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexican | 26.60% | 93.10% | 81.50% | 55.00% |

| Rioplatense | 81.25% | 80.00% | 65.70% | 77.30% |

| Castilian | 56.25% | 57.10% | 65.70% | 58.60% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuchs, M.; González, P. Perfect-Perfective Variation across Spanish Dialects: A Parallel-Corpus Study. Languages 2022, 7, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030166

Fuchs M, González P. Perfect-Perfective Variation across Spanish Dialects: A Parallel-Corpus Study. Languages. 2022; 7(3):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030166

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuchs, Martín, and Paz González. 2022. "Perfect-Perfective Variation across Spanish Dialects: A Parallel-Corpus Study" Languages 7, no. 3: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030166

APA StyleFuchs, M., & González, P. (2022). Perfect-Perfective Variation across Spanish Dialects: A Parallel-Corpus Study. Languages, 7(3), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030166