Productive Vocabulary Knowledge Predicts Acquisition of Spanish DOM in Brazilian Portuguese-Speaking Learners

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Differential Object Marking in Spanish and BP

| (1a) | El | padre | cuida | a | la hija. | [+animate, +definite] |

| The | father | takes care | of | DOM the daughter | ||

| ‘The father takes care of the daughter.’ | ||||||

| (1b) | El | padre | cuida | Ø | la | casa. | [−animate, +definite] |

| The | father | takes care | of | the | house | ||

| ‘The father takes care of the house.’ | |||||||

| (1c) | El | padre | cuida | (a) | una vaca. | [+animate, −definite] |

| The | father | takes care | of | (DOM) a cow | ||

| The father takes care of a cow.’ | ||||||

| (1d) | El | padre | busca (a) | una niñera | [+animate, −definite] |

| The | father | looks for | (DOM) a nanny | ||

| ‘The doctor looks for a “nanny”’ | |||||

| (1e) | El | detective | no encontró | a nadie | [+animate, −definite] |

| The | detective | did not find | DOM anyone | ||

| ‘The detective did not find anyone.’ | |||||

| (1f) | El | ácido | corroe | al metal. | [−animate, +definite] |

| The | acid | corrodes | DOM the metal | ||

| ‘The acid corrodes the metal.’ | |||||

- (2a)

- Animacy scale: human > animate > inanimate

- (2b)

- Definiteness scale: personal pronoun > proper name > definite NP > indefinite specific NP > non-specific NP

| (3a) | Ana me | abraça | a mim. |

| Ana | hugs | DOM me | |

| ‘Ana hugs me.’ | |||

| (3b) | Ana | abraça | o menino. |

| Ana | hugs | Ø the boy. | |

| ‘Ana hugs the boy.’ | |||

| (4a) | Ana | abraça | o menino | e | ao avô |

| Ana | hugs | the boy | and | DOM the grandfather | |

| ‘Ana hugs the boy and the grandfather’. | |||||

| (4b) | Ana | abraçou | o menino | e | ao avô também |

| Ana | hugged | the boy | and | DOM the grandfather too | |

| Ana hugged the boy and the grandfather too. | |||||

| (4c) | Ana | abraçou | o menino | e | o avô também |

| Ana | hugged | the boy | and | Ø the grandfather too. |

2.2. The Acquisition of DOM in L2 Spanish

2.3. Lexical Knowledge as a Proxy for Overall Proficiency

3. Research Questions

4. Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. Data Collection Instruments and Procedures

4.3. Data Analysis

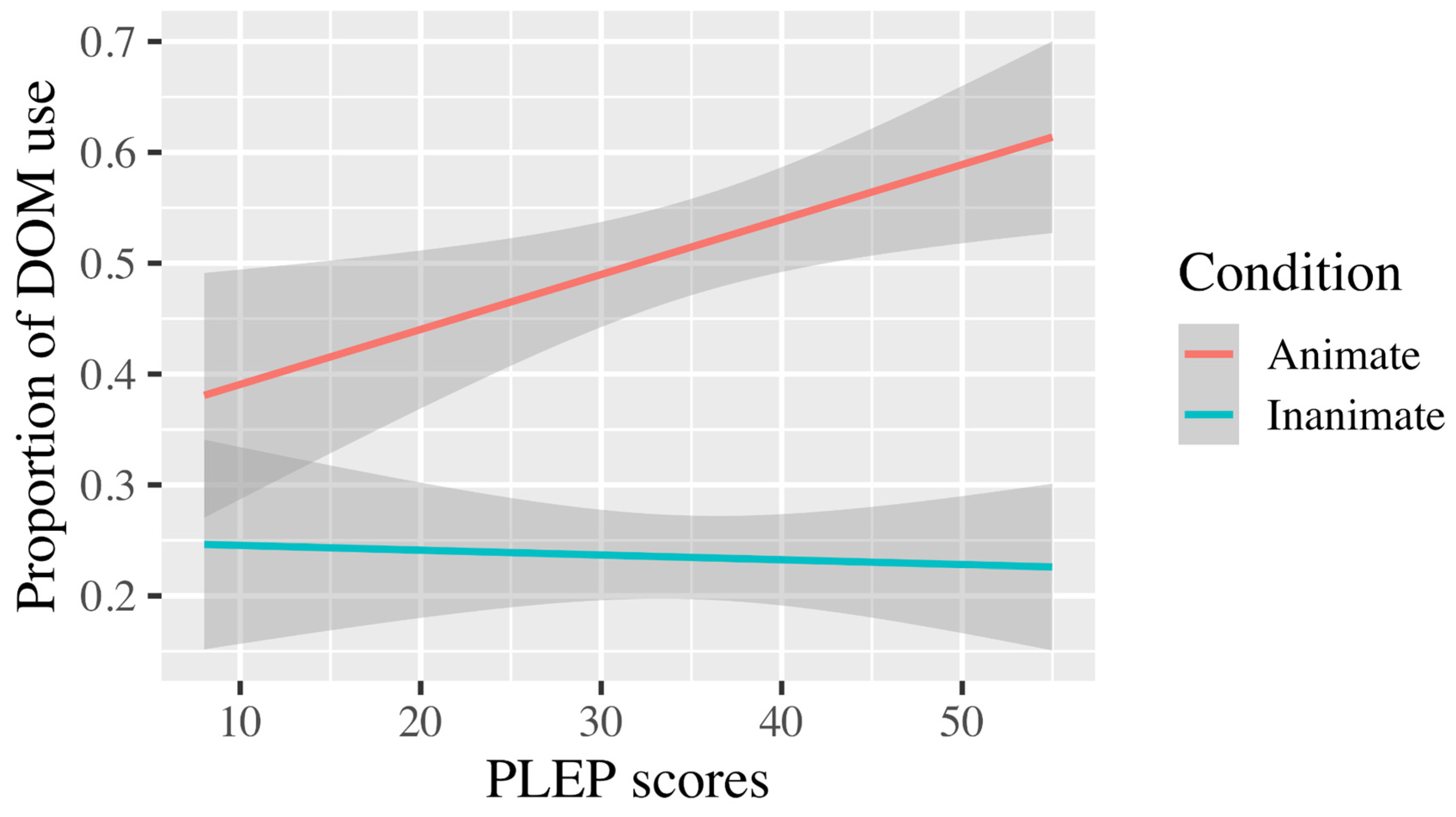

5. Results

5.1. Results from Spanish Data

5.1.1. Elicited Production Task

Individual Analysis Attending to Developmental Stages

Individual Analysis Attending to Verbs Tested

5.1.2. Acceptability Judgment Task

5.2. Results from BP Data

5.3. Summary of the Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Aissen, Judith. 2003. Differential object marking: Iconicity vs. economy. Natural Language Linguistic Theory 21: 435–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, Thamer. 2018. Minding the Gap in Vocabulary Knowledge: Incidental Focus on Collocation through Reading. Arab World English Journal 9: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, Thamer. 2020. Investigating the relationship between vocabulary knowledge and FL speaking performance. International Journal of English Linguistics 10: 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Elizabeth, and Judith C. Goodman. 1997. On the inseparability of grammar and the lexicon: Evidence from acquisition, aphasia and real-time processing. Language and Cognitive Processes 12: 507–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bedore, Lisa M., Elizabeth D. Peña, Connie L. Summers, Karin M. Boerger, Maria D. Resendiz, Kai Greene, Thomas M. Bohman, and Ronald B. Gillam. 2012. The measure matters: Language dominance profiles across measures in Spanish-English bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 616–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossong, Georg. 1991. Differential object marking in Romance and beyond. New Analysis in Romance Linguistics 69: 143–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, Melissa, and Silvina Montrul. 2008. The role of explicit instruction in the L2 acquisition of the a-personal. In Selected Papers from the 10th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Joyce Bruhn de Garavito and Elena Valenzuela. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, Melissa, and Silvina Montrul. 2009. Instructed L2 acquisition of differential object marking in Spanish. Little Words: Their History, Phonology, Syntax, Semantics, Pragmatics and Acquisition 2009: 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, Scott A., Tom Salsbury, and Danielle S. McNamara. 2012. Predicting the proficiency level of language learners using lexical indices. Language Testing 29: 243–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curione, Alberto. 2021. The Acquisition of Differential Object Marking (DOM) in Spanish by Italian University Students. Venice: Unpublished Tesi Di Laurea, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia. [Google Scholar]

- Cuza, Alejandro, Ana Teresa Pérez-Leroux, and Liliana Sánchez. 2013. The role of semantic transfer in clitic-drop among simultaneous and sequential Chinese-Spanish bilinguals. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 35: 93–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrino, Sonia. 2017. Reflexōes sobre a marcação morfológica do objeto direito por a em português brasileiro. Estudos Linguísticos e Literários 58: 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrino, Sonia, and Monica Alexandrina Irimia. 2019. Differential object marking in Brazilian Portuguese. Revista Letras 99: 177–201. [Google Scholar]

- Daller, Helmut, Roeland Van Hout, and Jeanine Treffers-Daller. 2003. Lexical richness in the spontaneous speech of bilinguals. Applied Linguistics 24: 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Mark. 2018a. El Corpus del Español: NOW. Available online: https://www.corpusdelespanol.org (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Davies, Mark. 2018b. O Corpus do Português: NOW. Available online: https://www.corpusdoportugues.org (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Dos Santos, Ana Cristina, and Diego Fernando Cunha Silva. 2005. El análisis de errores: Una herramienta en la enseñanza de la gramática de ELE para alumnos brasileños. Actas del XIII Seminario de Dificultades Específicas de la Enseñanza del Español a Lusohablantes 1: 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, Lloyd M., and Leota M. Dunn. 1981. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. Circle Pines: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, Andrew P., and Kristina McCollam Wiebe. 2004. Learner readiness and L2 production in Spanish: Processability theory on trial. Estudios de Lingüística Aplicada 40: 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- García García, Marco. 2018. NP exclamatives and focus. In Focus Realization in Romance and Beyond. Edited by Melanie Uth. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 229–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan, Tamar H., Gali H. Weissberger, Elin Runnqvist, Rosa I. Montoya, and Cynthia M. Cera. 2012. Self-ratings of spoken language dominance: A Multilingual Naming Test (MINT) and preliminary norms for young and aging Spanish–English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guijarro-Fuentes, Pedro. 2012. The acquisition of interpretable features in L2 Spanish: Personal a. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 701–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro-Fuentes, Pedro, and Theodoros Marinis. 2007. Acquiring phenomena at the syntax/semantics interface in L2 Spanish: The personal preposition a. Eurosla Yearbook 7: 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyllstad, Henrik. 2016. Comparing L1 and L2 phraseological processing: Free combinations, collocations and idioms. Paper presented at the American Association for Applied Linguistics, Hilton Orlando, Orlando, FL, USA, April 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Haznedar, Belma, and Bonnie D. Schwartz. 1997. Are there Optional Infinitives in child L2 acquisition? Paper presented at the 21st Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development, Boston, MA, USA, November 21; Edited by Elizabeth Hughes, Mary Hughes and Annabel Greenhill. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 257–68. [Google Scholar]

- He, Chunxiu. 2019. A Review on Diagnostic Vocabulary Tests. International Journal of Higher Education 8: 126–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Esther. 2022. The Effects of Lexical Properties of Nouns and Verbs on L2 and Heritage Differential Object Marking. Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Izura, Cristina, Fernando Cuetos, and Marc Brysbaert. 2014. Lextale-Esp: A Test to Rapidly and Efficiently Assess the Spanish. Vocabulary Size. Psicologica 35: 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2008. Feature-assembly in second language acquisition. In The Role of Formal Features in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Juana Liceras, Helmut Zobl and Helen Goodluck. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 106–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2009. Some thoughts on the contrastive analysis of features in second language acquisition. Second Language Research 25: 173–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, Batia, and Tami Aviad-Levitzky. 2017. What type of vocabulary knowledge predicts reading comprehension: Word meaning recall or word meaning recognition? The Modern Language Journal 101: 729–41. [Google Scholar]

- Laufer, Batia, and Paul Nation. 1999. A vocabulary-size test of controlled productive ability. Language Testing 16: 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonetti, Manuel. 2004. Specificity and differential object marking in Spanish. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 3: 75–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonetti, Manuel. 2008. Specificity in clitic doubling and in differential object marking. Probus International Journal of Romance Linguistics 20: 33–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Otero, Julio César. 2020. On the acceptability of the Spanish DOM among Romanian-Spanish bilinguals. The Acquisition of Differential Object Marking Trends in Language Acquisition Research 2020: 161–81. [Google Scholar]

- López Otero, Julio César. 2022. Bidirectional cross-linguistic influence on DOM in Romanian-Spanish bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingualism 2022: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, Viorica, Henrike K. Blumenfeld, and Margarita Kaushanskaya. 2007. The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing Language Profiles in Bilinguals and Multilinguals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 50: 940–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Elisabeth, and Liliana Sánchez. 2021. Emerging DOM patterns in clitic doubling and dislocated structures in Peruvian-Spanish contact varieties. In Differential Object Marking in Romance. Edited by Johannes Kabatek, Philipp Obrist and Albert Wall. Berlin: De Gruyter, p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Milton, James. 2009. Measuring Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Milton, James. 2013. Measuring the contribution of vocabulary knowledge to proficiency in the four skills. In L2 Vocabulary Acquisition, Knowledge and Use, 2nd ed. Edited by Camilla Bardel, Christina Lindqvist and Batia Laufer. Birmingham: Eurosla, pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2019. The acquisition of differential object marking in Spanish by Romanian speakers. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada (RESLA) 32: 185–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Ayşe Gürel. 2015. The acquisition of differential object marking in Spanish by Turkish speakers. The Acquisition of Spanish by Speakers of Less Commonly Studied Languages 2015: 281–308. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Noelia Sánchez-Walker. 2013. Differential object marking in child and adult Spanish heritage speakers. Language Acquisition 20: 109–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Roumyana Slabakova. 2003. Competence Similarities between Native and Near-Native Speakers: An Investigation of the Preterite-Imperfect Contrast in Spanish. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 25: 351–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nation, Paul I. S. 1983. Testing and teaching vocabulary. Guidelines 5: 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nation, Paul I. S. 1990. Teaching and Learning Vocabulary. Boston: Heinle and Heinle. [Google Scholar]

- Nediger, Will, Acrisio Pires, and Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes. 2016. An experimental study of the L2 acquisition of Spanish differential object marking. In Proceedings of the 13th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 151–60. [Google Scholar]

- Prévost, Philippe, and Lydia White. 2000. Missing surface inflection or impairment in second language? Evidence from Tense and Agreement. Second Language Research 16: 103–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, David, and Linda Lin. 2019. The relationship between vocabulary knowledge and language proficiency. The Routledge Handbook of Vocabulary Studies 2019: 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, John C. 1943. Mill Hill Vocabulary Scale. London: H. K. Lewis. [Google Scholar]

- Read, John. 1993. The development of a new measure of L2 vocabulary knowledge. Language Testing 10: 355–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Brian, and David Malvern. 2007. Validity and threats to the validity of vocabulary measurement. Modelling and Assessing Vocabulary Knowledge 2007: 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Mondoñedo, Miguel. 2006. A [Person] Restriction on the Definiteness Effect in Spanish. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Edited by Emily Elfner and Martin Walkow. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, vol. 2, p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Mondoñedo, Miguel. 2008. The acquisition of Differential Object Marking in Spanish. Probus 20: 111–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, Norbert, Diane Schmitt, and Caroline Clapham. 2001. Developing and exploring the behaviour of two new versions of the Vocabulary Levels Test. Language Testing 18: 55–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Bonnie D., and Rex A. Sprouse. 1996. L2 cognitive states and the full transfer/full access model. Second Language Research 12: 40–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenter, Scott. 2014. Two kinds of differential object marking in Portuguese and Spanish. In Portuguese-Spanish Interfaces: Diachrony, Synchrony, and Contact. Edited by Patricia Amaral and Ana Maria Carvalho. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, vol. 1, pp. 237–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Li, Ying Lu, and Tamar H. Gollan. 2014. Assessing language dominance in Mandarin–English bilinguals: Convergence and divergence between subjective and objective measures. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 17: 364–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrego, Esther. 1998. The Dependencies of Objects. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 1–197. [Google Scholar]

- Treffers-Daller, Jeanine. 2019. What defines language dominance in bilinguals? Annual Reviews of Linguistics 5: 375–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffers-Daller, Jeanine, and Tomasz Korybski. 2015. Using lexical diversity measures to operationalise language dominance in bilinguals. In Language Dominance in Bilinguals: Issues of Measurement and Operationalization. Edited by Carmen Silva-Corvalan and Jeanine Treffers-Daller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 106–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yun, and Jeanine Treffers-Daller. 2017. Explaining listening comprehension among L2 learners of English: The contribution of general language proficiency, vocabulary knowledge and metacognitive awareness. System 65: 139–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesche, Marjorie, and T. Sima Paribakht. 1996. Assessing second language vocabulary knowledge: Depth versus breadth. Canadian Modern Language Review 53: 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Michael. 1953. A General Service List of English Words: With Semantic Frequencies and a Supplementary Word-List for the Writing of Popular Science and Technology. London and New York: Longmans. [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe, Kristina McCollam. 2003. The Interface between Instruction Type and Learner Readiness in the Acquisition of Spanish Personal a and the Subjunctive. Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wiskandt, Niklas. 2021. Scale-based object marking in Spanish and Portuguese. Differential Object Marking in Romance 459: 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, Rosa. 2001. A marcação de Caso Acusativo na Interlíngua de Brasileiros que Estudam o Espanhol. Doctoral dissertation, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Songshan, and Xian Zhang. 2020. The Relationship between Vocabulary Knowledge and L2 Reading/Listening Comprehension: A Meta-Analysis. Language Teaching Research 26: 136216882091399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | States |

|---|---|

| Southeast (n = 37) | Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo |

| Northeast (n = 17) | Maranhão, Piauí, Ceará, Rio Grande do Norte, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Alagoas, and Bahia |

| South (n = 10) | Paraná, Santa Catarina, Rio Grande do Sul |

| Central-West (n = 2) | Distrito Federal |

| North (n = 1) | Tocantins |

| Spanish PLEP | BP PLEP | Spanish DELE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 34.96 | 56.45 | 45.2 |

| Standard deviation | 11.80 | 2.13 | 3.76 |

| Animacy | Spanish Test Item Samples |

| Animate | Mariana está alegre porque su hijo agradeció ________ (la enfermera). ‘Mariana is joyful because her son thanked ________ (the nurse).’ |

| Inanimate | Juana está feliz porque…su hijo vio ________ (la revista). ‘Juana is happy because her son saw ________ (the magazine).’ |

| Animacy | BP Test Item Samples |

| Animate | Francisco está tranquilo porque seu filho obedeceu _______ (o médico). ‘Francisco is tranquil because his son obeyed ________ (the doctor).’ |

| Inanimate | Joana está feliz porque seu filho viu ________ (o filme). ‘Joana is happy because her son saw ________ (the film).’ |

| Animacy | Gram. | Spanish Test Item Samples |

| Animate | Gram. | Manuela está orgullosa porque… Su hijo escuchó a la profesora. |

| Ungram. | Ana está triste porque… * Su hijo empujó Ø la señora. | |

| Inanimate | Gram. | José está preocupado porque… Su hijo escuchó Ø la canción vulgar. |

| Ungram. | Beatriz está triste porque… * Su hijo empujó a la mesa. | |

| Animacy | Gram. | BP Test Item Samples |

| Animate | Gram. | Felipe está feliz porque… Seu filho viu Ø o rei. |

| Ungram. | João está furioso porque… * Seu filho insultou ao professor. | |

| Inanimate | Gram. | Cristina está surpresa porque… Seu filho admirou Ø o quadro. |

| Ungram. | Beatriz está triste porque… * Seu filho empurrou ao móvel. |

| Marking | Description | No. of Participants | Category-Based Group Object Marking of Animate Objects | Category-Based Group Object Marking of Inanimate Objects | Category-Based Group PLEP Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overextension | A-marking in most test items | n = 17 | M = 6.86/8; SD = 1.35 | M = 5.43/8; SD = 1.39 | Range = 8–50; M = 33.29; SD = 12.72 |

| Other responses | Discarded responses | n = 4 | N/A | N/A | Range = 20–43; M = 33.5; SD = 10.08 |

| Omission | No instances of DOM use | n = 15 | M = 0.00/8; SD = 0.00 | M = 0.00/8; SD = 0.00 | Range = 19–51; M = 33.6; SD = 9.26 |

| Incipient animacy-driven marking | Animacy-driven DOM with more than 4 mistakes. If participants marked inanimate objects, they marked animate objects at least twice as much. | n = 15 | M = 3.70/8; SD = 1.30 | M = 0.71/8; SD = 0.87 | Range = 11–49; M = 33.6; SD = 12.04 |

| Some non-animacy-driven marking | Objects are marked less than half the time and regardless of animacy | n = 10 | M = 2.03/8; SD = 1.48 | M = 1.70/8; SD = 1.24 | Range = 14–52; M = 34.67; SD = 12.97 |

| Almost target-like use of DOM | Animacy-driven DOM with up to 4 mistakes | n = 11 | M = 7.20/8; SD = 0.83 | M = 1.8/8; SD = 0.90 | Range = 20–55; M = 40.55; SD = 11.96 |

| Target-like use of DOM | Animacy-driven DOM | n = 2 | M = 8.00/8; SD = 0.00 | M = 0.00/8; SD = 0.00 | Range = 42–44; M = 43; SD = 1.41 |

| Verb | Animate Objects | Inanimate Objects |

|---|---|---|

| Admirar ‘admire’ | M = 0.45/1; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.19/1; SD = 0.40 |

| Agradecer ‘thank’ | M = 0.63/1; SD = 0.49 | M = 0.23/1; SD = 0.43 |

| Empujar ‘push’ | M = 0.45/1; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.22/1; SD = 0.42 |

| Escuchar ‘listen’ | M = 0.56/1; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.30/1; SD = 0.46 |

| Insultar ‘insult’ | M = 0.53/1; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.19/1; SD = 0.40 |

| Obedecer ‘obey’ | M = 0.60/1; SD = 0.49 | M = 0.32/1; SD = 0.47 |

| Tocar ‘touch’ | M = 0.43/1; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.25/1; SD = 0.44 |

| Ver ‘see’ | M = 0.45/1; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.19/1; SD = 0.40 |

| Verb | Animate Objects | Inanimate Objects |

|---|---|---|

| Admirar ‘admire’ | M = 0.30/1; SD = 0.48 | M = 0.10/1; SD = 0.32 |

| Agradecer ‘thank’ | M = 0.50/1; SD = 0.53 | M = 0.11/1; SD = 0.33 |

| Empujar ‘push’ | M = 0.20/1; SD = 0.42 | M = 0.13/1; SD = 0.35 |

| Escuchar ‘listen’ | M = 0.11/1; SD = 0.33 | M = 0.33/1; SD = 0.50 |

| Insultar ‘insult’ | M = 0.30/1; SD = 0.48 | M = 0.29/1; SD = 0.49 |

| Obedecer ‘obey’ | M = 0.33/1; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.30/1; SD = 0.48 |

| Tocar ‘touch’ | M = 0.13/1; SD = 0.35 | M = 0.20/1; SD = 0.42 |

| Ver ‘see’ | M = 0.11/1; SD = 0.33 | M = 0.22/1; SD = 0.44 |

| Grammaticality | Animacy | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Grammatical | Animate | M = 4.26/5; SD = 1.04 |

| Grammatical | Inanimate | M = 4.15/5; SD = 1.06 |

| Ungrammatical | Animate | M = 3.50/5; SD = 1.33 |

| Ungrammatical | Inanimate | M = 3.56/5; SD = 1.34 |

| Verb | Animate Objects | Inanimate Objects |

|---|---|---|

| Admirar ‘admire’ | M = 0.10/1; SD = 0.30 | M = 0.04/1; SD = 0.21 |

| Agradecer ‘thank’ | M = 0.56/1; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.13/1; SD = 0.34 |

| Empurrar ‘push’ | M = 0.06/1; SD = 0.24 | M = 0.01/1; SD = 0.12 |

| Escutar ‘listen’ | M = 0.18/1; SD = 0.38 | M = 0.19/1; SD = 0.40 |

| Insultar ‘insult’ | M = 0.13/1; SD = 0.34 | M = 0.10/1; SD = 0.30 |

| Obedecer ‘obey’ | M = 0.56/1; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.36/1; SD = 0.48 |

| Tocar ‘touch’ | M = 0.10/1; SD = 0.30 | M = 0.03/1; SD = 0.18 |

| Ver ‘see’ | M = 0.03/1; SD = 0.17 | M = 0.11/1; SD = 0.32 |

| Grammaticality | Animacy | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Grammatical | Animate | M = 4.40/5; SD = 0.86 |

| Grammatical | Inanimate | M = 4.49/5; SD = 0.79 |

| Ungrammatical | Animate | M = 3.77/5; SD = 1.36 |

| Ungrammatical | Inanimate | M = 3.44/5; SD = 1.45 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López Otero, J.C.; Jimenez, A. Productive Vocabulary Knowledge Predicts Acquisition of Spanish DOM in Brazilian Portuguese-Speaking Learners. Languages 2022, 7, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7040273

López Otero JC, Jimenez A. Productive Vocabulary Knowledge Predicts Acquisition of Spanish DOM in Brazilian Portuguese-Speaking Learners. Languages. 2022; 7(4):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7040273

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez Otero, Julio César, and Abril Jimenez. 2022. "Productive Vocabulary Knowledge Predicts Acquisition of Spanish DOM in Brazilian Portuguese-Speaking Learners" Languages 7, no. 4: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7040273

APA StyleLópez Otero, J. C., & Jimenez, A. (2022). Productive Vocabulary Knowledge Predicts Acquisition of Spanish DOM in Brazilian Portuguese-Speaking Learners. Languages, 7(4), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7040273