Exploring the Role of Phonological Environment in Evaluating Social Meaning: The Case of /s/ Aspiration in Puerto Rican Spanish

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Spanish Coda /s/

2.1. Coda /s/ Production in Puerto Rican Spanish

2.2. Social Meaning of /s/ Aspiration

2.3. The Present Study

- Does /s/ realization impact listeners’ perception of speakers of Puerto Rican Spanish? In other words, can we replicate the findings of Walker et al. (2014)?

- Does the impact of /s/ realization on speaker ratings depend on the phonological context in which the /s/ is produced (cf. Vaughn 2022b; Bender 2000)? Is the impact stronger in prevocalic environments (the relatively less common setting for [h] in Puerto Rican Spanish) or in preconsonantal environments (the relatively less common setting for [s])?

- What is the shape of participant response to different proportions of preconsonantal [s] vs. [h] realizations in a single utterance? Do we see evidence of a logarithmic response (Labov et al. 2011), a linear response (Levon and Fox 2014; Vaughn 2022a), or a flat response (Levon and Fox 2014)?

- Are any of the above effects mediated by the residential status (islander/mainlander) of the listener?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Stimuli

| (1) | Preconsonantal: Vira a la derecha, en la esquina a la izquierda. |

| ‘Turn right, at the corner to the left.’ | |

| (2) | Prevocalic: Y cuando llegues a la avenida de la República, vas a virar a la derecha. |

| ‘When you arrive at Avenida de la República, you will turn right.’ |

| 1. | zero | [s]: E[h]tá entre el ho[h]pital y una e[h]cuela elemental. |

| 2. | one | [s]: E[s]tá entre el ho[h]pital y una e[h]cuela elemental. |

| 3. | one | [s]: E[h]tá entre el ho[s]pital y una e[h]cuela elemental. |

| 4. | one | [s]: E[h]tá entre el ho[h]pital y una e[s]cuela elemental. |

| 5. | two | [s]: E[s]tá entre el ho[s]pital y una e[h]cuela elemental. |

| 6. | two | [s]: E[s]tá entre el ho[h]pital y una e[s]cuela elemental. |

| 7. | two | [s]: E[h]tá entre el ho[s]pital y una e[s]cuela elemental. |

| 8. | three | [s]: E[s]tá entre el ho[s]pital y una e[s]cuela elemental. |

| ‘It’s between the hospital and the elementary school.’ | ||

3.2. Experimental Design

3.3. Participants

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

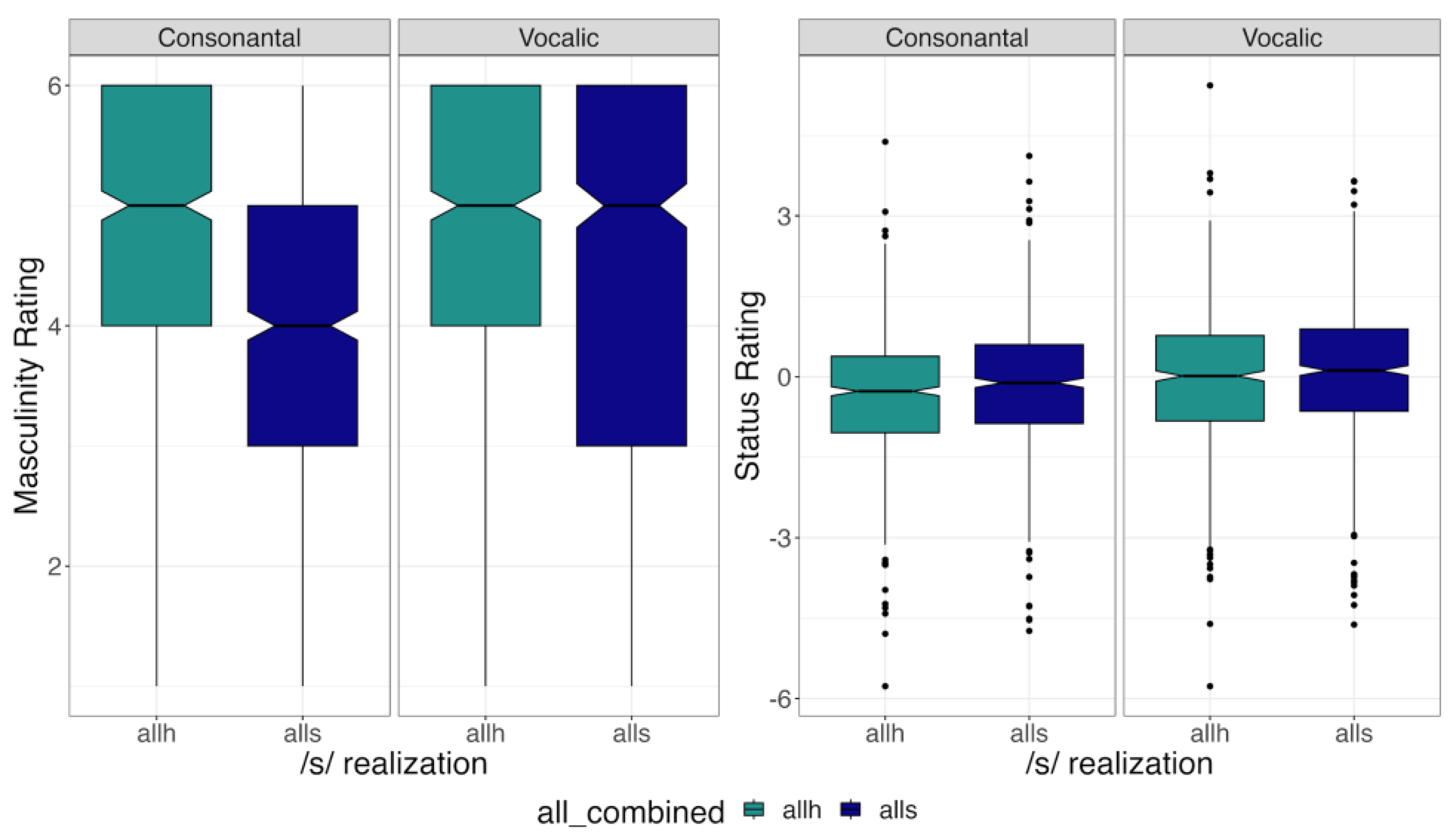

4.1. [s] vs. [h]: Replicating Walker et al. (2014)

4.2. The Effect of Phonological Environment on Ratings

4.3. Additive Effects of [s] and [h]

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Context Stimuli

| Speaker | Type | Sentence |

| 1 | Pre-C | Y a la derecha, en la esquina a la derecha está. To the right, it’s on the corner to the right. |

| Pre-V | Y luego vas a ver el número diez al lado del banco. And then you will see number ten next to the bank. | |

| 2 | Pre-C | Va a estar al lado del hospital. It’s going to be next to the hospital. |

| Pre-V | Sigue directo, llegas al final de la calle Bolívar y vas a encontrar… Continue straight, you will arrive at the end of Bolívar street and you will find… | |

| 3 | Pre-C | Eh, vira a la derecha, en la esquina a la izquierda. Turn right, at the corner to the left. |

| Pre-V | Y cuando llegues a la avenida de la República, vas a virar a la derecha. And when you arrive at Avenida de la República, you will turn right. |

Appendix A.2. Additive Stimuli

| Speaker | Sentence |

| 1 | Está entre el hospital y una escuela elemental. It’s between the hospital and the elementary school. |

| 2 | Y va a estar entre, en, a la derecha, en la esquina de la Avenida de la República y Colón, al lado del hospital. And it’s going to be between, on, to the right, on the corner of Avenida de la República and Colón, next to the hospital. |

| 3 | A la izquierda, queda entre la escuela y el hospital. To the left, it’s in between the school and the hospital. |

| 4 | Y luego de pasar el hospital a tu izquierda, está el lugar. And after passing the hospital on your left, there is the place. |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Attention Checks

- (a)

- 5 o más veces

- (b)

- 2–4 veces

- (c)

- 1 vez

- (d)

- nunca

- (a)

- 5+ times

- (b)

- 2–4 times

- (c)

- 1 time

- (d)

- 0 times

- (a)

- nunca

- (b)

- a veces

- (c)

- a menudo

- (a)

- Never

- (b)

- Sometimes

- (c)

- Often

- (a)

- verdadero

- (b)

- falso

- (a)

- True

- (b)

- False

Appendix B.2. Language Screening

| 1 | This logarithmic response was replicated by looking at the same variable and using the same paradigm for US listeners by Wagner and Hesson (2014) but not by Vaughn (2022a), who instead found a more linear effect of the proportion of alveolar tokens on speaker ratings. |

| 2 | It is also worth noting that work in speech production suggests that speakers account for linguistic factors (word frequency, neighborhood density, and lexical constraints) in stylistic choices (Hay et al. 1999; Munson 2007; Lin and Chan 2022). |

| 3 | Participants in Bender’s study were asked to evaluate speakers in terms of how good they thought the person’s job was and how educated, likable, confident, polite, reliable, and comical they sounded. The presence or absence of copula most impacted ratings of education and job, such that copula presence led to impressions that the speaker was more educated and had a better job, and had the least impact on comical ratings. However, in the analysis examining the impact of the following grammatical category, Bender looks at any scale where a given listener was impacted by copula presence/absence. |

| 4 | Most sociolinguistic studies (Alba 2000; Cedergren 1973; Guitart 1976; Lipski 1985; Lynch 2009; among many others) divide /s/ realizations into these three categories ([s], [h], and [∅]). Studies that take into account more phonetic detail note that other weakened variants exist. For example, aspiration is often voiced ([ɦ]) (Luna 2010). Gemination of the following consonant is common, particularly in Cuban Spanish (estar > [et.taɾ]) (Terrell 1979). /s/ is also sometimes realized as a glottal stop [ʔ], particularly before vowels (vamos a > [b a.moʔ.a]), but has also been documented before consonants in Puerto Rican Spanish (Mohamed and Muntendam 2020). |

| 5 | Unlike aspiration, deletion is socially stratified in many /s/-weakening dialects (Alfaraz 2000; Lafford 1986; Lynch 2009) and is thus often stigmatized, including in Puerto Rican Spanish (Valentín-Márquez 2006). |

| 6 | It is important to note here the interaction between phonological context, word position, and syllable stress in our stimuli. All of the preconsonantal tokens of /s/ are word-internal and are mostly followed by stressed vowels, with the exception of hospital. On the other hand, the prevocalic tokens of /s/ are word-final and followed by unstressed vowels. In his comparison of /s/ aspiration rates in several dialects, Lipski (1985) found minimal differences between aspiration in word-medial versus word-final preconsonantal /s/. He did find a difference between aspiration in prevocalic contexts based on stress (more aspiration before an unstressed vowel); however, this fact should not impact greatly our findings, as the prevocalic tokens included in the stimuli are homogenous in terms of stress (all before unstressed vowels). |

| 7 | As will be explained in Section 3.3, listeners completing the survey through Positly also filled out attention checks and a language screening before completing the demographic questionnaire. |

| 8 | One difference between the questions in Walker et al. (2014) and the present study is that, here, most of the participants were not asked to evaluate the speakers’ sexuality. After the first round of data collection, we decided to take this social characteristic out of the survey given that two Puerto Rican informants mentioned that this could be a sensitive question to ask. In this paper, we do not analyze the responses of the 56 participants who did answer this question about speakers. |

| 9 | Both Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy suggested that our data was adequate for factor analysis. We used an oblique rotation method (oblimin), seeing as it did not assume our variables were uncorrelated, and in our data, it resulted in the simplest structure (for a discussion, see Brown 2009). |

| 10 | We did also run models using second and third factors instead of the raw pleasantness and masculinity ratings but did not find qualitatively different results. |

| 11 | If we substitute listener residency (a categorical factor based on where participants currently lived) with the proportion of their life they have spent in Puerto Rico (a numeric factor), it makes no qualitative difference in the models—the proportion of life lived on the island is only a significant factor in the model presented in Table 5. This is likely because listener residency and proportion of life in PR are correlated (see Table 1). At the editors’ request, we conducted a post hoc test of whether listener age or listener gender has any impact on /s/ ratings. We find a main effect of listener age on masculinity ratings, such that older speakers are more likely to rate speakers as more masculine sounding. Critically, this is regardless of /s/ realization, and so it is not of particular interest in our study. The inclusion of listener age in our masculinity models does not qualitatively change our results regarding /s/ realization. We find no effect of listener gender on ratings. |

| 12 | We confirmed this by changing the order of the factor levels of phonological context in the model presented in Table 4 (such that the /s/ realizations default to prevocalic environments): /s/ realization was no longer significant as a main effect. |

References

- Alba, Orlando. 2000. Nuevos aspectos del español en Santo Domingo. Santo Domingo: Librería la Trinitaria. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaraz, Gabriela. 2000. Sound Change in a Regional Variety of Cuban Spanish. Ph.D. dissertation, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Arias Alvarez, Alba. 2018. Rhotic Variation in the Spanish Spoken by Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico and Western Massachusetts. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bandalos, Deborah L., and Meggen R. Boehm-Kaufman. 2008. Four common misconceptions in exploratory factor analysis. In Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends. Edited by Charles E. Lance and Robert J. Vandenberg. London: Routledge, pp. 81–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, Emily. 2000. Syntactic Variation and Linguistic Competence: The Case of AAVE Copula Absence. Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, James Dean. 2009. Choosing the right number of components or factors in PCA and EFA. Shiken: JALT Testing & Evaluation SIG Newsletter 13: 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Calles, Ricardo, and Paola Bentivoglio. 1986. Hacia un perfil sociolingüístico del habla de Caracas. In Actas del II Congreso Internacional sobre el Español de América. Edited by José G. Moreno de Alba. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 111–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Richard. 2005. Aging and gendering. Language in Society 34: 23–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2009. The nature of sociolinguistic perception. Language Variation and Change 21: 135–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cedergren, Henrietta. J. 1973. On the nature of variable constraints. In New Ways of Analyzing Variation in English. Edited by Charles-James N. Bailey and Roger W. Shuy. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2019a. Caribeño or mexicano, profesionista or albañil?: Mexican listeners’ evaluations of /s/ aspiration and maintenance in Mexican and Puerto Rican voices. Sociolinguistic Studies 12: 367–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2019b. The sociophonetic perception of heritage Spanish speakers in the United States: Reactions to labiodentalized <v> in the speech of native and heritage voices. In Recent Advances in the study of Spanish Sociophonetic Perception. Edited by Whitney Chappell. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 239–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2021. Heritage Mexican Spanish Speakers’ Sociophonetic Perception of /s/ Aspiration. Spanish as a Heritage Language, 167–97. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2012. Three waves of variation study: The emergence of meaning in the study of sociolinguistic variation. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erker, Daniel G., and Madeline Reffel. 2021. Describing and analyzing variability in Spanish /s/: A case study of Caribbeans in Boston and New York City. In Sociolinguistic Approaches to Sibilant Variation in Spanish. Edited by Eva Núñez-Méndez. London: Routledge, pp. 131–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh-Johnson, Elka. 2005. Mexiqueño? A case study of dialect contact. Penn Working Papers in Linguistics 11: 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Guitart, Jorge M. 1976. Markedness and a Cuban Dialect of Spanish. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, Gregory R., Jennifer Hay, and Abby Walker. 2008. Phonological, lexical, and frequency factors in coronal stop deletion in Early New Zealand English. Paper presented at Laboratory Phonology 11, Wellington, New Zealand, June 30. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, Robert M. 2001. The Sounds of Spanish: Analysis and Application (with Special Reference to American English). Somerville: Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, Jennifer, Stefanie Jannedy, and Norma Mendoza-Denton. 1999. Oprah and /ay/: Lexical Frequency, Referee Design and Style. In Proceedings of the 14th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. Edited by John Ohala. Berkeley: University of California, pp. 1389–92. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William, Sharon Ash, Maya Ravindranath, Tracey Weldon, Maciej Baranowski, and Naomi Nagy. 2011. Properties of the sociolinguistic monitor. Journal of Sociolinguistics 15: 431–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, William. 1972. Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William. 1994. Principles of Linguistic Change. vol. 1: Internal Factors. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lafford, Barbara. 1986. Valor diagnóstico-social del uso de ciertas variantes de /s/ en el español de Cartagena, Colombia. In Estudios sobre la fonología del español del Caribe. Edited by Rafael A. Nuñez Cedeño, Iraset Páez Urdaneta and Jorge M. Guitart. Caracas: Ediciones La Casa de Bello, pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Levon, Erez, and Isabelle Buchstaller. 2015. Perception, cognition, and linguistic structure: The effect of linguistic modularity and cognitive style on sociolinguistic processing. Language Variation and Change 27: 319–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levon, Erez, and Sue Fox. 2014. Social Salience and the Sociolinguistic Monitor: A Case Study of ING and TH-fronting in Britain. Journal of English Linguistics 42: 185–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Yuhan, and Marjorie K. M. Chan. 2022. Linguistic constraint, social meaning, and multi-modal stylistic construction: Case studies from Mandarin pop songs. Language in Society 51: 603–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipski, John M. 1983. La norma culta y la norma radiofónica: /s/ y /n/ en español. Language Problems and Language Planning 7: 239–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipski, John M. 1985. Reducción de /s/ y/ n/ en el español isleño de Luisiana: Vestigios del español canario en Norteamérica. Revista de Filología de la Universidad de La Laguna 4: 125–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John M. 1994. Latin American Spanish. New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John M. 1995. Blocking of Spanish /s/-aspiration: The vocalic nature of consonantal disharmony. Hispanic Linguistics 6: 287–327. [Google Scholar]

- López Morales, Humberto. 1983. Lateralización de /r/ en el español de Puerto Rico: Sociolectos y estilos. In Philologica hispaniensia in honorem Manuel Alvar. Tomo I. Madrid: Gredos, pp. 387–98. [Google Scholar]

- Luna, Kenneth V. 2010. The Spanish of Ponce, Puerto Rico: A Phonetic, Phonological, and Intonational Analysis. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Andrew. 2009. A sociolinguistic analysis of final /s/ in Miami Cuban Spanish. Language Sciences 31: 766–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, Sara. 2009. Socially Stratified Phonetic Variation and Perceived Identity in Puerto Rican Spanish. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, MN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, Sherez, and Antje Muntendam. 2020. The use of the glottal stop as a variant of /s/ in Puerto Rican Spanish. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 13: 391–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, Chris, and Emma Moore. 2018. Evaluating S(c)illy voices: The effects of salience, stereotypes, and co-present language variables on real-time reactions to regional speech. Language 94: 629–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munson, Benjamin. 2007. Lexical characteristics mediate the influence of talker sex and sex typicality on vowel-space size. In Proceedings of the 16th International Congress on Phonetic Sciences. Edited by Jürgen Trouvain and William J. Barry. Saarbrücken: University of Saarland, pp. 885–88. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, Erin, and Kim Potowski. 2016. Phonetic accommodation in a situation of Spanish dialect contact: Coda /s/ and /r/ in Chicago. Studies in Hispanic & Lusophone Linguistics 9: 355–99. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2019. Facts on Hispanics of Puerto Rican origin in the United States, 2017. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/fact-sheet/u-s-hispanics-facts-on-puerto-rican-origin-latinos/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Pharao, Nicolai, and Marie Maegaard. 2017. On the influence of coronal sibilants and stops on the perception of social meanings in Copenhagen Danish. Linguistics 55: 1141–67. [Google Scholar]

- Pharao, Nicolai, Marie Maegaard, Janus S. Møller, and Tore Kristiansen. 2014. Indexical meanings of [s+] among Copenhagen youth: Social perception of a phonetic variant in different prosodic contexts. Language in Society 43: 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Podesva, Robert J., Jermay Reynolds, Patrick Callier, and Jessica Baptiste. 2015. Constraints on the social meaning of released /t/: A production and perception study of U.S. politicians. Language Variation and Change 27: 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplack, Shana. 1979. Function and Process in Variable Phonology. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Poplack, Shana. 1980. Deletion and disambiguation in Puerto Rican Spanish. Language 56: 371–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, Dennis R. 1999. Handbook of Perceptual Dialectology: Volume 1. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos Pellicia, Michelle F. 2012. Retention and deletion of /s/ in final position: The disappearance of /s/ in the Puerto Rican Spanish spoken in one community in the US Midwest. Southwest Journal of Linguistics 31: 161–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Pellicia, Michelle F. 2007. Lorain Puerto Rican Spanish and ‘r’ in three generations. In Selected Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics. Edited by Jonathan Holmquist, Gerardo A. Lorenzino and Lotfi Sayah. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner, Meghan, Seung K. Kim, Ed King, and Kevin B. McGowan. 2014. The socially weighted encoding of spoken words: A dual-route approach to speech perception. Frontiers in Psychology 4: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Terrell, Tracy D. 1978. La aspiración y elisión de /s/ en el español porteño. Anuario de Letras 16: 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Terrell, Tracy D. 1979. Final /s/ in Cuban Spanish. Hispania 62: 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrell, Tracy D. 1981. Diachronic reconstruction by dialect comparison of variable constraints: S-aspiration and deletion in Spanish. Variation Omnibus, 115–24. [Google Scholar]

- Terrell, Tracy D. 1982. Current trends in the investigation of Cuban and Puerto Rican phonology. In Spanish in the United States: Sociolinguistic Aspects. Edited by Jon Amastae and Lucía Elías-Olivare. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2020. Quick Facts: Puerto Rico. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/PR (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Valentín-Márquez, Wilfredo. 2006. La oclusión glotal y la construcción lingüística de identidades sociales en Puerto Rico. In Selected Proceedings of the 9th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Nuria Sagarra and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 326–41. [Google Scholar]

- Valentín-Márquez, Wilfredo. 2020. The sociolinguistic distribution of Puerto Rican Spanish /r/ in Grand Rapids, Michigan. In Dialects from Tropical Islands: Caribbean Spanish in the United States. Edited by Wilfredo Valentín-Márquez and Melvin González-Rivera. London: Routledge, pp. 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, Charlotte, and Tyler Kendall. 2018. Listener sensitivity to probabilistic conditioning of sociolinguistic variables: The case of (ING). Journal of Memory and Language 103: 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, Charlotte. 2022a. The role of internal constraints and stylistic congruence on a variant’s social impact. Language Variation and Change 34: 331–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, Charlotte. 2022b. What carries greater social weight, a linguistic variant’s local use or its typical use? In Proceedings of the 44th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Edited by Jennifer Culbertson, Andrew Perfors, Hugh Rabagliati and Véronica Ramenzoni. Berkeley: University of California, pp. 512–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Suzanne E., and Ashley Hesson. 2014. Individual sensitivity to the frequency of socially meaningful linguistic cues affects language attitudes. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 33: 651–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Abby, Christina García, Yomi Cortés, and Kathryn Campbell-Kibler. 2014. Comparing social meanings across listeners and speaker groups: The indexical field of Spanish /s/. Language Variation and Change 26: 169–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherholtz, Kodi, Kathryn Campbell-Kibler, and T. Florian Jaeger. 2014. Socially-mediated syntactic alignment. Language Variation and Change 26: 387–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Island Residents | Mainland Residents | |

|---|---|---|

| No. Total | 161 | 73 |

| No. Born (PR/US/Other) | 151/9/1 | 54/19/0 |

| Mean Age * (range) | 35.5 (18–67) | 35.6 (18–72) |

| Gender (Female/Male/Non-Binary) | 94/67/0 | 43/28/2 |

| Proportion of life in PR * (range) | 0.97 (0.14–1) | 0.45 (0–0.96) |

| Estimate | SE | t Value | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.28508 | 0.25747 | 16.643 | <0.001 |

| Variant = [s] | −0.16797 | 0.04727 | −3.553 | <0.001 |

| Estimate | SE | t Value | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.17216 | 0.10648 | −1.617 | 0.1950 |

| Variant = [s] | 0.13171 | 0.04727 | 2.786 | 0.0054 |

| Estimate | SE | t Value | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.52999 | 0.26459 | 17.121 | 0.002 |

| Variant = [s] | −0.19852 | 0.05650 | −3.514 | <0.001 |

| Type = Vocalic | −0.11540 | 0.05671 | −2.035 | 0.042 |

| Variant = [s]: Type = Vocalic | 0.17323 | 0.08011 | 2.162 | 0.031 |

| Estimate | SE | t Value | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.35640 | 0.11028 | −3.232 | 0.015 |

| Variant = [s] | 0.14377 | 0.03982 | 3.611 | <0.001 |

| Residence = Puerto Rico | 0.02448 | 0.08958 | 0.273 | 0.785 |

| Type = Vocalic | 0.08802 | 0.07141 | 1.232 | 0.218 |

| Residence = Puerto Rico: Type = Vocalic | 0.28463 | 0.08603 | 3.309 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García, C.; Walker, A.; Beaton, M. Exploring the Role of Phonological Environment in Evaluating Social Meaning: The Case of /s/ Aspiration in Puerto Rican Spanish. Languages 2023, 8, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030186

García C, Walker A, Beaton M. Exploring the Role of Phonological Environment in Evaluating Social Meaning: The Case of /s/ Aspiration in Puerto Rican Spanish. Languages. 2023; 8(3):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030186

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía, Christina, Abby Walker, and Mary Beaton. 2023. "Exploring the Role of Phonological Environment in Evaluating Social Meaning: The Case of /s/ Aspiration in Puerto Rican Spanish" Languages 8, no. 3: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030186

APA StyleGarcía, C., Walker, A., & Beaton, M. (2023). Exploring the Role of Phonological Environment in Evaluating Social Meaning: The Case of /s/ Aspiration in Puerto Rican Spanish. Languages, 8(3), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030186