Abstract

Perceptual sociophonetic work on Guatemalan Spanish has demonstrated that listeners are more likely to link male voices with traditional Maya clothing, the traje típico, when their speech includes features of Mayan-accented Spanish. However, as Maya women are more likely than men to wear the traje típico, this matched-guise study investigates native Guatemalans’ perceptions of Mayan-accented Spanish produced by female voices. The results demonstrate that guises with features of Mayan-accented Spanish were more likely to have traje típico as a response than guises without these features. When compared to the previous studies with male-voiced guises, the findings suggest an interaction between gender and Mayan-accented Spanish. Traje típico responses were more common for female-voiced guises than male-voiced guises and occurred at the highest rate among female-voiced guises with features of Mayan-accented Spanish. Thus, gendered and cultural practices are reflected in the indexical fields of Mayan-accented Spanish in Guatemala, regardless of the gender or ethnicity of the listener. That is, the visual body–language link is significantly more essentialized for the identity of a woman than for the identity of a man in Guatemala, suggesting that gendered stereotypes, language ideologies, and embodied practices mutually reinforce one another in the collective consciousness of the region.

1. Introduction

Within ’s () third wave of sociolinguistics, single linguistic variables are seen as capable of indexing various social meanings beyond the variable itself. In other words, any unique linguistic variable may represent the “embodiment of ideology in linguistic form” (), as linguistic variation has been shown to index multiple facets beyond language: race, ethnicity, intelligence, social class, emotional state, among many others. This “constellation of ideologically related meanings” (), or indexical field, is constantly evolving; different extra-linguistic variables, e.g., cultural practices, gender roles, etc., influence what social meanings may be indexed by a linguistic variable among a particular group. Conversely, the same linguistic variable may have an entirely different indexical field in another context. In fact, recent studies on Spanish have shown how single linguistic variables demonstrate “local constructions of meaning in variation” () (see edited volumes such as and for some recent examples).

Aside from linguistic variables, “material style”, i.e., clothing and other types of adornment (), is also a prominent indexer of social meaning and identity among different groups. For example, in her study of high school girls in California, () found that certain fashion choices indexed belonging to specific social groups and that some students deliberately chose to emulate some of those fashion choices in order to claim aspects of the other social group’s identity as their own. Specifically, some female students that identified as preppy chose to copy the pants style of the ‘new wavers’ social group in order to be perceived as both preppy and independent, while they avoided other new waver fashion styles that they deemed to index social meanings that they did not desire in the creation of their own identities. ’s () work among Latina youth gangs in California describes many deliberate choices of material style and what they index, such as specific hair dye and clothing colors for different gangs, and the use of long eyeliner as a marker of the intention and willingness to fight.

Of particular interest to this study is the relationship between different linguistic variables and material style, what () calls “visual body-language links”. For example, ’s () research not only demonstrates the indexing of gang membership via clothing, hair, and eyeliner, but also by the use of phonetic variables like the raising of /ɪ/ to [i] as in sick [sik] and the fortition of /θ/ to [t̪] as in things [t̪iŋz]. In Beijing, China, those that identify as part of a group with high levels of consumerism, known locally as ‘smooth operators’, index this identity both in terms of more elegant clothing and lifestyles and significantly higher rates of rhotacization, the addition of /ɻ/ to the end of a syllable, than non-smooth operators (). Furthermore, the connection between linguistic features and material style can go hand-in-hand with the loss of a culture and its language. This is exemplified in the small town of Oberwart, Austria; young women who wish to present a more urban identity are not only beginning to speak more German than Hungarian, but they are also changing their ways of dressing and grooming to be more German-like, as both Hungarian clothing and speaking Hungarian index a peasant lifestyle ().

The present study analyzes the indexical relationship between clothing and linguistic features among a minority population in Guatemala: the indigenous Maya. As with most indigenous cultures and their languages in the Americas, the Maya have endured centuries of oppression and attempts at extermination by different regimes, as they were deemed socially inferior to the Spanish-speaking upper classes (). Nonetheless, the somewhat recent revitalization efforts, known locally as the ‘Maya movement’, have been successful in their attempts to at least slow down this cultural and linguistic loss. Today, about 42% of the total population in Guatemala self-identify as Maya (). At the forefront of the Maya movement is the documentation and preservation of Mayan languages, as the ability to speak one of the approximately 21 Mayan languages in the country is generally considered to be the single most important aspect of Maya identity (). This movement has included government-level recognition of Mayan languages in both the 1996 Peace Accords and the 2003 Law of National Languages, although both fell short of granting any Mayan language official status in Guatemala ().

Aside from speaking a Mayan language, the use of traditional Mayan clothing is the second most important aspect of Maya identity, and the most important visual one (; ; , ; among many others). The hand-made clothing, commonly referred to as the traje típico, greatly contrasts from more western styles of clothing used by Ladinos (non-Mayas in Guatemala), and the elaborate hand-stitched and colorful patterns often hold significant meanings that vary from town to town. The female traje típico from the municipality of Cantel is illustrated and described in the article from the Guatemalan newspaper El quetzalteco seen in Figure 1. The most commonly worn items of the traje típico are el huipil, the blouse, and el corte, the skirt, which is not like western-style skirts with sewn-in waists; rather, a hand-woven piece of fabric is wrapped around the body and held in place by another piece of belt-like fabric, la faja. The other articles shown in Figure 1, the cinta ‘headdress’, the chachal or collar ‘necklace’, and the perraje ‘shawl’, are typically reserved for more formal use. In the Cantel traje típico in Figure 1, the cinta represents the feathered serpent that is present in many Mesoamerican cultures, the perraje represents the authority of the Maya woman, the huipil denotes the blood of their ancestors, and the corte signifies Mayan altars.

Figure 1.

(). Newspaper article El traje típico es representativo de la cultura maya ‘The traje típico is representative of the Maya culture’ (13 May 2013) El quetzalteco, Prensa Libre. © Hemeroteca Prensa Libre. Used with the permission of Prensa Libre.

Given the significance of the different articles of clothing that constitute this style of dress, the traje típico has received ample attention in the ethnographic literature and is considered to be truly iconic throughout the country (; , ; , ; among many others). As such, there are many nuanced layers to the use of the traje típico among the Maya in Guatemala, more than can adequately be addressed here. For example, for many Ladinos the traje típico represents antiquated cultural practices and is a sign of what is impeding progress on a national level. As mentioned above, the traje típico varies from town to town; the newspaper article in Figure 1 is only one of a series of articles published by El quetzalteco that highlight different towns’ trajes. However, the different practices of the Maya and the meanings of their distinct trajes are often erased in the Ladinos’ conflation of them into a single Maya ethnicity and a single traje típico that is a symbol of what the Ladino wants it to represent: a mark of the poor Indian whose only value is financial exploitation among tourists (; ).

In spite of the Ladinos’ discrimination towards them, the continued day-to-day use of the traje típico demonstrates a sense of pride and even resistance among the Maya. For example, the newspaper article in Figure 1 quotes the woman in the photograph as saying, “wearing the traje represents respect. It is a privilege, since it allows us to make the history, culture, and richness of our country known” (). In other words, representing one’s own Maya identity is a choice. Some argue that, as there are no longer many significant differences between the Maya and Ladinos in terms of phenotype, a Maya may pass as Ladino by speaking Spanish and using Ladino or westernstyle clothing (; ; ). Therefore, a Maya must consciously decide to display their Maya identity via language and clothing in public. In an investigation of language and cultural attitudes among bilinguals of Spanish and the Mayan language K’iche’ (also spelled K’ichee’/Quiché) from the municipalities of Nahualá and Cantel, several participants saw the loss of language and the traje típico as the biggest examples of abandonment of the K’iche’ culture, as exemplified in 1–3 ():

(1) Ri kek’ix la’ kech’aw pa qach’ab’al, chuq kek’ix la’ kakikoj le qajastaq.

‘They [the youth] are ashamed of our language, and they are also ashamed to use our traje típico.’

(2) Donde vayamos, debemos de representar nuestra cultura sin importar con quienes estemos, debemos de vestirnos tal como nuestros abuelos lo hacían sin avergonzarnos de nuestro traje, sin avergonzarnos de nuestro idioma.

‘Wherever we go, we should represent our culture no matter who we are with, we should dress as our grandparents dressed without shame of our traje, without shame of our language.’

(3) In kink’oxomaj chi kek’ix la’ chech kakikoj chi le qajastaq, ma k’or k’o na’, le, la’ le a’mu’sab’ e señorayib’ keyoq’on che le qajastaq y xa je la’ jun kak’ixik. Par are k’u le chwech in, xaq si na kink’ix ta wi, jacha chech taq le qatzij.

‘I think that they [the youth] are embarrassed to use our trajes, because at times the Ladinos and Ladinas make fun of our traje típico and that’s why they get embarrassed. But I never feel embarrassed [about our traje] or about our language.’

Nevertheless, the Maya have constant interactions with Ladinos and Ladino culture, which are almost always in Spanish. As such, the Maya have a complicated history with the Spanish language; it represents both the language of their colonizers and oppressors and the key to protection from discrimination from Ladinos and advancement within this same society. In (), of the 162 K’iche’-Spanish bilinguals interviewed, not a single participant expressed negative attitudes towards the K’iche’ language or culture, but their attitudes towards Spanish demonstrated significant variation. Very few bilinguals in this study wanted to be seen as part of the Spanish-speaking world or to even be considered a Spanish speaker. Those that did predominately remarked that it was okay to be seen as Spanish speakers as long as it was not at the expense of their Maya identity, as in (4) ():

(4) Nabe’ rajawaxik kaketa’ maj le qas qach’ab’al ma xa je ri’ kaqaya unimal uq’ij le kich’ab’al ri e qati’t qamam, Par chuq sib’alaj rajawaxik le kaxlantzij ma are wa’ kutob’ej wi rib’ ri mayab’ winaq chikiwach le kaxlan taq winaq, ma we jun na reta’m taj sib’alaj kab’ananex chech rumal la’ kinchomaj chi rajawaxik le keb’ ch’ab’al kak’ut chikiwach le ak’alab’ on e nimaq winaq.

‘First it is necessary to learn our language in order to give importance to the language of our ancestors, but the Spanish language is very necessary for the Maya people in order to be able to defend themselves from Ladino people, if we do not learn it, we will have many pains and difficulties. Because of this, I think that it is necessary to teach both languages to children and adults.’

However, even if the Maya speak Spanish, they may still be subject to prejudice and discrimination by Ladinos and other Maya according to how they speak Spanish. Given the centuries of contact between Spanish and Mayan languages in Guatemala, the transfer of linguistic features between the languages is common (). Historically, the social perceptions of using Mayan linguistic features in Spanish, or Mayan-accented Spanish, were, unsurprisingly, unfavorable and prescriptive in nature; the 19th century Guatemalan philologist () described it as containing “innumerable vulgarisms that offend good taste at every step”. However, there remain few studies that analyze the social perceptions of features of Mayan-accented Spanish in the context of Guatemala and how they may index stereotypical characteristics of Maya identity, such as wearing a traje típico.

The two features of Mayan-accented Spanish analyzed in this study are phonetic in nature. The first is the apocope, or deletion, of word-final unstressed vowels: /ˈkasa/ → [ˈkas] ‘house’. In many Mayan languages, particularly those spoken in Guatemala, stress is fixed in word-final position (). As such, many early Spanish loan words in Mayan languages were phonologically adapted to follow this pattern, e.g., /esˈpexo/ → /esˈpeχ/ ‘mirror’ in K’iche’ (). This process of apocope occurs in the Spanish of some Spanish–Mayan bilinguals, e.g., /seˈmana/ → [seˈman] ‘week’, /ˈsinko/ → [ˈsiŋk] ‘five’ (). The second feature is the fortition of the voiceless labiodental fricative /f/ to the voiceless bilabial stop [p]. As no Mayan language has /f/ (), it was adapted to /p/ in Spanish loan words in Mayan languages, e.g., /kaˈfe/ → /kaˈpe/ ‘coffee’ in K’iche’ (), and /f/ fortition has been reported in Mayan-accented Spanish in Guatemala by some scholars (; ; ). Even so, the mentions of apocope and /f/ fortition in the previous literature are very brief. The lone quantitative analysis demonstrates that among K’iche’–Spanish bilinguals, /f/ fortition is more common among bilinguals that are more dominant in K’iche’ and that it predominantly occurs in phonological contexts that facilitate fortition ().

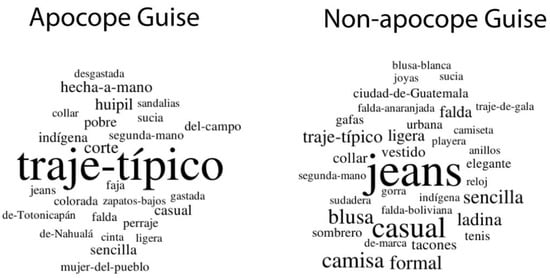

The social perceptions and indexical fields elicited by apocope and /f/ fortition in Guatemalan Spanish were explored in (, ), respectively. Both studies employed the matched-guise framework () and an open-ended question approach. The results demonstrated that the guises with apocope and /f/ fortition were significantly more stigmatized than their counterpart guises without these features. Specially, guises with these features of Mayan-accented Spanish were rated as less honest, more ignorant, and poorer than guises sans the same features. Additionally, given the aforementioned value of the traje típico to Maya identity, participants in these studies were asked to respond to the open-ended question ¿Cómo se vestiría este hablante? ‘How would this speaker dress?’ for each guise. Although it was not the most common response, the guises with apocope and /f/ fortition elicited responses of traje típico at a significantly higher rate than the guises without these features. Figure 2 illustrates an example of these results (the word cloud methodology is detailed in Section 2).

Figure 2.

Sample word cloud of the responses to the question ‘How would this speaker dress?’ for guises with apocope and without apocope. The response of traje típico is highlighted in red in both world clouds. Modified from ().

Even though the results from these perception studies of apocope () and /f/ fortition () demonstrate the direct indexical relationship between these linguistic variables and traditional Mayan clothing, both studies used male voices for the guises. This is noteworthy due to the traditional gender roles among the Maya in Guatemala, where the onus of cultural and language preservation tends to fall on Maya women. In other words, although not unique to the Maya, it is common for men to speak the national language (Spanish) more than their Mayan language and to be more accepting of different aspects of Ladino culture, whereas the women take on the responsibility of teaching children their Mayan language and maintaining other aspects of their culture (; ; , ; , ; ; ; among others). Perhaps this is most salient among the Maya in terms of the traje típico. Numerous anthropological ethnographies agree that it is more likely for women to wear the traje típico in public than men (; , ; , ; among many others); () states that “traditional clothing, which signifies indigenous identity in general, has become almost isomorphic with the Maya woman who weaves it and wears it far more consistently than men”.

The present study is motivated by this discrepancy in the use of the traje típico between Maya men and women and the results of (, ) for male-voiced guises. Furthermore, although there exists an abundance of detailed work from anthropological perspectives about the uses and meanings of the traje típico among Maya men and women, this work is based on qualitative observations. The present study performs a sociophonetic analysis employing the matched-guise methodology to provide a different framework in which to view the relationship between the traje típico, gender, Maya identity, and Mayan-accented Spanish in Guatemala. The research questions guiding this study are the following: (i) Can we replicate the findings of (, ) with different guises? In other words, will guises with apocope and /f/ fortition index the speaker as wearing a traje típico at a higher rate than guises without these linguistic features? and (ii) Is there an effect of speaker gender on the social evaluations? How do these results with female-voiced guises compare to the results of the male-voiced guises in (, )?

2. Materials and Methods

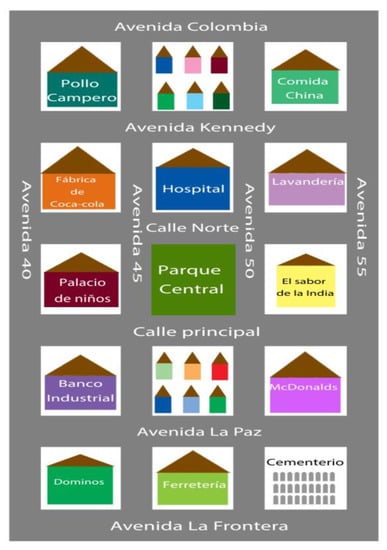

This study follows the matched-guise methodology used in (, ). Four native female speakers of Guatemalan Spanish produced the elicitation materials for the guises. These individuals were recorded in quiet rooms in Guatemala via a Marantz PMD661 solid-state digital voice recorder, digitized at 16 bits (44.a kHz), and a Shure SM10A dynamic head-mounted microphone. The same map task from the previous studies was used to elicit naturalistic speech from these four speakers. Specific target words in which apocope and /f/ fortition were more likely to occur were embedded in the map as names of streets, businesses, etc. (Figure 3). During the map task, the speakers gave instructions following specific routes on the map to another speaker with a map without the route, and this was repeated four times using four different routes.

Figure 3.

Map used in the elicitation of the stimuli.

Following this map task, each speaker was asked to read a list of controlled phrases aloud. These phrases included the same target words from the map task and each speaker was asked to read each phrase twice, once with the target word being produced with apocope or /f/ fortition and once with the target word being produced without these features. The [f] and [p] segments and the apocopated and non-apocopated words were then spliced into larger, more naturalistic sound clips from the map task. Hence, all the guises, regardless of whether they contained a feature of Mayan-accented Spanish or not, contained spliced segments in order to control for any effect of digital manipulation on the results. Distractor phrases for this study were produced following the same procedure. Six additional female speakers, two native speakers of Guatemalan Spanish, two non-native speakers (L1 English), and two native speakers of Peninsular Spanish, participated in the map and reading list tasks and had single segments from the reading task spliced into larger clips from the map task. Thus, all the sound clips presented to the participants of this study, including the distractor phrases, were digitally manipulated.

Following (), the spliced sound clips were judged by 28 native speakers of Guatemalan Spanish in a pilot study in order to ascertain how natural (i.e., digitally manipulated or not) each sound clip was using a 1–5 Likert scale. The participants listened to each clip in a random order, along with unspliced sound clips and sound clips with obvious digital manipulation. The sound clips chosen for this study received the highest ‘natural’ scores that were similar to, or higher than, the ‘natural’ scores given to the sound clips sans digital manipulation. The target sound clips used in this study are presented in (5–8).1

(5) Speaker 1: apocope

Y cruzando la Avenida Cuarenta y [ˈsiŋko/ˈsiŋk] el parque central está al lado izquierdo...

‘And crossing 45th Avenue the central park is on the left side…’

(6) Speaker 2: apocope

Dos cuadras, hacia la Avenida Cincuenta y [ˈsiŋko/ˈsiŋk] en la esquina de la lavandería…

‘Two blocks, towards 55th Avenue at the corner of the laundromat…’

(7) Speaker 3: fortition

Al llegar a la Avenida La [f/p]rontera, tomarás la avenida cincuenta…

‘Upon arriving at Border Avenue, you’ll take 50th avenue…’

(8) Speaker 4: fortition

Y después en la Avenida La Paz, para ir a dejar [f/p]lores en el cementerio…

‘And after in La Paz Avenue, to go and leave flowers in the cemetery…’

Native speakers of Guatemalan Spanish that have only resided in Guatemala were recruited to participate in this study via social media and through announcements at universities throughout the country. Only participants that did not meet these criteria, recognized the voice of a guise speaker, or did not complete the survey were excluded. The 110 participants analyzed in this study reported being from all over the country. They included 40 that identified as men and 70 that identified as women, ages 18–70 (M: 32.6, SD: 13.1). A total of 34 participants self-identified as Maya and 76 self-identified as non-Maya.

The listening survey was presented online via the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Participants were given instructions and then presented with a different sound clip per webpage. The order of the clips was quasi-randomized so that two guises from the same speaker would not appear consecutively. Additionally, the quasi-random order was counterbalanced so that half of the participants would listen to the guise with the feature of Mayan-accented Spanish from one of the speakers in (5–8) first and the other half would listen to the guise sans the Mayan-accented Spanish feature first.

Although the majority of matched-guise studies employ a numeric methodology, e.g., asking participants to rank each voice on a particular social trait, this study used a more open approach to the matched-guise method. There is, of course, no methodical approach without limitations, and matched-guises such as this study do not allow for in-depth statistical analyses of multiple variables and interactions that a more quantitative analysis would provide. Nonetheless, given the specific goal of this study, to see if apocope and /f/ fortition directly index a female speaker as wearing a traje típico, a more qualitative method provides a more precise answer. In other words, instead of asking the participants to choose from a list of options that includes traje típico as a possible item of clothing or rank how likely the speaker is to wear a traje típico, this study simply asks the open-ended question ¿Cómo se vestiría este hablante? ‘How would this speaker dress?’ for each clip.2 Although it is perhaps impossible to completely avoid priming participants in studies such as this, and the participants are primed to think about clothing in this method, at no point during this study are Maya identity, Mayan languages, the traje típico, or even Guatemala mentioned. Thus, aside from being asked about clothing in general, participants are free to answer however they wish. If a participant responds that they think a speaker would wear a traje típico, it is even stronger evidence of the indexical relationship between apocope, /f/ fortition, and a Maya identity than if similar results occurred in one of the more numeric ranking methods mentioned previously.

An additional advantage of matched-guises with open-ended questions is that they allow us to understand more of the indexical field of a single linguistic variable. In other words, “the open-ended responses to matched-guises can expand our knowledge of these fields, as participants are not confined to the overt attitudes usually found when using a rankings method” (). The studies that have employed open-ended questions in matched-guises primarily use word clouds to present their results, as in the previous studies on the perceptions of Mayan-accented Spanish (, ; see also ; ; ; ). In order to better approximate the indexical field proposed by (), the word clouds presented in the results in Section 3 display all of the participants’ answers, even those given by a single participant. As () states, a single linguistic variable may index completely opposite reactions for different listeners. As such, it is common to see answers that appear to contradict each other within these word clouds. Following (, ), the answers that appear in the word clouds are left in Spanish, as translating them to English may misrepresent what the participants intended with their answers. Furthermore, the answers were only combined into broader semantic categories in specific cases, e.g., when answers were clear synonyms such as médica and doctora ‘doctor’. When participants answered in complete sentences, only the descriptor words were used in the word clouds. For example, if a participant responded Creo que es del altiplano de Guatemala y lleva traje típico ‘I believe she’s from the Guatemalan Highlands and is wearing a traje típico’, the response was analyzed as altiplano and traje-típico. Dashes are used between words in answers with more than one word so that the online word cloud generator (worditout.com, accessed on 10 November 2022) would analyze them as single answers, providing greater clarity in the word clouds.

In the word clouds presented in the results in Section 3, the size of the word represents the frequency of that response: larger words represent more frequent answers than smaller words. In order to better understand the differences in responses across guises, the same responses were analyzed via binomial (one-tailed) tests of the distribution of frequencies of these responses. In these analyses, the guise without the feature of Mayan-accented Spanish, i.e., the non-apocope and the non-fortition guises, was used as the baseline. The binomial tests’ p-values are reported in Section 3, and the frequency tables of the proportion of the responses discussed can be found in Appendix A. If a response appeared in the word cloud of one guise but not the other, the results of the binomial tests are not reported, as they are always p < 0.001. Finally, the results were analyzed according to guise, participant gender, and whether the participant self-identified as Maya or not. Differences in responses across Gender and Ethnicity were examined via a series of binomial (one-tailed) tests according to the response traje típico by Speaker and phonetic feature, e.g., an analysis of male and female participants’ responses of traje típico to the apocope guise for Speaker 1, an analysis of Maya and non-Maya participants’ traje típico responses to the non-fortition guise for Speaker 3, etc. Nonetheless, the additional results for participant Gender and Ethnicity should be interpreted with caution, as running additional analyses increases the chances of false positives, especially when rates of traje típico are low.

3. Results

3.1. Apocope

The word clouds for the apocope and the non-apocope guises for Speakers 1 and 2 are presented in Figure 4 and Figure 5. For both speakers, traje típico was the most common response to the apocope guise, whereas jeans was the most common response to the non-apocope guise. Although traje típico was also an answer for the non-apocope guises, it was significantly more frequent in the apocope guises: 45 of 110 participants responded traje típico to Speaker 1’s apocope guise and 6 responded traje típico to the non-apocope guise (p < 0.001); for Speaker 2, there were 43 cases of traje típico for the apocope guise and 12 responses in the non-apocope guise (p < 0.001). Furthermore, additional descriptors that index Maya identity included specific pieces of the traje típico depicted in Figure 1.3 Among these are huipil (also spelled güipil) ‘woven blouse’ and corte ‘woven skirt’. Huipil and corte both appeared in Speaker 1’s apocope guise, whereas they did not appear in the non-apocope guise. For Speaker 2, huipil and corte were significantly more frequent in the apocope guise than in the non-apocope guise (p < 0.001 for both comparisons). The terms indígena ‘indigenous person’ and ladina were found among the responses as well. Indígena was more common in the apocope guise for Speaker 1 (p < 0.01) and did not appear in Speaker 2’s non-apocope guise. Ladina appeared in both non-apocope guises. The difference in ladina replies between Speaker 2’s guises was not significant (p = 0.129) and ladina did not appear as a response to Speaker 1’s apocope guise. Finally, additional answers provided by single participants to the apocope guises that index Maya identity included specific Mayan-speaking areas such as Nahualá, Quiché, and Totonicapán, the traje típico-specific necklace, chachal, and shawl, perraje, and the derogatory remark como indita de la montaña ‘like a little indigenous woman from the mountain’.

Figure 4.

Word clouds of responses to the apocope and the non-apocope guises for Speaker 1.

Figure 5.

Word clouds of responses to the apocope and the non-apocope guises for Speaker 2.

In addition to the responses to the apocope guises that directly index a Maya identity, other descriptors index a lower social class in general and may, in turn, indirectly index Maya identity. For example, responses to the apocope guise for Speaker 1 (Figure 4) included del campo ‘from the countryside’, desgastada ‘worn out (clothing)’, hecha a mano ‘handmade’, and pobre ‘poor’. Conversely, responses that imply a higher status for the non-apocope guise included answers such as de marca ‘name brand’, elegante ‘elegant’, tacones ‘high heels’, among others. The adjectives sencilla ‘simple (clothing)’ and sucia ‘dirty (clothing)’ appeared as responses to both guises at similar rates (sencilla, p = 0.426; sucia, p = 0.352). For Speaker 2 (Figure 5), responses that index a lower social status in the apocope guise included rural ‘rural’, pobre ‘poor’, and sucia ‘dirty (clothes)’, whereas the non-apocope guise elicited more responses indexing a higher social class, such as formal ‘formal (clothes)’, reloj ‘wristwatch’, enfermera ‘nurse’, and even some that indicated the opposite of a Maya identity: turista ‘tourist’ and tenis ‘tennis shoes’. Some responses that index a lower social class were used in reaction to both guises for Speaker 2, such as hecha a mano ‘handmade’ (p = 1.00).

The separate binomial tests for Gender and Ethnicity did not demonstrate any effect on the number of responses of traje típico in any guise. In other words, all of the participants, regardless of their gender or whether they identified as Maya or not, perceived the voices with apocope as more likely to wear the traje típico than non-apocope guises.4

3.2. [f] Fortition

The responses to guises with /f/ fortition from Speakers 3 and 4 are seen in Figure 6 and Figure 7. As with the apocope results, these word clouds demonstrate a clear and direct visual body–language link between /f/ fortition and the speaker wearing the traditional Mayan traje típico. Traje típico was given as an answer by 51 participants for Speaker 3’s fortition guise and by 47 participants for Speaker 4’s fortition guise, significantly more so than in the response to the non-fortition guises: seven and nine responses, respectively (p < 0.001 in both comparisons). Again, the traje típico-specific articles of clothing huipil and corte appeared more in the responses to the fortition guise than in the non-fortition guise context. Between Speakers 3 and 4, there were 31 total responses of huipil and 25 of corte. In comparison, there was only one huipil response in Speaker 4’s non-fortition guise and no responses of corte in either non-fortition guise. Indígena is seen in both fortition guises but is not found in either non-fortition guise. Similarly, ladina occurs somewhat commonly in Speaker 4’s non-fortition guise but is absent from the fortition guise. The difference between Speaker 3’s fortition and non-fortition guises for ladina responses approaches significance (p = 0.068). As with the apocope results, answers provided by single listeners illustrate the direct indexicality of /f/ fortition among the participants in this study. Mayan-speaking geographical areas mentioned include Zunil, Almolonga, Nahualá, and Patzún. Additional clothing responses include traje yucateco ‘Yucatan clothes’, perraje, and chachal.

Figure 6.

Word clouds of responses to the fortition and the non-fortition guises for Speaker 3.

Figure 7.

Word clouds of responses to the fortition and the non-fortition guises for Speaker 4.

Additional descriptors that index a lower social status for Speaker 3’s fortition guise include segunda mano ‘second hand (clothes)’, hecha a mano ‘hand-made’, pobre ‘poor’, and sucia ‘dirty’. Conversely, Speaker 3’s non-fortition guise elicited replies such as maquillaje ‘makeup’, tacones ‘high heels’, and formal ‘formal (clothing)’. Interestingly, the non-fortition guise elicited answers of del campo ‘from the countryside’, whereas the fortition guise did not. Responses of desgastada ‘worn out (clothes)’ and sencilla ‘simple (clothes)’ appeared at comparable rates across both guises (p = 1.00 and p = 0.691, respectively). For Speaker 4, the fortition guise produced strong negative comments not seen in other word clouds, including descuidada ‘sloppy, unkempt’ and descalza ‘barefoot’. Other answers that index a lower social status went beyond the question of clothing; these include caminante de ciudad ‘street wanderer’, vendedora ambulante ‘street vendor’, and problemas para hablar español ‘trouble speaking Spanish’. Speaker 4’s non-fortition guise responses were much more positive: elegante ‘elegant’, de gala ‘gala’, tacones ‘high heels’, among others. Answers found in both guises for Speaker 4 include desgastada ‘worn out (clothes)’ (p = 1.00) and formal, which was significantly more prominent in the non-fortition guise than the fortition guise (p < 0.05). Again, there were no significant effects of Gender or Ethnicity in the separate binomial tests of traje típico responses across guises.5

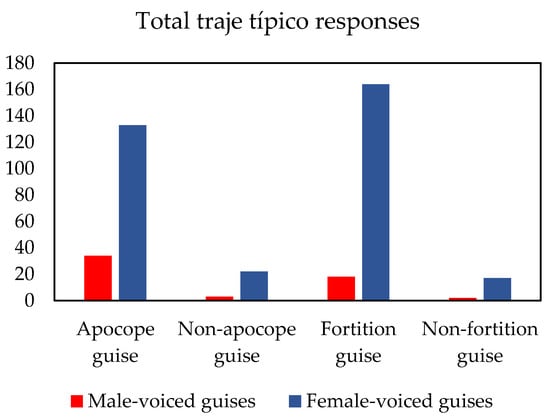

3.3. Comparison with Male-Voiced Guises

Aside from indexing a lower social status, via the proxy of lower quality clothing in general, the results from the female-voiced guises demonstrate that traditional Maya clothing is strongly indexed by both apocope and /f/ fortition. These findings parallel those found for male-voiced guises for both apocope () and /f/ fortition (). In this section, the results from the present study are compared to the results from (, ). Specifically, this section analyzes responses of traje típico and other answers that directly index Maya identity.

In all of these studies, the results analyzed were not conflated but kept separate for individual guise speakers. This was done to adhere to the matched-guise framework, as variables such as vocabulary, speaking rates, fundamental frequency, etc., that vary across speakers may influence the results if all of the guises from different speakers are combined and analyzed as a whole. However, it is not possible to avoid these conflations when comparing the results from the female-voiced guises to those of the male-voiced guises from the previous studies. In these comparisons, the results for Speakers 1 and 2 are combined for apocope and compared with the combined results of the two male guise speakers in (), and the results for Speakers 3 and 4 for /f/ fortition are combined and compared with the results of the two male-voiced guises in (). In these comparisons, all of the responses pertaining to any specific article of the traje típico were combined, i.e., responses such as huipil and corte in this study and kutin ‘male woven shirt’ in the previous studies were counted as traje típico.6

The participants in this study differ from those in (, ). As stated above, the participants in this study consisted of 110 native speakers of Guatemalan Spanish that had only lived in the country: 40 men, 70 women; 34 Maya, 76 non-Maya; ages 18–70 (M: 32.6, SD: 13.1). In both () and (), the group of participants was the same: 116 native speakers of Guatemalan Spanish that have only resided in Guatemala; 57 men, 58 women, 1 non-binary; 35 Maya, 81 non-Maya; ages 18–56 (M: 27.3, SD: 6.6). The conflation of guise results across these different groups of participants was deemed necessary in order to answer the second research question about whether there is an effect of gender on the indexical fields of these two linguistic variables of Mayan-accented Spanish. These results were also analyzed via binomial (one-tailed) tests of the distribution of frequencies of the responses with the male-voiced guises as the baseline. The frequency values (percentage rates) of these responses are reported in Appendix B.

The combined results of these studies are presented in Figure 8. These findings demonstrate that responses of traje típico are more likely to occur in reaction to female-voiced guises than male-voiced guises regardless of the presence of Mayan-accented Spanish: all four guise comparisons are significant at p < 0.001. Thus, these results suggest that it is more likely for the native Guatemalan Spanish female voices used as stimuli in this study to be perceived as Maya than the native Guatemalan Spanish male voices, with or without the features of Mayan-accented Spanish. Furthermore, the guises that directly indexed the speaker as wearing a traje típico the most were the female-voiced guises with Mayan-accented Spanish variables present. In other words, although these data are more qualitative in nature, there is, in a sense, an interaction between the female-voiced guises and the features of Mayan-accented Spanish analyzed in this study. Although both of these independent variables directly index a speaker as wearing traditional Maya clothing, the visual body–language link is strongest when they are combined.

Figure 8.

Total traje típico responses across all of the apocope/non-apocope and fortition/non-fortition guises from this study and (, ). Responses to male-voiced guises are in red and responses to female-voiced guises are in blue.

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to replicate the findings of (, ) to see if the apocope of word-final unstressed vowels and the fortition of /f/ to [p] indexed a native speaker of Guatemalan Spanish as being Maya and, in particular, wearing traditional Maya clothing. This study goes a step further by analyzing the role of gender in these indexical fields, as it compared the results from female-voiced guises to the previous results of male-voiced guises.

The first research question was whether the results found in (, ) would hold true with different guise voices. As reported in Section 3, the results of this investigation corroborate the findings of previous studies; guises with apocope and /f/ fortition index a lower social class in general and, more specifically, the traje típico. Again, it is important to note that these results provide strong evidence of the indexical relationship between a single linguistic variable, apocope or /f/ fortition, and a Maya identity, as there was no mention of anything concerning the Maya in the study and the questions were open-ended. In other words, the responses concerning Maya identity were unprimed aside from asking the participants to consider clothing in general. However, as seen in a response to Speaker 4’s fortition guise, one participant ignored the question about clothing and responded problemas para hablar español ‘trouble speaking Spanish’. This type of comment shows that the indexical field of Mayan-accented Spanish in Guatemala is significantly vaster than the specific visual body–language links explored in this paper, and the reader is referred to (, ) for a more thorough, albeit not exhaustive, review of the social meanings of these variables that extend beyond the traje típico in male speech.

Although we may assume that these specific phonetic features of Guatemalan Spanish in contact with Mayan languages are highly stigmatized, this study and (, ) are the first to empirically demonstrate this stigmatization. The previous literature that specifically discusses apocope and /f/ fortition is scarce and only acknowledges their existence (; ; ). Additionally, the ethnographies that reference Mayan-accented Spanish do so in passing, only briefly remarking on a few morphosyntactic features (, ). In general, the combined results of (, ) and this study empirically demonstrate that apocope and /f/ fortition are highly marked features that elicit stereotypes associated with the Maya in Guatemala. Following ’s () orders of indexicality, the basic n-order index of both apocope and /f/ fortition appears to be a Maya identity, via the proxy of the iconic traje típico. As mentioned in Section 3, although the additional statistical analyses of Gender and Ethnicity are limited by the qualitative nature of the data, there were no significant differences in the responses between Maya and non-Maya participants or between female and male participants; all participants in this study, regardless of ethnicity or gender, perceived the guises with apocope and /f/ fortition as being more likely to wear a traje típico than the guises without these features. In other words, these results suggest that the visual body–language link between these phonetic features of Mayan-accented Spanish and the traje típico has moved beyond different subgroups within the country and is present among Guatemalans in general. Additionally, even though a linguistic feature may have an established n order index in general, different contexts and populations often result in said feature gaining new social meanings—what () calls n + 1-order indexes. Within the specific context of Guatemala, the social meaning of these two phonetic features is not just of a Maya identity, but, as many of the responses in the word clouds demonstrate, there is an n + 1-order that ties the Maya identity to a lower social status via the proxy of clothing.

In response to the second research question, which asked whether the gender of the speaker would affect the participants’ responses, the results reveal that the n-order index of the traje típico in the apocope and /f/ fortition guises is strengthened when the guise voice is female. The results in Section 3.3 clearly demonstrate that female-voiced guises with Mayan-accented Spanish elicit responses of Mayan-traditional clothing more frequently than male-voiced guises with the same features. Furthermore, the results demonstrate a possible n-order index of female voices in general: the female-voiced guises are more likely to index a Maya identity than the male-voiced guises regardless of the presence of apocope or /f/ fortition. This statement, of course, has limitations, as it is only based on the four female speakers that created the stimuli for this study and the four male speakers from (, ). Additionally, it must be noted that there may be other linguistic variables in the voices of the female guises that index a Maya identity, e.g., the speakers’ intonational patterns were not analyzed here although previous research has demonstrated ample effects of contact with Mayan languages on Guatemalan Spanish intonation (, , ).

Nonetheless, these findings provide further evidence of language and gender roles and the hierarchies of the indigenous Maya in Guatemala and amongst other populations. Although it is not universal, it is common among indigenous minority groups for the responsibility of linguistic and cultural preservation to fall on women as men shift towards the linguistic and cultural practices of the hegemonic/dominant majority. For example, in his work on the Tolowa in Northern California, Collins notes that it is “predominately the women’s voices which have survived” because, throughout their history, women were the ones that were “emphatically wearing [Tolowa] clothes, sticking with [Tolowa] food, and, most importantly, speaking Tolowa with their children” (). () notes that, among the Asheli of Morocco, the cultural, clothing, and linguistic identities of men were more “compromised” due to contact with more mainstream Moroccan society, with women seen as the “repositories” of Asheli culture and the Tashelhit language and tasked with passing it on to future generations.

As detailed in Section 1, these same gender roles concerning language and cultural maintenance are seen among the Maya in Guatemala. The Maya anthropologist () goes as far as suggesting that the Maya woman is more valiant than the Maya man because she still wears the traje. () contends that it is not just racism in Guatemala that has led men to abandon the traje típico more than women, but also sexism, as a man wearing a traje is often seen as “one who is less masculine (even less adult) in a world dominated by non-Maya values”, whereas a Maya woman is often seen as more feminine in the traje típico (see also ). Various anthropologists have argued that the quintessential image of the Maya is a woman wearing a traje típico (; ; ; ; , ; , ; ; ; ; ; among others). This is evidenced in the Guatemalan newspaper article about the traje típico featured in Figure 1, as there are no mentions of men needing to wear it. All of the onus for its continued usage is placed on women.

In order to gather some quantitative data on the daily usage of the traje típico, I spent two hours in the central plaza of Quetzaltenango, the second largest city in Guatemala, and two hours in the central plaza of the predominantly K’iche’-speaking and more rural municipality Nahualá observing the dress of individuals of all ages; both observations occurred on a Saturday. In Quetzaltenango, I observed the following: 114 of 168 women of all ages wore trajes típicos and none of the 132 men wore a traje típico. In Nahualá, 77 of 79 women of all ages wore a traje típico. The two that did not were workers at a local bank and wore their work uniform. Two of 53 men wore the traje típico, both of whom I know personally, and they were over 70 years old at the time. This exercise has some obvious limitations. For example, it is based on my assumptions of the gender identification of these individuals as I did not interact with them. Nevertheless, these observations corroborate the qualitative remarks from the aforementioned scholars on gender and the traje típico.

The results of this study demonstrate that gendered and cultural practices of the Maya are reflected in the indexical fields of Mayan-accented Spanish in Guatemala, regardless of the gender or ethnicity of the listener. In other words, this link of the visual body and language is significantly more essentialized for the identity of a woman than for the identity of a man in Guatemala. In general, listeners appear to assume that any woman is more likely than a man to be Maya. More specifically, while both Maya women and men are subject to negative stereotypes, the women are also more likely to be bound by Maya-specific stereotypes. Whereas a Maya man may not be seen in the same social class as a Ladino, a Maya woman is not only seen in a lower social class but also as someone who should be wearing the traje típico. These gendered stereotypes are, in turn, reinforced in the local language ideologies. Some individual Ladino participants in this study and in (, ) gave derogatory comments in response to guises with Mayan-accented Spanish. As stated in Section 3.1, in response to Speaker 2’s apocope guise, one participant answered, ‘like a little indigenous woman from the mountain.’ In contrast, disparaging remarks made by individual participants concerning the male-voiced guises were not specifically linked with a Maya identity, e.g., in response to a guise with /f/ fortition in (), one participant replied that they pictured the speaker as a gang member whose specific role was assaulting individuals, sans any reference to the speaker’s ethnicity. Thus, these language ideologies, gendered stereotypes, and the embodied practices of the Maya appear to be mutually reinforcing one another in Guatemala.

What this matched-guise does not tell us is what the response traje típico signifies, besides a Maya identity, for the participants of this study. As stated earlier, the layered meanings of the female traje típico in Guatemala are vast and a detailed analysis is outside of the scope of this study. However, even though there were no statistical differences between the number of traje típico responses by Gender or Ethnicity, we cannot simply assume that every participant in this study views the traje típico in the same way. As illustrated in Figure 1, there are many that celebrate the traje típico and the Maya culture and identity that it represents; it continues to be worn by Maya women as a source of pride in everyday life and in a growing number of other contexts, such as at the Miss Universe competition, at international film festivals, and as a uniform during athletic competitions (; ; ; ). For these Maya women, the traje típico has become emblematic of their resistance to the widespread attempts of their own nation to erase them. On the other hand, the traje típico may also be representative of the negative stereotypes that still accompany being Maya in Guatemala. For Ladinos, and even some Maya, it may represent a caricature of the static and traditional Maya that is an obstacle to national progress, something that only serves to appease the curiosity of foreign tourists. () even argues that the traje típico is a common trope in racist and sexist jokes that Ladinos make about the Maya. Furthermore, participants’ responses in this study also parallel a national process of amalgamation of the Maya into a single ethnic group. Many of the responses that indexed Maya identity in the word clouds were very general in nature, even though each community has a distinct traje. Hence, future studies will need to investigate listeners’ attitudes towards the traje and the Maya in relation to their sociolinguistic reactions to features of Mayan-accented Spanish.

Finally, as in previous work, such as ’s () and ’s () seminal studies, this paper reveals how linguistic variables and material style work together in the creation of an identity as visual body–language links (). However, a key difference here is that, whereas those investigations focus on the production of different linguistic variables and fashion choices by individuals, the present study examines this link from the point of view of perception. For example, () finds that Latina youth gang members in California use material style, such as longer eye liner, and phonetic variables, such as fortition of /θ/ to [t̪], together in the creation of their desired identities. However, what we do not known is how strong this visual body–language link is between longer eye liner and /θ/ fortition for community members. In other words, would /θ/ fortition index longer eye liner among listeners like Mayan-accented Spanish indexes the traje típico? As such, future studies should continue this line of research by exploring the perception of visual body–language links from a third-wave perspective.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study further demonstrate the inseparable relationship between language and society: “no language is spoken in a vacuum” (). Language users, their experiences, their cultures, etc., help to mold the indexical fields of different linguistic variables. The findings of this study undoubtedly demonstrate that the gender roles and cultural practices of the Maya are so embedded in Guatemalan society that they are a critical variable in the indexical field of Mayan-accented Spanish.

According to (), although fashion is often a more deliberate choice than linguistic style, they are both examples of the bricolage of identity. Many Maya women consciously choose to wear the traje típico in both their day-to-day lives in Guatemala and even abroad because of what it represents to them. Many also choose to continue speaking their Mayan languages. As in all contexts of bilingualism and language contact, some linguistic features may transfer between languages. Future research is needed in order determine if these specific linguistic variables are consciously used by different Mayan–Spanish bilinguals along with the traje típico in order to index a Maya identity, as seen in other populations (; ; ).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Middlebury College (protocol code 17121 and date of approval: 1 December 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to IRB restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Binomial tests (one-tailed) frequency tables of compared responses of female-voiced guises.

| Speaker 1 | |||

| Response | apocope guise | non-apocope guise | p-value |

| traje típico | 0.409 | 0.055 | <0.001 |

| indígena | 0.036 | 0.009 | <0.01 |

| Speaker 2 | |||

| Response | apocope guise | non-apocope guise | p-value |

| traje típico | 0.391 | 0.109 | <0.001 |

| huipil | 0.127 | 0.018 | <0.001 |

| corte | 0.136 | 0.018 | <0.001 |

| ladina | 0.018 | 0.045 | 0.129 |

| Speaker 3 | |||

| Response | [p] guise | [f] guise | p-value |

| traje típico | 0.464 | 0.064 | <0.001 |

| ladina | 0.018 | 0.055 | 0.068 |

| Speaker 4 | |||

| Response | [p] guise | [f] guise | p-value |

| traje típico | 0.427 | 0.082 | < 0.001 |

| huipil | 0.172 | 0.009 | < 0.001 |

Appendix B

Binomial tests (one-tailed) frequency tables of traje típico responses across male- and female-voiced guises.

| Guise Comparison | Female-Voiced Guises | Male-Voiced Guises | p-Value |

| apocope | 0.605 | 0.147 | <0.001 |

| non-apocope | 0.100 | 0.013 | <0.001 |

| fortition | 0.745 | 0.078 | <0.001 |

| non-fortition | 0.077 | 0.009 | <0.001 |

Notes

| 1. | As in (), the word cinco was used as it may illustrate apocope and is common in street names. As a reviewer points out, these elicitation sentences contain other words that could possibly demonstrate apocope and forition. However, as this study specifically investigates if a single occurrence of apocope or fortition would index a Maya identity, additional examples were not included. Furthermore, it was decided that this was more natural, as production studies have shown that Spanish–Mayan bilinguals do not produce these features in every possible context (). Future research is warranted as to whether more cases of apocope and forition in a guise elicit even stronger perceptions of Maya identity, as discussed in () regarding /s/ aspiration in Puerto Rican Spanish. |

| 2. | This question was left as the masculine, or unmarked, ‘este hablante’ and not the feminine gendered ‘esta hablante’ in order to avoid specific priming of the female gender of the guise voices to the participants. As a reviewer suggests, particpants could simply view this as a grammatical error. However, as no participant commented on this, it is not known if any did view it as such. |

| 3. | For the articles of clothing depicted in Figure 1 and also given as responses to the matched-guises, faja ‘sash’, cinta ‘hair ribbon’, and collar ‘necklace’ are not considered to be directly indexing Maya identity here, as these words do not only signify parts of the traje típico, but articles of clothing in general. |

| 4. | Results by Gender: Speaker 1 apocope guise, p = 0.071; Speaker 1 non-apocope guise, p = 0.106; Speaker 2 apocope guise, p = 0.067; Speaker 2 non-apocope guise, p = 0.923. Results by Ethnicity: Speaker 1 apocope guise, p = 0.126; Speaker 1 non-apocope guise, p = 0.206; Speaker 2 apocope guise, p = 0.122; Speaker 2 non-apocope guise, p = 0.079. |

| 5. | Results by Gender: Speaker 3 fortition guise, p = 0.097; Speaker 3 non-fortition guise, p = 0.872; Speaker 4 fortition guise, p = 0.841, Speaker 4 non-fortition guise, p = 0.849. Results by Ethnicity: Speaker 3 fortition guise, p = 0.578; Speaker 3 non-fortition guise, p = 0.071; Speaker 4 fortition guise, p = 0.326; Speaker 4 non-fortition guise, p = 0.074. |

| 6. | Due to all of these combinations, the results presented in this section cannot be interpreted as a true matched-guise, as the comparison of different voices presents considerably more uncontrolled variables than () originally intended in this framework. |

References

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2012. The Languages of the Amazon. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aleza Izquierdo, Milagros. 2010. Fonética y fonología. In La Lengua Española en América: Normas y Usos Actuales. Edited by Milagros Aleza Izqueirdo and José María Enguita Utrilla. Valencia: Universitat de València, pp. 51–94. [Google Scholar]

- Annis, Sheldon. 1987. God and Production in a Guatemalan Town. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, Brandon. 2015. Pre-nuclear peak alignment in the Spanish of Spanish-K’ichee’ (Mayan) bilinguals. In Selected Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Laboratory Approaches to Romance Phonology. Edited by Erik W. Willis, Pedro Martín Butragueño and Esther Herrera Zendejas. Cascadilla: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 163–74. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, Brandon. 2017. Prosodic transfer among Spanish-K’ichee’ Bilinguals. In Mutlidisciplinary Appraoches to Bilinguaism in the Hispanic and Lusophone World. Edited by Kate Bellamy, Michael W. Child, Paz González, Antje Muntendam and M. Carmen Parafita Couto. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 147–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, Brandon. 2019. Ciudadano maya 100%: Uso y actitudes de la lengua entre los bilingües k’iche’-español. Hispania 102: 319–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, Brandon. 2021a. “Para mí, es indígena con traje típico”: Apocope as an indexical marker of indigeneity in Guatemalan Spanish. In Topics in Spanish Linguistic Perceptions. Edited by Luis A. Ortiz and Eva-María Suárez Budenbender. New York: Routledge, pp. 223–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, Brandon. 2021b. Bilingual language dominance and contrastive focus marking: Gradient effects of K’ichee’ syntax on Spanish prosody. International Journal of Bilingualism 25: 500–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, Brandon. 2023. Social perceptions of /f/ fortition in Guatemalan Spanish. Spanish in Context. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, Brandon. forthcoming. Spanish in contact with Mayan languages in Guatemala. In Contact Varieties of Spanish and Spanish-Iexified Contact Varieties. Volume II, Indigenized Varieties of Spanish in Multilingual Scenarios. Edited by Leonardo Cerno, Hans-Jörg Döhla, Miguel Gutiérrez Maté, Robert Hesselbac and Joachim Steffen. Berlin: De Grutyer.

- Baird, Brandon, and Brendan Regan. forthcoming. The status of /f/ in Mayan-accented Spanish. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics.

- Baird, Brandon, Marcos Rohena-Madrazo, and Caroline Cating. 2018. Perceptions of Lexically Specific Phonology Switches on Spanish-origin Loan Words in American English. American Speech 93: 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrés Jáuregui, Antonio. 1892. Vicios del lenguaje y provincialismos de Guatemala. Guatemala City: Encuadernación y tipografía nacional. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, Jeremy. 2019. From Sissy to Sickening: The Indexical Landscape of /s/ in SoMa, San Francisco. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 29: 332–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Whitney, ed. 2019. Recent Advances in the Study of Spanish Sociophonetic Perception. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, Jane Fishburn. 1997. From Duty to Desire: Remaking Families in a Spanish Village. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, James. 1998. Understanding Tolowa Histories: Western Hegemonies & Native American Responses. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Colop, Marylin. 2013. El traje típico es representativo de la cultura maya: Mujeres de Cantel mantienen uso. El Quetzalteco, Prensa Libre. Available online: issuu.com/elquetzalteco/docs/el_traje_tipico_representativo_de_l (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Drager, Katie, Rachel Schutz, Ivan Chik, Kate Hardeman, and Victor Jih. 2012. When Hearing Is Believing: Perceptions of Speaker Style, Gender, Ethnicity, and Pitch. Paper presented at LSA Annual Meeting, Portland, ON, USA, January 5–8; Available online: www.katiedrager.com/publications (accessed on 3 October 2017).

- Eckert, Penelope. 1980. Clothing and geography in a suburban high school. In Researching American Culture. Edited by Conrad Phillip Kottak. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 139–45. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2008. Variation and the Indexical Field. Journal of Sociolinguistics 12: 453–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2012. Three waves of variation study: The emergence of meaning in the study of sociolinguistic variation. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope, and Sally McConnell-Ginet. 2003. Language and Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- England, Nora. 2003. Mayan language revival and revitalization politics: Linguists and linguistic ideologies. American Anthropologist 105: 733–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, Nora, and Brandon Baird. 2017. Phonology and Phonetics. In The Mayan Languages. Edited by Judith Aissen, Nora England and Roberto Zavala. New York: Routledge, pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- French, Brigittine M. 2010. Maya Ethnolinguistic Identity Violence, Cultural Rights, and Modernity in Highland Guatemala. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- García, Christina, Abby Walker, and Mary Beaton. 2023. Exploring the role of phonological environment in evaluating social meaning: The case of /s/ aspiration in Puerto Rican Spanish. Languages 8: 186. [Google Scholar]

- García Tesoro, Ana Isabel. 2008. Guatemala. In El español en América: Contactos lingüísticos en Hispanoamérica. Edited by Azucena Palacios. Barcelona: Ariel Letras, pp. 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, John P., and Walter Randolph Adams. 2005. Roads to Change in Maya Guatemala: A Field School Approach to Understanding the K’iche’. Oklahoma City: Oklahoma University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson, Carol. 1995. Weaving Identities: Construction of Dress and Self in a Highland Guatemala Town. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson, Carol. 1996. Women, Weaving, and Education in Maya Revitalization. In Maya Cultural Activism in Guatemala. Edited by Edward F. Fischer and R. McKenna Brown. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 156–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, Katherine E. 2008. We Share Walls: Language, Land, and Gender in Berber Morocco. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Guatemala. 2018. XII Censo Nacional de Población y VII Censo Nacional de Vivienda. Available online: www.censopoblacion.gt/ (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Kirtley, M. Joelle. 2011. Speech in the U.S. Military: A Sociophonetic Perception Approach to Identity and Meaning. Master’s thesis, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Manoa, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Wallace E., Richard C. Hodgson, Robert C. Gardener, and Samuel Fillenbaum. 1960. Evaluational Reactions to Spoken Languages. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 60: 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lentzner, Karl. 1893. Observations on the Spanish language in Guatemala. Modern Language Notes 8: 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Denton, Norma. 2008. Homegirls: Language and Cultural Practice among Latina Youth Gangs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nance, Claire. 2013. Phonetic Variation, Sound Change, and Identity in Scottish Gaelic. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Diane M. 1999. A Finger in the Wound: Body Politics in Quincentennial Guatemala. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Diane M. 2009. Reckoning: The End of War in Guatemala. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oertling, Emily. 2021. Made in San Pedro: The Production of Dress and Meaning in a Tz’utujil-Maya Municipality. Ph.D. dissertation, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ortíz-López, Luis Alfredo, and Eva María Suárez Büdenbender, eds. 2021. Topics in Spanish Linguistic Perceptions. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Otzoy, Irma. 1996. Maya clothing and identity. In Maya Cultural Activism in Guatemala. Edited by Edward F. Fischer and R. McKenna Brown. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 141–55. [Google Scholar]

- Redacción Espectáculos. 2015. Polémica entre Miss Costa Rica y Miss Guatemala enciende las redes. Prensa Libre. Available online: https://www.prensalibre.com/vida/escenario/polemica-entre-miss-costa-rica-y-miss-guatemala-enciende-las-redes/ (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Reyes, Ingrid. 2019. María Merecs Coroy viste traje de Quetzaltenango en premier de Venecia y explica por qué utiliza diferentes trajes indígenas en festivales de cine. Prensa Libre. Available online: www.prensalibre.com/vida/escenario/maria-mercedes-coroy-con-traje-de-quetzaltenango-en-la-premier-de-venecia-y-explica-que-la-inspira-a-presentar-diferentes-trajes-tipicos-en-los-festivales-de-cine/ (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Romero, Sergio. 2015. Language and Ethnicity among the K’ichee’ Maya. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sam Chum, Eduardo. 2019. María Tun Cho completa el maratón de Los Ángeles con un mensaje claro: “Las mujeres podemos”. Prensa Libre. Available online: www.prensalibre.com/deportes/deporte-nacional/maria-tun-cho-completa-el-maraton-de-los-angeles-con-un-mensaje-claro-las-mujeres-podemos/ (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Silverstein, Michael. 2003. Indexical Order and the Dialectics of Sociolinguistic Life. Language & Communication 23: 193–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von den Berghe, Pierre L. 1968. Ethnic membership and cultural change in Guatemala. Social Forces 46: 514–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Qing. 2008. Rhotacization and the “Beijing Smooth Operator”: The meaning of a sociolinguistic variable. Journal of Sociolinguistics 12: 201–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).