Combinatorial Productivity of Spanish Verbal Periphrases as an Indicator of Their Degree of Grammaticalization

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| (1) | a. | Por | fin | dej-ó | de | llov-er | ||||

| for | end | leave-ind.pst.3sg | of | rain-inf | ||||||

| ‘At last, it stopped raining’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Cuando | par-e | de | llov-er, | tend-er-é | la | ropa | |||

| when | stop-subj.pst.3sg | of | rain-inf | hang.out-fut-1sg | the | clothes | ||||

| ‘When it stops raining, I’ll hang out the clothes’ | ||||||||||

2. Theoretical and Methodological Framework

3. The Semantics of dejar de + inf and parar de + inf in Contemporary Spanish

| (2) | a. | Dej-ó | de | cenar | porque | lo | llam-ar-on | |

| leave-ind.pst.3sg | of | dine-inf | because | 3sg.m.acc | call-ind.pst-3pl | |||

| ‘He stopped eating dinner because someone called him’ | ||||||||

| b. | ¡Par-a | de | mov-er-te, | por | favor! | |||

| stop-imp | of | move-inf-pron | for | favour | ||||

| ‘Stop moving, please!’ | ||||||||

| (3) | a. | No | dej-a/par-a | de | le-er | ese | libro | |||

| neg | leave/stop-ind.prs.3sg | of | read-inf | that | book | |||||

| ‘(S)he doesn’t stop reading that book’ | ||||||||||

| b. | ¡Sara, | dej-a/par-a | de | salt-ar! | ||||||

| Sara | leave/stop-imp | of | jump-inf | |||||||

| ‘Sara, stop jumping!’ | ||||||||||

| c. | Juan | no | par-ab-a/dej-ab-a | de | agradec-er | a | su | madre | ||

| Juan | neg | leave/stop-ind.pst-3sg | of | thank-inf | to | his | mother | |||

| ‘Juan kept on thanking his mother’ | ||||||||||

| (4) | a. | no | dej-ó | de | advert-ir | que | ten-í-an | […] | |

| neg | leave-ind.pst.3sg | of | notice-inf | comp | have-ind.pst-3pl | ||||

| ‘She noticed that they had […]’ (Alegría, Perros hambrientos, 1939, CORDE) | |||||||||

| b. | no | dej-o | de | conoc-er | que | lo | que | ||

| neg | leave-ind.prs.1sg | of | know-inf | comp | 3sg.m.acc | comp | |||

| pid-es | es | bueno | |||||||

| ask.for-ind.prs.2sg | be.ind.prs.3sg | good | |||||||

| ‘I know that what you ask for is good’ (Menéndez Pelayo, Orígenes de la novela, 1905, CORDE) | |||||||||

| c. | Adiós, | no | dej-e-n | de | avis-ar | ||||

| goodbye | neg | leave-subj.prs-2pl | of | notice-inf | |||||

| ‘Goodbye, please let us know.’ (Ignacio Aldecoa, El fulgor y la sangre, 1954, CORDE) | |||||||||

| d. | No | dej-e-s | de | ir | a | la | Villa | d’Este | |

| neg | leave-subj.prs-2sg | of | go.inf | to | the | Villa | d’Este | ||

| ‘Be sure to go to Villa d’Este.’ (Pedro Salinas, Correspondencia, 1951, CORDE) | |||||||||

| (5) | a. | hab-í-a | dej-ado | de | aparec-er | por | sus | habitaciones | ||

| have-ind.pst.3sg | leave-ptcp | of | appear-inf | for | their | hedrooms | ||||

| ‘(S)he had ceased to appear in their rooms’ (Martín Virgil, Los curas comunistas, 1968, CORDE) | ||||||||||

| b. | no | pod-emos | dej-ar | de | advertir | que | […] | |||

| neg | can-ind.pst.3sg | leave-inf | of | notice-inf | comp | |||||

| ‘We cannot fail to point out that […]’ (Malpica, El desarrollismo en el Perú, 1974, CORDE) | ||||||||||

4. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of the Corpus Data

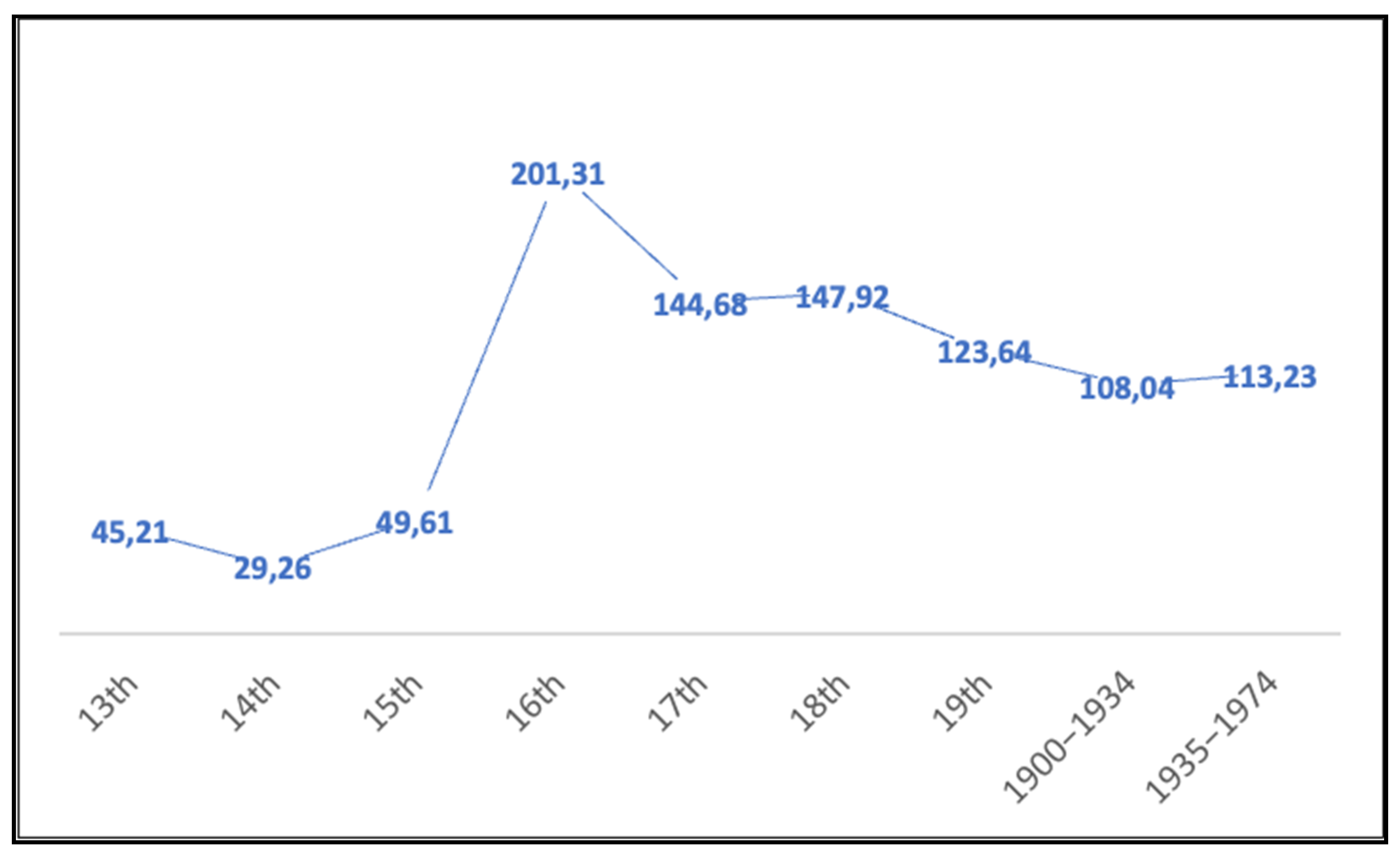

4.1. Frequency of dejar de + inf and parar de + inf in CORDE

4.2. Productivity of the Constructions dejar de + inf and parar de + inf

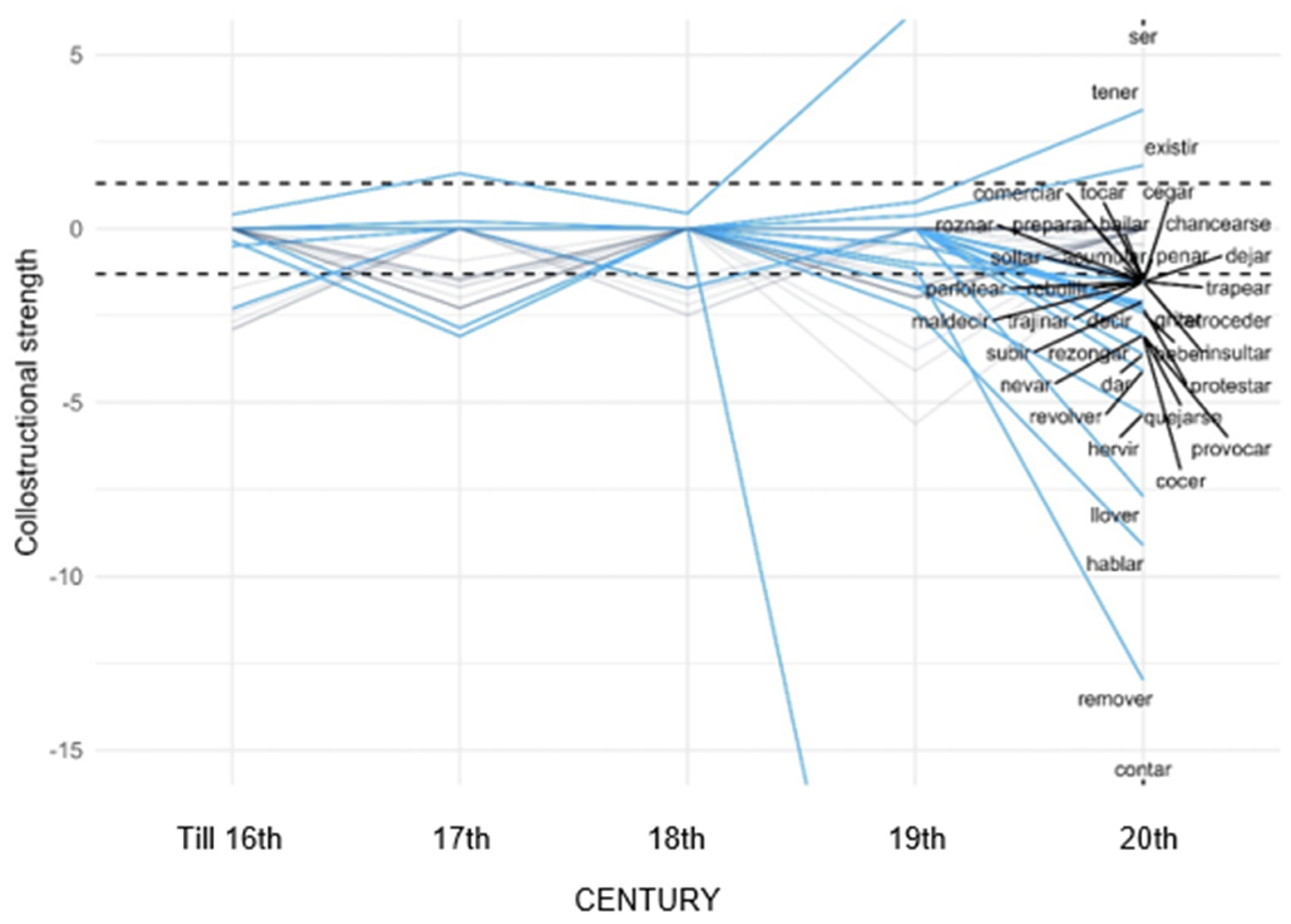

4.3. Distinctive Collexeme Analysis

4.3.1. In General

4.3.2. Per Period

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aaron, Jessi E. 2010. Pushing the envelope: Looking beyond the variable context. Language Variation and Change 22: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aparicio Mera, Juan J. 2016. Representación computacional de las perífrasis de fase: De la cognición a la computación. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. Available online: https://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/101660/1/Tesis_JJAparicio.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Baayen, Harald R. 2009. Corpus linguistics in morphology: Morphological productivity. In Corpus Linguistics. An International Handbook. Edited by Anke Lüdeling and Merja Kytö. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter, pp. 900–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barðdal, Jóhanna. 2008. Productivity: Evidence from Case and Argument Structure in Icelandic. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Barðdal, Jóhanna, Elena Smirnova, Lotte Sommerer, and Spike Gildea. 2015. Diachronic Construction Grammar. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2003. Mechanisms of change in grammaticization: The role of frequency. In The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Edited by Brian Joseph and Richard Janda. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 602–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan, and Rena Torres-Cacoullos. 2009. The role of prefabs in grammaticization. How the particular and the general interact in language change. In Formulaic Language. Volume 1. Distribution and Historical Change. Edited by Roberta Corrigan, Edith A. Moravcsik, Hamid Ouali and Kathleen M. Wheatley. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Camus, Bruno. 2006a. Dejar de + infinitivo. In Diccionario de perífrasis verbales. Edited by García Fernández Luis, Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, Bruno Camus, María Martínez Atienza and María Ángeles García. Madrid: Gredos, pp. 117–20. [Google Scholar]

- Camus, Bruno. 2006b. Parar de + infinitivo. In Diccionario de perífrasis verbales. Edited by García Fernández Luis, Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, Bruno Camus, María Martínez Atienza and María Ángeles García. Madrid: Gredos, pp. 206–9. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco Gutiérrez, Ángeles. 2008. Llegar a + infinitivo como conector aditivo en español. Revista española de lingüística 38: 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copple, Mary T. 2011. Tracking the constraints on a grammaticalizing perfect(ive). Language Variation and Change 23: 163–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corominas, Joan, and José Antonio Pascual. 1991. Diccionario crítico etimológico castellano e hispánico. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, William. 2000. Explaining Language Change. An Evolutionary Approach. Harlow: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, William, and Alan Cruise. 2004. Cognitive Linguistics. New York: CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Castro, Félix. 1999. Las perífrasis verbales en el español actual. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore, Charles J. 1996. The Pragmatics of Constructions. In Social Interaction, Context, and Language. Edited by Dan Isaac Slobin, Julie Gerhardt, Amy Kyratzis and Jiansheng Guo. New Jersey: L. Erlbaum Associates, pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, Miriam. 2009. Construction Grammar as a tool for diachronic analysis. Constructions and Frames 1: 261–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garachana, Mar. 2011. Perífrasis sinónimas. ¿Gramaticalizaciones idénticas? Mas retos para la teoría de la gramaticalización. In Sintaxis y análisis del discurso hablado en español: Homenaje a Antonio Narbona. Edited by José Jesús de Bustos Tovar, Rafael Cano Aguilar, Elena Méndez García de Paredes and Araceli López Serena. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, pp. 779–98. [Google Scholar]

- Garachana, Mar. 2016. Restricciones léxicas en la gramaticalización de las perífrasis verbales. Rilce 32: 136–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garachana, Mar. 2017. Los límites de una categoría híbrida. Las perífrasis verbales. In La gramática en la diacronía. La evolución de las perífrasis verbales modales en español. Edited by Mar Garachana Camarero. Madrid-Frankfurt: Iberoamericana-Vervuert, pp. 35–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garachana, Mar. 2021. Bailando, me paso el día bailando y los vecinos mientras tanto no paran de molestar. Parar de + Inf as an Interruptive Verbal Periphrasis in Spanish. Languages 6: 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garachana, Mar. 2022. Unexpected grammaticalizations. The reanalysis of the Spanish verb ir ‘to go’ as a past marker. In From Verbal Periphrases to Complex Predicates. Edited by Mar Garachana, Sandra Montserrat and Claus Pusch. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 171–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garachana, Mar. n.d. Gramaticalización, tradicionalidad discursiva y presiones paradigmáticas en la evolución de dejar de + INF en español. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie. [CrossRef]

- Garachana, Mar, and Malte Rosemeyer. 2011. Rutinas léxicas en el cambio gramatical. El caso de las perífrasis deónticas e iterativas. Revista de Historia de La Lengua Española 6: 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Fernández, Luis, and Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez. 2008. Perífrasis verbales con función de marcador del discurso. Contrarréplica a Olbertz (2007). Verba 35: 439–47. [Google Scholar]

- García Fernández, Luis, Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, Bruno Camus, María Martínez Atienza, and María Ángeles García. 2006. Diccionario de perífrasis verbales. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- García Miguel, José M., Gael Vaamonde, and Fita González Domínguez. 2010. ADESSE, a Database with Syntactic and Semantic Annotation of a Corpus of Spanish. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’10). Edited by Nicoletta Calzolari, Khalid Choukri, Bente Maegaard, Joseph Mariani, Jan Odijk, Stelios Piperidis, Mike Rosner and Daniel Tapias. Valetta: European Language Resources Association (ELRA), pp. 1903–10. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Adele. 2006. Constructions at Work. The Nature of Generalization in Language. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Manzano, Pilar. 1992. Perífrasis verbales con infinitivo: Valores y usos en la lengua hablada. Madrid: UNED. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Torrego, Leonardo. 1988. Perífrasis verbales. Sintaxis, semántica y estilística. Madrid: Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Torrego, Leonardo. 1999. Los verbos auxiliares. Las perífrasis verbales de infinitivo. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, pp. 3323–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gries, Stefan, and Anatol Stefanowitsch. 2004. Extending collostructional analysis: A corpus-based perspective on ‘alternations’. lnternational Journal of Corpus Linguistics 9: 97–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilpert, Martin. 2006. Distinctive collexeme analysis and diachrony. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory 2: 243–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilpert, Martin. 2013. Constructional Change in English: Developments in Allomorphy, Word Formation, and Syntax. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107013483. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, Thomas. 2013. Abstract phrasal and clausal constructions. In The Oxford Handbook of Construction Grammar. Edited by Graeme Trousdale and Thomas Hoffmann. Cambridge: CUP, pp. 307–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Thomas. 2014. The Cognitive Evolution of Englishes: The Role of Constructions in the Dynamic Model. In The Evolution of Englishes: The Dynamic Model and Beyond. Edited by Sarah Buschfeld, Thomas Hoffmann, Magnus Huber and Alexander Kautzsch. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 160–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul J. 1991. On some Principles of Grammaticalization. In Approaches to Grammaticalization. Edited by Elizabeth C. Traugott and Bernd Heine. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 1, pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 1987. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar. Vol. 1. Theoretical Prerequisites. Stanford: SUP. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 2003. Constructions in cognitive grammar. English Linguistics 20: 41–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levshina, Natalia. 2015. How to Do Linguistics with R: Data Exploration and Statistical Analysis. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Olbertz, Hella. 1998. Verbal Periphrases in a Functional Grammar of Spanish. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Olbertz, Hella. 2007. ¿Perífrasis verbales con función de marcador de discurso? A propósito del Diccionario de perífrasis verbales. Verba 34: 381–90. [Google Scholar]

- Perek, Florent. 2020. Productivity and schematicity in constructional change. In Nodes and Networks in Diachronic Construction Grammar. Edited by Lotte Sommerer and Elena Smirmova. Amsterdam and Philadephia: John Benjamins, pp. 141–66. [Google Scholar]

- RAE/ASALE. 2009. Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española. 2007. Banco de datos (CORDE) [en línea]. Corpus diacrónico del español. Available online: http://www.rae.es (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Rodríguez Molina, Javier. 2004. Difusión léxica, cambio semántico y gramaticalización: El caso de haber + participio en español antiguo. Revista de filología española 84: 169–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez Molina, Javier. 2007. La selección del auxiliar en el Poema de Mio Cid y otros textos medievales: Cuestiones filológicas. In Actes du XXIV Congrès International de Linguistique et de Philologie Romanes. Edited by David. Trotter. Berlin: Max Niemeyer Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Molina, Javier, and Álvaro S. Octavio de Toledo y Huerta. 2017. La imprescindible distinción ente texto y testimonio: El CORDE y los criterios de fiabilidad lingüística. Scriptum Digital 6: 5–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rosemeyer, Malte, and Mar Garachana. 2019. De la consecución a la contraexpectación: La construccionalización de Lograr/Conseguir + Infinitivo. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone linguistics 12: 383–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Cacoullos, Rena. 2012. Grammaticalization through inherent variability. The development of a progressive in Spanish. Studies in Language 36: 73–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traugott, Elizabeth. C., and Graeme Trousdale. 2013. Constructionalization and Constructional Changes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yllera, Alicia. 1980. Sintaxis histórica del verbo español: Las perífrasis medievales. Zaragoza: Departamento de Filología Francesa, Universidad de Zaragoza. [Google Scholar]

| Construction | 13th | 14th | 15th | 16th | 17th | 18th | 19th | 20th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dejar_de + inf | 349 | 219 | 1268 | 10,058 | 5363 | 2151 | 5290 | 6664 |

| parar_de + inf | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 28 | 7 | 56 | 202 |

| Construction | 13th | 14th | 15th | 16th | 17th | 18th | 19th | 20th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parar de + inf | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.37 |

| dejar de + inf | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| Construction | 13th | 14th | 15th | 16th | 17th | 18th | 19th | 20th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parar de + inf | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.39 | 0.22 |

| dejar de + inf | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Preference | Quantity |

|---|---|

| dejar de | 5 |

| none | 1594 |

| parar de | 64 |

| Lexeme | collStr |

|---|---|

| ser ‘to be’ | 24,231 |

| tener ‘to have’ | 4342 |

| hacer ‘to do’ | 3514 |

| haber ‘to have’ | 1782 |

| ver ‘to see’ | 1609 |

| Lexeme | collStr | Lexeme | collStr | Lexeme | collStr | Lexeme | collStr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| contar ‘to tell’ | −45,805 | quejarse ‘to complaint’ | −3034 | refregar ‘to scrub’ | −2012 | vocear ‘to holler’ | −1713 |

| remover ‘to stir’ | −17,019 | subir ‘to go up’ | −2855 | retroceder ‘to move back’ | −2012 | trabajar ‘to work’ | −1649 |

| llover ‘to rain’ | −9892 | echar ‘to throw’ | −2336 | roznar ‘to bray’ | −2012 | agitar ‘to shake’ | −1539 |

| hablar ‘to speak’ | −8533 | mover ‘to move’ | −2207 | trajinar ‘to bustle’ | −2012 | regañar ‘to scold’ | −1539 |

| hervir ‘to boil’ | −8040 | bailar ‘to dance’ | −2131 | trapear ‘to mop’ | −2012 | revolotear ‘to flutter’ | −1539 |

| revolver ‘to stir’ | −6187 | acumular ‘to accumulate’ | −2012 | tronar ‘to thunder’ | −2012 | roltar ‘to let go’ | −1539 |

| beber ‘to drink’ | −4876 | aporracear ‘to beat’ | −2012 | zaherir ‘to taunt’ | −2012 | trinar ‘to trill’ | −1539 |

| correr ‘to run’ | −4301 | chancearse ‘to jest’ | −2012 | clamar ‘to cry out’ | −1986 | vomitar ‘to throw up’ | −1539 |

| cocer ‘to cook’ | −4135 | comerciar ‘to trade’ | −2012 | cantar ‘to sing’ | −1933 | cegar ‘to blind’ | −1416 |

| bullir ‘to boil’ | −3551 | contrastar ‘to contrast’ | −2012 | derrocar ‘to overthrow’ | −1713 | exclamar ‘to exclaim’ | −1416 |

| provocar ‘to provoke’ | −3551 | dejar ‘to leave’ | −2012 | frotar ‘to rub’ | −1713 | tragar ‘to swallow’ | −1416 |

| rezongar ‘to grumble’ | −3551 | disparatar ‘to talk nonsense’ | −2012 | insultar ‘to insult’ | −1713 | reír ‘to laugh’ | −1405 |

| nevar ‘to snow’ | −3253 | levar ‘to carry’ | −2012 | lisonjear ‘to flatter’ | −1713 | dar ‘to give’ | −1404 |

| gritar ‘to shout’ | −3252 | parlotear ‘to chatter’ | −2012 | mecer ‘to rock’ | −1713 | acrecentar ‘to increase’ | −1322 |

| tocar ‘to touch’ | −3110 | rebullir ‘to start moving’ | −2012 | preparar ‘to prepare’ | −1713 | fregar ‘to scrub’ | −1322 |

| protestar ‘to protest’ | −3034 | rechinar ‘to grind’ | −2012 | retorcer ‘to twist’ | −1713 | toser ‘to cough’ | −1322 |

| Period | None | parar de | dejar de |

|---|---|---|---|

| until–16th | 845 | 7 | 0 |

| 17th–18th | 809 | 16 | 1 |

| 19th | 716 | 18 | 1 |

| 20th | 808 | 35 | 3 |

| Lexeme | collStr | Frequency | Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| ser ‘to be’ | 2375 | 1158 | 17th–18th |

| 6283 | 1247 | 19th | |

| 24,910 | 1682 | 20th | |

| tener ‘to have’ | 3414 | 276 | 20th |

| existir ‘to exist’ | 1821 | 156 | 20th |

| Period | Lexeme | Frequency | collStr |

|---|---|---|---|

| until–16th | bullir ‘to boil’, levar ‘to carry’, lisonjear ‘to flatter’ | 1 | −2900 |

| 17th–18th | aporracear ‘to beat’, contrastar ‘to contrast’, derrocar ‘to overthrow’, rechinar ‘to grind’, tronar ‘to thunder’, vocear ‘to holler’ | 1 | −2334 |

| 19th | disparatar ‘to talk nonsense’, mecer ‘to rock’, refregar ‘to scrub’, regañar ‘to scold’, tragar ‘to swallow’, zaherir ‘to taunt’ | 1 | −1980 |

| 20th | acumular ‘to accumulate’, cegar ‘to blind’, chancearse ‘to jest’, comerciar ‘to trade’, dejar ‘to leave’, insultar ‘to insult’, maldecir ‘to curse’, parlotear ‘to chatter’, penar ‘to suffer’, preparar ‘to prepare’, rebullir ‘to start moving’, retroceder ‘to move back’, roznar ‘to bray’, soltar ‘to release’, trajinar ‘to bustle’, trapear ‘to mop’ | 1 | −1531 |

| 20th | nevar ‘to snow’, provocar ‘to provoke’, quejarse ‘to complaint’, rezongar ‘to grumble’ | 2 | −3065 |

| Period | Lexeme | Frequency with dejar de | collStr |

|---|---|---|---|

| until–16th | acrecentar ‘to increase’ | 2 | −2423 |

| revolver ‘to stir’ | 3 | −2298 | |

| tañer ‘to toll’ | 14 | −1727 | |

| 17th–18th | danzar ‘to dance’, recoger ‘to pick up’ | 1 | −2034 |

| moler ‘to grind’, porfiar ‘to persist’ | 3 | −1735 | |

| agradecer ‘to thank’, combater ‘to fight’ | 6 | −1495 | |

| tentar ‘to tempt’, volar ‘to fly’ | 7 | −1438 | |

| 19th | bullir ‘to boil’, exclamar ‘to exclaim’, hervir ‘to boil’, subir ‘to go up’, vomitar ‘to throw up’ | 1 | −1681 |

| añadir ‘to add’ | 2 | −1507 | |

| practicar ‘to practice’ | 3 | −1384 |

| Period | Lexeme | Frequency with parar de vs. dejar de | collStr |

|---|---|---|---|

| until–16th | trabajar ‘to work’ | 2 vs. 52 | −2690 |

| 17th–18th | hablar ‘to speak’ | 3 vs. 44 | −2890 |

| beber ‘to drink’ | 2 vs. 11 | −2802 | |

| 19th | contar ‘to tell’ | 19 vs. 13 | −30,602 |

| correr ‘to run’ | 5 vs. 17 | −5617 | |

| echar ‘to throw’ | 4 vs. 19 | −4084 | |

| clamar ‘cry out’ | 2 vs. 1 | −3493 | |

| hablar ‘to speak’ | 4 vs. 60 | −2366 | |

| 20th | contar ‘to tell’ | 35 vs. 12 | −44,326 |

| remover ‘to stir’ | 10 vs. 3 | −12,986 | |

| hablar ‘to speak’ | 18 vs. 85 | −9108 | |

| llover ‘to rain’ | 10 vs. 23 | −7700 | |

| hervir ‘to boil’ | 5 vs. 5 | −5329 | |

| revolver ‘to stir’ | 4 vs. 5 | −4088 | |

| dar ‘to give’ | 11 vs. 94 | −3618 | |

| cocer ‘to cook’ | 3 vs. 4 | −3094 | |

| beber ‘to drink’ | 5 vs. 31 | −2424 | |

| protestar ‘to protest’ | 2 vs. 2 | −2304 | |

| gritar ‘to shout’ | 3 vs. 10 | −2239 | |

| decir ‘to say’ | 5 vs. 37 | −2133 | |

| subir ‘to go up’ | 2 vs. 3 | −2090 | |

| tocar ‘to touch’ | 5 vs. 55 | −1509 | |

| bailar ‘to dance’ | 3 vs. 22 | −1446 |

| Lexicon | Grammar | Pragmatics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dejar de+ INF | STAGE 1 Etymon | STAGE 2 Bridging context | STAGE 3 Interruptive Verbal Periphrasis | STAGE 4 Continuative Verbal periphrasis | STAGE 5 Assertive and negative values |

| Semantics/pragmatics | dejar = ‘place sth. somewhere’ Dejó los libros sobre la mesa | Old Spanish: ‘interrupt (stop) a story at a point’ Dexa aquí la estoria de fablar | ‘to interrupt an event’ Dejó de sufrir | ‘to maintain an event’ No dejó de fumar ni un momento | ‘To say or do something’ No dejes de ir No puedo dejar de admitir |

| Syntax | suject [+animate] + dejar + DO + locative complement | Suject [+/− animate] + dejar + locative complement (ø/a/de) + PP (de/a INF) | dejar de + INF | NEG dejar de + INF | AFF/NEG dejar de + INF Auxiliary verb + dejar de + INF |

| S XIII & XIV. INF that mainly express ‘telling a story’ (decir ‘to say’, contar ‘to tell’, hablar ‘to speak’) | Other types start consolidating (processes, accomplishments, non-permanent states) | Processes, accomplishments, non-permanent states | inf = achievement or state Often, a temporal expression delimits the duration of the infinitive. Dejar de + inf is often preceded by another auxiliary verb (auxiliary chains) | ||

| Lexicon | Grammar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parar de+ INF | STAGE 1 Etymon | STAGE 2 Supporting construction | STAGE 3 Interruptive Verbal periphrasis | STAGE 3–4 Continuative Verbal periphrasis |

| Semantics/pragmatics | parar ‘put in a position’ > ‘to stop physically’ Los comeres delant gelos paravan (Cid) Paravas delant al campeador | Dejar de + INF | ‘to interrupt an event’ (nuance of annoyance; directive speech acts) Para de moverte | ‘to maintain an event’ (nuance of annoyance) No paran de malestar |

| Syntax | parar (tr. V.) + OD + locative complement parar (intr. V.) + locative complement | parar de + INF | NEG parar de + INF | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garachana, M.; Sansiñena, M.S. Combinatorial Productivity of Spanish Verbal Periphrases as an Indicator of Their Degree of Grammaticalization. Languages 2023, 8, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030187

Garachana M, Sansiñena MS. Combinatorial Productivity of Spanish Verbal Periphrases as an Indicator of Their Degree of Grammaticalization. Languages. 2023; 8(3):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030187

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarachana, Mar, and María Sol Sansiñena. 2023. "Combinatorial Productivity of Spanish Verbal Periphrases as an Indicator of Their Degree of Grammaticalization" Languages 8, no. 3: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030187

APA StyleGarachana, M., & Sansiñena, M. S. (2023). Combinatorial Productivity of Spanish Verbal Periphrases as an Indicator of Their Degree of Grammaticalization. Languages, 8(3), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030187