Abstract

Spanish nouns are classified as either feminine or masculine. Although some nouns vary depending on their denotation (such as niño ‘male child’ vs. niña ‘female child’), in most cases a fixed gender is assigned. When lacking an inflectional cue, nouns could variably admit both genders. While alternating gender may be present in standard Spanish (e.g., azúcar moreno ‘brown.m sugar’ vs. azúcar blanquilla ‘white.f sugar’), it predominantly depends on social or geographical factors (e.g., la vinagre ‘the.f vinegar’, el sal ‘the.m salt’ unlike standard el vinagre ‘the.m vinegar’, la sal ‘the.f salt’). Thus, Spanish binary system represents a fork in the road of gender assignment to nouns. Focused on European Spanish, the present study addresses the sociogeographical influences conditioning gender values in Spanish nouns. To the best of my knowledge, no previous research has been systematically conducted on gender assignment in modern Spanish dialects, so my findings shall shed light on how gender values are determined and diffused across rural and urban varieties. Data are retrieved mainly from the Corpus Oral y Sonoro del Español Rural and the Proyecto para el estudio sociolingüístico del español de España y América), as well as other bibliographical and dialectal sources.

1. Introduction

During the middle decades of 20th century, a series of monographs were written focusing on the speech of a small community or limited area. In these works, particular attention was paid to the ‘cambios de género’ (‘grammatical gender changes’), namely, to those nouns that in the local patois or regional dialect were given a different grammatical gender from the standard norm. These ‘gender changes’ were often flagged as ‘vulgarisms’ that the speech community shared with the popular and uneducated register of general Spanish1. Notwithstanding, these descriptions made it possible to grasp or, at least, deduce some dialectal tendencies. So, in western Asturian varieties, terms like sal (‘salt’), miel (‘honey’) or leche (‘milk’) were assigned to the masculine gender, contrary to the standard norm2. At the other end, Aragonese was influenced by Catalan language, as noted in words like the feminine valle3. Furthermore, these monographs offered relevant information about the pervasive feminine gender of -or nouns, such as calor (‘heat’), color (‘color’) or sudor (‘sweat’), in the oriental varieties from the Pyrenees, in the north, to the region of Mucia, in the south4.

Many of the nouns referred to in the aforementioned dialectal descriptions correspond to what is referred to in traditional grammar as ‘sustantivos ambiguos’ (‘ambiguous nouns’)5. Unlike other nouns that, while keeping their formal aspect unaltered, change grammatical gender depending on the properties of their referent, as happens with estudiante (‘student’)6, and unlike those whose meaning changes according to morphological gender, as happens with frente (el frente ‘the.m front’ vs. la frente ‘the.f fore-head’) or cometa (el cometa ‘the.m comet’ vs. la cometa ‘the.f kite’)7, gender alternation in ambiguous nouns does not imply referential or semantic variation. In this class of nouns, gender assignment hinges, thus, on social or dialectal factors (Ambadiang 1999; RAE/ASALE 2009). Despite the crucial role of these external factors, little research has been carried out8 on the geographic distribution of masculine or feminine gender in ambigeneric nouns.

In the present article, we will assume, contrary to recent research, that Spanish has a binary system of grammatical gender9. This system is composed of two genders that we will conventionally refer to as masculine ([m]) and feminine ([f])10. The conventional interrelation between final word markers -o/-a and grammatical gender either masculine or feminine underpins my assumptions about this binary system11. Spanish nouns are assigned an inherent lexical gender even if there is no formal exponent. This covert gender comes to surface in adequate contexts, as happens when a diminutive suffix is adjoined to the nominal base through the prototypical gender exponents in Spanish, e.g., nouns such as coche ‘car’ [m] vs. noche ‘night’ [f], surface their inherent and covert lexical gender with a diminutive, coch-ecit-o (‘car.dim.m’) vs. noch-ecit-a (night.dim.f)12. We accept that ambiguous nouns possess, like other nouns, an inherent and covert lexical gender but lack phonological cues to guide the assignment of masculine or feminine gender. Indeed, this type of nouns usually end in -e or a consonant. Not having any formal help, speakers might find it difficult to mark these nouns, as either masculine or feminine, so it seems somehow arbitrary to assign them to one gender or the other13.

The main goal of this article is to establish the isoglosses of gender variants in ambiguous nouns, focusing on rural and urban varieties of contemporary European Spanish. These varieties arguably represent the final phase of a deeper historical development concerning ‘gender changes’ in Spanish ambiguous nouns and therefore will offer a partial, and perhaps residual, view of their sociodialectal distribution. However, the panorama this variation reveals in 21st century Spanish will allow me to describe modern geolects; furthermore, current variations will make diachronic drifts visible and will open an observational window to ancient dialectal areas and their focal point.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to retrieve the materials to be analyzed and discussed, I have resorted to two well-known oral corpora of contemporary Spanish. The study of rural dialects is based on the Corpus Oral y Sonoro del Español Rural (COSER 2005) ‘Oral and Audible Corpus of Rural Spanish’ (COSER 2005, for its acronym in Spanish). This corpus covers almost 1500 survey points in the Iberian Peninsula and the Islands (Balearic Islands and Canary Islands). The corpus is composed of oral samples lasting about one hour from elderly informants with no social mobility and a low level of literacy (Fernández-Ordóñez 2009a; Fernández-Ordóñez and Pato 2020). The speakers match the prototypical informants of traditional dialectology (Chambers 1995). The applied methodology conforms, however, to the one used in urban sociolinguistics and consists of semi-directed interviews about topics concerning the rural world, the family and life in the past. The survey campaigns have been carried out between the 1990s and the first decades of 21st century. This methodology allows for the comparison of the data with those extracted from the corpus of the Proyecto de Estudio Sociolingüístco del Español de España y América ‘Project for the Sociolinguistic Study of Spanish in Spain and America’ (PRESEEA). This corpus collects a significant sample of sociolects from the main cities of the Spanish-speaking world (Moreno Fernández and Cestero Mancera 2020). For this study, I have limited ourselves to the Spanish cities in the corpus: Alcalá de Henares, Cádiz, Granada, Madrid, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Málaga, Santander, Santiago de Compostela, Seville and Valencia14. The purpose of this contrast is to verify the penetration of vernacular variants in urban sociolects.

Empirical data (see Groups A and B below) are from COSER (2005), and in a second step, each lemma was searched for in the urban corpus. Searches were conducted while taking advantage of the interface of both corpora, which include a lemmatized and tagged transcribed version of the oral interviews. These technical advantages (de Benito Moreno et al. 2016) have been used to extract the occurrences of ambiguous nouns. To retrieve the relevant sequences of nonstandard nominal gender, I employed the following chains: <masculine determinant + feminine noun>; and <feminine determinant + masculine noun>. This search has returned sequences such as los labores or la color. As a complementary method, I have looked for all nouns tagged as ‘common nouns’ (e.g., azúcar ‘sugar’) in the corpora. As the tag is not applied systematically and a number of interesting cases risked being ruled out, I only used of this type of search complementarily.

The search method returned unwanted mismatches not related to the main object of the present study. These results have been eliminated manually, as in most cases, they do not contribute to the delimitation of dialectal areas. Indeed, the search has produced sequences such as aquella apartamento (that.f apartment.m), una baile (a.f dance.m), la catarro (the.f cold.m), un reflexión (a.m thought.f), unos carreteritas (some.m road.dim-f-pl), este época (this.m time.f), los mitades (the.m half.f-pl), la bachillerato (the.f high-school.m), among many other sequences. These mismatches may denote poor knowledge of standard Spanish when spoken by monolingual informants or, in the case of speakers from bilingual communities (mainly, Galicia, the Basque Country, Catalonia, and the Balearic Islands), a low proficiency in Spanish15. I will also not include the conflicts caused by ‘false reanalysis’ that occurs with shortenings, such as motocicleta ‘motorcycle’> moto, fotografía ‘photography’ > foto and radiodifusión ‘broadcasting’ > radio. These shortenings give rise to well-known constructions belonging to ‘vulgar’ and stigmatized registers that use false prefixes, such as este afoto (‘this picture’), los amotos (‘these motos’) o el arradio (‘the radio’). Nevertheless, I have noticed a phenomenon that deserves at least to be mentioned as it reinforces the link between vocalic endings and grammatical gender. I have actually observed cases in which the final -o in radio triggers a masculine agreement (el radio ‘the.m radio.f’). The conflict in gender assignment to feminine nouns ending in -o or to masculine nouns ending in -a is resolved through vernacular sequences such as los manos (the.m-pl hand.f-pl) and los mediodías (the.f-pl noon.m-pl)16.

Even educated speakers hesitate in the gender assignment to nouns beginning with stressed /a/, as they trigger a complex network of analogical relations caused by the use of the article form el17. For this reason, I leave aside gender changes in nouns such as águila ‘eagle’ (un águila a.m eagle.f), agua ‘water’ (un agua a.m water.f), el agüita (the.m water.f), mucho agua (much.m water.f), otro agua (another.m water.f), hacha ‘ax’ (un hachita a.m ax.dim-f) or hambre ‘hunger’ (mucho hambre ‘very hungry’ (much.m hunger.f)). Finally, I will not deal with nouns from Greek origin (Rosenblat 1959, 1962) ending in -ma (el cima the.m top.f), such as las hematomas (the.f hematomas.m), las idiomas (the.f languages.m), alguna programa (some.f program.m), and la reúma (the.f rheuma.m); -icida (las herbicidas the.f herbicides.m); or -sis, (unas analisis ‘some.f analysis.m’, el crisis ‘the.m crisis.f’). The anti-normative feminine gender was maintained in the written register until 18th century, and in my data, it appears to be scattered and in dispersed survey points. These facts, together with the complexity they present, make it advisable to put them aside at this time.

The aforementioned mismatches are mainly due to sporadic deviations or other types of factors not directly relevant to the present research and, for these reasons, have been omitted from the analysis. The relevant material is made up of 69 lemmas (with a total of 312 occurrences) of ambiguous nouns, showing a gender change in rural dialects of European Spanish. These lemmas have been arranged in two large groups, according to their behavior with respect to the standard and written norm (represented here by DLE and DPD). The groups are the following:

| A | arroba (’unit of 12.5 kilos’), (a)trojes (‘barn’), chinche(s) (‘bedbugs’), costumbre(s) (‘custom’), dote(s) (‘dowry’), harina (‘flour’), hortaliza (‘oarch’), hoz (‘sickle’), labores (‘housework’), leche (‘milk’), lentes (‘glasses’), lindes (‘borders’), lombrices (‘worms’), miel (‘honey’), niebla (‘fog’), sal (‘salt’), sartén (‘frying pan’), simiente(s) (‘seed’), trébede(‘trivet’), ubre (‘udder’), uva (‘grape’). |

| B | aceite(s) (‘oil’), acordeón(es) (‘accordion’), afrecho (‘bran’), aguardiente (‘eau-de-vie’) alambre(s) (‘wire’), aljibes (‘cisterns’), almirez (‘mortar’), alrededor (‘surroundings’), animal(es) (‘animals’), arroz (‘rice’), azúcar (‘sugar’), balde (‘bucket’), calentor (‘heating’), calor(es) (‘heat’), canal(es) (‘water lane’), carral(es) (‘barrel’), castañal (‘chestnut’), color (‘color’), cornales (‘yoke’), costillares (‘ribs’), enjambre (‘swarm’), escozor (‘stinging’), forraje (‘fodder’), frescor (‘freshness’), jabón (‘soap’), maíz (‘corn’), melocotón (‘peach’), olivares (‘olive trees’), olor(es) (‘smell’), ordeñador (‘milker’), pringue(s) (‘fat’), puente(s) (‘bridge’), refrán (‘saying’), remolque (‘trailer’), sudor (‘sweat’), valle (‘valley’), vinagre (‘vinegar’), yunque (‘anvil’). |

The first group includes nouns showing the change from feminine (standard norm) to masculine (rural dialects), and is made up of the 20 lemmas detailed in A that have appeared 91 times in the rural corpus. On the other hand, group B is made up of nouns that, in vernacular varieties, are assigned to feminine gender, while they are mostly masculine in the general standard18. This second set contains 39 lemmas that appear more than 220 times. Despite the heterogeneity of these groupings, the normative parameter has allowed me to apply a single and objective criterion to organize the analysis, and to the extent that the academic norm follows external factors (social, geographical, stylistic) to fix gender in this class of nouns rather than an internal linguistic analysis, this criterion will contribute to the main scope of the present work. In the following section, I will conduct a detailed analysis of each group.

3. Results

3.1. Group A

In group A, mass nouns, such as leche ‘milk’ (lat. lacte), miel ‘honey’ (lat. mele) and sal ‘salt’ (lat. sale), are prominent. These nouns are characterized as “synthetic collective”, and their gender already alternated from Latin between neuter and masculine (“alternating neuter”; (Loporcaro 2017, pp. 233–35)). According to the DERom (n.d., s.v.), the western romances (Galician, Portuguese and western Asturian) have preserved the ‘archaic’ masculine gender, while in central romance (French and Italian) present a ‘restored’ masculine. The feminine gender that these terms have in Spanish (or Catalan) is considered an innovation. In addition to being located in western Asturias (1a), the masculine version of these nouns is found in León, Zamora (1b) and Palencia (1c). To these nouns, one could add the collective ubre ‘udder’ (from the neuter lat. ubere), masculine in Salamanca (1d), and even niebla ‘fog’, also masculine in Asturias (1e). The traditional dialectology of Asturias (Álvarez 1949; Rodríguez Castellano 1952; Neira Martínez 1955; Fernández 1960; Álvarez Fernández-Cañedo 1963; Fernández González 1981; Cano González 1978; González Ferrero 1986), León (Zamora Vicente 1960; Borrego Nieto 1996) and Cantabria (García Lomas 1949; Penny 1969; Nuño Álvarez 1996) had limited the area of masculine leche ‘milk’, miel ‘honey’, sal ‘salt’, and ubre ‘udder’. In 21st century varieties, however, the masculine gender of these nouns is in clear regression despite belonging to the Asturian norm (Martínez Álvarez 1996; GLLA 2001, s.v.)19.

Outside these territories, the masculine gender of harina ‘flour’ and uva ‘grape’ is found in Cáceres (2a) and La Rioja (2b). The combination el harina (the.m flour.f) appears in Navarra, Zaragoza, Castellón and Ciudad Real and may be motivated—like el uva (the.m grape.f)—by the initial vowel (even if it is unstressed), as is the case with el arroba (‘el arroba de aceite’ ’12.5 L of oil’) in Almeria. The term hortaliza appears in the masculine with the meaning of ‘orchard’ (2c) in La Rioja, as it does in Caribbean and Central American countries (DA 2010, s.v.).

| (1) | a. | Ese leche tenía que tar… unos días… en un depósito (COSER 0543, Asturias, Santa Eulalia de Oscos, male, age 85, 27 October 2013) |

| that.m milk.f had to stay a few day in a warehouse | ||

| ‘That milk had to stay a few day in a warehouse’ | ||

| b. | Se le echaba grasa también pa que quedara y el miel, todo bien adobao (COSER 4617, Zamora, Mahíde, female, age 70, 5 September 2004). | |

| they also added fat, so that it would remain, and the.m honey.f, all well marinated | ||

| ‘They also added fatand and the honey, so that all would remain well marinated’ | ||

| c. | También en esas artesas, sí después había que echarlo allí el sal, la pimienta y el orégano (COSER 3414, Palencia, Olmos de Ojeda, male, age 69, 25 March 1994). | |

| afterwards it was necessary to pour it there the.m salt.f, the pepper and the oregano | ||

| ‘Afterwards it was necessary to pour it there the salt, the pepper and the oregano’ | ||

| d. | Alguna cosa o una pata, o un ubre que se le hinchaba… también (COSER 3624, Salamanca, Agallas, female, age 80, 24 October 2015) | |

| something, or a leg, or an.m udder.f, that swelled up too | ||

| ‘Something, or a leg, or an udder, that swelled up too’ | ||

| e. | Después vienen a regar los pimientos, los tomates y a recoger, a solfatear pa contra el niebla (COSER 0509, Asturias, Fechaladrona—Villoria (Laviana), woman, age 78, 28 June 2005). | |

| then they come to water the peppers, the tomatoes and to spray against the.m fog.f | ||

| ‘Then they come to water the peppers, the tomatoes and to spray against the fog’ |

| (2) | a. | Con una criba y eso se cernía el harina y luego se masaba, sí, eso lo he hecho yo (COSER 1020, Cáceres, Talaván, female, age 68, 9 March 1991). |

| with a sieve and that was sifted the.m flour.f and then it was kneaded; yes, I have done that | ||

| ‘With a sieve the flour was sifted and then it was kneaded; yes, I have done that’ | ||

| b. | A veces que se vende el vino y a veces que se vende también… uva, el uva también se suele vender, aunque menos (COSER 2515, La Rioja, Sajazarra, female, age 79, 14 July 1992). | |

| sometimes when wine is sold and sometimes grapes, the.m grape.f is also usually sold, but less | ||

| ‘Sometimes when wine is sold and sometimes the grape is also usually sold, but less often’ | ||

| c. | Y los ponían en la finca en el…, en el hortaliza y allá se criaba el injerto (COSER 2501, La Rioja, Ausejo, male, age 87, 5 April 1997 | |

| and they put them on the farm in the.m orchard.f and the graft was raised there | ||

| ‘And they put them on the farm in the orchard and the graft was raised there’ |

Endings with -e or a consonant characterize other terms of group A. Nouns such as (a)troje ‘barn’, chinche ‘bedbug’, costumbre ‘custom’, dote ‘dowry’, linde ‘border’, simiente ‘seed’ and, finally, trébede ‘trivet’ end in -e. The noun troje ‘barn’, of uncertain origin (DECH 1974, troj), has a feminine gender in standard Spanish and is documented as masculine in Albacete and Málaga. The noun chinche ‘bedbug’ maintains the etymological masculine gender (DECH 1974, s.v.) in Badajoz (3a). This location is a vestige of a larger area that included León (Millán Urdiales 1966), Salamanca (Sánchez Sevilla 1928) and Cantabria (Nuño Álvarez 1996)20. The noun costumbre ‘custom’ (3b), resulting from the crossing of the Latin suffixes in -umen and -tudine (Rosenblat 1952), invariably retains the etymological feminine gender in standard Spanish but changes to masculine in Asturias and Galicia (o costume ‘the custom’ in Galician and Portuguese), where it occurred six times, as well as in La Palma, Soria and Gerona (it is extensively masculine in Catalan, see DCVB [1926–1963] 2002, costum). The masculine characterizes northern varieties from west to east (Llorente Maldonado de Guevara 1947; Penny 1969; Ena Bordonada 1976), along with the Canary Islands (Alvar 1959). For terms stemming from Latin’s third declension nouns, such as dote ‘dowry’ (lat. dōte —feminine—) and linde ‘border’ (lat. līmite—masculine, instead—), the standard norm admits both genders (DLE 2014, s.v.), although the educated favor the use of the feminine (DPD 2005, s.v.) for both terms. Los lindes (the.m-pl borders) is recorded only once in Cuenca, while el dote (the.m dowry) shows a greater extension and, in addition to Valladolid, Navarra and the Canary Islands, it is strongly located in the region of La Jara (3c) (as shown in Figure 1 in red). Simiente (‘seed’) is mostly masculine gendered in Huesca, but it is also documented in Cádiz (3d) and Burgos21. Finally, the masculine use of the term trébede ‘trivet’ is located in Zamora, while the ambigeneric lente ‘glasses’ agrees in masculine (los lentes ‘the.m-pl glasses’) in Bajo Ampurdán.

| (3) | a. | Tenía que lavarlas [= las sillas] y sacudirlas así en el suelo, porque los chinches te comían el culo (COSER 0726, Badajoz, San Francisco de Olivenza, female, age 73, 17 April 2010) |

| I had to wash them and shake them on the floor like this, because the.m-pl bedbugs.f-pl eat your ass | ||

| ‘I had to wash the chairs and shake them on the floor like this, because bedbugs eat your ass’ | ||

| b. | Yo así la [=la carne] pongo y sin embargo en Ólvega la refríen y eso ya va en los costumbres (COSER 3924, Soria, Beratón, female, age 77, 26 April 2008 | |

| I put it that way and yet in Ólvega they fry it, and it hinges on the.m-pl customs.f-pl | ||

| ‘I put the meat that way, but they fry it in Ólvega; it hinges on the customs’ | ||

| c. | Los daban los dotes a los novios, lo mismo a la novia que al novio le daban el dote (COSER 4225, Toledo, Olías del Rey, male, age 73, 2 December 1995) | |

| they gave them the.m-pl dowries.f-pl to the bride and groom, the same to the bride as to the groom the.m dowry.m | ||

| ‘They gave the dowries to the bride and groom, the same dowry to the bride as to the groom’ | ||

| d. | Eso echa un tallo largo pa arriba las que quedan y ya luego echa el simiente y con el viento pos se zarandea (COSER 1102, Cádiz, Algar, female, age 79, 17 September 2012) | |

| that throws a long stem, the remaining ones, and then the.m seed.f sprouts and due to the wind it shakes | ||

| ‘The remaining ones throw a long stem, and then the seed sprouts, and shake because of the wind’ | ||

| (4) | a. | Se dedicaba a los labores de casa (COSER 3503, Pontevedra, Galegos, male, age 81, 21 October 2017). |

| she did the.m-pl work.f-pl of the house | ||

| ‘She did housework’ | ||

| b. | Procuraba hacer los labores así pequeños, ¿no? (PRESEEA, Santiago de Compostela, female, age 70, lower class, 18 April 2009 | |

| I tried to do the.m-pl work.f-pl so little.m-pl, no? | ||

| ‘I tried to do little housework, right?’ | ||

| (5) | a. | Pero entonces en el sartén, hacémoslo con acei[te]… (COSER 0506, Asturias, Alea—Linares, female, age 74, 29 June 2005). |

| but then in the.m pan.f, we do it with oil | ||

| ‘But we do it with oil in the frying pan’ | ||

| b. | Lo pongo todo en un sartén (PRESEEA, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, male, age 22, lower class, 26 July 2007) | |

| I put it all in a.m pan.f | ||

| ‘I put it all in a frying pan’ |

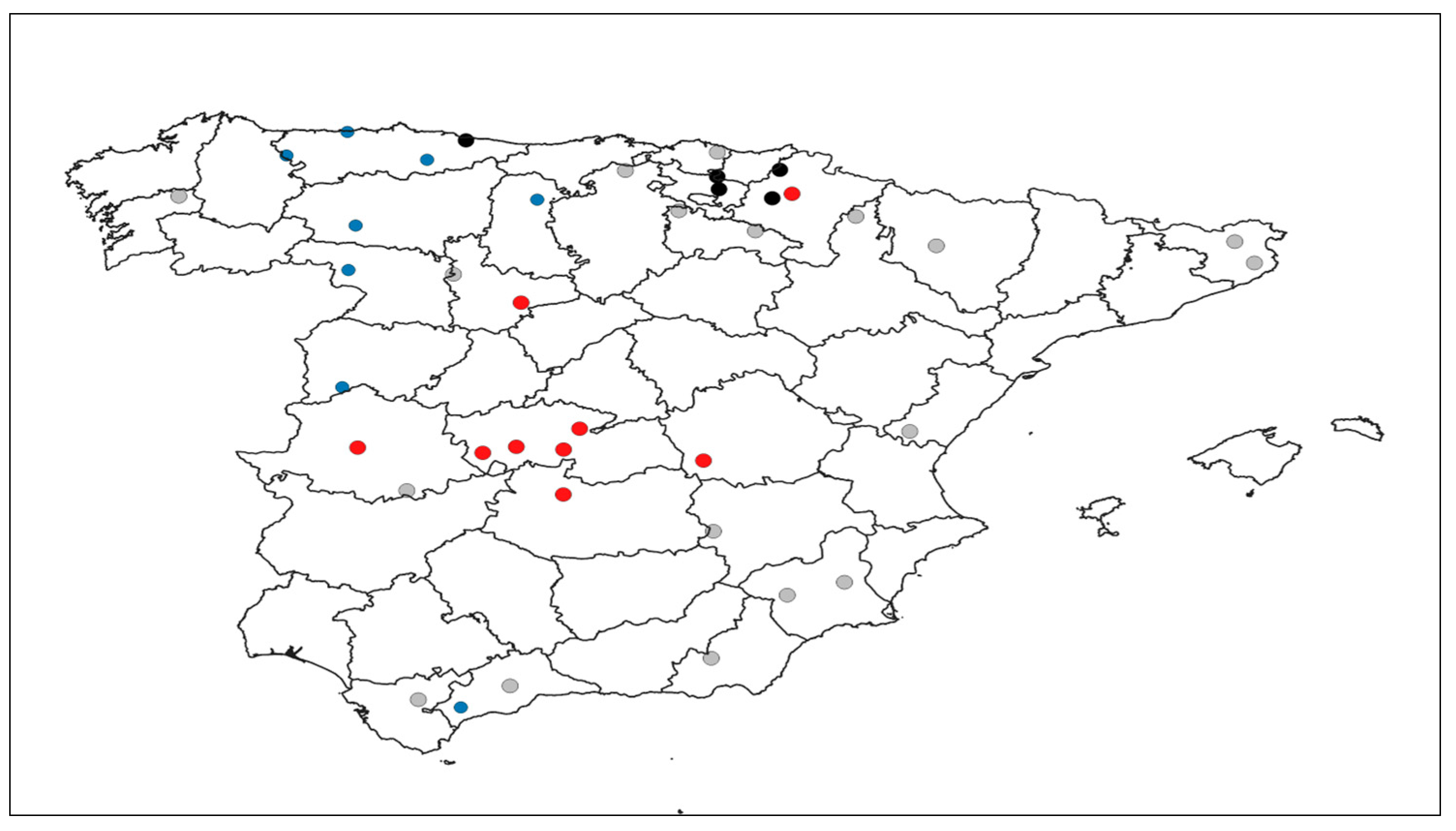

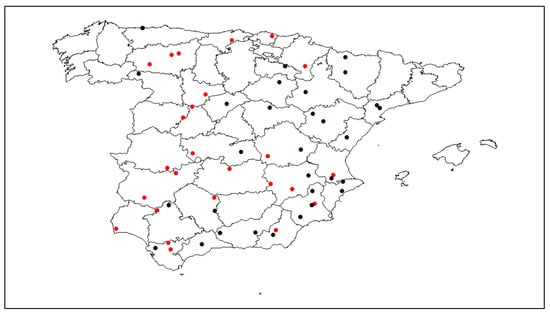

Figure 1.

Masculine gendered nouns in rural dialects of European Spanish.

Nouns such as almirez ‘mortar’, hoz ‘sickle’, labor ‘housework’22, lombriz ‘worm’23 and sartén ‘frying pan’ end in a consonant. The term hoz ‘sickle’ (from the feminine lat. falce) in the masculine is found twice in Murcia and in Galicia, where I also localize labor (‘housework’) in the masculine (another example appears in Vizcaya). Contrary to the literature, masculine labor is not found in Asturias (Martínez Álvarez 1996), León (Álvarez 1949) or Salamanca (Llorente Maldonado de Guevara 1947), but, in turn, it is documented—only once, though—in the urban speech of Santiago de Compostela used by a lower-class old woman who continues to employ rural usage in an urban environment. The noun sartén ‘frying pan’ (lat. sartagine) invariably retains the etymological gender in the standard norm, but exhibits the masculine gender in various dialects of European and American Spanish (Montero Curiel 2019)24. In my data, sartén is masculine in Asturias (5a) but especially in Basque territories (Álava, Guipuzcoa, Navarra). This anti-normative gender is attested, though only once, in the basilects of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (5b).

As the map shows (Figure 1), the nouns of anti-normative masculine gender do not trace precise and coherent limits, which could allude to the fact that these nouns are vestiges of older stages (such as el simiente (the.m seed.f) or el costumbre (the.m custom.f)), obeying local norms interfered by language contact (such as the case of labor) or are used residually (el trébede, el hortaliza) (grey dots in the map). However, the analysis of these nouns allows to outline three dialectal micro-areas in which gender changes seem to occur systematically. The first one concerns the ‘synthetic collective’, such as leche ‘milk’, miel ‘honey’ and sal ‘salt’, as well as other similar nouns (niebla ‘fog’ and ubre ‘udder’), and includes northern territories with western Asturian as the main bastion of these archaic masculine (blue dots). The second is based on the masculine use of words such as dote ‘dowry’ and linde ‘border’ and is concentrated in Toledo (red dots). The combination el sartén (the.m frying-pan.f) depicts the third micro-area concerning the Basque-speaking territories (black dots), although its occurrence in the insular Spanish of the Canary Islands (not to mention America) shows that the change toward the masculine is possible in other areas. These microareas are in clear regression in 21st century rural Spanish, but they bring to light historical isoglosses and, regarding gender changes, signal focal points of diffusion. For this reason, these conclusions will serve as a fundamental starting point for a diachronic study.

3.2. Group B

Group B includes lemmas ending in -e, such as the following: the Arabism aljibe ‘cistern’ is feminine in the Canary Island of Lanzarote; balde ‘bucket’—of unknown origin—triggers a feminine agreement (una balde ‘a.f bucket.m’) in Valle de Cerrato (Palencia)25; puente ‘bridge’ (lat. ponte) whose invariably masculine gender in standard Spanish continues the etymological gender, but, as it happens in the lateral Romance languages (Portuguese, Galician, Romanian) (DERom n.d., s.v.), appears as feminine in medieval and classical Spanish. In the feminine, it is located, besides western Toledo and Guipuzcoa, in Zamora (6a), vestigial territory of a wider area that included Asturias (Rodríguez Castellano 1952; Cano González 1978), Cantabria (Penny 1969), León (Fernández 1960), Zamora (González Ferrero 1986), Salamanca (Llorente Maldonado de Guevara 1947; Herrero Ingelmo 1996) and Cáceres (Montero Curiel 1997). Although there is no lack of documentation in the eastern zone (Calero López de Ayala 1981), la puente (the.f bridge.m) is associated with northwestern territories. Perhaps due to a sporadic gender change or lexically motivated by the ellipsis of máquina ‘machine’, remolque ‘trailer’ appears in the feminine in Lorca (Murcia)26. In Lérida (Torrebesses), the noun valle ‘valley’ is occurs up to nine times as feminine, due to the influence of the etymological gender that this term has in Catalan (la vall ‘the.f valley’). This noun is included as feminine in dialectal monographs dealing with Aragonese varieties (Alvar 1948; Zamora Vicente 1960; Laguna Campos 2009). In words like puente ‘bridge’ and valle ‘valley’, the feminine (whether innovative or conservative) evokes an older phase of language and points to, respectively western and eastern varieties located at the extremes of the northern iberorromance continuum. The example of (6b), which could constitute one of the last documentations of yunque ‘anvil’ as feminine, confirms the relationship of this grammatical gender with Asturian and, in general, Cantabrian dialects (Rodríguez Castellano 1952; Fernández González 1959; Penny 1969), where cases of hypercharacterization (yunca) are found27.

| (6) | a. | Un día estuve yo mirando, que anduvieron ahí junto a la puente […]. Pues esa presa, esa, dice que si la dejan, que se la lleva el río, que lleva la puente (COSER 4622, Zamora, Trefacio, female, age 77, 9 May 2004). |

| one day I was looking, they were there next to the.f bridge.m […].They say that if they leave the dam, the river will carry it away, it will carry the.f bridge.m | ||

| ‘One day I was looking, they were next to the bridge […].They say that if they leave the dam, the river will carry the bridge away’ | ||

| b. | Un martillo, una yunque, porque la gadaña como es muy fina… (COSER 0543, Asturias, Santa Eulalia de Oscos, male, age 85, 27 October 2013). | |

| a hammer, a.f anvil.m, because the scythe like is very fine | ||

| ‘A hammer, an anvil, because the scythe is very fine’ | ||

| c. | Aquí hacen el chorizo y la morcilla […]. De la sangre y la pringue del tocino. La pringue del tocino, la pringue que le quitan a la carne… (COSER 1107, Cádiz, Espera, female, age 69, 17 September 2012). | |

| they make chorizo and black pudding […]. We use the blood and the.f smear.m of the bacon. the.f smear.m of the bacon, the.f smear.m that they remove from the meat’ | ||

| ‘They make chorizo and black pudding […]. We use blood and bacon smear. Bacon smear they take from the meat’ |

If we consider pringue ‘fat’ as a postverbal formation (pringu-e < pring-ar), -e should be segmented as a vocalic suffix28. The academic norm admits both genders (DPD 2005, s.v.) without favoring either of them. Due to its denotation as a mass noun (‘fat’), pringue could be related to other nouns with similar semantics and tend toward the feminine gender, such as aceite ‘oil’ or vinagre ‘vinegar’—which I will address below— although it presents—as we will see shortly—a diverse geographical distribution since its appearances in the feminine form are concentrated in southern varieties of Extremadura (three times) (Montero Curiel 1997), which I did not localize it in Southern Salamanca as Sánchez Sevilla did (1928), and Castilla La Mancha (eight times), which does not appear in Murcia—see instead García Cotorruelo (1959)—and, especially, in Andalusia (sixteen times). This having been said, these nouns ending in -e, as was the case with the group A masculine nouns, show hesitation in assigning grammatical gender in the absence of overt morphophonological cues.

Representing nouns ending in -ambre and the alternating gender these nouns, due to the influence of the feminine in -umbre, (Rosenblat 1952), group B contains containing words such as alambre‘wire’ and enjambre ‘swarm’ (among others, Sánchez Sevilla 1928; González Ollé 1964; Cano González 1978; Montero Curiel 1997). These voices, masculine in standard Spanish (DLE 2014, s.v.), come from the Latin neuters aramine and examine, respectively (DECH 1974, s.v.) and occur as feminine, the former in La Rioja and Huesca and the latter in Ávila (7 times).

With the endings -al/-ar, the following nouns of non-canonical feminine gender are documented: canal ‘waterlane’ could be taken as a paradigmatic example of the semantic change resulting from gender variation in the academic norm (DPD 2005, s.v.), and in the feminine, it frequently alludes to the meaning of ‘res abierta en canal’ (a meaning often activated in the COSER interviews), while the masculine is preferred, with the meaning of ‘artificial water channel’. With this meaning, but with non-canonical feminine gender, I found it in Teruel (una canalica ‘a.f canal.dim-f’), Palencia and Madrid, as well as in Catalan-speaking areas (Mallorca, Valencia and Alicante), undoubtedly due to interference with Catalan, where the feminine prevails (DCVB [1926–1963] 2002, s.v.). Related to wine, the term carral ‘barrel to carry wine’ is used in the masculine as the general standard and feminine29 in Tierra de Campos (11 occurrences). The noun castañal (una castañal ‘a.f chestnut-tree.m’) is recorded in the feminine in Asturias (la peral ‘pear tree’, la ma(n)zanal ‘apple tree’, la nogal ‘walnut tree’, la cere(i)zal ‘cherry tree’, la piescal ‘peach tree’, la ciruelar ‘plum tree’, la guindal ‘cherry tree’) have in Asturleonese varieties (Alonso Garrote 1947; Llorente Maldonado de Guevara 1947; Rodríguez Castellano 1952; Neira Martínez 1955; Fernández González 1959; Álvarez Fernández-Cañedo 1963; Cano González 1978; González Ferrero 1986; Herrero Ingelmo 1996). In the very same territories, the non-canonical feminine of the collective noun cornal (‘yoke’) is recorded: unas cornales30. Olivar ‘olive tree’ is feminine (las olivares ‘the.f-pl olive-tree.m-pl’) in Albacete and also costillar appears sporadically with this gender (las costillares ‘the.f rib.m-pl’) in Jaén31. Due to the Galician influence, forraje ‘fodder’ is used as feminine in Lugo.

Within group B, two sets of nouns stand out. Contrary to the diversity of terms discussed so far, these two sets present a certain homogeneity. The first set includes nouns that denote substances such as aceite ‘oil’, afrecho ‘bran’, aguardiente ‘eau-de-vie’, arroz ‘rice’, azúcar ‘sugar’, maíz ‘corn’ and vinagre ‘vinegar’. Except for afrecho ‘bran’ (lat. affractum), the rest of these nouns coming from different sources have been recently incorporated into the Spanish lexicon. The non-Latin origin of these nouns entails that the restructuring of Latin declensions cannot explain, by itself, gender changes and, therefore, suggests the need to investigate the deep motivation that, within the Spanish nominal system, underlies these reclassifying gender phenomena. The term aceite ‘oil’ comes from the Hispanic Arabic azzáyt and is exclusively masculine in the academic standard (DPD 2005, s.v.). In the feminine, it is located in the rural sociolects (7a) of Asturias (three times), León (four), Cantabria and Badajoz, as well as in Castilla La Mancha (two times), Murcia and Alicante (8 times). It penetrates the urban speech of the Canary Islands (7b), generally in speakers with a low educational level (seven out of eight occurrences). Azúcar ‘sugar’ is another non-canonical gendered noun documented in the urban sociolect of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (8b) and Málaga. This term, an emblem of ambiguous nouns in Spanish (Rini 2014), comes from the Hispanic Arabic assúkar, where it had masculine gender, a gender that is preserved in major Romance languages (Portuguese, Catalan, French and Italian) (DECH 1974, s.v.) and, in effect, predominates in Spanish when the noun occurs without a modifier (azúcar), is pluralized (los azúcares) or is used with the technical meaning of ‘carbohydrate simple’ (the postposition of an adjective—azúcar prieta—favors, on the other hand, feminine gender). The combination of azúcar with feminine determiners such as la azúcar (the.f sugar) is attested in León (five times), Valladolid (two times), La Rioja, Valencia, Murcia, Seville (five times), Málaga, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (two times) and Lanzarote (I did not encounter the feminine in northeastern varieties against Badía Margarit 1950 or Ena Bordonada 1976). Examples like the one in (8a) clearly show how feminine azúcar triggers feminine agreement in target expressions: la azúcar la traía empaquetada (the.F sugar it.F brought packaged.F). The rest of the anti-normative feminine nouns are not registered in urban sociolects, but they in fact show a discrete extension in the rural ones. Arroz (from the Hispanic Arabic ‘aruzz), masculine in the standard, appears as feminine in Huelva and Murcia (2 times) (9a). The word maíz ‘corn’ (from the Taino mahis), an Americanism of great fortune in European languages, triggers a feminine agreement in Cantabria (9b), Vizcaya (four times) and Córdoba, while the Catalanism vinagre ‘vinegar’, masculine in educated usage (DPD 2005, s.v.), appears only once as feminine (9c) in Salamanca, although its extension might have been greater in the past (García de Diego 1978).

| (7) | a. | La aceite, echas, fríe, que tenga bien caliente el aceite, que esté bien, echas un cachín de pan, pa requemala bien, pa quitarle… esa fuerza que lleva la aceite (COSER 0523, Asturias, Cadavedo (Valdés), woman, age 88, 26 October 2013). |

| the.f oil.m, add, fry, make sure very hot the oil, that it is well, add a piece of bread, to fry it well, to take away that strength that carries the.f oil.m | ||

| ‘Add the oil, fry it, make sure the oil is very hot, at the right temperature, add a little bit of bread, fry it well, take away the strength that the oil has’ | ||

| b. | Le pongo el pimentón, aceite, y vinagre, […], entonces la aceite, en vez de ponérsela así de montón, voy dándole vueltas y la aceite se la voy poniendo, para que seee bata bien (PRESEEA, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, woman, age 59, lower class, 19 September 2006) | |

| I put the paprika, oil, and vinegar, […] then the.f oil.m, instead of putting it-f like that in a lot, I stir it and the.f oil.m I put it-f, so that everything is mixed well | ||

| ‘I put the paprika, oil, and vinegar, […] then the oil, instead of putting it like that in a lot, I stir it and I put the oil slowly, so that everything is mixed well’ | ||

| (8) | a. | En el pueblo venía con una cestita aquí debajo y la azúcar la traía empaquetada en, en, en unos sobritos chiquititos (COSER 5322, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Agaete, female, age 84, 4 February 2017). |

| in the village he came with a little basket down here and the.f sugar.m it-f brought packaged-f in some little bags | ||

| ‘In the village he came with a little basket and he brought the sugar packaged in some little bags’ | ||

| b. | Y después la escurro bien bien, y en caliente la escacho y le pongo la azúcar, bastante dulcita, le pongo, almendras molidas… (PRESEEA, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, female, age 82, middle class, 14 February 2007). | |

| and then I drain it well well, and when hot I cook it and add the.f sugar.m, well sweet-f, I add ground almonds | ||

| ‘And then I drain it well, and when hot I cook it and add the sugar, quite sweet, I add ground almonds’ | ||

| (9) | a. | El conejo, pos lo mismo, pa hacer la arroz, pa…, pa’l guisajo, pa…, pa hacer patatas fritas con conejo (COSER 3106, Murcia, Lorca, male, age 79, 9 October 2013) |

| the rabbit, the same thing, to make the.f rice.m, for the stew, to make fried potatoes with rabbit | ||

| ‘The same thing with the rabbit, to make rice, a stew, fried potatoes with rabbit’ | ||

| b. | La cebada y la maíz es lo que más se les da (COSER 1232, Cantabria, Vega de Pas, male, age 63, 7 May 1993). | |

| the barely and the.f corn.m is what they are given the most | ||

| ‘Barley and corn are what they eat the most’ | ||

| c. | Lo que se quiera, pa las tripas lo que se quiera, porque la vinagre, eso no tiene que ver, porque ahí no hay nada de importancia (COSER-3601, Salamanca, Alaraz, female, age 85, 9 December 1994) | |

| whatever you want, whatever you want for the guts, because the.f vinegar.m has nothing to do with it, because there is nothing important there | ||

| ‘For the guts, whatever you want, because vinegar has nothing to do with it, because there is nothing important there’ |

The use of these nouns as feminine is described in dialectal monographs from the northwestern area (Sánchez Sevilla 1928; Llorente Maldonado de Guevara 1947; García Lomas 1949; González Ollé 1964; Millán Urdiales 1966; Penny 1969; Cummins 1974; González Ferrero 1986), and its extension must be related to the ‘strange’ mismatch studied in Fernández-Ordóñez (2015). According to her, canonically masculine-gendered mass and abstract nouns triggers feminine agreement in evaluative quantifiers (mucha maíz (much.f corn.m) ‘lot of corn, mucha trabajo (much.f work.m) ‘lot of work’)32. The feminization of mass nouns may be due to the individualizing properties that the exclusive feminine confers to them in the referential act, a hypothesis suggested by Fernández-Ordóñez (2015). This hypothesis also agree with the anomalous agreement that Fábregas and Pérez (2008) found with adverb mucho ‘much, very’ when modifying mass and abstract nouns in sequences like esto lo he hecho con mucha mejor intención ‘I have done this with much better intention’. The mystery of feminine agreement does not seem to be limited to evaluative quantifiers and could also concern other determiners, as examples like those in (7–9) show. A possible hypothesis would consist of the individualizing and specifying referential properties that feminine gender confers onto nouns that, like mass and abstract ones, are located at the lowest end of the individuation scale (Luraghi 2011).

Although the hypothesis just advanced cannot be explored in the present work, the vernacular feminine shown by -or abstract nouns in rural dialects of European Spanish will play a fundamental role in the discussion. In group B, it is possible to observe a good number of nouns ending in -or (calentor ‘heater’, calor(es) ‘heat’, color ‘color’, escozor ‘stinging’, frescor ‘freshness’, olor(es) ‘smell’ and sudor ‘sweat’, to which I add alrededor ‘surroundings’ and ordeñador ‘milker’33). According to Rosenblat’s (1952) hypothesis, in the history of Spanish, there was a reaction that restored etymological masculinity to nouns ending in -or—the only gender accepted by the academic norm—against the vernacular drift to transform the masculine gender into the feminine34. In my data, feminine-gendered -or nouns are documented in different points of eastern territories from Alto (10a) and Bajo (10b) Aragón to Murcia (10c), confirming the link between feminine nouns ending in -or nouns and oriental varieties (García de Diego [1918] 1990; García Cotorruelo 1959; Haensch 1960; Ena Bordonada 1976; Calero López de Ayala 1981; Domene Verdé 2010). The feminine use of nouns, such as calor ‘heat’ and color ‘color’, has also been attested to in western varieties (Sánchez Sevilla 1928; Llorente Maldonado de Guevara 1947; Álvarez 1949; García Lomas 1949; Rodríguez Castellano 1952; Álvarez Fernández-Cañedo 1963; Millán Urdiales 1966; Penny 1969; Cano González 1978; González Ferrero 1986; Herrero Ingelmo 1996). This extension recalls older linguistic periods and would support the hypothesis of a deeper and more essential action of the anti-etymological tendency to convert the terms derived from the Latin masculine ending in -ore into the feminine in the history of Spanish. The noun calor ‘heat’, located in rural (11a) and urban (11b) sociolects, stands as the main witness of the diffusion that this gender-changing innovation might have been reached in the past35.

| (10) | a. | Eso sí que era una limpieza y echaba una olor más rica la ropa esa (COSER-2207, Huesca, Loporzano, female, age 85, 21 April 2007). |

| that yes that it was a cleaning and the clothing made a.f smell.m more fresh-f | ||

| ‘That sure was cleaning and the clothes made a fresher smell’ | ||

| b. | Con la frescor de la noche estaba el agua fresca a todas horas (COSER-4117, Teruel, Fuentes Claras, female, age 75, 5 May 2001). | |

| With the.f freshness.m of the night water was fresh at all hours | ||

| ‘With night coolness there was fresh water at all hours’ | ||

| c. | En la secadora, iguá que las capas de los…, los toreros, tiesas, prenden la sudó que habíamos sudao (COSER-3106, Murcia, Lorca, male, age 79, 10 September 2013). | |

| In the dryer, just like the capes of bullfighters, stiff, turn on the.f sweat.m that we had sweated | ||

| ‘In the dryer, just like the capes of bullfighters, stiff, turn on the sweat that we had sweated’ | ||

| (11) | a. | La calor es seca, porque en estas ca-, en estas capitales es la calor, pero es sudá, así blanda, pero aquí es que la calor es seca (COSER-0211, Albacete, Higueruela, female, age 80, 25 April 2009). |

| the.f heat.m is dry-f, because in these capitals it is the.f heat.m, but it is sweated-f, so soft-f, but here the.f heat.m is dry-f | ||

| ‘The heat is dry, because in these capitals; it is the heat, but it is sweaty, so soft, but here the heat is dry’ | ||

| b. | Saliendo sales aprovechando cuando yaaa se pasa la calor (PRESEEA, Sevilla, male, age 56, lower class, 20 December 2009). | |

| going out, taking advantage when already the.f heat.m is over | ||

| ‘Going out, taking advantage of when the heat is over’ |

In oriental varieties, there are feminine uses of nouns ending in -ón, such as acordeón ‘accordion’ (Álava), jabón ‘soap’ (la jabón ‘the.f soap.m’—and also esa refrán ‘that.f saying.m’—in Zaragoza) and melocotón ‘peach’ (Albacete)36.

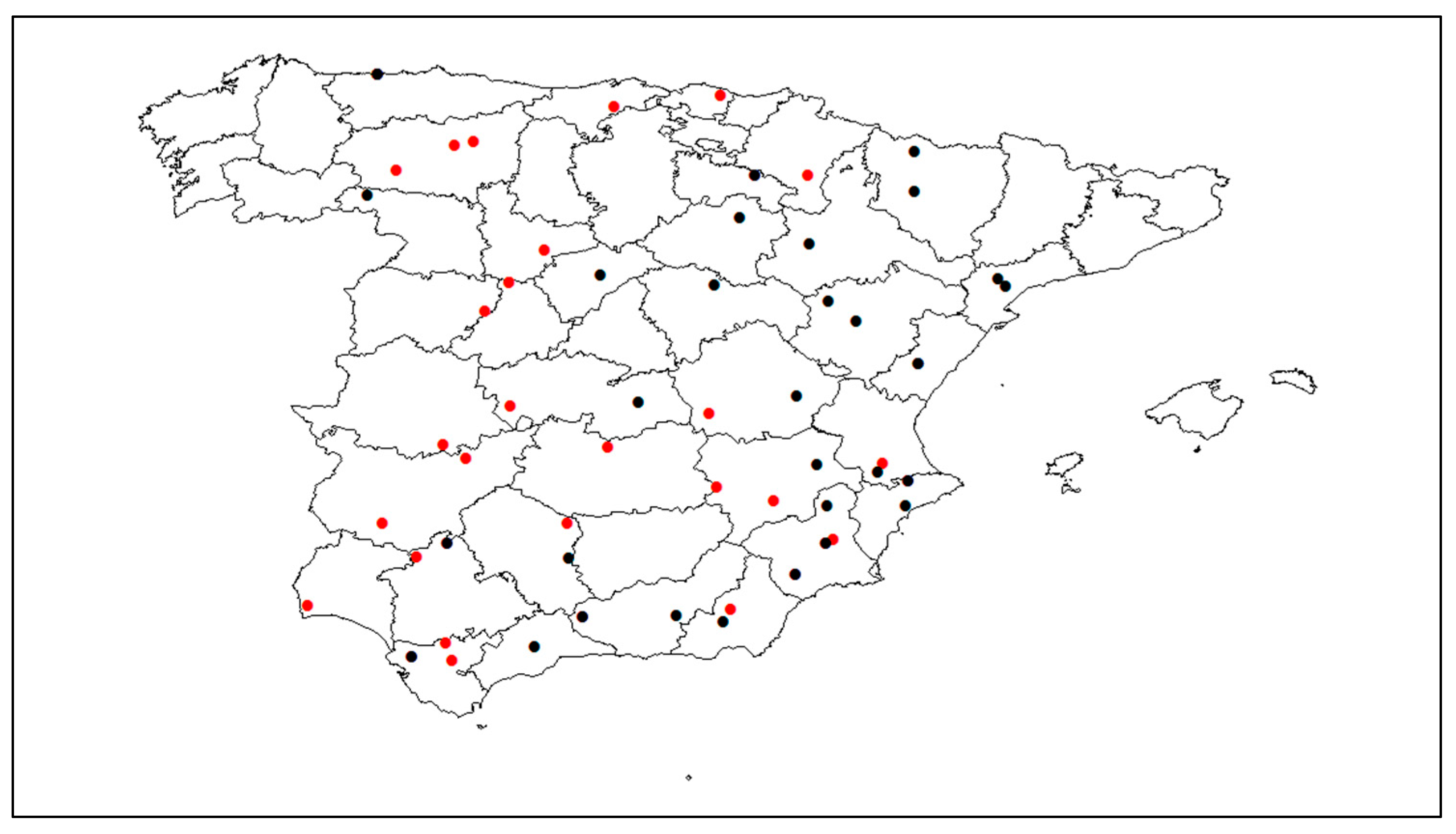

The map of non-canoncial feminine nouns (Figure 2) outlines two large complementary areas. The first one (red dots in the map) covers mass nouns that are documented in feminine in contemporary dialects, while the second (black dots) situates abstract nouns ending in -or. A thorough investigation is required to find out if the feminization of mass (northwestern zone) and abstract nouns (northeastern zone) is caused by a common tendency attributable to the individualizing properties of this grammatical gender or if it responds in each territory to different motivations relating to, on the one hand, mass denotation and, on the other hand, the fate of the -or suffix in (especially, Eastern) Ibero-Romance languages.

Figure 2.

Feminine gendered nouns in rural dialects of European Spanish.

4. Discussion

In this article, I have assumed that Spanish has two grammatical genders, so the nouns of this language are assigned to masculine ([m]) or feminine ([f]) gender. In Spanish, the assignment of gender is carried out in a relatively transparent manner and is largely guided by word final vowel (namely, -o or -a). Nevertheless, ambiguous nouns—the main concern of the present article—prominently lack overt phonological cues to guide gender assignment, and so, phonological conditions do not provide a safe ground to assign gender. For this reason, the standard norm seems to assign gender to these ambiguous nouns in a quite arbitrary way. Regarding the semantic properties of ambiguous nouns, this noun class refers to a wide range of meanings since they refer to individual entities (sartén ‘frying pan’) or collective entities (dote ‘dowry’), uncountable (azúcar ‘sugar’) or abstract notions (calor ‘heat’). Nor does etymology function as a safe method for gender assignment since a large part of the lemmas studied above come from Latin nouns of the third declension (chinche ‘bedbug’, dote ‘dowry’, puente ‘bridge’). The third declension is known to give rise to “diverging genders” (Maiden 2011) in Romance languages. However, I have also noted how a number of ambiguous nouns in modern dialects of European Spanish stem from other languages (aceite ‘oil’, azúcar ‘sugar’, maíz ‘corn’, vinagre ‘vinegar’, just to mention the most salient ones) and have been recently incorporated to Spanish vocabulary. In short, ambiguous nouns do not provide with any clear and overt phonological, semantic or etymological cue for gender assignment. For this reason, it is worth asking which reasons explain how a fixed or preferred gender is given to these nouns in the educated and written variety of Spanish.

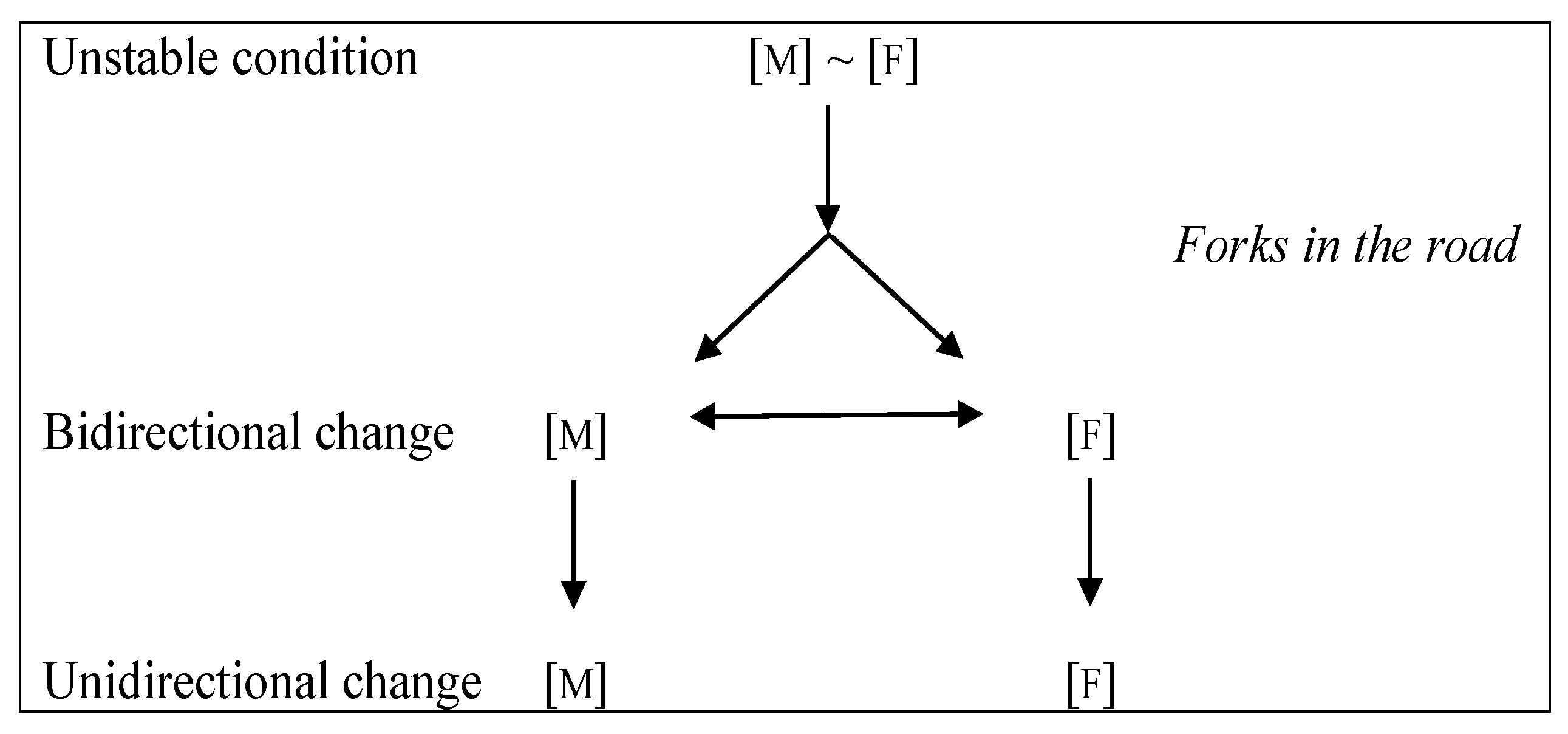

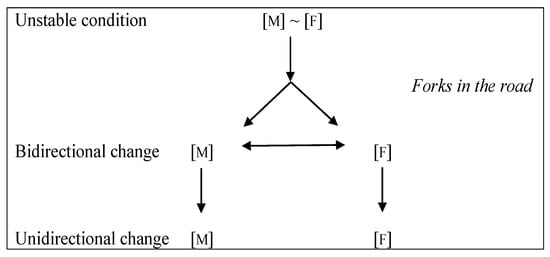

Considering a binary system of grammatical gender, speakers of a speech community face a double alternative ([m] and [f]) when trying to assign gender to nouns that do not offer clearly defined morphophonological cues. Thus, speakers must face a fork in the road. Labov (2010) applies this model to explain how neighboring dialects diverge in a situation of unstable conditions promoted by a process of language change and uses it to account for vowel shifts in North American English. Briefly, the model attempts to explain what motivates the choice between two equivalent and valid solutions (A or B) resulting from change. The Labovian model is modified for our current purposes in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Two-stage model of dialect divergence (modified).

If we turn to the maps in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 (Figure 1 and Figure 2), we observe the scarcity or absence of occurrences of anti-normative genders in the center of the peninsula. This suggests that the academic norm has emanated from this area and with the main motivation to move away from the most dialectically marked cases. According to the observations the DPD has made regarding words such as calor (‘heat’), color (‘color’) or olor (‘smell’), we notice that their use as feminine was common until classical Spanish. At this time, the intervention of a supralocal and—perhaps—external norm (Latinizing? Italianizing?) determined the fate of -or nouns. The masculine gender was imposed—restoring by the way the etymological gender—onto this kind of noun. A similar explanation might be put forward to most of the nouns analyzed in this article. In absence of a complete and systematic historical study, it is possible to hypothesize that the current norm begins in the 16th and 17th centuries, banishing dialectally marked genders and favoring others on social or stylistic grounds. These dates point to the time Madrid was definitively established as the capital of Spain (1561), which is when the normative filter (for the ‘norma madrileña’, see Santiago and Gisbert 2002) started to account for the fluctuating genders of ambiguous nouns. In some cases, etymological criterion prevailed to assign gender to words such as costumbre (‘custom’), dote (‘dowry’), sartén (‘frying pan’) or puente (‘bridge’), yet it stands out, and this is evident in those nouns whose final fixed gender differs from the etymological one (labor ‘housework’, yunque ‘anvil’), and by how this supralocal norm strives to draw away from the more dialectalized and peripheral options. This mechanism of dialectal divergence—a well-known phenomenon in the dynamics between standard and dialectal norms (Molina Martos 2020)—is set in motion to replace archaic, medieval usage, a usage distanced from the courtly habits of the new capital.

However, Labov (2010, p. 156) wonders, in situations of dialectal divergence, about the ’small forces [that] may lead the linguistic system to follow one route or the other‘. The Madrid norm is guided by socio-stylistic considerations, by language fashions and, lastly, by external factors. It will be interesting to understand the deep motivations of gender changes in Spanish dialects. In nouns moving from the feminine (standard) to the masculine (vernacular) gender (group A), customary, traditional, and local uses seem to prevail, as is the case of dote (‘dowry’), linde (‘border’), simiente (‘seed’), among others. This explanation can also be applied to nouns such as puente (‘bridge’) or valle (‘valley’) that materialize the inverse change (canonical masculine > heterodox feminine). Alternations between neuter and masculine and the link of this “alternating neuter” with nominal denotation (Loporcaro 2017) undoubtedly explains the cases of leche (‘milk’), miel (‘honey’) and sal (‘salt’). In order to move away from dialectal uses, the standard has assigned—contrary to other Romance languages—the feminine gender to these nouns, drawing—paradoxically—on the vernacular tendency of using the feminine with mass nouns, such as aceite (‘oil’) or maíz (‘corn’).

The interplay between the feminine gender and mass or abstract semantics that I noted in two significant subsets of group B deserves close attention. The feminization of these nouns must be considered an innovation of Ibero-Romance vernaculars, with or without continuation in other Romance languages. In this way, I have observed a consistent trend toward the feminization of nouns, such as aceite (‘oil’), azúcar (‘sugar’), maíz (‘corn’) or vinagre (‘vinegar’), in western territories from north to south, although other cases may be found in other areas. Much has to be said about how, and to what extent, these mismatches (la aceite ‘the.f oil.m’, la maíz ‘the.f corn.m’, la vinagre ‘the.f vinegar.m’) are related with other ’strange misagreement‘ phenomena (mucha trabajo (much.f work.m) ‘a lot of work’, mucha máiz ‘a lot of corn’ (much.f corn.m)) localized in the northern territories, as described by Fernández-Ordóñez (2015). In the eastern area, innovative changes affecting nouns ending in -or stand out. The spread of la calor (the.f heat.m) throughout Andalusia and even in northwestern and central varieties suggests a greater diffusion of these feminine-gendered -or nouns in ancient stages of Spanish. Unlike the mass nouns just mentioned, the nouns ending in -or nouns show more uniformity, as they come mainly from Latin masculine-gendered nouns, share the identical final suffix, and denote abstract notions. The relationship between abstract nouns and mass nouns has yet to be determined (Bosque 1999), but both lexical classes share the same innovative gender change from masculine to feminine in Ibero-Romance varieties. Although it is not possible now to explore the motivations for this feminization of mass and abstract nouns, future research should focus on the individualizing properties of feminine gender, as well as on its discursive and referential functions, in order to come to grips with this particular drift of Spanish language.

To sum up, ’small forces‘ motivating gender changes in rural Spanish dialects oscillate between the maintenance of conservative local traditions and innovative uses of the feminine gender. Contemporary rural dialects of European Spanish depict a partial and fragmented picture, as the phenomena of ’grammatical gender changes‘ are regressive and strongly dedialectized (Auer 2011; Heap and Pato 2012) due to stigmatization and negative connotations. The scarcity of these phenomena in urban sociolects corroborates this. However, data presented in this article have shown the final stages of vernacular drifts and the persistence of, more or less wide, dialectal areas in 21st century European Spanish. Therefore, my analysis has shed light on ancient dialects and their spreading focal points and also have brought to light innovative drifts in Spanish. Of course, a diachronic study is urgently needed to systematize the evolution of gender changes in relation to the variational and geographic space.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | To illustrate this point, I choose the following quote taken from the Estudio sobre el habla de la Ribera: ‘El género en las palabras riberanas, como pasa en todos los dialectos y en el habla vulgar de Castilla, difiere con mucha frecuencia del de el <sic> castellano correcto‘ (Llorente Maldonado de Guevara 1947, p. 121) (Grammatical gender of Riberan words, as it is usual throughout all dialects, as well as in vulgar speech of Castille, differs from that assigned in correct Castilian). Similar statements are found in other monographs and quotes could be multiplied. For an insightful and necessary reflection on the need to distinguish between ’dialectalism‘ and ’vulgarism‘, I recommend de Benito Moreno (2020). |

| 2 | See, for example, Álvarez (1949), Neira Martínez (1955), Fernández (1960), Álvarez Fernández-Cañedo (1963), Cano González (1978), Fernández González (1981), González Ferrero (1986) and Borrego Nieto (1996) for the Bables or for the most dialectalized areas of the Leonese domain. As a characteristic feature of general Asturian, it is included by Martínez Álvarez (1996) and the GLLA (2001, s.v.). According to Zamora Vicente (1960), this trend reached western Andalusia. |

| 3 | This is remarked by, among others, Badía Margarit (1950), Haensch (1960) and Laguna Campos (2009). |

| 4 | See García de Diego ([1918] 1990), Lázaro Carreter (1945), Alvar (1948, 1956–1957), Badía Margarit (1950), García Cotorruelo (1959), Zamora Vicente (1960), Ena Bordonada (1976), Calero López de Ayala (1981), Alvar (1996) and Domene Verdé (2010), among others. The extension of la calor (the.f heat.m) throughout ’popular speech of Spain‘ (Alvar 1948, p. 86) or its presence, even, in Asturias (Rodríguez Castellano 1952) or Cantabria (Penny 1969) suggest a greater extension of the limits of -or nouns in the feminine in earlier stages. |

| 5 | See, for example, Bello ([1847] 1988), Alcina Franch and Blecua (1975), Fernández Ramírez (1986), Alarcos Llorach (1994) and Gómez Torrego (2004). Nebrija ([1492] 2011) described them as ’de género dudoso‘ ‘of dubious gender’, while the RAE (1931) refers to this type of nouns as ‘de género ambiguo‘ ‘of ambiguous gender’. As an equivalent of ambiguo (‘ambiguous’), I may sometimes use the term ambigeneric. This term is generally reserved for Romanian nouns that, like scaun (‘chair’), show two different genders in the singular (masculine) and plural (feminine) (Corbett 1991). Keep in mind that beyond the sociodialectal factors on which I will focus in this paper, the number influences the preference for one gender or the other in Spanish nouns, such as arte (el arte the-m.sg art vs. las artes the-f.pl arts) o azúcar (azúcar blanquilla sugar white-f.sg vs. azúcares refinados sugar-pl refined-m). The fixation of gender in the plural might be explained by the structuring of the higher functional layers of the DP since the introduction of the NumP requires the clarification of gender (for further details, see Picallo 2008; Kramer 2015; and Acquaviva 2019, 2020). |

| 6 | This type of noun is called ’comunes en cuanto al género‘ ‘common regarding gender’ since without presenting a specific form, they alternate between the masculine (el estudiante the m student) and the feminine (la estudiante the-f student) depending on the biological sex of the referent. |

| 7 | Nouns such as frente or cometa could be analyzed as ’significantes homófonos‘ ‘homophone signs’ (Alarcos Llorach 1994, p. 62), different items (Ambadiang 1999, p. 4857) or (quasi-)homomines (Roca 2006). From a historical point of view, Pountain (2005, 2015) has used the concepts of capitalization and refunctionalization to account for how generic variation is exploited to ratify semantic differences. |

| 8 | An exception stands for Rini (2014, 2016) on azúcar ‘sugar’ and recently Montero Curiel (2019) on sartén ‘frying pan’ in Spanish-speaking countries. |

| 9 | Current research on the gender system in Spanish claims that this language consists of a single grammatical gender: the feminine (Roca 2005; Mendívil Giró 2020; Fábregas 2022a). Faced with the defense of a single gender (feminine) or a binary system (masculine/feminine), a third option would fit to account for the grammatical gender that corresponds to ambigeneric nouns: alternating gender ([α]). This gender characterizes that of pronouns (Te[α] veo muy {contento [m]~contenta [f]} ‘I see you very happy’ (Bosque 2015) and could be applied to nouns, such as calor ‘heat’ ({el[m]~la [f]} calor[α]). Despite the attractivity of this hypothesis, which could—perhaps—account for ’common gender‘ nouns such as estudiante ‘student’ ({el[m]~la [f]} estudiante[α]), it should be noted that ambiguous nouns have a fixed gender in the dialectal grammar of a speech community, so for those speakers who use the noun dote ‘dowry’ as masculine, the gender of this noun is invariably masculine (‘se juntaba el dotecito‘ (they gathered ‘the.m dowry.dim-m’)). I am aware that my assumption may be simplistic, since as the pioneering work by Harris (1991) concludes, it is necessary to separate semantics (biological sex), grammar (grammatical gender) and noun classes, but at the same time I consider it essentially correct and, in any case, valid for purposes of present argumentation. |

| 10 | The use of these labels in traditional grammar reflects the interference between grammatical gender and biological sex. On the contrary, I could accept a more neutral vision according to which Spanish nouns are distributed between class I and class II, sometimes motivated by semantic factors such as, in the case of animated nouns, biological sex of their referents. For the extension of binary systems in the languages of the world, see Corbett (2013). Against binary marking systems such as [+m]/[-m] (Marcantonio and Pretto 1988) or[+f]/[-f] (among others, Moreno Cabrera 1991), I prefer the explicitation of the values ([m]/[f]) of gender feature. The separation of grammatical properties of nouns and their referential capacities means that the existence of epicenes or heteronyms is not supported since these nouns would be either masculine (gorila ‘gorilla’, bebé ‘baby’, tigre ‘tiger’, hombre ‘man’, toro ‘bull’) or feminine (ballena ‘whale’, víctima ‘victim’, liebre ‘hare’, perdiz ‘partridge’, mujer ‘woman’, vaca ‘cow’), regardless of real world and in a more or less pragmatically motivated way. In spite of the characterization of masculine gender as a non-marked or inclusive gender in Spanish (cf. Mendívil Giró 2020), there is no doubt that there is a type of masculine noun in Spanish, such as marido ‘husband’ (los {*maridos~esposos}, sea cual sea su sexo, deben faenar sinceramente ‘the {*husbands~spouses}, whatever their sex, they must slaughter sincerely’), whose behavior is opposed to that of inclusive masculine as ciudadanos ‘citizens’ and is similar to that of exclusive feminine (({los ciudadanos~*las ciudadanas}, sea cual sea su sexo, deben votar con responsabilidad ‘the {citizens.m-pl~*citizens.f-pl}, whatever their sex, must vote responsibly). For these and other tests, I refer to Roca (2005, 2006, 2009). The present paper will not tackle the so-called ’masculino despectivo‘ (‘derogatory masculine’) (the issue is thoroughly addressed in Bajo Pérez 2021), which would nevertheless support the pervasiveness of gender inflection in Spanish. The proposal for an ’inclusive gender‘ (les amigues) has caused the Spanish masculine gender to restrict its reference exclusively to beings of males (Gil 2020; Fábregas 2022b). The architecture of gender in Spanish, whose formulation I cannot develop now, requires considering at least three levels: default gender (infinitives or conflict cases, for example; cf. Corbett and Fraser 1999), inclusive gender (nouns such as ciudadanos (citizens.m-pl)) and basic gender (libro ‘book’ [m] vs. mesa ‘table’ [f]). The so-called ’neutro de materia‘ of some dialect systems of northern Spanish (see Fernández-Ordóñez 2009b; Loporcaro 2017, pp. 145–72) could be considered a subgender in the Spanish gender system. |

| 11 | Despite the ’marcada tendencia a asociar algunas marcas con los dos rasgos de género‘ ‘marked tendency to associate some marks with the two gender features’ (Ambadiang 1999, p. 4875) and the ’remarkable consistency‘ (Nissen 2002) between the ending (-o, -a) and gender (masculine, feminine) (see also, among many others, Rosenblat 1962, Teschner and Russel 1984, Moreno Fernández and Ueda 1986, and Eddington 2002 and their pertinent statistical analyses), there is a long and controversial debate about the grammatical or lexical status of the endings -o and -a and their relationship to gender in Spanish (see Ambadiang 1994, 1999). Gender motion is seen either a inflection or derivation (see, among many others, Moreno Fernández and Ueda 1986; Millán Chivite 1994; Murillo 1999; Lliteras 2008; Serrano Dolader 2010; Stehlík 2018). Recently, Mendívil Giró (2020) has argued that the words like niño ‘boy’ and niña ‘girl’ are differentiated lexemes, like vaso ‘glass’ and mesa ‘table’ (see also Escandell-Vidal 2018 and Gutiérrez Ordóñez 2019). Undoubtedly, the solution to the controversy involves distinguishing—at least—two fundamental functions of grammatical gender: the classifying function and the referential function (for the positions that gender occupies in the DP structure, see, among others, Fábregas and Pérez 2010, and Acquaviva 2020). |

| 12 | The interaction of the diminutive and grammatical gender is developed in Fábregas (2013, 2022a). This externalization of inherent lexical gender does not succeed in the case of masculine nouns ending in -a in both inanimate (problem-it-a, *problemito) and animate (goril-it-a, *gorilito) nouns. The field of suffixation provides additional arguments supporting a binary system of grammatical gender in Spanish since there are inherently gendered suffixes that change the gender of the nominal base to which they are attached: zapato [m] > zapat-ería [f], raqueta [f] > raquet-azo [m] (see, among others, Santiago Lacuesta and Gisbert 1999). |

| 13 | The rules for assigning grammatical gender to ambiguous nouns have raised special interest amongst Hispanists (for example, Cuervo 1939, Rosenblat 1952, Echaide 1969 and Eddington 2002). For the assignment of grammatical gender, research by Corbett (1991, 2007, 2013); (Corbett and Fraser 2000) is essential; see also Thornton (2009) and references therein. |

| 14 | In the examples, transcription signs are simplified. In the COSER examples, besides the interview code, the survey point and province are provided, while in the PRESEEA examples, the city is indicated. In both cases, sex, age (and socio-educational level, in the case of urban samples), as well as the date of the interview, are reported. Glosses refer to the relevant words and follow the academic fixed or preferred gender (e.g., according to DLE, labor ‘housework’ is glossed as a feminine noun, while calor ‘heat’ is glossed a masculine noun, despite them showing different genders in vernacular dialects). Maps show the survey points from the rural corpus. The main focus of the present article is non-standard gender assignment. Standard gendered nouns seem not to be informative, and this is the reason why relative frequencies are avoided in the paper, as a reviewer has suggested. The normative el aceite (the.M oil.m) appears up to 356 times in—practically—all Spanish provinces, whereas la aceite (the.f oil.m) occurs only 21 times. Both the masculine and feminine gender are conflicting in Albacete (respectively: 7/1), Alicante (20/8), Asturias (3/3), Badajoz (14/1), Cantabria (11/1), Ciudad Real (5/1), León (1/4), Murcia (18/1) and Salamanca (3/1). Northwestern varieties (Asturias, León) clearly prefer la aceite, and this anti-normative feminine agrees in a relevant way with other non-standard gendered feminine nouns, such as azúcar (‘sugar’), maíz (‘corn’) and vinagre (‘vinegar’). |

| 15 | Agreement mismatches in the nominal domain are recurrent in the so-called ’transitional bilinguals‘ (Lipski 1993). These disagreements might grouped with other types of linguistic “errors” due to interference, such as those that Enrique-Arias (2020) found in the verbal morphology of Catalan speakers when speaking in Spanish. |

| 16 | Constructions such as el arradio (the.m pref.radio.f) or el afoto (the.m pref.photo.f) are described as a vulgar phenomenon by García Cotorruelo (1959), Cummins (1974) and Montero Curiel (1997). I find them in Aragon, Catalonia, La Mancha, Murcia, Andalusia and the islands of Gran Canaria and Lanzarote. As for sequences such as el radio (the.m radio.f), los manos (the.m-pl hands.f-pl) and las mediodías (the.f-pl noon.m-pl), these are recorded in Álava, Palencia, Seville, Granada, Málaga and Murcia. The dispersion of these points and the absence of similar sequences in urban sociolects support their analysis as ’general vulgarisms‘. I may conclude, in a somewhat simplified way, that the vernacular los manos and las (medio)días amend an anomaly in the nominal morphology of Spanish. |

| 17 | Gender changes caused by the allomorph (el) of the feminine article (la) have been studied in Rosenblat (1949), Álvarez de Miranda (1993), Eddington and Hualde (2008), and Rini (2016). The use of masculine determiners before nouns such as agua ‘water’ is documented in urban Spanish, even in speakers with a medium–high educational level. For academic recommendations on the article, see the DPD (2005, el). The sequence la agua (the.f water.f) instead of canonical el agua raises interest and occurs throughout Galicia, León, Zaragoza, Teruel, Valencia, Alicante, Málaga and the Canary Islands. The la agua combination reinforces the feminine character of these nouns (Álvarez de Miranda 1993). |

| 18 | In group B, one of the ambiguous nouns par excellence should be included, such as mar ‘sea’ (Lundeberg 1933). I will devote a monographic study to mar from a diachronic and variational point of view. |

| 19 | Alvar (1959) observed these masculine-gendered terms in Tenerife. |

| 20 | The term cimece, masculine-gendered in Latin, became feminine in the vernacular. Although the standard admits both genders, the educated prefer the use of the feminine gender (DPD 2005, s.v.). There are many cases of hypercharacterized gender, such as chinch-a (bedbug.f) in western and eastern northern vernaculars (Rodríguez Castellano 1952; Borrego Nieto 1996; Laguna Campos 2009). The hypercharacterized female gender has gained prestige in the related word pulga ‘flea’ (lat. pulice). |

| 21 | For the history of simiente ‘seed’ as a vernacular voice in Romance, stemming from semente and related to the neuter semine), and its replacement by semilla ‘seed’, a lexical innovation that does not reach Aragon, it is highly recommended to read DECH (1974, s.v.). |

| 22 | Labor ‘housework’ illustrates one of the few nouns ending in -or whose normative gender corresponds to the feminine. The etymological masculine is preserved in Portuguese (lavor), Galician (labor) and Asturian (llabor). The interference with Galician undoubtedly explains the examples in (4a-b), although the examples from Murcia (a region where anti-normative feminine nouns ending in -or exist in large numbers, García Cotorruelo 1959) indicate that the phenomenon had a greater scope. In all the examples, labor [m] refers to housekeeping and housework. Perhaps, it would be possible to advance a hypothesis regarding a semantic specialization of each gender: el labor (the.m labor) would be used for housework, while la labor (the.f labor) would be dedicated to farming activities. |

| 23 | This noun, feminine in the standard, appears in Cáceres in the following phrase: unos lombrices chiquininas (some.m-pl worm.f-pl small.f-pl). |

| 24 | The change from feminine to masculine has been explained by false reanalysis caused by the article: la sartén > l’asartén > el asartén > el sartén (the same explanation is offered for yunque ‘anvil’, cf. DECH 1974, s.v.), but also by possible lexical relationships with the names of other containers that, while reinforcing the feminine (paella, olla ‘pot’ and caldera ‘bucket’), could promote gender change (puchero ‘stewpot’, cazo ‘saucepan’ and caldero ‘bucket’) (Rosenblat 1952). |

| 25 | The phrase una balde appears in a context potentially influencing gender change: ’ya coges una lata, una balde, chisma como miel, una jarra […] con miel‘ ‘and you take a can, a bucket, full with honey, a jar […] with honey’ (COSER 3426, Palencia, Valle de Cerrato, male, age 81, 27 March 1994), where balde ‘bucket’ appears together with other feminine-gendered names of container (lata ‘can’ and jarra ‘pitcher’). In any case, contrary to these nouns whose final -a matches feminine gender, nouns ending with -e noticeably challenge gender assignment mechanisms. |

| 26 | ’El tractor, como va con la remolque, detrás va cayendo la uva‘ ‘The tractor, as it goes with the trailer, the grapes fall behind’ (COSER 3106, Murcia, Lorca, male, age 79, 9 October 2013). |

| 27 | Yunque ‘anvil’ goes through a complicated history (DECH 1974, s.v.). From the feminine lat. incude, this lexeme maintained its etymological gender until the 16th–17th centuries, when the masculine—the only gender to be permitted by the then current academic norm (DPD 2005, s.v.)—became general. The change towards the masculine could be motivated, as in the case of sartén ‘frying pan’ already mentioned, by a false reanalysis: la yunque > l’ayunque > el (a)yunque. The Arabism almirez ‘mortar’ is the only one of this group ending in -z, and its feminine is located only once in Cuenca. |

| 28 | This noun also presents a complex history since its lexical genesis is not even clear (the postverbal formation of pringar ‘smear’ or a relationship with the adjective pingüe ‘fat’) (Rosenblat 1952) and, in any case, it seems linked to that of the noun mugre ‘dirt’, from which it would take an epenthetical -r- (pingue > pingue > pringue) and the feminine gender. |

| 29 | ’Se pisaba bien la uva, salía y a la carral‘ ‘The grapes were well trodden, [the wine] came out and was poured into the barrel’ (COSER 2606, León, Gradefes, female, age 75, 8 July 1991). |

| 30 | The female use of animal ‘animal’ is observed in the following example: ’hasta veinte [crías] han pe-, han parío también, de, de una hembra, y, y luego, pillabas, te dejabas pa ti..., pa otro año. Y esa animal mismo, esa, la, la engordabas cuando terminaba de, de criar, la engordaban, y luego para matala“ ‘A female have given birth up to twenty offsprings and then you keep it for yourself, for the next year, you fattened that very animal when it finished breeding, you fattened it for slaughter’ (COSER 4108, Teruel, Bronchales, male, age 87, 5 May 2001). In this sample, the epicene noun animal ([m]) becomes a common noun for reasons of referentiality (la animal (the.f animal) ‘the female animal’). |

| 31 | The occurrence of this noun with the feminine gender is sporadic and reinforced by the anaphoric use of masculine pronoun (los them.m-pl), for example, ’las costillares pa salalos‘ ‘the ribs to salt them’ (COSER 2303, Jaén, Cabra del Santo Cristo, male, age 74, 11 May 2002). |

| 32 | I could add sequences like mucha fuego (much.f fire.m) ‘a lot of fire’ (Huesca), tanta animal (so.f animal.m) ‘so many animals’, mucha maíz (much.f corn.m) ‘a lot of corn’ (Navarra), mucha algarrobo (much.f carob.m) ‘a lot of carob’ (Zamora) o mucha mérito (much.f merit.m) ‘a lot of merit’ (Menorca) to those found and described by Fernández-Ordóñez. I have not counted cases like these in my data. |

| 33 | This term appears in the speech of an 88-year-old female informant from Soria who corrects herself: ’le ponían una ordeñador, ordeñadora a las vacas‘ ‘they put the milker to the cows’ (COSER 3901). For the interplay between gender and agentive/instrumental nouns, see, among others, Pountain (2006). |

| 34 | Labor ‘housework’ recalls this ancient drift and remains feminine in the standard despite retaining the etymological and original masculine gender in northern vernaculars (4a-b). It remains to be determined if the reaction starts, as can be hypothesized, from the written and educated level, even affecting daily words like sudor ‘sweat’ (10c) or if, on the contrary, it spreads from below. |

| 35 | Calor ‘heat’ appears in the feminine 48 times in rural dialects, especially in western and eastern Andalusia (thirteen times), Aragón (seven), La Mancha (six), Murcia (four) and the Canary Islands (three), as well as in Catalan-speaking territories such as Tarragona, Valencia, Alicante and Menorca (three). There is no lack, however, of la calor (the.f heat.m) in northern areas of Asturias (two), Zamora and Segovia. In urban sociolects, the feminine use of calor appears 25 times and finds acceptance only (except for one occurrence in Santiago de Compostela) in the Andalusian capitals, where it is used by all types of informants. The rest of the nouns ending in -or are not as widespread and do not reach 15 occurrences; these non-canonical gendered nouns are limited, from north to south, to eastern territories: Huesca (two times), Zaragoza, Teruel (three), Soria, Cuenca, Tarragona, Castellón, Alicante, Murcia (two) and Almería. |

| 36 | The feminine of melocotón ‘peach’ appears in a metalinguistic comment made by a female informant about her parents’ generation’s way of speaking: ’mi suegro mismo pa decí melocotón dicía melo, la melo-, la melocotón‘ ‘My father-in-law himself used to say peach, he said the peach’ (COSER 0214, Albacete, Liétor, female, age 72, 25 April 2009). This demonstrates the clear decline of non-canonical feminine-gendered nouns in 21st century Spanish. |

References

- Acquaviva, Paolo. 2019. Categorization as noun construction. In Gender and Noun Classification. Edited by É. Mathieu, M. Dali and G. Zareikar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 44–63. [Google Scholar]

- Acquaviva, Paolo. 2020. Gender as a property of words and as a property of structures. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 19: 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcos Llorach, Emilio. 1994. Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa. [Google Scholar]

- Alcina Franch, Juan, and José M. Blecua. 1975. Gramática Española. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso Garrote, Santiago. 1947. El dialecto Vulgar Leones Hablado en Maragatería y Tierra de Astorga: Notas Gramaticales y Vocabulario. Madrid: Espejo. [Google Scholar]

- Alvar, Manuel. 1948. El habla del Campo de Jaca. Salamanca: Centro Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Alvar, Manuel. 1956–1957. Notas lingüísticas sobre Salvatierra y Sigüés Valle del Esca, Zaragoza. Archivo de Filología Aragonesa 8–9: 9–61. [Google Scholar]

- Alvar, Manuel. 1959. El Español Hablado en Tenerife. Madrid: Centro Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Alvar, Manuel. 1996. Andaluz. In Manual de Dialectología Hispánica. El Español de España. Edited by Manuel Alvar. Barcelona: Ariel, pp. 233–58. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, Guzmán. 1949. El habla de Babia y Laciana. Madrid: Centro Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez de Miranda, Pedro. 1993. El alomorfo de “la” y sus consecuencias. Lingüística Española Actual 15: 5–43. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Fernández-Cañedo, Jesús. 1963. El habla y la Cultura Popular de Cabrales. Madrid: Centro Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Ambadiang, Théophile. 1994. La Morfología Flexiva. Madrid: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Ambadiang, Théophile. 1999. La flexión nominal. Género y número. In Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española. Edited by en Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa, vol. 3, pp. 4843–913. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, Peter. 2011. Dialect vs. standard: A typology of scenarios in Europe. In The Languages and Linguistics of Europe. A Comprehensive Guide. Edited by Bernd Kortmann and Johan van der Auwera. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- Badía Margarit, Antonio. 1950. El habla del Valle de Bielsa Pirineo Aragonés. Barcelona: Centro Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Bajo Pérez, Elena. 2021. El masculino despectivo o desmerecedor. Moenia 27: 1–51. [Google Scholar]