Abstract

Clitic doubling (CD) is the co-appearance in the same sentence of the clitic and a correlative syntagma in the canonical position of the object. Apart from obligatory contexts, CD of the indirect object (IO) is found with variable frequency in Romance languages and even in different varieties of the same language, most likely because it is a phenomenon of internal/external language interface. The objective of this work is to determine the frequency of CD in non-obligatory contexts of recipient and location IO in peninsular Spanish, and to analyse its features according to the referential hierarchy used for the diachronic evolution of the phenomenon. For this purpose, we extracted data from two open access corpora of interviews (COREC and PRESEEA) from different regions that are (or are not) areas of historical contact with other languages. The results show a significant extension of doubling in contexts where this is optional and the neutralisation of features that previously predicted CD of IOs. Nevertheless, there are geographical differences in peninsular Spanish in terms of frequency, definiteness, specificity, the influence of the cliticization of the direct object, and the accessibility of the IO referents in the minds of the speakers.

1. Introduction

This paper analyses the frequency and characterisation of clitic doubling (CD) of the indirect object (IO) in the spoken corpus of peninsular Spanish.1 CD is the co-appearance in the same sentence of the clitic and a correlative syntagma in the canonical position of the object (Fernández Soriano 2015, p. 429). We use data taken from the Corpus del Español en Contacto (COREC) and the Proyecto para el estudio sociolingüístico del español de España y de América (PRESEEA), two open access corpora of interviews. CD of strong (stressed) pronominal IOs is obligatory in Spanish (1a), Catalan Asturian, Galician, and Romanian. In Portuguese, CD is optional in these contexts, while in Italian and French (but not in colloquial French), it is not considered grammatically correct (Dubert and Galves 2016, pp. 434–35; Tuten et al. 2016, p. 405; Sitaridou 2017, pp. 122–24). With a nominal IO, CD is widespread, and even obligatory, according to many scholars, in Spanish (1b), Catalan, Asturian, and Galician; optional in Romanian; but not possible in Standard French, Italian, or Portuguese.

While the doubling of the nominal or strong pronominal IO postponed to the verb is practically generalised in all Spanish dialects, it is less common and more restricted when the object is a direct object (RAE-ASALE 2009). However, in colloquial speech, CD of direct objects may be a common phenomenon depending on the geographical region and the semantic and pragmatic features of the object (Gómez Seibane 2021a, 2021b). In Spanish, CD is favoured by a set of hierarchical features, such as personal pronouns, definiteness, or specificity, among others (Leonetti 2007; Fischer and Rinke 2013; Rinke et al. 2019), although its influence shows signs of neutralisation for the IO.

| (1) | a. | *(Le) | di | un | regalo | a | él. |

| CL.dat | gave.1sg | a | git | to | him | ||

| I gave him a gift. | |||||||

| b. | (Le) | di | un | regalo | a | Juan. | |

| CL.dat | gave.1sg | a | git | to | Juan | ||

| I gave a gift to Juan. | |||||||

Furthermore, clitic-doubled objects should be distinguished from so-called ‘dislocation,’ in which a complement has been displaced to an extra-orational position, a construction that implies a prosodic break and also has a varied informative function, such as topic-, background-, or contrast-marking devices (Fernández Soriano 2015, pp. 429–30; Sitaridou 2017, pp. 119–20). The examples in (2) illustrate the left (2a) and right (2b) dislocations, and the hanging topic (2c), which may be resumed by a strong pronoun. According to Fernández Soriano (2015, p. 429), in (2), there is no CD in a strict sense.

| (2) | a. | Ese | libro | ya | lo | leí. | |

| this | book | already | CL.acc | read.1sg | |||

| That book, I already read it. | |||||||

| b. | No | lo | conozco, | a | ese | individuo. | |

| no | CL.acc | know.1sg | to | that | individual | ||

| I do not know him, that individual. | |||||||

| c. | Eso, | dice | que | no | quiere | ni | |

| that | say.3sg | that | not | wants.3sg | not-even | ||

| pensar | en | ello. | |||||

| think | about | it | |||||

| That, he says he does not even want to think about it. | |||||||

In all Spanish varieties, CD is obligatory with dative nominal objects, and mainly in certain two-argument constructions with verbs of experience, feeling, or interest (3a). Datives with other thematic roles, such as recipient (3b), possessor (3c), and goal or location (3d), are also doubled (Givón 2001; RAE-ASALE 2009, pp. 2677–83).

| (3) | a. | El | deporte | le | encanta | a | Pedro. | |||

| The | sport | CL.dat | love.3sg | to | Pedro | |||||

| Pedro loves sports. | ||||||||||

| b. | (Le) | di | un | libro | a | su | hijo. | |||

| CL.dat | gave.1sg | a | book | to | his | son | ||||

| She/he gave his son a book. | ||||||||||

| c. | (Le) | vi | la | cima | al | Everest. | ||||

| CL.dat | saw.1sg | the | top | to-the | Everest | |||||

| I saw the top of the Everest. | ||||||||||

| d. | (Le) | acerqué | la | silla | a | María. | ||||

| CL.dat | approached.sg | the | chair | to | Mary | |||||

| I brought the chair closer to Mary. | ||||||||||

In this paper, CD refers only to the occurrence of a clitic and a full noun phrase (NP) in canonical object position, as shown in (1). In (4), both the dative clitic (les) and the object (a sus clientes) are in one and the same prosodic and syntactic domain, while the dative nominal object is understood as a new information focus or as part of the focus domain (Rinke et al. 2019). Thus, here, we leave aside the doubling of strong pronouns, as in (1a), which is mandatory.

| (4) | a. | Les | entregaron | los | pedidos | a | sus | clientes. |

| CL.dat | delivered.3sg | the | orders | to | their | clients | ||

| They delivered the orders to their clients. | ||||||||

The objective of this work is twofold: first, we aim to determine the frequency of CD of IOs in non-obligatory contexts of recipient (4b) and location (4d) in a spoken corpus of peninsular Spanish. Secondly, we identify the semantic contexts in which CD takes place, and to what point the referential hierarchy explaining the diachronic development is maintained. The results of our study show that doubling is the most widespread option in optional contexts, revealing that the predictive value of the referential hierarchy in the evolution of the phenomenon is practically neutralised in favour of the extension of CD with IOs. Nevertheless, we discovered that there are geographical differences in peninsular Spanish in terms of frequency and characterisation of the phenomenon.

This work is structured as follows: Section 2 offers an overview of the current state of research into CD with IOs, with a focus on the origin and diachronic extension of the phenomenon, the influence of certain factors, and the current data on its frequency. Additionally, Section 2.1 presents a cross-linguistic perspective of the phenomenon, given that peninsular Spanish is in contact with other Romance languages as well as a typologically isolated language (Basque). This section concludes in Section 2.2, with a series of research questions and hypotheses. Section 3 discusses issues related to the treatment and analysis of the spoken data from both a quantitative and qualitative perspective. Section 4 presents the results of our quantitative analysis of rate and characterisation of doubling. This is followed by an analysis of the general trends revealed by the data in order to offer as precise a determination as possible of the frequency and the grammatical context of CD with IOs. Finally, Section 6 returns to our research questions and offers our conclusions.

2. Doubling of IOs in Spanish

CD is based on topic-shift construction (Givón 1976), a structure with a dislocated theme that is anaphorically resumed by a pronoun. CD is the result of the syntactic reanalysis of the dislocation to the right, as well as the extension of the preposition a of the indirect object to the direct object in the case of the direct object CD (Gabriel and Rinke 2010; David 2014).2 Although the indirect and direct objects are most commonly doubled with a, prepositional marking is not a necessary condition for CD in the different varieties of Spanish or in other Romance languages (Sitaridou 2017, pp. 120–21). However, one of the consequences of object marking has been the formal approximation of indirect and direct objects, which, for some authors, reinforces the categorial status of the IO by doubling (that is, by means of a double marking) (Company 2012; Melis and Flores 2007).3 Contrary to the hypothesis of CD as a phenomenon of topicalization, García Salido and Vázquez Rozas (2012) propose that the grammaticalisation of the personal morpheme le/s as part of the verbal morphology is due to the frequent association between specific predicates and certain codifications of the object (García Salido and Vázquez Rozas 2012, p. 68).

In the past, CD of IOs was a sporadic and marginal phenomenon, and it slowly advanced and spread throughout the Spanish peninsula during medieval times. From the 15th century onwards, there was significant growth (Gabriel and Rinke 2010), and from the 16th century, strong pronouns and experiencer IO were doubled systematically (from 79% to 100%). Nominal indirect objects began to be doubled from the 17th and 18th centuries, but much less frequently (18–21%). According to studies of Argentinian Spanish, in the 18th century, nominal IO doubling represented 24%, in the 19th century, it represented 25%, and it represented 45% in the 20th century (Pericchi et al. 2020).

Doubling depends on a complex interplay of diverse factors that are relevant to varying degrees and for which the influences are not entirely understood. Some of the influential factors are the nature and semantics of the referent in combination with definiteness, specificity, personal pronouns, and case. Doubling thus responds to an implicational scale (5) that largely confirms the diachronic extension of the CD (Leonetti 2007; Fischer and Rinke 2013, p. 467). In agreement with these, the elements at the extreme left of the scale are more susceptible to doubling than those at the extreme right (Rinke et al. 2019, p. 39).

| (5) | Implicational scale of CD: strong personal pronouns < datives < definite descriptions < specific indefinites < non-specific indefinites |

This process of expansion is based on the properties of the object, in which animation interacts with other parameters, such as definiteness or specificity (Comrie 1989, pp. 185–88). As noted above (Section 1), thematic roles also influence the doubling of the IO: it is obligatory with experiencers and benefactive and inalienable possession and optional with recipients (Fernández Soriano 1999, p. 150). For some authors, CD and topicality4 are closely related (Gabriel and Rinke 2010). In fact, CD is obligatory with strong pronouns, regardless of their case, as these are paradigmatic topics. With a nominal/clausal object, CD is much more probable with an IO, as these are more topical than direct objects.

Currently, in colloquial speech, the doubling of the nominal IO is virtually categorical in the Rioplatense variety of Spanish (91%), and it is heavily predominant in peninsular Spanish, specifically in Madrid (81%) (Rinke et al. 2019). The IO tends to be definite, specific, and animated, although CD is also found with inanimate and non-specific referents. The thematic role of benefactive, specificity, and positive polarity are factors that favour doubling in Spanish.

In written language, however, the frequency of doubling is highly dissimilar. Flores and Melis (2004) found rates of doubling of 91% for the Mexican variety of Spanish, 51% for the Asturian–Leonese and Basque regions, and 65% for the Madrid variety. In contrast, Dickinson et al. (2021) noted that doubling of the IO did not exceed 35% in a written corpus. The authors also identified differences in the frequency of doubling according to the type of verb and verb constructions. For example, there was considerable variation in the rate of doubling with some verbs, such as enviar (‘to send’) at 11% vs. mandar (‘to send’) at 35% or comunicar (‘to communicate’) at 8% vs. decir (‘to say’) at 33%, despite their semantic connection. Similarly, different frequencies of CD were found for dar lugar (‘to give rise’)/origen (‘to give rise’)/paso (‘to make way’) compared to dar (‘to give’) followed by an NP.5 Nevertheless, the differences in frequency found by Flores and Melis (2004) and Dickinson et al. (2021) may be due to their methodology of data collection. The former included contexts of mandatory doubling, such as strong pronouns and dislocated IO.

Data from judgements of acceptability show that doubling is a quite widespread choice (63%) in contexts where doubling is optional (Galindo 2020). In line with Rinke et al. (2019), in these optional contexts, the rate of doubling rises by hierarchies of definiteness and animation. The cliticization of the direct object appears as a favouring factor in doubling (95%), while the thematic role of goal shows lower indices of doubling. Cfr. Rinke et al. (2019).

Occasionally, the alternation between doubling vs. non-doubling implies some semantic difference. Specifically, with doubling, the situation described in (6a) affects the recipient to a greater degree or implies some change in their state; furthermore, it provides a sense of totality or completeness to the event described. Thus, in (6a), the presence of the dative clitic suggests that Latin American immigrants did in fact learn to speak English, while the variant without clitic (6b) merely describes the activity of teaching, without indicating whether they actually learned English or not.

| (6) | a. | De | estudiante | les | enseñó | inglés | a | (RAE-ASALE 2009, p. 2680) |

| as | student | CL.dat | taught.3sg | English | to | |||

| los | inmigrantes | latinos. | ||||||

| the | immigrants | Latino | ||||||

| As a student, he taught Latino immigrants English. | ||||||||

| b. | De | estudiante | enseñó | inglés | a | los | ||

| as | student | taught.3sg | English | to | the | |||

| immigrantes | latinos. | |||||||

| immigrants | Latino | |||||||

| As a student, he taught English to Latino immigrants. | ||||||||

Dative clitic doubling in Spanish has given rise to a theoretical discussion of the categorical status of the doubled form, the type of ditransitive construction, and its relation with differential object marking. In fact, it has been debated whether the recipient of (7a) is a prepositional phrase (PP), while the doubled dative construction (7b) is a determinant phrase (DP). In parallel, (7) has been associated with dative alternation in English, consisting of a prepositional construction where the goal argument is a PP (8a), and a double object construction in which the dative argument is a DP (8b) (Acedo-Matellán et al. 2022, pp. 507–10).

| (7) | a. | Dimos | el | libro | al | presidente. | (Acedo-Matellán et al. 2022, p. 508) |

| gave.1pl | the | book | to-the | president | |||

| We gave the book to the president. | |||||||

| b. | Le | dimos | el | libro | al | presidente | |

| CL.dat | gave.1pl | the | book | to-the | president | ||

| We gave the book to the president. | |||||||

| (8) | a. | The teacher gave a book to her student. |

| b. | The teacher gave her student a book. |

There is a widely known discussion about whether datives and differential object marking constitute a homogeneous class. In this sense, it has been noted that the marker of the direct object (a la niña) in (9a) is a homophone to the dative (a la estudiante) of (9b).

| (9) | a. | He | visto | a | la | niña. | ||

| have.1sg | seen | to | the | girl | ||||

| I have seen the girl. | ||||||||

| b. | Le | regalé | un | libro | a | la | estudiante. | |

| CL.dat | offered.1sg | a | book | to | the | student | ||

| I offered a book to the student. | ||||||||

An important issue is whether this syncretism reveals a common syntactic source of the dative and differential object marking, or if it is simply a question of superficial opacity. It has recently been suggested that what is considered ‘dative’ in typologically related languages, such as Romance languages, in fact includes different types of entities (Cabré and Fábregas 2020).

2.1. Doubling of IOs in Spanish in Contact with Other Languages

For the present work, we selected ditransitive constructions for which the IOs designate a recipient of an action or process, as in (Le) entregaron el paquete a mi vecino (‘They delivered the package to my neighbour’), and those with an express location, as in (Le) puso sal a la ensalada (‘He added salt to the salad’) (RAE-ASALE 2009, pp. 2686–84). For structural reasons, these two types of IO can be considered together, as they are argumental and ditransitive, and for their semantic relation. Additionally, in these constructions, Spanish grammar allows the possibility of doubling in the IO. In principle, in using data from oral speech, we expect to see a tendency for doubling in the IO.

The phenomenon of CD is highly variable in Romance languages. In fact, we find differences between languages and within different varieties of the same language. This variation can be explained, in part, as a result of grammatical (e.g., the category, pronominal or nominal), semantic (e.g., animation), and pragmatic (e.g., specificity) factors. Doubling is a phenomenon of the internal (syntax–semantics) and external (syntax–pragmatic/discourse) interface and is thus sensitive to linguistic variation in language acquisition and language contact (Muysken and Muntendam 2016).

In much of the peninsula, Spanish is in contact with other Romance languages and with a typologically isolated language (Basque) (Gómez Seibane 2020). To evaluate the possible effect of language contact on variations in CD, we analysed and compared the Spanish of monolingual peninsula areas and areas where Spanish has long-term contact with Basque, Asturian, and Galician. These circumstances of intensive and prolonged language contact, bilingualism, and the linguistic attitudes of speakers are decisive in the process of linguistic variation and change (Poplack and Levey 2010, pp. 411–12; Thomason 2020, p. 37).

It should also be noted that third-person clitics are an issue of Spanish grammar with a certain internal instability due to changes in its parameters. Research has shown that in many varieties of Spanish in contact with other languages, third-person clitics generally differ from those in varieties of Spanish without this contact (Fernández-Ordóñez 1999; Gómez Seibane 2012; Palacios 2015, 2021). The most frequent changes are precisely those that affect the morphological features of gender, number, or case, as well as doubling and the omission of clitics. For many of these changes, language contact acts as an external contributing factor rather than their origin, at least in the generalisation of an existing pattern, such as dative doubling to accusative doubling, as well as the (greater) acceptability of such constructions (Fischer et al. 2019). Language contact can also lead to the maintaining of structures or the deceleration of an ongoing process of change, because in one of the languages in contact, the phenomenon in question is present to a lesser extent. This has been described in the case of 19th century Spanish in Cataluña, where contact with Catalan slowed the advance of differential object marking (Gómez Seibane and Alvarez Morera 2022).

In any case, one of the interests of this work is to verify if contact with these languages has produced, in Spanish, a change or variation in CD incorporated into the local variety of Spanish learned by natives of the region. Following Palacios (2015, 2021), clitic usage in contact areas does not result from individual interferences that each speaker activates when selecting a clitic form; rather, it is integrated as a specific feature of the language spoken by a community after a process of social conventionalisation consolidated over time. Thus, these usages are present both in those who are bilingual and those who are monolingual in Spanish who acquire their language within a contact zone.

We will now discuss doubling of the IO in other peninsular languages with which Spanish has coexisted for centuries. In the Basque language, the dative is doubly marked (Etxepare 2003, p. 411). For example, in ditransitive sentences with verbs, such as eman (‘to give’), erosi (‘to buy’), saldu (‘to sell’), or esan (‘to say’), the dative recipient is marked in (10) by the case in the nominal phrase (-i en Mireni) and by the dative affixes in the auxiliar (diozu), in which d- indicates present, -i- is an interfix, -o- indicates ‘to her’ (dative), and -zu indicates ‘you’ (ergative). As can be seen in (10), there are no clitics in the Basque language for the third person, and the auxiliary of the verb, in addition to expressing time, aspect, mode, number, and person, agrees with the arguments in the ergative or dative.

| (10) | a. | Zuk | Mireni | gezur | bat | esan | diozu. | |

| You.ERG | Miren.dat | lie | a | say.2sg | AUX.DITR | AN | ||

| You have told a lie to Miren. | ||||||||

Regarding Asturian, CD is obligatory with strong dative pronouns and practically categorical with a nominal IO (11). In fact, only in the formal register do we find a nominal IO without CD (Tuten et al. 2016, p. 405). In Galician, doubling is also obligatory for strong pronouns (12a) and widespread with nominal IO (12b) (Dubert and Galves 2016, p. 435). Furthermore, this language has a single variant lle for singular and plural referents (deille diñeiro (‘I gave money to him/her/them’)). This single dative form, which is invariable in number, is relevant to the phenomenon of depronominalization of the clitic (Section 3).

| (11) | a. | Xuan | nun-yos | da | manzanes | a | los | neños. | (Lorenzo 2022, p. 3) | ||

| John | neg-CL.dat | gives | apples | to | the | boys | |||||

| John refuses to give apples to the boys. | |||||||||||

| (12) | a. | Deille | un | regalo | a | Xoán/ | ao | neno. | (Dubert and Galves 2016, p. 421) | ||

| gave.1sg-CL.dat | a | gift | to | John | to-the | boy | |||||

| I gave a gift to John/to the boy. | |||||||||||

| b. | ??Dei | un | regalo | a | Xoán/ | ao | neno. | ||||

| gave.1sg | a | gift | to | John | to-the | boy | |||||

| I gave a gift to John/to the boy. | |||||||||||

In the peninsular Romance languages analysed here, Asturian and Galician, there is a well-known tendency towards CD of IOs. In light of this, we do not expect, in principle, that contact with these languages will be an inhibitor of CD in Spanish, nor do we expect it to be an accelerant. In any case, we will explore whether this contact has acted as a catalyst in modifying any of the syntactic, semantic, or pragmatic features of this phenomenon. In the case of Spanish contact with the Basque language, it should be noted that linguistic influence is possible across typologically non-related systems (Aikhenvald 2007; Berro et al. 2019; Matras 2010; Palacios and Pfänder 2014; Gómez Seibane 2020), and that the results of contact in Spanish have taken advantage of the grammatical tendencies in Spanish (Gómez Seibane 2021b, 2021c). For the variety of Basque Spanish, in fact, language contact acts as an external contributing factor in a greater frequency of CD of direct objects with human referents (Gómez Seibane 2021b). Considering this, along with the treatment of the IO in the verb and in nominal phrases in the Basque language, one can suppose, at least, a maintenance of the frequency of CD in the IO in Spanish if not a degree of intensification of this phenomenon.

Apart from that, some informative factors of doubling are studied. Following on Rinke et al. (2019, p. 3), the doubled IO is interpreted as (part of) the focus domain; that is, information that is not shared between the speaker and listener at the moment of conversation or in a given discourse (Zubizarreta 1999, p. 4224). To describe the informational meaning of doubling, we analyse the cognitive accessibility of the referents in the minds of the speakers. Accepting the tripartite distinction proposed by Chafe (1987), this work distinguishes between active referents (that is, those concepts that are present in the minds of the interlocutors) and semiactive referents (that is, those about which the interlocutors have a peripheral awareness, either because they were mentioned before or form part of the framework or schema, containing a set of interrelated expectations that may be shared by the speakers). As for inactive referents, these lie in the long-term memory of the interlocutors (occasionally, only the speaker) and are neither focally nor peripherally active.

2.2. Research Questions and Hypotheses

1. What is the frequency of CD of the IO in a peninsular Spanish corpus that incorporates historical language contact (Basque, Asturian, and Galician) and a zone without historical language contact? To what extent does language contact influence the frequency of this phenomenon?

In principle, we suppose a high frequency of CD in the analysed zones of peninsular Spanish, with very slight differences between them. Although language contact can affect the speed of this phenomenon, the tendency towards doubling in languages in contact with Spanish does not predict any substantial changes.

2. What is the role of semantic factors in CD of the IO?

We expect that the semantic factors analysed (that is, animation, definiteness, specificity, number, and negation) influence CD, but we do not expect to find a statistically significant relation between CD and the factors analysed, given that the high degree of extension of CD will have neutralised these distinctions.

3. What is the role of syntactic and pragmatic factors in CD of the IO?

As the doubled IO is considered (part of) the focus domain, we expect CD to be predominantly with referents that are semiactive or inactive in the minds of the interlocutors and less frequent with active referents. We also suppose that some syntactic factors, such as the clitic realization of direct objects, favour CD of the IO, in view of the outcomes of judgements of acceptability.

4. What are the differences between these two Spanish corpora?

In the case of differences, we suppose that these are related to factors that have been less analysed until now, such as the cliticization of the direct object or the degree of accessibility of the referents.

3. Materials and Methods

The data analysed in this paper were taken from two open-source oral corpora. A total of 59 semidirected interviews with an informal register were analysed. The speakers were both men (39) and women (20) between the ages of 21 and 55 with different levels of education, born and residing in the regions where the interviews took place. The total duration of the interviews was approximately 65 h. The data were taken as a whole while also taking into account the linguistic situation of peninsular Spanish, thereby distinguishing areas with historical contact with another language (Basque, Asturian, or Galician), which was labelled CorpusC, from areas without historical contact with other languages, labelled CorpusM.

Interviews with bilingual speakers of European Spanish, conducted in 2021 and 2022, were taken from the Corpus del Español en Contacto (COREC)6 (specifically, with speakers of Spanish in contact with Basque and with Asturian7). Interviews conducted in Santiago de Compostela8 (2007–2015) were taken from the Proyecto para el estudio sociolingüístico del español de España y de América (PRESEEA)9 and added to the previous interviews, because, in this city, Spanish is in contact with Galician, creating CorpusC. Additionally, interviews conducted in Santander (2014–2017), Alcalá de Henares (Madrid) (1991–1998), Madrid (2001–2003), and Málaga (1994–2001)10 were collected from PRESEEA to create CorpusM.

In analysing the data, we focussed on the variable context in which the phenomenon of CD takes place. We followed the idea of variationist sociolinguistics, according to which the distribution of a phenomenon involves a consideration of what Labov referred to as its “envelope of variation.” This means taking into account all actual occurrences of the phenomenon in addition to “all those cases where the form might have occurred but did not” (Tagliamonte 2006, p. 86).

Of the types of IO, those that designate the recipient of an action or a process were selected, as in (3b), and those that express location, as in (3d). These two types of IOs are dealt with together as they share a number of similarities and because doubling of the IO is optional (RAE-ASALE 2009, pp. 2686–84). In order to consider the variable context of CD, we extracted all of the ditransitive sentences containing a direct and indirect object and coded them for the present study.

First, we excluded contexts in which the IO was a strong pronoun (13a), a strong pronoun in coordination with other NPs (13b), or a relative pronoun (13c). In (13c), the relative (que) appears without the preposition corresponding to its IO function within the subordinate clause and doubled by singular dative clitic (le), instead of the “expected” plural clitic, a phenomenon labelled le-for-les in the Spanish grammatical tradition that we will explain in this section. The doubling structure in (13c) is normatively incorrect but relatively frequent in colloquial speech. Here, the relative has become a simple marker of subordination, and the clitic indicates the syntactic function of the relative (Brucart 1999, pp. 403–404). In the sentences of (13), CD is mandatory and, therefore, does not form part of the variable context.

| (13) | a. | Yo | se | lo | dije | a | él. | (PRESEEA; SC 12_020) |

| I | CL.dat | CL.acc | said.1sg | to | him. | |||

| I told that to him. | ||||||||

| b. | Se | le | alquiló | el | monte | a | (COREC; V/G) | |

| CL.IMP | CL.dat | rented.3sg | the | mountain | to | |||

| él | a | su | padre | y | a | |||

| him | to | his | father | and | to | |||

| otro | señor. | |||||||

| another | man | |||||||

| They rented all of it to him and his father and to another man. | ||||||||

| c. | Más | bien | los | que | tú | le | (PRESEEA; MA 13_065) | |

| more | well | the | that | you | CL.dat | |||

| pedirías | un | favor. | ||||||

| ask.2sg | a | favour | ||||||

| Rather that you ask him for a favour. | ||||||||

Second, given that we are focussing on the IO in the canonical position, we eliminated cases of clitic left dislocations (14a) and right dislocations (14d). In our corpora, dislocation may be followed by another constituent inserted between the verb and the object, as with pues in (14c), or by a prosodic break, indicated in the corpora by (/,//), as in (14b) and (14d). Preverbal IOs not prosodically separated from the rest of the statement or with interspersed constituents (14a) were also excluded from the analysis because doubling vs. non-doubling leads to a topic/focus reading of the object.

| (14) | a. | Al | gobierno | español | intentaron | venderle | unos | (PRESEEA; MA 12_712) |

| to-the | goverment | Spanish | tried.3pl | sell-CL.dat | some | |||

| cañones | defectuosos. | |||||||

| cannons | defective. | |||||||

| To the Spanish government, they tried to sell defective cannons. | ||||||||

| b. | A | amigos | que | se | han | casado/ | (PRESEEA; MA 12_710) | |

| to | friends | who | CL-PRON | have.3pl | married | |||

| les | he | hecho | misterios. | |||||

| CL.dat | have.1sg | made | mysteries | |||||

| To friends who have married/I have made mysteries (craftwork). | ||||||||

| c. | Al | de | Flores | pues | le | dijo | (PRESEEA; MA 21_734) | |

| to-the | of | Flores | well | CL.dat | told.3sg | |||

| “a | ver | si | me | buscas/ | una | |||

| to | see | if | CL.dat | find.2sg | a | |||

| portería.” | ||||||||

| reception | ||||||||

| To Flores, I told him to see if he could find me a reception. | ||||||||

| d. | Aquí | sí/ | sí | di | rienda | suelta/ | (PRESEEA; M 12_007) | |

| here | yes | yes | gave.1sg | rein | free | |||

| al | tema. | |||||||

| to-the | subject | |||||||

| Here yes/yes I gave free rein/to the subject. | ||||||||

Third, we discarded constructions exhibiting an exceptional behaviour for the linguistic variation; that is, memorised in songs, traditional expressions, or sayings, such as (15). These types of structures were not included in the analysis because they are highly imitative (Tagliamonte 2006, pp. 90–91).

| (15) | Quién | le | pone | el | cascabel | al | gato. | (PRESEEA; SC 22_024) |

| who | CL.dat | put.3sg | the | bell | to-the | cat | ||

| Who will put the bell on the cat, eh? | ||||||||

Fourth, all constructions with the IO in a canonical position were coded according to the following features: +/− doubling, +/− animate, +/− definite, +/− specific, number, cliticization of the DO, and negation. We included two factors unexamined in the existing literature to date; that is, the degree of accessibility of the referent in the mind of the interlocutors and if the location of the interview was a location of historical language contact or not. We considered doubling vs. non-doubling as the dependent variable and the various grammatical, semantic, and pragmatic features and those related to language contact as independent variables. Chi-squared analyses were performed of the data using a significance level of α = 0.05 (IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0).

Each IO construction was coded according to the following independent variables: animation (animate, inanimate), number (singular, plural), definiteness (definite, indefinite), specificity (specific, non-specific), cliticization of the direct object (yes, no), negation (affirmative, negative), accessibility (active, semiactive, inactive), and area of contact (yes, no). Here, certain clarifications are in order. In terms of animation, the referents that are religious images, such as Cristo (‘Christ’) or Virgen (‘Virgin’) were codified as inanimate (16a). In turn, those referring to a human collective, such as pueblo (‘village’), were considered animate (16b), as were objects controlled by people, such as coche (‘car’) (16c).

| (16) | a. | Le | tiene | una | devoción | especial | a | (PRESEEA; MA 13_065) |

| CL.dat | has.3sg | a | devotion | special | to | |||

| un | Cristo. | |||||||

| a | Christ | |||||||

| He has a special devotion to Christ. | ||||||||

| b. | Me | gusta | darle | vida | al | pueblo. | (COREC; M) | |

| CL.dat | like.3sg | give-CL.dat | life | to-the | town | |||

| I like to give life to the town. | ||||||||

| c. | El | del | autobus | le | dijo | a | (PRESEEA; M 11_004) | |

| the | of-the | bus | CL.dat | told.3sg | to | |||

| un | coche | que | pasara. | |||||

| a | car | that | went.3sg | |||||

| The guy of the bus told the car to pass. | ||||||||

As for (in)definiteness, we recall that the referent of the nominal phrase may (or may not) be identified without ambiguity within the context. In many cases, the identification is immediate, while in others, the listener inferentially recovers the implicit content (Leonetti 1999, pp. 794–95). (Non)-specificity refers to the property of the entities (real or imaginary) when identified (or not) with a specific referent. In this way, the definite phrases (al tutor) are generally specific (17a), while the indefinite phrases (a algún hombre) are generally non-specifics (17b).

| (17) | a. | Yo | le | pregunto | al | tutor. | (COREC; M) | |

| I | word b’ | ask.1sg | to-the | tutor | ||||

| I ask the tutor. | ||||||||

| b. | Estuve | a | punto | de | decirle | a | (PRESEEA; AH 11_037) | |

| was.1sg | a | spot | of | tell-CL.dat | to | |||

| algún | hombre | que | saliera | a | ayudarte. | |||

| some | man | that | came.3sg | to | help-CL.acc/dat | |||

| I was about to tell some man to go out and help you. | ||||||||

However, it is possible for an indefinite nominal phrase (a una amiga) to be specific because it refers to a particular individual (18b). In parallel, a definite nominal phrase (a las palabras) is non-specific when it does not have a particular referent (18a). In this way, bare plural nouns (a cosas) show a non-specific reading because they do not refer to a particular object or idea (19). In any case, specificity is a variable that favours doubling in the corpus of Madrid (Rinke et al. 2019, pp. 30–31).

| (18) | a. | Si | le | das | muchas | vueltas | a | (PRESEEA; SC 13_012) |

| if | CL.dat | give.2sg | many | turns | to | |||

| las | palabras | (…) | pierden | el | sentido. | |||

| the | words | lose.3pl | the | meaning | ||||

| If you think too much about the words, they lose their meaning. | ||||||||

| b. | Le | voy | a | regalar | a | una | (PRESEEA; MA 12_710) | |

| CL.dat | go.1sg | to | give | to | a | |||

| amiga | (un abanico)/ | que | sé | que | le | |||

| friend | (a fan) | who | know.1sg | that | CL.dat | |||

| gusta. | ||||||||

| like.3sg | ||||||||

| I am going to give it to a friend (a fan)/who I know she likes it. | ||||||||

| c. | A | veces | le | damos | importancia | a | (PRESEEA; SC 22_024) | |

| at | times | CL.dat | give.1pl | importance | to | |||

| cosas | que | realmente | no | tienen. | ||||

| things | that | really | not | have.3pl | ||||

| Sometimes, we give importance to things they really do not have. | ||||||||

Regarding number, although this variable is examined in other works on CD of IOs (Rinke et al. 2019, p. 30; Dickinson et al. 2021), we find constructions in which plural IOs are doubled by singular dative clitics (19) with some frequency (26.4%) (38/144)11. This le-for-les phenomenon, also known as cliticization of the object (Company 2003; Huerta Flores 2005; Pineda 2019), is found in different regions of the corpora.12 See also examples in (18a), (18c), (22b), and (23b). This may be considered an ongoing linguistic change that is part of a process of grammaticalisation of le as an agreement marker.

| (19) | a. | Le | decía | a | los | hijos | “haz | (PRESEEA; SA 33_014) |

| CL.dat | said.1sg | to | his | sons | do.2sg | |||

| esto.” | ||||||||

| this | ||||||||

| He said to the kids “do this.” | ||||||||

| b. | Luego | sí | que | le | echo | un | (COREC; P) | |

| later | yes | that | CL.dat | throw.1sg | a | |||

| vistazo | a | los | periódicos | digitales. | ||||

| look | to | the | newspapers | digital | ||||

| Later, I did take a look at the digital newspapers. | ||||||||

As in (19), in a total of 38 statements of the corpus, the clitic doubling is singular (le), while the nominal IO is plural (a los hijos, a los periódicos digitales). Despite non-agreeing examples, we include the number of the referent (singular or plural) as a variable in our frequential and statistical analysis.

One syntactic factor that appears to favour doubling of the IO is the cliticization of the direct object. Considering speakers’ acceptability judgments, doubling of the IO was the most frequent construction (95.8%) in contexts where the accusative is cliticized (Galindo 2020). Thus, (20a) is a more frequent statement than (20b). In the data, this variable was codified by distinguishing accusative clitics (21a), NP (21b), and clauses (21c).

| (20) | a. | Se | lo | presenté | a | mi | madre. | ||||

| CL.dat | CL.acc | introduced.1sg | to | my | mother | ||||||

| I introduced him to my mother. | |||||||||||

| b. | Lo | presenté | a | mi | madre. | ||||||

| CL.acc | introduced.1sg | to | my | mother | |||||||

| I introduced him to my mother. | |||||||||||

| (21) | a. | Se | lo | preguntamos | a | mi | madre. | (COREC; G) | |||

| CL.dat | CL.acc | ask.1pl | to | my | mother | ||||||

| We asked my mother. | |||||||||||

| b. | Yo | le | decía | a | mi | madre | (PRESEEA; SA 11_037) | ||||

| I | CL.dat | said.1sg | to | my | mother | ||||||

| “mamá | no | entiendo.” | |||||||||

| mum | not | understand.1sg | |||||||||

| I said to my mother: “Mum, I do not understand.” | |||||||||||

| c. | Le | preguntas | a | una | dependienta | que | (PRESEEA; SC 11_040) | ||||

| CL.dat | ask.2sg | to | a | shop assistant | that | ||||||

| dónde | están | los | aspiradores. | ||||||||

| where | are.3pl | the | hoovers | ||||||||

| You ask a shop assistant where the hoovers are. | |||||||||||

Along with these syntactic–semantic factors, there are others of an informative nature that have not yet been fully explored. As (part) of the focus domain, the doubled IO is supposed to convey (relatively) new, non-shared, or contrastive information (Zubizarreta 1999; Rinke et al. 2019). In accordance with these observations and with Chafe (1987), we distinguish three referents depending on their degree of accessibility in the speakers’ mind. Active referents tend to contain pronouns, as in (22a), where eso refers to the immediately preceding clause (empezaba a sentirme importante), or they tend to be a nominal phrase (a estas cosillas) (22b), which alludes to a referent mentioned in the previous sentence.

| (22) | a. | Empezaba | a | sentirme | importante | y | entonces | (COREC; G) |

| started.1sg | to | feel-CL-PRON | important | and | then | |||

| yo | le | tenía | mucho | miedo | a | |||

| I | CL.dat | had.1sg | much | fear | to | |||

| eso. | ||||||||

| that | ||||||||

| I started to feel important, and then I was very afraid of that. | ||||||||

| b. | No | uso | ni | casco | ni | luces | (COREC; P) | |

| not | use.1sg | neither | helmet | nor | lights | |||

| ni | de | estas | cosillas | y | entonces | (…) | ||

| nor | of | these | things | and | then | |||

| están | dándole | mucha | importancia | a | estas | cosillas. | ||

| are.3pl | give-CL.dat | much | importance | to | these | things | ||

| I do not use a helmet or lights or any of those things, and then they are giving a lot of importance to those little things. | ||||||||

The semiactive referents are so in two ways: either through the deactivation of a previously active state (due to limitations of attention and short-term memory) or by being activated through association with an idea that is or was active in the discourse. The first case generally occurs when there are various clauses between the mention of the referent and the doubling, as in the case of ama (‘mum’) in (23a). Furthermore, a referent is semiactive when, once mentioned, it is reintroduced through a new referent. This is the case in (23b), when speaking about the press, where periódicos locales (‘local newspapers’) has as referents certain newspapers mentioned just before, such as Faro de Vigo, Correo, or La Voz (de Galicia).

| (23) | a. | Acostumbrarte | a | que | tu | ama | te | (COREC; VG) |

| get used-CL-PRON | to | that | your | mum | CL.dat | |||

| lo | haga | todo (…) | me | sirvió | irme | de | ||

| CL.acc | do.3sg | all | CL.dat | used.1sg | go-CL-PRON | of | ||

| Erasmus (…) | me | di | cuenta | y | se | lo | ||

| Erasmus | CL-PRON | gave.1sg | count | and | CL.dat | CL.acc | ||

| dije | a | mi | ama. | |||||

| told.1sg | to | my | mum | |||||

| Get used to your mum doing everything… but it helped me a lot to do an Erasmus… I realised/and I told my mum. | ||||||||

| b. | Cada | día | te | llega | Faro de Vigo/ | Correo | (PRESEEA; SC 22_024) | |

| every | day | ED | arrives.3sg | Faro de Vigo | Correo | |||

| La Voz (…) | le | echas | un | vistazo | también | |||

| La Voz | CL.dat | throw.2sg | a | look | also | |||

| a | los | periódicos | locales. | |||||

| to | the | newspapers | local | |||||

| Every day they arrive (Faro de Vigo/Correo/La Voz) (…) you also take a look at the local newspapers. | ||||||||

In the second case, the referents that appear for the first time in the discourse are semiactive when identifiable through some connection (textual or inferential) with the context of the interaction. These form part of the so-called conversational framework or schema. An example of this is (24), where the IO a un cristo is considered semiactive based on the conversation about Holy Week and attendance at Mass.

| (24) | Una | persona | que | no | va | nunca | (PRESEEA; MA 13_065) |

| a | person | who | not | goes.3sg | never | ||

| a | misa/ | a | lo | mejor | le | ||

| to | mass/ | to | the | better | CL.dat | ||

| tiene | una | devoción | especial | a | un | Cristo. | |

| has.3sg | a | devotion | special | to | a | Christ | |

| A person who never goes to Mass/maybe they have a special devotion to Christ. | |||||||

The new referents that are not accessible textually or inferentially by the interlocutor are considered inactive. For example, in (25), when aspects of gardening are explained, the neighbour is not present in the mind of the listener.

| (25) | Yo | siembro | de | esas | semillas/ | y | (PRESEEA; MA 21_734) |

| I | sow.1sg | of | those | seeds | and | ||

| le | doy | semillas | al | vecino. | |||

| CL.dat | give.1sg | seeds | to-the | neighbour | |||

| I sow those seeds/and I give seeds to the neighbour. | |||||||

| (26) | Les | tengo | verdadero | odio | a | las | (PRESEEA; AH 12_019) |

| CL.dat | have.1sg | true | hate | to | the | ||

| cartas. | |||||||

| cards | |||||||

| I have a real hatred of card games. | |||||||

Finally, it is common to find construction with a light verb followed by a noun and recipient or location argumental IOs (RAE-ASALE 2009, pp. 2670–71), such as dar importancia (a algo) (‘give importance to something’), echar un vistazo (a algo) (‘take a look at something’), and tener odio (a algo) (‘have a hatred for something’). In (23b), (24b), and (26), examples are provided to illustrate these structures.

4. Results

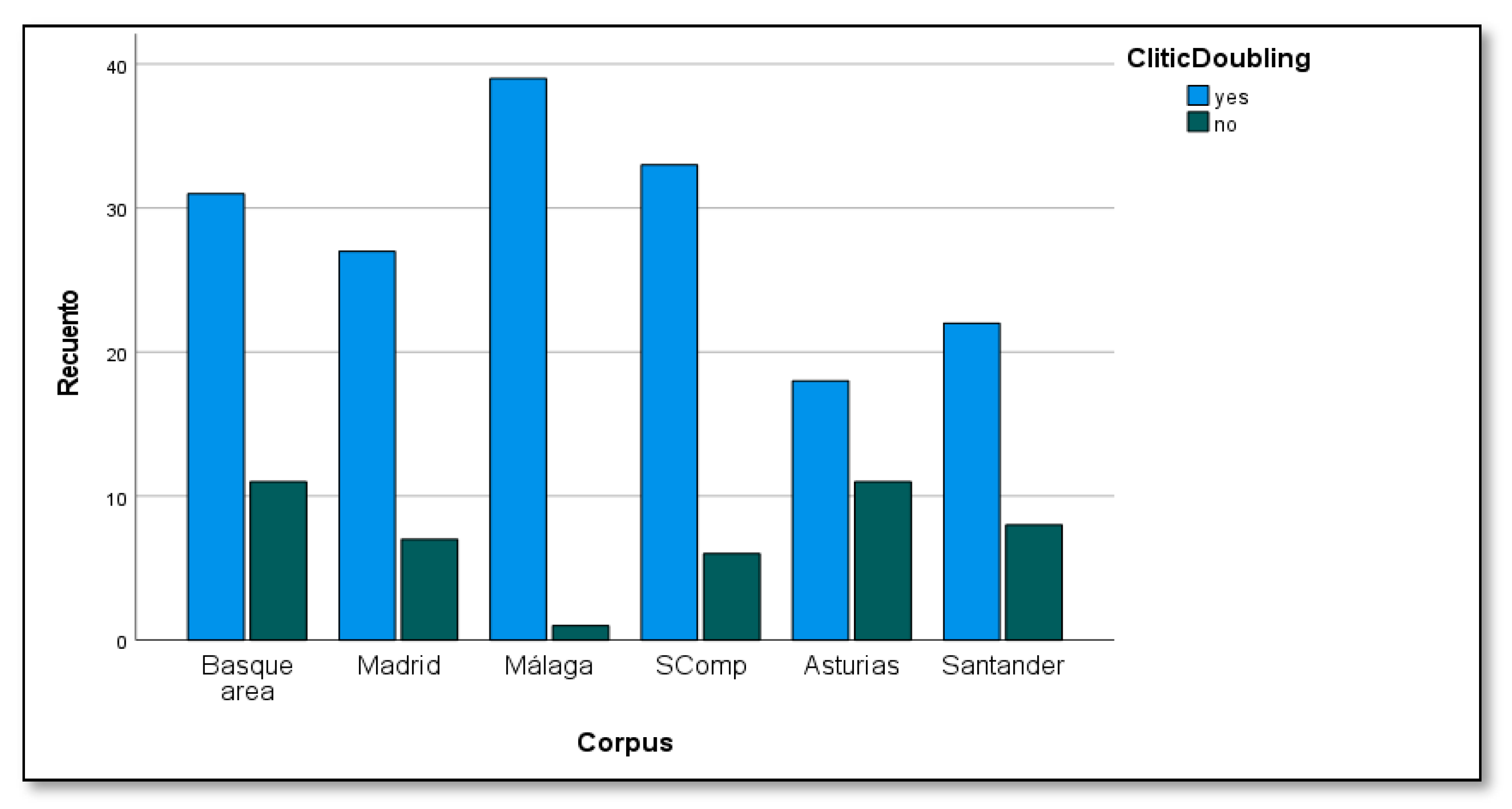

For peninsular Spanish, a total of 214 cases were analysed, in which doubling occurred in 79.4% of cases (170/214), while in 20.6% of cases (44/214), doubling did not occur. Distributing the results geographically (Figure 1), the percentages of frequency were lowest in the Asturian region (62.1%, 18/29), intermediate in Santander (73.3%, 22/30), the Basque region (73.8%, 31/42), and Madrid (79.4%, 27/34), and highest in Santiago de Compostela (84.6%, 33/39) and Málaga (97.5%, 39/40). The data show that between the different regions, there were statistically significant differences in doubling (χ2(5) = 15.485; p < 0.008). The general results of our corpus (79.5%) are in line with the results of Rinke et al. (2019, p. 30) for Madrid (81.8%), where two factors were statistically significant for doubling: the benefactive role and specificity.

Figure 1.

CD of IO geographically.

In our corpus, depending on the type of IO, we found that both those of recipient (81.9% (140/175)) and of location (77.5% (30/39)) mostly opt for CD. Table 1 shows that CD occurs with animate (80.4%) and inanimate (77.2%) referents and somewhat more with definite referents (81.1%) than indefinite referents (71.8%), and it also shows a degree of preference for specific (84.5%) over non-specific referents (70.5%) and for singulars (84.3%) over plurals (67.2%). Equally, CD appears to be largely influenced by the cliticization of the direct object. The data show that sentences with accusative clitics strongly prefer CD (96%), although CD is also selected when the direct object is an NP, a phrase, or a clause (77.2%). A Chi-Square test shows that in Peninsular Spanish, the difference between clitic and non-clitic direct objects regarding CD is statistically significant (χ2(1) = 4.753; p < 0.029), as is the difference between singular and plural regarding CD, as well (χ2(1) = 7.808; p < 0.005). Concerning the accessibility of the referent, doubling is prevalent in all contexts, including with semiactive (86.7%), active (77.2%), and inactive (75.8%) referents. In terms of negation, CD is very common in sentences with affirmative polarity (80.1%) and occurs less frequently with negative polarity (62.5%). It should be recalled that affirmative polarity is the only statistically significant factor in Spanish in Buenos Aires (Rinke et al. 2019, pp. 30–31), where CD with the IO is practically categorical (91.4%).

Table 1.

Results of nominal IO doubling in the peninsular Spanish corpus.

A comparison of CorpusC, the corpus of Spanish in contact with Galician, Basque, or Asturian, and CorpusM, that of monolingual regions, reveals that CD is more common in CorpusM (84.6% (88/104)) than in CorpusC (74.5% (82/110)). Continuing the analysis of CorpusM, CD is common for both recipient (86.5% (71/82)) and location (77.2% (17/22)) IOs. As shown in Table 2, regarding animation, CD is common with animate (84.2%) and inanimate (85.7%), definite (83.7%) and indefinite (88.8%), and specific (85.3%) and non-specific (82.7%) IOs. Furthermore, doubling is found in sentences with clitic (90.9%) and non-clitic (83.8%) direct objects. But, a singular number significantly favours the use of CD (89.8%) compared to plural (68%). In fact, there is a statistically significant relation between CD and the number of the referent (χ2(1) = 6.980; p < 0.008). Regarding accessibility, as expected, when describing the nominal IO as part of the focus domain, CD is found in the majority of semiactive (86.3%) and inactive (86.2%) referents, while it is less frequently seen with active referents (66.6%).

Table 2.

Results of nominal IO doubling in CorpusM.

In CorpusC, and depending on the type of IO, we find that both the recipient (74.1% (69/93)) and location (76.4% (13/17)) are doubled. For animation (Table 3), CD is found with animate (76.3%) and inanimate (71%), and more frequently with definite (78.6%) and specific (83.6%), than indefinite (57.1%) and non-specific (63.2%). In fact, there is a statistically significant relation between CD and definiteness (χ2(1) = 4.143; p < 0.042), as well as between CD and specificity (χ2(1) = 5.925; p < 0.015). Equally, CD is influenced by the cliticization of the direct object. In fact, predicates with accusative clitics have 100% CD (14/14), with a statistically significant difference between CD and the cliticization of this object in CorpusC (χ2(1) = 5.478; p < 0.019). Regarding accessibility, CD is found, in the majority of cases, in this order: with active (84.6%), semiactive (87.5%), and inactive (68.5%) referents.

Table 3.

Results of nominal IO doubling in CorpusC.

Examining the statistically significant data on CD related to definiteness, specificity, number, and cliticization of the direct object and focusing on the different regions of the two corpora, we see that, regarding definiteness (Table 4), CD with a definite object is more common in CorpusC (81.8% and 87%) and less prevalent with indefinite objects (44% and 66.6%), particularly in the Basque region. This is not the case in Asturias, which shows the inverse: CD is more common with an indefinite (81.8%) than with a definite (60.8%) IO. In CorpusM, CD with an indefinite IO is systemic (100%), with the exception of Santander, where CD occurs with ±definite (75% and 66.6%). In Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, we introduce a simple equation to determine the ratio between two percentage results. The ratio is calculated for binary features by dividing the percentage of the positive feature by the percentage of the negative feature (Rasinger 2020, pp. 117–18). The resulting value indicates how much greater (or not) one feature is than the other. If the value is close to 1, they are similar; if it is bigger than 1.5, it indicates that the positive value is much greater than the negative. In the Basque region, definite objects are the most active feature in the corpus, given the data of 1.85.

Table 4.

Definiteness in CD geographically.

Table 5.

Specificity in CD geographically.

Table 6.

Cliticization of direct objects in CD geographically.

Regarding specificity (Table 5), CorpusC shows a higher frequency of CD with a specific (87.5% and 76.1%) than with a non-specific (55.5% and 25%) IO, except for Santiago de Compostela, where the frequency of CD shows practically no difference in relation to specificity (87.5% and 82.6%). Here, again, CorpusM differs from CorpusC, although not homogenously. Thus, in Madrid and Málaga, CD with an IO is categorical, regardless of specificity, while in Santander, CD is more common with a specific (84%) than a non-specific (54%) IO. In fact, it should be noted that the ratio in Santander and the Basque region is greater than 1.5, and, in Asturias, the ratio is 3.05, showing that this factor is still very important in terms of CD.

Regarding cliticization of the direct object as an influential factor in the CD of the IO (Table 6), in the Basque region and Asturias, the importance of this feature for duplication is quite noticeable, as the ratios of 1.50 and 1.68 show. In Santiago de Compostela, Madrid, and Málaga, the percentages of CD are similar in both contexts (accusative clitic and nominal/clausal direct object); thus, it does not appear to be a substantial factor.

Concerning number (Table 7), doubling occurs more often in singular than in plural, except in the Basque region. In addition, the ratio between percentages is quite important in Asturias (CorpusC), with a ratio of 1.68, but particularly in Santander (CorpusM), where the ratio (2.30) reveals the influence of this factor in CD. In contrast, in Santiago de Compostela, Málaga, and the Basque region, the percentages of CD with singular and plural are quite similar.

Table 7.

Number in CD geographically.

5. Discussion

CD in non-mandatory contexts for recipient and location IOs is very frequent in the analysed corpora of peninsular Spanish. In all, there are statistically significant differences in the frequency of doubling across different regions. This is a first conclusion, and we will evaluate later if contact languages may be influencing the rate of extension of this phenomenon.

The doubled IO within this corpus, taken as a whole, can be described as ±animate, ±definite, ±specific, and ±singular. In fact, number is the only semantic variable that shows a statistically significant relation with doubling (χ2(1) = 7.808; p < 0.005). However, the lack of evidence of an effect should not be taken as proof of its absence; but, where there is, it will most likely be practically or theoretically insignificant (Vasishth and Gelman 2021). This suggests that these semantic distinctions, organised in scales and revealing the diachronic extension of CD, are currently weakened or cancelled for IOs. The second conclusion drawn from these results for the oral corpus of peninsular Spanish is that the lack of statistically significant differences between CD and the majority of the semantic variables analysed confirms the weakening of the original value of these variables, for which the scope has been neutralised in favour of almost categorical doubling of IOs.

The neutralisation of semantic features should be taken as a sign that the linguistic change is currently underway towards the obligatory use of CD of IOs. This third conclusion is supported by another phenomenon seen in the corpora: the lack of numerical concordance between the clitic le and its plural referent, which is found in all geographical regions and with a significant degree of frequency (26.4%). It would therefore appear that as doubling becomes more generalised, le is transformed into a grammatical marker of the verb to indicate the presence of an IO (Company 2003; Huerta Flores 2005; Pineda 2019).

Furthermore, CD of IOs occurs in sentences with affirmative or negative polarity, and with direct objects that may (or may not) be cliticized. But, a Chi-Square test shows that the difference between the proportions of doubling of clitic and non-clitic direct objects is significant in Peninsular Spanish (χ2(1) = 4.712; p < 0.030), as we explain in more detail below. Doubled IOs may refer to semiactive entities in the minds of the interlocutors, and also active or inactive entities.

In addition to these general conclusions drawn from the corpora of peninsular Spanish, differences can be noted between the corpus of Spanish in contact with Galician, Basque, or Asturian (CorpusC) and the monolingual corpus (CorpusM). According to our analysis, doubling is more systematic in CorpusM than in CorpusC. The description of CD in CorpusM generally coincides with the data presented above in that there is only a statistically significant relation between CD of IOs and number but not with animacy, definiteness, or specificity. Again, the advance of CD in the referential hierarchy reveals a loss of distinction between more or less marked contexts. Additionally, with reference to accessibility, CD is more frequent with semiactive or inactive referents and less frequent with active referents, which fits the description of the nominal IO as (part of) the focus domain. Thus, CorpusM shows a greater frequency of CD of IOs (84.6%), a neutralisation of semantic factors of referential hierarchy, and accessibility of IO referents according to their description of focal information (Rinke et al. 2019).

In CorpusC, however, there are statistically significant referential properties in CD, such as definiteness and specificity. As the data show, CD is more frequent with definite and specific referents. This suggests the importance of these semantic factors and confirms the lesser extension of CD within this corpus. Furthermore, the syntactic context is relevant to the CD, given that direct objects in clitic form favour the CD of dative nominal objects at a higher (and statistically significant) percentage than those contexts with nominal/clausal direct objects. In turn, there is a high rate of CD with active entities, as well as semiactive and, less commonly, with inactive entities, which is contrary to that expected and described for CorpusM. In this case, it is not a question of a lesser spread in the referential hierarchy but rather a different treatment of the information, the evaluation of which requires more data and examination. In CorpusC, the referential hierarchy is still applied to a certain extent, the clitic realization of direct objects favours CD of Ios, and the accessibility of referents disagrees with its description as (part of) the focus.

However, in CorpusC, the characterisation of CD is not uniform in terms of definiteness and specificity. The Basque region and Santiago de Compostela tend to favour CD with a definite object, in contrast to Asturias, which coincides on this point with CorpusM. In turn, a specific IO is more frequent in CD in the Basque region and Asturias compared to Santiago de Compostela, which shows no clear preferences. CorpusM shows a degree of variation in these factors (although not statistically significant), and the data for Santander are similar to those of the Basque region.

One may question the influence or action of language contact in those regions where it takes place. The response may be varied. In terms of the spread of CD of IOs, language contact may have had no effect, as in the Basque region (Spanish–Basque contact), it may have acted as an enhancer, as seen in Santiago de Compostela (Spanish–Galician contact), or it may have acted as an inhibitor, as in Asturias (Spanish-Asturian contact), contrary to what we supposed (Section 2.1). Concerning the features (definiteness and specificity), in the Basque region, language contact appears not to have had an effect (or to have preserved some features), because this is the region that better maintains the referential hierarchy that explains the diachronic evolution of doubling. In contrast, in Asturias and Santiago de Compostela, doubling seems to be less aligned with this hierarchy, and, in particular, with definiteness and specificity. Further research should verify the main trends seen here by using oral corpora in combination with speakers’ attitudes, which may explain their linguistic choices (Thomason 2020).

6. Conclusions

The following are the principal conclusions of this work upon returning to our research questions. Regarding frequency, the general result of our corpus shows a rate of CD of 79.4%, which is close to the result obtained by Rinke et al. (2019, p. 30) for Madrid (81.8%). All in all, there are statistically significant differences in the frequency of CD according to region, with the lowest percentages in Asturias (62.1%) and the highest in Málaga (97.5%). The corpus of the language contact area (CorpusC) is that which shows the most dissimilar results, which supports the hypothesis that contact languages could be influencing the speed with which the phenomenon spreads. Upon analysing the rate of CD, language contact may have acted as a stimulant, as in Santiago de Compostela (Spanish–Galician), as an inhibitor, as in Asturias (Spanish–Asturian), or it may not have occurred, as in the Basque region (Spanish–Basque). This initial perception should be verified in future research.

In terms of characterisation, for this corpus, taken as a whole, there is statistically significant relation between doubling and number, but not with the other three semantic factors analysed (animation, definiteness, and specificity). Hence, the factors that showed the path for the development of doubling are currently neutralised for CD of IOs. Clearly, the explanatory and predictive value of these factors is undermined in favour of the extension of doubling of IOs. In fact, the frequency of CD of IOs and the neutralisation of the majority of the semantic factors show that dative clitic doubling is progressing towards an obligatorification. One consequence of this is the transformation of the doubling clitic le into a marker, as perceived in the rate of singular dative clitics doubling plural IOs.

Taking the data as a whole, the cliticization of the direct object appears to be a factor favouring the doubling of IOs, particularly in the Basque region and Asturias. The analysis of the referents in the minds of the interlocutors accommodates, to a certain extent, their consideration as (part of) the focus domain. Thus, we find that doubled IOs are, above all, semiactive referents in the conversation, and they may be inactive, as they are not active or present in the communicative context. Below, we will take note of differences in this regard between CorpusM and CorpusC.

The differences between the two corpora are related to the frequency of doubling, the definiteness and the specificity of referents, the influence of cliticization of the direct object, and the degree of accessibility of referents of the doubled IO in the mind of the speaker. Firstly, doubling is more systematic in CorpusM (84.6%) than in CorpusC (74.8%). Secondly, there are two semantic factors in CorpusC—definiteness and specificity—that show a statistically significant relation with doubling, which confirms the referential hierarchy in this corpus, mainly in the Basque region. In CorpusM, however, the validity of this hierarchy has expired as a result of the high frequency of doubling with IOs. Third, in CorpusC, the syntactic context contributes to doubling. The clitic realization of direct objects favours the CD of dative nominal objects, mainly in the Basque region and Asturias. Finally, regarding accessibility, in contrast to CorpusM, which coincides with the description of the nominal IO as (part of) the focus domain, CorpusC shows a high rate of CD with semiactive and active entities, and with less frequency with inactive entities (that is, contrary to expectations).

Funding

This research is part of the project “COREC: Corpus Oral de Referencia del Español en Contacto. Fase I: Lenguas Minoritarias” headed by Azucena Palacios (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid) and Sara Gómez Seibane (Universidad de La Rioja), funded by the Spanish Ministry for Science and Innovation (grant number PID2019-105865GB-I00).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the public nature of the audio recordings used in the analysis.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived as the audio data were drawn from pre-recorded, publicly-available sources.

Data Availability Statement

Most of the data is available on COREC (https://espanolcontacto.fe.uam.es/wordpress/) and PRESEEA (https://preseea.uah.es/), accessed on April–May 2023. The rest will be available on COREC in June 2024.

Acknowledgments

I extend my gratitude to Gadea Mata Martínez (Universidad de La Rioja) and Nuria Polo Cano (Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia) for their advice and recommendations for statistical analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACC | accusative |

| AUX | auxiliary |

| CD | clitic doubling |

| COREC | “Corpus Oral de Referencia del Español en Contacto” |

| CL | clitic |

| DAT | dative |

| DITRAN | ditransitive |

| ED | ethical dative |

| ERG | ergative |

| IMP | impersonal |

| IO | indirect object |

| PL | plural |

| PRESEEA | “Proyecto para el Estudio Sociolingüístico del Español de España y de América” |

| PRON | pronominal (verb) |

| SG | singular |

Notes

| 1 | In this work, clitics refer to the weak (unstressed) pronouns attached to a verb upon which they depend phonologically (Fernández Soriano 2015, p. 423). We use cliticization when a nominal or phrasal object is replaced by an anaphoric clitic pronoun. We focus on non-person clitics or third-person clitics that distinguish case (dative or accusative) in the standard dialect. Gender and number are decisive in the selection of accusative clitic (masculine lo/s and feminine la/s) because the dative clitic (le/s) does not exhibit any distinction for gender, just for number. We also distinguish between nominal/clausal object, formed by a noun, phrase, or clause, and pronominal object, formed by a strong (stressed) pronoun. | ||||||||

| 2 | For a synthesis of the various theoretical proposals on doubling, see Belloro (2015). | ||||||||

| 3 | In addition to its relationship with marking, doubling has been linked to leísmo, the use of dative clitic le/s for the accusative in different varieties of Spanish and in many parts of Latin America (Fernández-Ordóñez 1999; Gómez Seibane 2012). From a diachronic point of view, the relation is inverse; that is, the greater the presence of leísmo, the lesser the tendency to double (Melis and Flores 2009). In current colloquial speech, the relationship is indirect: the greater the number of features encoded by le/s, the more constraints underlie doubling (Navarro and Neuhaus 2016). For a review of the relation between leísmo and doubling in peninsular Spanish, see Gómez Seibane (2021a). | ||||||||

| 4 | According to Givón (1976), topicality is a product of the two main features: referential importance and referential continuity (accessibility). Tendencies for topics: Pronouns > Full NP. Agent > Benefactive > Dative > Accusative. Definite > Indefinite. | ||||||||

| 5 | For similar findings, see Aranovich (2016). | ||||||||

| 6 | Currently, this corpus is under construction and available only in partial form. All recordings will be open source as of June 2024. https://espanolcontacto.fe.uam.es/wordpress/ (accesed on 20 May 2023). | ||||||||

| 7 | In the case of Spanish in contact with Basque, the towns are Laudio/Llodio (L), Valdegovía/Gaubea (V), Vitoria-Gasteiz (VG), Gernika-Lumo (GL), Bilbao/Bilbo (B), Donostia/San Sebastián (D), Mendaro (M), and Pamplona/Iruña (P). In Asturias, these are Gijón/Xixón (G), Oviedo/Uviéu (O), La Pola (LP), Grado/Grau (G), and Lieres (L). The texts in the parentheses indicate the abbreviations used in the corresponding example. | ||||||||

| 8 | The references are (SC) 11_040, 11_052, 12_020, 12_027, 13_012, 21_039, 22_024, 23_017, 32_032, and 33_007. The texts in the parentheses indicate the abbreviations used in the corresponding example. | ||||||||

| 9 | https://preseea.uah.es/ (accesed on 28 May 2023). | ||||||||

| 10 | The references for the interviews in Santander are (SA) 11_037, 12_020, 13_002, 12_022, 22_028, 31_051, 33_014, 31_054, 21_045, and 32_036; for Alcalá de Henares, they are (AH) 11_037, 12_019, 13_001, 21_043, 22_025, 23_007, 31_050, 11_041, 13_005, 21_047, and 22_028; for Madrid, they are (M) 12_007, 12_010, 23_034, and 11_004; and, for Málaga, they are (MA) 11_115, 12_710, 12_712, 13_065, 21_734, 22_731, 23_719, and 32_727. The texts in the parentheses indicate the abbreviations used in the corresponding example. | ||||||||

| 11 | The rest of the cases missing in the total of 215 (that is, 71) are cases in which doubling does not occur; or, if it occurs, it happens with the dative clitic se, which does not vary in terms of number. The following are two illustrative examples of doubling of singular (i) and plural (ii) IO:

| ||||||||

| 12 | For CorpusC, non-agreeing, doubling clitics is 27.5% (19/69), while for CorpusM, it is 25.3% (19/75). Of note is the frequency of le with plural referents in Santiago de Compostela (35.4% (11/31)), a recently analysed phenomenon (Sanromán Vilas 2021). Given that in Galician the dative lle is the only form for singular and plural, it has been proposed that language contact has been an accelerator of the grammaticalisation of the clitic in the Galician Spanish variety. This phenomenon is also notable in the Basque region (31.8% (7/22)). Additionally, the tendency to aspirate the sibilant in the syllabic coda position could explain the frequency of non-agreeing doubling clitics in Madrid (42.8% (9/21)). |

References

- Acedo-Matellán, Víctor, Jaume Mateu Fontanals, and Anna Pineda Cirera. 2022. Argument Structure and Argument Realization. In The Cambridge Handbook of Romance Languages. Edited by Adam Ledgeway and Martin Maiden. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 507–18. [Google Scholar]

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2007. Grammars in contact: A cross-linguistic perspective. In Grammars in Contact: A Cross-Linguistic Typology. Edited by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and Robert M. W. Dixon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Aranovich, Raúl. 2016. A partitioned chi-square analysis of variation in Spanish clitic doubling. The case of dar ‘give’. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 23: 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloro, Valeria A. 2015. To the Right of the Verb. An Investigation of Clitic Doubling and Right Dislocation in Three Spanish Dialects. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Berro, Ane, Fernández Beatriz, and Jon Ortiz de Urbina, eds. 2019. Basque and Romance. Aligning Grammars. Leiden/Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Brucart, Josep Maria. 1999. La estructura del sintagma nominal: Las oraciones de relativo. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, vol. 1, pp. 395–522. [Google Scholar]

- Cabré, Teresa, and Antonio Fábregas. 2020. Ways of being a dative across Romance varieties. In Dative Constructions in Romance and Beyond. Edited by Anna Pineda and Jaume Mateu. Berlin: Language Science Press, pp. 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafe, Wallace. 1987. Cognitive constrainst on information flow. In Coherence and Grounding in Discourse. Edited by Russell S. Tomlin. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 22–51. [Google Scholar]

- Company, Concepción. 2003. Transitivity and grammaticalization of object. The struggle of direct and indirect object in Spanish. In Romance Objects. Transitivity in Romance Languages. Edited by Giuliana Fiorentino. Berlín/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 217–60. [Google Scholar]

- Company, Concepción. 2012. Constelación de cambios en torno a la categoría objeto indirecto en el español del siglo XVIII. Cuadernos Dieciochistas 13: 147–73. [Google Scholar]

- Comrie, Bernard. 1989. Language Universals and Linguistic Typology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- David, Oana A. 2014. Subjectification in the development of Clitic Doubling: A Diachronic study of Romanian and Spanish. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. Edited by Herman Leung, Zachary O’Hagan, Sarah Bakst, Auburn Lutzross and Jonathan Marker. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society, pp. 42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, Kendra, Scott Schwenter, and Mark Hoff. 2021. The Double’s in the Details: Postposed IOs in Spanish with(out) Corresponding Clitics. Paper presented at New Ways of Analyzing Variation 49, Austin, TX, USA, October 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dubert, Francisco, and Charlotte Galves. 2016. Galician and Portuguese. In The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages. Edited by Adam Ledgeway and Martin Maiden. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 411–46. [Google Scholar]

- Etxepare, Ricardo. 2003. Valency and argument structure in the Basque verb. In A Grammar of Basque. Edited by José I. Hualde and Jon Ortiz de Urbina. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, pp. 363–426. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ordóñez, Inés. 1999. Leísmo, laísmo y loísmo. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, vol. 1, pp. 1317–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Soriano, Olga. 1999. El pronombre personal. Formas y distribuciones. Pronombres átonos y tónicos. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, vol. 1, pp. 1209–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Soriano, Olga. 2015. Clíticos. In Enciclopedia de Lingüística Hispánica. Edited by Javier Gutiérrez-Rexach. London: Routledge, vol. 1, pp. 423–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Susann, and Esther Rinke. 2013. Explaining the variability of clitic doubling cross Romance: A diachronic account. Linguistische Berichte 236: 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Susann, Mario Navarro, and Jorge Vega Vilanova. 2019. The clitic doubling parameter: Development and distribution of a cyclic change. In Cycles in Language Change. Edited by Miriam Bouzouita, Anne Breitbarth and Lieven Danckaert. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 52–70. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Marcela, and Chantal Melis. 2004. La variación diatópica en el uso del objeto indirecto duplicado. Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica 52: 329–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, Cristoph, and Esther Rinke. 2010. Information packaging and the rise of clitic doubling in the history of Spanish. In Diachronic Studies on Information Structure. Language Acquisition and Change. Edited by Gisella Ferraresi and Rosemarie Lühr. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, Ester. 2020. La Duplicación del Complemento Indirecto: Análisis de la Frecuencia de Duplicación en Contextos Optativos en la Provincia de Salamanca. Master’s dissertation, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- García Salido, Marcos, and Victoria Vázquez Rozas. 2012. Los corpus diacrónicos como instrumento para el estudio del origen y distribución de la concordancia de objeto en español. Scriptum Digital: Revista de Corpus Diacrònics i Edició Digital en Llengües Iberoromàniques 1: 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Givón, Talmy. 1976. Topic, pronoun and grammatical agreement. In Subject and Topic. Edited by Charles N. Li. Nueva York: Academic Press, pp. 151–85. [Google Scholar]

- Givón, Talmy. 2001. Syntax. An Introduction. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Seibane, Sara. 2012. Los Pronombres Átonos (le, la, lo) en el Español. Madrid: Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Seibane, Sara. 2020. Patrones de convergencia en lenguas tipológicamente no relacionadas: Lengua vasca y castellano. In Variedades Lingüísticas en Contacto na Península Ibérica. Edited by Francisco Dubert, Vítor Míguez and Xulio Sousa. Santiago de Compostela: Instituto da Lingua Galega, pp. 101–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Seibane, Sara. 2021a. Leísmo y duplicación de objeto directo en tres variedades de español peninsular. In Variedades del Español en Contacto con Otras Lenguas: Metodologías, Protocolos y Modelos de Análisis. Edited by Élodie Blestel and Azucena Palacios. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Seibane, Sara. 2021b. Animación y contacto lingüístico en la duplicación de objeto directo. In Dinámicas Lingüísticas de las Situaciones de Contacto. Edited by Azucena Palacios and María Sánchez Paraíso. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Seibane, Sara. 2021c. Exploring historical linguistic convergence between Basque and Spanish. In Convergence and Divergence in Ibero-Romance across Contact Situations and Beyond. Edited by Miriam Bouzouita, Renata Enghels and Clara Vanderschueren. Amsterdam: De Gruyter, pp. 55–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Seibane, Sara, and Georgina Alvarez Morera. 2022. El marcado diferencial de objeto en el español del siglo XIX en Cataluña: Registro y contacto de lenguas. Revista de Filología Española 102: 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta Flores, Norohella. 2005. Gramaticalización y concordancia objetiva en el español: Despronominalización del clítico dativo plural. Verba 32: 165–90. [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti, Manuel. 1999. El artículo. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa Calpe, vol. 1, pp. 787–890. [Google Scholar]