¿(Está/Es) Difícil?: Variable Use of Ser and Estar by Heritage Learners of Spanish

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Spanish Copula

2.1. Linguistic Factors Conditioning Copula ()Variation

2.2. Extralinguistic Factors Conditioning Copula Variation

3. Heritage Learner Characteristics

3.1. Copulas and Heritage Learners

3.2. Research Questions

- Do English L1 Spanish learners, non-English L1 Spanish learners, and heritage Spanish learners differ in their use of the copula verbs ser and estar?

- 2.

- To what extent do the linguistic and extralinguistic factors identified for monolingual speakers of Spanish apply to the aforementioned groups of learners?

4. Methodology

4.1. Dependent and Independent Variables

4.2. Data Analysis

5. Results

Understanding the Logistic Trends

6. Discussion

6.1. RQ1: Do English L1 Spanish Learners, Non-English L1 Spanish Learners, and Heritage Spanish Learners Differ in Their Use of the Copular verbs Ser and Estar?

6.2. RQ2: To What Extent Do Linguistic and Extralinguistic Factors Identified for Monolingual Speakers of Spanish Apply to Groups of Learners?

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A similar phenomenon is referred to as Differential Acquisition by Kupisch and Rothman (2016) and described by Fairclough (2005) as Second Dialect Acquisition (SDA). |

References

- Aguilar-Sánchez, Jorge. 2009. Syntactic Variation: The Case of Copula Choice in Limón, Costa Rica. Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Sánchez, Jorge. 2012. Formal Instruction and Language Contact in Language Variation: The Case of ser and estar + Adjective in the Spanishes of Limón, Costa Rica. In Selected Proceedings of the 14th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Kimberly Geeslin and Manuel Díaz-Campos. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Sánchez, Jorge. 2017. Research Design Issues and Syntactic Variation: Spanish Copula Choice in Limón, Costa Rica. Balti: Lambert Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Batllori, Montserrat, and Francesc Roca. 2011. Grammaticalization of ser and estar in Romance. In Grammatical Change: Origins, Nature, Outcomes. Edited by Dianne Jonas, John Whitman and Andrew Garrett. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Batllori, Montserrat, Francesc Roca, and Elena Castillo. 2009. Relation between Changes: The Location and Possessive Grammaticalization Path in Spanish. In Diachronic Linguistics. Edited by Joan Rafel Cufí. Girona: Universitat de Girona Publication Services, pp. 443–93. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Esther, and Mayra Cortés-Torres. 2012. Syntactic and Pragmatic Usage of the [estar + Adjective] Construction in Puerto Rican Spanish: ¡Está brutal! In Selected Proceedings of the 14th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Kimberly Geeslin and Manuel Díaz-Campos. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings, pp. 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, José. 2012. ‘Ser’ and ‘estar’: Individual/stage level predicates or aspect? In The Blackwell Handbook of Hispanic Linguistics. Edited by José Ignacio Hualde, Antxon Olarrea and Erin O’Rourke. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 453–76. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, Joseph Clancy. 1988. The semantics and pragmatics of the Spanish <COPULA + ADJECTIVE> construction. Linguistics 26: 779–822. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, Joseph Clancy. 2006. Ser-estar in the Predicate Adjective Construction. In Functional Approaches to Spanish Syntax. Edited by Joseph Clancy Clements and Jiyoung Yoon. Basingstoke: Palgrave-McMillan, pp. 161–202. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Torres, Mayra. 2004. ¿Ser o estar? La variación lingüística y social de estar más adjetivo en el español de Cuernavaca, México. Hispania 87: 788–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro, and Rocío Pérez-Tattam. 2016. Grammatical gender selection and phrasal word order in child heritage Spanish: A feature reassembly approach. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19: 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro, Nancy Rsaeyes, and Eduardo Lustres. 2020. Copulas ser and estar production in child and adult heritage speakers of Spanish. Lingua 249: 102978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Sam, and Kenji Sagae. 2022. The UC Davis Corpus of Written Spanish, L2 and Heritage Speakers. GitHub. Available online: https://github.com/ucdaviscl/cowsl2h (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- de Jonge, Bob. 1993. (Dis)continuity in language change: Ser and estar + age in Latin-American Spanish. In Linguistics in the Netherlands [Linguistics in the Netherlands 10]. Edited by Frank Drijkoningen and Kees Hengeveld. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Campos, Manuel, and Kimberly Geeslin. 2011. Copula use in the Spanish of Venezuela: Is the pattern indicative of stable variation or an ongoing change? Spanish in Context 8: 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Campos, Manuel, Molly Cole, and Matthew Pollock. in press. Sociolinguistic approaches to bilingual phonetics and phonology. In The Cambridge Handbook of Bilingual Phonetics and Phonology. Edited by Mark Amengual. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Díaz-Campos, Manuel, Iraida Galarza, and Gibran Delgado. 2017. The sociolinguistic profile of ser and estar in Cuban Spanish: An analysis of oral speech. In Cuban Spanish Dialectology: Variation, Contact, and Change. Edited by Alejandro Cuza. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 135–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ducar, Cynthia. 2012. SHL learners’ attitudes and motivations: Reconciling opposing forces. In Spanish as a heritage language in the United States. Edited by Sara M. Beaudrie and Marta Fairclough. Georgetown: Georgetown University Press, pp. 161–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Marta. 2005. Spanish and Heritage Language Education in the United States: Struggling with Hypotheticals. Madrid/Frankfurt: Iberoamericana/Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, Kimberly L. 2003. A Comparison of Copula Choice in Advanced and Native Spanish. Language Learning 53: 703–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeslin, Kimberly L. 2005. Crossing Disciplinary Boundaries to Improve the Analysis of Second Language Data: A Study of Copula Choice with Adjectives in Spanish. Munich: LINCOM Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, Kimberly L., and Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes. 2006. The second language acquisition of variable structures in Spanish by Portuguese speakers. Language Learning 56: 53–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeslin, Kimberly L., and Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes. 2008. Variation in contemporary Spanish: Linguistic predictors of estar in four cases of language contact. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 11: 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gili Gaya, Samuel. 1961. Nociones de Gramática Histórica Española. Barcelona: Compendios de Divulgación Filológica. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Manuel J. 1992. The Extension of Estar: A linguistic change in progress in the Spanish of Morelia, Mexico. Hispanic Linguistics 5: 109–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Manuel J. 1994. Simplification, Transfer and Convergence in Chicano Spanish. Bilingual Review/La Revista Bilingüe 19: 111–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen, Federico. 1913. Gramática Histórica de la Lengua Castellana. Halle: Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Isasa, Ane Isasa. 2014. Ser and Estar Variation in the Spanish of the Basque Country [Conference Presentation]. Urbana-Champaign: Illinois Language and Linguistics Society 6. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Daniel Ezra. 2009. Getting off the GoldVarb standard: Introducing Rbrul for mixed-effects variable rule analysis. Language and Linguistics Compass 3: 359–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Daniel Ezra. 2014. Progress in Regression: Why Natural Language Data Calls For Mixed-Effects Models. Daniel Ezra Johnson. Available online: http://www.danielezrajohnson.com/ (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Juárez-Cummings, Elizabeth. 2014. Tendencias de uso de ‘Ser’ y ‘Estar’ en la Ciudad de México. IULC Working Papers 14: 120–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwit, Matthew, and Kimberly L. Geeslin. 2020. Sociolinguistic competence and interpreting variable structures in a second language: A study of the copula contrast in native and second-language Spanish. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 42: 775–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Rothman Jason. 2016. Interfaces with syntax in language acquisition. In Manual of Grammatical Interfaces in Romance. Edited by Susann Fischer and Christoph Gabriel. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 551–586. [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti, Manuel. 1994. ser y estar: Estado de la cuestión. Barataria 1: 182–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Andrew, and Netta Avineri. 2021. Sociolinguistic Approaches to Heritage Languages. In The Cambridge Handbook of Heritage Languages and Linguistics. Edited by Silvina Montrul and Maria Polinsky. Cambridge: CUP, pp. 423–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Andrew. 2012. Key Concepts for Theorizing Spanish as a Heritage Language. In Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States. Edited by Sara M. Beaudrie and Marta Fairclough. Georgetown: Georgetown University Press, pp. 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Marco, Cristina, and Rafael Marín. 2015. Origins and development of adjectival passives in Spanish A corpus study. In New Perspectives on the Study of Ser and Estar. Edited by Isabel Pérez-Jiménez, Manuel Leonetti and Silvia Gumiel-Molina. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 239–66. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2008. Incomplete Acquisition in Bilingualism. Re-Examining the Age Factor. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2016. The Acquisition of Heritage Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ortíz López, Luis A. 2000. Extensión de estar en contextos de ser en el español de Puerto Rico: ¿evolución interna o contacto de lenguas? Boletín de la Academia Puertorriqueña de la Lengua Española, 98–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Matthew. 2020. Did you say peso or beso?: The perception of prevoicing by L2 Spanish learners. In Variation and Evolution: Aspects of Language Contact and Contrast Across the Spanish-Speaking World [IHLL 29]. Edited by Sandro Sessarego, Juan J. Colomina-Almiñana and Adrián Rodríguez-Riccelli. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, pp. 127–61. [Google Scholar]

- Potowski, Kim. 2012. Identity and Heritage Learners: Moving Beyond Essentializations. In Spanish as a heritage language in the United States. Edited by Sara M. Beaudrie and Marta Fairclough. Georgetown: Georgetown University Press, pp. 179–99. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Michael T., and Liliana Sánchez. 2013. What’s so incomplete about incomplete acquisition? A prolegomenon to modeling heritage language grammars. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3: 478–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen, and Simona Montanari. 2008. The acquisition of ser, estar (and be) by a Spanish-English bilingual child: The early stages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 11: 341–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1986. Bilingualism and language change: The Extension of estar in Los Angeles Spanish. Language 62: 587–608. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1994. Language Contact and Change: Spanish in Los Angeles. [Oxford studies in language contact]. Oxford: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 2014. Bilingual Language Acquisition: Spanish and English in the First Six Years. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali A. 2012. Variationist Sociolinguistics: Change, Observation, Interpretation. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 2001. Heritage languages students: Profiles and possibilities. In Heritage Languages in America: Preserving a National Resource. Edited by Joy Kreeft Peyton, Donald A. Ranard and Scott Mcginnis. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics/Delta Systems, pp. 37–77. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Aaron, Sam Davidson, Paloma Fernández-Mira, Agustina Carando, Kenji Sagae, and Claudia Sánchez-Gutiérrez. 2020. COWS-L2H: A corpus of Spanish learner writing. Research in Corpus Linguistics 8: 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants | Essays | Words | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learner group | # | % | # | % | # | % |

| Heritage learners | 346 | 18.3% | 858 | 16.9% | 242,000 | 18.8% |

| International learners with L2 English | 361 | 19.1% | 932 | 18.4% | 218,000 | 16.9% |

| L1 English learners of L2 Spanish | 1186 | 62.7% | 3272 | 64.6% | 829,000 | 64.3% |

| Total | 1893 | 5062 | 1,289,000 | |||

| Learner L1 | # | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mandarin | 172 | 47.6% |

| Vietnamese | 43 | 11.9% |

| Arabic | 15 | 4.2% |

| Hindi | 15 | 4.2% |

| Cantonese | 11 | 3.0% |

| Farsi | 11 | 3.0% |

| Japanese | 11 | 3.0% |

| Punjabi | 11 | 3.0% |

| Gujarati | 10 | 2.8% |

| Hmong | 10 | 2.8% |

| Korean | 10 | 2.8% |

| Other languages * | 42 | 11.6% |

| Total | 361 |

| Factor | Direction of Effect | Investigation Providing Support |

|---|---|---|

| Adjective class | Mental and physical state → estar Observable traits → ser Status → ser | Silva-Corvalán (1986); Gutiérrez (1992, 1994); Díaz-Campos and Geeslin (2011); Juárez-Cummings (2014) |

| Experience with the referent | Indirect → ser Ongoing → ser Immediate → estar | Brown and Cortés-Torres (2012); Díaz-Campos and Geeslin (2011); Geeslin and Guijarro-Fuentes (2006, 2008) |

| Frame of reference | [- comparison] → ser [+ comparison] → estar | Brown and Cortés-Torres (2012); Díaz-Campos and Geeslin (2011); Gutiérrez (1994); Silva-Corvalán (1986) |

| Age | Puerto Rico 20–29 y/o → estar Mexico 35–44 y/o → estar Venezuela 46+ → estar | Brown and Cortés-Torres (2012); Díaz-Campos and Geeslin (2011); Juárez-Cummings (2014) |

| Gender | Costa Rica Women → estar Puerto Rico Men → estar | Aguilar-Sánchez (2009); Ortíz López (2000) |

| L1 | Heritage speakers → estar L2 learners → ser | Silva-Corvalán (1986, 1994, 2014) |

| Study abroad experience | Heritage learners interact and benefit more if abroad. Language learners → more native-like | Potowski (2012); Pollock (2020) |

| Self-identification of proficiency | Heritage speakers at lower proficiency levels → comparable to intermediate/advanced L2 learners | Lynch (2012) |

| Variable | Factor | Logodds | Tokens | % Estar | Factor Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resultant State (p < 0.001) | |||||

| +Resultant | 1.521 | 228 | 81.1% | 0.821 | |

| −Resultant | −1.521 | 7857 | 23.8% | 0.179 | |

| range | 64.2 | ||||

| Frame of Reference (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Individual comparison | 0.988 | 2560 | 53.1% | 0.729 | |

| Class Comparison | −0.988 | 5525 | 12.7% | 0.271 | |

| range | 45.8 | ||||

| Study Abroad (p = 0.011) | |||||

| Yes | 0.261 | 542 | 29.2% | 0.565 | |

| No | −0.261 | 7543 | 25.2% | 0.435 | |

| range | 13 | ||||

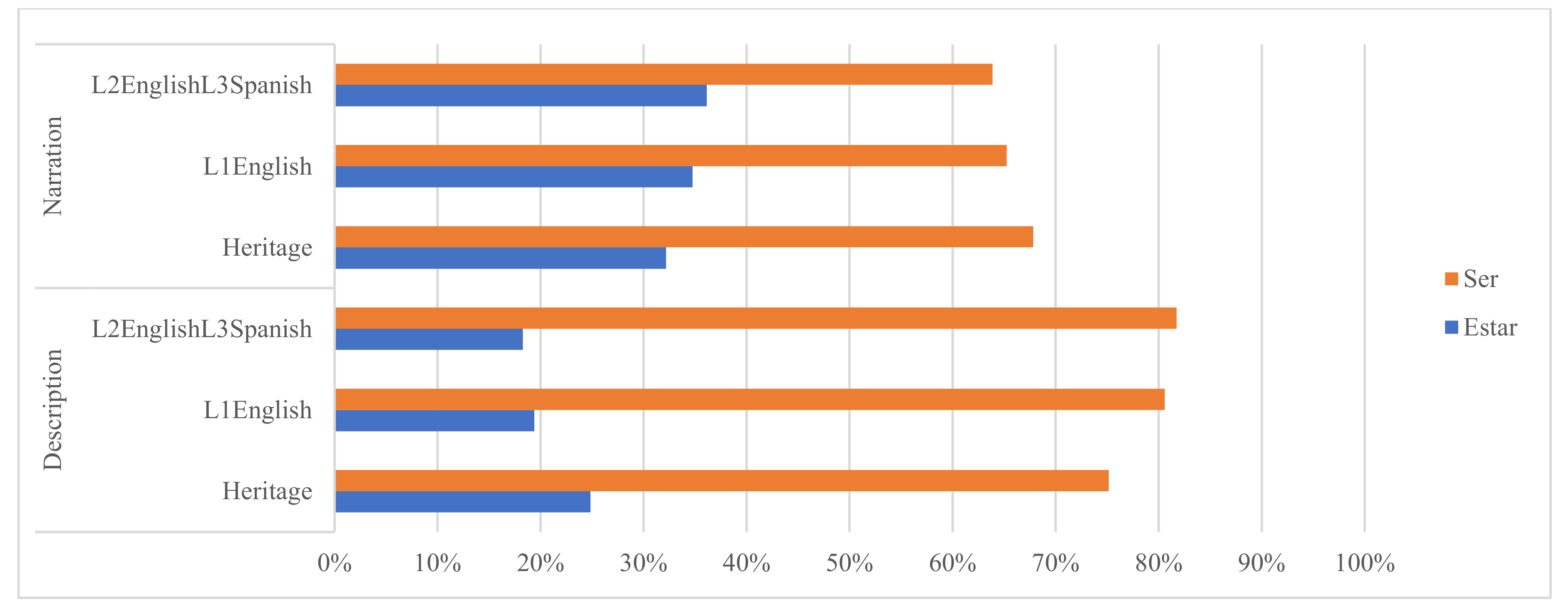

| Essay Prompt (p = 0.008) | |||||

| Narrative | 0.15 | 3188 | 34.8% | 0.537 | |

| Description | −0.15 | 4897 | 19.4% | 0.463 | |

| range | 7.4 | ||||

| Age (p = 0.046) | |||||

| continuous | logodds | ||||

| +1 | −0.039 | ||||

| Variable | Factor | Logodds | Tokens | % Estar | Factor Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resultant State (p < 0.001) | |||||

| +Resultant | 3 | 55 | 80.0% | 0.953 | |

| −Resultant | −3 | 2111 | 23.9% | 0.047 | |

| range | 90.6 | ||||

| Frame of Reference (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Individual comparison | 1.166 | 621 | 59.6% | 0.762 | |

| Class Comparison | −1.166 | 1545 | 11.6% | 0.238 | |

| range | 52.4 | ||||

| Adjective Class (p = 0.027) | |||||

| Mental | 1.43 | 1251 | 35.7% | 0.807 | |

| Status | −0.705 | 146 | 16.4% | 0.331 | |

| Observable Traits | −0.725 | 769 | 10.3% | 0.326 | |

| range | 48.1 | ||||

| Variable | Factor | Logodds | Tokens | % Estar | Factor Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resultant State (p < 0.001) | |||||

| +Resultant | 1.801 | 283 | 80.9% | 0.858 | |

| −Resultant | −1.801 | 9968 | 23.9% | 0.142 | |

| range | 71.6 | ||||

| Frame of Reference (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Individual comparison | 1.003 | 3181 | 54.4% | 0.732 | |

| Class Comparison | −1.003 | 7070 | 12.4% | 0.268 | |

| range | 46.4 | ||||

| Adjective Class (p = 0.029) | |||||

| Mental | 0.558 | 6033 | 33.2% | 0.636 | |

| Status | 0.133 | 687 | 22.0% | 0.533 | |

| Observable Traits | −0.692 | 3531 | 12.8% | 0.334 | |

| range | 30.2 | ||||

| Study Abroad (p = 0.004) | |||||

| Yes | 0.277 | 593 | 29.5% | 0.569 | |

| No | −0.277 | 9658 | 25.2% | 0.431 | |

| range | 13.8 | ||||

| Essay Prompt (p = 0.004) | |||||

| Narrative | 0.143 | 4046 | 35.0% | 0.536 | |

| Description | −0.143 | 6205 | 19.2% | 0.464 | |

| range | 7.2 | ||||

| Variable | Factor | Logodds | Tokens | % Estar | Factor Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frame of Reference (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Individual comparison | 0.694 | 357 | 42.0% | 0.667 | |

| Class Comparison | −0.694 | 554 | 19.5% | 0.333 | |

| range | 33.4 | ||||

| Course Level (p = 0.025) | |||||

| continuous | logodds | ||||

| +1 | −0.481 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wheeler, J.; Pollock, M.; Díaz-Campos, M. ¿(Está/Es) Difícil?: Variable Use of Ser and Estar by Heritage Learners of Spanish. Languages 2023, 8, 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040271

Wheeler J, Pollock M, Díaz-Campos M. ¿(Está/Es) Difícil?: Variable Use of Ser and Estar by Heritage Learners of Spanish. Languages. 2023; 8(4):271. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040271

Chicago/Turabian StyleWheeler, Jamelyn, Matthew Pollock, and Manuel Díaz-Campos. 2023. "¿(Está/Es) Difícil?: Variable Use of Ser and Estar by Heritage Learners of Spanish" Languages 8, no. 4: 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040271

APA StyleWheeler, J., Pollock, M., & Díaz-Campos, M. (2023). ¿(Está/Es) Difícil?: Variable Use of Ser and Estar by Heritage Learners of Spanish. Languages, 8(4), 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040271