Abstract

The acquisition of deictic verbs is a significant milestone in language development. This complex process requires an understanding of the interplay between the personal pronouns “I/you” and deictic verbs. Although demonstrating the cognitive processes associated with deictic shifting through data is valuable, research issues regarding data accuracy and the spatial arrangement of the self and other remain unresolved. This pilot study aimed to quantitatively measure the body movements of Japanese-speaking children during their utterances of “come/go”. Twelve typically developing children aged 6–7 participated in this study. Multiple scenarios were set up where the researcher presented phrases using “come/go” with deictic gestures, such as moving one’s upper body forward or backward, and the participant replied with “come/go”. When performing a role, the researcher sat face-to-face or side-by-side with the participant, depending on the type of question–response. It is possible that there is a learning process whereby verbal responses using “come/go” align with corresponding body movements in the specific question type. This process is deeply involved in the development of perspective-taking abilities. Future research with relatively large samples and cross-cultural comparisons is warranted to deepen the understanding of this linguistic acquisition process and its implications.

1. Introduction

The mastery of the deictic verbs “come/go” demands an understanding of their superficial meanings and a comprehension of the interplay between the personal pronouns “I/you” and deictic verbs; this process is referred to as “deictic shifting” (Dale and Crain-Thoreson 1993). According to Zubin and Hewitt (1995), in the process of “deictic shifting”, within narratives, the narrator first provides an introduction from outside the frame of the story, such as “Once upon a time, there was an old man…” At this stage, the deictic center is placed in the actual speech situation, where the narrator is “I”, the listener is “you”, the place of narration is “here”, and the time of narration is “then”. Subsequently, the narrator can move the deictic center into the story by “decoupling the linguistic marking of deixis from the speech situation, and reorienting it to the major characters, the locations, and a fictive present time of the story world itself” (Zubin and Hewitt 1995). This process causes the narrator’s presence to fade into the background, allowing the listener to become more deeply immersed in the story world. The following is an example of the transition from (a) a descriptive sentence to (b) an expression closer to the character’s perspective:

- (a)

- The old man wondered about the voice he heard coming from the forest.

- (b)

- I hear something from the forest. What could that voice be?

In conversations, both the speaker and listener continuously re-map their changing roles and reciprocal relationships (Mizuno et al. 2011). Subsequently, the speaker utters the appropriate verb in response to the selected personal pronoun. In this study, we addressed the use of “come (来る)” and “go (行く)” in the Japanese language. Hereinafter, the usage of “come/go” in English sentences reflects Japanese linguistic conventions. As an example of deictic shifting in Japanese conversations, consider the following exchange, in which Kai invites Mio to watch a movie. Mio first perceives the movement from Kai’s perspective, e.g., “From Kai’s viewpoint, he would think, ’Mio comes to my house’”. Subsequently, Mio shifts her perspective to “From my viewpoint, I go to Kai’s house”, and responds using “go”.

- Kai:

- Mio:

Additionally, the key characteristic of deictic verbs is the presence or absence of subjects such as “I/you” in daily conversation. The subject is explicitly included in English, whereas subjects are omitted in Japanese conversation unless emphasis is required (Shibamoto 1983):

先週末、本屋に行きました。senshuu.matsu honya ni ik-i-mashi-talast.weekend bookstore to-DAT go-POL-PAST(I) went to the bookstore last weekend.

Selecting a verb according to the subject is a common feature in Japanese and English. However, as shown in the example below, Japanese tends to omit “I” in the responses. In this example, when Jun responds, he must mentally change the subject from “you” to “I”, even though he does not say “I” out loud. He then has to choose the appropriate verb based on this shift in perspective.

- Rei:

- Jun:

Masataka (1998) conducted a cohort study with typically developing (TD) Japanese children. Dialogue tasks using “come/go” were implemented and data were collected twice when the children were in the first grade of elementary school and one year later. The researcher put “come/go” questions to the participants (e.g., “Will you come to play today?”), simultaneously moving their arms toward the center of their body when they said “come”, and outwardly when they said “go”. Subsequently, participants responded using “come/go”. Participants’ verbal expressions and arm or hand movements were analyzed. These movements toward or outward from the body were assessed using footage captured by a video camera positioned above the participant’s head. Consequently, the following three acquisition sequences were suggested: (1) inappropriate use of “come/go” (i.e., using the opposite verb from what is considered appropriate in the given context) and no consistent trend in body movements, (2) inappropriate use of “come/go” and body movements based on actual directions of movement, and (3) appropriate use of “come/go” and body movements based on actual directions.

The gestures in Masataka’s (1998) experiments likely served as deictic gestures, indicating events using parts of the body, such as pointing (McNeill 1992). In other words, the researcher’s indication of movement direction may have facilitated appropriate verbal expressions and body movements in the TD children. Although the aforementioned study made immense contributions in terms of demonstrating the cognitive processes associated with deictic shifting through data, two research issues remained unresolved. First, Masataka (1998) qualitatively analyzed and described body movements as subtle, without quantitatively evaluating this subtlety, thereby raising concerns regarding data accuracy. Second, the conditions regarding spatial relations between the two parties (e.g., face-to-face or side-by-side) were unclear. Considering the relationship between deictic verbs and personal pronouns (Dale and Crain-Thoreson 1993; Mizuno et al. 2011), it is necessary to contemplate the spatial positioning of “I” and “you”.

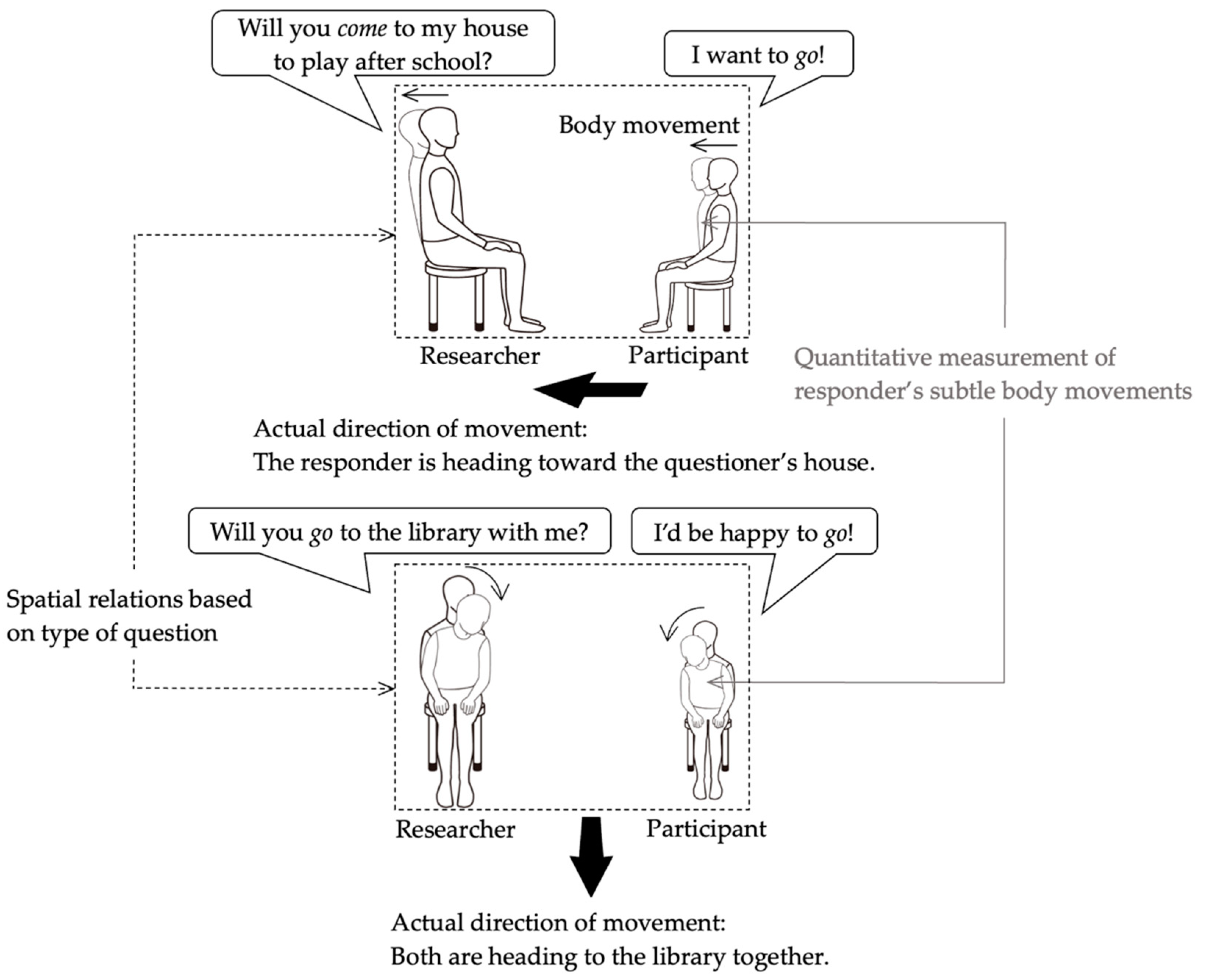

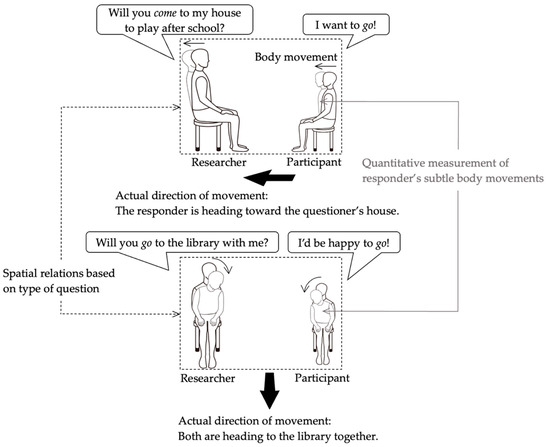

By addressing these research issues, we hypothesized that quantitative data would demonstrate that combining the presentation of deictic gestures with spatial relational conditions would promote appropriate verbal expressions and body movements in TD children (Figure 1). The rationale for this hypothesis is as follows: regarding the first issue of data accuracy, more than 20 years had passed since the publication of Masataka’s (1998) paper at the time the current study was conducted; with the advancement of engineering technologies, research insights using motion capture systems as a measurement and analysis tool for TD children were systematically accumulated over time (for a review, see Reuter and Schindler 2023). Using these systems to quantitatively evaluate body movements during the use of “come/go”, we expected to fill a research gap. In our study, we used upper-body movements as indicators of body movements instead of arm or hand movements (Masataka 1998), for several reasons. Upper-body movements can capture more subtle and potentially unconscious reactions, which may better reflect the natural process of deictic shifting (Mizuno et al. 2011). Additionally, these movements provide a more comprehensive representation of whole-body responses. Subtle body movements, regardless of whether or not they involve large movements such as those of arms or hands, invariably manifest in upper-body movements.

Figure 1.

Solutions to research issues. Note. Body movements were depicted as upper-body movements according to the procedures of this study and were exaggerated to ensure clarity, although in reality, they were slight movements.

Regarding the second issue of spatial relations, we predicted the effects of two parties lining up either face-to-face or side-by-side, depending on the type of question. For example, the Japanese question “Will you come to my house to play after school?” implies that the participant is approaching the researcher. Based on Masataka’s (1998) findings in the experimental setting, where forward movement tends to occur when expressing “go” and backward movement when expressing “come”, the spatial relations and deictic gestures are set up: the two are positioned face-to-face, and the researcher asks, “[while moving the body backward] Will you come…?” This might prompt TD children to move their bodies forward and produce verbal responses using “go”. Similarly, the Japanese question “Will you go to the library with me?” implies that the researcher and the participant are moving in the same direction. The two are positioned side-by-side, and the researcher asks, “[while moving the body forward] Will you go…?” This might prompt TD children to move the body forward and produce verbal responses using “go”.

In this pilot study, we aimed to quantitatively measure TD children’s body movements during their uttering of “come/go”, and to analyze the correlation between verbal responses and body movements based on actual directions. We predicted that TD children would move their bodies slightly backward when uttering “come” and forward when uttering “go”. This prediction stemmed from the idea that body movements often align with spatial concepts in the use of “come/go” (Masataka 1998). Furthermore, we predicted that this tendency would be stronger in responses to the types of questions that require deictic shifting (e.g., “Will you come to my house to play after school?”) than those where such shifting is not required (e.g., “Will you go to the library with me?”). This prediction was based on the increased cognitive load associated with deictic shifting (Mizuno et al. 2011). We hypothesized that this increased cognitive demand might manifest in more pronounced body movements because children navigate the perspective shift. Additionally, given the frequent subject omission in Japanese (Shibamoto 1983), we expected these bodily cues to play a crucial role in conveying perspective, potentially serving as a non-verbal indicator of the speaker’s viewpoint.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited from an elementary school in a rural area of Japan based on the following three criteria: (a) the child’s chronological age was between 6 and 7 years, based on Masataka’s (1998) study; (b) the child had not been diagnosed with neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and had a score of ≤6 in childhood on a shortened version of the Parent-Interview ASD Rating Scale (PARS)–Text Revision (PARS Committee 2013); and (c) the child had a scale score of ≥6 on the Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised ([PVT-R] Ueno et al. 2008). Criteria (b) and (c) aimed to ensure that participants did not have ASD tendencies and had age-appropriate language development. Children with ASD tendencies were excluded from the study as past projects have indicated they have difficulties in learning deictic terms (Asaoka et al. 2019; Lee et al. 1994; Manwaring et al. 2018). Regarding criterion (b), the score of PARS correlates with that of the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (Lord et al. 1994), indicating the convergent validity of PARS (Ito et al. 2012). A PARS childhood score of 7 points or above suggests the presence of ASD. Regarding criterion (c), the PVT-R is the officially standardized scale in Japan for assessing verbal intelligence, and a scaled score of 6 points or above indicates that verbal intelligence is not delayed. The present analysis included data from 12 TD children (six boys and six girls) (see Table 1). Two more children who participated were excluded from the analyses because of a failure to meet the inclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Profiles of all participants and descriptive statistics.

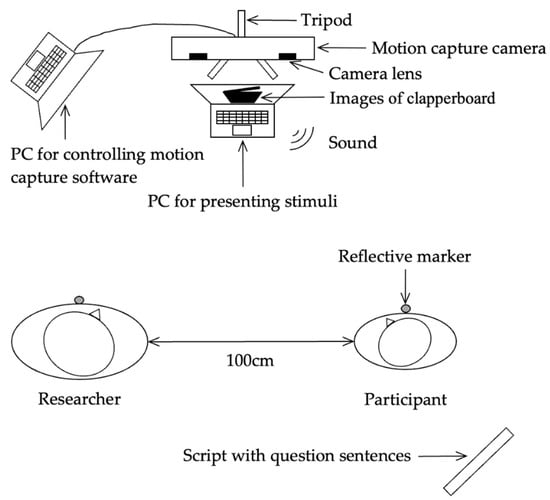

2.2. Setting and Materials

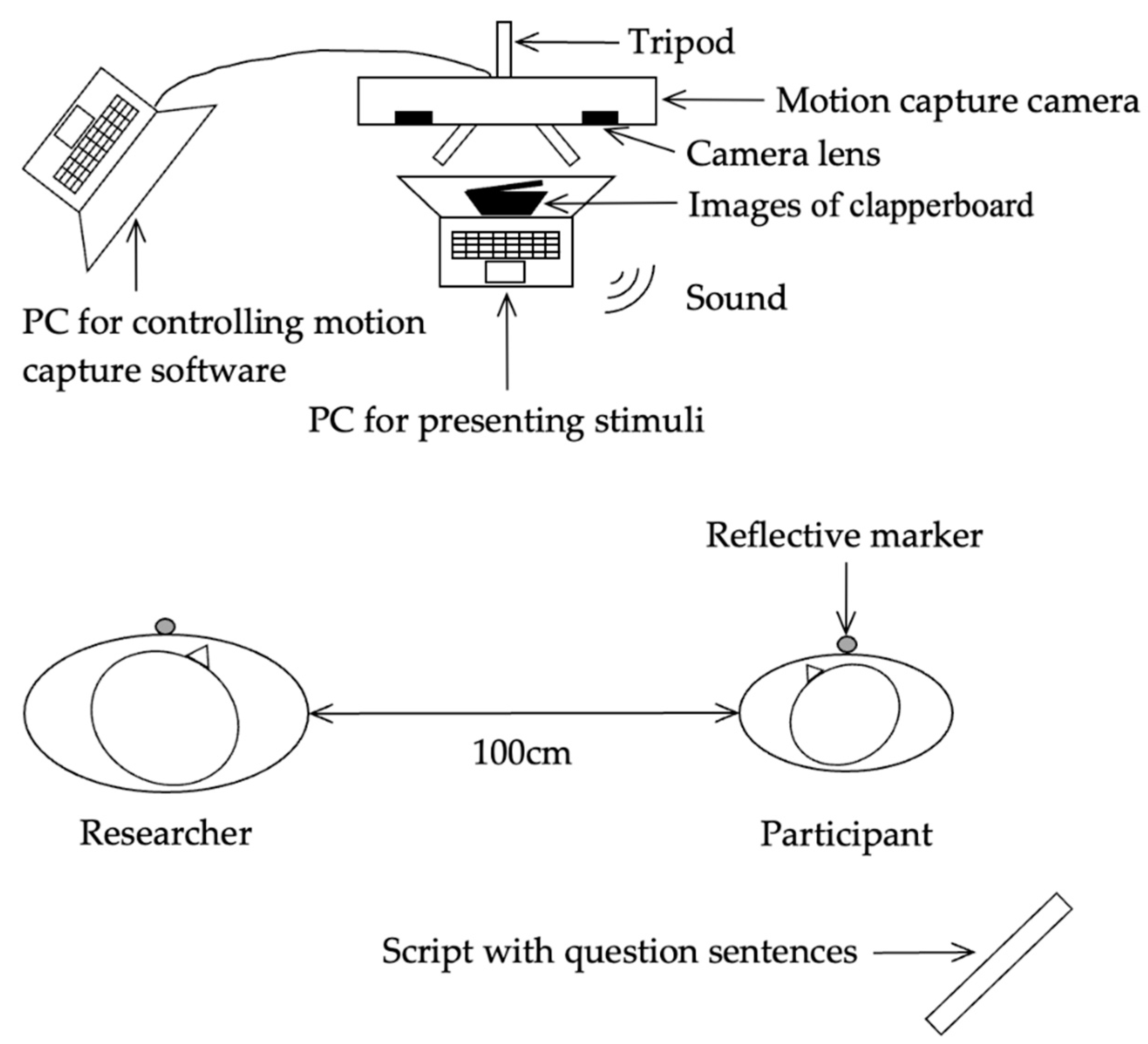

The experiment was conducted with each participant in a quiet room at their elementary school, for approximately 15 min per participant. The first author, serving as the researcher, took on the role of either a child actor or the father of the participating child. This role-playing approach was employed to create realistic social scenarios, such as interactions with a peer or a parent, thus eliciting participants’ natural responses in contexts relevant to the use of deictic verbs. The researcher was seated either face-to-face or side-by-side with the participating child. Chairs without backrests were used so as to not impede body movement. The distance between the researcher and participant was 100 cm. Motion capture, a device used to measure the three-dimensional positional relationships via reflection from infrared rays, was used to analyze the movements of the bodies. One reflective marker was attached to the center of the chest for both the researcher and the participant. A motion capture camera (OptiTrack V120: DUO) fixed to a tripod, a personal computer ([PC] Dell Precision 5530) for controlling motion capture software (Motive 2.3.7), and another PC (Dell Inspiron 5482) for presenting stimuli were placed in front of the researcher and the participant (for an aerial view of the setup, see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Aerial view of the set-up.

In total, 20 sets were randomly extracted from 40 sets of narration and questions containing “come/go” from Asaoka et al. (2021), who used motion capture systems to examine the conditions for the appropriate use of “come/go” in children with ASD. The sets consisted of four types of interrogative questions set out as “question → response”, as follows: “come? → come”, “come? → go”, “go? → go”, and “go? → come” (for all the stimulus sets of each type, see Table 2 and Table A1). The narration and questions were employed in scenarios where two people were talking in the same place and responding with “come/go”. The use of “come/go” in the English questions and examples of responses were derived from the Japanese form. A total of 20 stimulus sets, five of each type, were randomly ordered for each participant. A script with 20 questions was placed out of the participant’s sight (see Figure 2).

Table 2.

Stimulus sets and sample responses in English.

2.3. Procedures

The researcher asked the participant to film a short skit titled, “A diary of the elementary school students”. The researcher also asked them to perform with emotion, but did not instruct them on how to move their body. Subsequently, the participant was instructed to utter a phrase using “come/go” following a phrase uttered by the researcher, such as “When I ask a question, freely say a line using come or go”. Additionally, the researcher provided examples, such as “I want to go!” and “I believe Ken will come”.

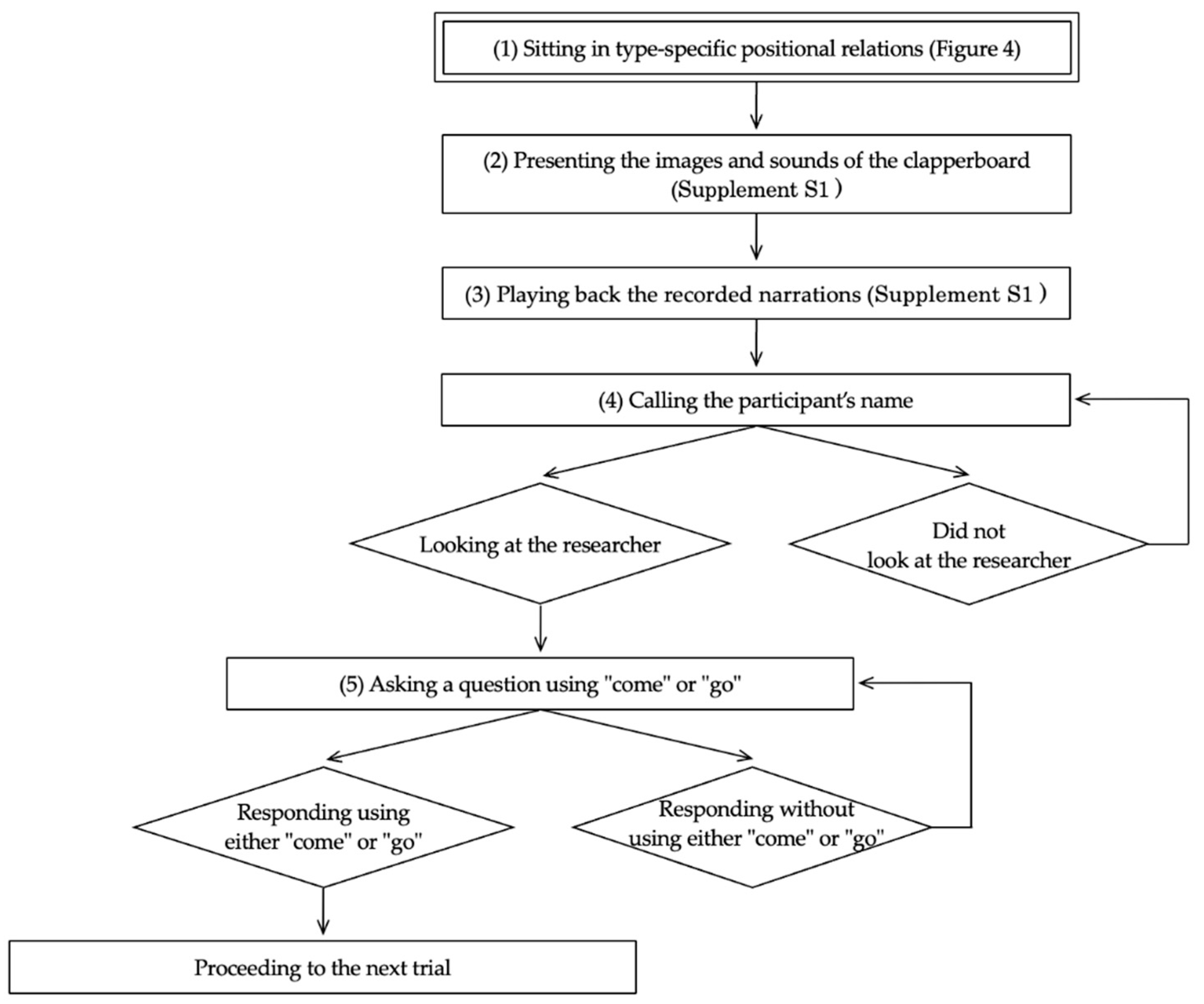

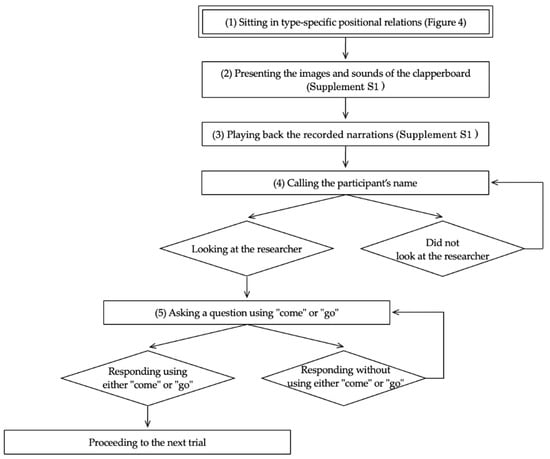

In total, 20 trials were conducted. Each trial followed a sequence of steps as depicted in Figure 3, consisting of (1) sitting in type-specific positional relations, (2) presenting the cues by clapperboard, (3) the narrations, (4) calling the participant’s name, and (5) the questions, in that order. The details of each component are as follows:

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the procedure. Note. Double rectangles indicate actions by both the researcher and participant; rectangles indicate actions by the researcher, and diamonds indicate actions by the participant. The numbers in parentheses correspond to those in the main text.

- (1)

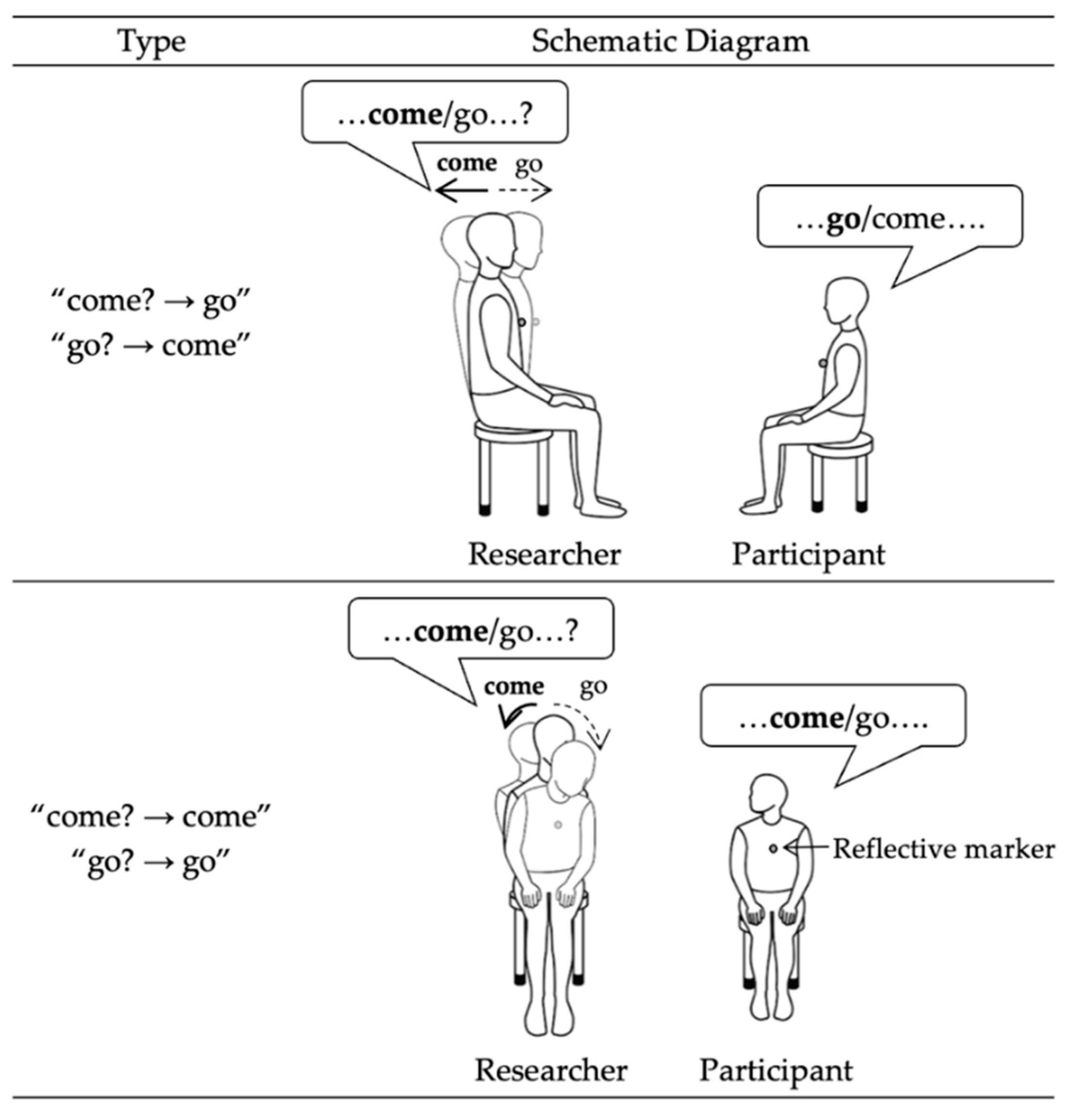

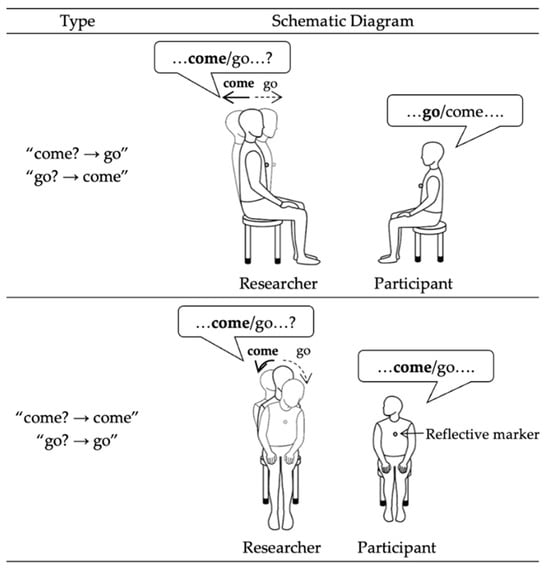

- The researcher and the participant sat side-by-side in the question types of “come? → come” and “go? → go” and sat face-to-face in the question types of “come? → go” and “go? → come”. When sitting side-by-side, as illustrated in the lower section of Figure 4, they turned their faces toward each other and maintained eye contact during interactions;

Figure 4. Verbal expressions and body movements in each position. Note. Bold and fine letters indicate the correspondence between the verbs and movements. The participant’s lines indicate correct responses, whereas the participant’s arrows indicate upper-body movements based on actual directions.

Figure 4. Verbal expressions and body movements in each position. Note. Bold and fine letters indicate the correspondence between the verbs and movements. The participant’s lines indicate correct responses, whereas the participant’s arrows indicate upper-body movements based on actual directions. - (2)

- The researcher presented the images and sounds of the clapperboard via the PC monitor for presenting stimuli;

- (3)

- The researcher played back the recorded narrations via these PC speakers, such as “September 1st is Hiroshi’s (child actor’s name) birthday”. The cue given by the clapperboard in (2) and the sample narration in (3), presented by the PC, are available in Supplement S1. A series of stimulus sets consisting of the starting cue and narration were programmed using Microsoft PowerPoint for Microsoft 365 (Version 16.89.1). The PC for presenting stimuli and a small remote controller (Kokuyo ELA-FP1) were connected wirelessly, and the slides could change when the researcher operated a switch they were holding;

- (4)

- The researcher called the participant’s name, e.g., “Yui”, after which the researcher confirmed whether the participant looked at the researcher before asking the question. In cases where the participant did not look at the researcher, the researcher called their name again;

- (5)

- The researcher immediately asked, “I’m having a birthday party tomorrow. Will you come?” When asking the question, the researcher moved their upper body slightly backward (approximately 5 cm) as they uttered “come”, and stopped moving it at the end of the phrase. When the word “go” was uttered, the researcher moved their upper body slightly forward (see Figure 4). Subsequently, the participant responded with a phrase using “come/go”. If the participant used other verbs or simply responded with “yes/no”, the researcher instructed them to respond using either “come” or “go” and repeated the question.

2.4. Variables and Data Analysis

To examine the association between verbal expressions and body movements, we employed the same three variables utilized by Asaoka et al. (2021).

- (1)

- Number of correct responses (times): The correct response was defined when accurately using the phrase “come” or “go” according to the four types of questions. The number of correct responses was counted for each of the four types of questions.

- (2)

- Number of upper-body movements based on actual directions (times): The participants’ upper-body movements, which were based on the actual directions of movements, were defined as either moving backward in the trials where it was appropriate to express “come”, or moving forward in the trials where it was appropriate to express “go”. Using a voice-processing software (Adobe Audition, build 24.6.0.69), we identified the following time intervals and analyzed the body movements during these times. First, we listened to the recorded voice while observing the waveform to identify the time when the researcher uttered the initial sound /k/ in /kuru/ (“come”) or /i/ in /iku/ (“go”) in Japanese for each trial. Second, we determined when the participant started speaking. To identify this time, we excluded filler words such as “well”, “uh”, “er”, and “um”. Third, we imported into a motion-analysis software (Acuity SKYCOM 3.4.3) data concerning the reflective marker’s trajectories recorded by the motion-capture camera and analyzed participants’ upper-body movements in the anteroposterior direction. The maximum amplitude in the anteroposterior direction was regarded as an upper-body movement. Trials with missing data and the same value of the maximum forward and backward amplitude were excluded from the total number of trials.

- (3)

- Average amount of upper-body movement (mm): The amount of participants’ upper-body movement for each trial was automatically calculated from the data imported into the motion analysis software. The total number was divided by a maximum of 20, excluding trials with missing data, and multiplied by 100 to calculate the average. Data from the researcher’s reflective marker were not included in the analysis. The marker was attached to match the conditions with the participant.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27.0) to calculate means, standard deviations, and Spearman’s correlations between all variables, and to conduct an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparing the number of correct responses among the four types of questions.

3. Results

The participant and overall results are shown in Table 3 and Table 4. Specifically, Table 3 presents individual data for each participant, including the number of correct responses, the number of upper-body movements based on actual directions, and the average amount of upper-body movement for each question type. Table 4 provides group-level statistics, demonstrating means, standard deviations, and correlations between all variables. First, a significant moderate to high correlation (r = 0.62–0.84) was observed among variables related to the number of correct responses and the number of upper-body movements based on actual directions, specifically between 1 and 4 (“1. come? → come” and “4. go? → come”; hereafter indicated by the numbers in Table 3), 3 and 5, and 2 and 6 (Table 4). Contrary to the prediction that the occurrences of appropriate verbal expressions would accompany slight body movements based on actual directions, only the question type “come? → go” was positively correlated (2–6; r = 0.62). All erroneous responses involved saying the line with the opposite verb (e.g., responding “Yeah, I’ll come!” to the question “Will you come to my house today?”). Second, within an average amount of upper-body movement, there were also significant moderate to high correlations between all variables, except for 9–12 (r = 0.59–0.87). This indicates the presence of consistency in the relative magnitude of movement among participants across different types of question–response. In other words, participants who exhibited larger movements in one condition tended to show larger movements in other conditions as well, whereas those who exhibited smaller movements in one condition tended to show smaller movements in others. This pattern highlights individual differences in overall movement tendencies, which were consistent regardless of the specific question–response type. Third, a one-way ANOVA comparison of the number of correct responses revealed a significant difference (F (3, 44) = 18.2, p < 0.001). The results of multiple comparisons using Tukey’s method indicate that the number of correct responses to the question type “come? → go” was significantly lower than that for the other three types of question–response (all p < 0.001). Six participants had no correct responses in this question–response type, representing 50% of all participants (see Table 3). Fourth, there was a negative correlation between the numbers and amounts of movements in the question type “come? → go” (6–10; r = −0.58), which indicates that participants with fewer upper-body movements based on actual directions tended to have a greater amount of movement (see Table 3). For overall response characteristics, the number of times participants responded with a specific subject, such as “I want to go”, was only once for all participants and trials combined. Additionally, there were no instances of clear arm or hand movements, such as beckoning or pointing.

Table 3.

Results for each participant.

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between variables for each variable.

4. Discussion

In this study, we quantitatively measured verbal responses, body movements based on actual directions, and the number of body movements in 6–7-year-old TD children. To this end, we combined the presentation of deictic gestures with spatial relational conditions based on the types of “come/go” questions in Japanese. One of this study’s most significant findings was the suggestion that the alignment of verbal responses for “come/go” and body movements based on actual directions appears only in a specific question type, that is, “come? → go”. This is evidenced by the results, which showed a positive correlation between the number of correct responses and the number of upper-body movements based on actual directions in the “come? → go” question type (r = 0.62, p < 0.05), whereas no such correlations were found in the other three types. Furthermore, the mean number of correct responses for the “come? → go” question type was 1.5 times, while the mean number of correct responses for the other types was 4 or more times. This suggests that the “come? → go” question type was more challenging for 6–7-year-old children as compared to the other types. The thought process may have required the producing of appropriate responses manifested as physical movements. Overall, these findings partially support the hypothesis that combining the presentation of deictic gestures with spatial relational conditions would promote appropriate verbal expressions and body movements. Additionally, these findings partially substantiate the relationship between verbal responses and body movements proposed by Masataka (1998). The difference in results may be owing to the fact that Masataka (1998) measured arm and hand movements, whereas the current study measured upper-body movements. In interpreting the results of the above-mentioned study, it is important to consider that subtle movements might reflect factors unrelated to the current project, such as posture adjustments or idiosyncratic movement patterns. Based on these results, the following paragraphs discuss factors related to the acquisition of deictic verbs, with a focus on spatial perspective-taking—an essential cognitive ability that makes it possible to imagine how objects or scenes appear from various spatial perspectives (He et al. 2022).

To verify the prediction that the co-variation of appropriate verbal responses and body movements based on actual directions would more likely occur in the types of question–response that require deictic shifting (Dale and Crain-Thoreson 1993), we compared the results of the question types “come? → go” and “go? → come”. Notably, the structural environments of these two conditions were similar in terms of frame reuse, and did not require dramatic changes of the structural frame when responding (for details, see Table A1): in the ”come? → go” question type, the verb “come” was presented in its non-inflected form in the question sentence, and the participants could respond simply by using “go”. Similarly, in the “go? → come” question type, all question sentences were in the form of “it-te ii (go-TE good)”, requesting approval, and the participants could reuse the frame “it-te ii” and respond with “ki-te ii yo (come-TE good SFP)”.

In the “come? → go” question type, a positive correlation was observed between verbal responses and body movements based on actual direction. When the researcher asked a question using “you”, the participant mentally shifted the perspective to “I” in order to respond appropriately. In this process, the researcher’s upper-body movements might have prompted the participant to move forward, and the internalized language “I”, often omitted in Japanese, was inferred to be triggered. The cognitive process using which the participant replaced the subject “you” with “I” when questioned by the researcher is thought to involve perspective transformations, which inform the location and/or orientation of one’s perspective, and its existence is suggested (Steggemann et al. 2011; Yu and Zacks 2010; Zacks and Tversky 2005). The forward movements of the participants might indicate evidence of this process. Additionally, the negative correlation between the numbers and amounts of movements in the question type “come? → go” might suggest that TD children are experimentally moving their bodies before establishing the direction of movement. Regarding perspective transformations, as the two parties were seated facing each other in this study, a 180-degree perspective transformation was required. Perspective-taking studies have reported that response times increase, and errors are more likely to occur, as the angle approaches 180 degrees (Kessler and Thomson 2010; Michelon and Zacks 2006). The study on the use of “come/go” also indicated that introducing a condition where the two parties are seated diagonally (at 90 degrees) in the question types “come? → go” and “go? → come” facilitated the occurrence of appropriate verbal responses (Asaoka et al. 2021). The findings of the current study, that the question type “come? → go” was the most difficult to respond to appropriately, support the findings of Michelon and Zacks (2006) and Asaoka et al. (2021). In addition to these factors related to the appropriate use of “come/go”, the experimental tasks in Masataka (1998) and the present study used implicit prompts of others’ body movements instead of explicit verbal prompts from others, such as “I…” Consequently, participants were required to utilize the skill of converting subjects more spontaneously. Thus, owing to the need to spontaneously perform perspective transformations (Elekes et al. 2017; Freundlieb et al. 2016), it was speculated that a correlation between appropriate verbal responses and body movements based on actual directions was less likely.

Subsequently, in the question type “go? → come”, which also requires perspective transformations, the prediction that the same phenomenon observed in the question type “come? → go” would be observed was not supported by this study’s data. Why did the “go? → come” type exhibit higher stability despite having the same language frame as the “come? → go” type and requiring perspective transformations? Focusing on the perspective transformations, in the “come? → go” type, the question with “you” as the assumed subject is presented, and the response requires a shifting of the perspective to “I”. Conversely, in the “go? → come” type, the question with “I” is presented, and the response requires a shifting of the perspective to “you” (see Table 2 and Table A1). To sum up, the direction of transformation differs between “you → I” and “I → you”. In the “come? → go” type, the questioner is asking about the respondent, whereas in the “go? → come” type, the questioner is asking about themselves. In the latter type, the respondent can naturally follow the already presented conversational framework, making the perspective shift more intuitive and easier to understand. As a result, the cognitive load might be reduced, potentially leading to more appropriate responses. Based on these considerations, it can be inferred that the “go? → come” type might be more prone to automatization effects in language learning compared to the “come? → go” type. Segalowitz and Segalowitz (1993) suggested that the increase in processing stability must have been brought about by eliminating specific processes through repetition. The process of body movements might have been omitted, as children who participated in this study had already established patterns of responding to questions through everyday conversations. Similarly, it could be inferred that they had also acquired patterns of question–response in the question types “come? → come” and “go? → go”, where deictic shifting was unnecessary.

In summary, comparing the results of different types of question–response, it was suggested that the mastery of the deictic verbs “come/go” is related to whether appropriate verbal responses are accompanied by body movements based on actual directions. In addition to the different indicators used—arm and hand movements in Masataka (1998) versus upper-body movements in this study—Masataka (1998) did not analyze the types of question–response effects and used video cameras for measurement, which might have led to differences. Moreover, the results indicating differences in the amount of body movement among participants suggest that the movement characteristics might have influenced the results.

A key strength of this study lies in the quantitative evaluation of the developmental characteristics in the use of “come/go”. However, this is a preliminary study, and further caution is required regarding the findings’ generalizability. Future research should consider the following three points: (1) This study should be replicated with a relatively larger number of children. Concerning the evaluation of the developmental characteristics in the use of deictic verbs, further studies should include not only 6–7-year-olds, but also younger and older children. An investigation of whether the correlation between verbal expressions and body movements is observed in all four types of question–response for younger children at the learning stage would be intriguing. Additionally, it is recommended that an evaluation be carried out regarding the prediction that this correlation would not be observed in any question type for older children who have acquired all types. (2) To strengthen the evidence regarding the relationship between the acquisition of deictic verbs and related areas, future research should consider several directions. These include investigating the correlation between deictic verb performance and the use of personal pronouns, examining the relationship between the appropriate use of “come/go” and other deictic verbs such as “give/receive” or “hide/seek”, as well as motion verbs such as “run” or “walk”, comparing the production and comprehension of deictic verbs, and exploring the relationship between performance in perspective-taking tasks and the use of deictic verbs. Regarding the relationship between “come/go” and other verbs, Murofushi (1998) stated that children’s actions and their labels are presented in pairs, and children learn the meaning and usage of words. Extending this idea and the correspondence between the verbal expression of “come/go” and the physical movements of “backward/forward”, slower movements might be observed when expressing “walk”, whereas faster movements might be observed when expressing “run”. (3) The ease of developing acquisition and developmental features of deictic verbs is expected to vary depending on language-specific characteristics, such as the presence or absence of subject omission as well as frequency of gesture use during conversations, which are culturally influenced. Future research should progress in a cross-cultural manner, targeting children with diverse mother tongues for comparative studies. In investigating these three points, combining body movements with other measures, such as measuring brain activity (Kockler et al. 2010) and tracking eye movements (Asaoka et al. 2021), could provide more comprehensive data.

In conclusion, this study highlights the intricate acquisition process of the deictic verbs “come/go” in Japanese-speaking children. The findings indicate that appropriate verbal responses with corresponding body movements may be associated with the difficulty level of the question type. However, this synchronization seems to fade as children become increasingly proficient. To gain more insight into this phenomenon, future research should examine relatively large, more diverse samples, and incorporate cross-cultural perspectives. This could deepen the understanding of how children grasp these essential linguistic nuances.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/languages9100321/s1. Supplement S1: Experimental items.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A. and T.T.; methodology, H.A. and T.T.; software, H.A.; validation, H.A.; formal analysis, H.A. and T.T.; investigation, H.A.; resources, H.A.; data curation, H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.; writing—review and editing, T.T.; visualization, H.A. and T.T.; supervision, T.T.; project administration, H.A.; funding acquisition, H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP21K13627, JP24K06171.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Hiroshima University (protocol number HR-ES-001544 and date of approval 1 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the parents of each participant involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

This study analyzed publicly available datasets, which can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25954711 (accessed on 30 September 2024).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the children and their parents who participated in this study. We would also like to sincerely thank T. Nomura and A. Asaoka for their assistance with the experiments. Our special thanks go to D. Chambers for her invaluable suggestions on the content and English proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1 presents the question sentences and examples of responses from Table 2 translated into natural Japanese conversations suitable for the comprehension of elementary school students.

Table A1.

Stimulus sets and sample responses in Japanese.

Table A1.

Stimulus sets and sample responses in Japanese.

| Type | No. | Question Sentence | Example of Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| come? → come | 1 | 先生遅いね。来るかな? sensei osoi ne ku-ru ka-na teacher late SFP come-NPAST Q-PART | 多分後少ししたら来るかなぁ。 tabun ato sukoshi shi-tara ku-ru ka-na-a maybe after a little do-COND come-NPAST Q-PART-EMPH |

| 2 | 今年もサンタさん来るかな? kotoshi mo santa-san ku-ru ka-na this.year also Santa-HON come-NPAST Q-PART | うん、来ると思うよ。 un ku-ru to omo-u yo yeah come-NPAST QUOT think-NPAST SFP | |

| 3 | みんな、3時までに来るかな? minna san-ji made-ni ku-ru ka-na everyone three-o’clock by come-NPAST Q-PART | わからないけど、来るといいなぁ。 wakara-nai kedo ku-ru to ii na-a not.know-NPAST but come-NPAST QUOT good SFP-EMPH | |

| 4 | メイ、明日は学校に来るかな? Mei ashita wa gakkou ni ku-ru ka-na Mei tomorrow TOP school to-DAT come-NPAST Q-PART | 明日は来るといいなぁ。 ashita wa ku-ru to ii na-a tomorrow TOP come-NPAST QUOT good SFP-EMPH | |

| 5 | ミッキー、もうすぐ来るかな? mikkii mousugu ku-ru ka-na Mickey soon come-NPAST Q-PART | うん、来ると思うよ。 un ku-ru to omo-u yo yeah come-NPAST QUOT think-NPAST SFP | |

| come? → go | 6 | 今日、僕の家に遊びに来る? kyou boku no uchi ni asobi ni ki-ru today I GEN home to-DAT play DAT come-NPAST | もちろん!放課後に行くね。 mochiron houkago ni i-ku ne of.course after.school to-DAT go-NPAST SFP |

| 7 | 明日、僕の誕生日会があるんだけど、来る? ashita boku no tanjoubi.kai ga a-ru n da kedo ku-ru tomorrow I GEN birthday.party NOM have-NPAST EXPL COP PRTCL come-NPAST | もちろん!行くよ。 mochiron i-ku yo of.course go-NPAST SFP | |

| 8 | 日曜日、うちでバーベキューするんだけど、来る? nichiyoubi uchi de baabekyuu su-ru n da kedo ku-ru Sunday home LOC barbecue do-NPAST EXPL COP PRTCL come-NPAST | バーベキュー大好き!行くね。 baabekyuu daisuki i-ku ne barbecue love go-NPAST SFP | |

| 9 | ピアノの発表会があるんだけど、見に来る? piano no happyoukai ga a-ru n dakedo mi ni ku-ru piano GEN recital NOM have-NPAST EXPL COP PRTCL see DAT come-NPAST | いいね!すっごく見に行きたい。 ii ne suggoku mi ni ik-i-tai good SFP really see DAT go-DES-NPAST | |

| 10 | 校庭でサッカーするんだけど、来る? koutei de sakkaa su-ru n da kedo ku-ru schoolyard LOC soccer do-NPAST EXPL COP PRTCL come-NPAST | うん!行く。 un ik-u yeah go-NPAST | |

| go? → go | 11 | 今日の放課後、一緒に図書館に行く? kyou no houka.go issho ni toshokan ni i-ku today GEN after.school together DAT library to-DAT go-NPAST | いいよ、一緒に行こう。 ii yo issho ni ik-ou good SFP together with go-HORT |

| 12 | 昼休み、校庭に遊びに行く? hiru.yasumi koutei ni asobi ni ik-u lunch.break schoolyard to-DAT play DAT go-NPAST | うん、行きたい。 un ik-i-tai yeah go-DES-NPAST | |

| 13 | 一緒に公園に遊びに行く? issho ni kouen ni asobi ni ik-u together DAT park to-DAT play DAT go-NPAST | もちろん、行く。 mochiron ik-u of.course go-NPAST | |

| 14 | 今日、一緒にプールに行く? kyou issho ni puuru ni ik-u today together DAT pool to-DAT go-NPAST | うん、一緒に行こう。 un issho ni ik-ou yeah together DAT go-HORT | |

| 15 | 休み時間、校庭に走りに行く? yasumi.jikan koutei ni hashiri ni ik-u break.time schoolyard to-DAT run-GER DAT go-NPAST | もちろん、走りに行く。 mochiron hashiri ni ik-u of.course run-GER DAT go-NPAST | |

| go? → come | 16 | 昼休み、◯◯さんのクラスに遊びに行っていい? hiru.yasumi ○○san no kurasu ni asobi ni it-te ii lunch.break ○○-HON GEN class to-DAT play DAT go-TE good | もちろん、来てね。 mochiron ki-te ne of.course come-TE SFP |

| 17 | ◯◯さんの班のツリー、見に行っていい? ○○san no han no tsurii mi ni it-te ii ○○-HON GEN group GEN tree see DAT go-TE good | うん、見に来てね。 un mi ni ki-te ne yeah see DAT come-TE SFP | |

| 18 | ねぇねぇ、明日、◯◯さんの家に遊びに行っていい? nee.nee ashita ○○san no ie ni asobi ni it-te ii hey.hey tomorrow ○○-HON GEN house to-DAT play DAT go-TE good | いいよ、遊びに来てね。 ii yo asobi ni ki-te ne good SFP play DAT come-TE SFP | |

| 19 | そっちに行っていい? socchi ni ik-TE ii there to-DAT go-TE good | もちろん、来ていいよ。 mochiron ki-te ii yo of.course come-TE good SFP | |

| 20 | 明日の授業参観、パパ、見に行っていい? ashita no jugyou.sankan papa mi ni it-te ii tomorrow GEN open.class dad see DAT go-TE good | ちょっと緊張するけど、来ていいよ。 chotto kinchou su-ru kedo ki-te ii yo a.bit nervous do-NPAST but come-TE good SFP |

Note. The top row shows the Japanese sentence in standard Japanese script (kanji and kana), presenting the natural Japanese conversation as it would be spoken by elementary school students. The middle row provides a Romanized Japanese version with a word-by-word breakdown, offering a phonetic representation of the Japanese sentence with each word or grammatical element separated by slashes (/). The bottom row gives a word-by-word English gloss, providing a literal English translation or grammatical explanation for each Japanese element, aligned with the middle row.

References

- Asaoka, Hiroshi, Chitose Baba, Natsumi Fujimoto, Chisa Kobayashi, and Fumiyuki Noro. 2021. Improving the Use of Deictic Verbs in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Developmental Neurorehabilitation 24: 525–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asaoka, Hiroshi, Tomoya Takahashi, Jiafei Chen, Aya Fujiwara, Masataka Watanabe, and Fumiyuki Noro. 2019. Difficulties in Spontaneously Performing Level 2 Perspective-Taking Skills in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Advances in Autism 5: 243–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, Philip S., and Catherine Crain-Thoreson. 1993. Pronoun Reversals: Who, When, and Why? Journal of Child Language 20: 573–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elekes, Fruzsina, Máté Varga, and Ildikó Király. 2017. Level-2 Perspectives Computed Quickly and Spontaneously: Evidence from Eight-to 9.5-Year-Old Children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 35: 609–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freundlieb, Martin, Ágnes M. Kovács, and Natalie Sebanz. 2016. When Do Humans Spontaneously Adopt Another’s Visuospatial Perspective? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 42: 401–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Chuanxiuyue, Elizabeth R. Chrastil, and Mary Hegarty. 2022. A New Psychometric Task Measuring Spatial Perspective Taking in Ambulatory Virtual Reality. Frontiers in Virtual Reality 3: 971502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Hiroyuki, Iori Tani, Ryoji Yukihiro, Jun Adachi, Koichi Hara, Megumi Ogasawara, Masahiko Inoue, Yoko Kamio, Kazuhiko Nakamura, Tokio Uchiyama, and et al. 2012. Validation of an Interview-Based Rating Scale Developed in Japan for Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 6: 1265–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, Klaus, and Lindsey Anne Thomson. 2010. The Embodied Nature of Spatial Perspective Taking: Embodied Transformation Versus Sensorimotor Interference. Cognition 114: 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kockler, Hanna, Lukas Scheef, Ralf Tepest, Nicole David, Bettina H. Bewernick, Albert Newen, Hans H. Schild, Mark May, and Kai Vogeley. 2010. Visuospatial Perspective Taking in a Dynamic Environment: Perceiving Moving Objects from a First-Person-Perspective Induces a Disposition to Act. Consciousness and Cognition 19: 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Anthony, R. Peter Hobson, and Shulamuth Chiat. 1994. I, You, Me, and Autism: An Experimental Study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 24: 155–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, Catherine, Michael Rutter, and Ann Le Couteur. 1994. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A Revised Version of a Diagnostic Interview for Caregivers of Individuals with Possible Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 24: 659–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manwaring, Stacy S., Ashley L. Stevens, Alfred Mowdood, and Mellanye Lackey. 2018. A Scoping Review of Deictic Gesture Use in Toddlers with or At-Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments 3: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masataka, Nobuo. 1998. Communicative Behavior and Gestures: The Acquisition Process of the Use of “Go” and “Come”. Japanese Linguistics 17: 32–41. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, David. 1992. Hand and Mind: What Gestures Reveal About Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Michelon, Pascale, and Jeffrey M. Zacks. 2006. Two Kinds of Visual Perspective Taking. Perception & Psychophysics 68: 327–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, Akiko, Yanni Liu, Diane L. Williams, Timothy A. Keller, Nancy J. Minshew, and Marcel Adam Just. 2011. The Neural Basis of Deictic Shifting in Linguistic Perspective-Taking in High-Functioning Autism. Brain 134: 2422–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murofushi, Kiyoko. 1998. A Comment on Shimizu and Yamamoto’s Article: Toward a Giant Step. Japanese Journal of Behavior Analysis 12: 44–48. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent-Interview ASD Rating Scale (PARS) Committee. 2013. Parent-Interview ASD Rating Scale-Text Revision. Tokyo: Spectrum. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, Anna Sophia, and Maike Schindler. 2023. Motion Capture Systems and Their Use in Educational Research: Insights from a Systematic Literature Review. Education Sciences 13: 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalowitz, Norman S., and Sidney J. Segalowitz. 1993. Skilled Performance, Practice, and the Differentiation of Speed-up from Automatization Effects: Evidence from Second Language Word Recognition. Applied Psycholinguistics 14: 369–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibamoto, Janet S. 1983. Subject Ellipsis and Topic in Japanese. Paper in Linguistics 16: 233–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steggemann, Yvonne, Kai Engbert, and Matthias Weigelt. 2011. Selective Effects of Motor Expertise in Mental Body Rotation Tasks: Comparing Object-Based and Perspective Transformations. Brain and Cognition 76: 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, Kazuhiko, Nagoshi Naoko, and Konuki Satoru. 2008. Picture Vocabulary Test–Revised. Tokyo: Nihon Bunka Kagakusha. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Alfred B., and Jeffrey M. Zacks. 2010. The Role of Animacy in Spatial Transformations. Memory & Cognition 38: 982–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zacks, Jeffrey M., and Barbara Tversky. 2005. Multiple Systems for Spatial Imagery: Transformations of Objects and Bodies. Spatial Cognition & Computation: An Interdisciplinary Journal 5: 271–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubin, David A., and Lynne E. Hewitt. 1995. The Deictic Center: A Theory of Deixis in Narrative. In Deixis in Narrative: A Cognitive Science Perspective. Edited by Judith F. Duchan, Gail A. Bruder and Lynne E. Hillsdale. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 129–55. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).