Abstract

Although possessing flexibility and accessibility, asynchronous online courses suffer from high attrition and cause unsatisfactory learning performance, leading to a pressing need to understand factors influencing learners’ continuance of learning intention. Based on the expectation confirmation model, this study investigated perceived enjoyment as an extended variable to unpack the mediating effects of perceived usefulness and perceived enjoyment on the relationship between confirmation and continuance intention. Quantitative data from 254 learners enrolled in asynchronous online English courses were obtained for data analysis. Results indicate that confirmation significantly and positively affects learners’ continuance intention to take the asynchronous online English courses. Perceived usefulness and perceived enjoyment significantly mediate the relationship between confirmation and continuance intention. The total indirect effect of confirmation on continuance intention through perceived enjoyment and perceived usefulness and the combination of perceived enjoyment and perceived usefulness was 55.52%. Additionally, interviews with five learners revealed that despite limited real-time interaction, they highly value asynchronous online courses given that they promote self-regulated learning, offer choice freedom, foster a sense of achievement, and reduce anxiety and embarrassment risks that trigger their learning enjoyment. This study provided deep insights into factors influencing EFL learners’ decisions in asynchronous learning. Instructors are suggested to improve the quality of courses, provide timely feedback, and design tasks to improve learners’ perceptions of enjoyment and usefulness to further improve learners’ confirmation of online courses and their continuance intention to engage in online synchronous learning.

1. Introduction

Online learning has experienced a significant surge in popularity, emerging as a mainstream trend in educational settings [1]. Within this background, foreign language learners increasingly gravitate towards online platforms to learn language [2,3,4]. The authentic and multimodal language learning materials provided by online learning courses help learners develop language skills and improve language competence [5,6]. Among diverse courses, asynchronous online courses gain popularity among students, and unlike synchronous courses that require students to carry out Livestream learning [7], asynchronous courses enable students to learn at their own pace and convenience, customize their learning experience to suit their personal preferences without any time limitation [8,9], and thus, this personalized learning form improves learners’ comprehension and memory [8].

Despite the advantages of asynchronous learning, research pointed out that the drop-out rates of asynchronous courses, such as MOOCs, are quite high [10,11]. The dropping-out behavior hampers the improvement of learners’ knowledge acquisition, reduces learners’ learning persistence, and in the long run, will reduce their motivation and self-efficacy [12].

To solve this problem, researchers have examined factors that lead to learners’ intention to continue asynchronous learning, by adopting an extended expectation-confirmation model (ECM) [13,14,15]. In this model, confirmation indicates the alignment between students’ learning expectations and their actual experience [16,17] and is an important antecedent that influences satisfaction, which further leads to continuance intentions. When learners confirm the function or usefulness of a learning system, they are more likely to continue learning, because understanding the function of a system often reveals its practical applications in learning for a specific purpose. This awareness of if/how the system can be used to solve problems or achieve goals makes learning more relevant and meaningful. Studies examining this relationship in the asynchronous learning setting remain insufficient. Therefore, this study investigated the impact of learners’ confirmation on their continuance intention under the context of asynchronous online English courses.

Foreign language learning is a complex and dynamic process in which psycho-emotional factors influence learning [18,19,20,21]. Positive emotions, such as enjoyment, are conducive to improving language learning motivation and learning performance [22,23,24]. This study also examined the mediating role of perceived enjoyment and perceived usefulness in the relationship between confirmation of expectation and continuance intention.

In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted to understand learners’ perceptions of asynchronous online English learning. Research questions of the study are, RQ1: What are the mediating roles of perceived enjoyment and perceived usefulness in explaining language learners’ continuance of learning intentions of asynchronous online English courses? RQ2: How do language learners perceive asynchronous online courses in terms of their usefulness and enjoyment? By uncovering the intricate interconnections between the variables in the research model, this study enriches people’s understanding of the expectation confirmation model and provides valuable insights for college teachers to design online courses and course platforms to select courses.

2. Model Development

2.1. Asynchronous Online English Learning

Asynchronous learning is a form of education, instruction, and learning that does not occur in the same place or at the same time [9]. Teachers are supposed to upload learning materials (texts, videos) to a specific learning platform (e.g., MOOC) and provide suggestions, organize interactions, and provide feedback for students in the learning process.

Although asynchronous courses are criticized for the lack of oral production opportunities and interactions and cannot replace face-to-face teaching and learning [25,26], existing problems, such as limited time for class teaching, lack of learning space and authentic materials, and unsatisfying teacher quality, seem to highlight that asynchronous learning is a good way for Chinese EFL learners, especially during pandemic times [9].

English learning demonstrates individual differences and, to a large degree, is based on knowledge accumulation. It is important for EFL learners to be trained to address their weaknesses. Asynchronous online courses offer real and multimodal language learning materials, which can help learners develop language skills and improve language competence [5,6]. And for those who demonstrate reluctance in real-time interactions, asynchronous learning better suits their personal preferences and learning styles [8].

However, most existing studies on asynchronous learning failed to focus on specific fields, such as English learning [25]. Therefore, this study examined asynchronous online learning in an English learning context, aiming to enrich asynchronous learning literature and provide suggestions for education stakeholders to improve teaching and learning.

2.2. Expectation-Confirmation Model

Several theories and models have been used in previous studies to analyze people’s behavioral intention to use information systems, such as the technology acceptance model (TAM), Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), Information Systems Success Model (ISSM) and expectation-confirmation model (ECM). Among them, the ECM is a model particularly aiming to understand people’s continuance intention, it concerns users’ post-using experience instead of their first adoption and acceptance [27,28]. Therefore, the ECM is chosen as a theoretical framework in this study to examine students’ continuance intention to perform asynchronous online learning.

Proposed by Bhattacherjee [29], the ECM is widely used in business settings to predict consumers’ behaviors. It has been further contextualized in the educational setting to explain learners’ continuance of learning intentions [30], which indicate students’ willingness to continue learning. For example, Huang and Zou [31] suggested its validity to explain English learners’ continuance of learning intentions to use AI in practicing English speaking. The ECM encompasses four key variables: perceived usefulness, satisfaction, confirmation, and continuance intention [28].

Adapted from the technology acceptance model, perceived usefulness (PU) refers to users’ perceptions of the benefits when using a system or technology, such as enhancing performance or attaining their goals [16,29]. Many studies suggested the importance of PU in understanding technology users’ attitudes and subsequent use intentions [2,31,32,33]. Contextualized in asynchronous online learning, PU measures the degree to which English learners perceive the use of asynchronous online courses as beneficial in enhancing English learning. Concerned about users’ perceptions in the post-adoption phase, confirmation indicates the degree to which their experiences are aligned with initial anticipations [13,34]. Positive or negative, confirmation affects their fondness for and attitudes toward the product, as well as their continuance behaviors. In this study, confirmation indicates the degree to which English learners perceive the actual online learning experiences as matching their expectations, including the qualities of learning contents, platform service, and overall learning experiences. Continuance intention indicates a user’s willingness to stick with a particular technology over a period. It represents an enduring commitment between the technology and the users beyond the initial adoption phase [29]. In this study, it refers to the intention of English learners to continue learning with asynchronous online English courses. In the original ECM, satisfaction indicates the degree to which people believe the system makes them satisfied. But since its validity is often questioned in existing studies, and the meaning may be perceived as similar to perceived usefulness, we excluded satisfaction in this study to avoid collinearity.

The relationships of the above variables have been examined and confirmed by previous studies in the context of online learning. Confirmation has a significant influence on perceived usefulness and the continuance intention of users will be affected by perceived usefulness. These two relationships have been verified under different online learning styles and mediums, including MOOC [14,17,35,36], blog [37], immersive virtual reality and metaverse [38], mobile learning [39], and some learning platforms [27]. Furthermore, users’ confirmation has been found to have an indirect impact on continuance intention through perceived usefulness and satisfaction in the ECM [14,15,40,41]. In this study, we made a hypothesis that confirmation can directly and significantly affect continuance intention.

2.3. Extended Variable: Perceived Enjoyment

In technology adoption settings, Davis et al. [42] suggested that perceived enjoyment refers to the degree of pleasure that arose from technological utilization, without concern about any performance outcomes caused by using it. In the current research, it refers to the pleasure experienced by English learners when learning from asynchronous online learning [43]. Perceived enjoyment is an intrinsic motivation that is fostered by positive affective experiences and can affect learners’ intention behavior [44].

Studies suggested that perceived enjoyment exerted an important role in perceived usefulness when English learners adopt technological tools, such as online learning, social media tools, and AI-powered tutoring systems [45,46,47]. We believe if English learners enjoy using a particular tool in learning, they will tend to believe that they are useful.

Additionally, when learners confirm the affordances of online learning meet their expectations, they may perceive online learning as enjoyable, which may trigger their continuance of learning [11,44,46,48,49].

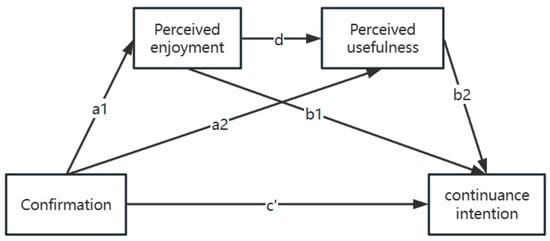

Based on the above rationales, a serial mediation model was proposed to test the effects of the constructs on the continuance of learning intention (Figure 1). The four hypotheses are as follows:

H1.

Confirmation has a significant impact on learners’ continuance intention.

H2.

Perceived enjoyment mediates the relationship between confirmation and continuance intention.

H3.

Perceived usefulness mediates the relationship between confirmation and continuance intention.

H4.

Perceived enjoyment and usefulness serially mediate the relationship between confirmation and continuance intention.

Figure 1.

The proposed research model.

3. Method

This study employs both questionnaire surveys and semi-structured interviews to examine the mechanisms of perceived usefulness, perceived enjoyment, confirmation, and continuance intention by contextualizing the study in asynchronous online English learning. The mixed methods allow for a nuanced exploration of the subjective experiences and perceptions of learners while enabling the quantification and statistical analysis of key relationships between variables [50].

3.1. Participants

Participants of the quantitative phase were 254 university English learners in China. They were invited to participate in this study based on several considerations. They must have had asynchronous online English learning experiences, and they could vary in their study year, gender, and majors. The specific demographic information is delineated in Table 1. Among them, 135 (53.15%) of participants were males, and 119 (46.85%) were females. They had diverse majors, and their ages ranged from 18 to 28 (M = 21.58, SD = 2.013). Most participants suggested they had learned online for years, reflecting a sustained utilization of educational resources online.

Table 1.

Demographic information of participants of quantitative phase.

For semi-structured interviews, five of them were interviewed to provide a deep understanding of their experience of asynchronous online English learning, based on their willingness to share. These individuals represent a range of educational backgrounds, such as majors, years of study, and experiences with online learning. Therefore, these data are considered to be representative. The detailed information on them is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Basic information of interviewees.

3.2. Instruments

For the quantitative phase, a questionnaire was employed to elicit learners’ responses toward asynchronous online English learning. The initial section was demographic information, encompassing gender, academic year, major, and online learning experience. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of diverse constructs: perceived usefulness (PU), confirmation (CNF), perceived enjoyment (PE), and continuance intention (CI). Items of these variables were adapted from authoritative publications to ensure robustness in reliability and validity. Specifically, measures for perceived usefulness, satisfaction, and continuance intention were adapted from the work of Bhattacherjee [16] and Lee [51], and items pertaining to perceived enjoyment were derived from the study by Koufaris [52]. The questionnaire employed a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

To ensure clear comprehension, original items underwent translation into Chinese, adhering to a standardized translation and back-translation procedure to maintain semantic consistency. Where necessary, adaptations were made to align with the study context. Reliability analyses demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency [53], as illustrated by Cronbach’s α coefficients ranging from 0.610 to 0.709 for individual construct (Table 3). Moreover, the overall instrument exhibited high reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.914.

Table 3.

Reliability and origin of the variables.

For the semi-structured interviews, the interview protocol was used to collect participants’ views on asynchronous online English courses, mainly including the enjoyment and usefulness of AOEC. Specific questions include: “Do you feel enjoyable when learning asynchronous online English course? How does this enjoyment affect your continuance intention of AOEC?”, “Do you find AOEC useful, and how does this usefulness affect your continuance intention of AOEC?”, and so on.

3.3. Research Procedure and Data Analysis

Data were collected after we received ethical approval from the institution. Considering the aim of the study, the study adopted a purposeful sampling to collect data. The researchers initially contacted university students who have online learning experiences to fill in online questionnaires. All participants were explicitly informed of the voluntariness of their involvement. Moreover, assurances regarding the confidentiality and anonymity of their personal information were provided at the outset of the questionnaire. Given the research focus on learners’ continuance online learning intention, a prerequisite of participation was their prior experience with online English learning, and therefore, the initial question posed to them in the questionnaire was “Have you previously enrolled in an online English course?” Only responses affirming this experience were considered valid for analysis.

The analysis of quantitative data employed a two-step approach by using SPSS 26.0. Firstly, descriptive analysis was performed to indicate the normality of the data and the means of the research variables. Secondly, the proposed serial mediation model was assessed with PROCESS v3.4.1 in SPSS. Ordinary least squares [54] in PROCESS enabled the researchers to examine the direct and indirect effects of variables in the model.

Qualitative data collection in this study involved conducting semi-structured interviews, allowing for flexibility in probing into participants’ responses and delving deeper into emerging themes. With the consent of the 5 interviewees, the researchers recorded the interviews to avoid the omission of important information and to ensure the accuracy of the data.

For qualitative data, the second researcher transcribed the interview recordings verbatim and revised them in accordance with the recordings, to obtain a true and comprehensive interview transcript. The transcripts were then sent to the interviewees to verify the authenticity of their meaning. A six-stage thematic data analysis was adopted to achieve a deep understanding [55]. Firstly, two authors read through the interview transcripts to be familiar with the data. Secondly, some interesting statements were tagged by the initial codes. Thirdly, potential codes with similar meanings were combined into one theme. Fourthly, candidate themes were reviewed to avoid overlap and omission and to make them more coherent and clearer. Fifthly, the final themes were refined for better understanding. Finally, the findings were written. For example, interviewee A said, “it improved my oral expression fluency and trained my mindset.” and interviewee B said, “…If you don’t understand the contents, you can go back and listen to it right away, it is quite easy and workable.” Based on the meaning, they were coded as “improves English skills” and “enables autonomous learning”, which indicate a theme of perceived usefulness. We clarified the theme in the findings as “Asynchronous English learning improves language skills and self-regulation”, as shown in the findings. Detailed results are shown in Section 4.2.

To ensure reliability, two authors individually coded the interview materials from two participants and then compared the results. They achieved a consistency of 94.7%, ensuring the feasibility of this data analysis method as well as the validity of the findings. The two authors also discussed the differences and reached a consensus. Following this way, the authors coded the remaining three interview data. Several discussions were conducted to check and revise themes to avoid omissions of nuanced data and increase reliability and accuracy.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics for all variables, demonstrating mean values ranging from 5.72 to 5.81 (SD ranging from 0.72 to 0.77), indicating participants’ favorable attitudes to online learning. Univariate normality was assessed by examining maximum likelihood estimates of skewness and kurtosis, yielding values ranging from −1.65 to −1.43 and from 2.15 to 3.97, respectively. These values adhere to the recommended thresholds of |3| and |8| [56].

Table 4.

Results of descriptive statistics.

4.2. Results of Mediation Analysis

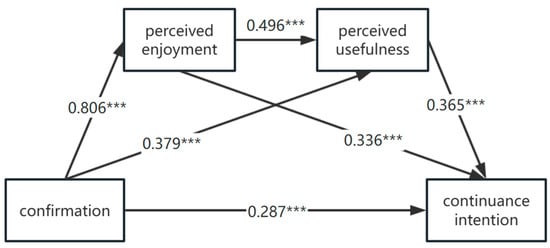

Table 5 and Figure 2 present the results of the mediation analysis. The total effect observed indicated a significantly positive correlation between confirmation and continuance intention (β = 0.842, p < 0.001). Specifically, confirmation exerted a substantial direct influence on continuance intention (β = 0.287, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. Moreover, the role of perceived enjoyment (a1b1) as a mediating variable is statistically significant (Effect = 0.271, 95% CI = [0.148, 0.415]), with a positive significant influence of confirmation on perceived enjoyment (β = 0.806, p < 0.001) and perceived enjoyment on continuance intention (β = 0.336, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was corroborated. Similarly, the mediation effect of perceived usefulness (a2b2) is also significant (Effect = 0.139, 95% CI = [0.069, 0.213]), with a positive significant influence of confirmation on perceived usefulness (β = 0.379, p < 0.001) and perceived usefulness on continuance intention (β = 0.365, p < 0.001), validating Hypothesis 3. Finally, the combined mediating influence of perceived enjoyment and perceived usefulness (a1db2) was established as statistically significant (Effect = 0.146, 95% CI = [0.078, 0.230]), with positive significant influence of perceived enjoyment on perceived usefulness (β = 0.496, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was confirmed. Since confirmation has a significant direct effect on continuance intention, this model is a partially mediated model [57].

Table 5.

Results of serial mediation effects.

Figure 2.

Results of the research model. Note: *** p < 0.001.

4.3. Findings from Semi-Structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews helped researchers to achieve a deep understanding of students’ perceptions of asynchronous online English learning. Supporting the results of the quantitative phase (Figure 2), interviewees perceived confirmation of their expected learning mode and believed asynchronous online English courses to be very useful in learning. They did not perceive any technical difficulty when studying online, and instead, some felt happiness and had pleasant moods, and this mentality led to more positive feelings of learning effectiveness.

Theme 1: Asynchronous English learning improves language skills and self-regulation

Aside from helping English learners improve English knowledge and skills to achieve learning goals, such as succeeding in exams, interviews suggested that one of the notable advantages of asynchronous online English courses lies in their ability to facilitate students’ self-regulated learning. Without the constraints of the fixed class time, learners are provided with the flexibility to learn at their own pace and allocate more time to areas that require additional attention and practice and less time to concepts that they have already mastered.

…It improved my oral expression fluency and trained my mindset.(From A)

…If you don’t understand the contents, you can go back and listen to it right away, it is quite easy and workable.(From B)

…Well, online classes let me have more free time. I can arrange my study, and if I have questions I can even replay later, … It is just what I want, … you cannot do it in traditional classes.(From D)

Theme 2: Asynchronous learning enjoyment influences their perceptions of usefulness and continuance intentions

Enjoyment was suggested by many participants, and this feeling emerged when they perceived accomplishment, technology affordances, and reduced anxiety in learning.

…I took a lot of notes while learning online, I can ask questions and teachers and peers will answer, after a while, my English scores are improved, this improvement made me feel accomplishment, very happy, it also increased my interest in continuing learning these courses.(From D)

…I really like the fancy statistical functions of these courses, … teachers in traditional face-to-face classes only use test papers or they ask questions, very boring…These statistical results come out immediately when I submit my answers, very informative to me, I will surely continue my learning here.(From A)

Interviewees also highlighted sources of enjoyment, including the vibrant online discussions and the teachers’ humorous and cheerful presenting styles. They reduced anxiety and potential embarrassment that may arise in the real-time interactions, thereby enhancing participants’ overall satisfaction and comfort in asynchronous.

Some online courses set up discussion forums where students can ask questions to teachers and peers so that problems can be solved efficiently, which improves learners’ fondness.

…Online classes, especially asynchronous mode, are not as intense as offline classes, for example, in offline classes, you may feel anxious because you may be questioned by your teacher at any time, but asynchronous online classes atmosphere is more relaxed, and it may be better for me to study.(From B)

5. Discussion

In the original ECM, a mediation effect was suggested, namely, confirmation influences satisfaction, which further influences continuance intention. However, there might be a meaning similarity that leads to collinearity between confirmation and satisfaction, as suggested in existing studies, in addition, if students confirm that their expectations were met, it is very likely that they will continue learning. Moreover, the original ECM also suggested that confirmation was a very important variable and could have a direct impact on CI, and this relationship needed to be examined. This way, our study filled in the research gap by examining the direct relationship between confirmation and continuous intention by contextualizing the study in a synchronous English online learning setting.

In this investigation, we also included perceived enjoyment and perceived usefulness as sequential mediators. The research findings indicate a direct and statistically significant influence of confirmation on students’ continuance intention (H1), indicating that when students believe their expectations of the asynchronous courses were fulfilled, they would be more willing to demonstrate an augmented intention to sustain their involvement.

Furthermore, perceived enjoyment was found to significantly mediate the relationship between confirmation and continuance intention (H2). This observation is consistent with prior research that underscores the role of positive affective factors, such as enjoyment, in shaping engagement in online learning contexts [18,58]. Specifically speaking, this result is in line with Tao et al. [59]’s research on MOOC and Roca and Gagne [60]’s research on e-learning courses but is contrary to research findings from Lee [51] concerning e-learning service with the TAM, TPB, and ECM. To explain the relationship, this study suggested EFL learners’ enjoyment comes from the sense of accomplishment in asynchronous learning, the interesting discussion forums, and the humorous lecturers. This positive emotion during learning fosters psychological attachment, reinforcing learners’ commitment to online learning, their preferred mode of learning. Moreover, it serves as a mechanism to counteract the isolation or lack of interactions associated with asynchronous online learning [61].

In addition, the affirmative correlation between confirmation and perceived enjoyment has also been validated in MOOC learning in 74 countries [41], online learning platforms in China [62], e-learning platforms in Iraq and Malaysia [27], and MOOC in India [11]. These all underscored the significance of aligning learners’ expectations with positive learning experiences. Interviewees mentioned that learners’ expectations would be confirmed by comfort and pleasant experiences, such as the interesting course materials, proficient and acceptable language instruction from lecturers, and the conducive learning atmosphere in communities. When these happen, they tend to obtain a higher level of enjoyment from the AOEC learning process.

Similarly, perceived usefulness was found to be a significant mediator in the relationship between confirmation and continuance intention (H3). This finding is in line with the previous studies, particularly those employing the expectation-confirmation model [11,14,15,41] in MOOC settings. Learners affirmed that the AOECs are very useful in realizing self-regulated learning, improving English skills, and achieving their English learning goals, as shown in interviews.

Additionally, the study confirmed the serial mediation effect of perceived enjoyment and perceived usefulness (H4). This is consistent with the previous research [45,46,47,63] contextualized in social media learning platforms, AI-powered learning systems, and other online learning carriers, but it conflicts with Obeid et al. [27]. The improvement of perceived enjoyment, which is similar to intrinsic motivation, shows learners’ recognition and affection for AOECs. Then, they will be more effective and productive in English learning [60]. Consequently, learners will view AOECs as valuable and useful tools for achieving their English learning goals, leading to a much higher level of perceived usefulness. In addition, the perceived enjoyment mentioned by interviewees mainly comes from the sense of accomplishment brought about by the improvement of their English knowledge, which is also a reflection of the usefulness of AOEC. This can also prove the close connection between the two variables.

6. Conclusions

This research investigated the relationship between confirmation of expectation and continuance intention of asynchronous online learning, with perceived enjoyment and perceived usefulness as mediating factors. The direct impact of confirmation on continuance intention was confirmed. Moreover, perceived enjoyment, perceived usefulness, and the sequential mediation of perceived enjoyment and perceived usefulness emerged as statistically significant in mediating the association between confirmation and continuance intention. The semi-structured interviews also highlighted the sources of perceived usefulness and enjoyment.

6.1. Implications

This study carries both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, it expands the ECM model to enable readers to have a deeper comprehension of factors influencing continuance intention. Additionally, it affirms the significance of confirmation in influencing continuance intention [28] and the importance of perceived usefulness and confirmation in supporting perceived enjoyment within educational settings.

Practically, this research holds implications for online learning platforms, course developers, and lecturers within the domain of asynchronous online learning. First of all, they should enhance the confirmation of students’ learning expectations. Platform operators or technological supporters should sustain close connections with course learners to timely know about their expectations and individualized learning requirements [64]. Furthermore, they are suggested to inform learners of their learning performance, whilst abstaining from exaggerated marketing practices, which may lead to users’ unrealistic initial expectations [35].

In addition, given the pivotal role of perceived usefulness in influencing continuance intention, lecturers and course developers are advised to focus on courses that cultivate learning or professional skills for practical applications [11]. They should augment the utility of courses by improving the design level of platforms, offering more beneficial course materials, facilitating the accessibility of educational resources, and diversifying supporting learning tools (such as seminars, hyperlinks, and assignments). Moreover, as the interviewees believed that the greatest usefulness of asynchronous online English courses is to facilitate self-regulated learning, some suggestions are provided for course platforms and lecturers. For example, lectures are supposed to clearly and logically mark the course chapters or units and provide a clear introduction to these chapters, so that students can accurately find contents they want to learn. In addition, lecturers can upload as many materials as they can so that students can choose based on their needs. Platform designers may provide a speed selection so that students can adjust the speed of the video playing. They can also record footprints that learners took so that they can review them afterward and arouse peers’ thinking as well.

Furthermore, prioritizing higher levels of perceived enjoyment can ensure user retention. Hence, online learning platforms should integrate entertainment elements into learning processes, such as engaging tasks [47] and discussion forums, which may have intense and interesting discussions. For example, platforms may provide a discussion function and bullet screens to allow students to comment on content during or after online learning, whether it is to praise the teacher, complain, or seek help. This will greatly increase students’ sense of participation and interest. To optimize students’ pleasure, gamified learning approaches, quizzes, and other innovative methods via multimedia capabilities are also advised [46]. While integrating enjoyable elements into the language learning process is essential, it is imperative to strike a balance with educational goals. Developers must ensure that those entertainments align with learners’ primary language learning goals [45].

6.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

The present study is constrained to a relatively small sample size and a limited selection of universities within China. To enhance the generalizability of findings, future research can endeavor to examine this model with a more expansive and diverse sample, encompassing a broader geographic scope. Such efforts will provide novel insights into the interrelationships among the variables under investigation.

Although the current investigation primarily examines confirmation and perceived usefulness, future research could encompass additional influential factors such as personality traits and other positive emotions. Some potential impacts of external factors can also have significant impacts on learners’ continuance intention, including lecturers’ instructional styles, peer influence, availability of high-quality resources, diverse learning materials, adept time management, course difficulty, as well as learners’ personal circumstances (socioeconomic status, health). However, the multifaceted nature of these variables precluded their comprehensive integration into the present study. Addressing these complexities in subsequent research will offer people a more holistic view of the field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.H. and S.L.; methodology, S.L.; formal analysis, S.L.; validation, F.H. and S.L.; investigation, F.H.; resources, S.L.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.H. and S.L.; writing—review and editing, F.H. and S.L.; supervision, F.H.; funding acquisition, F.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by Shanghai International Studies University (41004918, 23ZD010).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of School of Education at the Shanghai International Studies University (SISUGJ2024001, 1 January 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be received upon proper inquiry.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fan, J.; Tian, M. Satisfaction with Online Chinese Learning among International Students in China: A Study Based on the fsQCA Method. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Teo, T.; Zhou, M. Chinese Students’ Intentions to Use the Internet-Based Technology for Learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xiao, A. A Structural Equation Model of Online Learning: Investigating Self-Efficacy, Informal Digital Learning, Self-Regulated Learning, and Course Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1276266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A.; Zhang, L.J. Applications of Psycho-Emotional Traits in Technology-Based Language Education (TBLE): An Introduction to the Special Issue. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2024, 33, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Lee, K.S.; Chen, S.-T.; Sim, S.C. An Evaluative Study of a Mobile Application for Middle School Students Struggling with English Vocabulary Learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 95, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, S.; Crowther, D.; Isbell, D.R.; Kim, K.M.; Maloney, J.; Miller, Z.F.; Rawal, H. Mobile-Assisted Language Learning: A Duolingo Case Study. ReCALL 2019, 31, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Pu, Q. Factors Influencing Learners’ Continuance Intention toward One-to-One Online Learning. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 1742–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Pang, F.; Shadiev, R. Understanding College Students’ Continuous Usage Intention of Asynchronous Online Courses through Extended Technology Acceptance Model. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 9747–9765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Luo, J. Effectiveness of Synchronous and Asynchronous Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoushehgir, F.; Sulaimany, S. Negative Link Prediction to Reduce Dropout in Massive Open Online Courses. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 10385–10404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekha, I.S.; Shetty, J.; Basri, S. Students’ Continuance Intention to Use MOOCs: Empirical Evidence from India. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 4265–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goopio, J.; Cheung, C. The MOOC Dropout Phenomenon and Retention Strategies. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2021, 21, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.M.; Teo, T.; Rappa, N.A.; Huang, F. Explaining Chinese University Students’ Continuance Learning Intention in the MOOC Setting: A Modified Expectation Confirmation Model Perspective. Comput. Educ. 2020, 150, 103850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneji, A.A.; Ayub, A.F.M.; Khambari, M.N.M. The Effects of Perceived Usefulness, Confirmation and Satisfaction on Continuance Intention in Using Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). Knowl. Manag. E-Learn. 2019, 11, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Tang, C.; Rong, W.; Zhang, L.; Yin, C.; Xiong, Z. Task-Technology Fit Aware Expectation-Confirmation Model towards Understanding of MOOCs Continued Usage. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2017; pp. 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding Information Systems Continuance: An Expectation-Confirmation Model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohan, R.; Pal, D.; Funilkul, S.; Chutimaskul, W.; Eamsinvattana, W. How Gamification Leads to Continued Usage of MOOCs? A Theoretical Perspective. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 108144–108161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A.; Fathi, J. Grit and Foreign Language Enjoyment as Predictors of EFL Learners’ Online Engagement: The Mediating Role of Online Learning Self-Efficacy. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2023, 33, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solhi, M.; Derakhshan, A.; Ünsal, B. Associations between EFL Students’ L2 Grit, Boredom Coping Strategies, and Emotion Regulation Strategies: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A.; Noughabi, M.A. A Self-Determination Perspective on the Relationships between EFL Learners’ Foreign Language Peace of Mind, Foreign Language Enjoyment, Psychological Capital, and Academic Engagement. Learn. Motiv. 2024, 87, 102025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A.; Yin, H. Do Positive Emotions Prompt Students to Be More Active? Unraveling the Role of Hope, Pride, and Enjoyment in Predicting Chinese and Iranian EFL Students’ Academic Engagement. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A. Revisiting Research on Positive Psychology in Second and Foreign Language Education: Trends and Directions. Lang. Relat. Res. 2022, 13, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Derakhshan, A.; Zhang, L.J. Researching and Practicing Positive Psychology in Second/Foreign Language Learning and Teaching: The Past, Current Status and Future Directions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 731721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xu, L.; Li, J. Connecting Foreign Language Enjoyment and English Proficiency Levels: The Mediating Role of L2 Motivation. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1054657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okyar, H. University-Level EFL Students’ Views on Learning English Online: A Qualitative Study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Cui, G. Learning Beliefs of Distance Foreign Language Learners in China: A Survey Study. System 2010, 38, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, A.; Ibrahim, R.; Fadhil, A. Extended Model of Expectation Confirmation Model to Examine Users’ Continuous Intention Toward the Utilization of E-Learning Platforms. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 40752–40764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amin, M.; Muzareba, A.M.; Chowdhury, I.U.; Khondkar, M. Understanding E-Satisfaction, Continuance Intention, and e-Loyalty toward Mobile Payment Application during COVID-19: An Investigation Using the Electronic Technology Continuance Model. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2024, 29, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. An Empirical Analysis of the Antecedents of Electronic Commerce Service Continuance. Decis. Support Syst. 2001, 32, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.M.; Teo, T.; Rappa, N.A. Understanding Continuance Intention among MOOC Participants: The Role of Habit and MOOC Performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 112, 106455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Zou, B. English Speaking with Artificial Intelligence (AI): The Roles of Enjoyment, Willingness to Communicate with AI, and Innovativeness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 159, 108355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.; Huang, F.; Hoi, C.K.W. Explicating the Influences That Explain Intention to Use Technology among English Teachers in China. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2018, 26, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Dai, J.; Wang, C. Adoption of Blended Learning: Chinese University Students’ Perspectives. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Yousaf, A.; Mishra, A. How Pre-Adoption Expectancies Shape Post-Adoption Continuance Intentions: An Extended Expectation-Confirmation Model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Z.-J. Does MOOC Quality Affect Users’ Continuance Intention? Based on an Integrated Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnadi, B.; Widiantoro, A.D.; Prasetya, F.X.H. Investigating the Behavioral Differences in the Acceptance of MOOCs and E-Learning Technology. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 14, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.E.; Tang, T.-I.; Chiang, C.-H. Blog Learning: Effects of Users’ Usefulness and Efficiency towards Continuance Intention. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2014, 33, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Natale, A.F.; Bartolotta, S.; Gaggioli, A.; Riva, G.; Villani, D. Exploring Students’ Acceptance and Continuance Intention in Using Immersive Virtual Reality and Metaverse Integrated Learning Environments: The Case of an Italian University Course. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-T.; Lin, K.-Y. Understanding Continuance Usage of Mobile Learning Applications: The Moderating Role of Habit. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 736051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J. Exploring the Factors Affecting Learners’ Continuance Intention of MOOCs for Online Collaborative Learning: An Extended ECM Perspective. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 33, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraimi, K.M.; Zo, H.; Ciganek, A.P. Understanding the MOOCs Continuance: The Role of Openness and Reputation. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation to Use Computers in the Workplace1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y. Examining Mobile Instant Messaging User Loyalty from the Perspectives of Network Externalities and Flow Experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.; Noyes, J. An Assessment of the Influence of Perceived Enjoyment and Attitude on the Intention to Use Technology among Pre-Service Teachers: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C. English Learning Motivation with TAM: Undergraduates’ Behavioral Intention to Use Chinese Indigenous Social Media Platforms for English Learning. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2260566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; He, L.; Wong, I.A. Determinants Predicting Undergraduates’ Intention to Adopt e-Learning for Studying English in Chinese Higher Education Context: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 4221–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, A.; Cheung, A. Understanding Secondary Students’ Continuance Intention to Adopt AI-Powered Intelligent Tutoring System for English Learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 3191–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, F.; Ward, R.; Ahmed, E. Investigating the Influence of the Most Commonly Used External Variables of TAM on Students’ Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Perceived Usefulness (PU) of e-Portfolios. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Wang, Y.-S.; Lin, H.-H.; Tsai, T.-H. Developing and Validating a Model for Assessing Paid Mobile Learning App Success. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 27, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivankova, N.; Wingo, N. Applying Mixed Methods in Action Research: Methodological Potentials and Advantages. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 978–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-C. Explaining and Predicting Users’ Continuance Intention toward e-Learning: An Extension of the Expectation–Confirmation Model. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufaris, M. Applying the Technology Acceptance Model and Flow Theory to Online Consumer Behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitra, E.; Ramamurthy, S.; Mohamed, S.M.; Nadarajah, V.D. Study of the Impact of Objective Structured Laboratory Examination to Evaluate Students’ Practical Competencies. J. Biol. Educ. 2022, 56, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, Conditional, and Moderated Moderated Mediation: Quantification, Inference, and Interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.; Kenny, D. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, R.; Zhan, Q.; Lyu, C. Influence of Instructor Humor on Learning Engagement in the Online Learning Environment. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2023, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; Fu, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Qu, X. Key Characteristics in Designing Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) for User Acceptance: An Application of the Extended Technology Acceptance Model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022, 30, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, J.C.; Gagné, M. Understanding E-Learning Continuance Intention in the Workplace: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 1585–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simamora, R.M. The Challenges of Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Essay Analysis of Performing Arts Education Students. Stud. Learn. Teach. 2020, 1, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, J. Examining Continuance Intention of Online Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic: Incorporating the Theory of Planned Behavior into the Expectation–Confirmation Model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1046407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusuf, M.B.; Utami, N.P.; Hidayanto, A.N.; Shihab, M.R. Analysis of Intrinsic Factors of Mobile Banking Application Users’ Continuance Intention: An Evaluation Using an Extended Expectation Confirmation Model. In Proceedings of the 2017 Second International Conference on Informatics and Computing (ICIC), Jayapura, Indonesia, 1–3 November 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Lu, Y. Understanding Key Drivers of MOOC Satisfaction and Continuance Intention to Use. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 20, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).