Abstract

In this paper, we introduce the various types of generalized invexities, i.e., -invex/-pseudoinvex and -bonvex/-pseudobonvex functions. Furthermore, we construct nontrivial numerical examples of -bonvexity/-pseudobonvexity, which is neither -bonvex/-pseudobonvex nor -invex/-pseudoinvex with the same . Further, we formulate a pair of second-order non-differentiable symmetric dual models and prove the duality relations under -invex/-pseudoinvex and -bonvex/-pseudobonvex assumptions. Finally, we construct a nontrivial numerical example justifying the weak duality result presented in the paper.

1. Introduction

Decision making is an integral and indispensable part of life. Every day, one has to make decisions of some type or the other. The decision process is relatively easier when there is a single criterion or objective in mind. The duality hypothesis in nonlinear writing programs is identified with the complementary standards of the analytics of varieties. Persuaded by the idea of second-order duality in nonlinear problems, presented by Mangasarian [1], numerous analysts have likewise worked here. The benefit of second-order duality is considered over first-order as it gives all the more closer limits. Hanson [2] in his examination referred to one model that shows the utilization of second-order duality from a fairly alternate point of view.

Motivated by different ideas of generalized convexity, Ojha [3] formulated the generalized problem and determined duality theorems. Expanding the idea of [3] by Jayswal [4], a new kind of problem has been defined and duality results demonstrated under generalized convexity presumptions over cone requirements. Later on, Jayswal et al. [5] defined higher order duality for multiobjective problems and set up duality relations utilizing higher order -V-Type I suspicions. As of late, Suneja et al. [6] utilized the idea of -type I capacities to build up K-K-T-type sufficient optimality conditions for the non-smooth multiobjective fractional programming problem. Many researchers have done work related to the same area [7,8,9].

The definition of the G-convex function introduced by Avriel et al. [10], which is a further generalization of a convex function where G has the properties that it is a real-valued strictly-increasing, and continuous function. Further, under the assumption of G-invexity, Antczak [11] introduced the concept of the G-invex function and derived some optimality conditions for the constrained problem. In [12], Antczak extended the above notion and proved necessary and sufficient optimality conditions for Pareto-optimal solutions of a multiobjective programming problem. Moreover, defining G-invexity for a locally-Lipschitz function by Kang et al. [13], the optimality conditions for a multiobjective programming are obtained. Recently, Gao [14] introduced a new type of generalized invexity and derived sufficiency conditions under -Type-I assumptions.

In this article, we develop the meanings of -bonvexity/-pseudo-bonvexity and give nontrivial numerical examples for such kinds of existing functions. We formulate a second-order non-differentiable symmetric dual model and demonstrate duality results under -bonvexity/-pseudobonvexity assumptions. Furthermore, we build different nontrivial examples, which legitimize the definitions, as well as the weak duality hypothesis introduced in the paper.

2. Preliminaries and Definitions

Let denote n-dimensional Euclidean space and be its non-negative orthant. Let and be closed convex cones in and , respectively, with nonempty interiors. For a real-valued twice differentiable function defined on an open set in , denote by the gradient vector of g with respect to x at and the Hessian matrix with respect to x at . Similarly, , , and are also defined.

Let be an open set. Let be a differentiable function and where is the range of f such that G is strictly increasing on the range of f, and

Definition 1.

Let E be a compact convex set in . The support function of E is defined by:

A support function, being convex and everywhere finite, has a subdifferential, that is there exists a such that:

The subdifferential of is given by:

For a convex set , the normal cone to F at a point is defined by:

When E is a compact convex set, if and only if or, equivalently,

Definition 2.

The positive polar cone of a cone is defined by:

Now, we give the definitions of -invex/-pseudoinvex and -bonvex/-pseudobonvex functions with respect to η.

Definition 3.

If there exist functions and s.t.

then f is called -invex at with respect to

Definition 4.

If there exists functions and such that

then f is called -pseudoinvex at with respect to

Definition 5.

is -bonvex at if there exist and if ,

:

Definition 6.

is -pseudobonvex at if there exist and a function if

:

Remark 1.

If , then Definitions 5 and 6 become the -bonvex/-pseudobonvex functions with the same η.

Now, we present here functions that are -bonvexity/-pseudobonvexity, but neither -bonvex/-pseudobonvex nor -invex/-pseudoinvex with the same .

Example 1.

Let be defined as

A function is defined as:

Let be given as:

Furthermore, is given by:

To demonstrate that f is -bonvex at , we need to demonstrate that

Putting the estimations of , and G in the above articulation, we get:

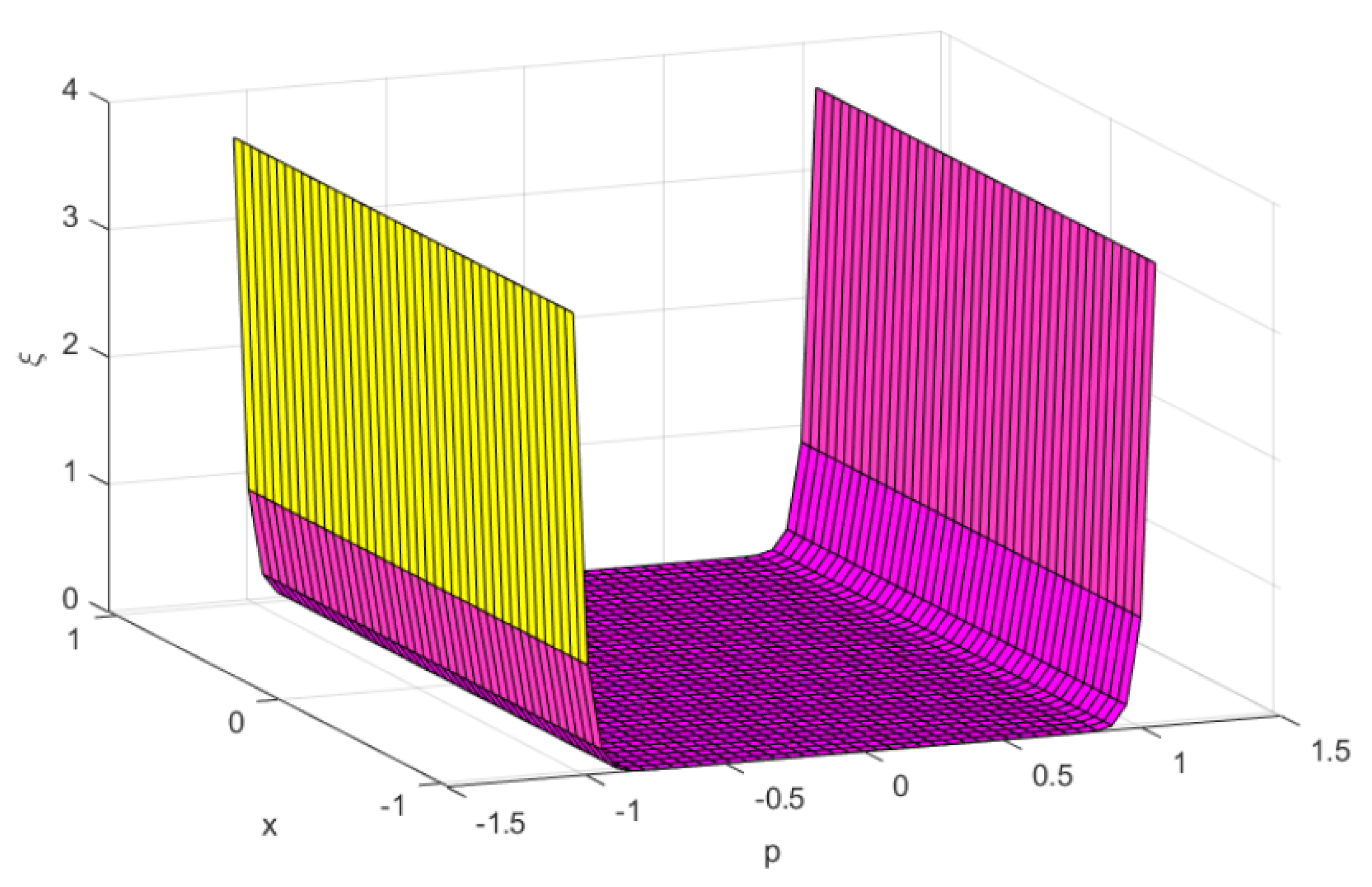

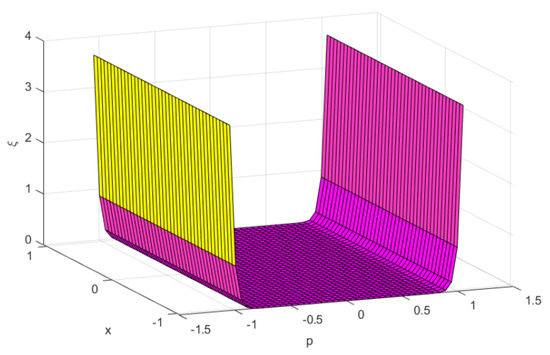

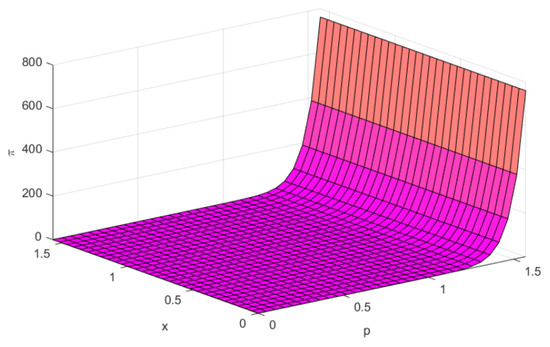

for which at , we get: (clearly, from Figure 1).

Figure 1.

, and .

Therefore, f is -bonvex at .

Next, let:

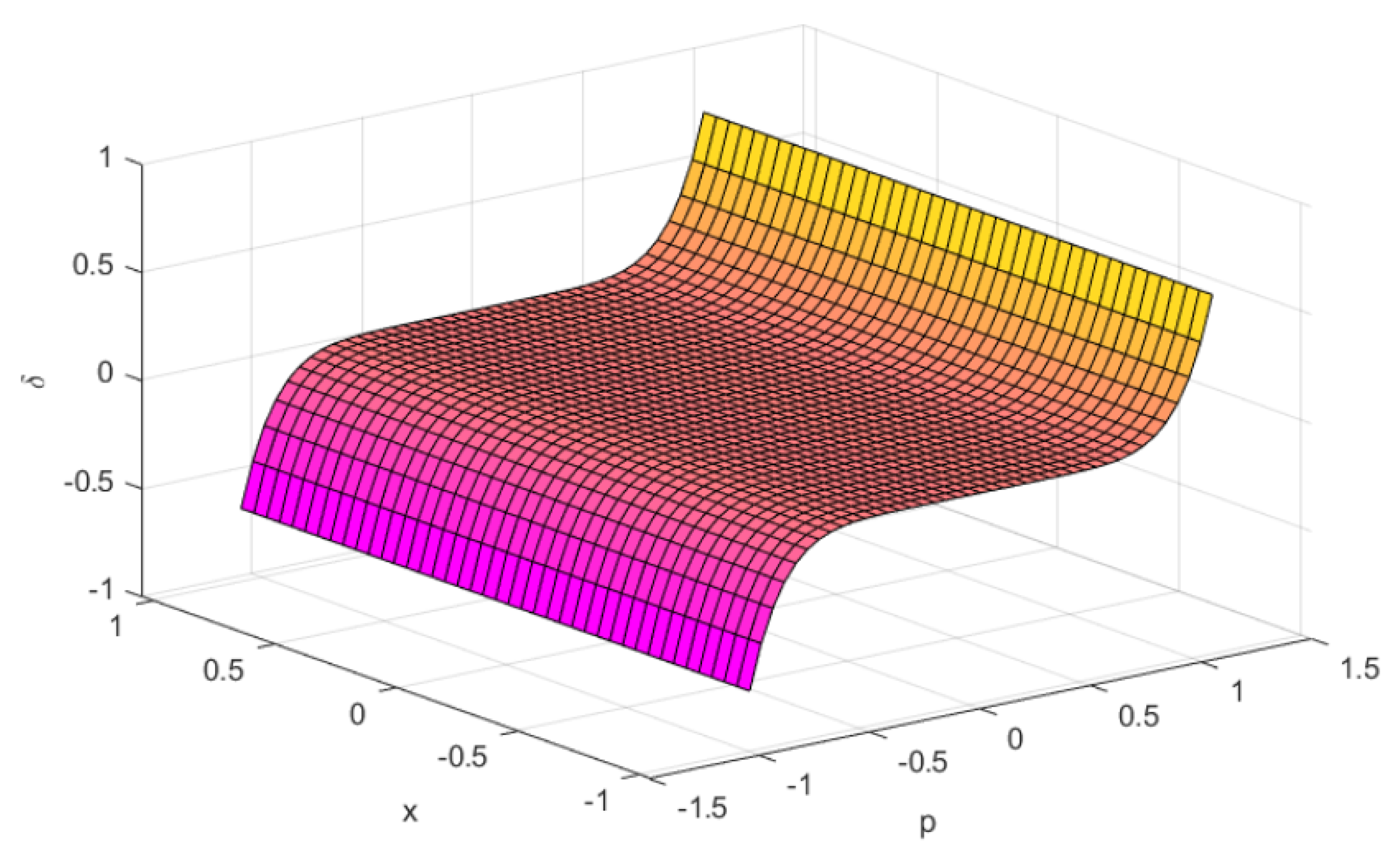

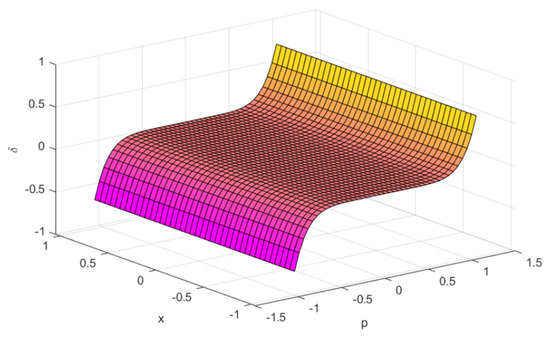

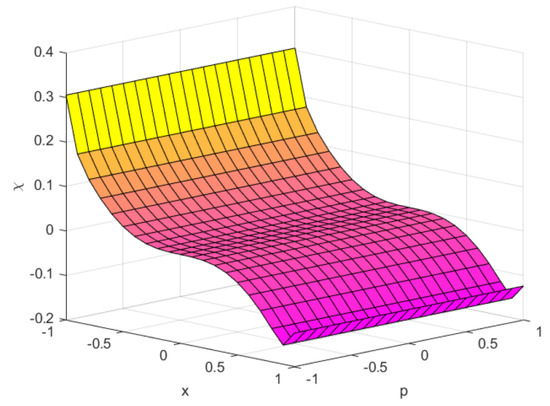

for which at the above equation may not be nonnegative (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

, and .

Therefore, f is not -bonvex at with the same η.

Finally,

Specifically, at point and at , we find that:

This shows that f is not -invex with the same η.

Example 2.

Let be defined as:

A function is defined as:

Let be given as:

Furthermore, is given by:

Now, we have to claim that f is -bonvex at . For this, we have to prove that

Substituting the values of , and G in the above expression, we obtain:

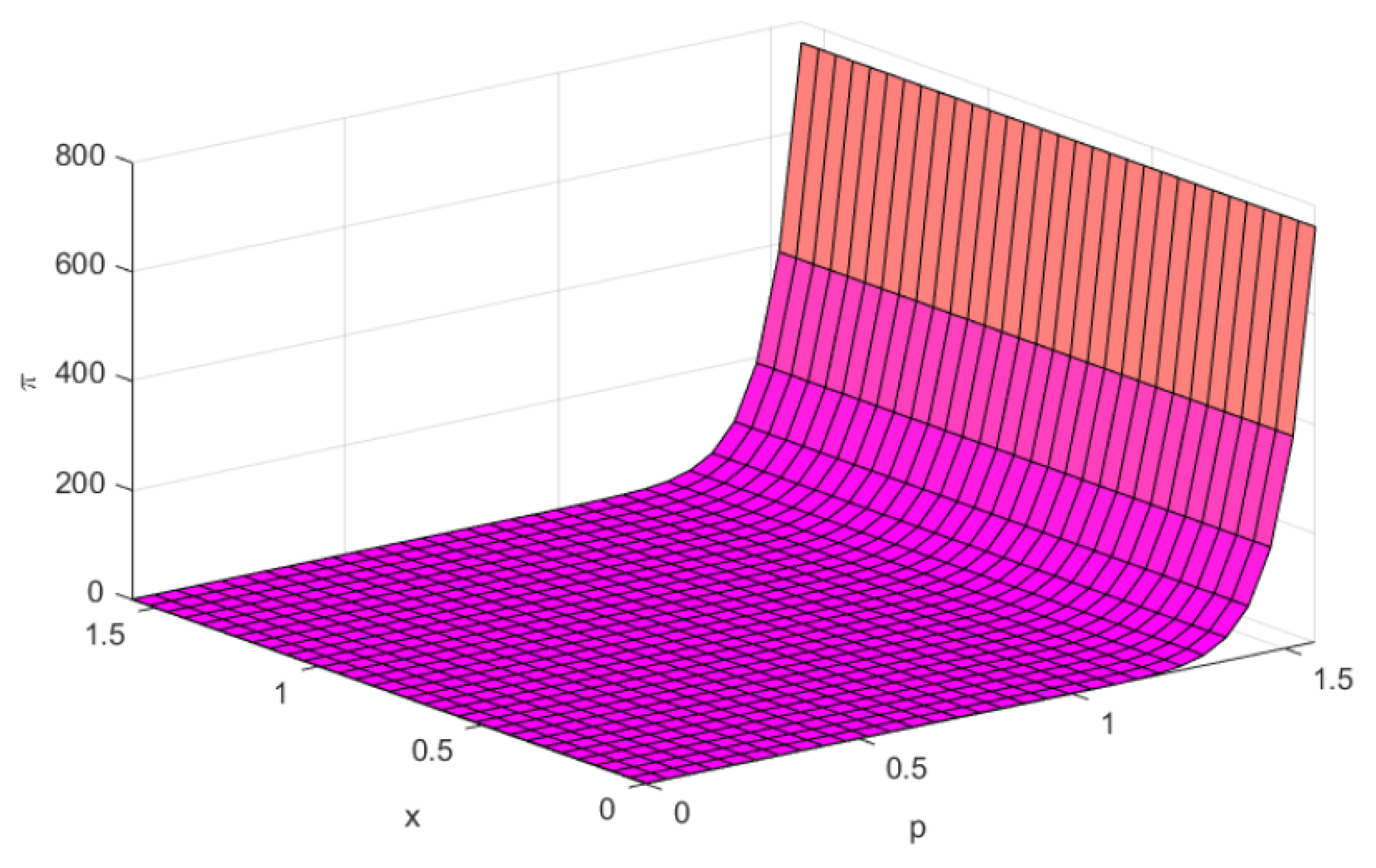

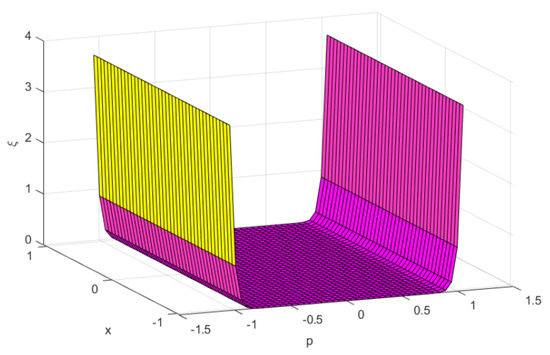

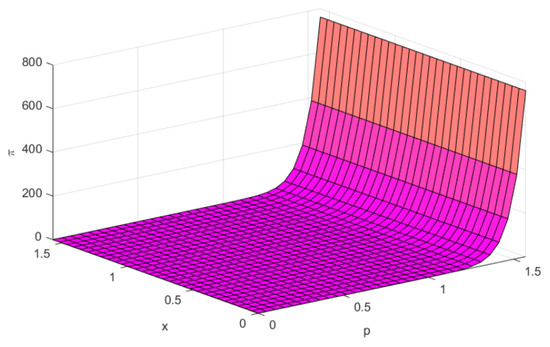

Clearly, from Figure 3, and

Figure 3.

, and .

Therefore, f is -bonvex at with respect to

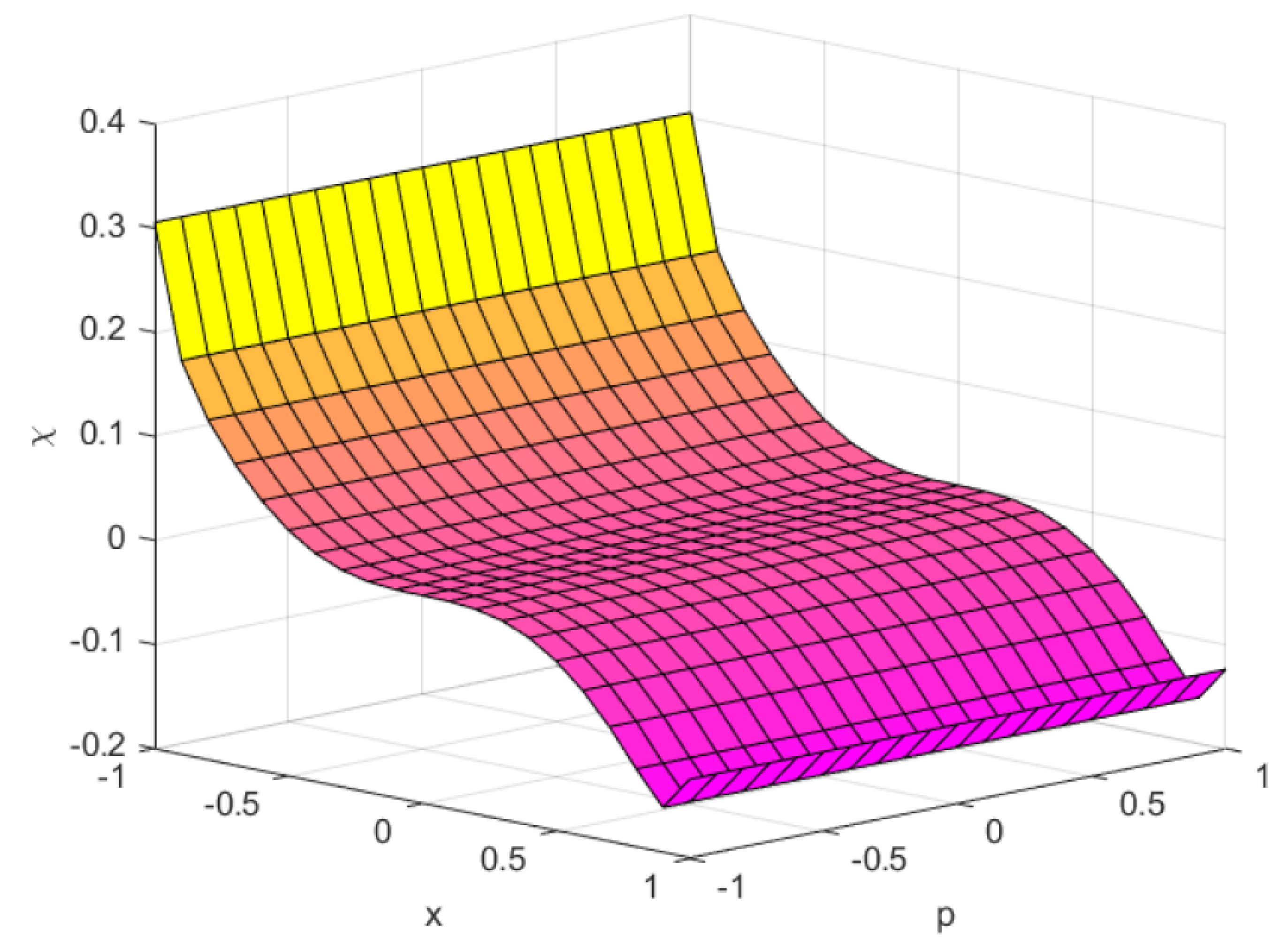

Suppose,

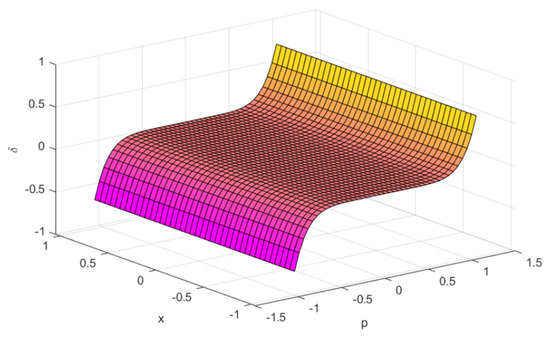

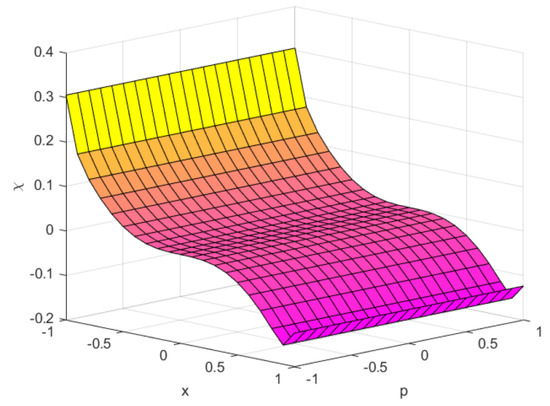

Figure 4.

, and .

This implies that f is not -bonvex at with the same η.

Finally,

At the point , we find that:

Hence, f is not -invex at with the same η.

Example 3.

Let be defined as:

A function is defined as:

Let be given as:

Furthermore, is given by:

Presently, we need to demonstrate that f is -pseudobonvex at concerning η. For this, we have to show that:

Putting the estimations of , and G in the above articulation, we get:

for which at , we obtain

Next,

Substituting the estimations of , and G in the above articulation,

for which at , we obtain Therefore, f is -pseudobonvex at .

Next, consider:

Substituting the values of , and G in the above expression, we obtain:

for which at , we find that

Next,

Substituting the values of , and G in the above expression, we obtain:

for which at , we get Therefore, f is not -pseudobonvex at .

Next, consider:

Similarly, at , we find that Next,

In the same way, at , we find that,

Hence, f is not -pseudoinvex at with the same η.

3. Non-Differentiable Second-Order Symmetric Primal-Dual Pair over Arbitrary Cones

” In this section, we formulate the following pair of second-order non-differentiable symmetric dual programs over arbitrary cones:

(NSOP) Minimize

subject to

:

(NSOD) Maximize

subject to

Theorem 1 (Weak duality theorem).

Let and . Let:

- (i)

- and be -bonvex and -invex at v, respectively, with the same η,

- (ii)

- and be -boncave and -incave at z, respectively, with the same ξ,

- (iii)

- (iv)

Then,

Proof.

From Hypothesis and the dual constraint (5), we obtain

The above inequality follows

Again, from Hypothesis , we obtain

:

and:

Combining the above inequalities, we get

:

Using Inequality (10), it follows that

:

Similarly, using , and primal constraints, it follows that

:

:

Finally, using the inequalities and we have

:

Since , we obtain

:

Hence, the result. □

A non-trivial numerical example for legitimization of the weak duality theorem.

Example 4.

Let be a function given by:

Suppose that and

Further, let be given by:

Furthermore, and

Putting these values in (NSOP) and (NSOD), we get:

(ENSOP) Minimize T() =

subject to

(ENSOD)Maximize W()

subject to

Firstly, we will try to prove that all the hypotheses of the weak duality theorem are satisfied:

is -bonvex at ,

at

Obviously, is -invex at .

is -boncave at and we obtain

at

Naturally, is -invex at .

Obviously, and

Hence, all the assumptions of Theorem 1 hold.

Verification of the weak duality theorem: Let and . To validate the result of the weak duality theorem, we have to show that

Substituting the values in the above expression, we obtain:

At the feasible point, the above expression reduces:

Hence, the weak duality theorem is verified.

Remark 2.

Since every bonvex function is pseudobonvex, therefore the above weak duality theorem for the symmetric dual pair (NSOP) and (NSOD) can also be obtained under -pseudobonvex assumptions.

Theorem 2 (Weak duality theorem).

Let and . Let:

- (i)

- be -pseudobonvex and be -pseudoinvex at v with the same η,

- (ii)

- be -pseudoboncave and be -pseudoinvex at z with the same ξ,

- (iii)

- (iv)

Then,

Proof.

The proof follows on the lines of Theorem 1. □

Theorem 3 (Strong duality theorem).

Let be an optimum of problem (NSOP). Let:

is positive or negative definite,

.

Then, , and there exists such that is an optimum for the problem (NSOD).

Proof.

Since is an efficient solution of (NSOD), therefore by the conditions in [15], such that

:

:

:

:

:

:

Using Hypothesis , we get:

From Equation (15) and Hypothesis we obtain:

Now, suppose . Then, Equation (14) and Hypothesis yield which along with Equations (24) and (25) gives Thus, , a contradiction to Equation (22). Hence, from (23):

:

and now, Equation (24) gives

:

which along with Hypothesis yields:

Therefore, the equation:

As we get:

Therefore, Equation (30) gives:

:

Let Then, as is a closed convex cone. Upon substituting in place of y in (33), we get

:

which in turn implies that for all we obtain

:

Furthermore, by letting and , simultaneously in (33), this yields

:

Using Inequality (31), we get:

Thus, satisfies the dual constraints.

Furthermore, then we obtain . Furthermore, D is a compact convex set.

Theorem 4 (Strict converse duality theorem)

Let be an optimum of problem (NSOD). Let:

is positive or negative definite,

.

Then, , and there exists such that is an optimum for the problem (NSOP).

Proof.

The proof follows on the lines of Theorem 3. □

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we considered a new type of non-differentiable second-order symmetric programming problem over arbitrary cones and derived duality theorems under generalized assumptions. The present work can further be extended to non-differentiable higher order fractional programming problems over arbitrary cones. This will orient the future task of the authors.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this research. The research was carried out by all authors. The manuscript was prepared together and they all read and approved the final version.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the “Deanship of Scientific Research” at King Khalid University for funding this work through research groups program under grant number R.G.P..

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the learned referees whose suggestions improved the present form.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mangasarian, O.L. Second and higher-order duality in nonlinear programming. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1975, 51, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M.A. Second-order invexity and duality in mathematical programming. Opsearch 1993, 3, 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ojha, D.B. On second-order symmetric duality for a class of multiobjective fractional programming problem. Tamkang J. Math. 2009, 43, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jayswal, A.; Prasad, A.K. Second order symmetric duality in non-differentiable multiobjective fractional programming with cone convex functions. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 45, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayswal, A.; Stancu-Minasian, I.M.; Kumar, D. Higher-order duality for multiobjective programming problem involving (F,α,ρ,d)-V-type-I functions. J. Math. Model. Algorithms 2014, 13, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suneja, S.K.; Srivastava, M.K.; Bhatia, M. Higher order duality in multiobjective fractional programming with support functions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Mishra, L.N.; Mishra, V.N. Duality relations for a class of a multiobjective fractional programming problem involving support functions. Am. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 8, 294–311. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, R.; Mishra, V.N.; Tomar, P. Duality relations for second-order programming problem under (G,αf)-bonvexity assumptions. Asian-Eur. J. Math. 2020, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannelli, A.; Ruggieri, M.; Speciale, M.P. Exact and numerical solutions of time-fractional advection-diffusion equation with a nonlinear source term by means of the Lie symmetries. Nonlinear Dyn. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avriel, M.; Diewert, W.E.; Schaible, S.; Zang, I. Optimality Conditions of G-Type in Locally Lipchitz Multiobjective Programming; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Antcza, T. New optimality conditions and duality results of G-type in differentiable mathematical programming. Nonlinear Anal. 2007, 66, 1617–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antczak, T. On G-invex multiobjective programming. Part I Optim. J. Glob. Optim. 2009, 43, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.M.; Kim, D.S.; Kim, M.H. Optimality conditions of G-type in locally Lipchitz multiobjective programming. Vietnam J. Math. 2014, 40, 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X. Sufficiency in multiobjective programming under second-order B-(p,r)-V-type Ifunctions. J. Interdiscip. Math. 2014, 17, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumelle, S. Optimality conditions of G-type in locally Lipchitz multiobjective programming. Vietnam J. Math. 1981, 6, 159–172. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).