Temper the Specialist Nurses Heterogeneity in the Interest of Quality Practice and Mobility—18 EU Countries Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

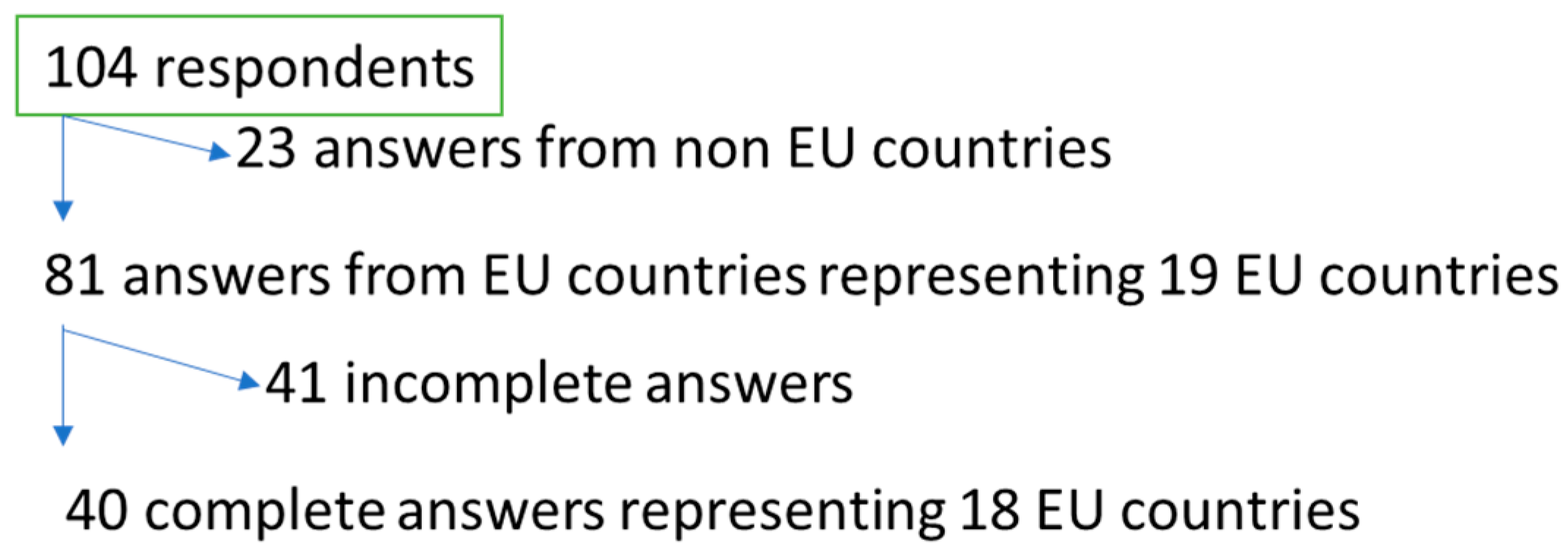

2.2. Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Research Instruments

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.1.1. Countries’ and Respondents’ Characteristics

3.1.2. Educational Level

3.1.3. Autonomy and Responsibility

3.1.4. Suggestions for the SN Profession

3.2. Qualitative Research Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Affara, F. ICN Framework of Competencies for the Nurse Specialist; International Council of Nurses: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dury, C.; Hall, C.; Danan, J.L.; Mondoux, J.; Aguiar Barbieri-Figueiredo, M.C.; Costa, M.A.; Debout, C. Specialist nurse in Europe: Education, regulation and role. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2014, 61, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begley, C.; Elliott, N.; Lalor, J.; Coyne, I.; Higgins, A.; Comiskey, C.M. Differences between clinical specialist and advanced practitioner clinical practice, leadership, and research roles, responsibilities, and perceived outcomes (the SCAPE study). J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 1323–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, M.; McCoy, M.A.; Burson, R. Clinical nurse specialists: Then, now, and the future of the profession. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2013, 27, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidall, C.; Barlow, H.; Crowe, M.; Harrison, I.; Young, A. Clinical nurse specialists: Essential resource for an effective NHS. Br. J. Nurs. 2011, 20, S23–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulcini, J.; Jelic, M.; Gul, R.; Loke, A.Y. An international survey on advanced practice nursing education, practice, and regulation. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2010, 42, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roussou, E.; Iacovou, C.; Georgiou, L. Development of a structured on-site nursing program for training nurse specialists in rheumatology. Rheumatol. Int. 2012, 32, 1685–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowling, M.; Beauchesne, M.; Farrelly, F.; Murphy, K. Advanced practice nursing: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2013, 19, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant-Lukosius, D.; Dicenso, A. A framework for the introduction and evaluation of advanced practice nursing roles. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 48, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnwell, R.; Daly, W.M. Advanced nursing practitioners in primary care settings: An exploration of the developing roles. J. Clin. Nurs. 2003, 12, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, M.; Fagerberg, I.; Wahlberg, A.C. The knowledge desired by emergency medical service managers of their ambulance clinicians—A modified Delphi study. Int. Emerg.Nurs. 2017, 34, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wihlborg, J.; Edgren, G.; Johansson, A.; Sivberg, B. Reflective and collaborative skills enhances ambulance nurses’ competence—A study based on qualitative analysis of professional experiences. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2017, 32, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R. Nurses who work in the ambulance service. Emerg Nurse 2012, 20, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J. Change is in the air. Br. J. Nurs. 2016, 25, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranchal, A.; Jolley, M.J.; Keogh, J.; Lepiesová, M.; Rasku, T.; Zeller, S. The challenge of the standardization of nursing specializations in Europe. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2015, 62, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Specialist Nurses Organisations. Competences of the Nurse Specialist (NS): Common Plinth of Competences for a Common Training Framework of Each Specialty; European Specialist Nurses Organisations: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tunnicliff, S.A.; Piercy, H.; Bowman, C.A.; Hughes, C.; Goyder, E.C. The contribution of the HIV specialist nurse to HIV care: A scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 3349–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Network for Nurses Organisations. Recommendations for a European framework for specialist nursing education. EDTNA/ERCA 2003, 29, 186–187. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2013/55/EU. Directive 2013/55/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 November 2013 Amending Directive 2005/36/EC on the Recognition of Professional Qualifications and Regulation (EU) No 1024/2012 on Administrative Cooperation through the Internal Market Information System (‘The IMI Regulation’). Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/%20LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:354:0132:0170:en:PDF (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- European Higher Education Area. ECTS Users’ Guide 2015. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/da7467e6-8450-11e5-b8b7-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- European Commission. The European Qualifications Framework: Supporting Learning, Work and Cross-Border Mobility. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018H1210(01)&from=EN (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koff, S.Z. Nursing in the European Union: Anatomy of a Profession, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2005/36/EC. Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on the Recognition of Professional Qualifications. Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2005:255:TOC (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Directive 2011/24/EU. Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 on the Application of Patients’ Rights in Cross-Border Healthcare. Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32011L0024&qid=1635091251739 (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Directive 2018/958/EU. Directive (EU) 2018/958 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 June 2018 on a Proportionality Test before Adoption of New Regulation of Professions. Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2018:173:TOC (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Collin, S.M.; de Vries, G.; Lönnroth, K.; Migliori, G.B.; Abubakar, I.; Anderson, S.R.; Zenner, D. Tuberculosis in the European Union and European Economic Area: A survey of national tuberculosis programmes. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, 1801449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J.C.; Baumann, J.; Schmollgruber, S. Does improved postgraduate capacity shift the balance of power for nurse specialists in a low-income country: A mixed methods study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 2969–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, J.; Curry, K. Improving Heart Failure Outcomes: The Role of the Clinical Nurse Specialist. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 2016, 39, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakimowicz, M.; Williams, D.; Stankiewicz, G. A systematic review of experiences of advanced practice nursing in general practice. BMC Nurs. 2017, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mayo, A.M. Time to Define the DNP Capstone Project. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2017, 31, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Council of Nurses. The Role and Identity of the Regulator: An International Comparative Study; ICN Regulation Series; International Council of Nurses: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Decock, N.; Friganovic, A.; Kurtovic, B.; Oomen, B.; Crombez, P.; Willems, C. Temper the Specialist Nurses Heterogeneity in the Interest of Quality Practice and Mobility—18 EU Countries Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030435

Decock N, Friganovic A, Kurtovic B, Oomen B, Crombez P, Willems C. Temper the Specialist Nurses Heterogeneity in the Interest of Quality Practice and Mobility—18 EU Countries Study. Healthcare. 2022; 10(3):435. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030435

Chicago/Turabian StyleDecock, Nico, Adriano Friganovic, Biljana Kurtovic, Ber Oomen, Patrick Crombez, and Christine Willems. 2022. "Temper the Specialist Nurses Heterogeneity in the Interest of Quality Practice and Mobility—18 EU Countries Study" Healthcare 10, no. 3: 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030435

APA StyleDecock, N., Friganovic, A., Kurtovic, B., Oomen, B., Crombez, P., & Willems, C. (2022). Temper the Specialist Nurses Heterogeneity in the Interest of Quality Practice and Mobility—18 EU Countries Study. Healthcare, 10(3), 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030435