Change in Growth Status and Obesity Rates among Saudi Children and Adolescents Is Partially Attributed to Discrepancies in Definitions Used: A Review of Anthropometric Measurements

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

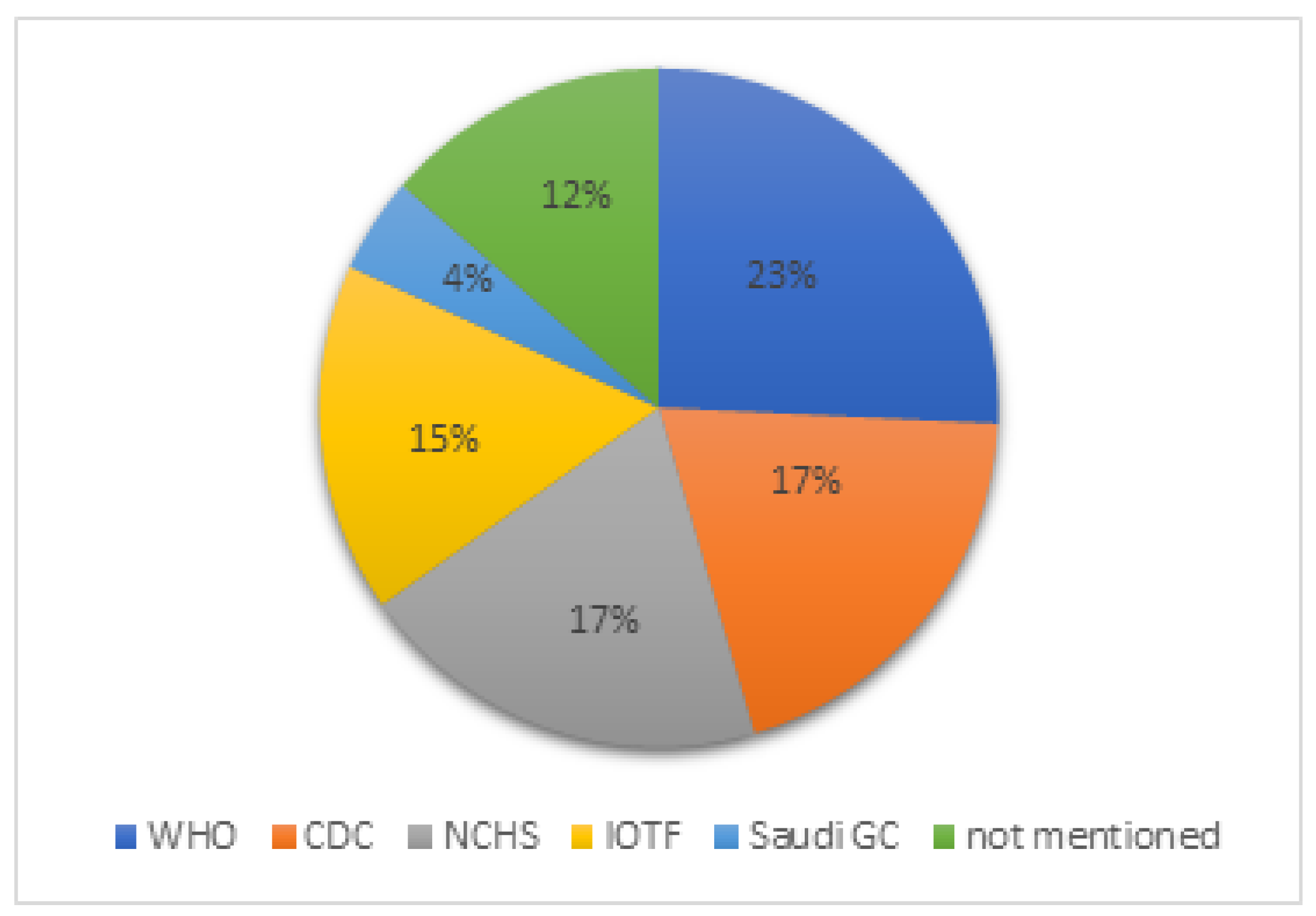

3. International and National Guidelines of Anthropometrics Used in Saudi Children

3.1. World Health Organization

3.2. The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC)

3.3. The International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) BMI Cutoffs

3.4. International Diabetes Federation (IDF)

3.5. The Saudi National Guidelines

4. Results: Anthropometrics Assessed in Saudi Children/Adolescents

4.1. Non-Traditional Measurements

4.2. Assessment of Growth Status in Studies Targeting Saudi Children

| No. | Author, Year (Reference) | Regions | Population Age | Sample n | Anthropometrics Assessed | Anthropometric Assessment Definition (e.g., WHO, CDC, NCHS…) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children Studies | |||||||

| 1. | Attallah et al., 1990 [52] | Asir | 0–24 months | 4520 | Supine length, weight and head circumference | Compared to Wadi Turaba infants and to Europeans | No access to the paper, just the abstract. The need for national growth standards to assess the growth status of Saudi children was highlighted |

| 2. | Wong and Al-Frayh 1990 [53] | Riyadh | Preschool children | 6623 | Weight, height, head and chest circumference and triceps skinfold | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 3 | Al-Hazzaa 1990 [54] | Riyadh | 6–14 years | 1169 | Height, weight, grip strength, chest, triceps, subscapular skinfold thickness | NCHS | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. Figures of comparison were conducted between Saudi children and American and British populations |

| 4. | Al-Omair 1991 [55] | Riyadh | Newborns | 4498 | Weight, height, head circumference | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 5. | Al-Othaimeen 1991 [56] | 10 cities | Birth– 90 years | 933 | Weight, height, weight for height, height for age | NCHS | PhD thesis. |

| 6. | Al-sekait et al., 1992 [57] | All regions | School children | Weight, height, height for age, weight by age | NCHS | No access to the paper, just the abstract | |

| 7. | Jan 1992 [58] | Jeddah | Newborns | 325 | Weight, supine length, fronto-occipital head circumference, chest circumference, triceps skinfold thickness | Compared to national and international populations | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. Normal anthropometric standards are presented for Saudi newborns born at sea level (Jeddah) |

| 8. | Magbool et al., 1993 [59] | Dammam, Al-Khobar, Qatif and Al-Hassa | 6–16 years | 21,638 | Weight, height | NCHS | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 9. | Abolfotouh et al., 1993 [60] | Aseer | 1–60 months | 1168 | Weight, height | NCHS | The study adjusted the international growth curves for local use in Saudi preschool children |

| 10. | Kordy M 1993 [61] | Jeddah | 1–18 | 3286 | Weight, height and mid-arm circumference | Compared to European children | Saudi children are shorter in height and lighter in weight than European children |

| 11. | Alfrayh and Bamgboye 1993 [62] | Riyadh | 0–5 years | 3795 | Weight, height, weight for height, weight for age, height for age | NCHS/CDC | Saudi Arabian children are slightly shorter and thinner than their American counterparts |

| 12. | Alfrayh et al., 1993 [63] | Riyadh | 0–5 years | 3795 | Weight, height | WHO | Anthropometric measurement methods mentioned. The standard physical growth chart for Saudi Arabian preschool children was designed |

| 13. | Chung 1994 [64] | Dammam, Al-Khobar | 6–16 years | 21,638 | Weight, height | NCHS | A microcomputer program for predicting percentile of height and weight by age for Saudi and US children aged 6–16 years was designed based on Magbool et al. data [59] |

| 14. | Al-fawaz et al., 1994 [65] | Riyadh | 6–24 months | 400 | Weight, height, height for age, weight for height, weight for age | Compared to American reference population | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. The WHO software ‘ANTHRO’ was used. |

| 15. | Al-Eissa et al., 1995 [66] | Riyadh | infants | 4578 | Birth weight was collected within 24 h after birth | Normal birthweight-controls | Referenced the anthropometric measurement method |

| 16. | Madani et al., 1995 [67] | Taif | infants | 952 | Weight, height, arm circumference, skinfold thickness | Control infants >2500 g | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 17. | Al-Nuaim et al., 1996 [68] | All regions | 6- 18 years | 9061 | Weight, height, BMI | NCHS/CDC | No access to the paper, just the abstract. Growth charts for males 6–18 y old were created |

| 18. | Lawoyin 1997 [69] | Tabuk | infants | 528 | Birth weight | Compared to controls | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 19. | Al-Nuaim and Bamgboye 1998 [70] | 5 regions | 6–11 years | 4154 | Weight and height, weight for height, height for age and weight for age | NCHS/CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. Growth charts for males 6–11 y old were created |

| 20. | Al-Mazrou et al., 2000 [35] | 5 regions | 0–5 years | 24,000 | Weight and height | NCHS | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. Growth charts for children 0–5 years were created |

| 21. | Hashim and Moawed 2000 [71] | Riyadh | Newborns | 500 | Maternal anthropometrics and newborn weight | Compared to controls | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 22. | Alshammari et al., 2001 [72] | Riyadh | 6–17 years | 1848 children 2927 adults | Weight, Height, BMI | NHANES | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 23. | Al-Hazzaa 2001 [73] | Riyadh | 7–15 years | 137 | Weight, height, BMI, skinfolds, % body fat | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 24. | Al-Jassir et al., 2002 [74] | Riyadh | <5 years | 21,507 | Weight, Height | NCHS | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 25. | El-Hazmi and Warsy 2002 [75] | 5 regions | 1–18 years | 12,701 | Weight, Height | Cutoffs of BMI based on Cole et al. [25] | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 26. | Al-Mazrou et al., 2003 [76] | 5 regions | 0–5 years | 23,821 | Weight, height and head circumference | NCHS | The study compared the national growth monitoring data with NCHS growth standards, which was used in KSA. The study concluded “significant difference between the national growth monitoring data and the NCHS data, so it is important to use the national figures to avoid the drawbacks of NCHS standards” |

| 27. | Bamgboye and Al-Nahedh 2003 [77] | Northwestern | <3 years | 332 | Weight, height | NCHS/WHO | No access to the paper, just the abstract. The pattern of growth was negatively deviated compared to NCHS/WHO |

| 28. | Al-Amoud et al., 2004 [36] | 5 regions | 0–5 years | 23,821 | Weight, height, head circumference | The study developed national growth charts from the national standards derived. Smoothed national growth standards with 5 and 7 percentiles were created and overcame the regional and the urban and rural variations | |

| 29. | Al-Shehri et al., 2005 [78] | Abha and Baish | Newborns | 5500 | Birthweight, crown-to-heel length and head circumference | NCHS/CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. The anthropometry of newborns was less than that of the reference population. |

| 30. | Al-Shehri et al., 2005 [79] | Abha | Newborns | 6035 | Birthweight, crown-to-heel length and head circumference | The study constructed intrauterine percentile growth curves for body weight, length and head circumference for local use in a high-altitude area of Saudi Arabia | |

| 31. | Al-Shehri et al., 2005 [80] | Abha | 0–24 months | 5426 | Weight, crown-toheel supine length, head circumference | NCHS | The study established growth reference standards for infants in the high-altitude Aseer region of southwestern Saudi Arabia. Abha infants in the present study were significantly smaller in all growth parameters than the NCHS |

| 32. | Al-Shehri et al., 2006 [81] | Abha | 3–18 years | 13,580 | Weight, height, BMI | NCHS | The study standardized growth parameters for Saudi children (3–18 years) living at high altitude in Aseer region |

| 33. | Al-Saeed et al., 2006 [82] | Al-Khobar | 6–17 years | 2239 | Weight, Height, BMI | Cutoffs of BMI based on Cole et al. [25] and the CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 34. | Abou-Zeid et al., 2006 [83] | Taif | School children from grade 1–6 | 465 | Weight, height, weight for age, height for age and BMI for age | WHO/NCHS | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 35. | Al-Rowaily et al., 2007 [84] | Riyadh | 4–8 years | 6207 | Weight, height, BMI | NCHS | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. Saudi children were more similar to Americans than to other Saudi children in different areas of Saudi Arabia |

| 36. | Al-Hazzaa 2007 [85] | Jeddah | Preschool children | 224 | Weight, height, BMI, triceps and subscapular skinfolds, %fat, fat mass, fat free mass, FM index | Based on Slaughter et al. [86] | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 37. | Al-Hazzaa 2007 [87] | Riyadh | 6–14 years | 1784 | Weight, height, skinfold thickness, BMI, % fat, lean body mass | Based on several references | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 38. | El-Mouzan et al., 2007 [29] | All regions, | birth–19 years | 35,279 | Weight, height, head circumference | Format of NCHS and CDC growth charts was adopted | The study established updated reference growth charts for Saudi children and adolescents. Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 39. | El-Mouzan et al., 2008 [38] | All regions | birth–19 years [29] | 35,279 | Weight, height, head circumference | CDC growth charts | The study compared between the CDC and Saudi growth charts. There were major differences between the two growth charts. The study concluded “use of the 2000 CDC growth charts for Saudi children and adolescents increases the prevalence of undernutrition, stunting, and wasting” |

| 40. | Amin et al., 2008 [88] | Al-Hassa | Primary school children | 1278 | Weight, height, BMI | Cutoffs of BMI based on Cole et al. [25] | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 41. | Alam 2008 [89] | Riyadh | female school children | 1072 | Weight, height, BMI | Cutoffs of BMI based on Cole et al. [25] | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 42. | El-Mouzan et al., 2008 [90] | All regions | children were from [35] | 40,940 | Weight, height | Compared growth data collected in 1994–1995 and 2004–2005 | Anthropometric measurement methods were referred to in the studies. Evaluated the trend of nutritional status over 10 years. Improvement in Saudis’ nutritional status and a tendency toward overweight and obesity indicate the significance of growth chart update on regular basis |

| 43. | Al-Hashem 2008 [91] | Aseer | 12–71 months | 1041 | Weight, height | WHO/NCHS | The study compared between PEM children in low and high-altitude regions. Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 44. | Khalid 2008 [92] | Southwest | 6–15 years | 912 | Weight, height, | WHO/NCHS | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 45. | Al-Herbish et al., 2009 [30] | All regions | 0–19 years | 35,275 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO/CDC | The study established BMI curves with 10 percentiles that can be used for reference purposes for Saudi children and adolescents. In higher percentiles, Saudi children had equal or higher than Western children |

| 46. | El-Mouzan et al., 2009 [93] | [29] | birth–18 years | 19,131 | Weight, height, BMI, head circumference | Compared between regions | The study found significant differences in growth between regions of Saudi Arabia |

| 47. | El-Mouzan et al., 2009 [37] | All regions | <5 years | 15,516 | Weight, height | A multinational sample selected by the WHO | WHO and Saudi growth standards were used for Saudi children and compared to each other. The study concluded “The use of the WHO standards in Saudi Arabia and possibly in other countries of similar socioeconomic status increases the prevalence of undernutrition, stunting, and wasting”. |

| 48. | El-Mouzan et al., 2010 [94] | All regions | <5 years | 7390 | Weight, height | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned [95]. The higher the education level of the head of the household, the lower the prevalence of malnutrition in their children |

| 49. | El-Mouzan et al., 2010 [96] | All regions | <5 years | 15,516 | Weight, height | NCHS/WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. The study indicated significant regional disparities in prevalence of malnutrition in SA, with the highest in the southwestern region |

| 50. | El-Mouzan et al., 2010 [97] | All regions [29] | <5 years | 15,516 | Weight, height | Saudi growth charts/WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. The study reported the prevalence of malnutrition in SA |

| 51. | Alwasel et al., 2011 [98] | Unizah | newborns | 967 | Weight, head circumference, chest circumference and body length at birth | the effect of Ramadan fasting on birth weight | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned. |

| 52. | Al-Hazzani et al., 2011 [99] | Riyadh | newborns | 186 | Weight | NICHD | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 53. | Warsy et al., 2011 [100] | Riyadh | newborns | 151 | Weight, height, BMI | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 54. | Batterjee et al., 2013 [101] | Makkah | 6–15 years | 1553 | Height, head circumference | NCHS | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 55. | Wahabi et al., 2013 [102] | Riyadh | newborns | 3426 | Weight, length and head circumference | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 56. | Wahabi et al., 2013 [103] | Riyadh | newborns | 3231 | Weight, length and head circumference | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 57. | Bukhari 2013 [104] | Makkah | 6–13 years | 165 | Weight, height, BMI | NHANES-II | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 58. | Al-Saleh et al., 2014 [105] | Al-Kharj | newborns | 1578 | Weight, height, head circumference, crown-to-heel length | 10th percentiles as cutoffs for dichotomizing birth anthropometric measures | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 59. | AlKarimi et al., 2014 [106] | Jeddah | 6–8 years | 417 | Weight, height, height for age, weight for age, BMI for age | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 60. | Alwasel et al., 2014 [107] | Baish | newborns | 321 | Weight, crown-to-heel length, circumferences of the head, chest and thigh | Associations between placental measurements and neonatal anthropometrics | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 61. | Al-Shehri 2014 [108] | Makkah | 6–12 years | 258 | Weight, height | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 62. | Munshi et al., 2014 [109] | Jeddah | infants | 387 | Weight, length, head circumference | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 63. | Albuali 2014 [110] | Al-Ahsa | 6–12 years | 213 | Weight, height, BMI, waist and hip circumference, waist-to-hip ratio | IOTF/CDC | Anthropometric measures followed the protocols of the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry |

| 64. | Al-Mohaimeed et al., 2015 [111] | Al-Qassim | 6–10 years | 874 | Weight, height, BMI, %body fat | WHO | Anthropometric measurement methods mentioned |

| 65. | Al-Muhaimeed et al., 2015 [112] | Al-Qassim | 6–10 years | 874 | Weight, height, BMI | Cole et al. [25] | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 66. | Shaik et al., 2016 [33] | All regions | <5 years | 15,601 | Weight, height, BMI, head circumference | LMS (lambda, mu, sigma) methodology | The study produced growth references for Saudi preschool children |

| 67. | El-Mouzan et al., 2016 [113] | All regions | 5–18 years | 19,299 | Weight, height | LMS methodology | The study produced growth reference for Saudi school-age children and adolescents |

| 68. | El-Mouzan et al., 2016 [114] | All regions | 5–18 years | 19,299 | Weight for age, height for age, BMI for age | LMS and z-score reference | The study produced growth reference for Saudi school-age children and adolescents |

| 69. | Al-Qurashi et al., 2016 [115] | Al-Khobar | Newborns | 476 | Weight, length | CDC/WHO | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 70. | Farsi et al., 2016 [116] | Jeddah | 7–10 years | 914 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | Several references | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 71. | Wyne et al., 2016 [117] | Riyadh | 6–11 years | 61 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO/IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 72. | Bhayat et al., 2016 [118] | Al-Madinah | 12 years | 419 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 73. | Kensara and Azzeh 2016 [119] | Makkah | Infants | 300 | Weight, length and head circumference | Several references | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 74. | AlKushi and Alsawy 2016 [120] | Makkah | Infants | 200 | Weight, length, head circumference | Cutoffs of birth weight with no reference | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 75. | Khalid et al., 2016 [121] | Aseer | Newborns | 25 | Weight, length, body circumferences and skinfold thicknesses | Compared newborn anthropometrics between low and high altitude | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 76. | Eid et al., 2016 [122] | Jeddah | 2–18 years | 643 | Birth weight, height | CDC and several references | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 77. | Bakhiet et al., 2016 [123] | Riyadh | 6–12 years | 1812 | Height, head circumference | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 78. | El-Mouzan et al., 2017 [34] | All regions | 0–60 months | 15,601 | Weight, height, head circumference | Compared Saudi Z-scores with WHO and CDC | The study established Z-score growth reference data for Saudi preschool children and growth charts |

| 79. | Quadri et al., 2017 [124] | Jazan | 5–15 years | 360 | Weight, height, BMI | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 80. | AlSulaibikh et al., 2017 [125] | Dammam | 7 days–13 years | 527 | Weight | determine the accuracy of the Broselow tape on estimating body weights | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 81. | AlShammari et al., 2017 [126] | Hail | 2–18 years | 1420 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 82. | Alsubaie 2017 [127] | Al-Baha | 7–12 years | 725 | Weight, height, BMI | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned and not clear if it was self-report |

| 83. | Al-Kutbe et al., 2017 [128] | Makkah | 8–11 years | 266 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 84. | Saleh et al., 2017 [129] | Al-Ahsa | 7–15 years | 240 | Weight, height, BMI | Saudi growth charts | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 85. | Al-agha and Mahjoub 2018 [130] | Western | 4–13 years | 306 | Weight, height, BMI | CDC/NHANES II | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 86. | Belal et al., 2018 [131] | Taif | Newborn | 1468 | Weight, height, BMI, head circumference | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 87. | Sebiany et al., 2018 [132] | Dammam | 6–12 years | 851 | Weight, height, mid-arm circumference and triceps skinfold thickness | Harvard standards and Saudi growth charts | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 88. | Shaban et al., 2018 [133] | Jazan | 6–12 years | 240 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 89. | Eldosouky et al., 2018 [134] | Al-Madinah | Children | 294 | Weight, height, BMI, waist and hip circumferences | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 90. | Habibullah et al., 2018 [135] | Qassim | 4–10 years | 171 | Weight, height, BMI | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 91. | Fakeeh et al., 2019 [136] | Jazan | 6–13 years | 300 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 92. | Mohtasib et al., 2019 [40] | Riyadh | Newborns-14 years | 950 | Weight, height, BMI, body surface area | Saudi growth charts | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned. The study established normal growth curves for renal length in relation to sex, age, body weight, height, BMI and body surface area of healthy children in Riyadh |

| 93. | Al-Hussaini et al., 2019 [137] | Riyadh | 6–16 years | 7930 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 94. | Alahmari et al., 2019 [138] | Abha | 6–16 years | 200 | Weight, height, BMI, hand dimensions | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 95. | Nasim et al., 2019 [139] | Riyadh | 6–14 years | 481 | Weight, height, BMI | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 96. | Mosli R 2020 [140] | Jeddah | 3–5 years | 209 | Weight, height, BMI Z-score | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 97. | Alghadir et al., 2020 [141] | Not mentioned | 8–18 years | 500 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | Compared Saudis and expatriates | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 98. | El-Gamal et al., 2020 [142] | Jeddah | Preschool | 748 | Weight, height, BMI, | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 99. | Alissa et al., 2020 [143] | Jeddah | 5–15 years | 200 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 100. | Alturki et al., 2020 [144] | Riyadh | 9–12 years | 1023 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 101. | Gohal et al., 2020 [145] | Jazan | <5 years | 440 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 102. | Kamel et al., 2021 [146] | Hail | 6–12 years | 571 | Weight, height, BMI, skinfold thickness | Based on references | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 103. | Elsayed and Said 2021 [147] | Wadi aldawaser | 10–12 years | 150 | Weight, height, arm circumference, BMI, Triceps skinfold | Jellife 1966 [148] | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 104. | Hijji et al., 2021 [149] | All regions | 10–19 years | 12,463 | Weight, height, BMI | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 105. | Gudipaneni et al., 2021 [150] | Aljouf | 12–14 years | 302 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| Adolescent Studies | |||||||

| 106. | Abahussain N 1999 [151] | Al-Khobar | girls 12–19 years | 676 | Weight, height, BMI | NHANES-I | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 107. | Abalkhail and Shawky 2002 [152] | Jeddah | 10–19 years | 2737 | Weight, height, triceps skin fold thickness, mid-arm circumference, BMI | NHANES-I | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 108. | Abalkhail et al., 2002 [153] | Jeddah | 9–21 years | 2860 | Weight, height, BMI | NHANES-I | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 109. | Al-Rukban 2003 [154] | Riyadh | Boys 12–20 years | 894 | Weight, height, BMI | NHANES | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 110. | Al-Almaie 2005 [155] | Al-Khobar | 1766 | Weight, Height, BMI | NHANES and IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned | |

| 111. | Al-Emran et al., 2007 [156] | Riyadh | 9–18 years | 1053 | Height | CDC/NHCS | The study provided growth reference values in body height and determined the specific age at peak height velocity for Saudi male and female adolescences in Riyadh. The study concluded that the use of CDC/NCHS height standards is not appropriate to be used in Saudi children |

| 112. | Farahat et al., 2007 [157] | Western, Northern and Eastern | 12–19 years | 1454 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO/NCHS | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 113. | Al-Hazzaa 2007 [158] | All regions | Three studies [57,68] | Weight, height, BMI | BMI was plotted at the 50th and 90th percentiles | The study examined the trends in BMI of Saudi male adolescents between 1988 and 1996 from 3 nationally representative samples | |

| 114. | Almuzaini 2007 [159] | Riyadh | 11–19 | 44 | Weight, height, BMI, Subscapular, triceps, thigh and calf skinfolds | Not available | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 115. | Mahfouz et al., 2008 [160] | Abha | boys 11–19 years | 2696 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 116. | Bawazeer et al., 2009 [161] | Riyadh | adolescents | 5877 | Weight, height, BMI, waist-hip ratio | Based on a reference | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 117. | El-Mouzan et al., 2010 [162] | Representative sample | 0–19 years | 35,279 | Weight, height, head circumference, BMI | compared between Saudi males and females | Anthropometric measurement reference mentioned. The study determined the pattern and magnitude of differences in growth between boys and girls according to age |

| 118. | El-Mouzan et al., 2010 [39] | Representative sample [29] | 5–18 years | 19,317 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO/CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 119. | Al-Oboudi 2010 [163] | Riyadh | Girls 9–13 years | 120 | Weight, height, BMI | Not available | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 120. | Washi and Ageib 2010 [164] | Jeddah | 13–18 years | 239 | Weight, height, skinfold thicknesses, BMI | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 121. | Al-Daghri et al., 2010 [165] | Riyadh | 5–17 years | 964 | Weight, height, waist, hip, sagittal abdominal diameter (SAD) | Cutoffs based on Cole et al. [25] | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. The study established SAD cutoffs and their association with obesity |

| 122. | Abahussain 2011 [166] | Al-Khobar | 15–19 years | 721 | Weight, height, BMI | NHANES-I | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. The study determined the change in BMI among adolescent Saudi girls living in Al-Khobar between 1997 and 2007 |

| 123. | El-Mouzan et al., 2012 [167] | 3 regions, representative sample [29] | 5–17 years | 9018 | Height | Compared stature between regions | Anthropometric measurement method: referred to the main study, a representative sample. The study assessed regional prevalence of short stature |

| 124. | Al-Attas et al., 2012 [168] | Riyadh | 10–17 years | 948 | Weight, height, waist and hip circumference, BMI, Waist-to-hip ratio, SAD | Based on Cole et al. [25] | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. The study concluded “The use of SAD may not be practical for use in the paediatric clinical setting” |

| 125. | Al-Nakeeb et al., 2012 [169] | Al-Ahsa | 15–17 years | 1138 | Weight, height, BMI | IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned; the study compared between Saudi and British anthropometrics |

| 126. | El-Mouzan et al., 2012 [170] | 3 regions | 2–17 years | 11,112 | Weight, height, BMI | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. The study assessed regional variation in prevalence of overweight and obesity |

| 127. | Al-Hazzaa et al., 2012 [171] | Al-Khobar, Jeddah, Riyadh | 14–19 years | 2906 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, waist/height ratio | IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 128. | Al-Jaaly 2012 [172] | Jeddah | 13–18 years | 1519 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-height-ratio | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 129. | ALHazzaa et al., 2013 [173] | Riyadh and Al-Khobar | 14–18 years | 1648 | Weight, height, BMI | IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. The study compared between Saudi and British adolescents |

| 130. | Al-Ghamdi 2013 [174] | Riyadh | 9–14 years | 397 | Weight, height, BMI | IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 131. | Al-Hazzzaa et al., 2014 [175] | Al-Khobar Jeddah Riyadh | 14–19 years | 2908 | Weight, height, waist circumference, BMI | IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 132. | Duncan et al., 2014 [176] | Al-Khobar and Riyadh | 14–18 years | 1648 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, waist to height ratio | IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned; Saudi anthropometric compared to British |

| 133. | Al-Hazzaa 2014 [177] | Riyadh, Jeddah and Al-Khobar | 15–19 years | 2852 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 134. | AlBuhairan et al., 2015 [178] | All regions-representative sample | Saudi adolescents | 12,575 | Weight, height, BMI | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned. The national adolescent health study “Jeeluna” identified the health needs and status of adolescents in KSA. |

| 135. | Al-Daghri et al., 2015 [179] | Riyadh | 12–17 years | 1690 | Weight, height, waist and hip circumference | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 136. | Al-Sobayel et al., 2015 [180] | Riyadh, Jeddah, Al-Khobar | 14–19 years | 2888 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 137. | Alenazi et al., 2015 [181] | Arar | Saudi male adolescents | 523 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 138. | Al-agha et al., 2015 [182] | Jeddah | 6–14 years | 586 | Height | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 139. | Shaik et al., 2016 [183] | Riyadh | 9–16 years | 304 | Weight, height, BMI, waist and hip circumference | CDC/WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 140. | Moradi-Lakeh et al., 2016 [184] | All regions | 15–25 years | 2382 | Weight, height, BMI | Not mentioned | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 141. | Al-agha et al., 2016 [185] | Jeddah | 2–18 years | 541 | Weight, height, BMI | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 142. | Hothan et al., 2016 [186] | Jeddah | 11–18 years | 401 | Weight, height, BMI | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 143. | Al-Daghri et al., 2016 [187] | Riyadh | 12–18 years | 4549 | Weight, height, BMI | Based on Cole et al. [25] | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 144. | Al-Agha et al., 2016 [188] | Jeddah | 2–18 years | 653 | Weight, height, BMI | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 145. | Alswat et al., 2017 [189] | Taif | 12–18 years | 424 | Weight, height, BMI | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 146. | Omar et al., 2017 [190] | Taif | 12–15 years | 701 | Weight, height, BMI, waist and hip circumferences, skinfold thickness, % body fat | IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 147. | Nasreddine et al., 2018 [191] | All regions | Adolescents | 1047 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | WHO/CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 148. | AlTurki et al., 2018 [192] | Riyadh | 16–18 years | 384 | Weight, height, skinfold thickness and waist and hip circumferences | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method not mentioned |

| 149. | Al-Hazzaa and Albawardi 2019 [193] | Riyadh, Jeddah, Al-Khobar | 15–19 years | 2888 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | IOTF | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 150. | Fatima et al., 2019 [194] | Arar | 15–19 years | 322 | Weight, height, BMI | CDC | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 151. | Moukhyer et al., 2019 [195] | Jazan | 12–19 years | 502 | Weight, height | WHO | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

| 152. | Alowfi et al., 2021 [196] | Jeddah | 12–19 years | 172 | Weight, height, BMI, waist circumference | Saudi growth charts | Anthropometric measurement method mentioned |

5. Recommendations for Establishing Saudi Guidelines of Anthropometric Measurements and Directions for Future Work in Line with the Saudi 2030 Vision

Individuals with Health Conditions and Disabilities

| Recommendations—Children/Adolescents | Directions for Future Work |

|---|---|

| 1. Use preterm infants’ growth standards for preterm infants if preterm infants are well-nourished and free from environmental and socioeconomic constraints on growth until 64 weeks postmenstrual age [202] | Develop a protocol to be used in all hospitals and to be endorsed by the Saudi MOH |

| 2. Update the Saudi growth charts (SGC) using the WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) guideline for children under 5 years old, Arabic version [15] (see Table S3) |

|

| 3. Explore non-traditional anthropometrics to define obesity in Saudi children and develop specific cutoffs [206] | Non-traditional anthropometrics, such as chest and wrist circumference, body mass abdominal index etc. [206] can be used in the case of limited equipment available and may help prevent childhood obesity by early detection |

| 4. Update the SGC for children/adolescents ages 5–19 years [209] (see Table S3) |

|

| Recommendations for Individuals with Health Conditions and Disabilities | Directions for Future Work |

| 5. Update SGC for Down syndrome [213] | Update, publish the Saudi cutoffs and endorse them to be used by the Saudi MOH |

| 6. Create simplified equations to calculate body surface area in Saudi children and adults from large representative Saudi samples [43,47]. | Equations to calculate body surface area are created from anthropometrics (e.g., weight, height). Body surface area is a major factor in the determination of the course of treatment and drug dosage and can be used by physicians in different medical conditions (e.g., transplantation, predict chances of survival in burn patients, nephrotic syndrome) [214] |

| |

| 7. Create a national birth defect registry [211] | The data from the registry will help in identifying the prevalence, trends, the causes of birth defects and conducting preventive measures. |

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vision 2030. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/ (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Bah, S. How feasible is the life expectancy target in the Saudi Arabian vision for 2030? East. Mediterr. Health J. 2018, 24, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthropometry. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthropometry (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Dictionary Anthropometry. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/anthropometry (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Casadei, K.; Kiel, J. Anthropometric Measurement; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022.

- CDC. Clinical Growth Charts. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/clinical_charts.htm (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Green Corkins, K. Nutrition-focused physical examination in pediatric patients. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2015, 30, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scafoglieri, A.; Clarys, J.P.; Cattrysse, E.; Bautmans, I. Use of anthropometry for the prediction of regional body tissue distribution in adults: Benefits and limitations in clinical practice. Aging Dis. 2014, 5, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tyrovolas, S.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Alghnam, S.A.; Alhabib, K.F.; Almadi, M.A.H.; Al-Raddadi, R.M.; Bedi, N.; El Tantawi, M.; Krish, V.S.; Memish, Z.A.; et al. The burden of disease in Saudi Arabia 1990–2017: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e195–e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. The Heavy Burden of Obesity; OECD Health Policy Studies; OECD: Paris, France, 2019; ISBN 9789264330047. [Google Scholar]

- Aljaadi, A.M.; Alharbi, M. Overweight and Obesity Among Saudi Children: Prevalence, Lifestyle Factors, and Health Impacts. In Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, S.S.; Berry, D.C. The Child Obesity Epidemic in Saudi Arabia: A Review of the Literature. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2017, 28, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zalabani, A.H. Online sources of health statistics in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2011, 32, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Anthropometry procedures manual. In National Health and Nutrition Examinatory Survey (NHANES); Centres for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Recommendations for Data Collection, Analysis and Reporting on Anthropometric Indicators in Children under 5 Years Old; World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WHO; Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group; WHO Child Growth. Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2006, 95, 76–85. [Google Scholar]

- de Onis, M. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO STEPS Surveillance Manual; WHO Global Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 1–453. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Anthro Survey Analyser and Other Tools. Available online: https://www.who.int/toolkits/child-growth-standards/software (accessed on 19 September 2021).

- CDC. Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Kuczmarski, R.J.; Ogden, C.L.; Guo, S.S.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Flegal, K.M.; Mei, Z.; Wei, R.; Curtin, L.R.; Roche, A.F.; Johnson, C.L. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002, 31, 1–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Onis, M.; Garza, C.; Onyango, A.W.; Borghi, E. Comparison of the WHO Child Growth Standards and the CDC 2000 Growth Charts. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cole, T.J.; Lobstein, T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 2012, 7, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, T.J.; Flegal, K.M.; Nicholls, D.; Jackson, A.A. Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: International survey. BMJ 2007, 335, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cole, T.J.; Bellizzi, M.C.; Flegal, K.M.; Dietz, W.H. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. Br. Med. J. 2000, 320, 1240–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rolland-Cachera, M.F. Towards a simplified definition of childhood obesity? A focus on the extended IOTF references. Pediatr. Obes. 2012, 7, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmet, P.; Alberti, K.G.M.; Kaufman, F.; Tajima, N.; Silink, M.; Arslanian, S.; Wong, G.; Bennett, P.; Shaw, J.; Caprio, S. The metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents—An IDF consensus report. Pediatr. Diabetes 2007, 8, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perona, J.S.; Schmidt-RioValle, J.; Fernández-Aparicio, Á.; Correa-Rodríguez, M.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; González-Jiménez, E. Waist Circumference and Abdominal Volume Index Can Predict Metabolic Syndrome in Adolescents, but only When the Criteria of the International Diabetes Federation are Employed for the Diagnosis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Mouzan, M.I.; Al-Herbish, A.S.; Al-Salloum, A.A.; Qurachi, M.M.; Al-Omar, A.A. Growth charts for Saudi children and adolescents. Saudi Med. J. 2007, 28, 1555–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Al Herbish, A.S.; El Mouzan, M.I.; Al Salloum, A.A.; Al Qureshi, M.M.; Al Omar, A.A.; Foster, P.J.; Kecojevic, T. Body mass index in Saudi Arabian children and adolescents: A national reference and comparison with international standards. Ann. Saudi Med. 2009, 29, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Saudi Ministry of Health. The Growth Charts for Saudi Children and Adolescents (Birth to 60 months). Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/HealthAwareness/EducationalContent/BabyHealth/Documents/Intermediate1CompatibilityMode.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- The Saudi Ministry of Health. The Growth Charts for Saudi Children and Adolescents (5–19 y). Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/HealthAwareness/EducationalContent/BabyHealth/Documents/Intermediate2CompatibilityMode.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Shaik, S.A.; El-Mouzan, M.I.; Al-Salloum, A.A.; Al-Herbish, A.S. Growth reference for Saudi preschool children: LMS parameters and percentiles. Ann. Saudi Med. 2016, 36, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Mouzan, M.I.; Shaffi, A.; Al Salloum, A.; Alqurashi, M.M.; Al Herbish, A.; Al Omer, A. Z-score growth reference data for Saudi preschool children. Ann. Saudi Med. 2017, 37, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Mazrou, Y.; Al-Amood, M.M.; Khoja, T.; Al-Turki, K.; El-Gizouli, S.E.; Tantawi, N.E.; Khalil, M.H.; Aziz, K.M.S. Standardized national growth chart of 0–5 year-old Saudi children. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2000, 46, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Al-Amoud, M.M.; Al-Mazrou, Y.Y.; El-Gizouli, S.E.; Khoja, T.A.; Al-Turki, K.A. Clinical growth charts for pre-school children. Saudi Med. J. 2004, 25, 1679–1682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El Mouzan, M.I.; Foster, P.J.; Al Herbish, A.S.; Al Salloum, A.A.; Al Omar, A.A.; Qurachi, M.M.; Kecojevic, T. The implications of using the world health organization child growth standards in Saudi Arabia. Nutr. Today 2009, 44, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Mouzan, M.I.; Al Herbish, A.S.; Al Salloum, A.A.; Foster, P.J.; Al Omar, A.A.; Qurachi, M.M.; Kecojevic, T. Comparison of the 2005 growth charts for Saudi children and adolescents to the 2000 CDC growth charts. Ann. Saudi Med. 2008, 28, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Mouzan, M.I.; Foster, P.J.; Al Herbish, A.S.; Al Salloum, A.A.; Al Omer, A.A.; Qurachi, M.M.; Kecojevic, T. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Saudi children and adolescents. Ann. Saudi Med. 2010, 30, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mohtasib, R.S.; Alshamiri, K.M.; Jobeir, A.A.; Saidi, F.M.A.; Masawi, A.M.; Alabdulaziz, L.S.; Hussain, F.Z. Bin Sonographic measurements for kidney length in normal Saudi children: Correlation with other body parameters. Ann. Saudi Med. 2019, 39, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Herbish, A.S. Standard penile size for normal full term newborns in the Saudi population. Saudi Med. J. 2002, 23, 314–416. [Google Scholar]

- Nwoye, L.O.; Al-Shehri, M.A. The body surface area of Saudi newborns. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2005, 80, 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Alwasel, S.H.; Abotalib, Z.; Aljarallah, J.S.; Osmond, C.; Alkharaz, S.M.; Alhazza, I.M.; Harrath, A.; Thornburg, K.; Barker, D.J.P. Secular increase in placental weight in Saudi Arabia. Placenta 2011, 32, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Omar, M.T.A.; Alghadir, A.; Al Baker, S. Norms for hand grip strength in children aged 6–12 years in Saudi Arabia. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2015, 18, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.S. Take a deeper look into body surface area. Nursing 2019, 49, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nwoye, L.O.; Al-Shehri, M.A. A formula for the estimation of the body surface area of Saudi male adults. Saudi Med. J. 2003, 24, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Wirths, W.; Hamdan, M.; Hayati, M.; Rajhi, H. [Nutritional status, food consumption and food supply of studies in Saudi Aribia. I. Anthropometric data]. Z. Ernahrungswiss. 1977, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebai, Z.A.; Reinke, W.A. Anthropometric measurements among pre-school children in Wadi Turaba, Saudi Arabia. J. Trop. Pediatr. 1981, 27, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebai, Z.A.; Sabaa, H.M.A.; Shalabi, S.; Bayoumi, R.A.; Miller, D. Health in Khulais villages, Saudi Arabia: An educational project. Med. Educ. 1981, 15, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.A.; Swailem, A.; Taha, S.A. Nutritional status of preschool children in central Saudi Arabia. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1982, 12, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Frayh, A.R.; Jabar, F.A.; Wong, S.S.; Wong, H.Y.H.; Bener, A. Growth and Development of Saudi Infant and Pre-School Children. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 1987, 107, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attallah, N.; Jibnel, S.; Campbel, J. Patterns of growth of Saudi boys and girls aged 0–24 months, Asir region, with a note on their rates of growth: A 1988 view. Saudi Med. J. 1990, 11, 466–472. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.S.; Al-Frayh, A.R. Growth Patterns in Saudi Arabian Children. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 1990, 110, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Anthropometric measurements of Saudi boys aged 6–14 years. Ann. Hum. Biol. 1990, 17, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omair, A.O.I. Birth order, socioeconomic status and birth height of Saudi infants. J. R. Soc. Health 1991, 111, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Othaimeen, A.I. Food Habits, Nutritional Status and Disease Patterns in Saudi Arabia; University of Surrey (United Kingdom): Guildford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sekait, M.; Al-Nasser, A.; Bamgboye, E. The growth pattern of schoolchildren in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 1992, 13, 234–239. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, M.Y. Anthropometric standards in normal Saudi newborns at sea level. Ann. Saudi Med. 1992, 12, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Magbool, G.; Kaul, K.K.; Corea, J.R.; Osman, M.; Al-Arfaj, A. Weight and height of Saudi children six to 16 years from the Eastern Province. Ann. Saudi Med. 1993, 13, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abolfotouh, M.A.; Abu-Zeid, H.A.; Badawi, I.A.; Mahfouz, A.A. A method for adjusting the international growth curves for local use in the assessment of nutritional status of Saudi pre-school children. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 1993, 68, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kordy, M. Comparison of some anthropometric measurements for Saudi children with national and international values. Bull. Alex. Fac. Med. 1993, 29, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- al Frayh, A.S.; Bamgboye, E.A. The Growth Pattern of Saudi Arabian Pre- School Children in Riyadh Compared to NCHS/CDC Reference Population. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 1993, 113, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Frayh, A.S.; Bamgboye, E.A.; Moussa, M.A.A. The standard physical growth chart for Saudi Arabian preschool children. Ann. Saudi Med. 1993, 13, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chung, S.J. Formulas expressing relationship among age, height and weight, and percentile in Saudi and US children aged 6–16 years. Int. J. Biomed. Comput. 1994, 37, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-fawaz, I.M.; Bamgboye, E.A.; Al-eissa, Y.A. Factors influencing linear growth in Saudi Arabian children aged 6–24 months. J. Trop. Pediatr. 1994, 40, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Eissa, Y.A.; Ba’Aqeel, H.S.; Haque, K.N.; AboBakr, A.M.; Al-Kharfy, T.M.; Khashoggi, T.Y.; Al-Husain, M.A. Determinants of Term Intrauterine Growth Retardation: The Saudi Experience. Am. J. Perinatol. 1995, 12, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madani, K.A.; Masrat, H.A.; Al Nowaisser, A.A.; Khashoggi, R.H.; Abalkhal, B.A. Low birth weight in the Taif Region, Saudi Arabia. East. Mediterr. Health J. 1995, 1, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nuaim, A.R.; Bamgboye, E.A.; Al-Herbish, A. The pattern of growth and obesity in Saudi Arabian male school children. Int. J. Obes. 1996, 20, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Lawoyin, T.O. The relationship between maternal weight gain in pregnancy, hemoglobin level, stature, antenatal attendance and low birth weight. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 1997, 28, 873–876. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nuaim, A.R.; Bamgboye, E.A. Comparison of the anthropometry of Saudi Arabian male children aged 6–11 years with the NCHS/CDC reference population. Med. Princ. Pract. 1998, 7, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, T.J.; Moawed, S.A. The relation of low birth weight to psychosocial stress and maternal anthropometric measurements. Saudi Med. J. 2000, 21, 649–654. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shammari, S.A.; Khoja, T.; Gad, A. Community-based study of obesity among children and adults in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Food Nutr. Bull. 2001, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Development of maximal cardiorespiratory function in Saudi boys. A cross-sectional analysis. Saudi Med. J. 2001, 22, 875–881. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jassir, M.S.; El Bashir, B. Anthropometric measurements of infants and under five children in Riyadh City. Nutr. Health 2002, 16, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hazmi, M.A.F.; Warsy, A.S. The prevalence of obesity and overweight in 1–18-year-old Saudi children. Ann. Saudi Med. 2002, 22, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mazrou, Y.Y.; Al-Amoud, M.M.; El-Gizouli, S.E.; Khoja, T.; Al-Turki, K.; Tantawi, N.E.; Khalil, M.K.; Aziz, K.M. Comparison of the growth standards between Saudi and American children aged 0–5 years. Saudi Med. J. 2003, 24, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bamgboye, E.A.; Al-Nahedh, N. Factors associated with growth faltering in children from rural Saudi Arabia. Afr. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2003, 32, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Shehri, M.A.; Abolfotouh, M.A.; Dalak, M.A.; Nwoye, L.D. Birth anthropometric parameters in high and low altitude areas of Southwest Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2005, 26, 560–565. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shehri, M.A.; Abolfotouh, M.A.; Nwoye, L.O.; Eid, W. Construction of intrauterine growth curves in a high altitude area of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2005, 26, 1723–1727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Shehri, M.A.; Abolfotouh, M.A.; Khan, M.Y.; Nwoye, L.O. Growth standards for urban infants in a high altitude area of Saudi Arabia. Biomed. Res. 2005, 16, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shehri, M.A.; Mostafa, O.A.; Al-Gelban, K.; Hamdi, A.; Almbarki, M.; Altrabolsi, H.; Luke, N. Standards of growth and obesity for Saudi children (aged 3–18 years) living at high altitudes. West Afr. J. Med. 2006, 25, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Saeed, W.Y.; Al-Dawood, K.M.; Bukhari, I.A.; Bahnassy, A. Prevalence and socioeconomic risk factors of obesity among urban female students in Al-Khobar city, Eastern Saudi Arabia, 2003. Obes. Rev. 2007, 8, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Zeid, A.H.; Abdel-Fattah, M.M.; Al-Shehri, A.S.A.; Hifnaway, T.M.; Al-Hassan, S.A.A. Anemia and nutritional status of schoolchildren living at Saudi high altitute area. Saudi Med. J. 2006, 27, 862–869. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rowaily, M.; Al-Mugbel, M.; Al-Shammari, S.; Fayed, A. Growth pattern among primary school entrants in King Abdul-Aziz Housing City for National Guard in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2007, 28, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M.; Al-Rasheedi, A.A. Adiposity and physical activity levels among preschool children in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2007, 28, 766–773. [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter, M.H.; Lohman, T.G.; Boileau, R.A.; Horswill, C.A.; Stillman, R.J.; Van Loan, M.D.; Bemben, D.A. Skinfold equations for estimations of body fatness in children and youth. Hum. Biol. 1988, 60, 709–723. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Prevalence and trends in obesity among school boys in Central Saudi Arabia between 1988 and 2005. Saudi Med. J. 2007, 28, 1569–1574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amin, T.T.; Al-Sultan, A.I.; Ali, A. Overweight and obesity and their relation to dietary habits and socio-demographic characteristics among male primary school children in Al-Hassa, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Eur. J. Nutr. 2008, 47, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.A. Obesity among female school children in North West Riyadh in relation to affluent lifestyle. Saudi Med. J. 2008, 29, 1139–1144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El-Mouzan, M.I.; Al-Herbish, A.S.; Al-Salloum, A.A.; Al-Omar, A.A.; Qurachi, M.M. Trends in the nutritional status of Saudi children. Saudi Med. J. 2008, 29, 884–887. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Hashem, F.H. The prevalence of malnutrition among high and low altitude preschool children of southwestern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2008, 29, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Is High-Altitude Environment a Risk Factor for Childhood Overweight and Obesity in Saudi Arabia?—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1080603208701790 (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- El Mouzan, M.; Foster, P.; Al Herbish, A.; Al Salloum, A.; Al Omer, A.; Alqurashi, M.; Kecojevic, T. Regional variations in the growth of Saudi children and adolescents. Ann. Saudi Med. 2009, 29, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Mouzan, M.I.; Al-Salloum, A.A.; Al-Herbish, A.S.; Qurachi, M.M.; Al-Omar, A.A. Effects of education of the head of the household on the prevalence of malnutrition in children. Saudi Med. J. 2010, 31, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Waterlow, J.C.; Buzina, R.; Keller, W.; Lane, J.M.; Nichaman, M.Z.; Tanner, J.M. The presentation and use of height and weight data for comparing the nutritional status of groups of children under the age of 10 years. Bull. World Health Organ. 1977, 55, 489–498. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mouzan, M.I.; Al-Herbish, A.S.; Al-Salloum, A.A.; Foster, P.J.; Al-Omar, A.A.; Qurachi, M.M.; Kecojevic, T. Regional disparity in prevalence of malnutrition in Saudi children. Saudi Med. J. 2010, 31, 550–554. [Google Scholar]

- El Mouzan, M.; Foster, P.; Al Herbish, A.; Al Salloum, A.; Al Omar, A.; Qurachi, M. Prevalence of malnutrition in Saudi children: A community-based study. Ann. Saudi Med. 2010, 30, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alwasel, S.H.; Abotalib, Z.; Aljarallah, J.S.; Osmond, C.; Alkharaz, S.M.; Alhazza, I.M.; Harrath, A.; Thornburg, K.; Barker, D.J.P. Sex Differences in birth size and intergenerational effects of intrauterine exposure to Ramadan in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2011, 23, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Hazzani, F.; Al-Alaiyan, S.; Hassanein, J.; Khadawardi, E. Short-term outcome of very low-birth-weight infants in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2011, 31, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warsy, A.S.; Habib, Z.; Addar, M.; Al-Daihan, S.; Alanazi, M. Maternal leptin and glucose: Effect on the anthropometric measurements of the Saudi newborn. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2011, 4, 4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterjee, A.A.; Khaleefa, O.; Ashaer, K.; Lynn, R. Normative data for iq, height and head circumference for children in Saudi Arabia. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2013, 45, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahabi, H.A.; Alzeidan, R.A.; Fayed, A.A.; Mandil, A.; Al-Shaikh, G.; Esmaeil, S.A. Effects of secondhand smoke on the birth weight of term infants and the demographic profile of Saudi exposed women. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wahabi, H.A.; Mandil, A.A.; Alzeidan, R.A.; Bahnassy, A.A.; Fayed, A.A. The independent effects of second hand smoke exposure and maternal body mass index on the anthropometric measurements of the newborn. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bukhari, H.M. Anthropometric Measurements and the Effect of Breakfast Sources in School Achievement, Physical Activity and Dietary Intake for 6–13 Years Old Primary School Children Girls in Makkah City. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2013, 2, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Saleh, I.; Shinwari, N.; Mashhour, A.; Rabah, A. Birth outcome measures and maternal exposure to heavy metals (lead, cadmium and mercury) in Saudi Arabian population. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2014, 217, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkarimi, H.A.; Watt, R.G.; Pikhart, H.; Sheiham, A.; Tsakos, G. Dental caries and growth in school-age children. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e616–e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alwasel, S.H.; Harrath, A.H.; Aldahmash, W.M.; Abotalib, Z.; Nyengaard, J.R.; Osmond, C.; Dilworth, M.R.; Al Omar, S.Y.; Jerah, A.A.; Barker, D.J.P. Sex differences in regional specialisation across the placental surface. Placenta 2014, 35, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlShehri, J. Childhood obesity prevalence among primary schoolboys at Al-Iskan sector, Holy Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public Health 2014, 3, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, A.; Balbeid, O.; Qureshi, N. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Very Low Birth Weight in Infants Born at the Maternity and Children Hospitals in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia during 2012–2013. Br. J. Med. Med. Res. 2014, 4, 4553–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuali, W.H. Evaluation of oxidant-antioxidant status in overweight and morbidly obese Saudi children. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2014, 3, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohaimeed, A.; Ahmed, S.; Dandash, K.; Ismail, M.S.; Saquib, N. Concordance of obesity classification between body mass index and percent body fat among school children in Saudi Arabia. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Muhaimeed, A.A.; Dandash, K.; Ismail, M.S.; Saquib, N. Prevalence and correlates of overweight status among Saudi school children. Ann. Saudi Med. 2015, 35, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Mouzan, M.; Al Salloum, A.; Al Omer, A.; Alqurashi, M.; Al Herbish, A. Growth reference for Saudi school-Age children and adolescents: LMS parameters and percentiles. Ann. Saudi Med. 2016, 36, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Mouzan, M.I.; Al Salloum, A.A.; Alqurashi, M.M.; Al Herbish, A.S.; Al Omar, A. The LMS and Z scale growth reference for Saudi school-age children and adolescents. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qurashi, F.O.; Yousef, A.A.; Awary, B.H. Epidemiological aspects of prematurity in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsi, D.J.; Elkhodary, H.M.; Merdad, L.A.; Farsi, N.M.A.; Alaki, S.M.; Alamoudi, N.M.; Bakhaidar, H.A.; Alolayyan, M.A. Prevalence of obesity in elementary school children and its association with dental caries. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyne, A.H.; Rahman Al-Neaim, B.A.; Al-Aloula, F.M. Parental attitude towards healthy weight screening/counselling for their children by dentists. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2016, 66, 943–946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhayat, A.; Ahmad, M.; Fadel, H. Association between body mass index, diet and dental caries in Grade 6 boys in Medina, Saudi Arabia. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2016, 22, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kensara, O.A.; Azzeh, F.S. Nutritional status of low birth weight infants in Makkah region: Evaluation of anthropometric and biochemical parameters. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2016, 66, 414–417. [Google Scholar]

- Alkushi, A.G.; Sawy, N.A. El Maternal Anthropometric Study of Low Birth Weight Newborns in Saudi Arabia: A Hospital-Based Case-Control Study. Adv. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khalid, M.E.M.; Ahmed, H.S.; Osman, O.M.; Al Hashem, F.H. The relationship of birth weight, body shape and body composition at birth to altitude in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Morphol. 2016, 34, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eid, A.; Omar, A.; Khaled, M.; Ibrahim, M. The Association between Children Born Small for Gestational Age and Short Stature. J. Pregnancy Child Health 2016, 03, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhiet, S.F.A.; Essa, Y.A.S.; Dwieb, A.M.M.; Elsayed, A.M.A.; Sulman, A.S.M.; Cheng, H.; Lynn, R. Correlations between intelligence, head circumference and height: Evidence from two samples in Saudi Arabia. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2017, 49, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri, M.F.A.; Hakami, B.M.; Hezam, A.A.A.; Hakami, R.Y.; Saadi, F.A.; Ageeli, L.M.; Alsagoor, W.H.; Faqeeh, M.A.; Dhae, M.A. Relation between dental caries and body mass index- for-age among schoolchildren of Jazan city, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2017, 18, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALSulaibikh, A.H.; Al-Ojyan, F.I.; Al-Mulhim, K.N.; Alotaibi, T.S.; Alqurashi, F.O.; Almoaibed, L.F.; ALwahhas, M.H.; ALjumaan, M.A. The accuracy of Broselow pediatric emergency tape in estimating body weight of pediatric patients. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, E.; Suneetha, E.; Adnan, M.; Khan, S.; Alazzeh, A. Growth profile and its association with nutrient intake and dietary patterns among children and adolescents in Hail Region of Saudi Arabia. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 5740851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alsubaie, A.S.R. Consumption and correlates of sweet foods, carbonated beverages, and energy drinks among primary school children in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kutbe, R.; Payne, A.; De Looy, A.; Rees, G.A. A comparison of nutritional intake and daily physical activity of girls aged 8-11 years old in Makkah, Saudi Arabia according to weight status. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Albin Saleh, A.A.; Alhaiz, A.S.; Khan, A.R.; Al-Quwaidhi, A.J.; Aljasim, M.; Almubarak, A.; Alqurayn, A.; Alsumaeil, M.; AlYateem, A. Prevalence of Obesity in School Children and Its Relation to Lifestyle Behaviors in Al-Ahsa District of Saudi Arabia. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2017, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Agha, A.E.; Mahjoub, A.O. Impact of body mass index on high blood pressure among obese children in the western region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belal, S.K.M.; Alzahrani, A.K.; Alsulaimani, A.A.; Afeefy, A.A. Effect of parental consanguinity on neonatal anthropometric measurements and preterm birth in Taif, Saudi Arabia. Transl. Res. Anat. 2018, 13, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebiany, A.M.; Hafez, A.S.; Salama, K.F.A.; Sabra, A.A. Association between air pollutants and anthropometric measurements of boys in primary schools in Dammam, Eastern Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2018, 25, 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Shaban, F.; Swaleha, N.; Chandika, R.; Sahlooli, A.; Almaliki, S. Anthropometric Parameters and Its Effects on Academic Performance among Primary School Female Students in Jazan, Saudi Arabia Kingdom. Indian J. Nutr. 2018, 5, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Eldosouky, M.K.; Allah, A.M.A.; AbdElmoneim, A.; Al-Ahmadi, N.S. Correlation between serum leptin and its gene expression to the anthropometric measures in overweight and obese children. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2018, 64, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibullah, M.A.; Alsughier, Z.; Elsherbini, M.S.; Elmoazen, R.A. Caries Prevalence and Its Association with Body Mass Index in Children Aged 4 to 10 Years in Al Dulaymiah Qassim Region of Saudi Arabia-A Pilot Study. Int. J. Dent. Sci. Res. 2018, 6, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fakeeh, M.I.; Shanawaz, M.; Azeez, F.K.; Arar, I.A. Overweight and obesity among the boys of primary public schools of Baish City in Jazan Province, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Indian J. Public Health 2019, 63, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hussaini, A.; Bashir, M.; Khormi, M.; Alturaiki, M.; Alkhamis, W.; Alrajhi, M.; Halal, T. Overweight and obesity among Saudi children and adolescents: Where do we stand today? Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahmari, K.A.; Kakaraparthi, V.N.; Reddy, R.S.; Silvian, P.S.; Ahmad, I.; Rengaramanujam, K. Percentage difference of hand dimensions and their correlation with hand grip and pinch strength among schoolchildren in Saudi Arabia. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2019, 22, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasim, M.; Aldamry, M.; Omair, A.; AlBuhairan, F. Identifying obesity/overweight status in children and adolescents; A cross-sectional medical record review of physicians’ weight screening practice in outpatient clinics, Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosli, R.H. Validation of the Child Feeding Questionnaire among Saudi pre-schoolers in Jeddah city. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghadir, A.H.; Iqbal, Z.A.; Gabr, S.A. Differences among Saudi and expatriate students: Body composition indices, sitting time associated with media use and physical activity pattern. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- El-Gamal, F.M.; Babader, R.; Al-Shaikh, M.; Al-Harbi, A.; Al-Kaf, J.; Al-Kaf, W. Study determinants of increased Z-Score of Body Mass Index in preschool-age children. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alissa, E.M.; Sutaih, R.H.; Kamfar, H.Z.; Alagha, A.E.; Marzouki, Z.M. Relationship between pediatric adiposity and cardiovascular risk factors in Saudi children and adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. 2020, 27, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alturki, H.A.; Brookes, D.S.K.; Davies, P.S.W. Does spending more time on electronic screen devices determine the weight outcomes in obese and normal weight Saudi Arabian children? Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohal, G.; Madkhali, A.M.K.; Darabshi, A.H.M.; Wassly, A.H.A.; Jawahy, M.A.M.; Jaafari, A.A.A.; Mahfouz, M.S. Nutritional status of children less than five years and associated factors in Jazan region, Saudi Arabia. Australas. Med. J. 2020, 13, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, E.; Hussien, H.M.; Alrawaili, S.M. Association between spinal, knee, ankle pain, and obesity in preadolescent female students in Ha’il, Saudi Arabia Corresponding Author: Ehab Mohamed Kamel. Sylwan 2021, 165, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Elsayead, M.A.E.; Said, A.S. A Study of the Relationship between Nutritional Status and Scholastic Achievement among Primary School Students in Wadi Eldawasir City in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 4, 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jellife, D.B. The Assessment of the Nutritional Status of the Community (with Special Reference to Field Surveys in Developing Regions of the World/Derrick B. Jelliffe; Prepared in Consultation with Twenty-Five Specialists in Various Countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Hijji, T.M.; Saleheen, H.; AlBuhairan, F.S. Underweight, body image, and weight loss measures among adolescents in Saudi Arabia: Is it a fad or is there more going on? Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2021, 8, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudipaneni, R.K.; Albilasi, R.M.; HadiAlrewili, O.; Alam, M.K.; Patil, S.R.; Saeed, F. Association of Body Mass Index and Waist Circumference with Dental Caries and Consequences of Untreated Dental Caries Among 12- to 14-Year-old Boys: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abahussain, N.A.; Musaiger, A.O.; Nicholls, P.J.; Stevens, R. Nutritional status of adolescent girls in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Nutr. Health 1999, 13, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abalkhail, B.; Shawky, S. Comparison between body mass index, triceps skin fold thickness and mid-arm muscle circumference in Saudi adolescents. Ann. Saudi Med. 2002, 22, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abalkhail, B.A.; Shawky, S.; Soliman, N.K. Validity of self-reported weight and height among Saudi school children and adolescents. Saudi Med. J. 2002, 23, 831–837. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rukban, M.O. Obesity amond Saudi male adolescents in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2003, 24, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Almaie, S.M. Prevalence of obesity and overweight among Saudi adolescents in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2005, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Emran, S.; Al-Kawari, H.M.; Abdellatif, H.M. Age at maximum growth spurt in body height for Saudi school children aged 9–18 years. Saudi Med. J. 2007, 28, 1718–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Farahat, F.M.; Joshi, K.P.; Al-Mazrou, F.F. Assessment of nutritional status and lifestyle pattern among Saudi Arabian school children. Saudi Med. J. 2007, 28, 1298–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Rising trends in BMI of Saudi adolescents: Evidence from three national cross sectional studies. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 16, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuzaini, K.S. Muscle function in Saudi children and adolescents: Relationship to anthropometric characteristics during growth. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2007, 19, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mahfouz, A.A.; Abdelmoneim, I.; Khan, M.Y.; Daffalla, A.A.; Diab, M.M.; Al-Gelban, K.S.; Moussa, H. Obesity and related behaviors among adolescent school boys in Abha City, Southwestern Saudi Arabia. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2008, 54, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bawazeer, N.M.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Valsamakis, G.; Al-Rubeaan, K.A.; Sabico, S.L.B.; Huang, T.T.K.; Mastorakos, G.P.; Kumar, S. Sleep duration and quality associated with obesity among Arab children. Obesity 2009, 17, 2251–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Mouzan, M.I.; Al Herbish, A.S.; Al Salloum, A.A.; Foster, P.J.; Al Omar, A.A.; Qurachi, M.M.; Kecojevic, T. Pattern of sex differences in growth of Saudi children and adolescents. Gend. Med. 2010, 7, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Oboudi, L.M. Impact of breakfast eating pattern on nutritional status, glucose level, iron status in blood and test grades among upper primary school girls in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Pak. J. Nutr. 2010, 9, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Washi, S.A.; Ageib, M.B. Poor diet quality and food habits are related to impaired nutritional status in 13- to 18-year-old adolescents in Jeddah. Nutr. Res. 2010, 30, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daghri, N.; Alokail, M.; Al-Attas, O.; Sabico, S.; Kumar, S. Establishing abdominal height cut-offs and their association with conventional indices of obesity among Arab children and adolescents. Ann. Saudi Med. 2010, 30, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abahussain, N. Was there a change in the body mass index of Saudi adolescent girls in Al-Khobar between 1997 and 2007? J. Fam. Community Med. 2011, 18, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Mouzan, M.I.; Al Herbish, A.S.; Al Salloum, A.A.; Al Omer, A.A.; Qurachi, M.M. Regional prevalence of short stature in Saudi school-age children and adolescents. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 505709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Attas, O.S.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Alokail, M.S.; Alkharfy, K.M.; Draz, H.; Yakout, S.; Sabico, S.; Chrousos, G. Association of body mass index, sagittal abdominal diameter and waist-hip ratio with cardiometabolic risk factors and adipocytokines in Arab children and adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Al-Nakeeb, Y.; Lyons, M.; Collins, P.; Al-Nuaim, A.; Al-Hazzaa, H.; Duncan, M.J.; Nevill, A. Obesity, physical activity and sedentary behavior amongst British and Saudi youth: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 1490–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- El Mouzan, M.; Al Herbish, A.; Al Salloum, A.; Al Omar, A.; Qurachi, M. Regional variation in prevalence of overweight and obesity in Saudi children and adolescents. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M.; Abahussain, N.A.; Al-Sobayel, H.I.; Qahwaji, D.M.; Musaiger, A.O. Lifestyle factors associated with overweight and obesity among Saudi adolescents. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Jaaly, E. Factors affecting nutritional status and eating behaviours of adolescent girls in Saudi Arabia. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2012, 108, 262–275. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M.; Al-Nakeeb, Y.; Duncan, M.J.; Al-Sobayel, H.I.; Abahussain, N.A.; Musaiger, A.O.; Lyons, M.; Collins, P.; Nevill, A. A cross-cultural comparison of health behaviors between Saudi and British adolescents living in urban areas: Gender by country analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 6701–6720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Ghamdi, S. The association between watching television and obesity in children of school-age in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2013, 20, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M.; Abahussain, N.A.; Al-Sobayel, H.I.; Qahwaji, D.M.; Alsulaiman, N.A.; Musaiger, A.O. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Abdominal Obesity among Urban Saudi Adolescents: Gender and Regional Variations. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2014, 32, 634–645. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, M.J.; Al-hazzaa, H.M.; Al-Nakeeb, Y.; Al-Sobayel, H.I.; Abahussain, N.A.; Musaiger, A.O.; Lyons, M.; Collins, P.; Nevill, A. Anthropometric and lifestyle characteristics of active and inactive saudi and british adolescents. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2014, 26, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Joint associations of body mass index and waist-to-height ratio with sleep duration among Saudi adolescents. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2014, 41, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlBuhairan, F.S.; Tamim, H.; Al Dubayee, M.; AlDhukair, S.; Al Shehri, S.; Tamimi, W.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Magzoub, M.E.; de Vries, N.; Al Alwan, I. Time for an adolescent health surveillance system in Saudi Arabia: Findings from “Jeeluna”. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Al-Daghri, N.M.; Aljohani, N.J.; Al-Attas, O.S.; Al-Saleh, Y.; Wani, K.; Alnaami, A.M.; Alfawaz, H.; Al-Ajlan, A.S.M.; Kumar, S.; Chrousos, G.P.; et al. Non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and other lipid indices vs elevated glucose risk in Arab adolescents. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2015, 9, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sobayel, H.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M.; Abahussain, N.A.; Qahwaji, D.M.; Musaiger, A.O. Gender differences in leisure-time versus non-leisure-time physical activity among Saudi adolescents. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2015, 22, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alenazi, S.A.; Koura, H.M.; Zaki, S.M.; Mohamed, A.H. Prevalence of obesity among male adolescents in Arar Saudi Arabia: Future risk of cardiovascular disease. Indian J. Community Med. 2015, 40, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Agha, A.E.; AlHadadi, A.; Otatwany, B. Early Puberty and its Effect on Height in Young Saudi Females: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatr. Ther. 2015, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, S.A.; Hashim, R.T.; Alsukait, S.F.; Abdulkader, G.M.; AlSudairy, H.F.; AlShaman, L.M.; Farhoud, S.S.; Fouda Neel, M.A. Assessment of age at menarche and its relation with body mass index in school girls of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Asian J. Med. Sci. 2015, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moradi-Lakeh, M.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Tuffaha, M.; Daoud, F.; Al Saeedi, M.; Basulaiman, M.; Memish, Z.A.; Al Mazroa, M.A.; Al Rabeeah, A.A.; Mokdad, A.H. The health of Saudi youths: Current challenges and future opportunities. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Agha, A.E.; Nizar, F.S.; Nahhas, A.M. The association between body mass index and duration spent on electronic devices in children and adolescents in Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hothan, K.A.; Alasmari, B.A.; Alkhelaiwi, O.K.; Althagafi, K.M.; Alkhaldi, A.A.; Alfityani, A.K.; Aladawi, M.M.; Sharief, S.N.; El Desoky, S.; Kari, J.A. Prevalence of hypertension, obesity, hematuria and proteinuria amongst healthy adolescents living in Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daghri, N.M.; Aljohani, N.J.; Al-Attas, O.S.; Al-Saleh, Y.; Alnaami, A.M.; Sabico, S.; Amer, O.E.; Alharbi, M.; Kumar, S.; Alokail, M.S. Comparisons in childhood obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors among urban Saudi Arab adolescents in 2008 and 2013. Child. Care Health Dev. 2016, 42, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Agha, A.E.; Al Baradi, W.R.; Al Rahmani, D.A.; Simbawa, B.M. Associations between Various Nutritional Elements and Weight, Height and BMI in Children and Adolescents. J. Patient Care 2016, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alswat, K.A.; Al-Shehri, A.D.; Aljuaid, T.A.; Alzaidi, B.A.; Alasmari, H.D. The association between body mass index and academic performance. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 217–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, N.A.A.; Elshazley, M.; El Sayed, S.M.; Al-Lithy, A.N.A.; Mohamed, M.; Nabo, H.; Helmy, M.M. Impact of Body Mass Index Changes on Development of Hypertension in Preparatory School Students: A Cross Sectional Study Based on Anthropometric Measurements. Am. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2017, 5, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine, L.; Tamim, H.; Mailhac, A.; AlBuhairan, F.S. Prevalence and predictors of metabolically healthy obesity in adolescents: Findings from the national “Jeeluna” study in Saudi-Arabia. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]