Abstract

This review aims (i) to identify and analyze the physical training programs used for tactical personnel (TP) and (ii) to understand the effects of physical training programs on the health and fitness, and occupational performance of tactical personnel. A literature search used the keywords ‘Physical Training Program’, ‘Police’, ‘Law Enforcement’, and ‘Firefighter’. A total of 23 studies out of 11.508 analyzed were included. All studies showed acceptable methodological quality in assessing physical fitness (PF), and training programs’ effect sizes (Cohen’s d) on PF attributes were calculated. The results showed that physical training programs (duration > four weeks) can improve (medium-to-large effects) (i) measures of physical fitness and (ii) performance in simulations of occupationally specific tasks. This review provides summary information (i) to help select (or adjust) physical training programs for TP and (ii) to clarify the effect of different occupational-specific training interventions on fitness measures and health-related parameters for TP.

1. Introduction

Tactical populations (e.g., police officers, firefighters, and military) have their specific tasks, which are complex, varied in nature, unpredictable, and highly demanding from a physical fitness point of view [1].

This personnel executes, in the performance of their mission, a wide variety of actions, many of which are physical, where they may be required to: stop suspects, run, climb up/downstairs, pull, push, overcome obstacles, chase suspects, and use weapons from a vast panoply of options [2]. To perform these activities, tactical personnel require endurance, strength, speed, agility, and flexibility to undertake their profession [3].

To respond to this large number of actions and perform their mission efficiently, the tactical population (TP) must have a physical fitness (PF) that is up to the enormous challenges of the demanding professions. In addition, it is also of great importance that TP is in good PF condition. Otherwise, they can endanger the safety of the community or even their own safety [4].

There is considerable scientific evidence that the PF of this TP is below the general population and health recommendations [5,6,7]. It has been extensively studied and shown that physical components such as cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, and others are closely related to health parameters and improved quality of life and, consequently, enhanced job skills [8,9,10]. In accordance, a decline in exercise practice has implications for the health of TP, which ultimately impacts the organizations themselves (lower productivity levels [11]), given they are one of their greatest assets.

Nevertheless, there is only one study on physical activity and the application of specific training programs in TP in Portugal. Therefore, this review aims (i) to identify and analyze the most used PF programs for TP and (ii) to understand their impact on the development of PF attributes associated with performing the function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Approach to the Problem

The present work was conducted to identify the PF programs most used in scientific research with PT and to determine their impact on their physical abilities in performing their functions. The guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) model [12] were followed. The present study is exempt from ethical approval because the data came from previously conducted studies for which the authors of each study had obtained approvals.

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Search Strategy

The author identified relevant original works for the literature search for this original work. To do this, literature databases were systematically searched using specific keywords pertinent to the topic, including PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Physical+Training+Program+AND+Police+OR+Law+Enforcement+or+Firefighter&filter=years.2012-2023&size=100, accessed on 7 March 2023) and SPORTDiscus|EBSCO (https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=s3h&bquery=Physical+Training+Program+AND+police+officers+OR+law+enforcement+OR+military+OR+firefighters&cli0=FT&clv0=Y&cli1=DT1&clv1=201201-202212&type=1&searchMode=Standard&site=ehost-live&scope=site”: EBSCOhost Research Databases) (accessed on 14 March 2023).

Databases were selected because they were high-quality, peer-reviewed articles that represented journals relevant to the topic of the study. We used specific terms and filters for the databases searched, which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Databases and relevant search terms.

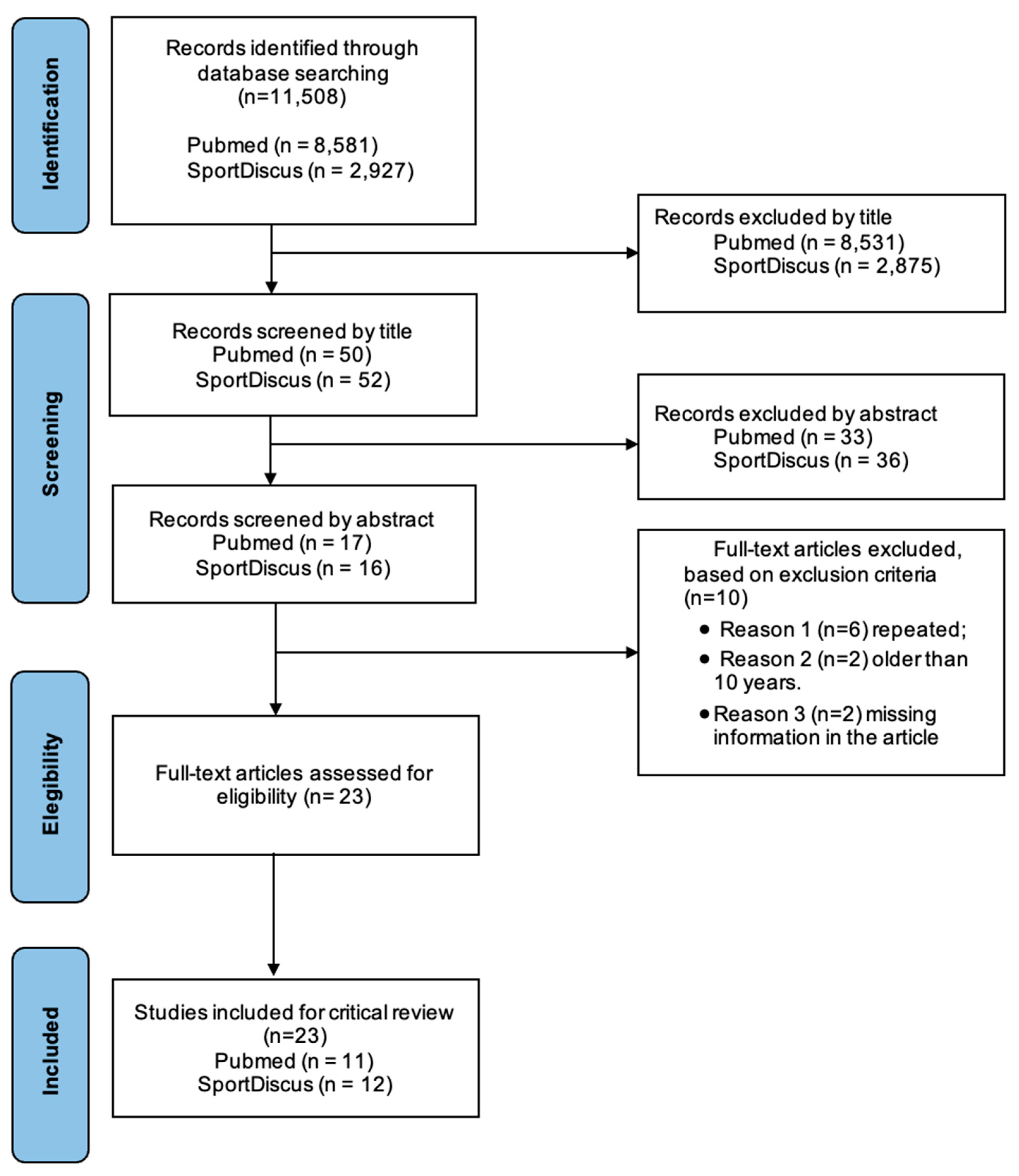

Eligibility criteria were defined and applied to each database to refine the search results. The defined inclusion criteria were individuals from police, fire, or other law enforcement agencies who have participated in a training program. The specified exclusion criteria were: (i) studies older than ten years; (ii) studies examining only body composition; and (iii) instrument development and validity studies. Duplicate studies were removed after all studies were collected. The screening and selection process is described in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) [12].

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram detailing the search process.

2.2.2. Critical Appraisal

To assess the methodological quality of the studies, we used the NHLBI guidelines, which consist of a checklist of 14 questions. Each question can be answered “Yes”, “No”, “Not applicable”, “Not reported”, or “Cannot be determined”. Two authors also guaranteed methodological quality to avoid bias. Table 2 shows the quality of all studies in this review.

Table 2.

NHLBI quality control tool items and study scores (n = 23).

2.2.3. Data Extraction

Afterwards, the articles were critically analysed, and the following information was extracted: authors and year of publication; study population; measurements (PF tests); physical training program; main results/general conclusions. All information is presented in Table 3. In continuation, the mean and standard deviations (SDs) for fitness test results (pre- and post-intervention) in each selected study were used to calculate the effect size (Cohen’s d) and effect size correlation (r) of the physical training programs on fitness measures (note that d and r are positive if the mean difference is in the predicted direction).

Table 3.

The data extraction table, including physical fitness tests and training programs, with key findings.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

A total of 11,508 studies were identified. After being screened by titles, abstracts, and complete text analyses, 23 studies were considered (Table 3). We summarized the screening and selection process in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) and the literature search results [12].

The reviewed studies referred to TP/PO [13,28,30,32], firefighters [15,18,20,22,26,31,34], military [23,33], and cadets/recruits (police [3,16,19,21,25], firefighters [24,27,29] and military [14,17]).

Of the 23 studies, fourteen were realized in the USA [3,13,15,16,18,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,33], two from UAE [19,32], and one from South Africa [14], Brazil [17], Iran [20], Russia [21], Denmark [23], Portugal [31], and China [34].

Eight studies examined male and female participants [3,13,14,16,23,25,26,33], while twelve included only male participants [15,17,18,19,21,22,27,28,29,31,32,34]. Three studies did not report the gender of the participants [20,24,30].

3.2. Physical Fitness Measures

Morphological attributes (e.g., stature, body mass, body mass index—BMI, waist circumferences, hip circumferences, waist-to-height ratio, skinfolds, fat mass—%FM, or lean body mass) were assessed in eleven studies [16,17,19,22,24,27,29,30,31,32,33].

The most-used fitness components assessed were muscular strength (maximal strength, endurance, and power), aerobic capacity, anaerobic capacity (e.g., speed), agility, flexibility, and some specific professional tests, i.e.: (i) maximal muscular strength was measured in almost all studies in different forms, including bench press [3,16,29,33,34], leg press [33], squat [22,34], hex-bar deadlift [28], handgrip strength [3,15,21,25,27,30], and lower-back and leg strength [21,25,27]; (ii) muscular endurance was most measured by push-ups [3,14,16,17,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,29,30,32], sit-ups [3,14,16,17,19,23,25,26,29,30,32], pull-ups [22,24,27], and plank time [22,30]; (iii) muscular power was measured using vertical jump [3,16,25,27,29,34] and seated medicine-ball throw [34] tests; (iv) aerobic capacity measures were performed, a including 2.4-km run (1.5-mile run) [14,16,19,22,24,29,32], 20-m shuttle run [23,25,27,34] and 12-min run/Cooper [17,23,31] tests; (v) anaerobic capacity was measured using Wingate anaerobic [3] or sprint [3,16,28] tests; (vi) agility was tested with a T-test [3,32] and shuttle run [14,21]; (vii) flexibility was measured using the sit-and-reach test [3,15,26,29,30]; and (viii) specific tests were also measured in some studies [13,15,20,29,34], including victim drag/rescue [13,15,29], climbing rope [34], and others [18,20].

3.3. Physical Training Programs

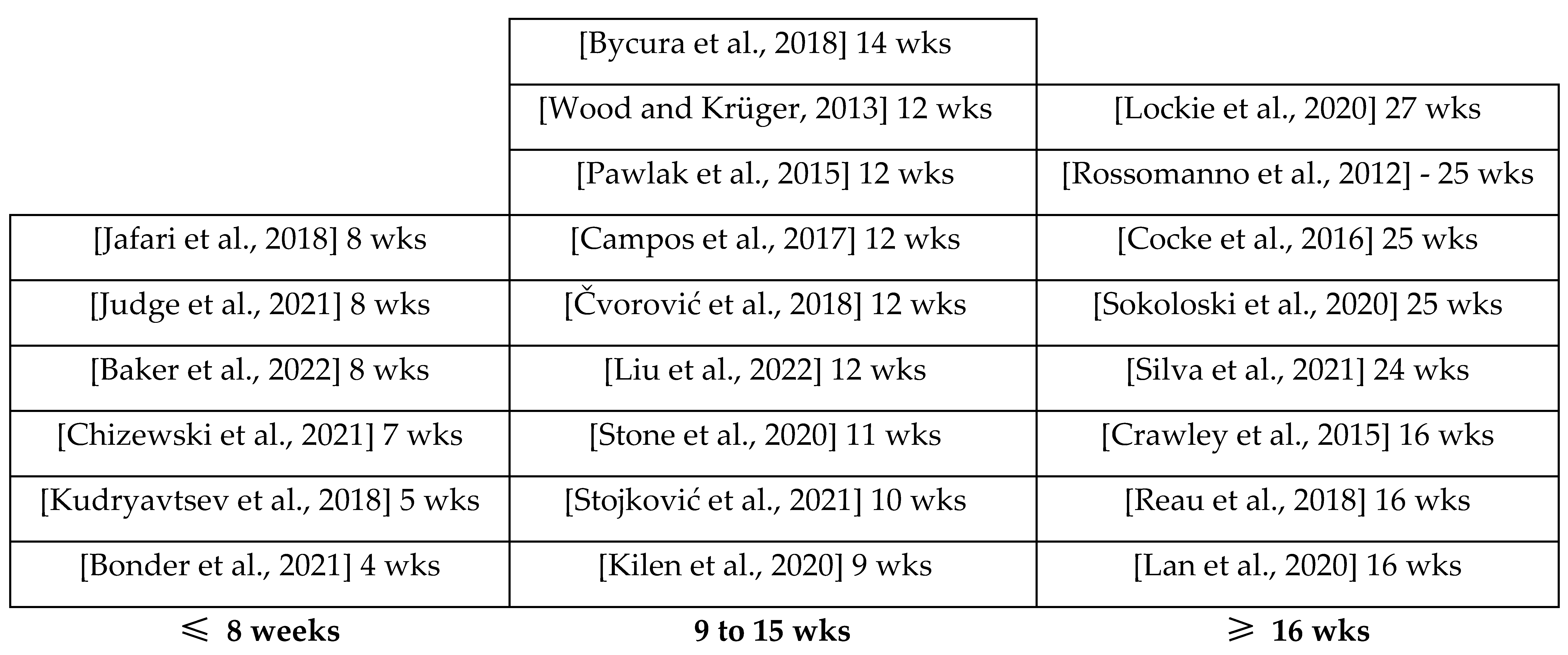

The physical training programs applied in the studies ranged from four [28] to twenty-seven [25] weeks. Of the studies, three had a 25-week duration [13,16,26], five had a 12-week duration [14,15,17,19,34], three had 16-week [3,22,24] and 8-week [20,30,33] durations, and others had one article with five [21], seven [29], nine [23], ten [32], eleven [27], fourteen [18], and twenty-four [31] weeks duration. Figure 2 schematizes the time of the physical training programs. Additionally, as we can understand, most studies use physical training programs for 12- and 25-week durations.

Figure 2.

Physical training programs duration (in weeks; wks) [3,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,34].

The most-used PF programs were cardio training [3,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,31,32,33], weight training [3,14,15,16,17,19,20,21,22,24,27,30,31,32,34], calisthenics training (involving bodyweight exercises such as push-ups, pull-ups, and others) [3,13,15,16,19,23,24,25,26,29,30,32,33,34], and circuit training [3,13,15,17,19,22,23,25,26,29,30,31,32,33]. Three other studies were high-intensity functional training [16,29,33], and one applied the test repeatedly (20-m run and hex-bar deadlift) [28] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Physical training programs distributions.

The results of this study have important implications for selecting the most-used physical training plans to improve exercise regimens for TP. We found that for the muscle endurance tests, such as the 60-s sit-ups and push-ups, training programs between 7 and 25 weeks showed large effect sizes (Cohen’s d between 0.99 and 5.65) [14,16,17,19,26,29,30,32], while the other tests showed small effects (Cohen’s d between 0.24 and 0.45) [3,23,28,29]. All abdominal muscle tests showed medium and small effects (Cohen’s d between 0.40 and 0.61) after 9 weeks of training [23], back extension showed medium and large effects (Cohen’s d between 0.77 and 1.03) after 9 weeks of exercise [23], while lunges test also showed small-to-medium effects (Cohen’s d between 0.45 and 0.78) after 9 weeks of training [23]. Regarding muscular strength, the 1 RM bench press test showed large effects at the 12 week intervention point (Cohen’s d ranging from 0.97 to 1.96) [34] and medium effects at the 25 week intervention point (Cohen’s d of 0.56) [16]. There were small effects at the 7 week intervention point (Cohen’s d ranging from 0.38 to 0.45) [34]; the 1 RM back squat, on the other hand, showed large effects (Cohen’s d between 0.82 and 1.25) at the 12 week intervention point [34]. Muscular power, countermovement jump with arm swing, and seated medicine ball throw showed large effects at the 12 week intervention point (Cohen’s d between 1.03 and 2.17) [34]; the vertical jump showed a medium effect at the 25 week intervention point in the RT group (Cohen’s d, 0.76) [16]; all other tests showed small and trivial effect values (Cohen’s d between 0.03 and 0.47) [16,29,34]. Flexibility at the 7 week intervention point showed a small effect (Cohen’s d, 0.31) [29] and a large effect at the 25 week intervention point (Cohen’s d, 0.93) [26]. Agility also showed small effects at the shorter intervention point of 10 weeks (Cohen’s d, 0.42) [3] and large effects at the intervention point of 16 weeks (Cohen’s d, 1.41) [32]. When we analyzed aerobic capacity variables, we found large and medium effects for most interventions between 7 and 25 weeks (Cohen’s d between 0.54 and 65.76) [16,19,23,29,32]. The anaerobic tests showed results with trivial effects in the sprint test at the 4 week intervention point (Cohen’s d, 0.18) [28], medium effects at the intervention point of 16 weeks (Cohen’s d, 0.51) [3], and small effects in the Wingate test (Cohen’s d, 0.42) [3]. Table 5 shows all results.

Table 5.

Effect size (Cohen’s d) and effect size correlation (r) of physical training programs on fitness measures.

4. Discussion

The aims of this review were (i) to identify and analyze the most-used PF programs for TP and (ii) to understand their impact on the development of physical abilities associated with the performance of the function.

All studies showed acceptable methodological quality in assessing PF and the physical training program.

The tests assessing motor skills that greatly impacted task performance in the studies analyzed in this review varied widely. Of note were the tests assessing strength, which were present in 17 of the 23 studies analyzed [3,14,15,16,17,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,32,34], and aerobic capacity, which was present in 10 of 23 studies [14,16,19,22,23,24,25,27,29,32]. This was followed by the assessment of flexibility [3,15,26,29,30], speed [3,16,28,34], and agility [3,32]. The most applied assessments were: (i) handgrip test [3,15,21,25,27,30] and bench press [3,16,29,33,34] for muscle strength; (ii) push-ups [3,14,16,17,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,32] and sit-ups [3,14,16,17,19,23,25,26,29,30,32] for muscular endurance; (iii) vertical jump [3,16,25,27,29,34] for muscle power; (iv) 2.4-km run (1.5-mile run) [14,16,19,22,24,29,32] and 20-m shuttle run [23,25,27,34] for aerobic capacity; and (v) sit-and-reach [3,15,26,29,30] for flexibility.

Male TP performed significantly better than females on all measures [3,13,16,23,25,26], except for flexibility [3], measured through the sit-and-reach test.

The training plans applied in the different studies were diverse. The studies included in this review showed that a physical training program positively influences TP. The most-used PF programs were calisthenics/bodyweight training [13,15,16,17,20,24,25,26,27,30,31,33,34,35], cardio training [3,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,31,32,33], circuit training [3,13,15,17,22,23,25,26,29,30,31,32,33], and weight training [3,14,15,16,17,19,20,21,22,24,27,30,31,32,34]. Some other studies were high-intensity functional training [29], and one applied the test repeatedly (20-m shuttle run and hex-bar deadlift) [28].

In almost all programs, we observe a combination of various types of exercises, with body weight or using external loads (weights) combined with cardiovascular training.

Overall, the studies included in this review have shown that a physical training program could significantly improve tactical populations’ PF.

In the studies reviewed, statistically, significant improvements were seen in almost all [3,13,15,16,19,23,24,26,29,30,32,34], except for one [28], perhaps because the program was too short (4 weeks).

Despite the diversity and different options of the physical training programs, all of them proved fruitful since, in all the studies, improvements were observed in the motor skills evaluated and the health measures themselves.

In the study by Bonder et al. [28], they did not observe significant improvements in the sprint, perhaps because too short a training program (only four weeks) was applied, which could indicate that training programs in these areas need to be longer in duration or performed more times per week to provoke improvements, as noted by Lahti et al. [35], in a study they conducted with soccer players on speed. These authors suggest that training of at least eight weeks, 1 to 2× per week, should be applied to observe improvements. This is consistent with our findings, where most studies with more minor interventions had smaller effect sizes on PF performance tests.

We could conclude from this review that studies with less than eight weeks may not be sufficient to show significant differences [28]. Still, studies with more than 16 weeks are extensive and show little changes compared to TP between 9 and 15 weeks [15,19,23,32,34]. Thus, we can conclude that TP adjusted between 9 and 15 weeks show significant differences in PF [3,13,16,24,25,26].

In strength work, whether through a weight or bodyweight training program, we can see that improvements have been observed in short periods. Even in the study by Chizewski et al. [29], improvements were observed in only seven weeks. These results are like those obtained by Munn et al. [36], who also eyed improvements in strength capacity in only six weeks.

In the study by Cocke et al. [16], the randomized training group significantly improved all parameters. In contrast, the periodized group observed significant improvements in only three outcome measures (push-ups, sit-ups, and 300-m sprint). Periodized training does not provide additional improvements. Nevertheless, this information needs to be carefully analyzed as it contrasts with the study by Knapik et al. [37] that observed improvements in both periodized and randomized training groups.

Rossomanno et al. [13] and Lan et al. [24], who observed in their study several improvements in the training program applied after the end of the training program, when they reapplied the battery of tests sometime later, observed regression in the results obtained, both in the trials and in terms of health measures. In this sense, to ensure that police officers are prepared to perform their duties on the job, it is recommended that police departments provide a regular, supervised, job-based exercise program throughout the year [13].

Physical activity must be part of the daily routine for TP so that they improve or at least maintain high levels of PF that are essential for mission performance. The program must be supported throughout their lives because more is needed for TP to have physical activity during the course and not any physical activity at work.

However, a limitation of this review was the small number of studies analyzed. Initially, the idea was to critically review studies in which the sample consisted of police officers. However, after determining that there were very few studies of this type, it was decided to include studies in which the sample included so-called TP (i.e., tactical athletes). In addition to police officers, studies involving firefighters and military personnel were included, and studies involving cadets/recruits and cadets who are not yet TP were also included. Another limitation of these studies was the different methodological characteristics of each study (other test batteries), the different duration and frequency of use of the training, and the studies with different sexes when the results are presented in standard averages; therefore, the results here are weakened. This promotes considerable variability in the results with the small number of studies.

The content of this review is essential because it informs those responsible for developing training programs for tactical populations, which tests are most applied, and which training programs show the best results.

We consider it essential to develop a study like those analyzed [application of a training program to tactical populations] in Portugal to understand if the applications are transversal or if adaptations are necessary for the Portuguese context.

5. Conclusions

All studies included in this critical review have been evaluated as fair-to-sound quality, proving that training programs of varied frequency and exercise type can help improve required fitness testing results and optimize job performance.

To be effective, physical training programs should last at least eight weeks and have a weekly frequency of at least three times. Programs that combined strength training with cardiovascular training were shown to be more effective in creating positive changes in outcome measures and included exercises such as push-ups, running, bench press, front and back squats, burpees, lunges, sprints, and work-specific simulations (e.g., loaded run and dummy drag).

Because of their physically demanding work, TP needs specific training programs for their activity, which must remain throughout their career.

After a survey of studies conducted in this scope, only one investigation was observed in Portugal with a training program applied to TP. Therefore, conducting more studies to provide TP with adequate exercise for their functions is necessary. It is also essential to conduct a study with the long-term fitness and health outcomes of a randomized vs. periodized approach to clarify if traditional programs provide (or not) additional benefits over periodized exercise programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and resources, L.M.M. (PI); methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and writing (original draft preparation, review, and editing), A.R., V.S. and L.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. This article is based on the master’s thesis in Internal Security of A.R,. conducted under the supervision of L.M.M. at the Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security (ISCPSI, Lisbon, Portugal).

Funding

This research was funded by the Portuguese National Funding Agency for Science, Research and Technology—FCT, grant number UIDP/04915/2020 and UIDB/04915/2020 (ICPOL Research Center —Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security (ISCPSI)—R&D Unit).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lyons, K.; Radburn, C.; Orr, R.; Pope, R. A Profile of Injuries Sustained by Law Enforcement Officers: A Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.Q.; Clasey, J.L.; Yates, J.W.; Koebke, N.C.; Palmer, T.G.; Abel, M.G. Relationship of Physical Fitness Measures vs. Occupational Physical Ability in Campus Law Enforcement Officers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2340–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawley, A.A.; Sherman, R.A.; Crawley, W.R.; Cosio-Lima, L.M. Physical Fitness of Police Academy Cadets: Baseline Characteristics and Changes During a 16-Week Academy. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marins, E.; Silva, P.; Rombaldi, A.; Vecchio, F. Occupational physical fitness tests for police officers—A narrative review. TSAC Rep. 2019, 50, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Marins, E.; David, G.; Vecchio, F. Characterization of the Physical Fitness of Police Officers: A Systematic Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2860–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marins, E.F.; Del Vecchio, F.B. Health Patrol Program: Health Indicators in Federal Highway Patrol. Sci. Med. 2017, 27, 25855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, J.; Andrade, M.L.; Gealh, L.; Andreato, L.V.; de Moraes, S.F. Description of the physical condition and cardiovascular risk factors of police officers military vehicles. Rev. Andal. Med. Deporte. 2014, 7, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, L.; Randall, J.R.; Guptill, C.A.; Gross, D.P.; Senthilselvan, A.; Voaklander, D. The Association Between Fitness Test Scores and Musculoskeletal Injury in Police Officers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, D.M.; Schlosser, M.D.; Papazoglou, K.; Creighton, S.; Kaye, C.C. New Directions in Police Academy Training: A Call to Action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massuça, L.M.; Santos, V.; Monteiro, L.F. Identifying the Physical Fitness and Health Evaluations for Police Officers: Brief Systematic Review with an Emphasis on the Portuguese Research. Biology 2022, 11, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyröläinen, H.; Häkkinen, K.; Kautiainen, H.; Santtila, M.; Pihlainen, K.; Häkkinen, A. Physical fitness, BMI and sickness absence in male military personnel. Occup. Med. 2008, 58, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossomanno, C.I.; Herrick, J.E.; Kirk, S.M.; Kirk, E.P. A 6-month supervised employer-based minimal exercise program for police officers improves fitness. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 2338–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, P.; Krüger, P. Comparison of physical fitness outcomes of young south african military recruits following different physical training programs during basic military training. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2013, 35, 203–217, ISBN 0379-9069. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, R.; Clasey, J.L.; Palmer, T.; Symons, T.B.; Abel, M.G. The effect of a novel tactical training program on physical fitness and occupational performance in firefighters. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocke, C.; Dawes, J.; Orr, R.M. The Use of 2 Conditioning Programs and the Fitness Characteristics of Police Academy Cadets. J. Athl. Train. 2016, 51, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.; Campos, F.; Bezerra, T.; Pellegrinotti, Í. Effects of 12 Weeks of Physical Training on Body Composition and Physical Fitness in Military Recruits. J. Exerc. Sci. 2017, 10, 560–567. [Google Scholar]

- Bycura, D.; Dmitrieva, N.; Santos, A.; Waugh, K.; Ritchey, K. Efficacy of a goal setting and implementation planning intervention on firefighters’ cardiorespiratory fitness. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 33, 3151–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čvorović, A.; Kukić, F.; Orr, R.M.; Dawes, J.J.; Jeknić, V.; Stojković, M. Impact of a 12-Week Postgraduate Training Course on the Body Composition and Physical Abilities of Police Trainees. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Zolaktaf, V.; Ghasemi, G. Functional Movement Screen Composite Scores in Firefighters: Effects of Corrective Exercise Training. J. Sport Rehabil. 2020, 29, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtsev, M.; Osivop, A.; Kokova, E.; Kopylov, Y.; Iermakov, S.; Zhavner, T.; Vapaeva, A.; Alexandrov, Y.; Konoshenko, L.; Görner, K. The possibility of increasing cadets’ physical fitness level of the educational organizations of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia with the help of optimal training effects via crossfit. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2022, 18, 2022–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reau, A.; Urso, M.; Long, B. Specified Training to Improve Functional Fitness and Reduce Injury and Lost Workdays in Active Duty Firefighters. J. Exerc. Physiol. Online 2018, 21, 49–57, ISSN 1097-9751. [Google Scholar]

- Kilen, A.; Bay, J.; Bejder, J.; Breenfeldt Andersen, A.; Bonne, T.; Larsen, P.; Carlsen, A.; Egelund, J.; Nybo, L.; Vidiendal Olsen, N.; et al. Distribution of concurrent training sessions does not impact endurance adaptation. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2021, 24, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, F.Y.; Yiannakou, I.; Scheibler, C.; Hershey, M.S.; Cabrera, J.; Gaviola, G.C.; Fernandez-Montero, A.; Christophi, C.A.; Christiani, D.C.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; et al. The Effects of Fire Academy Training and Probationary Firefighter Status on Select Basic Health and Fitness Measurements. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockie, R.G.; Dawes, J.J.; Maclean, N.D.; Pope, R.P.; Holmes, R.J.; Kornhauser, C.L.; Orr, R.M. The Impact of Formal Strength and Conditioning on the Fitness of Law Enforcement Recruits: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2020, 13, 1615–1629. [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloski, M.L.; Rigby, B.R.; Bachik, C.R.; Gordon, R.A.; Rowland, I.F.; Zumbro, E.L.; Duplanty, A.A. Changes in Health and Physical Fitness Parameters After Six Months of Group Exercise Training in Firefighters. Sports 2020, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, B.; Alvar, B.; Orr, R.; Lockie, R.; Johnson, Q.; Goatcher, J.; Dawes, J. Impact of an 11-Week Strength and Conditioning Program on Firefighter Trainee Fitness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonder, I.; Shim, A.; Lockie, R.G.; Ruppert, T. A Preliminary Investigation: Evaluating the Effectiveness of an Occupational Specific Training Program to Improve Lower Body Strength and Speed for Law Enforcement Officers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizewski, A.; Box, A.; Kesler, R.; Petruzzello, S.J. Fitness Fights Fires: Exploring the Relationship between Physical Fitness and Firefighter Ability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, L.W.; Skalon, T.; Schoeff, M.A.; Powers, S.; Johnson, J.E.; Henry, B.; Burns, A.; Bellar, D. College Students Training Law Enforcement Officers: The Officer Charlie Get Fit Project. Phys. Educ. 2021, 78, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.; Bezerra, P.; Silva, B.; Carral, J. Firefighters cardiorespiratory fitness parameters after 24 weeks of functional training with and without personal protective equipment. Sport Tour. 2021, 28, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojkovic, M.; Kukic, F.; Nedeljkovic, A.; Orr, R.; Dawes, J.; Cvorovic, A.; Jeknic, V. Effects of a physical training programme on anthropometric and fitness measures in obese and overweight police trainees and officers. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2021, 43, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S.B.; Buchanan, S.R.; Black, C.D.; Bemben, M.G.; Bemben, D.A. Bone, Biomarker, Body Composition, and Performance Responses to 8 Weeks of Reserve Officers’ Training Corps Training. J. Athl. Train. 2022, 57, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zhou, K.; Li, B.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Y.; Miao, G.; Zhou, L.; Liu, H.; Bao, D.; Zhou, J. Effect of 12 weeks of complex training on occupational activities, strength, and power in professional firefighters. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 962546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahti, J.; Huuhka, T.; Romero, V.; Bezodis, I.; Morin, J.; Häkkinen, K. Changes in sprint performance and sagittal plane kinematics after heavy resisted sprint training in professional soccer players. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, J.; Herbert, R.D.; Hancock, M.J.; Gandevia, S.C. Resistance training for strength: Effect of number of sets and contraction speed. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 1622–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapik, J.; Darakjy, S.; Scott, S.J.; Hauret, K.G.; Canada, S.; Marin, R.; Rieger, W.; Jones, B.H. Evaluation of a standardized physical training program for basic combat training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).