Abstract

Background/Objectives: Clinical incidents can be valuable learning tools to improve patient safety. However, failure to report or underreporting of clinical incidents is a global phenomenon. Understanding nurses’ experiences is essential to identifying challenges and developing strategies to enhance incident reporting behaviours. This review aimed to explore the experiences and perceptions of acute care bedside nurses regarding incident reporting. Methods: This review used scoping review methods. A search of the MEDLINE and CINAHL databases returned 16 papers that were included in the review. Results: Five main themes were identified—Fear of Reporting, Levels of Reporting, Lack of Knowledge, Education and Training on Reporting, Benefits of Reporting, and Changing the Culture. Conclusions: Nurses experience fear of incident reporting stemming from negative repercussions and the organisational blame culture. Lack of knowledge and training about errors and incident reporting processes limits incident reporting behaviours. To enhance reporting behaviours, promoting a just culture that includes the support of managers, open communication, and feedback on incidents is important. Education and training can also enhance nurses’ awareness and capability of incident reporting.

1. Background

Unsafe care is estimated to cause over three million deaths every year worldwide [1]. A clinical incident is any unintended event or unsafe condition resulting from the care process, with patient outcomes ranging from near-misses to incidents resulting in severe harm or death [2]. An estimated 42.7 million patients worldwide experience adverse events when in hospital [3]. Clinical incidents and adverse events can significantly impact patients, healthcare organisations, and healthcare workers [4]. However, a significant gap remains in understanding the precise series of events and the system weaknesses that lead to safety incidents [3].

Despite the potential for damaging consequences of patient harm, clinical incidents can be helpful learning tools to improve patient safety if they are reported [5]. Incident reporting is designed to identify system failures with the information used to implement measures to improve patient safety [6]. Clinicians have an ethical and moral responsibility to provide safe care, act in the patient’s best interest, be open and honest about errors or near-misses, and commit to learning from mistakes [7]. While incident reporting is considered an effective method for improving healthcare safety, healthcare organisations and clinicians often overlook the actual reporting of incidents [8].

Failure to report or underreporting of incidents is a global phenomenon and a significant hurdle in patient safety [9]. Yung et al. [10] indicate that the rate of error reporting in the United Kingdom is 22–39%, in Taiwan it is 30–48%, and in the United States of America it is 40–50%. Some studies have estimated that clinicians report clinical incidents with a frequency between 1% and 3% of total cases [11,12,13]. Research has been conducted to explore the barriers to incident reporting, with findings suggesting inadequate incident reporting systems, poor managerial conduct, lack of multidisciplinary collaboration, and limited training as core elements [14]. Inadequate incident reporting systems are the absence of organisational support required to foster incident reporting behaviours in nurses, such as policies and effective interventions to promote reporting [14]. One such organisational intervention in promoting incident reporting is the establishment of a “just culture”, which has been shown to increase the number of reported patient safety incidents, help staff learn from incidents, and reduce the risk of further patient safety incidents [15]. A just culture encourages healthcare workers to speak up about patient safety, does not apply blame but rewards staff for doing so, and ultimately increases trust among healthcare staff [15].

Bedside nurses are direct providers of care and, therefore, have an essential role in keeping patients safe [16]. Additionally, the high-stress, fast-paced nature of acute care nursing exacerbates the risk of errors, making nurses particularly vulnerable to mistakes and near-misses [17]. The evidence outlined above indicates that there are barriers that contribute to failure to report and significant underreporting. However, it is also important to understand the perspectives of nurses in incident reporting, as bedside nurses often act as the first line of defence to prevent errors for hospitalised patients [17]. Understanding bedside nurses’ perspectives and experiences with incident reporting is essential to identifying their challenges and developing suitable strategies to assist in improving nurses’ reporting practices and patient safety.

2. Aim

This scoping review aimed to answer the following research question: What are the experiences and perceptions of acute care bedside nurses regarding incident reporting?

3. Methods

A scoping review was deemed suitable as the review aims to map the evidence regarding bedside nurses’ experiences and perceptions of completing incident reports in acute care settings. The findings from the review will assist in identifying the gaps in knowledge and inform future research. This scoping review is conducted in adherence to the Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews [18], guided by a protocol and reported using the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-Scr) [19]. We did not register a protocol for this review as this is not mandatory for a scoping review. However, a protocol was developed to guide the review, detailing the scope, search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data extraction approach. The research question was formulated using the population, phenomenon of interest, and context structure (PPIC). Following this, the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis guided the scoping review [20].

3.1. Search Strategy

Articles from January 2019 to December 2024 were identified by searching MEDLINE in the EBSCOhost database. The subject headings “nursing staff, hospital”, “incident reports”, and “hospitals+” were used in the search. The following search terms were searched for in the title and abstracts of articles: “nurs*”, “experience*”, “perception*”, “attitude*”, “view*”, “feeling*”, “perspective*”, “hospital*”, or “acute care”. The following terms were searched in the titles and abstracts of articles using proximity searching with the term “report*”: “Incident*” or “error*” or “near-miss*” or “adverse event*”. Search results were limited to English language results. A search using the same keywords and Boolean operators was constructed in CINAHL. Table 1 depicts the search strings used in each database for this scoping review. Initially, 254 articles were returned from MEDLINE, and 197 articles were returned from CINAHL before data reduction commenced.

Table 1.

Search strings.

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

Eligible for inclusion were articles reporting (i) empirical studies that (ii) described the experiences and perceptions, (iii) of participants who were nurses employed in acute care hospitals and provided direct patient care, (iv) that documented the reporting of clinical incidents, near-misses, or adverse events, and (vi) were written in English. Only the data relevant to nurses was included in this scoping review. Articles that included other health professionals, such as medical doctors and allied health staff, in their studies alongside nurses were included in the literature review, where the data regarding the nurses were reported separately and could be extracted for analysis.

3.3. Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they focused exclusively on the experiences of nurse managers or clinical leaders, as the focus was on bedside nurses’ reporting. Articles were excluded if they focused on the reporting of incidents of colleagues. Articles that aimed to develop theories or models to predict nurses’ intent to report clinical incidents were excluded, and articles where the data regarding nurses’ experiences and perceptions could not be separated from other health professionals were also omitted. All types of reviews and meta-analyses were excluded to avoid duplication of results.

3.4. Data Selection

Titles and abstracts of retrieved papers from each database were screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Duplicates were screened through EndNote before full-text screening commenced. Two researchers undertook full-text screening, with any conflicts resolved through consensus.

3.5. Data Extraction

Relevant study data were extracted and tabulated using the column headings author/publication year, study design, research aim/question, location/setting, participants, and findings. The data extraction table was piloted with the data extracted from Abdelmaksoud et al. [21], the first paper included in the study. Following the pilot, the headings for the overall findings category were updated to include the column headings of Experiences and perceptions of reporting, Incident reporting practices, Barriers and Enablers to reporting, and Recommendations to reflect the work of Abdelmaksoud et al. [21]. Two researchers undertook data extraction of included papers, with any conflicts resolved through discussion and consensus. See Table 2 for characteristics and findings of included studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

3.6. Data Analysis

Microsoft Excel was used to tabulate the data and to support data analysis and organisation. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the extracted data to find common themes in the findings. The researchers read and reread the extracted data to familiarise themselves with it. Patterns and similarities in the data were noted and assigned codes. Codes that were similar were grouped into themes. Data were reviewed in each theme for consistency, coherence, and fit. Themes were named and defined and are reported below.

3.7. Quality Appraisal

While quality appraisal is optional in a scoping review, it was conducted in this review to explore the quality of the research being conducted on the topic. No study was excluded based on the quality appraisal score. The quality of evidence was assessed using the JBI critical appraisal tools. A total score for each tool was calculated by identifying elements of the checklist reported in the paper, compared with those absent, and calculated as a percentage of the total number of elements. Each quality appraisal tool used was selected to align with the study design of each included article. The quantitative studies were assessed using the JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies [24]. The qualitative studies were assessed using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research [22]. Evidence was appraised for its relevance, reliability, validity, and credibility.

4. Results

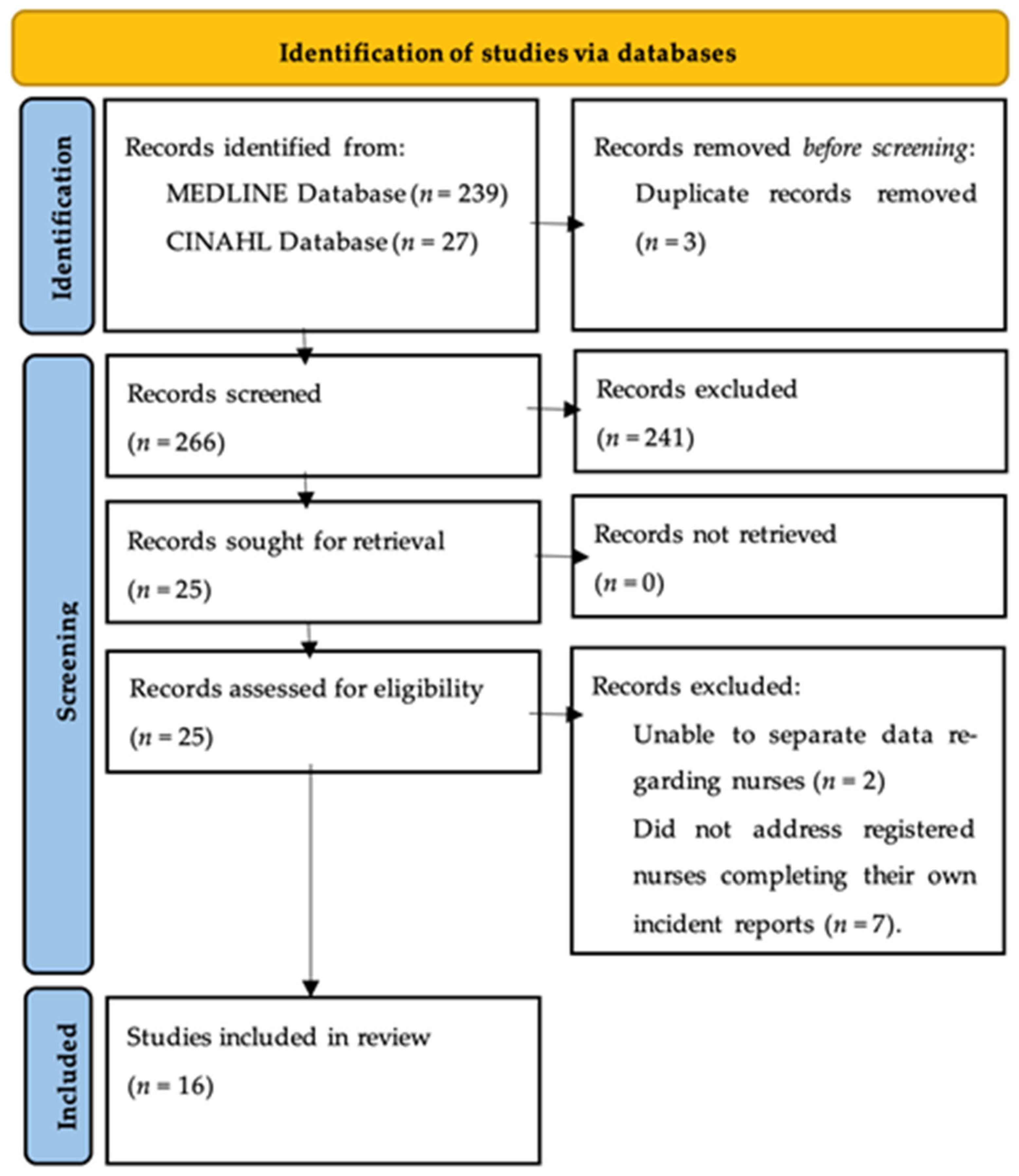

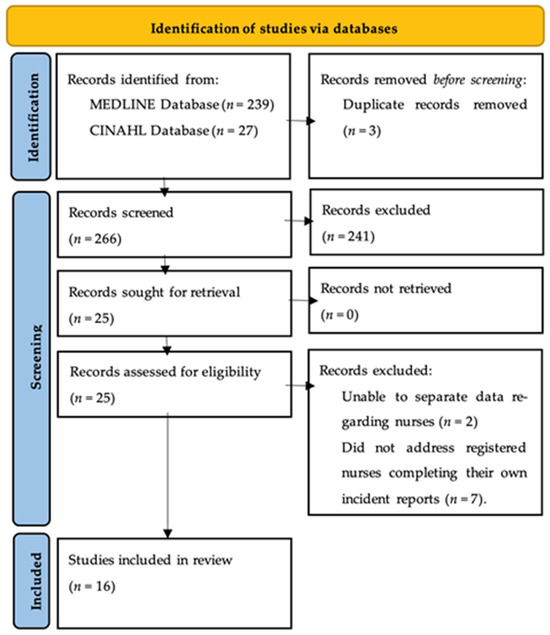

The MEDLINE database search retrieved 239 records, and the CINAHL database returned 27 records. Three duplicates were removed using EndNote. Following a title and abstract review, 25 records were deemed suitable to progress to full-text review. After full-text review, 16 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final scoping review. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA-Scr flowchart [34].

Figure 1.

PRISMA_ScR flow chart.

4.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Studies originated from Iran (n = 4), Jordan (n = 2), and Saudi Arabia (n = 2), with one paper reported each from Australia, Ethiopia, India, Italy, Taiwan, Malta, Palestine, and South Korea (n = 1) (Table 2). Thirteen studies used a quantitative research methodology, with 12 authors implementing a cross-sectional research design [2,3,4,7,23,25,26,27,29,31,32,33] and one using an exploratory survey [8]. Three studies used a qualitative methodology, with two authors reporting individual interviews [21,30] and the other using a combination of individual interviews and focus groups [28]. The sample size reported in the papers included in the review totaled 3,782 nurses. In one study, the sample size of nurses compared to other participants could not be determined [7].

4.2. Quality of Evidence

All quantitative studies scored 83% on The JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies (Table 2) [24]. Most studies employed validated surveys and questionnaires, and applied appropriate statistical analysis. The quantitative studies were vulnerable to social desirability response bias, as studies relied on surveys completed by clinicians, which may have led to an overestimation of positive attitudes and desired behaviours [33].

The qualitative studies scored 75–90% on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research (Table 2) [22]. All the qualitative studies shared a congruent research methodology, research objectives, and the methods used to collect data [22]. As these studies were interested in nurses’ experiences with incident reporting, interviews were the most common way to collect this data. Most qualitative studies presented illustrations from the data to show the basis of the results and ensure that participants are represented [22]. However, it is worth noting that most qualitative articles did not locate the researcher culturally or theoretically and did not address the researcher’s influence on the research [22]. Knowing the researcher’s cultural or theoretical orientation in qualitative studies is important for appraising the evidence because of the researcher’s significant role in the qualitative research process [22]. A statement on the researchers’ reflexivity process and how their assumptions, beliefs, or biases could have influenced the data would have further strengthened the quality of the evidence in these qualitative reviews.

4.3. Thematic Results

Five main themes were identified: Fear of Reporting, Levels of Reporting, Lack of Knowledge, Education and Training on Reporting, Benefits of Reporting, and Changing the Culture.

4.4. Fear of Reporting

The theme “Fear of Reporting” describes the participants’ overriding feelings toward completing incident reports. Nurses report fearing the consequences of making a report, the fear of being blamed by coworkers, and the fear of the blame culture that pervades clinical practice.

Many nurses feared completing an incident report [8,21,28,31,33]. Fear stemmed from the fear of repercussions [21], including disciplinary action [23,26] and being reprimanded [31]. Nurses reported a fear of demotion and financial penalties [4] and a concern that they are risking their job security [8,28,31,33]. Fear of legal action was another factor reported by nurses [29]. This fear is associated with mistrust, resignation, and scepticism [8]. Additionally, respondents in the study conducted by Al-Oweidat et al. [23] felt uneasy about who else could see the information disclosed in reports.

Some nurses reported being blamed by coworkers when an error occurred (53%), with 44% highlighting unsupportive colleagues [26]. In contrast, while 53% of nurses felt that reporting an error can embarrass a coworker, only 22% (n = 31) of nurses indicated that those who made an error were subjected to humiliation or blamed by their colleagues, 25% (n = 34) [26]. Nurses were concerned that reporting an incident would result in a change to their social status [28], that they would lose the respect of their colleagues [33], that people would turn against them [3], or because of the reaction of their coworkers manager and executive [32].

Blame culture prevalent in the studied hospitals was identified by 68% of respondents [33]. Additionally, organisational blame culture was described as a barrier to reporting by Abdelmaksoud et al. [21], Mahdaviazad et al. [31], and Napoli [8]. The blame culture emphasised fear of blame from management, lack of governance [28], and poor communication [30] rather than a focus on patient safety [4]. Incident reporting is often perceived to be about disciplining nurses who make mistakes rather than a tool for learning and preventing future errors [32]. Mansouri et al. [4] reported an absence of support from clinical leaders. Conversely, some nurses in the study by Rashed and Hamdan [33] felt supervisors supported those who reported errors. Ward and Mangion [3] observed that respondents considered that reporting adverse events would not result in system improvements that would protect patient safety.

4.5. Levels of Reporting

The theme “Levels of reporting” describes nurses’ reporting practices, including their intention to report versus their reporting behaviours and responsibilities.

Discrepancies exist between nurses’ intention to report and the reporting of incidents [23]. Rashed and Hamdan [33] indicated a high level of nurses’ awareness in reporting incidents, and Kapil and Anoopit [29] reported that 80% of nurses were positive about reporting. Similarly, another study stated that 68% of nurses agreed to report errors, 65% felt the need to reveal errors, and 84% indicated that they would not hide or deny reporting errors in self-interest [26]. However, in a Taiwan study, 60% of nurses do not have a voluntary attitude when reporting errors, with only 49% committed to voluntary reporting [27]. Moreover, in the study by Mansouri et al. [4], while 49% (n = 123) of the nurses had experienced an adverse event, 71% (n = 89) had not reported it. Likewise, in Italy, 43% (n = 53) of nurses rarely reported an event, while only 14% (n = 17) reported any event witnessed [8]. In Ethiopia, only 37% of nurses reported yes to incident reporting behaviours [2], and some nurses indicated they had a natural inclination to cover up errors [28].

More than half (57%) of nurses in the study by Alsulami et al. [25] agreed that reporting medication errors is their responsibility. However, nurses in other studies were unclear about who was responsible for reporting an incident and to whom the report needed to be made [30]. In the study by Shemsu et al. [2], most nurses, 65%, were uncertain of their obligation to report incidents.

4.6. Lack of Knowledge—What to Report

The theme “Lack of knowledge” illustrates the nurse’s knowledge and understanding of what defines an error to be reported. This includes the severity of the error to determine reporting, the knowledge of reporting procedures, and how near-misses are classified.

Knowledge of reportable error definition among nurses was noted as inconsistent [21]. Similar findings were reported by Mahdaviazad et al. [31], with nurses having varied knowledge about the definition, classification, and identification of errors. This ranged from having no idea to knowing the scientific definition, classification, and identification. In a study conducted in Jordan, 47% of nurses were not confident about what constitutes medication errors, and 49% were not sure when to report medication errors using incident reports [32]. Similarly, Kapil and Anoopit [29] identify that 58% of staff had average knowledge of reporting practices. Moreover, Mrayyan et al. [32] indicate that 53% of nurses were confident about what constitutes an error, and 51% were sure when to report errors. This finding is clarified by Mahdaviazad et al. [31], with only 10% of nurses reporting a good understanding of adverse events. A lack of knowledge meant some nurses did not recognise the seriousness of errors and did not report them [30].

In two studies, the seriousness of the error was considered grounds for reporting. The study by Abdelmaksoud et al. [21] clarified that nurses thought the seriousness of an error was the determining factor for lodging an incident report. Similarly, Mrayyan et al. [32] reported that 52% of nurses considered medication errors must be “serious” to be reported. Conversely, findings from Alsulami et al. [25] indicated that regardless of the seriousness of the incident, nurses favoured reporting.

4.7. Lack of Knowledge—How to Report

There is variation in the understanding of reporting procedures, with many nurses having a basic knowledge of these procedures [21,29]. In Ethiopia, 43% of nurses did not know where to find an incident form or how to lodge it [2]. In Italy, only 40% of nurses in the study were aware of the online reporting system [8]. In contrast, 95% of nurses in a study in Iran were aware of the reporting system, with 60% of participants having used the system [23]. Similarly, 77% of nurses in the study in Malta had completed an incident report, and 72% were aware of where to locate the form [3]. Moreover, senior nurses had a greater understanding of and more experience with reporting incidents [21].

Nurses reported that near-misses were underreported, with some nurses not believing that near-misses are errors [21]. Some nurses were unaware that they made near-miss errors, did not recognise the importance of these errors, did not feel an urgent need to address them, and did not report them [30]. Near-miss errors are seen as routine, a part of the job, and natural mistakes [30]. However, 41% of nurses in a study in Taiwan declared that they voluntarily reported near-misses [27].

4.8. Education and Training on Reporting

The theme “Education and training on reporting” explains the influence of education and training on incident reporting and how a lack of education and training was identified as a barrier to incident reporting.

Mansouri et al. [4] found that a lack of education on the error reporting process led to barriers to reporting. Additionally, Abdelmaksoud et al. [21] reported a lack of understanding and familiarity with the reporting system as a barrier to reporting. Similarly, Majda et al. [7] found that a lack of understanding about the complicated paperwork was a barrier to reporting.

The lack of education and training led to a lack of definition of an error [28] and a poorly defined description of what constitutes an error [4]. This also created a lack of agreement over what errors should be reported [4], with some senior nurses advising that there was no need to report the error [30] or that errors were not deemed severe enough to report [4]. This lack of clarity, with no criteria for error severity, unclear responsibility on who is to report, and unclear to whom nurses need to make the report, can create tensions and barriers to reporting [30]. Mrayyan et al. [32] report that education about errors, focusing on defining and agreeing on what constitutes a medication error and reporting such errors, would support incident reporting.

4.9. Benefits of Reporting

The theme “Benefits of reporting” describes the benefits, as perceived by nurses, of reporting incidents. Nurses describe learning from errors and improvements to patient safety, but are sceptical about the advantages of near-miss reporting.

In the qualitative study by Abdelmaksoud et al. [21], the benefits of incident reporting were reported as staff learning from errors, education and awareness about errors, looking for trends, addressing system weaknesses, and overhauling systems to avoid similar events. Nurses in Poland thought reporting adverse events was essential and valuable [7]. Specifically, over 80% of participants felt that patient safety is improved by reporting adverse events, and 50–60% thought proactive action may result from error reporting [7]. Similarly, in the quantitative study by Napoli [8], 80% of respondents recognised the helpfulness of reporting errors. Participants of Abdelmaksoud et al. [21] had the following to say about the benefits of reporting: “I suppose the reporting and that allows us to identify if there’s a trend, and if there is a trend, you know, do we [do....] education action plans” and “You cannot learn from your mistakes if you do not report”.

Some nurses felt sceptical about how near-miss reporting could circumvent existing errors [30]. They wondered about the effects of near-miss reporting, as no actions like timely feedback occurred, and they felt that such reporting was meaningless [30]. This eventually resulted in nurses having negative perceptions of near-miss reporting, as it seemed like these reports were brushed aside [30].

4.10. Changing the Culture

The theme “Changing culture” explains the strategies to shift from a blame culture to one of enablement. These strategies included patient safety training and open and transparent support from management to change behaviour.

The study by Alsulami et al. [25] illustrated high reporting rates attributed to a pharmacy awareness campaign, patient safety courses, and safety reporting systems campaigns. They found that incident reporting rises after these programs, and reporting continues to increase yearly [25]. Respondents to Abdelmaksoud et al. [21] noted that user-friendly reporting software and ongoing and repeated training and education on the reporting software were enablers of reporting. Similarly, Napoli [8] found that 81% of responding nurses who had participated in a patient safety training course admitted the value of reporting their errors irrespective of patient outcomes. Respondents who received training in the study by Shemsu et al. [2] were almost three times more likely to submit incident reports than those who did not participate in the training.

Perceiving the support of managers had a statistically significant favourable influence on nurses who reported every or most of the adverse events they encountered [8]. Shemsu et al. [2] found that open communication, support from management, and error report feedback were significantly correlated with enhanced error reporting behaviour.

5. Discussions

This review aimed to examine the experiences and perceptions of registered nurses who work in acute care regarding incident reporting. Overwhelmingly, this review identifies that registered nurses are fearful of incident reporting and the potential consequences they may face as a result [4,23,26,28,29,31,33]. The fear of damage to their social standing [28], professional reputation [33], financial security [8,28,31,33], or possible legal action [23,26,29] was a dominant factor in this review. Organisations must work with nurses to support them during errors and near-miss events to enhance incident reporting, overcome this feeling of fear, and foster a just culture.

The blame culture that is present in all levels of leadership structure in clinical practice in healthcare [21,23], where error analysis is used to assign blame to individuals [32,35], presents a significant challenge for nurses and error reporting. This blame culture needs to be replaced with a just and informed culture where all errors are reported, learning occurs, and outcomes are not held against the nurses involved [35]. A just culture where nurses perceive the support of managers will positively influence nurses to report every or most of the adverse events they encounter [8]. This just culture needs to be supported by open communication, support from management, and error report feedback [2]. Organisations must be conscious of their role in promoting incident reporting practices in their health services. It is recommended that hospital administrators foster and role model a just culture that promotes patient safety, open and transparent communication, and continuous learning [23].

This review suggests that nurses perceive the role of education and training in supporting error reporting as significant. Data indicate that education and training focusing on patient safety can increase the incident reporting rate [2,25,32], assisting with future patient safety initiatives. Education and training programs were seen as useful [8] in improving knowledge of what constitutes an error [31], what errors require reporting, and the reporting systems and processes [21]. Additionally, education and training that outline the valuable impact of error reporting on patient safety would enhance voluntary incident reporting [7]. It is promising to note the success stories of changing nurses’ perceptions of incident reporting for the better through education and training. Future research is needed to determine the most effective education and training strategies for improving nurses’ perceptions and submission of incident reports.

A notable aspect of this review is the underreporting of near-miss incidents, which is a persistent issue. Many nurses reported that near-misses were not errors and did not require reporting [21]. Additionally, it was noted that reports of near-miss events did not receive follow-up or feedback from management, so reporting these was perceived as futile [30]. Reporting near-miss events is critical to ensure these events are eliminated before harm occurs. Interventions to improve incident and adverse event reporting, such as creating a just culture and providing education and training, will also increase near-miss reporting [36]. Of note, the ability for healthcare providers to report anonymously has been shown to increase near-miss reporting in the literature [35,36,37,38]. To support reporting of near-miss events, Small et al. [35] report providing indemnity for the report maker along with easy systems and processes with practical and accessible feedback to the reporting discipline. Additionally, management must equate near-miss reporting with incident reporting to allocate a similar status and value so that near-miss reporting is seen as a value add to patient safety.

Patient safety incidents can negatively impact nurses’ emotional well-being, resulting in them becoming the second victim [39]. Nursing administrators and healthcare organisations should consider the adverse psychological effects nurses can experience following these events [39]. Providing emotional support, a non-punitive approach, and a safe, comfortable work environment for nurses can help lessen the secondary harm they experience and promote a positive safety culture [39].

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this scoping review lie in the adherence to systematic processes and reporting guidelines. The comprehensive search strategy conducted by two researchers across two databases adds rigour to the findings. Additionally, the screening conducted independently by two researchers minimised selection bias. The data extraction table was piloted and revised to ensure that the data extracted from the included papers would align with the aim of the scoping review. Supporting the generalizability of findings is that the contexts of all papers included in the review relate to nurses in acute care. However, the diversity of healthcare organisations, the nurses who work in them, and cultural elements may constrain this.

However, this review has limitations. The review was limited to English, which may have excluded relevant papers published in other languages. Despite a thorough search strategy, there is a risk that some studies were missed. The review may be limited due to the geographical regions where studies are published. The diverse international settings of the reviewed studies will have variances in regional trends and local health governance, which can influence reporting behaviours and limit the transferability of the findings. For example, Alabdullah and Karwowski [40] examined patient safety culture across continents and found that Africa showed the lowest average patient safety culture scores, emphasising a demand for targeted interventions. However, a common weakness globally was non-punitive error responses and lower positive views on communication openness reported by nurses [40]. Additionally, as 76% of studies in this literature review were quantitative, using surveys to gather results, not all nurses’ unique experiences with incident reporting may be captured. Moreover, most quantitative study designs used retrospective data collection, relying on respondents’ memories of events prior to the survey, potentially resulting in recall bias. Therefore, it is questionable to what extent appropriate conclusions can be drawn based on this scoping review since the surveys were conducted in different countries and are retrospective in nature. The importance of the topic is not in doubt, but a planned, prospective study follow-up, where the health consequences caused by incidents are also evaluated, would be useful. The publications reviewed do not provide sufficient concrete evidence on the process of concealing malpractice and the chances of its effective prevention. Finally, as bedside nurses were the focus of this scoping review, a better understanding of incident reporting behaviours would be gained if reviews focusing on other staff in the healthcare team were conducted.

6. Conclusions

This literature review examined the experiences of acute care nurses with incident reporting. Overwhelmingly, nurses reported experiencing fear of incident reporting. Organisational blame culture was identified as a significant barrier to reporting. Furthermore, nurses’ lack of knowledge on what and how to report incidents and how reporting can influence patient safety was identified.

To enhance incident reporting, promoting a just culture that supports and guides nurses who experience near-misses and errors is necessary. Perceiving the support of managers, open communication, and receiving feedback on reported errors and near-misses were significantly associated with incident reporting behaviour. Education and training programs that include the importance of near-miss reporting are recommended. Future research is needed on what education and training strategies are most effective in improving nurses’ perceptions of incident reporting. Changing the culture of fear to one of learning is not optional—it is essential to improving patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.S.; methodology, C.S. and M.P.; validation, C.S. and M.P.; investigation, C.S. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.; writing—review and editing, C.S. and M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available online.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Lachman, P.; Runnacles, J.; Jayadev, A.; Brennan, J.; Fitzsimons, J. Oxford Professional Practice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-01-9269-9269-9. [Google Scholar]

- Shemsu, A.; Dechasa, A.; Ayana, M.; Tura, M.R. Patient safety incident reporting behavior and its associated factors among healthcare professionals in Hadiya zone, Ethiopia: A facility based cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2024, 6, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, C.S.; Mangion, D. Nurses’ attitudes and barriers to incident reporting in Malta’s acute general hospital. Br. J. Nurs. 2023, 32, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, S.F.; Mohammadi, T.K.; Adib, M.; Lili, E.K.; Soodmand, M. Barriers to nurses reporting errors and adverse events. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, H. The effect of patient safety culture on nurses’ near-miss reporting intention: The moderating role of perceived severity of near misses. J. Res. Nurs. 2021, 26, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System; Kohn, L.T., Corrigan, J.M., Donaldson, M.S., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-03-0951-5634. [Google Scholar]

- Majda, A.; Majkut, M.; Wróbel, A.; Kurowska, A.; Wojcieszek, A.; Kołodziej, K.; Bodys-Cupak, I.; Rudek, J.; Barzykowski, K. Perceptions of clinical adverse event reporting by nurses and midwives. Healthcare 2024, 12, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, G. Perceptions and knowledge of nurses on incident reporting systems: Exploratory study in three Northeastern Italian departments. J. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2022, 42, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbnjak, D.; Denieffe, S.; O’Gorman, C.; Pajnkihar, M. Barriers to reporting medication errors and near misses among nurses: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 63, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, H.P.; Yu, S.; Chu, C.; Hou, I.C.; Tang, F.I. Nurses’ attitudes and perceived barriers to the reporting of medication administration errors. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, C.L. A review of the Office of Inspector General’s reports on adverse event identification and reporting. J. Am. Soc. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2011, 30, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varallo, F.R.; Passos, A.C.; Nadai, T.R.; Mastroianni, P.C. Incidents reporting: Barriers and strategies to promote safety culture. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2018, 52, e03346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, V.; Thériault-Dubé, I.; Touzin, J.; Delisle, J.F.; Lebel, D.; Bussières, J.F.; Bailey, B.; Collin, J. Risk perception and reasons for noncompliance in pharmacovigilance: A qualitative study conducted in Canada. Drug Saf. 2009, 32, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, M.M.M.; Konstantinidis, S. Barriers to incident reporting among nurses: A qualitative systematic review. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 44, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, N.; Jeong, S.J.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, H.S. Impacts of just culture on perioperative nurses’ attitudes and behaviors with regard to patient safety incident reporting: Cross-sectional nationwide survey. Asian Nurs. Res. 2024, 18, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Tella, S.A.; Logan, P.; Khakurel, J.; Vizcaya-Moreno, F. Nurses’ adherence to patient safety principles: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Muharraq, E.H.; Abdali, F.; Alfozan, A.; Alallah, S.; Sayed, B.; Makakam, A. Exploring the perception of safety culture among nurses in Saudi Arabia. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood., C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2024; ISBN 978-0-6488488-0-6. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmaksoud, S.; Salahudeen, M.S.; Curtain, C.M. Medication error reporting attitudes and practices in a regional Australian hospital: A qualitative study. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2024, 54, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Munn, Z. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Oweidat, I.A.; Saleh, A.; Khalifeh, A.H.; Tabar, N.A.; Al Said, M.R.; Khalil, M.M.; Khrais, H. Nurses’ perceptions of the influence of leadership behaviours and organisational culture on patient safety incident reporting practices. Nurs. Manag. 2023, 30, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2020; pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-6488488-0-6. [Google Scholar]

- Alsulami, S.L.; Sardidi, H.O.; Almuzaini, R.S.; Alsaif, M.A.; Almuzaini, H.S.; Moukaddem, A.K.; Kharal, M.S. Knowledge, attitude and practice on medication error reporting among health practitioners in a tertiary care setting in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2019, 40, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bany Hamdan, A.; Javison, S.; Alharbi, M. Healthcare professionals’ culture toward reporting errors in the oncology setting. Cureus 2023, 15, e38279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, H.Y.; Lee, H.F.; Lin, S.Y.; Ma, S.C. Factors contributing to voluntariness of incident reporting among hospital nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghobadian, S.; Zahiri, M.; Dindamal, B.; Dargahi, H.; Faraji-Khiavi, F. Barriers to reporting clinical errors in operating theatres and intensive care units of a university hospital: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapil, S.; Anoopjit, K. A study to assess the knowledge, attitude and perceived barriers on incident reporting among staff nurses working in a tertiary care hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 12, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Understanding nurses’ experiences with near-miss error reporting omissions in large hospitals. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2696–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdaviazad, H.; Askarian, M.; Kardeh, B. Medical error reporting: Status quo and perceived barriers in an orthopedic center in Iran. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrayyan, M.T.; Al-Rawashdeh, S.; Al-Atiyyat, N.; Sawalha, M.; Awwad, M. Comparing rates and causes of, and views on reporting of medication errors among nurses working in different-sized hospitals. Nurs. Forum 2021, 56, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A.; Hamdan, M. Physicians’ and nurses’ perceptions of and attitudes toward incident reporting in Palestinian hospitals. J. Patient Saf. 2019, 15, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, D.; Small, R.M.; Green, A. Improving safety by developing trust with a just culture. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 29, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Zhang, X.; Tan, L.; Liu, D.; Dai, L.; Liu, H. Near miss research in the healthcare system A scoping review. J. Nurs. Adm. 2022, 52, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.C.; Larsen, G.Y. Effect of an anonymous reporting system on near-miss and harmful medical error reporting in a pediatric intensive care unit. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2007, 22, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guffey, P.; Szolnoki, J.; Caldwell, J.; Polaner, D. Design and implementation of a near-miss reporting system at a large, academic pediatric anesthesia department. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2011, 21, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Du, R.; Zhang, X. The current status of nurses’ psychological experience as second victims during the reconstruction of the course of event after patient safety incident in China: A mixed study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabdullah, H.; Karwowski, W. Patient safety culture in hospital settings across continents: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).