Abstract

Various complications of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNET) are reported, and an intratumor hemorrhage or infarct underlying pituitary apoplexy (PA) represents an uncommon, yet potentially life-threatening, feature, and thus early recognition and prompt intervention are important. Our purpose is to overview PA from clinical presentation to management and outcome. This is a narrative review of the English-language, PubMed-based original articles from 2012 to 2022 concerning PA, with the exception of pregnancy- and COVID-19-associated PA, and non-spontaneous PA (prior specific therapy for PitNET). We identified 194 original papers including 1452 patients with PA (926 males, 525 females, and one transgender male; a male-to-female ratio of 1.76; mean age at PA diagnostic of 50.52 years, the youngest being 9, the oldest being 85). Clinical presentation included severe headache in the majority of cases (but some exceptions are registered, as well); neuro-ophthalmic panel with nausea and vomiting, meningism, and cerebral ischemia; respectively, decreased visual acuity to complete blindness in two cases; visual field defects: hemianopia, cranial nerve palsies manifesting as diplopia in the majority, followed by ptosis and ophthalmoplegia (most frequent cranial nerve affected was the oculomotor nerve, and, rarely, abducens and trochlear); proptosis (N = 2 cases). Risk factors are high blood pressure followed by diabetes mellitus as the main elements. Qualitative analysis also pointed out infections, trauma, hematologic conditions (thrombocytopenia, polycythemia), Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and T3 thyrotoxicosis. Iatrogenic elements may be classified into three main categories: medication, diagnostic tests and techniques, and surgical procedures. The first group is dominated by anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs; additionally, at a low level of statistical evidence, we mention androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer, chemotherapy, thyroxine therapy, oral contraceptives, and phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors. The second category includes a dexamethasone suppression test, clomiphene use, combined endocrine stimulation tests, and a regadenoson myocardial perfusion scan. The third category involves major surgery, laparoscopic surgery, coronary artery bypass surgery, mitral valvuloplasty, endonasal surgery, and lumbar fusion surgery in a prone position. PA in PitNETs still represents a challenging condition requiring a multidisciplinary team from first presentation to short- and long-term management. Controversies involve the specific panel of risk factors and adequate protocols with concern to neurosurgical decisions and their timing versus conservative approach. The present decade-based analysis, to our knowledge the largest so far on published cases, confirms a lack of unanimous approach and criteria of intervention, a large panel of circumstantial events, and potential triggers with different levels of statistical significance, in addition to a heterogeneous clinical picture (if any, as seen in subacute PA) and a spectrum of evolution that varies from spontaneous remission and control of PitNET-associated hormonal excess to exitus. Awareness is mandatory. A total of 25 cohorts have been published so far with more than 10 PA cases/studies, whereas the largest cohorts enrolled around 100 patients. Further studies are necessary.

1. Introduction

Various complications have been reported in the relationships of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNET); an intratumor hemorrhage or infarct/infarction, also named pituitary apoplexy (PA), is a less common feature, yet with a life-threatening potential, thus its importance in early recognition and prompt intervention. Of historical note, hemorrhages associated with pituitary tumors were first described in 1898 by Pearce Bailey, and in 1950 the term “pituitary apoplexy” was introduced by Brougham et al. [1]. PA is a medical emergency presenting as sudden onset headache, loss of vision, ophthalmoplegia, and altered consciousness in relationship with a prior known or unknown pituitary mass, mostly PitNETs (usually a nonfunctioning adenoma, but also, hormonally active tumors with or without previous specific therapy) [1,2,3].

The incidence of PA in the general population varies from 0.2% to 0.6%, and from 2% to 12% in selected subgroups diagnosed with different types of PitNETs [4,5]. Males are affected more frequently than females; even though any age may be involved, most cases are reported within the fifth or sixth decade of life, whereas pediatric incidence remains very low [6,7].

The underlying mechanisms of PA are not completely understood yet. The classical hypothesis states that a rapidly growing tumor exceeds vascular supply [8]. Other potential contributors are vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), pituitary tumor-transforming gene (PTTG), matrix metalloproteinase-2/9 (MMP-2/9) or MMP-9, hypoxia-inducing factor (HIF-1α), a high proliferating index Ki-6 [9,10,11]; and high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a nuclear DNA-binding protein with pro-inflammatory effects [12].

In terms of clinical presentations, sudden headache, often with retro-orbital location, is one of the most common presenting symptoms of PA, with an incidence of 92% up to 100% of the patients [13]. The PA-associated mechanism includes traction of intracranial pain-sensitive structures such as the dura mater, cranial nerves, blood vessels, and meningeal irritation caused by blood and necrotic tissue [14]. Other frequent symptoms are ophthalmological complaints such as visual loss, diplopia, and ophthalmoplegia [15]. Specific hormonal anomalies, caused either by hormonally active PitNETs or by PA-induced or tumor-related hypopituitarism, may also be identified at the moment of PA diagnostic [16]. Arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, non-endocrine major surgical procedures, head trauma, infections, and certain drugs targeting the endothelium or clotting profile are PA-associated risk factors [16]. Hemorrhage in prolactinomas is another common scenario, especially under specific medical therapy [17,18]. Cavernous sinus invasion or the presence of a large macroadenoma may also increase the risk of developing PA [18,19]. Socioeconomic factors potentially play a role in the development of PA, yet, not unanimously accepted [20].

The imaging tests used as a diagnostic aid are mostly represented by computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [21]. Even though CT is used more often, MRI has a higher sensitivity [22]. The most commonly described MRI signs of PA are “sinus mucosal thickening” and “pituitary ring sign” [23]. Of note, the diagnostic of PA needs to be confirmed by imaging findings and/or associated post-operatory pathological profile after suspicion of PA is raised from a clinical presentation with regard to a neuroendocrine and/or neurologic point of view [21,22,23].

PA management involves a multidisciplinary team, as it is considered a neuroendocrine emergency. The main source of mortality is caused by acute adrenal insufficiency. Therefore, prompt glucocorticoid replacement is crucial [24]. However, the exact protocol still represents a subject of controversy. Early surgery is necessary for patients with severe visual loss since decompression may lead to a better recovery of visual dysfunction [25], but not necessarily to complete hypopituitarism recovery [26]. Other data did not identify any differences regarding the outcome of eye profile and hormonal imbalance when comparing surgical to conservative management [27,28].

Aim

Our purpose is to overview PA as a complication of a pituitary tumor, particularly PitNETs, from clinical presentation to management and outcome.

2. Method

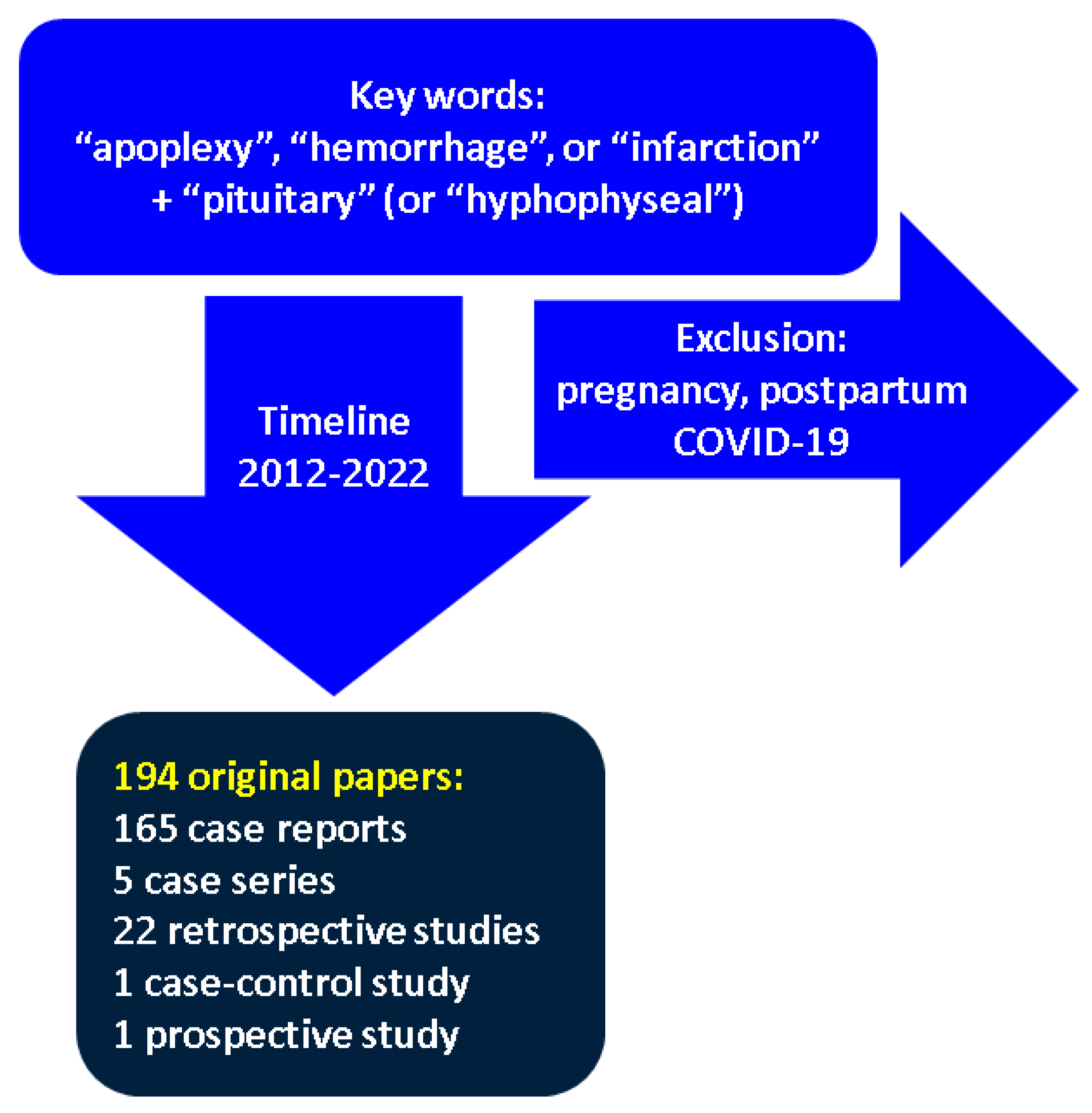

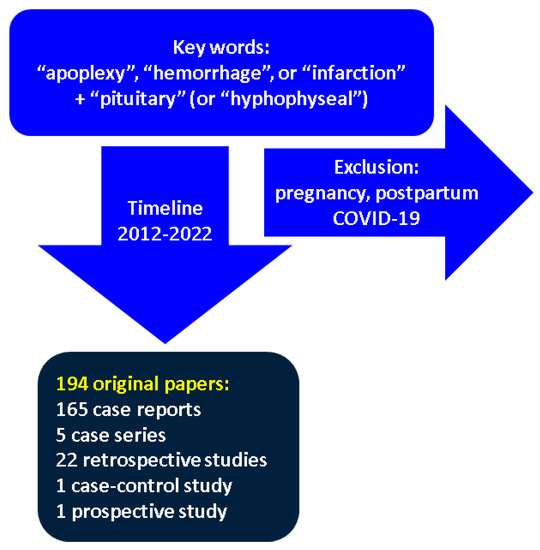

This is a narrative review of the English-language medical literature. Inclusion criteria are the following: clinically relevant papers concerning a PubMed-based search using the keywords “apoplexy”, “hemorrhage”, or “infarction” in association with “pituitary” (alternatively “hyphophyseal”); the timeline of publication is between 2012 and 2022; we included original research, either studies or case reports/series. Exclusion criteria were PA associated with the following circumstances: pregnancy and postpartum period, infection with coronavirus amid the recent COVID-19 pandemic, and non-spontaneous PA meaning PA associated with treatment for a prior known PitNET: neurosurgery, pituitary radiotherapy, and medication for hormonally active PitNETs, for instance, dopamine analogs (cabergoline, bromocriptine) for prolactinomas and somatotropinomas, respectively, somatostatin analogs (octreotide, lanreotide, and pasireotide), and growth hormone (GH) receptor antagonist pegvisomant for somatotroph PitNETs.

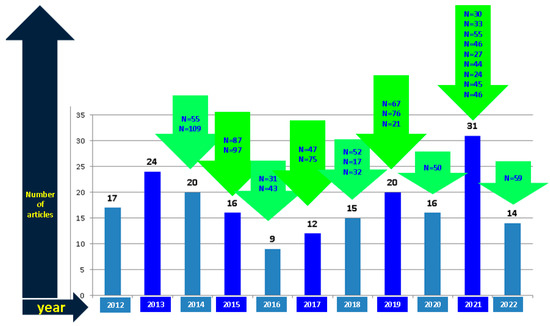

3. PitNET Complicated with PA

According to our methodology, we identified 194 original papers that included 165 case reports, 5 case series, 22 retrospective studies, one case–control study, and one prospective study. Overall, 1452 patients with PA were included (926 males, 525 females, and one transgender male). In accordance with medical literature, we found a male predominance (male-to-female ratio of 1.76). The mean age of patients was 50.52 years, the youngest was 9, and the oldest was 85 years [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222] (please see Table 1) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Original studies published between 2012 and 2022 concerning PA according to our methodology; the cited studies are displayed from 2012 to 2022; the data concern the clinical presentation and potential triggers of PA in addition to underlying pituitary disease (if any) [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222].

Figure 1.

Flowchart according to our methodology.

3.1. Clinical Presentation in Cases with PA: Neurologic and Ophthalmic Elements

Sudden headache was the most frequent symptom and occurred in more than two-thirds of patients. (Table 1) Headache was severe, often described as the most painful headache episode an individual has ever experienced, and graded, for example, as high as 9 on a scale from 0 to 10, with 10 being the most severe in one study [31]. For practical purposes we point out that headache was absent in some cases; thus, an index of suspicion should be provided by other endocrine and non-endocrine clinical elements [43,86,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216]. For instance, Enatsu et al. reported a 65-year-old woman admitted for a nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma-associated PA who presented third cranial nerve palsy and sudden decrease in visual acuity unaccompanied by headache [196]. Another example is a 65-year-old male who developed PA as a post-operative complication after a coronary artery surgery; he only presented diplopia and third cranial nerve palsy [214]. Other circumstances without headaches involve a comatose status. The case presented by Bhogal et al. involves a 63-year-old man with bradycardia and hypotension due to myxedema coma as part PA-associate hormonal picture [215]. Elsehety et al. reported a 60-year-old woman with vision loss and progression to coma due to an acute stroke as a surrounding event to PA [216].

Other common symptoms include nausea and vomiting, either with a neurological or endocrine component (acute secondary adrenal insufficiency) [25,29,30,33,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,174,176,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,217]. As mentioned, altered consciousness of various degrees up to coma was identified in 24 papers [56,64,70,79,93,97,100,103,111,112,114,122,123,141,151,169,174,177,189,209,210,215,216,218]. Weakness as a distinct clinical element was specified in five clinical cases (as a neurologic or endocrine consequence) [73,147,188,202,217].

Another important clinical finding is meningism, a crucial clue for differentiating between two life-threatening conditions: PA presenting as aseptic meningitis and bacterial meningitis. PA mimics neurological conditions, such as bacterial [30,37,39,59,63,78,83,106,119,168] or aseptic [100,176] meningitis, making differential diagnosis difficult. Both PA and meningitis share a similar clinical presentation with nuchal rigidity [30,59,70,78,83,119,168], positive Kernig and Brudzinski signs [37,78], fever [30,59,78,83], photophobia [39,70,83], and altered states of consciousness [30,83,106,176]. Moreover, laboratory findings consistent with bacterial meningitis, such as neutrophilic pleocytosis [30,39,59,78,119,176], and high protein content [39,59,83,119,176] were also observed in PA. In terms of glucose content of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), patients presented with normal [59,78,83,119] or high [176] levels in CSF. In spite of findings suggestive of bacterial meningitis, all CSF cultures were sterile [30,39,59,78,83,100,119,176]. In one case, differential diagnosis was particularly difficult [78]. Villar-Taibo et al. presented a patient with clinical presentation (nuchal rigidity, positive Kernig and Brudzinski signs, and fever) and CSF analyses consistent with bacterial meningitis, whose state improved under antibiotics. Following this event, the subject was diagnosed with PA based on MRI findings and pathological examination. The authors hypothesized that meningitis might have led to PA due to vasculitis. However, it remained unclear whether PA mimicked meningitis or if previous meningitis led to PA [78]. Considering that both PA and bacterial meningitis can be life-threatening, prompt differential diagnosis and treatment are essential. Current findings suggest that the presentation of a clinical picture suggestive of meningitis includes differential diagnosis with PA, especially in patients with sterile CSF, knowing that PA may cause aseptic, irritant chemical, bacterial-like meningitis [39].

PA may associate cerebral ischemia through either extrinsic compression or vasospasm, leading to neurological deterioration (mental status changes, motor deficits, speech impairment) in patients who suffered from acute ischemic stroke following PA [79,107,146,199].

PA-associated visual disturbances include decreased visual acuity in most cases [11,25,31,32,33,37,57,70,75,80,93,96,97,98,101,102,105,110,113,120,121,128,135,146,168,177,187,190,196]. Complete blindness was reported in two papers [199,212]. Visual field defects varied from (mostly common) hemianopia [33,39,55,80,126,135,179,187,197] to cranial nerve palsies manifesting as diplopia in the majority of these cases [32,34,35,49,50,58,63,66,68,75,84,85,91,92,114,115,117,127,130,142,147,150,157,163,164,186,191,194,195,207,214] followed by ptosis [34,35,50,59,75,77,79,92,107,146,157,191,199,206] and ophthalmoplegia [47,52,95,140,158,172,190,209]. The most frequent cranial nerve affected was the oculomotor nerve, but rarely, patients also presented with abducens [25,44,77,81,84,85,91,98,113,120,121,123,124,128,142,168,174,182,192,207] and trochlear [25,63,81,84,102,121,123,124,149,168,182,209] nerves palsies. Optic chiasm compression was specified in 18 articles [32,33,46,55,62,63,65,69,80,123,125,169,177,185,186,191,192,218] or, rarely, an invasion of the cavernous sinus [44,63,65,196]. Interestingly, two patients, a 45-year-old male [34] and a 71-year-old female [207] were admitted for PA-associated proptosis.

3.2. PA and Hormonal Imbalance at First Diagnostic

Endocrine features in subjects admitted for PA include PitNETs-associated hormonal excess, even though most patients were nonfunctioning tumors, respectively, tumor- or PA-caused hypopituitarism (as mentioned, we did not include patients with previously recognized and treated PitNETs). In terms of clinical presentation, Cushingoid features (corticotroph PitNET) are reported in 5 studies (less than 0.005% of the patients): two males of 30, respective 33 years [31,186], a cases series of 4 females aged between 26 and 45 years [33], and other two women of 35, respective 47 years [86,161]. Acromegaly (caused by somatotroph or lactosomatotroph PitNET) was recognized in 8 patients (0.005%) aged between 26 and 50 years; a male [86,109,136,148,156,217] to female [38,78] ratio of 6 to 2. One case of gigantism (+5 SD) was reported on a 9-year-old boy with lactosomatotroph PitNET [32]. Hypopituitarism included elements of hypogonadism [127,128,129,131,135] like disturbances of menstrual cycle in women of reproductive age [171,172], etc., but, also, with a more severe potential, hypotension [29,48,83,199,210,213].

Other signs and symptoms at PA presentation include lactotroph PitNET-associated galactorrhea [141,174,183]; hyperthermia [180], pruritic skin rash associated with central adrenal insufficiency-related cortisol deficit [185], hiccups [109], epistaxis [91], hematuria [189], phonophobia [78], visual illusions [45], and symptomatic diabetic ketoacidosis [53,171,172].

In terms of the PitNET stain profile (regardless clinical expression) non-functional type was followed by somatotroph PitNETs [32,38,42,46,53,56,66,76,78,86,92,93,98,100,108,109,121,128,136,141,148,152,156,166,168,169,171,175,192,217], lactotroph PitNETs [66,75,77,90,98,100,113,121,126,128,141,166,168,169,174,175,183,202,206], gonadotroph PitNETs [71,72,77,88,91,98,99,101,105,113,114,128,179,185,187,203,221], corticotroph PitNET [31,33,92,98,100,103,118,121,128,137,144,154,155,168,174,184,186,208,220], lactosomatotroph [32,100,109], and thyrotroph PitNETs [61,92,100,105]. Other pathologic features of pituitary masses complicated with PA include: Crooke cell adenoma [130,161], tumor with switching phenotypes [143], malignant spindle and round-cell tumor [91], Rathke’s cyst [70,194], primitive neuroectodermal tumor [70], craniopharyngioma [70], and pituitary metastasis from squamous cell carcinoma [35], melanoma [55], lung and bronchogenic carcinoma [70,73], respectively, and breast carcinoma [62,187].

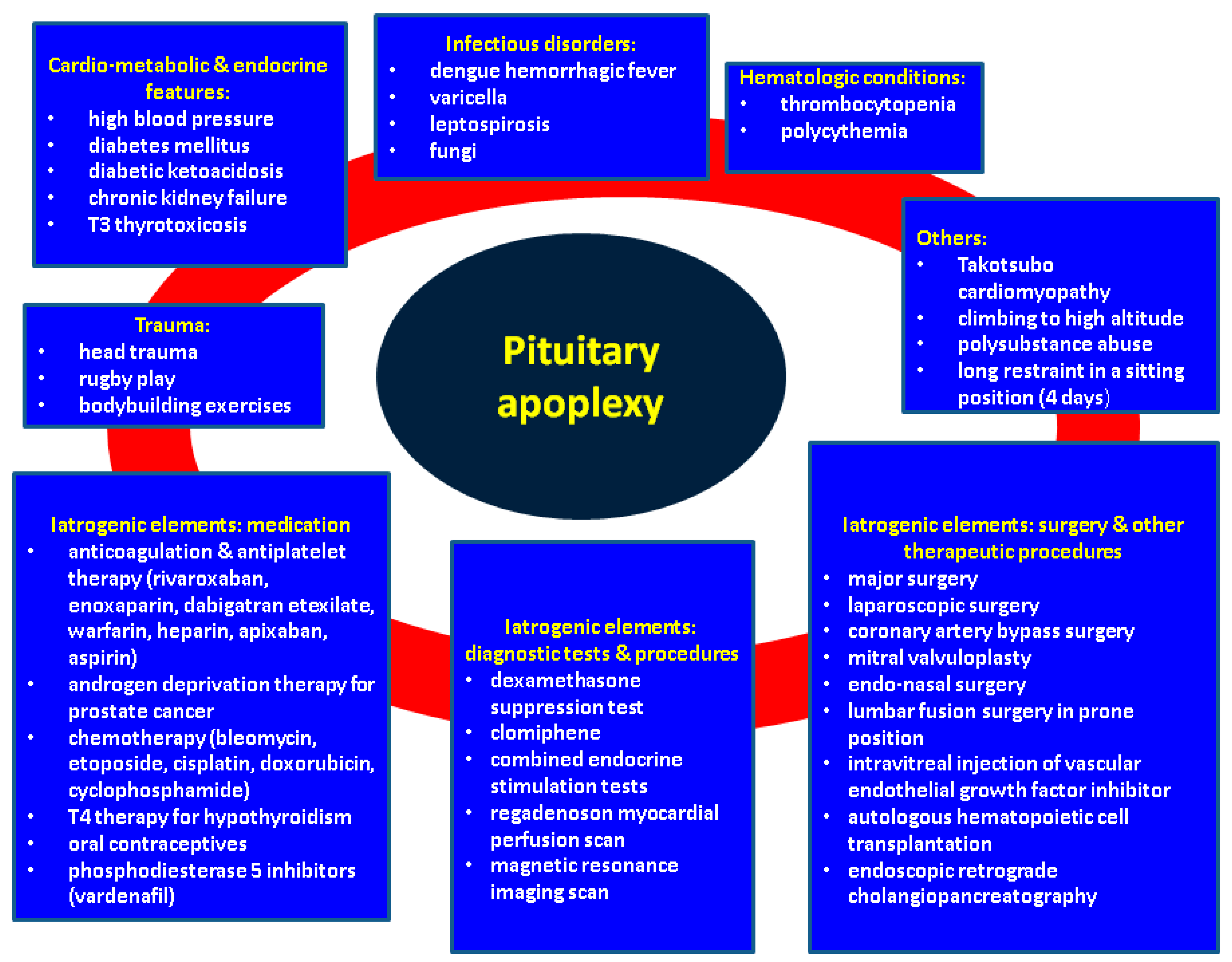

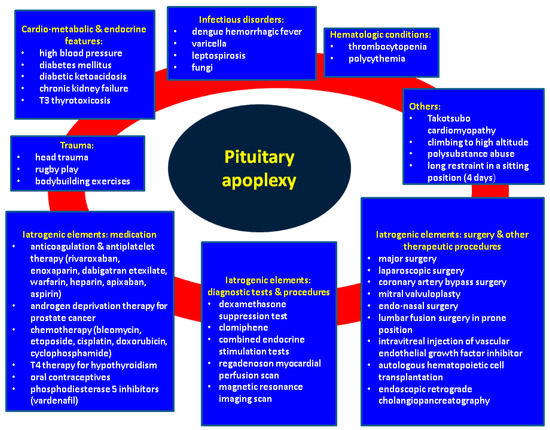

3.3. Potential Triggers and Circumstantial Events of PA

Our decade-based analysis showed that high blood pressure may be regarded as the most frequent co-morbidity (or risk factor) followed by diabetes mellitus in individuals admitted for PA. (Table 1) Two cases reported severe, complicated diabetes with diabetic ketoacidosis [53,171,172], and chronic kidney failure [59]. Another endocrine contributor was T3 thyrotoxicosis in one patient [71].

Infectious triggers were also found and include pituitary fungal infection [144], dengue hemorrhagic fever [42,74,77,103,139], varicella [208], and leptospirosis [163]. Of note, Catarino et al. presented the case of a 55-year-old woman who suffered from a corticotroph PitNET-associated PA in relationship to a fungal infection that was surgically treated without anti-fungal treatment [144]. Dengue hemorrhagic fever led to PA in five patients. The underlying mechanism is thrombocytopenia which favors bleeding at the level of PitNET. All patients had pituitary adenomas, with one corticotroph PitNET [103], one somatotroph PitNET [42], and one lactotroph–gonadotroph PitNET [77]. Three patients underwent transsphenoidal surgery (TSS) [42,74,103], one patient was treated conservatively [139], and another patient underwent TSS after initial conservative treatment with cabergoline and dexamethasone due to visual deterioration [77]. The 56-year-old patient introduced by Gohil et al. presented leptospirosis; the proposed mechanisms through which leptospirosis might induce PA include non-inflammatory vasculopathy, as well as platelet dysfunction, rather than thrombocytopenia [163]. An interesting finding was conducted by Humphreys G et al., who analyzed in a prospective study the sphenoid sinus mucosal microbiota characteristics in 10 patients with PA. The authors observed abnormal sinus bacteria like Enterobacteriaceae in patients with PA [105].

Traumatic causes are identified; for instance, head trauma [30,160,204], recent rugby play without an actual head trauma [168], and bodybuilding exercises [106].

Anticoagulation [25,64,66,70,128,135,138,160,166,173,195,198] and antiplatelet therapy [90,94,97,113,141,160,166,169] are the most important iatrogenic elements. For instance, we mention rivaroxaban, enoxaparin, dabigatran etexilate, warfarin, heparin, apixaban, and aspirin. Other vascular and clotting triggers include Takotsubo cardiomyopathy [213], heparin-induced thrombocytopenia [35], thrombocytopenia of other causes [97,208], and polycythemia [108]. Medical treatments in point are further on (at the statistical level of rare case reports): androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer [52,88,99,157,168], systemic chemotherapy like bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin [184], doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide [207], and thyroxine therapy [61].

Oral contraceptives may contribute to PA [54]. Kobayashi et al. presented a 33-year-old female with ischemic PA of a nonfunctioning macroadenoma following the use of oral contraceptives for 1.5 years. The patient fully recovered under conservative treatment with analgesics and hormone replacement with hydrocortisone and thyroxine. The hypercoagulable state induced by estrogens was hypothesized as an underlying mechanism of PA [54]. Additionally, a vardenafil-triggered PA was reported [140]. Uneda et al. reported a 51-year-old male with signs and symptoms of PA (severe headache and oculomotor nerve palsy) the morning after taking vardenafil for erectile dysfunction for the first time in three months. He was diagnosed with apoplexy of a pituitary adenoma based on CT and MRI findings and was surgically treated. Even though the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, possible mechanisms of PA under phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE) inhibitors are hypotension, vasodilation, and antiplatelet effects [140].

Iatrogenic components may include diagnostic tests and procedures: dexamethasone suppression test [118], clomiphene use [66], combined endocrine stimulation tests [43], regadenoson myocardial perfusion scan [153], and MRI scan [46]. Among non-pituitary-surgery-related triggers, we identified major surgery [66,128,132,168,201], laparoscopic surgery [199], coronary artery bypass surgery [34,66,214], mitral valvuloplasty [84], endonasal surgery [127], and lumbar fusion surgery in prone position [80,116]. Interestingly, Naito Y et al. reported a case of PA in a 14-year-old girl with Carney complex who underwent successful resection of a cardiac myxoma, but the day after surgery she experienced headache and visual disturbances requiring urgent surgical decompression for PA [132].

Other therapeutic procedures include the intravitreal injection of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor [204], autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation [152], endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [124], and radiotherapy [113,166].

Two case reports presented individuals with PA caused by exposure to high altitudes (the first case was published in 2012). Both subjects were 29-year-old males without underlying pituitary conditions who ascended slowly to altitudes of over 4500 m. The initial diagnosis was acute mountain sickness in both cases. However, due to low blood pressure and findings of adrenal insufficiency, PA was suspected, and later MRI scans confirmed PA. Neither patient displayed visual disturbances [29,48]. The management included transfer to a lower altitude (as a specific approach in this distinct type of PA) as well as glucocorticoid replacements (100 mg of hydrocortisone every eight hours, the first two days, followed by 7.5 mg of prednisolone daily due to persistent hypocortisolism [29], respective 100 mg of hydrocortisone every six hours followed by full recovery [48].

Of note, two unusual triggers are polysubstance abuse [191] and long restraint in a sitting position [221]. The patient presented by Sun et al., a 49-year-old male, died in custody due to a gonadotroph PitNET-associated PA following restraint in a sitting position for four days [221] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Qualitative analysis of potential contributors to spontaneous PA in PitNETs that are not previously treated (outside pregnancy and coronavirus infections). Abbreviations: T3 = triiodothyronine; T4 = thyroxine.

3.4. PA Management

The management of the patients recognized with PA is summarized in Table 2. Essentially, the subjects were managed surgically (80%) or conservatively. Although the majority are TSSs, five papers introduced patients undergoing craniotomies [36,60,127,159,217]. Craniotomies were necessary for intracranial hemorrhage [36], subarachnoid hemorrhage [60], previous nasal surgery [127], and technical challenges such as cavernous sinus invasion with encasement of the internal carotid artery [159], respectively, encasing of both carotid arteries [217].

Table 2.

Management and outcome in patients PitNET–PA [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222].

Conservative management [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,218,219,220] included vital signs monitoring, hydro-electrolytic balance, glucocorticoid substitution (intravenous hydrocortisone during the first 48 h followed by oral replacement), as well as substitution with levothyroxine and desmopressin (if needed) [123,168]. A management decision was based on the severity of clinical presentation and progression of the neurologic, eye, and hormonal features. The patients analyzed by Marx et al. were treated surgically when they presented severe visual acuity decrease, worsening of ophthalmological symptoms, resistant headache, or altered consciousness [168]. Similar criteria were applied by Almeida et al. and Bujawansa et al. [66,123]. Clinically stable individuals remained under a conservative approach [66,123,168], as well as subjects to contraindications for performing neurosurgery [123] or those refusing it [218].

A few cases under the “wait and see” approach were later referred to TSS due to worsening conditions: hematoma expansion [51] or sudden visual deterioration [77,158].

We identified three clinically relevant studies that compared conservative management versus TSS in terms of evolution [123,160,168]. Almeida et al. found that visual, cranial nerve, and endocrine outcomes are similar between the two subgroups [123]. Cavalli et al. analyzed the clinical presentation, surgical methods, and treatment outcomes of patients with PA. The authors advocated for conservative management in patients without visual impairment and suggested that a tumor with a vertical diameter greater than 35 mm should be referred to neurosurgery in the presence of visual deficits. The only statistical difference between surgically treated patients and patients under conservative treatment was the higher ratio of achieving resolution of visual field defects at the latest follow-up in the group who underwent emergency surgery [160]. Marx et al. found that following surgery, a higher number of patients presented adrenal insufficiency and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism than those who were managed conservatively, but no statistically significant difference was identified in terms of visual acuity and visual field consequences [168]. Bujawansa S et al. suggested conservative treatment as a safe and adequate approach for selected patients (those with mild and non-progressive neuro-ophthalmic defects) [66]. The findings suggest that surgical treatment wields a higher risk of associating endocrine deficiencies [168], but a higher ratio of visual field defects improvement [161], but with similar outcomes in terms of visual acuity [123,160,168].

We mention some isolated reports with uncommon management such as radiotherapy for a subject diagnosed with a null cell tumor and a gonadotroph PitNET [105]; palliative care with dexamethasone and brain radiotherapy for an individual diagnosed with bronchogenic carcinoma metastases-associated PA [73]; transfer to a lower altitude, as prior mentioned, in specific cases with climbing-induced PA [29,48]; for an intraorbital-induced PA, the patient was offered orbital surgery, preceded by embolization through direct puncture techniques combined with a transarterial approach via the right ophthalmic artery [206]. Additionally, functional PitNET continued medical therapy for specific hormonal excess with cabergoline [75,77,168,170,199,218] or somatostatin analogs [76].

3.5. PA-Related Outcome

A large number of patients required hormonal replacement due to PA-associated hypopituitarism manifested as hypocortisolism which is the most important aspect in terms of an immediate life-threatening approach [25,29,30,31,56,65,66,75,80,90,92,123,128,144,163,168,169,208], central hypothyroidism [25,56,65,66,72,75,101,109,123,144,163,168,169,180,184,200], and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism [25,56,65,66,72,109,128,168,169,180,198]. GH deficiency was also reported [109,128,168], whereas spontaneous acromegaly remission was reported in four papers [46,136,156,208] or partial improvement of acromegaly-related GH excess [78]. Long-term therapy with desmopressin for permanent diabetes insipidus was reported, as well as [25,31,55,66,78,90,91,111,112,113,127,128,182]. Microadenomas underlying PA had a better clinical (including endocrine) outcome when compared to macroadenomas which are also associated with a higher rate of multiple hormonal deficiencies [169]. A retrospective study by Ogawa Y et al. found that ischemic rather than hemorrhagic lesions in PA correlated with an increased progression rate [100].

As mentioned, some small studies evaluated the outcome in terms of conservative versus neurosurgical management. A retrospective study (N = 46 patients with PA) showed that individuals with non-severe neuro-ophthalmological deficits were treated conservatively (N = 27), whereas the patients with a pituitary apoplexy score (PAS) ≥4 were treated surgically (N = 19); the only statistically significant difference regarding the outcome was the higher rate of hormonal deficits in the second group [168]. Another study included 49 subjects who were referred for neurosurgery and 18 patients who were conservatively managed and showed similar improvement in visual and cranial nerve palsies [123]. A retrospective study (N = 24 subjects who underwent TSS) showed a complete tumor resection in 87.5% of cases; 94.44% of patients experienced an improvement of visual acuity; diabetes insipidus developed in 16.66% of individuals [174].

The timing of surgery was also taken into consideration by some studies, as a contributor to PA outcome. A study conducted by Rutkowski M et al. (N = 32 patients with acute PA who underwent TSS) included two groups depending on surgery timing: within 72 h of symptom onset and after 72 h; the second group had a statistically significant higher prevalence of hypopituitarism at presentation. However, in terms of hypopituitarism and visual dysfunction recovery, the outcome was similar [121].

The spontaneous resolution of PitNET through PA was reported with a favorable outcome [87,126,154,220]. Ghalaenovi H et al. published the case of a 28-year-old male with spontaneous regression of a nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma over the course of one year with the spontaneous resolution of headache, bitemporal hemianopia, and photophobia [126]. Machado et al. presented a 36-year-old female with spontaneous resolution of a corticotroph PitNET with symptoms remission within 28 months (conservative approach) [220]. Siwakoti et al. introduced a 59-year-old woman with tumor shrinkage and biochemical remission of Cushing’s disease through conservative treatment [154]. Tumor resolution with empty sella following conservative management was reported by Saberifard et al. [87].

Fatal outcome surrounding PA was registered as an early event, for instance, within 48 h [38] or after 5 years since initial TSS [91]. Overall, we identified 14 publications [35,36,38,60,62,90,91,92,100,133,182,187,216,221]. Some of the subjects were comatose at presentation [36,38,60,216], PA causing an intracerebral hemorrhage [36]; similarly, one case of the following is reported: fulminant heparin-induced thrombocytopenia [182]; fatal outcome 12 days following TSS due to sepsis [187]; or 3 months since PA in a patient with breast cancer [62] or leukemia [100]. Interestingly, two studies reported a mortality death of 1.03% (N = 97) [92], respective of 4.6% (N = 87) [90].

Of note, we identified through our analysis a single case of PA in the transgender population: a 46-year-old transgender male under testosterone therapy for 3 years who was admitted for severe headache, central hypocortisolism, and hypothyroidism. IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor) levels, however, were high. The patient was diagnosed with somatotroph PitNET-associated PA and received surgical treatment with normalization of IGF-1 and improvement of secondary diabetes mellitus. Particularly, testosterone therapy in this situation may mask acromegaly features [76] (please see Table 2).

4. Discussion

4.1. Subentities concerning PA

An unusual case of “pneumo-apoplexy” was described by Singhal A et al.; a 65-year-old female had a PA-associated hemorrhage accompanied by pneumosella and manifested as rhinorrhea as well as classical symptoms of PA including headache and visual loss. The patient needed flap replacement of the nasoseptal defect [137].

“Recurrent” apoplexy was reported by Hosmann A et al. in 4 out of 76 patients (5.3%) after initial neurosurgery. Potential factors include residual post-operatory tumor, cavernous sinus invasion of PitNET, and ophthalmoplegia [128]. However, a recurrent tumor after initial TSS due to PA-PitNET may be found as seen in the general population with PitNET who were previously candidates for neurosurgery [145,168].

Some patients presented “subacute” PA, with little to no symptoms, thus the importance of imaging assessments like MRI scans that point out infarction or hemorrhage [166]. The term “subacute” is used for PA associated with clinical symptoms less severe than fully manifested (or “acute”) PA, thus the importance of awareness since many cases may be under-diagnosed [166,222]. Iqbal F et al. published a retrospective analysis on 55 patients (33 with acute PA and 22 with subacute PA). Severe headache and hyponatremia were more frequent in the acute group whereas the ratio of individuals who were referred to surgery was similar between the two subgroups [166]. Garg M et al. described the case of a 22-year-old female with vision reduction as the single symptom [197]. Klimko A et al. also reported a 41-year-old acromegalic male with subacute PA and panhypopituitarism [148].

4.2. Controversies in PA Domain

PA is an emergency that typically presents a sudden and severe headache and visual symptoms; however, subacute cases or those without headaches should not be missed. The most frequent cause is hemorrhage or ischemia in a nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma, but hormonally active PitNET may embrace a PA scenario. Middle-aged males are affected with the highest frequency, but both pediatric and elderly cases are shown in Table 1. The most common risk factors are high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, and anticoagulation/antiplatelet therapy; however, at the level of case reports, uncommon conditions are reported as we prior pointed out. (Table 1) Differential diagnosis is sometimes crucial, as PA can mimic a number of conditions including meningitis or temporal arteritis [134]. Controversies around the exact panel of PA contributors still exist since there are still pathogenic elements that remain unclear. Whether the mentioned comorbidities as displayed in Figure 1 are directly connected to PA or are incidental is still a matter of debate.

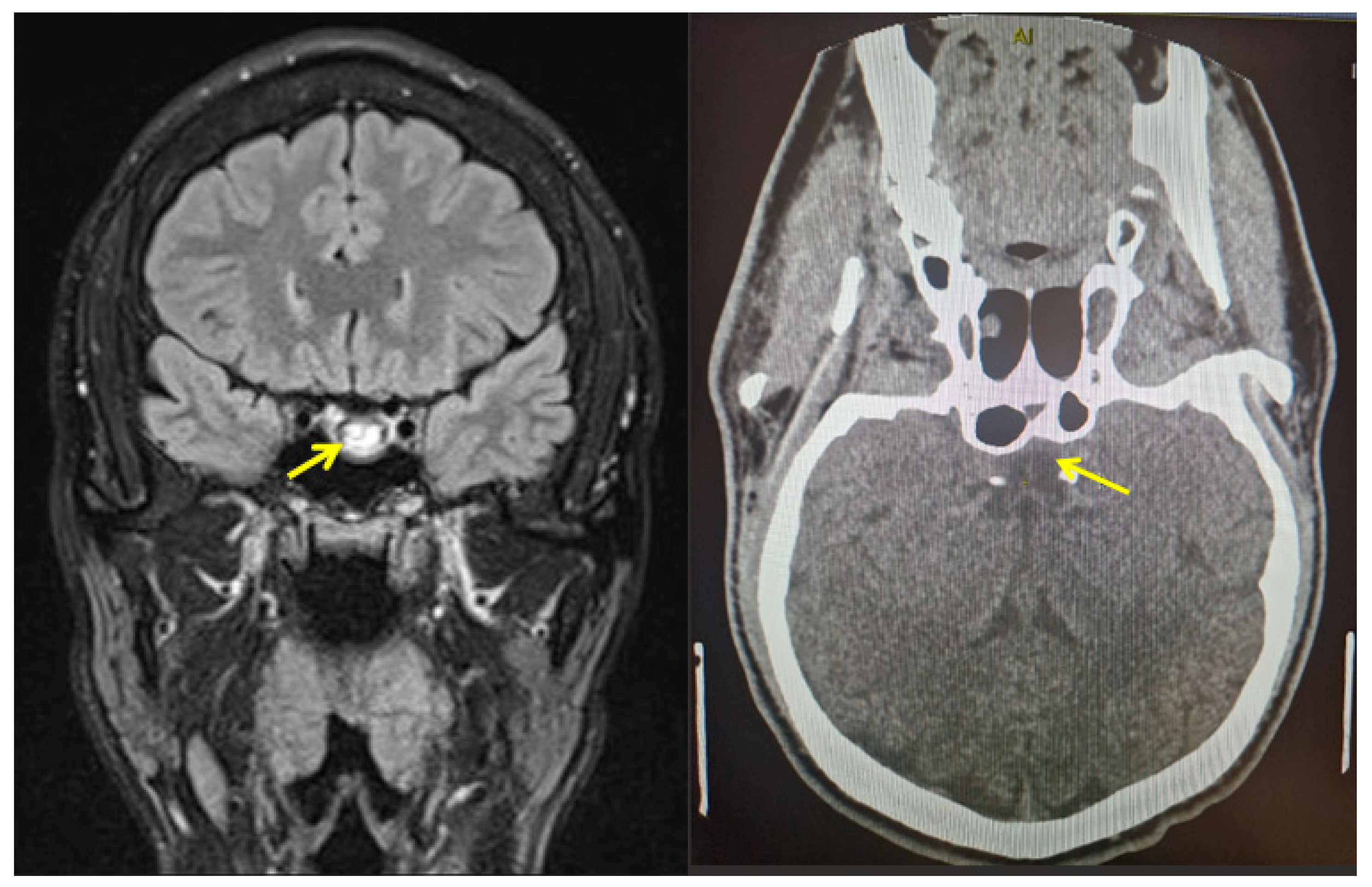

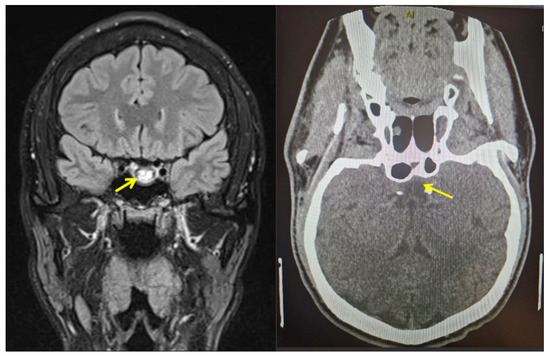

The optimal treatment approach remains debated, but the main treatment options are TSS or conservative management. Due to possible complications from surgery, as well as a higher rate of pituitary insufficiencies after surgical treatment when compared with conservative management, careful evaluation is necessary. The individual multidisciplinary decision is mandatory. Surgical management should be reserved for patients with visual impairment due to cranial nerve palsies and optic chiasm compression, or patients with other neurological deficits. Conservative treatment is usually an adequate approach for stable patients with mild and stationary visual deficits and without further neurological impairments. When choosing conservative management, the risk of PA recurrence should also be taken into account. (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Imaging capture of a pituitary apoplexy. This is a male patient in his late 20s diagnosed with pituitary apoplexy with no prior medical or surgical history. On first presentation as an outpatient (due to severe headache), magnetic resonance imaging (performed as an emergency) shows a pituitary mass of 2.5 cm maximum diameter with inhomogeneous pattern suggesting hemorrhage (yellow arrow) at the level of a pituitary tumor (left). Intravenous contrast computed tomography (10 months since transsphenoidal surgery) shows a tendency to empty sella and no tumor remnants (yellow arrow) at the same level (right). Both captures are coronal plane.

In terms of outcome, headaches and visual disturbances may resolve following both conservative and surgical treatment. Patients can present different degrees of anterior hypopituitarism and diabetes insipidus. Factors for a worse prognosis may be the presence of a large macroadenoma and an ischemic type of apoplexy. PA is a condition that can lead to a favorable outcome with the remission of symptoms and underlying pituitary disorder in some patients, whereas for others it can be life-threatening and invalidating when fatal cases are reported (as we already mentioned). Specific algorithms of management are still necessary.

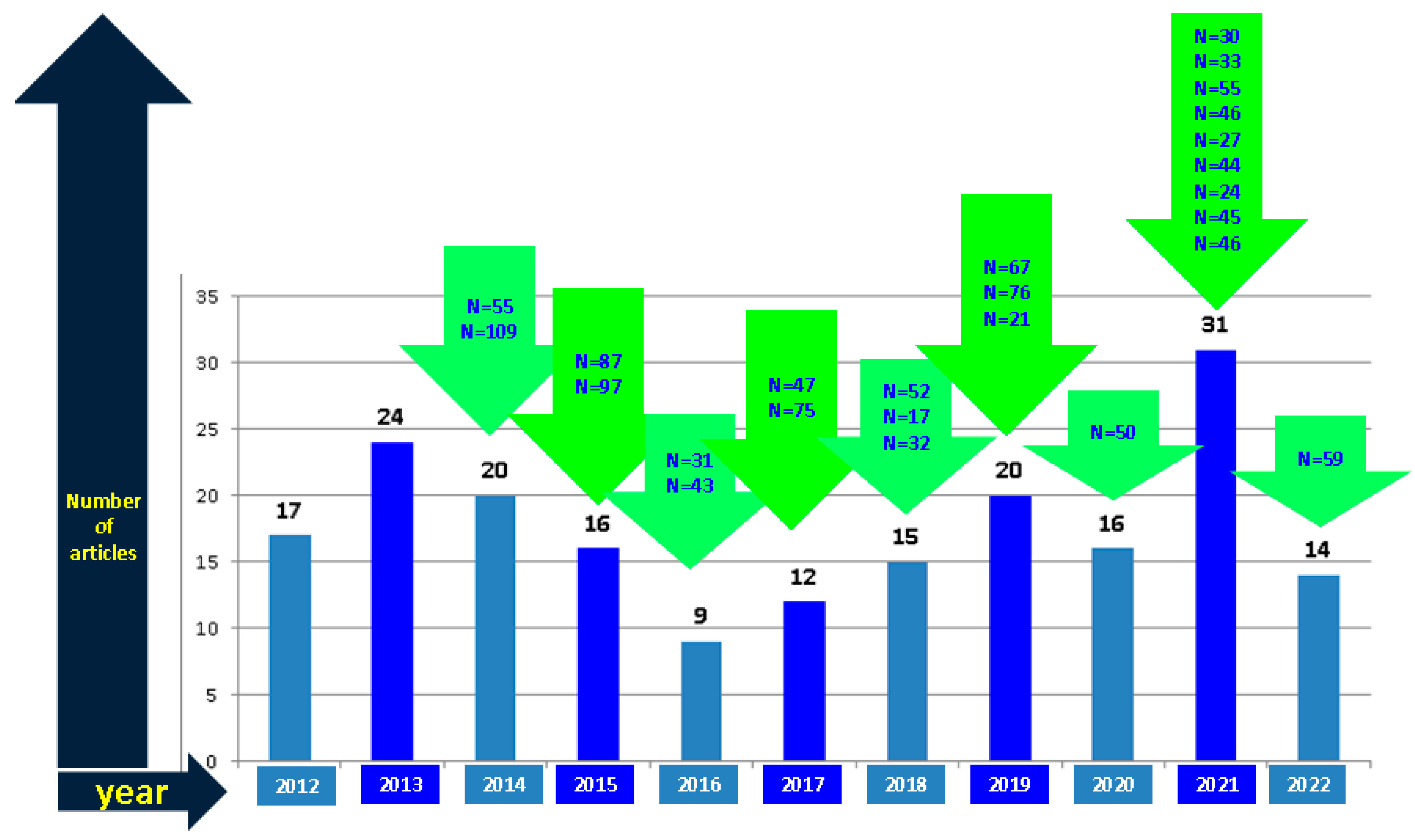

To our knowledge, this is the largest analysis of published cases concerning spontaneous PA (outside pregnancy and COVID-19 infection). A timeline of published papers from 2012 to 2022 according to our methodology is displayed below. The largest studies addressing individuals with PA included 109, 97, and 87 subjects, respectively [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222]. (please see Table 1 and Table 3 and Figure 4)

Table 3.

Retrospective studies with minimum 10 patients confirmed with PA/study according to our methodology [25,66,70,90,100,111,112,113,120,121,123,128,141,151,160,162,166,168,169,174,181,182,183].

Figure 4.

The timeline of original papers specifically addressing PA according to our methodology: the sample size analysis of original publications (please see references according to Table 1).

Abbreviations: N represents the number of patients included in studies with at least 10 subjects with PA per article (of note: in Table 1 we used the term “case series” or “study” according to the original publication; in this figure, we strictly included the original research depending on the number of patients).

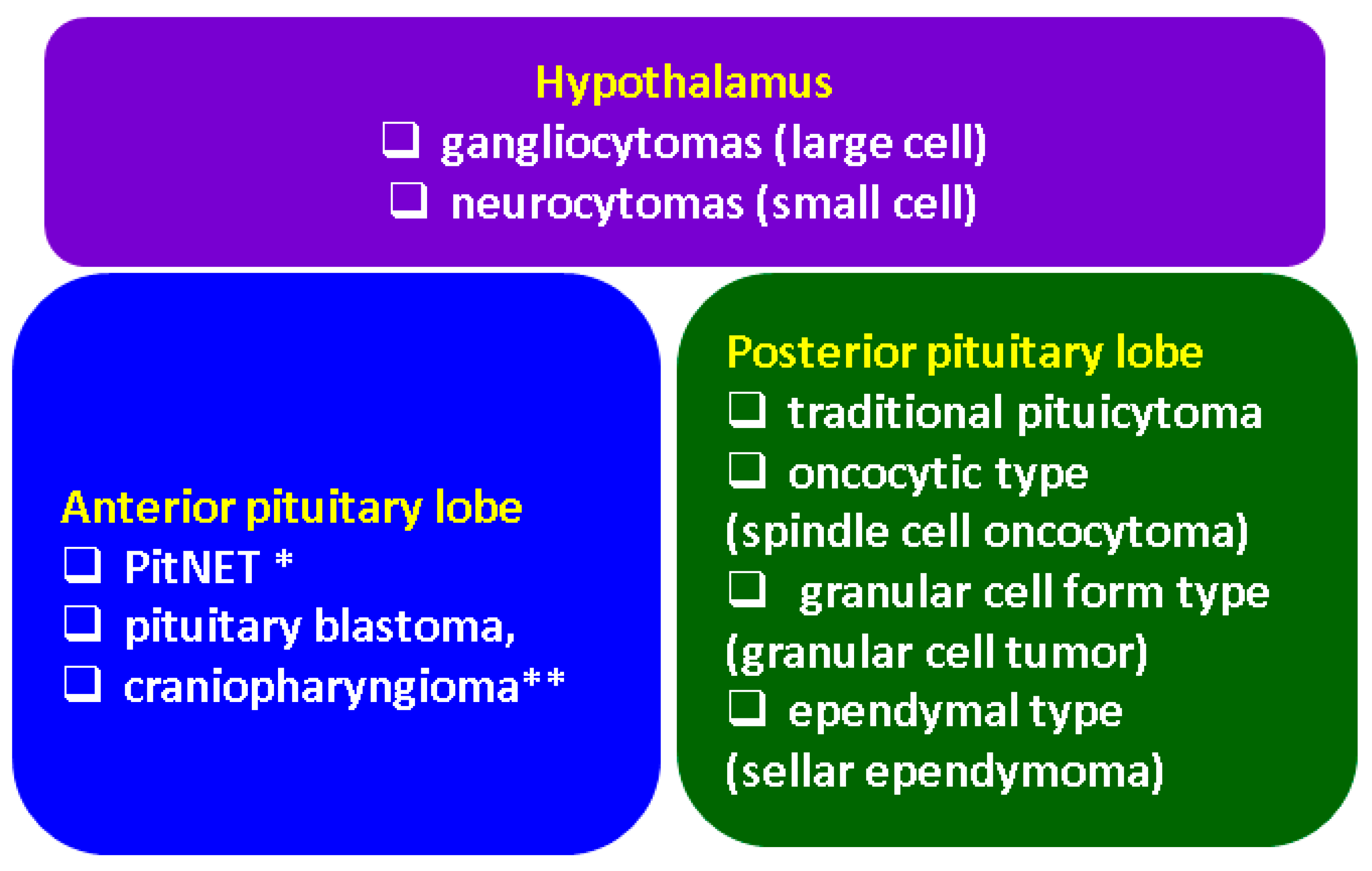

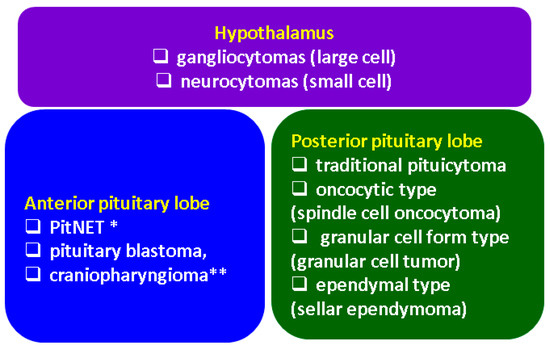

Notably, PitNETs terminology and associated concepts massively changed since the WHO 2022 classification. Our 10-year analysis included cases with PA in relationship with different tumors that were diagnosed according to the criteria at that time. Recently, “PitNET” replaced “pituitary adenoma” which, however, is still allowed to be used. Grossly, there are three types of tumors arising from the anterior lobe: PitNET, pituitary blastoma, and craniopharyngioma (two specific subtypes). The modern approach of these tumors massively takes into consideration the role of immunohistochemistry for mainly five elements: PIT1, TPIT, SF-1, GATA3, and ERα in order to profile PitNET subtypes. The major changes are, a part form this new terminology: null cell tumors and unclassified pluri-hormonal tumors as a subtype of PitNETs with negative staining for transcription factors; “metastatic” PitNET replaced “metastatic carcinoma” that should be differentiated from a neuroendocrine carcinoma; immature (formerly “silent”) or mature PIT1-lineage tumor are determined based on PIT1 immunostaining; and mammosomatotroph, acidophil stem cell tumors in addition to mixed somatotroph/lactotroph tumors are distinct types with respect to PIT-1 lineage of PitNET [223,224,225,226] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Integrating hypothalamic–pituitary tumors to new WHO 2022 criteria [223,224,225,226]. PitNET = pituitary neuroendocrine tumors; * well-differentiated adenohypophyseal tumors (formerly pituitary adenomas); ** two specific subtypes.

4.3. Limitations

We acknowledge that the current review did not follow the PRISMA guidelines for systematic review and may have missed some studies because only PubMed was used for the literature search.

5. Conclusions

PA in PitNETs still represents a challenging condition requiring a multidisciplinary team from first presentation to short- and long-term management. Controversies involve the specific panel of risk factors and adequate protocols with concern to surgical decisions and their timing. The present decade-based analysis, to our knowledge the largest so far on published cases, confirms a lack of unanimous approach and criteria of intervention, a large panel of circumstantial events and potential triggers with different levels of statistical significance, in addition to a heterogeneous clinical picture (if any, as seen in subacute PA) and a spectrum of evolution that varies from spontaneous remission and control of PitNET-associated hormonal excess to exitus. Awareness is mandatory. A total of 25 cohorts have been published so far with more than 10 PA cases/studies, whereas the largest cohorts enrolled around 100 patients. Further studies are necessary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-M.G., A.I.T., M.C. and M.S.; methodology, A.-M.G., A.I.T., M.C., C.N. and M.S.; software, A.-M.G., N.I., M.C. and F.L.P.; validation, A.-M.G., A.I.T., M.C. and C.N.; formal analysis, A.I.T., N.I., C.N., F.L.P. and M.S.; investigation, A.-M.G., A.I.T., N.I., M.C. and M.S.; resources, N.I., C.N., F.L.P. and M.S.; data curation, A.-M.G., A.I.T., N.I., M.C., C.N. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-M.G. and A.I.T.; writing—review and editing, A.-M.G., A.I.T., M.C. and M.S.; visualization, N.I., M.C., C.N. and F.L.P.; supervision, M.C., C.N. and M.S.; project administration, A.-M.G., A.I.T., M.C. and M.S.; funding acquisition, M.C., C.N. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient who provided us with the imaging captures from his own personal records.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CT | computed tomography |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| HIF-1α | hypoxia-inducing factor |

| HMGB1 | high-mobility group box 1 |

| HR | hormonal replacement |

| GH | growth hormone |

| IGF-1 | insulin-like growth factor |

| MMP | matrix metalloproteinase |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| PA | pituitary apoplexy |

| PAS | pituitary apoplexy score |

| PitNET | pituitary neuroendocrine tumor |

| PDE | phosphodiesterase |

| PTTG | pituitary tumor-transforming gene |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TSS | trans-sphenoidal surgery |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Pearce, J.M. On the Origins of Pituitary Apoplexy. Eur. Neurol. 2015, 74, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, W.L.; Dunn, I.F.; Laws, E.R. Pituitary apoplexy. Endocrine 2015, 48, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo-Castro, M.; Berrocal, V.R.; Pascual-Corrales, E. Pituitary tumors: Epidemiology and clinical presentation spectrum. Hormones 2020, 19, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, K.D. Pituitary apoplexy: Is it one entity? World Neurosurg. 2014, 82, 608–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkhoudarian, G.; Kelly, D.F. Pituitary Apoplexy. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 30, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente, A.; Lecumberri, B.; Gálvez, M. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pituitary apoplexy. Endocrinol. Nutr. 2013, 60, 582.e1–582.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, P.P.; Crawford, J.R.; Khanna, P.; Malicki, D.M.; Ciacci, J.D.; Levy, M.L. Pituitary tumor apoplexy in adolescents. World Neurosurg. 2015, 83, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glezer, A.; Bronstein, M.D. Pituitary apoplexy: Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2015, 59, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Dutta, P. Landscape of Molecular Events in Pituitary Apoplexy. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, B.; Gerez, J.; Haedo, M.; Fuertes, M.; Theodoropoulou, M.; Buchfelder, M.; Losa, M.; Stalla, G.K.; Arzt, E.; Renner, U. RSUME is implicated in HIF-1-induced VEGF-A production in pituitary tumour cells. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2012, 19, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, T.; Sangtian, J.; Ruanpeng, D.; Tummala, R.; Clark, B.; Burmeister, L.; Peterson, D.; Venteicher, A.S.; Kawakami, Y. Acute elevation of interleukin 6 and matrix metalloproteinase 9 during the onset of pituitary apoplexy in Cushing’s disease. Pituitary 2021, 24, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, T.; Fujita, M.; Kato, A. Significance of Elevated HMGB1 Expression in Pituitary Apoplexy. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 4491–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreitschmann-Andermahr, I.; Siegel, S.; Carneiro, R.W.; Maubach, J.M.; Harbeck, B.; Brabant, G. Headache and pituitary disease: A systematic review. Clin. Endocrinol. 2013, 79, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suri, H.; Dougherty, C. Presentation and Management of Headache in Pituitary Apoplexy. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2019, 23, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hage, R.; Eshraghi, S.R.; Oyesiku, N.M.; Ioachimescu, A.G.; Newman, N.J.; Biousse, V.; Bruce, B.B. Third, Fourth, and Sixth Cranial Nerve Palsies in Pituitary Apoplexy. World Neurosurg. 2016, 94, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavridis, I.; Meliou, M.; Pyrgelis, E.-S. Presenting Symptoms of Pituitary Apoplexy. J. Neurol. Surg. Part A Central Eur. Neurosurg. 2018, 79, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, K.N.; Huda, M.S.B.; Van De Velde, V.; Hopkins, L.; Luck, S.; Preston, R.; McGowan, B.; Carroll, P.V.; Powrie, J.K. The Prevalence and Natural History of Pituitary Hemorrhage in Prolactinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 2362–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Deng, X. Risk factors for the incidence of apoplexy in pituitary adenoma: A single-center study from southwestern China. Chin. Neurosurg. J. 2020, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, N.; Tekinel, Y.; Dagdelen, S.; Oruckaptan, H.; Soylemezoglu, F.; Erbas, T. Cavernous sinus invasion might be a risk factor for apoplexy. Pituitary 2013, 16, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, A.; Clark, A.J.; Han, S.J.; Kunwar, S.; Blevins, L.S.; Aghi, M.K. Socioeconomic factors associated with pituitary apoplexy: Clinical article. J. Neurosurg. 2013, 119, 1432–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Utz, M.; Gupta, N.; Kumar, Y.; Mangla, M.; Gupta, S.; Mangla, R. Clinical and imaging features of pituitary apoplexy and role of imaging in differentiation of clinical mimics. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2018, 8, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boellis, A.; Di Napoli, A.; Romano, A.; Bozzao, A. Pituitary apoplexy: An update on clinical and imaging features. Insights Imaging 2014, 5, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaphiades, M.S. Pituitary Ring Sign Plus Sphenoid Sinus Mucosal Thickening: Neuroimaging Signs of Pituitary Apoplexy. Neuro-Ophthalmology 2017, 41, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Baldeweg, S.; Vanderpump, M.; Drake, W.; Reddy, N.; Markey, A.; Plant, G.T.; Powell, M.; Sinha, S.; Wass, J. Society for endocrinology endocrine emergency guidance: Emergency management of pituitary apoplexy in adult patients. Endocr. Connect. 2016, 5, G12–G15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, S.C.; Dougherty, M.C.; Zanaty, M.; Bruch, L.A.; Graham, S.M.; Greenlee, J.D.W. Visual and Hormone Outcomes in Pituitary Apoplexy: Results of a Single Surgeon, Single Institution 15-Year Retrospective Review and Pooled Data Analysis. J. Neurol. Surg. Part B Skull Base 2021, 82, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, M.; Lu, Q.; Zhu, P.; Zheng, W. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for pituitary apoplexy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 370, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goshtasbi, K.; Abiri, A.; Sahyouni, R.; Mahboubi, H.; Raefsky, S.; Kuan, E.C.; Hsu, F.P.; Cadena, G. Visual and Endocrine Recovery Following Conservative and Surgical Treatment of Pituitary Apoplexy: A Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2019, 132, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahyouni, R.; Goshtasbi, K.; Choi, E.; Mahboubi, H.; Le, R.; Khahera, A.S.; Hanna, G.K.; Hatefi, D.; Hsu, F.P.; Bhandarkar, N.D.; et al. Vision Outcomes in Early versus Late Surgical Intervention of Pituitary Apoplexy: Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2019, 127, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, K.S.; Garg, M.K. High altitude-induced pituitary apoplexy. Singap. Med. J. 2012, 53, e117–e119. [Google Scholar]

- Cagnin, A.; Marcante, A.; Orvieto, E.; Manara, R. Pituitary tumor apoplexy presenting as infective meningoencephalitis. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 33, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.; Rong, T.C.; Dalan, R. Cushing’s disease presenting with pituitary apoplexy. J. Clin. Neurosci. Off. J. Neurosurg. Soc. Australas. 2012, 19, 1586–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chentli, F.; Bey, A.; Belhimer, F.; Azzoug, S. Spontaneous resolution of pituitary apoplexy in a giant boy under 10 years old. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 25, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, O.J.; Choudhry, A.J.; Nunez, E.A.; Eloy, J.A.; Couldwell, W.T.; Ciric, I.S.; Liu, J.K. Pituitary tumor apoplexy in patients with Cushing’s disease: Endocrinologic and visual outcomes after transsphenoidal surgery. Pituitary 2012, 15, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komurcu, H.F.; Ayberk, G.; Ozveren, M.F.; Anlar, O. Pituitary Adenoma Apoplexy Presenting with Bilateral Third Nerve Palsy and Bilateral Proptosis: A Case Report. Med. Princ. Pract. 2012, 21, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruljac, I.; Čerina, V.; Pećina, H.I.; Pažanin, L.; Matić, T.; Božikov, V.; Vrkljan, M. Pituitary Metastasis Presenting as Ischemic Pituitary Apoplexy Following Heparin-induced Thrombocytopenia. Endocr. Pathol. 2012, 23, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurisu, K.; Kawabori, M.; Niiya, Y.; Ohta, Y.; Mabuchi, S.; Houkin, K. Pituitary Apoplexy Manifesting as Massive Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurol. Med.-Chir. 2012, 52, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.-H.; Mao, Q. Spontaneous disappearance of the pituitary macroadenoma after apoplexy: A case report and review of the literature. Neurol. India 2012, 60, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohindra, S.; Savardekar, A.; Tripathi, M.; Garg, R. Pituitary apoplexy presenting with pure third ventricular bleed: A neurosurgical image. Neurol. India 2012, 60, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paisley, A.N.; Syed, A.A. Pituitary apoplexy masquerading as bacterial meningitis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2012, 184, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tedd, H.; Tuckett, J.; Arun, C.; Dhar, A. An unusual case of sudden onset headache due to pituitary apoplexy: A case report and review of the new UK guidelines. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2012, 42, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Singh, S.; Patil, T.B. Thalamic infarction in pituitary apolplexy syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2012, 2012, bcr2012006993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildemberg, L.E.A.; Neto, L.V.; Niemeyer, P.; Gasparetto, E.L.; Chimelli, L.; Gadelha, M.R. Association of dengue hemorrhagic fever with multiple risk factors for pituitary apoplexy. Endocr. Pract. Off. J. Am. Coll. Endocrinol. Am. Assoc. Clin. Endocrinol. 2012, 18, e97–e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Yano, S.; Kuroda, J.-I.; Hasegawa, Y.; Hide, T.; Kuratsu, J.-I. Pituitary Apoplexy Associated with Endocrine Stimulation Test: Endocrine Stimulation Test, Treatment, and Outcome. Case Rep. Endocrinol. 2012, 2012, 826901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zoli, M.; Mazzatenta, D.; Pasquini, E.; Ambrosetto, P.; Frank, G. Cavernous sinus apoplexy presenting isolated sixth cranial nerve palsy: Case report. Pituitary 2012, 15 (Suppl. 1), S37–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.-W.; Chang, H.-A.; Huang, S.-Y.; Tzeng, N.-S. Complex visual illusions in a patient with pituitary apoplexy. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2013, 35, e5–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinar, N.U.; Metin, Y.; Dagdelen, S.; Ziyal, I.; Soylemezoglu, F.; Erbas, T. Spontaneous remission of acromegaly after infarctive apoplexy with a possible relation to MRI and diabetes mellitus. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2013, 34, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Alvarado, M.; Riancho, J.; Riancho-Zarrabeitia, L.; Sedano, M.; Polo, J.; Berciano, J. Oftalmoplejía completa unilateral sin pérdida de visión como forma de presentación de una apoplejía pituitaria. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2013, 213, e67–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, R. Pituitary Apoplexy Masquerading as Acute Mountain Sickness. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2013, 24, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanous, A.A.; Quigley, E.P.; Chin, S.S.; Couldwell, W.T. Giant necrotic pituitary apoplexy. J. Clin. Neurosci. Off. J. Neurosurg. Soc. Australas. 2013, 20, 1462–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, A.S.; Rao, P.J. A 64-year-old woman with dilated right pupil, nausea, and headache. Digit. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 19, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojo, M.; Goto, M.; Miyamoto, S. Chronic expanding pituitary hematoma without rebleeding after pituitary apoplexy. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2013, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.-Y.; Lin, J.-P.; Lieu, A.-S.; Chen, Y.-T.; Chen, H.-S.; Jang, M.-Y.; Shen, J.-T.; Wu, W.-J.; Huang, S.-P.; Juan, Y.-S. Pituitary apoplexy induced by Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for treating prostate cancer-report of first Asian case. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 11, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.-J.; Hung, W.-W.; Hsiao, P.-J. A case of acromegaly complicated with diabetic ketoacidosis, pituitary apoplexy, and lymphoma. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2013, 29, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, J.; Miyashita, K.; Tamanaha, T.; Kobayashi, N.; Iihara, K.; Nagatsuka, K. Pituitary ischemic apoplexy in a young woman using oral contraceptives: A case report. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2013, 22, e643–e644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, K.; Yonezawa, T.; Shinji, Y.; Nakano, R.; Miyamae, S. Pituitary Apoplexy Caused by Hemorrhage From Pituitary Metastatic Melanoma: Case Report. Neurol. Medico-Chirurgica 2013, 53, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, S.A.; Masoodi, S.R.; Bashir, M.I.; Wani, A.I.; Farooqui, K.J.; Kanth, B.; Bhat, A.R. Dissociated hypopituitarism after spontaneous pituitary apoplexy in acromegaly. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 17 (Suppl. 1), S102–S104. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.H.; Rodrigues, J.; Bradley, M.D.; Nelson, R.J. Retroclival subdural haematoma secondary to pituitary apoplexy. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2013, 27, 845–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ní Chróinín, D.; Lambert, J. Sudden headache, third nerve palsy and visual deficit: Thinking outside the subarachnoid haemorrhage box. Age Ageing 2013, 42, 810–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Oh, K.; Kim, J.-H.; Choi, J.-W.; Kang, J.-K.; Kim, S.-H. Pituitary Apoplexy Mimicking Meningitis. Brain Tumor Res. Treat. 2013, 1, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Radhiana, H.; O Syazarina, S.; Azura, A.M.S.; Azizi, A.B. Pituitary apoplexy: A rare cause of middle cerebral artery infarction. Med. J. Malays. 2013, 68, 264–266. [Google Scholar]

- Tutanc, M.; Altas, M.; Yengil, E.; Ustun, I.; Dolapcioglu, K.S.; Balci, A.; Sefil, F.; Gokce, C. Pituitary apoplexy due to thyroxine therapy in a patient with congenital hypothyroidism. Acta Med. Indones. 2013, 45, 306–311. [Google Scholar]

- Witczak, J.K.; Davies, R.; Okosieme, O.E. An unusual case of pituitary apoplexy. QJM Mon. J. Assoc. Physicians 2013, 106, 861–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.H.; Das, K.; Javadpour, M. Pituitary apoplexy initially mistaken for bacterial meningitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013009223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, G.; Witek, P.; Koziarski, A.; Podgórski, J. Spontaneous regression of non-functioning pituitary adenoma due to pituitary apoplexy following anticoagulation treatment—A case report and review of the literature. Endokrynol. Polska 2013, 64, 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Berkenstock, M.; Szeles, A.; Ackert, J. Encephalopathy, Chiasmal Compression, Ophthalmoplegia, and Diabetes Insipidus in Pituitary Apoplexy. Neuro-Ophthalmology 2014, 38, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bujawansa, S.; Thondam, S.K.; Steele, C.; Cuthbertson, D.; Gilkes, C.E.; Noonan, C.; Bleaney, C.W.; Macfarlane, I.A.; Javadpour, M.; Daousi, C. Presentation, management and outcomes in acute pituitary apoplexy: A large single-centre experience from the United Kingdom. Clin. Endocrinol. 2014, 80, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, C.C.; Lin, C.J. Pituitary apoplexy in a teenager—Case report. Pediatr. Neurol. 2014, 50, 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, T.H.; Rheims, S.; Ritzenthaler, T.; Berthezene, Y.; Nighoghossian, N. Stroke and pituitary apoplexy revealing an internal carotid artery dissection. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2014, 23, e473–e474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Patil, S.; Raval, D.; Gopani, P. Pituitary apoplexy presenting as myocardial infarction. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 18, 232–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jho, D.H.; Biller, B.M.; Agarwalla, P.K.; Swearingen, B. Pituitary Apoplexy: Large Surgical Series with Grading System. World Neurosurg. 2014, 82, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.A.; Park, T.S.; Baek, H.S.; Jin, H.Y. Pituitary apoplexy in T3 thyrotoxicosis. Endocrine 2014, 45, 337–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltby, V.E.; Crock, P.A.; Lüdecke, D.K. A rare case of pituitary infarction leading to spontaneous tumour resolution and CSF-sella syndrome in an 11-year-old girl and a review of the pediatric literature. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 27, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, B.L.; Fu, Y.P. Pituitary apoplexy in a patient with suspected metastatic bronchogenic carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, 2014, bcr2013202803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, S.; Das, S.; Mishra, S. Dengue hemorrhagic fever: A rare cause of pituitary apoplexy. Neurol. India 2014, 62, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Bonnet, J.; Anda, J.J.M.; Balderrama-Soto, A.; Pérez-Reyes, S.P.; Pérez-Neri, I.; Portocarrero-Ortiz, L. Stroke associated with pituitary apoplexy in a giant prolactinoma: A case report. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2014, 116, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roerink, S.; Marsman, D.; Van Bon, A.; Netea-Maier, R. A Missed Diagnosis of Acromegaly During a Female-to-Male Gender Transition. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2014, 43, 1199–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.K.; Seow, C.J.; Tan, E.; Chau, Y.P.; Dalan, R. Pituitary apoplexy secondary to thrombocytopenia due to dengue hemorrhagic fever: A case report and review of the literature. Endocrine Practice: Official J. Am. Coll. Endocrinol. Am. Assoc. Clin. Endocrinol. 2014, 20, e58–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Taibo, R.; Ballesteros-Pomar, M.D.; Vidal-Casariego, A.; Alvarez-San Martín, R.M.; Kyriakos, G.; Cano-Rodríguez, I. Spontaneous remission of acromegaly: Apoplexy mimicking meningitis or meningitis as a cause of apoplexy? Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2014, 58, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Feng, F.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, R.; Xing, B. Cerebral infarction caused by pituitary apoplexy: Case report and review of literature. Turk. Neurosurg. 2014, 24, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akakın, A.; Yılmaz, B.; Ekşi, M.; Kılıç, T. A case of pituitary apoplexy following posterior lumbar fusion surgery. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2015, 23, 598–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaithambi, G. Carotid artery compression from pituitary apoplexy. QJM Int. J. Med. 2015, 108, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Banerjee, C.; Snelling, B.; Hanft, S.; Komotar, R.J. Bilateral cerebral infarction in the setting of pituitary apoplexy: A case presentation and literature review. Pituitary 2015, 18, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fountas, A.; Andrikoula, M.; Tsatsoulis, A. A 45 year old patient with headache, fever, and hyponatraemia. BMJ 2015, 350, h962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Lee, S.W.; Son, D.W.; Cha, S.H. Pituitary Apoplexy Following Mitral Valvuloplasty. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2015, 57, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, B.L.; Fu, Y.P. Pituitary apoplexy presenting with bilateral oculomotor nerve palsy. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2015212049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roerink, S.H.P.P.; Van Lindert, E.J.; Van De Ven, A.C. Spontaneous remission of acromegaly and Cushing’s disease following pituitary apoplexy: Two case reports. Neth. J. Med. 2015, 73, 242–246. [Google Scholar]

- Saberifard, J.; Yektanezhad, T.; Assadi, M. An Interesting Case of a Spontaneous Resolution of Pituitary Adenoma after Apoplexy. J. Belg. Soc. Radiol. 2015, 99, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sasagawa, Y.; Tachibana, O.; Nakagawa, A.; Koya, D.; Iizuka, H. Pituitary apoplexy following gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist administration with gonadotropin-secreting pituitary adenoma. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 22, 601–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Y.; Nakata, K.; Suzuki, K.; Ando, Y. Pituitary apoplexy presenting with anorexia and hyponatraemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2014209120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.D.; Valizadeh, N.; Meyer, F.B.; Atkinson, J.L.D.; Erickson, D.; Rabinstein, A.A. Management and outcomes of pituitary apoplexy. J. Neurosurg. 2015, 122, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, S.; Hashem, F.; Olson, S.; Ong, B.; Inder, W.J. Recurrent pituitary apoplexy due to two successive neoplasms presenting with ocular paresis and epistaxis. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case Rep. 2015, 2015, 140088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Shou, X.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Incidence of Pituitary Apoplexy and Its Risk Factors in Chinese People: A Database Study of Patients with Pituitary Adenoma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Liu, C.; Sun, B.; Chen, C.; Xiong, W.; Che, C.; Huang, H. Surgical treatment of pituitary apoplexy in association with hemispheric infarction. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 22, 1550–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, M.; Eligar, V.; DeLloyd, A.; Davies, J.S. A case of pituitary apoplexy masquerading as subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin. Case Rep. 2016, 4, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doglietto, F.; Costi, E.; Villaret, A.B.; Mardighian, D.; Fontanella, M.; Giustina, A. New oral anticoagulants and pituitary apoplexy. Pituitary 2016, 19, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambaracci, G.; Rondoni, V.; Guercini, G.; Floridi, P. Pituitary apoplexy complicated by vasospasm and bilateral cerebral infarction. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016, bcr2016216186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giammattei, L.; Mantovani, G.; Carrabba, G.; Ferrero, S.; Di Cristofori, A.; Verrua, E.; Guastella, C.; Pignataro, L.; Rampini, P.; Minichiello, M.; et al. Pituitary apoplexy: Considerations on a single center experience and review of the literature. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2016, 39, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giritharan, S.; Gnanalingham, K.; Kearney, T. Pituitary apoplexy—Bespoke patient management allows good clinical outcome. Clin. Endocrinol. 2016, 85, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, F.; Egan, A.M.; Navin, P.; Brett, F.; Dennedy, M. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist-induced pituitary apoplexy. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case Rep. 2016, 2016, 160021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ogawa, Y.; Niizuma, K.; Mugikura, S.; Tominaga, T. Ischemic pituitary adenoma apoplexy—Clinical appearance and prognosis after surgical intervention. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2016, 148, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Paschou, S.; Tzioras, K.; Trianti, V.; Lyra, S.; Lioutas, V.-A.; Seretis, A.; Vryonidou, A. Young adult patient with headache, fever and blurred vision. Hormones 2016, 15, 548–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, E.S.; Ho, A.L.; Pendharkar, A.V.; Achrol, A.S.; Harsh, G.R. Pituitary Apoplexy Associated with Carotid Compression and a Large Ischemic Penumbra. World Neurosurg. 2016, 92, 581.e7–581.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arivazhagan, A.; Rao, S.B.; Savardekar, A.; Nandeesh, B. Management dilemmas in a rare case of pituitary apoplexy in the setting of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2017, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grangeon, L.; Moscatelli, L.; Zanin, A.; Guegan-Massardier, E.; Rouille, A.; Maltete, D. Indomethacin-Responsive Paroxysmal Hemicrania in an Elderly Man: An Unusual Presentation of Pituitary Apoplexy. Headache 2017, 57, 1624–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, G.; Waqar, M.; McBain, A.; Gnanalingham, K.K. Sphenoid sinus microbiota in pituitary apoplexy: A preliminary study. Pituitary 2017, 20, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Law-Ye, B.; Pyatigorskaya, N.; Leclercq, D. Pituitary Apoplexy Mimicking Bacterial Meningitis with Intracranial Hypertension. World Neurosurg. 2017, 97, 748.e3–748.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, S.A.; Ranganthan, L.N.; Setty, V.K.; Reddy, R.; Ponnuru, D.A. Acute Ischaemic Stroke as a Manifestation of Pituitary Apoplexy in a Young Lady. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, OD03–OD05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Biswas, S.N.; Datta, J.; Chakraborty, P.P. Hypersomatotropism induced secondary polycythaemia leading to spontaneous pituitary apoplexy resulting in cure of acromegaly and remission of polycythaemia: ‘The virtuous circle’. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, 2017, bcr2017222669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek Bagir, G.; Civi, S.; Kardes, O.; Kayaselcuk, F.; Ertorer, M.E. Stubborn hiccups as a sign of massive apoplexy in a naive acromegaly patient with pituitary macroadenoma. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case Rep. 2017, 2017, 17–0044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souteiro, P.; Belo, S.; Carvalho, D. A rare case of spontaneous Cushing disease remission induced by pituitary apoplexy. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2017, 40, 555–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waqar, M.; McCreary, R.; Kearney, T.; Karabatsou, K.; Gnanalingham, K.K. Sphenoid sinus mucosal thickening in the acute phase of pituitary apoplexy. Pituitary 2017, 20, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoli, M.; Milanese, L.; Faustini-Fustini, M.; Guaraldi, F.; Asioli, S.; Zenesini, C.; Righi, A.; Frank, G.; Foschini, M.P.; Sturiale, C.; et al. Endoscopic Endonasal Surgery for Pituitary Apoplexy: Evidence On a 75-Case Series From a Tertiary Care Center. World Neurosurg. 2017, 106, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbara, A.; Clarke, S.; Eng, P.C.; Milburn, J.; Joshi, D.; Comninos, A.N.; Ramli, R.; Mehta, A.; Jones, B.; Wernig, F.; et al. Clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients presenting with pituitary apoplexy. Endocr. Connect. 2018, 7, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettag, C.; Strasilla, C.; Steinbrecher, A.; Gerlach, R. Unilateral Tuberothalamic Artery Ischemia Caused by Pituitary Apoplexy. J. Neurol. Surg. Part A Central Eur. Neurosurg. 2018, 79, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Bao, X.; Wang, R. Conservative treatment cures an elderly pituitary apoplexy patient with oculomotor paralysis and optic nerve compression: A case report and systematic review of the literature. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 1981–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, C.; Ha, G.; Jang, Y. Pituitary apoplexy following lumbar fusion surgery in prone position: A case report. Medicine 2018, 97, e0676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komshian, S.R.; Saket, R.; Bakhadirov, K. Pituitary Apoplexy With Bilateral Oculomotor Nerve Palsy. Neurohospitalist 2018, 8, NP4–NP5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzu, F.; Unal, M.; Gul, S.; Bayraktaroglu, T. Pituitary Apoplexy due to the Diagnostic Test in a Cushing’s Disease Patient. Turk. Neurosurg. 2018, 28, 323–325. [Google Scholar]

- Myla, M.; Lewis, J.; Beach, A.; Sylejmani, G.; Burge, M.R. A Perplexing Case of Pituitary Apoplexy Masquerading as Recurrent Meningitis. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2018, 6, 2324709618811370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciuti, R.; Nocchi, N.; Arnaldi, G.; Polonara, G.; Luzi, M. Pituitary adenoma apoplexy: Review of personal series. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2018, 13, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, M.J.; Kunwar, S.; Blevins, L.; Aghi, M.K. Surgical intervention for pituitary apoplexy: An analysis of functional outcomes. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 129, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, D.; Fujikawa, T. Pituitary apoplexy. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2018, 190, E1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.P.; Sanchez, M.M.; Karekezi, C.; Warsi, N.; Fernández-Gajardo, R.; Panwar, J.; Mansouri, A.; Suppiah, S.; Nassiri, F.; Nejad, R.; et al. Pituitary Apoplexy: Results of Surgical and Conservative Management Clinical Series and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2019, 130, e988–e999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisman, C.; Ward, M.; Majmundar, N.; Damodara, N.; Hsueh, W.D.; Eloy, J.A.; Liu, J.K. Pituitary Apoplexy Following Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. World Neurosurg. 2019, 121, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupont, G.; Lachkar, S.; Iwanaga, J.; Tubbs, R.S.; Ishak, B. Sudden Headache and Blindness Due to Pituitary (Adenoma) Infarction: A Case Report. Cureus 2019, 11, e4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghalaenovi, H.; Azar, M.; Fattahi, A. Spontaneous regression of nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harju, T.; Alanko, J.; Numminen, J. Pituitary apoplexy following endoscopic nasal surgery: A case report. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2019, 7, 2050313X19855867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmann, A.; Micko, A.; Frischer, J.M.; Roetzer, T.; Vila, G.; Wolfsberger, S.; Knosp, E. Multiple Pituitary Apoplexy—Cavernous Sinus Invasion as Major Risk Factor for Recurrent Hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 2019, 126, e723–e730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirigin Biloš, L.S.; Kruljac, I.; Radošević, J.M.; Ćaćić, M.; Škoro, I.; Čerina, V.; Pećina, I.H.; Vrkljan, M. Empty Sella in the Making. World Neurosurg. 2019, 128, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, R.G.; Chang, A.Y.; Raghunathan, A.; Van Gompel, J.J. Apoplectic Silent Crooke Cell Adenoma with Adjacent Pseudoaneurysms: Causation or Bystander? World Neurosurg. 2019, 122, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Mishra, S.; Yadav, K.; Rajput, R. Uncontrolled diabetes as a rare presenting cause of pituitary apoplexy. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e228161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naito, Y.; Mori, J.; Tazoe, J.; Tomida, A.; Yagyu, S.; Nakajima, H.; Iehara, T.; Tatsuzawa, K.; Mukai, T.; Hosoi, H. Pituitary apoplexy after cardiac surgery in a 14-year-old girl with Carney complex: A case report. Endocr. J. 2019, 66, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nioi, M.; Napoli, P.E.; Ferreli, F. Fatal Iatrogenic Pituitary Apoplexy after Surgery for Neuroophthalmological Disorder. Anesthesiology 2019, 130, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, B.; Patrícia, T.; Aldomiro, F. Pituitary Apoplexy May Be Mistaken for Temporal Arteritis. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2019, 6, 001261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.R.M.; Bello, C.T.; Sousa, A.; Duarte, J.S.; Campos, L.B. Pituitary Apoplexy Following Systemic Anticoagulation. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2019, 6, 001254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Sapera, E.; Sarria-Estrada, S.; Arikan, F.; Biagetti, B. Acromegaly remission, SIADH and pituitary function recovery after macroadenoma apoplexy. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case Rep. 2019, 2019, 19–0057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Gohlke, P.R.; Chapman, P.R. Spontaneous “pneumo-apoplexy” as a presentation of pituitary adenoma. Clin. Imaging 2019, 58, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaid, B.; Kalaba, F.; Bachuwa, G.; Sullivan, S.E. Heparin-Induced Pituitary Apoplexy Presenting as Isolated Unilateral Oculomotor Nerve Palsy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep. Endocrinol. 2019, 2019, 5043925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Robert, A.; Rajole, P.; Robert, P. A Rare Case of Pituitary Apoplexy Secondary to Dengue Fever-induced Thrombocytopenia. Cureus 2019, 11, e5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uneda, A.; Hirashita, K.; Yunoki, M.; Yoshino, K.; Date, I. Pituitary adenoma apoplexy associated with vardenafil intake. Acta Neurochir. 2019, 161, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, L.; Wang, W.; Guo, X.; Feng, C.; Lian, W.; Li, Y.; Xing, B. Coagulative necrotic pituitary adenoma apoplexy: A retrospective study of 21 cases from a large pituitary center in China. Pituitary 2019, 22, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waqar, M.; Karabatsou, K.; Kearney, T.; Roncaroli, F.; Gnanalingham, K.K. Classical pituitary apoplexy. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2019, 80, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.V.; Post, K.D.; Cheesman, K.C. Recurrent Pituitary Apoplexy In An Adenoma With Switching Phenotypes. AACE Clin. Case Rep. 2020, 6, e221–e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]