Folate-Receptor-Targeted Gold Nanoparticles Bearing a DNA-Binding Anthraquinone

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

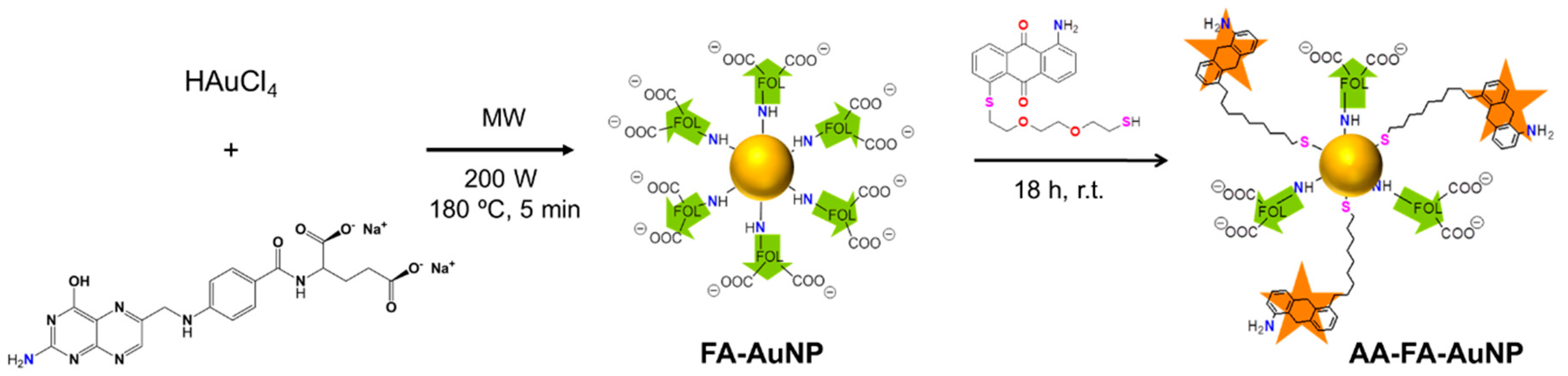

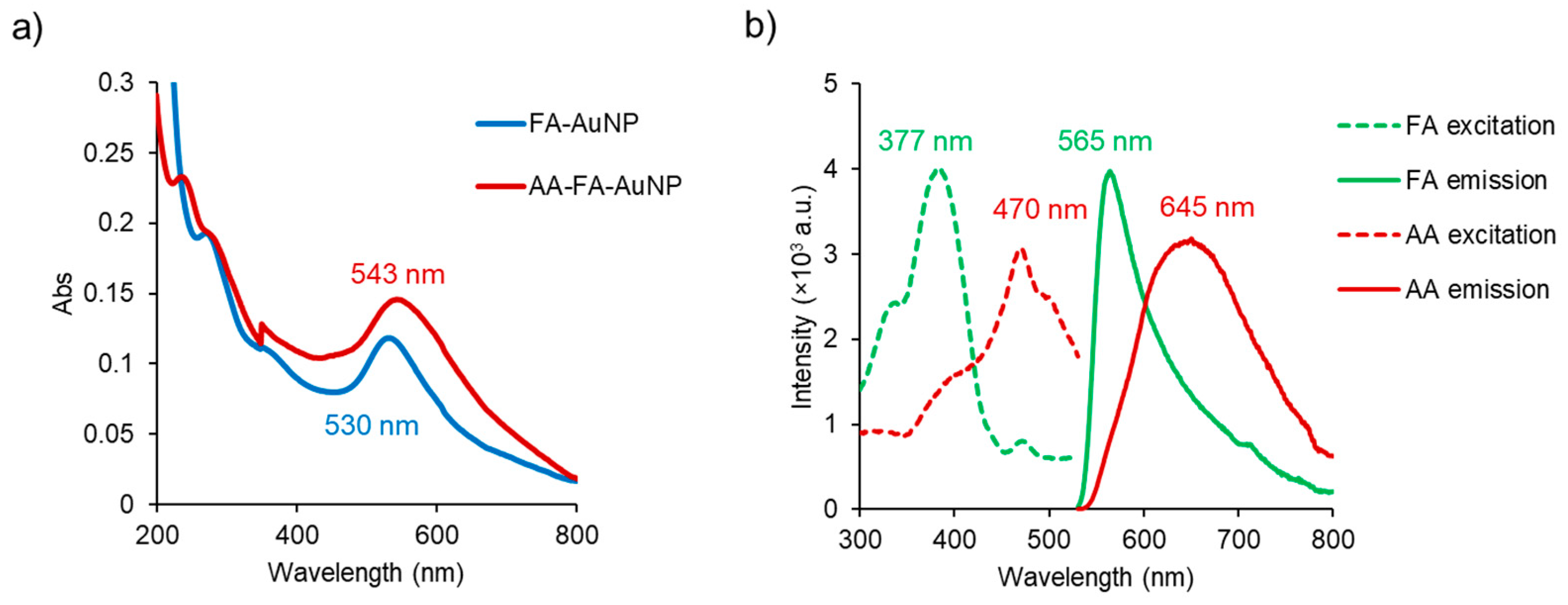

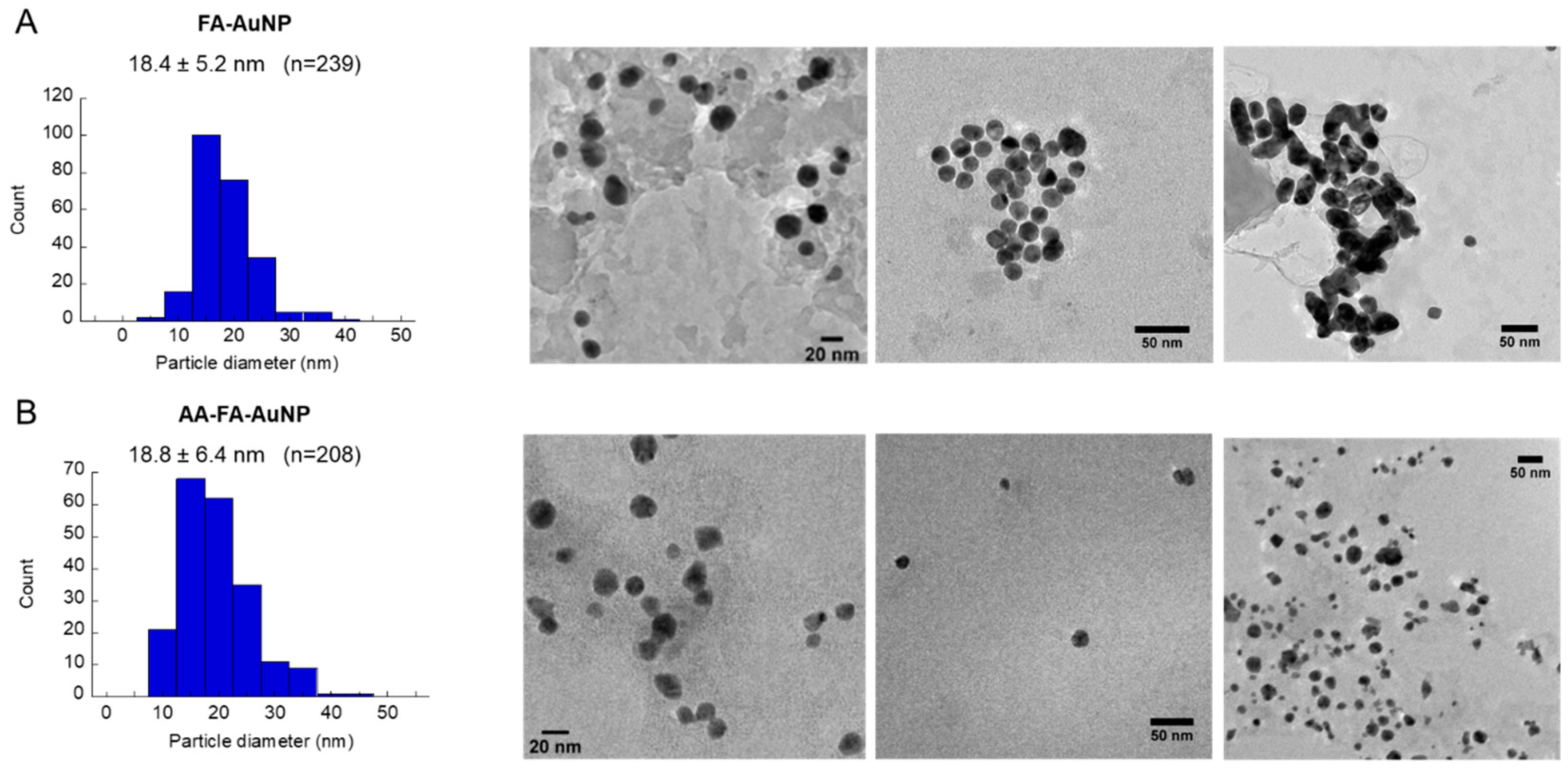

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization

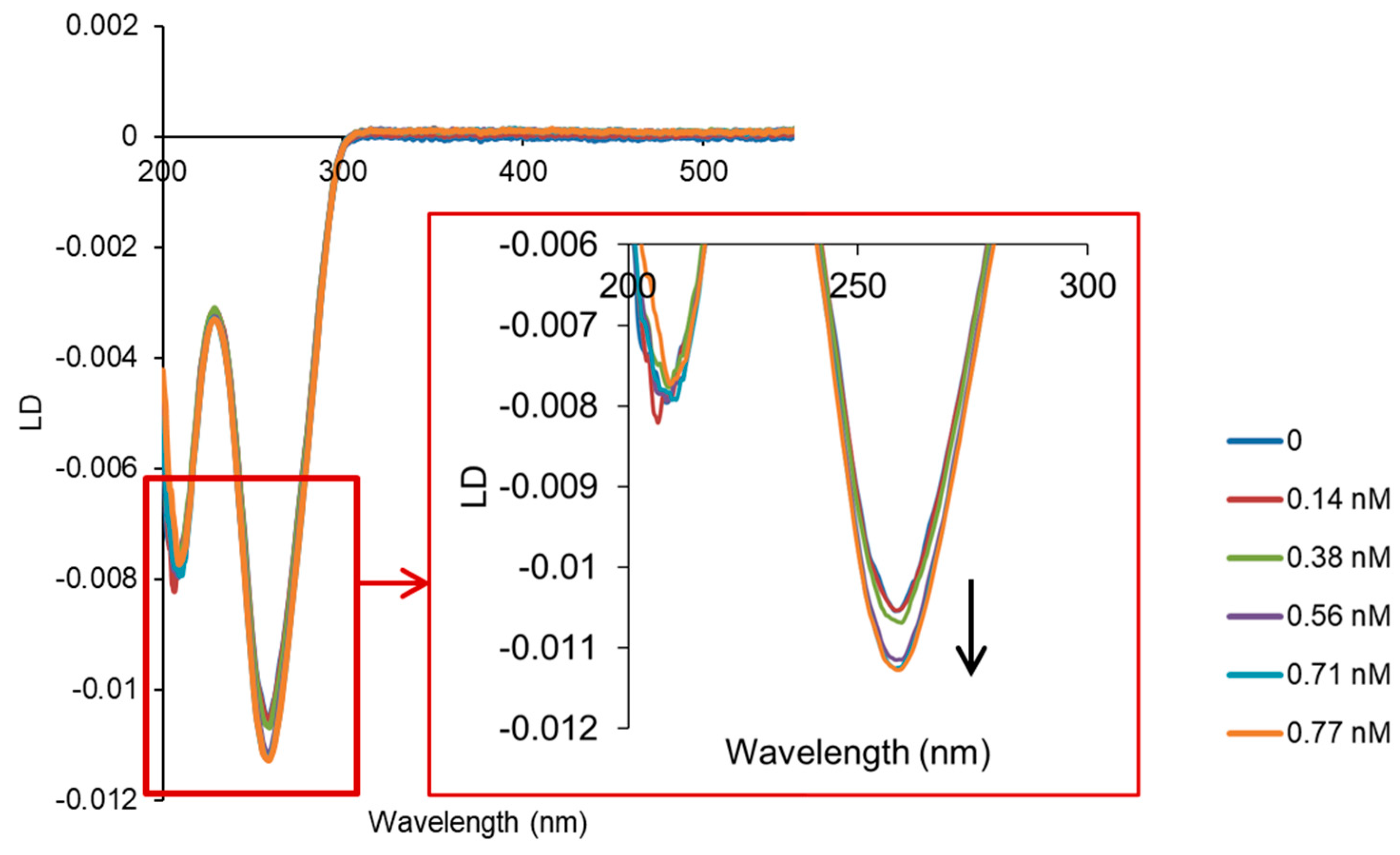

2.2. Interaction with ct-DNA

2.3. In Vitro Cytotoxicity

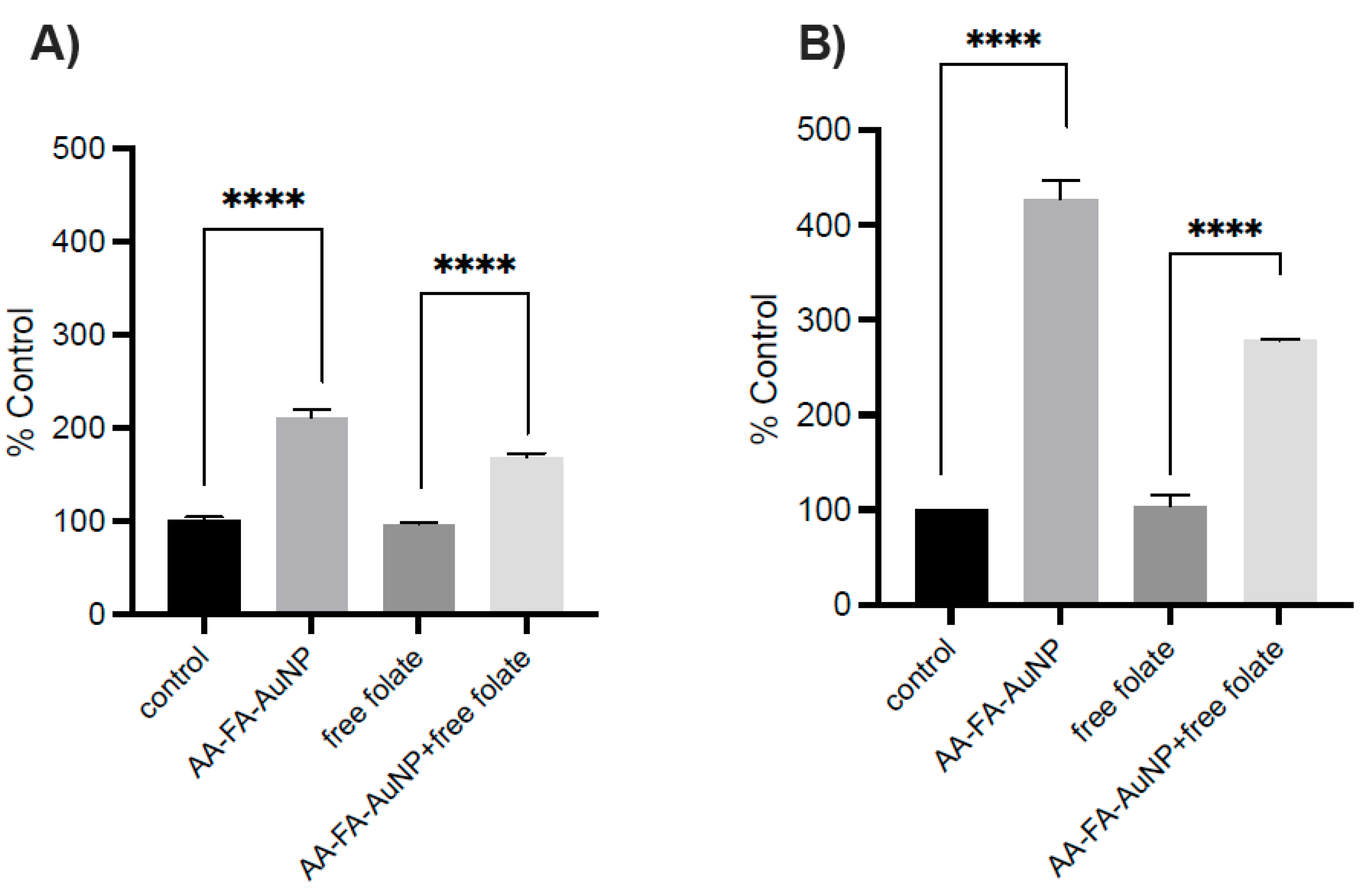

2.4. Cellular Uptake

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis

3.1.1. 1-Amine-5-(4,7-dioxa-1,10-dithiadecyl)anthracene-9,10-dione (AA)

3.1.2. FA-AuNP

3.1.3. AA-FA-AuNP

3.2. DNA Binding Studies

3.3. Cell Culture

3.3.1. Flow Cytometry

3.3.2. Cell Viability (Release of Adenylate Kinase)

3.3.3. MTT Cell Proliferation Assay

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, A.; Ezati, P.; Rhim, J.W. Alizarin: Prospects and sustainability for food safety and quality monitoring applications. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 223, 113169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, E.M.; Muller, C.E. Anthraquinones As Pharmacological Tools and Drugs. Med. Res. Rev. 2016, 36, 705–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.; Mao, J.; Chen, Q. Redox flow batteries toward more soluble anthraquinone derivatives. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2021, 29, 100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qun, T.; Zhou, T.; Hao, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, K.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, W. Antibacterial activities of anthraquinones: Structure-activity relationships and action mechanisms. RSC Med. Chem. 2023, 14, 1446–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, R.W.; Cornell, K.A.; Johnson, L.L.; Ignatushchenko, M.; Hinrichs, D.J.; Riscoe, M.K. Potentiation of the antimalarial agent rufigallol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 1408–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, O.P.S.; Beteck, R.M.; Legoabe, L.J. Antimalarial application of quinones: A recent update. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 210, 113084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, R.J.; Ngoc, T.M.; Bae, K.; Cho, H.J.; Kim, D.D.; Chun, J.; Khan, S.; Kim, Y.S. Anti-inflammatory properties of anthraquinones and their relationship with the regulation of P-glycoprotein function and expression. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 48, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vilas, J.A.; Pino-Angeles, A.; Martinez-Poveda, B.; Quesada, A.R.; Medina, M.A. The noni anthraquinone damnacanthal is a multi-kinase inhibitor with potent anti-angiogenic effects. Cancer Lett. 2017, 385, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugas, M.L.; Calvo, G.; Marioni, J.; Cespedes, M.; Martinez, F.; Vanzulli, S.; Saenz, D.; Di Venosa, G.; Nunez Montoya, S.; Casas, A. Photosensitization of a subcutaneous tumour by the natural anthraquinone parietin and blue light. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Lu, G.; Shen, H.M.; Chung, M.C.; Ong, C.N. Anti-cancer properties of anthraquinones from rhubarb. Med. Res. Rev. 2007, 27, 609–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, N.S.; Zhang, J.Z.; Whan, R.M.; Yamamoto, N.; Hambley, T.W. Accumulation of an anthraquinone and its platinum complexes in cancer cell spheroids: The effect of charge on drug distribution in solid tumour models. Chem. Commun. 2009, 2673–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campora, M.; Canale, C.; Gatta, E.; Tasso, B.; Laurini, E.; Relini, A.; Pricl, S.; Catto, M.; Tonelli, M. Multitarget Biological Profiling of New Naphthoquinone and Anthraquinone-Based Derivatives for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiala, J.; Roach, T.; Holzinger, A.; Husiev, Y.; Delueg, L.; Hammerle, F.; Armengol, E.S.; Schobel, H.; Bonnet, S.; Laffleur, F.; et al. The Light-activated Effect of Natural Anthraquinone Parietin against Candida auris and Other Fungal Priority Pathogens. Planta Medica 2024, 90, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, M.S.; Alsantali, R.I.; Jassas, R.S.; Alsimaree, A.A.; Syed, R.; Alsharif, M.A.; Kalpana, K.; Morad, M.; Althagafi, I.I.; Ahmed, S.A. Journey of anthraquinones as anticancer agents—A systematic review of recent literature. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 35806–35827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Chen, Q.; Pi, R.; Chen, J. A research update on the therapeutic potential of rhein and its derivatives. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 899, 173908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevitha, D.; Amarnath, K. Chitosan/PLA nanoparticles as a novel carrier for the delivery of anthraquinone: Synthesis, characterization and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 101, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angheluta, A.; Bacaita, E.; Raduv, V.; Agop, M.; Ignat, L.; Uritu, C.; Maier, S.; Pinteala, M. Mathematical modelling of the release profile of anthraquinone-derived drugs encapsulated on magnetite nanoparticles. Rev. Roum. De Chim. 2013, 58, 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Dreaden, E.C.; Alkilany, A.M.; Huang, X.; Murphy, C.J.; El-Sayed, M.A. The golden age: Gold nanoparticles for biomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2740–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, A.B.; Cardo, L.; Claire, S.; Craig, J.S.; Hodges, N.J.; Vladyka, A.; Albrecht, T.; Rochford, L.A.; Pikramenou, Z.; Hannon, M.J. Assisted delivery of anti-tumour platinum drugs using DNA-coiling gold nanoparticles bearing lumophores and intercalators: Towards a new generation of multimodal nanocarriers with enhanced action. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 9244–9256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.M.; Claire, S.; Teixeira, R.I.; Dosumu, A.N.; Carrod, A.J.; Dehghani, H.; Hannon, M.J.; Ward, A.D.; Bicknell, R.; Botchway, S.W.; et al. Iridium Nanoparticles for Multichannel Luminescence Lifetime Imaging, Mapping Localization in Live Cancer Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 10242–10249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosumu, A.N.; Claire, S.; Watson, L.S.; Girio, P.M.; Osborne, S.A.M.; Pikramenou, Z.; Hodges, N.J. Quantification by Luminescence Tracking of Red Emissive Gold Nanoparticles in Cells. JACS Au 2021, 1, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, S.W.; Liaw, J.W.; Hsu, F.Y.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lyu, M.J.; Yeh, M.H. Surface-Modified Gold Nanoparticles with Folic Acid as Optical Probes for Cellular Imaging. Sensors 2008, 8, 6660–6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosyidah, A.l.; Kerdtoob, S.; Yudhistyra, W.I.; Munfadlila, A.W. Gold nanoparticle-based drug nanocarriers as a targeted drug delivery system platform for cancer therapeutics: A systematic review. Gold Bull. 2023, 56, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krpetic, Z.; Scari, G.; Caneva, E.; Speranza, G.; Porta, F. Gold nanoparticles prepared using cape aloe active components. Langmuir 2009, 25, 7217–7221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.; Javaid, F.; Chudasama, V. Advances in targeting the folate receptor in the treatment/imaging of cancers. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 790–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaranti, M.; Cojocaru, E.; Banerjee, S.; Banerji, U. Exploiting the folate receptor alpha in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Arivarasan, V.K. A multifunctional drug delivery cargo: Folate-driven gold nanoparticle-vitamin B complex for next-generation drug delivery. Mater. Lett. 2024, 355, 135425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhai, J.; Wang, E. One-step synthesis of folic acid protected gold nanoparticles and their receptor-mediated intracellular uptake. Chemistry 2009, 15, 9868–9873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Florez, V.; Mendez-Sanchez, S.C.; Patron-Soberano, O.A.; Rodriguez-Gonzalez, V.; Blach, D.; Martinez, O.F. Gold nanoparticle-mediated generation of reactive oxygen species during plasmonic photothermal therapy: A comparative study for different particle sizes, shapes, and surface conjugations. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 2862–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.; Bertel, L.; Páez-Mozo, E.; Martínez, F. Photochemical Synthesis of the Bioconjugate Folic Acid-Gold Nanoparticles. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. 2013, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Yang, L.; Du, G.; Pai-Panandiker, A.S.; Huang, X.; Yan, B. Enhancement of cell recognition in vitro by dual-ligand cancer targeting gold nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 2540–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Jia, J.; Lai, Y.; Ma, Y.; Weng, J.; Sun, L. Conjugating folic acid to gold nanoparticles through glutathione for targeting and detecting cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 5528–5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansoori, G.A.; Brandenburg, K.S.; Shakeri-Zadeh, A. A comparative study of two folate-conjugated gold nanoparticles for cancer nanotechnology applications. Cancers 2010, 2, 1911–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, O.; Sengelen, A.; Emik, S.; Onay-Ucar, E.; Arda, N.; Gurdag, G. Folic acid-modified methotrexate-conjugated gold nanoparticles as nano-sized trojans for drug delivery to folate receptor-positive cancer cells. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 355101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniele, R.; Brazzale, C.; Arpac, B.; Tognetti, F.; Pesce, C.; Malfanti, A.; Sayers, E.; Mastrotto, F.; Jones, A.T.; Salmaso, S.; et al. Influence of Folate-Targeted Gold Nanoparticles on Subcellular Localization and Distribution into Lysosomes. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshgard, K.; Hashemi, B.; Arbabi, A.; Rasaee, M.J.; Soleimani, M. Radiosensitization effect of folate-conjugated gold nanoparticles on HeLa cancer cells under orthovoltage superficial radiotherapy techniques. Phys. Med. Biol. 2014, 59, 2249–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beik, J.; Jafariyan, M.; Montazerabadi, A.; Ghadimi-Daresajini, A.; Tarighi, P.; Mahmoudabadi, A.; Ghaznavi, H.; Shakeri-Zadeh, A. The benefits of folic acid-modified gold nanoparticles in CT-based molecular imaging: Radiation dose reduction and image contrast enhancement. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 1993–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlen, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallstrom, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, A.; Kampf, C.; Sjostedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Jia, J.; Ma, Y.; Weng, J.; Sun, Y.; Sun, L. Microwave-assisted one-step rapid synthesis of folic acid modified gold nanoparticles for cancer cell targeting and detection. MedChemComm 2011, 2, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudalige, T.; Qu, H.; Van Haute, D.; Ansar, S.M.; Paredes, A.; Ingle, T. Chapter 11—Characterization of Nanomaterials: Tools and Challenges. In Nanomaterials for Food Applications; López Rubio, A., Fabra Rovira, M.J., Martínez Sanz, M., Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 313–353. [Google Scholar]

- Hwa Kim, S.; Hoon Jeong, J.; Chul Cho, K.; Wan Kim, S.; Gwan Park, T. Target-specific gene silencing by siRNA plasmid DNA complexed with folate-modified poly(ethylenimine). J. Control Release 2005, 104, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, A.V.; Xie, J.; Zhu, Q.; Shen, Z.; Su, W.; Kuai, L.; Soll, R.; Rader, C.; Shaver, G.; Douthit, L.; et al. Control of the antitumour activity and specificity of CAR T cells via organic adapters covalently tethering the CAR to tumour cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 8, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, D.; Kratz, F.; Wang, S.W. Engineered drug-protein nanoparticle complexes for folate receptor targeting. Biochem. Eng. J. 2014, 89, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Oza, G.; Mewada, A.; Shah, R.; Thakur, M.; Sharon, M. Folic acid mediated synaphic delivery of doxorubicin using biogenic gold nanoparticles anchored to biological linkers. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinothini, K.; Dhilip Kumar, S.S.; Abrahamse, H.; Rajan, M. Enhanced Doxorubicin Delivery in Folate-Overexpressed Breast Cancer Cells Using Mesoporous Carbon Nanospheres. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 34532–34545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.S.; Arribada, R.G.; Silva, J.O.; Silva-Cunha, A.; Townsend, D.M.; Ferreira, L.A.M.; Barros, A.L.B. In Vitro and In Vivo Effect of pH-Sensitive PLGA-TPGS-Based Hybrid Nanoparticles Loaded with Doxorubicin for Breast Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, L.; Cui, S.; Mahounga, D.; Zhang, J.; Gu, Y. Folate conjugated CdHgTe quantum dots with high targeting affinity and sensitivity for in vivo early tumor diagnosis. J. Fluoresc. 2011, 21, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caballero, A.B.; Hodges, N.J.; Hannon, M.J. Folate-Receptor-Targeted Gold Nanoparticles Bearing a DNA-Binding Anthraquinone. Inorganics 2025, 13, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13030087

Caballero AB, Hodges NJ, Hannon MJ. Folate-Receptor-Targeted Gold Nanoparticles Bearing a DNA-Binding Anthraquinone. Inorganics. 2025; 13(3):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13030087

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaballero, Ana B., Nikolas J. Hodges, and Michael J. Hannon. 2025. "Folate-Receptor-Targeted Gold Nanoparticles Bearing a DNA-Binding Anthraquinone" Inorganics 13, no. 3: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13030087

APA StyleCaballero, A. B., Hodges, N. J., & Hannon, M. J. (2025). Folate-Receptor-Targeted Gold Nanoparticles Bearing a DNA-Binding Anthraquinone. Inorganics, 13(3), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13030087