Development of a Rapid and Non-Destructive Method for the Detection of Water Addition in Octopus Species (Octopus vulgaris and Eledone cirrhosa) Using Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

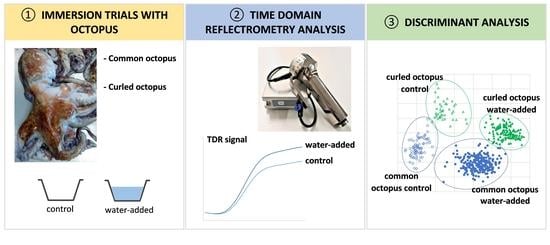

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials, Processing, and Sampling

2.2. Weight Changes, Cooking Loss, Moisture and Protein Contents

2.3. Electrical Conductivity

2.4. Time Domain Reflectometry—RFQ-Scan® Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Control Octopus Samples

3.2. Evaluation of Water Addition in Octopus Samples

3.3. Cooking Losses of Octopus Samples

3.4. Data Exploration of TDR Results

3.4.1. TDR Results of O. vulgaris and E. cirrhosa

3.4.2. Multivariate Analysis of TDR Results

3.5. Calibration and Validation of TDR Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Ruth, S.M.; Brouwer, E.; Koot, A.; Wijtten, M. Seafood and Water Management. Foods 2014, 3, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mariani, S.; Griffiths, A.M.; Velasco, A.; Kappel, K.; Jérôme, M.I.; Perez-Martin, R.; Schröder, U.; Verrez-Bagnis, V.; Silva, H.; Vandamme, S.G.; et al. Low mislabeling rates indicate marked improvements in European seafood market operations. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2015, 13, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, M.Á.; Jiménez, E.; Pérez-Villarreal, B. Misdescription incidents in seafood sector. Food Control. 2016, 62, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, E.H. Seafood Marketing: Combating Fraud and Deception. In Congressional Research Service, 7-5700; RL34124; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, R.; Teixeira, B.; Gonçalves, S.; Lourenço, H.; Martins, F.; Camacho, C.; Oliveira, R.; Silva, H. The quality of deep-frozen octopus in the Portuguese retail market: Results from a case study of abusive water addition practices. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 77, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmyard, N. Seafood Fraud—A Difficult Nut to Crack. 2017. Available online: https://www.seafoodsource.com/features/seafood-fraud-a-difficult-nut-to-crack (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. Off. J. Eur. Union 2011, L 304, 18–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pita, C.; Roumbedakis, K.; Fonseca, T.; Matos, F.L.; Pereira, J.; Villasante, S.; Pita, P.; Bellido, J.M.; Gonzalez, A.F.; García-Tasende, M.; et al. Fisheries for common octopus in Europe: Socioeconomic importance and management. Fish. Res. 2021, 235, 105820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICES. Interim Report of the Working Group on Cephalopod Fisheries and Life History (WGCEPH). In ICES Expert Group Reports (Until 2018). Report; ICES CM 2017/SSGEPD:12; ICES: Funchal, Portugal, 2018; p. 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, N. Bait & switch: The fraud crisis in the seafood industry. Atlantic 2015. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/03/bait-and-switch/388126/ (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Mariani, S.; Ellis, J.; O’Reilly, A.; Bréchon, A.L.; Sacchi, C.; Miller, D.D. Mass Media Influence and the Regulation of Illegal Practices in the Seafood Market. Conserv. Lett. 2014, 7, 478–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, D.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.J.; Lee, S.H. Detection of Artificially Water-Injected Frozen Octopus minor (Sasaki) Using Dielectric Properties. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 8968351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- JST. Polvo Congelado: Mais Água Que Molusco. Translated “Frozen Octopus: More Water than Mollusk”; JST: Hong Kong, China, 2019; Available online: https://jornalsabores.com/polvo-congelado-agua-molusco-2/ (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Breck, J.E. Body composition in fishes: Body size matters. Aquaculture 2014, 433, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeannes, M.I.; Almandos, M.E. Estimation of fish proximate composition starting from water content. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2003, 16, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.; Schimmer, O.; Vieira, H.; Pereira, J.; Teixeira, B. Control of abusive water addition to Octopus vulgaris with non-destructive methods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettinati, J.D.; Swift, C.E.; Cohen, E.H. Moisture and Fat Analysis of Meat and Meat Products: A Review and Comparison of Methods. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 2020, 56, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmas, E. Techniques for measurement of moisture content of foods. Food Technol. 1982, 34, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.W.; Bell, L.N. Determination of Moisture and Ash Contents of Foods. In Handbook of Food Analysis: Physical Characterization and Nutrient Analysis; Nollet, L.M.L., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 55–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, M.; Knöchel, R.; Daschner, F.; Berger, U.K. Composition of foods using microwave dielectric spectra. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2000, 210, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, M.S.; Raghavan, G.S.V. An Overview of Microwave Processing and Dielectric Properties of Agri-food Materials. Biosyst. Eng. 2004, 88, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakey, R.T.; Morales-Partera, A.M. Microwave dielectric spectroscopy—A versatile methodology for online, non-destructive food analysis, monitoring and process control. Eng. Agric. Environ. Food 2016, 9, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Ortega, S.; Melado-Herreros, Á.; Foti, G.; Olabarrieta, I.; Ramilo-Fernández, G.; Gonzalez Sotelo, C.; Teixeira, B.; Velasco, A.; Mendes, R. Rapid Differentiation of Unfrozen and Frozen-Thawed Tuna with Non-Destructive Methods and Classification Models: Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA), Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIR) and Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR). Foods 2021, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, M.; Daschner, F. Time Domain Spectroscopy. In Fishery Products: Quality, Safety and Authenticity; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2009; pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, S.N.; Narsaiah, K.; Basediya, A.L.; Sharma, R.; Jaiswal, P.; Kumar, R.; Bhardwaj, R. Measurement techniques and application of electrical properties for nondestructive quality evaluation of foods—A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teixeira, B.; Vieira, H.; Martins, S.; Mendes, R. Quantitation of Water Addition in Octopus Using Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR): Development of a Rapid and Non-Destructive Food Analysis Method. Foods 2022, 11, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.; Vieira, H.; Pereira, J.; Teixeira, B. Water uptake and cooking losses in Octopus vulgaris during industrial and domestic processing. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 78, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Communities International, 18th ed.; AOAC: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Denis, T.; Goupy, J. Optimization of a nitrogen analyser based on the Dumas method. Anal. Chim. Acta 2004, 515, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmer, O.; Knöchel, R. A hand-held TDR-system with a fast system-rise time and a high resolution bandwidth for moisture measurements in the microwave frequency range. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Electromagnetic Wave Interaction with Water and Moist Substances, Rotorua, New Zealand, 23–26 March 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmer, O.; Osen, R.; Schönfeld, K.; Hemmy, B. Detection of added Water in Seafood using a Dielectric Time Domain Reflectometer. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Electromagnetic Wave Interaction with Water and Moist Substances—ISEMA 2009, Espoo, Finland, 1 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Özalp, B.T.; Karakaya, M. Determination of some functional and technological properties of octopus (Octopus vulgaris C.), calamary (Illex coindetti V.), mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis L.) and cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis L.) meats. J. Fish. Sci. 2009, 3, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R.; Nunes, M.; Reis, C. Seasonal changes in the biochemical composition of Octopus vulgaris Cuvier, 1797, from three areas of the Portuguese coast. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2002, 71, 739–751. [Google Scholar]

- Estefanell, J.; Socorro, J.; Tuya, F.; Izquierdo, M.; Roo, J. Growth, protein retention and biochemical composition in Octopus vulgaris fed on different diets based on crustaceans and aquaculture by-products. Aquaculture 2011, 322–323, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato, E.; Portacci, G.; Biandolino, F. Effect of diet on growth performance, feed efficiency and nutritional composition of Octopus vulgaris. Aquaculture 2010, 309, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitz, J.; Mourocq, E.; Schoen, V.; Ridoux, V. Proximate composition and energy content of forage species from the Bay of Biscay: High- or low-quality food? ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2010, 67, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Moral, A.; Morales, J.; Montero, P. Characterization and Functionality of Frozen Muscle Protein in Volador (Illex coindetii), Pota (Todaropsis eblanae), and Octopus (Eledone cirrhosa). J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 2164–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leonardo, A.I.T.F.A. Study of Quality of the Commons Octopus (O. vulgaris) Captured in the Bay of Cascais (Estudo da Qualidade do Polvo-Comum (O. vulgaris) Capturado na Baía de Cascais). Master’s Thesis, Technical University of Lisbon, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Lisbon, Portugal, 2010. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10400.5/2185 (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Ozogul, Y.; Duysak, O.; Ozogul, F.; Özkütük, A.S.; Türeli, C. Seasonal effects in the nutritional quality of the body structural tissue of cephalopods. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrinha, A.; Cruz, R.; Gomes, F.; Mendes, E.; Casal, S.; Morais, S. Octopus lipid and vitamin E composition: Interspecies, interorigin, and nutritional variability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 8508–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Gomes, F.; Torrinha, Á.; Ramalhosa, M.J.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Morais, S. Commercial octopus species from different geographical origins: Levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and potential health risks for consumers. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 121, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zlatanos, S.; Laskaridis, K.; Feist, C.; Sagredos, A. Proximate composition, fatty acid analysis and protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score of three Mediterranean cephalopods. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2006, 50, 967–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botta, J.R.; Cahill, F.M. Moisture content of scallop meat: Effect of species, time of season and method of determining “added water”. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference Tropical and Subtropical Fisheries Technological Conference of the Americas, Williamsburg, VA, USA, 4–6 November 1993. [Google Scholar]

- SEAFISH. Review of Polyphosphates as Additives and Testing Methods for Them in Scallops and Prawns; Campden BRI Report: BC-REP-125846-01; SEAFISH.ORG: 2012. Available online: www.seafish.org (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Kugino, M.; Kugino, K. Microstructural and Rheological Properties of Cooked Squid Mantle. J. Food Sci. 1994, 59, 792–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.; Muniz, J.A.; Bandarra, N.M.; Castanheira, I.; Coelho, I.R.; Delgado, I.; Gonçalves, S.; Lourenço, H.M.; Motta, C.; Duarte, M.P.; et al. Effects of Industrial Boiling on the Nutritional Profile of Common Octopus (Octopus vulgaris). Foods 2019, 8, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, Z.; Dubova, H.; Mo, H. Effects of sous vide cooking on physicochemical properties of squid. J. Hyg. Eng. Des. 2019, 29, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gokoglu, N.; Topuz, O.K.; Yerlikaya, P.; Yatmaz, H.A.; Ucak, I. Effects of Freezing and Frozen Storage on Protein Functionality and Texture of Some Cephalopod Muscles. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2018, 27, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokoglu, N.; Topuz, O.K.; Gokoglu, M.; Tokay, F.G. Characterization of protein functionality and texture of tumbled squid, octopus and cuttlefish muscles. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11, 1699–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulladosa, E.; Duran-Montgé, P.; Serra, X.; Picouet, P.; Schimmer, O.; Gou, P. Estimation of dry-cured ham composition using dielectric time domain reflectometry. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, M.; Knöchel, R.; Daschner, F.; Berger, U.-K. Composition of foods including added water using microwave dielectric spectra. Food Control. 2001, 12, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, M.; Anderson, D. Dielectric studies of added water in poultry meat and scallops. J. Food Eng. 1996, 28, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, M.S.; Trabelsi, S.; Tollner, E.W.; Nelson, S.O. Dielectric spectroscopy measurements for moisture prediction in Vidalia onions. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, F.; Jiao, Y. Prediction of salmon (Salmo salar) quality during refrigeration storage based on dielectric properties. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Xie, J. Quality of Cuttlefish as Affected by Different Thawing Methods. Int. J. Food Prop. 2022, 25, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, J.L.; Montero, P.; Borderías, J.; An, H. Properties of Proteolytic Enzymes from Muscle of Octopus (Octopus vulgaris) and Effects of High Hydrostatic Pressure. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 2555–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinacci, L.; Armani, A.; Scardino, G.; Guidi, A.; Nucera, D.; Miragliotta, V.; Abramo, F. Selection of Histological Parameters for the Development of an Analytical Method for Discriminating Fresh and Frozen/Thawed Common Octopus (Octopus vulgaris) and Preventing Frauds along the Seafood Chain. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 13, 2111–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Octopus Species | Moisture (g/100 g) | Protein (g/100 g) | M/P Ratio | Origin and Other Details | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octopus vulgaris | 80.7 ± 1.6 (76.2–85.4) | 16.6 ± 1.5 (12.0–19.1) | 3.9–6.9 4.9 ± 0.6 | Portuguese coast; fresh non-processed samples | Mendes et al. [27] |

| Octopus vulgaris | Viana do Castelo: 78.2–81.4 Cascais: 78.0–80.2 Tavira: 76.5–80.5 | Viana do Castelo: 16.1–18.4 Cascais: 17.0–18.3 Tavira: 17.1–19.8 | Portuguese coast; n = 195 | Rosa et al. [33] | |

| Octopus vulgaris | 12.7–17.5 | Cascais, Portugal | Leonardo [38] | ||

| Octopus vulgaris | 81.10 ± 0.68 | 12.80 ± 0.38 | 6.3 * | Aydın, Turkey; n = 6 | Özalp and Karakaya [32] |

| Octopus vulgaris | S: 83.41 ± 0.08 A: 82.53 ± 0.13 W: 80.71 ± 1.18 | S: 14.83 ± 0.67 A: 14.78 ± 1.0 W: 15.28 ± 0.21 | S: 5.6 * A: 5.6 * W: 5.3 * | Eastern Mediterranean sea; n ≥ 3 | Ozogul et al. [39] |

| Octopus vulgaris | NEA: 88.7 ± 3.6 (84.5–92.4) NWA: 81.5 ± 1.0 (80.7–82.8) ECA: 91.7 ± 4.1 (88.4–97.4) WCA: 85.9 ± 0.6 (85.6–86.7) PO: 89.2 ± 0.6 (88.5–89.9) MS: 91.0 ± 2.8 (88.5–94.3) | Markets from the NW region of Portugal; NEA, NWA, ECA, and WCA, PO: n = 8 MS: n = 5 | Torrinha et al. [40] | ||

| Octopus vulgaris | NEA: 87.5 (82.8–92.4) NWA: 81.5 (78.0–83.9) ECA: 90.2 (83.8–97.4) WCA: 87.4 (85.6–90.7) PO: 89.8 (88.5–93.1) MS: 90.6 (88.5–94.3) | Markets from the NW region of Portugal; n = 144 | Oliveira et al. [41] | ||

| Octopus vulgaris | 80.4 ± 1.5 | 15.8 ± 3.4 | 5.1 * | Fish market in Thessaloniki, Greece | Zlatanos et al. [42] |

| Octopus vulgaris | 83.6 ± 2.2 | 77.8 ± 3.2 DW | Wild octopus captured in Canary Islands, Spain | Estefanell et al. [34] | |

| Octopus vulgaris | WC: 85.2 ± 0.6 BC: 85.9 ± 0.4 DB: 84.7 ± 1.0 WC + DB: 84.1 ± 0.6 BC + DB: 84.0 ± 0.9 | WC: 81.9 ± 1.5 DW BC: 78.3 ± 0.9 DW DB: 84.0 ± 0.6 DW WC + DB: 82.7 ± 2.1 DW BC + DB: 83.9 ± 0.4 DW | Captured in Canary Islands, Spain; fed with different diets for 8 weeks (n = 8 for each diet) | Estefanell et al. [34] | |

| Octopus vulgaris | 81.87 ± 2.12 | 14.230 ± 0.225 | 5.8 * | Wild octopus; Ionian Sea, Southern Italy | Prato et al. [35] |

| Octopus vulgaris | DG I: 82.05 ± 1.28 DG II: 81.73 ± 2.87 DG III: 81.42 ± 2.41 DG IV: 81.58 ± 1.82 DG V: 81.73 ± 2.51 | DG I: 14.376 ± 0.221 DG II: 14.718 ± 0.256 DG III: 14.884 ± 0.147 DG IV: 14.740 ± 0.292 DG V: 14.690 ± 0.281 | DG I: 5.7 * DG II: 5.6 * DG III: 5.5 * DG IV: 5.5 * DG V: 5.6 * | Captured in Ionian Sea, Southern Italy; Cultured octopus, with different diets (n = 10 for each diet) | Prato et al. [35] |

| Octopus vulgaris, Octopus mimus, and Octopus cyanea | 83.4–90.1 | 6.5–14.8 | 9.5 ± 1.9 (5.6–13.8) | Frozen octopus available in markets from Portugal; n = 25 (23 samples of Octopus vulgaris) | Mendes et al. [5] |

| Octopus maya | ECA: 92.2 ± 2.0 (90.5–94.9) WCA: 86.1 ± 1.7 (84.0–88.0) | Markets from the NW region of Portugal; ECA and WCA: n = 8 | Torrinha et al. [40] | ||

| Octopus maya | WCA: 89.1 (84.0–94.9) | Markets from the NW region of Portugal; n = 48 | Oliveira et al. [41] | ||

| Eledone cirrhosa | 76 | 16.2 | 4.7 * | Bay of Biscay; n = 3 | Spitz et al. [36] |

| Eledone cirrhosa | immature: 81.19 in mantle 80.21 in arms mature: 80.04 in mantle 78.54 in arms | immature: 15.67 in mantle 16.64 in arms mature: 15.85 in mantle 17.89 in arms | 5.2 * 4.8 * 5.0 * 4.4 * | Galician shelf; summer; n ≥ 30 | Ruiz-Capillas et al. [37] |

| Eledone cirrhosa | NEA: 84.1 ± 1.6 (82.0–85.9) | Markets from the NW region of Portugal; NEA: n = 8 | Torrinha et al. [40] | ||

| Eledone cirrhosa | NEA: 83.1 (79.6–85.8) | Markets from the NW region of Portugal; n = 24 | Oliveira et al. [41] | ||

| Eledone moschata | S: 84.64 ± 0.39 A: 83.12 ± 0.21 W: 82.79 ± 0.20 | S: 12.21 ± 0.62 A: 14.32 ± 0.36 W: 14.50 ± 0.42 | S: 6.9 * A: 5.8 * W: 5.7 * | Eastern Mediterranean sea; n ≥ 3 | Ozogul et al. [39] |

| Actual Groups | Predicted Groups Membership | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O. vulgaris Control | O. vulgaris Water-Added | E. cirrhosa Control | E. cirrhosa Water-Added | |||

| Model 1—all trials/samples were used for training | ||||||

| Samples used for training | O. vulgaris control | 74 (97.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 76 |

| O. vulgaris water-added | 1 (0.4%) | 227 (98.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.3%) | 231 | |

| E. cirrhosa control | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 44 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 44 | |

| E. cirrhosa water-added | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 132 (100.0%) | 132 | |

| Total | 75 | 227 | 46 | 135 | ||

| Model 2—1/3 of the trials were used for testing (4 trials of O. vulgaris and 2 trials of E. cirrhosa were used for training) | ||||||

| Samples used for training | O. vulgaris control | 50 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 50 |

| O. vulgaris water-added | 0 (0.0%) | 153 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 153 | |

| E. cirrhosa control | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 32 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 32 | |

| E. cirrhosa water-added | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 96 (100.0%) | 96 | |

| Total | 49 | 153 | 32 | 96 | ||

| Samples used for testing | O. vulgaris control | 25 (96.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 26 |

| O. vulgaris water-added | 5 (6.4%) | 60 (76.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (16.7%) | 78 | |

| E. cirrhosa control | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 | |

| E. cirrhosa water-added | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 36 (100.0%) | 36 | |

| Total | 30 | 60 | 13 | 49 | ||

| Cross validation (5-fold) | ||||||

| Samples used for testing | O. vulgaris control | 74 (97.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 76 |

| O. vulgaris water-added | 1 (0.4%) | 226 (97.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (1.7%) | 231 | |

| E. cirrhosa control | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 44 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 44 | |

| E. cirrhosa water-added | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 132 (100.0%) | 132 | |

| Total | 75 | 226 | 46 | 136 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teixeira, B.; Vieira, H.; Martins, S.; Mendes, R. Development of a Rapid and Non-Destructive Method for the Detection of Water Addition in Octopus Species (Octopus vulgaris and Eledone cirrhosa) Using Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR). Foods 2023, 12, 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12071461

Teixeira B, Vieira H, Martins S, Mendes R. Development of a Rapid and Non-Destructive Method for the Detection of Water Addition in Octopus Species (Octopus vulgaris and Eledone cirrhosa) Using Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR). Foods. 2023; 12(7):1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12071461

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeixeira, Bárbara, Helena Vieira, Sandra Martins, and Rogério Mendes. 2023. "Development of a Rapid and Non-Destructive Method for the Detection of Water Addition in Octopus Species (Octopus vulgaris and Eledone cirrhosa) Using Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR)" Foods 12, no. 7: 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12071461

APA StyleTeixeira, B., Vieira, H., Martins, S., & Mendes, R. (2023). Development of a Rapid and Non-Destructive Method for the Detection of Water Addition in Octopus Species (Octopus vulgaris and Eledone cirrhosa) Using Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR). Foods, 12(7), 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12071461