Abstract

Food neophobia and pickiness are the resistance or refusal to eat and/or avoid trying new foods due to a strong reaction of fear towards the food or an entire group of foods. This systematic review aims to assess evidence on the risk factors and effects of food neophobia and picky eating in children and adolescents, giving elements to avoid the lack of some foods that can cause nutritional deficiencies, leading to future pathologies when they are adults. A systematic literature search was performed in Medlars Online International Literature (MEDLINE) via Pubmed and EBSCOhost, LILACS and IBECS via Virtual Health Library (VHL), Scopus, and Google Scholar. MeSH terms used were: ((food neophobia [Title/Abstract]) OR (picky eating [Title/Abstract]) OR (food selectivity [Title/Abstract])) NOT ((anorexia nervosa [MeSH Terms]) OR (bariatric surgery [MeSH Terms]) OR (avoidant restrictive food intake disorder [MeSH Terms]) OR (autism spectrum disorder [MeSH Terms])). One hundred and forty-two (n = 142) articles were selected for children and adolescents (0–18 years old). They were structured according to contents: prevalence, risk factors, consequences, strategies and treatment. The studies showed a prevalence of the need for intervention on modifiable risk factors. Food neophobia and pickiness developed in childhood are conditioned by risk factors related to biological, social, and environmental characteristics, as well as family education and skills. Strategies to minimize or avoid these disorders should be aimed at implementing healthy habits at these levels.

1. Introduction

Food selectivity, neophobia, aversion, and avoidance, as well as picky eating, are all terms used to describe that children do not eat [1]. In children and adolescents, the concept of food neophobia is linked to eating or appetite disorders, picky eating or food fussiness [2]. Eating disorders are defined as those with some of the following characteristics in the individual way of eating: not eating enough, eating frequently very selectively, eating frequently slowly, and showing unwillingness to eat certain foods [3].

Food neophobia and fussy eating behavior are determined by biological, anthropological, economic, psychological, socio-cultural, and home-related factors, and their influences compete, reinforce, and interact with each other [4]. This behavior is one of those responsible for a decline in the variety of food consumption and, conversely, of nutritional intake, as well as be a barrier to ensuring that the child eats healthy diets, associated with a high level of conflict and stress in the family and school environment at meal time [5]. Fussy eating behavior is a significant challenge for many families of school-aged children. Parents’ feeding goals, practices and the negative emotional impact of fussy eating have been widely reported in previous studies [6,7,8]. It has been pointed out how a mother reported little concern despite her son eating little amount of vegetables, or he did not eat vegetables at all; other parents reported higher levels of concern, uncertainty and inconsistent practices despite their child reportedly consuming a relatively balanced diet; many parents were aware of strategies for managing picky eating challenges, but encounter difficulties implementing these strategies; other parent restricted their children from eating sweet foods in the past, but as the child grows up and goes to school, educating the child to be able to make their own choices becomes a higher priority; and other parents avoided conflicts and provided a balanced meal, or wanted a child to eat more and promoting child autonomy/self-regulation. Most parents adapted their goals in front of the children’s picky eating according to contextual factors such as time, energy levels and day of the week; many parents felt it important to create a positive mealtime environment and expressed efforts to avoid conflict [5].

Food neophobia or aversion is defined as the resistance or refusal to eat and/or avoid trying new and unfamiliar foods due to a strong reaction of disgust or fear towards the food or entire group of foods, both visually and tasty [9]. Sensory characteristics have been reported as the most influential determinants of eating behavior, and among these, textures are the main reason for food rejection or acceptance in children [10,11,12]. The feeding style (urging the child to eat, unpleasant emotions during the meal, parental eating habits, neophobia in the mother, and others) has also been reported as having a great effect on the food neophobia appearance [13]. Food neophobia is one of the children’s eating behaviors that causes parents great concern [14,15]; it has been included in the group of feeding disorders or selective eating, which is part of the broader group of sensory food aversions [16]. Neophobic behaviors can appear as early as the first year of life but most often intensify between 18 and 24 months of age, which is related to the child’s increased mobility. Food neophobia is a natural development stage that usually resolves spontaneously, but its occurrence can influence the perpetuation of future inappropriate behaviors [1].

Picky eating is generally classified as feeding disorder, and it has been defined as unwillingness to both eat familiar foods and try new foods, and showing strong food preferences severe enough to interfere with daily routines to the extent that is problematic to the parent, child, or parent–child relationship [17], as well as restricted intake of food, leading inducing parents to provide menus different from those of the other family members [18]; a low number of food in the diet, special preparation of foods required [19,20] and consumption of inappropriate food variety by avoiding/rejection of familiar or unfamiliar foods [21,22]. The age of picky eating in children has been reported below the age of 1 year, perhaps related to parental picky eating [17], and it mainly appears in populations from developed countries despite their ethnic origin [23,24]. The picky eating development can be affected by the following factors: parental feeding style and monitoring, pressure to eat, personality, social influences [23,25], reduced duration of breastfeeding, and early introduction of complementary foods [26,27].

The neophobic attitude is evolutionary and important to protect individuals from ingesting dangerous foods; as omnivorous species, to survive, humans have to distinguish between safe and poisonous food [1]. This dislike for one or more foods could be considered an adaptive and emotional reaction of human beings to protect themselves from contamination or disease and feel safe in front of plants or animals with toxic properties [28]. Currently, neophobia is a useful mechanism in early childhood linked to the development of a sense of taste; the attitude of distrust toward novelty protects the child from the danger of eating something potentially dangerous to health [29]. Hence, these avoidance behaviors can also be beneficial for obtaining and consuming food [1].

Food preferences and aversions are shaped by the chemosensory system underlies taste, touch, sight, and smell perception [30]. Consequently, disgust in front of foods motivates avoidance behavior and triggers specific disgust stimuli, which are responded to through parasympathetic activation, activation of specific facial muscles, appraisals of contamination, and oral rejection [20].

The main differences between food neophobia and pickiness are that food neophobia is usually considered as the refusal to eat/avoid new foods and to refuse to eat unknown foods. Instead, picky eaters are generally defined as those children who consume an inappropriate variety of foods, with a lack of will to eat certain foods that are meticulous, by rejecting a high number of familiar and unfamiliar foods, both novel and traditional to them. It appears that the picky eaters will need more exposure to certain foods to accept them than the food neophobes [21,31].

Pickiness and food neophobia are closely related in terms of some characteristics of the individuals. In some cases, both disorders coexist [31]. Food neophobia and pickiness showed that inter-relationships and social and parental factors would have analogous effects on the magnitude and length of expression in both food neophobia and pickiness. These parameters can be modified in different ways by age, taste/tactile ability, culture, and environment [21]. Food neophobia is part but not the entirety of pickiness behavior and a constituent of unwillingness to try novel foods. The effect of food neophobia on the child’s willingness to try a new food decreases from the first taste assimilated as positive; after that, the rejection of a flavor will no longer be part of the child’s food neophobia, and persistent rejection should be considered as part of pickiness. Developmental aspects of food neophobia and pickiness are linked to the child’s mobility, resulting in a slower period of maturation in pickiness than in food neophobia [21].

Rejection of several foods, mainly vegetables and fruits, may cause serious health consequences due to deficiencies of certain essential nutrients, especially vitamins and minerals, derived from the absence of these foods in the diet [1,32]. Neophobic children eat fewer vegetables, fruit, milk, and dairy products than those recommended, with negative consequences on health resulting from a poor diet [33,34]. All of these food avoidances may be especially harmful to children and adolescents since they are growing organisms.

To establish the health strategies needed to modify eating patterns, it was necessary to create useful tools to measure the level of food neophobia, as well as to determine which foods are necessary to define the most appropriate interventions. Currently, there are validated and established tools and scales as references widely used by the scientific community. Some of these tools were validated in different populations due to the differences found in neophobias linked to the food characteristics and culture of different ethnic and/or socioeconomic groups [35].

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the evidence on the risk factors and effects of food neophobia and picky eating in children and adolescents, giving elements to avoid the lack of some foods that can cause nutritional deficiencies, which will lead to future pathologies when they are adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Review Protocol, Information Sources, and Search Strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [36] guidance was used, with the protocol of this systematic review registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO ID: CRD42024566754). This systematic review also followed the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison Outcomes, and Study type) guidelines for systematic reviews commonly used to identify components of clinical evidence for systematic reviews in evidence-based medicine [37,38]. PICOS used are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

PICOS used.

The systematic review was performed up to April 2024. Searched literature has been retrieved from the MEDLINE database via PubMed and EBSCOhost, LILACS and IBECS via Virtual Health Library (VHL), Scopus, and Google Scholar, using the following combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: food neophobia [Title/Abstract] OR picky eating [Title/Abstract] OR food selectivity [Title/Abstract] NOT anorexia nervosa [MeSH Terms] OR bariatric surgery [MeSH Terms] OR avoidant restrictive food intake disorder [MeSH Terms] OR autism spectrum disorder [MeSH Terms]. Seven hundred and thirty-four articles were initially selected.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Original peer-reviewed research papers written in English or Spanish, only in humans, and made between 2000 and 2024 were considered. A total of 479 articles were obtained.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Reviews and case reports were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were irrelevant study objectives for the current review, irrelevant study design for the review and irrelevant association. Studies where the measurement of food neophobia was made on a population with diseases (cancer, intolerance, allergies, etc.) and patients with ARFID (Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder), were excluded since it is an eating disorder in the food fussiness domain, causing more severe impairments than food neophobia and limiting a wider range of food intake [39]. After that, three hundred and twenty-seven articles were selected. The last exclusion criterion applied was the age of the population (0–18 years old), discarding those carried out on adults (≥18 years, n = 95), mixed ones (0–99 years, n = 2) and those carried out on children with content irrelevant to the study (n = 90). Finally, 142 articles conducted in the pediatric population (between 0 and 18 years) were selected.

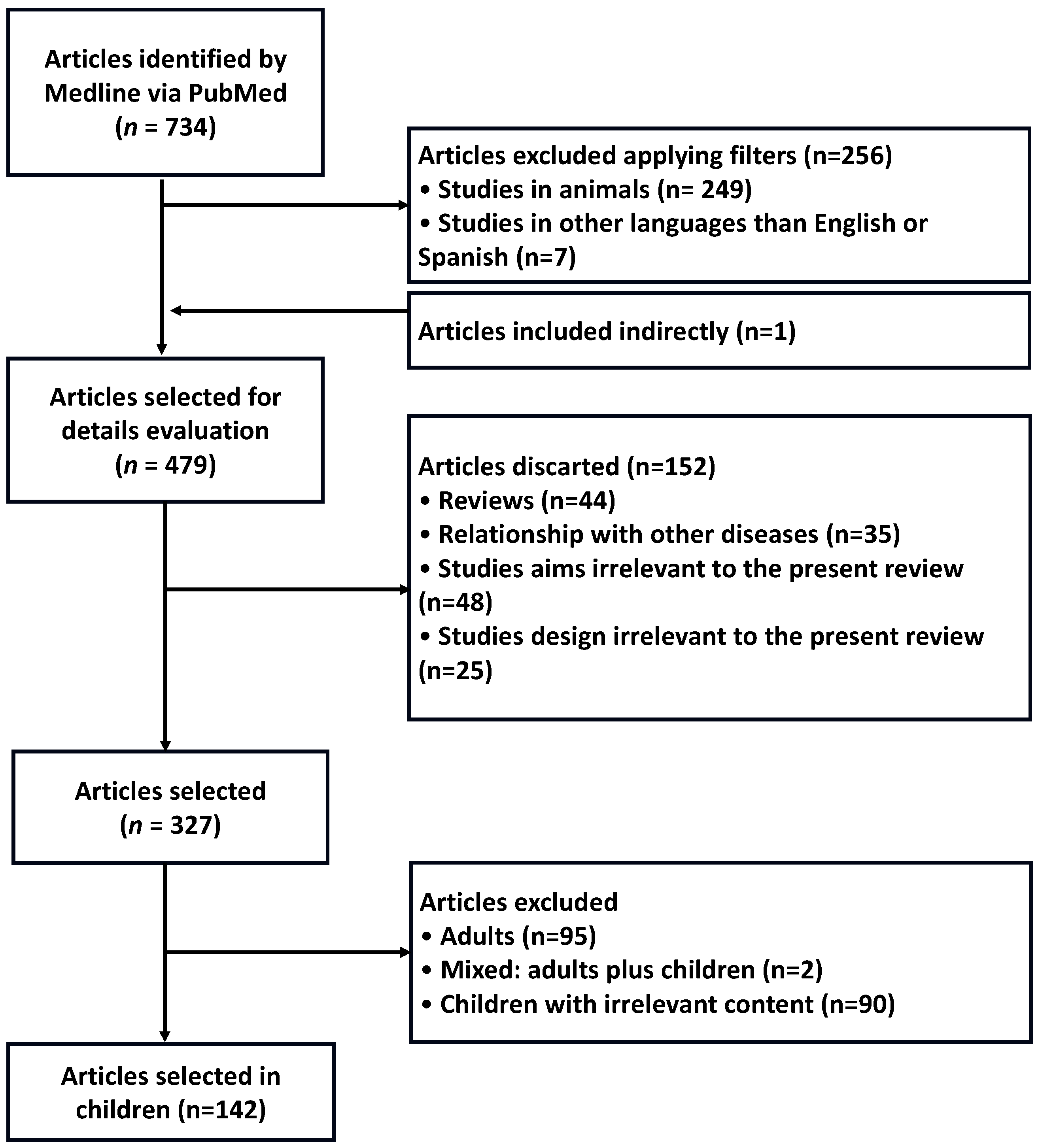

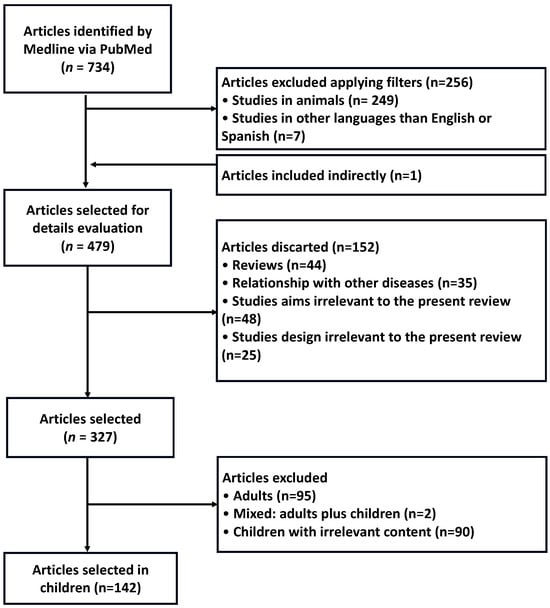

A flowchart to report on the information flow during different stages of this review, showing the number of literature records found, included, and excluded, as well as the rationale for exclusion, has been created and shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart highlighting the selection process of articles.

2.4. Study Selection

Initially, titles and abstracts of papers were screened for the relevance of their thematic fit, related to the focus or theme of the study. Following title and abstract screening, full texts of selected studies are thoroughly examined in the next step to assess their eligibility. If the information in titles and abstracts was unclear, additional context or full-text examination was used to make an informed decision. The articles were reviewed by at least two reviewers and were considered for the selection criteria listed by the Joanna Briggs Institute, a procedure to independently assess the methodological quality of scientific articles [40]. Two reviewers performed screening independently. Any discrepancies or disagreements in the screening process were addressed through discussion and consensus among the reviewers and the third author if needed.

2.5. Data Collection and Extraction

Two team members extracted data independently, which was critically reviewed by the other team members at the end of this step. Articles were classified into new tools to measure neophobia; classification and prevalence of food disorders and related risks; effects of food neophobia and picky eating risk factors; consequences linked to food neophobia; macronutrient and food restriction; micronutrient restriction; food neophobia strategies and treatment; other minor results.

The quality of analyzed studies, including the risk of bias, was assessed through the Cochrane Risk of Bias-2 tool [41], as well as the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [42] for non-randomized studies, including case-control and cohort studies, although some criticism of it has been reported [43].

3. Results

For the PICOS, 44.5% of articles were relevant after the title and abstract stage (327 articles/734 articles), and 43.4% (142/327 articles) were confirmed to meet the inclusion criteria after full-text review.

The 142 selected articles focused on the prevalence, risk factors and consequences, and strategies to minimize or avoid food neophobia and picky eating in children. Specific measurement tools were used to determine these questions, detailed in Table 1. Eighty-seven percent of the articles reported results in equal proportion on the terms food neophobia (FN) and picky eating (PE); 13% of the articles did not directly determine the concepts neophobia or pickiness, but their results were in line with feeding difficulties in childhood, matching the determinant causes and risk factors.

The results were obtained by comparing the neophobic and neophilic groups or PE with non-PE or by comparing the distinct levels of neophobia and pickiness, respectively. According to the age of the individuals in the sample, the information under study was obtained through surveys carried out on the individuals themselves (self-reported) and sometimes obtained from parents’ and caregivers’ responses (indirect information), with the consequent bias that the first option may entail.

The scales or measurement tools used in these studies were mainly: the Child Food Neophobia Scale (CFNS; n = 34), Food Neophobia Score (FNS; n = 31) and Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ; n = 26). Validated but minority measurement tools were used in 22 articles. The methodology was used in 28 articles without validation and only with observational measures. Among them, eight of these articles [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] talked about the validation of new tools to measure neophobia under different premises, such as adaptation to different origins of the population or delimiting the FN or PE measured to specific food groups.

One hundred and six articles were cross-sectional, 17 were prospective, 10 were Randomized Controlled Trials, and 3 were cases and controls. Minority studies (n = 4) were cohort (n = 1) and clinical trials.

A low risk of bias in the reviewed articles was determined by applying the domains of the Cochrane Risk of Bias-2 tool (Domain 1: Risk of bias arising from the randomization process; Domain 2: Risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions; Domain 2: Risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions; Domain 3: Missing outcome data; Domain 4: Risk of bias in measurement of the outcome; Domain 5: Risk of bias in selection of the reported result; and Overall risk of bias). The quality of case-control and cohort studies, following the Newcastle–Ottawa Score, was high (total quality score = 7).

The sample size was very different between the reviewed papers. Most of the papers followed from 100 to 500 subjects. Just 28 studies were carried out on populations with less than 100 individuals, and 19 studies followed more than 1000 individuals. The highest studies were developed in Bristol (UK) as a prospective study on 6608 children aged 4–15 months [35] and in Avon (UK) as a longitudinal study on 7285 children aged 7 years [52].

All studies assessed the 0–18-year-old pediatric population, except two papers that worked on 19–20-year-old or older subjects [53,54]. Studies were conducted on the USA, European, Asian, and Australian populations. All findings are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of the reviewed studies: Authors, study design, participants (n; age), aims, applied methods, and main results.

3.1. Results on Prevalence of Food Disorders and Related Risks

Seventeen papers assessed the classification and prevalence of food disorders, as well as the related risks for serious disorders, such as FN, PE or even Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID). Bialek-Dratwa et al. [55] classified children into four groups, from risk level 0 (no risk) to level 3 (highest serious food disorders). In a cross-sectional study on 2550 children [56], picky eating disorders were classified into two groups: persistent and non-persistent, with a prevalence of 8 and 5%, respectively. Other studies classified children as slightly persistent, medium persistent, and somewhat persistent [57]. In a prospective study conducted on 2068 children in 2022, a PE prevalence of 16.7% was reported [58]. Another prospective study [59] showed a prevalence of 22.5% for persistent pickiness. The prevalence of PE in cross-sectional studies was 67.5% [60], 29% low persistent PE, 57% medium persistent and 14% high persistent PE [61], 34% PE [57], 30% severe PE [62], 26% PE [63], 4.9% severe PE [44], 62% PE [64], 25.1% PE [65], 59.3% PE [66], and 54% PE [67].

The prevalence of food neophobia has been quantified around 14–16% [57,68,69], but other studies reported a much lower prevalence of 1.8% [70].

Associations have been described between children’s PE and parental feeding habits or mother feeding habits, but no sex effect as father–boy and mother–girl associations have been described in the reviewed papers, except one article describing how mothers influenced fruit and vegetable consumption of daughters through their own patterns of fruit and vegetable consumption and influencing tendencies of daughters to be picky [71].

3.2. Effects of Food Neophobia and Picky Eating Risk Factors

Among the articles reviewed, 48 studies dealt with the effects of risk factors that can cause or amplify neophobia and food selectivity or picky eating (PE), including genetic and, environmental and social factors [72,73,74]. Regarding genetic factors, the heritability of being picky and neophobic is a highly transmissible trait [75], up to 72% [76]. There were studies on environmental factors with very different results. Food neophobia was pointed out around 14–16% [57,68,69], but other studies reported a much lower prevalence of around 1.8% [70].

Regarding age as a risk factor, it was pointed out that a child’s age determines the extent to which several factors affect food picky eating [77], as well as the point of highest level of pickiness appears at 4–5 years of age [22,50,78]. It was also determined that the age of onset was 3–4 years [79]. Several authors reported a decrease in the persistence of pickiness with age (56,80,81), which remained stable from preschool to school age [67]. In the Donald study, a decrease in neophobia during adolescence was also described [82].

Analyzing sex as a risk factor, it was shown that there was higher risk of developing picky eating in males [22]. No relationship was observed between sex and FN [69,83], but females showed differences in the intake of vegetables according to the FN category [84]. There is no association between PE and ethnic or maternal BMI [81], except one study showing higher risk of picky eating in children of obese mothers [85].

The risk factors with the highest influence on the development of picky eating and food neophobia were related to parental strategies, showing a direct effect [52,86,87] from the parents’ habits, education, feeding (maternal or external breastfeeding, and introduction of solid foods), the form of exposure, and socioeconomic factors surrounding the family nucleus.

Breastfeeding and its duration were declared a conclusive risk factor in the FN and PE development [88]. There was evidence that exclusive breastfeeding until 4 or 5 months compared to exclusive breastfeeding only from 0 to 1 month decreased the likelihood of pickiness [89]. The late introduction of solid and semi-solid foods into the child’s diet was associated with higher levels of picky eating [32] and FN [27]. However, other studies showed that the age of introduction of solids did not show an association with the dietary risk posed by picky eating and FN [90].

The main difficulties at feeding time were the perceived tension at mealtime, both by the children themselves and externally [6,64,91], parental anxiety [79,92], and those derived from an increased pickiness [93] and neophobia [94]. Persistent PE can be a symptom/sign of pervasive developmental problems but does not predict other behavioral disorders. Remitting PE was not associated with adverse outcomes of mental health [73].

Several studies found that there was an increased risk of developing picky eating when parents were picky eaters [62,95]. Mostly, parents and caregivers themselves were unaware of the relationship between their neophobias and those developed by the children [96], with a positive association between children’s neophobia and those of parents [82,97,98]. Neophobic mothers usually exposed their children to unhealthy foods and consumed less fruit and vegetables, and their neophobias usually coincided with those of their children [26,99,100]; therefore, they can be considered as predictors of food behavior in children [101]. On the other side, mothers who are high consumers of fruits and vegetables usually put less pressure on their daughters, who are less demanding of food [71]. An isolated study showed that knowledge of vegetables, identification of sensations, and the willingness to try vegetables had no effects on neophobia [102].

The kind of education and family eating practices had a direct implication on neophobia and picky eating development [103,104], and parental neophobia is a food fussiness independent determinant [77]; however, further research would be needed to determine it [105]. So, promoting autonomy and praise had a positive influence on the consumption of vegetables [106], as well as a positive climate before mealtime [107]. On the other hand, control and coercive eating practices increased PE levels [104] and led to more problematic behaviors [108]. However, this review found a study that showed the opposite; it said that the covert control of mothers improved the quality of the children’s diet [109].

The parental socioeconomic status was not associated with picky eating [48], but several articles showed an association between picky behavior and low income [110]. Home food insecurity is precisely another factor to be considered because it can make it difficult to access and be exposed to foods such as fruits [111,112]. Moreover, higher neophobia levels in rural areas were due to lower exposure to different foods [103] compared to urban areas.

Regarding relationships with senses, FN was slightly correlated with high taste and olfactory reactivity in children, which could trigger low consumption of fruits and vegetables [112,113,114]. On the other side, FN was not related to tactile enjoyment [115], but children who were defensive to touch had more picky traits [116]. The food’s visual appearance also played an important role in FN [117]. It can be concluded that low-sensitive individuals showed lower levels of food neophobia and higher food acceptability [118].

3.3. Results on the Consequences Linked to Food Neophobia

There was no significant association between FN and altered BMI [24]. However, nine studies showed that medium and high persistence of pickiness was associated with low BMI [32,61,119,120] and slightly lower weight [58,67,114,121,122]. It also showed the decreasing effect of pickiness on fat mass [119], but at the same time, with no effect on body fat percentage and fat mass index [123]. It was also found lower BMI in children of parents worried because their children did not eat and parents who pressured children to eat [124]. Few articles reported that food neophobia predisposed to overweight [125] or that obesity and overweight were significantly higher in food neophobic and picky eaters [126].

No significant differences were reported between the dietary intake of PE and non-PE [127], but differences both in behavior and food consumption [2] and total energy intake [128] were also found. The most important consequence was the association of food neophobia with poor diet quality [69,129], due in some cases to the lack of interest in food that neophobia induces [130]. High levels of FN and picky eating were associated with lower hedonic reactions to food [19], and strongly relationship with fruit and vegetable consumption [104]. High adherence to the Mediterranean Diet was associated with a low level of food neophobia and better hedonic scores regarding food [8]. An association between high levels of food neophobia and low awareness of hunger and satiety in childhood was also reported [103]. An FN increase appeared with some textures [131].

3.4. Macronutrient and Food Restriction

Picky eaters consumed sugary foods and drinks more frequently [132,133] and low fruits, vegetables [101,120,128,131], and proteins [67,81,134,135]. High levels of neophobia were also related with low fruit and vegetable intake [70,84,125,136,137,138,139], and a reduced intention to try them [99,140,141], high intake of saturated fats [33] and, specifically, of trans fatty acids [85]. Moreover, low fruit and vegetable consumption and decreased protein intake were reported among sedentary people living in suburban areas [82]. Low levels of neophobia, according to the Child Food Neophobia Scale (CFNS), were associated with high consumption of vegetables [142].

3.5. Micronutrient Restriction

The picky condition reduced the consumption of folates, Mg, K, Vitamin B1, B2, B3, B6, D and E [33,134] and decreased the intake of Fe, carotene, and Zn, which are related to low meat intake, fish, vegetables and fruits [67,133]. Otherwise, when the level of pickiness decreased, the prevalence of Zn deficiency also decreased [60,134].

Among the most notable consequences of FN, there was the need for psychological support, with a prevalence of 37.5% [143]; 60% of parents needed practical support, 47.7% needed emotional support, and 16.2% needed nutritional support [144]. Likewise, high levels of neophobia decreased self-concept at a social, physical and academic level and increased anxiety levels in both children and adolescents [145]. High FN levels were associated with more crying episodes during meals and high food rejection [146]

3.6. Results on Food Neophobia Strategies and Treatment

Strategies for FN were discussed to improve pickiness since this disorder altered family and social life [92,143], making difficult relationships between their members and children’s normal development. Different interventions to reduce food neophobia and promote healthy lifestyle habits have been described. There were individual interventions on specific family nuclei and collective interventions at the level of kindergarten or nurseries, as well as at primary and secondary educational centers and on the parents. At the collective level, intervention found improvements in feeding practices, dietary variety, quality, and cognitive children development [146], as well as improvements in the intention to try [147] and the consumption of vegetables after practical intervention in preschool [148,149].

Several strategies were willingness to try tests [141], exposure and reward tests [129], and sensory education programs [150]. Several studies showed that food neophobia and pickiness were decreased by visual exposure to vegetables [151], increasing the desired effect when visual, tactile and sensory exposure were considered [152].

3.7. Other Minor Results

The increased risk of picky eating in children was found in mothers who smoked during pregnancy [153]. Meal timing was not associated with fussiness about food [154] and decreased risk of picky eating with moderate physical activity, adequate sleep, and less than 2 h of screen exposure per day [95]. The higher cognitive development, the lower the levels of neophobia [155].

4. Discussion

Food neophobia (FN) is the resistance or refusal to eat and/or try new foods, and picky or selective eating is the refusal to eat food, or they eat the same foods over and over [1,9]. Prevalence and incidence of picky eating have been reported as higher than those of FN. The differences in the described prevalence and incidence between FN and pickiness can be understood due to the different severity between FN and pickiness, where the former (FN) has more symptoms than the latter (pickiness), but also that FN could be solved spontaneously at early age of children [1], whereas pickiness could remain despite the age of children and adolescents [17]. Moreover, most of the studies on FN and pickiness are cross-sectional and few long-term; therefore, there have been no opportunities yet to study accurately the prevalence of FN and picky eating.

This review reinforces that food neophobia and picky eating are the primary causes of decreased diet quality in children and adolescents since the possible consequences of food neophobia and picky eating is the alteration in the individual’s weight due to the loss of dietary balance through the lack of several important foods [156]. A consequence is the possibility that individuals with FN could suffer a decrease in weight and BMI due to total caloric restriction or, on the contrary, they would increase in weight and BMI due to poor food choices that would cause very pronounced and persistent FN [157]. The studies found calorie restriction and low weight with impact on adherence to the Mediterranean Diet, which protects against most prevalent chronic diseases [158], thanks to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant components of foods such as fruits, vegetables and fish, whose consumption decreases disorders such as food neophobia and picky eating [68,112,159,160].

The tools available to reduce or eliminate FN are disparate and do not cover the entire population, which must be stratified according to age and origin so that the data will be comparable. FN should be treated from two perspectives: detailed knowledge of the risk factors and their influence and treatment of the consequences of the loss of dietary variety and nutritional balance. Furthermore, FN should be considered a chronic disease or disorder, which can last more than two years in 40% of cases [18].

Today the risk factors surrounding FN and pickiness are unclear, its long-term consequences nor the main strategies to avoid or minimize it, but there is evidence that childhood eating behaviors often predict eating behaviors in adults. The research carried out so far has concluded that overcoming the biological, familial, environmental and social factors that promote these behaviors will contribute to minimizing their prevalence and long-term consequences [161].

Sex and body weight showed little influence, and age had a moderate influence on food neophobias but is a risk factor in pickiness, mostly in children than in adolescents [50,77,78,79,82,112].

Breastfeeding and its duration have been declared a conclusive risk of FN and pickiness; the longer breastfeeding, the lower the prevalence of FN or pickiness [88,89]. There is no conclusive evidence yet on the effect of the introduction of solid or semi-solid foods into the child’s diet on FN and pickiness [27,32,90].

The literature highlights the need to address environmental and modifiable risk factors to balance the genetic expression of FN and picky eating and eating education, and coercive practices at the family level is the starting point for parents to make correct food decisions regarding their children and adolescents [86]. Parental neophobia should also be considered [77].

Once the teaching process is saved, secondary risk factors (exposure to a variety of foods, environments with greater food insecurity, socioeconomic level, educational level, smoking habit, sleep time, screen time, physical activity or others) would be more easily tackled through collective interventions.

The dietary approach through wide exposure to a variety of foods is used to diminish the aversion to most neophobic foods, such as fruits and vegetables, especially at early ages, with the intention that current social habits regarding the consumption of food with high energy density and scale or no dietary quality, are limited due to both parental education and government strategies that increase the possibility of consuming healthy foods.

Non-modifiable factors such as heritability should, likewise, be able to be counteracted by education and positive and healthy food environments. The strategies must be aimed at the family environment in its entirety, from parental habits (feeding during pregnancy, established lifestyle habits…) to the strategies used from the first day of birth (from the type of breastfeeding, the introduction of solid foods and different textures, to parents’ teaching). At the level of social factors external to the family, actions and strategies addressed to promote healthy lifestyle habits and make difficult access to unhealthy foods and eating practices are encouraged, especially in an age group as vulnerable as children and adolescents.

The need for collective interventions in terms of learning strategies and emotional management of hedonism and aversion to food is unquestionable due to the high prevalence data of these disorders, which emanate from most of the studies reviewed, their persistence in adulthood and their consequences on health. Most of the educational programs and related activities found in the literature addressed the problem of familiarity and exposure to foods in the interest of finding and creating positive eating environments [162]. The globalization of food cultures would open the door to familiarization with non-native foods, and, given that exposure, the effect of rejection of both known and unfamiliar foods would be naturally limited [133]. Familiarity with foods and educational activities are suggested as useful in decreasing food neophobias among children and adolescents [112].

In summary, at the family level, the main interventions to reduce or avoid FN and picky eating should be addressed in three aspects: parental and children–adolescents co-education, training, oral sensory learning in feeding, and avoiding parental coercive practices, especially at mealtime [163]. At the biological level, sex, body weight, and age had moderate effects on FN and pickiness, whereas breastfeeding and its duration were demonstrated to be a factor in decreasing these eating disorders. At the social level, it is highly encouraged to implement, extend and improve sustainable and healthy food environments through political actions, as well as to promote healthy lifestyle habits [163].

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The main difficulties encountered in the study have been differences between the validated scales and the specific and isolated methodologies used in many studies. In the paediatric population, difficulties have been found in validating and using the scales depending on whether they were answered directly by the children or were reported by the parents, as a specific method or by the age of the child. All of them can be considered as biases between the reviewed studies.

5. Conclusions

Food neophobia and pickiness developed in childhood are conditioned by risk factors related to familiar, biological, social, and environmental characteristics, as well as family education and skills. Therefore, strategies to minimize or avoid these disorders should be aimed at implementing healthy habits at these levels.

Author Contributions

C.d.C., C.B. and J.A.T. provided literature searches, reviewed the literature, prepared the main outline of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was received from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, through the CIBEROBN CB12/03/30038, which are co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund. Red EXERNET-Red de Ejercicio Físico y Salud (RED2022-134800-T) Agencia Estatal de Investigación (Ministerio de Ciencias e Innovación, Spain). The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Medicinal Research Ethics Committee of the Ciudad Real General University Hospital, Spain (ref. C-498; 22 February 2022). The written consent of the participants was obtained. The results and writing of this manuscript followed the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) guidelines on how to deal with potential acts of misconduct, maintain the integrity of the research and its presentation following the rules of good scientific practice, the trust in the journal, the professionalism of scientific authorship, and the entire scientific endeavor. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents and children to publish this paper, if applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

There are restrictions on the availability of the data of this trial due to the signed consent agreements around data sharing, which only allow access to external researchers for studies following the project’s purposes. Requestors wishing to access the trial data used in this study can make a request by emailing pep.tur@uib.es.

Acknowledgments

The authors especially thank the participants for their enthusiastic collaboration. CIBEROBN is an initiative of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

ARFID: Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder; BMI: body mass index; CBCL: Child Behavior Checklist; CEBI: Children’s Eating Behavior Inventory; CEBQ: Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire; CFNS: Child Food Neophobia Scale; CFPQ: Child-reported Food Preference Questionnaire; CFQ: Child Feeding Questionnaire; CFRS: Child food rejection scale; CFSQ: Caregiver’s Feeding Styles Questionnaire; FAS: Food Attitudes Scale; FFLQ: Food Familiarity and Liking Questionnaire; FFQ: Food frequency questionnaire; FN: Food Neophobia; FNS: Food Neophobia Scale; FNTT: Food Neophobia Test Tool; FR-WTT: Farfan-Ramírez Willingness To Try; FSQ: Food Situations Questionnaire; FVNI: Fruit and vegetable neophobia instrument; FVNI: Fruit and Vegetable Neophobia Instrument; GHQ-28: Goldberg’s General Health Questionnaire; IFSQ: Infant Feeding Styles Questionnaire; LBC: Lifestyle Behavior Checklist; MCHFS: Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale; Mo: months of age; PAQ: Parental Authority Questionnaire; PCI: Parental Control Index; PE: Picky Eating; PEQ: Picky Eating Questionnaire; PFQ: Preschooler Feeding Questionnaire; PFQ: Preschooler Feeding Questionnaire; PSI-SF: Parent Stress Index Short Form; QENA: Questionnaire on Food Neophobia among French-speaking children; SFQ: Stanford Feeding Questionnaire; TNFS: Trying New Foods Scale; WTNF: Willingness to Taste Novel Food; YR: years of age.

References

- Białek-Dratwa, A.; Szczepánska, E.; Szymánska, D.; Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Kowalski, O. Neophobia—A Natural Developmental Stage or Feeding Difficulties for Children? Nutrients 2022, 14, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boquin, M.; Smith-Simpson, S.; Donovan, S.M.; Lee, S.Y. Mealtime Behaviors and Food Consumption of Perceived Picky and Nonpicky Eaters through Home Use Test. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, S2523–S2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, P.; Hodgson, M.I. Trastornos alimentarios del lactante y preescolar. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 2011, 82, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, D.; Nguyen, D.; Głabska, D. Food Neophobia and Consumer Choices within Vietnamese Menu in a Polish Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolstenholme, H.; Heary, C.; Kelly, C. Fussy eating behaviours: Response patterns in families of school-aged children. Appetite 2019, 136, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trofholz, A.C.; Schulte, A.K.; Berge, J.M. How parents describe picky eating and its impact on family meals: A qualitative analysis. Appetite 2017, 110, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boquin, M.; Moskowitz, H.R.; Donovan, S.M.; Lee, S.Y. Defining perceptions of picky eating obtained through focus groups and conjoint analysis. J. Sens. Stud. 2014, 29, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.N.; Tapper, K. Murphy S Feeding goals sought by mothers of 3-5-year-old children. Brit. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predieri, S.; Sinesio, F.; Monteleone, E.; Spinelli, S.; Cianciabella, M.; Daniele, G.M.; Dinnella, C.; Gasperi, F.; Endrizzi, I.; Torri, L.; et al. Gender, age, geographical area, food neophobia and their relationships with the adherence to the mediterranean diet: New insights from a large population cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A. Taste preferences and food intake. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1997, 17, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklaus, S.; Issanchou, S. Understanding Consumers of Food Products. In Children and Food Choice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 329–358. [Google Scholar]

- Werthmann, J.; Jansen, A.; Havermans, R.; Nederkoorn, C.; Kremers, S.; Roefs, A. Bits and pieces. Food texture influences food acceptance in young children. Appetite 2015, 84, 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira Torresa, T.; Gomes, D.R.; Mattosa, M.P. Factors associated with food neophobia in children: Systematic review. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2021, 39, e2020089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.D.; Donovan, S.M.; Lee, S.-Y. Considering Nature and Nurture in the Etiology and Prevention of Picky Eating: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerzner, B.; Milano, K.; MacLean, W.C.; Berall, G.; Stuart, S.; Chatoor, I. A Practical Approach to Classifying and Managing Feeding Difficulties. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatoor, I. Eating Disorders in Infancy and Early Childhood. The Oxford Handbook of Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders: Developmental Perspectives. Available online: https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199744459.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199744459-e-012 (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Taylor, C.M.; Wernimont, S.M.; Northstone, K.; Emmett, P.M. Picky/fussy eating in children: Review of definitions, assessment, prevalence and dietary intakes. Appetite 2015, 95, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascola, A.J.; Bryson, S.W.; Agras, W.S. Picky eating during childhood: A longitudinal study to age 11 years. Eat. Behav. 2010, 11, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Horst, K. Overcoming picky eating. Eating enjoyment as a central aspect of children’s eating behaviors. Appetite 2012, 58, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Horst, K.; Eldridge, A.; Deming, D.; Reidy, K. Caregivers’ perceptions about picky eating: Associations with texture acceptance and food intake. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 379.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, T.M.; Staples, P.A.; Gibson, E.L.; Halford, J.C. Food neophobia and ‘picky/fussy’ eating in children: A review. Appetite 2008, 50, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafstad, G.S.; Abebe, D.S.; Torgersen, L.; von Soest, T. Picky eating in preschool children: The predictive role of the child’s temperament and mother’s negative affectivity. Eat. Behav. 2013, 14, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jani Mehta, R.; Mallan, K.M.; Mihrshahi, S.; Mandalika, S.; Daniels, L.A. An exploratory study of associations between Australian-Indian mothers’ use of controlling feeding practices, concerns and perceptions of children’s weight and children’s picky eating. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 71, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orun, E.; Erdil, Z.; Cetinkaya, S.; Tufan, N.; Yalcin, S.S. Problematic eating behaviour in Turkish children aged 12e72 months: Characteristics of mothers and children. Central Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 20, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroshko, I.; Brennan, L. Maternal controlling feeding behaviours and child eating in preschool-aged children. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 70, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, A.T.; Lee, Y.; Birch, L.L. Predictors and consequences of food neophobia and pickiness in young girls. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 103, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, J.E.; Kim, J.; Mathai, R.A.; Tea, S.K.R. Associations of infant feeding practices and picky eating behaviors of preschool children. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel, J.E.; Reilly, E.E.; Luo, T.J.; Kaye, W.H. Conceptualizing the role of disgust in avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: Implications for the etiology and treatment of selective eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozioł-Kozakowska, A.; Piórecka, B. Food neophobia its determinants and health consequences. Stand. Med. Pediatr. 2013, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, R.A.; Raudenbush, B. Individual differences in approach to novelty: The case of human food neophobia. In Viewing Psychology as a Whole: The Integrative Science of William N. Dember; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- Knaapila, A.; Tuorila, H.; Silventoinen, K.; Keskitalo, K.; Kallela, M.; Wessman, M.; Peltonen, L.; Cherkas, L.F.; Spector, T.D.; Perola, M. Food neophobia shows heritable variation in humans. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 91, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmett, P.M.; Hays, N.; Taylor, C.M. Antecedents of picky eating behaviour in young children. Appetite 2018, 130, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcigli, G.A.; Couch, S.C.; Gribble, L.S.; Pabst, S.M.; Frank, R. Food Neophobia in Childhood Affects Dietary Variety. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2000, 100, 1474–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlow, C.S.; Forestell, C.A. The effect of parental food neophobia on children’s fruit and vegetable consumption: A serial mediation model. Appetite 2022, 172, 105942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finistrella, V.; Gianni, N.; Fintini, D.; Menghini, D.; Amendola, S.; Donini, L.M.; Manco, M. Neophobia, sensory experience and child’s schemata contribute to food choices. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2024, 29, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Welch, V. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 6.5. The Cochrane Trainng. 2024. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. Systematic Reviews CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. University of York: York, UK, 2009. Available online: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Text Revision (DSM-5-TR); American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI 2024. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 5 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Sterne, J.A.C. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial [last updated October 2019]. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Cochrane: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-08 (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Pereson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality If Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetherill, M.S.; Williams, M.B.; Reese, J.; Taniguchi, T.; Sisson, S.B.; Malek-Lasater, A.D.; Love, C.V.; Jernigan, V.B.B. Methods for Assessing Willingness to Try and Vegetable Consumption among Children in Indigenous Early Childcare Settings: The FRESH Study. Nutrients 2021, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jani, R.; Byrne, R.; Love, P.; Agarwal, C.; Peng, F.; Yew, Y.W.; Panagiotakos, D.; Naumovski, N. The Environmental and Bitter Taste Endophenotype Determinants of Picky Eating in Australian School-Aged Children 7–12 years—A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.L.; Moding, K.J.; Maloney, K.; Bellows, L.L. Development of the Trying New Foods Scale: A preschooler self-assessment of willingness to try new foods. Appetite 2018, 128, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damsbo-Svendsen, M.; Frøst, M.B.; Olsen, A. Development of novel tools to measure food neophobia in children. Appetite 2017, 113, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinsbekk, S.; Sveen, T.H.; Fildes, A.; Llewellyn, C.; Wichstrøm, L. Screening for pickiness—A validation study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollar, D.; Paxton-Aiken, A.; Fleming, P. Exploratory validation of the Fruit and Vegetable Neophobia Instrument among third- to fifth-grade students. Appetite 2013, 60, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, B.; Rigal, N.; Boireau-Ducept, N.; Mallet, P.; Meyer, T. Measuring willingness to try new foods: A self-report questionnaire for French-speaking children. Appetite 2008, 50, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, R.; Pliner, P. The Food Situations Questionnaire: A measure of children’s willingness to try novel foods in stimulating and non-stimulating situations. Appetite 2000, 35, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.R.; Steer, C.D.; Rogers, I.S.; Emmett, P.M. Influences on child fruit and vegetable intake: Sociodemographic, parental and child factors in a longitudinal cohort study. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereboom, J.; Thijs, C.; Eussen, S.; Mommers, M.; Gubbels, J.S. Association of picky eating around age 4 with dietary intake and weight status in early adulthood: A 14-year follow-up based on the KOALA birth cohort study. Appetite 2023, 188, 106762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Andrade Previato, H.D.R.; Behrens, J.H. Taste-related factors and food neophobia: Are they associated with nutritional status and teenagers’ food choices? Nutrition 2017, 42, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białek-Dratwa, A.; Kowalski, O. Prevalence of Feeding Problems in Children and Associated Factors-A Cross-Sectional Study among Polish Children Aged 2–7 Years. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantis, D.V.; Emmett, P.M.; Taylor, C.M. Effect of being a persistent picky eater on feeding difficulties in school-aged children. Appetite 2023, 183, 106483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viljakainen, H.T.; Figueiredo, R.A.O.; Rounge, T.B.; Weiderpass, E. Picky eating—A risk factor for underweight in Finnish preadolescents. Appetite 2019, 133, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grulichova, M.; Kuruczova, D.; Svancara, J.; Pikhart, H.; Bienertova-Vasku, J. Association of Picky Eating with Weight and Height-The European Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood (ELSPAC-CZ). Nutrients 2022, 14, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, A.H.; Pick, S.; Lev-Ari, L.; Bachner-Melman, R. A longitudinal study of maternal feeding and children’s picky eating. Appetite 2020, 154, 104804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, H.C.; Lu, J.J.; Yang, C.Y.; Yeh, P.J.; Chu, S.M. Serum trace element levels and their correlation with picky eating behavior, development, and physical activity in early childhood. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, C.; McCaffery, H.; Miller, A.L.; Kaciroti, N.; Lumeng, J.C.; Pesch, M.H. Trajectories of picky eating in low-income US children. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20192018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandvik, P.; Ek, A.; Somaraki, M.; Hammar, U.; Eli, K.; Nowicka, P. Picky eating in Swedish preschoolers of different weight status: Application of two new screening cut-offs. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinsbekk, S.; Bonneville-Roussy, A.; Fildes, A.; Llewellyn, C.H.; Wichstrøm, L. Child and parent predictors of picky eating from preschool to school age. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, H.C.; Chang, H.L. Picky Eating Behaviors Linked to Inappropriate Caregiver–Child Interaction, Caregiver Intervention, and Impaired General Development in Children. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2017, 58, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Machado, B.C.; Dias, P.; Lima, V.S.; Campos, J.; Gonçalves, S. Prevalence and correlates of picky eating in preschool-aged children: A population-based study. Eat. Behav. 2016, 22, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Lee, E.; Ning, K.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, D.; Gao, H.; Yang, B.; Bai, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y. Prevalence of picky eating behaviour in Chinese school-age children and associations with anthropometric parameters and intelligence quotient. A cross-sectional study. Appetite 2015, 91, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Zhao, A.; Cai, L.; Yang, B.; Szeto, I.M.Y.; Ma, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P. Growth and development in Chinese pre-schoolers with picky eating behaviour: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Tadeo, A.; Patiño-Villena, B.; González Martínez-La Cuesta, E.; Urquídez-Romero, R.; Ros Berruezo, G. Food neophobia, Mediterranean diet adherence and acceptance of healthy foods prepared in gastronomic workshops by Spanish students. Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 35, 642–649. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Tadeo, A.; Patiño Villena, B.; Urquidez-Romero, R.; Vidaña-Gaytán, M.E.; Periago Caston, M.J.; Ros Berruezo, G.; González Martínez-Lacuesta, E. Neofobia alimentaria: Impacto sobre los hábitos alimentarios y aceptación de alimentos saludables en usuarios de comedores escolares. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 31, 260–268. [Google Scholar]

- Kozioł-Kozakowska, A.; Piórecka, B.; Schlegel-Zawadzka, M. Prevalence of food neophobia in pre-school children from southern Poland and its association with eating habits, dietary intake and anthropometric parameters: A cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, A.T.; Fiorito, L.; Lee, Y.; Birch, L.L. Parental pressure, dietary patterns, and weight status among girls who are “picky eaters”. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sdravou, K.; Fotoulaki, M.; Emmanouilidou-Fotoulaki, E.; Andreuoulakis, E.; Makris, G.; Sotiriadou, F.; Printza, A. Feeding Problems in Typically Developing Young Children, a Population-Based Study. Children 2021, 8, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona Cano, S.; Hoek, H.W.; Van Hoeken, D.; de Barse, L.M.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Verhulst, F.S.; Tiemetier, H. Behavioral outcomes of picky eating in childhood: A prospective study in the general population. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D.; Herle, M.; Fildes, A.; Cooke, L.; Steinsbekk, S.; Llewellyn, C.H. Food fussiness and food neophobia share a common etiology in early childhood. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2017, 58, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, L.J.; Haworth, C.M.; Wardle, J. Genetic and environmental influences on children’s food neophobia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faith, M.S.; Heo, M.; Keller, K.L.; Pietrobelli, A. Child food neophobia is heritable, associated with less compliant eating, and moderates familial resemblance for BMI. Obesity 2013, 21, 1650–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahill, S.; Kennedy, A.; Walton, J.; McNulty, B.A.; Kearney, J. The factors associated with food fussiness in Irish school-aged children. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 22, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- on behalf of the EDEN mother-child cohort Study Group; Yuan, W.L.; Rigal, N.; Monnery-Patris, S.; Chabanet, C.; Forhan, A.; Charles, M.-A.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B. Early determinants of food liking among 5y-old children: A longitudinal study from the EDEN mother-child cohort. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, S.; DeJesus, J.M. Can children report on their own picky eating? Similarities and differences with parent report. Appetite. 2022, 177, 106155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, A.R.; Terhorst, L.; Magnan, K.; Bogen, D.L. Describing and Predicting Feeding Problems During the First 2 Years Within an Urban Pediatric Primary Care Center. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) 2023, 62, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.L.; Perrin, E.M.; Peterson, K.E.; Herb, H.E.B.; Horodynski, M.A.; Contreras, D.; Miller, A.L.; Appugliese, D.P.; Ball, S.C.; Lumeng, J.C. Association of Picky Eating with Weight Status and Dietary Quality Among Low-Income Preschoolers. Acad. Pediatr. 2018, 18, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roßbach, S.; Foterek, K.; Schmidt, I.; Hilbig, A.; Alexy, U. Food neophobia in German adolescents: Determinants and association with dietary habits. Appetite 2016, 101, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Davies, P.L.; Boles, R.E.; Gavin, W.J.; Bellows, L.L. Young children’s food neophobia characteristics and sensory behaviors are related to their food intake. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2610–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, D.; Głąbska, D.; Lange, E.; Jezewska-Zychowicz, M. A Polish Study on the influence of food neophobia in children (10-12 years old) on the intake of vegetables and fruits. Nutrients 2017, 9, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutbi, H.A. Picky eating in school-aged children: Sociodemographic determinants and the associations with dietary intake. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, J.; Verbeken, S.; Goossens, L. Examining the whole plate: The role of the family context in the understanding of children’s food refusal behaviors. Eat. Behav. 2024, 52, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Doong, J.Y.; Tu, M.J.; Huang, S.C. Impact of Dietary Coparenting and Parenting Strategies on Picky Eating Behaviors in Young Children. Nutrients 2024, 16, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaarno, J.; Niinikoski, H.; Kaljonen, A.; Aromaa, M.; Lagström, H. Mothers’ restrictive eating and food neophobia and fathers’ dietary quality are associated with breast-feeding duration and introduction of solid foods: The STEPS study. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmer Specht, I.; Friis Rohde, J.; Julie Olsen, N.; Lilienthal Heitmann, B. Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding May be Related to Eating Behaviour and Dietary Intake in Obesity Prone Normal Weight Young Children. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200388. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, L.K.; Jansen, E.; Mallan, K.; Magarey, A.M.; Daniels, L. Poor dietary patterns at 1–5 years of age are related to food neophobia and breastfeeding duration but not age of introduction to solids in a relatively advantaged sample. Eat. Behav. 2018, 31, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolstenholme, H.; Kelly, C.; Heary, C. “Fussy eating” and feeding dynamics: School children’s perceptions, experiences, and strategies. Appetite 2022, 173, 106000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilman, L.B.; Meredith, P.J.; Southon, N.; Kennedy-Behr, A.; Frakking, T.; Swanepoel, L.; Verdonck, M. A qualitative inquiry of parents of extremely picky eaters: Experiences, strategies and future directions. Appetite 2023, 190, 107022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumeng, J.C.; Miller, A.L.; Appugliese, D.; Rosenblum, K.; Kaciroti, N. Picky eating, pressuring feeding, and growth in toddlers. Appetite 2018, 123, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moding, K.J.; Stifter, C.A. Temperamental approach/withdrawal and food neophobia in early childhood: Concurrent and longitudinal associations. Appetite 2016, 107, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, S.; Oflu, A.; Akturfan, M.; Yalcin, S.S. Characteristics of picky eater children in Turkey: A cross-sectional study. Bmc Pediatr. 2022, 22, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, J.; Raciti, M.M. Primary caregivers of young children are unaware of food neophobia and food preference development. Heal. Promot. J. Aust. 2016, 27, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, H.; Palfreyman, Z.; Morizet, D. Sensory evaluation of a novel vegetable in school age children. Appetite 2016, 100, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moding, K.J.; Stifter, C.A. Stability of food neophobia from infancy through early childhood. Appetite 2016, 97, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.J.; Mallan, K.M.; Byrne, R.; Magarey, A.; Daniels, L.A. Toddlers’ food preferences. The impact of novel food exposure, maternal preferences and food neophobia. Appetite 2012, 59, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.C.; Holub, S.C. Maternal feeding practices associated with food neophobia. Appetite 2012, 59, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Carnell, S.; Cooke, L. Parental control over feeding and children’s fruit and vegetable intake: How are they related? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poelman, A.A.M.; Cochet-Broch, M.; Cox, D.N.; Vogrig, D. Vegetable Education Program Positively Affects Factors Associated with Vegetable Consumption Among Australian Primary (Elementary) Schoolchildren. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 492–497.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassells, E.L.; Magarey, A.M.; Daniels, L.A.; Mallan, K.M. The influence of maternal infant feeding practices and beliefs on the expression of food neophobia in toddlers. Appetite 2014, 82, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, L.J.; Wardle, J.; Gibson, E.L.; Sapochnik, M.; Sheiham, A.; Lawson, M. Demographic, familial and trait predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption by pre-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2003, 7, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, C.G.; Worsley, A. Why do they like that? And can I do anything about it? The nature and correlates of parents’ attributions and self-efficacy beliefs about preschool children’s food preferences. Appetite 2013, 66, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, A.A.; Appugliese, D.P.; Miller, A.L.; Lumeng, J.C.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Pesch, M.H. Maternal prompting types and child vegetable intake: Exploring the moderating role of picky eating. Appetite 2019, 146, 104518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, N.C.; Musaad, S.M.; Lee, S.-Y.; Donovan, S.M. Home feeding environment and picky eating behavior in preschool-aged children: A prospective analysis. Eat. Behav. 2018, 30, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, C.; Schmitz, G.; Stewart Agras, W. Is picky eating an eating disorder? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2008, 41, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarman, M.; Ogden, J.; Inskip, H.; Lawrence, W.; Baird, J.; Cooper, C.; Robinson, S.; Barker, M. How do mothers manage their preschool children’s eating habits and does this change as children grow older? A longitudinal analysis. Appetite 2015, 95, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharner, A.; Jansen, P.W.; Kiefte-De Jong, J.C.; Moll, H.A.; Van Der Ende, J.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Hofman, A.; Tiemeier, H.; Franco, O.H. Toward an operative diagnosis of fussy/picky eating: A latent profile approach in a population-based cohort. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, H.A.; Staton, S.; Morawska, A.; Gallegos, D.; Oakes, C.; Thorpe, K. A comparison of maternal feeding responses to child fussy eating in low-income food secure and food insecure households. Appetite 2019, 137, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Campo, C.; Bouzas, C.; Monserrat-Mesquida, M.; Tur, J.A. Assessing food preferences and neophobias among Spanish adolescents from Castilla–La Mancha. Foods 2023, 12, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnery-Patris, S.; Wagner, S.; Rigal, N.; Schwartz, C.; Chabanet, C.; Issanchou, S.; Nicklaus, S. Smell differential reactivity, but not taste differential reactivity, is related to food neophobia in toddlers. Appetite 2015, 95, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, H.; Blissett, J. Fruit and vegetable consumption in children and their mothers. Moderating effects of child sensory sensitivity. Appetite 2009, 52, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, H.; Thakker, D. Enjoyment of Tactile Play Is Associated with Lower Food Neophobia in Preschool Children. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.M.; Roux, S.; Naidoo, N.T.; Venter, D.J.L. Food choices of tactile defensive children. Nutrition 2005, 21, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maratos, F.A.; Staples, P. Attentional biases towards familiar and unfamiliar foods in children. The role of food neophobia. Appetite 2015, 91, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monneuse, M.O.; Rigal, N.; Frelut, M.L.; Hladik, C.M.; Simmen, B.; Pasquet, P. Taste acuity of obese adolescents and changes in food neophobia and food preferences during a weight reduction session. Appetite 2008, 50, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berger, P.K.; Hohman, E.E.; Marini, M.E.; Savage, J.S.; Birch, L.L. Girls’ picky eating in childhood is associated with normal weight status from ages 5 to 15 y. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1577–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, P.; Ek, A.; Eli, K.; Somaraki, M.; Bottai, M.; Nowicka, P. Picky eating in an obesity intervention for preschool-aged children—What role does it plays, and does the measurement instrument matter? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, E.E.; Roefs, A.; Kremers, S.P.; Jansen, A.; Gubbels, J.S.; Sleddens, E.F.; Thijs, C. Picky eating and child weight status development: A longitudinal study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 29, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekstein, S.; Laniado, D.; Glick, B. Does picky eating affect weight-for-length measurements in young children? Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) 2010, 49, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.M.; Steer, C.D.; Hays, N.P.; Emmett, P.M. Growth and body composition in children who are picky eaters: A longitudinal view. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.L.; Perrin, E.M. Defining picky eating and its relationship to feeding behaviors and weight status. J. Behav. Med. 2020, 43, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaapila, A.J.; A Sandell, M.; Vaarno, J.; Hoppu, U.; Puolimatka, T.; Kaljonen, A.; Lagström, H. Food neophobia associates with lower dietary quality and higher BMI in Finnish adults. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2161–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finistrella, V.; Manco, M.; Ferrara, A.; Rustico, C.; Presaghi, F.; Morino, G. Cross-sectional exploration of maternal reports of food neophobia and pickiness in preschooler-mother dyads. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2012, 31, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; van der Horst, K.; Edelson-Fries, L.R.; Yu, K.; You, L.; Zhang, Y.; Vinyes-Pares, G.; Wang, P.; Ma, D.; Yang, X.; et al. Perceptions of food intake and weight status among parents of picky eating infants and toddlers in China: A cross-sectional study. Appetite 2017, 108, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, C.; Agras, W.S.; Bryson, S.; Hammer, L.D. Behavioral validation, precursors, and concomitants of picky eating in childhood. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.A.; Mallan, K.M.; Koo, J.; Mauch, C.E.; Daniels, L.A.; Magarey, A.M. Food neophobia and its association with diet quality and weight in children aged 24 months: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Silva, C.; Oliveira, A. Food neophobia and its association with food preferences and dietary intake of adults. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Horst, K.; Deming, D.M.; Lesniauskas, R.; Carr, B.T.; Reidy, K.C. Picky eating: Associations with child eating characteristics and food intake. Appetite 2016, 103, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, J.; Lan, H.; Szeto, I.M.; Wang, P. Consumption of Added Sugar among Chinese Toddlers and Its Association with Picky Eating and Daily Screen Time. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.M.; Northstone, K.; Wernimont, S.M.; Emmett, P.M. Macro-and micronutrient intakes in picky eaters: A cause for concern? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, K.; Tithecott, C.; Neilson, L.; Seabrook, J.A.; Dworatzek, P. Picky Eating Is Associated with Lower Nutrient Intakes from Children’s Home-Packed School Lunches. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, L.; Farmer, A.P.; Girard, M.; Peterson, K. Preschool children’s eating behaviours are related to dietary adequacy and body weight. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, D.; Głąbska, D.; Mellová, B.; Zadka, K.; Żywczyk, K.; Gutkowska, K. Influence of food neophobia level on fruit and vegetable intake and its association with urban area of residence and physical activity in a nationwide case-control study of polish adolescents. Nutrients 2018, 10, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wild, V.W.; Jager, G.; Olsen, A.; Costarelli, V.; Boer, E.; Zeinstra, G.G. Breast-feeding duration and child eating characteristics in relation to later vegetable intake in 2-6-year-old children in ten studies throughout Europe. Clay Miner. 2018, 21, 2320–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonen, S.; Oerlemans, P.; Tuorila, H. Familiarity with and affective responses to foods in 8-11-year-old children. The role of food neophobia and parental education. Appetite 2012, 58, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.G.; Worsley, A. A Population-based Study of Preschoolers’ Food Neophobia and Its Associations with Food Preferences. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2008, 40, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, K.; Rönkä, A.; Hujo, M.; Lyytikäinen, A.; Nuutinen, O. Sensory-based food education in early childhood education and care, willingness to choose and eat fruit and vegetables, and the moderating role of maternal education and food neophobia. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 2443–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuorila, H.; Mustonen, S. Reluctant trying of an unfamiliar food induces negative affection for the food. Appetite 2010, 54, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, M.; Nakamura, K.; Tamai, Y.; Wada, K.; Sahashi, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Ohtsuchi, S.; Ando, K.; Nagata, C. Relationship of intake of plant-based foods with 6- n -propylthiouracil sensitivity and food neophobia in Japanese preschool children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 66, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, A.; Rodríguez, D.V.; Ochoa, C.; Pedrón, C.; Sánchez, J. Psychological and social impact on parents of children with feeding difficulties. An. Pediatría (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 97, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, K.; Markides, B.R.; Barrett, N.; Laws, R. Fussy eating in toddlers: A content analysis of parents’ online support seeking. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2021, 17, e13171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiz, E.; Balluerka, N. Trait anxiety and self-concept among children and adolescents with food neophobia. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomkvist, E.A.M.; Helland, S.H.; Hillesund, E.R.; Øverby, N.C. A cluster randomized web-based intervention trial to reduce food neophobia and promote healthy diets among one-year-old children in kindergarten: Study protocol. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allirot, X.; da Quinta, N.; Chokupermal, K.; Urdaneta, E. Involving children in cooking activities: A potential strategy for directing food choices toward novel foods containing vegetables. Appetite 2016, 103, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wild, V.W.T.; de Graaf, C.; Jager, G. Use of Different Vegetable Products to Increase Preschool-Aged Children’s Preference for and Intake of a Target Vegetable: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureati, M.; Bergamaschi, V.; Pagliarini, E. School-based intervention with children. Peer-modeling, reward and repeated exposure reduce food neophobia and increase liking of fruits and vegetables. Appetite 2014, 83, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverdy, C.; Chesnel, F.; Schlich, P.; Köster, E.P.; Lange, C. Effect of sensory education on willingness to taste novel food in children. Appetite 2008, 51, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, C.; Lafraire, J.; Picard, D. Visual exposure and categorization performance positively influence 3- to 6-year-old children’s willingness to taste unfamiliar vegetables. Appetite 2018, 120, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, H.; Sealy, A. Play with your food! Sensory play is associated with tasting of fruits and vegetables in preschool children. Appetite 2017, 113, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, L.; Bryant-Waugh, R.; Mandy, W.; Solmi, F. Investigating the prevalence and risk factors of picky eating in a birth cohort study. Eat. Behav. 2023, 50, 101780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searle, B.E.; Harris, H.A.; Thorpe, K.; Jansen, E. What children bring to the table: The association of temperament and child fussy eating with maternal and paternal mealtime structure. Appetite 2020, 151, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickard, A.; Thibaut, J.; Philippe, K.; Lafraire, J. Journal of Experimental Child Poor conceptual knowledge in the food domain and food rejection dispositions in 3- to 7-year-old children. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 2023, 226, 105546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]