Valorization of Tomato Surplus and Waste Fractions: A Case Study Using Norway, Belgium, Poland, and Turkey as Examples

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Tomato Production in Norway, Belgium, Poland and Turkey

2.1. Norway

2.2. Belgium

2.3. Poland

2.4. Turkey

3. The Significance of Lycopene in Tomato

3.1. Lycopene Content in Tomato

3.2. Effect of Processing

4. Utilization of Tomato Side Streams and By-Products

4.1. Fresh Tomato

4.2. Processing

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Total Overview 2004–2014; Fresh Fruit, Berries, Vegetables, and Potatoes; Opplysningskontoret for Frukt og Grønt: OSLO, Norway, 2015.

- Tomato Production and Consumption by Country. Available online: Http://Chartsbin.Com/View/32687 (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- World Health Organization. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Report of a joint FAO/WHO expert consultation. In WHO Technical Report Series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2002; Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kips, L.; Van Droogenbroeck, B. Valorisation of Vegetable and Fruit by-Products and Waste Fractions: Bottlenecks and Opportunities; Instituut voor Landbouw, Visserij-en Voedingsonderzoek: Melle, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vold, M.; Møller, H.; Hanssen, O.J.; Langvik, T.Å. Value-Chain-Anchored Expertise in Packaging/Distribution of Food Products; Stiftelsen Østfoldforskning: Fredrikstad, Norway, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyk, S.J.; Gama, R.; Morrison, D.; Swart, S.; Pletschke, B.I. Food processing waste: Problems, current management and prospects for utilisation of the lignocellulose component through enzyme synergistic degradation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljøgartneriet. Available online: http://miljogartneriet.no/hjem (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- Verheul, M.; Maessen, H.; Grimstad, O.S. Optimizing a year round cultivation system of tomato under artificial light. Acta Hortic. 2012, 956, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgian Tomatoes’ Strong Focus on Exports. Eurofresh. 2016. Available online: https://www.eurofresh-distribution.com/news/belgian-tomatoes%E2%80%99-strong-focus-exports (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- Lava. Available online: https://www.lava.be/ (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- Gellynck, X.; Lambrecht, E.; de Pelsmaeker, S.; Vandenhaute, H. The Impact of Cosmetic Quality Standards on Food Loss—Case Study of the Flemish Fruit and Vegetable Sector; Department of Agriculture and Fisheries: Flandern, Belgium, 2017.

- Statistics Poland. Statistical Yearbook of Agriculture-2018; Rozkrut, D., Ed.; Agricultural Department: Warsaw, Poland, 2018.

- Greenhouse Tomatoes: A Greater Role on the Polish Scene. Eurofresh. 2016. Available online: https://www.eurofresh-distribution.com/news/greenhouse-tomatoes-greater-role-polish-scene (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- Sarisacli, E. Tomato Paste; The Prime Ministry Foreign Trade Undersecretariat of the Turkey Republic: Ankara, Turkey, 2007.

- TUIK. Crop Products Balance Sheet, Vegetables. 2000/01–2017/18. Available online: www.tuik.gov.tr (accessed on 29 May 2019).

- Tatlidil, F.; Kiral, T.; Gunes, A.; Demir, K.; Erdemir, G.; Fidan, H.; Demirci, F.; Erdogan, C.; Akturk, D. Economic Analysis of Crop Losses during Pre-Harvest and Harvest Periods in Tomato Production in the Ayas and Nallihan Districts of the Ankara Province; TUBITAK-TARP: Ankara, Turkey, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Celikel, F. Maintaining the postharvest quality of organic horticultural crops. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 6, 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Buyukbay, O.E.; Uzunoz, M.; Bal, H.S.G. Post-Harvest Losses in Tomato and Fresh Bean Production in Tokat Province of Turkey. Sci. Res. Essays 2011, 6, 1656–1666. [Google Scholar]

- Simonne, H.A.; Behe, B.K.; Marshall, M.M. Consumers Prefer Low-Priced and High-Lycopene-Content Fresh-Market Tomatoes. HortTechnology 2006, 16, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadupin, T.G.; Osadola, O.T.; Atinmo, T. Lycopene Content of Selected Tomato Based Products, Fruits and Vegetables Consumed in South Western Nigeria. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2012, 15, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.; Schwartz, S.J. Lycopene: Chemical and Biological Properties. Food Technol. 1999, 53, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kin-Weng, K.W.; Khoo, H.E.; Prasad, K.N.; Ismail, A.; Tan, C.P.; Rajab, N.F. Revealing the Power of the Natural Red Pigment Lycopene. Molecules 2010, 15, 959–987. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Agarwal, S.; Rao, A.V. Tomato Lycopene and Low Density Lipoprotein Oxidation: A Human Dietary Intervention Study. Lipids 1998, 33, 981–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Schwartz, S.J. Lycopene Stability During Food Processing. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1998, 218, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, N.E.; Kopec, R.E.; Schwartz, S.J.; Harris, G.K. An Update on the Health Effects of Tomato Lycopene. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, W.; Sies, H. Uptake of Lycopene and Its Geometrical-Isomers Is Greater from Heat-Processed Than from Unprocessed Tomato Juice in Humans. J. Nutr. 1992, 122, 2161–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooperstone, L.J.; Ralston, R.A.; Riedl, K.M.; Haufe, T.C.; Schweiggert, R.M.; King, S.A.; Timmers, C.D.; Francis, D.M.; Lesinski, G.B.; Schwartz, S.J. Enhanced Bioavailability of Lycopene When Consumed as Cis-Isomers from Tangerine Compared to Red Tomato Juice, a Randomized, Cross-over Clinical Trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaioannou, H.E.; Liakopoulou-Kyriakides, M.; Karabelas, A.J. Natural Origin Lycopene and Its Green Downstream Processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 686–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperstone, L.J.; Francis, D.M.; Schwartz, S.J. Thermal Processing Differentially Affects Lycopene and Other Carotenoids in Cis-Lycopene Containing, Tangerine Tomatoes. Food Chem. 2016, 210, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziani, G.; Pernice, R.; Lanzuise, S.; Vitaglione, P.; Anese, M.; Fogliano, V. Effect of Peeling and Heating on Carotenoid Content and Antioxidant Activity of Tomato and Tomato-Virgin Olive Oil Systems. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2003, 216, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adalid, M.A.; Rosello, S.; Nuez, F. Evaluation and Selection of Tomato Accessions (Solanum Section Lycopersicon) for Content of Lycopene, Beta-Carotene and Ascorbic Acid. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, W.J.; Lincoln, R.E. Lycopersicon Selections Containing a High Content of Carotenes and Colorless Polyenes. II. The Mechanism of Carotene Biosynthesis. Arch. Biochem. 1950, 27, 390–403. [Google Scholar]

- Zanfini, A.; Dreassi, E.; la Rosa, C.; D’Addario, C.; Corti, P. Quantitative Variations of the Main Carotenoids in Italian Tomatoes in Relation to Geographic Location, Harvest Time, Varieties and Ripening Stage. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2007, 19, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Aherne, S.A.; Jiwan, M.A.; Daly, T.; O’Brien, N.M. Geographical Location has Greater Impact on Carotenoid Content and Bioaccessibility from Tomatoes than Variety. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2009, 64, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, S.; Pék, Z.; Barna, É.; Lugasi, A.; Helyes, L. Lycopene content and colour of ripening tomatoes as affected by environmental conditions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Sharma, R.; Wani, A.A.; Gill, B.S.; Sogi, D. Physicochemical Changes in Seven Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) Cultivars During Ripening. Int. J. Food Prop. 2006, 9, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Howard, F.D.; Luh, B.S.; Leonard, S.J. Effect of Ripeness and Harvest Dates on the Quality and Composition of Fresh Canning Tomatoes. Proc. Am. Soc. Horticult. Sci. 1960, 76, 560–567. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.T.; Jadhav, S.J.; Salunkhe, O.K. Effects of Sub-atmospheric pressure storage on ripening of tomato fruits. J. Food Sci. 1972, 37, 952–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, G.; Davis, J.; Dezman, D. Rapid Extraction of Lycopene and B-Carotene from Reconstituted Tomato Paste and Pink Grapefruit Homogenates. J. Food Sci. 1990, 55, 1460–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushita, A.A.; Daood, H.G.; Biacs, P.A. Change in Carotenoids and Antioxidant Vitamins in Tomato as a Function of Varietal and Technological Factors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 2075–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helyes, L.; Pék, Z.; Brandt, S.; Lugasi, A. Analysis of Antioxidant Compounds and Hydroxymethylfurfural in Processing Tomato Cultivars. HortTechnology 2006, 16, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pék, Z.; Szuvandzsiev, P.; Daood, H.; Neményi, A.; Helyes, L. Effect of irrigation on yield parameters and antioxidant profiles of processing cherry tomato. Open Life Sci. 2014, 9, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gómez, R.; Costa, J.; Amo, M.; Alvarruiz, A.; Picazo, M.; Pardo, J.E. Physicochemical and Colorimetric Evaluation of Local Varieties of Tomato Grown in SE Spain. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2001, 81, 1101–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Cebrino, F.; Lozano, M.; Ayuso, M.C.; Bernalte, M.J.; Vidal-Aragon, M.C.; González-Gómez, D. Characterization of traditional tomato varieties grown in organic conditions. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 9, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lahoz, I.; Leiva-Brondo, M.; Martí, R.; Macua, J.I.; Campillo, C.; Roselló, S.; Cebolla-Cornejo, J. Influence of high lycopene varieties and organic farming on the production and quality of processing tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 204, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lenucci, S.M.; Caccioppola, A.; Durante, M.; Serrone, L.; de Caroli, M.; Piro, G.; Dalessandro, G. Carotenoid Content During Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Fruit Ripening in Traditional and High-Pigment Cultivars. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2009, 21, 461–472. [Google Scholar]

- Frusciante, L.; Carli, P.; Ercolano, M.R.; Pernice, R.; Di Matteo, A.; Fogliano, V.; Pellegrini, N. Antioxidant nutritional quality of tomato. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbudak, B. Effects of harvest time on the quality attributes of processed and non-processed tomato varieties. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbudak, B. Comparison of Quality Characteristics of Fresh and Processing Tomato. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2012, 10, 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Kawatra, A.; Sehgal, S. Physical-Chemical Properties and Nutritional Evaluation of Newly Developed Tomato Genotypes. Afr. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 2, 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, R.; Lee, T.-C.; Logendra, L.; Janes, H. Correlation of Lycopene Measured by HPLC with the L*, a*, b* Color Readings of a Hydroponic Tomato and the Relationship of Maturity with Color and Lycopene Content. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1697–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanelli, G.; Pagliarini, E. Antioxidant Composition of Tomato Products Typically Consumed in Italy. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2009, 21, 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Georgé, S.; Tourniaire, F.; Gautier, H.; Goupy, P.; Rock, E.; Caris-Veyrat, C. Changes in the Contents of Carotenoids, Phenolic Compounds and Vitamin C During Technical Processing and Lyophilisation of Red and Yellow Tomatoes. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.S.; LeMaguer, M. Lycopene in Tomatoes and Tomato Pulp Fraction. Ital. J. Food Sci. 1996, 8, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Muratore, G.; Licciardello, F.; Maccarone, E. Evaluation of the Chemical Quality of a New Type of Small-Sized Tomato Cultivar, the Plum Tomato (Lycopersicon lycopersicum). Ital. J. Food Sci. 2005, 17, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.; Francis, D.; Schwartz, S. Thermal isomerisation susceptibility of carotenoids in different tomato varieties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2001, 81, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, R.B.; Frank, G.C.; Nakayama, K.; Tawfik, E. Lycopene content in raw tomato varieties and tomato products. J. Foodserv. 2008, 19, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimestad, R.; Verheul, M.J. Seasonal Variations in the Level of Plant Constituents in Greenhouse Production of Cherry Tomatoes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3114–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffo, A.; La Malfa, G.; Fogliano, V.; Maiani, G.; Quaglia, G. Seasonal variations in antioxidant components of cherry tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum cv. Naomi F1). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, L.F.; Migliori, C.; Viscardi, D.; Parisi, M. Quality of Tomato Fertilized with Nitrogen and Phosphorous. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2010, 22, 186–191. [Google Scholar]

- Ilahy, R.; Tlili, I.; Riahi, A.; Sihem, R.; Ouerghi, I.; Hdider, C.; Piro, G.; Lenucci, M.S. Fractionate analysis of the phytochemical composition and antioxidant activities in advanced breeding lines of high-lycopene tomatoes. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, B.; Kaur, C.; Khurdiya, D.; Kapoor, H. Antioxidants in tomato (Lycopersium esculentum) as a function of genotype. Food Chem. 2004, 84, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, K.; Krbavčić, I.P.; Krpan, M.; Bicanic, D.; Vahčić, N. The lycopene content in pulp and peel of five fresh tomato cultivars. Acta Aliment. 2010, 39, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccheri, L.; Tuccio, L.; Mencaglia, A.A.; Mignani, A.G.; Hallmann, E.; Sikorska-Zimny, K.; Kaniszewski, S.; Verheul, M.J.; Agati, G. Directional versus total reflectance spectroscopy for the in situ determination of lycopene in tomato fruits. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 71, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

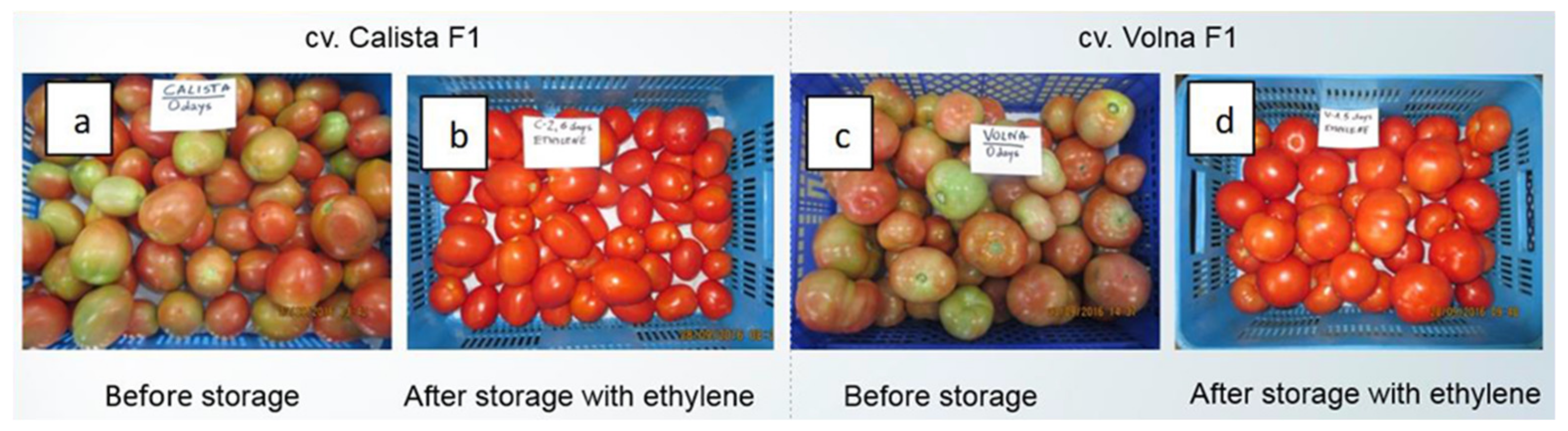

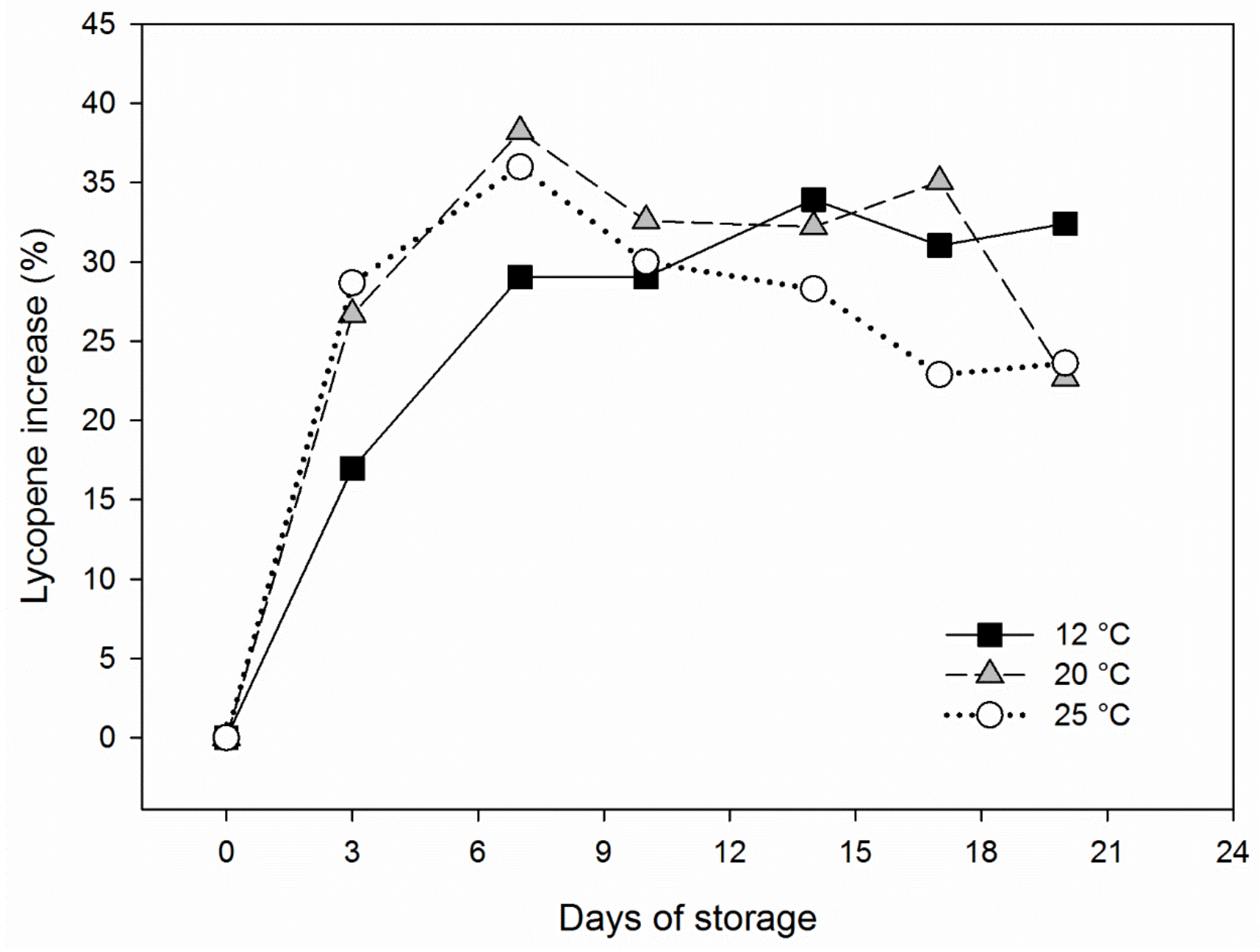

- Sikorska-Zimny, K.; Badelek, E.; Grzegorzewska, M.; Ciecierska, A.; Kowalski, A.; Kosson, R.; Tuccio, L.; Mencaglia, A.A.; Ciaccheri, L.; Mignani, A.G.; et al. Comparison of Lycopene Changes between Open-Field Processing and Fresh Market Tomatoes During Ripening and Post-Harvest Storage by Using a Non-Destructive Reflectance Sensor. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 2763–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capanoglu, E.; Beekwilder, J.; Boyacioglu, D.; De Vos, R.C.; Hall, R.D. The Effect of Industrial Food Processing on Potentially Health-Beneficial Tomato Antioxidants. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luterotti, S.; Bicanic, D.; Marković, K.; Franko, M. Carotenes in processed tomato after thermal treatment. Food Control 2015, 48, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svelander, C.A.; Tibäck, E.A.; Ahrné, L.M.; Langton, M.I.; Svanberg, U.S.; Alminger, M.A. Processing of tomato: Impact on in vitro bioaccessibility of lycopene and textural properties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1665–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seybold, C.; Fröhlich, K.; Bitsch, R.; Otto, K.; Böhm, V. Changes in Contents of Carotenoids and Vitamin E during Tomato Processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7005–7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanoni, B.; Pagliarini, E.; Giovanelli, G.; Lavelli, V. Modelling the effects of thermal sterilization on the quality of tomato puree. J. Food Eng. 2003, 56, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Sogi, D.; Wani, A.A. Degradation Kinetics of Lycopene and Visual Color in Tomato Peel Isolated from Pomace. Int. J. Food Prop. 2006, 9, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessy, H.H.; Zhang, H.W.; Zhang, L.F. A Study on Thermal Stability of Lycopene in Tomato in Water and Oil Food Systems Using Response Surface Methodology. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Shi, J.; Xue, S.J.; Ma, Y. Comparison of Lycopene Stability in Water-And Oil-Based Food Model Systems under Thermal-and Light-Irradiation Treatments. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibäck, E.A.; Svelander, C.A.; Colle, I.J.; Altskär, A.I.; Alminger, M.A.; Hendrickx, M.E.; Ahrné, L.M.; Langton, M.I. Mechanical and Thermal Pretreatments of Crushed Tomatoes: Effects on Consistency and In Vitro Accessibility of Lycopene. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, E386–E395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, C.; George, B.; Deepa, N.; Singh, B.; Kapoor, H.C. Antioxidant Status of Fresh and Processed Tomato—A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol.-Mysore 2004, 41, 479–486. [Google Scholar]

- Spigno, G.; Maggi, L.; Amendola, D.; Ramoscelli, J.; Marcello, S.; De Faveri, D.M. Bioactive Compounds in Industrial Tomato Sauce after Processing and Storage. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2014, 26, 252–260. [Google Scholar]

- Takeoka, G.R.; Dao, L.; Flessa, S.; Gillespie, D.M.; Jewell, W.T.; Huebner, B.; Bertow, D.; Ebeler, S.E. Processing Effects on Lycopene Content and Antioxidant Activity of Tomatoes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 3713–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratakos, A.C.; Delgado-Pando, G.; Linton, M.; Patterson, M.F.; Koidis, A. Industrial scale microwave processing of tomato juice using a novel continuous microwave system. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sanchez-Moreno, C.; Plaza, L.; de Ancos, B.; Cano, M.P. Impact of High-Pressure and Traditional Thermal Processing of Tomato Puree on Carotenoids, Vitamin C and Antioxidant Activity. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Plaza, L.; de Ancos, B.; Cano, M.P. Effect of Combined Treatments of High-Pressure and Natural Additives on Carotenoid Extractability and Antioxidant Activity of Tomato Puree (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2004, 219, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knockaert, G.; Pulissery, S.K.; Colle, I.; Van Buggenhout, S.; Hendrickx, M.; Van Loey, A. Lycopene degradation, isomerization and in vitro bioaccessibility in high pressure homogenized tomato puree containing oil: Effect of additional thermal and high pressure processing. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Maguer, M.; Bryan, M.; Kakuda, Y. Kinetics of lycopene degradation in tomato puree by heat and light irradiation. J. Food Process. Eng. 2003, 25, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anese, M.; Falcone, P.; Fogliano, V.; Nicoli, M.; Massini, R. Effect of Equivalent Thermal Treatments on the Color and the Antioxidant Activity of Tomato Puree. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 3442–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Balasubramaniam, V.M.; Schwartz, S.J.; Francis, D.M. Storage Stability of Lycopene in Tomato Juice Subjected to Combined Pressure–Heat Treatments. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8305–8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kips, L.; De Paepe, D.; Bernaert, N.; Van Pamel, E.; De Loose, M.; Raes, K.; Van Droogenbroeck, B. Using a novel spiral-filter press technology to biorefine horticultural by-products: The case of tomato. Part I: Process optimization and evaluation of the process impact on the antioxidative capacity. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 38, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siewert, N. Vaculiq—The System for Juice, Smoothie and Puree? Fruit Process. 2013, 2, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Løvdal, T.; Vågen, I.; Agati, G.; Tuccio, L.; Kaniszewski, S.; Grzegorzewska, M.; Kosson, R.; Bartoszek, A.; Erdogdu, F.; Tutar, M.; et al. Sunniva-Final Report; Nofima: Tromsø, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grzegorzewska, M.; Badelek, E.; Sikorska-Zimny, K.; Kaniszewski, S.; Kosson, R. Determination of the Effect of Ethylene Treatment on Storage Ability of Tomatoes. In Proceedings of the XII International Controlled & Modified Atmosphere Research Conference, Warsaw, Poland, 18 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj, R.; Arul, J.; Nadeau, P. Effect of photochemical treatment in the preservation of fresh tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum cv. Capello) by delaying senescence. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1999, 15, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjøstheim, I.H. Effekten Av Forskjellige Lagringsforhold På Tomatenes Kvalitet (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) Fra Høsting Til Konsum. Master’s Thesis, Universitetet for Miljø-og Biovitenskap, Ås, Norway, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Batu, A. Effect of Long-Term Controlled Atmosphere Storage on the Sensory Quality of Tomatoes. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2003, 15, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, I.; Lafuente, M.T.; Hernández-Muñoz, P.; Gavara, R. Influence of modified atmosphere and ethylene levels on quality attributes of fresh tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Food Chem. 2016, 209, 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J. Waste Not, Want Not, Emit Less. Science 2016, 352, 408–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanke, M. Challenges of Reducing Fresh Produce Waste in Europe—From Farm to Fork. Agriculture 2015, 5, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Nema, N.K.; Maity, N.; Sarkar, B.K. Phytochemical and therapeutic potential of cucumber. Fitoterapia 2013, 84, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Razzak, H.; Alkoaik, F.; Rashwan, M.; Fulleros, R.; Ibrahim, M. Tomato Waste Compost as an Alternative Substrate to Peat Moss for the Production of Vegetable Seedlings. J. Plant Nutr. 2019, 42, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, K.; Sulc, D. Herstellung Von Gemüsesaften. In Frucht-Und Gemüsesäfte; Schobinger, U., Ed.; Ulmer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino, A.; Avelino, H.T.; Roseiro, J.C.; Collaço, M.A. Saccharification of tomato pomace for the production of biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 1997, 61, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, A.; Stintzing, F.; Carle, R. By-products of plant food processing as a source of functional compounds—Recent developments. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 12, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wandawi, H.; Abdul-Rahman, M.; Al-Shaikhly, K. Tomato processing wastes as essential raw materials source. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1985, 33, 804–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Florida. Lycopene-Extraction Method Could Find Use for Tons of Discarded Tomatoes. Available online: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2004/05/040505064902.htm (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- Baysal, T.; Ersus, S.; Starmans, D.A.J. Supercritical CO2 extraction of beta-carotene and lycopene from tomato paste waste. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 5507–5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenucci, M.S.; De Caroli, M.; Marrese, P.P.; Iurlaro, A.; Rescio, L.; Böhm, V.; Dalessandro, G.; Piro, G. Enzyme-aided extraction of lycopene from high-pigment tomato cultivars by supercritical carbon dioxide. Food Chem. 2015, 170, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lianfu, Z.; Zelong, L. Optimization and comparison of ultrasound/microwave assisted extraction (UMAE) and ultrasonic assisted extraction (UAE) of lycopene from tomatoes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008, 15, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Sicaire, A.-G.; Meullemiestre, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Abert-Vian, M. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction of Food and Natural Products. Mechanisms, Techniques, Combinations, Protocols and Applications. A Review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 34, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatami, T.; Meireles, M.A.A.; Ciftci, O.N. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of lycopene from tomato processing by-products: Mathematical modeling and optimization. J. Food Eng. 2019, 241, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo, E.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Improving Carotenoid Extraction from Tomato Waste by Pulsed Electric Fields. Front. Nutr. 2014, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, R.K.; Keum, Y.-S. Carotenoid extraction methods: A review of recent developments. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østerlie, M.; Lerfall, J. Lycopene from tomato products added minced meat: Effect on storage quality and colour. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.C.; Goto, M.; Hirose, T. Temperature and pressure effects on supercritical CO2 extraction of tomato seed oil. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 1996, 31, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Venkitasamy, C.; Li, X.; Pan, Z.; Shi, J.; Wang, B.; Teh, H.E.; McHugh, T. Thermal and storage characteristics of tomato seed oil. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahnaky, A.; Abbasi, A.; Jamalian, J.; Mesbahi, G. The use of tomato pulp powder as a thickening agent in the formulation of tomato ketchup. J. Texture Stud. 2008, 39, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassino, A.N.; Brnčić, M.; Vikić-Topić, D.; Roca, S.; Dent, M.; Brnčić, S.R. Ultrasound assisted extraction and characterization of pectin from tomato waste. Food Chem. 2016, 198, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savadkoohi, S.; Hoogenkamp, H.; Shamsi, K.; Farahnaky, A. Color, sensory and textural attributes of beef frankfurter, beef ham and meat-free sausage containing tomato pomace. Meat Sci. 2014, 97, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Kaul, P. Evaluation of Tomato Processing By-Products: A Comparative Study in a Pilot Scale Setup. J. Food Process. Eng. 2014, 37, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadin, M.; Abu-Reesh, I.; Haddadin, F.; Robinson, R. Utilisation of tomato pomace as a substrate for the production of vitamin B12-A preliminary appraisal. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 78, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variety | Total Lycopene | Type | Origin | Growth Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministar | 3.11 | plum | SW Norway | Greenhouse, soil free | This study |

| Juanita | 10.51 | cherry | |||

| Dometica | 4.08 | salad | |||

| Volna | 8.15 | salad | Skierniewice, Poland | Field | |

| Calista | 10.75 | processing | |||

| Pearson | 10.77 | N/A | California, USA | Field | [38] |

| DX-54 | ~12 | N/A | Utah, USA | Field | [39] |

| Unknown | 15.8 | N/A | Florida, USA | Unknown | [40] |

| Amico | 7.73 | processing | Gödöllö, Hungary | Field | [41] |

| Casper | 6.61 | ||||

| Góbé | 5.92 | ||||

| Ispana | 6.22 | ||||

| Pollux | 5.14 | ||||

| Soprano | 8.65 | ||||

| Tenger | 7.66 | ||||

| Uno | 7.09 | ||||

| Zaphyre | 6.95 | ||||

| Draco | 6.87 | ||||

| Jovanna | 11.61 | ||||

| K-541 | 9.95 | ||||

| Nivo | 8.46 | ||||

| Simeone | 9.88 | ||||

| Sixtina | 10.51 | ||||

| Monika | 7.22 | salad | |||

| Delfine | 6.51 | ||||

| Marlyn | 5.53 | ||||

| Fanny | 5.26 | ||||

| Tiffany | 6.23 | ||||

| Alambra | 5.40 | ||||

| Regulus | 6.59 | ||||

| Petula | 6.68 | ||||

| Diamina | 6.48 | ||||

| Brillante | 8.47 | ||||

| Furone | 5.18 | ||||

| Linda | 5.69 | ||||

| Early Fire | 10.1–14.0 | processing | Field | [42] | |

| Bonus | 8.5–12.7 | ||||

| Falcorosso | 8.0–11.1 | ||||

| Korall | 8.1–11.3 | ||||

| Nívó | 9.7–15.5 | ||||

| Strombolino | 5.3–10.3 | cherry, processing | Gödöllö, Hungary | Field | [43] |

| 12 unnamed local varieties | 5.04–13.46 | N/A | SE Spain | Field | [44] |

| ACE 55 VF | 6.38 | Flattened globe | |||

| Marglobe | 8.46 | Round | |||

| Marmande | 7.01 | Flattened globe | |||

| CIDA-62 | 6.23 | cherry | Spain | Organic, field | [45] |

| CIDA-44A | 2.95 | round | |||

| CIDA-59A | 2.70 | ||||

| BGV-004123 | 5.50 | ||||

| BGV-001020 | 3.66 | flattened and ribbed | |||

| Baghera | 4.64 | round | |||

| CXD277 | 15.33 | processing | Spain | Field | [46] |

| H9661 | 12.21 | ||||

| H9997 | 14.96 | ||||

| H9036 | 11.36 | ||||

| ISI-24424 | 17.01 | ||||

| Kalvert | 16.71 | ||||

| Kalvert | 20.2 | processing | Lecce, Italy | Field | [47] |

| Hly18 | 19.5 | ||||

| Donald | 9.5 | ||||

| Incas | 9.3 | ||||

| 143 | 9.47 | N/A | San Marzano, Italy | Field | [48] |

| Stevens | 10.2 | ||||

| Poly20 | 16.0 | ||||

| Ontario | 6.54 | ||||

| Sel6 | 9.73 | ||||

| Poly56 | 14.2 | ||||

| 1447 | 5.61 | ||||

| 977 | 10.0 | ||||

| 1513 | 9.21 | ||||

| 988 | 14.1 | ||||

| Cayambe | 13.5 | ||||

| Heline | 9.46 | ||||

| 1512 | 3.25 | ||||

| 1438 | 6.35 | ||||

| Motelle | 16.9 | ||||

| Momor | 13.3 | ||||

| 981 | 2.33 | ||||

| Poly27 | 11.0 | ||||

| Shasta | 6.7–7.7 | Early-season varieties | California, USA | Field | [49] |

| H9888 | 8.9–9.7 | ||||

| Apt410 | 9.1–10.0 | ||||

| CXD179 | 9.2–10.4 | Mid-season varieties | |||

| CXD254 | 10.5–12.0 | ||||

| H8892 | 8.7–10.1 | ||||

| CXD222 | 9.8–13.2 | Late-season varieties | |||

| H9665 | 8.7–12.2 | ||||

| H9780 | 9.2–13.0 | ||||

| Bos3155 | 14.92 | Red varieties | California, USA | Field | [50] |

| CXD510 | 15.37 | ||||

| CXD514 | 11.80 | ||||

| CXD276 | 2.47 | Light color Tangerine variety | |||

| CX8400 | 0.08 | Yellow variety | |||

| CX8401 | 0.68 | Orange variety | |||

| CX8402 | 0.03 | Green variety | |||

| SEL-7 | 3.23 | N/A | Haryana, India | [51] | |

| ARTH-3 | 4.03 | ||||

| Laura | 12.20 | N/A | New Jersey, USA | Greenhouse | [52] |

| Brigade | 12.9 | Processing | Salerno, Italy | N/A | [53] |

| PC 30956 | 18.7 | High lycopene experimental hybrid, | |||

| Cheers | 3.7 | N/A | Southern France | Greenhouse | [54] |

| Lemance | 3.7–6.9 | N/A | N/A | Greenhouse | [36] |

| Ohio-8245 | 9.93 | Tomato pulp fraction | Ontario, Canada | N/A | [55] |

| 92-7136 | 7.76 | ||||

| 92-7025 | 6.46 | ||||

| H-9035 | 10.19 | ||||

| CC-164 | 10.70 | ||||

| Dasher | 3.98 | Plum | Italy | Greenhouse | [56] |

| Iride | 4.45 | ||||

| Navidad | 4.89 | ||||

| Sabor | 5.22 | ||||

| 292 | 4.57 | ||||

| 738 | 4.77 | ||||

| Cherubino | 3.43 | Cherry | |||

| Crimson, green, | 0.52 | Salad | Ohio, USA | Purchased from local market | [57] |

| Crimson, breaker | 3.84 | ||||

| Crimson, red | 5.09 | ||||

| Unknown | 10.14 | Cherry | California, USA | Purchased from local supermarket | [58] |

| Unknown | 5.98 | On-the-vine | |||

| Roma | 8.98 | Processing | |||

| Jennita | 1.60–5.54 | Cherry | SW Norway | Greenhouse, soil free | [59] a |

| Naomi | 7.1–12.0 | Cherry | Sicily, Italy | Cold greenhouse | [60] b |

| Naomi | 12.4–13.3 | Cherry | Italy | Cold greenhouse | [34] |

| Ikram | 8.5–8.9 | Cluster | |||

| Eroe | 2.1–2.8 | Salad | |||

| Corbarino | 6.8–14.6 | Cherry | Battipaglia, Italy | Field grown | [61] c |

| Cultivar | Total Lycopene (Converted to mg/100 g FW) | Comment | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peel | Pulp | |||

| HLT-F61 | 89.3 | 28.0 | Field grown, Northern Tunisia | [62] |

| HLT-F62 | 50.8 | 16.7 | ||

| Rio Grande | 42.4 | 10.1 | ||

| 8-2-1-2-5 | 14.3 | 6.7 | Harvested at mature green stage (Ludhiana, India) and stored at 20 °C until ripe | [37] |

| Castle Rock | 13.1 | 6.2 | ||

| IPA3 | 10.2 | 4.0 | ||

| Pb Chhuhra | 8.6 | 4.6 | ||

| UC-828 | 6.5 | 3.7 | ||

| WIR 4285 | 6.5 | 3.1 | ||

| WIR-4329 | 8.1 | 4.3 | ||

| 818 cherry | 14.1 | 6.9 | Field grown, New Delhi, India | [63] |

| DT-2 | 8.1 | 5.2 | ||

| BR-124 cherry | 10.2 | 4.9 | ||

| 5656 | 10.7 | 4.5 | ||

| 7711 | 9.0 | 4.4 | ||

| Rasmi | 10.8 | 4.3 | ||

| Pusa Gaurav | 10.2 | 4.0 | ||

| T56 cherry | 12.0 | 3.8 | ||

| DTH-7 | 4.8 | 2.7 | ||

| FA-180 | 7.6 | 2.5 | ||

| FA-574 | 6.1 | 2.2 | ||

| R-144 | 6.2 | 2.0 | ||

| Grapolo | 6.0 | 1.2 | Purchased in supermarket or open-air market, Zagreb, Croatia, | [64] |

| Italian cherry tomato | 7.2 | 2.0 | ||

| Croatian cherry tomato | 5.3 | 1.6 | ||

| Croatian large size tomato | 3.5 | 1.3 | ||

| Turkish large size tomato | 3.3 | 1.2 | ||

| Processing | Heat Treatment | Effect | Texture | Taste | Lycopene | Color |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chopping raw | Mild < 80 °C | Enzymes are released, pectin degraded and hexanal/hexanol formed | Thick before heating, then soup | Vivid Green | Unchanged | Poor, controlled by pH |

| Strong > 80 °C | Moderate green | Increased | Acceptable | |||

| Chopping raw, waiting for thickening before cooking, for example 2 h | Instantly to 100 °C, medium shortly, to thicken | Slightly thick and thickens with increased cooking time | Vivid Green | Somewhat increased | Acceptable | |

| Chopping cooked | Mild < 80 °C | Enzymes inactivated only partially | Thin | Moderate green | Unchanged | Poor, controlled by pH |

| Strong > 80 °C | Enzymes inactivated | Thick | Green aroma | Unknown | Acceptable | |

| Puree, unpeeled | 2 h 100 °C | Carotenoid content maximum after 2 h. | Unknown | A little green | Most after 2 h * | Most after 2 h |

| Puree, peeled | Carotenoid content low and stable unaffected by time | Less than unpeeled | Less than unpeeled |

| Product | Total Lycopene | Comment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulp | 10.6–18.7 | Commercial products, Salerno, Italy | [53] |

| Purée | 12.7–19.6 | ||

| Paste | 57.87 | Commercial products, California, USA | [58] |

| Purée | 23.46 | ||

| Juice | 10.33 | ||

| Ketchup | 12.26–14.69 | ||

| Juice, heat concentrated | 2.34 | Experimentally processed from Crimson-type tomatoes purchased from local markets, Ohio, USA | [57] |

| Paste, heat concentrated | 9.93 | ||

| Soup, retorted | 10.72 | ||

| Sauce, retorted | 10.22 | ||

| Juice | 7.83 | Experimentally processed from tomatoes purchased from local markets and heat treated according to standardized industrial food processing requirements | [25] |

| Soup, condensed | 7.99 | ||

| Canned whole tomato | 11.21 | ||

| Canned pizza sauce | 12.71 | ||

| Paste | 30.07 | ||

| Powder, spray dried | 126.49 | ||

| Powder, sun dried | 112.63 | ||

| Sun dried in oil | 46.50 | ||

| Ketchup | 13.44 | ||

| Tangerine tomato sauce | 4.86 | Experimentally processed from tomatoes grown at the Ohio State University, USA | [30] |

| Tangerine tomato juice | 2.19 | ||

| Red tomato juice | 7.63 | ||

| Regular salad tomatoes, Gran Canaria, Spain | 1.15 | Fresh | [69] |

| 1.09 | Boiled 10 min | ||

| 0.99–1.18 | LTLT, 60 °C 40 min | ||

| 1.07–1.23 | HTST, 90 °C 4 min | ||

| Bella Donna on the vine, Netherlands | 3.80 | Fresh | |

| 3.06 | Boiled 20 min | ||

| 3.91–4.31 | LTLT, 60 °C 40 min | ||

| 3.43–4.15 | HTST, 90 °C 10 min | ||

| Daniella, Spain | 2.37 | Fresh purée | [81] |

| Daniella, Spain | 0.99 | Fresh | [80] |

| 1.48 | HP (400 MPa, 25 °C, 15 min) | ||

| 0.86 | Pasteurization (70 °C, 30 s) | ||

| 0.95 | Pasteurization (90 °C, 60 s) | ||

| Torrito, Spain | 39.67 | Fresh | This study |

| 26.39 | HTST (90 °C, 15 min) | ||

| 23.77 | HP (400 MPa, 90 °C, 15 min) | ||

| Torrito, the Netherlands | 11.44 | Fresh | |

| 7.57 | HTST (90 °C, 15 min) | ||

| 10.10 | HP (400 MPa, 90 °C, 15 min) | ||

| 10.00 | HP (400 MPa, 20 °C, 15 min) | ||

| 5.41 | HP (600 MPa, 90 °C, 15 min) | ||

| 4.08 | HP(600 MPa, 20 °C, 15 min) | ||

| Heinz purée, USA | 6.62 | Puré, fresh | [83] |

| 6.61 | Boiled 5 min | ||

| 6.57 | Boiled 10 min | ||

| 6.48 | Boiled 30 min | ||

| 6.39 | Boiled 60 min | ||

| Double concentrated commercial canned tomato purée, Netherlands | 39 | Unheated | [68] |

| 31 | Autoclaved 100 °C, 20 min | ||

| 29 | Autoclaved 100 °C, 60 min | ||

| 29 | Autoclaved 100 °C, 120 min | ||

| 28 | Autoclaved 120 °C, 20 min | ||

| 30 | Autoclaved 120 °C, 60 min | ||

| 29 | Autoclaved 120 °C, 120 min | ||

| 31 | Autoclaved 135 °C, 20 min | ||

| 33 | Autoclaved 135 °C, 60 min | ||

| 32 | Autoclaved 135 °C, 120 min | ||

| Experimental purée | 3.79 | Unheated | [84] |

| 5.93 | Steam retorted, 90 °C, 110 min | ||

| 5.20 | Steam retorted, 100 °C, 11 min | ||

| 4.74 | Steam retorted, 110 °C, 1.1 min | ||

| 3.37 | Steam retorted, 120 °C, 0.11 min | ||

| FG99-218, USA | 16.04 | Juice, fresh | [85] |

| 16.05 | Juice, hot break | ||

| 17.95 | Juice, HP (700 Mpa/45 °C/10 min) | ||

| 17.12 | Juice, HP (600 Mpa/100 °C/10 min) | ||

| 15.50 | Juice, TP (100 °C/35 min) | ||

| OX325, USA | 9.84 | Juice, fresh | |

| 10.22 | Juice, hot break | ||

| 10.88 | Juice, HP (700 Mpa/45 °C/10 min) | ||

| 10.29 | Juice, HP (600 Mpa/100 °C/10 min) | ||

| 8.49 | Juice, TP (100 °C/35 min) |

| Produkt | Total Lycopene | All Trans Lycopene (% of Total) | Cis Lycopene (% of Total) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conesa tomato paste, Spain, 0.16% fat Batch 1 (2014) | 32.1 | 29.2 (91.0) | 2.9 (9.0) | This study |

| Conesa tomato paste Spain, 0.16% fat Batch 2 (2015) | 26.6 | 23.6 (88.7) | 3.0 (11.3) | |

| Conesa tomato paste Spain, 0.16% fat Batch 2 (2015)—Autoclaved | 22.8 | 19.9 (87.3) | 2.9 (12.7) | |

| Conesa tomato paste Spain, 0.16% fat Batch 2 (2015)—Microwaved | 22.9 | 20.1 (87.8) | 2.8 (12.2) | |

| Conesa tomato fine chopped, Spain, 0.04% fat | 6.5 | 5.9 (90.8) | 0.6 (9.2) | |

| Heinz ketchup 0.1% fat | 11.0 | 9.4 (85.5) | 1.6 (14.5) | |

| Eldorado tomato puree, Italy, 1% fat | 32.1 | 29.4 (91.6) | 2.7 (8.4) | |

| Cherry tomatoes | 10.14 | 8.91 (87.9) | 1.23 (12.1) | [58] |

| On-the-vine tomatoes | 5.98 | 5.00 (83.6) | 0.98 (16.4) | |

| Roma tomatoes | 8.98 | 7.88 (87.7) | 1.10 (12.3) | |

| Tomato paste | 57.87 | 45.94 (79.4) | 11.93 (20.6) | |

| Tomato purée | 23.46 | 17.85 (76.1) | 5.61 (23.9) | |

| Tomato juice | 10.33 | 8.47 (82.0) | 1.86 (18.0) | |

| Tomato ketchup | 12.26–14.69 | 9.40–9.47 (64.4–76.7) | 2.86–5.22(23.3–35.6) |

| Product | Active Ingredients | Fraction | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Color pigments, Antioxidants | Lycopene | Skin, pomace, whole fruit | [72,102,110] |

| Tomato seed oil | Unsaturated fatty acids (linoleic acid) | Seeds | [111,112] |

| Thickening agent | Pectin | Dried Pomace | [113,114] |

| Comminuted and vegetarian sausages | Dried and bleached tomato pomace | Dried Pomace | [115] |

| Tomato seed meals | Protein, polyphenols, etc. | Seeds, pomace | [116] |

| Nutrient supplements | Vitamin B12 | Pomace | [117] |

| Cosmetics | Phenolic compounds, antioxidants, lactic acid, etc. | Whole plant | [96] |

| Compost, growth substrates, fertilizer | Phytochemicals | Whole plant | [97] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Løvdal, T.; Van Droogenbroeck, B.; Eroglu, E.C.; Kaniszewski, S.; Agati, G.; Verheul, M.; Skipnes, D. Valorization of Tomato Surplus and Waste Fractions: A Case Study Using Norway, Belgium, Poland, and Turkey as Examples. Foods 2019, 8, 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8070229

Løvdal T, Van Droogenbroeck B, Eroglu EC, Kaniszewski S, Agati G, Verheul M, Skipnes D. Valorization of Tomato Surplus and Waste Fractions: A Case Study Using Norway, Belgium, Poland, and Turkey as Examples. Foods. 2019; 8(7):229. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8070229

Chicago/Turabian StyleLøvdal, Trond, Bart Van Droogenbroeck, Evren Caglar Eroglu, Stanislaw Kaniszewski, Giovanni Agati, Michel Verheul, and Dagbjørn Skipnes. 2019. "Valorization of Tomato Surplus and Waste Fractions: A Case Study Using Norway, Belgium, Poland, and Turkey as Examples" Foods 8, no. 7: 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8070229

APA StyleLøvdal, T., Van Droogenbroeck, B., Eroglu, E. C., Kaniszewski, S., Agati, G., Verheul, M., & Skipnes, D. (2019). Valorization of Tomato Surplus and Waste Fractions: A Case Study Using Norway, Belgium, Poland, and Turkey as Examples. Foods, 8(7), 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8070229