Perceptions of Young People Regarding the Tax on Sweetened Drinks in Poland and an Assessment of Changes in Their Consumption in Terms of Taxation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bombak, A.E.; Colotti, T.E.; Raji, D.; Riediger, N.D. Exploring attitudes toward taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages in rural Michigan. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2021, 40, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro, T.G.; Eyles, H.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Young, L.; Mackay, S. Seven-year trends in the availability, sugar content and serve size of single-serve non-alcoholic beverages in New Zealand: 2013–2019. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, V.S.; Li, Y.; Pan, A.; Koning, L.D.; Schernhammer, E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Long-term consumption of sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages and risk of mortality in US adults. Circulation 2019, 139, 2113–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, E.M.; Baraldi, L.G.; da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Moubarac, J.C.; Mozaffarian, D.; Monteiro, C.A. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Song, J.; MacGregor, G.A.; Feng, J.; He, F.J. Consumption of soft drinks and overweight and obesity among adolescents in 107 countries and regions. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2325158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Li, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Sugar and artificially sweetened beverages and risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and all-cause mortality: A dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Food Research Program UNC. Sugary Drink Taxes Around the World. Available online: https://globalfoodresearchprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/SugaryDrink_tax_maps_2020_August_REV.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Powell, L.M.; Andreyeva, T.; Isgor, Z. Distribution of sugar-sweetened beverage sales volume by content in the United States: Implications for tiered taxation and tax revenue. J. Public Health Policy 2020, 41, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 11 October 2015 on Public Health. Dz. U. 2015, 1916. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20150001916/O/D20151916.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Singh, G.M.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Shi, P.; Lim, S.; Andrews, K.G.; Engell, R.E.; Ezzati, M.; Mozaffarian, D. Global Burden of Diseases Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group (NutriCoDE). Global, regional, and national consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juices, and milk: A systematic assessment of beverage intake in 187 countries. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelinckx, I.I.; Iglesia, I.I.; Bottin, J.H.; De Miguel-Etayo, P.P.; Gil, E.M.G.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Kavouras, S.; Gandy, J.J.; Martinez, H.; Bardosono, S.; et al. Intake of water and beverages of children and adolescents in 13 countries. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.; Wittekind, A. Soft drink intake in Europe—A review of data from nationally representative food consumption surveys. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, T.; Marple, K.; Marinello, S.; Moore, T.E.; Powell, L.M. Outcomes following taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2215276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagenaars, L.L.; Jeurissen, P.P.T.; Klazinga, N.S.; Listl, S.; Jevdjevic, M. Effectiveness and policy determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 1444–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, F.; An, R. Impact of soda tax on beverage price, sale, purchase, and consumption in the US: A systematic review and meta-analysis of natural experiments. Front. Public Health 2023, 22, 1126569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, A.M.; Jones, A.C.; Mizdrak, A.; Signal, L.; Genç, M.; Wilson, N. Impact of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes on purchases and dietary intake: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1187–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashem, K.M.; He, F.J.; MacGregor, G.A. Labelling changes in response to a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzejska, R.E. The impact of the sweetened beverages tax on their reformulation in Poland—The analysis of the composition of commercially available beverages before and after the introduction of the tax (2020 vs. 2021). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, C.; Van der Lans, I.A.; Van Rijnsoever, F.J.; Van Trijp, H.C. Understanding consumer acceptance of intervention strategies for healthy food choices: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2013, 3, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagmann, D.; Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Taxes, labels, or nudges? Public acceptance of various interventions designed to reduce sugar intake. Food Policy 2018, 79, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E.A.; Madsen, K.A.; Schmidt, L.A. Missed Opportunities: The need to promote public knowledge and awareness of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Avila, A.G.; Papadaki, A.; Jago, R. Exploring perceptions of the Mexican sugar-sweetened beverage tax among adolescents in north-west Mexico: A qualitative study. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, V.M.; Knox, M.A.; Pinero Walkinshaw, L.; Saelens, B.E.; Chan, N.; Jones-Smith, J.C. Evaluation of Seattle’s sweetened beverage tax on tax support and perceived economic and health impacts. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 30, 101809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrescu, D.C.; Hollands, G.J.; Couturier, D.-L.; Ng, Y.-L.; Marteau, T.M. Public acceptability in the UK and USA of nudging to reduce obesity: The example of reducing sugar-sweetened beverages consumption. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brukało, K.; Kaczmarek, K.; Kowalski, O.; Romaniuk, P. Implementation of sugar-sweetened beverages tax and its perception among public health stakeholders. A study from Poland. Front. Nutr. 2022, 29, 957256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekara, A. Sugar tax or what? The perspective and preferences of consumers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosire, E.N.; Stacey, N.; Mukoma, G.; Tugendhaft, A.; Hofman, K.; Norris, S.A. Attitudes and perceptions among urban South Africans towards sugar-sweetened beverages and taxation. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarda, B.; Debras, C.; Chazelas, E.; Péneau, S.; Le Bodo, Y.; Hercberg, S.; Touvier, M.; Julia, C. Public perception of the tax on sweetened beverages in France. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 3240–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Use of Non-Sugar Sweeteners: WHO Guideline. World Health Organization, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240073616 (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Use of nutritive and nonnutritive sweeteners. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 104, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, K. Is the use of artificial sweeteners beneficial for patients with diabetes mellitus? The advantages and disadvantages of artificial sweeteners. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.A.; Lee, J.J.; Ayoub-Charette, S.; Noronha, J.C.; McGlynn, N.; Chiavaroli, L.; Sievenpiper, J.L. WHO guideline on the use of non-sugar sweeteners: A need for reconsideration. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 77, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eykelenboom, M.; van Stralen, M.M.; Olthof, M.R.; Renders, C.M.; Steenhuis, I.H. PEN Consortium. Public acceptability of a sugar-sweetened beverage tax and its associated factors in the Netherlands. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 2354–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, T.E.; Yanada, B.A.; Watters, D.; Stupart, D.; Lamichhane, P.; Bel, C. What young Australians think about a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages. Aust. NZ J. Public Health 2019, 43, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krukowski, C.N.; Conley, K.M.; Sterling, M.; Rainville, A.J. A qualitative study of adolescent views of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes, Michigan, 2014. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2016, 5, E60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoś, K.; Rychlik, E.; Woźniak, A.; Ołtarzewski, M.; Wojda, B.; Przygoda, B.; Matczuk, E.; Pietraś, E.; Kłys, W. Krajowe badanie Sposobu Żywienia i Stanu Odżywienia Populacji Polskiej. Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego PZH—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy. Warszawa 2021. Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Raport-z-projektu-EFSA-18.10.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Wlazło, M.; Zięba, N.; Mąkosza, K.; Janota, B.; Szczepańska, E. Consumption of snacks and sweetened beverages and physical activity of schoolchildren aged 10–16 years. Med. Ogólna I Nauk. O Zdrowiu 2023, 3, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

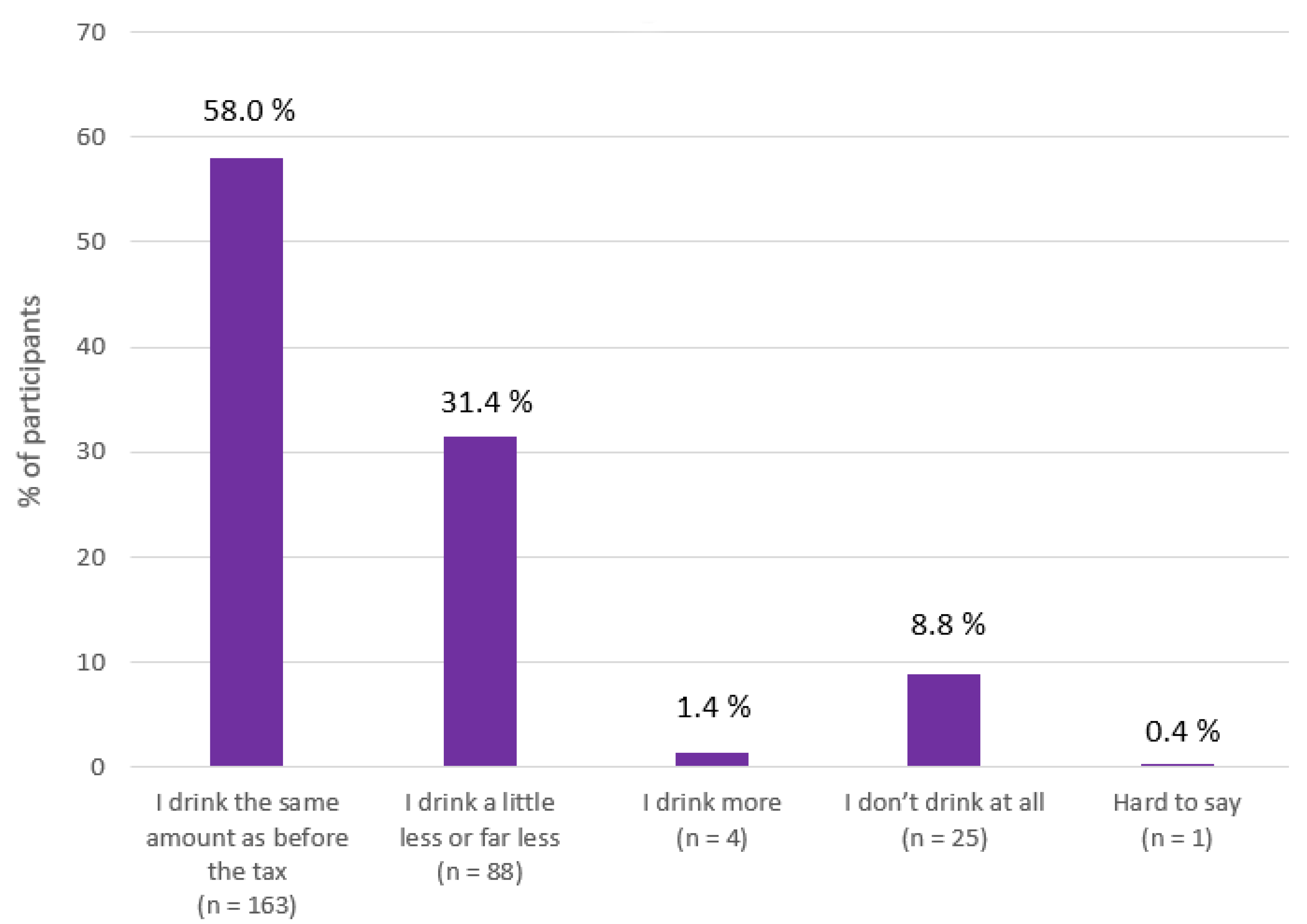

| The Approach to Beverage Consumption after the Introduction of the Tax | School Students (n = 146) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (n; %) | Boys (n; %) | p-Value | Total (n; %) | |

| I drink the same amount as before the tax | 47; 55.3 | 34; 55.7 | 81; 55.5 | |

| I drink a little less | 14; 16.5 | 12; 19.7 | 26; 17.8 | |

| I drink far less | 13; 15.3 | 11; 18.0 | 24; 16.4 | |

| I drink more | 2; 2.3 | 1; 1.6 | 3; 2.1 | |

| I don’t drink at all | 9; 10.6 | 3; 5.0 | p < 0.05 | 12; 8.2 |

| Hard to say | 0; 0.0 | 0; 0.0 | 0; 0 | |

| University Students (n = 135) | ||||

| Women (n; %) | Men (n; %) | p-Value | Total (n; %) | |

| I drink the same amount as before the tax | 42; 54.5 | 40; 69.0 | 82; 60.8 | |

| I drink a little less | 14; 18.2 | 4; 6.9 | p < 0.05 | 18; 13.4 |

| I drink far less | 13; 16.9 | 7; 12.1 | p < 0.05 | 20; 14.8 |

| I drink more | 0; 0.0 | 1; 1.7 | 1; 0.7 | |

| I don’t drink at all | 7; 9.1 | 6; 10.3 | 13; 9.6 | |

| Hard to say | 1; 1.3 | 0; 0.0 | 1; 0.7 | |

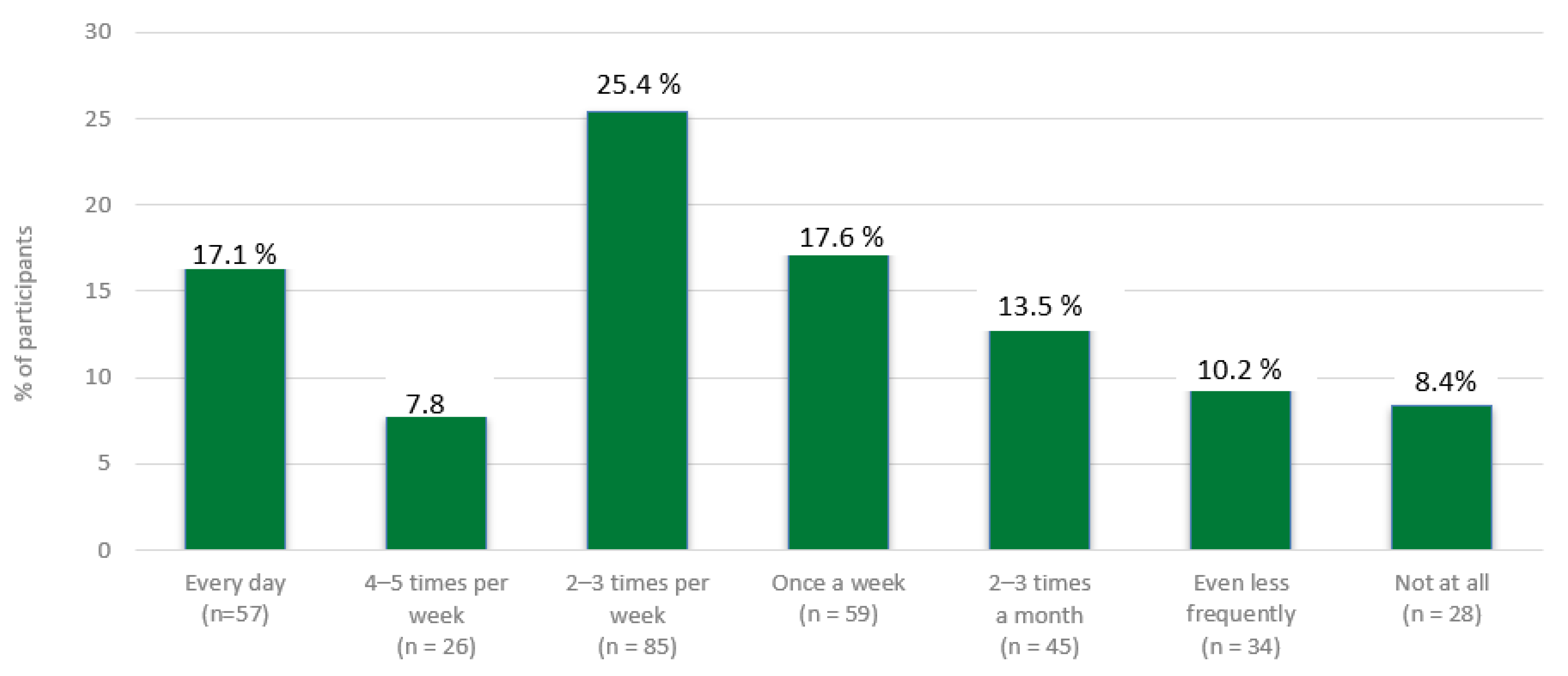

| The Usual Frequency of Drinking Sweetened Beverages | School Students (n = 167) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (n; %) | Boys (n; %) | p-Value | Total (n; %) | |

| Every day | 15; 15.3 | 15; 21.7 | p < 0.05 | 30; 17.9 |

| 4–5 times per week | 5; 5.1 | 9; 13.1 | p < 0.05 | 14; 8.4 |

| 2–3 times per week | 25; 25.5 | 17; 24.6 | 42; 25.1 | |

| Once a week | 21; 21.4 | 12; 17.4 | 33; 19.8 | |

| 2–3 times a month | 10; 10.2 | 8; 11.6 | 18; 10.8 | |

| Even less frequently | 13; 13.3 | 4; 5.8 | p < 0.05 | 17; 10.2 |

| Not at all | 9; 9.2 | 4; 5.8 | 13; 7.8 | |

| University Students (n = 167) | ||||

| Women (n; %) | Men (n; %) | p-Value | Total (n; %) | |

| Every day | 16; 16.5 | 11; 15.7 | 27; 16.2 | |

| 4–5 times per week | 7; 7.2 | 5; 7.1 | 12; 7.2 | |

| 2–3 times per week | 22; 22.7 | 21; 30.0 | p < 0.05 | 43; 25.7 |

| Once a week | 13; 13.4 | 12; 17.2 | 26; 15.6 | |

| 2–3 times a month | 19; 19.6 | 9; 12.8 | p < 0.05 | 27; 16.2 |

| Even less frequently | 11; 11.3 | 6; 8.6 | 17; 10.2 | |

| Not at all | 9; 9.3 | 6; 8.6 | 15; 8.9 | |

| The Test Group (n = 334) | The Usual Frequency of Drinking Sweetened Beverages | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every Day (n; %) | 4–5 Times per Week (n; %) | 2–3 Times per Week (n; %) | Once a Week (n; %) | 2–3 Times a Month (n; %) | Even Less Frequently (n; %) | Not at All (n; %) | |

| people aged ≤ 23 years (n = 299) | 52; 17.4 | 25; 8.4 | 78; 26.1 | 54; 18.0 | 38; 12.7 | 28; 9.4 | 24; 8.0 |

| people aged > 23 years (n = 35) | 5; 14.3 | 1; 2.9 | 7; 20.0 | 4; 11.4 | 8; 22.8 | 6; 17.2 | 4; 11.4 |

| p-value | p < 0.05 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wierzejska, R.E.; Wiosetek-Reske, A.; Wojda, B. Perceptions of Young People Regarding the Tax on Sweetened Drinks in Poland and an Assessment of Changes in Their Consumption in Terms of Taxation. Beverages 2024, 10, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages10030085

Wierzejska RE, Wiosetek-Reske A, Wojda B. Perceptions of Young People Regarding the Tax on Sweetened Drinks in Poland and an Assessment of Changes in Their Consumption in Terms of Taxation. Beverages. 2024; 10(3):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages10030085

Chicago/Turabian StyleWierzejska, Regina Ewa, Agnieszka Wiosetek-Reske, and Barbara Wojda. 2024. "Perceptions of Young People Regarding the Tax on Sweetened Drinks in Poland and an Assessment of Changes in Their Consumption in Terms of Taxation" Beverages 10, no. 3: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages10030085

APA StyleWierzejska, R. E., Wiosetek-Reske, A., & Wojda, B. (2024). Perceptions of Young People Regarding the Tax on Sweetened Drinks in Poland and an Assessment of Changes in Their Consumption in Terms of Taxation. Beverages, 10(3), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages10030085