Natural Products against Sand Fly Vectors of Leishmaniosis: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

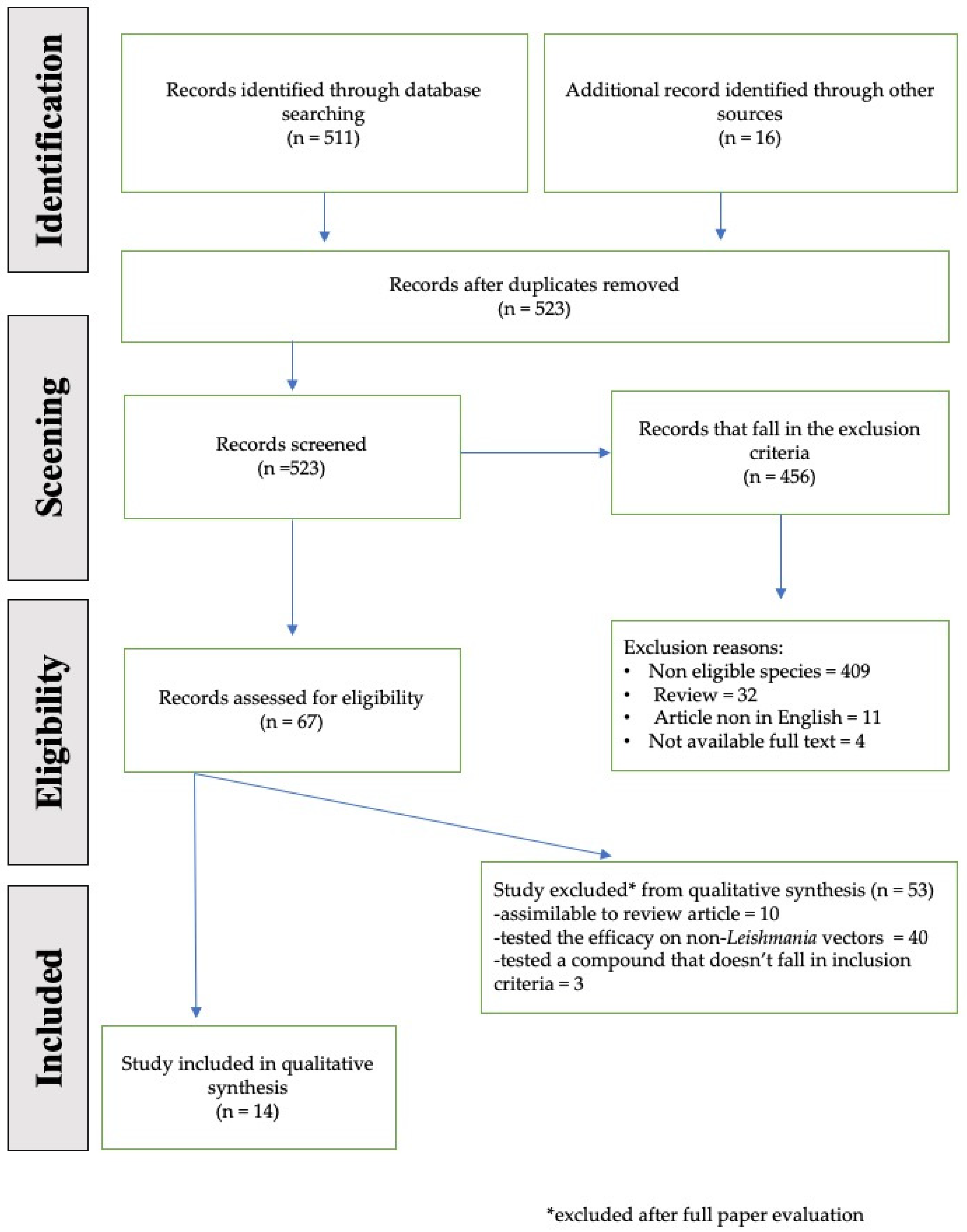

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- The publication was in English (i.e., at least the abstract);

- The full text was available;

- Inspected the effects of plant-based products against sand fly vectors of Leishmania spp.;

- Reported the percentage of repellency and/or complete protection time and/or insecticide efficacy;

- Were original studies conducted in the laboratory and/or field conditions.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Control of the Leishmaniases: Report of a Meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on the Control of Leishmaniases, Geneva, 22–26 March 2010. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44412 (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- Killick-Kendrick, R. The biology and control of phlebotomine sand flies. Clin. Dermatol. 1999, 17, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, G.; Brianti, E.; Napoli, E.; Falsone, L.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Tarallo, V.D.; Otranto, D.; Giannetto, S. Effect of night time-intervals, height of traps and lunar phases on sand fly collection in a highly endemic area for canine leishmaniasis. Acta Trop. 2014, 133, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroli, M.; Mizzon, V.; Siragusa, C.; D’Oorazi, A.; Gradoni, L. Evidence for an impact on the incidence of canine leishmaniasis by the mass use of deltamethrin-impregnated dog collars in southern Italy. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2001, 15, 358–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, J.M.; Arfuso, F.; Napoli, E.; Gaglio, G.; Giannetto, S.; Latrofa, M.S.; Otranto, D.; Brianti, E. Leishmania infantum in wild animals in endemic areas of southern Italy. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 67, 101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramiccia, M. Recent advances in leishmaniosis in pet animals: Epidemiology, diagnostics and anti-vectorial prophylaxis. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 181, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otranto, D.; Dantas-Torres, F. The prevention of canine leishmaniasis and its impact on public health. Trends Parasitol. 2013, 29, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dantas-Torres, F.; Chomel, B.B.; Otranto, D. Ticks and tick-borne diseases: A One Health perspective. Trends Parasitol. 2012, 28, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debboun, M.; Strickman, D. Insect repellents and associated personal protection for a reduction in human disease. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2013, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo Ramirez, G.I.; Logan, J.G.; Loza-Reyes, E.; Stashenko, E.; Moores, G.D. Repellents inhibit P450 enzymes in Stegomyia (Aedes) aegypti. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 48698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nentwig, G. Use of repellents as prophylactic agents. Parasitol. Res. 2003, 90, S40–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.; Zaman, K.; Duarah, S.; Raju, P.S.; Chattopadhyay, P. Mosquito repellents: An insight into the chronological perspectives and novel discoveries. Acta Trop. 2017, 167, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyoum, A.; Pålsson, K.; Kung’a, S.; Kabiru, E.W.; Lwande, W.; Killeen, G.F.; Hassanali, A.; Knols, B.G. Traditional use of mosquito-repellent plants in western Kenya and their evaluation in semi-field experimental huts against Anopheles gambiae: Ethnobotanical studies and application by thermal expulsion and direct burning. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002, 96, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, T.N.; Varma, J.; Dubey, N.K.; Chansouria, J.P.; Ali, Z. Pharmacological evaluation of some bioactive plant products on albino rats. Hindustan Antibiot. Bull. 1998, 40, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dinesh, D.S.; Kumari, S.; Kumar, V.; Das, P. The potentiality of botanicals and their products as an alternative to chemical insecticides to sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae): A review. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2014, 51, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Curtis, S.K. Evaluation of the control of Myobia musculi infestations on laboratory mice with permethrin. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1990, 40, 463. [Google Scholar]

- Mnif, W.; Hassine, A.I.; Bouaziz, A.; Bartegi, A.; Thomas, O.; Roig, B. Effect of endocrine disruptor pesticides: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 2265–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Channa, K.; Rollin, H.B.; Nost, T.H.; Odland, J.O.; Sandanger, T.M. Prenatal ex- posure to DDT in malaria endemic region following indoor residual spraying and in non-malaria coastal regions of South Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 429, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madden, A.H.; Lindquist, A.W.; Longcoy, O.M.; Knipling, E.F. Control of Adult Sand Flies by Airplane Spraying with DDT. Fla. Entomol. 1946, 29, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M.; Foster, G.M.; Deb, R.; Pratap Singh, R.; Ismail, H.M.; Shivam, P.; Ghosh, A.K.; Dunkley, S.; Kumar, V.; Coleman, M.; et al. DDT-based indoor residual spraying suboptimal for visceral leishmaniasis elimination in India. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8573–8578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moore, M.T.; Lizotte, R.E., Jr.; Smith, S., Jr. Responses of Hyalella azteca to a pyrethroid mixture in a constructed wetland. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2007, 78, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, L.W.; Lawrence, K.L.; Coleman, R.E. The role of the United States military in the development of vector control products, including insect repellents, insecticides, and bed nets. J. Vector Ecol. 2009, 34, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, B.; Usma, M.C.; Cadena, H.; Quesada, B.L.; Solarte, Y.; Roa, W.; Montoya, J.; Jaramillo, C.; Travi, B.L. Phlebotomine sandflies associated with a focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Med. Vet. Entomol. 1995, 9, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majori, G.; Maroli, M.; Sabatinelli, G.; Fausto, A.M. Efficacy of permethrin-impregnated curtains against endophilic phlebotomine sandflies in Burkina Faso. Med. Vet. Entomol. 1989, 3, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellse, L.; Sands, B.; Burden, F.A.; Wall, R. Essential oils in the management of the donkey louse, Bovicola ocellatus. Equine Vet. J. 2016, 48, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerio, L.S.; Olivero-Verbel, J.; Stashenko, E. Repellent activity of essential oils: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolaczinski, J.H.; Curtis, C.F. Chronic illness as a result of low-level exposure to synthetic pyrethroid insecticides: A review of the debate. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004, 42, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramwell, C.T.; Heather, A.I. Shepherd AJ. Herbicide loss following application to a railway. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2004, 60, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Stokes, J.V.; Moraru, G.M.; Harper, A.B.; Smith, C.L.; Wills, R.W.; Varela-Stokes, A.S. Transmission of Amblyomma maculatum-Associated Rickettsia spp. During Cofeeding on Cattle. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2018, 18, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela, R.; Maggi, F.; Iannarelli, R.; Benelli, G. Plant extracts for developing mosquito larvicides: From laboratory to the field, with insights on the modes of action. Acta Trop. 2019, 193, 236–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisgratog, R.; Sanguanpong, U.; Grieco, J.P.; Ngoen-Kluan, R.; Chareonviriyaphap, T. Plants traditionally used as mosquito repellents and the implication for their use in vector control. Acta Trop. 2016, 157, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, P.; Dhiman, S.; Borah, S.; Rabha, B.; Chaurasia, A.K.; Veer, V. Essential oil based polymeric patch development and evaluating its repellent activity against mosquitoes. Acta Trop. 2015, 147, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, J.U.; Ali, A.; Khan, I.A. Plant based products: Use and development as repellents against mosquitoes: A review. Fitoterapia 2014, 95, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongkaew, C.; Sakunrag, I.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Tawatsin, A. Effectiveness of citronella preparations in preventing mosquito bites: Systematic review of controlled laboratory experimental studies. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2011, 16, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaalan, E.A.; Canyon, D.; Younes, M.W.; Abdel-Wahab, H.; Mansour, A.H. A review of botanical phytochemicals with mosquitocidal potential. Environ. Int. 2005, 31, 1149–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omolo, M.O.; Okinyo, D.; Ndiege, I.O.; Lwande, W.; Hassanali, A. Repellency of essential oils of some Kenyan plants against Anopheles gambiae. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 2797–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pålsson, K.; Jaenson, T.G. Plant products used as mosquito repellents in Guinea Bissau, West Africa. Acta Trop. 1999, 72, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Kalyanasundaram, M. Relative efficacy of DEPA and neem oil for repellent activity against Phlebotomus papatasi, the vector of leishmaniasis. J. Commun. Dis. 2001, 33, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luitgards-Moura, J.F.; Castellon Bermudez, E.G.; Rocha, A.F.; Tsouris, P.; Rosa-Freitas, M.G. Preliminary assays indicate that Antonia ovata (Loganiaceae) and Derris amazonica (Papilionaceae), ichthyotoxic plants used for fishing in Roraima, Brazil, have an insecticide effect on Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae). Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2002, 97, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maciel, M.V.; Morais, S.M.; Bevilaqua, C.M.; Silva, R.A.; Barros, R.S.; Sousa, R.N.; Sousa, L.C.; Brito, E.S.; Souza-Neto, M.A. Chemical composition of Eucalyptus spp. essential oils and their insecticidal effects on Lutzomyia longipalpis. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ireri, L.N.; Kongoro, J.; Ngure, P.; Mutai, C.; Langat, B.; Tonui, W.; Kimutai, A.; Mucheru, O. The potential of the extracts of Tagetes minuta Linnaeus (Asteraceae), Acalypha fruticosa Forssk (Euphorbiaceae) and Tarchonanthus camphoratus L. (Compositae) against Phlebotomus duboscqi Neveu Lemaire (Diptera: Psychodidae), the vector for Leishmania major Yakimoff and Schokhor. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2010, 47, 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas, J.; Rojas, J.; Rondón, M.; Nieves, E. Adulticide effect of Monticalia greenmaniana (Asteraceae) against Lutzomyia migonei (Diptera: Psychodidae). Parasitol. Res. 2012, 111, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Rojas, J.; Rondón, M.; Morales, A.; Nieves, E. Insecticide Activity of Ageratina jahnii and Ageratina pichinchensis (Asteraceae) against Lutzomyia migonei (Diptera: Psychodidae). Adv. Biomed. Res. 2017, 2, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V.P.; Dhiman, R.C. Neem oil as a sand fly (Diptera: Psychodidae) repellent. J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 1993, 9, 364–366. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, R.; Kalyanasundaram, M. Comparative efficacy of Neem oil and DEPA in repelling sandfly, Phlebotomus papatasi, the vector of cutaneous Leishmaniasis. In Proceedings of the Ist International Seminar on Medical Entomology, Bhopal, India, 19–20 January 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Valerio, L.; Maroli, M. Valutazione dell’effetto repellente ed anti-feeding dell’olio d’aglio (Allium sativum) nei confronti dei flebotomi (Diptera: Psychodidae) [Evaluation of repellent and anti-feeding effect of garlic oil (Allium sativum) against the bite of phlebotomine sandflies Diptera: Psychodidae]. Ann. Ist. Super Sanita 2005, 41, 253–256. [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoobi-Ershadi, M.R.; Akhavan, A.; Jahanifard, E.; Vatandoost, H.; Amin, G.; Moosavi, L.; Zahraei Ramazani, A.R.; Abdoli, H.; Arandian, M.H. Repellency Effect of Myrtle Essential Oil and DEET against Phlebotomus papatasi, under Laboratory Conditions. Iran. J. Public Health 2006, 35, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nieves, E.; Fernández Méndez, J.; Lias, J.; Rondón, M.; Briceño, B. Actividad repelente de aceites esenciales contra las picaduras de Lutzomyia migonei (Diptera: Psychodidae) [Repellent activity of plant essential oils against bites of Lutzomyia migonei (Diptera: Psychodidae)]. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2010, 58, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, E.; Scorza, J.V. The use of lemon essential oil as a sandfly repellent. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1991, 85, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, Y.; Gebre-Michael, T.; Balkew, M. Laboratory and field evaluation of neem (Azadirachta indica A. Juss) and Chinaberry (Melia azedarach L.) oils as repellents against Phlebotomus orientalis and P. bergeroti (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 2010, 113, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimutai, A.; Ngeiywa, M.; Mulaa, M.; Njagi, P.G.; Ingonga, J.; Nyamwamu, L.B.; Ombati, C.; Ngumbi, P. Repellent effects of the essential oils of Cymbopogon citratus and Tagetes minuta on the sandfly, Phlebotomus duboscqi. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hicks, S.; Wang, M.; Doraiswamy, V.; Fry, K.; Wohlford, E.M. Neurodevelopmental delay diagnosis rates are increased in a region with aerial pesticide application. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silver, M.K.; Shao, J.; Zhu, B.; Chen, M.; Xi, Y.; Kaciroti, N.; Lozoff, B.; Meeker, J.D. Prenatal naled and chlorpyrifos exposure is associated with deficits in infant motor function in a cohort of Chinese infants. Environ. Int. 2017, 106, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benelli, G.; Pavela, R. Repellence of essential oils and selected compounds against ticks-A systematic review. Acta Trop. 2018, 179, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B.; Grieneisen, M.L. Botanical insecticide research: Many publications, limited useful data. Trends Plant. Sci. 2014, 19, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremichael Tedla, D.; Bariagabr, F.H.; Abreha, H.H. Incidence and Trends of Leishmaniasis and Its Risk Factors in Humera, Western Tigray. J. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 24, 8463097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, C.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.N. Visceral leishmaniasis in northwest China from 2004 to 2018: A spatio-temporal analysis. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 3, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, B.; Gebre-Mariam, T.; Asres, K. Mosquito repellent actions of the essential oils of Cymbopogon citratus, Cymbopogon nardus and Eucalyptus citriodora: Evaluation and formulation studies. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2012, 15, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.J.; Hill, N.; Ruiz, C.; Cameron, M.M. Field evaluation of tradition- ally used plant-based repellents and fumigants against the malaria vector Anopheles darlingi in Riberalta, Bolivian Amazon. J. Med. Entomol. 2007, 44, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trongtokit, Y.; Rongsriyam, Y.; Komalamisra, N.; Apiwathnasorn, C. Comparative repellency of 38 essential oils against mosquito bites. Phytother. Res. 2005, 19, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scientific Name | Common Name | Formulation | mg/mL or % | Efficacy after 72 h (%) | Study Type | Sand Fly Species | Leishmania Species | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Citrus medica | Green Lemon | Essential oil | 0.01 | 70% | Vivo | Lu. youngi | L. infantum | [49] |

| Citrus medica | Green Lemon | 0.01 | 78% | Vitro | Ph. papatasi | L. infantum | |||

| II | Azadiracha indica | Neem oil | Hexane-extracted oil | 5% | 100% | Vivo | Ph. papatasi | L. infantum | [44] |

| Azadiracha indica | Neem oil | 2% | 96.6% | ||||||

| III | Azadiracha indica | Neem oil | Hexane-extracted oil | 2% | 96.6% | Vivo | Ph. papatasi | L. infantum | [45] |

| IV | Azadiracha indica | Neem oil | Essential oil | 0.01 | 75% | Vitro | Ph. papatasi | L. infantum | [38] |

| 0.02 | 82% | ||||||||

| V | Antonia ovata | - | Aqueous extract | 223 | 80% | Vitro | Lu. longipalpis | L. infantum | [39] |

| Derris amazonica | - | 212 | 66.7% | ||||||

| VI | Allium sativum | Garlic | Essential oil | 0.005 | 40% | Vivo | Ph. papatasi | L. infantum | [46] |

| 0.01 | 65% | ||||||||

| 0.10 | 90% | ||||||||

| 1.00 | 95% | ||||||||

| VII | Mirtus communis | Myrtle | Essential oil | 1.9 | 62.2% | Vivo | Ph. papatasi | L. infantum | [47] |

| VIII | Azadirachta indica | Neem oil | Hexane-extracted oil | 2% | 96.28% | Vitro | Ph. orientalis | L. donovani | [50] |

| 5% | 98.26% | ||||||||

| Melia azedarach | Persian lilac oil | 2% | 95.13% | Vivo | |||||

| 5% | 96.20% | ||||||||

| 2% | 95% | Vitro | Ph. bergeroti | L. major | |||||

| Azadirachta indica | Neem oil | 5% | 95% | ||||||

| 2% | 92% | ||||||||

| 5% | 92% | ||||||||

| IX | Hyptis suaveolens | Pignut | Essential oil | n.r. | No efficacy | Vivo | Lu. migonei | L. infantum | [48] |

| Pimenta racemosa | West Indian bay tree | ||||||||

| Monticalia imbricatifolia | Saccoloma | ||||||||

| Espeletia schultzii | Frailejón | ||||||||

| Plectharanthus amboincus | Cuban oregano | ||||||||

| Piper marginatum | Cake bush | ||||||||

| Pseudognaphalium calciforum | Ladies’ tobacco | ||||||||

| Cinnamomun zeylancium | Cinnamon | ||||||||

| X | Eucalyptus staigeriana | Eucalyptus | Essential oil | 0.3 | 1.7% | Vitro | Lu. longipalpis | L. infantum | [40] |

| 0.6 | 11.7% | ||||||||

| 1.2 | 32.34% | ||||||||

| 2.5 | 65.81% | ||||||||

| 5 | 100% | ||||||||

| Eucalyptus citriodora | Lemon Scented eucalyptus | 2 | 7.1% | ||||||

| Eucalyptus globosus | Southern blue gum | 4 | 23.8% | ||||||

| 6 | 45.2% | ||||||||

| 8 | 70% | ||||||||

| 10 | 100% | ||||||||

| 2 | 3.1% | ||||||||

| Eucalyptus globosus | Southern blue gum | 4 | 10.6% | ||||||

| 6 | 25.8% | ||||||||

| 8 | 47.64% | ||||||||

| 10 | 96.47% | ||||||||

| XI | Tagetes minuta | Mexican marigold | Methanol extract | 2.5 | 50% | Vitro | Ph. duboscqi | L. major | [41] |

| 5 | 63% | ||||||||

| 10 | 100% | ||||||||

| Acalypha fruticosa | Birch-Leaved Cat Tail | Ethyl Acetate extract | 2.5 | 60% | |||||

| 5 | 48% | ||||||||

| 10 | 100% | ||||||||

| Tarchonanthus camphoratus | Camphor bush | Methanol extract | 2.5 | 10% | |||||

| 5 | 10% | ||||||||

| 10 | 20% | ||||||||

| XII | Monticalia greenmaniana | Saccoloma | Essential-oil | 0.001 | 95% | Vitro | Lu. migonei | L. infantum | [42] |

| 0.1 | 100% | ||||||||

| 0.2 | - | ||||||||

| 0.3 | - | ||||||||

| Methanol extract | 0.1 | 100% | |||||||

| 1 | 100% | ||||||||

| 10 | - | ||||||||

| 100 | - | ||||||||

| Aqueous extract | 0.1 | 100% | |||||||

| 1 | 100% | ||||||||

| 10 | - | ||||||||

| 100 | - | ||||||||

| XIII | Argeratina jahnii | Snakeroot | Methanol extract | 0.1/1/10 | No efficacy | Vitro | Lu. migonei | L. infantum | [43] |

| Aqueous extract | |||||||||

| Essential oil | 0.1 | 22% | |||||||

| 1 | 100% | ||||||||

| 10 | 100% | ||||||||

| Argeratina pichinchensis | Fragrant snakeroot | Methanol extract | |||||||

| Aqueous extract | |||||||||

| Essential oil | |||||||||

| XIV | Cymbopogon citratus | Lemon grass | Essential oil | 0.125 | 51.3% | Vitro | Ph. duboscqi | L. major | [51] |

| 0.25 | 59.1% | ||||||||

| 0.50 | 89.1% | ||||||||

| 0.75 | 87.7% | ||||||||

| 1.00 | 100% | ||||||||

| Tagetes minuta | Mexican marigold | 0.125 | 21.5% | ||||||

| 0.25 | 46.8% | ||||||||

| 0.50 | 52.2% | ||||||||

| 0.75 | 76% | ||||||||

| 1.00 | 88.9% |

| Family | Scientific Name | Number of Scientific Reports | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Amaryllidaceae | Allium sativum | 1 |

| II | Asteraceae | Monticalia imbricatifolia | 1 |

| Espeletia schultzii | 1 | ||

| Pseudognaphalium calciforum | 1 | ||

| Cinnamomun zeylancium | 1 | ||

| Tagetes minuta | 2 | ||

| Tarchonanthus camphoratus | 1 | ||

| Monticalia greenmaniana | 1 | ||

| Argeratina jahnii | 1 | ||

| Argeratina pichinchensis | 1 | ||

| III | Citrus | Citrus medica | 2 |

| IV | Euphorbiacee | Acalypha fruticosa | 1 |

| V | Labiatae | Plectharanthus amboincus | 1 |

| VI | Lamiaceae | Hyptis suaveolens | 1 |

| VII | Loganiacaceae | Antonia ovata | 1 |

| Derris amazonica | 1 | ||

| VIII | Meliacee | Melia azedarach | 2 |

| Azadirachta indica | 4 | ||

| IX | Myrtacae | Myrtus communis | 1 |

| Pimenta racemosa | 1 | ||

| Eucalyptus staigeriana | 1 | ||

| Eucalyptus citriodora | 1 | ||

| Eucalyptus globosus | 1 | ||

| X | Piperaceae | Piper marginatum | 1 |

| XI | Poaceae | Cymbopogon citratus | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pugliese, M.; Gaglio, G.; Passantino, A.; Brianti, E.; Napoli, E. Natural Products against Sand Fly Vectors of Leishmaniosis: A Systematic Review. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8080150

Pugliese M, Gaglio G, Passantino A, Brianti E, Napoli E. Natural Products against Sand Fly Vectors of Leishmaniosis: A Systematic Review. Veterinary Sciences. 2021; 8(8):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8080150

Chicago/Turabian StylePugliese, Michela, Gabriella Gaglio, Annamaria Passantino, Emanuele Brianti, and Ettore Napoli. 2021. "Natural Products against Sand Fly Vectors of Leishmaniosis: A Systematic Review" Veterinary Sciences 8, no. 8: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8080150

APA StylePugliese, M., Gaglio, G., Passantino, A., Brianti, E., & Napoli, E. (2021). Natural Products against Sand Fly Vectors of Leishmaniosis: A Systematic Review. Veterinary Sciences, 8(8), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8080150