Looking inside Mexican Traditional Food as Sources of Synbiotics for Developing Novel Functional Products

Abstract

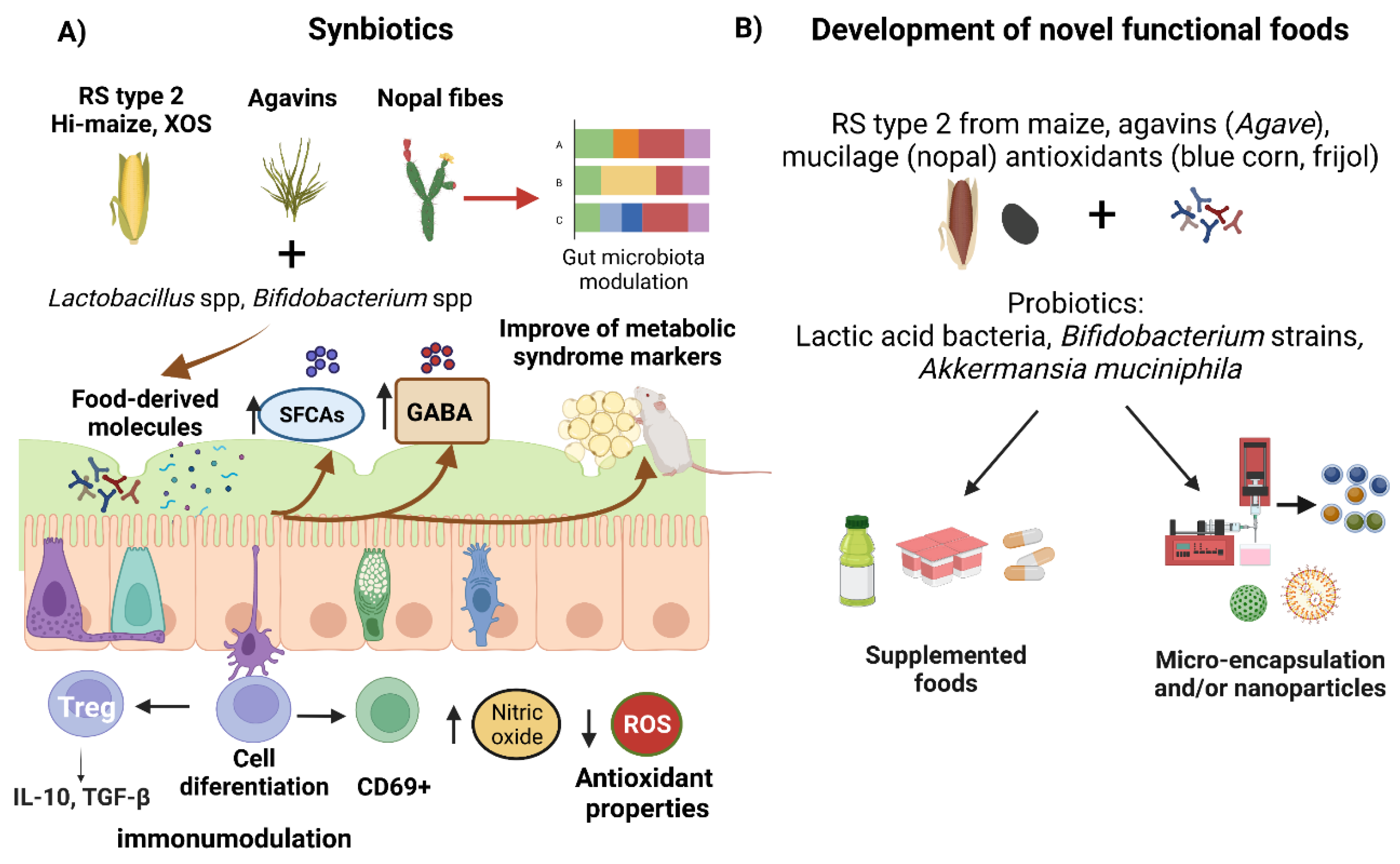

:1. Introduction

2. Maize

2.1. Prebiotics in Maize

2.2. Probiotic Candidates in Maize-Based Fermented Foods

2.3. Synbiotic Effects of Maize

3. Agave

3.1. Derived Prebiotics from Agave

3.2. Probiotics from Agave Sources

3.3. Synbiotic Effects of Agave

4. Nopal

4.1. Prebiotic Effect in Nopal

4.2. Synbiotic Effects in Nopal

5. Beans

Prebiotic Effect in Beans

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schiffrin, E.J.; Thomas, D.R.; Kumar, V.B.; Brown, C.; Hager, C.; Van’t Hof, M.A.; Morley, J.E.; Guigoz, Y. Systemic inflammatory markers in older persons: The effect of oral nutritional supplementation with prebiotics. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2007, 11, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Swanson, K.S.; Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Reimer, R.A.; Reid, G.; Verbeke, K.; Scott, K.P.; Holscher, H.D.; Azad, M.B.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of synbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho-Wells, A.L.; Helmolz, K.; Nodet, C.; Molzer, C.; Leonard, C.; McKevith, B.; Thielecke, F.; Jackson, K.G.; Tuohy, K.M. Determination of the in vivo prebiotic potential of a maize-based whole grain breakfast cereal: A human feeding study. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nogal, A.; Valdes, A.M.; Menni, C. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between gut microbiota and diet in cardio-metabolic health. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, M.T.; Cresci, G.A.M. The Immunomodulatory Functions of Butyrate. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 6025–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada Venegas, D.; De la Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; González, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Komiyama, Y.; Andoh, A.; Fujiwara, D.; Ohmae, H.; Araki, Y.; Fujiyama, Y.; Mitsuyama, K.; Kanauchi, O. New prebiotics from rice bran ameliorate inflammation in murine colitis models through the modulation of intestinal homeostasis and the mucosal immune system. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 46, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, I.C.; Shang, H.F.; Lin, T.F.; Wang, T.H.; Lin, H.S.; Lin, S.H. Effect of fermented soy milk on the intestinal bacterial ecosystem. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 1225–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Hospattankar, A.; Deng, P.; Swanson, K.; Slavin, J. Prebiotic Effects and Fermentation Kinetics of Wheat Dextrin and Partially Hydrolyzed Guar Gum in an In Vitro Batch Fermentation System. Foods 2015, 4, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zizumbo-Villarreal, D.; Flores-Silva, A.; Colunga-García Marín, P. The Archaic Diet in Mesoamerica: Incentive for Milpa Development and Species Domestication. Econ. Bot. 2012, 66, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritsema, T.; Smeekens, S. Fructans: Beneficial for plants and humans. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003, 6, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stintzing, F.C.; Carle, R. Cactus stems (Opuntia spp.): A review on their chemistry, technology, and uses. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayamanohar, J.; Devi, P.B.; Kavitake, D.; Priyadarisini, V.B.; Shetty, P.H. Prebiotic potential of water extractable polysaccharide from red kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). LWT 2019, 101, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Sotero, M.Y.; Cruz-Hernández, C.D.; Trujillo-Carretero, C.; Rodríguez-Dorantes, M.; García-Galindo, H.S.; Chávez-Servia, J.L.; Oliart-Ros, R.M.; Guzmán-Gerónimo, R.I. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of blue corn and tortilla from native maize. Chem. Cent. J. 2017, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres-Maravilla, E.; Lenoir, M.; Mayorga-Reyes, L.; Allain, T.; Sokol, H.; Langella, P.; Sánchez-Pardo, M.E.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G. Identification of novel anti-inflammatory probiotic strains isolated from pulque. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Delgado, N.C.; Torres-Maravilla, E.; Mayorga-Reyes, L.; Martín, R.; Langella, P.; Pérez-Pastén-Borja, R.; Sánchez-Pardo, M.E.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Probiotic Candidate Strains Isolated during Fermentation of Agave (Agave angustifolia Haw). Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Armendáriz, B.; Cardoso-Ugarte, G.A. Traditional fermented beverages in Mexico: Biotechnological, nutritional, and functional approaches. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyuan, S.; Tong, L.; Liu, R. Corn phytochemicals and their health benefits. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2018, 7, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttie, J.M.; Reynolds, S.G. Fodder Oats: A World Overview; Food & Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- de la Parra, C.; Serna Saldivar, S.O.; Liu, R.H. Effect of Processing on the Phytochemical Profiles and Antioxidant Activity of Corn for Production of Masa, Tortillas, and Tortilla Chips. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4177–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwirtz, J.A.; Garcia-Casal, M.N. Processing maize flour and corn meal food products. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1312, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serna-Saldivar, S.O.; Rooney, L.W. Chapter 13—Industrial Production of Maize Tortillas and Snacks. In Tortillas; Serna-Saldivar, S.O., Rooney, L.W., Eds.; AACC International Press: St Paul, MN, USA, 2015; pp. 247–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ribas-Agustí, A.; Martin-Belloso, O.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Elez-Martinez, P. Food processing strategies to enhance phenolic compounds bioaccessibility and bioavailability in plant-based foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 58, 2531–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colin, C.; Virgen-Ortíz, J.; Serrano-Rubio, L.; Martinez-Tellez, M.; Astier, M. Comparison of nutritional properties and bioactive compounds between industrial and artisan fresh tortillas from maize landraces. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2020, 3, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Guerin, M.; Souidi, K.; Remize, F. Lactic Fermented Fruit or Vegetable Juices: Past, Present and Future. Beverages 2020, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malunga, L.N.; Beta, T. Isolation and identification of feruloylated arabinoxylan mono- and oligosaccharides from undigested and digested maize and wheat. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laffin, M.R.; Tayebi Khosroshahi, H.; Park, H.; Laffin, L.J.; Madsen, K.; Kafil, H.S.; Abedi, B.; Shiralizadeh, S.; Vaziri, N.D. Amylose resistant starch (HAM-RS2) supplementation increases the proportion of Faecalibacterium bacteria in end-stage renal disease patients: Microbial analysis from a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Hemodial. International. Int. Symp. Home Hemodial. 2019, 23, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barczyńska, R.; Litwin, M.; Sliżewska, K.; Szalecki, M.; Berdowska, A.; Bandurska, K.; Libudzisz, Z.; Kapuśniak, J. Bacterial Microbiota and Fatty Acids in the Faeces of Overweight and Obese Children. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paz-Samaniego, R.; Sotelo-Cruz, N.; Marquez-Escalante, J.; Rascon-Chu, A.; Campa-Mada, A.C.; Carvajal-Millan, E. Chapter 18—Nixtamalized Maize Flour By-product as a Source of Health-Promoting Ferulated Arabinoxylans (AX). In Flour and Breads and their Fortification in Health and Disease Prevention, 2nd ed.; Preedy, V.R., Watson, R.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 225–235. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-López, A.L.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Micard, V.; Rascón-Chu, A.; Brown-Bojorquez, F.; Sotelo-Cruz, N.; López-Franco, Y.L.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J. In vitro degradation of covalently cross-linked arabinoxylan hydrogels by bifidobacteria. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 144, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yin, J.; Li, L.; Luan, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, C.; Li, S. Prebiotic Potential of Xylooligosaccharides Derived from Corn Cobs and Their In Vitro Antioxidant Activity When Combined with Lactobacillus. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Broekaert, W.F.; Courtin, C.M.; Verbeke, K.; Van de Wiele, T.; Verstraete, W.; Delcour, J.A. Prebiotic and Other Health-Related Effects of Cereal-Derived Arabinoxylans, Arabinoxylan-Oligosaccharides, and Xylooligosaccharides. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Navarro, A.; Villalva Fuentes, B. Estudio del Potencial Probiótico de Bacterias ácido Lácticas Aisladas del Pozol; National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM): Mexico City, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Väkeväinen, K.; Hernández, J.; Simontaival, A.-I.; Severiano-Pérez, P.; Díaz-Ruiz, G.; von Wright, A.; Wacher-Rodarte, C.; Plumed-Ferrer, C. Effect of different starter cultures on the sensory properties and microbiological quality of Atole agrio, a fermented maize product. Food Control 2020, 109, 106907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cataluña, A.; Elizaquivel, P.; Carrasco, P.; Espinosa-Moreno, J.; Reyes-Duarte, D.; Wacher, C.; Aznar, R. Diversity and dynamics of lactic acid bacteria in Atole agrio, a traditional maize-based fermented beverage from South-Eastern Mexico, analysed by high throughput sequencing and culturing. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2018, 111, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-Castillo, Á.E.; Méndez-Romero, J.I.; Reyes-Díaz, R.; Santiago-López, L.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Hernández-Mendoza, A.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S.G.; González-Córdova, A.F. Tejuino, a Traditional Fermented Beverage: Composition, Safety Quality, and Microbial Identification. Foods 2021, 10, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.S.; Ramos, C.L.; González-Avila, M.; Gschaedler, A.; Arrizon, J.; Schwan, R.F.; Dias, D.R. Probiotic properties of Weissella cibaria and Leuconostoc citreum isolated from tejuino—A typical Mexican beverage. LWT 2017, 86, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Leu, R.K.; Hu, Y.; Brown, I.L.; Woodman, R.J.; Young, G.P. Synbiotic intervention of Bifidobacterium lactis and resistant starch protects against colorectal cancer development in rats. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiennimitr, P.; Yasom, S.; Tunapong, W.; Chunchai, T.; Wanchai, K.; Pongchaidecha, A.; Lungkaphin, A.; Sirilun, S.; Chaiyasut, C.; Chattipakorn, N.; et al. Lactobacillus paracasei HII01, xylooligosaccharides, and synbiotics reduce gut disturbance in obese rats. Nutrition 2018, 54, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costabile, A.; Bergillos-Meca, T.; Rasinkangas, P.; Korpela, K.; de Vos, W.M.; Gibson, G.R. Effects of Soluble Corn Fiber Alone or in Synbiotic Combination with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and the Pilus-Deficient Derivative GG-PB12 on Fecal Microbiota, Metabolism, and Markers of Immune Function: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study in Healthy Elderly (Saimes Study). Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Santos, A.M.; Sugizaki, C.S.A.; Lima, G.C.; Naves, M.M.V. Prebiotic effect of dietary polyphenols: A systematic review. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 74, 104169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacher, C.; Cañas, A.; Bárzana, E.; Lappe, P.; Ulloa, M.; Owens, J.D. Microbiology of Indian and Mestizo pozol fermentations. Food Microbiol. 2000, 17, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ben Omar, N.; Ampe, F. Microbial community dynamics during production of the Mexican fermented maize dough pozol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 3664–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Díaz-Ruiz, G.; Guyot, J.P.; Ruiz-Teran, F.; Morlon-Guyot, J.; Wacher, C. Microbial and physiological characterization of weakly amylolytic but fast-growing lactic acid bacteria: A functional role in supporting microbial diversity in pozol, a Mexican fermented maize beverage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 4367–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Soro-Yao, A.A.; Brou, K.; Amani, G.; Thonart, P.; Djè, K.M. The Use of Lactic Acid Bacteria Starter Cultures during the Processing of Fermented Cereal-based Foods in West Africa: A Review. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2014, 25, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tetreault, D.; McCulligh, C.; Lucio, C. Distilling agro-extractivism: Agave and tequila production in Mexico. J. Agrar. Chang. 2021, 21, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez-Covarrubias, G.; Díaz-Teres, R.; Sanjuan-Dueñas, R.; Anzaldo-Hernández, J.; Rowell, R.M. Utilization of by-products from the tequila industry. Part 2: Potential value of Agave tequilana Weber azul leaves. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 77, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escobedo-García, S.; Salas-Tovar, J.A.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; González-Montemayor, Á.M.; López, M.G.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R. Functionality of Agave Bagasse as Supplement for the Development of Prebiotics-Enriched Foods. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2020, 75, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava-Cruz, N.Y.; Medina-Morales, M.A.; Martinez, J.L.; Rodriguez, R.; Aguilar, C.N. Agave biotechnology: An overview. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2015, 35, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Zavala, A.; Juárez-Flores, B.I.; Pinos-Rodríguez, J.M.; Delgado-Portales, R.E.; Aguirre-Rivera, J.R.; Alcocer-Gouyonnet, F. Prebiotic Effects of Agave salmiana Fructans in Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis Cultures. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1985–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jonova, S.; Ilgaza, A.; Zolovs, M. The Impact of Inulin and a Novel Synbiotic (Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strain 1026 and Inulin) on the Development and Functional State of the Gastrointestinal Canal of Calves. Vet. Med. Int. 2021, 2021, 8848441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, S.; Salem, H. Effect of oral administration of Agave americana or Quillaja saponaria extracts on digestion and growth of Barbarine female lamb. Livest. Sci. 2012, 147, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, A.; Giles-Gómez, M.; Hernández, G.; Córdova-Aguilar, M.S.; López-Munguía, A.; Gosset, G.; Bolívar, F. Analysis of bacterial community during the fermentation of pulque, a traditional Mexican alcoholic beverage, using a polyphasic approach. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 124, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles-Gómez, M.; Sandoval García, J.G.; Matus, V.; Campos Quintana, I.; Bolívar, F.; Escalante, A. In vitro and in vivo probiotic assessment of Leuconostoc mesenteroides P45 isolated from pulque, a Mexican traditional alcoholic beverage. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velázquez-Martínez, J.R.; González-Cervantes, R.M.; Hernández-Gallegos, M.A.; Mendiola, R.C.; Aparicio, A.R.J.; Ocampo, M.L.A. Prebiotic Potential of Agave angustifolia Haw Fructans with Different Degrees of Polymerization. Molecules 2014, 19, 12660–12675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huazano-García, A.; López, M.G. Agavins reverse the metabolic disorders in overweight mice through the increment of short chain fatty acids and hormones. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 3720–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Contreras, A.A.; Vásquez Garibay, E.M.; Sánchez Ramírez, C.A.; Fafutis Morris, M.; Delgado Rizo, V. Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 and Agave Inulin in Children with Cerebral Palsy and Chronic Constipation: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catry, E.; Bindels, L.B.; Tailleux, A.; Lestavel, S.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Goossens, J.F.; Lobysheva, I.; Plovier, H.; Essaghir, A.; Demoulin, J.B.; et al. Targeting the gut microbiota with inulin-type fructans: Preclinical demonstration of a novel approach in the management of endothelial dysfunction. Gut 2018, 67, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, T.; Papadopoulou, K.K.; Osbourn, A. Metabolic and functional diversity of saponins, biosynthetic intermediates and semi-synthetic derivatives. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 49, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allsopp, P.; Possemiers, S.; Campbell, D.; Oyarzábal, I.S.; Gill, C.; Rowland, I. An exploratory study into the putative prebiotic activity of fructans isolated from Agave angustifolia and the associated anticancer activity. Anaerobe 2013, 22, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição Apolinário, A.; Silva Vieira, A.D.; Marta Isay Saad, S.; Converti, A.; Pessoa, A., Jr.; da Silva, J.A. Aqueous extracts of Agave sisalana boles have prebiotic potential. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 2367–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Velázquez, D.C.; Monribot-Villanueva, J.L.; Bourdon, M.; Tang, J.Z.; López-Rosas, I.; Maceda-López, L.F.; Villalpando-Aguilar, J.L.; Rodríguez-López, L.; Gauthier, A.; Trejo, L.; et al. Unravelling Chemical Composition of Agave Spines: News from Agave fourcroydes Lem. Plants 2020, 9, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, C.R.; Humberto, H.S.; Jorge, Y.F. Probiotic Properties of Leuconostoc mesenteroides Isolated from Aguamiel of Agave salmiana. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2015, 7, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Rodríguez, D.C.; Juárez-Pilares, G.; Cano-Cano, L.; Pérez-Sánchez, M.; Ibáñez, C.A.; Reyes-Castro, L.A.; Yáñez-Fernández, J.; Zambrano, E. Impact of Leuconostoc SD23 intake in obese pregnant rats: Benefits for maternal metabolism. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2020, 11, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Vilet, L.; Garcia-Hernandez, M.H.; Delgado-Portales, R.E.; Corral-Fernandez, N.E.; Cortez-Espinosa, N.; Ruiz-Cabrera, M.A.; Portales-Perez, D.P. In vitro assessment of agave fructans (Agave salmiana) as prebiotics and immune system activators. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 63, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villagrán-de la Mora, Z.; Vázquez-Paulino, O.; Avalos, H.; Ascencio, F.; Nuño, K.; Villarruel-López, A. Effect of a Synbiotic Mix on Lymphoid Organs of Broilers Infected with Salmonella typhimurium and Clostridium perfringens. Animals 2020, 10, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperno, D.R. The Origins of Plant Cultivation and Domestication in the New World Tropics: Patterns, Process, and New Developments. Curr. Anthropol. 2011, 52, S453–S470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, D.; Tesoriere, L.; Di Gaudio, F.; Bongiorno, A.; Allegra, M.; Pintaudi, A.M.; Kohen, R.; Livrea, M.A. Antioxidant Activities of Sicilian Prickly Pear (Opuntia ficus indica) Fruit Extracts and Reducing Properties of Its Betalains: Betanin and Indicaxanthin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6895–6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avila-Nava, A.; Calderón-Oliver, M.; Medina-Campos, O.N.; Zou, T.; Gu, L.; Torres, N.; Tovar, A.R.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Extract of cactus (Opuntia ficus indica) cladodes scavenges reactive oxygen species in vitro and enhances plasma antioxidant capacity in humans. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 10, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kossori, R.L.; Villaume, C.; El Boustani, E.; Sauvaire, Y.; Méjean, L. Composition of pulp, skin and seeds of prickly pears fruit (Opuntia ficus indica sp.). Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 1998, 52, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassar, A.G. Chemical composition and functional properties of prickly pear (Opuntia ficus indica) seeds flour and protein concentrate. World J. Dairy Food Sci. 2008, 3, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- de Sahagún, B. Códice Florentino de Fray Bernardino de Sahagún; Imp. Talleres Casa Editorial Giunti Barberá: Mexico City, Mexico, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Torres, L.; Brito-De La Fuente, E.; Torrestiana-Sanchez, B.; Katthain, R. Rheological properties of the mucilage gum (Opuntia ficus indica). Food Hydrocoll. 2000, 14, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachtenberg, S.; Mayer, A.M. Composition and properties of Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage. Phytochemistry 1981, 20, 2665–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goycoolea, F.M.; Cárdenas, A. Pectins from Opuntia spp.: A Short Review. J. Prof. Assoc. Cactus Dev. 2003, 5, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Trombetta, D.; Puglia, C.; Perri, D.; Licata, A.; Pergolizzi, S.; Lauriano, E.R.; De Pasquale, A.; Saija, A.; Bonina, F.P. Effect of polysaccharides from Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) cladodes on the healing of dermal wounds in the rat. Phytomedicine 2006, 13, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galati, E.M.; Mondello, M.R.; Lauriano, E.R.; Taviano, M.F.; Galluzzo, M.; Miceli, N. Opuntia ficus indica (L.) Mill. fruit juice protects liver from carbon tetrachloride-induced injury. Phytother. Res. Int. J. Devoted Pharmacol. Toxicol. Eval. Nat. Prod. Deriv. 2005, 19, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspinall, G.O. 12—Chemistry of Cell Wall Polysaccharides. In Carbohydrates: Structure and Function; Preiss, J., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 473–500. [Google Scholar]

- So, D.; Whelan, K.; Rossi, M.; Morrison, M.; Holtmann, G.; Kelly, J.T.; Shanahan, E.R.; Staudacher, H.M.; Campbell, K.L. Dietary fiber intervention on gut microbiota composition in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Remes-Troche, J.M.; Taboada-Liceaga, H.; Gill, S.; Amieva-Balmori, M.; Rossi, M.; Hernández-Ramírez, G.; García-Mazcorro, J.F.; Whelan, K. Nopal fiber (Opuntia ficus-indica) improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome in the short term: A randomized controlled trial. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 33, e13986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Ramos, S.; Avila-Nava, A.; Tovar, A.R.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; López-Romero, P.; Torres, N. Opuntia ficus indica (Nopal) Attenuates Hepatic Steatosis and Oxidative Stress in Obese Zucker (fa/fa) Rats. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1956–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- López-Romero, P.; Pichardo-Ontiveros, E.; Avila-Nava, A.; Vázquez-Manjarrez, N.; Tovar, A.R.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Torres, N. The Effect of Nopal (Opuntia Ficus Indica) on Postprandial Blood Glucose, Incretins, and Antioxidant Activity in Mexican Patients with Type 2 Diabetes after Consumption of Two Different Composition Breakfasts. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 1811–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Vela, J.; Totosaus, A.; Cruz-Guerrero, A.E.; de Lourdes Pérez-Chabela, M. In vitro evaluation of the fermentation of added-value agroindustrial by-products: Cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) peel and pineapple (Ananas comosus) peel as functional ingredients. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Matadamas, A.; Mayorga-Reyes, L.; Pérez-Chabela, M.d.L. In vitro fermentation of agroindustrial by-products: Grapefruit albedo and peel, cactus pear peel and pineapple peel by lactic acid bacteria. J. Int. Food Res. J. 2015, 22, 859–865. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Chabela, M.L.; Cerda-Tapia, A.; Diaz-Vela, J.; Claudia Delgadillo, P.; Margarita Diaz, M.; Aleman, G. Physiological Effects of Agroindustrial Co-Products: Cactus (Opuntia ficus) Pear Peel Flour and Stripe Apple (Malus domestica) Marc Flour on Wistar Rats (Rattus norvegicus). Pak. J. Nutr. 2015, 14, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panda, S.K.; Behera, S.K.; Witness Qaku, X.; Sekar, S.; Ndinteh, D.T.; Nanjundaswamy, H.M.; Ray, R.C.; Kayitesi, E. Quality enhancement of prickly pears (Opuntia sp.) juice through probiotic fermentation using Lactobacillus fermentum—ATCC 9338. LWT 2017, 75, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou-Idra, M.; Ed-Dra, A.; Rhazi Filali, F.; Bahri, H.; Bebtayeb, A. Phytochemistry and Stimulatory Effect of Probiotic Micro-Organisms of the Fruit Of Opuntia Ficus Indica from the Region of Meknes (Morocco). Eur. J. Sci. Res. 2016, 139, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara-Arauza, J.C.; Jesús Ornelas-Paz, J.; Pimentel-González, D.J.; Rosales Mendoza, S.; Soria Guerra, R.E.; Paz Maldonado, L.M.T. Prebiotic effect of mucilage and pectic-derived oligosaccharides from nopal (Opuntia ficus-indica). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 21, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Tapia, M.; Aguilar-López, M.; Pérez-Cruz, C.; Pichardo-Ontiveros, E.; Wang, M.; Donovan, S.M.; Tovar, A.R.; Torres, N. Nopal (Opuntia ficus indica) protects from metabolic endotoxemia by modifying gut microbiota in obese rats fed high fat/sucrose diet. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran-Ramos, S.; He, X.; Chin, E.L.; Tovar, A.R.; Torres, N.; Slupsky, C.M.; Raybould, H.E. Nopal feeding reduces adiposity, intestinal inflammation and shifts the cecal microbiota and metabolism in high-fat fed rats. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Casas, V.; Pérez-Chabela, M.L.; Cortés-Barberena, E.; Totosaus, A. Improvement of lactic acid bacteria viability in acid conditions employing agroindustrial co-products as prebiotic on alginate ionotropic gel matrix co-encapsulation. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 38, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Vela, J.; Totosaus, A.; Pérez-Chabela, M. Integration of Agroindustrial Co-Products as Functional Food Ingredients: Cactus Pear (Opuntia Ficus Indica) Flour and Pineapple (Ananas Comosus) Peel Flour as Fiber Source in Cooked Sausages Inoculated with Lactic Acid Bacteria. J. Food Processing Preserv. 2015, 39, 2630–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán-Martínez, L.P.; Totosaus, A.; de Lourdes Pérez-Chabela, M. Probiotication of cooked sausages employing agroindustrial coproducts as prebiotic co-encapsulant in ionotropic alginate–pectin gels. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verón, H.E.; Di Risio, H.D.; Isla, M.I.; Torres, S. Isolation and selection of potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria from Opuntia ficus-indica fruits that grow in Northwest Argentina. LWT 2017, 84, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verón, H.E.; Gauffin Cano, P.; Fabersani, E.; Sanz, Y.; Isla, M.I.; Fernández Espinar, M.T.; Gil Ponce, J.V.; Torres, S. Cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) juice fermented with autochthonous Lactobacillus plantarum S-811. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filannino, P.; Cavoski, I.; Thligene, N.; Vincentini, O.; De Angelis, M.; Silano, M.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R. Correction: Lactic Acid Fermentation of Cactus Cladodes (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) Generates Flavonoid Derivatives with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Cagno, R.; Filannino, P.; Vincentini, O.; Lanera, A.; Cavoski, I.; Gobbetti, M. Exploitation of Leuconostoc mesenteroides strains to improve shelf life, rheological, sensory and functional features of prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) fruit puree. Food Microbiol. 2016, 59, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellanos, J.Z.; Guzmán Maldonado, H.; Jiménez, A.; Mejía, C.; Muñoz Ramos, J.J.; Acosta Gallegos, J.A.; Hoyos, G.; López Salinas, E.; González Eguiarte, D.; Salinas Pérez, R.; et al. [Preferential habits of consumers of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Mexico]. Arch. Latinoam. De Nutr. 1997, 47, 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, S.V.; Winham, D.M.; Hutchins, A.M. Bean and rice meals reduce postprandial glycemic response in adults with type 2 diabetes: A cross-over study. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Z.; Jiang, W.; Thompson, H.J. Edible dry bean consumption (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) modulates cardiovascular risk factors and diet-induced obesity in rats and mice. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S66–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borresen, E.C.; Brown, D.G.; Harbison, G.; Taylor, L.; Fairbanks, A.; O’Malia, J.; Bazan, M.; Rao, S.; Bailey, S.M.; Wdowik, M.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Increase Navy Bean or Rice Bran Consumption in Colorectal Cancer Survivors. Nutr. Cancer 2016, 68, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tucker, L.A. Bean Consumption Accounts for Differences in Body Fat and Waist Circumference: A Cross-Sectional Study of 246 Women. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 2020, 9140907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Tapia, M.; Hernández-Velázquez, I.; Pichardo-Ontiveros, E.; Granados-Portillo, O.; Gálvez, A.; Tovar, A.R.; Torres, N. Consumption of Cooked Black Beans Stimulates a Cluster of Some Clostridia Class Bacteria Decreasing Inflammatory Response and Improving Insulin Sensitivity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oomah, B.D.; Cardador-Martínez, A.; Loarca-Piña, G. Phenolics and antioxidative activities in common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Fernández, X.; Manzo-Bonilla, L.; Loarca-Piña, G.F. Comparison of Antimutagenic Activity of Phenolic Compounds in Newly Harvested and Stored Common Beans Phaseolus vulgaris against Aflatoxin B1. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, S73–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Lafuente, A.; Moro, C.; Manchón, N.; Gonzalo-Ruiz, A.; Villares, A.; Guillamón, E.; Rostagno, M.; Mateo-Vivaracho, L. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of phenolic rich extracts from white and red common beans. Food Chem. 2014, 161, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.-Q.; Gan, R.-Y.; Ge, Y.-Y.; Zhang, D.; Corke, H. Polyphenols in Common Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): Chemistry, Analysis, and Factors Affecting Composition. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 1518–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kotue, T.; Josephine, M.; Wirba, L.; Nkenmeni, D.; Kwuimgoin; Wnb, D.; Kansci; Fokou; Fokam, D. Nutritional properties and nutrients chemical analysis of common beans seed. MOJ Biol. Med. 2018, 3, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Landa-Habana, L.; Piña-Hernández, A.; Agama-Acevedo, E.; Tovar, J.; Bello-Pérez, L.A. Effect of cooking procedures and storage on starch bioavailability in common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2004, 59, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva, N.; Thavarajah, P.; Thavarajah, D. Prebiotic carbohydrate concentrations of common bean and chickpea change during cooking, cooling, and reheating. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henningsson, A.M.; Nyman, E.M.; Björck, I.M. Content of short-chain fatty acids in the hindgut of rats fed processed bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) flours varying in distribution and content of indigestible carbohydrates. Br. J. Nutr. 2001, 86, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campos-Vega, R.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Pedraza-Aboytes, G.; Acosta-Gallegos, J.A.; Guzman-Maldonado, S.H.; Paredes-Lopez, O.; Oomah, B.D.; Loarca-Piña, G. Chemical Composition and In Vitro Polysaccharide Fermentation of Different Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, T59–T65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Bravo, R.; Guevara-Gonzalez, R.; Ramos-Gómez, M.; Garcia Gasca, T.; Campos-Vega, R.; Oomah, B.D. Fermented Nondigestible Fraction from Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Cultivar Negro 8025 Modulates HT-29 Cell Behavior. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, T41–T47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.M.; Kolba, N.; Hart, J.J.; Ma, M.; Sha, S.T.; Lakshmanan, N.; Nutti, M.R.; Martino, H.S.D.; Glahn, R.P.; Tako, E. Soluble extracts from carioca beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) affect the gut microbiota and iron related brush border membrane protein expression in vivo (Gallus gallus). Food Res. Int. 2019, 123, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, B.A.; Lu, P.; Alake, S.E.; Keirns, B.; Anderson, K.; Gallucci, G.; Hart, M.D.; El-Rassi, G.D.; Ritchey, J.W.; Chowanadisai, W.; et al. Pinto beans modulate the gut microbiome, augment MHC II protein, and antimicrobial peptide gene expression in mice fed a normal or western-style diet. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021, 88, 108543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finley, J.W.; Burrell, J.B.; Reeves, P.G. Pinto Bean Consumption Changes SCFA Profiles in Fecal Fermentations, Bacterial Populations of the Lower Bowel, and Lipid Profiles in Blood of Humans. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2391–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Vega, R.; García-Gasca, T.; Guevara-Gonzalez, R.; Ramos-Gomez, M.; Oomah, B.D.; Loarca-Piña, G. Human gut flora-fermented nondigestible fraction from cooked bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) modifies protein expression associated with apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and proliferation in human adenocarcinoma colon cancer cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 12443–12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jew, S.; AbuMweis, S.S.; Jones, P.J. Evolution of the human diet: Linking our ancestral diet to modern functional foods as a means of chronic disease prevention. J. Med. Food 2009, 12, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Calderón, A.K.; García-Flores, N.A.; Elizondo-Rodríguez, A.S.; Zavala-López, M.; García-Lara, S.; Ponce-García, N.; Escalante-Aburto, A. Effect of the Addition of Different Vegetal Mixtures on the Nutritional, Functional, and Sensorial Properties of Snacks Based on Pseudocereals. Foods 2021, 10, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Rivas, E.; Espinoza-Ortega, A.; Martínez-García, C.G.; Moctezuma-Pérez, S.; Thomé-Ortiz, H. Exploring the perception of Mexican urban consumers toward functional foods using the Free Word Association technique. J. Sens. Stud. 2018, 33, e12439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez-Bazán, M.; Castillo-Herrera, G.A.; Urias-Silvas, J.E.; Escobedo-Reyes, A.; Estarrón-Espinosa, M. Hunting Bioactive Molecules from the Agave Genus: An Update on Extraction and Biological Potential. Molecules 2021, 26, 6789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stintzing, F.C.; Herbach, K.M.; Mosshammer, M.R.; Carle, R.; Yi, W.; Sellappan, S.; Akoh, C.C.; Bunch, R.; Felker, P. Color, betalain pattern, and antioxidant properties of cactus pear (Opuntia spp.) clones. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña Cerino, J.M.; Peniche Pavía, H.A.; Tiessen, A.; Gurrola Díaz, C.M. Pigmented Maize (Zea mays L.) Contains Anthocyanins with Potential Therapeutic Action Against Oxidative Stress—A Review. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2020, 70, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-Y.; Kim, H.-W.; Li, H.; Lee, D.-C.; Rhee, H.-I. Antioxidative effect of purple corn extracts during storage of mayonnaise. Food Chem. 2014, 152C, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anhê, F.F.; Roy, D.; Pilon, G.; Dudonné, S.; Matamoros, S.; Varin, T.V.; Garofalo, C.; Moine, Q.; Desjardins, Y.; Levy, E.; et al. A polyphenol-rich cranberry extract protects from diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance and intestinal inflammation in association with increased Akkermansia spp. population in the gut microbiota of mice. Gut 2015, 64, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vogt, L.; Meyer, D.; Pullens, G.; Faas, M.M.; Smelt, M.J.; Venema, K.; Ramasamy, U.; Schols, H.A.; Vos, P.d. Immunological Properties of Inulin-Type Fructans. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 414–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reyes-Buendía, C.; Corrales Garcia, J.; Peña, C.; Hernandez-Montes, A.; Moncada, M. Sopa de elote (Zea mays) tipo crema con mucílago de nopal (Opuntia spp.) como espesante, sus características físicas y aceptación sensorial. TIP Rev. Espec. En Cienc. Químico-Biol. 2020, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara-Arauza, J.C.; Órnelas Paz, J.d.J.; Mendoza, S.R.; Guerra, R.E.S.; Paz Maldonado, L.M.T.; González, D.J.P. Biofunctional activity of tortillas and bars enhanced with nopal. Preliminary assessment of functional effect after intake on the oxidative status in healthy volunteers. Chem. Cent. J. 2011, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez Sánchez, R.E.; Ortiz-Rodríguez, R.; Aguilar-Barrera, J.L.; Valdéz-Alarcón, J.J.; Val- Arreola, D.; Esquivel-Córdoba, J.; Martínez-Flores, H.E. Effect of adding mucilage from Opuntia ficus-indica and Opuntia atropes to raw milk on mesophilic aerobic bacteria and total coliforms. Nova Sci. 2016, 8, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Chabela, M.L.; Totosaus, A. Opuntia Pear Peel as a Source of Functional Ingredients and Their Utilization in Meat Products. In Opuntia spp.: Chemistry, Bioactivity and Industrial Applications; Ramadan, M.F., Ayoub, T.E.M., Rohn, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 621–633. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Andrade, A.I.; García Chávez, E.; Rivera Bautista, C.; Oros Ovalle, C.; Ruiz Cabrera, M.A.; Grajales Lagunes, A. Influence of Prebiotic Activity of Agave salmiana Fructans on Mucus Production and Morphology Changes in Colonic Epithelium Cell of Healthy Wistar Rats. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 717460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gutierrez, F.; Ratering, S.; Juárez-Flores, B.; Godinez-Hernandez, C.; Geissler-Plaum, R.; Prell, F.; Zorn, H.; Czermak, P.; Schnell, S. Potential use of Agave salmiana as a prebiotic that stimulates the growth of probiotic bacteria. LWT 2017, 84, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ramos, L.; GarcÍa-Mateos, R.; Ybarra-Moncada, M.C.; Colinas-LeÓN, M.T. Nutritional value and antioxidant activity of the maguey syrup (Agave salmiana and A. mapisaga) obtained through three treatments. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2020, 48, 1306–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, N.; Boy, E.; Wirth, J.P.; Hurrell, R.F. Review: The potential of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) as a vehicle for iron biofortification. Nutrients 2015, 7, 1144–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luzardo-Ocampo, I.; Campos-Vega, R.; Cuellar-Nuñez, M.L.; Vázquez-Landaverde, P.A.; Mojica, L.; Acosta-Gallegos, J.A.; Loarca-Piña, G. Fermented non-digestible fraction from combined nixtamalized corn (Zea mays L.)/cooked common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) chips modulate anti-inflammatory markers on RAW 264.7 macrophages. Food Chem. 2018, 259, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparvoli, F.; Giofré, S.; Cominelli, E.; Avite, E.; Giuberti, G.; Luongo, D.; Gatti, E.; Cianciabella, M.; Daniele, G.M.; Rossi, M.; et al. Sensory Characteristics and Nutritional Quality of Food Products Made with a Biofortified and Lectin Free Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Flour. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosworthy, M.G.; Franczyk, A.; Zimoch-Korzycka, A.; Appah, P.; Utioh, A.; Neufeld, J.; House, J.D. Impact of Processing on the Protein Quality of Pinto Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) and Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) Flours and Blends, As Determined by in Vitro and in Vivo Methodologies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 3919–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Miranda, J.; Ramírez-Wong, B.; Vivar-Vera, M.A.; Solís-Soto, A.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Castro-Rosas, J.; Medrano-Roldan, H.; Delgado-Licon, E. Efecto de la concentración de harina de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), contenido de humedad y temperatura de extrusión sobre las propiedades funcionales de alimentos acuícolas. Rev. Mex. Ing. Química 2014, 13, 649–663. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Molina, I.; Mendoza-Avila, M.; Cornejo-Villegas, M.; Real-López, A.D.; Rivera-Muñoz, E.; Rodríguez-García, M.; Gutiérrez-Cortez, E. Physicochemical Properties and Resistant Starch Content of Corn Tortilla Flours Refrigerated at Different Storage Times. Foods 2020, 9, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neder-Suárez, D.; Amaya-Guerra, C.A.; Pérez-Carrillo, E.; Quintero-Ramos, A.; Mendez-Zamora, G.; Sánchez-Madrigal, M.Á.; Barba-Dávila, B.A.; Lardizábal-Gutiérrez, D. Optimization of an Extrusion Cooking Process to Increase Formation of Resistant Starch from Corn Starch with Addition of Citric Acid. Starch-Stärke 2020, 72, 1900150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroon, F.; Ghazanfar, M. Applications of Food Biotechnology. J. Ecosyst. Ecography 2016, 6, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendoza-Meneses, C.J.; Gaytán-Martínez, M.; Morales-Sánchez, E.; Contreras-Padilla, M. Physicochemical and thermal characteristics of microencapsulated Fe by electrostatic coacervation. Rev. Ciencias 2020, 7, e680. [Google Scholar]

- Aghbashlo, M.; Mobli, H.; Madadlou, A.; Rafiee, S. Influence of Wall Material and Inlet Drying Air Temperature on the Microencapsulation of Fish Oil by Spray Drying. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 6, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, G.A.; Arias Gorman, A.M.; Sgroppo, S.C. Nanotecnología y su aplicación en alimentos. Mundo Nano Rev. Interdiscip. Nanociencias Nanotecnología 2019, 12, 1e–14e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.V.; Kim, S.; Choi, Y.; Kwak, H.S.; Lee, S.J.; Wen, J.; Oey, I.; Ko, S. Antioxidant activity and bioaccessibility of size-different nanoemulsions for lycopene-enriched tomato extract. Food Chem. 2015, 178, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, R. Laying the foundations for a Bio-economy. Syst. Synth. Biol. 2007, 1, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adefegha, A. Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals as Dietary Intervention in Chronic Diseases; Novel Perspectives for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. J. Diet. Suppl. 2017, 15, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmiento-Rubiano, L. Alimentos funcionales, una nueva alternativa de alimentación. Orinoquia 2006, 10, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

| Prebiotic, Probiotic or Synbiotic | General Effect | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prebiotics | Arabinoxylans (AX) | Promote the growth of probiotic bacteria of the genus Bifidobacterium. | [31] |

| Xylooligosaccharides (XOS) | Promote the growth of L. plantarum S2, increasing short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) and the anti-microbial effect of L. plantarum against S. flexneri, E. coli, S. aureus, and S. typhimurium. | [32] | |

| High-amylose maize type 2 resistant starch (HAM-RS2) | Reduction in the concentrations of blood urea nitrogen, IL-6, TNFα, and malondialdehyde, and increase in the relative abundance of Faecalibacterium genus. | [33] | |

| Dietary fibers K1 and K2 | Increase in SCFA content and stimulate the growth of Bifidobacterium genus and Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria phyla. | [29] | |

| Feruloylated arabinoxylan mono- and oligosaccharides (F-AXOS) | Selectively stimulate Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. | [30,34] | |

| Probiotics | Streptococcus genera, Weissella paramesenteroides, Lactococcus lactis and L. paramesenteroides | Functional probiotic properties: resistance to low pH and bile salts conditions, ability to adhere to HEp2 cell line | [35] |

| Pediococcus pentosaceus, Weissella confusa, Weissella paramesenteroides, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Levilactobacillus brevis, Lactobacillus coryniformis, Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides and Lactococcus lactis | Antimicrobial properties against Enterobacteriaceae, and yeasts | [36,37] | |

| Weissella cibaria and Leuconostoc citreum | Antagonistic activity towards foodborne pathogens, short-chain fatty acids production and adhesion to HT-29 cell line | [38,39] | |

| Synbiotics | Hi-maize 958 or Hi-maize 260 resistant starch (RS), in combination with Bifidobacterium lactis | Modulation over the microbiota composition, re-inforced the innate immune system, and decreased blood lipids levels in hypercholesterolemic patients | [40] |

| XOS and Lacticaseibacillus paracasei HII01 | Reduction in gut inflammation and restoration of dybiosis in obese rats. | [41] | |

| Promitor™ Soluble Corn Fiber and L. rhamnosus LGG | Increase in NK cell activity and decreased serum total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol in patients with dyslipidemia, and also increases in Ruminococcaceae and Parabacteroides. | [42] |

| Probiotic, Prebiotic, or Synbiotic | General Effect | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prebiotics | Agavins | Reverse the metabolic disorders including microbiota changes | [46] |

| Powder of A. sisalana bole extract (rich in inulin) | Important source of substrate for the higher fermentation potential with LAB | [63] | |

| Agave fourcroydes | Phenolic compounds including quercetin, kaempferol, (+)-catechin, and (−)-epicatechin exhibit possible prebiotic potentional. | [64] | |

| Probiotics | L. mesenteroides P45 | Antibacterial activity against the pathogens Listeria monocytogenes, enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | [56] |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides | Survival on the in vitro GIT simulated conditions and exhibited antimicrobial activity against some pathogens | [65] | |

| Leuconostoc SD23 | Reduction in serum glucose, the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, and triglycerides in maternal obesity rats | [66] | |

| L. sanfrancensis LBH1068 | Anti-inflammatory properties on an HT-29 cells TNF-α model and improvement of symptoms in the DNBS-colitis model | [17] | |

| L. plantarum LM17 | Significant reduction in weight loss and improvement in the intestinal permeability using the DNBS-colitis model | [18] | |

| Synbiotics | Agave fructans (Agave salmiana) and probiotic bacteria, Lacticaseibacillus casei SACCO BGP93 and Bifidobacterium lactis SACCO BLC1 | Stimulation of the intestinal host defense. Antagonic activity to pathogens. | [67] |

| Agave inulin and L. reuteri DSM 17,938 | Improved stool characteristics in children with cerebral palsy and chronic constipation | [58] |

| Prebiotic, Probiotic, or Synbiotic | General Effect | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prebiotics | Opuntia pear peel | Specific bacterial growth and higher organic acid production than glucose in in vitro assays | [85,86] |

| Opuntia pear peel | Higher counts of lactic acid bacteria and Bifidobacteria species | [87] | |

| Opuntia ficus indica fruit juice | Specific bacterial growth (Limosilactobacillus fermentum ATCC 9338), decreased sugar components and decreased risky volatile components | [88] | |

| Opuntia ficus indica fruit juice | Changes in the growth speed and density of microorganisms of the intestinal microbiota | [89] | |

| Nopal | Modification on the gut microbiota profile, metabolic changes, and an important reduction in circulating lipopolysacharide levels | [90,91] | |

| Nopal fiber | Higher intestinal bacterial diversity in specific phyla and cecal fermentation. Modulation of inflammatory intestinal markers and oxidative stress | [92] | |

| Synbiotics | Cactus pear peel flour and LAB (Lactiplantibacillus plantarum UAM17, Enterococcus faecium UAM18, Aerococcus viridans UAM21b and Pediococcus pentosaceus UAM22a) (potential synbiotic) | Increased bacterial viability and resistance to acidic conditions by co-encapsulation with pear peel flour | [93] |

| Cactus pear peel flour with wheat flour and Pediococcus pentosaceus UAM22a (potential synbiotic) | More water retention, increased yield and reduction on the oxidative rancidity on a formulated sausage. | [94] | |

| Cactus pear peel flour as co-encapsulant of probiotic Enterococcus faecium UAM1 or Pediococcus pentosaceus UAM2 (potential synbiotic) | Prevention of food spoilage from coliforms and decreased oxidative rancidity | [95] | |

| Cactus fruit juice and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum S-811, L. plantarum S-TF2, Fructobacillus fructosus S-22, and F. fructosus S-TF7 | Organoleptic characteristics guaranteed, inocuity preservation, and protection from pathogens | [96] | |

| Cactus fruit juice and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum S-811 | Improvement of stress tolerance in Sacharomyces cerevisiae Decrease in adipose index, weight, and intestinal inflammatory parameters in C57-BL6 obese mice | [97] | |

| Cactus cladodes pulp and LAB (L. brevis POM2 and POM4) | Increased synthesis of GABA Preservative effects on vitamin C and carotenoids Increased radical scavenging activity | [98] | |

| Cactus fruit puree Leuconostoc mesenteroides | Anti-inflammatory effects and tight junctions integrity Decreased oxidative stress | [99] |

| Prebiotic | General Effect | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prebiotics | Bean flours containing of indigestible carbohydrates | Increase SCFA’s production in Wistar rats feeding with bean flours fractions | [113] |

| Non-digestible fraction from cooked bean (Negro and Bayo Madero beans varieties) | In vitro increase in SCFA’s production by fermentation with an inoculum of human gut microbiota | [114] | |

| Non-digestible fractions of Phaseolus vulgaris | SCFAs production on intestinal cell lines | [15,115] | |

| Crude water extractable polysaccharides from Phaseolus vulgaris | Increase in the growth of in vitro L. plantarum and L. fermentum | [116] | |

| Soluble extract of carioca beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) | Increase in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium and decrease in pathogenic bacteria. Increase zinc and iron bioavailability (in vivo model) | [117] | |

| Pinto bean variety | Changes in gut microbiota, increase in butyrate content, and improvement in anti-inflammatory and lipid profiles (C57BL/6J mice model and clinical trial) | [118] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres-Maravilla, E.; Méndez-Trujillo, V.; Hernández-Delgado, N.C.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Reyes-Pavón, D. Looking inside Mexican Traditional Food as Sources of Synbiotics for Developing Novel Functional Products. Fermentation 2022, 8, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8030123

Torres-Maravilla E, Méndez-Trujillo V, Hernández-Delgado NC, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Reyes-Pavón D. Looking inside Mexican Traditional Food as Sources of Synbiotics for Developing Novel Functional Products. Fermentation. 2022; 8(3):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8030123

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres-Maravilla, Edgar, Vianey Méndez-Trujillo, Natalia C. Hernández-Delgado, Luis G. Bermúdez-Humarán, and Diana Reyes-Pavón. 2022. "Looking inside Mexican Traditional Food as Sources of Synbiotics for Developing Novel Functional Products" Fermentation 8, no. 3: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8030123

APA StyleTorres-Maravilla, E., Méndez-Trujillo, V., Hernández-Delgado, N. C., Bermúdez-Humarán, L. G., & Reyes-Pavón, D. (2022). Looking inside Mexican Traditional Food as Sources of Synbiotics for Developing Novel Functional Products. Fermentation, 8(3), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8030123