Abstract

Food losses (FL) and waste (FW) occur throughout the food supply chain. These residues are disposed of on landfills producing environmental issues due to pollutants released into the air, water, and soil. Several research efforts have focused on upgrading FL and FW in a portfolio of added-value products and energy vectors. Among the most relevant research advances, biotechnological upgrading of these residues via fermentation has been demonstrated to be a potential valorization alternative. Despite the multiple investigations performed on the conversion of FL and FW, a lack of comprehensive and systematic literature reviews evaluating the potential of fermentative processes to upgrade different food residues has been identified. Therefore, this article reviews the use of FL and FW in fermentative processes considering the composition, operating conditions, platforms, fermentation product application, and restrictions. This review provides the framework of food residue fermentation based on reported applications, experimental, and theoretical data. Moreover, this review provides future research ideas based on the analyzed information. Thus, potential applications and restrictions of the FL and FW used for fermentative processes are highlighted. In the end, food residues fermentation must be considered a mandatory step toward waste minimization, a circular economy, and the development of more sustainable production and consumption patterns.

1. Introduction

Strategies and efforts for promoting sustainable development have been affected by emerging worldwide issues such as COVID-19 and the Russia and Ukraine war [1]. In addition, fuel price fluctuation, food price increases, and high unemployment rates have caused a great impact in different world regions [2]. On the other hand, social inequality and hunger have caused food insecurity and poverty in countries with low economic development (low and lower middle income) [3]. Consequently, the accomplishment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) proposed by the United Nations (UN) in 2015 has been delayed [4]. Likewise, unsustainable production and consumption patterns have contributed to climate change and biodiversity loss since the current linear economy model releases large amounts of pollutants (e.g., greenhouse gases and untreated industrial effluents) [5]. For this reason, worldwide efforts are guided to developing alternatives for promoting the efficient use of resources [6].

Worldwide estimations indicate that about 30% of food products are considered waste (food residues—FR). In the first links of the Food Value Chains (FVC), about 13.3% of the produced food is lost (i.e., harvest, slaughter, post-harvest, transformation, or manufacturing), and 17% is discarded at the consumer level [7]. FL are included the byproducts generated in food production with little or no added value (e.g., cheese whey, spent brewery yeast, expired juice) [8,9]. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), countries with low economic development generate more food losses [9]. The main contributing factors are poor logistics in FVC, and climate change that affects food production. These issues should be addressed to reduce food losses [10]. In addition, the agricultural and agro-industrial sectors are key for the development of countries with low economic growth. Countries with high economic development (upper middle and high income) generate more food waste [9]. The amount and type of food waste generated depends on socio-cultural practices and economic conditions [11]. The current disposal of FR in landfills or incinerators are generating emissions to water, land, and air [12]. Therefore, improving FR management would mitigate these effects and promote the efficient use of resources. However, FR characteristics cannot be generalized to evaluate alternative uses. Food losses (FL) generated in the stages before marketing and consumption present a homogeneous composition since these residues come from a specific value chain. On the other hand, food waste (FW) is a grouping of waste from different products generated in different value chains [13]. The composition of the FW depends on factors such as socio-economic and cultural conditions and the seasonality of food [14].

The FL and FW can be upgraded into added-value products promoting an efficient and sustainable use of resources, bio-economy development, and generating a circular economy within the FVC [15]. In fact, reducing FL and FW is a goal stipulated in the SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) that also allows linking other aspects such as food security, nutrition, and environmental sustainability “reduce per capita global FLW at the retail and consumer level by half and reduce the loss of food throughout production and the supply chain including post-harvest loss by 2030” [16]. The consequences of meeting this goal would allow the achievement of better food security, a nutrition improvement (SDG 2), and an environmental effects reduction (SDGs 11, 13, 14, and 15). However, the search for new alternatives for the disposal of FL and FW requires the development of other objectives such as the generation of clean and affordable energy (SDG 7), infrastructure, industry and innovation (SDG 9), economic growth and decent employment (SDG 8), reducing inequality (SDG 10) and ending poverty (SDG 1).

FL and FW valorization strategies have been addressed to produce energy vectors such as biomethane, biogas, ethanol, hydrogen, and butanol and products with high added value such as volatile fatty acids, biomaterials, biofertilizers, growth enhancers, organic acids, among others [17]. Other recently investigated FL and FW valorization routes with great potential have been aimed at the production of food grades such as omega-3 oil [18]. Furthermore, expired food has been researched for producing added-value products since the composition after a degradation procedure tends to be constant and high in valuable components [19]. FL and FW are globally and generally made up of carbohydrates (35.5–60%), protein (21.9–30%), oils, fats, and organic acids (3.9–65%) [18,20]. However, the composition of these residues is complex, and varies depending on factors such as the fruit degree maturity, productive process type among others [21]. The carbohydrate and protein fractions can be hydrolyzed to obtain fermentable sugars and oligomers [22]. Fermentable sugars are used in fermentative processes with yeasts, fungi, and bacteria [15]. On the other hand, lipids are a fraction of FL and FW with great potential to be used in fermentative processes using aquatic protists (i.e., single-celled eukaryotes that range from algae to heterotrophic flagellates) [23].

Despite the multiple investigations performed on the conversion of FL and FW, there is a lack of comprehensive and systematic reviews of the literature aimed at evaluating the fermentative processes to obtain different products. This article reviews the use of FL and FW in fermentative processes. The definition and classification of FL and FW based on the links of the FVC are presented. The variability of the chemical characterization of the FL and FW is analyzed from the point of view of chemical composition, and total and volatile solids content. Then, a review of the trends of fermentation products obtained from FL and FW and the main product platforms is presented. Finally, the observed potentials and restrictions, and future directions are elucidated.

2. Food Waste: Definition, Classification Based on Value Chain Link and Chemical Composition

2.1. Definition and Classification

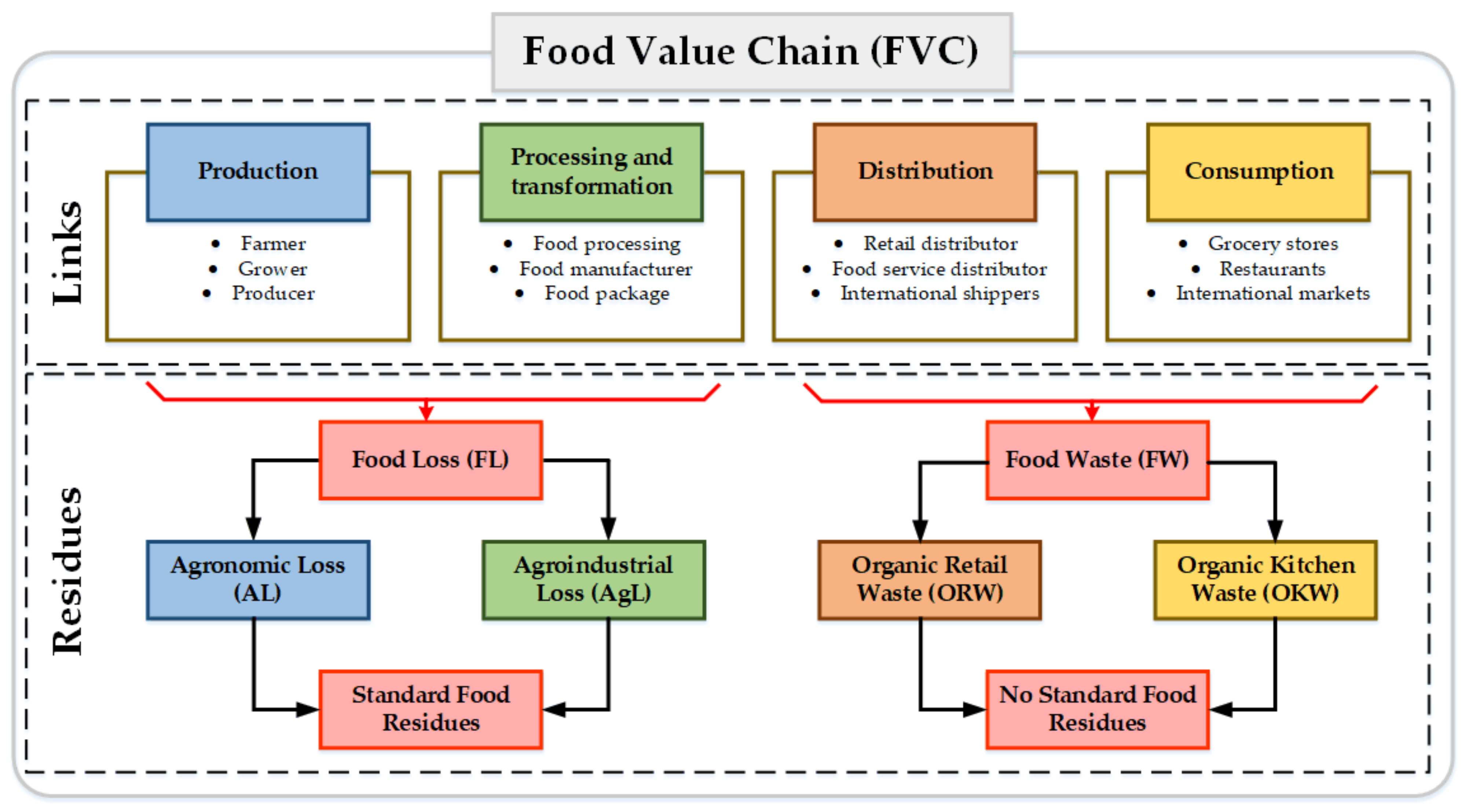

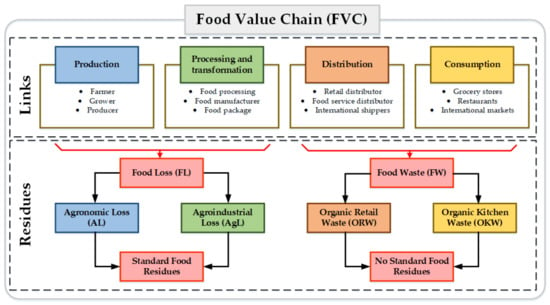

Several definitions and classifications for FW are found in the open literature. However, a clear difference between the residues produced in the agronomic, industrial processing, commercialization, and consumption stages has not been provided [24]. Therefore, an alternative for classifying FW is to consider the FVC links. In general terms, the FVC is composed of four global links: (i) production, (ii) manufacturing and processing, (iii) distribution, and (iv) consumption (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Classification of Food Loss and Waste based on the value chain.

According to the FAO, “Food Loss (FL) is the decrease in the quantity or quality of food resulting from decisions and actions of food suppliers in the supply chain, excluding retailers, food service providers, and consumers” [9]. All food discarded or incinerated from harvest (slaughter, recovery) to transformation or marketing is considered to be FL. The FL obtained in agricultural and farming production, post-harvest, handling, slaughter, storage, and process distribution and transformation can be grouped as Agronomic Loss (AL). These FLs correspond to the waste generated in a single FVC location. For example, the first three stages of the fruit FVC occur in the same crop location or neighboring areas. In the fruit agricultural production stage, stems, leaves, roots, and fruit are generated with low-quality standards (overripe), flowers, and dung. The FL generated in the processing, packaging, and distribution stages can be grouped as Agro-industrial Loss (AgL). In the case of fruit FVC, these stages generate residues such as peel, seeds and liquid, and solid residues.

On the other hand, “FW is the decrease in the quantity or quality of food resulting from decisions and actions of retailers, food services and consumer” [9]. FW is the food mass decrease within the distribution and consumption links. FW can be classified as organic retail waste (ORW) and organic kitchen food waste (OKFW). This type of waste contains agronomic and agro-industrial products such as vegetables, fruit, farming products, or processed products. The main characteristic of this waste is non-standardized composition. FW includes the following items [7]:

- Food or products that deviate from the end goal: Products with physical and organoleptic properties that do not meet the standard.

- Food or products discarded by retailers or consumers: Expired expiration date.

- Food or food fragments, and edible and inedible products that are discarded in domestic kitchens, food establishments, or markets.

FL and FW can be grouped as food residues (FR). Different authors have supported this classification. For instance, Oliveira et al. [25] reported a systematic review aimed at finding potential alternatives to FL and FW upgrading in the circular bio-economy framework. Moreover, Lucifero [26] analyzed the FL and FW generation issue based on European Union legislation, since European countries have been looking for more environmentally friendly disposal alternatives. Finally, Aschemann-Witzel et al. [27] defined upcycled food based on the FL and FW concepts. Then, the above-mentioned classification has been used in the open literature to refer to the same issues related to FR generation.

An alternative way to classify FR depends on composition variability. Then, standard food residues and non-standard food residues can be identified. Standard food residues do not present changes in composition over time and are generated only in FVC. Agronomic and agro-industrial residues are classified as standard food waste. Non-standard food residues present changes in composition based on the socio-economic and cultural context. Non-standard food residues composition groups the residues generated within the distribution and consumption links. Several reports have supported this classification since a similar classification based on homogeneous and heterogeneous FR has been reported [28].

2.2. Chemical Characterization of Food Waste

FL and FW have a diverse composition, but carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids have been considered to be the most important and representative fractions of these raw materials. Carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids are the source of primary platforms such as sugars, amino acids, fatty acids, and glycerol after hydrolysis. Table 1 and Table 2 present FL and FW chemical characterization.

The composition of both FL and FW depends on the origin source. Table 1 and Table 2 show the composition of different FL and FW. In comparison to the FW, the FL (agronomic and agro-industrial residues) are characterized more completely mainly in terms of fibers, extractives, and ash. Fractions such as fats, pectin and starch are randomly characterized depending on the raw material. However, this leads to incomplete compositions and wrong composition normalizations (wrong fraction concentration calculation). On the other hand, FWs are characterized and studied considering a specific waste generated in a specific sector (e.g., kitchen, dinner shop, or canteen) and in specific locations (e.g., university restaurants, cafeterias in a specific shopping center). representing a limitation for a global valuation of FW. The main reason for this is that composition variability is not considered to propose harvesting routes. The composition of the FL generated in a production chain presents less variability compared to the FW.

Biotechnology conversions include all enzymatic fermentation and saccharification routes [29]. Cellulose, hemicellulose, starch, and pectin fractions are used in FL and FW transformation processes [30]. Thus, the type of products to be obtained considers food, organic molecules, biofuels, and biomaterials [31]. Probiotics and single-cell protein from FL have been extensively studied [32]. Organic molecules such as citric acid, lactic acid, succinic acid, and ascorbic acid have been obtained from FL and FW using cellulose and hemicellulose fractions (fermentable sugars) [29].

Table 1.

Chemical composition of some FW.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of some FW.

| Chemical Composition * | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction | Precooked Food Waste [33] | Fruit Peel Waste [34] | Fresh Vegetable Waste [35] | Rice, Vegetables and Meats [36] | Household Food Waste [37] | Restaurant Food Waste [37] | Kitchen Waste [38] | Kitchen Waste [38] | Organic Municipal Solid Waste [39] | Kitchen Garbage [33] | Municipal Solid Waste [40] |

| Moisture ** | 82.8% | N.R. | 89.81% | 81.9% | N.R. | 71.6% | 80.3% | 61.3% | N.R. | 75.2% | 85.7% |

| Total sugar *** | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 44.6% | N.R. | N.R. | 59.8% | 85.2% | 35.0% | 37.9% | 46.6% |

| Starch | 41.5% | N.R. | N.R. | 39.0% | 33.1% | 30.7% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 34.8% | 31.2% |

| Cellulose | 2.1% | 21.5% | 26.9% | N.R. | 31.9% | 16.1% | N.R. | N.R. | 28.8% | N.R. | 2.6% |

| Hemicellulose | N.R. | 11.8% | 51.4% | N.R. | 35.0% | 3.1% | N.R. | N.R. | 22.7% | N.R. | N.R. |

| Lignin | N.R. | 8.0% | 21.7% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 0.8% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| Carbohydrates | 56.4% | 58.7% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 50.0% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| Fats | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 15.7% | 7.9% | 9.7% | 13.7% | N.R. |

| Protein | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 16.4% | N.R. | N.R. | 21.8% | 5.4% | N.R. | 11.9% | 19.6% |

| Pectin | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 2.7% | N.R. | N.R. |

| Ash | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 1.9% | 1.5% | 1.1% | 1.7% | N.R. |

| Total and volatile solids | |||||||||||

| Fraction | Precooked food waste [41] | Fruit peel waste [42] | Fresh vegetable waste [41] | Rice, Vegetables, and meats [43] | Organic fraction of municipal solid waste [44] | Household food waste [45] | Cafeteria food waste [45] | Kitchen waste [45] | Organic municipal solid waste [46] | Kitchen garbage [47] | Municipal solid waste [48] |

| Moisture | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 76.6% | 90.3% | 81.0% | N.R. | 74.0% |

| Total solid | 30.4% | 9.7% | 12.2% | 53.6% | 24.8% | 50.6% | 51.8% | 52.2% | 51.4% | 52.4% | 54.0% |

| Volatile solid | 69.6% | 90.3% | 87.8% | 46.4% | 75.2% | 49.4% | 48.2% | 47.8% | 48.6% | 47.6% | 46.0% |

| Ratio carbon to nitrogen | |||||||||||

| Fraction | Precooked food waste [41] | Fruit peel waste [49] | Fresh vegetable waste [41] | Rice, Vegetables, and meats [43] | Organic fraction of municipal solid waste [44] | Household food waste [45] | Cafeteria food waste [45] | Kitchen waste [45] | Organic municipal solid waste [46] | Kitchen garbage [47] | Municipal solid waste [48] |

| C/N | 21.69 | 21.10 | 5.65 | 21.7 | 12.6 | 18.00 | 23.00 | 11.00 | 13.20 | 24.50 | 14.80 |

* Chemical composition is reported in dry base; ** Initial moisture of raw material; *** Extractives content in raw material; N.R.: Not reported.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of some FL.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of some FL.

| Chemical Composition (%) * | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction | Fermented Cheese Whey [50] | Apple Pomace [51] | Watermelon Rinds [52] | Potato Peels [53] | Coffee Cut-Stem [54] | Oil Palm Rachis [55] | Plantain Peel [56] | Avocado Seed [57] | Tomato Pomace [58] | Carrot Waste [51] | Sugarcane Bagasse [29] | Orange Peel [31] | Wastewater from Cheese Whey [59] | Rice Husk [60] |

| Moisture ** | 6.9% | 4.7% | 10.6% | 65.0% | 4.00% | N.R. | N.R. | 46.10% | 84.7% | 5.5% | N.R. | 77.38% | N.R. | N.R. |

| Total Sugar *** | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 1.7% | 15.6% | 10.4% | 38.9% | N.R. | N.R. | 8.6% | 21.4% | 25.3% | 8.1% |

| Cellulose | N.R. | 7.3% | 15.5% | 25.8% | 32.4% | 42.0% | 10.5% | N.R. | 27.8% | 27.2% | 31.5% | 19.3% | N.R. | 28.8% |

| Hemicellulose | N.R. | 20.8% | 17.8% | 5.5% | 13.8% | 23.1% | 12.8% | 34.8% | 33.6% | 11.2% | 21.5% | 11.4% | N.R. | 12.3% |

| Lignin | N.R. | 17.4% | 7.8% | 6.6% | 46.6% | 17.3% | 2.6% | 12.0% | 16.2% | 29.2% | 27.2% | 2.0% | N.R. | 24.3% |

| Carbohydrates | 86.2% | 46.9% | 43.4% | 28.8% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 13.8% | 29.0% | 8.6% | 21.4% | N.R. | 8.1% |

| Starch | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 31.7% | N.R. | N.R. | 45.6% | N.R. | 2.4% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| Pectin | N.R. | 7.6% | 15.5% | 1.6% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 6.1% | 3.4% | N.R. | 15.0% | N.R. | N.R. |

| Fats | 0.9% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 5.7% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 3.7% | 43.4% | N.R. |

| Protein | 12.9% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 4.6% | N.R. | 7.7% | 6.2% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 4.0% | 3.8% | 2.9% |

| Ash | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 0.9% | 2.0% | 10.4% | 2.5% | N.R. | N.R. | 2.5% | 1.7% | 27.5% | 15.5% |

| Total and volatile solids | ||||||||||||||

| Fraction | Fermented cheese whey [61] | Apple pomace [62] | Watermelon rinds [63] | Potato peels [64] | Coffee cut-stem [65] | Oil palm rachis [66] | Plantain peel [67] | Avocado seed [68] | Tomato pomace [69] | Carrot waste [70] | Sugarcane bagasse [30] | Orange peel [32] | Wastewater from cheese whey [71] | Rice husk [72] |

| Moisture | N.R. | N.R. | 26.9% | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 13.2% | 83.14% | N.R. | N.R. | 79.8% | N.R. | N.R. |

| Total solid | 67.3% | 17.3% | 55.3% | 9.1% | 50.2% | 45.1% | 11.0 | 50.3% | 15.4% | 9.8% | 56.0% | 51.1% | 50.4% | 52.6% |

| Volatile solid | 32.7% | 82.7% | 44.7% | 90.9% | 49.8% | 54.9% | 89.0 | 49.7% | 84.6% | 90.2% | 44.0% | 48.9% | 49.6% | 47.4% |

| Ratio of carbon and nitrogen | ||||||||||||||

| Fraction | Fermented cheese whey [61] | Apple pomace [73] | Watermelon rinds [74] | Potato peels [75] | Coffee cut-stem [76] | Oil palm rachis [55] | Plantain peel [67] | Avocado seed [77] | Tomato pomace [78] | Carrot waste [79] | Sugarcane bagasse [30] | Orange peel [80] | Wastewater from cheese whey [71] | Rice husk [72] |

| C/N | 8.13 | 61.89 | 42.76 | 10.7 | 48.9 | 62.8 | 39.0 | 57.5 | 11.00 | 27.00 | 33.69 | 33.83 | 5.8 | 38.48 |

* Chemical composition is reported in dry base; ** Initial moisture of raw material; *** Extractives content in raw material; N.R.: No Reported.

In recent years, pectin has emerged as a platform product for the synthesis of mucic acid, l-galactonic acid, l-ascorbic acid, 1-4 biotanedium, and ethanol [80]. This product synthesis is carried out from galacturonic acid, the main compound of pectin. Genetically modified micro-organisms have been used to synthesize galacturonic acid and to produce the above-mentioned products. Fibrous and pectic fractions of FL and FW have also been used to synthesize biofuels such as ethanol, butanol, and biogas [57]. Different types of processes, such as saccharification and simultaneous fermentation, have been implemented [81]. Different enzyme concentrations, types of micro-organism, and pretreatment stages (chemical and physical conversions such as steam exploitation, acid hydrolysis, steam distillation) have been applied to produce organic molecules and biofuels [60].

Fermentative processes upgrade hydrolysis products to other added-value platforms using micro-organisms and mild operating conditions (i.e., temperature: 30–50 °C and pressure: atmospheric) [82]. Then, the process energy intensity is low compared to thermochemical and catalytic pathways. Nevertheless, maximum titers and downstream processing (i.e., platform chemical separation from fermentation broth) must be considered before proposing a complete valorization of FL and FW.

3. Trends of Fermentation Products Obtained from Food-Waste Valorization

3.1. Classification Based on Micro-Organism, Mode of Cultivation, Water Activity, Oxygen Requirement, Nutrient Metabolism and Number of Inoculums

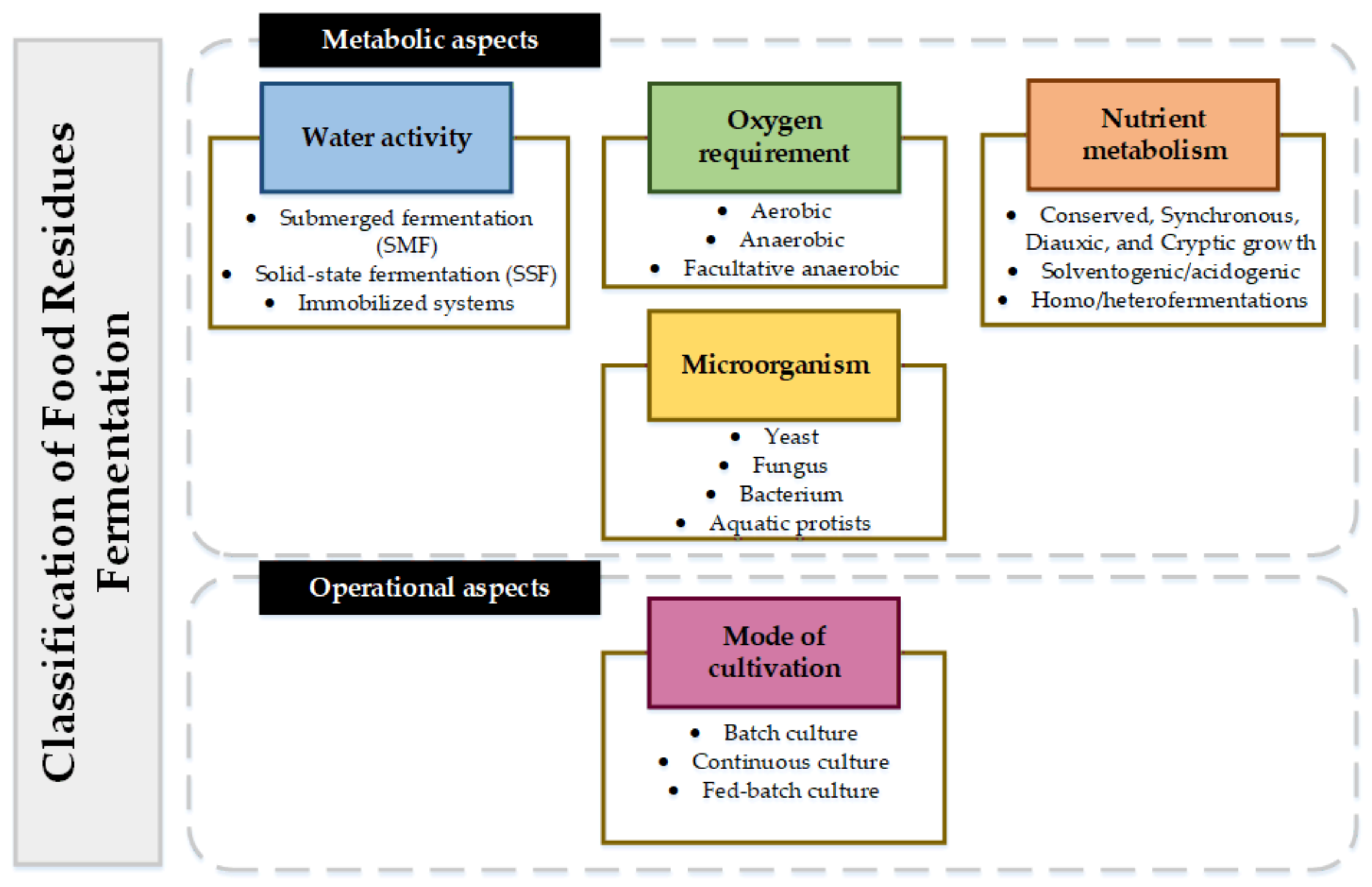

Fermentation is a valorization route with high application, high efficiency, and strong robustness (technological readiness level), and presents a wide range of possible value-added products. Fermentation can be classified considering different metabolic aspects such as water activity, oxygen requirements, and nutrient metabolism. According to technical aspects, fermentations can also be classified considering the reactor type or cultivation mode (i.e., continuously stirred tank reactors, single-stage or batch reactors, electro reactors, among others). Figure 2 presents the classification of fermentative processes:

Figure 2.

Classification of FR fermentation.

Micro-organisms are classified as yeasts, fungi, bacteria, and aquatics protists. Aquatics protists are unicellular eukaryotic micro-organisms that can range from algae to heterotrophic flagellates [83]. One of the main characteristics of aquatics protists is the ability to synthesize between 20% w/w and 70% w/w lipids based on [84] cell weight. Depending on culture conditions, some aquatics protists can increase lipid production with high C/N [85] ratios. Among the lipids that protists aquatics can synthesize are saturated and unsaturated fatty acids with chain lengths between 4 and 28 such as omega-3, α-linolenic acid, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), among others [18].

In terms of oxygen requirement, micro-organisms can be classified into aerobic, anaerobic, and facultative anaerobes [86]. Micro-organisms demanding oxygen are aerobic. Anaerobic micro-organisms carry out fermentations without oxygen. Finally, facultative micro-organisms are anaerobic in the cell-growth phase and aerobic in the production phase.

The water activity of fermentation is classified into submerged fermentation (SMF) and solid-state fermentation (SSF). The difference between SMF and SSF is the type of substrate solution used (i.e., solid in SMF, liquid in SSF) [87]. In SSF, the micro-organism growth and the obtained product are carried out in solid particles with little moisture [88]. Some advantages of SSF over SMF are the low operating costs due to less use of water and reagents, fewer separation and purification steps, low energy consumption, and use of non-sterile substrates (non-sterile conditions for the process) [89]. In addition, SSF is carried out with simple technologies [90]. However, SSF has several challenges, such as mass and heat transfer on large scales, poor reproducibility, aeration of the substrate, and poor operational control due to the lack of reaction kinetics [87]. Another disadvantage of SSF is the number of micro-organisms and substrates that can be used in this type of fermentation [91]. The most studied micro-organisms to be used in SSF are fungi and yeasts [91]. This is why SMF is the most sought-after for obtaining commercial products.

Nutrient metabolism (physiological status) of micro-organisms in fermentations has different types of growth: conserved, synchronous, diauxic, or cryptic [92]. On the other hand, fermentations can be classified as solventogenic (i.e., production of solvents) or acidogenic (i.e., production of acids) [93] depending on the product type. When considering the metabolic pathways, homofermentative and heterofermentative processes can be identified. Homofermentative processes make use of metabolism under a substrate to obtain the product. Heterofermentative processes use several metabolic pathways for the synthesis of different substrates or nutrients [94].

Finally, fermentation can be carried out in batch, continuous, or fed-batch mode, depending on the operational aspects [95]. Selecting the type of fermentation and the type of micro-organism is a crucial step for FL and FW valorizing. The type of inoculum (micro-organism), pH, oxidation potential, organic loading rate, nutrients, and substrate type defines process productivity and yield. This section presents a systematic review of the fermentation of different types of FL and FW, considering micro-organisms, operating conditions, water activity, oxygen requirements, and yields to obtain different types of products.

3.2. Pretreatment and Sacarification Stage (Upstream)

Upstream from FL and FW fermentation are the pretreatment and saccharification processes to obtain fermentable sugars. The main objectives of FL and FW pretreatments are (i) to improve mass transfer, (ii) to reduce or to eliminate toxic compounds, (iii) to increase accessibility, and (iv) to increase digestibility [96,97]. The pretreatment selection is based on the FL and FW characteristics and the subsequent processing routes [98]. FL and FW are pretreated with combined physical, thermal and chemical processes [99].

The physical and mechanical pretreatments are grinding, cutting, and blending to increase the surface area [100]. The objective of the thermal pretreatments is to reduce the moisture, help to solubilize sugars, dilate the cell membrane and/or sterilize the biomass [101]. In this pretreatment type, the recalcitrance and chemical composition of biomass are affected. Chemical pretreatments are methods such as hydrolysis with acids (e.g., sulfuric acid, phosphoric acid, hydrochloric acid) or bases (e.g., NaOH, sodium sulfite, hydrogen peroxide). The chemical pretreatment objective is to solubilize the hemicellulose (acid hydrolysis) and the lignin (alkaline pretreatment), protein, and lipids [102]. The operating conditions of the chemical pretreatments of FL and FW must be studied to avoid the formation of inhibitory compounds (i.e., furanic and/or phenolic compounds) [103].

The type of pretreatment that is carried out for FL and FW differs from the fermentation and the chemical composition. Chemical pretreatments are used more in FL than in FW due to the differences in the amount of lignin (see Table 1). Another type of FL pretreatment considers the extraction of bioactive compounds or essential oil from fractions such as lipids, fats, volatile and extractive compounds (see Table 2). The extraction of these compounds for FW has not been widely analyzed. The main reason for this is the limitations of applications for the acquisition of bioactive compounds from FW. The pretreatments for FW are mainly physical and thermal.

Saccharification or enzymatic hydrolysis in FL and FW has been studied using a wide range of enzymes such as α-amylase, cellulases, xylanases, pectinases, proteases, chitinase, lactases, among others [104]. Research on the use of enzyme cocktails in FL and FW focuses on the evaluation of operating conditions (i.e., temperature, pH, agitation, incubation time, enzyme concentration, substrate concentration, among others) to obtain mainly sugars [105]. The enzyme cocktail selection for FL and FW depends on the nature and composition of the residue [106]. For FL, the production of fermentable sugars has been investigated from the most relevant raw material fractions (i.e., cellulose, pectin, and starch) [107]. For example, for agro-industrial residues such as sugarcane bagasse, the enzymatic hydrolysis step is aimed at breaking down the cellulose [108]. For orange peel waste, enzymatic hydrolysis aims to degrade the cellulose and pectin fraction [109]. For residues of amylase origin, the cellulose and starch fractions constitute fermentable sugars sources [110]. On the other hand, the production of fermentable sugars from FW presents a more complex challenge due to its versatility in its chemical composition (see Table 1) [111]. It is necessary to consider different types of enzymes (or enzyme cocktails) to hydrolyze the FW.

The obtained products from FL and FW fermentation can be grouped into energy vectors, biomaterials, organic acids, aromatic compounds, food and feeds, enzymes, and other compounds.

3.3. Products Obtained from Food-Waste Fermentation

3.3.1. Energy Production

The anaerobic digestion of FL and FW is a complex process that encompasses four phases carried out by a bacteria consortium (i.e., hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis) for biogas production. Biogas is a mixture of methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2) and other gases traces such as nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) [112]. The hydrolysis phase is the conversion of complex organic molecules into simple chains (e.g., fatty acids to glycerol and short chains fatty acids, cellulose to cellobiose and glucose). Acidogenesis converts organic molecules into volatile fatty acids (VFA). In the acetogenesis phase, VFAs are converted to acetic acid, H2, and CO2. Finally, in methanogenesis, the generated products in acetogenesis are converted into CH4 and CO2. The variability of the CH4 yields is related to the composition of the FL and FW (i.e., content of carbohydrates, proteins, lipids) and to previous pretreatments stages [113]. In addition, the bacteria consortium in anaerobic digestion requires essential nutrients (i.e., nitrogen, phosphorous, magnesium, sodium, calcium, manganese, and cobalt) that directly affect methane production yields [114]. The yield of methane production by FW digestion is between 0.14 and 0.47 m3 CH4/kg-VS of raw material [114]. Chew et al. [112] analyzed the most influential factors for biogas production considering the characteristics of the substrate and the operating conditions. The challenges presented by anaerobic digestion depending on the substrate (i.e., FL and FW) is the optimal carbon and nitrogen (C/N) ratio to maximize CH4 production [115]. In general, the optimal C/N ratio is between 20 and 30. Lower C/N ratios lead to a higher nitrogen content substrate, which promotes VFA production. However, FW can have a complex C/N ratio from 3 to 55 [116]. Several studies have shown that codigestion of FL and FW improves biogas production by 40–50% [113]. Boua-llagui et al. [117] evaluated the biogas production from FW (fruit and vegetables) and slaughterhouse residues, eliminating between 73 and 89% of the total VS with a biogas yield of 0.3–0.73 m3/kg-VS. Parawira et al. [118] analyzed the production of biogas from potato residues and sugar beet leaves, obtaining a yield of 0.68 m3 CH4/kg-VS. Another limitation and challenge that anaerobic digestion presents is the operating conditions, such as the organic load rate, pH, temperature, moisture content, quality and quantity of the inoculum, agitation, and retention time. All the above influence biogas production [114]. These conditions limit the biodegradability of FL and FW, limiting the accessibility and nutritional balance of anaerobic digestion. Other authors such as Srisowmeya et al. [119], Lytras et al. [120] and Dalke et al. [121] evaluated the main opportunities and limitations of the anaerobic digestion of FL and FW considering aspects of the raw material and operating conditions.

Hydrogen (H2) is a sustainable and renewable fuel from biological, thermochemical, and chemical routes [122]. The biological route is carried out by bacteria-synthesizing enzymes of the hydrogenase and nitrogenase type by photo-fermentation and dark fermentation [123]. H2 production results from the breakdown of carbohydrates by acidogenic and acetogenic metabolic pathways [124]. Photo-fermentation and dark H2 fermentation are sensitive to operating conditions such as pH, temperature, partial product pressure, substrate concentration, and VFA content [125]. Some authors specify that the protein content of the substrate should be increased to improve the production of hydrogen by micro-organisms [126]. In this sense, greater C/N ratio values than 20 present lower H2 production yields [127]. Mohd et al. [128] defined an optimal C/N ratio to be between 20 and 21 according to the systematic review for assessing FL and FW. Some of the limiting factors in FL and FW photo-fermentations and dark fermentations are the pretreatment stages of the substrate and inoculum (i.e., heating between 80 and 140 °C), pH (between 5 and 6 in continuous fermentations and 7 in batch fermentations), and temperature (i.e., thermophilic conditions between 50 and 60 °C) [123]. The inoculum for the production of H2 needs thermal shocks and chemicals [129]. Table 3 shows some yields obtained from the processing of FL and FW to obtain H2.

Biohythane is a mixture of CH4 and H2 in a 1:4 ratio, considered to be a fuel with good caloric efficiency [130]. Biohythane arises as a solution for pure H2 due to storage problems [131]. CH4 makes it possible to reduce the flammability of H2, improving the storage problem. Biohythane production has been studied at laboratory and semi-pilot scale with an anaerobic bacteria consortium [132]. Table 3 presents some biohytane production yields from FL. In the case of FW, biohythane production has not been analyzed.

Ethanol is one of the most researched energy vectors for the use of FL and FW [133,134]. On the other hand, butanol has emerged as a possible substitute for ethanol [135]. Unlike the production of biogas, H2, and biohytane, the production of ethanol and butanol is carried out using fermentable sugars as a substrate. For this reason, the pretreatment and saccharification stage is essential for ethanol and butanol production yields.

Table 3.

Bioenergy products obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

Table 3.

Bioenergy products obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

| Micro-Organism | Water Activity | Oxygen Requirement | Product | Substrate | Operational Conditions | Yields and Productivity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida rugosa | SMF | Anaerobic | Biogas | Food loss: Meat industry waste (pig meat) | Batch reactor volume: 80 mL; Inoculum concentration: 8 gVS/L; Temperature: 37 °C; Stirring rate: 150 rpm; pH: 7.0 | Biogas: 50.60%wt (Biomethane: 707 L/kg-VS) | [136] |

| Pig slurry (Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes) | SMF | Anaerobic | Biogas | Food loss: Tomato pomace (TP) and vegetable sludge (VS) | Anaerobic digester volume: 300 L; Semicontinuous mode; pH: 6.3–7.8; Temperature: 35 °C; Substrate load ratio: 70%:30% (TP and VS: Pig slurry); Stirring rate: 8–10 rpm; Total solids concentration: 6%; Total operating time: 110 days | Biogas: 60%wt | [137] |

| Agro-industrial wastewater treatment sludge | SMF | Anaerobic | Biogas | Food waste: Frozen food factory including fresh vegetable waste (VW) and precooked food waste (FW) | Batch reactor volume: 200 mL; pH: 7.0–8.0 Temperature: 35 °C; HRT: 31 days OLR: 3.5 gCOD/L-d; Sludge concentration: 22.2% wet basis; VW concentration: 32.3% wet basis; FW concentration: 45.5% wet basis | Biogas: 57%wt | [41] |

| Clostridium acetobutylicum | SSF | Anaerobic | Biohydrogen | Food loss: Defatted rice bran | Batch fermentation; Fermentation volume: 200 mL; Temperature: 34 °C pH: 5.5; Inoculum amount: 12.5%(v/v) | Biohydrogen: 10.55%wt (Biohydrogen: 117.24 mL/g sugar consumed) | [138] |

| Wastewater from chemical treatment | SSF | Anaerobic | Hydrogen | Food waste: Canteen-based composite food waste | Acidophilic microenvironment was used; Batch reactor was used; Fermentation volume: 180 mL; Temperature: 29 °C; pH: 6.0; Time: 71 h | Hydrogen: 14.06%wt (Hydrogen: 69.95 mmol) | [122] |

| Buttiauxella sp. 4, Rahnella sp. 10, and Raoultella sp. 47 | SSF | Anaerobic | Hydrogen | Food waste: Vegetable waste | Substrate particle size: 5 mm; Fermentation volume: 50 mL; Inoculum concentration: 10%v/v; Temperature: 28 °C; pH: 6.70; Stirring rate: 120 rpm | Hydrogen: 0.771%wt (Hydrogen: 85.65 mlH2/gVS) | [139] |

| Micro-organisms from wastewater of sweet potato processing factory | SSF | Aerobic | Hydrogen | Food waste: Kitchen waste and white rice | CSTR fermentation; Fermentation volume: 3 L; Temperature: 55 °C; pH: 5.4; Stirring rate: 160 rpm; Fermentation time: 20 days | Hydrogen: 0.255%wt (Hydrogen: 1.27 mmol/gCOD) | [140] |

| Anaerobic digester sludge | SSF | Anaerobic | Hydrogen and methane | Food waste: Potato waste, kitchen garbage, and soybean pulp | CSTR fermentation; Volume for hydrogenesis: 1 L; Volume for methanogenesis: 5 L; Time for hydrogenesis: 2 days; Time for methanogenesis: 10 days; Temperature: 55 °C; pH:5.5; Inoculum load: Added to fill ¼ volume of reactor | VS of Potato waste Hydrogen: 0.765%wt (Hydrogen: 85 mL/gVS) Methane: 22.206%wt (Methane: 338 mL/gVS) VS of Kitchen garbage Hydrogen: 0.594%wt (Hydrogen: 66 mL/gVS) Methane: 23.91%wt (Methane: 364 mL/gVS) VS of Soybean pulp Hydrogen: 0.18%wt (Hydrogen: 20 mL/gVS) Methane: 21.61%wt (Methane: 329 mL/gVS) | [125] |

| Sludge from anaerobic treatment of vinasse | SMF | Anaerobic | Biohythane (hydrogen and methane) | Food loss: Coffee residues | CSTR reactor; Fermentation volume: 4.3 L HRT: 55 days; OLR: 0.19 kg-VS-m3/d Temperature: 55 °C; pH: 5.5–6.0; Stirring rate: 2000 rpm | H2: 34.45%wt (H2: 30–40% in volume) CH4: 44.01%wt (CH4: 70% in volume) | [141] |

| Thermoanaerobacterium for hydrogen stage and Methanosarcina sp. for methane stage | SSF | Anaerobic | Biohythane (hydrogen and methane) | Food loss: Palm oil mill effluent (POME) | Temperature: 55 °C; Hydraulic retention time for hydrogen (HRT): 2 days; Organic loading rate for hydrogen (OLR): 27.5 gCOD/L-d; HRT for methane: 10 days OLR: 5.5 gCOD/L-d; pH: 5.0–6.5; POME is mixed with CH4 at a ratio of 1:1 before feeding the reactor tank | Biohythane: 38.60%wt (Biohythane: 1.93 L/L-d) Composition H2: 11%wt CO2: 37%wt CH4: 52%wt | [142] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | SSF | Anaerobic | Ethanol | Food loss: Pineapple waste | Fermentation volume: 1 L; Substrate concentration: 3 g/L; Glucose content: 4.43%wt; Inoculum concentration: 3 g/L Temperature: 30 °C; pH: 4.0; Incubation period: 3 days | Ethanol: 8.7%wt | [143] |

| Pichia stipitis | SMF | Aerobic | Ethanol | Food loss: Defatted rice bran | Batch fermentation; Fermentation media: 300 mL in 500 mL flask; Stirring rate: 200 rpm; pH: 5.5; Temperature: 30 °C; Culture medium: 5.0 g/L xylose and glucose; Inoculum volume: 8.5 mL; Initial sugars: 33.55 g/L | Ethanol: 42%wt (Ethanol: 0.42 g/g sugar used) | [144] |

| Zymomonas mobilis—ZM4 | SMF | Anaerobic | Ethanol | Food waste from a local supermarket | Fermentation volume: 3 L; Glucose concentration in medium: 200 g/L; Substrate load: 50 kg; Water load: 25 kg Glucoamylase: 20,000 U/g; Temperature: 50 °C; pH: 4.0; Stirring rate: 100 rpm; Time: 6 h | Ethanol: 50%wt (Ethanol: 50 g/g glucose) | [145] |

| Clostridium saccharoperbutylacetonicum | SMF | Anaerobic | Acetone, butanol, ethanol, acetic acid, and butyric acid | Food loss: Rice bran | Batch fermentation; Fermentation volume: 150 mL; Substrate concentration: 10%(w/v); Initial pH: 6.5; Initial temperature: 30 °C; Fermentation time: 120 h; Inoculum concentration: 10%(w/v) | Acetone: 0.23%wt; Butanol: 2.31%wt; Ethanol: 0.21%wt; Acetic acid: 1.24%wt; Butyric acid: 1.90%wt Acetone: 0.23; Butanol: 2.31; Ethanol: 0.21; Acetic acid: 1.24; Butyric acid: 1.90(g/L) | [146] |

| Clostridium kluyver | SMF | Anaerobic | Ethanol, acetate, and butyrate | Food waste: Fruit vegetable waste (FVW) | FVW was smashed and homogenized. Batch fermentation; Fermentation volume: 1 L; Volatile solids concentration: 50 g/L; Inoculum to substrate ratio; Temperature: 35 °C; pH: 6.3 | Ethanol: 1.6%wt Acetate: 10.8%wt Butyrate: 6.6%wt (g/L) Ethanol: 0.8 Acetate: 5.4 Butyrate: 3.3 | [147] |

| Clostridium beijerinckii | SMF | Anaerobic | Acetone, butanol, and ethanol | Food waste: | Fermentation volume: 150 mL; Food-waste medium load: 50 mL; Stock buffer solution: KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L; K2HPO4, 0.5 g/L; and NH4CH3CO2, 2.2 g/L; Temperature: 35 °C pH: 6.0; Incubation period: 72 h | Acetone: 4.0%wt Butanol: 7.7%wt Ethanol: 0.7%wt Acetone: 4.0 g/100 g Butanol: 7.7 g/100 g Ethanol: 0.7 g/100 g | [148] |

| Clostridium sp. strain—BOH3 | SMF | Anaerobic | Acetone, butanol, and hydrogen | Food waste from local food courts in Singapore | Fermentation volume: 160 mL; Substrate concentration: 60 g/L; Temperature: 35 °C pH: 5.0–5.2; Incubation time: 20 h; Stirring rate: 130 rpm | Butanol: 8.00%wt Acetone: 3.00%wt Hydrogen: 0.016%wt (Hydrogen: 0.08 mmol/g) | [149] |

| Clostridium saccharoperbutylacetonicum | IS | Anaerobic | Acetone, butanol, and ethanol | Food waste: Bakery wastes, fruit wastes, and vegetables wastes | Food wastes were homogenized in a blender; Fermentation volume: 245 mL. Immobilized-cell system: Activated carbon; Activated carbon particle size: 3–6 mm; Dilution rate: 0.10 h−1; Temperature: 30 °C; Time: 12 h | Butanol: 10.47%wt (Butanol: 10.47 g/L) ABE: 43%wt | [150] |

SSF: Solid-state fermentation, SMF: Submerged fermentation, IS: Immobilized systems.

The production of ethanol and butanol has been evaluated by considering different types of micro-organisms. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the most common yeast used for ethanol production from FL and FW due to high productivity and oxygen requirements (i.e., facultative anaerobic) and yields close to the theoretical value [151]. Zymomonas mobilis is another micro-organism (bacteria type) with great applicability to produce ethanol due to its anaerobic growth capacity, tolerance to inhibition by substrate, and metabolism through Entner (via Doudoroff) which promotes more biomass consumption and an increase in ethanol production using more carbon sources (e.g., glucose and xylose) [152]. Several alternatives have been evaluated for ethanol production from cocultures that promote enzyme production or the ability to use different substrates simultaneously. Ntaikou et al. [153] evaluated the cocultivation with Pichia stipitescepa CECT 1922 and S. Cerevisiae CECT 1339 for ethanol production from potato waste using hexoses and pentoses, obtaining yields of 0.15 L/g of raw material.

3.3.2. Biomaterials

Fermentation processes using FL and FW as raw materials can produce biomaterials such as biopolymers and biosurfactants. These products are biocompatible and biodegradable [154]. Then, several industrial applications related to the cosmetic, pharmaceutical, cleaning, medicine, and food sectors have been identified [155]. Moreover, the environmental impact of producing these biomaterials is low compared to those produced by chemical synthesis. Nevertheless, biopolymer and biosurfactant production has a common issue related to raw materials. Indeed, carbon sources (e.g., sugars and glycerol) have a relatively high cost since energy crops have been used (e.g., corn and wheat) [156]. On the other hand, synthetic materials have a more competitive price in the market. Table 4 presents information related to biomaterial production using different micro-organisms and operating conditions.

Research has aimed at producing biopolymers and biosurfactants when using FL (i.e., second-generation raw materials) as raw material [157]. Upstream processing is required since lignocellulosic materials have high recalcitrance for direct upgrading. Then, pretreatment must be done to reduce crystallinity and to improve enzymes and micro-organism accessibility. Despite the advances in this research field, FL has not been implemented at the commercial level to produce these biomaterials. On the other hand, FW is an interesting raw material from a theoretical point of view due to the high content of carbohydrates and fats. Nevertheless, few research papers have been published supporting or claiming reliable and feasible biomaterial production using FW. Thus, this is a research field highlighted by the authors since new methodologies and strategies for including FW-based processes are required. The main drawbacks of this raw material are related to non-standard composition, titer variability, and possible inhibition. On the other hand, downstream processing also requires a deep analysis due to a comprehensive study on product purification still being lacking.

Biopolymers are naturally produced by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Bacillus sp., Pseudomonas sp., Clostridium sp., Azotobacter sp.) [156]. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are produced by SSF and SMF. Poly 3-hydroxybutyric acid (PHB) is the most common PHA. Several process configurations have been explored to improve PHB production [158]. Indeed, batch, repeated batch, fed-batch, fed-batch with cells recycling, one-stage chemostat, two-stage chemostat, and multi-stage chemostat have been proposed for improving process productivity. Higher yields and productivities can be obtained using continuous processes since operating conditions such as carbon-to-nitrogen molar ratio, temperature, pH, and substrate concentration can be monitored.

Table 4.

Biomaterials obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

Table 4.

Biomaterials obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

| Micro-Organism | Water Activity | Oxygen Requirement | Product | Substrate | Operational Conditions | Yields and Productivity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pleurotus sapidus | SSF | Anaerobic | Nanocellulose | Food loss: Sunflower seed hulls | Control medium: 2 g/L malt extract, 0.2 g/L yeast extract, and 1 g/L saccharose. Temperature: 85 °C; Fermentation time: 3 h | Microcrystalline cellulose: 63.4%wt Nanocrystalline cellulose: 66.7%wt | [159] |

| Trichoderma reesei | SSF | Aerobic | Xylose | Food loss: Brewers spent grain | Fermentation: 3 days; pH: 7.00; Temperature: 30 °C; Brewers spent grain: 20 g/L; Stirring rate: 180 rpm; Inoculum concentration: 1 × 106 spores/mL; Sterile solution: 0.8%(w/v) NaCl, 0.05%(w/v) | Xylose: 3.83%wt (Xylose: 38.3 mg/g of Brewers’ spent grain) | [160] |

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | SSF | Aerobic | Poly γ-glutamic acid | Food loss: Soybean dregs | Continuous batch fermentation; Fermentation volume: 5 L; Initial moisture of substrate: 70%; Substrate load: 400 g (375.6 g fresh soybean dregs and 24.4 g molasses meal); Inoculum size: 12%; Fermentation temperature: 30 °C Initial pH: 8.0; Fermentation time: 72 h | Poly γ-glutamic acid: 6.58%wt (Poly γ-glutamic acid: 65.79 g/kg) | [161] |

| Activated sludge | SMF | Anaerobic | Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) | Food loss: Fermented cheese whey | Fermentation volume: 500 mL; Inoculum: Cheese whey ratio: 1:5; Inoculum load: 50 g Total Suspended Solids/L; Incubation time: 96 h; Stirring rate: 150 rpm; Fermentation temperature: 37 °C; pH: 5.5 | PHA: 28.2%wt (PHA: 28.2 g/L) | [61] |

| Xanthomonas citri | SSF | Aerobic | Xanthan | Food loss: Potato peel | Substrate load: 50 g; Temperature: 28 °C pH: 7.2; Time: 24 h | Xanthan: 5.80%wt (Xanthan: 2.90 g/50 g peel) | [162] |

| Haloferax mediterranei | SSF | Aerobic | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate): (P(3HB-co-3HV)) | Food loss: Cheese whey | Batch fermentation mode; Fermentation volume: 2 L; Temperature: 37 °C; pH: 7.2 Air flow rate: 1 vvm; Dissolved oxygen concentration: 20%; Stirring rate: 200–800 rpm | P(3HB-co-3HV): 9.6%wt (P(3HB-co-3HV): 9.6 g/L) | [163] |

| Recombinant Escherichia coli | SSF | Aerobic | Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) | Food loss: Corn steep liquor | Fermentation volume: 50 mL; Inoculum concentration: 0.01 g dry cell/L; Temperature: 37 °C; pH: 7.2; Antifoam concentration: 30µL/L; Incubation period: 48 h | PHB: 6.12%wt (PHB: 6.12 g/L) | [164] |

SSF: Solid-state fermentation, SMF: Submerged fermentation, IS: Immobilized systems.

Moreover, the continuous process contributes to economic feasibility due to high productivity and specific growth rates. Nevertheless, continuous fermentation trends towards microbial contamination [157]. Thus, a careful study of the possible implementation of this operating mode should be done. In addition, techno-economic and environmental analyses of different PHB process configurations need to be analyzed due to the lack of data in the open literature. Indeed, a deep analysis considering kinetic modeling and micro-organism recirculation should be analyzed to discover washout conditions and possible pathways for improving yields (see Table 4). Regarding raw materials used for PHB production, FL has been reported in the literature. For instance, potato processing waste, sugarcane bagasse, waste frying oil, palm oil mill effluent, and olive oil mill waste have been used to produce PHB. Titers vary from 5 g/L to 70 g/L. Finally, FW was also studied at the experimental level using diary waste, but a low yield was reported (i.e., 0.28 g/L) [154].

Xanthan gum (an anionic biopolymer) is another fermentation product. This compound has applications in the food and beverage industries. Xanthan gum concentration after the fermentation process is in the range of 2–4% [165]. In line with PHA and biosurfactant production, Xanthan gum fermentation requires strict conditions, since this process is sensitive to pH changes and inhibitor presence. Then, the same hotspots listed for biopolymers and biosurfactants can be applied here.

3.3.3. Organic Acids

Organic acids such as lactic acid, succinic acid, itaconic acid, acetic acid, and 3-Hydroxypropionic acid (3-HPA) are potential products obtained from FL and FW fermentation [166]. These organic acids have been considered to be building blocks/platforms since further processing can be applied to obtain high-added-value products (e.g., biomaterials). Organic acids constitute a key role in producing and commercializing several final products for food, pharmaceutical, and biomaterials industries. Research and development (R&D) has focused more on upgrading FL than FW since FL has a standard/homogenous composition over time compared to FW. Several research studies have addressed efforts to obtain the above-mentioned organic acids when using FL, such as winery, grape, and corn residues [167]. Nevertheless, FW upgrading via a fermentation process has been studied due to the high content of carbohydrates and lipids in the raw material.

Table 5 presents the yields, micro-organism, and organic acid type derived from FL and FW fermentation.

Lactic acid production has been one of the most studied processes since the demand for this organic acid has increased over the years. Indeed, lactic acid produced by fermentation is preferred over chemically produced lactic acid. This organic acid is the unique monomer used to produce biodegradable polymers (e.g., polylactic acid) [168]. Several wild and engineered strains have upgraded carbon sources such as glucose and glycerol. Solid submerged and solid-state fermentations have been applied at an industrial level as alternatives for this organic acid production.

Table 5.

Organic acids obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

Table 5.

Organic acids obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

| Micro-Organism | Water Activity | Oxygen Requirement | Product | Substrate | Operational Conditions | Yields and Productivity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillium echinulatum | SSF | Anaerobic | Lactic acid | Food loss: Rice husk | Fermentation volume: 1.0 L; pH: 6.0; Nutrients solution (g/L): proteose peptone, 10.0; yeast extract, 5.0; ammonium citrate, 2.0; and dipotassium phosphate, 2.0.; Temperature: 30 °C | Lactic acid: 12.69%wt (Lactic acid: 12.69 g/L) | [169] |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | SSF | Anaerobic | Lactic acid | Food loss: Brewer spent grains | Batch fermentation; Stirring rate: 15 rpm Fermentation volume: 300 mL; Brewer spent grains: 200 mL; Brewer yeast: 50 g/L Inoculum concentration: 5%(v/v); Temperature: 37 °C; pH: 6.2 | Lactic acid: 89%wt | [170] |

| Lactobacillus paracasei | SSF | Anaerobic | Lactic acid | Food loss: Molasses-enriched potato stillage | Batch fermentation (48 h) and Fed-batch fermentation (24 h); 200 mL of stillage + 32 g of molasses; pH: 6.5; Adaption media (g/L): Peptone, 10; meat extract, 10; yeast extract, 5; K2HPO4, 2; C2H9NaO5, 5; C6H17N3O7, 2, and 1 L of distillated water | Lactic acid: 89.0%wt (Lactic acid: 0.89 g/g) | [171] |

| Bacillus coagulans | SSF | Anaerobic | L-lactic acid | Food loss: Defatted rice bran | Batch fermentation; Fermentation volume: 1 L; Substrate load: 20%(w/w); Temperature: 52 °C; Stirring rate: 400 rpm; pH: 6; Inoculum concentration: 6%(v/v); Fermentation time: 25 h | Lactic acid yield: 90%wt Lactic acid productivity: 33.7%wt (Lactic acid productivity: 2.7 g/L-h) | [172] |

| Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus and Aspergillus niger | SSF and SMF | Aerobic | Lactic acid | Food loss: Dry corn stover | SSF: Fermentation time: 250 mL; Glucoamylase: 8%(w/w); Inoculum: 6%(v/v); Substrate: Chopped to a sized of 3–5 cm; Substrate load: 25 g (dry basis); Temperature: 35 °C; pH: 4.6; Stirring rate: 120 rpm; Time: 96 h SF: Fermented substrate was mixed with glucoamylase: 1850 U/g; pH: 5.3 | Lactic acid: 45.5%wt (Lactic acid: 45.5%w/w) | [173] |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | SSF | Aerobic | Citric acid, mannitol, arabitol, and erythritol | Food loss: Olive-mill wastewater | Fermentation volume: 250 mL; Substrate concentration: 8.98 g/L; Stirring rate: 180 rpm; Peptone: 1.0 g/L; Yeast extract: 1.0 g/L; pH: 5.0–6.0; Temperature: 28 °C; Fermentation time: 191 h | Citric acid: 27.0%wt Mannitol: 15.0%wt Arabitol: 5.0%wt Erythritol: 23.0%wt (g/g of raw material) Citric acid: 0.27 Mannitol: 0.15 Arabitol: 0.05 Erythritol: 0.23 | [174] |

| Aspergillus ornatus and Alternaria alternata | SSF | Aerobic | Citric acid | Food loss: Apple Pomace and peanut shell | Fermentation volume: 500 mL; Substrate load: 25 g; Substrate mixture ratio: 50:50; Moisture content: 50%; Nutritional ingredient: Arginine; Temperature: 30 °C pH: 5.0; Time: 48 h; Stirring rate: 180 rpm | Citric acid: 5.28%wt (Citric acid: 2.64 mg/mL) | [175] |

| Digested sludge inoculum | SSF | Anaerobic | Propionic acid | Food loss: Winery waste | CSTR fermentation; Fermentation volume: 50 L; Substrate: Inoculum ratio: 1:1; Inoculum concentration: 5 gVVS/L; Temperature: 35 °C; pH: 5.5 | Propionic acid: 50.7%wt (Propionic acid: 1.0 gCOD/L) | [176] |

| Digested sludge inoculum | SSF | Anaerobic | Propionic acid | Food loss: Meat and bone meal | Batch fermentation; Fermentation volume: 500 mL; Substrate concentration: 10 g COD/L; Inoculum concentration: 5 gVVS/L; Temperature: 55 °C; pH: 5.5; Fermentation time: 10 day | Propionic acid: 14.3%wt (Propionic acid: 1.43 gCOD/L) | [176] |

| Aspergillus awamori and Aspergillus oryzae. Actinobacillus succinogenes and Escherichia coli | SSF | Anaerobic | Succinic acid | Food loss: Mixed food waste and Bakery waste | Enzymatic hydrolysis: Substrate load: 8.5 g (dry weight); Inoculum concentration: A. awamori, 4.6 × 105 spores/mL; A. oryzae, 6.3 × 105 spores/mL; Temperature: 30 °C; Incubation period: 7 days Bacterial fermentation: Fermentation volume: 2.5 L; Hydrolysate volume: 1.5 L Inoculum size: 10%(v/v); Initial glucose concentration: 58 g/L; Temperature: 37 °C Stirring rate: 150 rpm; Time: 6 h | Succinic acid: 22.4%wt (Succinic acid: 22.4%w/w) | [177] |

| Actinobacillus succinogenes | SSF | Anaerobic | Succinic acid | Food Loss Bread loss | Bread was cut into cube: 1 cm3 Substrate load: 10 g; Inoculum concentration: 2.85 × 107 spores/mL; Temperature: 30 °C pH: 6.6–6.8; CO2 flow rate: 0.5 vvm; Stirring rate: 300 rpm; Time: 3 h | Succinic acid: 55.0%wt (Succinic acid: 0.55 g/g bread) | [178] |

| Rhizopus oryzae | SMF | Aerobic | Fumaric acid | Food loss: Apple pomace | Fermentation volume: 142.1 mL; Substrates concentration: 40 g/L of total solids; pH: 6; Temperature: 30 °C; Stirring rate: 200 rpm; Incubation time: 72 h | Fumaric acid: 3.58%wt (Fumaric acid: 0.35 g/L-h) | [179] |

| Rhizopus oryzae | SSF | Aerobic | Fumaric acid | Food loss: Apple pomace | Substrate load: 250 g; Inoculum concentration: 1 × 107 spores/g dry weight; Temperature: 30 °C; Time: 21 days | Fumaric acid: 5.2%wt | [179] |

| Rhizopus oryzae | SSF | Aerobic | Fumaric acid | Food waste: Obtained from university canteen | Substrate load: 106.36 g/L. Solid-liquid ratio: 1:10; Inoculum concentration: 20%(v/v); Temperature: 30 °C; Stirring speed: 180 rpm. Pressure: 4 MPa. Time: 150 min | Fumaric acid: 23.94%wt | [180] |

| Rhizopus arrhizus | SSF | Anaerobic | Fumaric acid | Food waste: Obtained from the dining hall university | Fermentation volume: 50 mL; Substrate particle size: 2–5 mm; Substrate load: 4.58 g/L; Temperature: 30 °C; Stirring speed: 200 rpm; Time: 168 h. Glucose: 80 g/L; | Fumaric acid: 32.68%wt | [181] |

| Bacillus subtilis | SSF | Anaerobic | Indole-3-acetic acid | Food loss: Cassava fibrous residue | Fermentation volume: 27 mL; Substrate load: 20 g; Moisture: 70% achieved with peptone (N 0.15%); Inoculum concentration: 1 × 106 CFU/mL); Temperature: 30 °C; pH: 7.00; Fermentation time: 10 days | Indole-3-acetic acid: 75.96%wt (Indole-3-acetic acid: 22.8 µg/g) | [182] |

| Providencia sp. | SSF | Anaerobic | Indole-3-acetic acid | Food waste: Obtained from food-waste compost | Fermentation volume: 200 mL; Inoculum concentration: 2% (v/v); NaCl concentration 4% (w/v); Temperature 25 ℃; Initial pH = 5; L-tryptophan concentration 3.0 g/L; Time: 12 h | Indole-3-acetic acid: 96.65%wt | [183] |

| Bacillus pumilus | SMF | Anaerobic | Gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, and p-Coumaric acid | Food loss: Soybean fermented food | Fermentation volume: 90 mL; Temperature: 37 °C; Inoculum concentration: 5%(w/w); Fermentation time: 60 h | Gallic acid: 37.8%wt Protocatechuic acid: 46.3%wt p-Coumaric acid: 1.5 × 10−4%wt (mg/kg) Gallic acid: 1012 Protocatechuic acid: 4.63 p-Coumaric acid: 0.15 | [184] |

| Ganoderma lipsiense | SSF | Anaerobic | Caffeic acid | Food waste: Obtained from university canteen | Fermentation volume: 75 mL; Medium moisture: 51%; mycelium suspension volume: 15 mL; Temperature: 28 °C; Time: 49 days; Substrate load: 25 g | Caffeic acid: 68.92%wt | [185] |

| Pediococcus Pentosaceus | SSF | Anaerobic | Ellagic acid | Food Loss Cloudberry juice | Fermentation volume: 15 L; Inoculum load: 1 × 106 CFU/g; Temperature: 30 °C; Incubation period: 14 days; Stirring rate: 130 rpm | Ellagic acid: 85%wt | [186] |

SSF: Solid-state fermentation, SMF: Submerged fermentation, IS: Immobilized systems.

Fermentation yields range between 0.45 g of lactic acid/g of glucose to 0.97 g of lactic acid/g of glucose in batch, fed-batch, and continuous mode [187]. Currently, lactic acid is produced from corn at the industrial level. Raw materials (i.e., carbon and nitrogen sources) account for 35% of the total operating cost of the process [166]. Then, alternative raw materials have been proposed as a strategy to decrease operational expenditure. Despite the recent advances related to lactic acid production using FW, the most suitable raw materials for processing are FL due to the standard composition and management. Then, agricultural and agro-industrial residues are attractive for implementation.

3-HPA is a structural isomer of lactic acid. Nevertheless, large-scale production using fermentative pathways has not been implemented commercially since hotspots related to titer, yield, and productivity must be overcome. Research efforts have been made to demonstrate the feasible production of 3-HPA when using different carbon sources, such as C6 sugars and glycerol [188]. Fermentation for producing 3-HPA involves using recombinant strains such as E. coli and K. pneumonia due to the need to improve hotspots related to metabolism [189]. This organic acid can be upgraded to acrylic acid, which has several applications in health care products, adhesives, and metal lubricants. In addition, 3-HPA is used to produce superabsorbent polymers [166]. The study of 3-HPA production still requires more effort to ensure a cheap raw material. FW has been proposed as an ideal substrate since these materials are rich in carbohydrates and fatty acids. However, few literature reports have addressed 3-HPA production using this raw material.

Finally, other organic acids such as citric acid, succinic acid, malic acid, and acetic acid also can be produced via FL or FW fermentation. These processes have been widely reported in the open literature. Nevertheless, chemical routes have been implemented instead of fermentative processes since high conversions are obtained when using synthetic chemical raw materials.

3.3.4. Aromatic Compounds

Aromatic compound production is carried out using three routes: (i) chemical synthesis; (ii) direct extraction from a natural matrix; and (iii) direct extraction from biotechnological processes (e.g., microbial cultures, use of enzymes and microbial cell cultures) [190]. The direct extraction of a natural matrix and the biotechnological route have gained great importance in recent years [191]. The main reason for this is that the aromatic compounds obtained by these routes can be labeled as “natural” and friendly to the environment [192].

The microbial culture route for aromatic compound production is carried out by bioconversion/biotransformation and fermentation [193]. In biotransformation, the micro-organism converts a precursor into an interest product through one or more reactions [194]. The transformation is performed by an enzyme complex that catalyzes the biotransformation reaction. Sale et al. [193] evaluated the ferulic acid biotransformation to vanillin from stereoselective or regioselective changes. This type of biotechnological route starts from the modification in the genomes of micro-organisms [195]. An example of this is the genetic modification of Escherichia coli with the gene-encoding lipoxygenase (obtained from Pleurotus sapidus) to convert valencene into the grapefruit flavor nootkatone [196]. The FRs analyzed under this transformation route are the AL (FL). However, biotransformation processes have only been analyzed using precursors, and not biomass directly [195].

Table 6 presents different studies aimed at the production of aromatic compounds from FL:

Table 6.

Aromatic compounds obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

In the fermentation routes to produce aromatic compounds, a complete metabolic pathway is involved [193]. The carbohydrate catabolism is carried out to produce primary metabolites and aromatic compounds [205]. One of the main limitations of aromatic compound production by fermentation is the need to support the initial growth of the micro-organism with glucose [206]. These limitations have been overcome with the implementation of SSF and mixing different FL. Aggelopoulos et al. [90] evaluated the production of volatile aroma compounds from AL mixed with Kluyveromyces marxiaunus and S. cerevisiae.

3.3.5. Foods and Feeds

Fermentative processes are applied for the production of foods (e.g., beverages), food additives (e.g., sweeteners), and feeds (e.g., protein and fibers). Fermentative processes play a key role in the food industry since microbial fermentation can help improve organoleptic properties by improving flavor and aroma. Cocoa bean fermentation is one of the most important stages for producing chocolate [207]. Indeed, cocoa bean fermentation contributes to the development of the chocolate flavor since a series of micro-organisms (e.g., bacteria and yeast) produce a wide range of organic compounds with special characteristics. Then, fermentation can be considered to be a fundamental activity in the food and feed industrial sector. Certainly, food fermentation is considered to be a food-processing technology due to process complexity and understanding [208].

Similar applications can be found in the open literature to produce yogurt, beer, cider, and wine, among others. On the other hand, carbon source (e.g., sugar) fermentation when using different micro-organisms can lead to the production of food additives such as sweeteners (e.g., all sugar alcohols), pigments, antibiotics, and amino acids [209]. Food additives can be produced using FL and FW as raw materials since both feedstocks have a high fermentable substrates content. Regarding FL, cane molasses has been used to produce isomaltulose using engineered Yarrowia lipolytica strain. A maximum titer and yield of 161.2 g/L and 0.96 g/g were obtained in fed-batch mode after an operation time of 3.5 days [210]. Another example is related to the sugar alcohol production (i.e., mannitol, xylitol, sorbitol, and erythritol). These compounds are produced using yeasts and bacteria. Sugar alcohol production has been researched widely when using different raw materials [211]. Nevertheless, most cases related to sweetener production are associated with FL since few research reports have studied FW as a potential raw material. This fact can be attributed to the raw material origin, as human products must guarantee security. Indeed, consumers probably would not consume sweeteners if they knew the raw materials used in the production process (e.g., organic kitchen food waste). Finally, feed products such as soluble dietary fiber can be produced via food-waste fermentation using Aspergillus oryzae [212]. These kinds of products are produced to improve the nutritional properties of feed.

Table 7 presents a list of substrates and micro-organisms used for food and feed production through fermentation.

Table 7.

Foods and feeds obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

3.3.6. Enzymes

Enzymes are essential when considering biomass processing, since these proteins break down structural polymer linkages to produce oligomers (e.g., disaccharides) and monomers (e.g., monomeric sugars). Indeed, enzymes have been the basis for proposing biomass upgrading to classical products such as ethanol and lactic acid [219]. Commercial enzymes constitute a cocktail/mixture of different proteins with specific functions. Commercial cellulases (e.g., Celluclast 1.5 L or CellicCTec2) are a mixture of endo-beta-1,4-glucanase (1,4-beta-D-glucan-glucanohydrolaza, E.C.3.2.1.4), exo-beta-1,4-glucanase (1,4-beta-D-glucan cellobiohydrolase, E.C.3.2.1.91) and beta-1,4-glucosidase (cellobiohydrolase, beta-D-glucoside glucohydrolase, E.C.3.2.1.21). This cocktail degrades cellulose to produce glucose for further fermentation. Nevertheless, few reports have focused on the improvement of the enzyme production process due to already existing and standard procedures implemented at the industrial level. In addition, few reports have focused on reviewing substrates used to produce enzymes. Therefore, this section aims to describe the enzyme production process, substrates, fermentation mode based on water activity, hotspots, and potential improvements based on the literature.

Enzymes are produced using fungus as a micro-organism. Aspergillus niger and Trichoderma ressei are the most used fungus to produce hydrolases (e.g., aminopeptidase, arabinofuranosidase, catalase, cellulase, glucanase, lactase, pectinase, and xylanase) [220]. Another fungus has been used to produce a wide variety of hydrolases (see Table 8). Hydrolases are the most common enzymes applied in biomass upgrading processes. The operating conditions of the fermentation process should be monitored to control pH and temperature, since proteins tend to denature. Enzyme production processes involve nine stages: (i) raw materials conditioning; (ii) sterilization; (iii) inoculum addition; (iv) fermentation; (v) flocculation; (vi) filtration or centrifugation; (vii) ultrafiltration; (viii) stabilization; and (ix) bacterial filtration [221]. Regardless of the fermentation type (i.e., SSF or SF), the above-mentioned steps could be considered to be similar stages. SSF has been the most applied process for enzyme production (see Table 8). Process optimization for the increase of productivities and yields has been addressed to improve the capability of fungus to degrade substrates based on mutagenesis and screening, the addition of stronger promoters, and multicopy strains [221]. Regarding downstream processing, membrane chromatography has been assessed as an alternative for fast enzyme purification. Nevertheless, this process has not been implemented at a commercial level.

FL and FW can be used as substrates in the enzyme production process (see Table 8). Indeed, Steudler et al. [222] reported the potential implementation of agricultural and agro-industrial residues as a substrate for enzyme production. High enzyme production yields were acquired when using wheat bran and straw. However, other raw materials have proved to be excellent substrates (e.g., orange peel waste) [221]. Therefore, related research aiming to find cheap and efficient raw materials for enzyme production is needed since the costs can account for more than 15% of the total operating costs of a bioprocess (e.g., cellulosic ethanol and lactic acid) [223]. Moreover, research and development must be addressed to obtain higher enzyme amounts and different activities. Indeed, DuPont published the patent US 8765.442 B2 describing a process for the production of an enzyme product with a plurality of enzyme activities obtained by fermentation of an Aspergillus sp. strain [224]. The patent describes the use of wheat brand (FL) to obtain an enzyme product comprising endo-polygalacturonase activity, exo-polygalacturonase activity, pectinesterase activity, pectin lyase activity, cellulase activity, xylanase activity, and arabinanase activity.

Table 8.

Enzymes obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

Table 8.

Enzymes obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

| Micro-Organism | Water Activity | Oxygen Requirement | Product | Substrate | Operational Conditions | Yields and Productivity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillium simplicissimum, | SSF | Aerobic | Lipase | Food loss: Castor bean waste; Jatropha curcas seed cake; Sugarcane bagasse, sunflower seed, and olive oil | Substrate particle size: 0.42–1.18 mm; Substrate load: 20 g; Temperature: 30 °C; Relative moisture: 95%; Fermentation time: 96 h | Lipase: 35.5%wt (Lipase: 155 U/g) | [225] |

| Lysinibacillus sp. | SSF | Aerobic | Laccase | Food waste: Whear bran | Fermentation volume: 250 mL; Inoculum volume: 0.5 mL; Temperature: 37 °C; Fermentation time: 72 h: Stirring rate: 160 rpm | Laccase: 18.9%wt | [226] |

| Bacillus halodurans | SSF | Aerobic | Fibrinolytic enzyme | Food waste: Banana peel, black gram husk, cow dung, paddy straw, rice bran, and wheat bran | Fermentation volume: 100 mL; Moisture: 80%; Temperature: 50 °C; pH: 8.32; Substrate load: 5.0 g; Inoculum concentration: 2–12% | Fibrinolytic enzyme: 13.7%wt (Fibrinolytic enzyme: 6851 U/g) | [227] |

| Aspergillus brasiliensis | SMF | Aerobic | Pectin lyase | Food waste: Corn steep liquor and orange peel | Agro-industrial medium: 160 g/L orange peel, 150 g/L corn steep liquor, and 300 g/L; Temperature: 30 °C; Initial pH: 5.5; Fermentation time: 100 h; Stirring rate: 180 rpm | Pectin lyase: 15.3%wt (Pectin lyase: 46 U/mL) | [228] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | SSF | Anaerobic | Protease | Food loss: Agro-industrial waste rice bran | Fermentation volume: 250 mL; Initial moisture content: 50%(w/w); Substrate load: 10 g; Temperature: 35 °C; pH: 7.0; Incubation period: 7 days; Stirring rate: 2000 rpm | Protease: 32.7%wt (Protease: 70.5 U/g) | [229] |

| Aspergillus niger | SSF | Anaerobic | Polygalactouronase | Food loss: Wheat bran, Coffee pulp | Wheat bran load: 1.5 g; Coffee pulp load: 23.1 g; Glucose concentration: 20 g/L; Distilled water volume: 70 mL; Temperature: 30 °C; pH: 4.5; Inoculum: 2 × 106 spores/mL; Time: 72 h; Stirring rate: 300 rpm | Polygalactouronase: 14.6%wt (Polygalactouronase: 515 U/L) | [230] |

| Bacillus subtilis | SSF | Aerobic | α-amylase | Food loss: Banana peel | Fermentation volume: 100 mL; Temperature: 35 °C; pH: 7.0; Incubation time: 24 h; Substrate moisture: 80%; | α-amylase: 6.38%wt (α-amylase: 7.26 U/mL/min) | [231] |

| Streptomyces sp. | SSF | Anaerobic | Cellulase | Food loss: Fruit waste | Substrate load: 10 g; Temperature: 40 °C pH: 5.0; Incubation period: 4 days | Cellulase: 13.6%wt (Cellulase: 20 U/mL/min) | [232] |

| Aspergillus awamori | SSF | Aerobic | Cellulase, xylanase, exo-polygalacturonase, and endo-polygalacturonase | Food loss: Grape pomace | Fermentation volume: 100 mL; Substrate load: 10 g; Medium moisture: 60% Inoculum concentration: 5 × 105 spores/g Temperature: 30 °C Incubation period: 25 h | Cellulase: 10%wt; Xylanase: 40%wt; Exo-polygalacturonase: 25%wt; Endo-polygalacturonase: 0.03%wt (IU/g dry substrate) Cellulase: 10; Xylanase: 40; Exo-polygalacturonase: 25; Endo-polygalacturonase: 0.03 | [233] |

| Penicillium viridicatum | SSF | Anaerobic | Polygalacturonase | Food loss: Wheat bran | Fermentation volume: 250 mL; Substrate load: 5 g; Inoculum load: 1 × 107 spores/g dry substrate; Temperature: 55 °C; Time: 14 days | Polygalacturonase: 30%wt (Polygalacturonase: 30 U/g) | [234] |

| Penicillium viridicatum | SSF | Anaerobic | Pectin lyase | Food loss: Orange bagasse | Fermentation volume: 250 mL; Substrate load: 5 g; Temperature: 50 °C; Time: 14 days | Pectin lyase: 40.0%wt (Pectin lyase: 2000 U/g) | [234] |

| Aspergillus oryzae | SSF | Aerobic | Pectinase | Food loss: Citrus pulp and sugarcane bagasse | Packed-bed bioreactor; Substrate load: 15 kg; Citrus pulp, 51.6%wt; sugarcane bagasse, 48.4%wt; Inoculum concentration: 4 × 107 spores/g dry substrate; Temperature: 30 °C; Aeration rate: 100 mL/min; Incubation time: 48 h | Pectinase: 2.46%wt (Pectinase: 37 U/g) | [235] |

| Penicillium chrysogenum and Trichhoderma viride | SSF | Anaerobic | Tannin acyl hydrolase or Tannase | Food waste: Grape peel | Fermentation volume: 250 mL; pH: 5.5; Temperature: 30 °C; Substrate load: 5 g; Incubation period: 96 h | Tannase: 0.96%wt (Tannase: 84 U/g/min) | [236] |

SSF: Solid-state fermentation, SMF: Submerged fermentation, IS: Immobilized systems.

Despite efforts to improve process yields, techno-economic assessment of enzyme production processes analyzing the influence of the composition, and downstream process configuration, has not been reported widely in the open literature. Then, an uncertainty related to real enzyme production costs based on different raw materials will continue. This research field can be explored with the aid of simulation tools.

3.3.7. Other Organic Compounds

Table 9 shows other organic compounds (e.g., volatile compounds, AGV, vitamins, antibiotics, and herbicide) obtained through FL and FW fermentation processes. The production of volatile compounds (i.e., esters, alcohols, carbonyl compounds, and organic acids) has been investigated from FL (AL and AgL) by mixing substrates to enhance carbohydrate content [90].

VFA (i.e., acetic, propionic, butyric, valeric, and hexanoic acids) are important intermediates during the acidogenesis stage in anaerobic digestion [237]. VFA are considered to be a platform product for the recent biosurfactants, bioflocculants and biopolymers [238]. VFA production can be influenced by operating conditions such as substrate concentration (specifically the C/N ratio), solid retention times, temperature, and pH, mainly. Unlike the anaerobic digestion directed to the production of biogas, the production of VFA is carried out in the first 36 h in batch processes [239]. In relation to the temperature, VFA production is favored between 25 and 55 °C. For FW, higher VFA production yields have been reported under acidic conditions (e.g., 5.25 to 11) [240]. In fact, higher VFA production yields have been reported when the pH is controlled at 6 during the entire digestion time.

In SSF, a wide range of products that can be obtained from substrates such as FL have been studied. Among these products, vitamin B complex (biological precursor/provitam of vitamin D2), pigments, and flavor synthesis has been considered [241]. Antibiotics production using SSF with FL has been analyzed from micro-organisms such as Streptomyces marinensi and S. fradiae. However, the main constraints for antibiotics production by SSF are the high production costs and low production yields. Pesticides have been products that have been studied from the FL fermentation. The most analyzed substrates are mainly grouped in AL and AgL such as potato peel and coffee peel, to be used for pest control in banana, sugar cane, coffee, and soybean crops. Some of the analyzed micro-organisms are Beauveria bassiana and Colleto-trichum truncatum.

Another type of process that has been investigated regarding FL fermentation has been the obtaining of antioxidants, antipigmentants and phenols. Razak et al. [242] evaluated the fermentation of rice bran using A. oryzae to obtain extracts with antioxidant and antiaging capacity. Liu et al. [243] analyzed the particle size and concentration of rice bran from Rhizopus oryzae for the production of biomass, protein, and phenolic compounds.

Table 9.

Other organic compounds obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

Table 9.

Other organic compounds obtained from FL and FW fermentation.

| Micro-Organism | Water Activity | Oxygen Requirement | Product | Substrate | Operational Conditions | Yields and Productivity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | SSF | Anaerobic | Esters, alcohols, carbonyl compounds, and organic acids. | Food loss: Orange pulp, molasses, brewer spent grains | Orange pulp volume: 100 mL; Molasses volume: 50 mL; Brewer spent grains: 70 g pH: 5.5; Temperature: 30 °C; Pressure: 1.5 Atm | Ethanol: 56.8%wt; 2,6-dimethyl-2- heptanol: 1.36%wt; 1-octanol: 0.10%wt; Phenylethyl alcohol: 3.1%wt; 3-heptanone: 0.19%wt; 2-heptanone: 0.021%wt; 2-methyl-4-heptanone: 0.0926%wt; 5-nonanone: 0.0052%wt; Cyclohexane- 1,1,3,5- tetramethyl: 0.0031%wt (mg/kg) Ethanol: 135.6; 2,6-dimethyl-2- heptanol: 35.8; 1-octanol: 10.2 Phenylethyl alcohol: 31.2; 3-heptanone: 19.0 2-heptanone: 20.6; 2-methyl-4-heptanone: 926.8; 5-nonanone: 51.8 Cyclohexane- 1,1,3,5- tetramethyl: 31.0 | [90] |