Abstract

A group signature scheme allows a user to sign a message anonymously on behalf of a group and provides accountability by using an opening authority who can “open” a signature and reveal the signer’s identity. Group signature schemes have been widely used in privacy-preserving applications, including anonymous attestation and anonymous authentication. Fully dynamic group signature schemes allow new members to join the group and existing members to be revoked if needed. Symmetric-key based group signature schemes are post-quantum group signatures whose security rely on the security of symmetric-key primitives, and cryptographic hash functions. In this paper, we design a symmetric-key based fully dynamic group signature scheme, called DGMT, that redesigns DGM (Buser et al. ESORICS 2019) and removes its two important shortcomings that limit its application in practice: (i) interaction with the group manager for signature verification, and (ii) the need for storing and managing an unacceptably large amount of data by the group manager. We prove security of DGMT (unforgeability, anonymity, and traceability) and give a full implementation of the system. Compared to all known post-quantum group signature schemes with the same security level, DGMT has the shortest signature size. We also analyze DGM signature revocation approach and show that despite its conceptual novelty, it has significant hidden costs that makes it much more costly than using the traditional revocation list approach.

1. Introduction

Digital signatures underpin trust and secure authentication and authorization over the internet. They have been used to construct certificates in public key infrastructure, credentials for user authentication and authorization, and signing transactions in electronic commerce and cryptocurrencies. Today’s widely used digital signatures, such as (EC)DSA and RSA signature scheme, rely on the hardness of two computational problems, Discrete Logarithm Problem and Integer Factorization Problem, that can be efficiently solved by the Shor’s quantum algorithm [1]. The prospect of the development of quantum computers, that potentially lead to the collapse of the cryptographic infrastructure of the Internet, has generated a flurry of research and development in academia and industry to design and develop post-quantum cryptographic systems, and has initiated standardization efforts around the world including NIST [2] and ETSI [3].

Post-quantum secure (PQ-secure) digital signature schemes provide security against adversaries with access to quantum computers. Known PQ-secure signature schemes have based their security on the hardness of computational problems for which no efficient quantum algorithm is known [4,5,6,7,8], or use only hash functions [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Security of the second approach against quantum computers primarily relies on the Grover’s search algorithm [15].

Hash-based signature schemes were first introduced in [12] as a One-Time Signature (OTS) scheme, using only hash functions and designed for signing a single message. Multi-message signature (MMS) schemes with short public key was proposed by Merkle by constructing a Merkle tree over a set of OTS public keys and using the root of the tree as the scheme’s public key [14]. Merke tree approach and its variations reduce the size of the public key but increase the signature size, as the OTS public key and the authentication path from the leaf to the root must be included in the signature. Winternitz One-Time Signature scheme (WOTS) [14] is a particularly attractive OTS design in which the public key of the OTS can be derived from the OTS signature and so need not be included in the MMS signature, when using Merkle tree approach. Winternitz signature scheme and its variations serve as the main building block of stateful hash-based signature schemes that have been standardized by NIST, including XMSS [9,16] and LMS [13].

Group Signature Schemes (GSS) [17] allow members of a group to sign on behalf of the group and provide anonymity and accountability for (group) members. In a GSS, a manager initializes the system and enrolls members to the group. A group member can sign anonymously on behalf of the group and their signature can be verified by the group public key. To provide accountability, signatures can be opened by the manager (or a separate opening authority) to reveal the identity of the signer. GSSs can be static where group membership is determined at the initialization time, partially dynamic that allow new members to join or existing members to be revoked after the initialization, and fully dynamic that support both joining new members and revoking existing members during the lifetime of the system [18,19,20]. GSSs and their variations have been used for Direct Anonymous Attestation in Trusted Platform Modules 1.2 [21], Enhanced Privacy Identification (EPID) [22], anonymous reputation systems [23], and digital rights management systems [24].

Symmetric-key based GSSs: Group Merkle (GM or G-Merkle) is the first hash-based GSS. GM is a static GSS [25] and is based on a hash-based multi-message signature scheme in which the public key is the root of a Merkle tree. The tree is constructed over the public keys of a set of OTSs where each OTS (hash of the) public key forming a leaf node of the tree. The manager assigns a random subset of leaves to each user. The innovation of GM is that it constructs the random subset by applying a strong pseudorandom permutation to the leaves of the tree which hides the association of the users to the leaves and ensures the users’ anonymity. The manager knows the secret key of the strong pseudorandom permutation and can reveal the identity of the signer, guaranteeing accountability. However, based on the GM’s implementation, it supports signatures and can accommodate up to users as each user must be allocated at least two OTSs.

: is a partially dynamic hash-based GSS [26] that uses GM approach and allows user revocation but not join. The scheme replaces the Merkle tree of GM with a multi-layer Merkle tree to increase the total number of signatures while keeping initialization time practical.

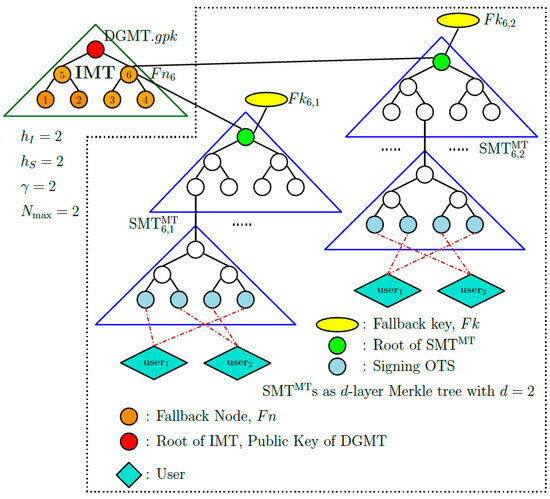

Dynamic GM (DGM) is a fully dynamic hash-based GSS that extends GM approach to support user join and revoke operations [27]. DGM uses an IMT/SMT tree structure that consists of two types of Merkle trees: (i) An Initial Merkle Tree (IMT) that is built on a set of random strings that serve as its leaves, and (ii) a set of Signing Merkle Trees (SMT), each built on the public keys of a set of OTSs. The root of each SMT is linked to an internal node of the IMT, referred to as a fallback node, using a fallback key that is part of the signature (We use the terminology from [27], particularly for terms like ‘fallback node’ and ‘fallback key’). See Section 3.2 for more details and Figure 3 as a concrete example. The number of fallback keys increases with the number of OTSs that DGM provides. The manager generates and stores fallback keys as new users join the group. During verification, the verifier queries the validity of a fallback key, that is part of the signature, by interacting with the manager. This IMT/SMT structure allows the manager to gradually construct the tree over the system’s lifetime and avoid the high computation cost of building the entire tree during the initialization phase. This, however, requires interaction with the group manager for verification. See Section 3.2 for more details on DGM.

DGM permits multiple SMTs per fallback node and so allows the total number of signatures provided by the system to grow. However, this is not formalized and is not part of the security proof. DGM also uses an innovative approach to user revocation that employs a Symmetric Puncturable Encryption scheme (SPE). In SPEs the decryption key can be updated and punctured on a desired input to prevent decryption of a ciphertext corresponding to that input. Revocation in DGM uses encryption and decryption functions of SPE to determine whether a signature is revoked or not. See Section 2.1 and Section 6 for more details on SPE and SPE-based revocation of DGM, respectively.

DGM shortcomings. DGM has two important shortcomings: (i) It requires interaction between the verifier and the manager for every signature verification, requiring the manager to be online continuously to respond to the verifiers’ queries on the validity of the fallback key which is a part of the signature; (ii) It requires the manager to store the index of each OTS assigned to every user in order to “open" the signatures (“Openning a signature” is a functionality in group signature that allows the group manager to find the identity of the signer of a signature. See Section 3 for details) and revoke the users, leading to a storage size that grows linearly with the total number of signatures generated by the scheme, denoted by . Additionally, the manager must store all fallback keys to verify them for users. For instance, to support OTSs, the manager would need to store leaf node indexes for signature opening and revocation, along with fallback keys, amounting to approximately Terabytes of storage [26]. This storage demand is unacceptably large, making it impractical for real-world applications.

Another less obvious drawback of DGM that is uncovered by our work is the very inefficient approach to revocation. DGM SPE-based approach to revocation although appears novel, incurs significant cost. See Section 6.

1.1. Our Contributions

In this work, we propose a symmetric-key based fully dynamic group signature scheme, called DGMT, that addresses the design shortcomings of DGM, and implements and evaluates its performance. Our main contributions are as follows.

1—A new tree structure. In all existing symmetric-key based GSSs discussed above, a virtual tree is constructed on a set of leaves that each corresponds to the public key of an OTS. The root of this tree is the GSS’s public key. The innovation of each system is in the way the tree leaves are managed during assignment and revocation, with the goal of providing user anonymity and accountability, and security and efficiency for the GSS. We construct a virtual tree on the set of OTSs that extends the IMT/SMT structure of DGM to and explicitly uses multiple per each internal node. The tree is designed to accommodate the required total number of signatures, , using a relatively small number of fallback keys. This allows the list of fallback keys to be generated and published during initialization (e.g., on a public bulletin board). The verifier can directly verify a signature by accessing the published information without the need to interact with the manager.

2—Reducing server storage. We design a new signature assignment algorithm where the manager’s storage is proportional to the maximum number of users, denoted by , rather than the total number of signatures . This significantly reduces the manager’s storage requirements, as each user is typically associated with a large number of OTSs. To achieve this, we assign a fixed, unique (and disjoint) interval of the list for an integer , to each user, and use a strong pseudorandom permutation to map the intervals to (pseudo)random leaves of the signature tree.

3—Implementation. We provide a full implementation of DGMT and all its algorithms. The software is written in C language, which is the NIST-recommended reference language, and the code is available at https://github.com/submissionOfCode/DGMT_ref, accessed on 19 November 2024. In addition to signature and verification algorithms, we have implemented key management algorithms, that consist of the initial key assignment, and user join and revocation. Key generation, and storage that support signature opening, and management of revocation list are the most complex parts of our code (DGM only provides implementation of the signing and verification algorithms).

For user revocation, DGMT uses a public revocation list. In Section 6, we analyse the user revocation approach of DGM that is based on SPE, and compare it with DGMT approach, demonstrating that DGM’s approach is significantly more costly in both computation and storage cost. Table A1 summarizes our results. In Appendix A, we show an alternative way of using SPE-based revocation in DGM which improves its efficiency and reduces the cost of revocation.

1.2. Related Work

To provide combined anonymity and accountability, symmetric-key based group signature schemes have used two approaches. The schemes in [25,26,27,28] use multi-time hash-based signature schemes together with pseudorandom permutations and/or symmetric-key encryption. The group public key is the root of a Merkle tree that is constructed over a set of leaves where each leaf corresponds to an OTS public key. The group manager allocates a “random’’ subset of leaves to each user and provides them with the secret keys of the allocated OTSs and the corresponding authentication paths to the root of the Merkle tree. The user uses one OTS and its associated authentication path at most once. DGM and allow the user to request additional OTS keys from the group manager by presenting their secret credentials, that are obtained during enrollment, to authenticate themselves. The schemes in [22,29,30] also use symmetric-key primitives and Merkle tree but employ Non-Interactive Zero-Knowledge (NIZK) proofs to construct the signature. We note that the scheme in [22] is an EPID and does not provide opening function to link a signature to a user, and the scheme in [30] is a static group signature. The scheme in [29] however is a fully dynamic symmetric-key based group signature that uses a hybrid approach: it uses a multi-time hash-based signature scheme, that is a modified version of (Stateless Practical Hash-based Incredibly Nice Cryptographic Signatures) [31], and is optimized for multiparty computation, and a NIZK to achieve anonymity. In Section 4.1 we give a comparison of DGM and DGMT algorithms, and in Section 1.2.1 give a more detailed look at Sphinx-in-the-Head (SiTH) [29] and its comparison with DGMT.

Table 1 summarizes comparison of all known symmetric-key based group signature schemes. All rows except the last row of the Table 1 are sourced from Table 1 in [29].

Table 1.

A Comparison of Hash-Based Group Signature Schemes.

1.2.1. Sphinx-in-the-Head

Sphinx-in-the-Head (SiTH) is a post-quantum fully-dynamic symmetric-key based group signature scheme. It uses a new mult-message hash-based signature scheme which is a modification of with the goal of making it more “friendly” for MPC (multiparty computation) that is needed for NIZK that is used in the scheme.

SiTH splits the role of the manager between a group issuer and a group tracer each receiving a corresponding private key from the user, preventing each of the two authorities to “frame” the user by generating a signature on their behalf, and hence providing non-frameability. This makes SiTH unique among other post-quantum symmetric-key based full-dynamic group signature schemes that use a single trusted group manager and do not provide non-frameability. SiTH scheme uses NIZK that allows the user to prove to the verifier a set of relations that are defined by its secret values, the signed message, and the published values of the system. Using NIZK results in a much slower signature generation and verification time, and a significantly larger signature size, compared to DGMT.

Similar to DGMT, SiTH uses a revocation list to keep track of the revoked users. The revocation list will include the secret tracing key of the user and so revokes all the signatures of the user, including the past ones. Authors noted that SiTH can be made forward anonymous by including the hash of the private tracing key in the revocation list. This however increases the computation cost of the signer who must show that the signing key has not been revoked.

In DGMT however the signatures are individually revoked. In our revocation algorithm we will include all signatures of a revoked user to the revocation list and so effectively revoke all signatures of the user. DGMT, however, can provide forward anonymity by revoking the signatures individually. This is by including the output of the strong pseudorandom permutation on the index of the revoked OTSs and all the remaining keys of the user, leaving out its past signatures. Thus will require minor changes to the current algorithms (e.g., “revoked” flag) that will not affect security.

1.2.2. DGMT and Other Post-Quantum GSSs

There is a large body of research on Lattice-based GSSs including static [4,33,34,35], partially dynamic [36,37,38], and fully dynamic lattice-based GSSs [39]. There are also constructions of code-based [40,41] and isogeny-based [4] GSS. Table 2 gives a comparison of signature sizes of the most efficient known post-quantum GSSs. Rows 3–5 of the table are from Table 1 in [4]. All schemes except DGMT and SiTH are static. The only fully dynamic GSS based on a computational assumption is the lattice-based GSS presented in [39]. However, it is not included in the table as its signature size is provided only in asymptotic terms, specifically bits, where represents the security parameter and N denotes the group size. As seen in the table, DGMT has the shortest signature size among all known schemes.

Table 2.

Signature size of the most efficient post-quantum GSSs, given in Kilobyte (KB). The signature sizes of the GSSs [4,29,33,40] depend on the number of users (group size), denoted by N. To show how many users are accommodated in each scheme, we consider .

1.3. Organization

Section 2 is preliminaries and Section 3 introduces a security model for fully dynamic symmetric-key based GSS. Section 4 gives the construction of DGMT, followed by the presentation of its security proof in Section 5. An analysis of the revocation using SPE in DGM is provided in Section 6. Section 7 is the implementation of DGMT and its experimental results. Appendix A gives a more efficient SPE-based revocation method for DGM, and Appendix B outlines an approach for reducing setup time in DGMT.

1.4. Notations

Let be the set of positive integers and be the security parameter. For two given integers , we denote the representation of a in base b by , and for , we denote the set by . For a given list L, we denote the n-th element of this list by . For two given strings x and y, we denote their concatenation by . If S is a set or a list, we denote its size by and the operation of randomly selecting an element x from S by . We write for an algorithm A that runs on input a and outputs x. We call a function negligible in the security parameter if for every polynomial and all sufficiently large values of , holds. is the ceiling function. For a given adversary and , , indicates that the adversary is given access to the oracles .

2. Preliminaries

In the following, we recall some cryptographic primitives [43,44,45,46]. Let and be two polynomials and be the security parameter.

One-way Function (OWF): A function is one-way if (i) for all , is efficiently computable, and (ii) it is hard to invert the function; that is for every Probabilistic Polynomial Time (PPT) adversary

is negligible in terms of .

Pseudorandom Function (PRF): A function

is pseudorandom if (i) for all k and x, is efficiently computable, and (ii) for any PPT adversary

is negligible in terms of , where and f is chosen randomly from the set of all functions mapping bits to bits.

Strong Pseudorandom Permutation (SPRP): A function

is a strong pseudorandom permutation if (i) for all k and x, and is efficiently computable, where , and (ii) for any PPT adversary

is negligible in terms of , where and is chosen randomly from the set of all permutations on .

Collision-resistant Hash Function (CRH): A set of functions

is a family of collision-resistant hash functions if (i) for all key and , is efficiently computable, (ii) for all PPT adversaries

is negligible in terms of .

Symmetric Key Encryption: A symmetric key encryption scheme is a tuple of polynomial-time algorithms where the key generation algorithm generates a random -bit key , and the encryption and decryption algorithms work as follows. The encryption algorithm encrypts a message m into the ciphertext c as , and the decryption algorithm decrypts a ciphertext c into the plaintext m as . The correctness property of says that .

2.1. Symmetric Puncturable Encryption Scheme (SPE)

DGM uses an SPE-based revocation scheme. To provide a concrete analysis of DGM revocation algorithm, we recall the SPE algorithm that was proposed in [47] and used in DGM. The construction uses the puncturable pseudorandom function (Pun-PRF) given in [48].

Let , and be the set of key space, punctured key space, output space, and tag space (or input) of the Pun-PRF, respectively. Let be a PRF. A Pun-PRF F, constructed from is a PRF with a pair of algorithms defined as follows: takes a key and a tag , and outputs a punctured key . The evaluation function takes a punctured key and a tag , computes if is not punctured at tag , and outputs fail (⊥), otherwise. That is,

A Construction for SPE. A symmetric d-puncturable encryption scheme is a tuple of algorithms

that allows the input key to be punctured on up to d tags. The master key remains unchanged. The encryption key is computed once but the decryption key is updated with each puncturing of a tag. The construction in [47] uses three building blocks: (i) a family of collision-resistant hash functions (ii) a symmetric key encryption system with key space and (iii) a PRF as defined above.

The initial decryption key of is the same as the encryption key , that is . The decryption key, however, is updated with each punctured tag . algorithms are outlined below.

- The algorithm takes the security parameter and and outputs the master encryption key , where .

- The algorithm takes the encryption key , message m and tag t, and outputs the ciphertext .

- The Decryption algorithm uses a punctured key, a ciphertext, and a tag as inputs and outputs a ciphertext or failure. First, we describe how updates the decryption key, and then how to decrypt the ciphertext.

- The algorithm updates the decryption key for the i-th punctured tag, given the previous key and the associated set of punctured tags. It takes , where for and , for the set of tags , and outputs . is defined recursively below.

- The algorithm takes the , the ciphertext and a tag t, and outputs the plaintext as follows. If , compute for .

2.2. One-Time Signature (OTS)

An OTS scheme is a digital signature scheme that is designed for signing a single message. It consists of three polynomial-time algorithms , which operate as follows

- . This algorithm generates a key pair , where is the secret key and is the public key.

- . This algorithm signs a message m with a secret key and outputs a valid digital signature .

- . This is a deterministic algorithm that checks the validity of the signature on message m using . outputs 1 if the message and signature pair is valid, otherwise, it outputs 0.

An OTS scheme is called existentially unforgeable under chosen message attack (EU-CMA) if for any PPT adversary

is negligible in terms of [10].

Winternitz One-time Signature (WOTS) is one of the most efficient OTS schemes, designed for both lightweight performance and strong security.

Let be a one-way function, be a hash function chosen randomly from the collision-resistant hash function family , and be the i-fold iteration function of f for every , i.e., for all if , , and (From now on, for simplicity, we only write rather than .). WOTS relies on two key parameters: the security parameter and the Winternitz parameter w. These parameters are used to define the following quantities:

WOTS consists of three algorithms

and works as follows.

The key generation algorithm produces a secret key , where for all , and computes the public key , where for all .

For a given message m, this sginng algorithm first computes and represents d in base as . Then, it computes the checksum and appends to to obtain

The signature on message m is , where

The verification algorithm computes using the message m as done in the signing algorithm . It verifies the signature by outputting 1 if

otherwise, it outputs 0.

2.3. Merkle Tree and Multi-Message Signature Scheme (MSS)

A Merkle tree is a binary tree in which every leaf node is the hash value of a data block, and each non-leaf node is the hash value of the concatenation of its two children. The root of the Merkle tree, also known as the Merkle root, serves as a compact representation of the entire dataset, that can be used to provide membership proof for the dataset elements. This structure efficiently verifies the integrity of any data block using a logarithmic number of hash operations and a comparison.

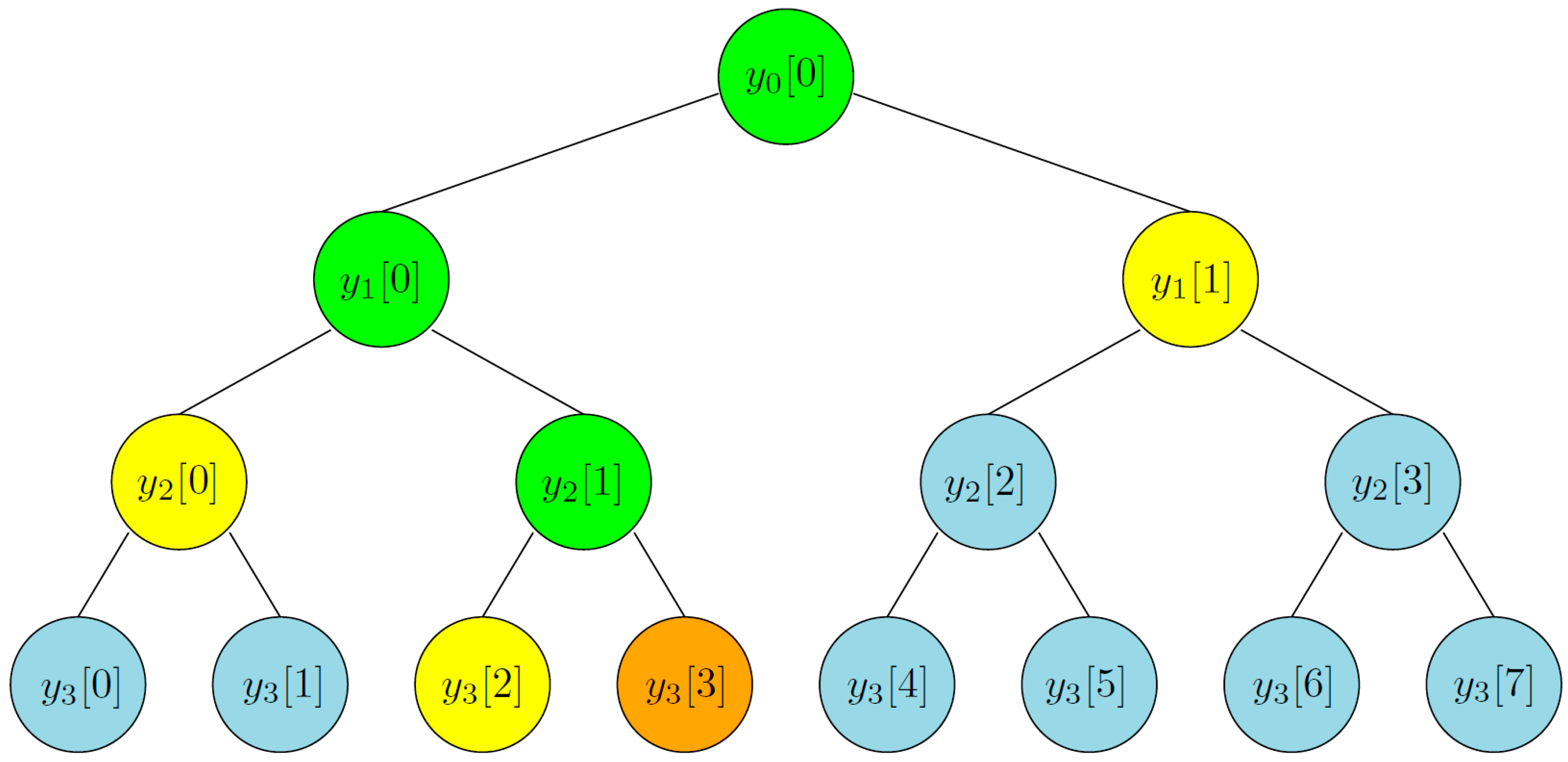

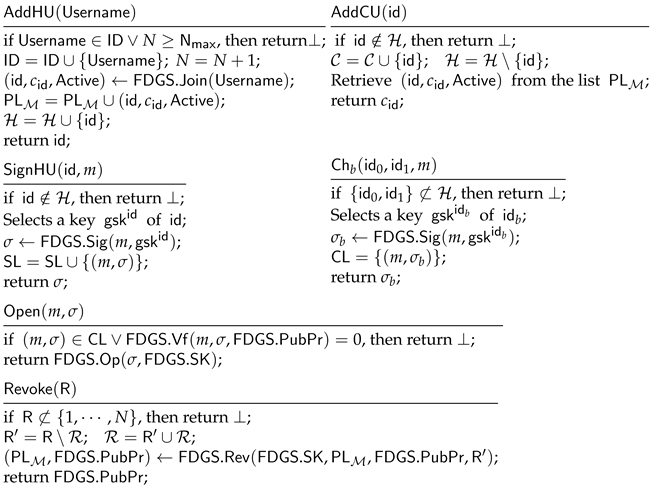

Figure 1 gives an example of a Merkle tree of height 3 constructed on 8 data blocks. The leaf nodes , , are the hash values of the data blocks and all the other nodes are computed as , where , , and is chosen randomly from the collision-resistant hash function family . To verify the membership of a data block, say (marked in orange), we provide the authentication path that is the sibling nodes of the nodes on the path from the mentioned data block to the root. For example the authentication path for is the set (marked in yellow). Now we can sequentially compute the nodes and (marked in green) which are on the path from to root . By comparing the computed root and published root, we can determine the membership of a data block.

Figure 1.

A Merkle tree of height 3.

Multimessage signaure scheme (MSS). To construct an MSS that supports up to signatures and has a short public key, Merkle [14] proposed to construct a Merkle tree on the hash values of the public keys of the set OTSs that are used in the signature, and use the root of the tree as the MSS public key. Specifically, for , the i-th leaf node is defined as , where is the i-th OTS key pair. For and , the i-th node at height j is computed as . The root of the Merkle tree, , acts as the public key of the scheme.

MSS uses leaf nodes of the Merkle tree to sign messages. The signature of a message m, using the i-th OTS is , where , and is authentication path for the i-leaf node, that is . To verify the signature on the message m, the verifier first verifies the by the algorithm and upon success they compute the root of the Merkle tree using the authentication path and . If the computed root is the same as the given public key , signature will be accepted.

Remark 1.

Using WOTS in a multi-message signature scheme removes the need for including the public key of the OTS in the signature. The signature of message m using the WOTS key pair is , where . To verify the message-signature pair , the verifier computes to derive the corresponding leaf node , and verifies if the computed leaf node and the authentication path matches the root of the Merkle tree, . If the match succeeds the signature σ is accepted.

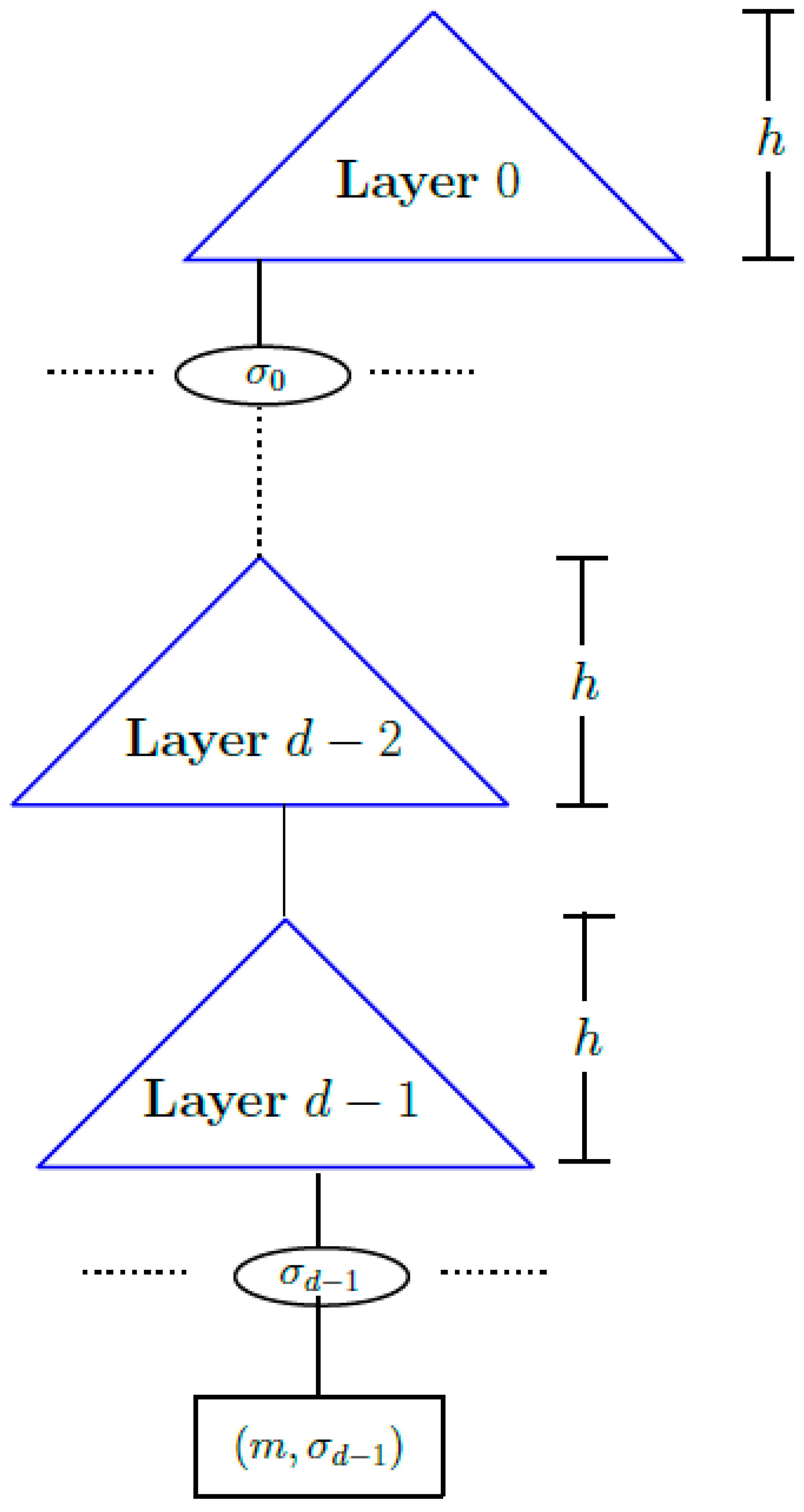

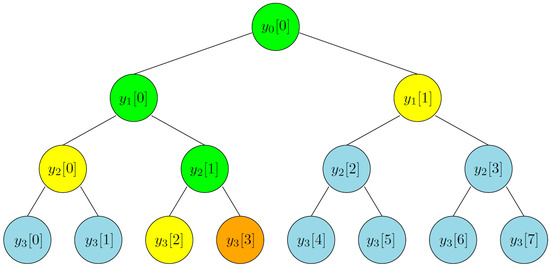

Multi-tree structure. As we discussed above, constructing an MSS using a Merkle tree requires deriving the public key by computing all the leaves of the tree first. For a large number , this would require a significant amount of initial computation and storage. A d-layer Merkle tree reduces the initial computation required for a large number by constructing the tree gradually [49].

An overview of a d-layer Merkle tree is shown in Figure 2. The root of the Layer 0 Merkle tree is the public key of the signature scheme and to compute the public key, only the topmost layer of the multi-tree has to be constructed. Every leaf node of a Merkle tree of layer signs a message, and every leaf node of the sub-trees of the layer signs the Merkle root of a sub-tree of the layer below, like and in Figure 2, respectively. Thus, each signature of MSS in a multi-tree structure contains d OTS signatures, one for each layer. Consequently, verifying an MSS signature in a multi-tree structure includes the cost of verifying d OTS signatures.

Figure 2.

A d-layer Merkle tree.

3. Fully Dynamic Group Signature

In this section, we describe a model of a fully dynamic group signature (). Our model is based on [19,20] and is adapted to fully dynamic symmetric-key based GSS [27]. Similar to [27] (i) we consider a single trusted authority for key generation and group management (i.e., join and revoke), as well as opening of signatures, and (ii) include a request subroutine that allows users to request new keys when their existing keys are run out.

Our security model is based on [19,20,50] and loosely follows [27]. In particular, we adopt the anonymity notion that was introduced in [50] and do not allow the adversary to corrupt the manager or the two selected honest users in the anonymity game.

A is composed of three types of entities:

- A Trusted manager, denoted by , is the central authority responsible for the perfect functioning of the group. allows new members to join the group, can reveal the identity of a signer, and can revoke the signing ability of misbehaved members and their generated signatures.

- Members/users anonymously sign messages on behalf of the group.

- Verifier verifies the validity of a group signature using only the public parameters.

Let be the security parameter and be the setup parameters. A consists of the following polynomial-time algorithms.

- The manager runs this algorithm to generate the manager’s secret key , including the manager master secret key and other group secret information, and the public parameters , including the group public key and other group public information that are necessary for verifying signatures.

- This is an interactive joining protocol between a user with identity , and the manager . In line with the model in [19], the communication occurs over secure (i.e., private and authenticated) channels, with the user initiating the protocol by sending their identity . Let represent the list of identities of users who have already joined the group and denote the maximum number of users the system supports. Upon receiving the identity , if or , the algorithm outputs ⊥. Otherwise, i.e., if and , the manager selects the smallest unassigned identifier with and generates a corresponding secret value and sends to the user. Then, stores(i) in a private list , where indicates that the user is valid, and (ii) the user’s identity as the -th element in the list , i.e., . Thus knowing the identifier allows the manager to retrieve the identity and vice versa. Two lists and are both initially empty and is private. When a user with identifier needs new keys, the user proves their identity by securely transmitting to through the secure channel. If , the manager sends new keys to the user through the secure channel.

- This algorithm is run by a user with identifier . It takes a message m and a key and generates a group signature .

- This is a deterministic verification algorithm run by a verifier. It takes as input a message m, a group signature , and the public parameters , and outputs 1 if is a valid group signature on m with respect to , and 0 otherwise.

- This deterministic opening algorithm is run by . It takes a valid group signature and the manager’s secret key , and outputs either the identifier of the user who generated , or ⊥ if the signature cannot be attributed to any specific user. With , the manager can retrieve the identity of the user by looking up the -th entry in the list , where is stored.

- The manager runs this algorithm to revoke users with identifiers in a set and invalidate their signatures. It takes as input a set , the manager’s secret key , the private list , and the public parameters , and updates both the public parameters and the private list . Specifically, for each , the manager replaces with in , preventing these users from requesting further keys.

3.1. Fully Dynamic Group Signature: Security Model

A fully dynamic group signature must satisfy four properties: Correctness, Unforgeability, Anonymity, and Traceability. Each of these properties is defined using the game, where each game is defined between a PPT adversary denoted by and a Challenger. Each of these properties is quantified by the success probability of in its game. In these games, the adversary has access to various oracles, each specifying their capabilities, which can be invoked a polynomially many times during the game.

We first describe the oracles in Table 3, and then in Definition 1 formally define the security properties of the signature scheme. The corresponding security experiments are given in Table 4. In the following, the notations , , and denote the set of honest, corrupted, and revoked users, respectively. N, , , and denote the number of users who have already joined the group, the max number of users that the group supports, the list of identities of users (i.e., s of the joined users) and the private list of manager. Also, and indicate the challenging list and the signing list.

Table 3.

Oracles.

Table 4.

Experiments.

- This oracle simulates the join protocol between a user with identity and the manager . If and , this oracle adds this user to the group as an honest user, i.e., adds to the private list and stores the user’s identity as the -th element in the list , where is the smallest unassigned identifier in . Finally, it returns to the adversary . does not learn .

- This oracle allows the adversary to corrupt an honest user with identifier . It adds to and removes from and finally returns the secret value to , enabling to communicate with the manager and receive this user’s keys from .

- This oracle allows the adversary to revoke the set of users by updating the private list and the public parameters . Specifically, for any , will be replaced with in , preventing these s from requesting further keys. Also, it invalidates their previously generated signatures by updating .

- This oracle takes the identifiers and of two honest users along with a message m, then randomly selects a bit b and outputs the signature on m by an unused secret key of the user . It keeps in the challenge list to prevent from calling the opening oracle on in the Anonymity experiment.

- This oracle takes as input a pair . If is a valid signature on m and , it returns , which is either the identifier of the user who produced the signature , or ⊥ if cannot be attributed to any user.

- This oracle takes as input an identifier and a message m. If this user is honest, it returns , where is a secret key of this user. The oracle also adds to the signing list to prevent from using in the Unforgeability experiment.

The Correctness property ensures that even if the adversary corrupts a set of users (possibly all except one), the honest user can successfully enroll and create valid signatures that can be traced back to them. The Unforgeability property ensures that the adversary cannot produce a valid signature that can be falsely attributed to an honest user, even if the adversary corrupts the rest of the users. Anonymity is defined through an indistinguishability experiment between the adversary and the challenger. In this experiment, the adversary knows the secret keys of all users except two. The Anonymity property requires that the adversary has only a negligible advantage in distinguishing a signature generated by randomly selecting one of the two identifiers and using the corresponding private key to sign the message. Finally, the Traceability property ensures that every valid signature is linked to a user.

Definition 1.

For any security parameter and for any PPT adversary , we say that an provides:

- 1.

- Correctness if there exists a negligible function such that

- 2.

- Unforgeability if there exists a negligible function such that

- 3.

- Anonymity if there exists a negligible function such that

- 4.

- Traceability if there exists a negligible function such that

where , , and are defined in Table 4.

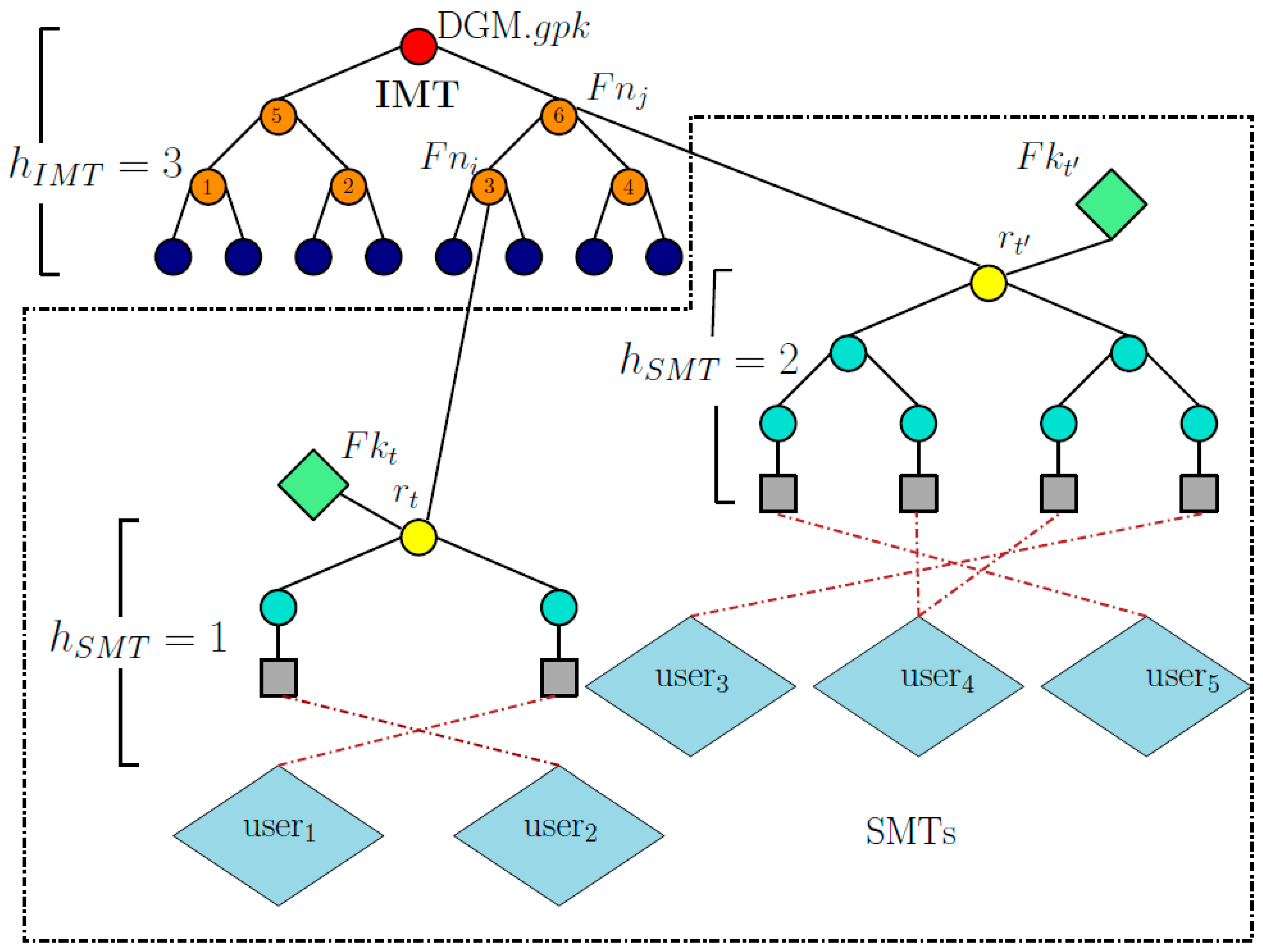

3.2. An Overview of

DGM is a fully dynamic group signature scheme based on symmetric primitives that uses a collision-resistant hash function , an scheme, a symmetric puncturable encryption scheme , and a symmetric key encryption scheme . DGM employs two types of Merkle trees: One Initial Merkle tree (IMT) and multiple Signing Merkle trees (SMT). This IMT/SMT structure allows the manager to gradually construct the tree, avoiding the unacceptable computational cost of building the entire tree during the setup phase. In the following, we review DGM and mention its main shortcomings. See [27] for further details.

In DGM, the IMT is of height 20 and its leaf nodes are randomly chosen strings. The root of the IMT is the group public key . SMTs are variable-height Merkle trees and their leaf nodes correspond to the OTSs that are used to sign messages by users. Each SMT is connected to only one internal node of the IMT. While DGM allows multiple SMTs per fallback node, this is not formalized or included in the security proof. The height of an SMT is equal to , where is the height of the corresponding internal node in the IMT. When a user requires B signing keys, they send a request to the manager, who randomly selects B internal nodes from the IMT and allocates the next available B OTSs from the B SMTs linked to those internal nodes. If an SMT has no available OTS, the manager generates a new SMT, links it to the corresponding internal node, and assigns an OTS from the newly created SMT.

SMT Generation. SMTs are generated gradually and linked randomly to the internal nodes of IMT and their leaf nodes will be distributed among the users. Let the height of the t-th SMT be . The DGM manager generates OTS key pairs for , and shuffles the leaf nodes of this SMT, indexed by , using the symmetric encryption scheme . More precisely, the leaf nodes are constructed as , where , with being the manager’s secret key. These nodes are then sorted in increasing order based on their values for . We note that after sorting the leaf nodes, the l-th leaf node will be located at index .

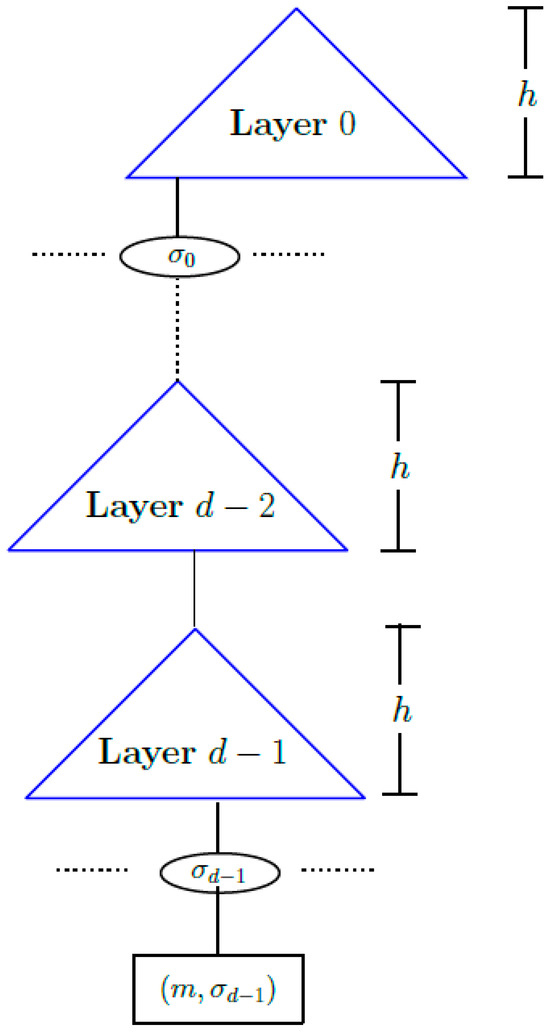

Let be the root of the t-th SMT, which is connected to an internal node of the IMT, denoted by (called fallback node), using a fallback key (See Figure 3). The signature of a message m by is

where i is the index of fallback node , is the index of the leaf node of the OTS key pair after sorting the leaf nodes, , and is the authentication path from the leaf node with index in SMT to the root of IMT. See Figure 3 for the IMT/SMT structure of DMG.

Figure 3.

IMT/SMT structure of DGM. The red node represents the group public key , the orange nodes represent the fallback nodes , the green nodes and represent the fallback keys, and the yellow nodes are the root of the s. The fallback key is computed as , where is the key.

DGM Limitations. There are two main shortcomings in DGM. First, during verification, the verifier must interact with the manager to check the validity of the fallback key , requiring the manager to be always online. This creates a system bottleneck and a single point of failure. Second, the manager must maintain a list containing all the allocated to users for the purpose of opening signatures via list-based searches, and revoking users. Thus, the manager’s storage grows linearly with the total number of signatures in the system and becomes unacceptably large when a large number of signatures is required. For instance, to accommodate OTSs, the manager requires Terabytes of storage (see [26] for details).

4. DGMT: A Flexible Fully Dynamic Symmetric-Key Based GSS

DGMT is an improved version of DGM that removes DGM’s notable shortcomings, such as the need for interactive verification and the unreasonable storage requirements proportional to , the total number of supported signatures. In this section, we first present an overview of DGMT in Section 4.1, then explain the details of the DGMT’s tree construction and its algorithms in Section 4.2 and Section 4.3, respectively. Finally, we discuss the typical parameters of DGMT in Section 4.4. The main symbols used in DGMT are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

List of Symbols.

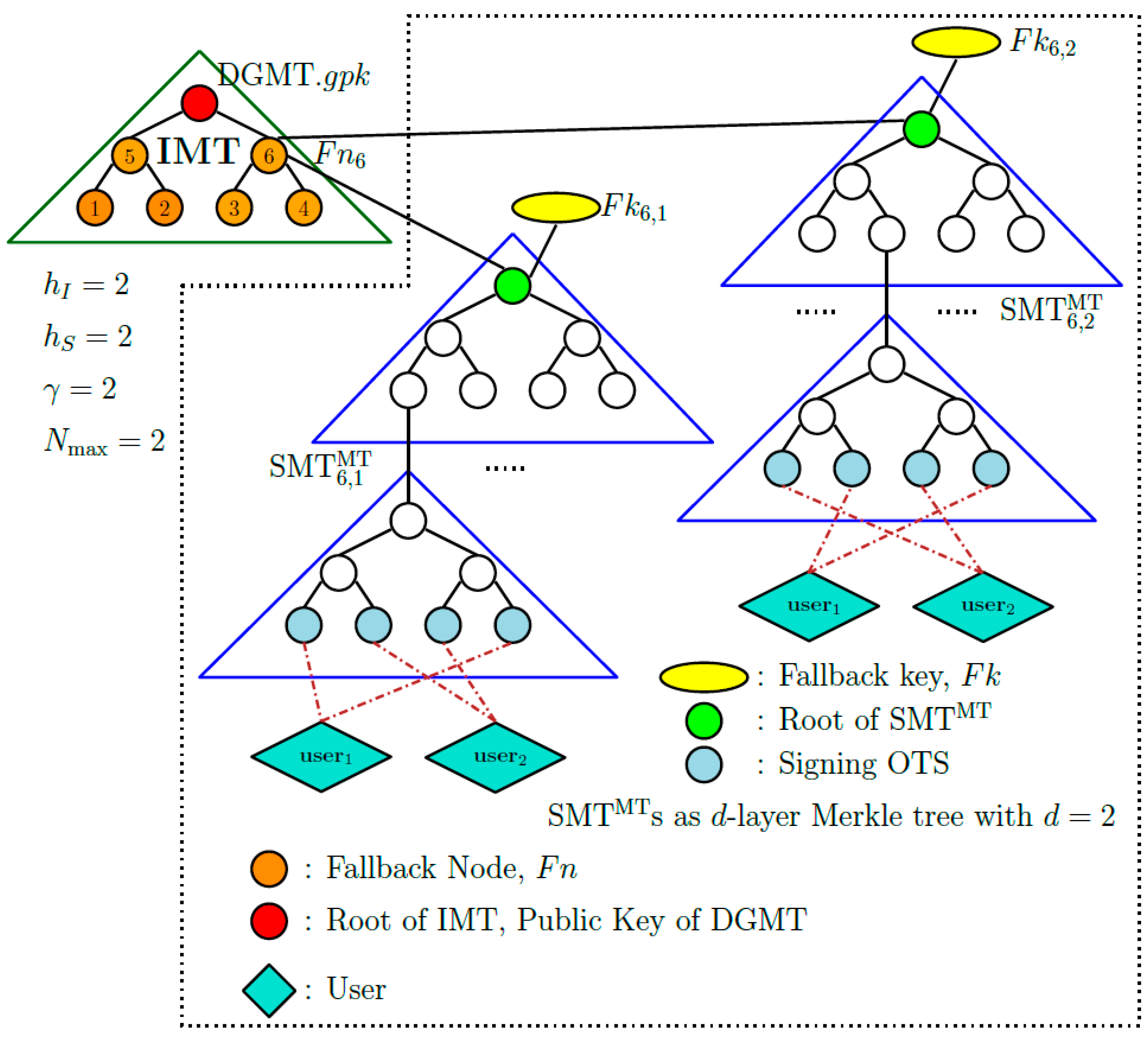

4.1. DGMT: An Overview

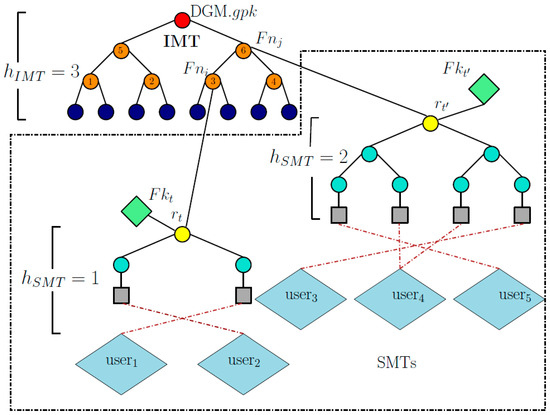

DGMT uses a hash function that is randomly selected from a collision-resistant hash function family , an EU-CMA one-time signature scheme , a PRF , and two SPRPs and .

Tree structure. DGMT uses the structure, which is similar to the structure of DGM, with two key modifications outlined below. First, similar to DGM, the IMT is a Merkle tree generated over a set of randomly chosen leaf nodes and its root forms the group public key, denoted by . However, in DGMT all nodes of IMT, except the root node, are used as fallback nodes. Second, unlike DGM which uses s with variable heights, DGMT employs s with the same height, where each is a two-layer Merkle tree, and both layers have the same height . The root node of an is connected to a fallback node using a fallback key. A fallback node is used to attach number of s, each using a distinct fallback key, to the IMT. We use the numbering of IMT nodes and the multiplicity number of s that are attached to an IMT node to give a unique sequential index to each . Thus the j-th that is connected to the i-fallback node will be labeled and will be associated with the fallback key . The structure is explained in Algorithm 1 and illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

structure of DGMT. The red node represents the group public key , the orange nodes represent the fallback nodes , the yellow nodes and represent two of the fallback keys, the green nodes are the root of the s and play the role of the keys, say , where is the root of the and is the key.

The top and bottom layers of the two-layer are denoted by and , respectively. In particular, the of the is denoted by and the of the linked to the k-th leaf node (from left) of is denoted by . From now on, we let be the index of the k-th leaf node of , and be the index of the l-th leaf node of .

The manager uses the PRF and a secret key to generate OTS key pairs , for , and construct the as an MSS, as described in Section 2.3. Also, the manager uses the PRF and a secret key to generate the OTS key pairs , for , and construct for all . However, for s the manager first permutes the set using the SPRP (See Algorithm 2). Let the index be the permuted position of the index . After permutation, the leaf node at index , for , is computed as , where and is the manager’s master secret key of the SPRP . Finally, is constructed as an MSS using these permuted leaf nodes. See Algorithm 3.

Setup phase. During the setup phase, the manager performs the following steps: (i) Generates the group secret keys using the Algorithm 4 (ii) Constructs the IMT to compute the group public key , (iii) Constructs all , for all valid i and j, and uses the root of each , denoted by , to compute its corresponding fallback key , linking to the internal node of IMT, and (iv) Publishes the group public parameter , where is the list of all fallback keys and is the revocation list, initially empty. There are fallback keys for each IMT internal node, and is stored as the -th element in the list . See Section 4.2 specifically Algorithm 1.

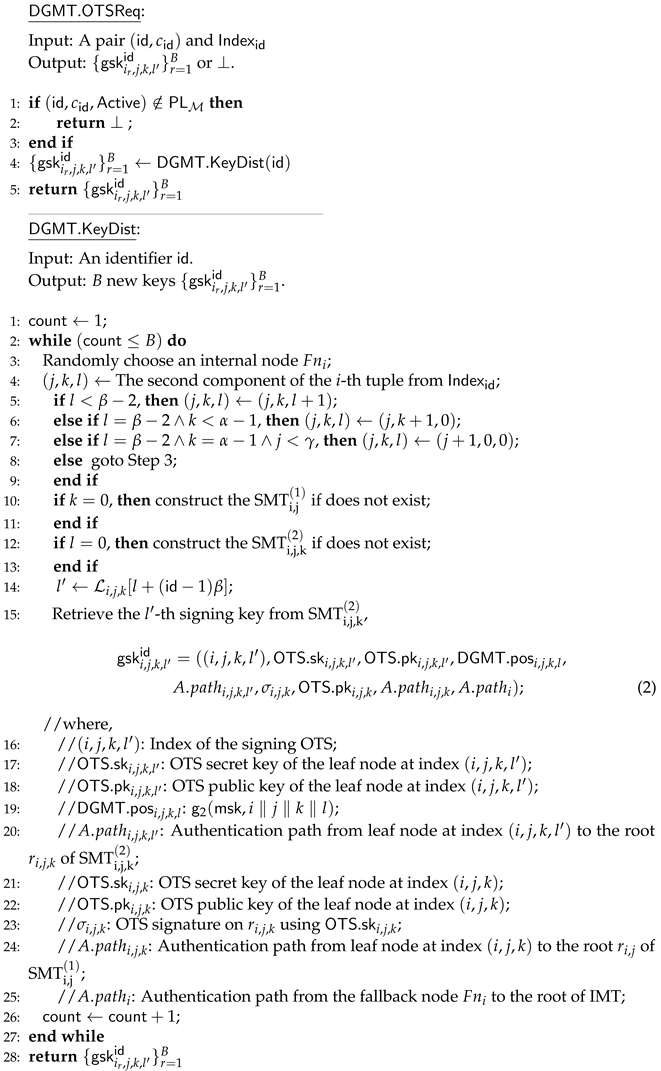

Join and Request OTS key pairs. In DGMT, a user first joins the group and receives using the Algorithm 5. When the user with identifier needs OTS key pairs, they send as a request for new keys to the manager. Upon receiving this request, if is valid and the user has not been revoked (i.e., ), the manager randomly selects B fallback nodes and allocates the first available OTS key pair from the corresponding s. If no available OTS keys remain in a selected , the manager deterministically generates a new , ensuring the fallback keys match those computed during the setup phase. This request can be repeated when all OTS keys are exhausted to receive new keys. This process is similar to the approach used in DGM. See Section 4.2 and Algorithm 6.

Signing. The format of the DGMT signature on a message m, generated using the OTS key pair at index , is as follows:

is the only part of that is computed by signer, while the remainder is provided by the manager during the OTS key pair request phase. Each signature has a unique and secret value that is used for both tracing and revoking signatures. The authentication path from the leaf node indexed by to consists of three parts: (i) the authentication path from the leaf node at index to the root , denoted by , (ii) the authentication path from the leaf node at index to the root , denoted by , and (iii) the authentication path from to . Moreover, is the signature on by the OTS key pair . See Algorithm 7.

Revoking a user. DGMT employs the SPRP to compute and add all assigned s of a misbehaving user to the revocation list . In DGMT, each user is assigned a unique interval, allowing the manager to run this process efficiently without the need to store all users’ s in advance, computing them only when necessary. In contrast, in DGM, the manager uses a symmetric puncturable encryption scheme to puncture all of a misbehaved user. Our revocation list-based method requires significantly less storage and computation compared to -based revocation of DGM. See Section 6 for a detailed analysis.

Verification. Verifying a signature on a message m involves the following four steps: (i) Ensure that , (ii) Verify and using the public keys and , (iii) Compute , where is the -th element of the list , and (iv) Verify that the computed group public key from , the authentication path, and equals to . For details on the verification algorithm and user revocation, see Algorithm 8 and Algorithm 9, respectively. Unlike DGM, DGMT’s verification is non-interactive, and the fallback key is not included in the signature.

Opening. DGMT opens the signature by computing . Indeed, the method of distributing leaf nodes among users and including as part of the signature allows the manager to trace each signature using the secret key . See Algorithm 10 for details. In contrast, in DGM, the manager must store in a list and search through the list to open each signature, a process that becomes prohibitively expensive for large .

4.2. Constructing DGMT Tree

In this section, we provide a detailed explanation of the DGMT tree framework and discuss how its design effectively removes the limitations of DGM.

4.2.1. Setup Parameters

DGMT is designed to support signatures and users. Based on these values, DGMT selects three parameters , , and and defines its setup parameters as

where , , and represent the height of the IMT, the height of the s, and the number of s attached to each fallback node, respectively. These parameters provide flexibility to the system, allowing it to efficiently generate at least OTS key pairs and accommodate users. DGMT also uses two public lists: (i) A list of the fallback keys, and (ii) A revocation list of revoked signatures. The following relations hold in the structure of DGMT.

- 1.

- Each is a two-layer Merkle tree with layers of equal height , so .

- 2.

- Given the parameters , , and in DGMT, the total number of OTS key pairs is .

- 3.

- The number of fallback keys in DGMT for the given setup parameters is .

- 4.

- Each user must receive at least two keys from each , for every , thus must satisfy , where (See the Anonymity proof in Section 5).

- 5.

- For each tuple and , we have , where .

Based on the second and third relations mentioned above, for a given the number of fallback keys is . Therefore, if the manager selects so that is sufficiently small, the manager can effectively generate and publish all the fallback keys at the setup phase. This allows the verifier to check the validity of the fallback keys without interacting with the manager, making DGMT a non-interactive group signature scheme and addressing the first shortcoming of DGM.

Remark 2.

For a given , the parameters and γ are chosen such that , ensuring is sufficiently small. This creates a trade-off between γ and : a smaller γ results in a larger IMT. Since IMT nodes are stored in memory, a larger increases memory costs. Therefore, γ must be large enough to have a reasonable . The terms “sufficiently small” and “large enough” depend on the available system and communication cost.

4.2.2. Tree Construction and Allocation of Intervals to Users

Constructing the DGMT tree is a two-step process.

- 1.

- In the setup phase, the manager constructs the IMT along with all s, for every i and j, to compute and publish andwhere is the root of and is the i-th fallback node. See Algorihtm 1.

- 2.

- During the join phase when a user requests keys (or during the sign phase when a user requests new OTS key pairs) and no available key pairs remain in some current s for this user, the manager must construct new s. The manager then randomly selects new OTS key pairs from these newly constructed trees and assigns them to the user.

To explain the different steps of constructing DGMT’s tree, we assume the manager has generated the secret key , where each of them is a -bit random strings (See Algorithm 4 for details). Also, let be the setup parameters. Thus, the number of leaf nodes in s and s is and .

| Algorithm 1 |

|

- 1.

- Constructing the IMT and s and publishing : The manager runs this process to publish . This process is detailed in Algorithm 1, where the is computed in lines 3–7 and is computed in lines 9–19. The fallback key for is , where serves as the key for (line 16). is a public list, and its -th element is , where and . Also, is initially empty and will be updated by the Algorithm 9 whenever the manager revokes a misbehaving user.

- 2.

- Constructing s and allocating their leaf nodes to users: The manager constructs s when they want to randomly allocate the leaf nodes to users. Each user is assigned a unique intervalfor the following purposes:

- (a)

- Efficient Random Allocation. The manager shuffles the leaf nodes of using Algorithm 2, which takes an index and , and outputs the shuffled index list of leaves of asFor each , sublist represents the leaf nodes of allocated to user , which the manager uses to assign the corresponding OTS key pairs to user .

- (b)

- Efficient Opening and Revocation. Each signature contains a unique . To open a signature, the manager computes and identifies the identifier as the signer if (or equivalently announce as the signer). This approach results in an efficient signature opening algorithm. Additionally, by using these intervals, the manager only needs to compute and add some specific s to the revocation list , ensuring efficient signature revocation. See Algorithms 9 and 10.

Remark 3.

As discussed in Section 3.2, DGM’s second limitation is its inefficient management of storage, which scales linearly with . Indeed, this inefficiency arises from its simple random allocation of leaf nodes, requiring the manager to store all values, for each t and l, to enable signature opening and revocation. This approach demands an impractical amount of storage, requiring approximately Terabytes to support OTSs [26]. In contrast, our proposed interval-based method overcomes this limitation and reduces storage requirements to scale with the number of intervals (or equivalently ), rather than .

| Algorithm 2 |

|

- To construct , the manager first computes . The l-th element in this list indicates the position of the leaf node after permuting the leaf nodes. Then, the manager computes the OTS key pairs and for all . The -th leaf node of is After computing all the leaf nodes of this tree, the manager constructs and signs its root, , by to attach to . See Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3 |

|

4.3. DGMT’s Algorithms

In Section 3, we presented the algorithms of a . Here, we describe all the algorithms of DGMT in detail, as a .

- 1.

- : The manager runs the Algorithm 4 on the security parameter and the setup parameters to obtain , where , and . These values are generated as follows:

- is the manager’s master secret key of the SPRP that is used for opening signatures, revoking users, and generating s.

- is the secret key of the PRF for generating an of height , where its root, i.e., , is the group public key .

- is the secret key of the PRF for generating the s on the OTS key pairs , with , and .

- is the secret key of the PRF for generating the s on the OTS key pairs s, with , and .

- is the secret key of the SPRP for shuffling the leaf nodes of s.

- is the revocation list that is initially empty.

| Algorithm 4 |

|

- 2.

- This interactive joining protocol, the same as in Section 3.1, occurs between the manager and a prospective user with identity over a secure channel. If and , the manager allocates the smallest unassigned identifier with along with a secret value to this user and sends to the user. Otherwise, the algorithm outputs ⊥. The manager stores in the private list and the user’s identity as the -th element in the list , where is the list of the users’ identities who have already joined the group and is initially empty. See Algorithm 5 for details.

Algorithm 5 - Input: The identity of a user

- Output:

- 1:

- The user sends along with a request to join the group;

- 2:

- If or , then outputs ⊥; End if;

- 3:

- The manager takes the next available unassigned ;

- 4:

- generates ;

- 5:

- sends to ;

- 6:

- stores the received ;

- 7:

- appends to the list ;

- 8:

- appends to the -th position in the list .

When a user with identifier requires new OTS key pairs, they initiate Subroutine Algorithm 6 by sending a request to the manager via the Algorithm . Upon receiving the request, the manager allocates B new private keys to the user by executing the Algorithm , provided that , i.e., the user has already joined the group and has not been revoked. To execute the key allocation effectively, the manager assigns each user with identifier a list:This list corresponds to the internal nodes of the IMT, where the second component of the i-th entry, i.e., , represents the last signing key assigned to the user from the linked to the internal node . In other words, the entry indicates that user has received their l-th signing key from . Initially, this list is set as , and is updated after each allocation. Algorithm explains the process of selecting the next B available indexes for the user and updating accordingly.

Remark 4.

In lines 5–9 of Algorithm , we maintain the bound to ensure that every user has at least one unused key in each , as required by the anonymity proof.

| Algorithm 6 Subroutines of Key Distribution of |

|

- 3.

- The signing algorithm takes as input a message m and an unused private key that belongs to the user and outputs a signature as explained in Algorithm 7.

Remark 5.

In Algorithm 7, the depth μ of the internal node in the IMT is used. The use of fixed-height s results in variable-length signatures, and including μ as part of the signed message helps prevent potential exploitation of this variability in signature length.

| Algorithm 7 |

|

- 4.

- To verify a pair , the verifier runs the deterministic Algorithm 8, which outputs 1 if and only if is a valid signature on m.

Remark 6.

In DGMT, having allows the verifier to uniquely determine the fallback key from the public list . Therefore, unlike DGM where is a part of the signature, in DGMT is not a part of the signature.

| Algorithm 8 |

|

- 5.

- To revoke a set of users, the manager runs Algorithm 9 to update both and . In particular, this algorithm changes the status of each in , preventing them from requesting any further keys. See Algorithm 9. For two given indexes and , we have if , or , or .

| Algorithm 9 |

|

- 6.

- The manager runs the deterministic Algorithm 10 to open the signature . This algorithm outputs either the identifier of the user who generated , or ⊥ if the signature cannot be attributed to any specific user. As we already mentioned, the manager can retrieve the identity of the user by looking up the -th entry in the list .

| Algorithm 10 |

|

4.4. Instantiating DGMT and Parameter Estimation

To compute the signature and public key size of DGMT, we use WOTS as the OTS. As argued in Remark 1, using WOTS allows us to omit and from the DGMT signature and it will be as:

Now we compute the signature and public key sizes of DGMT in terms of the setup parameters of the system, security parameter and Winternitz parameter w.

- Signature size:

- is the index of the leaf node and is bits.

- and are WOTS signature, each of size bits, where is the number of elements in WOTS signature.

- is the output of the SPRP and is bits.

- and are the authentication paths in the , , and IMT, which is totally bits.

Thus, the signature size in bits, is bounded by

Public key size: The public key of DGMT is the root of the IMT, and is bits.

Parameter selection in our implementation: We consider a GSS with OTSs and users, and choose the setup parameters . The configuration allows each user to receive up to OTSs from the manager (This configuration provides exactly OTSs, and since is bounded to , the system can accommodate users.). The number of fallback keys is which can be generated comfortably during initialization.

Let the security parameter and . Given these parameters, Table 6 provides the signature size and public key size of DGMT. Theorem 1 shows that the security of DGMT relies on the security of SPRPs and the collision resistance of the underlying hash family. Thus classic and quantum security when is the output size of the hash function, are respectively bits and qbits. Therefore, for its classic security is respectively 128 and 192 bits, and its quantum security is respectively 85 and 128 qbits [30,51].

Table 6.

Signature and public key sizes of DGMT for the given parameters.

Remark 7.

Security DGMT relies on the collision resistance of the hash function that is used to construct the Merkle trees (IMT and ). Using the approach in [52] one can modify the trees so that the security of the resulting signature relies on the second pre-image resistance. This will allow the output size of the hash function to be halved for the same security level (the complexity of the best collision and pre-image attacks for a hash function with output size λ is and , respectively), resulting in a shorter signature. This however requires careful analysis of the design because of multi-target attack that is applicable to the new design.

Multi-target attack was introduced in [32] in which the adversary makes d hash queries and succeeds if a second preimage for any of the queried values is found. It was shown that for a hash function with λ-bit output allowing d queries reduces the attack complexity from to and so for λ-bit security either the hash function output size must be increased, or different keyed hash functions for each call must be used [32]. Adapting DGMT design to reduce security to second pre-image resistance will be our future work.

5. Security Proofs

In this section, we prove that DGMT provides Correctness, Unforgeability, Anonymity, and Traceability.

Theorem 1.

Let be the scheme described in Section 4. If (i) is a randomly selected hash function from the collision-resistant hash function family , (ii) is an EU-CMA One-time Signature scheme, (iii) is a PRF, and (iv) and are two SPRPs, such that for any randomly selected tuple with the probability of finding a key with is negligible, then satisfies Correctness, Unforgeability, Anonymity, and Traceability.

Proof.

We follow the adversarial game model of [20,50] to establish that DGMT satisfies Correctness, Unforgeability, Anonymity, and Traceability. Below we provide sketches of the proofs for each case.

Correctness: To prove correctness of DGMT, we show that if an adversary corrupt all but one user, the honest user can successfully enroll and create signatures that are accepted by the verification algorithm and will be traced back to the user.

In the correctness game , a PPT adversary can use oracles , and to add honest users and revoke the users, and to corrupt all but one user. In presence of such adversary, the honest user can still establish a secure channel to the (honest) group manager and securely receive . Only this user and the group manager know and the user uses to receive from the manager through a secure channel and generates the correct signatures.

These keys are specifically allocated to this honest user, ensuring that for all , we have , where represents the index of the leaf node after permutation by the SPRP (See Algorithm 2). Let and be as

By computing

the manager finds , i.e., , so

ensuring that computing yields the identifier of the signer ( is the ceiling function).

Unforgeability: To prove the unforgeability property of DGMT, we show that if an adversary can forge a signature, then it creates a contradiction to the assumptions of the theorem.

In the unforgeability security game , a challenger first runs the to create the trees and the secret and public keys of the system. Then the challenger gives access to the oracles , , , and to a PPT adversary . Therefore, is allowed to obtain the signatures of every honest user on arbitrary messages. Each message-signature pair is stored in the signing list , preventing from using these signatures as forgeries for their corresponding messages. can revoke users, so their signatures will not be verified. Additionally, can corrupt users to obtain their and sign messages on their behalf, however, the generated signatures cannot be used as forgeries as those users are not honest.

We show that if succeeds in forging a signature, i.e., it outputs a valid signature

on a message m at the end of the query phase such that , where

and , then we can construct another PPT adversary that simulates the role of the challenger for to find a collision for the hash function , or forge a valid signature for , or can find a second-key for that maps to for some . Note that in each case, one of the assumptions of the theorem will cause a contradiction.

Let be a forged signature on message m. Since is a valid signature then the index of the must be a valid index, i.e., , , and . Let the index belong to a user with identifier . As simulates the role of the challenger, it knows

and computes where

- 1.

- Let . However and are both valid signatures for the index . This implies that both paths lead to the same group public-key . Therefore, found a collision for that contradicts the fact that is a collision-resistant hash function.

- 2.

- Assume that . Suppose that leads to root node and leads to root node . In both cases, the -th element of , which is , will be used to verify the signatures. Then we have and . Now we have three cases:(i) Let . Then found a collision for because and both of them leads to .(ii) If and . In this case, simulator found two keys such that and which is a contradiction with the assumptions.(iii) If and which is discussed in the next case.

- 3.

- If . We have two cases:(i) If . Since , found a collision for and it forms a contradiction to the assumptions.(ii) Next we discuss the case when .

- 4.

- If and . There are three possible cases.(i) If , found a collision for , that is a contradiction to the assumptions.(ii) Let . Since and , found a collision for the hash function , that is a contradiction.(iii) Let and both the authentication path and leads to two different root nodes and respectively. If , then we are in case 2(i). If , we are in the situation of case 2(ii).

- 5.

- If and . There are two cases:(i) If . This implies that found a forgery for the that contradicts the fact the is EU-CMA secure.(ii) If , which is discussed in the next case.

- 6.

- If , . Assume that leads to a root node and leads to a root node . We can divide this case into three subcases.(i) If , then found a forgery of that contradicts to that the is EU-CMA secure.(ii) Let and . Then two different authentication paths of the same length lead to the same root node . Therefore, found a collision for the hash function and hence a contradiction.(iii) If and , which is discussed in the next case.

- 7.

- If , , there are two cases.(i) Let . If , found a collision for that is a contradiction.(ii) If , sinceand , found a collision for that is a contradiction.

- 8.

- Lastly, we assume that all the components of and are the same except the components and , that is . Then found a forgery on message m for the for , i.e., both and are valid, that contradicts the EU-CMA security of the .

Therefore, we can conclude that DGMT achieves unforgebility.

Traceability: In traceability game , the challenger runs the to create the tree and generate the secret and public keys of the system. The PPT adversary has access to oracles , , , and oracles and can add and revoke users, corrupt them and obtain their , and obtain all signatures of honest users. At the end of the query phase, the adversary has to output a valid signature

on a message m with . We will use this adversary to construct another PPT adversary that simulates the role of the challenger for to find a collision for the hash function , or forge a valid signature for , or can find a second-key for that maps to for some . Note that in each case, one of the assumptions of the theorem will cause a contradiction.

Let be a valid signature on m, with . The is a valid index, so it belongs to a user with identifier and the manager knows its corresponding given in (7) and is able to compute where

The proof arguments are the same as the proof presented for Unforgeability. The only difference is that in the traceability proof because and . Therefore, we also have

- 1.

- If , then we found a collision for . If not, then we have the next cases.

- 2.

- Let , and and leads to root nodes and respectively. If , then found a collision for . Otherwise, this leads to the next case.

- 3.

- Let . If , then we found a forgery for the scheme. However, if then there are two cases:(i) If , thus found a collision for .(ii) If , we have the next case.

- 4.

- Let , and and leads to root nodes and respectively. If , then found a collision for . Next, we consider the case .

- 5.

- Let . Assume that and . If , then the adversary can find a new key such that . Otherwise, that is if , then can find a collision for using the authentication paths and because both the paths lead to the group public key .

Hence, we can conclude that DGMT achieves traceability.

Anonymity: We show that if succeeds with a non-negligible advantage in distinguishing a signature generated by randomly selecting one of the two honest users with identifiers and , then we can distinguish the outputs of the SPRP or from random permutations with non-negligible probability, which is a contradiction with our assumptions.

In the anonymity security game , a PPT adversary has access to the oracles , , , , , and . The adversary is allowed to add honest users to the group and to revoke users from the group. It also can corrupt honest users to obtain their s and sign messages on their behalf. Additionally, can use the oracle to obtain signatures from honest users on arbitrary messages. Furthermore, can use the oracle to find the identity of the signer for any message-signature pair.

At some stage of the game, calls . selects a message m along with two users with identifiers and and send them to the challenger. The challenger checks if and are honest or not. If they are honest, the challenger selects randomly a , say , and a random bit b. According to Algorithm in Algorithm 6, every user has at least one unused key in every . So, the manager can select two unused keys of the users with identifiers and in . Let and be the indexes of the leaf nodes of these unused keys which belong to the users and , respectively (i.e., these two unused keys are and ). The challenger generates , where is

with and sends it back to the adversary to determine whose signature it is. has still access with oracles , , , , and . However, cannot call the oracle on the signatures generated by , which are stored in the challenge list . Also, cannot invoke the oracle on users with identifiers or , as this would allow to distinguish the signer by searching in the revocation list before and after calling the oracle on one of these identifiers. Finally, outputs a bit and wins the anonymity experiment if .

Notice that and are the only elements of the signature that allows to distinguish the signer. We discuss both cases separately below.

- 1.

- breaks the anonymity with non-negligible probability using :With the provided oracles, the adversary can request signatures on arbitrary messages using all the leaf nodes of the selected , except for the leaf nodes indexed by and . Let and represent the tuples assigned to the leaf nodes indexed by and before permutation. According to the security model, knows the values of , for all . Consequently, knows the permutation of (at most) all the leaf nodes of except two leaf nodes indexed by and , and does not have any information on the values of and . If breaks the anonymity experiment by with non-negligible probability, it means that is able to extract information on the two values and , and identify which one would be located at the position with non-negligible probability. This would mean that can distinguish the outputs of the SPRP from a random function with non-negligible probability, which is a contradiction.

- 2.

- breaks the anonymity with non-negligible probability using :Using the notation of the previous case, is either or . Hence, if the adversary breaks the anonymity experiment using with non-negligible probability, it means that is able to win the indistinguishability game of the SPRP for two pairs and with non-negligible probability, which is a contradiction.

It is important to note that although and are both related to the index , they are generated using different SPRPs and keys. The former represents the location of after the permutation of the leaf nodes, determined by the SPRP and the secret key through the shuffling Algorithm 2. The latter is computed using the SPRP and the key . As a result, these values together do not reveal any information about the index and equivalently the identifier of the signer. □

6. Revocation in DGM and DGMT

One of the main contributions of DGM is the introduction of a new approach to revocation that uses as its main building block. In the following, we review this approach and show that there is a significant hidden cost in using the approach, which makes the traditional revocation list a much better choice in practice for revocation. Moreover, in Appendix A, we describe how decryption keys can be used to construct a revocation list, providing a more efficient approach to revocation than the original DGM. See Table A1 for the comparative study.

6.1. Revocation in DGM

DGM uses SPE-based approach to revocation. A DGM signature includes a unique tag that is the encryption of the index of the leaf node (called ) whose associated OTS has been used to sign the message. The verifier checks if the OTS key is revoked or not by checking whether it is getting back the message of the signature by first encrypting it using the master secret key and then decrypting the encrypted message using the punctured decryption key while using as the tag. If the OTS key is revoked, the decryption key is punctured at the tag .

In the following, we use the description and parameters of that was introduced in Section 2.1 to explain the revocation algorithm of DGM. Assume that there are punctured leaves in IMT/SMT structure at a certain point of time in DGM. If the manager wants to revoke a user to whom signature positions are assigned, then the manager invokes the algorithm with and receives the key . Next, the manager punctures the at all the previous positions and new positions by calling the algorithm d times, and gets the punctured decryption key . The manager replaces the old keys with the new key pair and publishes them. Here is the new encryption key of the , and is the new decryption key. The verifier checks whether a signature is revoked by checking,

where is the encrypted index of the leaf node associated with the signature and m is the received message. The tag space is the set of all possible leaf indices. If the is punctured at the position t, then the key of derived from is different from the key of derived from and thus comparison (9) will fail. For checking if a signature is revoked, the verifier performs two computational steps: and .

1. Encryption step . Verifier first computes a chain of d keys: from . Then verifier applies the pseudorandom function on each of the for along the tag t as described in Equation (9). DGM uses the construction of Pun-PRF in [48] and realizes SPE by constructing using GGM construction [53].

GGM-based construction of . Let G be a length doubling pseudorandom generator defined as . Let us denote the least significant bits and most significant bits of by and respectively. Let tag t be a -bit long binary-string . We compute as

We can view all executions of G as a binary tree of height where and are the right and left child, respectively, of the parent node and the tree is called GGM tree. Now the t-th leaf node of the GGM tree with root is the . Therefore, each computation needs evaluations of G and, as a consequence, the verifier has to evaluate G times to compute the encryption key of , excluding the Xors and computation of hash functions.

2. Decryption step . During the computation of the decryption key with d punctured tags, the verifier needs to evaluate d times and once on the key and the tag t. Let which is punctured at tags . Each is the list of sibling nodes of the path that leads to the -th leaf node of the GGM tree with the root and the j-th sibling node is

where be a -bit binary string and is bit-wise complement of . Therefore, each puncture or revocation needs evaluations of G and each puncture needs -bit storage. Notice that, given , we can compute any leaf node of the GGM tree with root except the leaf node at position , that is we can compute as long as . Evaluation of needs the sibling node in which is the root of the GGM subtree containing the t-th leaf node. Then, needs at most and minimum 0 evaluations of G, that is, on average evaluations of G is required. Therefore, the verifier has to perform on average evaluations of G to compute the decryption key of of .

Total computation cost of revocation includes computation of encryption key, evaluation of , computation of decryption key, evaluation of , and string comparison which in total will be, evaluations of G, one evaluation of and , and a string comparison on average.

6.2. Revocation in DGMT

In DGMT, for each revoked signature the manager appends of the revoked signature to the revocation list , and so after revoking d signatures, the revocation list will require bits of storage. For verification of a signature when d signatures are revoked, the verifier needs to, at the most, traverse a list of d elements with a string comparison at each element.

In comparison, for each revocation in DGM, the manager appends strings of length bits to the list , and so when d signatures are revoked, DGM requires bits of storage. For verification of a signature, the verifier requires evaluations of G, one evaluation of and , and a string comparison.

Thus for both computation and storage, the DGMT revocation list approach outperforms the DGM SPE-based approach.

7. Implementation and Experiments

In this section, we present our implementation and experimental results. Our implementation is for all the algorithms in Section 4. The implementation provides all the functions required in a fully dynamic symmetric-key based group signature. The code is available at https://github.com/submissionOfCode/DGMT_ref, accessed on 19 November 2024.

In our experiment, we use a system with OS Ubuntu 18.04, and the code is compiled using GCC-8.4.0. The processor of the system is Intel®CoreTMi7-9700 8-Core CPU @ 3.00 GHZ and it has 8 GB RAM. We use XMSS reference code, given in https://github.com/XMSS/xmss-reference, accessed on 16 March 2021, as the base of our software to comply with the fact the XMSS is a standard [16]. We use the AES functions in OpenSSL as a SPRP. We only use a single core without hyper-threading and turbo-boost. All the experimental results are listed in Table 7 and each reported timing is the average of 5 runs. Our experimental results show that DGMT is practical for large values of .

Table 7.

Timings for different Group Signature Operations, and Sizes of Signatures, IMT and different files in all the directories for different group parameters for . We use SHA-256 as the hash function and the Winternitz parameter w is 4. The column with is used for comparison for DGM. (s, ms, B, KB, and MB stand for seconds, Milliseconds, Bytes, Kilobytes, and Megabytes respectively).