Civil Integrated Management (CIM) for Advanced Level Applications to Transportation Infrastructure: A State-of-the-Art Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

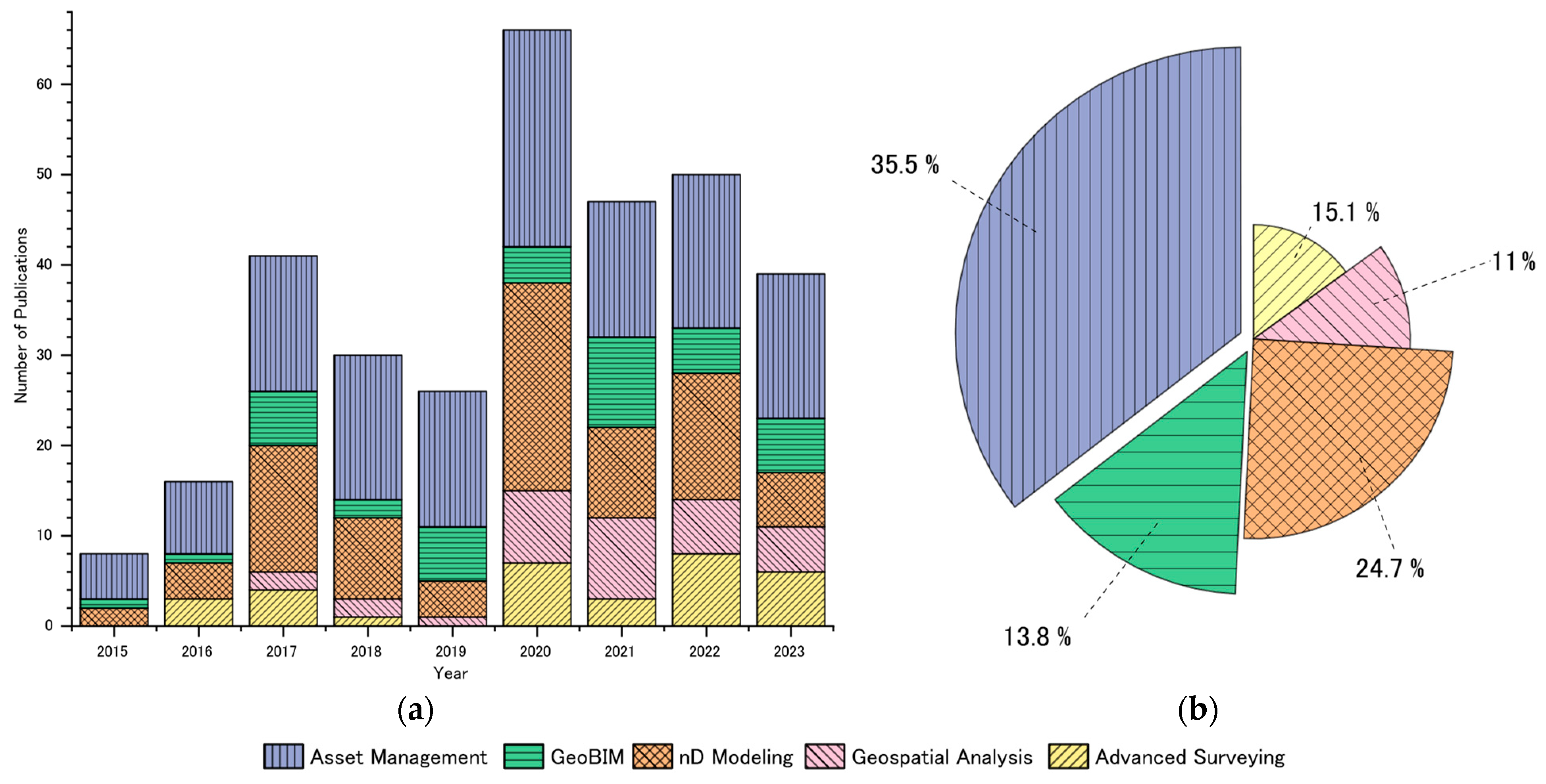

2. Methodology

- (i)

- Application of advanced surveying methods to produce digital geospatial data (Advanced Surveying);

- (ii)

- Geospatial analysis tools for project planning (Geospatial Analysis);

- (iii)

- Multidimensional virtual design models (nD Modeling);

- (iv)

- Integrated Geospatial and Building Information Modeling (GeoBIM);

- (v)

- Transportation infrastructure maintenance and rehabilitation planning (Asset Management).

3. Application of Advanced Surveying Methods (Advanced Surveying)

| Tools | Benefits | Limitation | Resolution | Data Format | Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic Information System (GIS) | Multisource data analysis, comprehensive data management, spatial analysis, and modeling capabilities | Requires specialized training, steep learning curve, limited 3D visualization | Dependent on the source | Vector, Raster | Traffic management, road network planning, public transport planning, urban planning, environmental planning | [100,101,102,103] |

| Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) | High accuracy, detailed 3D data, rapid large-area data capture, change detection, and monitoring capabilities | High costs, time-consuming data processing, data capture specific to a point in time | 50–300 mm | Point Cloud, DEM, Raster | Transportation infrastructure design and inspection, flood risk assessment, topographic mapping, utility mapping | [19,68,104,105] |

| Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) | High-resolution data capture, rapid large-area coverage, cost-effective data collection | Weather-dependent, limited flight time, requires specialized training | Depends on the mounted sensor: 10–100 mm | Point Cloud, DEM, Raster | Bridge inspection, road condition assessment, pipeline monitoring, construction progress monitoring | [104,106,107,108,109] |

| 3D Scanning | Highly accurate data capture, capable of capturing complex geometries, rapid data collection | Time-consuming data processing, data capture specific to a point in time | 0.1–10 mm | Point Cloud, Mesh, CAD, BIM | Construction site monitoring, as-built modeling, asset management | [110,111,112] |

| Remote Sensing | Rapid large-area data capture, change detection and monitoring, high-resolution imagery | Data capture specific to a point in time, weather, and atmospheric conditions dependent | 0.3–100 m | Raster | Land cover mapping, disaster response, flood modeling, environmental monitoring | [100,113,114] |

| Mobile Mapping System (MMS) | Rapid large-area data capture, high accuracy, and precision, change detection, and monitoring capabilities | High costs, time-consuming data processing, limited to road and highway data capture | 50–300 mm | Point Cloud, DEM, Raster | Pavement assessment and management, mapping, and modeling for decision-making | [33,115,116,117,118] |

| Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) | Subsurface structure and utility data capture, non-destructive data collection, 3D subsurface visualization | Limited depth range, soil condition-dependent, time-consuming data processing | 10–100 mm | Point Cloud, BIM, CAD | Utility detection, underground structure mapping, pavement layer condition assessment, structural defect detection | [119,120,121] |

4. Geospatial Analysis Tools for Project Planning (Geospatial Analysis)

5. Multidimensional Virtual Design Models (nD Modeling)

6. Integrated Geospatial and Building Information Modeling (GeoBIM)

7. Transportation Infrastructure Maintenance and Rehabilitation Planning (Asset Management)

8. Further Discussion

9. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scott, R.; Deasy, K.; Longstreet, M. VTRANS Hybrid Research and Innovation Symposium: Civil Integrated Management (CIM/BIM), Agency of Transportation (VTrans). 2022. Available online: https://vtrans.vermont.gov/planning/research/projects/CIM (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Scott, R.; Deasy, K.; Longstreet, M. Digital Twins: The Future of VTRANS through 3D Modeling, Vermont Agency of Transportation. 2022. Available online: https://vtrans.vermont.gov/ (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Berglund, E.Z.; Monroe, J.G.; Ahmed, I.; Noghabaei, M.; Do, J.; Pesantez, J.E.; Fasaee, M.A.K.; Bardaka, E.; Han, K.; Proestos, G.T.; et al. Smart Infrastructure: A Vision for the Role of the Civil Engineering Profession in Smart Cities. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2020, 26, 03120001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, J.; Cawley, B.; Petros, K.; Brautigam, D.; Burns, R.; Burns, S.; Kliewer, J.; Lobbestael, J.; Park, R.R.; Jahren, C.T. Advances in Civil Integrated Management; National Cooperative Highway Research Program, No. NCHRP Project 20-68A; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Trboyevich, C.; Lovel, R.; Sohn, C. Life-Cycle Civil Integrated Management (CIM) Advancements in Preliminary Design BIM for Infrastructure. 2019. Available online: https://trid.trb.org/View/1650202 (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Costin, A.; Adibfar, A.; Hu, H.; Chen, S.S. Building Information Modeling (BIM) for transportation infrastructure—Literature review, applications, challenges, and recommendations. Autom. Constr. 2018, 94, 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Jahren, C.T.; Hao, J.; Zhang, C. Implementation of CIM-related technologies within transportation projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2020, 20, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F. Civil Integrated Management, and the Implementation of CIM-Related Technologies in the Transportation Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, A.; Li, H.; Lark, R.; Dunn, S. BIM for infrastructure: An overall review and constructor perspective. Autom. Constr. 2016, 71, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Jahren, C.T.; Turkan, Y.; Jeong, H.D. Civil Integrated Management: An Emerging Paradigm for Civil Infrastructure Project Delivery and Management. J. Manag. Eng. 2017, 33, 04016044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Shi, W.; Choudhary, H.; Fu, H.; Guo, X. Big Data Analysis for Retrofit Projects in Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Smart Grid and Smart Cities, ICSGSC 2019, Berkeley, CA, USA, 25–28 June 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Liu, S.; Liao, L.; Zhang, L. A Digital Construction Framework Integrating Building Information Modeling and Reverse Engineering Technologies for Renovation Projects. Autom. Constr. 2019, 102, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.; Tamash, N. Building a Spatial Data Infrastructure for Crossrail; Crossrail Learning Legacy: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- AASHTO. Transportation Asset Management Guide (A Focus on Implementation). 2021. Available online: https://www.tamguide.com/guide/ (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- O’Brien, W.J.; Sankaran, B.; Leite, F.L.; Khwaja, N.; Palma, I.D.S.; Goodrum, P.; Molenaar, K.; Nevett, G.; Johnson, J. Civil Integrated Management (CIM) for Departments of Transportation, Volume 1: Guidebook; NCHRP, No. Project 10-96; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, W.J.; Sankaran, B.; Leite, F.L.; Khwaja, N.; Palma, I.D.S.; Goodrum, P.; Molenaar, K.; Nevett, G.; Johnson, J. Civil Integrated Management (CIM) for Departments of Transportation, Volume 2: Guidebook; NCHRP, No. Project 10-96; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, B.; O’brien, W.J. Impact of CIM Technologies and Agency Policies on Performance for Highway Infrastructure Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-K.; Hwang, D.; Park, D. Analysis of Maintenance Techniques for a Three-Dimensional Digital Twin-Based Railway Facility with Tunnels. Platforms 2023, 1, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Kim, D.; Lee, C.; Kang, J.; Kim, D. Efficiency Study of Combined UAS Photogrammetry and Terrestrial LiDAR in 3D Modeling for Maintenance and Management of Fill Dams. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Pan, Z.; Jiang, L.; Zhai, X. An ontology-based methodology to establish city information model of digital twin city by merging BIM, GIS and IoT. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 57, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bortoli, A.; Baouch, Y.; Masdan, M. BIM can help decarbonize the construction sector: Primary life cycle evidence from pavement management systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 391, 136056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabato, E.; D’Amico, F.; Tripodi, A.; Tiberi, P. BIM & Road safety—Applications of digitals models from in-built safety evaluations to asset management. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Rashidi, M.; Yu, Y.; Samali, B. Integration of TLS-derived Bridge Information Modeling (BrIM) with a Decision Support System (DSS) for digital twinning and asset management of bridge infrastructures. Comput. Ind. 2023, 147, 103881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tache, A.-V.; Popescu, O.-C.; Petrișor, A.-I. Conceptual Model for Integrating the Green-Blue Infrastructure in Planning Using Geospatial Tools: Case Study of Bucharest, Romania Metropolitan Area. Land 2023, 12, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chan, A.P.; Darko, A.; Chen, Z.; Li, D. Integrated applications of building information modeling and artificial intelligence techniques in the AEC/FM industry. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobrega, B.G.; Yun, G.; Taco, P.W.G. Perspectives of Integration BIM and GIS in Brazilian Transportation Infrastructure Under the Vision of the Agents Involved. ResearchGate 2022, 4, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Tang, F.; Ma, T.; Gu, L.; Tong, Z. Construction quality evaluation of asphalt pavement based on BIM and GIS. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosurgi, G.; Pellegrino, O.; Sollazzo, G. Pavement condition information modelling in an I-BIM environment. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2022, 23, 4803–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, J.C.; Song, C.; Yin, C. Vision-assisted BIM reconstruction from 3D LiDAR point clouds for MEP scenes. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhong, J.; Ma, T.; Huang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Y. Pavement Distress Detection Using Convolutional Neural Networks with Images Captured via UAV. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Yang, J.; Chen, L. Automated Semantic Segmentation of Bridge Point Cloud Based on Local Descriptor and Machine Learning. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Pradhan, R.; Dutta, S.; Cai, Y. BIM4D-Based Scheduling for Assembling and Lifting in Precast-Enabled Construction. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Easa, S.; Wong, Y.D.; El-Basyouny, K. Virtual Analysis of Urban Road Visibility Using Mobile Laser Scanning Data and Deep Learning. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río-Barral, P.; Soilán, M.; González-Collazo, S.M.; Arias, P. Pavement Crack Detection and Clustering via Region-Growing Algorithm from 3D MLS Point Clouds. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Tan, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, P. BIM/GIS integration for web GIS-based bridge management. Ann. GIS 2021, 27, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheikh, A.; Alzamili, H.H.; Al-Zayadi, S.K.; Alboo-Hassan, A.S. Integration of GIS and BIM in Urban Planning—A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1090, 012128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamraeva, V.; Savinov, E. Infra-BIM for Business Processes’ Management in Road Construction and Operation. Arch. Eng. 2021, 6, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajadurai, R.; Vilventhan, A. Integrating Road Information Modeling (RIM) and Geographic Information System (GIS) for Effective Utility Relocations in Infrastructure Projects. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2021, 29, 3647–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenney, C.; Leonarczyk, Z.; Ghorbanzadeh, M.; Jones, F.; Mardis, M. A GIS-Based Analysis for Transportation Accessibility, Disaster Preparedness, and Rural Libraries’ Roles in Community Resilience; Public Libraries: New Windsor, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Soilán, M.; Nóvoa, A.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, A.; Justo, A.; Riveiro, B. Fully Automated Methodology for the Delineation of Railway Lanes and the Generation of IFC Alignment Models Using 3D Point Cloud Data. Autom. Constr. 2021, 126, 103684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, V.K. Integrated Framework of BIM and GIS Applications to Support Building Lifecycle: A Move toward nD Modeling. J. Arch. Eng. 2021, 27, 05021009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soilán, M.; Justo, A.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, A.; Riveiro, B. 3D Point Cloud to BIM: Semi-Automated Framework to Define IFC Alignment Entities from MLS-Acquired LiDAR Data of Highway Roads. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcuri, N.; De Ruggiero, M.; Salvo, F.; Zinno, R. Automated Valuation Methods through the Cost Approach in a BIM and GIS Integration Framework for Smart City Appraisals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, J.; Roensdorf, C. Modular Approach to 3D Representation of Underground Infrastructure in the Model for Underground Data Definition and Integration (MUDDI). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 44, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrianesi, D.E.; Dimopoulou, E. An Integrated Bim-Gis Platform for Representing and Visualizing 3d Cadastral Data. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 6, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garramone, M.; Moretti, N.; Scaioni, M.; Ellul, C.; Cecconi, F.R.; Dejaco, M.C. BIM and GIS Integration for Infrastructure Asset Management: A Bibliometric Analysis, ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 6, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancardo, S.A.; Viscione, N.; Cerbone, A.; Dessì, E. BIM-Based Design for Road Infrastructure: A Critical Focus on Modeling Guardrails and Retaining Walls. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazzetti, L.; Previtali, M.; Scaioni, M. Roads Detection and Parametrization in Integrated BIM-GIS Using LiDAR. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noardo, F.; Ellul, C.; Harrie, L.; Devys, E.; Arroyo Ohori, K.; Olsson, P.; Stoter, J. Eurosdr geoBIM project a study in Europe on how to use the potentials of bim and geo data in practice. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 42, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.; Couto, C.D.; Costin, A. Data Integration and Innovation: The Future of the Construction, Infrastructure, and Transportation Industries. Future Inf. Exch. Interoperability 2019, 85, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Pan, Y.; Luo, X. Integration of BIM and GIS in sustainable built environment: A review and bibliometric analysis. Autom. Constr. 2019, 103, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goonetillake, J.F. A Framework for the Integration of Information Requirements within Infrastructure Digital Construction. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bills, T.C. The Great Transformation: The Future of the Data-Driven Transportation Workforce; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, A.S. Emerging Technologies & Their Adoption across USDOTs: A Pursuit to Optimize Performance in Highway Infrastructure Project Delivery. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Hamledari, H.; Billington, S.; Fischer, M. 4D Beyond Construction: Spatio-Temporal and Life-Cyclic Modeling and Visualization of Infrastructure Data. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2018, 23, 285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Burton, H.V.; Lallemant, D. Adaptive Decision-Making for Civil Infrastructure Systems and Communities Exposed to Evolving Risks. Struct. Saf. 2018, 75, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkasisbeh, M.R. An Integrated Decision Support Framework for Lifecycle Building Asset Management. Ph.D. Thesis, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rashidi, A.; Karan, E. Video to BrIM: Automated 3D As-Built Documentation of Bridges. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2018, 32, 04018026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, B. Civil Integrated Management for Highway Infrastructure Projects: Analyses of Trends, Specifications, Impact, and Maturity. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, A.W.Z.; Ji, A.; Zhang, L. Large-Scale 3D Point-Cloud Semantic Segmentation of Urban and Rural Scenes Using Data Volume Decomposition Coupled with Pipeline Parallelism. Autom. Constr. 2021, 133, 926–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Turkan, Y.; Jahren, C.T.; Jeong, H.D. Civil Information Modeling Adoption by Iowa and Missouri DOTs. In Computing in Civil and Building Engineering; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2014; pp. 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; Turkan, Y. BrIM and UAS for bridge inspections and management. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2020, 27, 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodima-Taylor, D. Digitalizing land administration: The geographies and temporalities of infrastructural promise. Geoforum 2021, 122, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Ma, L.; Broyd, T.; Chen, K. Digital Twin and Its Implementations in the Civil Engineering Sector. Autom. Constr. 2021, 130, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Oyedele, L.O.; Qadir, J.; Munir, K.; Ajayi, S.O.; Akinade, O.O.; Owolabi, H.A.; Alaka, H.A.; Pasha, M. Big Data in the Construction Industry: A Review of Present Status, Opportunities, and Future Trends. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2016, 30, 500–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilventhan, A.; Rajadurai, R. 4D Bridge Information Modelling for management of bridge projects: A case study from India. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2020, 10, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawlana, M.; Vahdatikhaki, F.; Doriani, A.; Hammad, A. Integrating 4D modeling and discrete event simulation for phasing evaluation of elevated urban highway reconstruction projects. Autom. Constr. 2015, 60, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, N.; Turkan, Y. Bridge Construction Progress Monitoring Using Lidar and 4d Design Models. Autom. Constr. 2020, 109, 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargoum, S.A.; Karsten, L. Virtual Assessment of Sight Distance Limitations Using LIDAR Technology: Automated Obstruction Detection and Classification. Autom. Constr. 2021, 125, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaloo, A.; Lattanzi, D.; Cunningham, K.; Dell’andrea, R.; Riley, M. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Inspection of the Placer River Trail Bridge through Image-Based 3D Modelling. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2018, 14, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistorius, C. The Impact of New Technologies on the Construction Industry. Constr. Train. Fund 2017, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Duque, L.; Seo, J.; Wacker, J. Synthesis of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Applications for Infrastructures. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2018, 32, 04018046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhong, X.; Zhao, C.; Chen, Y.F.; Zhang, T. The Feasibility Assessment Study of Bridge Crack Width Recognition in Images Based on Special Inspection UAV. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8811649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Chambi, E.; Villarroel-Quezada, S.; Atencio, E.; Rivera, F.M.-L. Analysis of Optimal Flight Parameters of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) for Detecting Potholes in Pavements. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-H.; Jeon, H.; Baek, S.-C.; Hong, W.-H.; Jung, H.-J. Application of Crack Identification Techniques for an Aging Concrete Bridge Inspection Using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Sensors 2018, 18, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, B.F., Jr.; Hoskere, V.; Narazaki, Y. Advances in Computer Vision-Based Civil Infrastructure Inspection and Monitoring. Engineering 2019, 5, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.A.; Blas, H.S.S.; García, D.P.; Mendes, A.S.; González, G.V. An Architectural Multi-Agent System for a Pavement Monitoring System with Pothole Recognition in UAV Images. Sensors 2020, 20, 6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cervone, G.; Yang, L. Detection of Asphalt Pavement Potholes and Cracks Based on the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Multispectral Imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 3701–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Cui, L.; Qi, Z.; Meng, F.; Chen, Z. Automatic Road Crack Detection Using Random Structured Forests. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 17, 3434–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Sekimoto, Y.; Seto, T.; Kashiyama, T.; Omata, H. Road Damage Detection and Classification Using Deep Neural Networks with Smartphone Images. Comput. Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2018, 33, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C.; Brilakis, I. Pothole Detection in Asphalt Pavement Images. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2011, 25, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, M.H.; Azhar, K.; Murtaza, F.; Hussain, F. Visual analysis of asphalt pavement for detection and localization of potholes. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2018, 38, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Cao, Y.; Li, Q.; Mao, Q.; Wang, S. CrackTree: Automatic crack detection from pavement images. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2012, 33, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Cao, M.; He, L.; Zhang, B. An efficient and reliable coarse-to-fine approach for asphalt pavement crack detection. Image Vis. Comput. 2017, 57, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Bansal, D.; Sofat, S.; Aggarwal, N. Smart Patrolling: An Efficient Road Surface Monitoring Using Smartphone Sensors and Crowdsourcing. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2017, 40, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Q.; Gül, M. A Cost Effective Solution For Pavement Crack Inspection Using Cameras and Deep Neural Networks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 256, 119397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cylwik, E.; Dwyer, K. Virtual Design and Construction in Horizontal Infrastructure Projects. Eng. News-Rec. 2012. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/s/JyVTYVcwcqNyJW7s (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Girardet, A.; Boton, C. A parametric BIM approach to foster bridge project design and analysis. Autom. Constr. 2021, 126, 103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Sharma, R.; Akram, S.V.; Gehlot, A.; Buddhi, D.; Malik, P.K.; Arya, R. Highway 4.0: Digitalization of highways for vulnerable road safety development with intelligent IoT sensors and machine learning. Saf. Sci. 2021, 143, 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinderts, J.P.; Lindenbergh, R.; van der Heide, D.H.; Amiri-Simkooei, A.; Truong-Hong, L. Clearance measurement validation for highway infrastructure with use of lidar point clouds. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 48, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleymanoglu, B.; Tamimi, R.; Yilmaz, Y.; Soycan, M.; Toth, C. Road infrastructure mapping by using iPhone 14 Pro: An accuracy assessment. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamas, D.; Justo, A.; Soilán, M.; Riveiro, B. 3D Point Cloud to Bim: Automated Application to Define IFC Alignment and Roadway Width Entities from Mls-Acquired Lidar Data of Mountain Roads. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, X-4/W2-2022, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.T.; Tran, H.H.; Quach, T.M. Combination of morphological and distributional filtering for UAV—LiDAR point cloud density to establish the Digital Terrain Model. J. Min. Earth Sci. 2022, 63, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraml, S.; Hubner, M.; Taupe, P.; Hofstätter, M.; Amon, P.; Rothbacher, D. Real-Time Gamma Radioactive Source Localization by Data Fusion of 3D-LiDAR Terrain Scan and Radiation Data from Semi-Autonomous UAV Flights. Sensors 2022, 22, 9198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivanna, V.M.; Guo, J.-I. Object Detection, Recognition, and Tracking Algorithms for ADASs—A Study on Recent Trends. Sensors 2024, 24, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Chen, X.; Jiang, J. A Staged Real-Time Ground Segmentation Algorithm of 3D LiDAR Point Cloud. Electronics 2024, 13, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleymanoglu, B.; Soycan, M.; Toth, C. 3D Road Boundary Extraction Based on Machine Learning Strategy Using LiDAR and Image-Derived MMS Point Clouds. Sensors 2024, 24, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhong, R.; Song, W.; Cao, S. Urban Functional Zone Classification Using Light-Detection-and-Ranging Point Clouds, Aerial Images, and Point-of-Interest Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Talha, S.; Manasreh, D.; Nazzal, M.D. The Use of Lidar and Artificial Intelligence Algorithms for Detection and Size Estimation of Potholes. Buildings 2024, 14, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Ma, L.; Li, L.; Liu, C.; Li, N.; Yang, Z.; Yao, Y.; Lu, H. A survey of remote sensing and geographic information system applications for flash floods. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Du, Z.; Zhang, F.; Huang, F.; Chen, J.; Li, W.; Guo, Z. Landslide susceptibility prediction based on remote sensing images and GIS: Comparisons of supervised and unsupervised machine learning models. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, S.; Kaysi, I.; Bedran, M. Geotechnical and environmental considerations in highway layouts: An integrated GIS assessment approach. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2000, 2, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakite, A.A.; Zlatanova, S. Automatic Geo-Referencing of BIM in GIS Environments Using Building Footprints. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 80, 101453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharineiat, Z.; Kurdi, F.T.; Campbell, G. Review of Automatic Processing of Topography and Surface Feature Identification LiDAR Data Using Machine Learning Techniques. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopac, N.; Jurdana, I.; Brnelić, A.; Krljan, T. Application of Laser Systems for Detection and Ranging in the Modern Road Transportation and Maritime Sector. Sensors 2022, 22, 5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tang, J.; Lao, S. Review of unmanned aerial vehicle swarm communication architectures and routing protocols. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SBarsanti, G.; Remondino, F.; Visintini, D. 3D Surveying and Modeling of Archaeological Sites—Some Critical Issues. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. 2013, 2, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Congress, S.S.C.; Puppala, A.J. Digital Twinning Approach for Transportation Infrastructure Asset Management Using UAV Data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transportation and Development 2021, Virtual, 8–10 June 2021; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2021; pp. 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandamini, C.; Maduranga, M.W.P.; Tilwari, V.; Yahaya, J.; Qamar, F.; Nguyen, Q.N.; Ibrahim, S.R.A. A Review of Indoor Positioning Systems for UAV Localization with Machine Learning Algorithms. Electronics 2023, 12, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Belton, D.; Helmholz, P.; Bourke, P.; McDonald, J. Pilbara rock art: Laser scanning, photogrammetry and 3D photographic reconstruction as heritage management tools. Herit. Sci. 2017, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-K.; Wang, Q.; Park, J.-W.; Cheng, J.C.; Sohn, H.; Chang, C.-C. Automated Dimensional Quality Assurance of Full-Scale Precast Concrete Elements Using Laser Scanning and BIM. Autom. Constr. 2016, 72, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, M.; Costantino, D.; Alfio, V.S.; Restuccia, A.G.; Papalino, N.M. Scan to BIM for the Digital Management and Representation in 3D GIS Environment of Cultural Heritage Site. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 50, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; He, G. A Review on Remote Sensing Data Fusion with Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN). IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 10, 295–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, A.; Cao, G.; Khan, Z.; Asad, M.; Aslam, M. Deep Learning-Based Change Detection in Remote Sensing Images: A Review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yao, L.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Ao, X.; Chen, Q.; Li, Z.; Meng, B. Road Pothole Extraction and Safety Evaluation by Integration of Point Cloud and Images Derived from Mobile Mapping Sensors. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2019, 42, 100936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspari, F.; Barbieri, F.; Demnati, I.; Ioli, F.; Pinto, L.; Toscani, V. Mobile mapping solutions for the update and management of traffic signs in a road cadastre free open-source GIS architecture. Int. Arch. Photo-Grammetry Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grešla, O.; Jašek, P. Measuring road structures using a mobile mapping system. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhashash, M.; Albanwan, H.; Qin, R. A Review of Mobile Mapping Systems: From Sensors to Applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, G.; Jing, G.; Feng, Q.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y. State-of-the-Art Review of Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) Applications for Railway Ballast Inspection. Sensors 2022, 22, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Qian, R.; Shang, K.; Guo, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D. Research on the Dynamic Monitoring Technology of Road Subgrades with Time-Lapse Full-Coverage 3D Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR). Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, P.; Yu, F.; Ai, M. A ground and underground urban roads surveying approach using integrated 3D LiDAR and 3D GPR technology. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 10, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanno, P.; Yaibok, C.; Pornbunyanon, T.; Kanjanakul, C.; Buathongkhue, C.; Tsumita, N.; Fukuda, A. GIS-based identification and analysis of suitable evacuation areas and routes in flood-prone zones of Nakhon Si Thammarat municipality. IATSS Res. 2023, 47, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Roy, N.; Zhang, B. Multi-objective transportation route optimization for hazardous materials based on GIS. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2023, 81, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, P. A QGIS-Based Road Network Analysis for Sustainable Road Network Infrastructure: An Application to the Cachar District in Assam, India. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, M.; Koloushani, M.; Ulak, M.B.; Ozguven, E.E.; Jouneghani, R.A. Statistical and Spatial Analysis of Hurricane-induced Roadway Closures and Power Outages. Energies 2020, 13, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Pu, H.; Schonfeld, P.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Peng, X.; Hu, J.; Liu, W. GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Railway Design with Spatial Environmental Considerations. Appl. Geogr. 2021, 131, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, M.; Effati, M.; Gilanifar, M.; Ozguven, E. Subway Station Site Selection Using GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Decision-Making: A Case Study in a Developing Country. Comput. Res. Prog. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lethanh, N.; Adey, B.T.; Burkhalter, M. Determining an Optimal Set of Work Zones on Large Infrastructure Networks in a GIS Framework. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2018, 24, 04017048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altıntaş, Y.D.; Ilal, M.E. Loose Coupling of GIS and BIM Data Models for Automated Compliance Checking against Zoning Codes. Autom. Constr. 2021, 128, 103743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolui, S.; Sarkar, S. Identifying Potential Landfill Sites Using Multicriteria Evaluation Modeling and GIS Techniques for Kharagpur City of West Bengal, India. Environ. Chall. 2021, 5, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’amico, F.; Calvi, A.; Schiattarella, E.; Di Prete, M.; Veraldi, V. BIM and GIS Data Integration: A Novel Approach of Technical/Environmental Decision-Making Process in Transport Infrastructure Design. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 45, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, N.; Ellul, C.; Cecconi, F.R.; Papapesios, N.; Dejaco, M.C. GeoBIM for built environment condition assessment supporting asset management decision making. Autom. Constr. 2021, 130, 103859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.G.; Shen, G.; Pulat, P. A Retro-Analysis of I-40 Bridge Collapse on Freight Movement in the U.S. Highway Network using GIS and Assignment Models. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2012, 1, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chen, G.; Huang, J.; Xu, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Sadick, A.-M. BIM and GIS Applications in Bridge Projects: A Critical Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, M.; Kirkman, R.; Cox, J.; Ringeisen, D. Benefits of Geographic Information Systems in Managing a Major Transportation Program. Transp. Res. Rec. 2012, 2291, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France-Mensah, J.; O’brien, W.J.; Khwaja, N.; Bussell, L.C. GIS-Based Visualization of Integrated Highway Maintenance and Construction Planning: A Case Study of Fort Worth, Texas. Vis. Eng. 2017, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantha, B.R.; Yatabe, R.; Bhandary, N.P. GIS-Based Highway Maintenance Prioritization Model: An Integrated Approach for Highway Maintenance in Nepal Mountains. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswein, V.; Goncalves, A.B.; Silvestre, J.D.; Freire, F.; Habert, G.; Kurda, R. Transportation Matters—Does It? GIS-Based Comparative Environmental Assessment of Concrete Mixes with Cement, Fly Ash, Natural and Recycled Aggregates. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 137, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Wright, G.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Li, X.; Liu, R. A State-of-the-Art Review on the Integration of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Geographic Information System (GIS). ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, Z. LTPP data-based investigation on asphalt pavement performance using geospatial hot spot analysis and decision tree models. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 606–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K.; Dawson, R.J.; Mills, J.P.; Blythe, P.; Robson, C.; Morley, J. Assessing the impact of heavy rainfall on the Newcastle upon Tyne transport network using a geospatial data infrastructure. Resilient Cities Struct. 2023, 2, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Mao, F.; Gong, Z.; Hannah, D.M.; Cai, Y.; Wu, J. A disaster-damage-based framework for assessing urban resilience to intense rainfall-induced flooding. Urban Clim. 2023, 48, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.A.; Mohajane, M.; Parvin, F.; Varasano, A.; Hitouri, S.; Łupikasza, E.; Pham, Q.B. Mass movement susceptibility prediction and infrastructural risk assessment (IRA) using GIS-based Meta classification algorithms. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 145, 110591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Segura, T.; Montalbán-Domingo, L.; Llopis-Castelló, D.; Sanz-Benlloch, A.; Pellicer, E. Integration of deep learning techniques and sustainability-based concepts into an urban pavement management system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 231, 120851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfranco, F.; Mariangela, D.; Patrizia, S.; Edoardo, P.; Massimiliano, P. A GIS-supported methodology for the functional classification of road networks. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawchar, L.; Naughton, O.; Nolan, P.; Stewart, M.G.; Ryan, P.C. A GIS-Based Framework for High-Level Climate Change Risk Assessment of Critical Infrastructure. Clim. Risk Manag. 2020, 29, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenais, A. Developing an Augmented Reality Solution for Mapping Underground Infrastructure. Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, B.; Almeida, P.G.; Maganinho, L. Data Collection Methodology to Assess Road Pavement Condition Using GNSS, Video Image and GIS. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 603, 042083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, F. Crack image recognition on fracture mechanics cross valley edge detection by fractional differential with multi-scale analysis. Signal Image Video Process. 2023, 17, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ng, S.T.; Dao, J.; Zhou, S.; Xu, F.J.; Xu, X.; Zhou, Z. BIM-GIS-DCEs Enabled Vulnerability Assessment of Interdependent Infrastructures—A Case of Stormwater Drainage-Building-Road Transport Nexus in Urban Flooding. Autom. Constr. 2021, 125, 103626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krassakis, P.; Pyrgaki, K.; Gemeni, V.; Roumpos, C.; Louloudis, G.; Koukouzas, N. GIS-Based Subsurface Analysis and 3D Geological Modeling as a Tool for Combined Conventional Mining and In-Situ Coal Conversion: The Case of Kardia Lignite Mine, Western Greece. Mining 2022, 2, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T.; Kostyniuk, L.; Green, P.; Barnes, M.; Blower, D.; Bogard, S.; Blankespoor, A.; LeBlanc, D.; Cannon, B.; McLaughlin, S.; et al. A Multivariate Analysis of Crash and Naturalistic Driving Data in Relation to Highway Factors; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulwahid, S.N.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Ibrahim, N.; Zaidan, B.B.; Ameen, H.A. Modeling Motorcyclists’ Aggressive Driving Behavior Using Computational and Statistical Analysis of Real-Time Driving Data to Improve Road Safety and Reduce Accidents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aamri, A.K.; Hornby, G.; Zhang, L.-C.; Al-Maniri, A.A.; Padmadas, S.S. Mapping Road traffic crash hotspots using GIS-based methods: A case study of Muscat Governorate in the Sultanate of Oman. Spat. Stat. 2021, 42, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Carrillo, J.; Torres-Ruiz, M.; Davis, C.A.; Quintero, R.; Moreno-Ibarra, M.; Guzmán, G. Traffic Congestion Analysis Based on a Web-GIS and Data Mining of Traffic Events from Twitter. Sensors 2021, 21, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompigna, A.; Mauro, R. A Statistical Simulation Model for the Analysis of the Traffic Flow Reliability and the Probabilistic Assessment of the Circulation Quality on a Freeway Segment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droj, G.; Droj, L.; Badea, A.-C. GIS-Based Survey over the Public Transport Strategy: An Instrument for Economic and Sustainable Urban Traffic Planning. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Suman, S.; Bharti, H. Planning of rural road network using sustainable practices to maximize the accessibility to health and education facilities using ant colony optimization. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannat, K.E.; Adnan, M.S.G.; Dewan, A. A GIS-Based Approach to Evaluating Environmental Influences on Active and Public Transport Accessibility of University Students. J. Urban Manag. 2020, 9, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, A.; Gu, X.; Chen, L.; Hystad, P. Predicting Perceptions of the Built Environment Using GIS, Satellite and Street View Image Approaches. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 216, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, K.P.; Bhattarai, K.; Gauthier, W.M.; Hall, L.M. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Based Model of Dairy Manure Transportation and Application with Environmental Quality Consideration. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 1634–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Eng, B. Environmental Impact Assessment for Transportation Corridors Using GIS. Ph.D. Thesis, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, M.A.; Ben Hamida, E.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Bhargava, B. Adaptive Security for Intelligent Transport System Applications. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2018, 10, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Qin, J.; Li, J.; Wu, M.; Zhou, S.; Feng, L. Optimal Transshipment Route Planning Method Based on Deep Learning for Multimodal Transport Scenarios. Electronics 2023, 12, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, Y.; Alemayehu, E.; Schroeder, D. Examining Car Accident Prediction Techniques and Road Traffic Congestion: A Comparative Analysis of Road Safety and Prevention of World Challenges in Low-Income and High-Income Countries. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 2023, 6643412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Management & Budget. Highway Performance Monitoring System Manual; Control No. 2125-0028; Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), USDOT: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, L.; Teo, E.A.L.; Low, S.P. A project management framework for enhanced productivity performance using building information modelling. Constr. Econ. Build. 2017, 17, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Park, N.; Choi, J. A BIM-Based Design Method for Energy-Efficient Building. In Proceedings of the 2009 Fifth International Joint Conference on INC, IMS and IDC, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 25–27 August 2009; pp. 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcauley, B.; Hore, A.; West, R. Global BIM Study. BICP Ir. BIM Study 2017, 4, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, B.; Clevenger, C.M.; Ozbek, M.E.; Mahmoud, H. Implementing BIM on Infrastructure: Comparison of Two Bridge Construction Projects. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2015, 20, 04014044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Li, X.; Xie, H.; Lu, C. Urban land expansion and arable land loss in China—A case study of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. Land Use Policy 2005, 22, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Tang, B.; Fwa, T.F. Evaluation of functional characteristics of laboratory mix design of porous pavement materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 191, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephson, P.-E.; Larsson, B.; Li, H. Illustrative Benchmarking Rework and Rework Costs in Swedish Construction Industry. J. Manag. Eng. 2002, 18, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancardo, S.A.; Capano, A.; de Oliveira, S.G.; Tibaut, A. Integration of BIM and Procedural Modeling Tools for Road Design. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Tang, L.; Zhou, T.; Wen, Y.; Xu, R.; Deng, W. Automatic Layer Classification Method-Based Elevation Recognition in Architectural Drawings for Reconstruction of 3D BIM Models. Autom. Constr. 2020, 113, 103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Unkefer, D. Guide for 3D Engineered Models for Bridges and Structures; Federal Highway Administration, United States Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/construction/3d/hif17039.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Chow, J.K.; Liu, K.-F.; Tan, P.S.; Su, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.-H. Automated Defect Inspection of Concrete Structures. Autom. Constr. 2021, 132, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, B.; Atadero, R.; Clevenger, C.; Ozbek, M.E. Bridge Information Modeling for Inspection and Evaluation. J. Bridge Eng. 2016, 21, 04015076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Shariat, S.; Abdullah, J.; Devkota, B. Maximizing Resource Effectiveness of Highway Infrastructure Maintenance Inspection and Scheduling for Efficient City Logistics Operations. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 39, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán, Á.M.; Alberti, M.G.; Álvarez, A.A.; Trigueros, J.A. New Perspectives for BIM Usage in Transportation Infrastructure Projects. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddupalli, C.; Sadhu, A.; Rezazadeh Azar, E.; Pattyson, S. Improved Visualization of Infrastructure Monitoring Data Using Building Information Modeling. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2019, 15, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, T.; Heikkilä, R. Infra BIM-Based Real-Time Quality Control of Infrastructure Construction Projects. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction and Mining: Connected to the Future, Proceedings, Oulu, Finland, 15–18 June 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, Q.; Shahrour, I.; Li, J.; Zhou, B. A Real-Time Interaction Platform for Settlement Control during Shield Tunnelling Construction. Autom. Constr. 2018, 94, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, F.; Chummers, L.E.; Pulikanti, S.; Struthers, J.Q.; Mallela, J.; Morgan, R.H. Utilizing 3D Digital Design Data in Highway Construction-Case Studies; FHWA: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- 3D Engineered Model Guidance Report by MDOT, State Highway Administration, Maryland. 2019. Available online: https://www.roads.maryland.gov/ohd2/MDOT-SHA-3DEngineeredModelGuidance-Jan2019.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Maier, F.; Mallela, J.; Torres, H.; Ruiz, J.M.; Chang, G.; Chummers, L.; Pulikanti, S.; Struthers, J.; Morgan, R. Guide for Using 3D Engineered Models for Construction Engineering and Inspection; Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, A.Z.; Ferreira, M.M.; Rosário, D.P.; Martins, O.P. 3D and VR models in Civil Engineering education: Construction, rehabilitation and maintenance. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boton, C. Supporting Constructability Analysis Meetings with Immersive Virtual Reality-Based Collaborative BIM 4D Simulation. Autom. Constr. 2018, 96, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, N.S.; Shim, C.S. BIM-Based Innovative Bridge Maintenance System Using Augmented Reality Technology. Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. 2020, 54, 1217–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, C.S.; Kang, H.; Dang, N.S.; Lee, D. Development of BIM-Based Bridge Maintenance System for Cable-Stayed Bridges. Smart Struct. Syst. 2017, 20, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensafi, M.; Harode, A.; Thabet, W. Developing Systems-Centric as-Built BIMs to Support Facility Emergency Management: A Case Study Approach. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 104003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, B.; Buda, A.; Nurminen, A.; Främling, K. A Framework for Integrating BIM and IoT through Open Standards. Autom. Constr. 2018, 95, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Sresakoolchai, J.; Zhou, Z. Sustainability-based lifecycle management for bridge infrastructure using 6D BIM. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y. Research on dynamic data monitoring of steel structure building information using BIM. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2020, 18, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, W.J.; Gau, P.; Schmeits, C.; Goyat, J.; Khwaja, N. Benefits of Three- and Four-Dimensional Computer-Aided Design Model Applications for Review of Constructability. Transp. Res. Rec. 2012, 2268, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Ma, T.; Zhang, J.; Guan, Y.; Chen, L. Integrating Three-Dimensional Road Design and Pavement Structure Analysis Based on BIM. Autom. Constr. 2020, 113, 103152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Lo, N.-H.; Hu, H.-T.; Hsu, Y.-T. Collaboration-Based BIM Model Development Management System for General Contractors in Infrastructure Projects. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 8834389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.-G.; Cho, H.-H.; Cho, N.-S.; Kang, K.-I. Parametric modelling based approach for efficient quantity takeoff of NATM-Tunnels. In Proceedings of the 2012 Proceedings of the 29th International Symposium of Automation and Robotics in Construction, ISARC 2012, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 26–29 June 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadnejad, F.; Gillins, D.T.; Higgins, C.C.; Gillins, M.N. BridgeDex: Proposed Web GIS Platform for Managing and Interrogating Multiyear and Multiscale Bridge-Inspection Images. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2017, 31, 04017061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, C.; Yun, N.; Song, H. Application of 3D bridge information modeling to design and construction of bridges. Procedia Eng. 2011, 14, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzerillo, L.; Acuto, F.; Pisciotta, A.; Dunn, I.; Mantalovas, K.; Uddin, M.Z.; Di Mino, G. ISIM-infrastructures & structures information modeling: A new concept of bim for infrastructures. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignali, V.; Acerra, E.M.; Lantieri, C.; Di Vincenzo, F.; Piacentini, G.; Pancaldi, S. Building information Modelling (BIM) application for an existing road infrastructure. Autom. Constr. 2021, 128, 103752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, G.Q.; Wu, P.; Yue, T. Integrating Building Information Modeling and Prefabrication Housing Production. Autom. Constr. 2019, 100, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, O.; Prusov, D.; Chetverikov, B.; Malanchuk, M. Conceptual principles of geospatial data geoinformation integration for administrative and economic management of transport infrastructure facilities. Adv. Geodesy Geoinf. 2023, 71, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, N.-S.; Rho, G.-T.; Shim, C.-S. A master digital model for suspension bridges. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Lee, Y.B.; Shim, C.S.; Park, K.L. Bridge information models for construction of a concrete box-girder bridge. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2012, 8, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafiso, S.; Di Graziano, A.; D’Agostino, C.; Pappalardo, G.; Delfino, E. A new perspective in the road asset management with the use of advanced monitoring system & BIM. In MATEC Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2018; Volume 231, p. 01007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Hou, R.; Lynch, J.P.; Sohn, H.; Law, K.H. An information modeling framework for bridge monitoring. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2017, 114, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomani, H.; Almutairi, O.N. Life-cycle maintenance management strategies for bridges in kuwait. J. Environ. Treat. Tech. 2020, 8, 1556–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.-H.; Li, Y.-F.; Guo, J.; Li, Y. Integration Research and Design of the Bridge Maintenance Management System. Procedia Eng. 2011, 15, 5429–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z. Research on Measuring Instrument of Bridge Building Bearing Capacity Based on Computer BIM Technology. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1574, 012110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettis, A.; Saponaro, M.; Nanna, M. RPAS-Based Framework for Simplified Seismic Risk Assessment of Italian RC-Bridges. Buildings 2020, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Ding, R.; Li, H. Building an Ontological Knowledgebase for Bridge Maintenance. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2019, 130, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Nieto, C.; Shan, Y.; Lewis, P.; Hartell, J.A. Bridge Maintenance Prioritization Using Analytic Hierarchy Process and Fusion Tables. Autom. Constr. 2019, 101, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappos, A.; Sextos, A.; Stefanidou, S.; Mylonakis, G.; Pitsiava, M.; Sergiadis, G. Seismic Risk of Inter-Urban Transportation Networks. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 18, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S. Three-Dimensional Laser Combined with BIM Technology for Building Modeling, Information Data Acquisition, and Monitoring. Nonlinear Opt. Quantum Opt. 2020, 52, 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Aattan, S.A.A.; Al-Bakri, M. Development of Bridges Maintenance Management System Based on Geographic Information System Techniques (Case study: Al-Muthanna\Iraq). J. Eng. 2020, 26, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.-I.; Chen, J.-H.; Huang, P.-F. The study of BIM-based MRT structural inspection system. J. Mech. Eng. Autom. 2012, 2, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Zhou, Y.; Akinci, B. Building Information Modeling (BIM) Application Framework: The Process of Expanding from 3D to Computable nD. Autom. Constr. 2014, 46, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamledari, H.; McCabe, B.; Davari, S.; Shahi, A.; Azar, E.R.; Flager, F. Evaluation of Computer Vision and 4D BIM-Based Construction Progress Tracking on a UAV Platform. In Proceedings of the 6th CSCE-CRC International Construction Specialty Conference 2017—Held as Part of the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering Annual Conference and General Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 31 May–3 June 2017; Volume 1, pp. 621–630. Available online: https://purl.stanford.edu/wh873cw2351 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Xuehui, A.; Li, Z.; Zuguang, L.; Chengzhi, W.; Pengfei, L.; Zhiwei, L. Dataset and Benchmark for Detecting Moving Objects in Construction Sites. Autom. Constr. 2021, 122, 103482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, M.S.; RezaZadeh, M.; Khanzadi, M.; Taghaddos, H. Integrated BIM-Based Simulation for Automated Time-Space Conflict Management in Construction Projects. Autom. Constr. 2021, 132, 103957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Deng, Y.; Won, J.; Cheng, J.C. An Integrated Underground Utility Management and Decision Support Based on BIM and GIS. Autom. Constr. 2019, 107, 102931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irizarry, J.; Karan, E.P.; Jalaei, F. Integrating BIM and GIS to Improve the Visual Monitoring of Construction Supply Chain Management. Autom. Constr. 2013, 31, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bai, Q. Optimization in Decision Making in Infrastructure Asset Management: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Ma, T.; Chen, S. Asphalt pavement maintenance plans intelligent decision model based on reinforcement learning algorithm. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 299, 124278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yin, G.; Wang, X.; Yan, W. Automated decision making in highway pavement preventive maintenance based on deep learning. Autom. Constr. 2022, 135, 104111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, S.; Fan, L.; Suzuki, Y. Assessment of Urban Energy Performance through Integration of BIM and GIS for Smart City Planning. Procedia Eng. 2017, 180, 1462–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Nwadigo, O.; GhaffarianHoseini, A.; Naismith, N.; Tookey, J.; Raahemifar, K. Application of nD BIM Integrated Knowledge-Based Building Management System (BIM-IKBMS) for Inspecting Post-Construction Energy Efficiency. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Lamallam, S.; Yaagoubi, R.; Sebari, I.; Doukari, O. Extending the IFC Standard to Enable Road Operation and Maintenance Management Through OpenBIM. ISPRS Int. J. Geoinf. 2021, 10, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y. Mapping of BIM and GIS for Interoperable Geospatial Data Management and Analysis for the Built Environment; Hong Kong University of Science and Technology: Hong Kong, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H.; Deng, X. interoperability analysis of IFC-based data exchange between heterogeneous BIM software. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2018, 24, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osello, A.; Rapetti, N.; Semeraro, F. BIM Methodology Approach to Infrastructure Design: Case Study of Paniga Tunnel. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 062052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floros, G.S.; Ruff, P.; Ellul, C. Impact of Information Management during Design & Construction on Downstream BIM-GIS interoperability for rail infrastructure. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 6, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulfattah, B.S.; Abdelsalam, H.A.; Abdelsalam, M.; Bolpagni, M.; Thurairajah, N.; Perez, L.F.; Butt, T.E. Predicting implications of design changes in BIM-based construction projects through machine learning. Autom. Constr. 2023, 155, 105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Ma, T.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Parametric modeling and structure verification of asphalt pavement based on BIM-ABAQUS. Autom. Constr. 2020, 111, 103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpozzo, E.; Balletti, C. Bridging the gap: An open-source gis+bim system for archaeological data. The case study of altinum, Italy. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, B.; Nevett, G.; O’Brien, W.J.; Goodrum, P.M.; Johnson, J. Civil Integrated Management: Empirical study of digital practices in highway project delivery and asset management. Autom. Constr. 2018, 87, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ng, S.T.; Xu, F.J.; Skitmore, M.; Zhou, S. Towards Resilient Civil Infrastructure Asset Management: An Information Elicitation and Analytical Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peraka, N.S.P.; Biligiri, K.P. Pavement asset management systems and technologies: A review. Autom. Constr. 2020, 119, 103336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, V.; Hsu, S.-C. An open-source and extensible platform for general infrastructure asset management system. Autom. Constr. 2021, 127, 103692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garramone, M.; Scaioni, M. A BIM/GIS digitalization process to explore the potential of disused railways in Italy. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Hassan, F.; Le, C.; Jeong, H.D. Understanding Dynamic Data Interaction between Civil Integrated Management Technologies: A Review of Use Cases and Enabling Techniques. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 22, 1011–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Meng, W.; Liu, Y.; Ti, J. A Framework of Pavement Management System Based on IoT and Big Data. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 47, 101226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Ryu, K.R.; Ham, S. Spatial analysis leveraging machine learning and GIS of socio-geographic factors affecting cost overrun occurrence in roadway projects. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 104007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yan, W.; Kou, J.; Li, Z. Collaboration and Management of Heterogeneous Robotic Systems for Road Network Construction, Management, and Maintenance under the Vision of “BIM + GIS” Technology. J. Robot. 2023, 2023, 8259912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noardo, F.; Harrie, L.; Ohori, K.A.; Biljecki, F.; Ellul, C.; Krijnen, T.; Eriksson, H.; Guler, D.; Hintz, D.; Jadidi, M.A.; et al. Tools for BIM-GIS integration (IFC georeferencing and conversions): Results from the GeoBIM benchmark 2019. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Chen, W.; Chen, K. Digital Twins for Construction Sites: Concepts, LoD Definition, and Applications. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04021094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, E.; Iacono, E.; Matrone, F.; Ventura, G.M. The development of a 2D/3D BIM-GIS web platform for planned maintenance of built and cultural heritage: The MAIN10ANCE project. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, Z.; Riaz, Z.; Arslan, M. Leveraging BIM and Big Data to deliver well maintained highways. Facilities 2017, 35, 818–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Lin, J.-R.; Zhang, J.-P.; Hu, Z.-Z. A hybrid data mining approach on BIM-based building operation and maintenance. Build. Environ. 2017, 126, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaganova, O.; Telgarsky, J. Management of capital assets by local governments: An assessment and benchmarking survey. Int. J. Strat. Prop. Manag. 2018, 22, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Ng, S.T.; Skitmore, M. An Interdependent Infrastructure Asset Management Framework for High-Density Cities. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Munic. Eng. 2019, 174, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.; Patel, H.; Dave, B. Development of integrated cloud-based Internet of Things (IoT) platform for asset management of elevated metro rail projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 1993–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Kapogiannis, G.; Tang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Jimenez-Bescos, C.; Yang, T. Influence of an integrated value-based asset condition assessment in built asset management. Constr. Innov. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Meng, Q. Impacts of pavement deterioration and maintenance cost on Pareto-efficient contracts for highway franchising. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 113, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Ogallo, H.G.; Owolabi, O. A Quantitative Analysis of Sustainability and Green Transportation Initiatives in Highway Design and Maintenance. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 111, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France-Mensah, J.; Kothari, C.; O’Brien, W.J.; Jiao, J. Integrating Social Equity in Highway Maintenance and Rehabilitation Programming: A Quantitative Approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 48, 101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moins, B.; France, C.; Bergh, W.V.D.; Audenaert, A. Implementing life cycle cost analysis in road engineering: A critical review on methodological framework choices. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 110284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, S.; Xu, S.; Huang, Z. Preliminary Study on Comparison of Knowledge-Based and Technology-Based BIM Research on Infrastructure. In Proceedings of the CICTP 2020, Xi’an, China, 14–16 August 2020; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; pp. 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Mbachu, J. Highway Alignment Optimization: An Integrated BIM and GIS Approach. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Dong, Q.; Ni, F.; Wang, L. LCA and LCCA based multi-objective optimization of pavement maintenance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Ma, T.; Fang, Z. Characterization of agglomeration of reclaimed asphalt pavement for cold recycling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 240, 117912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Loh, K.J.; Yi, J.-H.; Yun, C.-B. Performance monitoring of the Geumdang Bridge using a dense network of high-resolution wireless sensors. Smart Mater. Struct. 2006, 15, 1561–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Shelden, D.R.; Eastman, C.M.; Pishdad-Bozorgi, P.; Gao, X. A review of building information modeling (BIM) and the internet of things (IoT) devices integration: Present status and future trends. Autom. Constr. 2019, 101, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezel, A.; Fellow, R.; Aziz, Z. From conventional to IT-based visual management: A conceptual discussion for lean construction. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2017, 22, 220–246. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Sensing Information Modeling for Smart City. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Smart City/SocialCom/SustainCom (SmartCity), IEEE, Chengdu, China, 9–21 December 2015; pp. 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Su, G.; Chen, J.; Du, P. Design of an IoT-BIM-GIS Based Risk Management System for Hospital Basic Operation. In Proceedings of the 11th IEEE International Symposium on Service-Oriented System Engineering, SOSE 2017, San Francisco, CA, USA, 6–9 April 2017; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Anumba, C.J.; Parfitt, M.K. Cyber-physical systems for temporary structure monitoring. Autom. Constr. 2016, 66, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Park, M.-W.; Vela, P.A.; Golparvar-Fard, M. Construction performance monitoring via still images, time-lapse photos, and video streams: Now, tomorrow, and the future. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2015, 29, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzel, R.; Teizer, J.; Mueller, M.; Blickle, A. SmartSite: Intelligent and autonomous environments, machinery, and processes to realize smart road construction projects. Autom. Constr. 2016, 71, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokshina, I.V.; Greguš, M.; Thomas, W.L. Application of integrated building information modeling, IoT and blockchain technologies in system design of a smart building. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 160, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, A.P.; Ordieres-Meré, J.; Loreiro, Á.P.; de Marcos, L. Opportunities in airport pavement management: Integration of BIM, the IoT and DLT. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 90, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.P.; Chen, W.; Chen, K.; Wang, Q. Data-driven predictive maintenance planning framework for MEP components based on BIM and IoT using machine learning algorithms. Autom. Constr. 2020, 112, 103087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Zhang, H.; Ai, Q.; Bao, T.; Yan, J. CBR-RBR fusion based parametric rapid construction method of bridge BIM model. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 57, 102086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelete, S.G.; Vaillancourt, R.; Nour, G.A.; Gauthier, F.; Gaha, M. Maintenance optimisation using intelligent asset management in electricity distribution companies. Int. J. Prod. Lifecycle Manag. 2023, 15, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Ma, T.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Han, C. A BIM-IoT and intelligent compaction integrated framework for advanced road compaction quality monitoring and management. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 100, 107981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Olgun, G.; Assaad, R.H. A BIM-enabled digital twin framework for real-time structural health monitoring using IoT sensing, digital signal processing, and structural analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadamosi, A.-Q.; Oyedele, L.O.; Delgado, J.M.D.; Kusimo, H.; Akanbi, L.; Olawale, O.; Muhammed-Yakubu, N. IoT for predictive assets monitoring and maintenance: An implementation strategy for the UK rail industry. Autom. Constr. 2021, 122, 103486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, Z.; Vahidnia, M.H.; Aghamohammadi, H.; Azizi, Z.; Behzadi, S. Digital twins and 3D information modeling in a smart city for traffic controlling: A review. J. Geogr. Cartogr. 2023, 6, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S.; Doran, M.-A. geoSmartCity: Geomatics contribution to the Smart City. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 17–20 June 2013; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donalek, C.; Djorgovski, S.G.; Cioc, A.; Wang, A.; Zhang, J.; Lawler, E.; Yeh, S.; Mahabal, A.; Graham, M.; Drake, A.; et al. Immersive and collaborative data visualization using virtual reality platforms. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Washington, DC, USA, 27–30 October 2014; pp. 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yang, G.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, A. Digital twin enhanced BIM to shape full life cycle digital transformation for bridge engineering. Autom. Constr. 2023, 147, 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, E.; Trifarò, C.A. Knowledge and Digitalization: A way to improve safety of Road and Highway Infrastructures. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2022, 44, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shu, X.; Qiao, P.; Li, S.; Xu, J. Developing a digital twin model for monitoring building structural health by combining a building information model and a real-scene 3D model. Measurement 2023, 217, 112955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Feng, H.; Chen, Q.; de Soto, B.G. Developing a conceptual framework for the application of digital twin technologies to revamp building operation and maintenance processes. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 49, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Pan, Y. BIM-supported automatic energy performance analysis for green building design using explainable machine learning and multi-objective optimization. Appl. Energy 2023, 333, 120575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursini, A.; Grazzini, A.; Matrone, F.; Zerbinatti, M. From scan-to-BIM to a structural finite elements model of built heritage for dynamic simulation. Autom. Constr. 2022, 142, 104518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Turkan, Y. A BIM-based simulation framework for fire safety management and investigation of the critical factors affecting human evacuation performance. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 44, 101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahedi, M.; Choi, J.; Seo, S.; Koo, C. Assessment of Estimation Methods for Demolition Waste Volume and Cost. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2024, Des Moines, IA, USA, 20–23 March 2024; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2024; pp. 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Dang, Y.; Lv, Z. Digital twins and artificial intelligence in transportation infrastructure: Classification, application, and future research directions. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 101, 107983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliniewicz, V.; Erol, D.; Johnsson, A. Leveraging Industry Standards to Build an Architecture for Asset Management and Predictive Maintenance. CIRED Conf. Proc. 2019, 57, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimian, F.P.; Seyedzadeh, S.; Oliver, S.; Rodriguez, S.; Dawood, N. On-demand monitoring of construction projects through a game-like hybrid application of BIM and machine learning. Autom. Constr. 2020, 110, 103012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghaish, F.; Chauhan, J.K.; Matarneh, S.; Pour Rahimian, F.; Hosseini, M.R. Artificial intelligence-based voice assistant for BIM data management. Autom. Constr. 2022, 140, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Advanced Surveying | Geospatial Analysis | nD Modeling | GeoBIM | Asset Management | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [18] | X | X | 2023 | |||

| [19] | X | 2023 | ||||

| [20] | X | X | 2023 | |||

| [21] | X | 2023 | ||||

| [22] | X | X | 2023 | |||

| [23] | X | X | X | 2023 | ||

| [24] | X | X | 2023 | |||

| [25] | X | X | 2023 | |||

| [26] | X | X | X | 2022 | ||

| [27] | X | X | X | X | 2022 | |

| [28] | X | X | X | 2022 | ||

| [29] | X | X | X | 2022 | ||

| [30] | X | X | 2022 | |||

| [31] | X | X | X | 2022 | ||

| [32] | X | X | 2022 | |||

| [33] | X | X | X | 2022 | ||

| [34] | X | X | 2022 | |||

| [35] | X | X | 2021 | |||

| [36] | X | X | 2021 | |||

| [37] | X | X | X | 2021 | ||

| [28] | X | X | 2021 | |||

| [38] | X | X | X | X | 2021 | |

| [39] | X | X | 2021 | |||

| [40] | X | X | X | 2021 | ||

| [41] | X | X | X | 2021 | ||

| [42] | X | X | 2020 | |||

| [43] | X | X | X | 2020 | ||

| [44] | X | X | 2020 | |||

| [45] | X | X | 2020 | |||

| [46] | X | X | 2020 | |||

| [7] | X | X | X | X | 2020 | |

| [47] | X | 2020 | ||||

| [48] | X | X | 2020 | |||

| [49] | X | 2019 | ||||

| [50] | X | X | 2019 | |||

| [51] | X | X | X | 2019 | ||

| [52] | X | X | 2019 | |||

| [11] | X | X | 2019 | |||

| [53] | X | X | X | 2019 | ||

| [54] | X | X | 2018 | |||

| [55] | X | X | 2018 | |||

| [6] | X | X | X | 2018 | ||

| [56] | X | 2018 | ||||

| [57] | X | X | X | 2018 | ||

| [58] | X | 2018 | ||||

| [59] | X | 2017 | ||||

| [10] | X | X | X | 2017 |

| Task | Geospatial Analysis | Techniques | Benefits | Limitation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pavement Engineering | Pavement condition monitoring, identifying pavement deterioration patterns | LiDAR, Image Processing, CAD | Improves the efficiency and effectiveness of road maintenance | High cost and technical expertise required for LiDAR data collection | [27,148,149] |

| Infrastructure Planning | Site selection, route alignment, visualizing proposed changes | GIS, CAD, 3D Modeling | Improves the efficiency and accuracy of infrastructure planning | Complex 3D modeling may require specialized software and skills | [46,146,150,151] |

| Road Safety Analysis | Identifying accident hotspots, safety audits, visualizing accident data | GIS, Statistical Analysis | Enhances road safety by identifying and addressing accident-prone areas | It requires robust and accurate incident reporting systems | [152,153,154] |

| Traffic Engineering | Analysis of traffic flow patterns and congestion points, route optimization, incident management | GPS, GIS, Traffic Simulation | Improves traffic flow and reduces congestion through detailed traffic pattern analysis | It may require substantial data collection and processing | [154,155,156] |

| Public Transport Planning | Route planning and optimization, accessibility analysis, demand estimation | GIS, Network Analysis | Enhances public transport service and increases ridership through optimized route planning | Dependent on accurate and current demographic data | [157,158,159] |

| Environmental Impact Analysis | Analyzing potential environmental impacts of transport projects, noise pollution mapping | GIS, Noise Modeling | Helps protect the environment and comply with regulations through detailed environmental impact analysis | Limited by the availability and quality of environmental data | [102,160,161,162] |

| Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) | Real-time traffic monitoring, route optimization, predictive modeling | GIS, Traffic Simulation, Machine Learning (ML) | Enhances traffic management and user experience through real-time monitoring and predictive modeling | Requires substantial investment in data infrastructure for real-time monitoring | [163,164,165] |

| Capability | CAD | GIS | BIM | 3D Scanning and Point Clouds | VR and AR | Generative AI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration | Moderate | High | High | Low | High | High |

| Accuracy | High | Moderate | High | High | Moderate | High |

| Visualization | High | High | High | Moderate | High | High |

| Data Management | Moderate | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| Time/Cost Efficiency | High | High | High | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| 3D Modeling | High | Low | High | High | High | High |

| Clash Detection | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Quantification | High | Moderate | High | N/A | N/A | High |

| Sustainability Analysis | Low | Low | High | Low | High | High |

| Performance Analysis | Low | Low | High | Low | High | High |

| Automated Design | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | High |

| Real-time Assessment | Low | Moderate | High | High | Moderate | High |

| Adaptive Optimization | N/A | N/A | Low | N/A | N/A | High |

| Predictive Dynamic Analysis | N/A | Moderate | High | Low | Moderate | High |

| Features | BIM System | GIS System | GeoBIM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Type | Object-oriented parametric modeling | Relational vector-based modeling | Hybrid (Combination of object-oriented and vector-based modeling) |

| Data Format Support | IFC, RVT, DGN, CAD, SKP | SHP, GDB, KML, GML | IFC, CityGML, GML, GeoJSON |

| Modeling Capabilities | Clash Detection, Quantity Takeoff, Cost Estimation, 4D Simulation | Spatial Query, Geo-statistics, Network Analysis, Geocoding | Integrated Geospatial Analysis with BIM Tools (Clash Detection, Quantity Takeoff, Cost Estimation, 4D Simulation, Spatial Query, Geo-statistics, Network Analysis) |

| Time Series Analysis | Limited (primarily 4D simulations) | Time Series Analysis, Real-time Data Integration | Time Series Analysis, Real-time Data Integration |

| Visualization | 3D Models, Renderings | Maps, Charts, Graphs | 3D Models integrated with geospatial components (Maps, Charts, Graphs) |

| Interoperability | Depending on the software, IFC offers broad compatibility | Generally high with standard formats such as SHP, KML | Can be challenging due to the integration of diverse data formats, but improving with standards such as CityGML |

| Scalability | Highly scalable but can be resource-intensive | Highly scalable, can handle large datasets | Depending on the model types and data formats being integrated, can be resource-intensive |

| Software Vendor | Autodesk, Graphisoft, Bentley Systems | Esri, QGIS, Google | ESRI, Autodesk, Bentley, Leica |

| Tasks | BIM Systems | GIS Systems | GeoBIM Systems | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Parametric Design, 3D Modeling | Spatial Design, Cartographic Design | Integrated Spatial and 3D Design | [168,233,234,235] |

| Analysis | Structural Analysis, Energy Analysis, Quantity Take Off | Spatial Analysis, Network Analysis, Terrain Analysis, Hot Spot Analysis, Temporal Analysis | Integrated Structural and Spatial Analysis | [196,236] |

| Coordination | Clash Detection, 4D Scheduling | Spatial Coordination, Network Coordination | Integrated Clash Detection and Spatial Coordination | [32,179,224,237] |

| Asset Management | Lifecycle Management, Condition Assessment, Maintenance Scheduling | Spatial Asset Management, Network Analysis | Integrated Lifecycle and Spatial Asset Management | [14,108,238,239,240,241,242] |

| Planning and Decision Making | 4D and 5D BIM (Time and Cost), Scenario Analysis | Spatial Planning, Network Planning | Integrated Spatial and Scenario Planning | [56,127,131,132] |

| Data Management | Data Layering, Parametric Data Management | Spatial Database Management, Metadata Management | Integrated Spatial and Parametric Data Management | [201,243,244] |

| Spatial Analysis | Local Space Planning, Site Analysis | Buffer Analysis, Overlay Analysis, Network Analysis | Integrated Space Planning and Spatial Analysis | [46,245] |

| Collaboration | Shared Model Approach, Cloud Collaboration | Shared Map Approach, Cloud Collaboration | Integrated Shared Model and Map Approach | [188,197,246,247] |