An Analysis of Urban Ethnic Inclusion of Master Plans—In the Case of Kabul City, Afghanistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. History of Master Planning Kabul

3. Materials and Methods

4. Result and Discussion

4.1. The First Three Master Pans

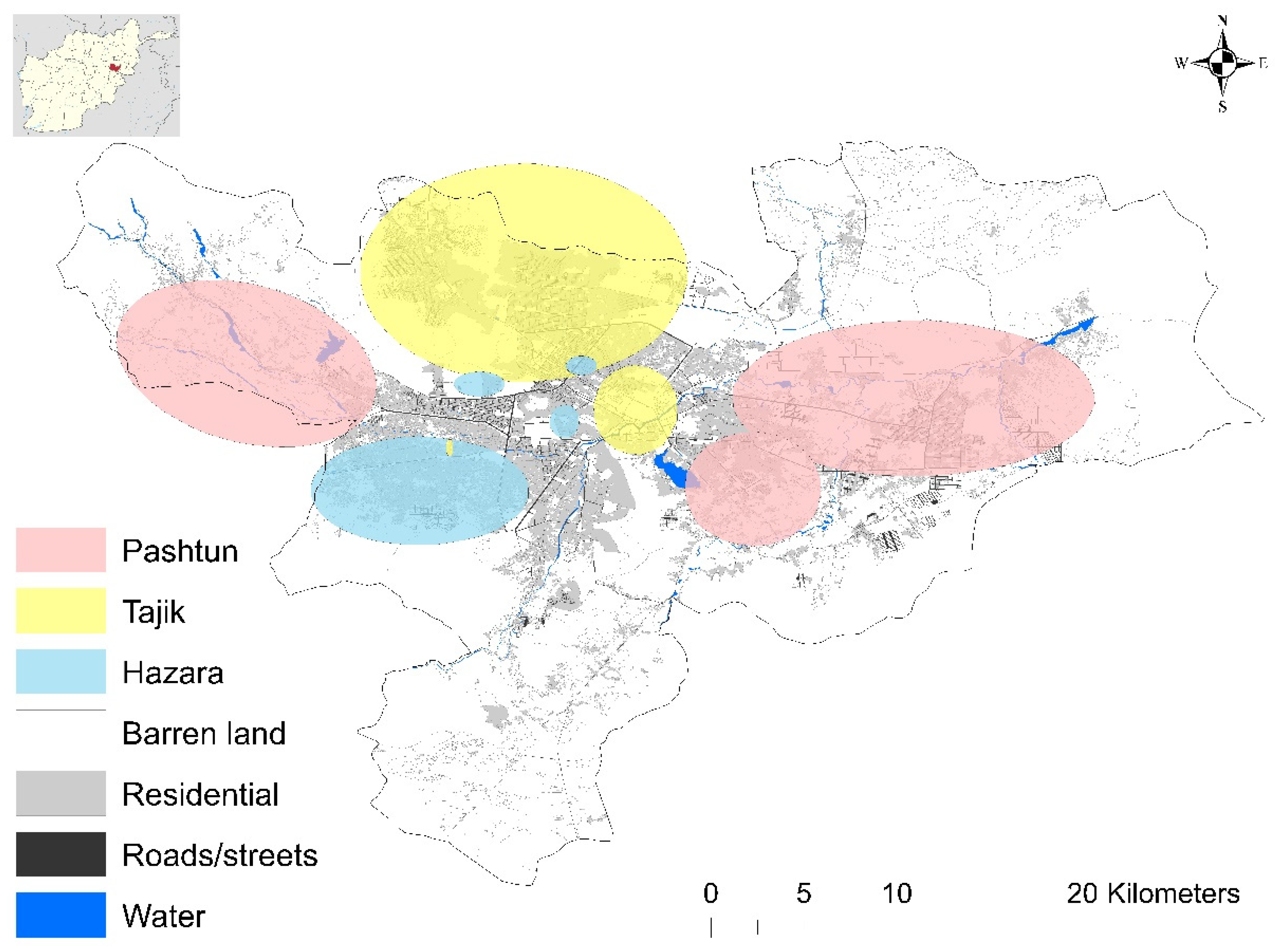

4.2. JICA Master Plan 2011

4.3. Kabul Urban Design Framework (KUDF) 2018

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scholz, D. Geteilte Stadte: Teilung Als Gegenstand Geographischer Forschung. Geogr. Rundsch. 1985, 37, 418–421. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D.S.; Denton, N.A. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, A.; Goldsmith, W.W.; Blakely, E.J. Separate Societies: Poverty and Inequality in U.S. Cities. Contemp. Sociol. 1993, 22, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollens, S.A. Urban Policy in Ethnically Polarized Societies. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 1998, 19, 187–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esman, M.J. Two Dimensions of Ethnic Politics: Defense of Homelands, Immigrant Rights. Ethn. Racial Stud. 1985, 8, 438–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.P.; Turner, E. Black–White and Hispanic–White Segregation in U.S. Counties. Prof. Geogr. 2012, 64, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.; Poulsen, M.; Forrest, J. The comparative study of ethnic residential segregation in the U.S.A., 1980–2000. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2004, 95, 550–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.G. As Long as They Don’t Move Next Door: Segregation and Racial Conflict in American Neighborhoods; Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.L. Closed Doors, Opportunities Lost: The Continuing Costs of Housing Discrimination. By John Yinger. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1995. 452p. $29.95. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1996, 90, 927–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A. (Ed.) Introduction: The Lesson of Ethnicity; Tavistock Publications: London, UK, 1974; ISBN 9781136418853. [Google Scholar]

- Glazer, N. The Universilization of Ethnicity. Encounter 1975, 44, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chinoy, E. Society; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, D. Ethno-Ideological Segregation and Metropolitan Development. Geoforum 1990, 21, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boal, F. Ethnic Residential Segregation; Herbert, D., Johnston, R., Eds.; Social Areas in Cities; John Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, D.M.; Glaeser, E.L. Are Ghettos Good or Bad? Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 827–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S.; Condran, G.A.; Denton, N.A. The Effect of Residential Segregation on Black Social and Economic Well-Being. Soc. Forces 1987, 66, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S.; Tammaru, T.; Novák, J.; Gentile, M.; Kovács, Z.; Temelová, J.; Valatka, V.; Kährik, A.; Szabó, B. Patterns of Socioeconomic Segregation in the Capital Cities of Fast-Track Reforming Postsocialist Countries. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2015, 105, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, F. (Ed.) Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Cultural Difference; George Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- United States Central Intelligence Agency. Ethnolinguistic Groups in Afghanistan; United States Central Intelligence Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Shah, I.A. Salience of Qawm, Ethnicity, in Afghanistan: An Overview. Cent. Asia J. Univ. Peshawar 2014, 75, 15–49. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, M.A. “The West Side Story”: Urban Communication and the Social Exclusion of the Hazara People in West Kabul; University of Ottawa: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmann, A. Recent Developments in Kabul’s Shar-e-Naw and Central Bazaar Districts. ASIEN 2007, 104, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sokefeld, M. (Ed.) Spaces of Conflict in Everyday Life, 1st ed.; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Issa, C. Architecture as a Symbol of National Identity in Afghanistan. Myth and Reality in the Reconstruction Process of Kabul. Geogr. Rundsch. Int. Ed. 2006, 2, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Samimi, S.A.B.; Maraschin, C. Built Heritage and Urban Spatial Configuration: The Case of Herat, Afghanistan. GeoJournal 2022, 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, S.A.B.; Ando, T.; Kawish, K. A Study on distribution of houses with domical vault roofs in Herat city—Afghanistan. J. Archit. Plan. (Trans. A.I.J.) 2018, 83, 2221–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwari, F.; Ono, H. A Study of Kabul City Urban Community Development; Proceedings of the Architectural Institute of Japan, Kyushu; Issue 61, No. 718; March 2022. Available online: https://jglobal.jst.go.jp/en/detail?JGLOBAL_ID=202202258835983047 (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Beyer, E. Building Institutions in Kabul in the 1960s. Sites, Spaces and Architectures of Development Cooperation. J. Archit. 2019, 24, 604–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobar, M.M. Afghanistan Dar Masir-i-Tarikh (Afghanistan in the Course of History); Government Press: Kabul, Afghanistan, 1967.

- Gregorian, V. The Emergence of Modern Afghanistan: Politics of Reform and Modernization, 1880–1946; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Jica, J.I. The Study for the Development of the Master Plan for the Kabul Metropolitan Area in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan: Final Report, Executive Summary; RECS International Inc.: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Calogero, P.A. Planning Kabul: The Politics of Urbanization in Afghanistan; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arez, G.J.; Dittmann, A. Kabul: Aspects of Urban Geography; Peshawar Press: Peshawar, Pakistan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki; Mudh. Kabul Urban Design Framework: Executive Summary, Citywide Framework, Dar Ul-Aman Boulevard, Massoud Boulevard, Infrastructure Systems and Implementation Strategies; Sasaki: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mushkani, R.A.; Ono, H. Urban Planning, Political System, and Public Participation in a Century of Urbanization: Kabul, Afghanistan. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2045452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, E. Competitive Coexistence: Soviet Town Planning and Housing Projects in Kabul in the 1960s. J. Archit. 2012, 17, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, G.; Gordon, C.; Miller, P. The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- JICA. Draft Kabul City Master Plan—Product of Technical Cooperation Project for Promotion of Kabul Metropolitan Area Development Sub Project for Revise the Kabul City Master Plan; JICA: Tokyo, Japan, 2011.

- French, R.A. Kyiv. 2022. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Kyiv (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Esser, D. Who Governs Kabul? Explaining Urban Politics in a Post-War Capital City; Crisis States Research Paper: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, A.J.; Kidokoro, T. Institutional Framework for Collaborative Urban Planning in Afghanistan in View of the Transferring Process of International Urban Planning Systems. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2015, 2, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Viaro, A. What Is the Use of a Master Plan for Kabul? In Development of Kabul: Reconstruction and Planning Issues; Mumtaz, B., Noschis, K., Eds.; Comportements: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2004; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Jardine, E. The Tacit Evolution of Coordination and Strategic Outcomes in Highly Fragmented Insurgencies: Evidence from the Soviet War in Afghanistan. J. Strateg. Stud. 2012, 35, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, H. The Fall of the Afghan Monarchy in 1973. Int. J. Middle East Stud. 1978, 9, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. State of Afghan Cities; Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan: Kabul, Afghanistan, 2015; Volume 1.

- Chaturvedi, V.; Kuffer, M.; Kohli, D. Analysing Urban Development Patterns in a Conflict Zone: A Case Study of Kabul. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, O.; Kajita, Y. Influences of Culture in the Built Environment; Assessing Living Convenience in Kabul City. Urban Sci. 2020, 4, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahraki, S.Z.; Hosseini, A.; Sauri, D.; Hussaini, F. Fringe More than Context: Perceived Quality of Life in Informal Settlements in a Developing Country: The Case of Kabul, Afghanistan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieprz, D. Extreme Urbanism: A View on Afghanistan, Session 1—Planning for Urban Afghanistan; The Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute at Harvard University: New Delhi, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Associates, I. Kabul Urban Design Framework; Sasaki Associates Inc.: Kabul, Afghanistan, 2021; Available online: https://www.sasaki.com/projects/kabul-urban-design-framework/ (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Lane, M.B. Public Participation in Planning: An Intellectual History. Aust. Geogr. 2005, 36, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Wiley-Blackwell: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mushkani, R.A.; Ono, H. The Role of Land Use and Vitality in Fostering Gender Equality in Urban Public Parks: The Case of Kabul City, Afghanistan. Habitat Int. 2021, 118, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, H. Kabul New City: Afghanistan’s Forgotten Development Dream. The Diplomat. 2020. Available online: https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/kabul-new-city-afghanistans-forgotten-development-dream/ (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Abdullaev, K.N. Warlordism and Development in Afghanistan. In Beyond Reconstruction in Afghanistan: Lessons from Development Experience; Montgomery, J.D., Rondinelli, D.A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Azoy, W.G. Buzkashi: Game and Power in Afohanisfan, 2nd ed.; Waveland Press: Prospect Heights, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rasanayagum, A. Afghanistan: A Modern History; Monarchy, Despotism or Democracy? In The Problems of Governance in Muslim Tradition; I.B. Taurus Co., Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Women, Business and the Law; International Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sadid, B.A. Pathology of Kabul City Design Framework. 8am. 2020. Available online: https://8am.media/eng/ (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Boal, F.W.; Douglas, J.N. Integration and Division: Geographical Perspectives on the Northern Ireland Problem; Academic Press: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Benvenisti, M. Conflicts and Contradictions, 1st ed.; Villard: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Planning in the Public Domain: Discourse and Praxis. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1989, 8, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Why Do Planning Theory? Plan. Theory 2003, 2, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forester, J. Planning in the Face of Power. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1982, 48, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.A. Regional Development Policy in New South Wales: Contemporary Needs and Options. Aust. Q. 1989, 61, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiftachel, O. Planning a Mixed Region in Israel: The Political Geography of Arab-Jewish Relations in the Galilee; Avebury: Aldershot, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, T.R. Why Minorities Rebel: A Global Analysis of Communal Mobilization and Conflict since 1945. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 1993, 14, 161–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.M. The Sociology of Ethnic Conflicts: Comparative International Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1994, 20, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Social Justice and the City; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, O. Afghanistan: Back to Tribalism or on to Lebanon? Third World Q. 1989, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Feldman, M. R&D Spillovers and the Geography of Innovation and Production. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 630–640. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, E.L. Learning in Cities. J. Urban Econ. 1999, 46, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. How Does Intergroup Contact Reduce Prejudice? Meta-Analytic Tests of Three Mediators. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | 1964 | 1970 | 1978 | 2011 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Projected Population | 0.8 million | 1.2 million | 2 million | 6.7 million | 8.8 million |

| Allowed floors | 3 | 6 | 16 | 20 | 10+ floors |

| Participants | The French-led team of 15 expatriates | A UNDP-led team from 35 countries | USSR- led the team from C.Z., G.D.R., IN, and AU | JICA-led team with Afghanistan Government | American Sasaki Company-led with Afghanistan Government |

| Main Target | Focused building microregion housing | Apart from Microregions, they also include single-family housing, green space, and industrial area | Promotes much higher residentialdensities, riverways are reserved as undeveloped aquifer rechargeareas | Formulate a regional development plan focusing on harmonized development of the Dehsabz New city and the existing Kabul city. | Developing corridors, Specially for two main boulevards |

| Women inclusion | - | - | - | - | Civic institutions like education to physical interventions to create spaces for women in the city |

| Preservation of Heritage | - | - | - | Preserved Old city and the heritage buildings | Preserved Old city and heritage buildings, Including a few parks |

| Ethnic Inclusion | - | - | - | The plan tried to connect each ethnic settlement equally to the new Kabul city to minimize segregation in future | - |

| No | Kabul City Master Plan 2011 | Kabul Urban Design Framework 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LAND USE PLAN AND LAND DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY

| Citywide Framework

|

| 2 | TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PLAN

| Corridor Districts

|

| 3 | UTILITY INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PLAN

| Infrastructure Systems

|

| 4 | PROJECT COST ESTIMATE

| Implementation strategies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarwari, F.; Ono, H. An Analysis of Urban Ethnic Inclusion of Master Plans—In the Case of Kabul City, Afghanistan. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7010003

Sarwari F, Ono H. An Analysis of Urban Ethnic Inclusion of Master Plans—In the Case of Kabul City, Afghanistan. Urban Science. 2023; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarwari, Fakhrullah, and Hiroko Ono. 2023. "An Analysis of Urban Ethnic Inclusion of Master Plans—In the Case of Kabul City, Afghanistan" Urban Science 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7010003

APA StyleSarwari, F., & Ono, H. (2023). An Analysis of Urban Ethnic Inclusion of Master Plans—In the Case of Kabul City, Afghanistan. Urban Science, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7010003