An Improved Numerical Scheme for 2D Nonlinear Time-Dependent Partial Integro-Differential Equations with Multi-Term Fractional Integral Items

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Preparations

2.1. Product Integration Rule

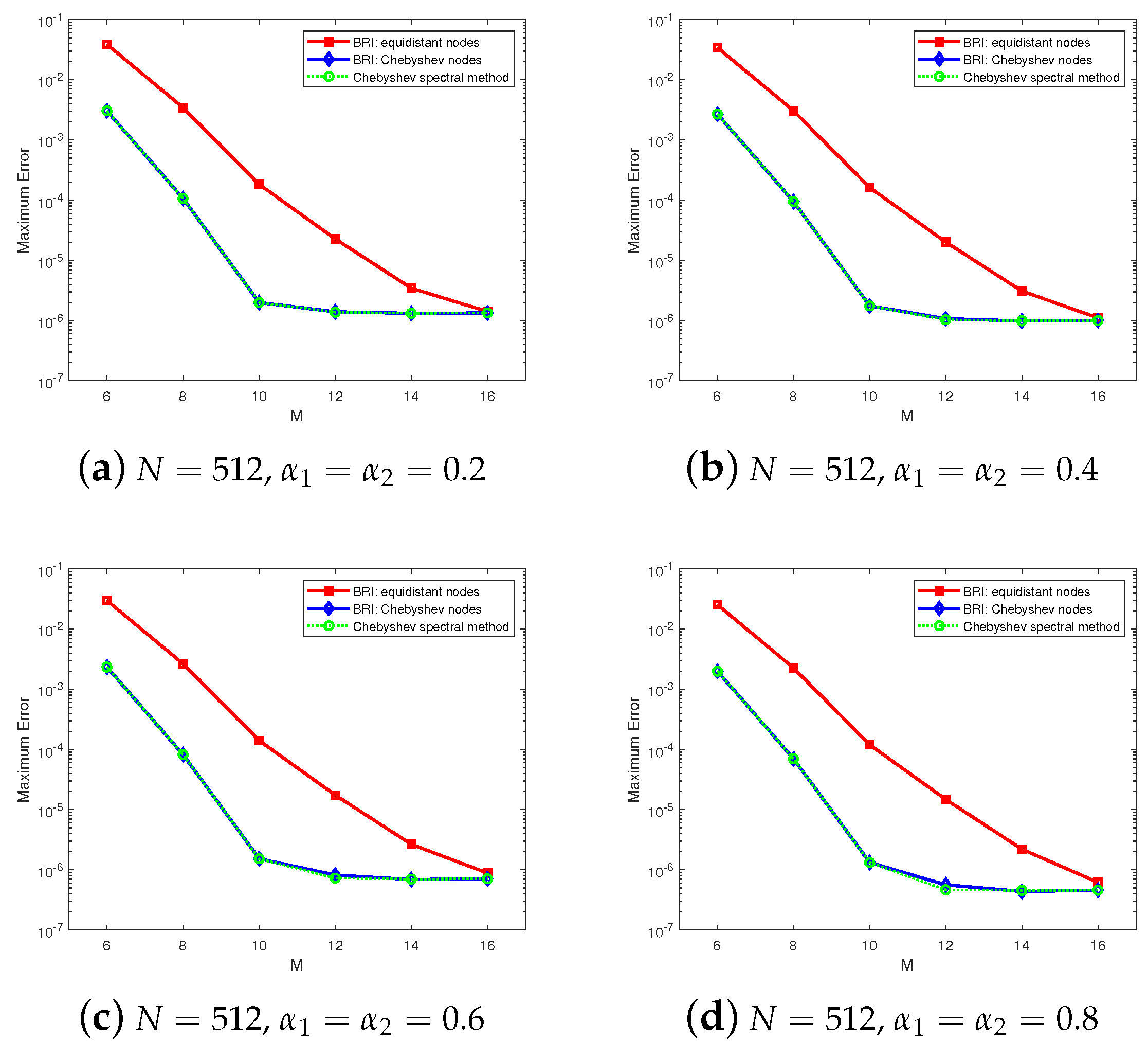

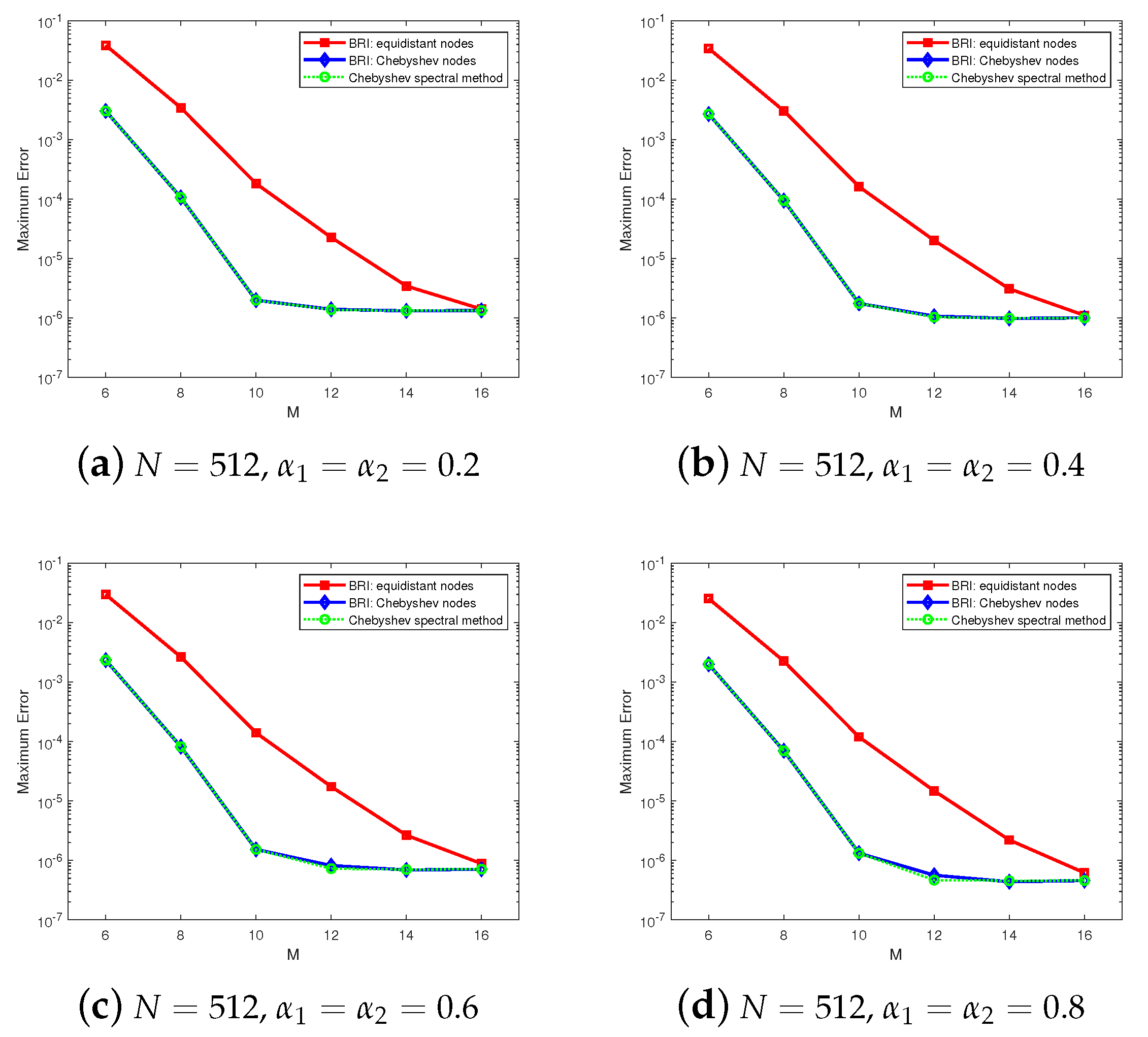

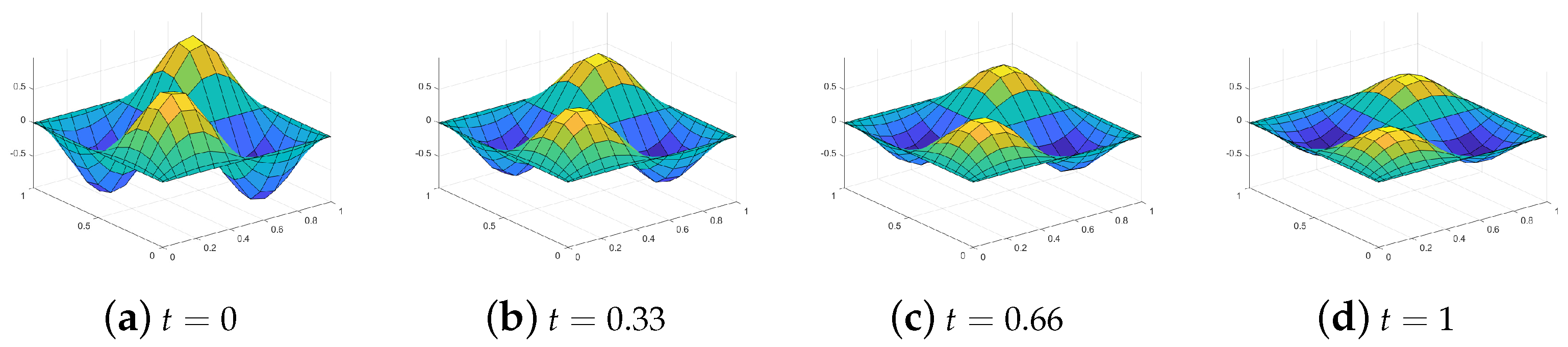

2.2. Barycentric Form of Floater–Hormann Rational Interpolation

2.3. Some Notations

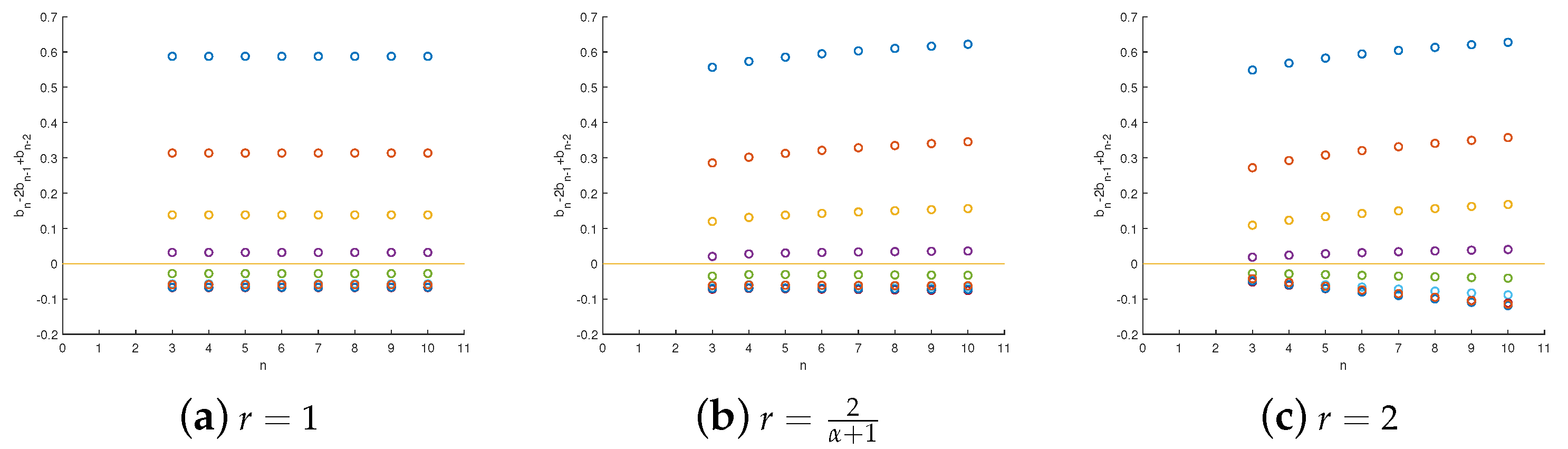

3. Temporal Discretization

3.1. Temporal Semi-Discrete Scheme

3.2. Stability and Convergence Analysis

4. Spatial Discretization

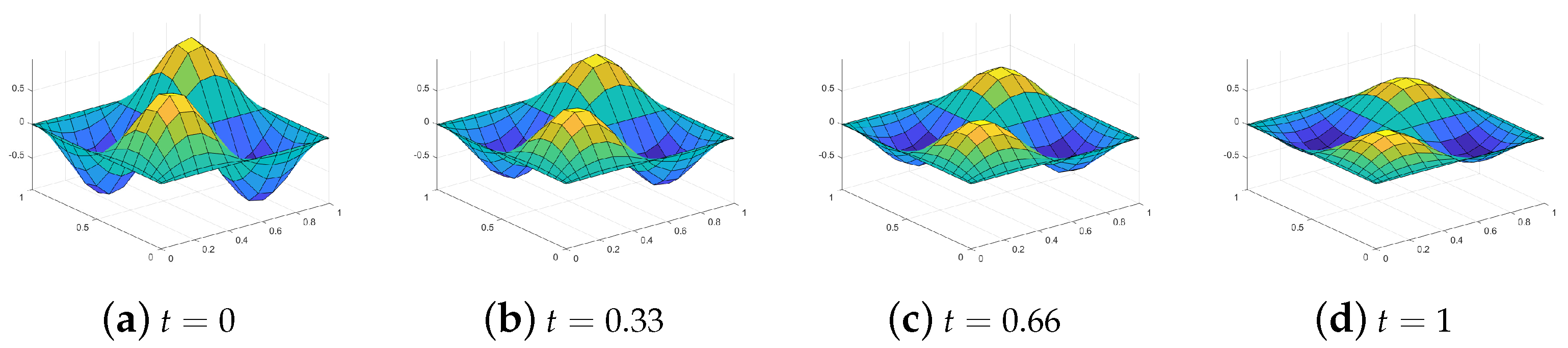

5. Numerical Experiments

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations: An Introduction to Fractional Derivatives, Fractional Differential Equations, to Methods of Their Solution and Some of Their Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bazhlekova, E. Fractional Evolution Equations in Banach Spaces. Ph.D. Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Goufo, E.; Toudjeu, I. Analysis of recent fractional evolution equations and applications. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2019, 126, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Wu, S. A parallel-in-time iterative algorithm for Volterra partial integro-differential problems with weakly singular kernel. J. Comput. Phys. 2020, 417, 109576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Gu, X.; Carpentieri, B.; Guo, J. A Bernoulli-Barycentric Rational Matrix Collocation Method With Preconditioning for a Class of Evolutionary PDEs. Numer. Linear Algebr. 2025, 32, e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Fractional Evolution Equations and Inclusions: Analysis and Control; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan, M.; Abbaszadeh, M. Spectral element technique for nonlinear fractional evolution equation, stability and convergence analysis. Appl. Numer. Math. 2017, 119, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Khatun, M.; Arefin, M.; Akbar, M. Abundant new exact solutions to the fractional nonlinear evolution equation via Riemann-LLiouville derivative. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 5183–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. New solitary wave solutions and dynamical behaviors of the nonlinear fractional Zakharov system. Qual. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2024, 23, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Li, B.; Zhou, Z. Correction of high-order BDF convolution quadrature for fractional evolution equations. SIAM J. Sci. Comput 2017, 39, A3129–A3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Lazarov, R.; Zhou, Z. Numerical methods for time-fractional evolution equations with nonsmooth data: A concise overview. Comput. Method. Appl. M. 2019, 346, 332–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, Y. A second-order accurate Crank-Nicolson finite difference method on uniform meshes for nonlinear partial integro-differential equations with weakly singular kernels. Math. Comput. Simulat. 2023, 205, 390–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, A.; Abdeljawad, T.; Baleanu, D.; Saad, K.; Al-Mdallal, Q. Numerical solutions of fractional parabolic equations with generalized Mittag-Leffler kernels. Numer. Methods Partial. Differ. Eq. 2024, 40, e22699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Baskar, S. B-spline quasi-interpolation based numerical methods for some Sobolev type equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2016, 292, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajeet, S.; Cheng, H.; Naresh, K.; Ram, J. A high order numerical method for analysis and simulation of 2D semilinear Sobolev model on polygonal meshes. Math. Comput. Simulat. 2025, 227, 241–262. [Google Scholar]

- MacCamy, R. An integro-differential equation with application in heat flow. Q. Appl. Math 1977, 35, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.; Gelhar, L. Field study of dispersion in a heterogeneous aquifer: 2. Spatial moments analysis. Water Resour. Res. 1992, 28, 3293–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilfer, R. Applications of Fractional Calculus in Physics; World Scientific: Singapore, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Gan, S.; Xu, D.; Liu, Q. A second-order BDF compact difference scheme for fractional-order Volterra equation. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2016, 93, 1140–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Xu, D. BDF ADI orthogonal spline collocation scheme for the fractional integro-differential equation with two weakly singular kernels. Comput. Math. Appl. 2019, 78, 3807–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, K. The Numerical Solution of Integral Equations of the Second Kind; Cambridge Univesity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, H. The numerical solution of weakly singular Volterra integral equations by collocation on graded meshes. Math. Comput. 1985, 45, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T. A note on collocation methods for Volterra integro-differential equations with weakly singular kernels. IMA J. Numer. Anal. 1993, 13, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Jiang, Y. On a graded mesh method for a class of weakly singular Volterra integral equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2009, 231, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Deng, W.; Min, C.; Shi, J.; Stynes, M. Error analysis of a collocation method on graded meshes for a fractional Laplacian problem. Adv. Comput. Math. 2024, 50, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrappa, R. Trapezoidal methods for fractional differential equations: Theoretical and computational aspects. Math. Comput. Simul. 2015, 110, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Qiao, L. An efficient variable step numerical method for the three-dimensional nonlinear evolution equation. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2024, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, F. A second-order finite difference method for the multi-term fourth-order integral-differential equations on graded meshes. Comput. Appl. Math. 2022, 41, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Marcos, J. A difference scheme for a nonlinear partial integro-differential equation. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1990, 27, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, D. Alternating direction implicit-Euler method for the two-dimensional fractional evolution equation. J. Comput. Phys. 2013, 236, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivanian, E.; Jafarabadi, A. An improved spectral meshless radial point interpolation for a class of time-dependent fractional integral equations: 2D fractional evolution equation. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2017, 325, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Yao, L. Numerical approximation of time fractional partial integro-differential equation based on compact finite difference scheme. Chaos Soliton. Fract. 2022, 161, 112395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T. A finite difference scheme for partial integro-differential equations with a weakly singular kernel. Appl. Numer. Math. 1993, 11, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xu, D.; Zhou, J. A second-order accurate numerical method with graded meshes for an evolution equation with a weakly singular kernel. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2019, 356, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wu, H. Error Estimates of Crank-Nicolson-Type Difference Schemes for the Subdiffusion Equation. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2011, 49, 2302–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floater, M.; Hormann, K. Barycentric rational interpolation with no poles and high rates of approximation. Numer. Math. 2007, 107, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weideman, J.; Reddy, S. A MATLAB differentiation matrix suite. ACM T. Math. Softw. 2000, 26, 465–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrut, J.; Floater, M.; Klein, G. Convergence rates of derivatives of a family of barycentric rational interpolants. Appl. Numer. Math. 2011, 61, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkaman, S.; Heydari, M.; Loghmani, G. A combination of the quasilinearization method and linear barycentric rational interpolation to solve nonlinear multi-dimensional Volterra integral equations. Math. Comput. Simul. 2023, 208, 366–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, I.; Thomme, V. Time Discretization of an Integro-Differential Equation of Parabolic Type. SIAM J. Numer. Anal 1986, 23, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Nikan, O.; Avazzadeh, Z. A localized meshless technique for solving 2D nonlinear integro-differential equation with multi-term kernels. Appl. Numer. Math. 2023, 183, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Guo, J.; Qiu, W. Time two-grid algorithm based on finite difference method for two-dimensional nonlinear fractional evolution equations. Appl. Numer. Math. 2020, 152, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 2.50 | - | 1.28 | - | 8.23 | - | 5.13 | - |

| 128 | 1.10 | 1.19 | 3.47 | 1.88 | 2.11 | 1.97 | 1.28 | 2.02 |

| 256 | 4.81 | 1.19 | 9.34 | 1.89 | 5.38 | 1.97 | 3.14 | 2.01 |

| 512 | 2.11 | 1.19 | 2.50 | 1.92 | 1.37 | 1.98 | 2.10 | 0.58 |

| N | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 4.16 | - | 8.35 | - | 5.14 | - | 4.57 | - |

| 128 | 1.50 | 1.47 | 2.30 | 1.86 | 1.32 | 1.96 | 1.15 | 2.00 |

| 256 | 5.40 | 1.48 | 6.28 | 1.87 | 3.36 | 1.97 | 2.85 | 2.01 |

| 512 | 1.94 | 1.48 | 1.70 | 1.88 | 8.49 | 1.99 | 2.77 | 0.04 |

| N | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 5.09 | - | 3.16 | - | 2.68 | - | 2.98 | - |

| 128 | 1.52 | 1.74 | 8.49 | 1.90 | 6.84 | 1.97 | 7.44 | 2.00 |

| 256 | 4.53 | 1.75 | 2.28 | 1.90 | 1.72 | 1.99 | 1.84 | 2.01 |

| 512 | 1.34 | 1.75 | 6.09 | 1.91 | 4.19 | 2.04 | 4.56 | −1.30 |

| N | CPU(s) | CPU(s) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0.2, 0.5) | 64 | 4.89 | - | 1.76 | 5.33 | - | 2.03 |

| 128 | 1.26 | 1.96 | 3.44 | 2.68 | 0.99 | 3.70 | |

| 256 | 3.22 | 1.97 | 6.98 | 1.35 | 1.00 | 7.76 | |

| 512 | 8.15 | 1.98 | 14.49 | 6.45 | 1.00 | 15.37 | |

| (0.2, 0.8) | 64 | 2.45 | - | 1.70 | 6.06 | - | 1.75 |

| 128 | 6.31 | 1.96 | 3.43 | 3.04 | 0.99 | 3.46 | |

| 256 | 1.60 | 1.98 | 7.37 | 1.53 | 1.00 | 7.31 | |

| 512 | 3.93 | 2.03 | 14.59 | 7.64 | 1.00 | 15.00 | |

| (0.5, 0.8) | 64 | 2.65 | - | 1.72 | 6.36 | - | 1.99 |

| 128 | 6.77 | 1.97 | 3.44 | 3.20 | 0.99 | 4.01 | |

| 256 | 1.71 | 1.99 | 7.02 | 1.60 | 1.00 | 8.79 | |

| 512 | 4.15 | 2.04 | 14.60 | 8.02 | 1.00 | 14.78 |

| N | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 2.50 | - | 1.28 | - | 8.20 | - | 5.10 | - |

| 128 | 1.10 | 1.19 | 3.46 | 1.88 | 2.10 | 1.97 | 1.26 | 2.02 |

| 256 | 4.81 | 1.19 | 9.32 | 1.89 | 5.36 | 1.97 | 3.12 | 2.01 |

| 512 | 2.10 | 1.19 | 2.50 | 1.90 | 3.64 | 0.55 | 7.01 | −1.17 |

| N | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 4.15 | - | 8.30 | - | 5.09 | - | 4.56 | - |

| 128 | 1.50 | 1.47 | 2.29 | 1.86 | 1.31 | 1.96 | 1.14 | 2.00 |

| 256 | 5.39 | 1.48 | 6.25 | 1.87 | 3.33 | 1.97 | 2.85 | 2.01 |

| 512 | 1.93 | 1.48 | 1.70 | 1.88 | 8.43 | 1.98 | 8.51 | −1.58 |

| N | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 5.05 | - | 3.12 | - | 2.65 | - | 2.98 | - |

| 128 | 1.51 | 1.74 | 8.40 | 1.89 | 6.76 | 1.97 | 7.43 | 2.00 |

| 256 | 4.50 | 1.75 | 2.26 | 1.89 | 1.70 | 1.99 | 2.34 | 1.67 |

| 512 | 1.34 | 1.75 | 6.05 | 1.90 | 4.15 | 2.04 | 8.52 | −1.87 |

| N | CPU(s) | CPU(s) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0.2, 0.5) | 64 | 4.85 | - | 2.00 | 5.27 | - | 1.95 |

| 128 | 1.25 | 1.96 | 3.84 | 2.66 | 0.99 | 4.02 | |

| 256 | 3.20 | 1.97 | 7.71 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 7.69 | |

| 512 | 8.10 | 1.98 | 15.69 | 6.67 | 1.00 | 15.79 | |

| (0.2, 0.8) | 64 | 2.43 | - | 1.78 | 6.00 | - | 1.92 |

| 128 | 6.24 | 1.96 | 3.60 | 3.01 | 0.99 | 3.78 | |

| 256 | 1.59 | 1.98 | 8.42 | 1.51 | 1.00 | 7.84 | |

| 512 | 3.89 | 2.03 | 15.62 | 7.56 | 1.00 | 15.73 | |

| (0.5, 0.8) | 64 | 2.62 | - | 2.21 | 6.30 | - | 1.82 |

| 128 | 6.70 | 1.97 | 4.08 | 3.16 | 0.99 | 3.67 | |

| 256 | 1.69 | 1.99 | 7.63 | 1.59 | 1.00 | 7.68 | |

| 512 | 4.11 | 2.04 | 15.53 | 7.94 | 1.00 | 15.48 |

| N | CPU(s) | CPU(s) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0.2, 0.5) | 64 | 4.57 | - | 0.08 | 1.59 | - | 0.10 |

| 128 | 1.13 | 2.01 | 0.19 | 8.05 | 0.98 | 0.23 | |

| 256 | 2.79 | 2.02 | 0.33 | 4.05 | 0.99 | 0.34 | |

| 512 | 6.63 | 2.07 | 0.77 | 2.03 | 0.99 | 0.80 | |

| (0.2, 0.8) | 64 | 4.28 | - | 0.09 | 1.92 | - | 0.79 |

| 128 | 1.06 | 2.01 | 0.18 | 9.73 | 0.98 | 0.16 | |

| 256 | 2.63 | 2.02 | 0.34 | 4.89 | 0.99 | 0.34 | |

| 512 | 6.24 | 2.07 | 0.76 | 2.45 | 1.00 | 0.77 | |

| (0.5, 0.8) | 64 | 5.37 | - | 0.08 | 3.66 | - | 0.86 |

| 128 | 1.34 | 2.00 | 0.17 | 1.85 | 0.99 | 0.17 | |

| 256 | 3.31 | 2.02 | 0.34 | 9.27 | 0.99 | 0.33 | |

| 512 | 7.89 | 2.07 | 0.78 | 4.65 | 1.00 | 0.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ouyang, F.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y. An Improved Numerical Scheme for 2D Nonlinear Time-Dependent Partial Integro-Differential Equations with Multi-Term Fractional Integral Items. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030167

Ouyang F, Liu H, Ma Y. An Improved Numerical Scheme for 2D Nonlinear Time-Dependent Partial Integro-Differential Equations with Multi-Term Fractional Integral Items. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(3):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030167

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuyang, Fan, Hongyan Liu, and Yanying Ma. 2025. "An Improved Numerical Scheme for 2D Nonlinear Time-Dependent Partial Integro-Differential Equations with Multi-Term Fractional Integral Items" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 3: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030167

APA StyleOuyang, F., Liu, H., & Ma, Y. (2025). An Improved Numerical Scheme for 2D Nonlinear Time-Dependent Partial Integro-Differential Equations with Multi-Term Fractional Integral Items. Fractal and Fractional, 9(3), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030167