Relationship between Decision-Making Styles and Leadership Styles of Portuguese Fire Officers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

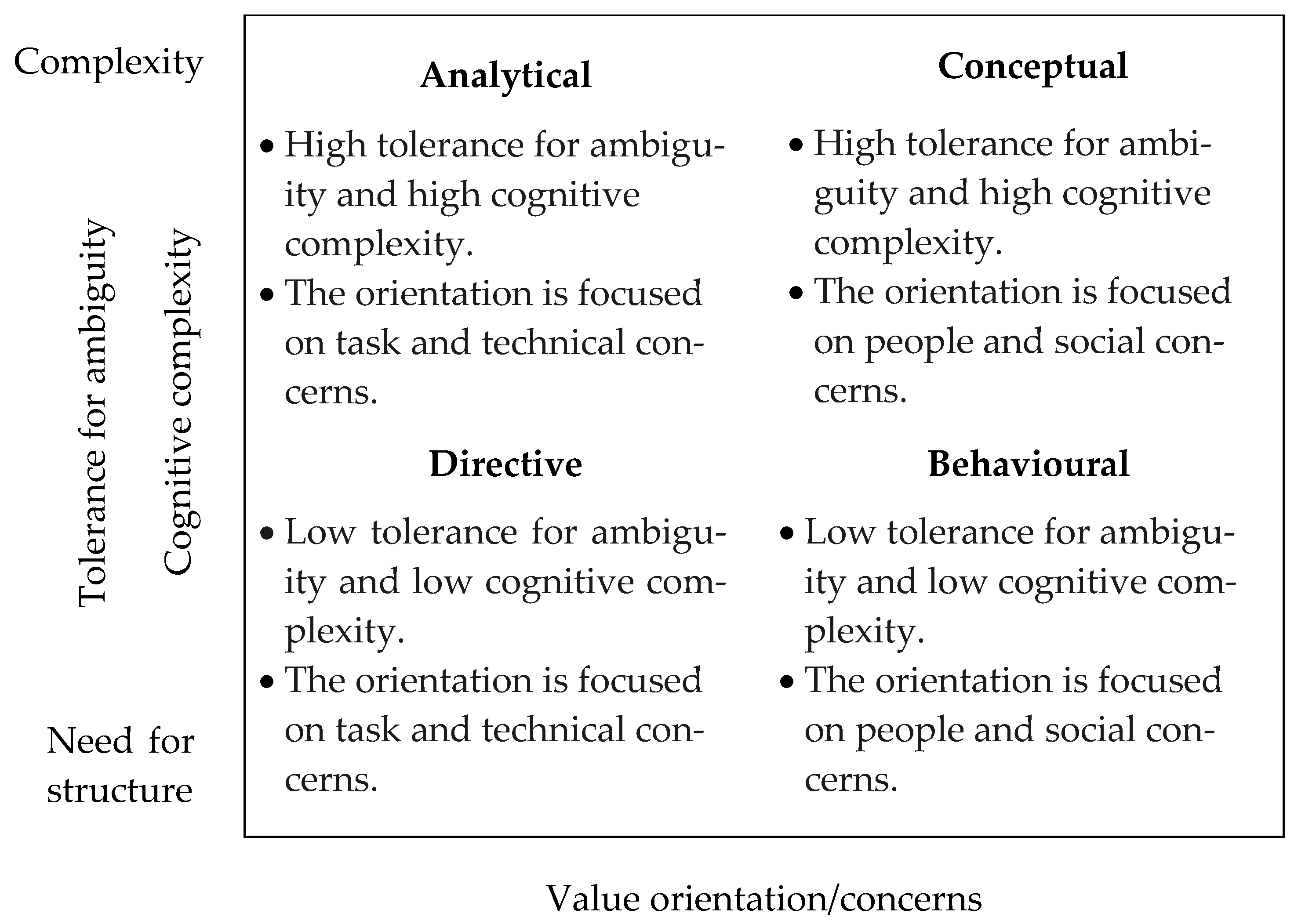

1.1. Decision-Making Styles

1.2. Leadership Styles

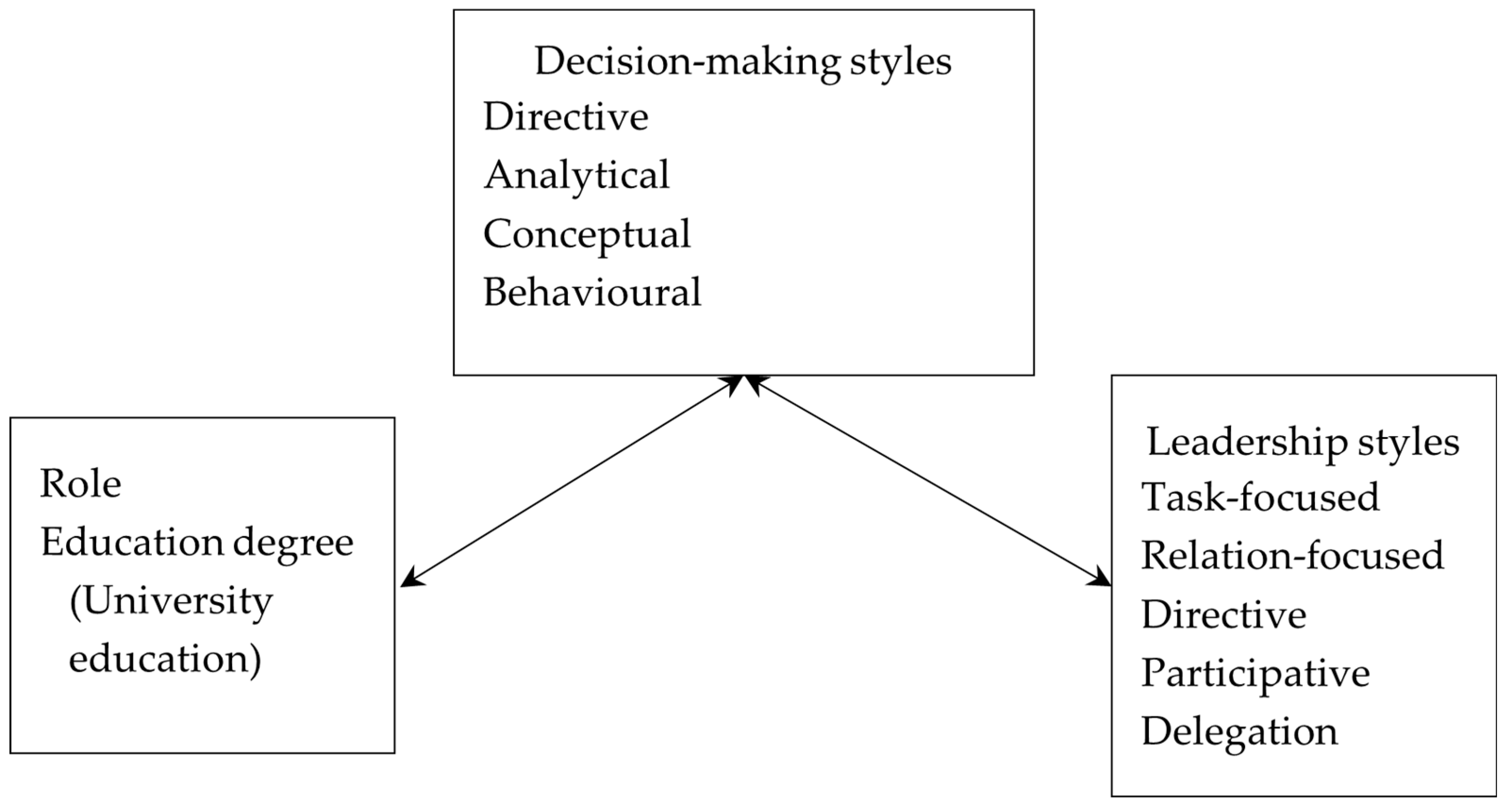

1.3. Previous Research on the Relationship between Decision-Making Styles, Leadership Styles, and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.2. Samples

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Useem, M.; Cook, J.R.; Sutton, L. Developing leaders for decision making under stress: Wildland firefighters in the South Canyon Fire and its aftermath. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2005, 4, 461–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, V.; Elia, M.; Lovreglio, R.; Correia, F.; Tedim, F. The 2017 extreme wildfires events in Portugal through the perceptions of volunteer and professional firefighters. Fire 2023, 6, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assembleia da República Portuguesa; Comissão Técnica Independente. Relatório—Análise e Apuramento dos Factos Relativos aos Incêndios que Ocorreram em Pedrogão Grande, Castanheira de Pera, Ansião, Alvaiázere, Figueiró dos Vinhos, Arganil, Góis, Penela, Pampilhosa da Serra, Oleiros e Sertã, Entre 17 e 24 de Junho de 2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.parlamento.pt/Documents/2017/Outubro/Relat%C3%B3rioCTI_VF%20.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Cunha, M.P.; Clegg, S.; Rego, A.; Giustiniano, L.; Abrantes, A.C.M.; Miner, A.S.; Simpson, A.V. Myopia during emergency improvisation: Lessons from a catastrophic wildfire. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 2019–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziani, A.; Tihay-Felicelli, V.; Santoni, P.; Perez-Ramirez, Y.; Morandi, F.; Pieri, A.; Mell, W. Effect of wind turbulences on the burning of a rockrose hedge. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2024, 150, 111036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, R.; Kaiser, R.B. What we know about leadership. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2005, 9, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Schatzel, A.; Moneta, G.B.; Kramer, S.J. Leader behavior and the work environment for creativity: Perceived leader support. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.A. Leadership in Organizations, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, C.; Lee, Y.H.; Chen, W.J. The effect of servant leadership on customer value co-creation: A cross-level analysis of key mediating roles. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Q.; Lin, M.; Wu, X. The trickle-down effect of servant leadership on frontline employee service behaviors and perfor-mance: A multilevel study of Chinese hotels. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, M.R.; Sipe, L. Service-leadership competencies for hospitality and tourism management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.J.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, M.J. How does a servant leader fuel the service fire? A multilevel model of servant leadership, individual self-identity, group competition climate, and customer service performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Liao, C.; Meuser, J.D. Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A.; Oke, A. Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: A cross-level investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, S.K.; George, W.M. Servant leadership versus transformational leadership in voluntary service organizations. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2011, 32, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specchia, M.L.; Cozzolino, M.R.; Carini, E.; Di Pilla, A.; Galletti, C.; Ricciardi, W.; Damiani, G. Leadership styles and nurses’ job satisfaction. Results of a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Liu, T.; Li, Q.; Yu, X.; Liu, Z.; Tian, S. Maintaining the working state of firefighters by utilizing self-concept clarity as a resource. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamy, N.J.W.; Swamy, D.R. Leadership styles. Adv. Manag. 2014, 7, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rouco, J.C. Modelo de Gestão de Desenvolvimento de Competências de Liderança. Ph.D. Thesis, Lusíada University, Lisbon, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G.A. Leadership in Organizations, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ejimabo, N. The influence of decision making in organizational leadership and management activities. J. Entrep. Organ. Manag. 2015, 4, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, V.; Heinemann, L.; Peifer, C.; Aust, F.; Holtz, M. Risky decision making due to goal conflicts in firefighting—Debriefing as a countermeasure to enhance safety behavior. Safety 2022, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Simon, H.A. Organizations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H. Administrative Behavior, 3rd ed.; McMillian: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, A.J.; Boulgarides, J.D.; McGrath, M.R. Managerial Decision Making; Science Research Associates Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, J.S. Smart Choices; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Appelt, K.C.; Milch, K.F.; Handgraaf, M.J.J.; Weber, E.U. The decision making individual differences inventory and guidelines for the study of individual differences in judgment and decision-making research. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2011, 6, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Schwall, A. Individual differences and decision making: What we know and where we go from here. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ravlin, E.C.; Meglino, B.M. Effect of values on perception and decision making: A study of alternative work values measures. J. Appl. Psychol. 1987, 72, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alker, H.N.; Rao, V.R.; Hughes, G.D. Value consistent and expedient decision making. Am. Psychol. Assoc. Proceeding 1972, 7, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, A.J.; Mason, R.O. Managing with Style: A Guide to Understand, Assessing, and Improving Decision Making, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Palmiero, M.; Norib, R.; Piccardic, L.; D’Amicod, S. Divergent thinking: The role of decision-making Styles. Creat. Res. J. 2020, 32, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Hasnain, N.; Venkatesan, M. Decision making in relation to personality types and cognitive styles of business students. IUP J. Manag. Res. 2012, XI, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, K.; Shih, S.; Mohammed, S. The Development and validation of the rational and intuitive decision styles scale. J. Pers. Assess. 2016, 98, 523–535. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, J.A. Intuition in managers: Are intuitive managers more effective? J. Manag. Psychol. 2000, 15, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunholm, P. Decision-making style: Habit, style or both? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, R.S.; Brooks, M.E. Individual differences in decision-making skill and style. In Judgment and Decision Making at Work; Highhouse, S., Dalai, R., Salas, E., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 80–101. [Google Scholar]

- Leykin, Y.; DeRubeis, R.J. Decision-making styles and depressive symptomatology: Development of the decision styles questionnaire. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2010, 5, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, M.J.; Svensson, K.; Amato, R.P.; Pate, L.E. A human information-processing approach to strategic change: Al-tering managerial decision styles. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1996, 26, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, D.P.; Sadler-Smith, E. An examination of the general decision making style questionnaire in two UK samples. J. Manag. Psychol. 2005, 20, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, M.J.; Brousseau, K.E.; Hunsaker, P.L. The Dynamic Decision Maker; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, A.J.; Boulgarides, J.D. The decision maker. In Managerial Decision Making: A Guide to Successful Business Decisions; Rowe, A.J., Boulgarides, J.D., Eds.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, B. Liderança Militar; Academia Militar Editora: Lisbon, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, F.E. A contingency model of leadership effectiveness. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1964, 1, 149–190. [Google Scholar]

- Gaziel, H. School-based management as a factor in school effectiveness. Int. Rev. Educ. 1998, 44, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Valenzi, E.; Farrow, D.; Solomon, R. Management styles associated with organizational, task, personal, and interpersonal contingencies. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K.; Lippit, R.; White, R.K. Patterns of aggressive behavior in artificially created social climate. J. Soc. Psyvhol. 1939, 10, 271–299. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Bass and Stodgill’s Handbook of Leadership, 3rd ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, P.L.; Wiedsma, A.F.M. Participative management. In Personnel Psychology. Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology; Drenth, P.J.D., Thoerry, H., de Wolff, C.J., Eds.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1998; Volume 3, pp. 297–324. [Google Scholar]

- Yammarino, F.J.; Naughton, T.J. Individualezed and group-based views of participation in decision making. Group Organ. Manag. 1992, 17, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smylie, M.A.; Lazarus, V.; Brownlee-Conyers, J. Instrumental outcomes of school-based participative decision making. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1996, 18, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudayyel, O.; Fredericks, T.K.; Butt, S.E.; Shaar, A. An investigation of management’s commitment to construction safety. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.; King, N. Innovation in organizations. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Cooper, C.L., Robertson, I.T., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1993; Volume 8, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Oshagbemi, T. Age influence on the leadership styles and behavior of managers. Empl. Relat. 2004, 26, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.C.; Roe, R.A.; Taillieu, T. Trust within teams: The relation with performance effectiveness. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegl, M.; Weinkauf, K.; Gemuenden, H.G. Interteam coordination, project commitment, and teamwork in multiteam R&D projects: A longitudinal study. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk, A.S.; Easton, J.Q.; Kerbow, D.; Rollow, S.G.; Sebbring, P.A. A View from the Elementary Schools: The State of Chicago School Reform; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sagie, A.; Zaidman, N.; Amicahi-Hamburger, Y.; Te’eni, D.; Schwartz, D.G. An empirical assessement of the loose-tight leadership model: Quantitative and qualitative analyses. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahai, S.S.; Sosik, J.J.; Avolio, B.J. Effects of participative and directive leadership in electronic groups. Group Organ. Manag. 2004, 29, 67–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xirasagar, S. Transformational, transactional among physician and laissez-faire leadership among physician executives. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2008, 22, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avolio, B.J. Full Range of Leaderhip Development; SAGE Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, F.E. Leader Attitudes and Group Effectiveness; Illinois Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, R.; Mouton, J. The Managerial Grid: The Key to Leadership Excellence; Gulf Publishing Co: Houston, TX, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Hamphill, J.K.; Coons, A.E. Development of leader behavior description questionnaire. In Leader Behavior: Its Description and Measurement; Stogdill, R.M., Coons, A.E., Eds.; The Ohio State University, Bureau of Business Research: Columbus, OH, USA, 1957; pp. 6–38. [Google Scholar]

- Catwrite, D.; Zander, A. Group Dynamics: Research and Theory; Row Peterson: Evanston: Row Peters, MO, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. The Human Organization: Its Management and Value; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. The Bass Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research and Managerial Applications, 4th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J. Wisdom, Intelligence, and Creativity Synthesized; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea, A.; Flin, R. Site managers and safety leadership in offshore oil and gas industry. Saf. Sci. 2001, 37, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penley, L.E.; Hawkins, B. Studying interpersonal communication in organizations: A leadership application. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, R.E.; Bakker-Pieper, A.; Oostenveld, W. Leadership = communication? The relations of leader’s communication styles with leadership styles, knowledge sharing and leadership outcomes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Decision-making style: The development and assessment of a new measure. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1995, 55, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliusson, E.A.; Karlsson, N.; Garling, T. weighing the past and the future in decision making. Eur. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2005, 17, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, L.E.; Bowen, D.D. The Great Writing in Management and Organizational Behavior; Random House Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhevnikov, M. Cognitive styles in the context of modern psychology: Toward an integrated framework of cognitive style. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacini, R.; Epstein, S. The relation of rational and experiential information processing styles to personality, basic beliefs, and the ratio-bias phenomenon. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzanwanne, F.C. Influence of age and gender on decision-making models and leadership styles of non-profit executives in Texas, USA. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2016, 24, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariri, H.; Monypenny, R.; Prideaux, M. Leadership styles and decision-making styles in an Indonesian school context. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2014, 34, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, P.H.; Kao, H. Taiwanese executives’ leadership styles and their preferred decision-making models used in mainland China. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2007, 10, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Tatum, B.C.; Eberlin, R.; Kottraba, C.; Bradberry, T. Leadership, decision making, and organizational justice. Manag. Decis. 2003, 41, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Remenova, K.; Jankelova, N.; Prochazkova, K. Relationship between path-goal leadership behavior and decision-making styles according to personal and working parameters. AD ALTA J. Interdiscip. Res. 2018, 8, 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- Azeska, A.; Starc, J.; Kevereski, L. Styles of decision making and management and dimensions of personality of school principals. Int. J. Cogn. Res. Sci. Eng. Educ. 2017, 5, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Leadership Style | Summary Description |

|---|---|---|

| Lewin, Lippit, and White’s Leadership Styles | Autocratic | The leader has complete power over their team members. The leader makes all the decisions, and the team members are expected to follow orders and to execute them without question. |

| Democratic | The leader involves team members in the decision-making process. Often the leader may still make the final decision, but input from team members is encouraged to reach a decision. | |

| Laissez-faire | The leader delegates decision-making authority to their team members and allows them to work largely on their own. | |

| House’s Path–Goal Model | Directive | The leader provides guidelines, lets team members know what is expected of them, sets performance standards for them, and controls behavior when performance standards are not met. He makes judicious use of rewards and disciplinary action. |

| Supportive | The leader is friendly towards team members and displays personal concern for their needs, welfare, and well-being. | |

| Participative | The leader believes in group decision-making and shares information with team members. He consults his team members on important decisions related to work, task goals, and paths to resolve goals. | |

| Achievement-oriented | The leader sets challenging goals and encourages team members to reach their peak performance. The leader believes that team members are responsible enough to accomplish challenging goals. | |

| Vroom–Yetton–Jago Decision-making Model of Leadership | Autocratic (AI) | The leader makes the decision by himself using existing information without any communication with the team members. |

| Autocratic (AII) | The leader consults with team members to obtain information but makes the decision by himself or herself without informing the group. | |

| Consultive (CI) | The leader consults the team members to obtain their opinions about the situation, but he or she makes the decision for themselves. | |

| Consultive (CII) | The leader consults the team members, seeking opinions and suggestions, but he or she makes the decision for himself or herself. In this type of leadership style, the leader is open to suggestions and ideas. | |

| Collaborative | The leader shares the decision-making process with the team members. He or she supports the team in making the decision and finding an answer that everyone agrees on. |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 Role | 2 Education | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Role | 1.92 | 0.88 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2. Education degree | 1.37 | 0.48 | 0.17 ** | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 3. Directive decision-making | 81.87 | 19.97 | 0.04 | −0.12 * | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4. Analytical decision-making | 91.15 | 19.43 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.70 ** | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5. Conceptual decision-making | 75.63 | 21.68 | 0.11 * | −0.08 | 0.64 ** | 0.70 ** | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6. Behavioral decision-making | 84.34 | 22.46 | 0.10 | −0.19 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.66 ** | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| 7. Task-focused leadership | 4.34 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.12 * | 0.06 | 0.09 | 1 | - | - | - |

| 8. Relation-focused leadership | 4.41 | 0.52 | −0.02 | 0.11 * | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.13 * | 0.57 ** | 1 | - | - |

| 9. Directive leadership style | 2.05 | 0.73 | −0.15 ** | −0.08 | 0.9 | 0.07 | 0.3 | −0.12 * | −0.13 * | −0.19 ** | 1 | - |

| 10. Participative leadership style | 4.21 | 0.58 | 0.09 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.11 * | 0.21 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.46 ** | −0.35 ** | 1 |

| 11. Delegation leadership style | 3.23 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.09 | −0.11* | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.21 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.04 | 0.24 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rouco, C.; Marques-Quinteiro, P.; Reis, V.; Duarte, I. Relationship between Decision-Making Styles and Leadership Styles of Portuguese Fire Officers. Fire 2024, 7, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7060196

Rouco C, Marques-Quinteiro P, Reis V, Duarte I. Relationship between Decision-Making Styles and Leadership Styles of Portuguese Fire Officers. Fire. 2024; 7(6):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7060196

Chicago/Turabian StyleRouco, Carlos, Pedro Marques-Quinteiro, Vítor Reis, and Isabel Duarte. 2024. "Relationship between Decision-Making Styles and Leadership Styles of Portuguese Fire Officers" Fire 7, no. 6: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7060196

APA StyleRouco, C., Marques-Quinteiro, P., Reis, V., & Duarte, I. (2024). Relationship between Decision-Making Styles and Leadership Styles of Portuguese Fire Officers. Fire, 7(6), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7060196