Abstract

Socioeconomic status (SES) has an unrecognized influence on behavioral risk factors as well as public health strategies related to sleep health disparities. In addition to that, objectively measuring SES’ influence on sleep health is challenging. A systematic review of polysomnography (PSG) studies investigating the relation between SES and sleep health disparities is worthy of interest and holds potential for future studies and recommendations. A literature search in databases was conducted following Prisma guidelines. Search strategy identified seven studies fitting within the inclusion criteria. They were all cross-sectional studies with only adults. Except for one study conducted in India, all of these studies took place in western countries. Overall emerging trends are: (1) low SES with its indicators (income, education, occupation and employment) are negatively associated with PSG parameters and (2) environmental factors (outside noise, room temperature and health worries); sex/gender and BMI were the main moderators of the relation between socioeconomic indicators and the variation of sleep recording with PSG. Socioeconomic inequalities in sleep health can be measured objectively. It will be worthy to examine the SES of participants and patients before they undergo PSG investigation. PSG studies should always collect socioeconomic data to discover important connections between SES and PSG. It will be interesting to compare PSG data of people from different SES in longitudinal studies and analyze the intensity of variations through time.

1. Introduction

Sleep is an ensemble of recurrent biophysical processes that may be disturbed by a wide range of biological, psychological and external factors [1,2]. Among multiple stressors affecting sleep health, there is the individual’s socioeconomic status which is also associated to health disparities, as was previously reported for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Socioeconomic status (SES) is a latent concept of an individual’s economic and socioecological situation [3,4,5,6]. SES is a complex assessment of a socio-ideological and theoretical construct measured in a variety of ways usually taking into account several indicators such as employment, income, education, occupation and social position [3,4,5,6].

The majority of studies investigating sleep disturbances use self-reported instruments such as the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), while very few studies in sleep research and health disparities have used objective measurement like actigraphy and polysomnography as an assessment tool [7,8]. Polysomnography involves the recording of several variables such as the electrical activity of the brain via electroencephalography, muscle activity via electromyogram and eyeball activity via electrooculogram [9]. Polysomnography also monitors sleep stages and cycles to identify if, why and when sleep patterns are disrupted [9,10]. In the context of sleep-wakefulness disorders and the majority of sleep disturbances, it is also a test of choice for both diagnostic and monitoring purposes [9,10] with parameters such as sleep efficiency and sleep continuity being measured.

An extensive screening of empirical literature revealed that no systematic review on the relation between socioeconomic status (SES), sleep health and its clinical measurement with polysomnography has been previously conducted. The goals of this systematic review are to (1) analyze how sleep health disparities are measured with polysomnography in the general population; and (2) suggest improvement for clinical practice.

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of Studies

Seven studies [8,11,12,13,14,15,16] were identified and included in the final selection, all cross-sectional (Table 1). Three studies [9,10,12] were performed in the USA, two studies [8,16] performed in Switzerland, one study [13] in India and one study [15] in Brazil. The participants were all adults from the general population representing a global sample size of 7638 people. The smaller sample size was 128 [14] and the biggest was 3391 [8]. Participants’ age ranged from 18 years [14] to 81 years old [8,16]. The most used socioeconomic indicators were education in five studies [9,10,12,14,15], income (annual, household and financial strain) in three studies [9,10,13], occupation and occupational position in two studies [8,16], composite score/perceived SES in two studies [11,13] and employment in one study [15].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies investigating the association between socioeconomic disparities in sleep health and polysomnography.

2.2. Polysomnography, Socioeconomic Indicators and Sleep Health

Sleep parameters measured with PSG in these studies are sleep duration [9,10,12], sleep latency [9,10,12,14], sleep efficiency [9,10,12,14], WASO [9,10,12], sleep architecture [9,10,12], stage shifts [8], sleep continuity [12] and total sleep time [8]. The duration of PSG recording ranged from one [8,13,15,16] to three nights [12]. Findings showed that lower SES was associated with longer sleep latency [11], more WASO [11], lower sleep efficiency and higher stage shifts in PSG [8]. Individuals with lower childhood SES spent more time in Stage 2 sleep and less time in SWS than participants from higher childhood SES backgrounds independently of current SES [14]. Financial strain was a significant correlate of poorer subjective sleep quality and PSG-assessed sleep continuity [12]. Men with a low educational level or occupational position were more likely to suffer from poor sleep quality, short sleep duration and insomnia [8]. In addition, men with a low occupational position were also more likely to have long sleep latency [8]. Women with a low educational level were more likely to have long sleep latency and short sleep duration [8]. Women with a low occupational position were also more likely to have longer sleep latency and short sleep duration in addition of excessive daytime sleepiness [8].

2.3. Interactions and Moderators of Polysomnography Recording

Environmental factors (outside noise, room temperature and health worries) and negative effects were statistical mediators of the relationship between SES and PSQI scores [11]. Women from low childhood SES backgrounds had longer sleep latency than women from the high childhood SES group [14]. One study found that SES affects OSA risk differentially for males and females, with low income acting as a moderator in the relationship between SES and individual’s sleep [15]. Finally, one study reported that the association between home PSG measures of OSA and SES was mediated by BMI [16].

3. Discussion

3.1. Summary of Findings

Preliminary findings showed that all seven studies were all cross sectional, conducted on adults and performed in western countries except for one Indian study. Overall trends emerging are: (1) low SES with its indicators (income, education, occupation and employment) are negatively associated with PSG parameters and (2) environmental factors (outside noise, room temperature and health worries), sex/gender and BMI were the main moderators of the relation between socioeconomic indicators and the variation of sleep recording with PSG. OSA seems more of a mediating factor for sleep quality because OSA is more prevalent in low SES populations.

3.2. Relation with Current Knowledge

Over time, SES has been established as an important determinant of health but also as a mechanism for social inequalities between groups of individuals [17,18,19,20]. Recently, studies have revealed profound implications of SES for various social inequalities related to sleep disturbances [21,22,23]. However, we know very little about the role played by SES in the development and severity of sleep health disparities regardless of how these disparities are assessed. This review provided additional information on the impact of socioeconomic indicators on objective sleep measurement. PSG parameters are associated to a variation of global SES as well as variations of individual socioeconomic indicators. The direction of this association is similar to what has been previously reported with subjective assessment of sleep health disparities: People with low SES reported more sleep disturbances regardless of their age which is known as an important sleep modifier. Another important remark is the fact that all studies included in this review were performed in developed countries: three studies were performed in the USA, two studies were performed in Switzerland, one study in India and one study in Brazil. More studies performed in developing countries with members of the general population are necessary to draw the big picture of the currently studied relationship.

3.3. Improvements for Clinical Practice

There are many studies on SES sleep that have used self-reported questionnaires [24,25,26,27,28] and objective/validated tests [21,29,30,31,32] without any emerging consensus on this relation, adding to the great heterogeneity of SES measures for which there are no clear recommendations [33,34]. This contributes to the methodological difficulty of quantifying the association between SES and sleep health, which explains the lack of meta-analysis and the scarcity of systematic reviews on the subject for adults as well as the pediatric population (children and adolescents). The present study provides evidence that PSG can help identify individual differences in sleep health among people with or without a sleep disorder diagnosis confirmed by a physician or a sleep specialist. The following suggestions may improve future investigations:

PSG studies should always collect socioeconomic data to discover important connections between SES and PSG. The concept of “sleep health” is new in sleep research and public health. It includes several domains of sleep components such as sleep quality, sleep schedule and sleep disturbances. Sleep health is the global approach of sleep with its determinants, risk factors and implications for public health and different levels of policies. It would be important to analyze the SES of participants and patients before they undergo PSG investigation. Sleep can be altered by SES indicators and it would be interesting to compare PSG data of people from different SES in longitudinal studies and analyze the intensity of variations through time.

Promote use of PSG and actigraphy in SES research. It is easier and more conventional to use validated questionnaires or self-reported items to investigate health disparities; however, PSG as well as actigraphy provide very useful and accurate details, including sleep continuity or WASO, that can objectively indicate sleep disorders or sleep health disparities with more accuracy than subjective assessments [7]. More basic training and advanced lectures related to PSG and actigraphy should be provided to students as well as researchers with interest in sleep, regardless of their background or their expertise. A joint effort of academic communities and private industries can help provide PSG accessibility with affordable prices. A tool too expensive is not used by targeted individuals and is not profitable for the manufacturer.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Literature Search

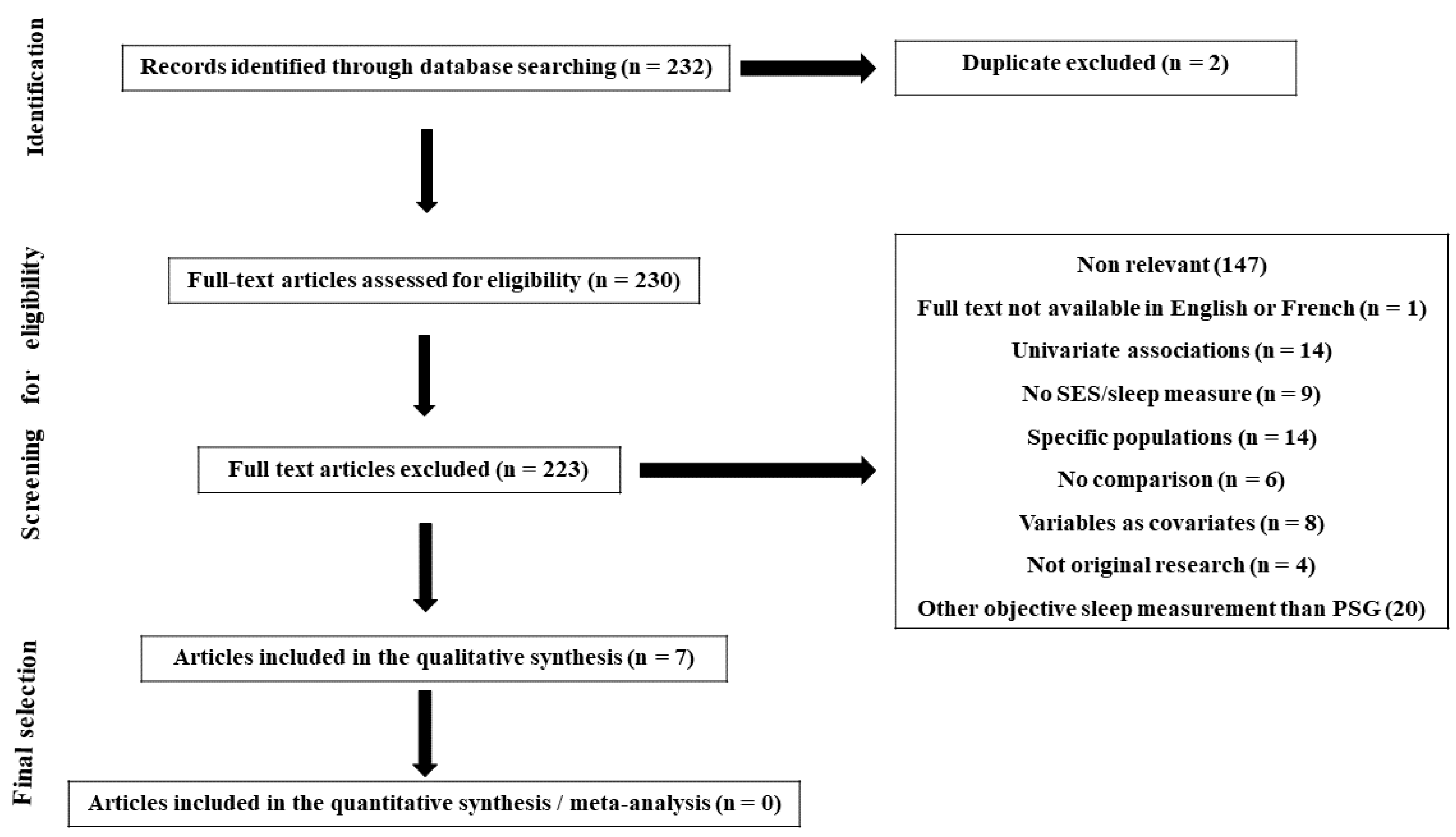

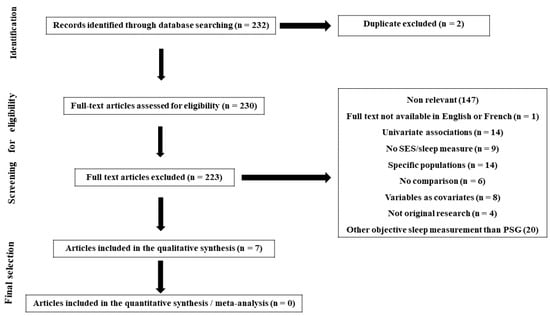

Relevant citations for this review were identified by searching the databases PubMed/Medline and Google scholar between January 2000 and April 2021. A combination of search terms was used: “socioeconomic”, “socioeconomic status”, “socio-economic”, “social position”, “social class”, “socioeconomic position”, “sleep”, “sleep disorders”, “sleep disturbances”, “sleep complains”, “polysomnography”, “wake after sleep onset”, “time in bed *”, “sleep efficiency”, “sleep duration”, “sleep quality”, “sleep diary *” and “sleep fragmentation *”. All included articles were identified on the basis of relevance to the association between SES and polysomnography parameters following the PRISMA guidelines (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prisma flowchart of study selection process: the relationship between SES and sleep health disparities measured by PSG.

4.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Observational studies were defined as of any design (cross-sectional, retrospective or longitudinal) that evaluated humans of any age, gender or race/ethnicity from the general population. The article had to include an objective measure of SES, such as education, income, assets, occupation, employment status and composite index, as well as perceived SES, self-reported by participants. Proxy measures of SES (neighborhood SES or area deprivation indices) were also included when individual data was not available. For studies examining children or adolescents, perceived family SES measures such as parental education, parental profession or household income were used instead. The investigation also needed to include a polysomnography-based measure of sleep and potential moderators such as AHI (apnea–hypopnea index). Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) They were interventional trials, reviews or meta-analyses, case series or case reports and/or did not present original research, (2) they were not written in English or French, (3) the full text was not accessible, (4) authors/researchers recruited participants that already presented specific conditions at baseline (for example individual with cancer, shift-workers, children with cerebral palsy, etc.), (5) they did not provide statistical significance in cases where either SES or sleep were evaluated as covariates or mediators and (6) researchers used actigraphy instead of polysomnography.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author reports no conflict of interest.

References

- Everly, G.S.; Lating, J.M. Sleep and Stress. In A Clinical Guide to the Treatment of the Human Stress Response; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achermann, P.; Borbély, A.A. Chapter 36—Sleep Homeostasis and Models of Sleep Regulation. In Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, 6th ed.; Kryger, M., Roth, T., Dement, W.C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 377–387.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, M.P.; Breckenkamp, J.; Blettner, M.; Schlehofer, B.; Berg-Beckhoff, G. Association between socioeconomic factors and sleep quality in an urban population-based sample in Germany. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, S.C.; Subramanian, S.V.; Piccolo, R.; Yang, M.; Yaggi, H.K.; Bliwise, D.L.; Araujo, A.B. Geographic variations in sleep duration: A multilevel analysis from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, J.A.; Batterham, P.J.; Glozier, N.; Christensen, H. The influence of job stress, social support and health status on intermittent and chronic sleep disturbance: An 8-year longitudinal analysis. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haba-Rubio, J.; Marti-Soler, H.; Tobback, N.; Andries, D.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Waeber, G.; Vollenweider, P.; von Gunten, A.; Preisig, M.; Castelao, E.; et al. Sleep characteristics and cognitive impairment in the general population: The HypnoLaus study. Neurology 2017, 88, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etindele Sosso, F.A.; Holmes, S.D.; Weinstein, A.A. Influence of socioeconomic status on objective sleep measurement: A systematic review and meta-analysis of actigraphy studies. Sleep Health 2021, 7, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringhini, S.; Haba-Rubio, J.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Waeber, G.; Preisig, M.; Guessous, I.; Bovet, P.; Vollenweider, P.; Tafti, M.; Heinzer, R. Association of socioeconomic status with sleep disturbances in the Swiss population-based CoLaus study. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirshkowitz, M. Polysomnography Challenges. Sleep Med. Clin. 2016, 11, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauderdale, D.S.; Knutson, K.L.; Yan, L.L.; Rathouz, P.J.; Hulley, S.B.; Sidney, S.; Liu, K. Objectively measured sleep characteristics among early-middle-aged adults: The CARDIA study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 164, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezick, E.J.; Matthews, K.A.; Hall, M.; Strollo, P.J., Jr.; Buysse, D.J.; Kamarck, T.W.; Owens, J.F.; Reis, S.E. Influence of race and socioeconomic status on sleep: Pittsburgh SleepSCORE project. Psychosom. Med. 2008, 70, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.H.; Matthews, K.A.; Kravitz, H.M.; Gold, E.B.; Buysse, D.J.; Bromberger, J.T.; Owens, J.F.; Sowers, M. Race and financial strain are independent correlates of sleep in midlife women: The SWAN sleep study. Sleep 2009, 32, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, E.V.; Kadhiravan, T.; Mishra, H.K.; Sreenivas, V.; Handa, K.K.; Sinha, S.; Sharma, S.K. Prevalence and risk factors of obstructive sleep apnea among middle-aged urban Indians: A community-based study. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomfohr, L.M.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Dimsdale, J.E. Childhood socioeconomic status and race are associated with adult sleep. Behav. Sleep Med. 2010, 8, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tufik, S.; Santos-Silva, R.; Taddei, J.A.; Bittencourt, L.R. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in the Sao Paulo Epidemiologic Sleep Study. Sleep Med. 2010, 11, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, D.; Haba-Rubio, J.; Carmeli, C.; Vollenweider, P.; Heinzer, R.; Stringhini, S. Social inequalities in sleep-disordered breathing: Evidence from the CoLaus|HypnoLaus study. J. Sleep Res. 2019, 28, e12799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etindele-Sosso, F.A. Insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness, anxiety, depression and socioeconomic status among customer service employees in Canada. Sleep Sci. 2020, 13, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etindele Sosso, F.A.; Matos, E. Socioeconomic disparities in obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review of empirical research. Sleep Breath. 2021, 25, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, D.; Sosso, F.A.E.; Khoury, T.; Surani, S.R. Sleep Disturbances Are Mediators Between Socioeconomic Status and Health: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 20, 480–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Perez, L.J.; Gonzalez-Cardenas, N.; Surani, S.; Etindele Sosso, F.A.; Surani, S.R. Socioeconomic Status in Pregnant Women and Sleep Quality During Pregnancy. Cureus 2019, 11, e6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doane, L.D.; Breitenstein, R.S.; Beekman, C.; Clifford, S.; Smith, T.J.; Lemery-Chalfant, K. Early Life Socioeconomic Disparities in Children’s Sleep: The Mediating Role of the Current Home Environment. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, S.S.; Takeuchi, D.T. Social determinants of inadequate sleep in US children and adolescents. Public Health 2016, 138, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrin, D.C.; McGrath, J.J.; Silverstein, J.E.; Drake, C. Objective and subjective socioeconomic gradients exist for sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, weekend oversleep, and daytime sleepiness in adults. Behav. Sleep Med. 2013, 11, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, W.H.; Kwon, J.H.; Eun, S.H.; Kim, G.; Han, K.; Choi, B.M. Effect of socio-economic status on sleep. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2017, 53, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speirs, K.E.; Liechty, J.M.; Wu, C.F. Sleep, but not other daily routines, mediates the association between maternal employment and BMI for preschool children. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 1590–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brug, J.; van Stralen, M.M.; Te Velde, S.J.; Chinapaw, M.J.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Lien, N.; Bere, E.; Maskini, V.; Singh, A.S.; Maes, L.; et al. Differences in weight status and energy-balance related behaviors among schoolchildren across Europe: The ENERGY-project. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, L.J.; Johnson, C.; Crosette, J.; Ramos, M.; Mindell, J.A. Prevalence of diagnosed sleep disorders in pediatric primary care practices. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e1410–e1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.E.; Lee, E.S.; Hemandez, M.; Solari, A.C. Symptoms of insomnia among adolescents in the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Sleep 2004, 27, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyanga, T.; Barnes, J.D.; Tremblay, M.S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Broyles, S.T.; Barreira, T.V.; Fogelholm, M.; Hu, G.; Maher, C.; Maia, J.; et al. No evidence for an epidemiological transition in sleep patterns among children: A 12-country study. Sleep Health 2018, 4, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, E.J.; Kelly, R.J.; Buckhalt, J.A.; El-Sheikh, M. What keeps low-SES children from sleeping well: The role of presleep worries and sleep environment. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, C.A.; Wolfson, A.R.; Sparling, M.; Azuaje, A. Family socioeconomic status and sleep patterns of young adolescents. Behav. Sleep Med. 2011, 10, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acebo, C.; Sadeh, A.; Seifer, R.; Tzischinsky, O.; Hafer, A.; Carskadon, M.A. Sleep/wake patterns derived from activity monitoring and maternal report for healthy 1- to 5-year-old children. Sleep 2005, 28, 1568–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.; Lynch, J. Health Inequalities: Measurement and Decomposition: Oakes JM, Kaufman JS., Methods in Social Epidemiology, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprint, Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Glymour, M.M.; Avendano, M.; Kawachi, I. Socioeconomic status and health. Soc. Epidemiol. 2014, 2, 17–63. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).