Abstract

Energy harvesting wireless sensor networks (EH-WSNs) appear as the fundamental backbone of research that attempts to expand the lifespan and efficiency of sensor networks positioned in resource-constrained environments. This review paper provides an in-depth examination of latest developments in this area, highlighting the important components comprising routing protocols, energy management plans, cognitive radio applications, physical layer security (PLS), and EH approaches. Across a well-ordered investigation of these features, this article clarifies the notable developments in technology, highlights recent barriers, and inquires avenues for future revolution. This article starts by furnishing a detailed analysis of different energy harvesting methodologies, incorporating solar, thermal, kinetic, and radio frequency (RF) energy, and their respective efficacy in non-identical operational circumstances. It also inspects state-of-the-art energy management techniques aimed at optimizing energy consumption and storage to guarantee network operability. Moreover, the integration of cognitive radio into EH-WSNs is acutely assessed, highlighting its capacity to improve spectrum efficiency and tackle associated technological problems. The present work investigates ground-breaking methodologies in PLS that uses energy-harvesting measures to improve the data security. In this review article, these techniques are explored with respect to classical encryption and discussed from network security points of view as well.The assessment furthers criticizes traditional routing protocols and their significance in EH-WSNs as well as the balance that has long been sought between energy efficiency and security in this space. This paper closes with the importance of continuous research to tackle existing challenges and to leverage newly available means as highlighted in this document. In order to adequately serve the increasingly changing requirements of EH-WSNs, future research will and should be geared towards incorporating AI techniques with some advanced energy storage solutions. This paper discusses the integration of novel methodologies and interdisciplinary advancements for better performance, security, and sustainability for WSNs.

1. Introduction

The development of wireless sensor networks (WSN) has revolutionized several applications like smart cities, healthcare, and environmental monitoring for real-time data acquisition []. One of the key challenges for WSNs is to operate sustainably in energy-constrained environments. The lifetime of the common battery-powered WSNs could be short, which causes higher maintenance and operation costs []. To make the system more prominent, and to achieve fully monitored wireless sensors for a long time, energy harvesting has been identified as a useful technique to harness environmental forces (e.g., sunlight, wind, vibrations, RF signal) in order to harvest an unlimited energy source into WSNs [,]. When we speak about energy harvesting (EH) for wireless sensor nodes, we not only refer to addressing the issues related to power consumption in a WSN, but introduce an additional era of self-sustainable/green networking. Research work in this area is developing as fast as possible because an energy harvesting system enables wireless sensor nodes to increase their lifetime and minimize dependence on finite energy resources []. The hybrid EH-WSNs/CR-WSNs have attracted much attention, as they not only improve network security but also increase the spectrum efficiency in wireless sensor networks. []. Despite significant advancements in EH-WSNs, a number of challenges still remain. However, these also bring us to a few of the challenges, i.e., harvested energy is variable and the requirements for the optimization of protocols for energy management as well as building strong security mechanisms to combat potential threats are significant in such kind of energy-limited environment []. Integrating EH mechanisms with cognitive and cooperative communication schemes, however, makes things even worse and calls for promising remedies to maintain continuity during different network operation levels.

EH-WSNs have gained significant attention as an essential solution for overcoming the energy constraints typically faced by traditional WSNs []. The concept behind EH-WSNs is to harness ambient energy from the environment such as solar, thermal, mechanical vibrations, or radio frequency (RF) signals to power the sensor nodes [], thereby extending their operational lifetime and reducing dependence on traditional battery sources. This advancement overcomes hurdles with applications that require infrequent battery replacement or charging, highly desirable in settings where battery replacement is impractical, such as in remote or hazardous locations. Gradually, energy harvesting technologies have matured to provide prospective applications in healthcare monitoring, smart cities, environmental sensors, industrial automation, etc. As a result, EH-WSNs are playing a vital role in scenarios that necessitate continuous operation and sustainable data gathering, thereby increasing the significance of green and energy-efficient communication systems. For example, energy harvesting can be applied to industrial control systems, robotic systems, and other domains where autonomous and energy-efficient operations are essential [,]. The optimization of energy and spectrum, two limited resources, is the common goal of EH-WSNs and cognitive radio (CR) technologies []. CR improves spectrum efficiency by identifying underutilized frequency bands and permitting their opportunistic use, thereby enabling dynamic spectrum access []. EH-WSNs also seek to maximize the use of harvested energy by adjusting sensor node operations according to power availability. The combination of these technologies creates a powerful framework for effective spectrum utilization and sustainable energy management. Furthermore, within EH-WSNs, physical layer security (PLS) is essential to guaranteeing secure communication []. Instead of depending only on computationally demanding cryptographic techniques, PLS adds an extra layer of security in energy-constrained networks, where nodes may be more susceptible to assaults, by taking advantage of the physical characteristics of wireless channels, such as noise and fading. Because PLS offers confidentiality, integrity, and authentication without putting a significant computational strain on EH-WSNs, it is a perfect fit for these networks. EH-WSNs are a reliable choice for contemporary wireless communication applications [] since they can be made more secure and operationally efficient by incorporating CR and PLS.

Sensor nodes in EH-WSNs are built to absorb and transform ambient energy from their surroundings into electrical power [,], allowing for perpetual operation. One can take advantage of solar, thermal, vibrational, and RF energy, among other energy sources. Solar EH is dependable and useful in a variety of outdoor applications and it is arguably the most studied nowadays [,]. Nevertheless, the use of ambient sources of energy such as kinetic or thermal are increasingly making it possible to support large deployment and varied sets of sensing applications. Both the processing and management of the harvested energy are mostly what drives EH-WSN research []. The amount of energy that can be harvested is often unpredictable and variable; thus, energy management solutions are needed for ensuring the best functioning of sensor nodes []. To ensure that the network continues to function even in situations wherein energy is scarce, sophisticated energy allocation algorithms [], dynamic power management strategies [], and intelligent scheduling mechanisms [] are required to balance energy use with the availability of captured energy. In addition, the appearance of CR-WSNs has refreshed our view about spectrum management and power conservation. Dynamic access to the available spectrum bands by CR-WSNs improves communication efficiency and reduces interference for sensor nodes. Nevertheless, the higher energy consumption of nodes resulting from this added functionality reinforces the importance of suitable EH solutions.

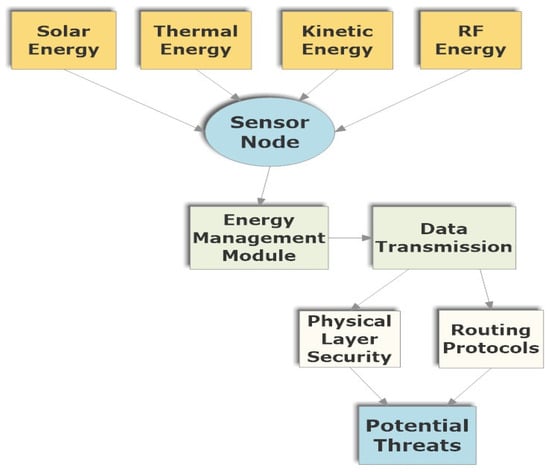

Another significant problem that EH-WSNs must address is security [], given their increasing integration within critical infrastructure and other sensitive applications. They are computationally expensive, hence not feasible in energy-limited systems like IoT. Among various secure communication approaches in EH-WSNs, PLS has been found to be more suitable with low-power consumption within this context. Without depending on upper-layer encryption algorithms, PLS uses the natural characteristics of the communication channel [], such as noise and interference, to secure data transfer. But integrating PLS into EH-WSNs comes with its own set of difficulties, especially when eavesdroppers and hostile attacks are involved []. In EH-WSNs, the development of multi-hop and multi-path routing protocols is also essential for improving network performance and resilience []. These protocols are intended to increase network longevity, reduce energy consumption, and prevent eavesdropping. Sensor nodes can cooperate to enhance data transmission and energy usage by utilizing cooperative communication strategies []. However, there are still difficulties in creating protocols that can adjust to changing network circumstances and guarantee reliable operation in a range of attack scenarios. Visualizing the underlying architecture and fundamental components of EH-WSNs is crucial, especially considering the variety and complexity of energy harvesting approaches [,]. PLS approaches use the intrinsic randomness of the wireless channel [] to shield data from interference and eavesdropping without the need for intricate encryption algorithms. For EH-WSNs, where energy efficiency is a crucial factor, PLS is hence the perfect answer. Using expensive encryption methods or typical public-key cryptography can quickly deplete the energy resources of sensor nodes in EH-WSNs [], which frequently have limited computational power and battery capacity. PLS, on the other hand, acts at the physical layer and uses the oscillations in wireless channels—such as fading, interference, and noise—to generate secure communication lines. By using techniques like artificial noise and beamforming, PLS can prevent eavesdroppers from decoding the transmitted information [], even if they have access to the same channel. Conventional PLS techniques concentrate on passive eavesdropping [], which aims to stop eavesdroppers from using the physical layer’s unpredictability to intercept communications. In this situation, methods like beamforming and artificial noise are employed to guarantee that the data being sent stay private even if an opponent is in the signal’s range. However, in addition to passive eavesdropping, more recent research has introduced the concept of proactive eavesdropping [], which involves adversaries actively engaging in network surveillance to intentionally intercept and manipulate data. This proactive approach to eavesdropping, as discussed in [,], presents a new challenge for secure communication in wireless networks, including EH-WSNs. Proactive eavesdropping is particularly concerning because the adversaries can anticipate and disrupt communication patterns, creating more sophisticated threats than passive eavesdropping alone. Incorporating proactive eavesdropping into the discussion of PLS is crucial, as it highlights the evolving security challenges that must be addressed to ensure the reliability and security of EH-WSNs. This makes PLS particularly well-suited for EH-WSNs, where energy constraints must be considered alongside security concerns. The relationship between PLS and EH is especially relevant when discussing secure communication in dynamic and energy-constrained environments []. In EH-WSNs, energy availability is often unpredictable, with nodes relying on harvested energy from sources like solar power, vibrations, or RF energy. This variability in energy harvesting can lead to sporadic availability of power, making it challenging to maintain continuous and secure communication. In a scenario wherein the energy harvested by a node is insufficient, PLS can help by reducing the amount of energy needed for security operations, as the security is inherently tied to the randomness of the channel rather than relying on energy-consuming cryptographic protocols. When nodes have access to higher levels of harvested energy, they can enhance the strength of the security measures [] (e.g., increasing power transmission to improve the signal-to-noise ratio or deploying more advanced beamforming techniques). This dynamic approach ensures that security and energy management are balanced effectively. Another critical aspect of the relationship between PLS and EH in wireless networks is the potential for cooperative security strategies []. In cooperative networks, multiple nodes collaborate to enhance both energy harvesting and communication security []. For example, nodes with abundant energy reserves can assist others by transmitting secure signals or relaying encrypted information, thus ensuring that the network remains both secure and energy-efficient. This cooperation becomes even more effective when combined with PLS, as it allows the nodes to exploit the physical layer’s inherent features [], such as spatial diversity, to provide secure communication even in the presence of eavesdroppers. In such networks, energy harvesting and PLS can work together to form a robust security framework [], where the security of data transmission is guaranteed through the cooperative efforts of energy-rich nodes, and the energy efficiency of the entire system is ensured by minimizing energy-intensive encryption techniques. By utilizing energy harvesting to balance energy consumption and using PLS to secure communication, EH-WSNs can achieve an optimal mix of security, reliability, and energy sustainability, which is critical for applications in fields like environmental monitoring, healthcare, and disaster recovery, where both energy constraints and security concerns are paramount []. The major building blocks of an EH-WSN are shown in Figure 1, which also includes the wide variety of energy sources, power managing policies, and multiple protection levels, ensuring a safe and efficient infrastructure for the network. It demonstrates that sensor nodes capture energy from several types of ambient sources, like solar, thermal, vibrational, and RF energy. It also demonstrates the relevance of network actors (e.g., PLS for secure data transmission, cognitive radio techniques for managing a spectrum, and routing protocols) to energize harvesting modules.

Figure 1.

Conceptual architecture of energy-harvesting wireless sensor networks.

The integration of energy harvesting with CR-WSNs is especially important for overcoming the constraints of standard WSNs [,]. CR-WSNs allow sensor nodes to dynamically access under-utilized spectrum bands, hence increasing spectrum efficiency. However, dynamic spectrum access adds additional energy overhead that must be carefully handled with efficient energy-harvesting strategies [,]. CR is a dynamic and adaptive communication technology designed to overcome the limitations of conventional spectrum management by enabling radios to intelligently access an underutilized spectrum []. This concept hinges on the ability of CR-enabled devices to detect and exploit unused or lightly utilized frequency bands, which are otherwise wasted in traditional fixed spectrum allocation schemes. The primary advantage of CR lies in its ability to maximize spectrum efficiency by enabling opportunistic spectrum access [], thus mitigating spectrum scarcity issues. In CR systems, users (secondary users) are allowed to access these unused bands (primary spectrum) without interfering with the primary users of the spectrum []. This dynamic and flexible spectrum management has the potential to greatly enhance the performance of wireless communication systems, especially in environments wherein spectrum resources are limited or heavily congested. In the context of (EH-WSNs), the integration of CR technology presents an opportunity to optimize both energy and spectrum usage [,], two critical resources in the operation of WSNs. When considering the integration of CR with EH-WSNs [], it is important to recognize how both systems can complement each other in various scenarios. Energy-harvesting technologies allow WSN nodes to autonomously collect ambient energy, which is typically unpredictable and variable. For example, solar-powered sensor nodes may experience fluctuations in energy harvesting due to environmental factors such as weather conditions, which can affect the available power. To ensure continuous operation under these fluctuating conditions, CR-enabled EH-WSNs can dynamically adapt their communication strategies by selecting the most appropriate spectrum bands based on the availability of both energy and spectrum. This synergy allows for more efficient and reliable communication, as CR can exploit the spectrum in real time, while EH ensures that sensor nodes have the energy required for such dynamic operations. Additionally, by using CR to access less congested frequency bands, EH-WSNs can reduce interference, which in turn minimizes the energy consumed by retransmissions, thus further optimizing energy usage.

A particularly relevant CR scenario for EH-WSNs is the opportunistic spectrum access [,], which allows sensor nodes to temporarily switch to available frequencies when the primary user is inactive. In environments wherein sensor nodes harvest energy, the ability to dynamically adjust spectrum usage according to the availability of both energy and spectrum becomes crucial [,]. For example, when the energy harvested by a sensor node is abundant, it can afford to transmit over a wider range of frequencies with higher data rates. However, during periods of low energy harvest, the system can switch to lower power modes or use spectrum bands that are more efficient for low-power transmissions. This adaptive approach not only ensures the sustainability of the network but also enhances the overall network performance by minimizing the risk of communication failure due to insufficient energy or spectrum. Furthermore, the integration of energy harvesting with CR allows for the deployment of energy-efficient and long-lasting networks [], which is particularly beneficial in remote or difficult-to-reach areas where traditional power sources and spectrum management are not feasible. CR also helps EH-WSNs in handling the security challenges posed by their energy-constrained nature []. Since these networks often operate in open, unprotected environments, they are highly vulnerable to attacks, including jamming and eavesdropping. In such scenarios, CR can be used to mitigate interference by quickly switching to alternate frequencies [], thus minimizing the impact of malicious activities. These networks can thus be deployed in a variety of critical applications, such as environmental monitoring, healthcare, and disaster response, where both security and energy efficiency are paramount.

In this paper, a comprehensive review of the cutting edge in the field of EH for WSNs is presented with an objective to provide scholars and practitioners with in-depth understanding of the existing scenario as well as future directions on this emerging subject. While its application in a WSN may appear new, the concept of EH is far from being so. This is mostly because a great number of sensors are being deployed, often too far from any maintenance center and some sort of power network, making battery replacement not feasible or unduly expensive. Conventional power sources have limited lifetime and dependability for WSNs [], which makes them less viable for many critical deployments over a long term such as infrastructure management, security systems, and environmental monitoring. These trends have driven the research towards energy harvesting and an improvement in network security to cope with increasing demands for self-sufficient and long-lasting sustainable networks. The summary of the review work is as follows. Section 1 addresses the background and motivation behind EH-WSNs, focusing on the need for energy sustainability in sensor networks and the role of EH technologies. Section 2 explores various energy-harvesting techniques, including solar, vibration, and RF energy, detailing how these methods are applied to power sensor nodes in EH-WSNs. Section 3 discusses energy management strategies, emphasizing the importance of efficient energy storage and consumption algorithms to ensure the continuous operation of EH-WSNs. Section 4 examines the application of CR in wireless sensor networks, explaining how dynamic spectrum access can optimize energy and spectrum utilization in EH-WSNs. It also explores PLS techniques, focusing on their role in protecting communication from eavesdropping in EH-WSNs while ensuring energy efficiency. Section 5 reviews routing protocols designed for EH-WSNs, highlighting strategies for managing data transmission in energy-constrained networks. Section 6 identifies the key challenges and opportunities in EH-WSNs, including energy variability, spectrum sharing, and security concerns, and explores future trends in the field. Section 7 summarizes the key findings from the review, focusing on the synergies between EH, CR, and PLS in enhancing network performance. Section 8 concludes the review, emphasizing the need for further research and innovation to address the challenges and optimize the performance of EH-WSNs for real-world applications.

2. Background and Motivation

The WSNs have revolutionized the way we sense and interact with our environment. WSNs allow for data collection from different areas, such as smart cities, health monitoring, and environmental conditions by deploying a network of small-scale battery-powered sensor nodes. Regardless of this, a significant obstruction remains because these sensor nodes lack an appropriate source of energy []. Traditional WSNs operate on battery power, which is both expensive and bad for the environment as they need frequent replacement. The major advantage of EH technologies is that they provide a continuous and perpetual power supply for sensor nodes, harvesting renewable ambient energy from the environment (e.g., solar energy, thermal energy, kinetic energy, and RF energy). This grants WSNs a longer life and less need for battery replacement, reduces price costs, and is more environmentally friendly.

- Solar Energy: This energy is derived from sunlight and the solar panels are used to convert it into electrical energy.

- Thermal Energy: Manufactured from temperature via thermoelectric generators that transform warmth electricity into electric power.

- Kinetic Energy: generated through vibrations or motion, and piezoelectric materials are employed to transmute in an electric power.

- RF Energy: RF harvesting modules are used to harvest energy from radio frequency signals.

These energy sources are combined with WSNs by linking them to the sensor nodes via an Energy Management Module [], which controls and optimizes the consumption of collected energy. This component ensures that the energy acquired is efficiently utilized for the network functionalities such as data gathering, transmission, and security. The inspiration for creating EH methods in WSNs derives from the desire to set-up self-sustaining networks that can run eternally without human participation []. By reducing trust on the standard batteries [,], EH-WSNs give a long-term solution that can assist in a wide range of applications, from environmental monitoring to industrial automation and elegant infrastructure [,,].

3. Energy Harvesting Techniques

Because EH captures ambient energy, it is essential to the sustainability of WSNs because it allows sensor nodes to function independently. This section examines different methods of EH, describing how they transform solar energy into electrical power and weighing the benefits and drawbacks of each.

3.1. Solar Energy Harvesting

Solar energy harvesting leverages sunlight to generate electrical power using photovoltaic (PV) cells [,]. These cells convert light into electricity through the photovoltaic effect. The power generated by a PV cell can be expressed as follows:

where P is the electrical power output (watts), is the efficiency of the PV cell, A is the surface area of the PV cell, G is the solar irradiance, and is the angle of incidence of sunlight on the PV cell. Solar energy is one of the most commonly used methods in energy harvesting due to its abundance and reliability. The advantages of solar energy harvesting are as follows:

- High Power Output: Solar panels can generate substantial amounts of energy, suitable for various applications.

- Mature Technology: Well-established technology with extensive research and development.

- Environmentally Friendly: Solar energy is renewable and does not produce emissions.

The limitations of solar energy harvesting are as follows:

- Intermittent Availability: Solar energy depends on weather conditions and time of day.

- Space Requirement: Efficient solar panels require adequate surface area, which might be challenging in some applications.

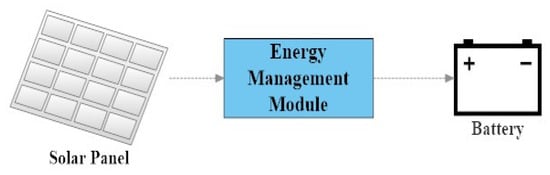

Figure 2 illustrates a typical solar energy harvesting system, including the solar panel, energy storage (battery or super-capacitor), and the sensor node.

Figure 2.

Solar energy harvesting system.

3.2. Thermal Energy Harvesting

Thermal energy harvesting converts heat gradients into electrical power using thermoelectric generators (TEGs) [,]. These generators exploit the Seebeck effect, where a temperature difference across a material generates a voltage. The electrical power generated by a TEG can be expressed as follows:

where P is the electrical power output (in watts), S is the Seebeck coefficient of the material (in volts per kelvin), is the temperature gradient across the TEG (in kelvin), is the load resistance (in ohms), and is the internal resistance of the TEG (in ohms). The advantages of thermal energy harvesting are as follows:

- Continuous Operation: Can operate as long as there is a temperature gradient, which can be constant in many environments.

- Compact Design: TEGs are generally small and can be integrated into various devices.

The limitations of thermal energy harvesting are as follows:

- Low Efficiency: TEGs typically have low conversion efficiency, making them suitable for low-power applications.

- Temperature Gradient Requirement: Requires a consistent temperature difference to generate power effectively.

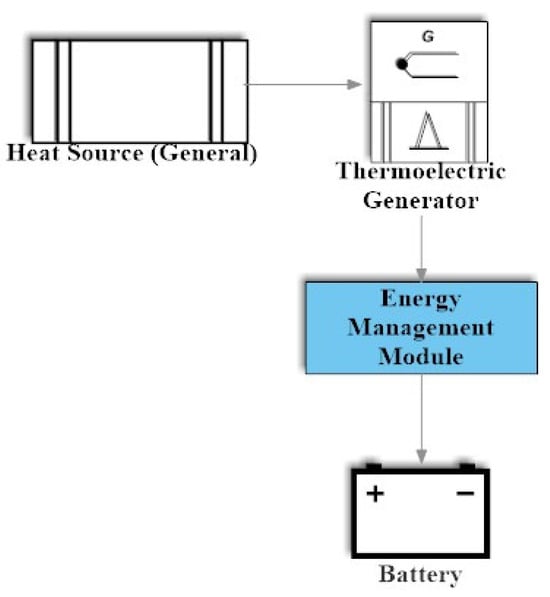

Figure 3 depicts a thermal energy harvesting setup, including the thermoelectric generator, heat source, and energy storage unit.

Figure 3.

Thermal energy harvesting system.

3.3. Kinetic Energy Harvesting

Kinetic energy harvesting captures mechanical motion, such as vibrations or movements, and converts it into electrical energy using piezoelectric materials or electromagnetic generators [,,]. This technique is particularly useful in environments with constant vibrations or movement. The power generated from vibrations can be expressed as follows:

where P is the electrical power output (in watts), m is the mass of the vibrating object (in kilograms), A is the amplitude of the vibration (in meters), is the angular frequency of the vibration (in radians per second), and Q is the quality factor of the system. The advantages of kinetic energy harvesting are as follows:

- Versatility: Can be used in various settings, including wearable devices and industrial equipment.

- Low Maintenance: Passive energy harvesting requires minimal maintenance compared to battery-powered systems.

The limitations of kinetic energy harvesting are as follows:

- Variable Power Output: Power generation depends on the intensity and frequency of mechanical motion.

- Complex Integration: Integrating kinetic energy harvesters into existing systems can be challenging.

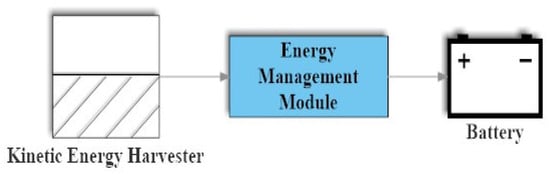

Figure 4 shows a kinetic energy harvesting system, including the piezoelectric materials or electromagnetic generator and the sensor node.

Figure 4.

Kinetic energy harvesting system.

3.4. RF Energy Harvesting

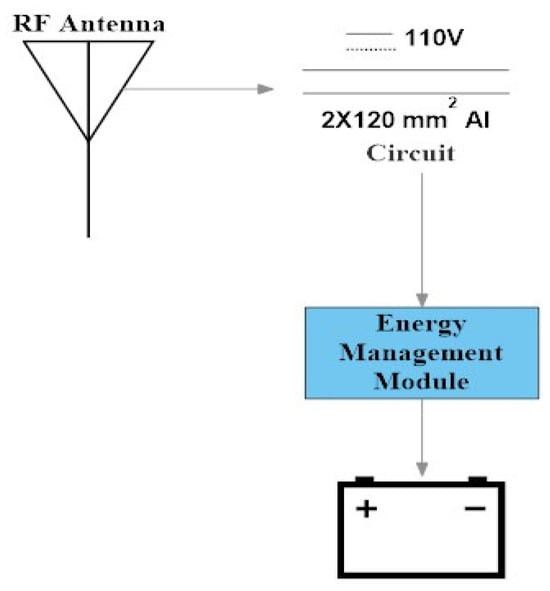

RF energy harvesting captures energy from radio frequency signals, such as those emitted by cellular towers [,,], Wi-Fi routers [,,], or other RF sources. This technique uses RF antennas and rectifiers to convert electromagnetic waves into electrical power. The power harvested from RF signals can be expressed as follows:

where P is the electrical power output (in watts), is the conversion efficiency of the rectifier, is the transmitted RF power (in watts), G is the antenna gain (dimensionless), is the wavelength of the RF signal (in meters), and d is the distance between the RF source and the antenna (in meters). The advantages of RF energy harvesting are as follows:

- Non-Intrusive: Can capture energy from existing RF sources without additional infrastructure.

- Can be deployed in various environments with prevalent RF signals.

The limitations of RF energy harvesting are as follows:

- Low Power Density: RF energy is typically low in power density, making it suitable for low-power applications.

- Distance Dependent: Efficiency decreases with increasing distance from the RF source.

Figure 5 illustrates an RF energy harvesting system, showing the RF antenna, rectifier circuit, and energy storage component.

Figure 5.

RF energy harvesting system.

4. Energy Management Strategies

Optimizing the performance and longevity of WSNs that use EH methods requires effective energy management. This section examines a number of energy management techniques, including as integration with WSNs, consumption optimization, energy storage, and management protocols.

4.1. Energy Storage Solutions

Energy storage solutions are essential for ensuring a stable power supply in WSNs []. These solutions store harvested energy and provide power during periods when energy generation is insufficient.

- Batteries: Because of their ability to store large amounts of energy, batteries can be recharged and are extensively utilized in WSN. There are several varieties of batteries, including lithium-ion, nickel-metal hydride (NiMH), and lead-acid. The positives are high energy density and known technology, while the disadvantages are limited cycle life, temperature sensitivity, and a relatively expensive cost.

- Super-capacitor: Has a high power density and the ability to deliver energy in short bursts. Greater cycle life and quicker charge/discharge rates in comparison to batteries are the benefits. The drawbacks are more expensive than standard batteries and a lower energy density.

- Hybrid System: Combines batteries and super-capacitors to maximize the benefits of both technologies. Its advantages include balancing energy and power density, which improves total system efficiency. The restrictions include design complexity and cost.

4.2. Energy Consumption Optimization

Optimizing energy consumption is critical for extending the operational life of sensor nodes [,]. Various strategies and techniques are employed to minimize energy usage during different operational phases.

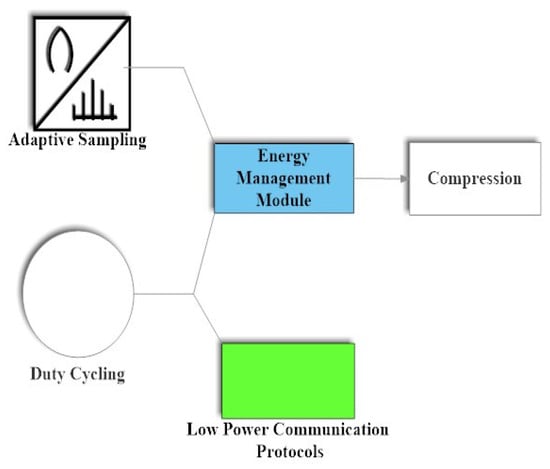

- Adaptive Sampling: Adjusts the frequency of data collection based on environmental conditions or application needs.

- Compression Techniques: Reduces the amount of data transmitted by compressing sensor data before transmission.

- Duty Cycling: Alternates between active and sleep modes to reduce energy consumption during idle periods.

- Low-Power Communication Protocols: Utilizes energy-efficient communication protocols that minimize power usage during data transmission.

- Efficient Algorithms: Implements algorithms that minimize computational complexity and energy consumption.

- Edge Computing: Processes data locally on the sensor node to reduce the amount of data transmitted and save energy.

Figure 6 illustrates various energy consumption optimization techniques, including adaptive sampling, compression, duty cycling, and low-power communication protocols.

Figure 6.

Energy consumption optimization techniques.

4.3. Energy Management Protocols

Energy management protocols are algorithms designed to effectively manage and allocate energy resources within WSNs [,]. These protocols ensure efficient energy use and prolong the network’s operational life.

4.3.1. Energy-Efficient Routing Protocols

- Objective: Optimize the path for data transmission to minimize energy consumption.

- Examples: Energy-efficient variants of routing protocols like LEACH (Low-Energy Adaptive Clustering Hierarchy) and TEEN (Threshold-sensitive Energy-Efficient Network) [,].

4.3.2. Energy Harvesting Aware Protocols

- Objective: Incorporate energy-harvesting capabilities into routing and data management strategies.

- Examples: Protocols that adjust energy consumption based on the availability of harvested energy [,,].

4.3.3. Load Balancing Protocols

- Objective: Distribute energy consumption evenly across the network to prevent early depletion of energy in specific nodes.

- Examples: Load-balancing mechanisms that dynamically adjust node roles based on energy levels [,].

4.4. Integration with Wireless Sensor Networks

Integrating energy management strategies into WSNs involves aligning energy harvesting and management techniques with the network’s operational requirements.

4.4.1. System Design Considerations

- Compatibility: Ensuring that energy harvesting components are compatible with the sensor node and network architecture [].

- Scalability: Designing energy management systems that can scale with the network size and application demands [,].

4.4.2. Implementation Challenges

- Cost: Balancing the cost of advanced energy management solutions with the benefits they provide [,].

- Complexity: Addressing the complexity of integrating diverse energy-harvesting methods and management protocols into a cohesive system [,].

5. Energy-Harvesting Applications

5.1. Cognitive Radio for Wireless Sensor Networks

Cognitive radio (CR) technology dynamically manages the usage of available spectra to improve the flexibility and efficiency of WSNs [,]. This section discusses the fundamentals of cognitive radio, its application in WSNs, spectrum sensing and management, energy-efficient spectrum usage, and associated challenges.

5.1.1. Overview of Cognitive Radio

Cognitive radio is an innovative communication technology that enables radios to automatically and dynamically access and utilize available spectrum bands [,]. The primary goals of CR are to increase spectrum utilization and reduce interference by allowing radios to adapt to their present spectrum environment. The primary characteristics of cognitive radio are the following:

- Spectrum Sensing: Detects the presence of primary users (licensed users) and identifies unused spectrum bands.

- Dynamic Spectrum Access: Allows secondary users (unlicensed users) to access spectrum bands when primary users are not active.

- Adaptive Transmission: Adjusts transmission parameters based on the spectrum environment.

5.1.2. Spectrum Sensing and Management

Finding and classifying available spectrum bands that secondary users can use is known as “spectrum sensing.” Maximizing spectrum use and avoiding interference with primary users depend on effective spectrum sensing. The essential methods are as follows:

- Energy Detection: Measures the energy of the received signal to determine the presence of primary users.

- Matched Filtering: Uses known characteristics of primary user’s signals to detect their presence.

- Cyclo-stationary Feature Detection: Exploits the periodicity of signals to detect primary users.

- Spectrum Allocation: Assigning spectrum bands to users based on their requirements and availability.

- Spectrum Sharing: Allowing multiple users to share the same spectrum band using different access strategies.

5.1.3. Energy-Efficient Spectrum Usage

In WSNs, energy efficiency is a critical concern [,]. The CR technique can result in energy savings by optimizing spectrum consumption and decreasing unwanted transmissions.

- Spectrum Optimization: By keeping away congested or under-utilized bands, it uses spectrum bands more intelligently.

- Adaptive Power Control: Modifies the transmission power based upon the observed spectrum environment in order to reserve the energy.

5.1.4. Challenges and Solutions

As cognitive radio provides notable advantages, various obstacles are necessary to address:

- Interference Management: Making sure that the secondary users (SUs) do not obstruct primary users (PUs) or other secondary users.

- Security Concerns: Keeping CR systems safe from malicious attacks and certifying steady spectrum access.

- Complexity in Implementation: It would be complex and costly to integrate the CR technology into existing WSN infrastructure.

5.2. PLS in Energy-Harvesting Networks

PLS is a security strategy that uses the physical qualities of the communication channel to improve data security, rather than depending exclusively on cryptographic approaches [,,]. This section delves into the principles of PLS, its use in EH-WSNs, a comparison with existing encryption methods, and the obstacles connected with PLS implementation. PLS uses the inherent properties of the communication medium to ensure secure transmission. In contrast to classical encryption systems, which operate with complex algorithms and key management on the basis of conventional security technologies, PLS is based on the physical properties of the channel. The basic concepts of PLS are the following:

- Secrecy Capacity: The maximum amount of information that can be safely transmitted over a communication channel.

- The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): This ratio is a comparison of the level of the desired signal to the level of background noise.

- Channel State Information (CSI): It states that knowledge of the channel conditions is crucial for optimal scheduling and allocation of radio resources.

PLS can be included into EH-WSNs to further enhance the data security when data are shifted across energy-harvesting networks [,]. Data protection and energy efficiency are the objectives of PLS integration in EH-WSNs. PLS techniques that are applied in EH-WSNs include the following:

- Energy-Harvesting-Based Security: Employing the energy-harvesting abilities of the network, in order to assist secure communication.

- Secure Data Transmission: Making sure that data are transmitted securely using PLS methods, even with less energy resources.

PLS provides a number of advantages over conventional encryption methods that include the following:

- Reduced Computational Overhead: PLS does not need complex cryptographic algorithms, bringing down the computational burden.

- Enhanced Security in Adverse Conditions: PLS can preserve security even in demanding environments with excessive levels of interference.

Table 1 portrays a difference between PLS and traditional encryption methods.

Table 1.

Comparison of PLS and traditional encryption methods.

6. Routing Protocols in EH-WSNs

In order to effectively manage data transfer in EH-WSNs, routing protocols are necessary [,]. Routing protocols in EH-WSNs must handle the particular difficulties brought forth by fluctuating network circumstances, dynamic network topologies [], and energy limitations []. The main routing protocols used in EH-WSNs are examined in this section with an emphasis on their effectiveness, energy management, and security implications. EH-WSN routing protocols are developed to maximize data transfer while preserving energy and guaranteeing dependable connection. Among the primary categories of routing protocols are the following:

- Direct Routing Protocols: Send data directly from the source to the destination without intermediate nodes.

- Hierarchical Routing Protocols: Use a tiered structure where nodes are grouped into clusters, and data are routed through cluster heads.

- Geographic Routing Protocols: Utilize the geographic location of nodes to determine the routing path.

In addition, the energy-efficient routing protocols aim to minimize energy consumption while ensuring reliable data transmission. Key strategies include:

- Energy-Aware Routing: Select routes based on the energy levels of nodes to extend the network’s lifetime.

- Load Balancing: Distribute the data transmission load evenly across the network to avoid energy depletion in specific nodes.

- Sleep Scheduling: Implement sleep–wake cycles to conserve energy by putting nodes into low-power modes when not actively transmitting data.

Furthermore, the multi-hop and multi-path routing protocols improve reliability and robustness in EH-WSNs by:

- Multi-hop Routing: Data are transmitted through multiple intermediate nodes before reaching the destination, which helps in overcoming long-distance transmission challenges.

- Multi-path Routing: Multiple paths are used for data transmission, providing redundancy and load balancing to improve reliability and fault tolerance.

Security is crucial in EH-WSNs to protect against various attacks, such as eavesdropping, data tampering, and denial of service. Key security considerations include the following:

- Data Encryption: Encrypt data during transmission to prevent unauthorized access.

- Authentication: Verify the identity of nodes to prevent malicious nodes from participating in the network.

- Secure Routing Protocols: Implement routing protocols designed to resist security threats and ensure data integrity.

7. Challenges, Opportunities, and Future Trends

We present here the major challenges EH-WSNs face and what we expect to be improved or innovated in order to overcome them, as well as some of the emerging directions in research on energy harvesting and cyber security. These ideas are important for practical EH-WSN technology and applications.

7.1. Challenges Faced by EH-WSNs

Table 2 presents the challenges faced by EH-WSNs, providing a detailed and structured summary of both the achievements and unresolved issues in this domain. Significant progress has been made in addressing key areas such as energy efficiency [,], where advancements in energy harvesting and management techniques have enabled more reliable data transmission and network functionality despite limited energy resources. Additionally, efforts to enhance compatibility and interoperability with existing technologies [] have paved the way for the smoother integration of EH-WSNs into established systems, broadening their applicability across diverse scenarios [,]. However, several challenges remain unresolved, demanding further investigation. Managing energy efficiency is still a critical issue, especially in scenarios with fluctuating energy availability and varying network demands [,]. Network scalability poses another challenge as the performance and lifetime of EH-WSNs are adversely impacted when the network grows in size [], requiring innovative resource allocation and optimization techniques. Data security, particularly in energy-constrained environments, continues to be a pressing concern, as ensuring secure transmission without overburdening the system remains a difficult balance to strike [,]. Similarly, the dynamic topologies characteristic of EH-WSNs [,] arising from changes in node availability and shifting network structures introduce complexities in maintaining consistent performance and reliability. By explicitly distinguishing the progress made and the gaps that persist, Table 2 not only highlights the evolving state of EH-WSNs but also identifies critical avenues for future research. Addressing these challenges, such as developing adaptive energy management strategies, designing lightweight security protocols, and enhancing scalability, will be essential for realizing the full potential of EH-WSNs in practical, large-scale deployments.

Table 2.

Key challenges in EH-WSNs.

7.2. Opportunities for Improvement and Innovation

The chances for enhancement and innovation in EH-WSNs are presented in Table 3. This table summarizes potential advancements and innovative approaches that could enhance the efficiency, sustainability, and performance of energy-harvesting wireless sensor networks. It highlights key areas for future research and development.

Table 3.

The opportunities for improvement and innovation.

7.3. Future Trends in Energy Harvesting and Security

7.3.1. Emerging Technologies

The emerging technologies in EH-WSNs are as follows:

- Advanced Energy-Harvesting Materials: Research into novel materials, such as nano-materials and meta-materials, has the potential to improve the efficiency and scope of energy-harvesting technology [,]. These compounds can enhance the performance of solar cells, thermoelectric generators, and other energy-harvesting systems.

- Integration of IoT and EH-WSNs: Innovation in EH is anticipated to be fueled by the expanding Internet of Things (IoT) [,]. Improved network efficiency and innovative energy management techniques are expected outcomes of integration with IoT devices.

- Smart Grids and EH-WSNs: The combination of EH-WSNs and smart grid technologies can improve energy distribution and utilization [,]. Smart grids will provide EH-WSNs more control over energy supplies, allowing them to adjust to fluctuating energy availability.

7.3.2. Innovations in Energy Management

The recent innovations in energy management include the following:

- Enhanced Energy Storage Solutions: Advanced supercapacitors and solid-state batteries are two examples of energy storage innovations that will offer more dependable and effective energy storage options for EH-WSNs [,].

- Adaptive Energy Management Systems: Future energy management systems are predicted to be more flexible and intelligent, leveraging AI and machine learning [,] to optimize energy consumption in real time based on network circumstances and energy availability.

- Blockchain for Energy Transactions: Energy transactions in EH-WSNs might be managed and verified using blockchain technology [,], guaranteeing security and openness in the distribution and consumption of energy.

7.3.3. Advances in Security Mechanisms

The recent advances in security mechanism related to EH-WSNs are the following:

- Quantum Cryptography: Quantum cryptography provides a new level of security by enforcing quantum mechanics rules during data transmission [,,]. This technology could be built into EH-WSNs to improve data security.

- Bio-Inspired Security Approaches: Investigations into bio-inspired security mechanisms—that is, security based on biological processes—may yield novel approaches to protecting EH-WSNs from cyber attacks [,].

- Adaptive Security Protocols: Future security protocols are predicted to be more adaptable, able to change their protection methods in response to real-time threat analysis and network conditions [,].

8. Summary of Key Findings

This review paper provides a complete overview of advancements in EH-WSNs. The important findings from each area are given below in table form.

8.1. Comparison of Energy-Harvesting Techniques

Each energy collecting approach has distinct advantages and limits, making it appropriate for a variety of applications [,]. The choice of energy-harvesting technology is determined by factors such as energy demand, ambient conditions, and deployment limits. Table 4 outlines the major characteristics of each technique: restrictions and solutions. The comparison of energy-harvesting techniques in Table 5 presents a summary of various energy harvesting methods, including solar, thermal, kinetic, and RF, highlighting their relative effectiveness and suitability for different applications.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of energy harvesting techniques.

Table 5.

Comparison of energy-harvesting techniques.

8.2. Energy Management Strategies

Energy management strategies in Table 6 outline various approaches to optimizing energy use and storage in WSNs, detailing methods for enhancing efficiency and extending operational lifespan.

Table 6.

Energy management strategies.

8.3. Cognitive Radio Benefits and Challenges

In this section, we list the benefits of and challenges in applying CR technology to WSNs (Table 7), as well as its influence on spectrum efficiency and network performance.

Table 7.

Cognitive radio benefits and challenges.

8.4. Physical Layer Security Techniques

Table 8 tabulates the related methods and techniques, as well as approaches that have been presented previously to ensure data transmission security in wireless sensor networks at the physical layer, shedding light on their efficiency and providing arguments (instance for some key) against safety threats.

Table 8.

Physical layer security techniques.

8.5. Routing Protocols Overview

Table 9 below shows a summary of various routing techniques used in wireless sensor networks with the key features, advantages, or limitations.

Table 9.

Routing Protocols Overview.

9. Conclusions

The energy-harvesting wireless sensor networks (EH-WSNs) belong to an important category in the scope of WSNs, and this paper extensively reviews a variety of aspects with respect to EH-WSNs, including energy harvesting (EH) techniques, energy management strategies, cognitive radio (CR) applications, physical layer security (PLS), and routing protocols. The identification of individual elements showed significant progress in the area which underlines the importance of employing EH systems other than conventional energy resources towards sustainable and efficient WSNs, especially for low-power contexts. While the industry has come a long way, major obstacles remain. It is a research direction to, for example, optimize across EH coming from multiple sources such as solar, thermal, kinetic, and RF, maximizing a balance between energy consumption and storage efficiency. Moreover, the combination of CR and WSNs appears very appealing for performance-oriented spectrum access despite plenty of technical challenges such as spectrum management and energy efficiency waiting to be addressed.

A future challenge in EH-WSNs is PLS, which provides a great opportunity to embed the security in the process of energy harvesting itself and therefore it replaces classical encryption techniques. Before PLS becomes a broad technology, more dangers and challenges are required to be addressed for the deployment of a solution. In this line, EH-WSN routing protocols need to be further developed such that they can provide proper security mechanisms against hostile attacks and cyber threats in addition to energy saving. Future work should focus on a number of key areas in order to advance EH-WSNs. Top-notch technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) can transform energy management, allowing it to change and react according to the levels of energy at every stage. Similarly, advancements in power storage technology such as hybrid powers storage systems and super capacitors might help reduce the existing constraints. Second, blockchain could be considered as a turning point in the security of EH-WSNs, realizing energy transactions and creating data integrity.

This highlights the importance of interdisciplinary work given the proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices and requirement for high-performance, long-lasting deployments. In modern time, the researchers must look towards the development of complete systems comprising energy harvesting and secure and optimal operation of networks in one scalable manner. By addressing these difficulties and capitalizing on the potential identified, future EH-WSNs will be better able to enable the development of applications in smart cities, environmental monitoring, and other areas.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Belghith, A.; Obaidat, M. Wireless sensor networks applications to smart homes and cities. In Smart Cities and Homes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Engmann, F.; Katsriku, F.A.; Abdulai, J.D.; Adu-Manu, K.S.; Banaseka, F.K. Prolonging the lifetime of wireless sensor networks: A review of current techniques. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, 2018, 8035065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.J.; Torquato, M.F.; Cameron, I.M.; Fahmy, A.A.; Sienz, J. Survey of energy harvesting technologies for wireless sensor networks. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 77493–77510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwalike, E.D.; Ibrahim, K.A.; Crawley, F.; Qin, Q.; Luk, P.; Luo, Z. Harnessing energy for wearables: A review of radio frequency energy harvesting technologies. Energies 2023, 16, 5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, D.K.; Hazra, A.; Mazumdar, N.; Amgoth, T. An efficient routing awareness based scheduling approach in energy harvesting wireless sensor networks. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 23, 17638–17647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Umer, M.; Hong, J.; Muhammad, O.; Awwad, F.A.; Ismail, E.A. Energy-Efficient and Resilient Secure Routing in Energy Harvesting Wireless Sensor Networks with Transceiver Noises: EcoSecNet Design and Analysis. J. Sensors 2024, 2024, 3570302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, O.; Jiang, H.; Muhammad, B.; Umer, M.M.; Ahtsam, N.M.; Dasno, S. A Comprehensive Review of D2D Communication in 5G and B5G Networks. LC Int. J. STEM (ISSN: 2708-7123) 2023, 4, 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Adu-Manu, K.S.; Adam, N.; Tapparello, C.; Ayatollahi, H.; Heinzelman, W. Energy-harvesting wireless sensor networks (EH-WSNs) A review. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. (TOSN) 2018, 14, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Kaur, R.; Singh, D. Energy harvesting in wireless sensor networks: A taxonomic survey. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 118–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Cai, S.; Lau, V.K. Radix-partition-based over-the-air aggregation and low-complexity state estimation for IoT systems over wireless fading channels. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2022, 70, 1464–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, C.; Ai, X.; Huang, B.; Chen, W.; Yang, G.Z. Body contact estimation of continuum robots with tension-profile sensing of actuation fibers. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 1492–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhy, A.; Joshi, S.; Bitragunta, S.; Chamola, V.; Sikdar, B. A survey of energy and spectrum harvesting technologies and protocols for next generation wireless networks. IEEE Access 2020, 9, 1737–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiropoulos, G.I.; Dobre, O.A.; Ahmed, M.H.; Baddour, K.E. Radio resource allocation techniques for efficient spectrum access in cognitive radio networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2014, 18, 824–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.N.; So-In, C.; Ha, D.B.; Sanguanpong, S.; Baig, Z.A. On secure wireless sensor networks with cooperative energy harvesting relaying. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 139212–139225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.M.; Sabyasachi, A.S. A Metaheuristic Algorithm Based Clustering Protocol for Energy Harvesting in IoT-Enabled WSN. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2024, 136, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, P. Solar energy harnessing technologies towards de-carbonization: A systematic review of processes and systems. Energies 2023, 16, 6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Qi, L.; Tairab, A.M.; Ahmed, A.; Azam, A.; Luo, D.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, J. Solar energy harvesting technologies for PV self-powered applications: A comprehensive review. Renew. Energy 2022, 188, 678–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Cheng, S.; Li, J. An efficient EH-WSN energy management mechanism. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2018, 23, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Shankaran, R.; Sheng, Q.Z.; Orgun, M.A.; Hitchens, M.; Masud, M.; Ni, W.; Mukhopadhyay, S.C.; Piran, M.J. QoS-aware energy management and node scheduling schemes for sensor network-based surveillance applications. IEEE Access 2020, 9, 3065–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Liu, M.; Yu, F.R.; Leung, V.C.; Song, M.; Zhang, Y. Resource allocation for ultra-dense networks: A survey, some research issues and challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2018, 21, 2134–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, N.; Shankar, T. A review on energy-efficient scheduling mechanisms in wireless sensor networks. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ahmed, S.; Ali, M.T.; Alothman, A.A.; Nawaz, A.; Shahzad, M.; Shah, A.A.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, M.Y.A.; Najam, Z.; Shaheen, A. EH-UWSN: Improved Cooperative Routing Scheme for UWSNs Using Energy Harvesting. J. Sensors 2020, 2020, 8888957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottarelli, M.; Epiphaniou, G.; Ismail, D.K.B.; Karadimas, P.; Al-Khateeb, H. Physical characteristics of wireless communication channels for secret key establishment: A survey of the research. Comput. Secur. 2018, 78, 454–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, M.M.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Manlu, L.; Muhammad, O. Time-slot based architecture for power beam-assisted relay techniques in CR-WSNs with transceiver hardware inadequacies. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sciences. Tech. Sci. 2023, 71, e146620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, O.; Jiang, H.; Umer, M.M.; Muhammad, B.; Ahtsam, N.M. Optimizing Power Allocation for D2D Communication with URLLC under Rician Fading Channel: A Learning-to-Optimize Approach. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Soleymani, M.; Kelouwani, S.; Amamou, A.A. Energy recovery and energy harvesting in electric and fuel cell vehicles, a review of recent advances. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 83107–83135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, M.Z.; Khalid, Z.; Shahid, R.; Tsoi, W.C.; Mishra, Y.K.; Kyaw, A.K.K.; Saeed, M.A. Advancement in indoor energy harvesting through flexible perovskite photovoltaics for self-powered IoT applications. Nano Energy 2024, 129, 109994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kinani, A.; Wang, C.X.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, W. Optical wireless communication channel measurements and models. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2018, 20, 1939–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swessi, D.; Idoudi, H. A survey on internet-of-things security: Threats and emerging countermeasures. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2022, 124, 1557–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Kumar, N.; Tekchandani, R. Physical layer security using beamforming techniques for 5G and beyond networks: A systematic review. Phys. Commun. 2022, 54, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, H.; Arslan, H. PLS-IoT enhancement against eavesdropping via spatially distributed constellation obfuscation. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2023, 12, 1508–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, H.; Lee, I. Proactive eavesdropping with jamming and eavesdropping mode selection. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2019, 18, 3726–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Ching, P. Energy efficiency for proactive eavesdropping in cooperative cognitive radio networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 13443–13457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar, A.; Yazicigil, R.T. Physical-Layer Security for Energy-Constrained Integrated Systems: Challenges and Design Perspectives. IEEE Open J. Solid-State Circuits Soc. 2023, 3, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, A.; Wang, T.; Ota, K.; Dong, M.; Liu, Y.; Cai, Z. Adaptive data and verified message disjoint security routing for gathering big data in energy harvesting networks. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2020, 135, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmed, M.; Raza, S.; Khan, F.; Ma, Y.; Khan, W.U. Beyond encryption: Exploring the potential of physical layer security in UAV networks. J. King Saud-Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W. A Study Of Innovative Technologies for Energy-Efficient Enterprise Management of Wireless Heterogeneous Networks in Collaborative Communications. Int. J. Commun. Networks Inf. Secur. 2024, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hamamreh, J.M.; Furqan, H.M.; Arslan, H. Classifications and applications of physical layer security techniques for confidentiality: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2018, 21, 1773–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Ta, H.Q.; Ho-Van, K. Reliability and Security Analysis of Energy Harvesting-Based Partial Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access Systems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 187015–187026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelakos, E.A.; Kandris, D.; Rountos, D.; Tselikis, G.; Anastasiadis, E. Energy sustainability in wireless sensor networks: An analytical survey. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2022, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, X.; Lăzăroiu, G. Spectrum sensing, clustering algorithms, and energy-harvesting technology for cognitive-radio-based internet-of-things networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 7792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Gao, H.; Zhou, C.; Duan, R.; Zhou, X. Resource allocation in cognitive radio wireless sensor networks with energy harvesting. Sensors 2019, 19, 5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, M. Energy harvesting strategies for wireless sensor networks and mobile devices: A review. Electronics 2021, 10, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldin, H.N.S.; Ghods, M.R.; Nayebipour, F.; Torshiz, M.N. A comprehensive review of energy harvesting and routing strategies for IoT sensors sustainability and communication technology. Sensors Int. 2023, 5, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, C.A.; Idakwo, M.A.; Imoize, A.L.; Adamu, T.; Sur, S.N. AI for spectrum intelligence and adaptive resource management. In Artificial Intelligence for Wireless Communication Systems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 57–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mousa, S.H.; Ismail, M.; Nordin, R.; Abdullah, N.F. Effective Wide Spectrum Sharing Techniques Relying on CR Technology toward 5G: A Survey. J. Commun. 2020, 15, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidawi, D.J.; Sadkhan, S.B. Blind spectrum sensing algorithms in CRNs: A brief overview. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Engineering Conference “Research & Innovation amid Global Pandemic” (IEC), Erbil, Iraq, 24–25 February 2021; pp. 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; Ching, P. Spectrum Sharing and Energy Cooperation in Wireless Powered Cognitive Radio Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 90th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2019-Fall), Honolulu, HI, USA, 22–25 September 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ardeshiri, G.; Vosoughi, A. On Distributed Detection in EH-WSNs With Finite-State Markov Channel and Limited Feedback. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2023, 7, 1692–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieu, T.D.; Duy, T.T.; Kim, B.S. Performance enhancement for multihop harvest-to-transmit WSNs with path-selection methods in presence of eavesdroppers and hardware noises. IEEE Sensors J. 2018, 18, 5173–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, M.H.; Kim, S.; Kuruoğlu, N. Energy harvesting techniques for wireless sensor networks/radio-frequency identification: A review. Symmetry 2019, 11, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Foroughi, J.; Peng, S.; Baughman, R.H.; Wang, Z.L.; Wang, C.H. Advanced energy harvesters and energy storage for powering wearable and implantable medical devices. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2404492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ardao, J.C.; Rodriguez-Rubio, R.F.; Suarez-Gonzalez, A.; Rodriguez-Perez, M.; Sousa-Vieira, M.E. Current trends on green wireless sensor networks. Sensors 2021, 21, 4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.U.A.; Qamar, F.; Ahmed, F.; Nguyen, Q.N.; Hassan, R. Interference management in 5G and beyond network: Requirements, challenges and future directions. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 68932–68965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathre, M.; Das, P.K. Hybrid energy harvesting for maximizing lifespan and sustainability of wireless sensor networks: A comprehensive review & proposed systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Smart Power System and Sustainable Energy (CISPSSE), Keonjhar, India, 29–31 July 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kanoun, O.; Bradai, S.; Khriji, S.; Bouattour, G.; El Houssaini, D.; Ben Ammar, M.; Naifar, S.; Bouhamed, A.; Derbel, F.; Viehweger, C. Energy-aware system design for autonomous wireless sensor nodes: A comprehensive review. Sensors 2021, 21, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengheni, A.; Didi, F.; Bambrik, I. EEM-EHWSN: Enhanced energy management scheme in energy harvesting wireless sensor networks. Wirel. Netw. 2019, 25, 3029–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokoor, F.; Shafik, W. Harvesting energy overview for sustainable wireless sensor networks. J. Smart Cities Soc. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leemput, D.; Hoebeke, J.; De Poorter, E. Integrating Battery-Less Energy Harvesting Devices in Multi-Hop Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2024, 62, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Chen, Q.; Shi, T.; Zhu, T.; Chen, K.; Li, Y. Battery-free wireless sensor networks: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 5543–5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Tiang, J.J.; Wong, S.K.; Rambe, A.H.; Adam, I.; Smida, A.; Waly, M.I.; Iqbal, A.; Abubakar, A.S.; Mohd Yasin, M.N. Harvesting systems for rf energy: Trends, challenges, techniques, and tradeoffs. Electronics 2022, 11, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, S.; Minaei, S.; MalehMirchegini, L.; Trommsdorff, M.; Shamshiri, R.R. Applications of solar PV systems in agricultural automation and robotics. In Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conversion; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 191–235. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Riba, J.R.; Moreno-Eguilaz, M.; Sanllehí, J. Application of thermoelectric generators for low-temperature-gradient energy harvesting. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouhara, H.; Żabnieńska-Góra, A.; Khordehgah, N.; Doraghi, Q.; Ahmad, L.; Norman, L.; Axcell, B.; Wrobel, L.; Dai, S. Thermoelectric generator (TEG) technologies and applications. Int. J. Thermofluids 2021, 9, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaligh, A.; Zeng, P.; Zheng, C. Kinetic energy harvesting using piezoelectric and electromagnetic technologies—State of the art. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 57, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fei, Z.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, Z.; Maeda, R. Overview of human kinetic energy harvesting and application. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 7091–7114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Qi, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Y. A novel kinetic energy harvester using vibration rectification mechanism for self-powered applications in railway. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 228, 113720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherazi, H.H.R.; Zorbas, D.; O’Flynn, B. A comprehensive survey on RF energy harvesting: Applications and performance determinants. Sensors 2022, 22, 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, H.H.; Singh, M.J.; Al-Bawri, S.S.; Ibrahim, S.K.; Islam, M.T.; Alzamil, A.; Islam, M.S. Radio frequency energy harvesting technologies: A comprehensive review on designing, methodologies, and potential applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, M.A.; Keshavarz, R.; Abolhasan, M.; Lipman, J.; Esselle, K.P.; Shariati, N. A review on antenna technologies for ambient RF energy harvesting and wireless power transfer: Designs, challenges and applications. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 17231–17267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, F.; Navarro, L.; Quintero M, C.G.; Pardo, M. A simple WiFi harvester with a switching-based power management scheme to collect energy from ordinary routers. Electronics 2021, 10, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, P.; Niyato, D.; Kim, D.I.; Han, Z. Wireless networks with RF energy harvesting: A contemporary survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2014, 17, 757–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Sarker, M.R.; Saad, M.H.M.; Mohamed, R. Review on comparison of different energy storage technologies used in micro-energy harvesting, WSNs, low-cost microelectronic devices: Challenges and recommendations. Sensors 2021, 21, 5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Barwar, N. Sensor Node Design Optimization Methods for Enhanced Energy Efficiency in Wireless Sensor Networks. In International Conference on Cryptology & Network Security with Machine Learning; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundile, O.O.; Alfa, A.S. A survey on an energy-efficient and energy-balanced routing protocol for wireless sensor networks. Sensors 2017, 17, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Wang, A.; Wang, C.; Hung, P.C.; Lai, C.F. An efficient centroid-based routing protocol for energy management in WSN-assisted IoT. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 18469–18479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.N.; Arshad, A.; Ali, Z.; Hashmi, M.A.; Atif, M. Cluster based routing protocols for wireless sensor networks: An overview. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumka, A.; Chaurasiya, S.K.; Biswas, A.; Mandoria, H.L. A Complete Guide to Wireless Sensor Networks: From Inception to Current Trends; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Iannello, F.; Simeone, O.; Spagnolini, U. Medium access control protocols for wireless sensor networks with energy harvesting. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2012, 60, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srbinovski, B.; Magno, M.; Edwards-Murphy, F.; Pakrashi, V.; Popovici, E. An energy aware adaptive sampling algorithm for energy harvesting WSN with energy hungry sensors. Sensors 2016, 16, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgi, S.M.; Rostami, A.S.; Hosseinabadi, A.A.R.; Balas, V.E. A new clustering protocol for energy harvesting-wireless sensor networks. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2017, 64, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishor, A.; Niyogi, R.; Chronopoulos, A.T.; Zomaya, A.Y. Latency and energy-aware load balancing in cloud data centers: A bargaining game based approach. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2021, 11, 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royaee, Z.; Mirvaziri, H.; Khatibi Bardsiri, A. Designing a context-aware model for RPL load balancing of low power and lossy networks in the internet of things. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 2449–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prauzek, M.; Konecny, J.; Borova, M.; Janosova, K.; Hlavica, J.; Musilek, P. Energy harvesting sources, storage devices and system topologies for environmental wireless sensor networks: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouramdane, O.; Elbouchikhi, E.; Amirat, Y.; Sedgh Gooya, E. Optimal sizing and energy management of microgrids with vehicle-to-grid technology: A critical review and future trends. Energies 2021, 14, 4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathor, S.K.; Saxena, D. Energy management system for smart grid: An overview and key issues. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 4067–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Arefifar, S.A. Energy management in power distribution systems: Review, classification, limitations and challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 92979–93001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smdani, G.; Islam, M.R.; Ahmad Yahaya, A.N.; Bin Safie, S.I. Performance evaluation of advanced energy storage systems: A review. Energy Environ. 2023, 34, 1094–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohalete, N.; Aderibigbe, A.; Ani, E.; Ohenhen, P.; Daraojimba, D. Challenges and innovations in electro-mechanical system integration: A review. Acta Electron. Malays. (AEM) 2024, 8, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraereh, O.A.; Alsaraira, A.; Khan, I.; Choi, B.J. A hybrid energy harvesting design for on-body internet-of-things (IoT) networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, W.S.H.M.W.; Radzi, N.A.M.; Samidi, F.S.; Ismail, A.; Abdullah, F.; Jamaludin, M.Z.; Zakaria, M. 5G technology: Towards dynamic spectrum sharing using cognitive radio networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 14460–14488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, A.; Al Haj Hassan, H.; Abou Chaaya, J.; Mansour, A.; Yao, K.C. Spectrum sensing for cognitive radio: Recent advances and future challenge. Sensors 2021, 21, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Liu, K.R. Advances in cognitive radio networks: A survey. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2010, 5, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amutha, J.; Sharma, S.; Nagar, J. WSN strategies based on sensors, deployment, sensing models, coverage and energy efficiency: Review, approaches and open issues. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2020, 111, 1089–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakas, C.; Kandris, D.; Visvardis, G. Energy efficient routing in wireless sensor networks: A comprehensive survey. Algorithms 2020, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Du, Q. A review of physical layer security techniques for Internet of Things: Challenges and solutions. Entropy 2018, 20, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanenga, A.; Mapunda, G.A.; Jacob, T.M.L.; Marata, L.; Basutli, B.; Chuma, J.M. An overview of key technologies in physical layer security. Entropy 2020, 22, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Nan, Y.; Chen, Y. Maximizing information transmission for energy harvesting sensor networks by an uneven clustering protocol and energy management. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. (TIIS) 2020, 14, 1419–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Shanbhag, K.V.; Sathish, D. Low complexity physical layer security approach for 5G internet of things. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. (IJECE) 2023, 13, 6466–6475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakiba-Herfeh, M.; Chorti, A.; Vincent Poor, H. Physical layer security: Authentication, integrity, and confidentiality. Phys. Layer Secur. 2021, 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hoseini, S.A.; Bouhafs, F.; den Hartog, F. A practical implementation of physical layer security in wireless networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 19th Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 8–11 January 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Khademi Nori, M.; Sharifian, S. EDMARA2: A hierarchical routing protocol for EH-WSNs. Wirel. Netw. 2020, 26, 4303–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Ran, F.; Li, J.; Yan, L.; Shen, H.; Li, A. A novel adaptive cluster based routing protocol for energy-harvesting wireless sensor networks. Sensors 2022, 22, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.D.; Dilts, D.M.; Biswas, G. On the evolutionary dynamics of supply network topologies. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2007, 54, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.K.; Zeadally, S. Energy harvesting in wireless sensor networks: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 1041–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Lan, G.; Hassan, M.; Hu, W.; Das, S.K. Sensing, computing, and communications for energy harvesting IoTs: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2019, 22, 1222–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Singh, G. Energy management systems in sustainable smart cities based on the internet of energy: A technical review. Energies 2023, 16, 6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L. Resource Allocation and Performance Optimization in Communication Networks and the Internet; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Ni, Q.; Liu, W. Cross-layer Framework for Energy Harvesting-LPWAN Resource Management based on Fuzzy Cognitive Maps and Adaptive Glowworm Swarm Optimization for Smart Forest. IEEE Sensors J. 2024, 24, 17067–17079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Saad, M.R.; Djenouri, Y.; Hu, G.; Ali, A.A.; Shaban, H. Metaheuristic algorithms and their applications in wireless sensor networks: Review, open issues, and challenges. Clust. Comput. 2024, 27, 13643–13673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangu, S.K.; Lolla, P.R.; Dhenuvakonda, K.R.; Singh, A.R. Recent trends in power management strategies for optimal operation of distributed energy resources in microgrids: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 9889–9911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo, P.; Ochoa-Correa, D.; Villa-Ávila, E. Optimizing microgrid operation: Integration of emerging technologies and artificial intelligence for energy efficiency. Electronics 2024, 13, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasiya, S.K.; Mondal, S.; Biswas, A.; Nayyar, A.; Shah, M.A.; Banerjee, R. An energy-efficient hybrid clustering technique (EEHCT) for IoT-based multilevel heterogeneous wireless sensor networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 25941–25958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Mamun, Q.; Islam, R. Balancing Security and Efficiency: A Power Consumption Analysis of a Lightweight Block Cipher. Electronics 2024, 13, 4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, T.; Jeyamala, D.; Sellamuthu, S.; Indra Priyadharshini, S. A Secure Framework for MIoT: TinyML-powered Emergency Alerts and Intrusion Detection for Secure Real-time Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC), Kirtipur, Nepal, 3–5 October 2024; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.N.; Halim, M.A.; Khan, M.Y.A.; Ibrahim, S.; Haque, A. A Comprehensive Review on Techniques and Challenges of Energy Harvesting from Distributed Renewable Energy Sources for Wireless Sensor Networks. Control Syst. Optim. Lett. 2024, 2, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]