Recent Advances in Proteomics-Based Approaches to Studying Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

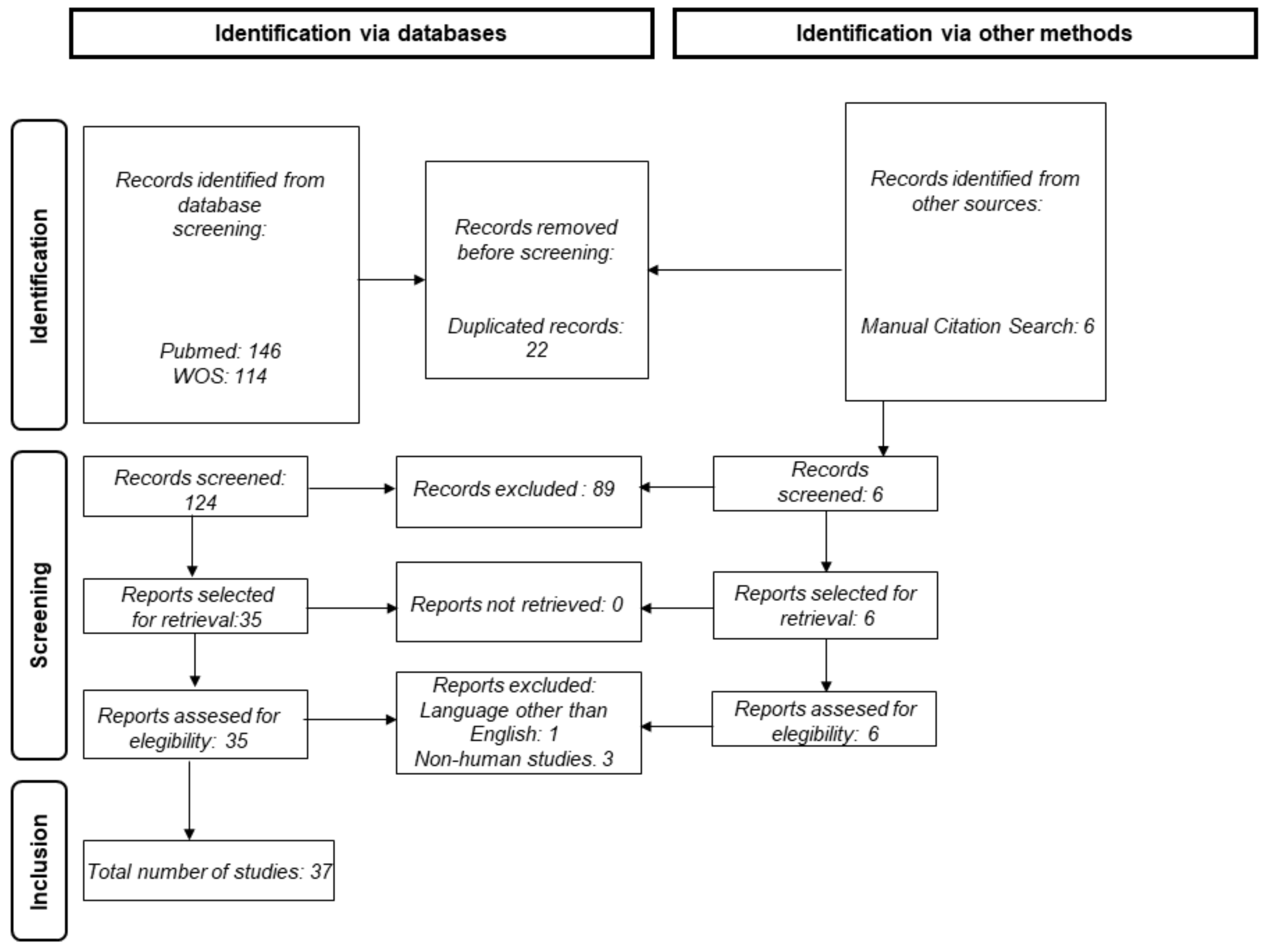

2. Methods

2.1. Database Retrieval and Search Strategy

2.2. Data Extraction

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Recent Advances in Proteomic Approaches to the Study of the Disease

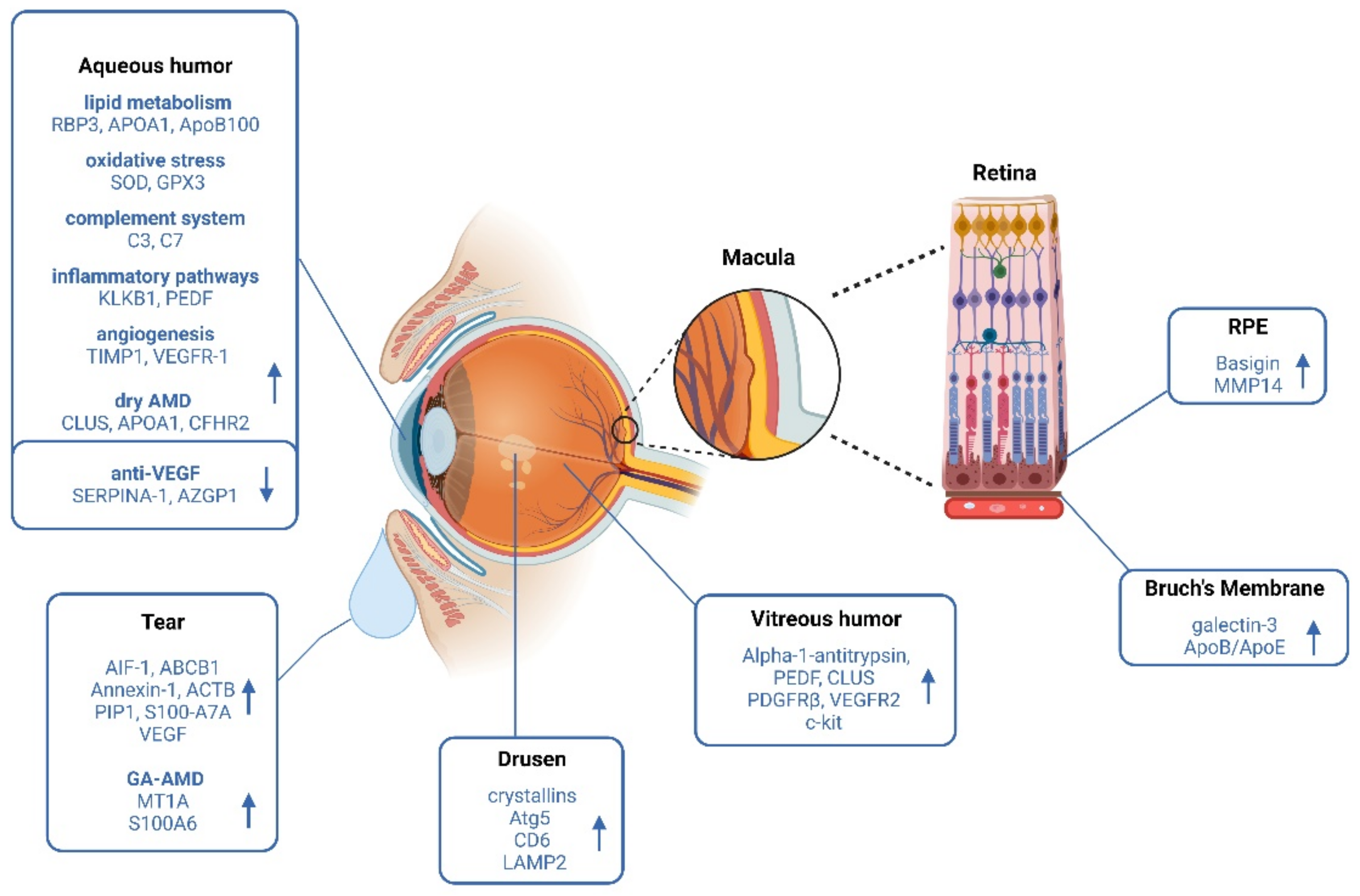

3.2. Proteomics on Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells and Extracellular Vesicles in AMD

3.3. Proteomics on Bruch´s Membrane in AMD

3.4. Proteomics on Drusen in AMD

3.5. Proteomics on Vitreous Humor in AMD

3.6. Proteomics on Aqueous Humor in AMD

3.7. Proteomics on Tear Fluid in AMD

3.8. Proteomics on Blood in AMD

3.9. Proteomics on Urine in AMD

3.10. Therapeutic Challenges and Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bourne, R.R.A.; Jonas, J.B.; Bron, A.M.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Das, A.; Flaxman, S.R.; Friedman, D.S.; Keeffe, J.E.; Kempen, J.H.; Leasher, J.; et al. Prevalence and causes of vision loss in high-income countries and in Eastern and Central Europe in 2015: Magnitude, temporal trends and projections. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campochiaro, P.A.; Soloway, P.; Ryan, S.J.; Miller, J.W. The pathogenesis of choroidal neovascularization in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Mol. Vis. 1999, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holz, F.G.; Strauss, E.C.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; van Lookeren Campagne, M. Geographic atrophy: Clinical features and potential therapeutic approaches. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, U.; Evans, J.; Rosenfeld, P.J. Age related macular degeneration. BMJ 2010, 340, c981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutto, I.; Lutty, G. Understanding age-related macular degeneration (AMD): Relationships between the photoreceptor/retinal pigment epithelium/Bruch’s membrane/choriocapillaris complex. Mol. Aspects Med. 2012, 33, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.D.; Momi, R.S.; Hariprasad, S.M. Review of ranibizumab trials for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2011, 26, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Quintanilla, L.; Luaces-Rodríguez, A.; Gil-Martínez, M.; Mondelo-García, C.; Maroñas, O.; Mangas-Sanjuan, V.; González-Barcia, M.; Zarra-Ferro, I.; Aguiar, P.; Otero-Espinar, F.J.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Drugs in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; Lindsley, K.; Vedula, S.S.; Krzystolik, M.G.; Hawkins, B.S. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD005139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Martínez, M.; Santos-Ramos, P.; Fernández-Rodríguez, M.; Abraldes, M.J.; Rodríguez-Cid, M.J.; Santiago-Varela, M.; Fernández-Ferreiro, A.; Gómez-Ulla, F. Pharmacological Advances in the Treatment of Age-related Macular Degeneration. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaynak, S.; Kaya, M.; Kaya, D. Is There a Relationship Between Use of Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Agents and Atrophic Changes in Age-Related Macular Degeneration Patients? Turk. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 48, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroñas, O.; García-Quintanilla, L.; Luaces-Rodríguez, A.; Fernández-Ferreiro, A.; Latorre-Pellicer, A.; Abraldes, M.J.; Lamas, M.J.; Carracedo, A. Anti-VEGF Treatment and Response in Age-related Macular Degeneration: Disease’s Susceptibility, Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacokinetics. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnapriya, R.; Chew, E.Y. Age-related macular degeneration-clinical review and genetics update. Clin. Genet. 2013, 84, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Liu, S.; Hao, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Hu, W.; Huang, P. Association Between Complement Factor C2/C3/CFB/CFH Polymorphisms and Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Meta-Analysis. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 2018, 22, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarthy, U.; McKay, G.J.; de Jong, P.T.; Rahu, M.; Seland, J.; Soubrane, G.; Tomazzoli, L.; Topouzis, F.; Vingerling, J.R.; Vioque, J.; et al. ARMS2 increases the risk of early and late age-related macular degeneration in the European Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinchilla, B.; Foltopoulou, P.; Fernandez-Godino, R. Tick-over-mediated complement activation is sufficient to cause basal deposit formation in cell-based models of macular degeneration. J. Pathol. 2021, 255, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, J.M.; Cote, J.; Davis, N.; Rosner, B. Progression of age-related macular degeneration: Association with body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-hip ratio. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2003, 121, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, R.; Klein, B.E.; Tomany, S.C.; Cruickshanks, K.J. The association of cardiovascular disease with the long-term incidence of age-related maculopathy: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kananen, F.; Strandberg, T.; Loukovaara, S.; Immonen, I. Early middle age cholesterol levels and the association with age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021, 99, e1063–e1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.; SanGiovanni, J.P.; Danis, R.; Domalpally, A.; McBee, W.; Sperduto, R.; Ferris, F.L.; Group, A.R. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2): Study design and baseline characteristics (AREDS2 report number 1). Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 2282–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarniranta, K.; Sinha, D.; Blasiak, J.; Kauppinen, A.; Veréb, Z.; Salminen, A.; Boulton, M.E.; Petrovski, G. Autophagy and heterophagy dysregulation leads to retinal pigment epithelium dysfunction and development of age-related macular degeneration. Autophagy 2013, 9, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrett, S.G.; Boulton, M.E. Consequences of oxidative stress in age-related macular degeneration. Mol. Aspects Med. 2012, 33, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, K.A.; Yang, D. N-Acetylcysteine Amide Protects Against Oxidative Stress-Induced Microparticle Release from Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakkaraju, A.; Umapathy, A.; Tan, L.X.; Daniele, L.; Philp, N.J.; Boesze-Battaglia, K.; Williams, D.S. The cell biology of the retinal pigment epithelium. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2020, 78, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrington, D.A.; Sinha, D.; Kaarniranta, K. Defects in retinal pigment epithelial cell proteolysis and the pathology associated with age-related macular degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2016, 51, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Clark, M.E.; Crossman, D.K.; Kojima, K.; Messinger, J.D.; Mobley, J.A.; Curcio, C.A. Abundant lipid and protein components of drusen. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, N.G.; ElShelmani, H.; Singh, M.K.; Mansergh, F.C.; Wride, M.A.; Padilla, M.; Keegan, D.; Hogg, R.E.; Ambati, B.K. Risk factors and biomarkers of age-related macular degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2016, 54, 64–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, S.L.; Campbell, M.; Ozaki, E.; Salomon, R.G.; Mori, A.; Kenna, P.F.; Farrar, G.J.; Kiang, A.S.; Humphries, M.M.; Lavelle, E.C.; et al. NLRP3 has a protective role in age-related macular degeneration through the induction of IL-18 by drusen components. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Rong, R.; Xia, X. Spotlight on pyroptosis: Role in pathogenesis and therapeutic potential of ocular diseases. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, N.H.; Keonin, J.; Luthert, P.J.; Frennesson, C.I.; Weingeist, D.M.; Wolf, R.L.; Mullins, R.F.; Hageman, G.S. Decreased thickness and integrity of the macular elastic layer of Bruch’s membrane correspond to the distribution of lesions associated with age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 166, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinchilla, B.; Fernandez-Godino, R. AMD-Like Substrate Causes Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition in iPSC-Derived Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Wild Type but Not C3-Knockout. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelsalam, A.; Del Priore, L.; Zarbin, M.A. Drusen in age-related macular degeneration: Pathogenesis, natural course, and laser photocoagulation-induced regression. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1999, 44, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Priore, L.V.; Kuo, Y.H.; Tezel, T.H. Age-related changes in human RPE cell density and apoptosis proportion in situ. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 3312–3318. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, K.B.; Zweifel, S.A.; Engelbert, M. Do we need a new classification for choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration? Retina 2010, 30, 1333–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigon, A.; Vadalà, M.; Bonfiglio, V.M.E.; Reibaldi, M.; Eandi, C.M. Early OCTA Changes of Type 3 Macular Neovascularization Following Brolucizumab Intravitreal Injections. Medicina 2022, 58, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savastano, M.C.; Falsini, B.; Ferrara, S.; Scampoli, A.; Piccardi, M.; Savastano, A.; Rizzo, S. Subretinal Pigment Epithelium Illumination Combined with Focal Electroretinogram and Visual Acuity for Early Diagnosis and Prognosis of Non-Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration: New Insights for Personalized Medicine. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, W.L.; Su, X.; Li, X.; Cheung, C.M.; Klein, R.; Cheng, C.Y.; Wong, T.Y. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e106–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, J.; Pernas, P.F.; Labora, J.F.; Blanco, F.; Arufe, M.D. Proteomic Applications in the Study of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Proteomes 2014, 2, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLafferty, F.W. A century of progress in molecular mass spectrometry. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2011, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivanich, M.K.; Gu, T.J.; Tabang, D.N.; Li, L. Recent advances in isobaric labeling and applications in quantitative proteomics. Proteomics 2022, 22, e2100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Wallstrom, G.; Yu, X.; Hopper, M.; Van Duine, J.; Steel, J.; Park, J.; Wiktor, P.; Kahn, P.; Brunner, A.; et al. Identification of Antibody Targets for Tuberculosis Serology using High-Density Nucleic Acid Programmable Protein Arrays. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2017, 16, S277–S289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, A.M.; Wagner, B.D.; Weiss, S.J.; Wall, K.M.; Palestine, A.G.; Mathias, M.T.; Siringo, F.S.; Cathcart, J.N.; Patnaik, J.L.; Drolet, D.W.; et al. Proteomic Profiles in Advanced Age-Related Macular Degeneration Using an Aptamer-Based Proteomic Technology. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holly, F.J. Tear film physiology. Am. J. Optom. Physiol. Opt. 1980, 57, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green-Church, K.B.; Nichols, K.K.; Kleinholz, N.M.; Zhang, L.; Nichols, J.J. Investigation of the human tear film proteome using multiple proteomic approaches. Mol. Vis. 2008, 14, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Von Thun Und Hohenstein-Blaul, N.; Funke, S.; Grus, F.H. Tears as a source of biomarkers for ocular and systemic diseases. Exp. Eye Res. 2013, 117, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Golubnitschaja, O. Mass spectrometry analysis of human tear fluid biomarkers specific for ocular and systemic diseases in the context of 3P medicine. EPMA J. 2021, 12, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Loo, J.A.; Wong, D.T. Human body fluid proteome analysis. Proteomics 2006, 6, 6326–6353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kersten, E.; Paun, C.C.; Schellevis, R.L.; Hoyng, C.B.; Delcourt, C.; Lengyel, I.; Peto, T.; Ueffing, M.; Klaver, C.C.W.; Dammeier, S.; et al. Systemic and ocular fluid compounds as potential biomarkers in age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2018, 63, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabb, J.W.; Miyagi, M.; Gu, X.; Shadrach, K.; West, K.A.; Sakaguchi, H.; Kamei, M.; Hasan, A.; Yan, L.; Rayborn, M.E.; et al. Drusen proteome analysis: An approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14682–14687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcazar, O.; Hawkridge, A.M.; Collier, T.S.; Cousins, S.W.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Muddiman, D.C.; Marin-Castano, M.E. Proteomics characterization of cell membrane blebs in human retinal pigment epithelium cells. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2009, 8, 2201–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.L.; Lukas, T.J.; Yuan, M.; Du, N.; Tso, M.O.; Neufeld, A.H. Autophagy and exosomes in the aged retinal pigment epithelium: Possible relevance to drusen formation and age-related macular degeneration. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Gu, X.; Crabb, J.S.; Yue, X.; Shadrach, K.; Hollyfield, J.G.; Crabb, J.W. Quantitative proteomics: Comparison of the macular Bruch membrane/choroid complex from age-related macular degeneration and normal eyes. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2010, 9, 1031–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biasutto, L.; Chiechi, A.; Couch, R.; Liotta, L.A.; Espina, V. Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) exosomes contain signaling phosphoproteins affected by oxidative stress. Exp. Cell Res. 2013, 319, 2113–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, U.L.; Grigsby, D.; Cady, M.A.; Landowski, M.; Skiba, N.P.; Liu, J.; Remaley, A.T.; Klingeborn, M.; Bowes Rickman, C. High-density lipoproteins are a potential therapeutic target for age-related macular degeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 13601–13616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Bellver, M.; Mighty, J.; Aparicio-Domingo, S.; Li, K.V.; Shi, C.; Zhou, J.; Cobb, H.; McGrath, P.; Michelis, G.; Lenhart, P.; et al. Extracellular vesicles released by human retinal pigment epithelium mediate increased polarised secretion of drusen proteins in response to AMD stressors. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, S.; Lin, T.; Ke, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, X. A Pilot Application of an iTRAQ-Based Proteomics Screen Estimates the Effects of Cigarette Smokers’ Serum on RPE Cells with AMD High-Risk Alleles. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senabouth, A.; Daniszewski, M.; Lidgerwood, G.E.; Liang, H.H.; Hernández, D.; Mirzaei, M.; Keenan, S.N.; Zhang, R.; Han, X.; Neavin, D.; et al. Transcriptomic and proteomic retinal pigment epithelium signatures of age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauhar, R.; Biber, J.; Jabri, Y.; Kim, M.; Hu, J.; Kaplan, L.; Pfaller, A.M.; Schäfer, N.; Enzmann, V.; Schlötzer-Schrehardt, U.; et al. As in Real Estate, Location Matters: Cellular Expression of Complement Varies Between Macular and Peripheral Regions of the Retina and Supporting Tissues. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 895519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, M.J.; Hoffmann, J.; Nguyen, N.; Pfister, M.; Mischak, H.; Mullen, W.; Husi, H.; Rejdak, R.; Koch, F.; Jankowski, J.; et al. Proteomics of vitreous humor of patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobl, M.; Reich, M.; Dacheva, I.; Siwy, J.; Mullen, W.; Schanstra, J.P.; Choi, C.Y.; Kopitz, J.; Kretz, F.T.A.; Auffarth, G.U.; et al. Proteomics of vitreous in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 146, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schori, C.; Trachsel, C.; Grossmann, J.; Zygoula, I.; Barthelmes, D.; Grimm, C. The Proteomic Landscape in the Vitreous of Patients with Age-Related and Diabetic Retinal Disease. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, AMD31–AMD40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, J.H.; Lim, D.; Park, K.H.; Chae, J.B.; Jang, H.; Lee, J.; Chung, H. Quantitative proteomic analysis of aqueous humor from patients with drusen and reticular pseudodrusen in age-related macular degeneration. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018, 18, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiarczyk, M.; Kaarniranta, K.; Winiarczyk, S.; Adaszek, Ł.; Winiarczyk, D.; Mackiewicz, J. Tear film proteome in age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2018, 256, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronado, B.N.L.; da Cunha, F.B.S.; de Oliveira, R.M.; Nóbrega, O.T.; Ricart, C.A.O.; Fontes, W.; de Sousa, M.V.; de Ávila, M.P.; Martins, A.M.A. Novel Possible Protein Targets in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Pilot Study Experiment. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 692272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, J.H.; Kim, H.; Shin, J.H.; Moon, S.W. Aqueous humor cytokine levels through microarray analysis and a sub-analysis based on optical coherence tomography in wet age-related macular degeneration patients. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021, 21, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinsky, B.; Beykin, G.; Grunin, M.; Amer, R.; Khateb, S.; Tiosano, L.; Almeida, D.; Hagbi-Levi, S.; Elbaz-Hayoun, S.; Chowers, I. Analysis of the Aqueous Humor Proteome in Patients with Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiarczyk, M.; Winiarczyk, D.; Michalak, K.; Kaarniranta, K.; Adaszek, Ł.; Winiarczyk, S.; Mackiewicz, J. Dysregulated Tear Film Proteins in Macular Edema Due to the Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Are Involved in the Regulation of Protein Clearance, Inflammation, and Neovascularization. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Sanchez, J.C.; Dinabandhu, A.; Guo, C.; Patel, T.P.; Yang, Z.; Hu, M.W.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Malik, D.; et al. Aqueous proteins help predict the response of patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration to anti-VEGF therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e144469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidatul-Adha, M.; Zunaina, E.; Aini-Amalina, M.N. Evaluation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) level in the tears and serum of age-related macular degeneration patients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.Y.; Chen, C.T.; Wu, H.H.; Liao, C.C.; Hua, K.; Hsu, C.H.; Chen, C.F. Proteomic Profiling of Aqueous Humor Exosomes from Age-related Macular Degeneration Patients. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 19, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, E.; García, M.; Fernández-Vega, B.; Pereiro, R.; Lobo, L.; González-Iglesias, H. Targeted Analysis of Tears Revealed Specific Altered Metal Homeostasis in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lip, P.L.; Blann, A.D.; Hope-Ross, M.; Gibson, J.M.; Lip, G.Y. Age-related macular degeneration is associated with increased vascular endothelial growth factor, hemorheology and endothelial dysfunction. Ophthalmology 2001, 108, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaprasad, S.; Chong, N.V.; Bailey, T.A. Serum elastin-derived peptides in age-related macular degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005, 46, 3046–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, D.C.; Charng, M.J.; Lee, F.L.; Hsu, W.M.; Chen, S.J. Different plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and nitric oxide between patients with choroidal and retinal neovascularization. Ophthalmologica 2006, 220, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.H.; Tan, A.G.; Rochtchina, E.; Favaloro, E.J.; Williams, A.; Mitchell, P.; Wang, J.J. Circulating inflammatory markers and hemostatic factors in age-related maculopathy: A population-based case-control study. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 1983–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudnicka, A.R.; MacCallum, P.K.; Whitelocke, R.; Meade, T.W. Circulating markers of arterial thrombosis and late-stage age-related macular degeneration: A case-control study. Eye 2010, 24, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, A.M.; Costa, R.; Falcão, M.S.; Barthelmes, D.; Mendonça, L.S.; Fonseca, S.L.; Gonçalves, R.; Gonçalves, C.; Falcão-Reis, F.M.; Soares, R. Vascular endothelial growth factor plasma levels before and after treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration with bevacizumab or ranibizumab. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012, 90, e25–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Yu, X.; Dai, H. Intravitreal injection of ranibizumab for treatment of age-related macular degeneration: Effects on serum VEGF concentration. Curr. Eye Res. 2014, 39, 518–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Woo, S.J.; Suh, E.J.; Ahn, J.; Park, J.H.; Hong, H.K.; Lee, J.E.; Ahn, S.J.; Hwang, D.J.; Kim, K.W.; et al. Identification of vinculin as a potential plasma marker for age-related macular degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 7166–7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Ahn, S.J.; Woo, S.J.; Hong, H.K.; Suh, E.J.; Ahn, J.; Park, J.H.; Ryoo, N.K.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, K.W.; et al. Proteomics-based identification and validation of novel plasma biomarkers phospholipid transfer protein and mannan-binding lectin serine protease-1 in age-related macular degeneration. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhu, M.; Geng-Spyropoulos, M.; Shardell, M.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Gudnason, V.; Eiriksdottir, G.; Schaumberg, D.; van Eyk, J.E.; Ferrucci, L.; et al. A novel, multiplexed targeted mass spectrometry assay for quantification of complement factor H (CFH) variants and CFH-related proteins 1-5 in human plasma. Proteomics 2017, 17, 1600237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palestine, A.G.; Wagner, B.D.; Patnaik, J.L.; Baldermann, R.; Mathias, M.T.; Mandava, N.; Lynch, A.M. Plasma C-C Chemokine Concentrations in Intermediate Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 710595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivagurunathan, S.; Selvan, L.D.N.; Khan, A.A.; Parameswaran, S.; Bhattacharjee, H.; Gogoi, K.; Gowda, H.; Keshava Prasad, T.S.; Pandey, A.; Kumar, S.A.; et al. Proteomics-based approach for differentiation of age-related macular degeneration sub-types. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 69, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emilsson, V.; Gudmundsson, E.F.; Jonmundsson, T.; Jonsson, B.G.; Twarog, M.; Gudmundsdottir, V.; Li, Z.; Finkel, N.; Poor, S.; Liu, X.; et al. A proteogenomic signature of age-related macular degeneration in blood. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domon, B.; Aebersold, R. Mass spectrometry and protein analysis. Science 2006, 312, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, J.; Landeira-Abia, A.; Fafián-Labora, J.A.; Fernández-Pernas, P.; Lesende-Rodríguez, I.; Fernández-Puente, P.; Fernández-Moreno, M.; Delmiro, A.; Martín, M.A.; Blanco, F.J.; et al. iTRAQ-based analysis of progerin expression reveals mitochondrial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species accumulation and altered proteostasis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, J.; Estévez, O.; González-Fernández, Á.; Anibarro, L.; Pallarés, Á.; Reljic, R.; Mussá, T.; Gomes-Maueia, C.; Nguilichane, A.; Gallardo, J.M.; et al. Serum proteomics of active tuberculosis patients and contacts reveals unique processes activated during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calamia, V.; Fernández-Puente, P.; Mateos, J.; Lourido, L.; Rocha, B.; Montell, E.; Vergés, J.; Ruiz-Romero, C.; Blanco, F.J. Pharmacoproteomic study of three different chondroitin sulfate compounds on intracellular and extracellular human chondrocyte proteomes. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2012, 11, M111.013417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.C.; Hunter, C.L.; Liu, Y.; Schilling, B.; Rosenberger, G.; Bader, S.L.; Chan, D.W.; Gibson, B.W.; Gingras, A.C.; Held, J.M.; et al. Multi-laboratory assessment of reproducibility, qualitative and quantitative performance of SWATH-mass spectrometry. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selevsek, N.; Chang, C.Y.; Gillet, L.C.; Navarro, P.; Bernhardt, O.M.; Reiter, L.; Cheng, L.Y.; Vitek, O.; Aebersold, R. Reproducible and consistent quantification of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteome by SWATH-mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2015, 14, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, O.T.; Gillet, L.C.; Collins, B.C.; Navarro, P.; Rosenberger, G.; Wolski, W.E.; Lam, H.; Amodei, D.; Mallick, P.; MacLean, B.; et al. Building high-quality assay libraries for targeted analysis of SWATH MS data. Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, D.; Scandola, S.; Uhrig, R.G. BoxCar and Library-Free Data-Independent Acquisition Substantially Improve the Depth, Range, and Completeness of Label-Free Quantitative Proteomics. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Val, A.; Bekker-Jensen, D.B.; Hogrebe, A.; Olsen, J.V. Data Processing and Analysis for DIA-Based Phosphoproteomics Using Spectronaut. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2361, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ståhlberg, A.; Thomsen, C.; Ruff, D.; Åman, P. Quantitative PCR analysis of DNA, RNAs, and proteins in the same single cell. Clin. Chem. 2012, 58, 1682–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Ying, W.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, S.; Cai, Y.; Wang, J.; He, F.; et al. Different immunoaffinity fractionation strategies to characterize the human plasma proteome. J. Proteome Res. 2006, 5, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, S.; Nickels, P.C.; Strauss, M.T.; Jimenez Sabinina, V.; Ellenberg, J.; Carter, J.D.; Gupta, S.; Janjic, N.; Jungmann, R. Modified aptamers enable quantitative sub-10-nm cellular DNA-PAINT imaging. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcazar, O.; Cousins, S.W.; Marin-Castaño, M.E. MMP-14 and TIMP-2 overexpression protects against hydroquinone-induced oxidant injury in RPE: Implications for extracellular matrix turnover. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 5662–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Roles of extracellular vesicles in the aging microenvironment and age-related diseases. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, G.; van Niel, G.; Stahl, P.D. Extracellular vesicles and homeostasis-An emerging field in bioscience research. FASEB Bioadv. 2021, 3, 456–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooff, Y.; Cioanca, A.V.; Chu-Tan, J.A.; Aggio-Bruce, R.; Schumann, U.; Natoli, R. Small-Medium Extracellular Vesicles and Their miRNA Cargo in Retinal Health and Degeneration: Mediators of Homeostasis, and Vehicles for Targeted Gene Therapy. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Curcio, C.A. Structure, function and pathology of Bruch’s membrane. In Retina; Hinton, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 522–543. [Google Scholar]

- Guymer, R.; Luthert, P.; Bird, A. Changes in Bruch’s membrane and related structures with age. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 1999, 18, 59–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navneet, S.; Rohrer, B. Elastin turnover in ocular diseases: A special focus on age-related macular degeneration. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 222, 109164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morohoshi, K.; Patel, N.; Ohbayashi, M.; Chong, V.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; Bird, A.C.; Ono, S.J. Serum autoantibody biomarkers for age-related macular degeneration and possible regulators of neovascularization. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2012, 92, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midena, E.; Degli Angeli, C.; Blarzino, M.C.; Valenti, M.; Segato, T. Macular function impairment in eyes with early age-related macular degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997, 38, 469–477. [Google Scholar]

- Kokavec, J.; Min, S.H.; Tan, M.H.; Gilhotra, J.S.; Newland, H.S.; Durkin, S.R.; Grigg, J.; Casson, R.J. Biochemical analysis of the living human vitreous. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2016, 44, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacouture, A. [Anatomy-physiology of the eye]. Rev. Infirm. 2006, 120, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tamhane, M.; Cabrera-Ghayouri, S.; Abelian, G.; Viswanath, V. Review of Biomarkers in Ocular Matrices: Challenges and Opportunities. Pharm. Res. 2019, 36, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamai, M.; Nakazawa, M. A Collection System to Obtain Vitreous Humor in Clinical Cases. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1991, 109, 465–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Campos, T.D.P.; da Cruz Rodrigues, K.C.; Pereira, R.M.; Anaruma, C.P.; Dos Santos Canciglieri, R.; de Melo, D.G.; da Silva, A.S.R.; Cintra, D.E.; Ropelle, E.R.; Pauli, J.R.; et al. The protective roles of clusterin in ocular diseases caused by obesity and diabetes mellitus type 2. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 4637–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fini, M.E.; Bauskar, A.; Jeong, S.; Wilson, M.R. Clusterin in the eye: An old dog with new tricks at the ocular surface. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 147, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, M.; Picciani, R.G.; Lee, R.K.; Bhattacharya, S.K. Aqueous humor dynamics: A review. Open Ophthalmol. J. 2010, 4, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcio, C.A.; Millican, C.L.; Bailey, T.; Kruth, H.S. Accumulation of cholesterol with age in human Bruch’s membrane. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001, 42, 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Hu, L.G. Serpin peptidase inhibitor clade A member 1-overexpression in gastric cancer promotes tumor progression. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Li, W.; He, G.; Zhu, D.; Lv, S.; Tang, W.; Jian, M.; Zheng, P.; Yang, L.; Qi, Z.; et al. Zinc-α2-glycoprotein 1 promotes EMT in colorectal cancer by filamin A mediated focal adhesion pathway. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 5557–5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinle, N.C.; Du, W.; Gibson, A.; Saroj, N. Outcomes by Baseline Choroidal Neovascularization Features in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Post Hoc Analysis of the VIEW Studies. Ophthalmol. Retina 2021, 5, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiffany, J.M. Tears in health and disease. Eye 2003, 17, 923–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rentka, A.; Koroskenyi, K.; Harsfalvi, J.; Szekanecz, Z.; Szucs, G.; Szodoray, P.; Kemeny-Beke, A. Evaluation of commonly used tear sampling methods and their relevance in subsequent biochemical analysis. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 54, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versura, P.; Nanni, P.; Bavelloni, A.; Blalock, W.L.; Piazzi, M.; Roda, A.; Campos, E.C. Tear proteomics in evaporative dry eye disease. Eye 2010, 24, 1396–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turlea, M.; Cioca, D.P.; Mârza, F.; Turlea, C. [Lacrimal assessment of lg E in cases with allergic conjunctivitis]. Oftalmologia 2009, 53, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- López-López, M.; Regueiro, U.; Bravo, S.B.; Chantada-Vázquez, M.D.P.; Pena, C.; Díez-Feijoo, E.; Hervella, P.; Lema, I. Shotgun Proteomics for the Identification and Profiling of the Tear Proteome of Keratoconus Patients. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acera, A.; Rocha, G.; Vecino, E.; Lema, I.; Durán, J.A. Inflammatory markers in the tears of patients with ocular surface disease. Ophthalmic Res. 2008, 40, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lema, I.; Sobrino, T.; Durán, J.A.; Brea, D.; Díez-Feijoo, E. Subclinical keratoconus and inflammatory molecules from tears. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 93, 820–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, T.B.; Launer, L.J.; Eiriksdottir, G.; Kjartansson, O.; Jonsson, P.V.; Sigurdsson, G.; Thorgeirsson, G.; Aspelund, T.; Garcia, M.E.; Cotch, M.F.; et al. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study: Multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 165, 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiercz, R.; Cheng, D.; Kim, D.; Bedford, M.T. Ribosomal protein rpS2 is hypomethylated in PRMT3-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 16917–16923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Hayakawa, M.; Sakai, K.; Fujimura, Y.; Ogata, N. Intravitreal injection of aflibercept, an anti-VEGF antagonist, down-regulates plasma von Willebrand factor in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, O.; Lavalette, S.; Hu, S.J.; Housset, M.; Raoul, W.; Eandi, C.; Sahel, J.A.; Sullivan, P.M.; Guillonneau, X.; Sennlaub, F. APOE Isoforms Control Pathogenic Subretinal Inflammation in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 13568–13576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, G.J.; Patterson, C.C.; Chakravarthy, U.; Dasari, S.; Klaver, C.C.; Vingerling, J.R.; Ho, L.; de Jong, P.T.; Fletcher, A.E.; Young, I.S.; et al. Evidence of association of APOE with age-related macular degeneration: A pooled analysis of 15 studies. Hum. Mutat. 2011, 32, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickremasinghe, S.S.; Sandhu, S.S.; Amirul-Islam, F.M.; Abedi, F.; Richardson, A.J.; Baird, P.N.; Guymer, R.H. Polymorphisms in the APOE gene and the location of retinal fluid in eyes with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina 2014, 34, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, J.M.; Zorapapel, N.C.; Rich, K.A.; Wagstaff, R.E.; Lambert, R.W.; Rosenberg, S.E.; Moghaddas, F.; Pirouzmanesh, A.; Aoki, A.M.; Kenney, M.C. Effects of cholesterol and apolipoprotein E on retinal abnormalities in ApoE-deficient mice. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001, 42, 1891–1900. [Google Scholar]

- Tuo, J.; Bojanowski, C.M.; Zhou, M.; Shen, D.; Ross, R.J.; Rosenberg, K.I.; Cameron, D.J.; Yin, C.; Kowalak, J.A.; Zhuang, Z.; et al. Murine ccl2/cx3cr1 deficiency results in retinal lesions mimicking human age-related macular degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 3827–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzedine, H.; Bodaghi, B.; Launay-Vacher, V.; Deray, G. Eye and kidney: From clinical findings to genetic explanations. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003, 14, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, P.F.; Heinen, S.; Józsi, M.; Skerka, C. Complement and diseases: Defective alternative pathway control results in kidney and eye diseases. Mol. Immunol. 2006, 43, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson-Berka, J.L.; Agrotis, A.; Deliyanti, D. The retinal renin-angiotensin system: Roles of angiotensin II and aldosterone. Peptides 2012, 36, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabanayagam, C.; Lye, W.K.; Januszewski, A.; Banu Binte Mohammed Abdul, R.; Cheung, G.C.M.; Kumari, N.; Wong, T.Y.; Cheng, C.Y.; Lamoureux, E. Urinary Isoprostane Levels and Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 2538–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erie, J.C.; Good, J.A.; Butz, J.A.; Hodge, D.O.; Pulido, J.S. Urinary cadmium and age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 144, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.W.; Wong, T.Y.; Cheng, C.Y.; Sabanayagam, C. Kidney and eye diseases: Common risk factors, etiological mechanisms, and pathways. Kidney Int. 2014, 85, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lains, I.; Mendez, K.M.; Gil, J.Q.; Miller, J.B.; Kelly, R.S.; Barreto, P.; Kim, I.K.; Vavvas, D.G.; Murta, J.N.; Liang, L.; et al. Urinary Mass Spectrometry Profiles in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laíns, I.; Duarte, D.; Barros, A.S.; Martins, A.S.; Carneiro, T.J.; Gil, J.Q.; Miller, J.B.; Marques, M.; Mesquita, T.S.; Barreto, P.; et al. Urine Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Metabolomics in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soundara Pandi, S.P.; Ratnayaka, J.A.; Lotery, A.J.; Teeling, J.L. Progress in developing rodent models of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 203, 108404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remington, L.A. Clinical Anatomy of the Visual System; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 314–315. [Google Scholar]

- Rastoin, O.; Pagès, G.; Dufies, M. Experimental Models in Neovascular Age Related Macular Degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.N.; Patel, P.A.; Land, M.R.; Bakerkhatib-Taha, I.; Ahmed, H.; Sheth, V. Targeting the Complement Cascade for Treatment of Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.S.; Grossi, F.V.; El Mehdi, D.; Gerber, M.R.; Brown, D.M.; Heier, J.S.; Wykoff, C.C.; Singerman, L.J.; Abraham, P.; Grassmann, F.; et al. Complement C3 Inhibitor Pegcetacoplan for Geographic Atrophy Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Randomized Phase 2 Trial. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wykoff, C.C.; Rosenfeld, P.J.; Waheed, N.K.; Singh, R.P.; Ronca, N.; Slakter, J.S.; Staurenghi, G.; Monés, J.; Baumal, C.R.; Saroj, N.; et al. Characterizing New-Onset Exudation in the Randomized Phase 2 FILLY Trial of Complement Inhibitor Pegcetacoplan for Geographic Atrophy. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1325–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, G.J.; Westby, K.; Csaky, K.G.; Monés, J.; Pearlman, J.A.; Patel, S.S.; Joondeph, B.C.; Randolph, J.; Masonson, H.; Rezaei, K.A. C5 Inhibitor Avacincaptad Pegol for Geographic Atrophy Due to Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Randomized Pivotal Phase 2/3 Trial. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nittala, M.G.; Metlapally, R.; Ip, M.; Chakravarthy, U.; Holz, F.G.; Staurenghi, G.; Waheed, N.; Velaga, S.B.; Lindenberg, S.; Karamat, A.; et al. Association of Pegcetacoplan with Progression of Incomplete Retinal Pigment Epithelium and Outer Retinal Atrophy in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Post Hoc Analysis of the FILLY Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022, 140, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holz, F.G.; Sadda, S.R.; Busbee, B.; Chew, E.Y.; Mitchell, P.; Tufail, A.; Brittain, C.; Ferrara, D.; Gray, S.; Honigberg, L.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Lampalizumab for Geographic Atrophy Due to Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Chroma and Spectri Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018, 136, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Balado, A.; Bandín-Vilar, E.; Cuartero-Martínez, A.; García-Quintanilla, L.; Hermelo-Vidal, G.; García-Otero, X.; Rodríguez-Martínez, L.; Mateos, J.; Hernández-Blanco, M.; Aguiar, P.; et al. Cysteamine Eye Drops in Hyaluronic Acid Packaged in Innovative Single-Dose Systems: Stability and Ocular Biopermanence. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.R.; Venkatraman, S.S. Drug delivery to the eye: What benefits do nanocarriers offer? Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Bisht, R.; Rupenthal, I.D.; Mitra, A.K. Polymeric micelles for ocular drug delivery: From structural frameworks to recent preclinical studies. J. Control. Release 2017, 248, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Biomarker Source | Characteristics of the Cohort | Proteomic Approach(es) | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crabb et al., 2002 [49] | Drusen and BrM | 18 controls 5 donors with AMD | Label-free LC-MS/MS | A total of 129 proteins identified. Crystallins are more frequently detected in the diseased group. |

| Alcazar et al., 2009 [50] | Exosomes from Hydroquinone-stimulated ARPE-19 cells | N.A. | SDS-PAGE coupled to LC-MS/MS Immunofluorescence | Proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation, cell junction, focal adhesion, cytoskeleton regulation and immunogenic processes. Basigin and MMP14 could be involved in progression of dry AMD. |

| Wang et al., 2009 [51] | RPE tissue, drusen and ARPE-19 cells | 12 eyes (six donors) with no history of AMD 4 eyes (2 donors) with history of AMD 8 eyes (8 donors) documented AMD | Immunoblot, ELISA and Luminex | Drusen in AMD donor eyes contain markers for autophagy (atg5) and exosomes (CD63 and LAMP2). Exosome markers are characteristic of drusen from AMD patients and co-localize in the RPE/choroid complex. |

| Yuan et al., 2010 [52] | Bruch’s membrane | 10 early/mid-stage dry AMD 6 advanced dry AMD, 8 wet AMD 25 normal control post-mortem eyes | iTRAQ (isobaric labeling DDA- LC-MS/MS) | Retinoid-processing proteins increased in early/mid dry AMD. Galectin-3 increased in advanced dry AMD. |

| Biasutto et al., 2013 [53] | Exosomes from ARPE-19 under oxidative stress conditions | N.A. | Reverse-phase assay | Identification of a subset of phosphorylated proteins including PDGFRβ, VEGFR2 and c-kit that are also detected in the vitreous of AMD patients. |

| Kelly et al., 2020 [54] | Bruch´s membrane | 3 donors with AMD | Ion mobility-based LC-MS/MS | APOE and APOB over-represented in HDL from BrM vs. plasma. |

| Flores-Bellver et al., 2021 [55] | RPE monolayers generated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived of CD34+ cord blood mesenchymal stem cells | N.A. | Label-free LC-MS/MS ELISA Immunoblot | Drusen-associated proteins exhibit distinctive directional secretion mode altered in AMD pathological conditions (e.g., chronic exposure to cigarette smoke). |

| Cai et al., 2022 [56] | RPE cells from donor´s eyes | 4 donors with AMD high-risk alleles 2 donors with AMD low-risk alleles | iTRAQ (isobaric labeling DDA- LC-MS/MS) | Exposure of high-risk donor-derived RPE cells to the serum from smokers enhances molecular pathways related to development of AMD. |

| Senabouth et al., 2022 [57] | iPSCs generated from skin fibroblasts | 43 GA 36 Controls | TMT (isobaric labeling DDA- LC-MS/MS) | GA patients present mitochondrial dysregulation characterized by an increase in Complex I levels and activity. |

| Zauhar et al., 2022 [58] | RPE and choroid fibroblasts, pericytesand endothelial cells | N.A. | Label-free LC-MS/MS | Classical complement pathway involvement more robust in retina. New cellular targets for therapies directed at complement. |

| Study | Biomarker Source | Characteristics of the Cohort | Proteomic Approach(es) | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koss et al., 2014 [59] | Vitreous humor | 73 naïve patients 15 control samples from patients with idiopathic floaters | CE-MS | Acute-phase response and blood coagulation up-regulated in AMD, Alpha-1-antitrypsin among them. |

| Nobl. et al., 2016 [60] | Vitreous humor | 128 nAMD 24 controls | CE-MSELISA | Clusterin and PEDF levels are predictive for nAMD. |

| Schori et al., 2018 [61] | Vitreous humor | 6 patients with dry AMD 10 patients with nAMD 9 patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy 9 patients with epiretinal membrane | Label-free LC-MS/MS | Oxidative stress and focal adhesion pathways modulated in dry AMD and nAMD, respectively. |

| Baek et al., 2018 [62] | Aqueous humor | 13 patients with cataract, 11 patients with dry AMD and 2 patients with no retinal diseases | DIA-MS (SWATH)ELISA | A total of 8 proteins involved in drusen development, including APOA1, CFHR2 and CLUS, are accumulated in the AH of dry AMD patients. |

| Winiarczyk et al., 2018 [63] | Tear | 8 wet AMD, 6 dry AMD and 8 controls | 2D-LC-MALDI-TOF | Graves disease carrier protein, actin cytoplasmic 1, prolactin-inducible protein 1 and protein S100-A7A are upregulated in the tear film samples isolated from AMD Patient. |

| Coronado et al., 2021 [64] | Aqueous humor | Group 1: nAMD patients: good responders to anti-VEGF) Group 2: nAMD patients (poorly/non-responsive to anti-VEGF) Group 3: patients without systemic diseases or signs of retinopathy | Label-free LC-MS/MS | A total of 39 potential disease effectors, including players of lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, inflammation and angiogenesis. VEGFR-1 is up-regulated in non-responsive patients, which could explain resistance to treatment. |

| Joo et al., 2021 [65] | Aqueous humor | 13 nAMD patients (type 1: n = 8; type 2: n = 5) and 10 controls undergoing cataract surgery with no retinal diseases | Multiplexed antibody-based array | VEGF is specifically increased in nAMD patients with type 2 CNV. |

| Rinsky et al., 2021 [66] | Aqueous humor | Discovery: 10 nAMD patients and 10 controlsValidation: 20 controls, 15 atrophic AMD and 15 nAMD patients | Intensity-based label-free quantification (MS1) Multiplex ELISA | Clusterin overrepresented in the aqueous of nAMD patients. |

| Winiarczyk et al., 2021 [67] | Tear | 15 nAMD patients 15 controls | 2D-LC-MALDI-TOF | AIF-1, ABCB1 and annexin-1 are higher in AMD. |

| Cao et al., 2022 [68] | Aqueous humor | 122 nAMD with anti-VEGF therapy | DIA-MS (SWATH) | APOB100 expression is higher in AMD vs. control. |

| Shahidatul-Adha et al., 2022 [69] | Tear and plasma | 36 eAMD 36 lAMD 36 controls | ELISA | Tear VEGF level presents high sensitivity and specificity as a predictor of the severity of the disease. |

| Tsai et al., 2022 [70] | Exosomes from Aqueous humor | 28 eyes from AMD patients (2 of them followed during Ranibizumab treatment). 25 control eyes from senile cataract patients without other ocular or systemic diseases | Label-free LC-MS/MS | APOA1, clusterin, C3 and opticin significantly accumulated in AMD. Anti-VEGF therapy progressively decreases levels of SERPINA1 and AZGP1. |

| Valencia et al., 2022 [71] | Tear | 60-patient cohort: 31 with diagnosed GA-AMD | ELISA | Upregulation of MT1A and S100A6 in GA-AMD patients. |

| Study | Biomarker Source | Characteristics of the Cohort Used for the Proteomic Study | Proteomic Approach(es) | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lip et al., 2001 [72] | Plasma | 28 “dry” AMD 50 “exudative” AMD 25 “healthy” controls | ELISA | VEGF and VWF significantly increased in AMD. |

| Sivaprasad et al., 2005 [73] | Plasma | 26 nAMD 30 eAMD 15 controls | ELISA | Elastin-derived peptides elevated in the serum of nAMD patients vs. eAMD and control subjects. |

| Tsai et al., 2006 [74] | Plasma | 17 dry AMD 42 wet CNV/AMD 18 scar/AMD64 non-AMD | ELISA | VEGF significantly increased in CNV/AMD. |

| Wu et al., 2007 [75] | Serum | 159 eAMD 38 lAMD 433 controls | ELISA | No consistent pattern of association found between AMD and circulating inflammatory markers. |

| Rudnicka et al., 2010 [76] | Serum | 81 AMD 77 controls | ELISA | FVIIc and possibly F1.2 are inversely associated with the risk of AMD. No evidence of associations between AMD and systematic markers of arterial thrombosis. |

| Carneiro et al., 2012 [77] | Plasma | 43 exudative AMD: 19 ITV ranibizumab 24 ITV bevacizumab 19 age-related controls | ELISA | No basal differences in VGEF between AMD and controls. Significant reduction in VEGF levels with intravitreal bevacizumab. |

| Gu et al., 2013 [78] | Serum | 39 neovascular AMD with single-dose ranibizumab 39 healthy controls | ELISA | No basal differences in VGEF between AMD and controls. VEGF levels significantly decrease after injection but increase later. |

| Kim et al., 2014 [79] | Plasma | 20 exudative AMD 20 healthy controls Validation: 233 case–control samples | LC-MS/MS ELISA WB | Vinculin is identified as a potential plasma biomarker for AMD. |

| Kim et al., 2016 [80] | Plasma | 90 healthy controls 49 eAMD and 87 exudative AMD | ELISA | MASP1, and especially PLPT useful as predictors of AMD progression. |

| Zhang et al., 2017 [81] | Plasma | 344 adults | Selected Reaction Monitoring | Development of a method to quantify Y402H and I62V AMD-associated variants of Complement Factor H. |

| Lynch et al., 2019 [41] | Plasma | 10 nAMD 10 GA 10 age-matched cataract controls | Aptamer-based proteomics | Higher levels of vinculin and lower levels of CD177 are found in patients with neovascular AMD compared with controls. |

| Palestine et al., 2021 [82] | Plasma | 210 iAMD 102 controls | Multiplex | CCL3 and CCL5 significantly decreased and CCL2 increased in patients with iAMD compared with controls. |

| Sivagurunathan et al., 2021 [83] | Plasma and urine | 23 controls 61 AMD | Shotgun LC-MS/MS (TMT) ELISA | SERPINA-1, TIMP-1 and APOA-1 higher in AMD. |

| Emilsson et al., 2022 [84] | Serum | Discovery: 1054 eAMD 112 GA pure 160 nAMD 183 GA + nAMD Validation: 15 subjects for each category | Aptamer-based proteomics ELISA | Determination of a set of 28 AMD-associated proteins including CFHR1, TST, DLL3, ST6GALNAC1, CFP and NDUFS4. PRMT3 proposed as predictor for progression to GA. |

| Process | Protein Biomarkers | References |

|---|---|---|

| RPE redox maintenance | CCLs | [65,82,131] |

| Crystallins | [49,51] | |

| Regulation of neovascularization | VEGF | [10,65,69,72,74] |

| VEGFR | [53,64] | |

| TIMP1 | [64,83] | |

| Opticin | [70] | |

| Metal homeostasis and ECM remodeling | S100A6 | [71] |

| CFH, CFHR | [49,62,71,81] | |

| TIMP1, TIMP3 | [64,83] | |

| Elastin | [73,103,104] | |

| MMP14 | [50,100] | |

| Lipoprotein metabolism | APOA1 | [54,62,64,70,83] |

| APOB | [54,68,113] | |

| Clusterin | [60,66,70,71,110,111] | |

| Complement cascade | C3 | [64,70] |

| CFH, CFHR | [49,62,71,81] | |

| C5 | [49,51] | |

| Clusterin | [60,66,70,71,110,111] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Quintanilla, L.; Rodríguez-Martínez, L.; Bandín-Vilar, E.; Gil-Martínez, M.; González-Barcia, M.; Mondelo-García, C.; Fernández-Ferreiro, A.; Mateos, J. Recent Advances in Proteomics-Based Approaches to Studying Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14759. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314759

García-Quintanilla L, Rodríguez-Martínez L, Bandín-Vilar E, Gil-Martínez M, González-Barcia M, Mondelo-García C, Fernández-Ferreiro A, Mateos J. Recent Advances in Proteomics-Based Approaches to Studying Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(23):14759. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314759

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Quintanilla, Laura, Lorena Rodríguez-Martínez, Enrique Bandín-Vilar, María Gil-Martínez, Miguel González-Barcia, Cristina Mondelo-García, Anxo Fernández-Ferreiro, and Jesús Mateos. 2022. "Recent Advances in Proteomics-Based Approaches to Studying Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 23: 14759. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314759

APA StyleGarcía-Quintanilla, L., Rodríguez-Martínez, L., Bandín-Vilar, E., Gil-Martínez, M., González-Barcia, M., Mondelo-García, C., Fernández-Ferreiro, A., & Mateos, J. (2022). Recent Advances in Proteomics-Based Approaches to Studying Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(23), 14759. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314759