Global Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Review and Followed Criteria: PRISMA, PICOS and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Followed Methodology per Defined Study Aim

2.2.1. Study Objectives 1 and 2

2.2.2. Study Objective 3

2.3. Keywords, Search Strategy, and Timeframe

2.4. Screened Databases/Resources and Dates of Data Collection

2.5. Data Collection Methodology and Quality Control Assessment

Quality Assessment of the Selected Papers

- Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated?

- Was the study population clearly specified and defined?

- Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%?

- Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants?

- Was a sample size justification, power description or variance and effect estimate provided?

- For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured prior to the outcome(s) being measured? * (No)

- Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed? * (No)

- For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as it related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure, or exposure measured as a continuous variable)? ** (not applicable)

- Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable and implemented consistently across all study participants?

- Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? (i.e., Was the questionnaire administered at least two times in different moments?/exposure or evaluation of independent variable).

- Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable and implemented consistently across all study participants?

- Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants? ** (not applicable)

- Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? (i.e., % of participants who did not reply to the second questionnaire; if applicable)

- Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)?

2.6. Dates of the First Administered Vaccine per Each Studied Country

2.7. Definitions: Global Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy, Contradictory Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy and Most Frequent Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy per Country or Region

- Global predictors of vaccine hesitancy: predictors identified in at least two of the selected studies (i.e., frequency of two or more).

- Contradictory predictors of vaccine hesitancy: contrary/opposite variables/predictors, which explain vaccine hesitancy in at least two countries/regions (e.g., females vs. males).

- Most frequent predictors of vaccine hesitancy per country/region: predictors that were present in at least 35% of the selected studies. The selected studies were grouped into nine countries/regions: USA, China, UK, Australia, Asiatic countries, European Union, Latin America and the Caribbean and South Africa (see Appendix A).

3. Results

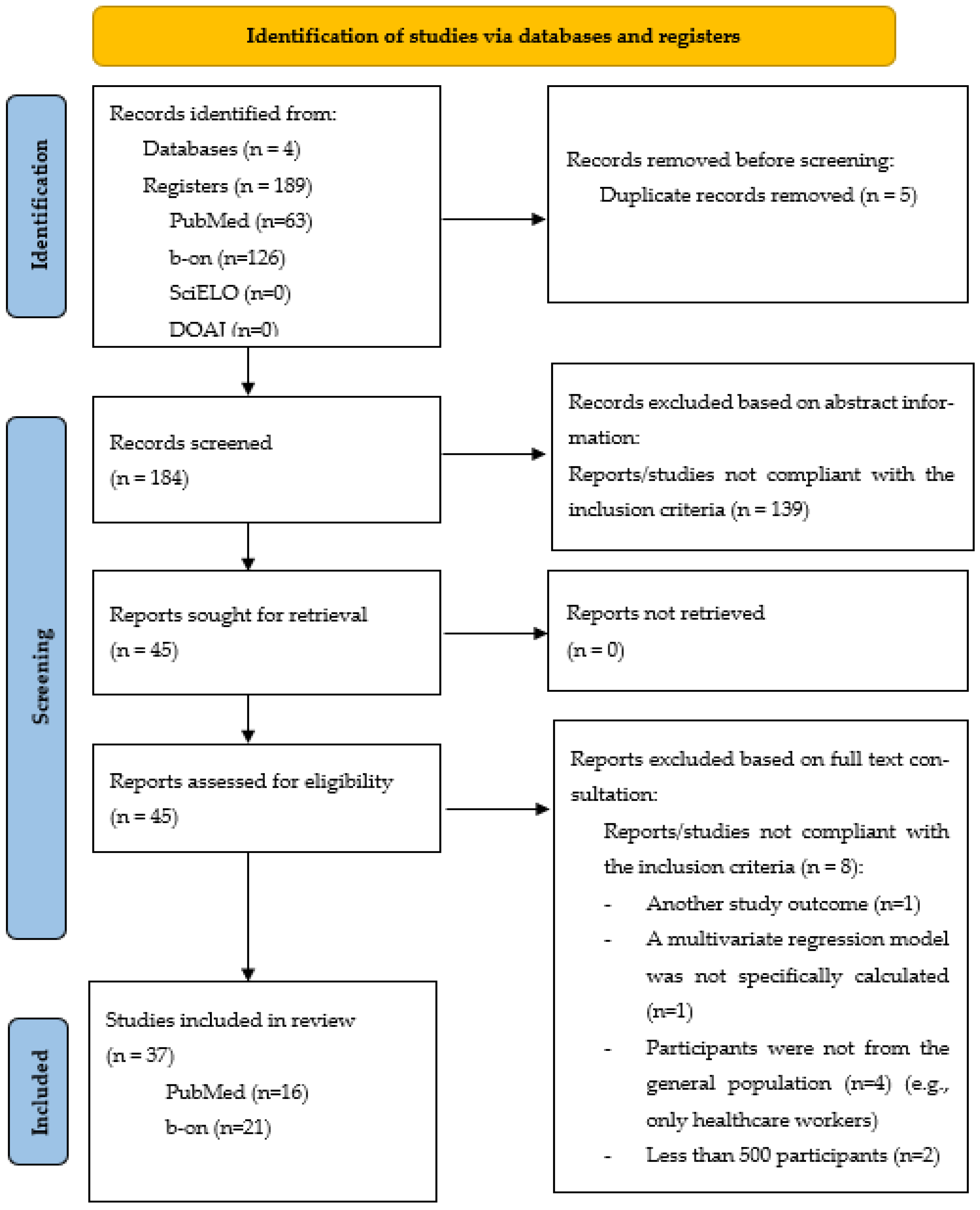

3.1. Selected Studies

3.2. Study Findings

3.2.1. Quality Control Assessment

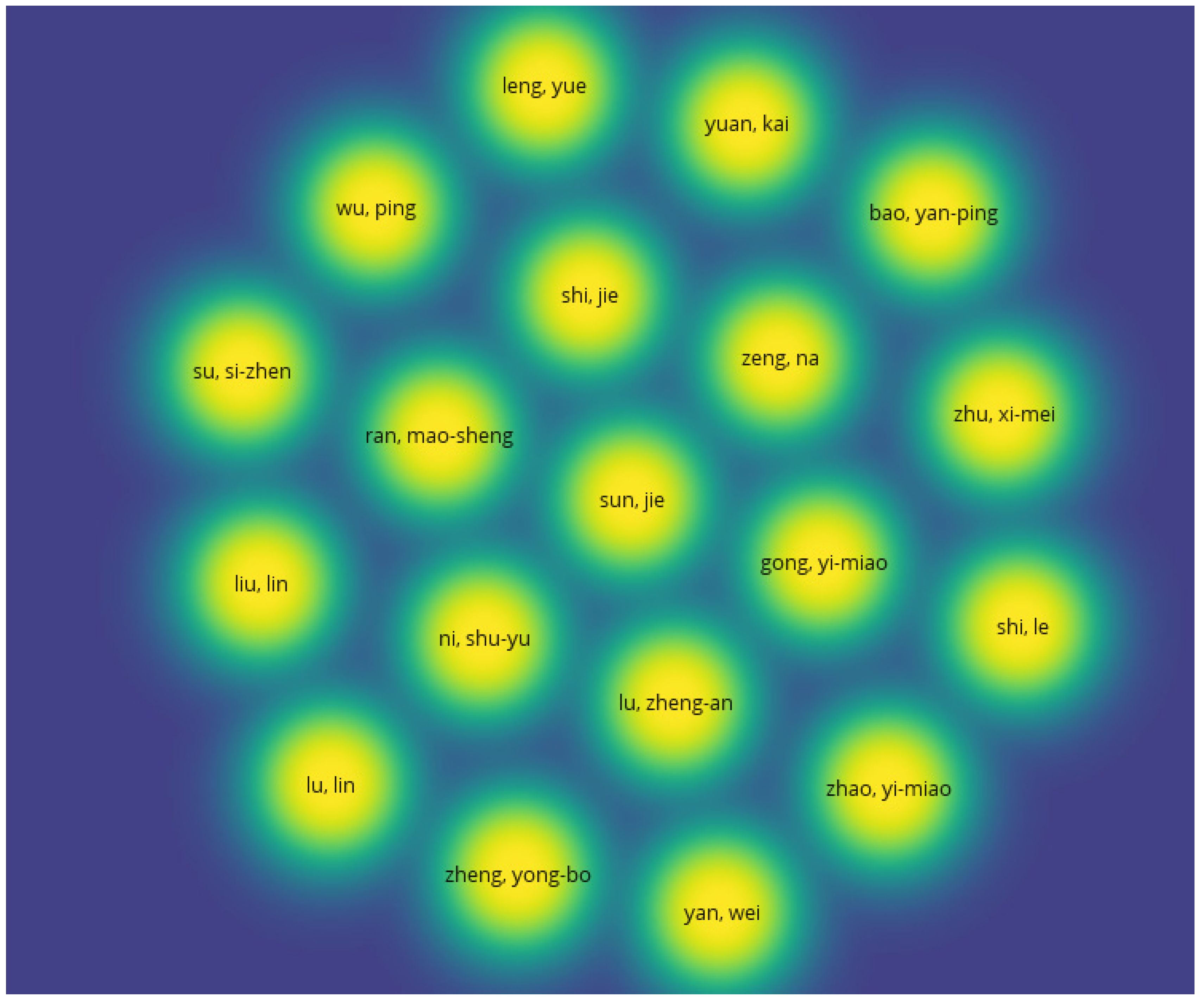

Paper Metrics and Mapping Analysis of the Journals from the Selected Papers

NHLBI Quality Assessment Tool

3.2.2. Studies Carried out before and after the Beginning of the Pandemic

3.3. Previous Similar/Related Systematic Reviews: Commonly Selected Studies

3.4. Global Predictors, Single Occurrences and Contradictory Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy

3.4.1. Global Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy

3.4.2. Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy Identified in Just One Study (Single Occurrences)

3.4.3. Contradictory Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy

Females vs. Males

Younger vs. Older

Minorities vs. Whites or Other Major Ethnic Groups

Lower Level of Education vs. Higher Level of Education

Lower Income vs. Higher Income

Not Residing in Cities or Living in Smaller Settlements vs. Residing in Cities

Unemployed vs. Employed

3.5. Most Frequent Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy per Country or Region

4. Discussions

4.1. Global Predictors, Single Occurrences and Contradictory Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy

4.1.1. Global Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy

4.1.2. Single Occurrences

4.1.3. Contradictory Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy

- Older people are more vaccine-hesitant than younger people, since the former are expected to be more susceptible to COVID-19 infection;

- Subjects with a higher level of education are more vaccine-hesitant than less educated subjects, since better-educated people are expected to be more prepared to understand the relevance of immunisation;

- Employed subjects are more vaccine-hesitant than unemployed subjects, since employed people are theoretically more likely to have more public contact;

- Citizens living in cities are more vaccine-hesitant than those living in rural areas or in smaller settlements (with a lower population density), since personal contact is less likely in rural areas.

4.1.4. Most Frequent Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy per Country or Region

4.2. Study Strengths and Contribution to the State-of-the-Art on Vaccine Hesitancy

4.3. Risk of Biases and Limitations of the Present Systematic Review

4.4. Limitations and Risk of Biases of the Selected Studies

4.5. Future Research and Purposed Intervention Measures

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Main Findings of the X Selected Studies

| Author, Year, Geographic Region, Database; Journal (Impact Factor JCR 2021 and Quartile SJR 2021) | Study Aim | Sample Size (Number of Participants that Completed the Study, i.e., Valid Respondents) and Main Characteristics * | Methods; Date of the Administration of the Questionnaire | Findings | Discussion and Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies involving more than one country | |||||

| (Kerr et al., 2021) [56] Twelve countries: Australia, China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Spain, Sweden, UK, USA Bon BMJ Open (IF JCR = 3.006; Q1) | To describe demographical, social and psychological correlates of willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. | 25,334 respondents Age (mean = 45.06); female (mean = 0.51); Conservative (mean = 3.74); general trust: experts (mean = 3.97). | Online surveys Multivariate logistic regression March and October 2020 (before the beginning of the COVID-19 vaccination roll-out). | Reported willingness to receive a vaccine varied widely across samples (63% to 88%). Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: male, not trusting in medical and scientific experts (e.g., WHO or national advisors), lower levels of worry about the COVID-19 virus, age, not being prosocial and low perceived infection risk. In particular, the strongest predictors of vaccine acceptance among the sampled countries were being a female, trust in medical and scientific experts and worry about the COVID-19 virus. | Information provided by medical and scientific experts (credible sources) seems to be determinant of vaccine acceptance. |

| (Mascherini and Nivakoski, 2022) [57] European Union Bon Vaccine (IF JCR = 4.169; Q1) | To examine COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the European Union, focusing on the role of social media use | 29,755 respondents Female (63.8%); ≥60 years (33.7%); living in a city or city suburb (39.5%); employed (49.2%); tertiary education (66.3%); lives with spouse (61.8%); children in household (34.8%); bad health (8.3%); chronic health problem (46%); close person had COVID-19 (38%). | Cross-national survey covering all 27 EU member states Multivariate regression models February and March 2021 (after the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination roll-out). | A total of 71.3% respondents were very likely or rather likely to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: men, not living in cities or city suburbs, being self-employed, unemployed or unable to work due to a long-term illness or disability, students, singles (not living with a spouse or partner), living with children in the household, tertiary education (if spending more time using social media), not reporting previous exposure to COVID-19 among close persons, viewing COVID-19 risks as exaggerated—or believing that COVID-19 does not exist (more likely to be male and in very good health), people who use social media for 3 or more hours daily, people who report social media as their main source of news. | Clear, precise and transparent messages about vaccines need to be delivered by policymakers and scientists, namely in social media. For instance, men, people in good health and those using social media as their main source of news are more likely to consider COVID-19 risks to be exaggerated (or that COVID-19 does not exist). |

| (Price et al., 2022) [58] Norway, the UK, the USA and Australia Bon Social Sciences (no IF JCR; Q2; available in Web of science and Scopus) | To examine (i) the willingness in the general population to get the COVID-19 vaccine nine months after the pandemic outbreak and (ii) the willingness to get the vaccine in relation to sociodemographic variables, whether one has experienced COVID-19 infection, concerns about health and family and trust in the information provided by authorities about the pandemic. | 3474 respondents Female (66.8%); 18–29 years (69.8%); city (70.4%); master’s/doctoral degree (72.5%); full-time or part-time employed (66.3%); infected (55.1%); trust in public information provided by authorities (79.4%). | Cross-sectional survey Logistic regression analysis 24 October and 29 November 2020 (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination roll-out). | A total of 65% respondents reported being likely or very likely to get the COVID-19 vaccine (USA 63%, UK 66.6%, Norway 69.5%, and Australia 71.1%). Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: male, younger people, not living in a city, unemployed, low education level (high school or lower), infected by COVID-19 personally or infection within their family, not declaring to be concerned about their own health and the health of next of kin and not trusting information provided by authorities. The trust in the information provided by authorities about COVID-19 is an especially relevant predictor, since a significantly higher vaccine acceptance was shown across all countries. | Information provided by authorities should be used to increase the proportion of citizens willing to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Study findings should be used in future vaccination campaigns and public health measures. |

| USA | |||||

| (Reiter et al., 2020) [59] USA PubMed Vaccine (IF JCR = 4.169; Q1) | To examine the acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among a national sample of adults in the US. | 2006 adults 43% Female; White, non-Latinx (67%); married/civil union or living with partner (51%); high school degree (29%); Conservative (33%); no health insurance (12%); underlying medical condition, yes (36%). | Online survey Multivariable relative risk regression May 2020 (Before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 69% of respondents were willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: if respondents though their healthcare provider would not recommend vaccination); Conservative (political party), lower levels of perceived likelihood of getting infected with COVID-19 in the future; lower levels of perceived severity of COVID-19 infection; lower levels of perceived effectiveness of a COVID-19 vaccine; non-Latinx Black; and higher levels of potential vaccine harms. | These findings can Help in guiding and planning the development of future public health efforts to increase the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines. |

| (Khubchandani et al., 2021) [60] USA PubMed Journal of Community Health (IF JCR = 4.371; Q1) | To conduct a comprehensive and systematic national assessment of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a community-based sample of the American adult population. | 1878 adults Females (52%), less than 40 years (63%); White (74%), non-Hispanic (81%), married (56%), employed full time (68%) and has a bachelor’s degree or higher (77%). | A multi-item validated questionnaire. Logistic regression model analysis. June 2020 (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | Likelihood of getting a COVID-19 immunisation: very likely (52%), somewhat likely (27%), not likely (15%), definitely not (7%). Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: females, lower levels of education, employed people, lower income, people with children at home, Republicans, and people who perceived the likelihood of getting infected in the next 1 year as “definitely not”. | Special attention to the groups identified in this study as vaccine-hesitant. It is recommended that evidence-based communication interventions, such as mass media strategies and/or policy measures, are defined. |

| (Ruiz and Bell, 2021) [61] USA PubMed Vaccine (IF JCR = 4.169; Q1) | To assess the impact of people’s main media source of COVID-19 information on vaccine hesitancy. | 804 English-speaking adults. Female (53.6); White race (65.3%); less than 45 years (51.6%); married/living as married (56.6%); postgraduate degree (23.3%); Democrat (31.1%); preferred media for coronavirus news (1st CNN (17.5%); 2nd Fox News (16.3%) and 3rd ABC (14.1%). | Internet survey Multiple linear regression. 15–16 June 2020 (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 62.2% of respondents were extremely or somewhat likely to get COVID-19 vaccine. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: lower general vaccine knowledge; accepting vaccine conspiracies; perceiving the severity of COVID-19 as a lower threat; no influenza vaccine uptake in the current flu season; less than 5 pre-existing health conditions that make one susceptible to COVID-19; female; an income of less than USD 120,000; party than Democrat; relying upon social media for virus information; intent to get vaccinated was lower for Fox News (57.3%) than CNN/MSNBC viewers (76.4%)) (social media virus information). | The present study contributes to guide public health experts, regarding the development of the strategies for encouraging uptake of COVID-19 vaccines. |

| (Latkin et al., 2021) [62] USA PubMed PLoS One (IF JCR = 3.752; Q1) | To examine the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and factors associated with vaccine intentions. | 1056 respondentsFemale (70.1%); more than 59 years (43.3%); White (69.%); some college and above (80.5%); employed (56.7%); USD 50,000 or more (57.1%); not at all worried about COVID-19 infecting family or self (7.2%); Conservative (28%). | A national panel survey (telephone and web) Multinominal logistic regression 14 and 18 May 2020 (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 53.6% participants reported intending to be vaccinated. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: black and Hispanic; females; younger respondents; and political party (Conservative). More vaccine-hesitant respondents were significantly less likely to report that they engaged in the COVID-19 prevention behaviours (e.g., wearing masks). | Campaigns should address study findings, i.e., assess in greater detail the vaccine concerns of Blacks, Hispanics and women to tailor programs. |

| (Nguyen et al., 2021) [63] USA Bon Vaccine (IF JCR = 4.169; Q1) | To understand disparities in vaccine intentions and reasons for vaccine hesitancy. | 459,235 respondents Female (51.6%); ≥65 years (21.7%); White (62.5%); some college or college graduate (47.7%); <USD 35,000 (19.3%); insured (91.7%). | Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey Logistic regression Models 6 January –29 March 2021 (After the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | On average, 62% of respondents reported being willing to receive at least one COVID-19 vaccine. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: non-Hispanic Black adults with lower income (<USD 35,000) and younger age (18–49 years). | Interventions and recommendations to improve vaccination coverage and confidence should be designed to target some populational groups, such as younger and lower income racial/ethnic minority groups. |

| (Omaduvie et al., 2021) [64] USA Bon Population Medicine (no impact factor JCR; indexed in Scopus) | To examine whether the wide variations in the burden of COVID-19 incidence and mortality rates across states are associated with vaccine hesitancy.** | 68348 respondents Female (51.6%); age (mean = 47.2 years); non-Hispanic White (62.6%); married (55.1%); college degree (26.7%); annual household income (USD) less than 25,000 (14.4%). | Household Pulse Survey Multivariable Poisson regression model. 6–18 January 2021 (After the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 23.5% reported vaccine hesitancy. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: being Black, having already tested positive for COVID-19, female, and living in a Republican-“leaning” State. | Knowledge of state-specific information can be useful to define specific intervention programs. |

| (Hao et al., 2022) [65] USA Bon Vaccine (IF JCR = 4.169; Q1) | To understand public behaviour regarding COVID-19 vaccination. | Approximately 6000 respondents Females (59%); age (mean =53); White (78%); married (56%); employed (51%); Democrat (30%); vaccinated for the coronavirus (72%). | National survey Multilevel logistic regression 9 June and 21 July 2021 (after the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period ). | On average, around 72% of respondents declared to have gotten vaccinated for the coronavirus. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: not trusting in President Biden, lower proportion of their family or close friends have already received it, people who do not have a positive view of the COVID-19 vaccine, lower age, White, not married. | Study finding contribute to understand the profile of citizens who do not accept the vaccine, which can be helpful to design new programs/interventions. |

| China | |||||

| (Dong et al., 2020) [66] China PubMed Health expectations (IF JCR = 3.318; Q1) | To examine how factors related to vaccine characteristics, their social normative influence and the convenience of vaccination can affect the public’s preference for the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine in China. | 1236 respondents Female (50.89%); age (mean = 30.27; SD = 7.66); unmarried (38.83%); unemployed (0.97%); education: tertiary and above (85.76%). | Survey: an online discrete choice experiment A mixed logit regression model. June and July 2020 (before the beginning of the COVID-19 vaccination period). | Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: lower efficacy (less than 70% or 90%); shorter duration of action (less than 12 or 18 months); more adverse events, number of shots (more than one injection); production place (non-imported vaccines); and price (higher price). | Identified preferences should be used to develop COVID-19 vaccination programs in China. |

| (Wang et al., 2020) [67] China PubMed Vaccines (IF JCR = 4.961; Q1) | To evaluate the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination in China and give suggestions for vaccination strategies and immunisation programs accordingly. | 2058 adults Female (54.2%); 41 or more years (32.1%); more than high school (61.8%); married (67.3%). | Anonymous cross-sectional Survey (online) Multivariate logistic regression March 2020 (before the beginning of the COVID-19 vaccination period). | 91.3% respondents reported that they would accept COVID-19 vaccination after the vaccine becomes available Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: female, unmarried, perceiving a lower risk of infection, not being vaccinated against influenza in the past season, not believing in the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines or not valuing doctor’s recommendations. | Education and communication strategies from heath authorities as well as immunisation programs that remove barriers (e.g., vaccine price and vaccination convenience) seem to be important measures to alleviate public concerns aboutvaccine safety. |

| (Chen et al., 2021) [68] China PubMed Hum. Vaccine Immunother. (IF JCR = 4.526; Q1) | To understand the willingness and determinants for the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine among Chinese adults. | 3195 adults Female (63.6%); ≥45 years (13.5%); master’s and above (32.6%); poor health (0.4%); chronic disease, yes (10.4%). | A cross-sectional survey: an online questionnaire Multivariable logistic regression May to June 2020 (before the beginning of the COVID-19 vaccination period). | 83.8% were willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: the risk of vaccines, complacency in health, and low frequency attention to relevant COVID-19 information. | COVID-19 vaccine information (e.g., safety and efficacy issues) should be propagated to ensure vaccination acceptance and coverage. |

| (Zhao et al, 2021) [69] China Bon Vaccines (IF JCR = 4.961; Q1) | To assess the willingness of the general population to receive COVID-19 vaccines and identify factors that influence vaccine hesitancy and resistance. | 34,041 respondents Female (53.8%); 18–39 years (60.9%); urban (79.1%); college degree or higher (79.2%); married (77.5%); confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection (0.3%); quarantine, no (88.6%); chronic diseases (9.1%); normal symptoms of anxiety (78.9%). | Online survey Multinomial logistic regression analyses 29 January 2021 to 26 April 2021 (40.4%); 1–31 March 2021 (51.1%); and 1–26 April 2021 (8.5%) (after the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination). | 55.3% of respondents were willing to get vaccinated. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: female, young and middle-aged, high income, residing in cities and perceived low risk of infection. Vaccine acceptance increased over time, with geographical discrepancies in vaccine hesitancy between provinces. | Tailored public health programs, measures or interventions should consider study findings, such as differences in the profile of vaccine hesitancy between different regions. |

| UK | |||||

| (Williams et al., 2020) [70] UK PubMed Vaccines (IF JCR = 4.961; Q1) | To assess key sociodemographic variables and intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine. | 3436 people (time 1) A total of 2016 people (time 2; 2 months later) Age (≥50 years (45.9% t1 and 51.5% t2); female (79.1% t1 and 82.1% t2); White (96.3 t1 and 96.7 t2); and <£16,000(9.7% t1 and 9.7% t2). | Two-wave online survey (prospective study) Logistic regression analyses Time 1 (t1): from 20 May to 12 June 2020, weeks 9–12 of national lockdown. Time 2 (t2): Two months later (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination). | 74% respondents reported being willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: non-white (i.e., Black, Asian and minority ethnic); low-income levels; low education levels; and no underlying medical conditions/not shielding. | Mass media and social marketing interventions should address the concerns of subpopulations and diverse communities. |

| (Sherman et al., 2021) [71] UK PubMed Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics (IF JCR 4.526; Q1) | To investigate factors associated with the intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19. | 1500 adults Females (51%); White (84.5%); degree equivalent or higher (52.6%); unemployed (37.1%); extremely clinically vulnerable – respondent (29.7%); influenza vaccination last winter, yes (32.3%). | Cross-sectional survey. Linear regression analyses. 14 and 17 July 2020. (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 64% respondents declared themselves very likely to become vaccinated against COVID-19. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: younger age; not being vaccinated against influenza last winter; lower perceived risk of getting COVID-19; a less positive general COVID-19 vaccination beliefs and attitudes; stronger beliefs that the vaccination would cause side effects or be unsafe; lower perceived information sufficiency to make an informed decision about COVID-19 vaccination; an higher endorsement of the notion that only people who are at risk of serious illness should be vaccinated for COVID-19. | Findings should be used to design COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, which could explain the risk of COVID-19 to third parties and necessity for everyone to be vaccinated. |

| (Sherman et al., 2022) [72] UK Bon Public Health (IF JCR = 4.984; Q1) | To investigate the factors associated with the intention to get the COVID-19 vaccination following initiation of the UK national vaccination programme. | 1500 adults Female (51%); White (84.6%); degree equivalent or higher (54.5%); full-time employment (43.3%); household incomed under GBP 10,000 (6.3%); influenza vaccination last winter (30.5%); extremely clinically vulnerable (22.9%) and extremely clinically vulnerable e other(s) in household (16.9%). | Online cross-sectional survey Linear regression analyses 13–15 January 2021 (after the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 73.5% of participants reported being likely to be vaccinated against COVID-19 Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: not having been/intending to be vaccinated for influenza last winter/this winter; lower beliefs about social acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine; a lower perceived need for vaccination; adequacy of information about the vaccine; and stronger beliefs that the vaccine is unsafe. | Continued engagement with the public regarding the need COVID-19 vaccination is recommended. For instance, safety issues should be highlighted. |

| Australia | |||||

| (Seale et al., 2021) [73] Australia PubMed BMC Infectious Diseases (IF JCR = 3.667; Q1) | To understand the public perceptions regarding a future COVID-19 vaccine in Australia. | 1420 Australian adults (18 years and older) Male (47.7%); less than 50 years (56.6%); not working (41.6%); university degree (38.1%); chronic health condition (25.6%). | A national cross-sectional online survey. Logistic regression model analysis. 18 and 24 March 2020 (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 80% (n = 1143) agreed with the statement that getting vaccinated against COVID-19 would be a good way to protect themselves against infection. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: males, 18–29 year olds, not self-reporting chronic disease, not having private health insurance, and not internationally travelling in 2020. | These findings should support governmental political health measures to identify the appropriate strategies that will support citizens in getting COVID-19 vaccines. |

| (Alley et al., 2021) [74] Australia PubMed International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (IF JCR = 4.614; Q1) | To determine whether willingness to vaccinate changed in the repeated sample and to determine whether willingness to vaccinate was associated with demographics, chronic disease or media use. | 2343 Australian adults (both surveys) 55 years old (46%); female (66%), bachelor’s degree or higher (60%); a chronic disease (48%); more than 3 h per day: social media (41%) vs. traditional media (24%). | Two surveys A generalized linear mixed model (first objective) and a multinominal logistic regression (second objective) April and August 2020 (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | Willingness to be vaccinated: April (87%) and August (85%). Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: people with a certificate or diploma; infrequent users of traditional media; women. | Strategies to promote COVID-19 vaccination should target women, and people with a certificate or diploma, via non-traditional media channels. |

| (Attwell et al., 2021) [75] Australia PubMed PloS One (IF JCR = 3.752; Q1) | To identify factors that differentiate those who are undecided from those who are either willing or unwilling to accept a prospective COVID-19 vaccine. | 1313 adults Female (60%); mean age; 58 (SD = 13.20); parents with children living at home (31%). | Online survey Multinomial logistical regression May 2020 (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 65% were willing to vaccinate, with 27% being in the “maybe” category. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy (respondents were more likely to be in the COVID-19 vaccine “maybe” than ”yes” group): perceived COVID-19 to be less severe; had less trust in science; were less willing to get a flu vaccine and were female. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy (respondents were more likely to be in the COVID-19 vaccine “no” than “maybe” group): they did perceive COVID-19 to be a hoax | The dimension of the undecided group about receiving a COVID-19 vaccine (over a quarter (27%)) suggests that this group will be important to the effective nationwide rollout of the vaccine. Research to understand the motivation of undecides is urgently needed. |

| Asia | |||||

| (Albahri et al., 2021) [76] United Arab Emirates Bon Frontiers in Public Health (IF JCR = 6.461; Q1) | To evaluate the current vaccine hesitancy in a segment of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) general public and its associated factors. | 2705 respondents Female (72.5%); 44 or less years (74.2%); Emirati (69.8%); postgraduate (21.5%); employed (58.3%); more than two adults in the household (82.3%); at least one child in the household (80.1%); infected with COVID-19 (3.5%); or flu vaccine in the last 2 years, yes (26.9%). | Online cross-sectionalMultivariable logistic regression analysis 14 to 19 September 2020 (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 60.1% respondents were willing to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: female, Emiratis, older participants, retired, unemployed, postgraduate, not receiving the influenza vaccine within the past 2 years, not believing in the seriousness of the COVID-19 situation or the vaccine’s ability to control the pandemic, perceiving the effect of the disease to have a lower effect on one’s personal health, not believing that the public authorities are handling the pandemic adequately. Vaccine safety, side effects and the belief that one needs to develop immunity naturally were the top reasons for vaccination hesitancy. | Initiatives are recommended to fight vaccine misinformation. For instance, providing information on vaccine safety and efficacy (e.g., side effects or highlighting the advantages of getting herd immunity through vaccination over natural acquired immunity). |

| (Alremeithi et al., 2021) [77] United Arab Emirates Bon Frontiers in Public Health (IF JCR = 6.461; Q1) | To assess The knowledge, attitude and practices toward infection by SARS-CoV-2, including vaccine acceptance. ** | 1882 people Females (80.7%), younger than 40 (67.7%), males (19.3%), UAE nationals (78.2%), healthcare worker (9.9%), held a bachelor’s degree or above (54.5%), healthy (73.3%). | Questionnaire Multivariate linear regression 4–14 April 2020 over a period of 10 days. (Before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period.) | 89% respondents agreed that SARS-CoV-2 infection would be successfully controlled. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: less likely to wear masks, older age, UAE nationals, lower knowledge scores on SARS-CoV-2 infection and females. | Intensification of awareness programs and good practices were recommended. |

| (Harapan et al., 2020) [78] Indonesia PubMed Frontiers in Public Health (IF JCR = 6.461; Q1) | To assess the acceptance of a 50- or 95%-effective COVID-19 vaccine, when it becomes available in southeast Asia, among the general population in Indonesia. | 1359 respondents Female (65.7%); less than 50 years (94.8%); university graduate/postgraduate (66.1%); single (55.9%). | A cross-sectional online survey A logistic regression model. 25 March and 6 April 6 2020 (before the beginning of the COVID-19 vaccination period). | 93.3% of respondents would like to be vaccinated (95% effectiveness) and 67.0% of respondents would like to be vaccinated (50% effectiveness). Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy (first scenario, 95% COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness): not being a healthcare professional, and lower perceived risk of getting infected were associated. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy (second scenario, 50% COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness): being a healthcare professional was the only characteristic associated with vaccine acceptance. | Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine was influenced by their effectiveness in the present study. It seems governments need to address the perceived risk in communities and more vaccination strategies/measures for lower effective vaccines. |

| (Al-Mohaithef and Padhi, 2020) [79] Saudi Arabia PubMed Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare (IF JCR = 2.919; Q1) | To assess the prevalence of the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine and their determinants among people in Saudi Arabia. | 992 respondents Female (65.83%); above 45 years (5%); married (51.61%); Saudi (82.06%); graduate (50.1%); unemployed (39.72%). | Questionnaires (social media platforms and email) Logistic regression analysis. Timeframe was not detailed. | 64.7% showed interest in accepting the COVID-19 vaccine. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: people with less than 45 years; non-married; lower perceived risk of being infected; less trust in the health system. | Addressing sociodemographic determinants as well as tailored health education interventions to promote COVID-19 vaccination, |

| (El-Elimat et al., 2021) [80] Jordan Bon PLoS One (IF JCR = 3.752; Q1) | To investigate the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines and its predictors in addition to the attitudes towards these vaccines among the public in Jordan. | 3100 respondents Females (67.4%); >35 years (34.3%); married (49.8%); with children (46.1%); postgraduate (21.4%), health-related area (53.8%); employed (46.4%); insured (78.1%); smoker (21.9%); chronic disease (13.4%); influenza vaccine (9.4%); or infected with COVID-19 (37.1%). | Online, cross-sectional, and self-administered questionnaire Logistic regression analysis November 2020 (before the beginning of vaccination period). | 37.4% declared that they would accept COVID-19 vaccines Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: females, not receiving the seasonal influenza vaccine, believing that vaccines are not safe, not being available to pay these vaccines, above 35 years old, employed, believing that there was a conspiracy behind COVID-19, not trust in any source of information on COVID-19 vaccines | Study finding should be considered in informative vaccination campaigns, such as to offer transparent information on the safety and efficacy of vaccines (e.g., production technology). |

| (Green et al., 2021) [81] Israel Bon Israel Journal of Health Policy Research (IF JCR = 2.465; Q1) | To assess ethnic and sociodemographic factors in Israel associated with attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines prior to their introduction. | 957 adults 55% Females; Jews (63%); Arabs (37%); single (22.6%); academic degree (58.8%); religious (20.4%). | Cross-sectional survey During October 2020 (before the beginning of vaccination period). | People who want to be vaccinated immediately: men (27.3% of the Jewish and 23.1% of the Arab respondents) and women (13.6% of Jewish and 12.0% of Arab respondents). Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: lower level of education, the belief that the government restrictions were too lenient, the frequency of socialising prior to the pandemic (goes out frequently), Arabs and being female. | Besides ensuring an effective communication to the general population, vaccine promotion campaigns should be designed to effectively communicate to target groups. |

| (Khaled et al., 2021) [82] Qatar Bon Vaccines (IF JCR = 4.961; Q1) | To estimate the prevalence and identify potential determinants of vaccine willingness: acceptance (strongly agree), resistance (strongly disagree) and hesitance (somewhat agree, neutral, somewhat disagree). | 1038 respondents Female (31.7%); 40+ years (42.4%); married (73.3%); employed (76.8%); Arab (55.8%); lives with others (83.1%); chronic disease, Yes (25.8%); COVID-19 infection (8.2%); quarantine status, yes (22.1%); very concerned with COVID-19 infection (32.9%). | Phone survey Bivariate and multinomial logistic regression modelsDecember 2020 and January 2021 (before and after the beginning of the COVID-19 vaccination period). | 42.7% of respondents declared that they were willing to be vaccinated. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: female gender, Arab ethnicity, migrant status/type and vaccine side effects. | Study findings should be used to define tailored public health programs, measure, or interventions. |

| (Qamar et al., 2021) [83] Pakistan Bon Cureus (no impact factor; paper also available in PubMed) | To assess the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine among the general public in Pakistan. | 936 respondents Female (59.6%); 18–19 years (38.4%); bachelor’s or master’s degree (84.8%); unemployed (15.9%); <10,000 (in Pakistani rupees) (5.6%); married (22.3%); healthcare workers or medical students (46%); presence of COVID-19 infection in family or friends (45.6%); comorbidities (13.9%). | Questionnaire Logistic regression analysis January 2021 to February 2021 (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 70% agreed to be vaccinated if recommended. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: female gender, not being a healthcare worker, not being a medical student, no COVID-19 infection in family or friends, not trusting in the reliability of media sources regarding COVID-19, not trusting in the national government to control the pandemic and not believing that COVID-19 can be debilitating and dangerous to health. | These finding should be used to define information interventions. For instance, disseminating credible information through healthcare workers. Government officials, social media influencer channels or media outlets. |

| (Wong et al., 2021) [84] Hong Kong PubMed Vaccine (IF JCR = 4.169; Q1) | To examine the factors associated with acceptance of vaccine based on (1). constructs of the Health Belief Model (HBM), (2). trust in the healthcare system, new vaccine platforms and manufacturers and (3). self-reported health outcomes. | 1200 respondents (adults) Female (71.3%); ≥65 years (46.8%); married (77.5%); education: tertiary or above (22.9%); unemployed (3%); chronic conditions (51.4%). | Random telephone survey Multivariate logistic regression 27 July 2020 to 27 August 2020 (before the beginning of the COVID-19 vaccination period). | 42.2% of respondents indicated acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: lower perceived severity (severity and consequences of having COVID-19 by 4 items); lower perceived benefits of COVID-19 vaccine (value or efficacy of receiving COVID-19 vaccine by 4 items); lower cues to action (triggers for receiving COVD-19 vaccination by 4 items, including recommendations by the government, physicians, family members and friends, respectively); lower self-reported negative health outcomes (measured by the presence of chronic conditions and the self-report health-related quality of life (HRQoL)) and lower trust in healthcare system or vaccine manufacturers. | Study findings are relevant formulation and implementation of vaccination strategies. |

| (Hanna et al., 2022) [85] Lebanon Bon Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice (no IF JCR; Q1; indexed in Scopus) | To assess the COVID-19 vaccines’ acceptance and related determinants in the Lebanese population. | 1209 respondents Females (67.1%); living in rural area (25.9%); single (41.4%); living in the same household with children (44.8%); advanced degree (38.9%); employed (74.7%); obese (14.2%); allergies to medication (11.7%); no previous COVID-19 infection (79.4%). | Online questionnaire via social media platforms Binary logistic regression 16 February through 25 February 2021 (Before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 63.4% reported they would accept COVID-19 vaccination. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: lower general vaccine knowledge index, living in a rural residential area, not having hypertension, having a food allergy, lower fear of experiencing COVID-19 infection and not receiving or not wanting to receive influenza vaccine. | Education and awareness programs are needed to improve knowledge about COVID-19 infection and vaccination, such as among residents of rural areas. |

| (Hwang et al., 2022) [86] South Korea Bon Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics (IF JCR 4.526; Q1) | To investigate (1) the prevalence and reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, (2) subgroups that had higher rates of vaccine hesitancy and (3) vaccine hesitancy predictors. | 13,021 adults Female (50.2%); 20–39 years (33.5%); spouse (71.5%); college graduate (57.9%); employed (67.3%); good health status (94.6%); or no religion (71.5%). | National survey Logistic multivariate regression October to December 2020 (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 60.2% of the participants were not vaccine-hesitant. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: lack of confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine, less or no fear of COVID-19, unstable job status, decreased/lower family income, experienced worsening health status during pandemic, younger age, no religious affiliation and political conservatism | Identified predictors variables should be considered in future studies. |

| European Union | |||||

| (Prati et al., 2020) [87] Italy PubMed Health Education Research (IF JCR = 2.221; Q2) | To determine the extent to which Italian people intend to receive a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 and to investigate its associations with worry, institutional trust and beliefs about the non-natural origin of the virus. | 624 adults Women (54%); aged between 18 and 72 years (average = 32.31; SD = 12.69; employed (52.4%); ethnic minority group (4.0%). | Questionnaire: online platform. Multinomial logistic regression Model. April 2020. (Before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination). | 75.8% respondents intended to receive a vaccine. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: a lower level of worry to health risks; a lower level of institutional trust in Italian government, Ministry of Health and physicians and declaring to not know about the non-natural origin of the virus. | Trust, conspiracy beliefs and worry should be considered when designing new vaccination programs. |

| (Bagić et al., 2022) [88] Croatia Bon Croatian Medical Journal (IF JCR = 2.415; Q3) | To assess the determinants and reasons for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine hesitancy in Croatia. | 758 respondents Female (58.2%); 45 or more years (62.8%); bachelor’s, master’s degree or higher (45.4%); settlement size up to 10000 (46.4%); children in the household (0–17) (34.1%); Trust in the government (40.9%); or assessment of SARS-CoV-2 virus infectionrisk—small or no risk (23.3%). | A sociological surveyBinary logistic regression 4 March and 11 April 2021 (after the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 63.9% declared they would receive a COVID-19 vaccination. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: women, younger age groups (especially 25–34 year olds), persons residing in households with children, smaller settlements, persons with lower levels of education, perceiving infection as a low risk or low levels of trust in the five main actors responding to the COVID-19 pandemic (the National Civil Protection Headquarters, government, healthcare system, scientists-researchers and media). | Study finding should be considered when designing informative vaccination campaigns. |

| Latin America | |||||

| (Carnalla et al., 2021) [89] Mexico Bon Salud Publica de Mexico (IF JCR 2.259; Q3) | To estimate the willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 (acceptance) in the Mexican population and to identify socioeconomic factors associated with vaccine hesitancy and refusal. | 10,796 respondents Female (54.5%); 40 or more years (46.1%); elementary school (30.8%); low socioeconomic level (33.3%); unemployed (29.6%); chronic disease, yes (19.9%). | Data from the COVID-19 National Health and Nutrition Survey Multinomial logistic regression August to November 2020 (before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 62.3% declared they would accept COVID-19 vaccination Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: female, older age, lower educational level, lower socioeconomic status and working in the informal sector. | National campaigns on COVID-19 vaccination should target the more vaccine-hesitant subgroups. |

| (Moore et al., 2021) [90] Brazil Bon Vaccine (IF JCR = 4.169; Q1) | To know the vaccine hesitancy profile in Brazil. | 173,178 respondents Females (67.1%); ≥40 years (70.6%); White (71%); completed secondary or more (81.8%); ≤USD 197.17 (5.9%); children, yes (64.2%). | Anonymous online survey Multivariate logistic model 22 to 29 January 2021 (after the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 10.5% of respondents were vaccine-hesitant. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: assigning importance to the vaccine´s efficacy, fear of adverse reactions, assigning importance to the vaccine´s country of origin, male gender, having children, 9 years of schooling or less, living in the Central-West region, age ≥ 40 years, monthly income <USD 788.68., White, not residing in state capital, less fear of catching COVID-19, no family member died or admitted to ICU for COVID-19. | The identified explanatory variables can facilitate the elaboration of communication strategies to increase vaccine adherence, although the global vaccine hesitancy was low. |

| Caribbean | |||||

| (De Freitas et al., 2021) [91] Trinidad and Tobago Bon Lancet Regional Health Americas (without if JCR, launched July 2021, indexed in PubMed) | To evaluate public trust in information sources, confidence in institutions and COVID-19 vaccine willingness in Trinidad and Tobago. | 615 respondents Female (66%); 18–29 years (53.8%); university or higher education (84.6%); healthcare professional (31.7%); chronic illness, yes (11.7%). | Online survey Binomial logistic regression 10 November to 7 December 2020 (after the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 62.8 % of participants declared that they would get the COVID-19 vaccine. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: not trusting in medical sectors to manage COVID-19, not believing that everyone should be vaccinated according to the national immunisation schedule and not willing to get flu vaccines. | Study findings may be used to design and prioritise future intervention areas. |

| Africa | |||||

| (Kollamparambil et al., 2021) [92] South Africa Bon BMC Public Health (IF JCR = 4.169; Q1) | To assess the level of COVID19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa, identify the socioeconomic patterns in vaccine hesitancy and highlight insights from the national survey that can inform the development of a COVID-19 vaccination acceptance communication campaign. | 4440 respondents Age, years (mean = 40.47); minimum = 0; maximum = 1: chronic illness (mean = 0.168); COVID-19 awareness (mean = 0.096); male (mean = 0.482); married/with partner (mean = 0.479); urban (mean = 0.76). | Nationally representative National Income Dynamics Study—Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM) survey Logistic regression models 2–28 February 2021 and March 2021 (before and after the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination period). | 55% of the population had a strong acceptance of the vaccine. Explanatory variables of vaccine hesitancy: lower perceived risk of infection, lower perceived efficacy of vaccine, lower awareness of COVID19-related information, lower income, non-black African population group (denial non-black African, religious), the young, less educated and those without partners. | Clearer information on the risk messaging on COVID-19 vs. efficacy and safety of the vaccines. Information campaigns should target the identified groups. |

References

- WHO. COVID-19 Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Worldindata. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Worldometers. Current World Population. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/ (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- WHO. WHO SAGE Roadmap for Prioritizing Use of COVID-19 Vaccines. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/21-01-2022-updated-who-sage-roadmap-for-prioritizing-uses-of-covid-19-vaccines (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Khetan, A.K.; Yusuf, S.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Szuba, A.; Orlandini, A.; Mat-Nasir, N.; Oguz, A.; Gupta, R.; Avezum, A.; Rosnah, I.; et al. Variations in the financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across 5 continents: A cross-sectional, individual level analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 44, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, F.; Kodjamanova, P.; Chen, X.; Li, N.; Atanasov, P.; Bennetts, L.; Patterson, B.J.; Yektashenas, B.; Mesa-Frias, M.; Tronczynski, K.; et al. Economic Burden of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Clin. Outcomes Res. CEOR 2022, 14, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Vaccine wagers on coronavirus surface protein pay off. Science 2020, 370, 894–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Bio-Med. Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicine Agency. COVID-19 Vaccines: Authorized. 2022. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/vaccines-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines-authorised#authorised-covid-19-vaccines-section (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Aschwanden, C. Five reasons why COVID herd immunity is probably impossible. Nature 2021, 591, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Qin, C.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Effectiveness and safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in real-world studies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2021, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadas, S.M.; Vilches, T.N.; Zhang, K.; Wells, C.R.; Shoukat, A.; Singer, B.H.; Meyers, L.A.; Neuzil, K.M.; Langley, J.M.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; et al. The Impact of Vaccination on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreaks in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 2257–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Vaccines. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/easy-to-read/vaccines-are-important.html (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- MacDonald, N.E.; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. The Top 10 Global Health Threats for 2019, according to the WHO. Available online: https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/top-health-threats-2019/?template=next&gclid=CjwKCAjwp7eUBhBeEiwAZbHwkckEgf_dLGZnYPG37o4J23ABGTTUGFtoS3Wurjv3AvNrcL6On1HiVhoCpakQAvD_BwE (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Rothman, A.J.; Leask, J.; Kempe, A. Increasing vaccination: Putting psychological science into action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2017, 18, 149–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Block, S.; Sood, S. What Determines Vaccine Hesitancy: Recommendations from Childhood Vaccine Hesitancy to Address COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiysonge, C.S.; Ndwandwe, D.; Ryan, J.; Jaca, A.; Batouré, O.; Anya, B.M.; Cooper, S. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19: Could lessons from the past help in divining the future? Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; Jin, H.; Lin, L. Vaccination against COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of acceptability and its predictors. Prev. Med. 2021, 150, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, D.N.; Biswas, M.; Islam, E.; Azam, M.S. Potential factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir-Behghadami, M.; Janati, A. Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) design as a framework to formulate eligibility criteria in systematic reviews. Emerg. Med. J. 2020, 37, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PRISMA. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020. Available online: www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- Garner, P.; Hopewell, S.; Chandler, J.; MacLehose, H.; Schünemann, H.J.; Akl, E.A.; Beyene, J.; Chang, S.; Churchill, R.; Dearness, K.; et al. When and how to update systematic reviews: Consensus and checklist. BMJ 2016, 354, i3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubMed. PubMed.gov US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health. 2020. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- DOAJ. Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). 2020. Available online: https://doaj.org/ (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- SciELO. Scientific Electronic Library Online. 2020. Available online: https://scielo.org/ (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- b-on. Biblioteca do Conhecimento online. Available online: https://www.b-on.pt/ (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Clarivate. Web of Science. Available online: https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science/ (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- SJR. Scimago Journal & Country Rank. Available online: https://www.scimagojr.com/ (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- VOSviewer. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/ (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Ma, L.-L.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.-H.; Huang, D.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.-T. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- TGA. TGA Provisionally Approves Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine for Use in Australia. 2021. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/news/tga-provisionally-approves-pfizerbiontech-covid-19-vaccine-for-use-in-australia (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- ANVISA. Brazil Approves Emergency Use of Vaccines against COVID-19. 2021. Available online: https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/en/saude/noticia/2021-01/brazil-approves-emergency-use-vaccines-against-covid-19 (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Press Conference of the Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council (31 December 2020). Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/gwylflkjz143/index.htm (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- HKFP. HKFP Guide: Receiving a COVID-19 Vaccine in Hong Kong. 2022. Available online: https://hongkongfp.com/2022/01/06/hkfp-guide-receiving-a-covid-19-vaccine-in-hong-kong/ (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Embassy of Republic of Indonesia. Indonesia Launches First COVID-19 Vaccination Program. 2021. Available online: https://kemlu.go.id/madrid/en/news/10666/indonesia-launches-first-COVID-19-vaccination-program (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Rosen, B.; Waitzberg, R.; Israeli, A. Israel’s rapid rollout of vaccinations for COVID-19. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, H.; Kaiki, Y.; Sugiyama, A.; Nagashima, S.; Kurisu, A.; Nomura, T.; Omori, K.; Akita, T.; Shigemoto, N.; Tanaka, J.; et al. Adverse reactions to the BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 2022, 28, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anadolu Agency. Jordan Begins COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout. 2021. Available online: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/latest-on-coronavirus-outbreak/jordan-begins-covid-19-vaccine-rollout/2108497# (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Omeish, H.; Najadat, A.; Al-Azzam, S.; Tarabin, N.; Abu Hameed, A.; Al-Gallab, N.; Abbas, H.; Rababah, L.; Rabadi, M.; Karasneh, R.; et al. Reported COVID-19 vaccines side effects among Jordanian population: A cross sectional study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 1981086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiri, A.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Alkhalifa, M.; Al Duhailan, H.; Al Qahtani, S.; Abu Dawas, R.; El Seoudi, A.A.; Alomran, N.; Abu Omar, O.; Alotaibi, N.; et al. Launching COVID-19 vaccination in Saudi Arabia: Lessons learned, and the way forward. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 43, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Park, K.; Kim, T.E.; Kwon, Y.; Lee, Y.K. COVID-19 vaccine safety monitoring in Republic of Korea from February 26, 2021 to October 31, 2021. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2021, 12, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. First Batch of COVID-19 Vaccines Delivered through COVAX Facility Arrives in Lebanon. 2022. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/fr/media/actualites/first-batch-of-covid-19-vaccines-delivered-through-covax-facility-arrives-in-lebanon.html (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- AP News. Mexico Starts Giving First Shots of Pfizer-BioNtech Vaccine. 2020. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/mexico-coronavirus-pandemic-coronavirus-vaccine-mexico-city-16105a31023e7ff1cdb7893b452e2906 (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Taboada, B.; Zárate, S.; Iša, P.; Boukadida, C.; Vazquez-Perez, J.A.; Muñoz-Medina, J.E.; Ramírez-González, J.E.; Comas-García, A.; Grajales-Muñiz, C.; Rincón-Rubio, A.; et al. Genetic Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Mexico during the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Viruses 2021, 13, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Development and Approval of Coronavirus Vaccine. 2022. Available online: https://www.fhi.no/en/id/vaccines/coronavirus-immunisation-programme/development-of-covid-19-vaccine/ (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- WHO. Pakistan Receives First Consignment of COVID-19 Vaccines via COVAX Facility. 2022. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/media/news/pakistan-receives-first-consignment-of-covid-19-vaccines-via-covax-facility.html (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Chemaitelly, H.; Butt, A.A.; National Study Group for COVID-19 Vaccination. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 Variants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- South African Health Products Regulatory Authority. SAHPRA and the Pfizer/Biontech Comirnaty Vaccine. 2021. Available online: https://www.sahpra.org.za/press-releases/sahpra-and-the-pfizer-biontech-comirnaty-vaccinesahpra-and-the-pfizer-biontech-comirnaty-vaccine/ (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- UNICEF. Trinidad and Tobago Receives the First COVID-19 Vaccines through the COVAX Facility. 2021. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/lac/en/press-releases/trinidad-and-tobago-receives-first-covid-19-vaccines-through-covax-facility (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- GovUK. UK Medicines Regulator Gives Approval for first UK COVID-19 Vaccine (Press Release). 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-medicines-regulator-gives-approval-for-first-uk-covid-19-vaccine (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- The United Arab Emirates’ Government Portal. Vaccines Against COVID-19 in the UAE. 2022. Available online: https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/justice-safety-and-the-law/handling-the-covid-19-outbreak/vaccines-against-covid-19-in-the-uae (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- FDA. FDA Approves First COVID-19 Vaccine. 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.R.; Schneider, C.R.; Recchia, G.; Dryhurst, S.; Sahlin, U.; Dufouil, C.; Arwidson, P.; Freeman, A.J.L.; van der Linden, S. Correlates of intended COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across time and countries: Results from a series of cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascherini, M.; Nivakoski, S. Social media use and vaccine hesitancy in the European Union. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2215–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.; Bonsaksen, T.; Ruffolo, M.; Leung, J.; Thygesen, H.; Schoultz, M.; Geirdal, A.O. Willingness to Take the COVID-19 Vaccine as Reported Nine Months after the Pandemic Outbreak: A Cross-National Study. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, P.L.; Pennell, M.L.; Katz, M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine 2020, 38, 6500–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubchandani, J.; Sharma, S.; Price, J.H.; Wiblishauser, M.J.; Sharma, M.; Webb, F.J. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in the United States: A Rapid National Assessment. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.B.; Bell, R.A. Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latkin, C.A.; Dayton, L.; Yi, G.; Colon, B.; Kong, X. Mask usage, social distancing, racial, and gender correlates of COVID-19 vaccine intentions among adults in the US. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, K.H.; Anneser, E.; Toppo, A.; Allen, J.D.; Scott Parott, J.; Corlin, L. Disparities in national and state estimates of COVID-19 vaccination receipt and intent to vaccinate by race/ethnicity, income, and age group among adults ≥18 years, United States. Vaccine 2022, 40, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omaduvie, U.; Bachuwa, G.; Olalekan, A.; Vardavas, C.I.; Agaku, I. State specific estimates of vaccine hesitancy among US adults. Popul. Med. 2021, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Shao, W. Understanding the influence of political orientation, social network, and economic recovery on COVID-19 vaccine uptake among Americans. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2191–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Xu, R.H.; Wong, E.L.; Hung, C.T.; Feng, D.; Feng, Z.; Yeoh, E.-K.; Wong, S.Y.-S. Public preference for COVID-19 vaccines in China: A discrete choice experiment. Health Expect. 2020, 23, 1543–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jing, R.; Lai, X.; Zhang, H.; Lyu, Y.; Knoll, M.D.; Fang, H. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines 2020, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Wen, Z.; Feng, F.; Zou, H.; Fu, C.; Chen, L.; Shu, Y.; Sun, C. An online survey of the attitude and willingness of Chinese adults to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 2279–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-M.; Liu, L.; Sun, J.; Yan, W.; Yuan, K.; Zheng, Y.-B.; Lu, Z.-A.; Liu, L.; Ni, S.-Y.; Su, S.-Z.; et al. Public Willingness and Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination at the Initial Stage of Mass Vaccination in China. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Flowers, P.; McLeod, J.; Young, D.; Rollins, L.; The Catalyst Project Team. Social Patterning and Stability of Intention to Accept a COVID-19 Vaccine in Scotland: Will Those Most at Risk Accept a Vaccine? Vaccines 2021, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.M.; Smith, L.E.; Sim, J.; Amlôt, R.; Cutts, M.; Dasch, H.; Rubin, G.J.; Sevdalis, N. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: Results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 17, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.; Sim, J.; Cutts, M.; Dasch, H.; Amlôt, R.; Rubin, G.; Sevdalis, N.; Smith, L. COVID-19 vaccination acceptability in the UK at the start of the vaccination programme: A nationally representative cross-sectional survey (CoVAccS–wave 2). Public Health 2021, 202, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seale, H.; Heywood, A.E.; Leask, J.; Sheel, M.; Durrheim, D.N.; Bolsewicz, K.; Kaur, R. Examining Australian public perceptions and behaviors towards a future COVID-19 vaccine. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alley, S.J.; Stanton, R.; Browne, M.; To, Q.G.; Khalesi, S.; Williams, S.L.; Thwaite, T.L.; Fenning, A.S.; Vandelanotte, C. As the Pandemic Progresses, How Does Willingness to Vaccinate against COVID-19 Evolve? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attwell, K.; Lake, J.; Sneddon, J.; Gerrans, P.; Blyth, C.; Lee, J. Converting the maybes: Crucial for a successful COVID-19 vaccination strategy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albahri, A.H.; Alnaqbi, S.A.; Alshaali, A.O.; Alnaqbi, S.A.; Shahdoor, S.M. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in a Sample From the United Arab Emirates General Adult Population: A Cross-Sectional Survey, 2020. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 614499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alremeithi, H.M.; Alghefli, A.K.; Almadhani, R.; Baynouna AlKetbi, L.M. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices Toward SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the United Arab Emirates Population: An Online Community-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 687628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Setiawan, A.M.; Rajamoorthy, Y.; Sofyan, H.; Mudatsir, M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Southeast Asia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Indonesia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohaithef, M.; Padhi, B.K. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Saudi Arabia: A Web-Based National Survey. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Elimat, T.; AbuAlSamen, M.M.; Almomani, B.A.; Al-Sawalha, N.A.; Alali, F.Q. Acceptance and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines: A cross-sectional study from Jordan. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.S.; Abdullah, R.; Vered, S.; Nitzan, D. A study of ethnic, gender and educational differences in attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines in Israel—Implications for vaccination implementation policies. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, S.M.; Petcu, C.; Bader, L.; Amro, I.; Al-Hamadi, A.M.H.A.; Al Assi, M.; Ali, A.A.M.; Le Trung, K.; Diop, A.; Bellaj, T.; et al. Prevalence and Potential Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Resistance in Qatar: Results from a Nationally Representative Survey of Qatari Nationals and Migrants between December 2020 and January 2021. Vaccines 2021, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamar, M.A.; Irfan, O.; Dhillon, R.A.; Bhatti, A.; Sajid, M.I.; Awan, S.; Rizwan, W.; Zubairi, A.B.S.; Sarfraz, Z.; Khan, J.A. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine in Pakistan: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2021, 13, e16603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.C.S.; Wong, E.L.Y.; Huang, J.; Cheung, A.W.L.; Law, K.; Chong, M.K.C.; Ng, R.W.Y.; Lai, C.K.C.; Boon, S.S.; Lau, J.T.F.; et al. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: A population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, P.; Issa, A.; Noujeim, Z.; Hleyhel, M.; Saleh, N. Assessment of COVID-19 vaccines acceptance in the Lebanese population: A national cross-sectional study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2022, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.E.; Kim, W.H.; Heo, J. Socio-demographic, psychological, and experiential predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Korea, October-December 2020. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G. Intention to receive a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in Italy and its association with trust, worry and beliefs about the origin of the virus. Health Educ. Res. 2020, 35, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagić, D.; Šuljok, A.; Ančić, B. Determinants and reasons for coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine hesitancy in Croatia. Croat. Med. J. 2022, 63, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnalla, M.; Basto-Abreu, A.; Stern, D.; Bautista-Arredondo, S.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T. Acceptance, refusal and hesitancy of COVID-19 vaccination in Mexico: Ensanut 2020 COVID-19. Salud Publica Mex. 2021, 63, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.C.B.C.; Nehab, M.F.; Camacho, K.G.; Reis, A.T.; Junqueira-Marinho, M.D.F.; Abramov, D.M.; de Azevedo, Z.M.A.; de Menezes, L.A.; Salú, M.D.S.; Figueiredo, C.E.D.S.; et al. Low COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Brazil. Vaccine 2021, 39, 6262–6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, L.; Basdeo, D.; Wang, H.I. Public trust, information sources and vaccine willingness related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Trinidad and Tobago: An online cross-sectional survey. Lancet Reg. Health. Am. 2021, 3, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollamparambil, U.; Oyenubi, A.; Nwosu, C. COVID19 vaccine intentions in South Africa: Health communication strategy to address vaccine hesitancy. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarivate. Journal Citation Reports. Available online: https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/journal-citation-reports/ (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Padma, T.V. COVID vaccines to reach poorest countries in 2023—Despite recent pledges. Nature 2021, 595, 342–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljungholm, D.P. COVID-19 Threat Perceptions and Vaccine Hesitancy: Safety and Efficacy Concerns. Anal. Metaphys. 2021, 20, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, K. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Misperception, Distress, and Skepticism. Rev. Contemp. Philos. 2021, 20, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, A.; Cuțitoi, A.C. COVID-19 Vaccine Education: Vaccine Hesitancy Attitudes and Preventive Behavior Adherence. Anal. Metaphys. 2021, 20, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, V.; Zauskova, A.; Janoskova, K. Pervasive Misinformation, COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy, and Lack of Trust in Science. Rev. Contemp. Philos. 2021, 20, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, C. What Is the State-of-the-Art in Clinical Trials on Vaccine Hesitancy 2015–2020? Vaccines 2021, 9, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). SRDR: Systematic Review Data Repository™. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/cpi/about/otherwebsites/srdr.ahrq.gov/index.html (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Distiller, S.R. Literature Review Software. Available online: https://www.evidencepartners.com/products/distillersr-systematic-review-software (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Dedoose. A Cross-Platform App for Analyzing Qualitative and Mixed Methods Research with Text, Photos, Audio, Videos, Spreadsheet Data and More. Available online: https://www.dedoose.com/ (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.C.; Pak, A.W. A catalog of biases in questionnaires. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2005, 2, A13. [Google Scholar]

- Althubaiti, A. Information bias in health research: Definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2016, 9, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PICOS Criteria | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| P: participants | The general population (at least one country). | Studies specifically on specific subgroups (e.g., healthcare professionals or people with a certain disease, such as diabetes or asthma) were excluded. |

| I: intervention | Questionnaire-based studies, i.e., administration of a questionnaire/survey to collect participants’ opinion/perception about COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy/acceptance. | Studies about other topics and/or that were not questionnaire-based. |

| C: comparison | When applicable (e.g., studies carried out in more than one country). | |

| O: outcomes | To estimate the predictors of vaccine acceptance or vaccine hesitancy through a multivariate regression model. | Studies not estimating the predictors of vaccine acceptance or vaccine hesitancy through a multivariate regression model. |

| S: study design | Descriptive national studies, or descriptive studies enrolling at least 500 participants from the general population and carried out at a national level. | Studies enrolling less than 500 participants from the general population. |

| Previous Identified Similar/Related Reviews | Covered Timeframe and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria; Keywords and Number of Selected Studies | Main Findings and Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| (Wang et al., 2021) [19] A systematic review and meta-analysis | Beginning of pandemic up to 4 November 2020 Inclusion criteria: The types of included studies were not limited. Studies that did not involve COVID-19 vaccine acceptance or did not provide specific survey numbers for pooling were excluded. Keywords: “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “novel coronavirus” OR “coronavirus disease 2019” AND “vaccin *” OR “immunization”, with (*) being used to automatically screen similar/derived words. Number of selected studies: 38 | The stronger predictors of COVID-19 vaccination willingness were gender, educational level, influenza vaccination history and trust in the government. |

| (Roy et al., 2022) [20] Systematic review | Beginning of pandemic up to July 2021 Inclusion criteria: (1) peer-reviewed published articles from electronic databases including PubMed (MEDLINE), Elsevier, Embase, Science Direct, Scopus and other reputable resources; (2) survey studies involving all types of sample populations; (3) the scope and principal aim of the study was to identify the potential factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy; (4) publication studies in the English language. Keywords: “COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy” OR “COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and associated factors” OR “COVID-19 vaccine confidence” OR “COVID-19 vaccine AND acceptance intention”. Number of selected studies: 47 | The most common predictors of vaccine acceptance were as follows: safety, efficacy, side effects, effectiveness and conspiracy beliefs (Asian countries); side effects, trust in vaccine and social influence (Europe) and information sufficiency, political roles and vaccine mandates (United States). |

| Country | Date of the First Authorised or Administered COVID-19 Vaccine | COVID-19 Vaccine |

|---|---|---|

| Australia [33] | 25 January 2021 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (Comirnaty) |

| Brazil [34] | 17 January 2021 | CoronaVac, of the Butantan Institute, in partnership with Chinese pharmaceutical company Sinovac and AstraZeneca, of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), in collaboration with the Astrazeneca/Oxford consortium |

| China [35] | 30 December 2020 | Sinopharm China Biotechnology Co., Ltd. |

| European Union (e.g., Italy; Croatia; France; Germany; Sweden or Spain) [9] | 21 December 2020 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (Comirnaty) |

| Hong Kong [36] | January 2021 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (Comirnaty) |

| Indonesia [37] | 11 January 2021 | CoronaVac, from Sinovac Biotech China |

| Israel [38] | 20 December 2020 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine |

| Japan [39] | 14 February 2021 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (Comirnaty) |

| Jordan [40,41] | 13 January 2021 | Pfizer-BioNTech and China’s Sinopharm coronavirus vaccines |

| Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [42] | 17 December 2020 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (Comirnaty) |

| South Korea [43] | 10 February 2021 | AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine |

| Lebanon [44] | 24 March 2021 | AstraZeneca vaccine |

| Mexico [45,46] | 24 December 2020 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (Comirnaty) |

| Norway [47] | 21 December 2020 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (Comirnaty) |

| Pakistan [48] | 8 May 2021 | Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines |

| Qatar [49] | 21 December 2020 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (Comirnaty) |

| South Africa [50] | 16 March 2021 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (Comirnaty) |

| Trinidad and Tobago [51] | 30 March 2021 | AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine, manufactured by SK Bioscience of South Korea |

| UK [52] | 2 December 2020 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (Comirnaty) |

| United Arab Emirates [53] | 9 December 2020 | Sinopharm, Beijing Institute of Biological Products’ inactivated vaccine |

| USA [54] | 11 December 2020 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (Comirnaty) |

| Criteria | Score | Maximum Score | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated? | 37 | 37 | 100 |

| Was the study population clearly specified and defined? | 36 | 37 | 97.3 |

| Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%? | 24 ** | 37 | 64.9 * |

| Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? | 18.5 | 18.5 | 100 |

| Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants? | 18.5 | 18.5 | 100 |

| Was a sample size justification, power description or variance and effect estimate provided? | 25 | 37 | 67.6 * |

| Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable and implemented consistently across all study participants? | 37 | 37 | 100 |

| Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? (i.e., Was the questionnaire administered at least two times in different moments?/exposure or evaluation of independent variable) | 2 | 18.5 | 10.8 * |