Abstract

Within exponential families, which may consist of multi-parameter and multivariate distributions, a variety of divergence measures, such as the Kullback–Leibler divergence, the Cressie–Read divergence, the Rényi divergence, and the Hellinger metric, can be explicitly expressed in terms of the respective cumulant function and mean value function. Moreover, the same applies to related entropy and affinity measures. We compile representations scattered in the literature and present a unified approach to the derivation in exponential families. As a statistical application, we highlight their use in the construction of confidence regions in a multi-sample setup.

Keywords:

exponential family; cumulant function; mean value function; divergence measure; distance measure; affinity MSC:

60E05; 62H12; 62F25

1. Introduction

There is a broad literature on divergence and distance measures for probability distributions, e.g., on the Kullback–Leibler divergence, the Cressie–Read divergence, the Rényi divergence, and Phi divergences as a general family, as well as on associated measures of entropy and affinity. For definitions and details, we refer to [1]. These measures have been extensively used in statistical inference. Excellent monographs on this topic were provided by Liese and Vajda [2], Vajda [3], Pardo [1], and Liese and Miescke [4].

Within an exponential family as defined in Section 2, which may consist of multi-parameter and multivariate distributions, several divergence measures and related quantities are seen to have nice explicit representations in terms of the respective cumulant function and mean value function. These representations are contained in different sources. Our focus is on a unifying presentation of main quantities, while not aiming at an exhaustive account. As an application, we derive confidence regions for the parameters of exponential distributions based on different divergences in a simple multi-sample setup.

For the use of the aforementioned measures of divergence, entropy, and affinity, we refer to the textbooks [1,2,3,4] and exemplarily to [5,6,7,8,9,10] for statistical applications, including the construction of test procedures as well as methods based on dual representations of divergences, and to [11] for a classification problem.

2. Exponential Families

Let be a parameter set, be a -finite measure on the measurable space , and be an exponential family (EF) of distributions on with -density

of for , where are real-valued functions on and are real-valued Borel-measurable functions with . Usually, is either the counting measure on the power set of (for a family of discrete distributions) or the Lebesgue measure on the Borel sets of (in the continuous case). Without loss of generality and for a simple notation, we assume that (the set is a null set for all ). Let denote the -finite measure with -density h.

We assume that representation (1) is minimal in the sense that the number k of summands in the exponent cannot be reduced. This property is equivalent to being affinely independent mappings and being -affinely independent mappings; see, e.g., [12] (Cor. 8.1). Here, -affine independence means affine independence on the complement of every null set of .

To obtain simple formulas for divergence measures in the following section, it is convenient to use the natural parameter space

and the (minimal) canonical representation of with -density

of and normalizing constant for , where denotes the (column) vector of the mappings and denotes the (column) vector of the statistics . For simplicity, we assume that is regular, i.e., we have that ( is full) and that is open; see [13]. In particular, this guarantees that is minimal sufficient and complete for ; see, e.g., [14] (pp. 25–27).

The cumulant function

associated with is strictly convex and infinitely often differentiable on the convex set ; see [13] (Theorem 1.13 and Theorem 2.2). It is well-known that the Hessian matrix of at coincides with the covariance matrix of under and that it is also equal to the Fisher information matrix at . Moreover, by introducing the mean value function

we have the useful relation

where denotes the gradient of ; see [13] (Cor. 2.3). is a bijective mapping from to the interior of the convex support of , i.e., the closed convex hull of the support of ; see [13] (p. 2 and Theorem 3.6).

Finally, note that representation (2) can be rewritten as

for .

3. Divergence Measures

Divergence measures may be applied, for instance, to quantify the “disparity” of a distribution to some reference distribution or to measure the “distance” between two distributions within some family in a certain sense. If the distributions in the family are dominated by a -finite measure, various divergence measures have been introduced by means of the corresponding densities. In parametric statistical inference, they serve to construct statistical tests or confidence regions for underlying parameters; see, e.g., [1].

Definition 1.

Let be a set of distributions on . A mapping is called a divergence (or divergence measure) if:

- (i)

- for all and (positive definiteness).

If additionally

- (ii)

- for all (symmetry) is valid, D is called a distance (or distance measure or semi-metric). If D then moreover meets

- (iii)

- for all (triangle inequality), D is said to be a metric.

Some important examples are the Kullback–Leibler divergence (KL-divergence):

the Jeffrey distance:

as a symmetrized version, the Rényi divergence:

along with the related Bhattacharyya distance , the Cressie–Read divergence (CR-divergence):

which is the same as the Chernoff -divergence up to a parameter transformation, the related Matusita distance , and the Hellinger metric:

for distributions with -densities , provided that the integrals are well-defined and finite.

, , and for are divergences, and , , , , and , since they moreover satisfy symmetry, are distances on . is known to be a metric on .

In parametric models, it is convenient to use the parameters as arguments and briefly write, e.g.,

if the parameter is identifiable, i.e., if the mapping is one-to-one on . This property is met for the EF in Section 2 with minimal canonical representation (5); see, e.g., [13] (Theorem 1.13(iv)).

It is known from different sources in the literature that the EF structure admits simple formulas for the above divergence measures in terms of the corresponding cumulant function and/or mean value function. For the KL-divergence, we refer to [15] (Cor. 3.2) and [13] (pp. 174–178), and for the Jeffrey distance also to [16].

Proof.

As a consequence of Theorem 1, and are infinitely often differentiable on , and the derivatives are easily obtained by making use of the EF properties. For example, by using Formula (4), we find and that the Hessian matrix of at is the Fisher information matrix , where is considered to be fixed.

Moreover, we obtain from Theorem 1 that the reverse KL-divergence for is nothing but the Bregman divergence associated with the cumulant function ; see, e.g., [1,11,17]. As an obvious consequence of Theorem 1, other symmetrizations of the KL-divergence may be expressed in terms of and as well, such as the so-called resistor-average distance (cf. [18])

with , , or the distance

obtained by taking the harmonic and geometric mean of and ; see [19].

Remark 1.

Formula (9) can be used to derive the test statistic

of the likelihood-ratio test for the test problem

where . If the maximum likelihood estimators (MLEs) and of ζ in and (based on x) both exist, we have:

by using that the unrestricted MLE fulfils ; see, e.g., [12] (p. 190) and [13] (Theorem 5.5). In particular, when testing a simple null hypothesis with for some fixed , we have .

Convenient representations within EFs of the divergences in Formulas (6)–(8) can also be found in the literature; we refer to [2] (Prop. 2.22) for , , and , to [20] for , and to [9] for . The formulas may all be obtained by computing the quantity

For , we have the following identity (cf. [21]).

Proof.

Let and . Then,

where the convexity of ensures that is defined. □

Remark 2.

For arbitrary divergence measures, several transformations and skewed versions as well as symmetrization methods, such as the Jensen–Shannon symmetrization, are studied in [19]. Applied to the KL-divergence, the skew Jensen–Shannon divergence is introduced as

for and , which includes the Jensen–Shannon distance for (the distance even forms a metric). Note that, for , the density of the mixture does not belong to , in general, such that the identity in Theorem 1 for the KL-divergence is not applicable, here.

However, from the proof of Lemma 1, it is obvious that

i.e., the EF is closed when forming normalized weighted geometric means of the densities. This finding is utilized in [19] to introduce another version of the skew Jensen–Shannon divergence based on the KL-divergence, where the weighted arithmetic mean of the densities is replaced by the normalized weighted geometric mean. The skew geometric Jensen–Shannon divergence thus obtained is given by

for . By using Theorem 1, we find

for and .

In particular, setting gives the geometric Jensen–Shannon distance:

For more details and properties as well as related divergence measures, we refer to [19,22].

Formulas for , , and are readily deduced from Lemma 1.

Theorem 2.

Proof.

Since

the assertions are directly obtained from Lemma 1. □

It is well-known that

such that Formula (9) results from the representation of the Rényi divergence in Theorem 2 by sending q to 1.

The Sharma–Mittal divergence (see [1]) is closely related to the Rényi divergence as well and, by Theorem 2, a representation in EFs is available.

Moreover, representations within EFs for so-called local divergences can be derived as, e.g., the Cressie–Read local divergence, which results from the CR-divergence by multiplying the integrand with some kernel density function; see [23].

Remark 3.

Inspecting the proof of Theorem 2, and are seen to be strictly decreasing functions of for ; for , this is also true for . From an inferential point of view, this finding yields that, for fixed , test statistics and pivot statistics based on these divergence measures will lead to the same test and confidence region, respectively. This is not the case within some divergence families such as , , where different values of q correspond to different tests and confidence regions, in general.

A more general form of the Hellinger metric is given by

for , where ; see Formula (8). For , i.e., if m is even, the binomial theorem then yields

and inserting for , , according to Lemma 1 along with gives a formula for in terms of the cumulant function of the EF in Section 2. This representation is stated in [16].

Note that the representation for in Lemma 1 (and thus the formulas for and in Theorem 2) are also valid for and as long as is true. This can be used, e.g., to find formulas for and , which coincide with the Pearson -divergence

for with and the reverse Pearson -divergence (or Neyman -divergence) for with . Here, the restrictions on the parameters are obsolete if for some , which is the case for the EF of Poisson distributions and for any EF of discrete distributions with finite support such as binomial or multinomial distributions (with fixed). Moreover, quantities similar to such as for arise in the so-called -divergence, for which some representations can also be obtained; see [24] (Section 4).

Remark 4.

If the assumption of the EF to be regular is weakened to being steep, Lemma 1 and Theorem 2 remain true; moreover, the formulas in Theorem 1 are valid for ζ lying in the interior of . Steep EFs are full EFs in which boundary points of that belong to satisfy a certain property. A prominent example is provided by the full EF of inverse normal distributions. For details, see, e.g., [13].

The quantity in Formula (12) is the two-dimensional case of the weighted Matusita affinity

for distributions with -densities , weights satisfying , and ; see [4] (p. 49) and [6]. , in turn, is a generalization of the Matusita affinity

introduced in [25,26]. Along the lines of the proof of Lemma 1, we find the representation

for the EF in Section 2; cf. [27]. In [4], the quantity in Formula (14) is termed Hellinger transform, and a representation within EFs is stated in Example 1.88.

can be used, for instance, as the basis of a homogeneity test (with null hypothesis ) or in discriminant problems.

For a representation of an extension of the Jeffrey distance to more than two distributions in an EF, the so-called Toussaint divergence, along with statistical applications, we refer to [8].

4. Entropy Measures

The literature on entropy measures, their applications, and their relations to divergence measures is broad. We focus on some selected results and state several simple representations of entropy measures within EFs.

Let the EF in Section 2 be given with , which is the case, e.g., for the one-parameter EFs of geometric distributions and exponential distributions as well as for the two-parameter EF of univariate normal distributions. Formula (5) then yields that

for and with . Note that the latter condition is not that restrictive, since the natural parameter space of a regular EF is usually a cartesian product of the form with for .

The Taneja entropy is then obtained as

for and with , which includes the Shannon entropy

by setting ; see [7,28].

Several other important entropy measures are functions of and therefore admit respective representations in terms of the cumulant function of the EF. Two examples are provided by the Rényi entropy and the Havrda–Charvát entropy (or Tsallis entropy), which are given by

for with ; for the definitions, see, e.g., [1]. More generally, the Sharma–Mittal entropy is seen to be

for with , which yields the representation for as , for as , and for as ; see [29].

If the assumption is not met, the calculus of the entropies becomes more involved. The Shannon entropy, for instance, is then given by

where the additional additive term , as it is the mean of under , will also depend on , in general; see, e.g., [17]. Since

for and with (cf. [29]), more complicated expressions result for other entropies and require to compute respective moments of h. Of course, we arrive at the same expressions as for the case if the entropies are introduced with respect to the dominating measure , which is neither a counting nor a Lebesgue measure, in general; see Section 2. However, in contrast to divergence measures, entropies usually depend on the dominating measure, such that the resulting entropy values of the distributions will be different.

Representations of Rényi and Shannon entropies for various multivariate distributions including several EFs can be found in [30].

5. Application

As aforementioned, applications of divergence measures in statistical inference have been extensively discussed; see the references in the introduction. As an example, we make use of the representations of the symmetric divergences (distances) in Section 3 to construct confidence regions that are different from the standard rectangles for exponential parameters in a multi-sample situation.

Let and , , , be independent random variables, where follow an exponential distribution with (unknown) mean for . The overall joint distribution , say, has the density function

with the k-dimensional statistic

for , the cumulant function

and . It is easily verified that forms a regular EF with minimal canonical representation (15). The corresponding mean value function is given by

To construct confidence regions for based on the Jeffrey distance , the resistor-average distance , the distance , the Hellinger metric , and the geometric Jensen–Shannon distance , we first compute the KL-divergence and the affinity . Note that, by Remark 3, constructing a confidence region based on is equivalent to constructing a confidence region based on either , , or .

For , we obtain from Theorem 1 that

such that

and are then computed by inserting for and in Formulas (10) and (11). Applying Lemma 1 yields

which gives by inserting, and, by using Formula (13), also leads to

The MLE of based on , is given by

where are independent. By inserting the random distances , , , , and turn out to depend on only through the vector of component-wise ratios, where has a gamma distribution with shape parameter , scale parameter , and mean 1 for . Since these ratios are moreover independent, the above random distances form pivot statistics with distributions free of .

Now, confidence regions for with confidence level are given by

where denotes the p-quantile of for , numerical values of which can readily be obtained via Monte Carlo simulation by sampling from gamma distributions.

Confidence regions for the mean vector with confidence level are then given by

for .

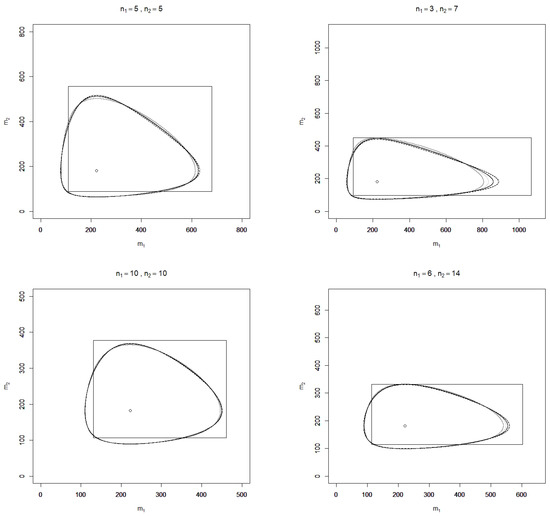

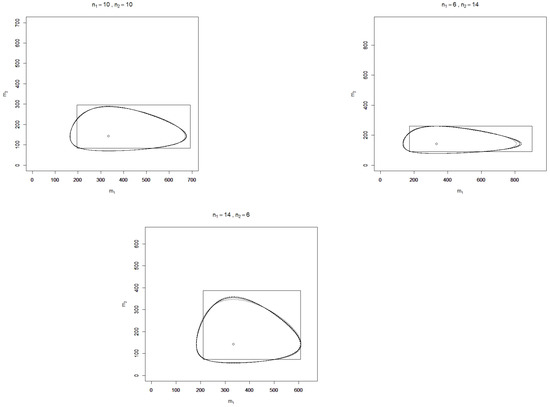

In Figure 1 and Figure 2, realizations of , , , , and are depicted for the two-sample case () and some sample sizes and values of , where the confidence level is chosen as . Additionally, realizations of the standard confidence region

with a confidence level of 90% for are shown in the figures, where and denotes the -quantile of the chi-square distribution with v degrees of freedom.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the confidence regions (solid light grey line), (solid dark grey line), (solid black line), (dashed black line), (dotted black line), and R (rectangle) for the mean vector with level 90% and sample sizes based on a realization , respectively of the MLE (circle).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the confidence regions (solid light grey line), (solid dark grey line), (solid black line), (dashed black line), (dotted black line), and R (rectangle) for the mean vector with level 90% and sample sizes based on a realization , respectively of the MLE (circle).

It is found that over the sample sizes and realizations of considered, the confidence regions , , , , and are similarly shaped but do not coincide as the plots for different sample sizes show. In terms of (observed) area, all divergence-based confidence regions perform considerably better than the standard rectangle. This finding, however, depends on the parameter of interest, which here is the vector of exponential means; for the divergence-based confidence regions and the standard rectangle for itself, the contrary assertion is true. Although the divergence-based confidence regions have a smaller area than the standard rectangle, this is not at the cost of large projection lengths with respect to the - and -axes, which serve as further characteristics for comparing confidence regions. Monte Carlo simulations may moreover be applied to compute the expected area and projection lengths as well as the coverage probabilities of false parameters for a more rigorous comparison of the performance of the confidence regions, which is beyond the scope of this article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and U.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, U.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CR | Cressie–Read |

| EF | exponential family |

| KL | Kullback–Leibler |

| MLE | maximum likelihood estimator |

References

- Pardo, L. Statistical Inference Based on Divergence Measures; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liese, F.; Vajda, I. Convex Statistical Distances; Teubner: Leipzig, Germany, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Vajda, I. Theory of Statistical Inference and Information; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Liese, F.; Miescke, K.J. Statistical Decision Theory: Estimation, Testing, and Selection; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Broniatowski, M.; Keziou, A. Parametric estimation and tests through divergences and the duality technique. J. Multivar. Anal. 2009, 100, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzur, A.; Kamps, U. Homogeneity testing via weighted affinity in multiparameter exponential families. Stat. Methodol. 2016, 32, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez, M.L. Shannon’s entropy in exponential families: Statistical applications. Appl. Math. Lett. 2000, 13, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, M.; Salicrú, M.; Morales, D.; Pardo, L. Divergence measures between populations: Applications in the exponential family. Commun. Statist. Theory Methods 1997, 26, 1099–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D.; Pardo, L.; Pardo, M.C.; Vajda, I. Rényi statistics for testing composite hypotheses in general exponential models. Statistics 2004, 38, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, A.; Broniatowski, M. Dual divergence estimators and tests: Robustness results. J. Multivar. Anal. 2011, 102, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzur, A.; Kamps, U. Classification into Kullback–Leibler balls in exponential families. J. Multivar. Anal. 2016, 150, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barndorff-Nielsen, O. Information and Exponential Families in Statistical Theory; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.D. Fundamentals of Statistical Exponential Families; Institute of Mathematical Statistics: Hayward, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Pfanzagl, J. Parametric Statistical Theory; de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kullback, S. Information Theory and Statistics; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Huzurbazar, V.S. Exact forms of some invariants for distributions admitting sufficient statistics. Biometrika 1955, 42, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F.; Nock, R. Entropies and cross-entropies of exponential families. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 17th International Conference on Image Processing, Hong Kong, China, 26–29 September 2010; pp. 3621–3624. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.; Sinanovic, S. Symmetrizing the Kullback–Leibler distance. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2001. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1911/19969 (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- Nielsen, F. On the Jensen–Shannon symmetrization of distances relying on abstract means. Entropy 2019, 21, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kailath, T. The divergence and Bhattacharyya distance measures in signal selection. IEEE Trans. Commun. Technol. 1967, 15, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, Q.N.; Bedbur, S.; Kamps, U. Distances between models of generalized order statistics. J. Multivar. Anal. 2013, 118, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F. On a generalization of the Jensen–Shannon divergence and the Jensen–Shannon centroid. Entropy 2020, 22, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avlogiaris, G.; Micheas, A.; Zografos, K. On local divergences between two probability measures. Metrika 2016, 79, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, H.; Eguchi, S. Robust parameter estimation with a small bias against heavy contamination. J. Multivar. Anal. 2008, 99, 2053–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusita, K. Decision rules based on the distance, for problems of fit, two samples, and estimation. Ann. Math. Statist. 1955, 26, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusita, K. On the notion of affinity of several distributions and some of its applications. Ann. Inst. Statist. Math. 1967, 19, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garren, S.T. Asymptotic distribution of estimated affinity between multiparameter exponential families. Ann. Inst. Statist. Math. 2000, 52, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beitollahi, A.; Azhdari, P. Exponential family and Taneja’s entropy. Appl. Math. Sci. 2010, 41, 2013–2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, F.; Nock, R. A closed-form expression for the Sharma–Mittal entropy of exponential families. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2012, 45, 032003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zografos, K.; Nadarajah, S. Expressions for Rényi and Shannon entropies for multivariate distributions. Statist. Probab. Lett. 2005, 71, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).