Role of IRE1α/XBP-1 in Cystic Fibrosis Airway Inflammation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Contribution of Airway Epithelia to Cystic Fibrosis (CF) Airway Inflammation

3. The Contribution of Airway Macrophages (AMs) to CF Airway Inflammation

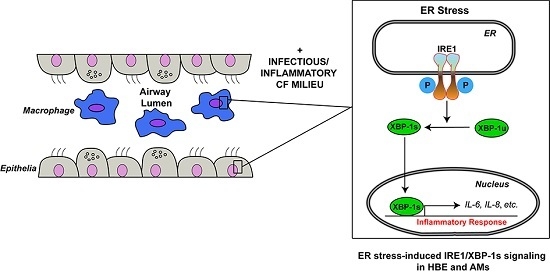

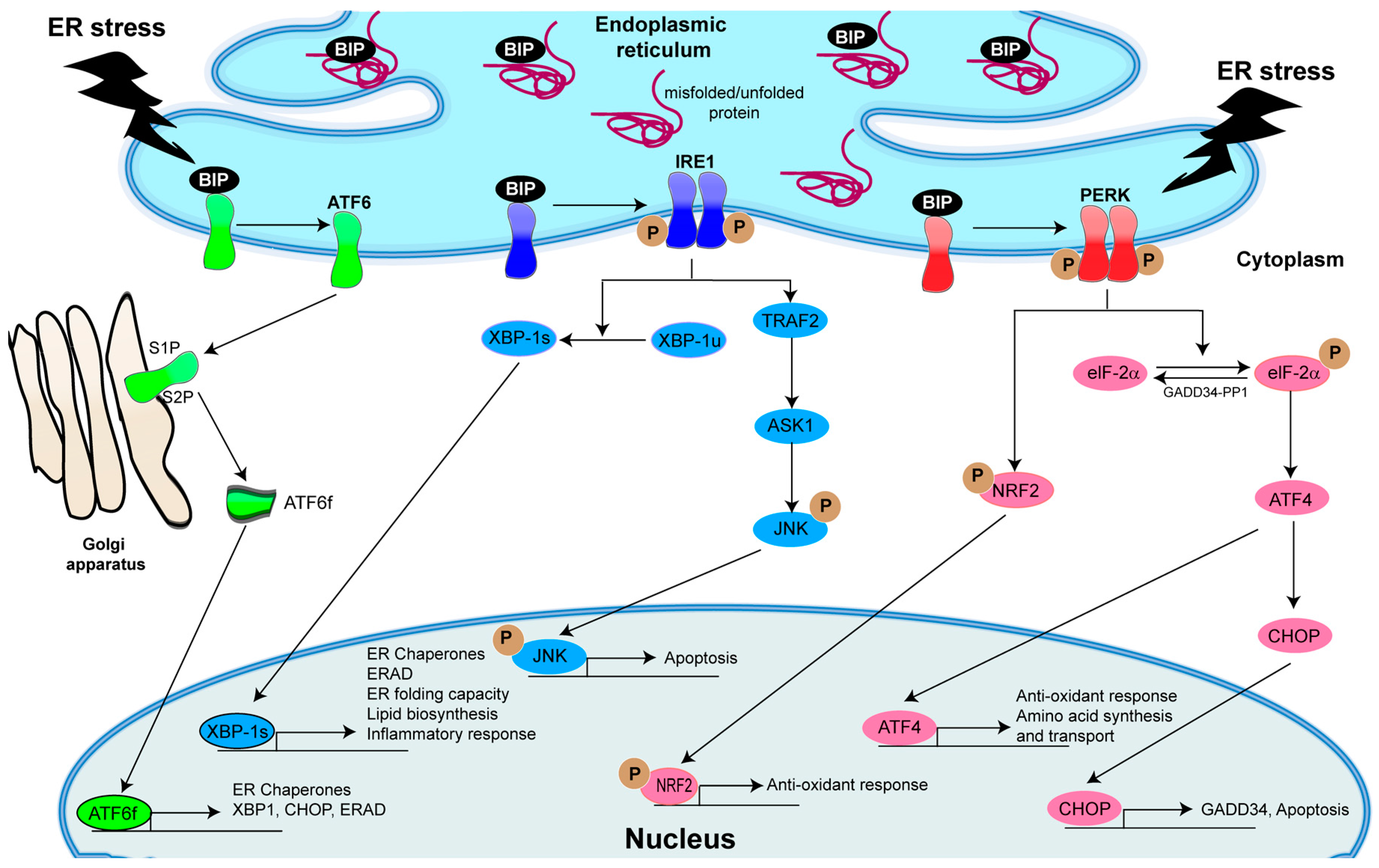

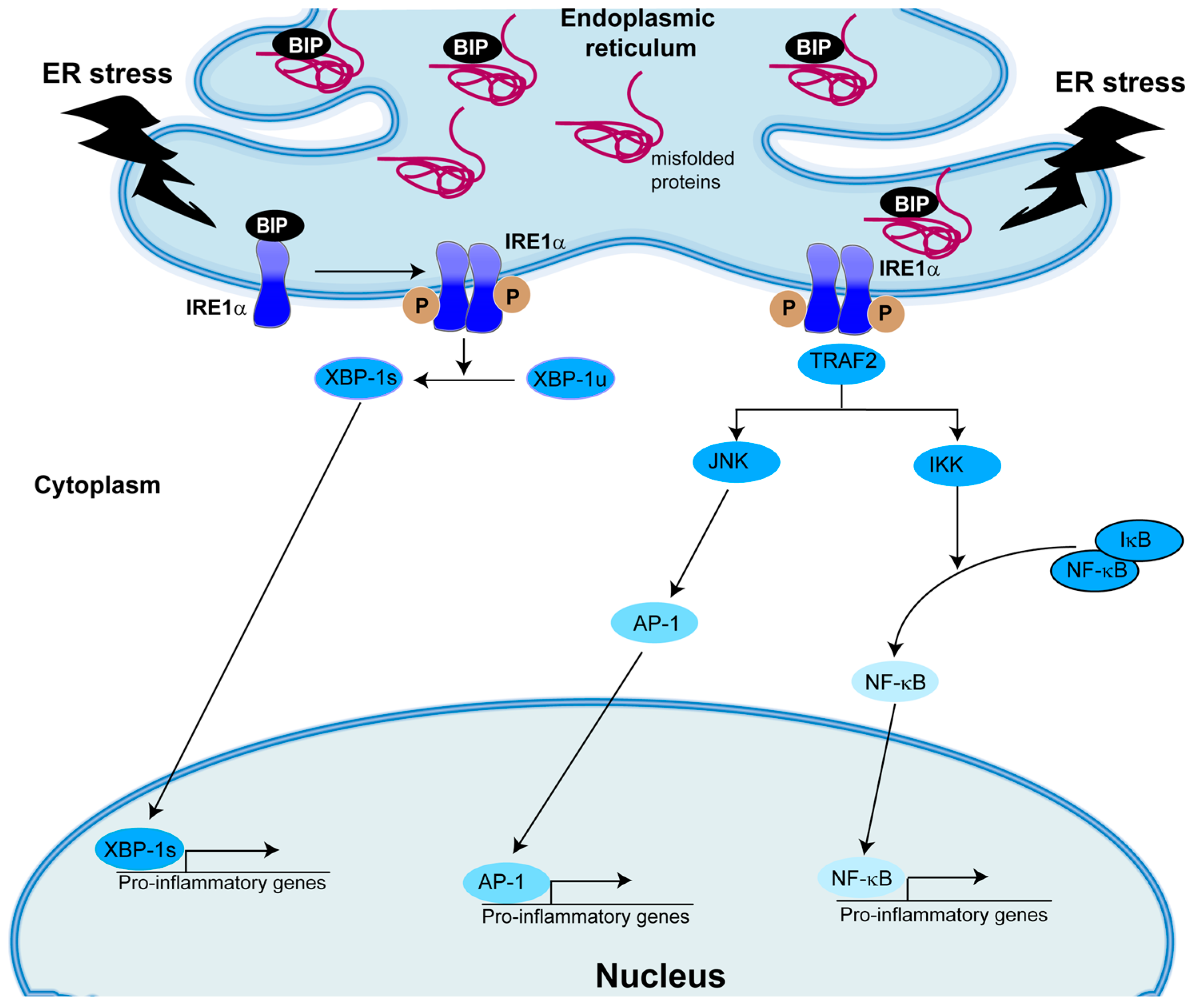

4. The Central Role of Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) Activation in Inflammatory Responses

5. Role of IRE1α/XBP-1 in Inflammation

5.1. Role of XBP-1s in Human Airway Epithelial Cytokine Secretion Relevant to CF Airways

5.2. Role of XBP-1s in Human AM Cytokine Secretion Relevant to CF Airways

6. Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) Mutations Are Not Associated with Activation of XBP-1-Dependent Signaling

6.1. Evidence from Airway Epithelia

6.2. Evidence from AMs

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMs | Airway macrophages |

| ATF4 | Activating transcription factor 4 |

| ATF6 | Activating transcription factor 6 |

| AP1 | Activator protein 1 |

| ASK1 | Apoptotic-signaling kinase-1 |

| Ca2+ | Calcium |

| CF | Cystic fibrosis |

| CFTR | Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator |

| CHOP | C/EBP homologous protein |

| DN-XBP-1 | Dominant negative XBP-1 |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| eIF-2α | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ERAD | ER-associated degradation |

| GADD135 | Growth arrest and DNA damage |

| IKK | IκB kinase |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IRE1 | Inositol-requiring transmembrane kinase/endonuclease-1 |

| JNK | Jun-N-terminal kinase |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 |

| PERK | PKR-like ER kinase |

| PP2A | Protein phosphatase 2A |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor β |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor |

| TRAF2 | TNFα receptor-associated factor 2 |

| SMM | Supernatant from mucopurulent material |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

| XBP-1 | X-box binding protein-1 |

References

- Saiman, L.; Siegel, J. Infection control in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, R.C. Evidence for airway surface dehydration as the initiating event in CF airway disease. J. Intern. Med. 2007, 261, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Cymberknoh, M.; Kerem, E.; Ferkol, T.; Elizur, A. Airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Thorax 2013, 68, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doring, G.; Worlitzsch, D. Inflammation in cystic fibrosis and its management. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2000, 1, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pier, G.B. Role of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in innate immunity to pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 8822–8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, A.; Issler, A.C.; Cotton, C.U.; Kelley, T.J.; Verkman, A.S.; Davis, P.B. CFTR inhibition mimics the cystic fibrosis inflammatory profile. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2007, 292, L383–L395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shute, J.; Marshall, L.; Bodey, K.; Bush, A. Growth factors in cystic fibrosis—When more is not enough. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2003, 4, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilliard, T.N.; Regamey, N.; Shute, J.K.; Nicholson, A.G.; Alton, E.W.; Bush, A.; Davies, J.C. Airway remodelling in children with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2007, 62, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellgaard, L.; Helenius, A. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, F.J.; Argon, Y. Protein folding in the ER. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 1999, 10, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, C.M.; Paradiso, A.M.; Schwab, U.; Perez-Vilar, J.; Jones, L.; O’Neal, W.; Boucher, R.C. Chronic airway infection/inflammation induces a Ca2+i-dependent hyperinflammatory response in human cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 17798–17806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, M.E.; Olsen, J.C.; Fulcher, N.B.; Wolfgang, M.C.; O’Neal, W.K.; Ribeiro, C.M. Airway epithelial inflammation-induced endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store expansion is mediated by X-box binding protein-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 14904–14913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, C.M.; Boucher, R.C. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in cystic fibrosis-related airway inflammatory responses. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2010, 7, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, C.M.; O’Neal, W.K. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in chronic obstructive lung diseases. Curr. Mol. Med. 2012, 12, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, M.B.; Jones, L.; Brighton, B.; Ehre, C.; Abdulah, L.; Davis, C.W.; Ron, D.; O’Neal, W.K.; Ribeiro, C.M. The ER stress transducer IRE1Β is required for airway epithelial mucin production. Mucosal Immunol. 2013, 6, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, P.; Ron, D. The unfolded protein response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 2011, 334, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vareille, M.; Kieninger, E.; Edwards, M.R.; Regamey, N. The airway epithelium: Soldier in the fight against respiratory viruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, R.C.; Cotton, C.U.; Gatzy, J.T.; Knowles, M.R.; Yankaskas, J.R. Evidence for reduced Cl− and increased Na+ permeability in cystic fibrosis human primary cell cultures. J. Physiol. 1988, 405, 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keiser, N.W.; Engelhardt, J.F. New animal models of cystic fibrosis: What are they teaching us? Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2011, 17, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, H.; Grubb, B.R.; Tarran, R.; Randell, S.H.; Gatzy, J.T.; Davis, C.W.; Boucher, R.C. Evidence for periciliary liquid layer depletion, not abnormal ion composition, in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis airways disease. Cell 1998, 95, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, C.A.; Da Tan, C.; Tarran, R. Does epithelial sodium channel hyperactivity contribute to cystic fibrosis lung disease? J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 4377–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstan, M.W.; Hilliard, K.A.; Norvell, T.M.; Berger, M. Bronchoalveolar lavage findings in cystic fibrosis patients with stable, clinically mild lung disease suggest ongoing infection and inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994, 150, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.Z.; Wagener, J.S.; Bost, T.; Martinez, J.; Accurso, F.J.; Riches, D.W. Early pulmonary inflammation in infants with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995, 151, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muhlebach, M.S.; Stewart, P.W.; Leigh, M.W.; Noah, T.L. Quantitation of inflammatory responses to bacteria in young cystic fibrosis and control patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 160, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziady, A.G.; Davis, P.B. Current prospects for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2006, 6, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranganathan, S.C.; Parsons, F.; Gangell, C.; Brennan, S.; Stick, S.M.; Sly, P.D. Australian Respiratory Early Surveillance Team for Cystic Fibrosis. Evolution of pulmonary inflammation and nutritional status in infants and young children with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2011, 66, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagel, S.D.; Wagner, B.D.; Anthony, M.M.; Emmett, P.; Zemanick, E.T. Sputum biomarkers of inflammation and lung function decline in children with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizur, A.; Cannon, C.L.; Ferkol, T.W. Airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Chest 2008, 133, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhlebach, M.S.; Noah, T.L. Endotoxin activity and inflammatory markers in the airways of young patients with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 165, 911–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, D.Y.; Nething, I.; Otto, J.; Urbanek, R.; Eichler, I. Cytokine concentrations in sputum from patients with cystic fibrosis and their relation to eosinophil activity. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1997, 155, 1050–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taggart, C.; Coakley, R.J.; Greally, P.; Canny, G.; O’Neill, S.J.; McElvaney, N.G. Increased elastase release by CF neutrophils is mediated by tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-8. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2000, 278, L33–L41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tabary, O.; Escotte, S.; Couetil, J.P.; Hubert, D.; Dusser, D.; Puchelle, E.; Jacquot, J. High susceptibility for cystic fibrosis human airway gland cells to produce IL-8 through the IκB kinase α pathway in response to extracellular nacl content. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 3377–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabary, O.; Zahm, J.M.; Hinnrasky, J.; Couetil, J.P.; Cornillet, P.; Guenounou, M.; Gaillard, D.; Puchelle, E.; Jacquot, J. Selective up-regulation of chemokine IL-8 expression in cystic fibrosis bronchial gland cells in vivo and in vitro. Am. J. Pathol. 1998, 153, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfield, T.L.; Konstan, M.W.; Berger, M. Altered respiratory epithelial cell cytokine production in cystic fibrosis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999, 104, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammouni, W.; Figarella, C.; Baeza, N.; Marchand, S.; Merten, M.D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide induces CF-like alteration of protein secretion by human tracheal gland cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 241, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, C.M.; Paradiso, A.M.; Carew, M.A.; Shears, S.B.; Boucher, R.C. Cystic fibrosis airway epithelial Ca2+i signaling: The mechanism for the larger agonist-mediated Ca2+i signals in human cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 10202–10209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S.B.; Read, R.C. Macrophage defences against respiratory tract infections. Br. Med. Bull. 2002, 61, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps, J.C.; Aronoff, D.M.; Curtis, J.L.; Goel, D.; O’Brien, E.; Mancuso, P. Cigarette smoke exposure impairs pulmonary bacterial clearance and alveolar macrophage complement-mediated phagocytosis of streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 1214–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dockrell, D.H.; Marriott, H.M.; Prince, L.R.; Ridger, V.C.; Ince, P.G.; Hellewell, P.G.; Whyte, M.K. Alveolar macrophage apoptosis contributes to pneumococcal clearance in a resolving model of pulmonary infection. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 5380–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCubbrey, A.L.; Curtis, J.L. Efferocytosis and lung disease. Chest 2013, 143, 1750–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S.; Taylor, P.R. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, N.B.; Lu, M.H.; Fan, Y.H.; Cao, Y.L.; Zhang, Z.R.; Yang, S.M. Macrophages in tumor microenvironments and the progression of tumors. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 2012, 948098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leveque, M.; Le Trionnaire, S.; del Porto, P.; Martin-Chouly, C. The impact of impaired macrophage functions in cystic fibrosis disease progression. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Bonecchi, R.; Martinez, F.O.; Galliera, E.; Perrier, P.; Allavena, P.; Locati, M. Tuning of innate immunity and polarized responses by decoy receptors. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2003, 132, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartl, D.; Griese, M.; Kappler, M.; Zissel, G.; Reinhardt, D.; Rebhan, C.; Schendel, D.J.; Krauss-Etschmann, S. Pulmonary TH2 response in pseudomonas aeruginosa—Infected patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasemann, H.; Schwiertz, R.; Matthiesen, S.; Racke, K.; Ratjen, F. Increased arginase activity in cystic fibrosis airways. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 172, 1523–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, M.; Huaux, F.; Gavilanes, X.; van den Brule, S.; Lebecque, P.; Lo Re, S.; Lison, D.; Scholte, B.; Wallemacq, P.; Leal, T. Azithromycin reduces exaggerated cytokine production by M1 alveolar macrophages in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009, 41, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cory, T.J.; Birket, S.E.; Murphy, B.S.; Hayes, D., Jr.; Anstead, M.I.; Kanga, J.F.; Kuhn, R.J.; Bush, H.M.; Feola, D.J. Impact of azithromycin treatment on macrophage gene expression in subjects with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2014, 13, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubamba, B.A.; Jones, L.C.; O’Neal, W.K.; Boucher, R.C.; Ribeiro, C.M. X-box-binding protein 1 and innate immune responses of human cystic fibrosis alveolar macrophages. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1449–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruscia, E.M.; Bonfield, T.L. Cystic fibrosis lung immunity: The role of the macrophage. J. Innate Immun. 2016, 8, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruscia, E.M.; Bonfield, T.L. Innate and adaptive immunity in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Chest Med. 2016, 37, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruscia, E.M.; Zhang, P.X.; Satoh, A.; Caputo, C.; Medzhitov, R.; Shenoy, A.; Egan, M.E.; Krause, D.S. Abnormal trafficking and degradation of TLR4 underlie the elevated inflammatory response in cystic fibrosis. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 6990–6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Porto, P.; Cifani, N.; Guarnieri, S.; di Domenico, E.G.; Mariggio, M.A.; Spadaro, F.; Guglietta, S.; Anile, M.; Venuta, F.; Quattrucci, S.; et al. Dysfunctional CFTR alters the bactericidal activity of human macrophages against pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19970. [Google Scholar]

- Di, A.; Brown, M.E.; Deriy, L.V.; Li, C.; Szeto, F.L.; Chen, Y.; Huang, P.; Tong, J.; Naren, A.P.; Bindokas, V.; et al. CFTR regulates phagosome acidification in macrophages and alters bactericidal activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deriy, L.V.; Gomez, E.A.; Zhang, G.; Beacham, D.W.; Hopson, J.A.; Gallan, A.J.; Shevchenko, P.D.; Bindokas, V.P.; Nelson, D.J. Disease-causing mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator determine the functional responses of alveolar macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 35926–35938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radtke, A.L.; Anderson, K.L.; Davis, M.J.; DiMagno, M.J.; Swanson, J.A.; O’Riordan, M.X. Listeria monocytogenes exploits cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) to escape the phagosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 1633–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggie, P.M.; Verkman, A.S. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-independent phagosomal acidification in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 31422–31428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, A.; Kopic, S.; Murek, M.; Caputo, C.; Geibel, J.P.; Egan, M.E. Calcium-modulated chloride pathways contribute to chloride flux in murine cystic fibrosis-affected macrophages. Pediatr. Res. 2011, 70, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, S.; Sly, P.D.; Gangell, C.L.; Sturges, N.; Winfield, K.; Wikstrom, M.; Gard, S.; Upham, J.W.; Arest, C.F. Alveolar macrophages and CC chemokines are increased in children with cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, A.K.; Rao, S.; Range, S.; Eder, C.; Hofer, T.P.; Frankenberger, M.; Kobzik, L.; Brightling, C.; Grigg, J.; Ziegler-Heitbrock, L. Pivotal advance: Expansion of small sputum macrophages in CF: Failure to express marco and mannose receptors. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009, 86, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaman, M.M.; Gelrud, A.; Junaidi, O.; Regan, M.M.; Warny, M.; Shea, J.C.; Kelly, C.; O’Sullivan, B.P.; Freedman, S.D. Interleukin 8 secretion from monocytes of subjects heterozygous for the Δf508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene mutation is altered. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2004, 11, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sturges, N.C.; Wikstrom, M.E.; Winfield, K.R.; Gard, S.E.; Brennan, S.; Sly, P.D.; Upham, J.W. Monocytes from children with clinically stable cystic fibrosis show enhanced expression of Toll-like receptor 4. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2010, 45, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratner, D.; Mueller, C. Immune responses in cystic fibrosis: Are they intrinsically defective? Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 46, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirasophon, W.; Welihinda, A.A.; Kaufman, R.J. A stress response pathway from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus requires a novel bifunctional protein kinase/endoribonuclease (Ire1p) in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 1812–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Z.; Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Jolicoeur, E.M.; Kuroda, M.; Ron, D. Cloning of mammalian Ire1 reveals diversity in theER stress responses. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 5708–5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K. Divest yourself of a preconceived idea: Transcription factor ATF6 is not a soluble protein! Mol. Biol. Cell 2010, 21, 1435–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, R.J. Orchestrating the unfolded protein response in health and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Ron, D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 1999, 397, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patil, C.; Walter, P. Intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus: The unfolded protein response in yeast and mammals. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001, 13, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Matsui, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Okada, T.; Mori, K. XBP1 mrna is induced by ATF6 and spliced by Ire1 in response toER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell 2001, 107, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calfon, M.; Zeng, H.; Urano, F.; Till, J.H.; Hubbard, S.R.; Harding, H.P.; Clark, S.G.; Ron, D. Ire1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 2002, 415, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urano, F.; Bertolotti, A.; Ron, D. Ire1 and efferent signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 3697–3702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rutkowski, D.T.; Kaufman, R.J. A trip to the ER: Coping with stress. Trends Cell Biol. 2004, 14, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, H.; Matsui, T.; Hosokawa, N.; Kaufman, R.J.; Nagata, K.; Mori, K. A time-dependent phase shift in the mammalian unfolded protein response. Dev. Cell 2003, 4, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, A.L.; Shapiro-Shelef, M.; Iwakoshi, N.N.; Lee, A.H.; Qian, S.B.; Zhao, H.; Yu, X.; Yang, L.; Tan, B.K.; Rosenwald, A.; et al. XBP1, downstream of Blimp-1, expands the secretory apparatus and other organelles, and increases protein synthesis in plasma cell differentiation. Immunity 2004, 21, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriburi, R.; Jackowski, S.; Mori, K.; Brewer, J.W. XBP1: A link between the unfolded protein response, lipid biosynthesis, and biogenesis of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 167, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ron, D.; Oyadomari, S. Lipid phase perturbations and the unfolded protein response. Dev. Cell 2004, 7, 287–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haze, K.; Yoshida, H.; Yanagi, H.; Yura, T.; Mori, K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 3787–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, H.; Okada, T.; Haze, K.; Yanagi, H.; Yura, T.; Negishi, M.; Mori, K. ATF6 activated by proteolysis binds in the presence of NF-Y (CBF) directly to the cis-acting element responsible for the mammalian unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 6755–6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Tirasophon, W.; Shen, X.; Michalak, M.; Prywes, R.; Okada, T.; Yoshida, H.; Mori, K.; Kaufman, R.J. Ire1-mediated unconventional mRNA splicing and S2P-mediated ATF6 cleavage merge to regulate XBP1 in signaling the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, K.; Sato, T.; Matsui, T.; Sato, M.; Okada, T.; Yoshida, H.; Harada, A.; Mori, K. Transcriptional induction of mammalian ER quality control proteins is mediated by single or combined action of ATF6α and XBP1. Dev. Cell 2007, 13, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, M.; Li, M.; Mao, C.; Lee, A.S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers an acute proteasome-dependent degradation of ATF6. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 92, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadanaka, S.; Yoshida, H.; Sato, R.; Mori, K. Analysis of ATF6 activation in site-2 protease-deficient chinese hamster ovary cells. Cell Struct. Funct. 2006, 31, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, M.; Luo, S.; Baumeister, P.; Huang, J.M.; Gogia, R.K.; Li, M.; Lee, A.S. Underglycosylation of ATF6 as a novel sensing mechanism for activation of the unfolded protein response. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 11354–11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, H.; Uemura, A.; Mori, K. pXBP1(U), a negative regulator of the unfolded protein response activator pXBP1(S), targets ATF6 but not ATF4 in proteasome-mediated degradation. Cell Struct. Funct. 2009, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, S.G.; Urano, F.; Burcin, M.; Gromada, J. Stress hyperactivation in the β-cell. Islets 2010, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouroku, Y.; Fujita, E.; Tanida, I.; Ueno, T.; Isoai, A.; Kumagai, H.; Ogawa, S.; Kaufman, R.J.; Kominami, E.; Momoi, T. ER stress (PERK/eIF2α phosphorylation) mediates the polyglutamine-induced LC3 conversion, an essential step for autophagy formation. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talloczy, Z.; Jiang, W.; Virgin, H.W.; Leib, D.A.; Scheuner, D.; Kaufman, R.J.; Eskelinen, E.L.; Levine, B. Regulation of starvation- and virus-induced autophagy by the eIF2α kinase signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.; Lerner, A.G.; Vande Walle, L.; Upton, J.P.; Xu, W.; Hagen, A.; Backes, B.J.; Oakes, S.A.; Papa, F.R. Ire1α kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates. Cell 2009, 138, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ron, D.; Hubbard, S.R. How Ire1 reacts to ER stress. Cell 2008, 132, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, K.; Davis, R.J. JNK phosphorylation of Bim-related members of the Bcl2 family induces Bax-dependent apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2432–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Xiao, L.; Lang, W.; Gao, F.; Ruvolo, P.; May, W.S., Jr. Novel role for JNK as a stress-activated Bcl2 kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 23681–23688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.H.; Li, H.; Yasumura, D.; Cohen, H.R.; Zhang, C.; Panning, B.; Shokat, K.M.; Lavail, M.M.; Walter, P. Ire1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science 2007, 318, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkowski, D.T.; Arnold, S.M.; Miller, C.N.; Wu, J.; Li, J.; Gunnison, K.M.; Mori, K.; Sadighi Akha, A.A.; Raden, D.; Kaufman, R.J. Adaptation toER stress is mediated by differential stabilities of pro-survival and pro-apoptotic mRNAs and proteins. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K. Tripartite management of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 2000, 101, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.P.; Ron, D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the development of diabetes: A review. Diabetes 2002, 51, S455–S461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Bertolotti, A.; Zeng, H.; Ron, D. PERK is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Novoa, I.; Lu, P.D.; Calfon, M.; Sadri, N.; Yun, C.; Popko, B.; Paules, R.; et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palam, L.R.; Baird, T.D.; Wek, R.C. Phosphorylation of eIF2 facilitates ribosomal bypass of an inhibitory upstream ORF to enhance CHOP translation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 10939–10949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, S.; Baird, T.D.; Zhou, D.; Palam, L.R.; Spandau, D.F.; Wek, R.C. Both transcriptional regulation and translational control of ATF4 are central to the integrated stress response. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 33165–33174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyadomari, S.; Mori, M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004, 11, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B.; Scheuner, D.; Ron, D.; Pennathur, S.; Kaufman, R.J. CHOP deletion reduces oxidative stress, improves β cell function, and promotes cell survival in multiple mouse models of diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 3378–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marciniak, S.J.; Yun, C.Y.; Oyadomari, S.; Novoa, I.; Zhang, Y.; Jungreis, R.; Nagata, K.; Harding, H.P.; Ron, D. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 3066–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Z.; Kuroda, M.; Sok, J.; Batchvarova, N.; Kimmel, R.; Chung, P.; Zinszner, H.; Ron, D. Identification of novel stress-induced genes downstream of CHOP. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 3619–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinszner, H.; Kuroda, M.; Wang, X.; Batchvarova, N.; Lightfoot, R.T.; Remotti, H.; Stevens, J.L.; Ron, D. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 982–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, K.D.; Martindale, J.L.; Klotz, L.O.; Aw, T.Y.; Holbrook, N.J. GADD153 sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress by down-regulating Bcl2 and perturbing the cellular redox state. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Murthy, R.; Wood, B.; Song, B.; Wang, S.; Sun, B.; Malhi, H.; Kaufman, R.J. Er stress signalling through eIF2α and CHOP, but not Ire1α, attenuates adipogenesis in mice. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, C.W.; Kutzler, L.; Kimball, S.R.; Tabas, I. Toll-like receptor activation suppressesER stress factor CHOP and translation inhibition through activation of eIF2b. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blais, J.D.; Filipenko, V.; Bi, M.; Harding, H.P.; Ron, D.; Koumenis, C.; Wouters, B.G.; Bell, J.C. Activating transcription factor 4 is translationally regulated by hypoxic stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 7469–7482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wek, R.C.; Jiang, H.Y.; Anthony, T.G. Coping with stress: eIF2 kinases and translational control. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006, 34, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullinan, S.B.; Diehl, J.A. PERK-dependent activation of NRF2 contributes to redox homeostasis and cell survival following endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 20108–20117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullinan, S.B.; Zhang, D.; Hannink, M.; Arvisais, E.; Kaufman, R.J.; Diehl, J.A. NRF2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 7198–7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.H.; Gong, P.; Hu, B.; Stewart, D.; Choi, M.E.; Choi, A.M.; Alam, J. Identification of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) as an NRF2-interacting protein. Implication for heme oxygenase-1 gene regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 20858–20865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell 2010, 140, 900–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasnain, S.Z.; Lourie, R.; Das, I.; Chen, A.C.; McGuckin, M.A. The interplay between endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2012, 90, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.S.; Luo, K.L.; Shi, L. Endoplasmic reticulum stress interacts with inflammation in human diseases. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urano, F.; Wang, X.; Bertolotti, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chung, P.; Harding, H.P.; Ron, D. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase Ire1. Science 2000, 287, 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishitoh, H.; Matsuzawa, A.; Tobiume, K.; Saegusa, K.; Takeda, K.; Inoue, K.; Hori, S.; Kakizuka, A.; Ichijo, H. Ask1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.J. Signal transduction by the JNK group of map kinases. Cell 2000, 103, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Han, Z.; Couvillon, A.D.; Kaufman, R.J.; Exton, J.H. Autocrine tumor necrosis factor α links endoplasmic reticulum stress to the membrane death receptor pathway through Ire1α-mediated NF-κB activation and down-regulation of TRAF2 expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 3071–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Kokoeva, M.V.; Inouye, K.; Tzameli, I.; Yin, H.; Flier, J.S. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konner, A.C.; Bruning, J.C. Toll-like receptors: Linking inflammation to metabolism. Trends. Endocrinol. Metab. TEM 2011, 22, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinon, F.; Chen, X.; Lee, A.H.; Glimcher, L.H. Tlr activation of the transcription factor XBP1 regulates innate immune responses in macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savic, S.; Ouboussad, L.; Dickie, L.J.; Geiler, J.; Wong, C.; Doody, G.M.; Churchman, S.M.; Ponchel, F.; Emery, P.; Cook, G.P.; et al. Tlr dependent XBP-1 activation induces an autocrine loop in rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. J. Autoimmun. 2014, 50, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, C.W.; Cui, D.; Arellano, J.; Dorweiler, B.; Harding, H.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Ron, D.; Tabas, I. Adaptive suppression of the ATF4-CHOP branch of the unfolded protein response by Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 1473–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischof, L.J.; Kao, C.Y.; Los, F.C.; Gonzalez, M.R.; Shen, Z.; Briggs, S.P.; van der Goot, F.G.; Aroian, R.V. Activation of the unfolded protein response is required for defenses against bacterial pore-forming toxin in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiringer, K.; Treis, A.; Fucik, P.; Gona, M.; Gruber, S.; Renner, S.; Dehlink, E.; Nachbaur, E.; Horak, F.; Jaksch, P.; et al. A TH17- and TH2-skewed cytokine profile in cystic fibrosis lungs represents a potential risk factor for pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 187, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfield, T.L.; Panuska, J.R.; Konstan, M.W.; Hilliard, K.A.; Hilliard, J.B.; Ghnaim, H.; Berger, M. Inflammatory cytokines in cystic fibrosis lungs. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995, 152, 2111–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hentschel, J.; Jager, M.; Beiersdorf, N.; Fischer, N.; Doht, F.; Michl, R.K.; Lehmann, T.; Markert, U.R.; Boer, K.; Keller, P.M.; et al. Dynamics of soluble and cellular inflammatory markers in nasal lavage obtained from cystic fibrosis patients during intravenous antibiotic treatment. BMC Pulm. Med. 2014, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osika, E.; Cavaillon, J.M.; Chadelat, K.; Boule, M.; Fitting, C.; Tournier, G.; Clement, A. Distinct sputum cytokine profiles in cystic fibrosis and other chronic inflammatory airway disease. Eur. Respir. J. 1999, 14, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, D.P.; Ziady, A.G.; Shank, S.L.; Eastman, J.F.; Davis, P.B. The triterpenoid CDDO limits inflammation in preclinical models of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2009, 297, L828–L836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, K.; Hayes, E.; Keenan, J.; Henry, M.; Meleady, P.; Molloy, K.; Jundi, B.; Bergin, D.A.; McCarthy, C.; McElvaney, O.J.; et al. A neutrophil intrinsic impairment affecting Rab27a and degranulation in cystic fibrosis is corrected by CFTR potentiator therapy. Blood 2014, 124, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borot, F.; Vieu, D.L.; Faure, G.; Fritsch, J.; Colas, J.; Moriceau, S.; Baudouin-Legros, M.; Brouillard, F.; Ayala-Sanmartin, J.; Touqui, L.; et al. Eicosanoid release is increased by membrane destabilization and CFTR inhibition in Calu-3 cells. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vij, N.; Mazur, S.; Zeitlin, P.L. CFTR is a negative regulator of NFκB mediated innate immune response. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodas, M.; Vij, N. The nf-κb signaling in cystic fibrosis lung disease: Pathophysiology and therapeutic potential. Discov. Med. 2010, 9, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tabary, O.; Boncoeur, E.; de Martin, R.; Pepperkok, R.; Clement, A.; Schultz, C.; Jacquot, J. Calcium-dependent regulation of NF-κB activation in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Cell Signal. 2006, 18, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Beyer, B.A.; Lewis, C.; Nadel, J.A. Normal CFTR inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent pro-inflammatory chemokine production in human airway epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingue, J.C.; Ao, M.; Sarathy, J.; Rao, M.C. Chenodeoxycholic acid requires activation of EGFR, EPAC, and Ca2+ to stimulate CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion in human colonic T84 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2016, 311, C777–C792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Su, X. CFTR regulates acute inflammatory responses in macrophages. QJM 2015, 108, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.; Lang, Q.; Huijuan, L.; Jiang, X.; Ming, Y.; Huaqin, S.; Wenming, X. CFTR deletion in mouse testis induces VDAC1 mediated inflammatory pathway critical for spermatogenesis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hybiske, K.; Fu, Z.; Schwarzer, C.; Tseng, J.; Do, J.; Huang, N.; Machen, T.E. Effects of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and Δf508CFTR on inflammatory response, ER stress, and Ca2+ of airway epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2007, 293, L1250–L1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoszewski, R.; Rab, A.; Jurkuvenaite, A.; Mazur, M.; Wakefield, J.; Collawn, J.F.; Bebok, Z. Activation of the unfolded protein response by Δf508 CFTR. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008, 39, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.D.; Dohrman, A.F.; Gallup, M.; Miyata, S.; Gum, J.R.; Kim, Y.S.; Nadel, J.A.; Prince, A.; Basbaum, C.B. Transcriptional activation of mucin by pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagel, S.D.; Sontag, M.K.; Wagener, J.S.; Kapsner, R.K.; Osberg, I.; Accurso, F.J. Induced sputum inflammatory measures correlate with lung function in children with cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. 2002, 141, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, A.G.; Ehre, C.; Button, B.; Abdullah, L.H.; Cai, L.H.; Leigh, M.W.; DeMaria, G.C.; Matsui, H.; Donaldson, S.H.; Davis, C.W.; et al. Cystic fibrosis airway secretions exhibit mucin hyperconcentration and increased osmotic pressure. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 3047–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weldon, S.; McNally, P.; McElvaney, N.G.; Elborn, J.S.; McAuley, D.F.; Wartelle, J.; Belaaouaj, A.; Levine, R.L.; Taggart, C.C. Decreased levels of secretory leucoprotease inhibitor in the pseudomonas-infected cystic fibrosis lung are due to neutrophil elastase degradation. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 8148–8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, D.J.; Weldon, S.; Taggart, C.C. Antiproteases as therapeutics to target inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Open Respir. Med. J. 2010, 4, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.; Wright, A.K.; Montiero, W.; Ziegler-Heitbrock, L.; Grigg, J. Monocyte chemoattractant chemokines in cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2009, 8, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, C.; Zaman, M.M.; Jones, A.B.; Freedman, S.D. Alterations in immune response and regulation in cystic fibrosis macrophages. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2008, 7, 6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruscia, E.M.; Zhang, P.X.; Ferreira, E.; Caputo, C.; Emerson, J.W.; Tuck, D.; Krause, D.S.; Egan, M.E. Macrophages directly contribute to the exaggerated inflammatory response in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator−/− mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009, 40, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keiser, N.W.; Gabdoulkhakova, A.; Riazanski, V.; Nelson, D.J.; Engelhardt, J. Ferret alveolar macrophage function is dependent on CFTR. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2014, 49, 278–279. [Google Scholar]

- Sorio, C.; Buffelli, M.; Angiari, C.; Ettorre, M.; Johansson, J.; Vezzalini, M.; Viviani, L.; Ricciardi, M.; Verze, G.; Assael, B.M.; et al. Defective CFTR expression and function are detectable in blood monocytes: Development of a new blood test for cystic fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Weert-van Leeuwen, P.B.; van Meegen, M.A.; Speirs, J.J.; Pals, D.J.; Rooijakkers, S.H.; van der Ent, C.K.; Terheggen-Lagro, S.W.; Arets, H.G.; Beekman, J.M. Optimal complement-mediated phagocytosis of pseudomonas aeruginosa by monocytes is cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-dependent. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 49, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, J. CFTR: Helping to acidify macrophage lysosomes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 908–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessich, J.L.; Nymon, A.B.; Moulton, L.A.; Dorman, D.; Ashare, A. Low levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 contribute to alveolar macrophage dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonin-Le Jeune, K.; Le Jeune, A.; Jouneau, S.; Belleguic, C.; Roux, P.F.; Jaguin, M.; Dimanche-Boitre, M.T.; Lecureur, V.; Leclercq, C.; Desrues, B.; et al. Impaired functions of macrophage from cystic fibrosis patients: CD11B, TLR-5 decrease and sCD14, inflammatory cytokines increase. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garg, A.D.; Kaczmarek, A.; Krysko, O.; Vandenabeele, P.; Krysko, D.V.; Agostinis, P. ER stress-induced inflammation: Does it aid or impede disease progression? Trends Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, C.M.P.; Lubamba, B.A. Role of IRE1α/XBP-1 in Cystic Fibrosis Airway Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18010118

Ribeiro CMP, Lubamba BA. Role of IRE1α/XBP-1 in Cystic Fibrosis Airway Inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(1):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18010118

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Carla M. P., and Bob A. Lubamba. 2017. "Role of IRE1α/XBP-1 in Cystic Fibrosis Airway Inflammation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 1: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18010118