1. Introduction

Inorganic clathrate phases which can be described as all-inorganic frameworks with guest atoms have been of interest for a wide variety of applications, including thermoelectrics, Li-ion batteries, hydrogen storage, and photovoltaics [

1]. In particular, silicon (Si)-containing clathrate phases are of significant interest because of being earth abundant and environmentally benign. The alkaline earth-containing group 13-Si light element clathrates have been reviewed recently [

2]; therefore, this short review provides an update on the alkali metal-containing group 13-Si compounds crystallizing in the clathrate type I structure.

Na

8-xSi

46 is the first observed silicon-based compound discovered to crystalize in the type I clathrate structure. The structure can be described as having a covalently bonded silicon (Si) framework with sodium (Na) as the guest atom centered within the polyhedra [

3]. The structure has been described in detail many times and consists of Na cations encapsulated in tetrahedrally bonded silicon framework (cubic space group, Pm-3n), shown in

Figure 1. The framework contains 46 atoms with three unique sites typically referred to by their Wyckoff positions 6

c, 16

i, and 24

k. The eight guest atoms in the unit cell are located at the Wyckoff positions 2

a and 6

d, which centers the two types of polyhedra found in type I clathrate: 20-vertex pentagonal dodecahedra and 24-vertex tetrakaidecahedra. Following the discovery of Na

8-xSi

46, the alkali metals series (A = K, Rb, Cs) of type I clathrate were synthesized from the elements by annealing, with the Cs clathrate being a high pressure phase [

4,

5]. The alkali metals´ guest atoms in the silicon-containing clathrate phases donate electrons, and these phases are metallic [

1].

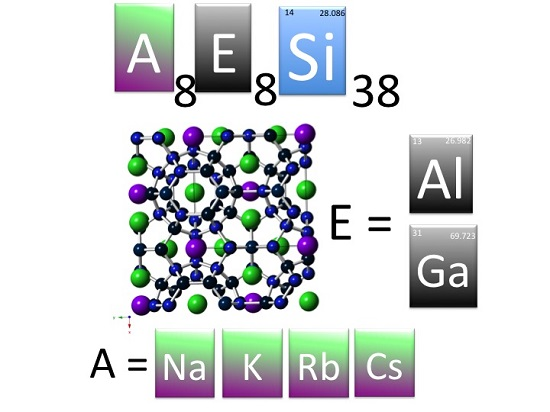

Clathrate phases with the composition A

8E

8Si

38 (A = alkali metal, E = Al, Ga, In) are considered to be electron-balanced phases as the compounds contain an equivalent amount of group 13 elements to accept the donated electrons from guest atoms and were predicted to show semiconducting behavior [

7,

8]. The phases prepared to date are A

8E

8Si

38 (A = Na [

9,

10], K [

7,

10,

11,

12], Rb [

8], Cs) [

13,

14] and have been shown experimentally to be semiconducting when the composition is near the expected; the E = In and A = Na, E = Ga phases have not been prepared.

Table 1 provides the lattice parameters of the A

8E

8Si

38 compounds reported to date. The only borosilicide compound with type I clathrate structure is K

7B

7Si

39 [

15], although boron has been incorporated into a type I Ba

8Al

16Si

30 clathrate at dopant levels [

16]. Besides group 13 substitutions in the Si framework, silicon clathrates containing earth abundant transition metal substitutions A

8M

II4Si

42 have been prepared with M

II = Zn: K

8Zn

3.5Si

42.5 and Rb

7.9Zn

3.6Si

42.4 [

17]. While the heavier group 14 elements are not a topic of this review, it is noteworthy that, while most of the compositions described are n-type semiconductors, there is at least one example of a p-type compound with Sn, K

8Ga

8.5Sn

37.5 [

18]. Since thermoelectric devices need both n- and p-type semiconductors, the possibility that both can be prepared provides additional incentive for developing the chemistry of the silicon clathrates further. Type II clathrate phases composed of group 13 elements and Si have also been prepared, Cs

8Na

16Ga

23Si

113, Rb

8.4Na

15.6Ga

20Si

116 [

19], and Cs

8Na

16Al

24Si

112 [

20], demonstrating new horizons for further development of alkali metal-containing clathrates. Aside from structure, only the thermoelectric transport properties of the type II clathrate Cs

8Na

16Al

24Si

112 have been reported to date [

20].

2. Theory

Interest in these electron-precise clathrate structures, A

8E

8Si

38, has resulted in theoretical investigations of their formation energies, bandgaps and other transport properties [

11,

21,

22,

23]. These silicon-containing clathrates are of interest for both photovoltaics and thermoelectrics. The interest in photovoltaics is a result of the possibility of a direct bandgap in the appropriate range for solar energy conversion [

11,

12,

13]. Even without being direct gap semiconductors, the idea that charge recombination can be reduced or minimized has led to a resurgence of interest [

22]. Clathrate structures for thermoelectric applications have been considered ideal Phonon Glass Electron Crystal (PGEC) materials [

24]. PGEC has been an important concept for designing efficient thermoelectric materials [

23]. The idea is that a material can have properties similar to a glass for phonons and as a crystal for electrical transport. This allows for low thermal conductivity and high electrical conductivity: two important parameters for efficient thermoelectric materials [

23]. Silicon and earth abundant clathrate phases have been particularly desirable as possible PGECs, as many of the most efficient materials for direct heat to electrical conversion contain critical or environmentally unfriendly elements.

In general, clathrate structures form a cage network that encapsulates an element referred to as the guest. The optimal material for thermoelectric applications would be where the guest atom is weakly bound to the cage and provides a vibrational mode referred to as a “rattling mode” that can scatter the lattice phonon mode. While reduction in thermal conductivity in these type I clathrate phases has been attributed to the guest vibrational modes, first principle calculations also demonstrate that structural disorder of the covalently bonded cages plays an important role in reducing the thermal conductivity [

11,

22].

The band structures of the series A

8E

8Si

38 (A = Na, K, Rb, Cs; E = Al, Ga, In) were calculated using density functional theory [

25,

26]. The calculations indicate that the bandgap remained indirect, but became larger with the heavier guest alkali atom with an estimated gap of ~0.9 eV for A = Na and ~1.36 eV for A = Cs. The calculations indicate that the bandgap was not very sensitive to the group 13 element, E, but again followed the principle of becoming slightly larger with heavier elements. The authors noted that the theoretical predictions might not be valid because of site-specific positioning of the atoms, vacancies, or deviations from ideal stoichiometry, but they are fairly close to the experimental values. Additional theoretical calculations on the series, focusing on the group 13 site preferences, was reported [

21]. Site specificity of the group 13 element within the clathrate I framework has been noted experimentally, so detailed calculations are of great interest. As mentioned above, there are three framework sites that the group 13 element could occupy. In a simplistic view, the group 13 element occupies the site most likely to avoid any E-E bonding interactions in order to better satisfy valence [

27].

Figure 2 shows how the specific sites that will be discussed further are interconnected with the Wyckoff nomenclature indicated. In these type I clathrates, the group 13 element favors the 6

c framework site with a small amount on the 24

k site in the ratio of approximately 5:3, when A = K, Rb, Cs. This is consistent with experimental observations for these alkali metal clathrates [

7,

8,

9,

11,

13].

Theoretical calculations suggest that these phases should have applications in photovoltaics with K

8Al

8Si

38 showing a quasi-direct bandgap of ~ 1 eV with relatively high mobilities determined [

22]. Additionally, investigation of the valence band and conduction band-wave functions revealed clear distinction in spatial location, thereby suggesting low probability of charge carrier recombination and efficient energy conversion. The transport properties related to thermoelectrics have also been calculated for the E = Ga phases and efficiencies predicted with the best energy conversion phase being hole-doped Cs

8Ga

8Si

38 [

21]. Overall, there has been significant progress in both theoretical and experimental investigations suggesting that fundamental understanding of the physics and chemistry will be advanced along with the practical applications of these materials [

23].

3. Structure

Powder X-ray diffraction was performed on the binary type I clathrate phases K

7.62(1)Si

46 and Rb

6.15(2)Si

46 to examine their crystal structure [

4]. The host atom sites have no vacancies revealed by Rietveld refinement of the X-ray powder diffraction pattern; the Si frameworks are fully occupied similar with that of Na

8Si

46 [

28]. Fully occupied framework sites are commonly noticed in alkali metals-Si clathrate phases; in the contrast, Ge or Sn clathrates with alkali metals have been reported to possess vacancies at the framework’s 6

c site [

8,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Ramachandran et al. attributed the difference in the framework vacancy formation to the weaker homoatomic bonding descending the group in the periodic table [

4].

Compounds with the stoichiometry A

8E

8Si

38, A = Na, K, R, Cs and E = Al and Ga have been prepared to date and their lattice parameters are provided in

Table 1. In ternary clathrate phases, the substitution preference of silicon framework sites (6

c, 16

i, 24

k) can affect the band structure and transport properties significantly. In the A

8E

8Si

38 framework, Ga occupancy can be distinguished by single-crystal X-ray diffraction as Ga and Si atoms have electron densities that provide significantly different scattering factors. For A = K, Rb, Cs compounds, the Ga occupancy ratio at the 6

c site is in the range of 61%~46% and 17%~20% at the 24

k site. At the 16

i site, the Ga occupancy ratio is low, only 1%~2%, which indicates Ga preference for the 6

c site (

Table 2) [

13]. Similarly, Zn also shows site preference for the 6

c site and avoids substitution on the 16

i site [

17]. Distinguishing Al from Si in A

8Al

8Si

38 (A = K, Rb, Cs) is difficult, so neutron powder diffraction was performed to study the Al/Si mixed occupancy ratios [

14]. Even with neutron diffraction, it is difficult to distinguish Al from Si. Rietveld refinement of the neutron powder diffraction gave the total chemical formula of A/Al/Si close to the nominal stoichiometry 8/8/38. Al’s site occupancy fraction (

s.o.f.) is shown in

Table 2 to compare with the Ga’s

s.o.f. The group 13 atoms’ preference to occupy 6

c site is attributed to the fact that there is no direct bonding between 6

c sites (shown in

Figure 2), and group 13 atoms occupy these specific sites in order to avoid the disfavored 13-13 bonds [

27]. Consistent with what is found in the A

8Ga

8Si

38 samples, Al prefers 6

c site and avoids 16

i. Additionally, as the unit cell expands with larger guest atoms from K to Cs, the

s.o.f. of Al at the 6

c site decreases. This is similar to what has been discovered in Ba

8Al

xSi

46-x samples by neutron diffraction study; when

x increases from 6 to 15, to accommodate more Al atoms, more Al atoms go to 24

k site [

6,

34].

The theoretical calculations discussed above also identified the two most stable configurations as being consistent with what is found experimentally: 6 Al atoms at 6c and 2 Al atoms at 16i, or 5 Al atoms at 6c, 2 Al atoms at 24k and 1 Al atom at 16i.

Na

8Al

8Si

38 has only been prepared by kinetically controlled thermal decomposition (KCTD) of a mixture of NaSi [

35] and NaAlSi [

36]. This phase cannot be prepared by conventional synthetic routes so may be a metastable or kinetically stable phase. Small single crystals and phase-pure sample were obtained. The lattice parameter vs. unit cell volume, shown in

Figure 3, is in good agreement with that expected for A = Na when compared to A

8Al

8Si

38 (A = K, Rb, Cs). Rietveld and single-crystal refinements indicate that Al preferentially resides at the 6

c site in the ratio Al:Si 0.79:0.21. The 24

k site to a significantly lesser extent with the ratio Al:Si 0.13:0.87 and no evidence for Al on the 16

i site. This result is similar to what has been determined for A

8Al

8Si

38.

In the case of K

7B

7Si

39, where B is a much smaller atom than Si, B is found to substitute 16

i sites by single-crystal X-ray diffraction refinement, while only Si is found at 6

c and 24

k sites [

15]. This is very different than that observed for A

8E

8Si

38 (E = Al, Ga). In

Figure 2, it can be seen that the six-membered ring of the 24-vertex tetrakaidecahedral cage, composed of 6

c and 24

k sites, has bond angles deviating from an ideal tetrahedron and therefore creates chemical stress if substituted by the small B atom. Therefore, B atoms have a preference for the 16

i site [

15].

In the type I clathrate crystal structure, the guest atom Wyckoff nomenclature is 2

a inside the 20-vertex pentagonal dodecahedral cages and 6

d inside the 24-vertex tetrakaidecahedral cages. Large anisotropic atomic displacement parameters (ADPs) have been reported for the 6

d sites guest atoms, and therefore they are considered as rattler and contribute to phonon scattering. For compounds K

7.62(1)Si

46 and Rb

6.15(2)Si

46, when guest atom vacancy is present, occupancy at 6

d site is preferred and 2

a site has lower

s.o.f, 88.5(4)% at K

7.62(1)Si

46 2

a site and 21.8(5)% at Rb

6.15(2)Si

46 2

a site [

4]. Similarly, in sample Cs

7.8(1)Si

46,

s.o.f of 2

a site is 0.881(4) while 6

d site is close to fully occupied [

5].

Although this review is concerned with the alkali metal guest group 13 Si clathrate type I phases, it is informative to review the guest ADPs for Ba

8Al

xSi

46-x, since the amount of Al can vary from x ~ 8–15. Neutron powder diffraction at 35 K of Ba

8Al

xSi

46-x showed that when Al composition increases from 8 to 15, the anisotropic ADPs behave differently as presented in

Figure 4. In the Figure, U

11 and U

33 are the two thermal displacement parameters parallel to the six-membered ring in the E

24 cage, and U

22 is direction perpendicular to six-membered ring. As the Al composition increases and the cage volume increases as well, U

22 changed from a value larger than U

11, U

33 to a value smaller than those two. As shown in

Figure 4, the thermal ellipsoid changes critically when Al compositions increased [

6]. However, compare the anisotropic ADPs of 6

d site in the case of A

8Ga

8Si

38 and A

8Ga

8Si

38 (A = K, Rb, Cs): the alkali metals at 6

d sites behave similarly with those of Ba

8Al

15Si

31 instead of Ba

8Al

8Si

38, with the larger U elongated in the directions parallel to the six-membered ring (U

11, U

33) [

13,

14].

Unlike Ba

8Al

xSi

46-x, the composition for A

8Al

8Si

38 appears to be fixed [

14,

37], although minor adjustments appear to be possible [

10,

38]. Therefore, in order to tune the electronics, the composition K

8-xBa

xAl

8+xSi

38-x was investigated using metal hydrides for the alkali and alkaline earth metals and Al/Si arc melted mixtures heated together. The nominal compositions of x = 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 were investigated. The structures were investigated for each composition with synchrotron radiation at 295 and 100 K. The 2

a site with the smaller volume polyhedron was mostly substituted by Ba

2+ rather than K

+ guest atoms, consistent with the smaller ionic radius of Ba

2+ [

37]. Similar to the anisotropic ADP described above for the guest atom at the 6

d site, the guest atom in the 6

d site shows a larger displacement than the direction perpendicular to the six-membered ring of the 24-vertex cage. This is also observed for the Zn-containing phases [

39].

4. Properties

The band structures of A

8Ga

8Si

38 were first calculated using density-functional theory [

25,

26] and determined to be indirect bandgap semiconductors with the calculated bandgaps increasing with increasing mass of A. K

8E

8Si

38 for E = Al, Ga, In was also calculated and showed a slight increase in bandgap with decreasing mass of E. Overall, the gaps were calculated to be 0.45 eV for Na

8Ga

8Si

38 to 0.89 for Cs

8Ga

8Si

38 while Eg value of Si with the diamond structure is calculated to be 0.65 eV. Since the experimental value of Eg of Si is 1.12 eV, these calculated values are adjusted according, corresponding to 0.92 and 1.36 eV for Na

8Ga

8Si

38 and Cs

8Ga

8Si

38, respectively. The experimental determination was for K

8Ga

8Si

38 and the optical bandgap was estimated to be indirect at 1.2 eV [

12,

40]. With a higher level of theory and site preferences of E similar to that found experimentally, the bandgap of K

8Al

8Si

38 was found to be larger than 1 eV [

11]. The experimental measurements of A

8Ga

8Si

38 follow the predicted trend, but are larger than the original calculations [

13]. The values of the bandgap for K

8Al

8Si

38 and A

8Ga

8Si

38 (A = K, Rb, Cs) were determined from surface photovoltage spectroscopy [

41,

42] indicated as n-type and are in the range of 1.1–1.4 eV [

13]. Na

8Al

8Si

38 indicated an optical bandgap of 0.64 eV [

9].

There has been significant interest and recent progress in the measurement of thermoelectric properties of these clathrates. Theoretical calculations indicated that that the dimensionless figure of merit, zT, for optimally doped compounds can reach 0.5 at 600 K. Hole-doped Cs

8Ga

8Si

38 is predicted to provide a zT of 0.75 at 900 K. The figure of merit is a dimensionless parameter that provides a way to distinguish a favorable material for high performance as it combines the following thermoelectric parameters: Seebeck coefficient, resistivity, and thermal conductivity for a specific absolute temperature.

Table 3 shows the data reported at 300 K for comparison. The thermal conductivity in all cases is low and the Seebeck coefficients are reasonable, but the electrical resistivity is too high in most cases. In the example of K

8Al

8Si

38, it is apparent from the reported results that the precise stoichiometry greatly affects the electrical resistivity, as can be seen in

Table 3 with the various entries [

13,

14,

37] and for the one example that is slightly off stoichiometry, K

8Al

7Si

39 [

38].

Since the K

8Al

8Si

38 phase showed the most promise with ease of synthesis, further optimization of that phase was considered. As indicated above, one method to optimize the transport properties is to focus on the Al-Si ratio and K

8Al

7Si

39 shows the promise of this approach. Another method for decreasing the resistivity of the stoichiometric A

8E

8Si

38 samples is to attempt to control the electron donation to the framework with mixed cations. The mixed alkali metal-alkaline earth Al-Si clathrate phases, K

8-xBa

xAl

8+xSi

38-x (x = 0, 1, 1.5, 2) were prepared and their thermoelectric properties measured. The K

8Al

8Si

38 used in this study [

37] had slightly different lattice parameters than those measured previously attributed to slightly different stoichiometry [

13,

14]. Thermogravimetric/differential scanning calorimetry (TG/DSC) measurements indicated that the K

8Al

8Si

38 phase was stable up to 900 K (

Figure 5), so temperature-dependent studies up to 900 K were performed on about 90% dense pressed pellets. The samples showed significantly lower electrical resistivities compared with stoichiometric A

8E

8Si

38 samples.

Preparing dense pellets of clathrates via spark plasma sintering is challenging, especially those with low melting points or potentially volatile guest atoms. In the case of K

8Al

8Si

38, the samples decompose as K volatiles with the application of SPS. Therefore, while pellets with density of 80%–85% could be prepared for low temperature measurements (4 mm diameter pellets), high temperature spark plasma sintering of larger pellets provided samples with lower densities thereby making it difficult to obtain reliable experimental measurements of thermal conductivity. Pressed pellets of K

8-xBa

xAl

8+xSi

38-x (x = 0, 1, 1.5, 2) were prepared and the Seebeck coefficient and electrical resistivity measured (

Figure 6) from room temperature to 1000 K.

Figure 6 shows that the K

8-xBa

xAl

8+xSi

38-x samples are all n-type with the lowest resistivity for x = 1.5. The resistivities do not correlate with x, as precise control over the Al-Si content is difficult to achieve with the hydride synthesis described in the manuscript [

37]. The power factor for the same samples is provided in

Figure 7, indicating that x = 1.5 is the best sample in the series.

If lattice thermal conductivities are extrapolated based on the low temperature measurements, and electronic thermal conductivities are calculated according to the Wiedemann-Franz relationship, the zT can be estimated at ~0.35 at 873 K, a significant value for an all earth abundant material, providing inspiration for those working on novel clathrates for high zT in a non-toxic, earth abundant material [

37].

5. Synthesis

The simplest routes to the phases A

8E

8Si

38 involve simply reacting the element in sealed Nb/Ta tubes at high temperatures. In particular, the gallium phases of A = K, Rb, Cs; E = Ga can be prepared in this manner. K

8Ga

8Si

38 and Rb

8Ga

8Si

38 were synthesized from on-stoichiometry reactions between pure elements in Nb/Ta tube heated to 1270 K and annealed at 970 K and their type I clathrate structure were reported [

7,

8]. K

7B

7Si

39 can also be prepared from the elements, heating the mixtures in a Ta tube, encapsulated in fused silica, at about 1100 K. However, the reaction was not complete, and the impurities were removed by reaction with sodium hydroxide and concentrated acid [

7,

12]. To date, there has been little or no follow-up of the boron-containing phases.

Na

8Al

8Si

38 can be synthesized in spark plasma sintering (SPS) and kinetically controlled thermal decomposition (KCTD) reactions with NaAlSi and NaSi mixture [

9]. This route can lead to single crystals or phase-pure microcrystalline powders. Using different precursor rations, Na

8Al

xSi

46-x compositions were investigated, but while the diffraction peaks broadened, there was no direct evidence for a composition other than x ~ 8.

Figure 8 shows a schematic of how the reaction is performed. The NaAlSi and NaSi mixture is placed in a custom-designed stainless steel apparatus under a uniaxial pressure of 20 MPa and heated for 9 h under dynamic vacuum (10

−6 torr) at 953 K. During this reaction, the Na is removed in a chemically controlled manner from the NaAlSi/NaSi mixture via interaction with a graphite flake which is spatially separated from the mixture via NaCl. The NaCl stops a direct reaction of the Na with the graphite, so it is presumed to be a vapor-phase interaction of Na with the graphite flake. This procedure has been described in detail for the synthesis of Na-Si clathrate phases [

43]. The product is carefully washed with ethanol and distilled water and dried in air. Caution should be used as NaSi can react violently with water.

High pressure synthesis of Na

8Al

xSi

46-x has also been investigated employing a mixture of NaSi, Al and Si as reagents, but only x~0.5 was prepared at 5.5 GPa and 1570 K [

10]. This low x phase could not be produced as a phase-pure product and further synthetic efforts are necessary to provide a conclusion concerning whether x can be varied in this system. K

8Al

8Si

38 was reported to be synthesized from KH and arc-melted Al/Si, sealed in a Ta tube jacketed in fused silica at 973 K. Ball milling KH and Al/Si together subsequent to heating enhanced the sample purity [

13]. K

8-xBa

xAl

8+xSi

38-x could be prepared from ball milling BaH

2 with KH and arc-melted Al/Si in the same manner as described above [

37]. While this route provided fairly good control over the stoichiometry, caution should be taken when handling the metal hydrides that can react violently with water. A

8Ga

8Si

38 (A = K, Rb, Cs) can be prepared from the pure elements reaction in a Ta tube jacketed in a fused silica ampoule at 973 K [

13]. Excess alkali metals were used to obtain phase-pure samples and carefully removed with ethanol from samples. Caution when handling these samples is necessary as unreacted alkali metal can react violently with ethanol. Typically, the samples were initially allowed to oxidize slowly by exposing them over time to air, then the samples were covered with hexane to protect from water and ethanol slowly added before the mixture was sonicated. In the case of Cs

8Cd

4Sn

42, phase-pure samples could be prepared by simple heating and annealing in a sealed metal tube [

44]. It is possible that the Cd-containing Si or Ge phases can be prepared in a similar manner. Single-phase A

8Al

8Si

38 (A = K, Rb, Cs) can also be prepared from Al and the respective alkali-metal halide salt flux, as reported by Baran et al. Similarly, Cs

8-xGa

8-ySi

38+y was synthesized from a stoichiometric reaction of the elements in an alkali metal halide flux, while K

8Zn

3.5Si

42.5 and Rb

7.9Zn

3.6Si

42.4 were synthesized using a combined alkali metal halide/zinc flux [

14,

17]. Excess halides flux can be removed by dissolving in water as all of the clathrate phases are air stable. Unlike the Sn [

45] or Ge clathrates [

46], this is the only flux route reported to date for the synthesis of alkali metals containing group 13-silicon clathrates and, while it is reported to provide enough sample for pressed powders, it results in small crystals which are not sufficient for thermoelectric property measurements [

14,

17]. Therefore, there is still a significant challenge to grow large single crystals of good quality for property measurements of the Si clathrates with alkali metal guests.