Abstract

Currently, companies and SMEs (small and medium enterprises) are looking to be more competitive. To achieve this, they are adopting new business models and strategies that allow them to move towards sustainability. Strategies such as CSR (Corporate social responsibility) and supply chain management have become essential for ensuring a company’s permanence and financial consolidation. The literature has stated that theories on stakeholders and sustainability are fundamental pillars for the development and sustained growth of business. The purpose of this article is to examine the effects of CSR and SCMM (supply chain management) on innovation, image and reputation, and, in turn, their influences on profitability in SMEs. An additional purpose is to verify the bidirectional relationship that exists between CSR and SCM in SMEs. This research was based on a sample of 143 companies in the city of Guaymas Sonorain Mexico. For the analysis and validation of the results, we used the ordinal least squares method (OLS) through multiple linear regressions and SEM (Structural Equation Modeling) statistical technique based on the variance, through PLS (Partial Least Squares) (using SmartPLS version 3.2.6 Professional). The findings show that SMEs that develop social and sustainable practices increase their level of innovation, and improve their image, their reputation, and their financial profitability. The results also indicate that CSR and SCM have a strong interdependence. This work contributes mainly to the development of the literature on stakeholders and sustainability.

1. Introduction

The evolution of the economy, technological trends, and the socioeconomic demands of communities have influenced and affected the actions of business owners in an important way [1,2]. These factors have unleashed a high degree of competitiveness and accelerated globalization of markets, forcing companies to improve their processes and their products, and to know their consumers in greater depth [3,4,5]. To face these changing manifestations of the micro- and macroenvironment, companies are incorporating into their business models renewed and more efficient strategies, such as social responsibility and certification of their processes and innovation practices [6,7]. At present, more and more companies are developing practices based on social marketing to penetrate new markets and obtain faster performance gains [8,9,10]. Undoubtedly, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and supply chain management are among the most successful business actions to have emerged in the last two decades [11,12], as determinant and necessary practices for the competitiveness and survival of companies [11].

The literature shows that CSR has been one of the most studied theoretical currents since the middle of the last century, undergoing evolution and achieving ever greater importance among researchers and directors of companies [13,14]. However, despite undergoing extensive study, this theory remains the subject of debate and discussion by experts [15]. The theories with the greatest presence in the literature involve those interest groups (stakeholders) focused on the shared benefits among shareholders, employees, customers, and suppliers [16]. This theory promotes CSR practices based on the “triple bottom line” for business sustainability [17]. The theory of sustainability is focused on the practice of social, economic, and environmental actions to obtain long-term profitability for businesses [14]. Another important theory is that of the shareholders focused on the free market legal competition, which has the purpose of obtaining greater financial and economic returns for shareholders [18,19]. Some theoretical currents have been identified focusing on the search for improved financial and economic performance for organizations. For example, Friedman [19] and Porter and Kramer [20] argued that some social and philanthropic practices lead to the reduction of productivity. Contrary to this, Carroll and Shaban [13] and Engert, Rauter, and Baumgartner [21] argued that the social, economic, and environmental actions of CSR are positively related to the profitability of organizations.

The companies aimed at the search for greater financial and organizational returns are incorporating into their processes the management of the supply chain. This is because this is a key element for the success of the sustainability strategy, and is an efficient guide for companies’ voluntary CSR practices [22,23]. These assertions are contemplated in the theories on sustainability and stakeholders, which have as a fundamental objective meeting the present and future needs of the stakeholders of a company [24]. To meet these expectations, supply chain management plays a leading role in the internal processes of organizations [25,26]. The main functions and responsibilities of the supply chain management (SCM) are environmental performance, controlling the quality of goods and services (supplies) of suppliers, and regulating delivery times and improving the quality of the products offered by the company [27,28]. With the globalization of markets, large corporations have adopted ISO (International Organization for Standardization) certifications in their processes (mainly from the ISO 14000 family) to meet their social obligations, considering the demands of the market and complying with environmental standards [29]. In this field of research, some experts have agreed that CSR and the efficient management of the supply chain generate significant quantitative and qualitative benefits for businesses [26,30,31]. These business sustainability practices seek shared benefits, such as the social and economic development of the regions, an increase in the quality of life, the professional development of employees, an increase in the satisfaction of clients and investors, and the strengthening of their image and business reputation [30,32,33]. These actions consequently allow businesses to achieve sustainability [32,34]. In this same direction, many countries from different regions have exposed within their public policies related to business development and growth, the adoption of good CSR practices and have suggested the existence of a close relationship with the supply chain as an efficient means to obtain significant results in companies of medium and small sizes [35,36,37].

Although there are mechanisms and guidelines from different local and international organizations to help in the adoption of CSR practices and sustainable actions, not all companies execute them, so some specialists in the field comment that this is a question of voluntary actions, but also of commitment and administrative and financial capacities [38]. These actions carry implicit social, organizational and economic risks. This is mainly due to the enormous complexity in its adoption and execution, ranging from the selection of suppliers, the choice and availability of materials, the quality of the inputs that are part of the value chain and the exit processes (delivery times) that directly affect the final customer [39,40]. For this reason, SMEs have been collecting good practices from large organizations to adapt them in their processes to align their stakeholders from an ethical, legal and responsible perspective [17,41,42]. In addition, SMEs not only focus on a group of consumers who buy their final product, but also become suppliers of large companies [43,44]. With this, the level of demand in their internal and external processes rises, which leads them to worry and take care of their image and reputation [45]. Therefore, in the last two decades, the study of the CSR and the SCM has become increasingly significant and recurrent in the management of companies regardless of the size of the organization [11,46]. This is largely because CS is an organizational practice that depends on several links within its management and operation. In SMEs, the association between CSR and SCM is synonymous with survival, development and growth in today’s hectic and competitive markets [47,48]. The benefits that can be achieved are crucial to continue on the path towards organizational and financial consolidation. Among those that stand out, the improvement of the employees–investors relationship and the company–suppliers–customers relationship can achieve a greater motivation of human resources, improve the regulatory processes of sustainability, improve the competitiveness, increase innovation actions, increase reputation and increase the level of profitability [17,49,50].

Therefore, SMEs should not be focused only on day to day, but also on future actions that will generate value. Undoubtedly, the excellent relationship and alignment between the buyer and the supplier with the policies and ethics of the organization have become increasingly determinant to achieve sustainability success. These actions related to the internal processes of CSR and the Supply Chain have become the most challenging strategic actions and tactics for smaller companies [51,52]. However, business sustainability based on CSR and supply chain management to strengthen competitiveness in SMEs remains poorly studied in the literature, and is especially lacking empirical studies [53,54,55]. These topics are often analyzed and addressed in a non-complementary and shallow way [56,57,58]. In addition, most of the research work focuses on large companies, especially multinationals [18,59,60,61].

The size and resource capacity (human and financial) of small businesses have become the main barriers to the adoption and successful deployment of CSR and supply chain management [62,63]. If we add to this a lack of strategic vision of the leader, prioritization of day-to-day activities, lack of business discipline, high costs, and excessive regulation for the implementation of certifications in quality processes, all together these have become a challenge for SMEs [39,64]. Often, these business practices are imitated and adopted by SMEs that are taking reference from large companies [46,65]. These actions are adopted for novelty and to gain more clients in the short term (and therefore to gain more money), and do not consider or prioritize a sustainability strategy [17,66]. Therefore, work in the present and in the future becomes important and determinant in the development and growth of the SME. This research aimed to analyze the relevance and effect of the Corporate Social Responsibility strategy and the management of the Supply Chain in the business results of SMEs. In addition, if we add that SMEs globally represent more than 95% of the total number of companies and that they generate around 50% of employment [67,68], the study of this type of organizations is even more interesting and relevant.

The purpose of this research was to examine the effects of corporate social responsibility, in terms of its social dimension, on the supply chain and innovation; analyze the effect that the supply chain has on the CSR, innovation, image, and reputation of a business; and examine the effect of innovation on image, reputation, and profitability in SMEs. The research questions contemplated were:

- The CSR and SCM determining strategies in the organizational and financial results of the SMEs?

- Does CSR, in its social dimension, have a positive influence on the SCM and innovation in SMEs?

- Does SCM have positive effects on innovation, image, and reputation for SMEs?

- Does the innovation that is generated in a SME positively influence the image, reputation, and profitability of the company?

Globally, in both developed and developing countries, these companies represent an average of 95% of all companies, generate close to 50% of jobs, and are the engine that drives the social and economic development of regions [51]. This research was based on a sample of 143 SMEs from the industrial, services, and commerce sector of the city of Guaymas Sonora, Mexico. For the analysis and validation of the results, we first used the statistical technique of ordinary least squares method (OLS) through the use of multiple linear regression, and then we used the technique with modeling of structural equations (SEM-Modeling of Structural Equations) based on the analysis of variance in order to validate the structured relationships in this investigation. For this purpose, we worked with Partial Least Squares (PLS) with support of SmartPLS software version 3.2.6 Professional, all with the aim of strengthening our statistical analysis.

This research contributes to the development of the theory on interest groups (stakeholders) and the theory on sustainability from two crucial perspectives. First, from the theoretical perspective of the interest groups, the study analyzed the organizational (employees, customers, suppliers, and society) and financial benefits (profitability of the investors) that are obtained from the social practices of CSR. Second, we analyzed the theory of sustainability, and its implications in the efficiency of the supply chain on innovation and business results (image, reputation, and profitability) of SMEs. This article is structured as follows: The first part presents the review of the literature, the empirical review, and the development of the hypotheses proposed in the theoretical model. Second section, the methodology, structure, definition, and characteristics of the sample are explained. In addition, the justification and measurement of the variables under study are outlined. Third section, the results, the main conclusions, and the discussion of the research are presented.

2. Literature Review

2.1. CSR, the Supply Chain, and Innovation in SMEs

From 1975 to the present, there have been numerous contributions to the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Initially, Sethi [69] introduced the ideas of the voluntary character of CSR and social obligations. Carroll [70] and Carroll [71] considered the economic, legal, and ethical aspects of CSR. Wokutch and Shepard [72] and Clarkson [73] considered safety as another component to be taken into account. Clarkson [73] introduced the philanthropic character of CSR. Shrivastava [74] included the environmental dimension in their discussion. Clair, et al. [75] advocated diversity. Jennings and Entin [76] included a discussion on human rights. Vives [77] also considered the ethics and religious values of CSR. Thus, successively, the concept of CSR has been shaped. As a general adopted definition, we can mention the Green book defining CSR as “the voluntary integration, by companies, of social and environmental concerns in their commercial operations and in their relationships with interested parties” [78] (pp. 7–8). More recently, the European Commission [79] has pointed out the responsibility of companies for their impact on society, and made explicit reference to the need for collaboration with stakeholders to “integrate social, environmental and ethical concerns, respect of human rights and the concerns of consumers in their business operations and their basic strategy” [79] (p. 7).

At first, it was large companies that addressed the implementation of socially responsible actions [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82], although, later, small- and medium-sized companies (SMEs) began to address this strategy [83,84,85]. The progress that SMEs have shown in this sense is important given that they constitute the true motor of economic growth and are generators of value in territories [38,86,87]. This allows us to affirm that “CSR can be applied by all types of companies, regardless of their characteristics, size, sector of activity or scope of action” [88] (p. 27). Therefore, today, CSR has a universal character in its application, and its application is relevant for all types of organizations [17].

There is an important aspect of CSR that is related to the guarantee of supplies, which implies the extension of CSR practices throughout the supply chain [27,32]. Socially responsible companies want their suppliers to also be socially responsible, thus promoting the implementation of CSR through the entire supply chain [23,89]. These companies are responsible for the welfare, productivity, and performance of all suppliers that contribute to their activities [24,64]. In this way, a transfer of socially responsible behaviors is carried out along the supply chain, which will undoubtedly influence the practices of other interest groups, and will provide a basic standard of social and environmental principles to be fulfilled [25,89,90].

The topic of supply chain management in a sustainability context has grown considerably in importance in recent years [27,32,91]. Related to the three typical dimensions of CSR (economic, social, and environmental), and following the perspective of the triple bottom line [17], green/environmental issues have dominated research until recently [12,27,92]. However, we should not forget the existence of the social and economic aspects. This perspective of chain management analyzes the different linkages in a production process, with consequences for relevant groups of interest (the suppliers and customers) [38].

It is common to link the study of CSR with the innovation undertaken by a company because CSR is, in itself, an innovation [85,93], and furthermore it is a mechanism that facilitates innovation [13,94,95]. CSR is an efficient business strategy that penetrates every innovative organization and becomes a key element in differentiating between competitors [85,96]. There is a synergy between CSR and innovation as both are strategic elements of competitiveness [97,98,99]. The literature indicates that companies that undertake CSR actions are more prone to innovation [17,100], while also being more likely to achieve better performances [96,101,102] and greater advantages and competitive success [103,104,105]. Rexhepi et al. [103] affirmed that innovation is stimulated by a global commitment to CSR.

Moreover, in linking innovation with the supply chain, the conventional notion some years ago was that innovation in the supply chain was only originated by the buyer [63,106]. Today, this perspective has been challenged and researchers consider that, because the production process is a multidisciplinary activity with the involvement of all areas and sections in an organization, innovation is generated in the different steps of the supply chain by interactions within buyer–seller relationships [39,105,107].

2.2. Reputation, Corporate Image, and Profitability in SMEs

In addition, CSR and reputation are also closely related variables [13,30]: CSR actions can determine an increase in a company’s reputation [86,108], which becomes a strategic factor capable of strengthening the competitive advantage of SMEs and is therefore of great value in organizations [56,109]. Reputation is considered as a collective perception associated with the identity of the company [45,110]. Reverte, et al. [111] and Graafland [30] pointed out that SMEs are incorporating CSR practices into their processes and thereby increasing their perceived value or reputation among stakeholders. On the other hand, Roberts and Dowling [112], McWilliams et al. [17], and Kim, Kim, and Qian [113] qualified reputation as an asset that generates profitability and sustained performance in the company.

In line with the previous arguments, the literature indicates that CSR can generate a competitive potential that results in the strengthening of the brand and improvement of the business image [30,114]. Today, image is a vital indicator for organizations because it significantly affects consumers’ attitudes, despite other marketing factors. Image is often externally viewed with cynicism [115,116], therefore some companies are reluctant to communicate their sustainability practices [21,117]. In this situation, firms must have credibility in their efforts to get sustainability initiative messages across to stakeholders [17,118]. This leads to a positive image for the company and could provide its legitimation. Currently, it is possible to affirm that the implementation of socially responsible initiatives, innovation, reputation, and a good corporate image are strategies capable of determining a certain amount of profitability for companies. Green innovation can ensure both environmental sustainability and economical profitability [93,119,120]. Moreover, some studies relate a good reputation with a company’s ability to obtain profitability [92,121,122]. Finally, a positive image could generate profitability for companies, as shown in numerous cases [21,122,123].

3. Development of the Hypothesis

3.1. CSR, the Supply Chain, and Innovation in SMEs

3.1.1. CSR and the Supply Chain

The growing concern regarding corporate social responsibility, especially in the environmental dimension, has promoted research on environmental risks [23,124] and influenced supply chains [22,125]. Moreover, pressure from consumers determines the development of processes in a supply chain. In this sense, it is obvious that the minimization of emissions or recycled products [31,126], waste reduction, environmental innovation, and cost-effective solutions should be prioritized [127,128]. Today, to be consistent, socially responsible organizations are expanding their corporate social responsibility practices to include managing their partners within the supply chain [23,47,48]. In this way, the CSR actions of every company determines and implies a corresponding degree of CSR in the supply chain for all its components. Hsueh [48] studied a new revenue sharing contract including corporate social responsibility for coordinating a supply chain, which determined the expected investment in CSR and formalized the contract between a manufacturer and a retailer. With this in mind, we posit the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

CSR positively affects the SME Supply Chain.

3.1.2. Supply Chain and CSR

From the perspective of the Stakeholder theory and the theory of sustainable development, supply chain management has become the subject of priority study by specialists in the subject of production management, business administration and recently for the area of strategic marketing [17,63,129,130]. It has also become a key factor that feeds and complements the results of CSR practices interdependently [131].

A significant number of companies globally focus their resources and capacities on the efficiency of the supply chain, because they know that these efforts lead to important results (customer satisfaction, increased sales and increased profitability) [130,132]. In the field of SMEs as well as in large companies, CS and CSR are intimately related variables and interdependent for achieving results [15,61,133]. Some studies have shown that SMEs the implement sustainability actions in the production of goods and services with ecological inputs, choose to work together with their responsible suppliers, execute strategies with a focus on green marketing and are based on processes of certification with environmental standards have a greater chance of success in their CSR activities [21,134,135,136]. Similarly, SMEs are more often ethical, responsible and committed to the environment and their customers [137,138,139]. This is mainly because they are more aware of the inputs and outputs of their value chain [52,140]. They are also certifying their internal processes (administrative and operational) such as the management of the supply chain to be more competitive and achieve a socially responsible company with its stakeholders [17,138,139,141]. Based on this, we formulate the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

CSR affects positively the SME Supply Chain.

3.1.3. CSR and Innovation

Some studies [10,100,103,139,142] state that the innovation processes that are undertaken by an organization are greatly influenced by the CSR actions implemented in the organization. The fact that SMEs implement CSR strategies means they are more innovative [63,143], with a direct relationship existing between these variables [144,145]. The literature indicates that there is a parallel increase between the adoption of socially responsible practices and the realization of innovations [146,147,148]. Based on this, we formulate the third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

CSR positively affects SME innovation practices.

3.1.4. Supply Chain and Innovation

The review of the literature by experts in the field has made clear that there is a relationship between the supply chain and increased innovation actions (by reducing costs, increasing quality, and improving customer service) which ensures process continuity in a context of global competitiveness [32,149,150]. At the same time, Soosay, et al. [151] and Panwar, et al. [152] discussed integration, cooperation, and collaboration in a supply chain strategy, which demands innovative strategies for synchronized performance. More precisely, Soosay et al. [151] stated that “collaboration in supply chains is important for innovation as partners realize the various benefits of innovation such as high quality, lower costs, more timely delivery, efficient operations and effective coordination of activities”. Corsten and Felde [153] and Leuschner, Rogers, and Charvet [154] agreed that the suppliers, who constitute an important step in the supply chain, could transfer ideas, perform R&D (Research and Development) of their own to absorb some of the R&D costs of the buying firm, and influence the firm’s performance. In this way, this supply chain link enhances innovation for the company. This opinion is also shared by Swink [155] and Johnson and Schaltegger [156]. From this, we introduce the fourth hypothesis of the study:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

SCM positively influences the level of innovation of the SME.

3.2. The Supply Chain, Reputation, and Business Image of the SME

3.2.1. Supply Chain and Reputation

A poor environmental performance at any stage of the supply chain process may damage the company’s reputation [157,158]. Therefore, the successful development of the supply chain determines the reputation of the business [114]. Hannes et al. [25] and Saeidi, Sayedeh Parastoo, et al. [159] argued that activities concerning the supply chain (such as reducing packaging and improving working conditions) could reduce costs while improving corporate reputation. Quarshie et al. [23] identified supplier selection procedures and supplier assessment capabilities as the main means for effectively managing suppliers’ sustainability, and thereby the related corporate reputations. Teuscher, Grüninger, and Ferdinand [160], Walker [45] and Saeidi, Sayedeh Parastoo, et al. [159], affirmed that proactivity in sustainable supply chain management may help manage reputational risk in a company. Multaharju, Lintukangas, Hallikas, and Kähkönen [51] and Kopnina and Blewitt [34] explored how companies can manage sustainability-related risks from the supply chain, an essential process for maintaining their reputation. They argued that suppliers’ non-sustainable actions and neglect of sustainability along the supply chain can cause reputational damage and broad financial losses for a focal company. However, even though in SMEs the effectiveness of supply chain management and interaction with CSR actions of the organization have become complex and difficult to adopt, there is a group of authors who have argued that this type of business is opting for efficient actions in the supply chain to reduce the risks in the processes that generate additional value for their customers [52,61,131]. This is causing greater confidence and certainty in the goods and services offered to the market. In addition, they are improving the perception of the brand and the level of reputation towards customers, suppliers and society is increasing [114,133]. Following this, we can establish the fifth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

SCM positively influences the improvement of the business reputation of the SME.

3.2.2. Supply Chain and Image

Wolf [161] and Luo et al. [66] studied how CSR behavior in the form of charitable donations receives a positive reaction from suppliers. The results support the strategic philanthropy view and apply stakeholder theory in the supply chain, observing that strategic CSR can support the positive opinions of suppliers. Furthermore, this practice could enhance a company’s corporate image. Jafari, Hejazi, and Rasti-Barzok [162] and Ngai et al. [163] explored the interaction between retailers and consumers, offering supply chain solutions, and they concluded that focusing on this boosts the brand image for retailers. Schaltegger and Wagner [7] and Kopnina and Blewitt [34] found that promoting and applying sustainable practices in the company gives multiple benefits, such as improving a company’s image and increasing profitability. These practices have become successful and key strategies for businesses. In addition, when both large and small businesses implement a strategy focused on sustainability (triple bottom line), and the supply chain is involved, the corporate image is significantly improved [17,164,165]. Considering this, we can posit the sixth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

SCM positively influences the improvement of the business image of the SME.

3.3. Innovation, Reputation, Image, and Profitability in SMEs

3.3.1. Innovation and Reputation

Innovation results (tangible or intangible) follow as an outcome of applied efforts and activities. Among the intangible results are the firm’s stability and reputation [3,166]. In recent years, some authors have pointed out the close relationship that innovation maintains with reputation [139,167]. Overstreet et al. [168] and Reverte et al. [111] examined the effects of innovativeness on various aspects of performance and reputation, and consequently suggested that the first strategy is positively related to the second one. In this sense, it is true that an improvement in the design of new products, production processes, customer service, etc. generates an improvement in business reputation. Based on this, the seventh hypothesis is stated:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Innovation increases business reputation in SMEs.

3.3.2. Innovation and Image

Several researchers have expressed that, when a company is perceived as innovative, this becomes a part of its image [3,105]. Martínez-Torres et al. [169] studied open innovation and customers’ activity in innovation communities, taking into account user preferences, comments, and votes. Their research found that managerial decisions are more focused on the features associated with brand image. Foroudi et al. [170] and Finoti et al. [171] expressed that consumer innovativeness has a positive impact on image. Wikhamn and Styhre [172] studied open innovation as a management concept of increased attention, which implies the existence of a difficult and challenging process. Moreover, this innovation generates employee engagement and improves the entrepreneurial image of the corporation. Based on this, the eighth hypothesis is stated:

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Innovation improves the business image of the SME.

3.3.3. Innovation and Profitability

Hall [173] and Flynn, Huo, and Zhao [174] referred to green supply chain management as an environmental innovation practice that companies can utilize to gain some profitability. Aguilera-Caracuel and Ortiz-de-Mandojana [175] and Dangelico [176] explained that the intensity of green innovation is positively related to firm profitability. Fliaster and Kolloch [177] researched green innovation and found that it is likely to be affected by the interactions between primary and secondary stakeholders and it is further expected to ensure profitability. In addition, there is evidence that innovation in the products and processes of companies generates social, organizational, and financial results [93,178,179]. Due to this, we can posit the ninth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Innovation increases the level of profitability in the SME.

3.3.4. Reputation and Profitability

The literature expresses in detail the relationship between reputation and profitability. In this sense, Sarbutts [56] explained how genuine intentions of engaging in CSR activities could generate outcomes, such as an enhanced reputation, that improve the profitability of the firms. Gray and Balmer [180] and Roberts and Dowling [112] showed that a good business reputation, which is valued and granted by customers, considerably increases the finances and the economy of the organization. Helm and Tolsdorf [181] stated that corporate reputation plays an important role in determining the impact of crises on firms, which can greatly affect small- and medium-sized enterprises, and related this factor to firm profitability. At the same time, Biong [182] and Saeidi et al. [159] studied the role of suppliers in competitive situations, and affirmed that suppliers with a strong positive reputation should achieve profitability for the company. Finally, green and/or sustainable strategies are beneficial as long as managers include them in their overall strategic programs that also promote firm value and reputation [7,21]. The authors also clarified the impact of green programs on profitability. Based on this, the tenth hypothesis is stated:

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

Business reputation increases the level of profitability in the SME.

3.3.5. Image and Profitability

Related to the relationship between image and profitability, Burin, Roberts-Lombard, and Klopper [183] studied the influence of internal marketing on service quality, and determined that the application of this approach enabled staffing agencies to improve brand image and, consequently, this could result in higher levels of profitability. Moreover, Rosenbaum and Wong [122] found that green equity plays a significant role in customers’ overall assessment of a hotel’s marketing programs, determining the effect on brand image. These authors also linked green marketing with an impact on profitability. Various research in the literature links market orientation with the improvement of image, as companies are able to focus on the best strategy [119,184]. As a result, the right market orientation could also correlate strongly with image and profitability [5,185]. Put simply, a strategy which improves image should improve profitability. Based on this, the eleventh hypothesis is stated:

Hypothesis 11 (H11).

Business image increases the level of profitability in the SME.

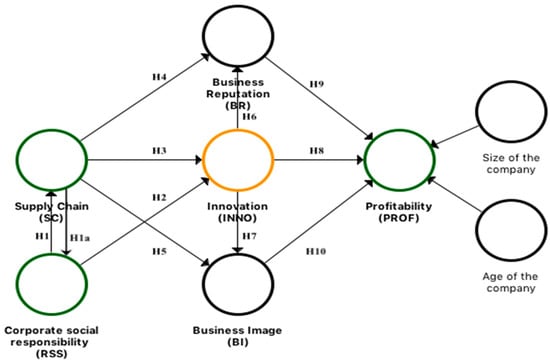

In Figure 1, we can observe the theoretical model proposed for this investigation. This model was developed based on the premises of stakeholder theory and sustainability.

Figure 1.

Theoretical operational model.

4. Methodology

The structure of the sample was based on the principles of stratified sampling for finite populations. The population is made up of the SMEs established in the city of Guaymas, of the State of Sonora in Mexico, which was segmented according to the activity criterion. The number of companies in each of the built strata was obtained from the information of the economic census provided by the National Statistical Directory of Economic Units (DENUE), of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography [186]. The sample is composed of SMEs that have from 10 to 185 workers. The sample size was determined to achieve a maximum margin of error for the estimation of a proportion (relative frequency of response in a specific item of a question) that was lower than 0.03 points, with a confidence level of 95%. The technique for collecting the information was through a personal interview (questionnaire) addressed to the leader of the SME. The fieldwork was carried out during September–November 2016. Finally, a sample of 143 companies was obtained; 7.0% belonged to the industrial sector, 37.0% to the service sector, and 56.0% to the commercial sector. The composition and characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. The companies that refused to participate in the project were replaced by similar companies (randomly chosen) of the same activity and geographical area. The non-response bias was analyzed [163,164]. The response effectiveness of the companies that responded in the first round was 90% of the sample, and they were compared with those that responded by substitution (10% of the sample). For all variables considered, no significant differences emerged between the two groups using the t and chi-square tests [187].

Table 1.

Total number of companies by activity.

4.1. Measurement of Variables

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Based on the literature and the main theories that are addressed in the studies that support this business activity, we took as reference the theory of interest groups, which encompasses the mutual benefits in social, economic, and environmental terms for the company (managers and employees), clients, and the community [65]. Therefore, we decided to focus the measurement of this variable on social activities for the achievement of organizational profitability. Based on the literature, we selected the social dimension as a fundamental part of CSR: Corporate Social Responsibility with a Social Approach (SSR) was measured, taking as reference the studies developed by Freeman et al. [16], McWilliams et al. [17], and Carroll [38]. The variable is composed of five questions within the questionnaire. The manager was asked to identify and rate the CSR social activities that the company had carried out in the last two years, using a five-point Likert scale with 1 = total disagreement and 5 = completely agree, this is recommended by Dawes [188], see Table 2.

Table 2.

Internal consistency and convergent validity by construct.

Supply Chain. To measure this variable, the analysis focused on the benefits that the SCM provides to the interest groups of the organizations. For this reason, we considered as a reference the theories on stakeholders and sustainability, as streams that contribute to the organizational (employees–clients) and financial (shareholders–interest groups) profitability of the company [14,16]. In the questionnaire, managers were asked to answer four questions about the importance of SCM results in CSR practices developed by the company in the last two years, using a five-point Likert scale with 1 = nothing important and 5 = very important. These questions were developed with reference to the studies of Hannes et al. [25] and Hervani, Helms, and Sarkis [189], see Table 3.

Table 3.

Internal consistency and convergent validity by construct.

Innovation. This variable was measured based on the models of OECD [190] and Teece [3]. These models consider innovation as the means to consolidate productivity and business competitiveness. To obtain timely information from the managers of the companies in the questionnaire, their responses were collected to indicate if their SME had introduced innovation actions during the previous two years (1 = yes, 0 = no), as well as the degree of importance of the innovative activity. For this, a scale a five-point Likert scale was used, with 1 = not important and 5 = very important. This variable measured the innovation in products and services developed by the SME with five structured questions (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Internal consistency and convergent validity by construct.

Business Image and Business Reputation. Frequently, when assessing these intangible results, company researchers have had difficulties in measuring these variables. The theory on stakeholders has been one of the main theoretical currents that explains the importance of CSR practices in the achievement of an improved reputation, image, and organizational profitability [16,191]. Based on the literature review we carried out, the Business Image variable was structured according to the studies of Gray and Balmer [180] and Chun [192]. This variable was measured through three questions formulated in a questionnaire addressed to the managers of the sampled SMEs. The Business Reputation variable was developed based on the studies of Dowling [193] and Walker [45]. This variable was measured through three questions formulated in a questionnaire addressed to the managers of the sampled SMEs. For both sets of questions, the managers expressed their perception of the image and reputation results obtained by the SME in the last two years. For this, we utilized a five-point Likert scale with 1 = total disagreement and 5 = completely agree (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Internal consistency and convergent validity by construct.

Profitability. This is one of the indicators that has been most analyzed by the literature, due to its value and importance for companies, and also due to the complexity of its measurement [194,195]. The measurement of this variable has been structured based on the theories on stakeholders and corporate sustainability. For the measurement of this variable, we considered as a reference financial profitability related to CSR and sustainability, for which we have considered the studies developed by Hubbard [196] and Abagail McWilliams et al. [17]. This variable was measured with five questions formulated in a questionnaire addressed to the managers of the sampled SMEs, who were asked to express their answers based on the performance results obtained by the company in the last two years. The questions were structured on a five-point Likert scale with 1 = poor performance and 5 = high performance (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Internal consistency and convergent validity by construct.

4.2. Control Variables

Size of the company. This variable was measured with the natural logarithm of the total number of employees in 2016. This variable is frequently used in empirical studies because it is an important parameter in the development and growth of a business [197] (Table 7).

Table 7.

Size and age of the company.

Age of the company. The age of the company determines the degree of consolidation and maturity within a market, as explained by evolutionary theory [1]. This variable was measured according to the start of business operations up until the current activities of the companies (Table 7).

4.3. Reliability and Validity

The reliability and validity of the instrument was checked using a structural equation model (SEM) to avoid measurement errors and multicollinearity [198]. Our study analyzed the variables of the theoretical model through SEM based on the variance, with this being the method that best adapts to our model and to the objectives of the research [198,199]. The use of the PLS methodology implies a two-phase approach [199,200] including the measurement model and the structural model. The measurements are based on a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), used to rule out the indicators that have a low correlation with the rest of the scale. In addition, internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity were all analyzed [201,202].

5. Results

5.1. Linear Regression Analysis

To show previous results of the structured relationships, we carried out the analysis with the use of the ordinal least squares (OLS) method through multiple linear regressions. These analyses were carried out to show the bidirectional effect between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the Supply Chain Management (SCM). Currently, with PLS and/or PLSconsistent, it is impossible to perform this type of analysis simultaneously [202,203]; therefore, we developed the following models:

- Model 1. CSRi = β0 + β1 x SCMi + β2 x Size of the company + β3 x Age of the company + £

- Model 2. SCMi = β0 + β1 x CSRi + β2 x Size of the company + β3 x Age of the company + £

The results of the H1 suggest that the CSR has a positive and significant effect on the SCM according to the beta values of 0.329***. In addition, the findings of H2 informed us that CS influences significantly and positively the activities of CSR that are developed in SMEs, as shown by the beta value of 0.343***. This confirms that these two business practices have become decisive actions and activities in the development and growth of companies and more for SMEs. In the Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 (in Appendix A), all the results of the hypotheses structured in the investigation can be visualized with the use of the linear regression technique and all of which have been confirmed. In all the models developed, the variables of control of the size and age of the company have been introduced. We have only found that the size of the company has a significant and positive influence on innovation and a significant negative effect on the business image, according to the values of beta 0.175**(95% significant) and −0.139*(90% significant). However, the most important and determining findings in this research are those that have been made with the model of structural equations, which is mainly because it is a second generation technique, with greater power in the multivariate analysis of the area of science social, marketing and administrative sciences [199,200]. This technique is a combination of linear regression (econometric perspective), which focuses on prediction, and factor analysis (psychometric perspective), which models concepts as latent (unobserved) variables that are indirectly inferred from multiple observed measures (indicators or manifest variables) [199,204].

5.2. Measurement Model

To evaluate the measurement model with reflective-type variables, we analyzed the composite reliability of each item, the internal consistency of the scale, and the convergent validity. To measure the relationship and individual reliability of each item, a standardized load of the major factor is recommended, which is set to 0.707 [205,206]. The values of the research were within the range of 0.711–0.910, and all were above 0.707. The composite reliability shows the values fell in the range of 0.847–0.910; the indicator must be above 0.80 for basic research, as proposed by Nunnally [207] and Wetzels, Odekerken-Schröder, and van Oppen [208]. Cronbach’s alpha is considered satisfactory if it is over 0.70 [198]. Our results showed values between 0.759 and 0.868, which indicates high reliability of the construct. The average variance extracted (AVE) indicates the average amount of the variance explained by the indicators of the construct. Our AVE values ranged from 0.581–0.748; these results must be above 0.500, as indicated Hair [199]. Finally, the discriminant validity of the constructions in the model was verified by analyzing the square root of the AVE. The (diagonal) results of the vertical and horizontal AVE are below the correlation between the constructs [206]. This shows that there is no anomaly (see Table 8). Our results suggest adequate validity (convergent and discriminant) and reliability of the model.

Table 8.

Discriminant validity of the theoretical model.

5.3. Structural Model

The statistical technique of structural equations based on variance was used to validate the hypotheses of this research through the SmartPLS version 3.2.6 Professional software [209]. The use of this technique with the support of this software is appropriate in exploratory and confirmatory research [199,210]. In Table 5, the β coefficient results, the degree of significance (p-value), and the importance of the distribution of the values using the Student’s t test are shown. To test the hypothesis, the bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples was used, as recommended Chin and Dibbern [210].

Table 9 shows the results of the estimation of the structural equations made with PLS. We found empirical support for the hypotheses structured in the model (H1, H2, H3, H5, H6, H7, H8 and H10), except for hypotheses H4 and H9. The results of the hypotheses are as follows: H1 and H2 have positive and significant effects at 0.001 and 0.05 respectively. H1 shows a strong positive and significant relationship between SSR and SCM in SMEs, according to the beta value of 0.445***. H2 indicates that SSR exerts a positive and significant influence on innovation activities in SMEs, according to the beta value of 0.214**. With respect to the SCM variable, we found that H3 and H5 exert a positive and significant effect at 0.001. These results show that SCM has a strong relationship with the innovation and business image of the SME, according to the values of β = 0.445*** and β= 0.379***, respectively. Similarly, the results show a strong relationship and significant effects of 99% for innovation on the reputation, image, and profitability of the SME (H6, H7, and H8), according to the values of β = 0.378***, β = 0.350*** and β = 0.415***, respectively. In addition, hypothesis H10 has positive and significant effects at 0.05, indicating that image has a strong influence on the profitability of SMEs, according to the value of β = 0.299**. However, hypotheses H4 and H9, with values of β = 0.178 and β = 0.133, show that SCM does not have a significant effect on reputation, and that profitability is not affected by reputation. The variables of size and age of the company have also been incorporated into the model. The results indicate that these two variables do not show a significant influence on profitability in SMEs, according to the values of β = −0.029 and β = 0.001, respectively.

Table 9.

Hypothesis test results.

Evaluation of the adjustment of the theoretical model with the SEM techniques that are based on the covariance through PLS is not yet fully developed, and it is only possible to estimate these measurements based on: (1) the value of the path coefficients; (2) the analysis of R2; and (3) the values of F2, which are significant individual measures to explain the predictive capacity of the structural model [210]. Trajectory coefficients around 0.2 are considered economically significant [209]. Our most important coefficients of the model range from 0.299** to 0.445***. For the analysis of the variance and the prediction quality of the model through R2, the following measurement scales are taken: The values of 0.1, 0.25 and 0.36 are small, medium and large effects [208]. The results of the model through R2 show an important explanatory power of the dependent variables in the model, as shown in Table 10. The value of F2 shows the size of the effect introduced in the model. The values of F2 were 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35, indicating a weak, medium, or large effect [203]. The analysis of F2 shows the results of the key relationships of the model with values of 0.107, 0.146, 0.154, 0.207, 0.363 and 0.345. These results show that the proposed model has adequate structural properties and a good explanatory level. The statistical test Q2 (cross-validated redundancy index) was used to evaluate and test the predictive relevance of endogenous constructs in a structured model, with variables of reflective type [198]. The values ranged 0.113–0.239. Values greater than 0 show a remarkable predictive quality [198]. This demonstrates the existence of a remarkable explanatory quality of the model. To explain more accurately the predictive effect of our model, we added a goodness-of-fit test performed by PLS. When the standardized value of the residual quadratic mean (SRMR) is in the range <0.08–0.1, there is an acceptable fit [211]. Our result of 0.080 confirms that the proposed model has an acceptable predictive quality and demonstrates that the empirical results are aligned with the theory (see Table 10).

Table 10.

Predictive quality and fit of the model.

6. Discussion

Based on the theories known as integrators (stakeholders and sustainability), we carry out the discussion of our research results from a social, environmental, and economic perspective. From the perspective of the stakeholder theory, it has been argued and evidenced that the social practices developed by companies are the means by which to achieve an improved image, reputation, and profitability for organizations [16,195]. In addition, if companies seek sustainability, taking care of the elements of the triple bottom line and transferring this to their processes such as supply chain management results in the generation of innovative products, more environmentally friendly (ecological) products, and improved customer and shareholder satisfaction [17,34]. Therefore, these strategies and new business models strengthen companies to achieve global competitiveness, permanent innovation, quicker adaptation to market changes, and sustained returns [16,32]. However, it should be mentioned that SMEs in developing countries have more limitations and barriers to adopt and deploy actions focused on responsible management, sustainability and efficiency of their processes. Therefore, these business practices become a challenge and a determining goal in their path towards reputation and global competitiveness [46,82,212].

The results of our analyses inform us that CSR (specifically, the social dimension) is an excellent driver in the generation of greater innovation activities in a company [65]. These findings are similar to those found in the literature and previous empirical studies [38]. We also found that SSR influences the management of the supply chain. In highly competitive, global, and demanding markets, companies have to voluntarily take on social actions to improve internal processes and raise the quality of the product and the satisfaction of consumers [25,63]. These are results that align with the theories of sustainability and strategic management of the supply chain [140,213]. Similarly, the findings inform us that SCM as a sustainability strategy is an effective agent in achieving greater innovation, and contributes strongly to achieving a better corporate image [214]. By taking care of internal processes through the correct management of the SCM (selection of suppliers and inputs), companies can manage to improve the quality of their products, control the inventory, control costs, and above all improve the satisfaction of their clients [25,141]. This leads companies to be more innovative and dynamic in globalized markets [3,32]. In addition, the study has shown that these two variables (CSR/SCM-SCM/CSR) have a bidirectional link, i.e., they are closely interconnected [17,130,215]. Our analysis through the linear regression technique has shown that the supply chain has a significant and positive influence on CSR activities in the SME. Thus, it is corroborated that this type of companies is taking risks and complying with its responsibilities to satisfy their stakeholders, all of which are achieved by focusing on the improvement of their internal processes and sustainability practices [29,41,212]. Another important finding in this study is related to the influence of innovation activities in an SME on image, reputation, and profitability. These results are aligned with the theory of sustainability, and also recently with the theory of dynamic capabilities [3,34]. These theories suggest that the companies that incorporate into their processes new business models, with a focus on sustainability, manage to improve their processes, design new products, and thereby obtain invaluable organizational results [93,216]. These results are reflected in the improvement of the perception of stakeholders of the transformation into a more innovative company—an admired, dynamic and respected company. It becomes clear that this leads to organizational and financial sustainability [17,118]. In addition, our results and the literature report that companies with a good image, as perceived by stakeholders, contribute strongly to financial profitability for shareholders [38,65]. On the other hand, we did not find significant empirical evidence for the relationship between SCM and reputation. In addition, reputation does not influence the profitability results of the SME. The literature shows that this activity and/or business result (output) is a key element in the organizational, economic and financial results [21,30]. However, our results differed from this. This may be due to the priority of other activities for SMEs, which may direct their resources and capabilities towards responding to market competition, prioritizing the short-term benefits of the shareholder, and trying to meet the daily demands of customers [46,194].

7. Conclusions

This research analyzed the social practices of CSR with an approach directed towards the efficient management of the supply chain under the context of stakeholder and sustainability theories. First, to answer the initial question of the research, the study corroborated that CSR and CS are closely related and that the efficient execution of these business practices generates multiple organizational and financial benefits for SMEs. The results indicate that: (1) the social practices of CSR practiced in SMEs are focused on improving innovation and strengthening the management of the supply chain; (2) in addition to influencing SCM management in SMEs, these factors are strongly influencing innovation and achieving a better corporate image; and (3) the actions in terms of innovation in the SME manage to satisfy the interested parties and are achieving the desired improvements in reputation, image, and financial profitability. The results of the research have generated important implications that can help strengthen the business management of SMEs. First, managers must continue to strengthen their sustainability practices, which can be achieved through the implementation of new business models and the adoption of strategic trends focused on green businesses (green marketing) [8,217]. Secondly, the owners and managers of SMEs should focus their resources and capacities on the implementation of ISO standards to achieve certification of internal processes to become sustainable businesses (ISO 14001), and should adopt guidelines aimed at further developing CSR practices (ISO 26001) [29,218]. In the short term, for SME managers to compete in economies of scale, it is important that they adopt current economic models such as the circular economy and the bioeconomy to achieve sustainability through strategic alliances between stakeholders, such as government, society, and customers [118,219].

This study had some limitations, which lead to some possibilities for the development of future lines of research. The first limitation of the work is the use of a single source of information, as the data were collected from the subjective perceptions of the owners and/or managers of SMEs. Secondly, the sample was only focused on companies established in a specific geographical area, and could in the future be extended to other geographical points across the country. Finally, the measurement scales used to measure CSR focused exclusively on the social sphere, and worked with variables of a reflective type. In the future, to address this limitation, it would be convenient to perfect and incorporate a greater number of constructs for the analysis of CSR and sustainability in SMEs. Given the relevance of this business topic and the current situation of fragmented economies, this type of study is expected to be repeated in the future, involving these variables along with ISO 14001, 26001, green marketing, and open innovation. Furthermore, it is favorable to continue evaluating indicators within SMEs that influence development, growth, and competitiveness.

Author Contributions

L.E.V.-J. Developed the operational model of the research; developed the objective and the approach of the hypotheses; supervised the work of gathering information to the managers through a questionnaire; contributed to the development of the literature and the analysis of the results; and wrote the Conclusions. D.G.-V. Contributed to the development of the literature review and the justification of the hypotheses and supported writing part of the Conclusions. E.A.R.-E. Contributed to the research; wrote part of the literature; and supported writing the justification of the variables of the theoretical model and in the final revision of the structure of the document. All authors contributed to the development of this work. In addition, the authors have read and approved the final version of this document.

Funding

This project received funding for its development and publication by the Program for Strengthening Educational Quality (PFCE, 2017) of the Secretariat of Public Education of Mexico.

Acknowledgments

We thank the support in the elaboration of this research to the professors of the research group of Management and Business Development of ITSON in Mexico and to the professors of the University of Extremadura in Spain. In addition, our recognition to the managers of the companies participating in this investigation for their availability and their valuable support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Linear regression (SSR-SCM-INNO/SCM-SSR).

Table A1.

Linear regression (SSR-SCM-INNO/SCM-SSR).

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCM Coef. (Value t) | INNO Coef. (Value t) | SSR Coef. (Value t) | ||

| SSR | 0.329 *** (4.187) | 0.397 *** (5.100) | SCM | 0.343 *** (4.187) |

| Age of company | −0.132 (−1.649) | 0.017 (0.209) | Age of company | 0.104 (1.245) |

| Size of company | −0.207(−2.578) | 0.125 (1.564) | Size of company | −0.008 (−0.095) |

| Higher VIF | 1.05 | 1.05 | Higher VIF | 1.08 |

| F Value | 8.469 *** | 9.209 *** | F Value | 6.155 ** |

| Tight R2 | 0.137 | 0.149 | Tight R2 | 0.099 |

Source: Own elaboration. SSR, Corporate Social Responsibility; SCM, Supply Chain; INNO, Innovation. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table A2.

Linear regression (SCM-INNO-BR-BI).

Table A2.

Linear regression (SCM-INNO-BR-BI).

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| INNO Coef. (Value t) | BR Coef. (Value t) | BI Coef. (Value t) | |

| SCM | 0.490 *** (6.439) | 0.325 *** (3.940) | 0.535 *** (7.243) |

| Age of company | 0.127 (1.635) | 0.016 (0.195) | 0.016 (0.211) |

| Size of company | 0.175 ** (2.279) | 0.010 (0.907) | −0.007 (−0.095) |

| Higher VIF | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 |

| F Value | 14.414 *** | 5.327 *** | 18.271 ** |

| Tight R2 | 0.222 | 0.084 | 0.269 |

Source: Own elaboration. SCM, Supply Chain; INNO, Innovation; BI, Business Image; BR, Business Reputation. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table A3.

Linear regression (INNO-BR-BI-PROF).

Table A3.

Linear regression (INNO-BR-BI-PROF).

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BR Coef. (Value t) | BI Coef. (Value t) | PROF Coef. (Value t) | |

| INNO | 0.245 *** (2.958) | 0.506 *** (6.905) | 0.411 *** (5.307) |

| Age of company | −0.055 (−0.647) | −0.104 (−1.392) | −0.115 (−1.451) |

| Size of company | −0.064 (−0.760) | −0.139 * (−1.858) | −0.103 (−1.291) |

| Higher VIF | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| F Value | 3.063 ** | 16.658 *** | 10.026 *** |

| Tight R2 | 0.042 | 0.250 | 0.161 |

Source: Own elaboration. INNO, Innovation; BI, Business Image; BR, Business Reputation; PROF, Profitability. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table A4.

Linear regression (BR-PROF/BI-PROF).

Table A4.

Linear regression (BR-PROF/BI-PROF).

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Dependent Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| PROF Coef. (Value t) | PROF Coef. (Value t) | ||

| BR | 0.382 *** (5.100) | BI | 0.435 *** (5.670) |

| Age of company | −0.084 (−0.106) | Age of company | −0.063 (−0.809) |

| Size of company | −0.046 (−0.572) | Size of company | −0.023 (−0.288) |

| Higher VIF | 1.02 | Higher VIF | 1.02 |

| F Value | 8.535 *** | F Value | 11.371 *** |

| Tight R2 | 0.138 | Tight R2 | 0.181 |

Source: Own elaboration. BI, Business Image; BR, Business Reputation; PROF, Profitability *** p < 0.001.

References

- Nelson, R.R. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.A. A theory of international new ventures: A decade of research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2005, 36, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, G.M. Karl Polanyi on economy and society: A critical analysis of core concepts. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2017, 75, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Heppelmann, J.E. How Smart, Connected Products Are Transforming Companies. Available online: www.hbr.org (accessed on 26 June 2018).

- Morgan, R.E.; Berthon, P. Market orientation, generative learning, innovation strategy and business performance inter-relationships in bioscience firms. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 1329–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Managing the Business Case for Sustainability: The Integration of Social, Environmental and Economic Performance; Taylor & Francis: Didcot, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva, T.; Ritala, P. What are the sources of capability dynamism? Reconceptualizing dynamic capabilities from the perspective of organizational change. Balt. J. Manag. 2016, 11, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J.; Bruder, R.; Buckle, P.; Carayon, P.; Falzon, P.; Marras, W.S.; Wilson, J.R.; van der Doelen, B. A strategy for human factors/ergonomics: Developing the discipline and profession. Ergonomics 2012, 55, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer and Satisfaction, and Market Value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.S.; Wright, P.M. Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahi, P.; Searcy, C. A comparative literature analysis of definitions for green and sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Theory of The Firm Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-D.P. A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: Its evolutionary path and the road ahead. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B.L.; de Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, A.; Parhankangas, A.; Coupet, J.; Welch, E.; Barnum, D.T. Strategic Decision Making for the Triple Bottom Line. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2016, 25, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Creating sustainable value. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. In Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance; Zimmerli, W.C., Holzinger, M., Richter, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Engert, S.; Rauter, R.; Baumgartner, R.J. Exploring the integration of corporate sustainability into strategic management: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2833–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, W.; Ellram, L.; Kirchoff, J. Corporate Social Responsibility Reports: A Thematic Analysis Related to Supply Chain Management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 46, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarshie, A.M.; Salmi, A.; Leuschner, R. Sustainability and corporate social responsibility in supply chains: The state of research in supply chain management and business ethics journals. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2016, 22, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Purchasing, Supply Chain Management and Sustained Competitive Advantage: The Relevance of Resource-based Theory. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 48, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannes, H.; Christian, B.; Christoph, B.; Michael, H. Sustainability-Related Supply Chain Risks: Conceptualization and Management. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2014, 23, 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, U.; Habel, J.; Stierl, M. Exerting Pressure or Leveraging Power? The Extended Chain of Corporate Social Responsibility Enforcement in Business-to-Business Supply Chains. J. Public Policy Mark. 2017, 36, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, P.; Zhaohui, W.U. Building a more complete Theory of Sustainable Supply Chain Management using Case Studies of 10 Exemplars. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 45, 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrón-Vílchez, V. Does symbolism benefit environmental and business performance in the adoption of ISO 14001? J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graafland, J. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Put Reputation at Risk by Inviting Activist Targeting? An Empirical Test among European SMEs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R. Standardizing social responsibility new perspectives on guidance documents and management system standards for sustainable development. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2012, 59, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, A.; Pati, R.K.; Padhi, S.S.; Govindan, K. Evolution of sustainability in supply chain management: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H.; Blewitt, J. Sustainable Business; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.; Leka, S.; Zwetsloot, G. Managing Health, Safety and Well-Being: Ethics, Responsibility and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Touboulic, A.; Walker, H. Theories in sustainable supply chain management: A structured literature review. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 16–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske-Janssen, P.; Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. 20 years of performance measurement in sustainable supply chain management—What has been achieved? Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 664–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiyazhagan, K.; Govindan, K.; NoorulHaq, A.; Geng, Y. An ISM approach for the barrier analysis in implementing green supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golicic, S.L.; Smith, C.D. A Meta-Analysis of Environmentally Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices and Firm Performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 49, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, S.; Roca, M.; Colomé, R. SMEs as ‘transmitters’ of CSR requirements in the supply chain. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2013, 18, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickert, C. ‘Political’ Corporate Social Responsibility in Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 792–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B. Lean principles, practices, and impacts: A study on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Ann. Oper. Res. 2016, 241, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Perrini, F. Investigating Stakeholder Theory and Social Capital: CSR in Large Firms and SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K. A Systematic Review of the Corporate Reputation Literature: Definition, Measurement, and Theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2010, 12, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudal, T. Drivers and barriers of CSR and the size and internationalization of firms. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, C.-F. A bilevel programming model for corporate social responsibility collaboration in sustainable supply chain management. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2015, 73, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, C.-F. Improving corporate social responsibility in a supply chain through a new revenue sharing contract. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 151, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; de Sousa-Filho, J.M. The impact of sustainability governance, country stakeholder orientation, and country risk on environmental, social, and governance performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastrana, N.; Sriramesh, K. Corporate Social Responsibility: Perceptions and practices among SMEs in Colombia. Public Relat. Rev. 2014, 40, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multaharju, S.; Lintukangas, K.; Hallikas, J.; Kähkönen, A.-K. Sustainability-related risk management in buying logistics services. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017, 28, 1351–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, J.K.; Hoejmose, S.U.; Overland, V. Driving green supply chain management performance through supplier selection and value internalisation. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Olugu, E.U.; Musa, S.N.; Mahat, A.B. Fuzzy-based sustainability evaluation method for manufacturing SMEs using balanced scorecard framework. J. Intell. Manuf. 2018, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable development and entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masurel, E. Why SMEs invest in environmental measures: Sustainability evidence from small and medium-sized printing firms. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2007, 16, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbutts, N. Can SMEs ‘do’ CSR? A practitioner’s view of the ways small- and medium-sized enterprises are able to manage reputation through corporate social responsibility. J. Commun. Manag. 2003, 7, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageron, B.; Spalanzani, A. Sustainable supply management: An empirical study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate Hypocrisy: Overcoming the Threat of Inconsistent Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. ‘Implicit’ and ‘Explicit’ CSR: A Conceptual Framework for a Comparative Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann-Pauly, D.; Wickert, C.; Spence, L.J.; Scherer, A.G. Organizing Corporate Social Responsibility in Small and Large Firms: Size Matters. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 115, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Business Ethics: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Small Business Champions for Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, M.S.; Tang, C.S. Corporate social sustainability in supply chains: A thematic analysis of the literature. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 882–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti, F.; Pontrandolfo, P.; Scozzi, B. Investigating corporate social responsibility in supply chains: A SME perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1579–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Wang, H.; Raithel, S.; Zheng, Q. Corporate social performance, analyst stock recommendations, and firm future returns. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. The World Bank Annual Report 2017; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Small, Medium, Strong. Trends in SME Performance and Business Conditions; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, S.P. Dimensions of Corporate Social Performance: An Analytical Framework. Calif. Manage. Rev. 1975, 17, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibiiity: Toward the Morai Management of Organizational Stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wokutch, R.E.; Shepard, J.M. The Maturing of the Japanese Economy: Corporate Social Responsibility Implications. Bus. Ethics Q. 1999, 9, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.E. A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P. Industrial/environmental crises and corporate social responsibility. J. Socio-Econ. 1995, 24, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, J.; Crary, M.; McDaniels, M.; Spelman, D.; Buote, J. Una Investigación Cooperativa en la Enseñanza y Tomar un Curso Sobre Gestión de la Diversidad. Investig. Corp. 1997. Available online: https://detective-prive-neuilly.fr/ (accessed on 26 June 2018).

- Jennings, M.; Entine, J. Negocios con alma: Un reexamen de lo que cuenta en la ética empresarial. HeinOnline 1999, 1, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Vives, A. Responsabilidad Social y Ambiental en Pequeñas y Medianas Empresas en América Latina; Greenleaf Publishing: Didcot, UK, 2006; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- European Comission. Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility; Green Book; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]