Abstract

We develop and apply a systematic literature review methodology to identify and characterize the ways in which the peer-reviewed literature depicts how climate change adaptation is occurring in Australia. We reviewed the peer-reviewed, English-language literature between January 2005 and January 2018 for examples of documented human adaptation initiatives in Australia. Our results challenge previous assumptions that adaptation actions are not happening in Australia and describes adaptation processes that are underway. For the most part, actions can be described as preliminary or groundwork, with a particular focus on documenting stakeholder perspectives on climate change and attitudes towards adaptation, and modelling or scenario planning in the coastal zone, agriculture, and health sectors. Where concrete adaptations are reported, they are usually in the agricultural sector and are most common in the Murray–Darling Basin, Australia’s food basket. The findings of the review advance our understanding of adaptation to climate change as a process and the need to consider different stages in the process when tracking adaptation.

1. Introduction

In Australia, documented climatic changes include rising temperatures, changing rainfall patterns, more extreme events (heat waves, bushfires, flooding, storms), increasing ocean temperature, and sea-level rise [1]. These changes, together with other anthropogenic drivers of environmental change (i.e., resource development, population increase), have already negatively affected terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems such as the Great Barrier Reef [2]; compromised agricultural production in some regions [3]; and have negatively affected human health [4]. Climate models project that these changes will continue, and likely accelerate into the future, with further effects on ecosystems and people [5]. Notwithstanding the importance of mitigation initiatives, adaptation is desperately needed if the negative impacts are to be moderated and opportunities captured [6].

In light of the urgency for adaptation, efforts to track adaptation initiatives have increased in recent years [7]. Some researchers have mapped the current state of adaptation in particular places and sectors to better understand adaptation processes and identify knowledge and resource needs. Here, adaptation actions have been generally grouped as either ‘groundwork’ or ‘concrete’ actions. Groundwork actions refer to “preliminary steps taken toward adaptation that inform and prepare countries to implement adaptations, but do not themselves constitute changes in policy, programs, or delivery of services” [8] (p. 1155). Concrete actions refer to “tangible steps taken to alter institutions, policies, programs, built environments, or mandates in response to experienced or predicted risks of climate change” [8] (p. 1155). For example, researchers have completed systematic reviews of the peer-reviewed literature to characterize concrete adaptation actions in the Canadian Arctic [9], among developed nations [10], and globally [11]. To date, reviews that have focused exclusively on concrete actions have reported few adaptation actions underway in Australia, and labelled Australia a laggard in climate change adaptation [10]. Here, we expand the scope of existing reviews to include both groundwork and concrete adaptation actions to characterise how Australia is adapting to climate change. The findings of this review are intended to provide a proxy of the state of adaptation in Australia from the perspective of the peer-reviewed literature.

2. Climate Change Adaptation in Australia

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a long history of coping with and adapting to changing environmental conditions including recent climate change [12,13]. Formal adaptation to climate change among non-Indigenous people in Australia, however, is relatively new. Adaptation to climate change was first recognized as a priority by the Australian government in 2004 with the announcement of a budget for a National Climate Change Adaptation Programme. The programme aimed to help prepare industries, communities, and state and local governments for the impacts of climate change [14]. Later in 2006, the Council of Australian Governments requested the development of a National Adaptation Framework as part of its Plan of Collaborative Action on Climate Change. The framework described a collaboration agenda for governments at various levels to address climate change impacts and generate information for effective adaptation [15]. In 2007, the Climate Adaptation Flagship was established under the Commonwealth Scientific Industry and Research Organization (CSIRO), to provide practical and effective adaptation options for policy makers, industries and communities [16]. As a part of the National Climate Change Adaptation Programme, the Australian Government established the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility (NCCARF) in 2008. The NCCARF brings together Australian researchers to address priority questions about climate change impacts and adaptation, and to communicate this knowledge to decision-makers in order to facilitate more effective adaptation at multiple scales [17]. The NCCARF originally received five years of funding worth $50 million (AUS) for Phase 1 (2008–2013), $30 million of which funded approximately 100 research projects and 8 networks that focused on building capacity [18]. Phase 2 (2014–2017) received $8.8 million (AUS) and focused primarily on capacity development and support, particularly by ensuring that research materials from Phase 1 were synthesized and accessible to decision-makers at the local level [18]. Adaptation to climate change is also the focus of state, territory, and local governments, mostly within their environmental agendas and as part of their own climate change strategies [19]. In Australia, the responsibility of adaptation planning is largely placed on municipal councils, reflecting the country’s diverse geography and broad scope of potential climate change impacts and adaptations [20]. With that said, effective climate change adaptation requires a multi-governance approach in which each level of government has a shared responsibility [21].

Australia is a party to the United Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which came into force on 21 March 1994. Since then Australia has published seven national communications on climate change, the most recent in 2017, which cover a range of adaptation activities and policies in Australia.

3. Methods

A systematic literature review was used to examine the ways in which the peer-reviewed literature depicts how climate change adaptation is occurring in Australia following methods described by Lesnikowski et al. (2013) [8] for differentiating actions as groundwork and concrete. Systematic literature reviews respond to specific questions by using explicit and reproducible methods for selection and analysis. While this review approach is common in the health sciences, it has also gained traction in the climate change field as a way to characterize and keep track of the burgeoning body of literature [22].

3.1. Document Selection

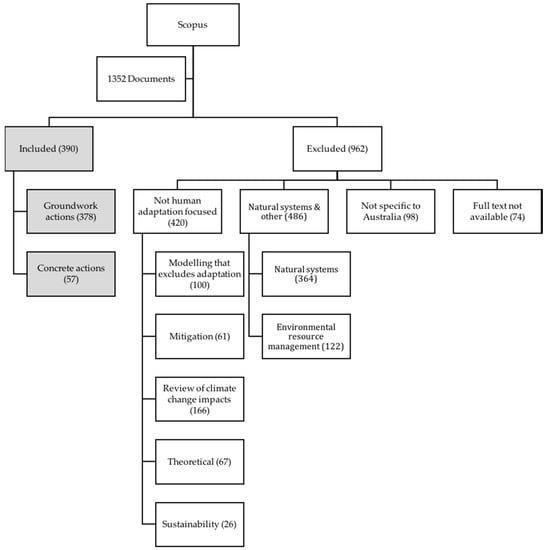

A document search was performed in the Scopus database using the terms “Adapt*” AND “Climat* Change” AND “Australia*” in the title, keywords, and abstract fields. Scopus was selected due to its availability as one of the most current, powerful, comprehensive and widely used search engines for peer-reviewed literature [23]. The search focused on peer-reviewed literature reporting or discussing intentional human adaptation initiatives in Australia published between January 2005 and January 2018, reflecting the goal of characterizing how the peer-reviewed literature depicts how climate change adaptation is occurring in Australia. The search retrieved 1352 articles (Figure 1). Articles that discuss both groundwork and concrete adaptation actions are included in both categories and excluded documents can be grouped in multiple categories in Figure 1. An inclusion/exclusion process was applied to the retrieved literature (Table 1). Every article was examined and the abstract was read to ensure that the article dealt with intentional human adaptation to climate change in Australia, and eliminate duplicate records, articles that were not peer-reviewed, in languages other than English, and those to which full text was not available.

Figure 1.

Document selection summary.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

3.2. Document Review

After applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 390 articles were retained for full review (see Supplementary Materials). A questionnaire was applied to each article and focused on: (i) general characteristics of the articles (year of publication, authorship, and type of adaptation initiatives); (ii) nature of the adaptation initiative (groundwork or concrete actions, stimulus motivating the adaptation initiative, who or what is adapting, and the details of the adaptation initiatives). Categories of adaptation actions were identified using grounded theory, in which repeated ideas, concepts and themes became apparent and were tagged with codes, which were extracted from the data (using NVivo 11.4.0 qualitative data analysis software). These codes were then grouped into concepts, and then into categories. Groundwork actions were grouped into eight categories: (1) impact, risk, vulnerability, and adaptive capacity assessments; (2) research on adaptation options; (3) conceptual tools; (4) stakeholder perspectives about climate change and attitudes towards adaptation; (5) recommendations for adaptation actions; (6) scenario planning or modelling with an adaptation focus; (7) economic analysis focused on adaptation; and (8) policy and framework reviews that suggest adaptation. Several of the reviewed articles discussed multiple adaptation actions, both concrete and groundwork, and were thus grouped in more than one category.

3.3. Search Limitations

We recognize the limitations of the search process and biases in document selection, review, and coding. Due to the parameters of the search engine and criteria, some relevant literature is likely to have been excluded from this review (e.g., articles to which full-text was not available). Although measures were taken to be objective (e.g., the use of NVivo software to identify trends in the literature), some bias is inherent in the review process (e.g., selection of groundwork themes). That said we believe that we have captured a large portion of available peer-reviewed literature that documents human adaptation initiatives in Australia, including groundwork and concrete actions.

4. Results

4.1. Reporting on Adaptation Is Increasing

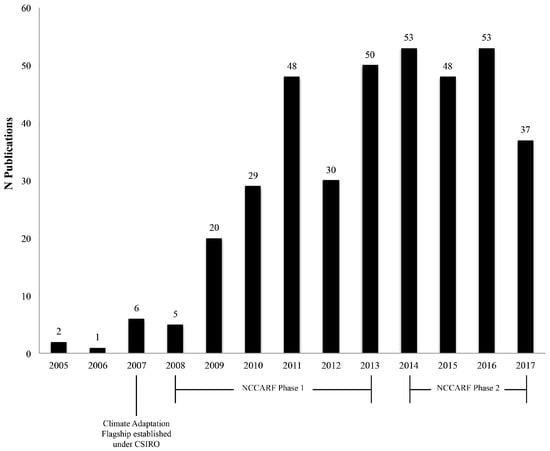

Reporting on adaptation in Australia in the peer-reviewed literature has increased over the past 10 years, consistent with trends observed in other countries [24]. In particular, there was a sharp increase in adaptation reporting observed from 2009 onwards, which may partially be explained by the establishment of the NCCARF in 2008 and the publication of project findings that followed (Figure 2). There is a notable decrease in the number of publications in 2012 compared with 2011 but still higher than 2005–2010. The increase between 2009 and 2014 is followed by a peak and plateau from 2014 onwards, and slight dip in 2017.

Figure 2.

Number of adaptation focused publications by year.

4.2. Adaptation Initiatives Primarily Focus on Groundwork Adaptation Actions

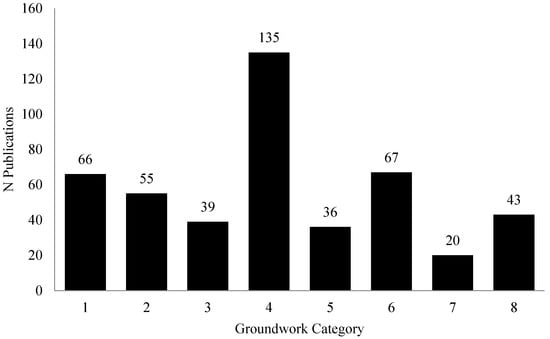

Reported adaptation initiatives are primarily composed of groundwork actions. Of the 390 documents included, 85% (n = 333) report on groundwork actions alone, 12% (n = 45) report on both groundwork and concrete actions, and only 3% (n = 12) report on concrete actions alone. This finding is consistent with the dominant federal government narrative that climate change adaptation has focused on strengthening the science of climate change and addressing knowledge gaps in order to provide the foundations for effective adaptation policies and actions [3]. All eight of the groundwork categories are represented in reported groundwork actions, but there is a particular focus on understanding stakeholder perspectives about climate change and attitudes towards adaptation (Category 4), scenario planning or modelling with an adaptation focus (Category 6), and impact, risk, vulnerability and adaptive capacity assessments (Category 1) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of groundwork adaptation actions. Numbers 1–8 indicate groundwork categories: (1) impact, risk, vulnerability and adaptive capacity assessments; (2) research on adaptation options; (3) conceptual tools; (4) stakeholder perspectives and attitudes towards adaptation; (5) recommendations for adaptation actions; (6) scenario planning or modelling with an adaptation focus; (7) economic analysis focused on adaptation; and (8) policy and framework reviews that suggest adaptation.

Of the articles that report on groundwork adaptation actions, the most common focus is on documenting stakeholder perspectives on climate change and their attitudes towards adaptation (35%, n = 135). Some of these articles seek to understand stakeholders’ views on climate change, risk and adaptation [25], while others explore mechanisms to more effectively engage community members in climate change adaptation planning and implementation [26]. Other studies aim to understand how adaptation is influenced by stakeholder perspectives on climate change, current socio-economic situations, attitudes towards change, and engagement in decision-making [27]. It is suggested that understanding stakeholder perspectives on climate change and their attitudes towards adaptation will increase the likelihood that adaptation strategies will appeal to a broader range of stakeholders and enhance the likelihood of success [28].

The second most frequently documented groundwork adaptation action is Category 6: scenario planning or modelling with an adaptation focus (17%, n = 67). Scenario planning involves the visualization of future conditions and their possible consequences and effects, and modelling involves the representation of those futures through the use of mathematical equations [29]. Scenario planning and modelling are most often used as tools for assessing the uncertainty of long-term climate change and possible adaptation outcomes. In many instances in the literature, these tools are used to assess adaptation options in the agricultural sector (70%, n = 47). This usually involves modelling crop yield production for different scenarios of crop diversification and management practices (e.g., tillage, forage, and weed management) under various climate scenarios [30]. Freshwater management options (water trade) in terms of environmental and socio-economic impacts during extreme events (i.e., droughts) are also a key area of analysis within this category (18%, n = 12) [31]. Additionally, options to adapt infrastructure to deal with extreme events (i.e., cyclones and storms) have been modelled to assess costs-benefits and efficiency [32]. Twelve of the articles from this category focus on modelling the economics of adaptation, which also accounts for 60% of Category 7 [33].

Articles that focus on impact, risk, vulnerability and/or adaptive capacity assessments (Category 1) are the third most frequently reported groundwork action, making up 17% (n = 66) of all included articles. Within this category the primary focus is identifying how climate change is affecting socio-ecological systems and adaptation options [34]. Some of the studies in this category seek to measure and quantify risk [35], while others aim to characterize how climate change is experienced and responded to in a specific sector (e.g., infrastructure, agriculture, fisheries, health) or among a group of people [20]. Several studies use integrated assessments that consider how socio-economic and cultural factors influence how people experience and respond to climate change [36]. Within this category there are also studies that seek to advance climate change adaptation research by developing frameworks for assessing climate change impacts and vulnerability [37]. As a whole, the articles in this category have a strong emphasis on adaptation specifically, including adaptation to the health effects of climate change [38].

Between Category 2: research on adaptation options (14%, n = 55); Category 5: recommendations for adaptation actions (9%, n = 36); and Category 8: policy and framework reviews that suggest adaptation (11%, n = 43), adaptation is primarily approached by reducing vulnerabilities and impacts through a focus on enhancing adaptive capacity. Several studies in these categories examine approaches to strengthen adaptive capacity through planning, natural resource management, and planning policy [39]. There is also a particular focus on examining adaptation options and capacity building in response to the effects of climate change on urban areas [40] and agricultural production [41], particularly through the lenses of freshwater availability and health (see Section 4.4 and Section 4.6). Common themes that emerge for facilitating adaptation include: (i) the importance of integrating local observations and monitoring in adaptation planning [42]; (ii) the role and importance of local and Indigenous knowledge (IK) in adaptation [43]; (iii) the need to consider non-climatic factors that influence adaptation including socio-economic and cultural factors [44]; (iv) the value of inter-disciplinary research and stakeholder participation in adaptation research and planning [45]; and (v) the need for policies and governance to work across scales to support the proactive enhancement of adaptive capacity [46].

4.3. Reporting on Adaptation Is Geographically Focused on Eastern Australia

Reported concrete adaptation actions are primarily from eastern Australia, with a concentration in New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland. Of the 57 articles reporting concrete adaptation actions, 56% (n = 32) concentrate on at least one of the three states, with 14% (n = 8) reporting on concrete actions in two or all three states. The same is true for groundwork adaptation actions (Figure 4). Of the 378 articles reporting groundwork adaptation actions, 40% (n = 154) concentrate on at least one of these three states, with 16% (n = 60) reporting on groundwork actions in two or all three states.

Figure 4.

Geographic distribution of groundwork and concrete adaptation actions across Australia.

Of these three states, Queensland has the highest number of peer-reviewed articles reporting adaptation actions (32%, n = 126), and the highest number of articles reporting adaptation actions among Indigenous populations and in coastal and low-lying areas. All of the articles that focus on Indigenous populations report on research conducted with groups in geographically remote locations such as Torres Strait and Arnhem Land [47].

4.4. Adaptation Actions Heavily Focus on Agriculture

Agriculture is the primary focus of 30% (n = 117) of all included articles. Several of the reviewed articles, 12% (n = 45), model the impacts of climate change on water availability for irrigation, crop yields under different climate and resource availability scenarios, the impacts of pests, and the potential of specific adaptation options in agriculture [48]. Another nine percent (n = 37) of articles document stakeholder perspectives on climate change and attitudes towards adaptation in the agricultural industry, including the perspectives of primary producers [49], and agricultural industry representatives [50]. Consistent with the geographic focus of all reviewed articles, most articles that focus on agriculture are concentrated in eastern Australia. Within the literature focusing on agriculture, 20% (n = 23) of included articles report on adaptation and agriculture in New South Wales, 21% (n = 25) in Victoria, and 30% (n = 35) in Queensland. In addition to these three states, the primary geographic focus of 15% (n = 17) of literature reporting on adaptation and agriculture is the Murray–Darling Basin (MDB), which covers an area that crosses between South Australia, New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland. In total, 18.7% (n = 73) or all included articles focus on adaptation and agriculture in one or multiple of these four states.

In the MDB specifically, climate change has already been documented and includes extreme weather events (i.e., droughts), changes in precipitation patterns, and warmer temperatures with adverse effects on agricultural quality and production [51]. Both groundwork and concrete adaptations have been reported, with most articles addressing adaptation to changing availability of fresh water (63%, n = 22) [52]. Groundwork adaptation actions include understanding farmers’ perspectives and attitudes on climate change adaptation, modelling crop yield production for different farm management and climate scenarios, and evaluating costs and benefits of various irrigation practices [53]. Concrete adaptation actions mostly focus on freshwater management, irrigation efficiency, and crop diversification, as well as earlier planting and sowing [54]. There is a sense of agreement in the literature that infrastructural measures for freshwater management are affecting environmental flows, ultimately reducing the future resilience of the wetland ecosystems in the MDB [55,56].

4.5. Coastal Adaptation Is Prominent and Predominantly Addressed in Groundwork Adaptation Actions

Approximately 85% of the Australian population lives within the coastal region, with more than $226 billion in coastal infrastructure at risk of inundation or erosion based on projected sea-level rise by 2100 [57]. Several of the reviewed articles, 21% (n = 83), focus on adaptation in the coastal zone, of which 96% (n = 80) describe groundwork adaptation actions. These actions mostly seek to protect infrastructure and reduce vulnerability to extreme weather events (43%, n = 36), sea-level rise (52%, n = 43), and climate change in general (50%, n = 42) by assessing the adaptation potential of concrete actions. Most concrete actions can be described as “hard engineering” responses such as building sea walls and groins to cope with rising sea level and extreme storm events, with only a few articles describing soft engineering responses such as increasing wind classifications for new housing to adapt to increasing cyclone and severe storm intensity [58].

Of the 83 articles focusing on adaptation in the coastal zone, most are from eastern Australia: 27% (n = 22) report on coastal adaptation in New South Wales, 25% (n = 21) in Victoria, and 55% (n = 46) in Queensland. Most adaptation actions in these three states respond to temperature increases, climate change in general, sea-level rise, and increased frequency and intensity of severe weather events like cyclones. Sea-level rise is of particular interest to this region, due to the exposure of capital infrastructure to the sea and the risk of inundation, damage, and loss of habitable land [59]. The high volume of groundwork actions reported in this region is consistent with the findings of Bradley et al. (2015), in which the majority of coastal local governments are either beginning to understand the implications of climate change or planning to adapt to its effects. A few articles analyse stakeholder perceptions of risk and their response potential to climate change [27].

4.6. Health Adaptations Focus on Extreme Weather Events

The implications of and adaptation to the health impacts of climate change is prominent in the literature. Of the included articles, 14% (n = 55) focus on the health implications of climate change, with a specific focus on the impacts of drought (n = 8) and heat stress (n = 14). Within these 55 articles, some focus on climate change and mental health, either within specific groups or in response to specific climate-related stressors. For example, several articles explore the relationships between climate change, mental health, and adaptation options in the context of food insecurity, socio-economically stressed populations, or rural populations [38]. Some of these articles seek to understand how farmers’ mental health is affected by drought and two articles, the only articles reviewed that address gender, examine the effect of drought for men and women [60,61]. Reported concrete actions include the development of a rural mental health support telephone line [61], and capacity building in rural areas including training mental health and social workers [62]. Beyond mental health, there is also a focus on a variety of other health-related issues including: increased risk of vector-borne diseases such as dengue fever and Ross River virus [63]; and opportunities to improve infrastructure and city planning in light of climate change, such as green spaces and health service infrastructure [64].

4.7. Concrete Adaptation Actions Are Sometimes Followed by a Second Generation of Groundwork Adaptation Actions

Some articles report on groundwork adaptation actions that occur after concrete adaptation actions have been taken. This second generation of groundwork adaptation actions analyses the efficiency, effectiveness, success and/or profitability of concrete adaptation actions, as well as the potential for maladaptation. Examples include analyses of the feasibility and profitability of snowmaking in the Australian ski industry [65], studies on the potential of water tanks, provided to households to deal with changing water availability, to become mosquito larval sites [63], and research on the use of levees as adaptation measures in the development of flood prone areas [66].

5. Discussion

It is notable that most of the reported climate change adaptation initiatives in Australia can be grouped as groundwork actions, with a strong focus on impact, risk, vulnerability, and adaptive capacity assessments; documenting stakeholder perspectives on climate change and attitudes towards adaptation; and scenario planning or modelling. These actions are precursors to the more tangible concrete actions, which have been the focus of previous reviews. This finding tells us that some government and non-governmental organisations in Australia, and the research community are indeed advanced in adaptation planning for climate change, having generated a substantive body of useable science related to climate change and adaptation issues, and are well positioned to advance the research agenda from adaptation preparation to implementation.

The finding that reporting on adaptation in Australia in the peer-reviewed literature has increased over the past 10 years is likely influenced by the amount of funding available for adaptation research in Australia. The NCCARF funded approximately 100 research projects and eight networks that focused on building capacity for adaptation in Australia between 2008 and 2013. The increase in the number of articles reporting on adaptation in Australia between 2008 and 2017, particularly the period between 2013 and 2016, can likely be attributed to the time it takes to publish articles in peer-reviewed journals (up to two years, or even more depending on the journal). It is difficult to determine whether the dips in 2012 and in 2017 are representative of downturns in the amount of adaptation research completed, reviewed, and published in Australia those years, or if these numbers may be influenced by other factors such as the time involved in publishing research findings.

The finding that government funding for adaptation research influences adaptation reporting is significant. Many people, communities, industries, and governments deal with changing climatic conditions on a daily basis without labelling or reporting their actions as adaptation per se. To track adaptation, actions need to be recorded, and this is often done through research. This finding reinforces the importance of funding for climate change adaptation research that results in measureable outputs like peer-reviewed articles. Furthermore, reviews of climate change adaptation should be performed periodically and capture the longest time-scale possible since adaptation is an on-going and iterative process.

The focus of reported concrete adaptation actions in eastern Australia, particularly within New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland may be partially explained by demographics, the location of climate sensitive industries, and the location of universities. The majority of the Australian population (~77%) lives in these states (NSW: 7,480,228; VIC: 5,926,624; QLD: 4,703,193 habitants) and the country’s three largest cities—Sydney (NSW), Melbourne (VIC), and Brisbane (QLD)—are also the capital cities of the three states [67]. Taken together, these three cities make up 49% of Australia’s national population. The location of these cities, and the majority of the Australian population living along the coast, explains the focus of adaptation research in the coastal zone. In addition, climate sensitive industries including tourism (e.g., Great Barrier Reef, Gold Coast, and Sunshine Coast in Queensland) and agriculture (e.g., Murray–Darling Basin) are located in these three states (see Section 4.4). It is also noteworthy that 29 of the 43 accredited universities in Australia are located in these states, which might help to explain the geographic focus of the published research.

The focus of health adaptations on extreme weather events may be driven partly by the direct connections that can be made between an extreme event and health impacts, particularly among sensitive populations. Extreme heat and drought have direct and indirect health effects for some people, notably farmers, and research has focused on examining the relationships between extreme weather events and farmer’s health. Less research has focused on the cumulative effects of climate change for human health, such as repeated exposure to bush fire smoke or the longer-term effects of extreme heat on physical activity and well-being.

While in other developed nations, climate change adaptation is dominated by actions in the infrastructure, transportation and utilities sectors [10], Australia has a stronger focus on agriculture and freshwater management. This is likely a reflection of the pre-adaptation state of the nation’s climate, being the driest inhabited continent globally and exposed to long periods of drought.

6. Conclusions

Previous reviews of climate change adaptation in developed nations have focused on concrete actions, of which few were reported to be occurring in Australia. Our purpose here is to expand the scope of existing reviews to include both groundwork and concrete adaptation actions to characterise how Australia is adapting to climate change from the perspective of the peer-reviewed literature. Our findings provide compelling evidence that adaptation to climate change is indeed happening in Australia. The main results of the review are: (i) most of the reported climate change adaptation initiatives in Australia can be grouped as groundwork actions; (ii) reporting on adaptation within Australia in the peer-reviewed literature has increased over the past 10 years; (iii) reporting on adaptation is geographically focused on eastern Australia; (iv) adaptation actions heavily focus on agriculture; (v) coastal adaptation is prominent and predominantly addressed in groundwork adaptation actions; (vi) health adaptations focus on extreme weather events; and (vii) concrete adaptation actions are sometimes followed by a second generation of groundwork adaptation actions.

A limitation of this review is the exclusive focus on peer-reviewed literature. It is acknowledged that not all adaptation efforts are captured in the peer-reviewed literature and thus some were surely missed in this study. This includes, for example, the over 150 National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility (NCCARF) final project reports available on the NCCARF website. That said, several of these reports are also published in the peer-reviewed literature and are included in this review. The findings are thus best characterized as providing a proxy of the state of adaptation in Australia from the perspective of the peer-reviewed literature.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this review help us to better understand how climate change adaptation is happening in Australia at a time when tracking adaptation is critical in national and international climate change financing and decision-making. The results reveal that adaptation is a process including groundwork and concrete actions, and that most adaptations in Australia focus on groundwork actions. A misrepresentation of the state of adaptation in a particular place (e.g., by only focusing on concrete actions), in this case Australia, risks negating important steps needed to formulate sustainable adaptation actions and could lead to maladaptation. Taken together with the knowledge, observations, and experiences of people living in Australia, the information generated by the groundwork actions described here could form the basis for advancing the adaptation research and policy agendas from analyses currently weighted heavily toward risk assessment and modelling to the development and implementation of concrete adaptation actions.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/9/3280/s1, S1: articles included in the analysis and S2: articles excluded from the analysis.

Author Contributions

T.D.P. conceived the project, designed the methodology, collected and analyzed the data, and led writing the paper; E.H.R. and D.F. collected and analyzed the data, and helped write the paper; J.D.F. helped design the methodology, analyzed the data, and helped write the paper.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to four anonymous reviewers for constructive and insightful comments. The research was supported by a University of the Sunshine Coast Fellowship grant and an Australia Awards Scholarship from the AusAid Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Head, L.; Adams, M.; McGregor, H.V.; Toole, S. Climate change and Australia. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, T.D.; Heron, S.F.; Ortiz, J.C.; Mumby, P.J.; Grech, A.; Ogawa, D.; Eakin, C.M.; Leggat, W. Climate change disables coral bleaching protection on the Great Barrier Reef. Science 2016, 352, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asseng, S.; Pannell, D.J. Adapting dryland agriculture to climate change: Farming implications and research and development needs in Western Australia. Clim. Chang. 2013, 118, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggs, P.J.; Bennett, C.M. Climate Change, Aeroallergens, Natural Particulates, and Human Health in Australia: State of the Science and Policy. Asia-Pac. J. Public Health 2011, 23, 46S–53S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Annex I: Atlas of Global and Regional Climate Projections. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1311–1390. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger, A.; Kitching, R.L.; Chiew, F.; Hughes, L.; Newton, P.C.D.; Schuster, S.S.; Tait, A.; Whetton, P. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability—Part B: Regional Aspects, Australiasia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1371–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Biesbroek, G.R.; Swart, R.J.; Carter, T.R.; Cowan, C.; Henrichs, T.; Mela, H.; Morecroft, M.D.; Rey, D. Europe adapts to climate change: Comparing National Adaptation Strategies. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesnikowski, A.; Ford, J.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Barrera, M.; Berry, P.; Henderson, J.; Heymann, S.J. National-level factors affecting planned, public adaptation to health impacts of climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Pearce, T. What we know, do not know, and need to know about climate change vulnerability in the western Canadian Arctic: A systematic literature review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2010, 5, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Paterson, J. A systematic review of observed climate change adaptation in developed nations. Clim. Chang. 2011, 106, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrang-Ford, L.; Ford, J.; Paterson, J. Are we adapting to climate change? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; Billy, J.; Tapim, A. Indigenous Australians’ knowledge of weather and climate. Clim. Chang. 2010, 100, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prober, S.M.; O’Connor, M.H.; Walsh, F.J. Australian Aboriginal peoples’ seasonal knowledge: A potential basis for shared understanding in environmental management. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Allen Consulting Group. Climate Change Risk and Vulnerability: Promoting an Efficient Adaptation Response in Australia; Report Prepared by Allen Consulting Group for the Australian Government; Australian Greenhouse Office: Canberra, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government. National Climate Change Adaptation Framework; Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency: Canberra, Australia, 2007.

- CSIRO. Program 1: National Research Flagships—The Highlights, Objectives and Performance of Our National Research Flagships. CSIRO, 2015. Available online: http://www.csiro.au/en/About/Reports/Annual-reports/13-14-annual-report/Part2/Performance-portfolio/Flagships (accessed on 10 July 2015).

- Australian Government. National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility; Department of Environment: Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility. NCCARF 2008-2013: The First Five Years; NCCARF: Southport, Australia, 2014; Available online: https://www.nccarf.edu.au/sites/default/files/research_content_downloads/NCC030-report%20FA.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Fidelman, P.; Leitch, A.; Nelson, D. Unpacking multilevel adaptation to climate change in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M.; van Putten, I.; Sheaves, M. The pace and progress of adaptation: Marine climate change preparedness in Australia’s coastal communities. Mar. Policy 2015, 53, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalau, J.; Preston, B.L.; Maloney, M.C. Is adaptation a local responsibility? Environ. Sci. Pol. 2015, 48, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrang-Ford, L.; Pearce, T.; Ford, J. Systematic review approaches for climate change adaptation research. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.; Pitsouni, E.; Malietzis, G.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and Weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, J.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Bunce, A.; McKay, C.; Irwin, M.; Pearce, T. The status of climate change adaptation in Africa and Asia. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2014, 14, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrey, C.; Byrne, J.; Matthews, T.; Davison, A.; Portanger, C.; Lo, A. Cultivating climate justice: Green infrastructure and suburban disadvantage in Australia. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 89, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, B.; Wilson, G.; Namarnyilk, I.; Nadji, S.; Cahill, J.; Bird, D. Testing the scoping phase of a bottom-up planning guide designed to support Australian Indigenous rangers manage the impacts of climate change on cultural heritage sites. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1197–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrick-Barr, C.E.; Smith, T.F.; Thomsen, D.C.; Preston, B.L. Perceptions of Risk among Households in Two Australian Coastal Communities. Geogr. Res. 2015, 53, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buys, L.; Miller, E.; van Megen, K. Conceptualising climate change in rural Australia: Community perceptions, attitudes and (in)actions. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2012, 12, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, M.; Ford, J.D.; Pearce, T.; Harper, S.L.; IHACC Research Team. Participatory scenario planning and climate change impacts, adaptation and vulnerability research in the Arctic. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2018, 79, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Chenu, K.; Chapman, S.C. Velocity of temperature and flowering time in wheat—Assisting breeders to keep pace with climate change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, S.A.; Zuo, A.; Bjornlund, H. Investigating the delayed on-farm consequences of selling water entitlements in the Murray-Darling Basin. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 145, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Stewart, M.G. Cyclone damage risks caused by enhanced greenhouse conditions and economic viability of strengthened residential construction. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2011, 12, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Behrendt, K.; Bange, M. Economics and Risk of Adaptation Options in the Australian Cotton Industry. Agric. Syst. 2017, 150, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.E.; Welch, D.J. Climate change implications for Torres Strait fisheries: Assessing vulnerability to inform adaptation. Clim. Chang. 2016, 135, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Nguyen, C.T.; McLean, G.; Chapman, S.C.; Zheng, B.; van Oosterom, E.J.; Hammer, G.L. Quantifying high temperature risks and their potential effects on sorghum production in Australia. Field Crop. Res. 2017, 211, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardsley, D.K.; Wiseman, N.D. Climate change vulnerability and social development for remote indigenous communities of South Australia. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2012, 22, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, R.; Barrett, D.; Gao, L.; Zhou, M.; Renzullo, L.; Emelyanova, I. A spatial assessment framework for evaluating flood risk under extreme climates. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 538, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowles, D.C. Climate change and health adaptation: Consequences for indigenous physical and mental health. Ann. Glob. Health 2015, 81, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheaves, M.; Sporne, I.; Dichmont, C.M.; Bustamante, R.; Dale, P.; Deng, R.; Dutra, L.X.C.; van Putten, I.; Savina-Rollan, M.; Swinbourne, A. Principles for operationalizing climate change adaptation strategies to support the resilience of estuarine and coastal ecosystems: An Australian perspective. Mar. Policy 2016, 68, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isler, P.L.; Merson, J.; Roser, D. ‘Drought proofing’ Australian cities: Implications for climate change adaptation and sustainability. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2010, 46, 351–359. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, P.R.; Brooke, S.J.; Moran, M.A.; Sadras, V.O. Pruning after budburst to delay and spread grape maturity. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2017, 23, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; Alexander, L.; McInnes, K.; Church, J.; Nicholls, N.; White, N. An assessment of climate change impacts and adaptation for the Torres Strait Islands, Australia. Clim. Chang. 2010, 102, 405–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, S.; Parsons, M.; Olawsky, K.; Kofod, F. The role of culture and traditional knowledge in climate change adaptation: Insights from East Kimberley, Australia. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mee, K.J.; Instone, L.; Williams, M.; Palmer, J.; Vaughan, N. Renting over troubled waters: An urban political ecology of rental housing. Geogr. Res. 2014, 52, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardsley, D.K.; Sweeney, S.M. Guiding climate change adaptation within vulnerable natural resource management systems. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrao-Neumann, S.; Davidson, J.L.; Baldwin, C.L.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Ellison, J.C.; Holbrook, N.J.; Howes, M.; Jacobson, C.; Morgan, E.A. Marine governance to avoid tipping points: Can we adapt the adaptability envelope? Mar. Policy 2016, 65, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, K.E.; Westoby, R.; Smithers, S.G. Identification of limits and barriers to climate change adaptation: Case study of two islands in Torres Strait, Australia. Geogr. Res. 2017, 55, 438–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.G.; Ryan, M.H.; Colmer, T.D.; Real, D. Prioritisation of novel pasture species for use in water-limited agriculture: A case study of Cullen in the Western Australian wheatbelt. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2011, 58, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehne, G. How Do Farmers’ Climate Change Beliefs Affect Adaptation to Climate Change? Soc. Nat. Res. 2014, 27, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.; Park, S.E.; Marshall, N.A. Enhancing adaptation outcomes for transformation: Climate change in the Australian wine industry. J. Wine Res. 2015, 26, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loch, A.; Adamson, D. Drought and the rebound effect: A Murray–Darling Basin example. Nat. Hazards 2015, 79, 1429–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasiewicz, A.; Pittock, J.; Finlayson, M. Institutional challenges of adopting ecosystem-based adaptation to climate change. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2016, 16, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, M.; Clarke, J.; Whittenbury, K. Limits to adaptation: Reducing irrigation water in the Murray-Darling Basin dairy communities. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 58, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocker, N.; Head, L.; Dun, O.; Spaven, T. Experimenting with agricultural diversity: Migrant knowledge as a resource for climate change adaptation. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 57, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittock, J. Lessons from adaptation to sustain freshwater environments in the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2013, 4, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittock, J.; Finlayson, C.M. Climate change adaptation in the Murray-Darling Basin: Reducing resilience of wetlands with engineering. Aust. J. Water Res. 2013, 17, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. Climate Change Risks to Australia’s Coast: A First Pass National Assessment; Department of Climate Change, Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2009. Available online: https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/fa553e97-2ead-47bb-ac80-c12adffea944/files/cc-risks-full-report.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Stewart, M.G.; Wang, X.; Willgoose, G.R. Direct and indirect cost-and-benefit assessment of climate adaptation strategies for housing for extreme wind events in Queensland. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B.; Khoo, Y.B.; Inman, M.; Wang, C.H.; Tapsuwan, S.; Wang, X. Assessing inundation damage and timing of adaptation: Sea level rise and the complexities of land use in coastal communities. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2014, 19, 551–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, M. Gender and climate change in Australia. J. Sociol. 2011, 47, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C.R.; Berry, H.L.; Tonna, A.M. Improving the mental health of rural New South Wales communities facing drought and other adversities. Aust. J. Rural Health 2011, 19, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D. Enduring drought then coping with climate change: Lived experience and local resolve in rural mental health. Rural Soc. 2009, 19, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, N.W.; Cooper, R.D.; Mottram, P.; Sweeney, A.W. Australia’s dengue risk driven by human adaptation to climate change. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambrick, H.J.; Capon, A.G.; Barnett, G.B.; Beaty, R.M.; Burton, A.J. Climate change and health in the Urban environment: Adaptation opportunities in Australian cities. Asia-Pac. J. Public Health 2011, 23, 67S–79S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennessy, K.J.; Whetton, P.H.; Walsh, K.; Smith, I.N.; Bathols, J.M.; Hutchinson, M.; Sharples, J. Climate change effects on snow conditions in mainland Australia and adaptation at ski resorts through snowmaking. Clim. Res. 2008, 35, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, C. Building walls around flood problems: The place of levees in Australian flood management. Aust. J. Water Res. 2015, 19, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Demographic Statistics, December 2014; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2015. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3101.0 (accessed on 12 September 2018).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).