Tensions Between Firm Size and Sustainability Goals: Fair Trade Coffee in the United States

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How is the U.S. fair trade coffee industry structured with respect to firm size and degree of engagement with fair trade?

- How have the firms with the highest volumes of fair trade purchases responded to tensions between size and sustainability goals?

2. Firm Size and Sustainability Goals

2.1. Tensions

2.2. Tensions in Fair Trade

3. How is the U.S. Fair Trade Coffee Industry Structured with Respect to Firm Size and Engagement with Fair Trade?

3.1. Methods

3.2. Results

3.2.1. The Global Context

3.2.2. The U.S. Context

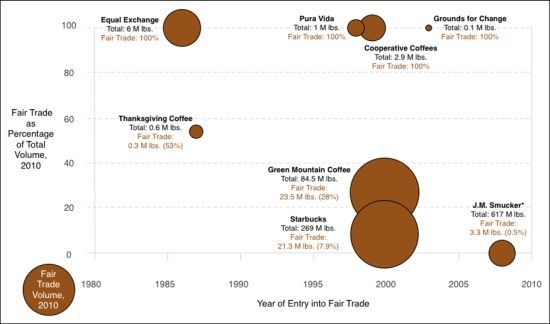

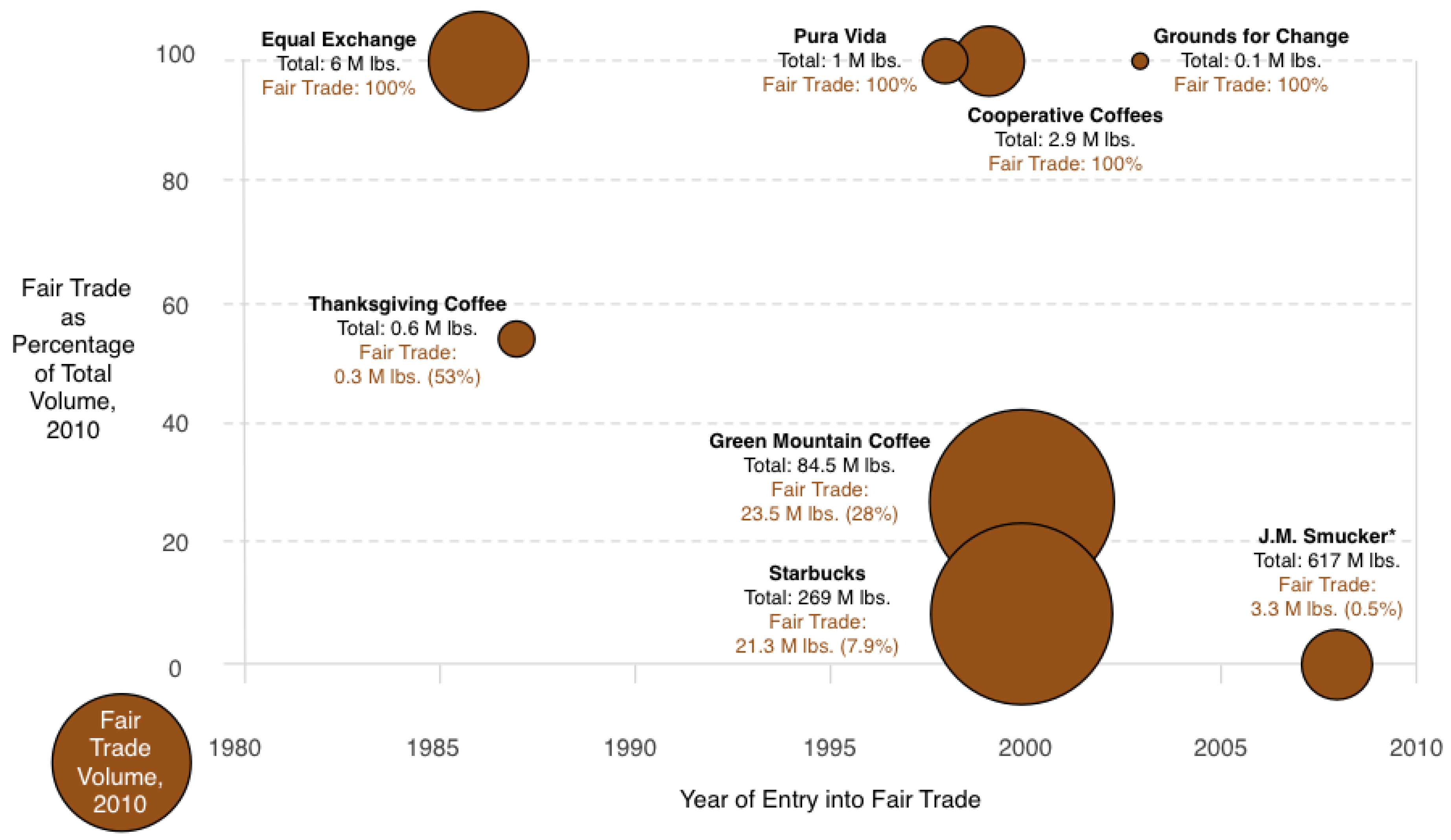

3.2.3. Characteristics of Firms with Highest Proportion of Fair Trade Purchases

4. How Have The Largest U.S. Fair Trade Coffee Firms Responded to Size/Sustainability Tensions?

4.1. Methods

4.2. Results

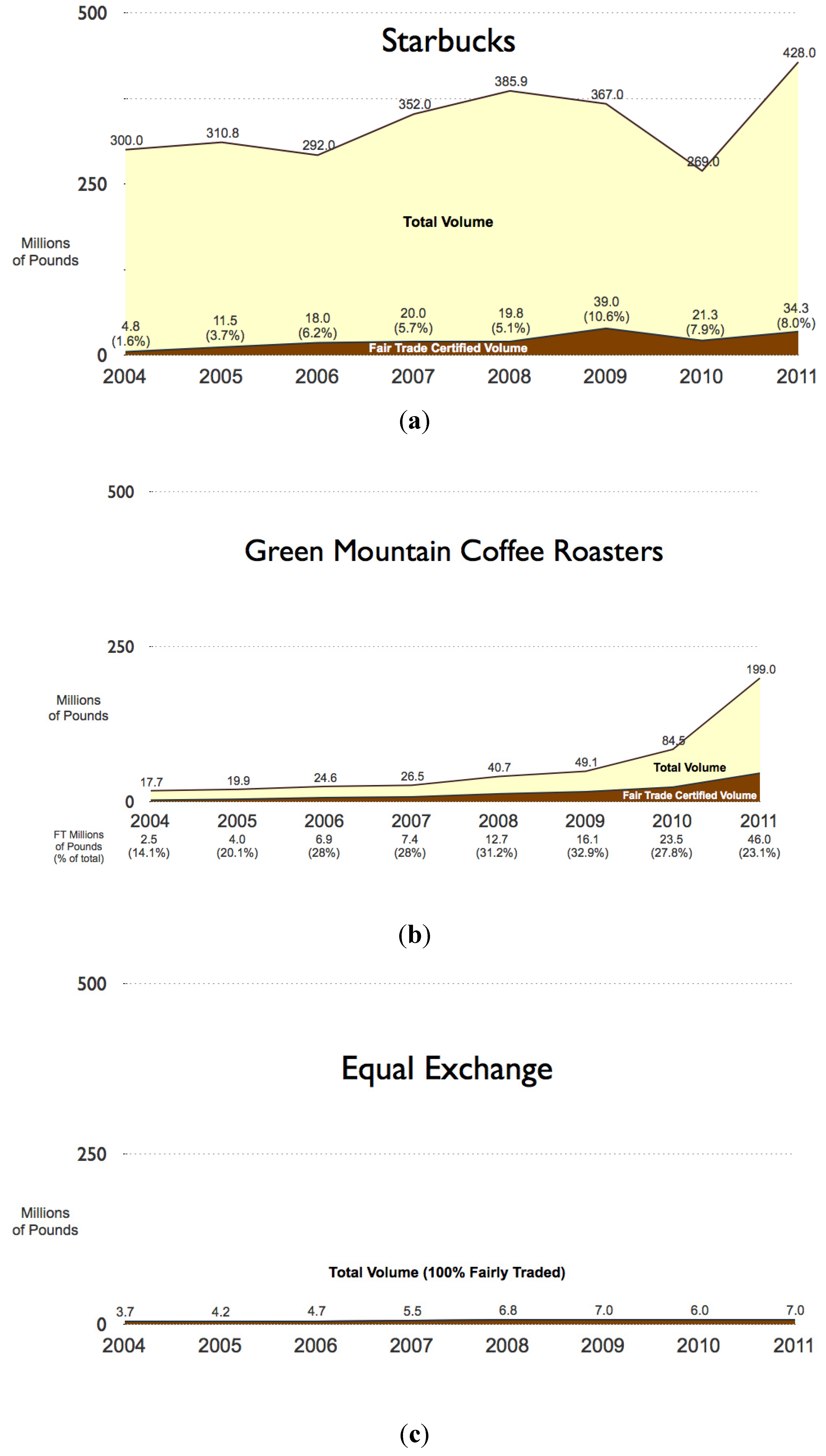

4.2.1. Commitment to Fair Trade Volume and Percentage of Total Volume

4.2.2. Commitment to Fair Trade Standards

5. Conclusions

Conflict of Interest

References

- Boström, M.; Klintman, M. Eco-Standards, Product Labelling and Green Consumerism; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P.H.; Allen, P. Beyond organic and Fair Trade? An analysis of ecolabel preferences in the United States. Rural Sociol. 2010, 75, 244–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynolds, L.; Murray, D.; Heller, A. Regulating sustainability in the coffee sector: A comparative analysis of third-party environmental and social certification initiatives. Agric. Human Values 2007, 24, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids—Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Venturing 2010, 25, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.; Doherty, B.; Knox, S. The rise and stall of a Fair Trade pioneer: The cafédirect story. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridell, M.; Hudson, I.; Hudson, M. With friends like these: The corporate response to Fair Trade coffee. Rev. Radical Pol. Econ. 2008, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P.H. Consolidation in the North American organic food processing sector, 1997 to 2007. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2009, 16, 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee, D. Weak coffee: Certification and co-optation in the Fair Trade movement. Soc. Probl. 2012, 59, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S. The brawl over Fair Trade coffee. The Nation. 22 August 2012. Available online: http://www.thenation.com/article/169515/brawl-over-fair-trade-coffee (accessed on 5 October 2012).

- Gram, D. Fair Trade purists cry foul at including big farms. The Associated Press, 31 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gram, D. Too much caffeine? Fair Trade coffees fighting. The Associated Press, 21 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chesto, J. Mass market; All is not mellow with Fair Trade coffee companies. The Patriot Ledger, 23 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W. A question of fairness. The New York Times, 24 November 2011; B1. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, B.; Davies, I.A.; Tranchell, S. Where now for fair trade? Bus. Hist. 2012, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, D. What do corporations have to do with Fair Trade? Positive and normative analysis from a value chain perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K. Supermarkets as organic retailers: Impacts for the Australian organic sector. In Supermarkets and Agri-Food Supply Chains: Transformations in the Production and Consumption of Foods; Burch, D., Lawrence, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2007; pp. 154–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, E. Stemming the tide of “greenwash”. Consum. Policy Rev. 2008, 18, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee, D. Brewing Justice: Fair Trade Coffee, Sustainability, and Survival; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee, D.; Howard, P. Corporate cooptation of organic and fair trade standards. Agric. Human Values 2010, 27, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, M.; Konefal, J.; Constance, D. A tripartite standards regime analysis of the contested development of a sustainable agriculture standard. Agric. Human Values 2012, 29, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templet, P.H. Grazing the commons: An empirical analysis of externalities, subsidies and sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 1995, 12, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M. The Consumer Trap: Big Business Marketing in American Life; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pagell, M.; Wu, Z. Building a more complete theory of sustainable supply chain management using case studies of 10 exemplars. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 45, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Timmer, C.P.; Barrett, C.B.; Berdegué, J. The rise of supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Am. J. Agr. Econ. 2003, 85, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Timmer, P.; Berdegue, J.A. The rapid rise of supermarkets in developing countries: Induced organizational, institutional, and technological change in agrifood systems. Electron. J. Agric. Dev. Econ. 2004, 1, 168–183. [Google Scholar]

- Fridell, G. The co-operative and the corporation: Competing visions of the future of Fair Trade. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, J.; Cubbage, F.; Mercer, E.; Sills, E. The search for value and meaning in the cocoa supply chain in Costa Rica. Sustainability 2012, 4, 1466–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, D. Interpretive barriers to successful product innovation in large firms. Organ. Sci. 1992, 3, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvergne, P.; Lister, J. Big brand sustainability: Governance prospects and environmental limits. Global Environ. Change 2012, 22, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Audretsch, D.B. Innovation, market structure, and firm siz. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1987, 69, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoutre, J.; Heene, A. Investigating the impact of firm size on small business social responsibility: A critical review. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.M.; Méndez, V.E.; Fox, J.A. Cultivating Sustainable Coffee: Persistent paradoxes. In Confronting the Coffee Crisis: Fair Trade, Sustainable Livelihoods and Ecosystems in Mexico and Central America; Bacon, C.M., Méndez, V.E., Gliessman, S.R., Goodman, D., Fox, J.A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 337–372. [Google Scholar]

- Fair Trade USA 2011 Almanac; Fair Trade USA: Oakland, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–61. Available online: http://fairtradeusa.org/sites/default/files/Almanac%202011.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2012).

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G. Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair-trade coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnot, C.; Boxall, P.C.; Cash, S.B. Do Ethical Consumers Care About Price? A Revealed Preference Analysis of Fair Trade Coffee Purchases. Canadian J. Agric. Econ./Rev. Canadienne d’Agroecon. 2006, 54, 555–565. [Google Scholar]

- Didier, T.; Sirieix, L. Measuring consumer’s willingness to pay for organic and Fair Trade products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynolds, L.T. Fair Trade: Social regulation in global food markets. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, M.-C.; Pérez-Grovas, V. Fair Trade coffee in Mexico: At the center of the debates. In Fair Trade: The Challenges of Transforming Globalization; Raynolds, L.T., Murray, D., Wilkinson, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 138–156. [Google Scholar]

- Besky, S. Can a plantation be fair? Paradoxes and possibilities in Fair Trade Darjeeling tea certification. Anthropol. Work Rev. 2008, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, J.; Pritchard, B. Fairness and ethicality in their place: the regional dynamics of fair trade and ethical sourcing agendas in the plantation districts of South India. Environ. Plann. A 2010, 42, 1833–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynolds, L.T. Fair Trade flowers: Global certification, environmental sustainability, and labor standards. Rural Sociol. 2012, 77, 493–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfecto, I.; Vandermeer, J.; Mas, A.; Pinto, L.S. Biodiversity, yield, and shade coffee certification. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 54, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfecto, I.; Armbrecht, I.; Philpott, S.M.; Soto-Pinto, L.; Dietsch, T.V. Shaded coffee and the stability of rainforest margins in northern Latin America. In Stability of Tropical Rainforest Margins; Tscharntke, T., Leuschner, C., Zeller, M., Guhardja, E., Bidin, A., Eds.; Environmental Science and Engineering; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 225–261. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez, V.E. Farmers’ livelihoods and biodiversity conservation in a coffee landscape of El Salvador. In Confronting the Coffee Crisis: Fair Trade, Sustainable Livelihoods and Ecosystems in Mexico and Central America; Bacon, C.M., Méndez, V.E., Gliessman, S.R., Goodman, D., Fox, J.A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 207–236. [Google Scholar]

- Raynolds, L.T. Mainstreaming Fair Trade coffee: From partnership to traceability. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, C. Information Visualization: Perception for Design, 2nd ed; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P.H. Visualizing consolidation in the global seed industry: 1996-2008. Sustainability 2009, 1, 1266–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffee Barometer; Tropical Commodity Coalition: The Hague, Netherlands, 2009; pp. 1–20.

- Green Mountain Coffee Roasters Corporate Social Responsibility Report; Green Mountain Coffe Roasters: Waterbury, VT, USA, 2010; pp. 1–68.

- Starbucks Global Responsibility Report. Starbucks: Seattle, WA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–15.

- Fair Trade USA 2010 Almanac; Fair Trade USA: Oakland, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–63.

- Obermiller, C.; Burke, C.; Talbott, E.; Green, G.P. "Taste great or more fulfilling”: The effect of brand reputation on consumer social responsibility advertising for Fair Trade coffee. Corp. Reputation Rev. 2009, 12, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodnik, A.; Conroy, M.E. Fair Trade Coffee in the United States: Why Companies Join the Movement. In Fair Trade: The Challenges of Transforming Globalization; Raynolds, L.T., Murray, D., Wilkinson, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, I. Alliances and networks: Creating success in the UK Fair Trade market. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starbucks Global Responsibility Report; Starbucks: Seattle, WA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–22.

- Green Mountain Coffee Roasters Corporate Social Responsibility Report; Green Mountain Coffee Roasters: Waterbury, VT, USA, 2011; pp. 1–75.

- Equal Exchange Annual Report; Equal Exchange: Bridgewater, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–16.

- An open letter to Green Mountain Coffee Roasters from Equal Exchange. 21 May 2012. Available online: http://www.equalexchange.coop/gmcr-ad.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2012).

- Hill, C. Fair Trade USA’s coffee policy comes under fire. East Bay Express. 25 April 2012. Available online: http://www.eastbayexpress.com/ebx/fair-trade-usas-coffee-policy-comes-under-fire/Content?oid=3184779 (accessed on 5 October 2012).

- Robinson, P. Trying (but Failing) to Understand Arguments in Support of Fair Trade USA. Available online: http://smallfarmersbigchange.coop/2012/09/26/trying-but-failing-to-understand-arguments-in-support-of-fair-trade-usa/ (accessed on 10 October 2012).

- Robinson, P. Banana Producers from the Dominican Republic Say no to Plantations! Available online: http://smallfarmersbigchange.coop/2012/06/14/4866/ (accessed on 10 October 2012).

- Robinson, P. Join with us to support authentic Fair Trade. Available online: http://smallfarmersbigchange.coop/2012/01/07/join-with-us-to-support-authentic-fair-trade/ (accessed on 10 October 2012).

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Howard, P.H.; Jaffee, D. Tensions Between Firm Size and Sustainability Goals: Fair Trade Coffee in the United States. Sustainability 2013, 5, 72-89. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5010072

Howard PH, Jaffee D. Tensions Between Firm Size and Sustainability Goals: Fair Trade Coffee in the United States. Sustainability. 2013; 5(1):72-89. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoward, Philip H., and Daniel Jaffee. 2013. "Tensions Between Firm Size and Sustainability Goals: Fair Trade Coffee in the United States" Sustainability 5, no. 1: 72-89. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5010072