1. Introduction

Biogas is a renewable energy carrier produced by anaerobic digestion of biomass. Various kinds of biomass can be utilized for biogas production, such as sewage sludge, agricultural residues (e.g., manure), biogenic waste and energy crops [

1]. Power production based on biogas is more reliable than other renewable energy sources, e.g., wind and solar, and can be used to cover power demand peaks or fluctuations in production due to unfavorable weather conditions. Biogas can be utilized directly in combined heat and power units (CHP) or can be upgraded to biomethane and transported to large gas power stations via the gas grid.

The Renewable Energy Act (EEG) and its amendments have led to a rapid increase in biogas exploration in Germany [

1]. Here, approximately 8075 biogas plants with a total installed capacity of 4.1 GW were in operation in 2016 [

2]. The latest amendments promote the restructuring of biogas plants to flexible operation, and approximately 31% of the installed capacity [

2] have already been modernized. This allows power production to be adapted more to demand. Currently, 182 biogas plants upgrade biogas to biomethane and inject it into the gas grid [

2]. These numbers show that, in Germany, there is a significant biogas infrastructure in place and the process of adapting it to the needs of a future renewable power supply has already begun. However, to allow an economically and environmentally viable operation, this infrastructure needs a reliable, affordable and sustainable supply of biomass. In 2014, substrate input (based on mass) was composed of 52% energy crops (of which 73% was maize) and 43% manure [

2]. However, the proportion of biogas produced from energy crops is considerably higher than their proportion by mass, because they have a higher specific biogas and methane yield than other biogas substrates, e.g., manure. In Germany, about 1.4 million ha energy crops are grown for biogas production, of which 0.9 million ha are biogas maize [

2]. This reveals the great importance of energy crops—and in particular energy maize—in Germany. The high economic viability of maize [

3] for biogas production is given by its high methane yield, easy digestibility, and well-established, optimized crop production and harvest logistics, including storage as silage.

However, the strong reliance of the biogas sector on maize as substrate crop can lead to environmental problems and a low acceptance in public opinion. The environmental profile of maize cultivation is characterized by a high nitrogen fertilizer input, high risk of erosion and leaching, and negative impact on biodiversity [

4,

5,

6]. In particular, the regional concentration in areas with high biogas plant densities can lead to environmental problems, such as surface and groundwater pollution through erosion and leaching, and losses in biodiversity and soil organic matter due to the high proportion of maize in crop rotations [

7]. Other aspects are also criticized, such as the high concentration of maize in the landscape and the use of good agricultural land for growing energy instead of food crops. For these reasons, the sustainability of the biogas sector is often questioned not only by environmentalists but also by the general public.

The replacement of maize (Zea mays) by crops with a more benign environmental profile is seen as one route towards more sustainable biogas production. These crops, however, should have an equally high yield and biomass supply potential as maize. The high-yielding and nutrient-efficient perennial C4 grasses miscanthus and switchgrass are considered promising options.

The miscanthus genotype,

Miscanthus x giganteus, was introduced into Europe in 1935 and is today still the only commercial genotype available on the market [

8]. However, promising breeding efforts have begun in recent years and latest results show the suitability of novel genotypes for marginal lands and the potential contribution of miscanthus to greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation [

9]. Progress in upscaling miscanthus cultivation and crop production has also raised interest in the industrial sector [

10]. Miscanthus’ beneficial environmental profile is mainly due to its perennial nature and because soil organic carbon tends to increase when arable land is converted to its cultivation [

11]. It is a very resource- and land-use efficient crop with efficient nutrient-recycling mechanisms and high net energy yields per unit area [

12,

13]. For this reason, the global warming potential (GWP) and the resource depletion potential of miscanthus cultivation is low [

14,

15]. Miscanthus is suitable for biogas production and has a high methane yield potential per unit area [

16,

17,

18]. For anaerobic digestion, the biomass is harvested before winter, which increases the yield and digestibility [

18]. Whittaker et al. [

19] proved storage of green miscanthus via ensilaging to be feasible with losses in a similar range as for maize. These losses were significantly reduced by the addition of silage additives [

19]. Compared to the conventional harvest of dry biomass in early spring, a green harvest in late autumn prevents leaf fall over winter, which leads to a higher nutrient removal than at spring harvest [

13,

18]. However, the recycling of fermentation residues is assumed to at least partially compensate for this removal and contribute to the formation of soil organic carbon. Nevertheless, the effects of a green cut on the development of soil carbon and fertility needs to be further investigated and is for this reason not considered in this study.

The crop production and environmental profile of switchgrass (

Panicum virgatum) is comparable to that of miscanthus, except establishment via seeds and not rhizomes. Switchgrass is native to the US and Canada, where it has been developed as a promising energy grass [

20]. It is also suitable for biogas production as harvest of green biomass and even double-cutting is possible [

21]. Although yields are generally lower than with

Miscanthus x giganteus [

22], switchgrass can perform equally well under abiotic stress, such as cold and drought [

23]. Its major advantage over the miscanthus genotypes presently available (mainly propagated clonally via rhizomes) is its low-cost establishment via seeds. Currently, switchgrass is not commercially cultivated in Germany and miscanthus is grown on an estimated area of 4000 hectares, mainly for combustion purposes [

9]. Extending the utilization to anaerobic digestion could contribute to the sustainability and crop diversity (important for biodiversity) of the biogas sector.

The objective of this paper is to assess and compare the environmental performance in biogas production of the perennial C4 grasses miscanthus and switchgrass and the annual C4 crop maize. This was done in a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) according to ISO standards 14040 and 14044 [

24,

25], using data from a field trial and laboratory measurements. Wagner and Lewandowski [

26] showed that, when analyzing the environmental performance of biobased value chains, it is crucial to consider more impact categories than just global warming potential (GWP). Therefore, the following impact categories were assessed to estimate the environmental performance of the crops and their subsequent utilization: climate change (CC)—which corresponds to the GWP, freshwater eutrophication (FE), marine eutrophication (ME), terrestrial acidification (TA) and fossil fuel depletion (FFD). The impact categories FE, ME and TA were chosen as eutrophication and acidification have been identified as important impact categories for agricultural systems. The category marine eutrophication represents the impact of nitrogen on biomass growth in aquatic ecosystems. Freshwater eutrophication represents the same impact, but caused by phosphorus [

27,

28].

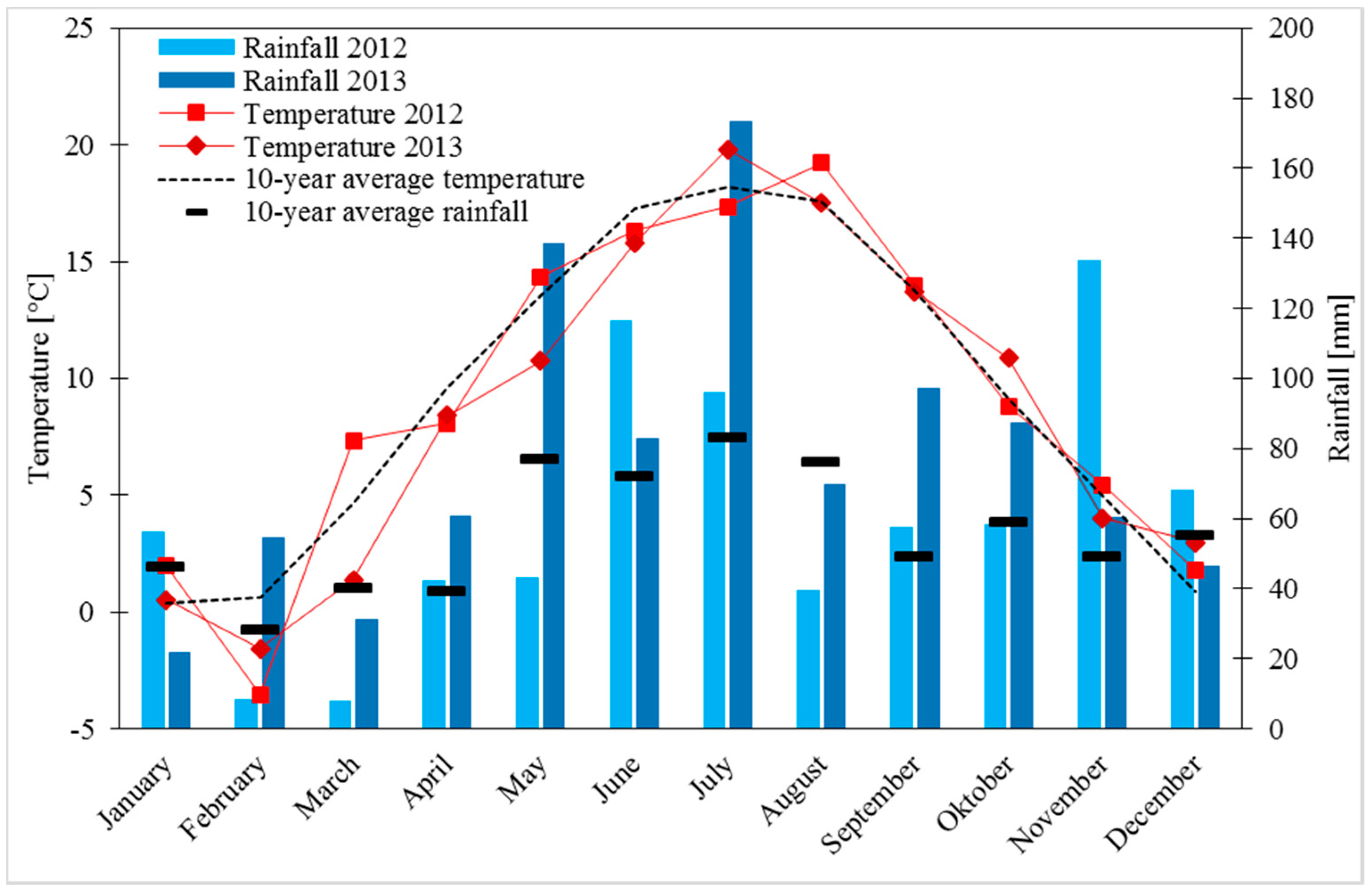

The data for the LCA were collected from a randomized split-block field trial, where miscanthus, switchgrass and maize were grown under ceteris paribus conditions. The field trial was started in 2002 and allows a comparison of annual and perennial crops. Samples and yield measurements for this LCA were taken in 2012 and 2013 and laboratory analyses were performed to estimate biogas and methane yield and biomass quality.

3. Results

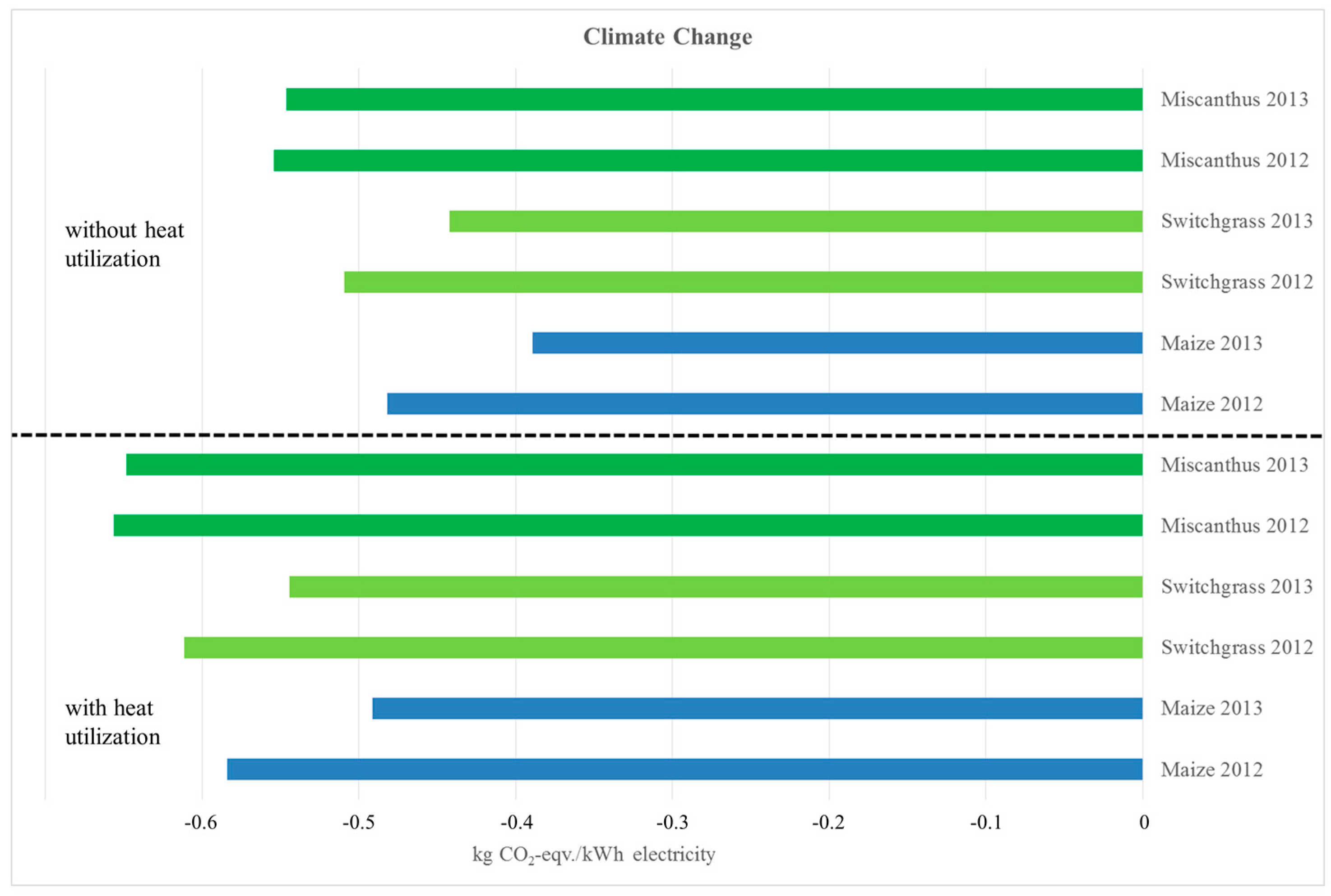

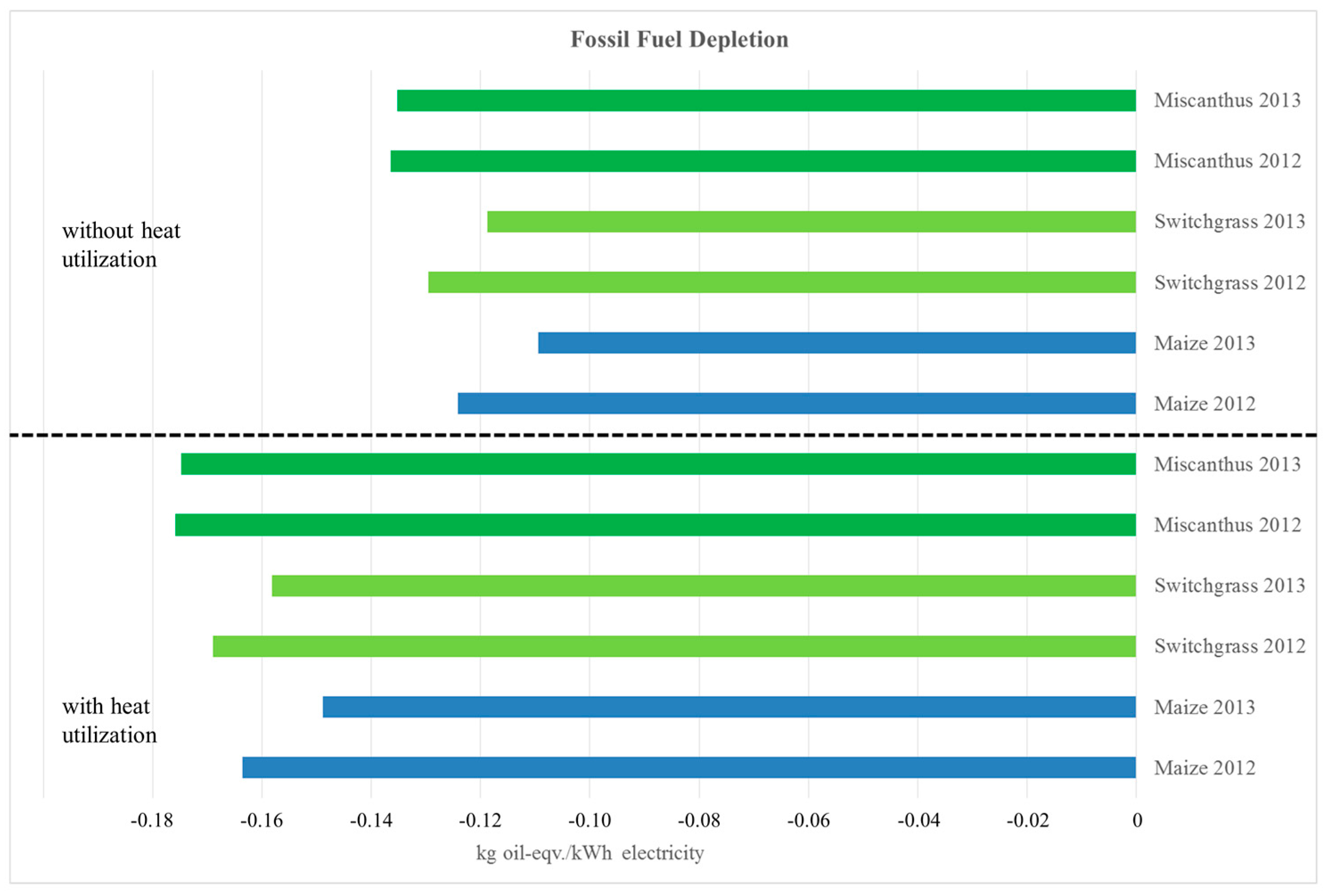

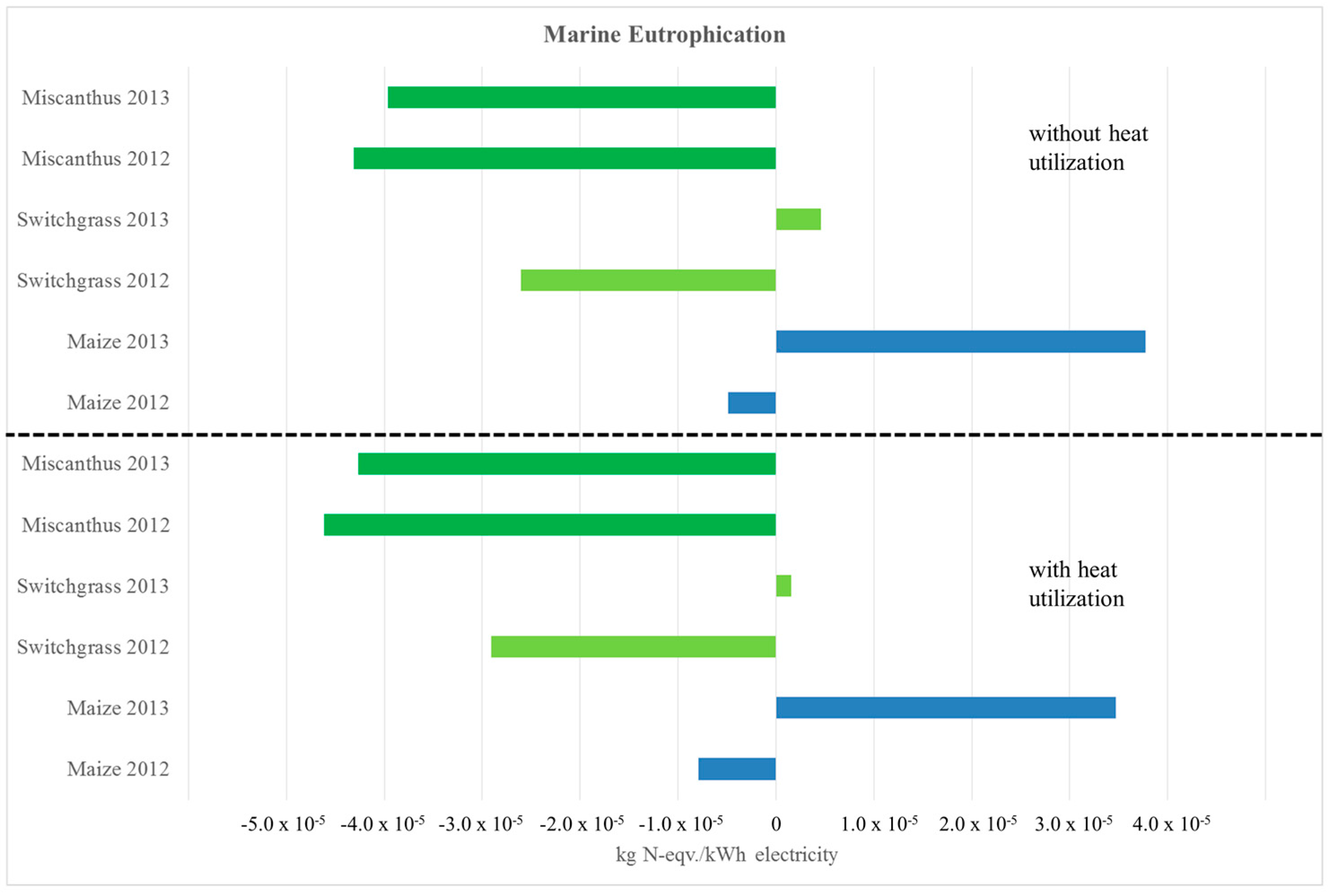

For each impact category analyzed, data are shown for the two climatically different production years 2012 and 2013 (2012 favorable and 2013 non-favorable for silage maize cultivation) and for two scenarios, one with and one without heat utilization. These are presented both in figures and in tables, depicting the results with (figures) and without (tables) a system expansion approach. The results are presented per functional unit (FU), which is kWh electricity. In the

supplementary material (S1–S5), the same results are presented per kg dry biomass.

The value in each impact category shows the net impact or benefit of the substitution of the fossil reference through a biobased alternative. In this study, the German electricity mix was substituted by power generated through the fermentation of dedicated energy crops and the subsequent combustion of the biogas in a CHP unit. A negative value in this case is thus a net benefit while a positive value is a negative impact on the environment.

In contrast, the table shows the environmental impact of the generation of 1 kWhel. in each impact category without this substitution, separated into the main emission sources. In this context, the recycling of nutrients represents the emission savings associated with the reduction in fertilizer in other crops through the use of the fermentation residues. The agricultural management summarizes all operation steps from soil preparation, planting, mulching, fertilizing, and spraying of herbicides to recultivation. The fertilizer-induced emissions are emissions associated with the use of fertilizers, such as N2O emissions, which occur after the application of nitrogen fertilizer. Credits heat utilization are credits given for the substitution of heat produced via a fossil reference (in the present study natural gas) by heat generated via the combustion of biogas in the CHP unit. In the heat utilization scenario, 20% of the heat produced is used internally in the biogas plant. Of the remaining 80%, one half (40% of total heat produced) is used to heat nearby buildings, thus substituting heat from conventional sources.

3.1. Climate Change and Fossil Fuel Depletion

The production and use of the analyzed C4 crops, both perennial and annual, leads to a net GHG emission reduction up to 0.66 kg·CO

2-eqv. (kWh

el.)

−1 through the substitution of a fossil reference (

Figure 3). Furthermore, all scenarios show a net decrease of the fossil fuel depletion of up to 0.18 kg·oil-eqv. (kWh

el.)

−1 (

Figure 4). As expected, the scenarios with heat utilization lead to both higher GHG emission and fossil fuel saving (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). On average, miscanthus shows the highest GHG emission and fossil fuels saving potentials. Both perennial grasses perform better than maize (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The advantage of miscanthus over switchgrass is larger than the advantage of switchgrass over maize.

Table 4 shows the contribution of different processes to the GHG emissions and

Table 5 the use of fossil fuels in these processes. The production of nitrogen fertilizer is responsible for the largest impact in both impact categories and for all crops. This is also the reason for the high credit—in terms of fossil energy savings—given for the recycling of nutrients from the fermentation residues (

Table 5). Other processes with high impacts on GHG emissions and fossil energy consumption are harvest operation and biomass transport to the biogas plant (

Table 4 and

Table 5).

3.2. Freshwater Eutrophication and Marine Eutrophication

The substitution of the fossil reference lead to a net increase in freshwater eutrophication of up to 3.5 × 10

−5 kg·P-eqv. (kWh

el.)

−1 in all scenarios (

Figure 5). On average, the freshwater eutrophication potentials are lowest for miscanthus, followed by switchgrass and then maize (

Figure 5).

The recycling of nutrients leads to a high credit, which has a positive impact on the freshwater eutrophication (

Table 6). In all scenarios, fertilizer-induced emissions account for the largest share of freshwater eutrophication. These are phosphate emissions associated with the use of phosphorus fertilizer, which are highest in maize and lowest in miscanthus (

Table 6). The second-largest share comes from nitrogen fertilizer production, followed by the production of phosphate fertilizers (

Table 6).

A net benefit in the impact category marine eutrophication was achieved for the utilization of switchgrass and maize only in the year 2012—where the yield was significantly higher than in 2013—and when the heat utilization was accounted for (

Figure 6). Miscanthus was the only crop that led to a reduction of marine eutrophication in comparison to the fossil reference in all years and scenarios. The maximum reduction was—4.6 × 10

−5 kg·N-eqv. (kWh

el.)

−1 (

Figure 6).

The production of nitrogen fertilizer had the strongest impact on marine eutrophication for all crops, followed by fertilizer-induced emissions. Ammonia emissions and nitrate leaching due to the use of nitrogen fertilizer play a particularly important role here. Both impacts were highest for maize and lowest for miscanthus (

Table 7). The recycling of nutrients results in a significant credit (

Table 7).

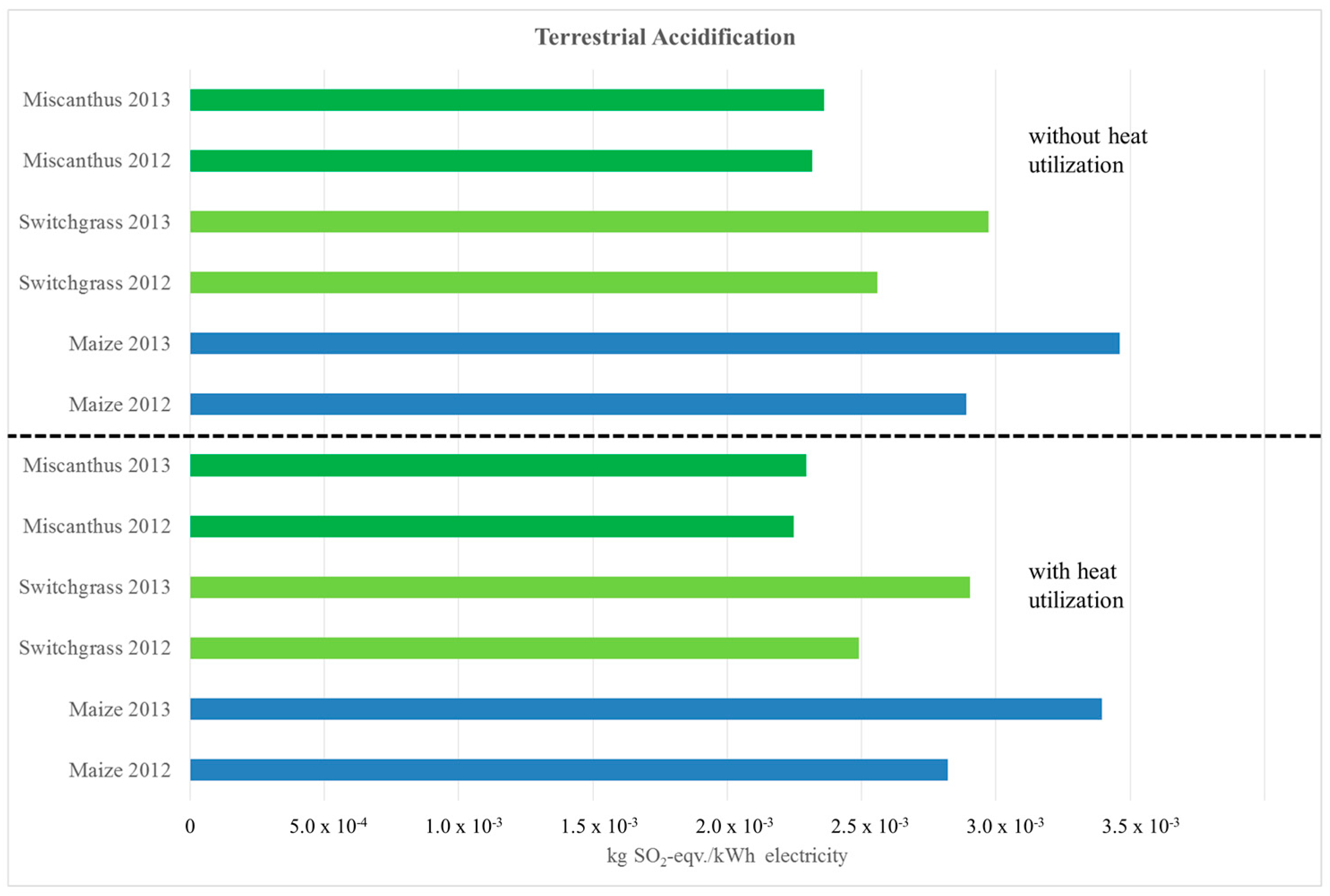

3.3. Terrestrial Acidification

All scenarios led to higher terrestrial acidification than the fossil references. Maize without heat utilization performed worst and led to emissions of 3.5 × 10

−3 kg·SO

2-eqv. (kWh

el.)

−1 (

Figure 7). Miscanthus performed best with the lowest terrestrial acidification potential (

Figure 7).

Fertilizer-induced emissions—especially ammonia—had the highest impact on terrestrial acidification for all crops and accounted on an average for around 20% of total emissions (

Table 8). The second largest source of emissions responsible for terrestrial acidification was production of nitrogen fertilizer, followed by transport of the biomass (

Table 8).

4. Discussion

Here the results of this study are considered in a broader context, also including other environmental aspects not modeled in the LCA. The discussion concludes with opportunities and challenges of the introduction of novel perennial C4 crops in the biogas sector.

4.1. Environmental Performance in Impact Categories Modelled in the LCA

The results of this study show that, as soon as more impact categories are assessed than climate change and fossil fuel depletion, the environmental performance of the bioenergy conversion route “biogas” is not so clear-cut. All three energy crops have a significantly better environmental profile than the fossil reference (German electricity mix) in the impact categories climate change (CC) and fossil fuel depletion (FFD). Similar findings have been reported in the literature [

45,

46]. However, all three energy crops showed significantly higher impacts than the fossil reference in the impact categories freshwater eutrophication (FE) and terrestrial acidification (TA). The results for marine eutrophication (ME) were more variable. Here, miscanthus (both years) and switchgrass (2012 only) had a significantly lower impact than the fossil reference, whereas maize had a significantly higher impact in 2013 due to the low yield. High biomass yields have been shown to be a crucial factor for favorable environmental performance [

47]. Again, these results correspond to findings of other studies, which mainly also found a higher impact of energy-crop-derived biogas than the fossil reference in acidification and eutrophication potential [

48,

49,

50].

4.1.1. Overall Impact of Process Steps in Impact Categories

The production of nitrogen fertilizer was identified as the most relevant process step in the impact categories FFD and CC and the second most relevant in ME. Fertilizer-induced emissions were identified as the most important flow in the categories FE and ME and second most important in CC and TA. Similar results have been reported in the literature and numerous studies have already described the strong impact of nitrogen fertilizer production and related direct and indirect emissions on FFD and CC (e.g., [

39,

46,

50,

51]). The present study also showed a strong impact of mineral nitrogen fertilizer application on eutrophication (FE and ME) and acidification potential of crop production. This seems logical, since nitrate is one of the major contributors to eutrophication and the nitrification process a major contributor to soil acidification [

27].

In TA, direct CHP emissions were the most important flow. Rehl et al. [

49] identified sulfur dioxide from the CHP as one of the most important contributors to the acidification potential. One possibility to reduce these emissions could be the upgrading of biogas to biomethane, because sulfur dioxide is almost completely removed during this process. In addition, new techniques for biomethane production (e.g., pressurized anaerobic digestion) could help reduce the carbon footprint of biomethane production in the near future, because the demand for energy-intensive compression is reduced in such approaches [

52]. Lijó et al. [

53] reported production of nitrogen fertilizer, fertilizer-induced emissions and emissions of agricultural management as important factors for the environmental performance of energy crops. In this study, emissions from agricultural management were found to be the third most relevant process in CC, FFD and ME for maize cultivation, but considerably less important for miscanthus and switchgrass.

4.1.2. Impact of the Process Steps for Each Crop

Emissions and fossil fuel depletion from production of nitrogen fertilizer and agricultural management and fertilizer-induced emissions were highest for maize in each of the considered impact categories. This is because maize production consumes more energy for soil cultivation and requires higher nitrogen fertilizer levels for high yields than the C4 perennial grasses. For maize, data from the treatment with the highest nitrogen fertilization (240 kg·N·ha

−1) were used, which on long-term average yielded significantly higher than the medium fertilization rate (120 kg·N·ha

−1). However, the high nitrogen fertilization is probably above the marginal revenue and a lower fertilization rate could reduce the environmental impact of maize. Nevertheless, the nitrogen demand of miscanthus and switchgrass are still lower than that of maize. In addition, for miscanthus and switchgrass, data from the treatment with the highest nitrogen fertilization rate (80 kg·N·ha

-1) were used, in order to consider the higher nutrient removal by the green harvested biomass. Although green harvest increases the withdrawal of nitrogen compared to a spring harvest, the biomass of miscanthus and switchgrass contained approximately 60% less nitrogen than maize biomass (

Table 3).

The annual cultivation of maize led also to significantly higher emissions and fossil fuel depletion for agricultural management in CC, ME and FFD. For this reasons, changing the crop production system from annual crops with a high nitrogen demand to perennial C4 crops with improved nutrient efficiency seems to be a very promising option for increasing the environmental sustainability of the biogas sector and the bioeconomy, as already described by Lewandowski [

54]. Compared to maize, miscanthus and switchgrass showed in the scenarios without heat utilization 59%–73% and 25%–28% lower CC potential, 68%–79% and 28%–30% lower FFD potential, 57%–69% and 25%–28% lower FE potential, 53%–67% and 29% lower ME potential and 16%–26% and 9%–12% lower TA potential, respectively.

Considering all impact categories, miscanthus performed best amongst the three assessed crops. Especially in 2013, the yield and thereby the environmental performance of miscanthus was much more stable compared to maize and switchgrass. Both crops reacted more sensitively to the unfavorable weather conditions in 2013. This resulted in lower yields and is also reflected by the performance in the environmental impact categories. The higher stress tolerance and yield stability of miscanthus is therefore not only favorable for the farmer, but also from an environmental point of view.

The nutrient recycling via fermentation residues led to a significant credit for all crops, especially in the impact categories CC, FFD and ME. However, fermentation residue application on the perennial grasses miscanthus and switchgrass and resulting emissions need to be further investigated. Since the fermentation residues cannot be incorporated into the soil in such perennials, higher ammonia emissions could occur, which could lead to higher eutrophication and acidification potentials [

48]. This needs to be further investigated to allow consideration of such an effect in future assessments of the environmental performance.

4.2. Other Environmental Aspects

In the section above, the environmental performance was analyzed in five impact categories and it was shown that the perennial grasses, especially miscanthus, performed better than the annual crop maize. However, the five considered impact categories are not sufficient for a holistic assessment of the environmental performance. Therefore, other aspects relevant to environmental performance are discussed in the following section.

Intensive soil cultivation in annual maize is accompanied by an increased risk of soil erosion, due to the slow youth development of the crop [

6]. For annual maize, there is also a low to medium risk for soil compaction [

55]. However, for green-harvested miscanthus and switchgrass the risk of soil compaction may be lower due to its perennial nature, but needs to be assessed to allow comparison. The combination of intensive soil cultivation and low amount of crop residues in silage maize has a negative impact on content of soil organic carbon. Both environmental aspects could be improved by changing substrate supply of biogas plants from maize to perennial C4 grasses, since miscanthus and switchgrass generally lead to an increase in soil organic carbon compared to annual cropping systems [

11,

56,

57]. Under miscanthus, the largest proportion of the soil organic carbon is found in the topsoil, which can be explained by the high proportion of roots in the top 0.35 m [

58]. The sequestration of carbon in the soil can increase the GHG mitigation potential significantly, especially if the cropping system is changed from annual to perennial [

56,

59]. In this study, the sequestration effect was not considered, because the effect of the green harvest on the root and rhizome development and on the soil carbon sequestration potential is not yet known. Therefore, the development of the soil organic carbon under green harvested miscanthus and switchgrass needs to be further investigated to determine the sequestration potential of this harvest regime.

Agricultural land occupation is another important environmental aspect, due to limited expansion potential for agricultural land and negative impacts from the transformation of natural land. In this paper, agricultural land occupation was not directly assessed, but the data in

Table 1 show that maize required the smallest area (173 ha) of agricultural land in 2012 to supply the biogas plant with the required biomass. Changing the input substrate from maize to miscanthus or switchgrass increased the agricultural land demand in 2012 by 12% or 68%, respectively. Under unfavorable weather conditions in 2013, the agricultural land demand for miscanthus cropping was 20% lower and for switchgrass 73% higher than for maize cultivation. Agricultural land occupation for biogas production can lead to indirect land-use change (iLUC), which can significantly reduce the GHG mitigation potential and even lead to higher GWP than the fossil reference [

14]. For this reason, the comparatively high agricultural land demand of switchgrass to deliver the required biomass substrate is a clear disadvantage compared to the other crops. In contrast, the area demand of miscanthus was only slightly higher and even lower when unfavorable weather conditions occurred for maize production. Again, the higher abiotic stress tolerance and yield stability of miscanthus can be seen as environmental advantage. However, both perennial C4 crops could be grown in future mainly on marginal or contaminated land [

9,

23]. This could reduce the pressure on agricultural land and expand the area available for biomass production.

Biodiversity is difficult to assess just by the crop itself, because it strongly depends on other factors, e.g., the distribution of fields in a landscape and structural elements such as hedges. However, modern agriculture is assumed to have a negative impact on the biodiversity by simplification of agricultural landscapes, e.g., large field sizes, and small amount of crop varieties which are grown in monoculture [

4]. An increased number of crop species and a higher proportion of perennial cropping systems in modern agriculture is seen as one option to promote biodiversity [

4]. For this reason, replacing biogas maize with miscanthus or switchgrass could positively affect the biodiversity by adding novel, perennial crops to the agricultural landscapes. However, it should be noted that the impact on soil biodiversity may be influenced by the choice of the perennial biomass crop [

60]. Furthermore, both perennials can be characterized by their comparatively low-input crop management, after their successful establishment in year one. For miscanthus, a higher abundance of insects, spiders and earthworms than in arable land is reported, as well as additional niches for birds and, provided a spring harvest is performed, over winter cover for small mammals in intensive arable regions [

11,

61]. For switchgrass, similar positive effects can be expected, which leads to the assumption, that both could increase the biodiversity and structure-richness of agricultural landscapes. Again, the effect of the pre-winter harvest, which clearly removes the winter cover for small mammals and reduces the mulch layer, is not yet known and needs to be investigated. However, both crops also induce risks for biodiversity because they are not native to Europe and could potentially appear as invasive species.

Miscanthus x giganteus has a very low invasiveness risk, because it does not produce fertile seeds and no escapes were observed over more than two decades of

M. x giganteus production in Europe. Current miscanthus breeding efforts aim to produce fertile genotypes that can be propagated by seeds [

10], but several mechanisms to avoid seed escape are incorporated, including preferring candidates which require a very long vegetation period for seed production to avoid viable seeds being produced in regions of biomass cultivation [

9]. It is also necessary to mention that miscanthus as well as switchgrass seedlings have a very low competitiveness compared to weeds and a slow youth development. For this reason it is quite unlikely that they become invasive species in Europe. Nonetheless, the invasiveness potential of novel miscanthus genotypes and switchgrass needs to be investigated and monitored.

Finally, the socioeconomic aspects of landscape appearance need to be considered. Crops such as maize are often criticized in the public, due to their height and monotony. The same could appear for miscanthus, due to its height and density in well-established commercial fields. Smaller and nicely flowering miscanthus genotypes or switchgrass could be experienced more favorably and might influence the appearance of landscapes more positively. However, this could compromise the yield and lead to a trade-off between yield and public acceptance. Public acceptance could also be positively influenced by using smaller fields or strip cropping instead large monoculture fields.

4.3. Implementation—Chances and Challenges

In this study, it is shown that implementation of perennial C4 grasses for biogas production can have significant environmental benefits. From an environmental point of view, miscanthus in particular would be a desirable crop for biogas production. The main weak point of switchgrass is clearly its lower yield potential than miscanthus and related to that its higher area demand, fossil fuel consumption and emissions. For the farmer, the implementation of miscanthus and switchgrass as biogas crops is accompanied by opportunities and challenges, which are discussed in the following section but require further research.

This study is based on methane yields measured in a batch test using milled biomass. In order to transfer these values to a full-scale biogas plant, a pre-treatment of the biomass was considered for miscanthus and switchgrass, which leads to a higher electricity demand for plant operation. For this reason, the electricity demand for miscanthus and switchgrass was assumed to be almost twice as high as that for maize. Before implementation, the methane yield, the necessity of a pre-treatment and the energy consumption of such a pre-treatment should be verified under more realistic conditions. Ensiling of miscanthus biomass, and presumably also switchgrass, appears possible [

19], but also needs to be demonstrated in practice.

The long-term performance of green-harvested miscanthus is one of the major uncertainties for its biogas utilization, because miscanthus reacts sensitively to very early mid-season harvest, but tolerates green harvest in late autumn [

18]. However, it is not yet known if green-harvested miscanthus is productive for as long as a spring-harvested crop (more than 20 years) and if recycling of fermentation residues is sufficient to maintain its productivity. In addition, the farmer has to dedicate arable land to miscanthus for several years to achieve return on investment, due to the high establishment costs. However, current research focuses on reducing establishment costs by developing seed-based genotypes, which may allow direct sowing in future [

10]. Further, most biogas plants are designed for a minimum of 20 years’ operation, which would fit in very well with the expected productive lifetime of miscanthus. Cost-effective miscanthus establishment offers the chance of significantly reducing biomass costs. As shown in this paper, the yield of miscanthus is not as sensitive as annual maize to unfavorable weather conditions, which may become more common in future due to climate change. One of the main reasons for the low maize yield was the very late sowing date and the early summer drought stress. In miscanthus, planting is only required once in 20–30 years and the established crop benefits from winter soil moisture. Therefore, miscanthus seems very suitable for risk mitigation of such weather conditions.

In contrast to miscanthus, switchgrass can be established cheaply via direct sowing of seeds. However, the establishment of switchgrass is difficult due to an often low germination rate, low competitiveness of seedlings and limited availability of herbicides. Current research focuses on the optimization of the establishment method and herbicide testing [

62]. Nevertheless, early green harvest of switchgrass seems less problematic than in miscanthus and even a double cut is possible [

21]. The shorter productive life of approximately 15 years, lower investment costs and the ability of direct sowing may increase farmers’ willingness to adopt this crop. However, the lower yield potential limits its implementation to very poor and shallow soils, where it is likely to perform better than miscanthus [

23].

From an environmental point of view, miscanthus cultivation for biogas production is generally recommended if the biogas plant technology is suitable for the digestion of fibrous substrates or adequate pre-treatment options are available.