1. Introduction

Achieving sustainable urban development in Australia’s major cities that are projected to double in population over the next forty years will not be possible under strategic metropolitan plans that continue to permit more than half of all new housing to be built in greenfield locations on the periphery of these cities. This level of metropolitan growth is unprecedented and calls for more radical approaches to planning and development than has characterized government strategies to date. The degree to which sustained rapid urban growth exerts positive or negative impacts on the future economic, social and environmental performance of Australia’s cities clearly depends on how well they are planned for. A rapid succession of metropolitan plans and reviews of plans for the major capitals (e.g., Melbourne: Melbourne 2030 (2002), Melbourne 2030 Audit Report (2008), Melbourne @ 5 Million (2008), Plan Melbourne (2014), Plan Melbourne Refresh (2015) and Plan Melbourne 2017–2050 (2017)—see [

1] for more details) is evidence that previous strategies for future city development have fallen short of expectation.

The current challenges for metropolitan spatial planning in accommodating rapid growth are substantial, and include:

The negative consequences of low-density sprawl are well established and involve economic and environmental performance in addition to the social consequences identified above. The economic cost of providing new physical infrastructures to greenfield development has been estimated as two to three times that for redevelopment in established areas [

10,

11]. Outer suburban residents in cities such as Melbourne also drive over 60% more kilometers per household as driver or passenger compared with inner city residents—a growing time and productivity impost for both the household and metropolitan economy [

12]. Environmental costs of continued urban sprawl are considerable. While Australia’s major cities have been designated among the most livable in the world, they have been demonstrated to be currently among the least sustainable.

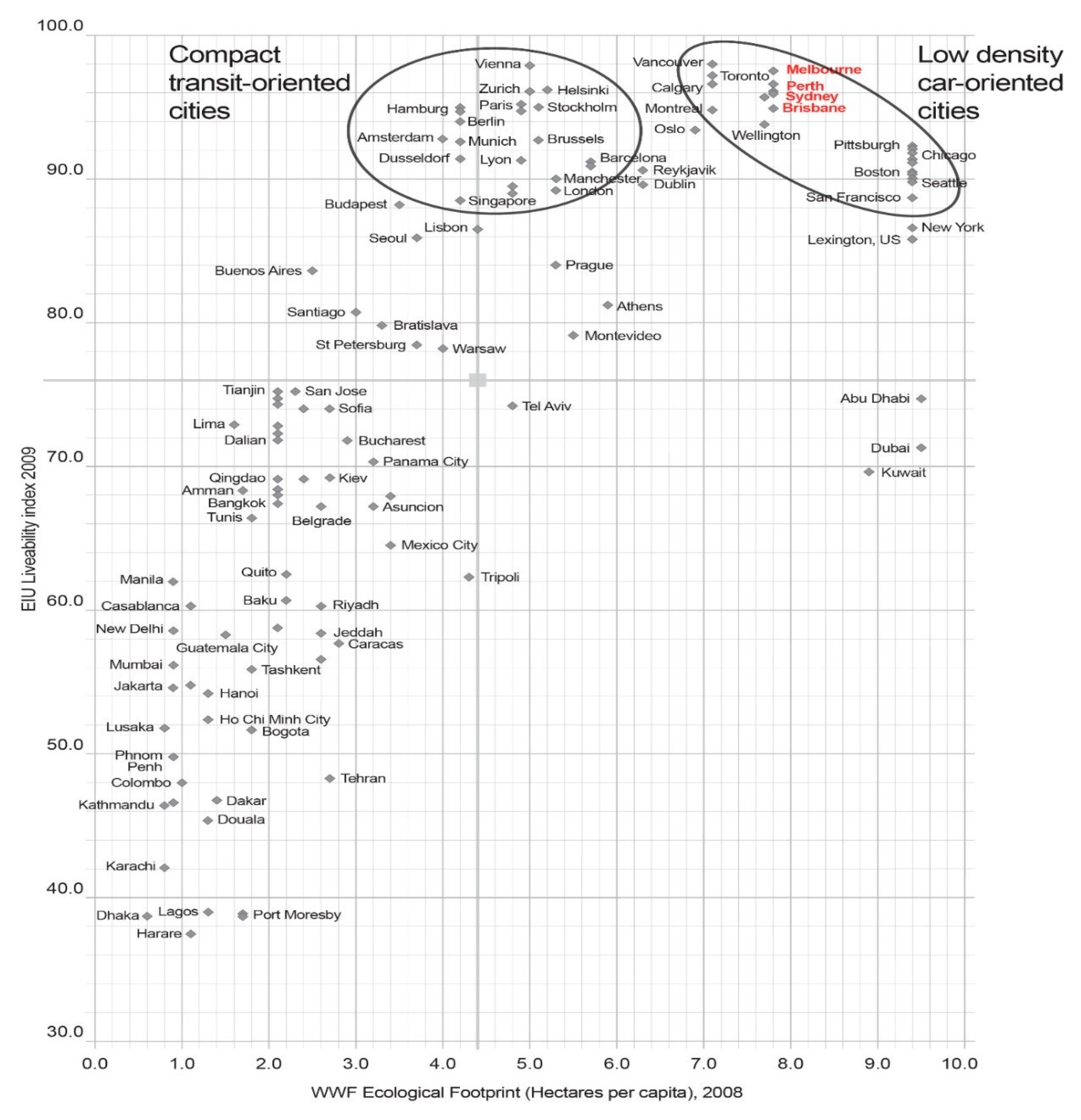

Figure 1 illustrates this clearly, where the vertical axis maps livability across 140 cities based on the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Livability Index and the horizontal axis represents an estimate of their ecological footprints that encompass both resource use and carbon emissions [

13,

14]. The urban footprint of Australian cities has also been identified as a major concern in the latest national State of Environment report [

15], highlighting the continued loss of productive agricultural land on the peri-urban fringe to greenfield development—reducing an important source of fresh produce close to the city, increasing food miles and carbon footprints.

Faced with these challenges, critical and inter-related transitions are required in Australia’s major cities. These include:

transition to more compact cities—from a low-density suburban city form to an urban form and fabric, more characteristic of European cities that deliver urban livability more sustainably than those in Australia and North America as a result of their smaller sized and higher density housing and more active forms of transport [

16].

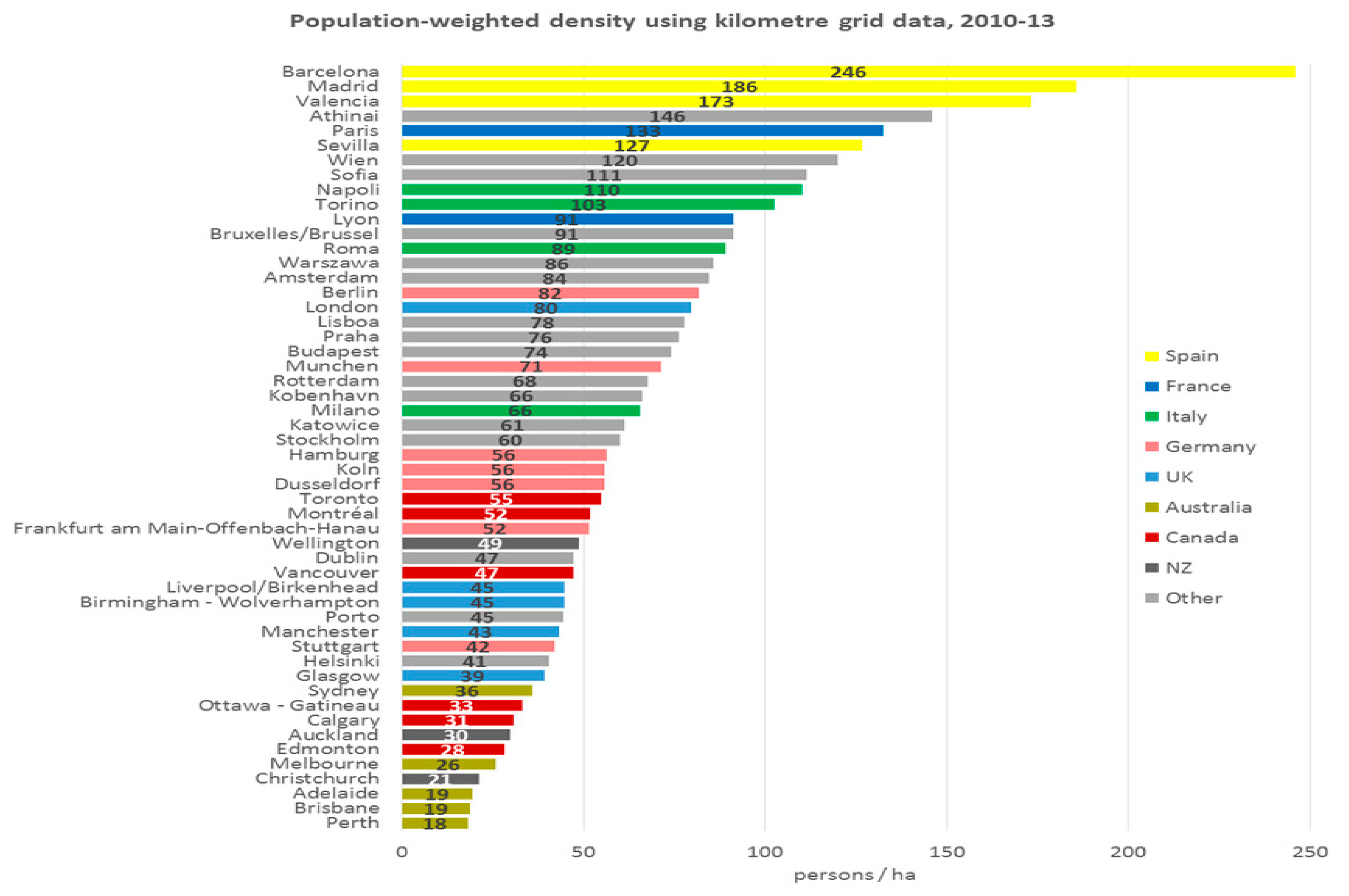

Figure 2 clearly indicates the scale of change required. Sydney is Australia’s most densely populated city at 36 persons/ha—twice that of Perth; and at 26 persons/ha Melbourne is half that of Vancouver and one fifth the density of Vienna (with equivalent levels of livability). Most North American cities share a similar urban form and density with those in Australia, but there are countervailing trends emerging in the USA: four fifths of large metro areas have become more suburban since 2010 while one fifth have become more dense (e.g., Seattle, Chicago, Washington, Boston, NY, Philadelphia, Portland [

17]. In comparison, Australia’s capital cities have begun densifying over this period, especially in their established areas [

18,

19].

transition in type and scale of urban housing redevelopment. Infill needs to assume a dominant role in increasing the supply of medium-density housing—the “missing middle”—in the established middle ring low-density suburbs—and at a scale of redevelopment beyond that of knock-down-rebuild [

20].

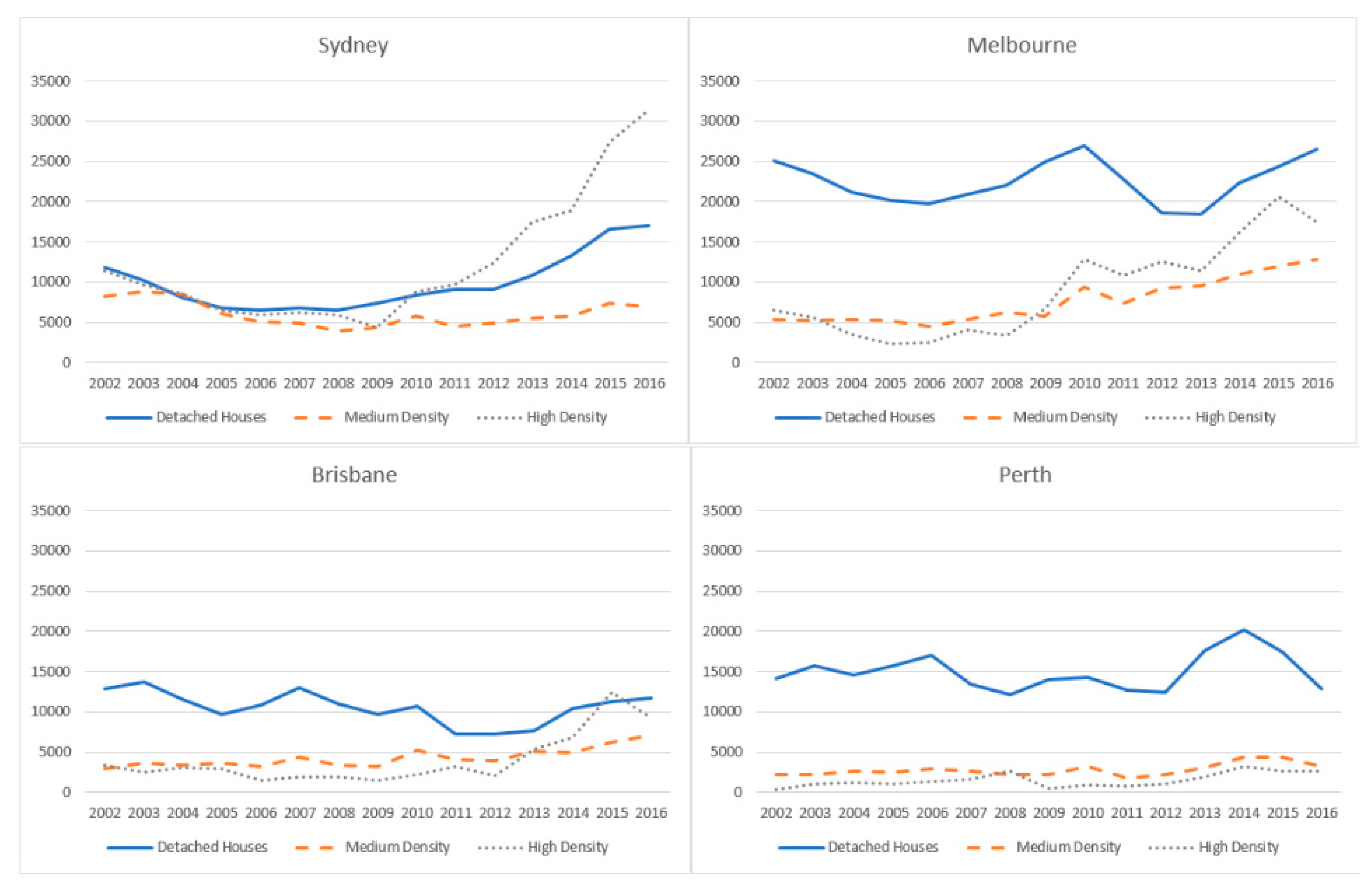

Table 1 illustrates the dominance of single-story detached dwellings in Australian capital cities but points to a shift beginning to occur in the supply of higher density housing.

transition to more sustainable (steady state, no net adverse environmental impact), regenerative (eco-positive, restorative) built environments linked to precinct-scale residential infill and densification, taking advantage of new distributed/decentralized technologies related to energy and water infrastructures, alternative mobility/travel platforms and waste management systems.

Infill is now a key concept in metropolitan planning and development designed to redirect new housing and population inwards rather than outwards. Australia’s five largest capital cities have infill targets ranging from 47% in Perth to 85% in Adelaide, with Sydney and Melbourne at 70%, but infill is a blanket term that obscures important outcomes that need to be distinguished in relation to the scale at which it occurs—parcel or precinct—and in terms of the urban arena in which it takes place—brownfields or greyfields [

22]. Different development models are required for each configuration.

Having identified the multiple challenges confronting 21st century urban development in Australia, we proceed to a following set of three Sections that explore the prospect for urban transition.

Section 2 outlines transitions required for a regenerative retrofitting of the established suburbs of its major cities, with particular focus on the greyfields where a majority of property with high redevelopment potential is located: the ageing, occupied middle ring suburbs. Here we outline a new focus for urban development policy and practice—greyfield precinct regeneration—and introduce the four stakeholder groups involved in the transition management process: state government, local government, the property development sector and community residents. The challenge involves accelerating and scaling up precinct-scale greyfield residential renewal into a broader based urban transition process. It is at this stage where a gap appears in transition theory and transition management (TM) models capable of guiding innovations into the urban mainstream. Transformative capacity is that gap. Transformative capacity is examined in

Section 3 as it relates to the four principal stakeholder groups involved in a suburban to urban transition (neighborhood density change) and a housing transition (from detached to medium-density housing). The final section of the paper assesses the current capacity of urban residents in the greyfields to embrace the need for neighborhood change and housing change; and in particular, the potential for citizen-led precinct redevelopment. This is informed by a major survey of housing and locational preferences of residents in Melbourne and Sydney greyfield suburbs undertaken in September 2016.

2. Background: Need for a New Development Model for Urban Regeneration in Greyfield Suburbs

Brownfields are internationally recognized as a focus for urban redevelopment, and in Australia well-accepted development models have operated since the 1990s—almost exclusively at a precinct level [

22,

23]. They are typically found in well located areas of cities that have been associated with an earlier era of economic activity (e.g., old docklands, manufacturing and abandoned retailing sites); are owned by a single party, usually government or industry; of a scale which is closer to that provided by greenfield sites for development; contaminated to some degree, depending upon the nature of prior use; and typically unoccupied, obviating the need for community engagement at a level required of greyfields.

Greyfields are markedly different. They are much more extensive and lie predominantly between the central business district and inner city housing markets and the more recently developed greenfield suburbs. Their location provides superior access to employment, public transport and services than the latter zone; and they have demonstrably higher amenity and livability. Greyfields in the Australian context have been defined as those ageing but occupied tracts of low-density suburbia that are physically, technologically and environmentally failing and where value resides in the land (generally >70%; which we label as having “high redevelopment potential”) rather than the building—representing a vastly under-capitalized real estate asset [

24].

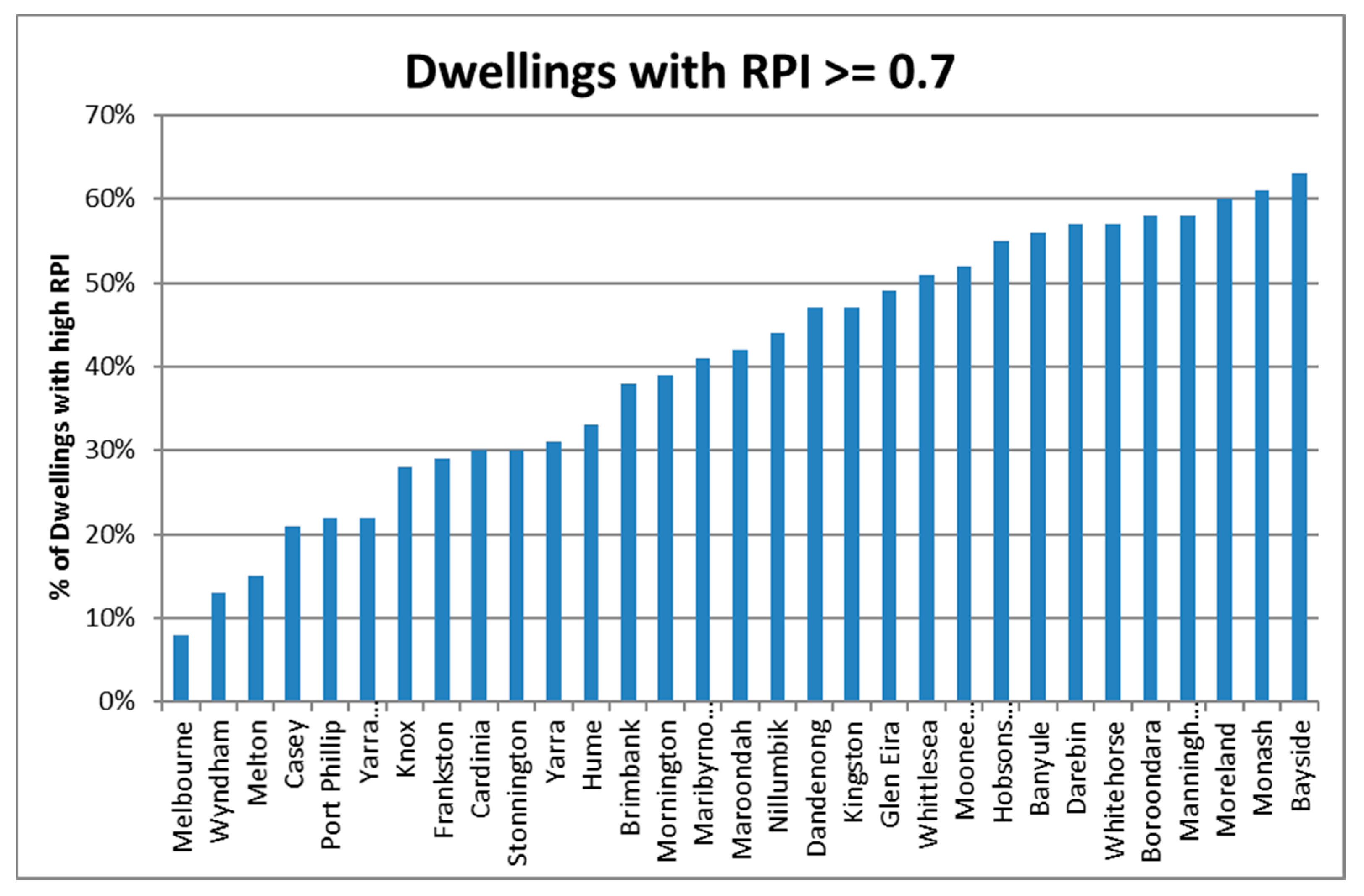

There is a significant volume of greyfield residential property in Australian cities, estimated at over three quarter of a million dwellings for Melbourne and concentrated primarily in the middle ring suburbs [

25].

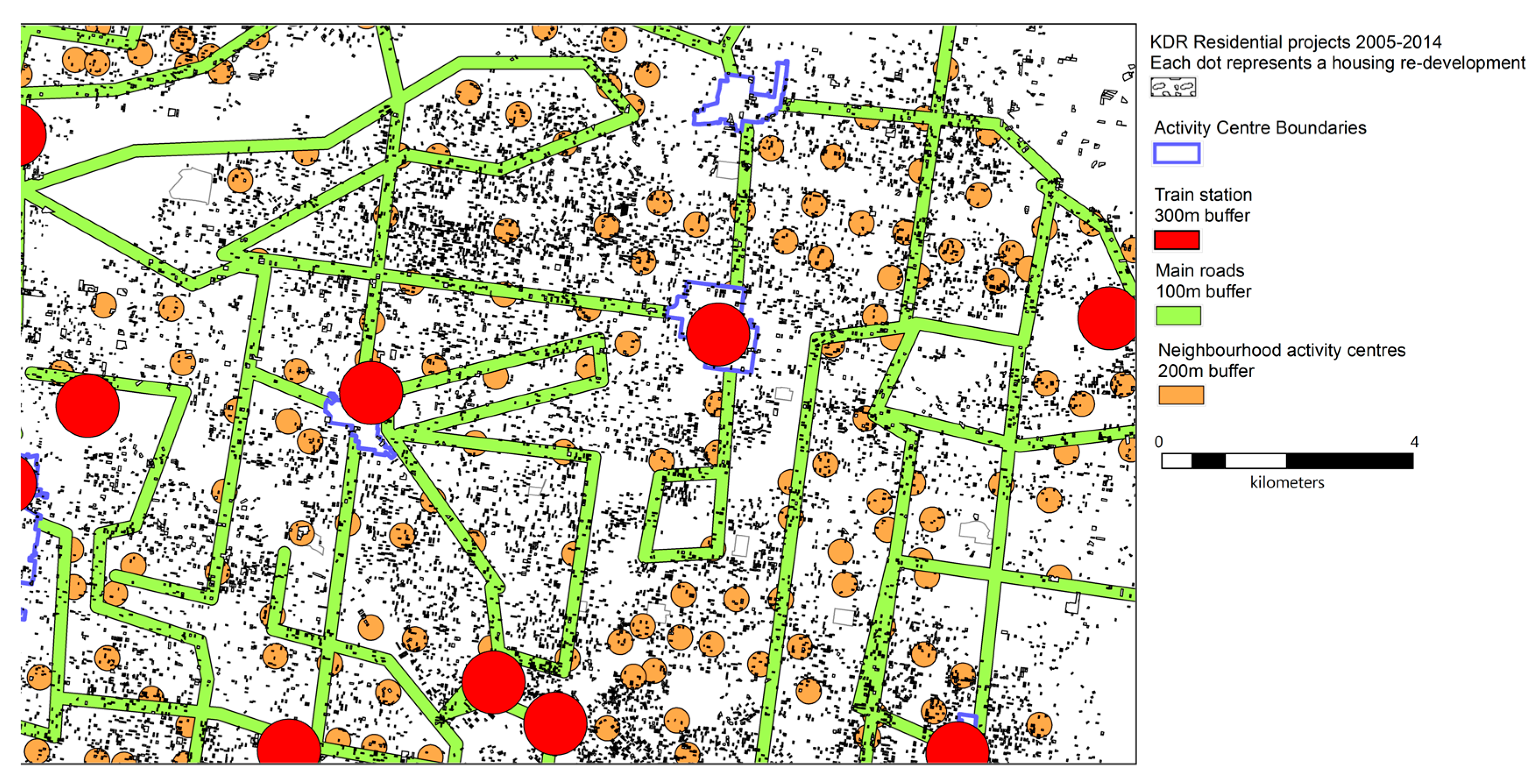

Figure 3 reveals that at least one third of Melbourne’s local government areas have a majority of their residential properties where more than 70% of value is in the land. However, most of these municipalities are restrictively zoned in a manner that, to date, precludes more intensive forms of redevelopment, much less regeneration and reactivation. In a recent audit of infill redevelopment in Melbourne, Newton and Glackin [

20,

26] found that greenfield development still represented approximately 50% of net new dwelling construction; brownfields were contributing around 25%, predominantly via high-rise apartments; and the greyfields the remaining 25%. Here, almost half were “knock-down-rebuild” (KDR) where detached housing is demolished and replaced by one larger dwelling or between 2 to 4 townhouses—dwelling types that can be accommodated within existing planning and building regulations. Less than 15% is medium density. It represents the “missing middle” of Australia’s housing stock. Most greyfield housing redevelopment is also located outside of the designated zones where state and local governments are seeking higher density forms of residential redevelopment: along major transport arterials, near railway stations and within a range of activity centers—the Residential Growth Zones (

Figure 4).

Those key features of recent strategic metropolitan plans that focus primarily on intensification of development in designated activity centers and transport corridors are necessary but are demonstrably not sufficient to: halt sprawl, achieve infill targets and result in a regenerative development of Australia’s largest cities. Significant piecemeal KDR is occurring in the two major residential zones (Neighborhood Residential Zone and General Residential Zone) as sub-optimal development. It is not: providing an adequate yield of new housing, nor variety in dwelling types required of current and emerging socio-demographics; reducing traffic congestion in the middle suburbs (rather, is significantly adding to it, with considerable space continuing to be devoted to accommodating cars on site, even when redevelopment is close to public transport); maintaining green space, with almost wholesale loss of private gardens and established trees associated with KDR. Moreover, it is not regenerative. There is a limit to the extent to which redevelopment of individual buildings can be eco-positive for energy, water, transport and waste management.

There is now increasing recognition that new urban development models are needed to better align a city’s built environment with its future population by better managing the land available for development; especially in established built up areas where pressure for re-development is strong [

23,

24] This is increasingly the case in fast-growing cities, where it is argued that poor land use planning and regulation is creating a scarcity of land in particular locations, inhibiting their capacity to accommodate growth in a manner that is environmentally sustainable, economically efficient and socially equitable [

26].

Australia’s cities have, for the most part, been built as precincts and according to some broader plan, as distinct from collections of buildings. They have also reflected the prevailing economy, technology, industry capacity, design thinking and lifestyles of the era. The era in which most of Australia’s pre-war (2) built environment was laid down witnessed better co-ordination in city planning between land use and public transport, resulting in better connection between housing and jobs and services. The resultant urban forms (i.e., the “transit city”) are artifacts of this earlier era of city building. For the last 40 years of the 20th century, however, Australian city planning was dominated by the “American model” of low-density, car-dependent urban development (i.e., the “auto city”). By the beginning of the 21st century, the landscape of Australia’s two largest cities were characterized by these two contrasting urban fabrics. In the current era involving the re-building, re-designing and retrofitting of the greyfields—with an increasing set of exogenous and endogenous drivers to accommodate—precincts need to regain their significance as an organizing framework for urban planning and design. KDR represents a major challenge to more sustainable urban development. Creation of an alternative—precinct-scale—property development model for urban regeneration in the greyfields is required.

The model that has been proposed is greyfield precinct renewal (GPR), and is at the heart of a ten year Greening the Greyfields (GtG;

http://infrastructuremagazine.com.au/2017/03/20/greening-the-greyfields/) project. Greyfield precinct renewal delivers multiple benefits compared to KDR: added housing yield and more varied housing typologies; zero carbon energy linked to distributed renewable energy and storage; integrated stormwater and wastewater systems; recycling food waste to compost; more walkable neighborhood with fewer cars; maintaining green space and enhancing community space by re-designing and re-activating the streetscape. However, it faces multiple challenges [

27].

Greyfield Precinct Renewal (GPR) has been conceived as a new property development and process model designed to enable (a citizen led) aggregation of individual residential properties into a consolidated precinct capable of being redeveloped under a new class of zoning (GPR Zone or development overlay) that enables regenerative medium-density precinct redevelopment. GtG was initiated in 2009 as an urban transitions project—an area where there is a growing focus in planning studies [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32] that reflect the magnitude of challenges now facing cities and the transformative responses required to achieve sustainable urban development. It combines the socio-technical urban transition theories of Grin et al [

33] and Newton [

1,

13] with the transition management methods and sets of participatory processes articulated by Loorbach [

34] by which a model for change involving niche innovation is identified, examined and implemented. In the GtG project, several domains where specific innovation related to GPR was required were identified from an initial twelve month engagement with over seventy thought leaders and front-runners in a series of workshops that created the over-arching programmatic framework (see [

1,

26,

35]). It was centered on developing implementable tools, instruments and processes linked to three fundamental questions:

Where to encourage GPR. This necessitated development of multi-criteria spatial analytic tools (ENVISION) that could be used to locate contiguous residential land parcels with high redevelopment potential. These have been developed and applied at metropolitan and municipal levels in Australia and New Zealand [

36].

What to design for the precinct. Focus here is on urban designs for medium-density redevelopment that provide higher yield and are regenerative for energy, water, waste, mobility and green space [

37,

38]. Aligned to this, it was also critical to ensure that precinct designs could be assessed against performance benchmarks (beyond business as usual—BAU) by software developed specifically for this purpose [

39].

How to achieve acceptance of GPR by the four principal stakeholder groups (state and local government, property developers, community) in a liberal democratic society with 3rd party planning provisions and an increasingly volatile electorate when exposed to planning proposals for local change (NIMBYism). Here the key transition management processes involved in establishing a shadow process, engaging front-runners, networking and trialing the critical niche innovations with the key stakeholder groups, were all important for demonstrating the workability and efficacy of a GPR development in at least one municipal context—as proof of concept. This involved engagement with the property development industry in relation to economic feasibility models; community engagement in relation to future plans for neighborhood redevelopment; and state and local government in relation to changes required in planning regulations in order to enable medium-density precinct-scale neighborhood redevelopment to occur [

40,

41].

4. Contemporary Community Attitudes to Neighborhood Change, “Compact Living”, and Medium-Density Housing

This section examines the responses to a September 2016 online survey of 2000 residents living in the inner and middle (greyfield) suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne to a range of housing issues (a full description of survey, questionnaire and respondent metrics are in [

64]. The questionnaire was e-mailed to a sample of households supplied by Qualtrics, who screened the participants by age (twenty or older) and postcode (residents of inner and middle ring suburbs) to achieve a representative sample for the purposes of this study. In terms of age, plans to move, duration of residence, home ownership, household size and household composition profiles were similar. A higher proportion of Melbourne respondents lived in detached houses compared to Sydney (74% versus 60%) and household incomes were higher in Sydney compared to Melbourne—both reflective of differences established over recent census periods. Focus of the survey was on understanding trends in community attitudes towards medium-density living and neighborhood change (intensification).

In response to a question posed to those households who indicated that they were likely to move residence within the next fifteen years: “What type of dwelling would you want to live in?”

Table 2 reveals that close to 60% of residents in both Sydney and Melbourne favor a detached house and yard. In the space of thirty years (approximately one generation) there has been a significant attitude shift—towards embracing higher density forms of living.

For those households indicating a plan to move within the next fifteen years, there were a common set of differentiating social and demographic factors for both Sydney and Melbourne residents in their preferences for different typologies of housing (see

Table 3). Detached housing was favored by those aged between twenty and sixty, those owning a home with a mortgage and with other residential assets, with at least two or more members of the household in the workforce, in larger households and with children under the age of eighteen, with an expressed need for a larger dwelling and preferring a suburban location.

While there are overlapping demographics across the housing typologies, those with a stronger preference for medium density tend to be older, in smaller households, living alone or with adult children, favoring a smaller dwelling and looking to relocate within the same locality they currently live in. Those looking to move into an apartment also reveal a distinctive demographic: younger (under 30) as well as older (over 60), more likely to be currently renting, in a small single person household or living with other adults; and with a preference for inner city living and close to a park that can be used regularly.

Living arrangements extend beyond the dwelling, however, and include the neighborhood and wider (sub)urban context in which people live. Three distinctive living arrangements were explored (listed in

Table 4). Responses revealed that when locational context was combined with housing type it resulted in a significant boost in preference for medium-density housing when situated in established suburbs well served by public transport and accessible to jobs and services: 46%—equivalent to the level of preference for a separate dwelling and garden and dependent on access to a private car.

The question is whether these shifts in dwelling preference have been reflected in resident attitudes towards change in the built environments in the neighborhoods in which they live. In examining this we drew on the trans-theoretical model of behavior change [

65] that proposes people move through a series of stages in relation to modification of attitudes towards some imposed or desired change. In clinical applications of this model there is opportunity for tracking longitudinal change in the attitudes and actions of individuals. In this study, the model is being used in a cross-sectional manner in order to gauge the spectrum of current resident attitudes towards neighborhood change in their suburb and city.

Table 5 sets out the four major stages in attitude-behavior change, together with the survey questions designed to characterize households at each stage. The final “action” stage is key to the scaling up of GPR beyond KDR: where neighboring property owners agree to sell their properties as a consolidated parcel (precinct). They capture the value uplift that this generates (typically 50–100% more return than selling separately) and the developer of the precinct can employ more innovative design options to increase housing yield, return on investment and generate additional environmental and social benefits aligned to state and local government planning priorities.

Seventy one percent of the total sample of respondents (N = 1983) were “aware of neighborhood change in their locality”, a percentage that was identical for the property owners (N = 1402) who were no more or no less sensitized to local urban change than renters. For the remainder of the analyses, focus centers on the property owner group since they constitute those residents capable of driving precinct-scale citizen-initiated redevelopment.

The next stage relates to the “attitude” that the resident property owners that are aware of change actually have to that change.

Table 6 reveals a high level of consistency in response for both Sydney and Melbourne residents. Less than 10% of residents in both cities think it is a good thing, but almost 40% understand that it has to happen and just over 10% are neutral. Preference for less or no change sits around 45%. This suggests that there is a growing capacity to accept change, but at present it is grudging and not strongly endorsed.

There are interesting demographic differences between those households who think change is a good thing or understand it has to happen and those that are neutral or prefer no change (

Table 7). The former group tend to be younger, are recent movers into the locality, are more likely to be renters, are in predominantly adult only households, are more likely to have plans to move in the next few years and prefer inner city locations. This suggests that the narrative for change and the benefits that well designed regenerative development can bring to a suburb and its residents needs to be better communicated to the stereotypical property-owning suburban households who prefer less development in their neighborhoods.

The next “planning for change” stage probes the extent to which property owners contemplating a future move are aware of or open to options of selling as a consortium of neighbors—becoming key actors in citizen-led urban redevelopment. While not commonplace, examples of this are being reported together with the value uplift achieved (

Figure 6). There is a capacity gap: a deficit of trusted and qualified brokers capable of engaging greyfield residents with the appropriate financial and legal instruments necessary to progress “kitchen table” discussions through to a positive outcome. This is not currently part of the business model in real estate agencies, local government, or among property developers. The survey revealed that one quarter of Sydney respondents were open to consolidating property for sale with neighbors—even higher (39%) for property they owned as an investment (

Table 8).

Finally, for those households indicating preparedness to sell their property as part of a consolidated precinct, 84% of those in Sydney would take the money and move somewhere else compared to 74% in Melbourne. This speaks to two options for greyfield precinct redevelopment: the traditional model involving a property developer only (for those who sell and move out), and one involving a form of “private-public/community” partnership where some or all of the residents form some type of joint venture for the co-development.

5. Conclusions

Achieving sustainable urban development will be a major challenge for cities in high-income liberal democratic societies. The acknowledged livability of Australia’s cities has been achieved at the expense of internationally high levels of resource consumption and carbon emissions. Planning more compact cities via regenerative retrofit provides a pathway for shrinking both urban and ecological footprints. Transformative change is required for transitioning low-density car-based cities from suburban to urban forms and fabrics however. One that needs to depart from over-reliance on high-rise and transit oriented development along transport corridors and around rail stations [

19,

20]. Housing infill involving medium density needs to play a major role here, and the challenging targets established for most of Australia’s largest cities reflects this. In the established suburbs where infill is targeted, KDR involving small lot subdivision is the current sub-optimal response. Greyfield precinct renewal that is focused on medium-density housing has emerged as a new planning model designed to increase housing supply and deliver a more sustainable setting for urban living. There are significant barriers in relation to the introduction of this urban innovation among the existing set of policies established within current metro planning strategies.

Employing conceptual frameworks from transition theory and transition management, the Greening the Greyfields project has been successful in demonstrating “proof of concept” for GPR to the state and local government planning agencies which will be responsible for implementing new zoning systems and medium development guidelines. Greyfield redevelopment having been incorporated as a new Policy Directive in PlanMelbourne 2017–2050 [

41] represents the first major step by a state government in Australia in enabling the emergence of a new model for urban infill development. How to accelerate and scale up GPR will be the next challenge, and it is here that transformative capacity needs to become a stronger focus in urban transition studies.

This paper has explored transformative capacity as it relates to the four key stakeholder groups central to the GPR transition: state and local governments, property developers and community residents. Each group exhibits capacity constraints. For state governments, leadership has been lacking when it comes to developing a narrative that can be understood by an entire metropolitan community regarding the need for change and then successfully communicating it. For local governments, better communication and engagement is required with state government to ensure vertical alignment between metropolitan strategies, municipal plans and local development approval processes. Top-down and bottom-up planning remains to be successfully “joined up”. As the critical interface to community, local government is significantly under-resourced to cope with what will be perceived as radical change.

For urban residents in the largest cities in Australia there appears to be a shift occurring in generational attitudes towards neighborhood change and medium-density living that could help drive urban intensification. Baby boomer households as well as those born before the end of the second world war are confronted with the looming pressures to vacate their under-occupied, ageing, detached housing in order to downsize into newer, more manageable and livable properties close to where they have been living. Meanwhile, the youngest cohorts (Gen Y/Millennials) provide strongest support for neighborhood change capable of delivering the supply of more varied types of dwelling at more affordable price points in more preferred accessible central locations. Ultimately, it will be the capacity of these ordinary city dwellers and property owners to recognize that there is a wave of urban change approaching that they can ride to their advantage—if they are engaged and there is a validated greyfield precinct regeneration business model that can be readily deployed. It would appear that a groundswell is beginning to emerge.