Acute Post-Prandial Cognitive Effects of Brown Seaweed Extract in Humans

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Initial Screening

2.3. Participants

2.4. Treatment

2.5. Cognitive and Mood Measures

2.5.1. Word Presentation

2.5.2. Immediate Word Recall

2.5.3. Simple Reaction Time (SRT)

2.5.4. Digit Vigilance

2.5.5. Choice Reaction Time (CRT)

2.5.6. Visual Analogue Scales (VAS)

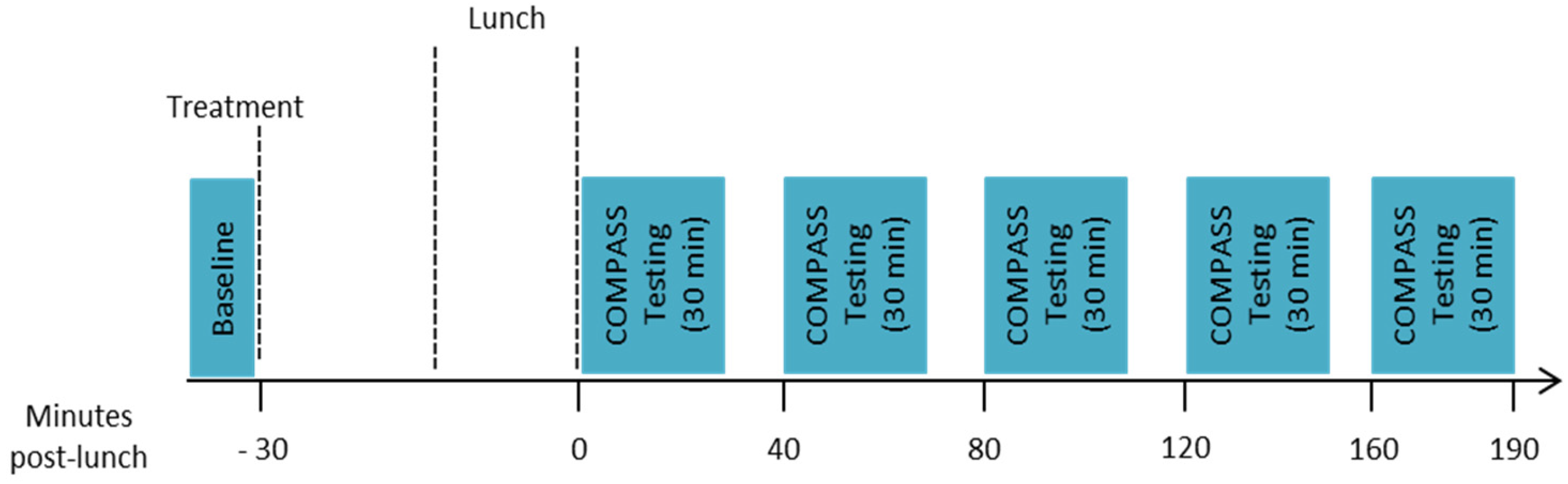

2.6. Procedure

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.2. Baseline Performance

3.3. Intervention Effects

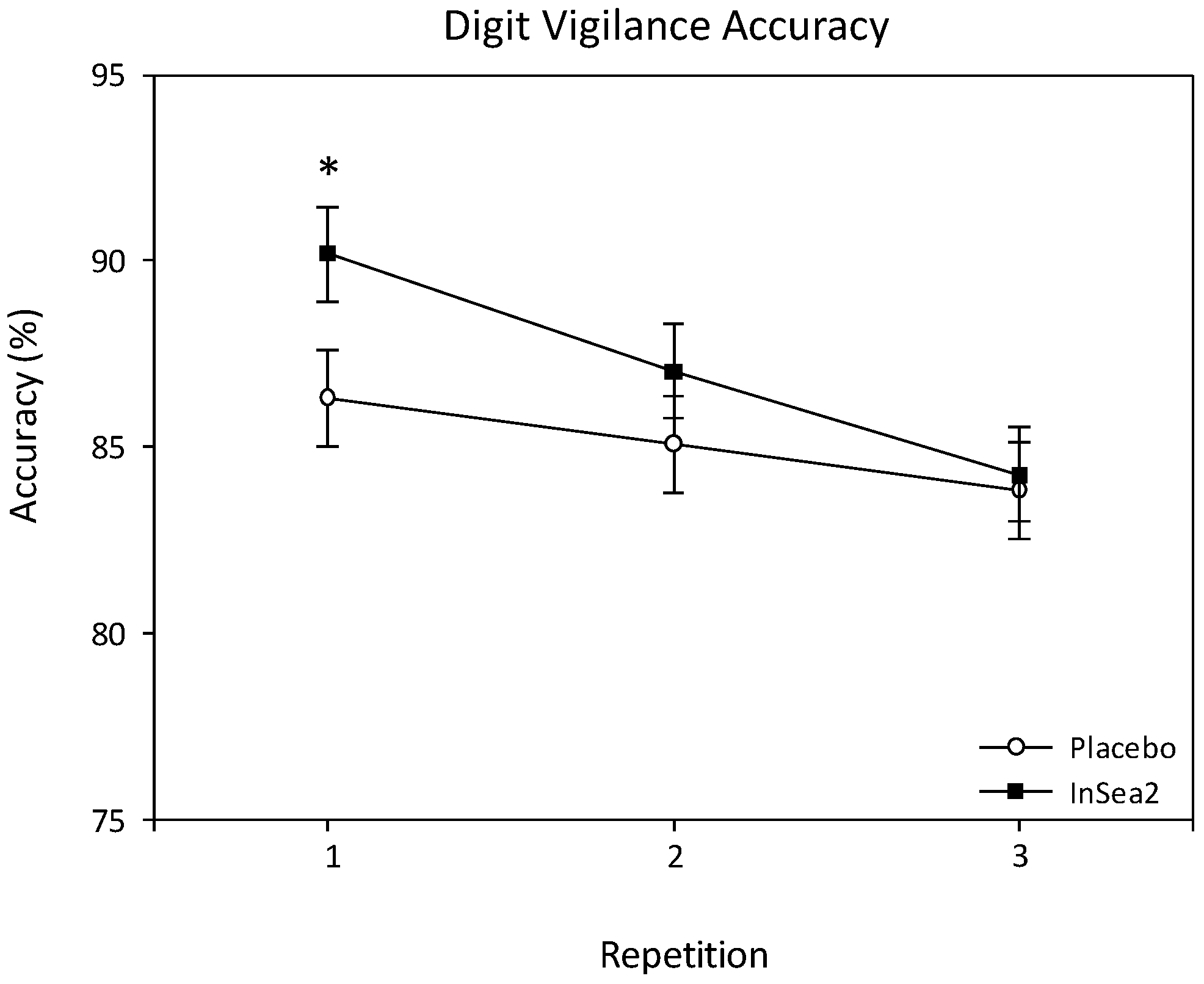

3.3.1. Digit Vigilance

3.3.2. Choice Reaction Time

3.3.3. Simple Reaction Time, Word Recall and VAS Mood Scale Ratings

3.4. Treatment Guess

3.5. Safety Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sunram-Lea, S.I.; Owen, L.; Finnegan, Y.; Hu, H.L. Dose-response investigation into glucose facilitation of memory performance and mood in healthy young adults. J. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 25, 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorck, I.; Liljeberg, H.; Ostman, E. Low glycaemic-index foods. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 83, S149–S155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippou, E.; Constantinou, M. The influence of glycemic index on cognitive functioning: A systematic review of the evidence. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.A.; Foster, J.K. The impact of a high versus a low glycaemic index breakfast cereal meal on verbal episodic memory in healthy adolescents. Nutr. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, S.B.; Bandelow, S.; Nute, M.L.; Morris, J.G.; Nevill, M.E. Breakfast glycaemic index and cognitive function in adolescent school children. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 1823–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogaard, M.; Abe, J.; Martineauclaire, M.F.; Svensson, B. α-amylases—Structure and function. Carbohydr. Polym. 1993, 21, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.; Ziak, M.; Zuber, C. The role of glucosidase ii and endomannosidase in glucose trimming of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Biochimie 2003, 85, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, H. Pharmacology of α-glucosidase inhibition. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 24, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolidis, E.; Lee, C.M. In vitro potential of ascophyllum nodosum phenolic antioxidant-mediated α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibition. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, H97–H102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lordan, S.; Smyth, T.J.; Soler-Vila, A.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P. The α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory effects of irish seaweed extracts. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 2170–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwosu, F.; Morris, J.; Lund, V.A.; Stewart, D.; Ross, H.A.; McDougall, G.J. Anti-proliferative and potential anti-diabetic effects of phenolic-rich extracts from edible marine algae. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantidos, N.; Boath, A.; Lund, V.; Conner, S.; McDougall, G.J. Phenolic-rich extracts from the edible seaweed, ascophyllum nodosum, inhibit α-amylase and α-glucosidase: Potential anti-hyperglycemic effects. J. Funct. Food. 2014, 10, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boath, A.S.; Stewart, D.; McDougall, G.J. Berry components inhibit α-glucosidase in vitro: Synergies between acarbose and polyphenols from black currant and rowanberry. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grussu, D.; Stewart, D.; McDougall, G.J. Berry polyphenols inhibit α-amylase in vitro: Identifying active components in rowanberry and raspberry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2324–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, G.J.; Dobson, P.; Smith, P.; Blake, A.; Stewart, D. Assessing potential bioavallability of raspberry anthocyanins using an in vitro digestion system. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 5896–5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, G.J.; Stewart, D. The inhibitory effects of berry polyphenols on digestive enzymes. Biofactors 2005, 23, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, M.C.; Anguenot, R.; Fillion, C.; Beaulieu, M.; Berube, J.; Richard, D. Effect of a commercially-available algal phlorotannins extract on digestive enzymes and carbohydrate absorption in vivo. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 3026–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbia, D.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Di Gangi, I.M.; Bogialli, S.; Caputi, V.; Albertoni, L.; Marsilio, I.; Paccagnella, N.; Carrara, M.; Giron, M.C.; et al. The phytocomplex from fucus vesiculosus and ascophyllum nodosum controls postprandial plasma glucose levels: An in vitro and in vivo study in a mouse model of nash. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradis, M.E.; Couture, P.; Lamarche, B. A randomised crossover placebo-controlled trial investigating the effect of brown seaweed (Ascophyllum nodosum and Fucus vesiculosus) on postchallenge plasma glucose and insulin levels in men and women. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stonehouse, W.; Conlon, C.A.; Podd, J.; Hill, S.R.; Minihane, A.M.; Haskell, C.; Kennedy, D. Dha supplementation improved both memory and reaction time in healthy young adults: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1134–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, F.L.; Kennedy, D.O.; Riby, L.M.; Haskell-Ramsay, C.F. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the effects of caffeine and l-theanine both alone and in combination on cerebral blood flow, cognition and mood. Psychopharmacology 2015, 232, 2563–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, A.W.; Haskell-Ramsay, C.F.; Kennedy, D.O.; Cooney, J.M.; Trower, T.; Scheepens, A. Acute supplementation with blackcurrant extracts modulates cognitive functioning and inhibits monoamine oxidase-B in healthy young adults. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 17, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.H.; Lamport, D.J.; Dodd, G.F.; Saunders, C.; Harkness, L.; Butler, L.T.; Spencer, J.P. Flavonoid-rich orange juice is associated with acute improvements in cognitive function in healthy middle-aged males. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 2021–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, K.H.; Pipingas, A.; Scholey, A.B. Investigation of the effects of solid lipid curcumin on cognition and mood in a healthy older population. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxf. Engl.) 2015, 29, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskell-Ramsay, C.F.; Stuart, R.C.; Okello, E.J.; Watson, A.W. Cognitive and mood improvements following acute supplementation with purple grape juice in healthy young adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 2621–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholey, A.B.; French, S.J.; Morris, P.J.; Kennedy, D.O.; Milne, A.L.; Haskell, C.F. Consumption of cocoa flavanols results in acute improvements in mood and cognitive performance during sustained mental effort. J. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 24, 1505–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyte, A.R.; Schafer, G.; Williams, C.M. Cognitive effects following acute wild blueberry supplementation in 7- to 10-year-old children. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 2151–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girouard, H.; Iadecola, C. Neurovascular coupling in the normal brain and in hypertension, stroke, and alzheimer disease. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 100, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iadecola, C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruitenberg, A.; den Heijer, T.; Bakker, S.L.; van Swieten, J.C.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Hofman, A.; Breteler, M.M. Cerebral hypoperfusion and clinical onset of dementia: The Rotterdam study. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 57, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brickman, A.M.; Khan, U.A.; Provenzano, F.A.; Yeung, L.K.; Suzuki, W.; Schroeter, H.; Wall, M.; Sloan, R.P.; Small, S.A. Enhancing dentate gyrus function with dietary flavanols improves cognition in older adults. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 1798–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, S.; Head, K.; Morris, P.; Macdonald, I. The effect of flavanol-rich cocoa on the fmri response to a cognitive task in healthy young people. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2006, 47, S215–S220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.O.; Wightman, E.L.; Reay, J.L.; Lietz, G.; Okello, E.J.; Wilde, A.; Haskell, C.F. Effects of resveratrol on cerebral blood flow variables and cognitive performance in humans: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover investigation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1590–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, Y.; Palmer, H.; Binns, M.A.; Jenkins, D.J.A.; Greenwood, C.E. Better cognitive performance following a low-glycaemic-index compared with a high-glycaemic-index carbohydrate meal in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamport, D.J.; Chadwick, H.K.; Dye, L.; Mansfield, M.W.; Lawton, C.L. A low glycaemic load breakfast can attenuate cognitive impairments observed in middle aged obese females with impaired glucose tolerance. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, C.R.; Taylor, H.A.; Kanarek, R.B.; Samuel, P. Effect of breakfast composition on cognitive processes in elementary school children. Physiol. Behav. 2005, 85, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micha, R.; Rogers, P.J.; Nelson, M. The glycaemic potency of breakfast and cognitive function in school children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamport, D.J.; Hoyle, E.; Lawton, C.L.; Mansfield, M.W.; Dye, L. Evidence for a second meal cognitive effect: Glycaemic responses to high and low glycaemic index evening meals are associated with cognition the following morning. Nutr. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torronen, R.; Kolehmainen, M.; Sarkkinen, E.; Mykkanen, H.; Niskanen, L. Postprandial glucose, insulin, and free fatty acid responses to sucrose consumed with blackcurrants and lingonberries in healthy women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torronen, R.; Sarkkinen, E.; Niskanen, T.; Tapola, N.; Kilpi, K.; Niskanen, L. Postprandial glucose, insulin and glucagon-like peptide 1 responses to sucrose ingested with berries in healthy subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torronen, R.; Kolehmainen, M.; Sarkkinen, E.; Poutanen, K.; Mykkanen, H.; Niskanen, L. Berries reduce postprandial insulin responses to wheat and rye breads in healthy women. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapwarobol, S.; Adisakwattana, S.; Changpeng, S.; Ratanawachirin, W.; Tanruttanawong, K.; Boonyarit, W. Postprandial blood glucose response to grape seed extract in healthy participants: A pilot study. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2012, 8, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamport, D.J.; Lawton, C.L.; Mansfield, M.W.; Dye, L. Impairments in glucose tolerance can have a negative impact on cognitive function: A systematic research review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2009, 33, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, C.M.; Freed, M.I.; Rood, J.A.; Cobitz, A.R.; Waterhouse, B.R.; Strachan, M.W.J. Improving metabolic control leads to better working memory in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desideri, G.; Kwik-Uribe, C.; Grassi, D.; Necozione, S.; Ghiadoni, L.; Mastroiacovo, D.; Raffaele, A.; Ferri, L.; Bocale, R.; Lechiara, M.C.; et al. Benefits in cognitive function, blood pressure, and insulin resistance through cocoa flavanol consumption in elderly subjects with mild cognitive impairment: The cocoa, cognition, and aging (cocoa) study. Hypertension 2012, 60, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastroiacovo, D.; Kwik-Uribe, C.; Grassi, D.; Necozione, S.; Raffaele, A.; Pistacchio, L.; Righetti, R.; Bocale, R.; Lechiara, M.C.; Marini, C.; et al. Cocoa flavanol consumption improves cognitive function, blood pressure control, and metabolic profile in elderly subjects: The cocoa, cognition, and aging (cocoa) study—A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.J.; Greenwood, C.E.; Winocur, G.; Wolever, T.M.S. Cognitive performance is associated with glucose regulation in healthy elderly persons and can be enhanced with glucose and dietary carbohydrates. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Benton, D.; Maconie, A.; Williams, C. The influence of the glycaemic load of breakfast on the behaviour of children in school. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingwersen, J.; Defeyter, M.A.; Kennedy, D.O.; Wesnes, K.A.; Scholey, A.B. A low glycaemic index breakfast cereal preferentially prevents children’s cognitive performance from declining throughout the morning. Appetite 2007, 49, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesnes, K.A.; Pincock, C.; Richardson, D.; Helm, G.; Hails, S. Breakfast reduces declines in attention and memory over the morning in schoolchildren. Appetite 2003, 41, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, D.; Ruffin, M.P.; Lassel, T.; Nabb, S.; Messaoudi, M.; Vinoy, S.; Desor, D.; Lang, V. The delivery rate of dietary carbohydrates affects cognitive performance in both rats and humans. Psychopharmacology 2003, 166, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reay, J.L.; Kennedy, D.O.; Scholey, A.B. Single doses of panax ginseng (G115) reduce blood glucose levels and improve cognitive performance during sustained mental activity. J. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 19, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowicz, D.; Wainstein, J.; Ahren, B.; Landau, Z.; Bar-Dayan, Y.; Froy, O. Fasting until noon triggers increased postprandial hyperglycemia and impaired insulin response after lunch and dinner in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1820–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona, G.; Ji, Y.; Anegboonlap, P.; Hotchkiss, S.; Gill, C.; Yaqoob, P.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Rowland, I. Gastrointestinal modifications and bioavailability of brown seaweed phlorotannins and effects on inflammatory markers. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ingredient | Function | Quantity per Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Seaweed | ||

| Brown Seaweed Powder | Active ingredient | 0 mg | 250 mg |

| Microcrystalline cellulose | Bulking agent | 191 mg | 100 mg |

| Calcium phosphate dibasic | Diluent | 287 mg | 150 mg |

| Magnesium stearate | Lubricant | 5 mg | 5 mg |

| Caramel | Color | 25 mg | 3 mg |

| Capsules composition: | |||

| Titanium dioxide Hypromellose | Opacifier Structure | 1.8 mg 94.3 mg | 0 mg 0 mg |

| Measure | Placebo | Seaweed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| N | 29 | - | 30 | - |

| Sex (% male) | 59 | - | 50 | - |

| Age (years) | 37.9 | ±16.9 | 33.1 | ±14.6 |

| Years in education | 17.5 | ±0.85 | 17.6 | ±0.66 |

| Caffeine consumption (mg/day) | 165.2 | ±118.0 | 170.3 | ±109.3 |

| Fruit and vegetables (portion/day) | 3.78 | ±1.17 | 4.37 | ±1.61 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 | ±3.05 | 24.2 | ±3.55 |

| Threshold | Odds Ratio | Confidence Interval (95%) | Significance (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥4 | 1.61 | (0.62, 4.22) | 0.33 |

| ≥5 | 2.9 | (1.16, 7.27) | 0.02 |

| ≥6 | 2.77 | (1.0, 7.81) | 0.05 |

| ≥7 | 3.41 | (1.21, 9.66) | 0.02 |

| Measure | Treatment | N | Repetition | Baseline | SE | Session Post-Lunch | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 40 min | 80 min | 120 min | 160 min | SE | ||||||

| Simple Reaction Time (ms) | Placebo | 29 | 1 | 295.7 | ±7.11 | 290.7 | 294.2 | 322.2 | 324.9 | 342.9 | ±24.0 |

| 2 | - | 324.4 | 370.9 | 380.5 | 375.8 | 394.6 | |||||

| 3 | - | 425 | 406.5 | 416.8 | 421.9 | 391.8 | |||||

| InSea2® | 30 | 1 | 276.9 | ±6.39 | 293.4 | 305.7 | 323.7 | 322.3 | 333.4 | ±23.6 | |

| 2 | - | 316 | 346.8 | 342.2 | 375.8 | 375.5 | |||||

| 3 | - | 359.8 | 390.9 | 401.1 | 443.4 | 381.6 | |||||

| Digit Vigilance Accuracy (%) | Placebo | 29 | 1 | 89.12 | ±2.61 | 89.5 | 88.8 | 85.4 | 86.4 | 81.5 | ±1.91 |

| 2 | - | 89.4 | 86 | 83.4 | 85.1 | 81.7 | |||||

| 3 | - | 87.1 | 84.3 | 80.5 | 82.8 | 84.6 | |||||

| InSea2® | 30 | 1 | 93.33 | ±1.63 | 91.6 | 91.2 | 89.3 | 90.4 | 88.4 | ±1.88 | |

| 2 | - | 90 | 87.4 | 88.1 | 86.9 | 82.9 | |||||

| 3 | - | 87.6 | 84.6 | 84.7 | 82.5 | 82 | |||||

| Digit Vigilance Reaction Time (ms) | Placebo | 29 | 1 | 434.7 | ±8.89 | 426.9 | 439.6 | 449.8 | 445.7 | 448.8 | ±5.27 |

| 2 | - | 437 | 449 | 446.6 | 453.6 | 450.3 | |||||

| 3 | - | 438.8 | 451.6 | 453.8 | 453.5 | 451.6 | |||||

| InSea2® | 30 | 1 | 413.4 | ±5.28 | 439.3 | 444.7 | 449.4 | 448.7 | 447.3 | ±5.18 | |

| 2 | - | 448.6 | 451.5 | 456 | 456.6 | 458 | |||||

| 3 | - | 448.2 | 464.7 | 463.6 | 459.2 | 459.6 | |||||

| Digit Vigilance False Alarms (Number) | Placebo | 29 | 1 | 1.79 | ±0.43 | 2.15 | 2.84 | 3.74 | 3.5 | 3.81 | ±0.49 |

| 2 | - | 2.39 | 3.39 | 4.01 | 3.43 | 4.43 | |||||

| 3 | - | 3.7 | 4.5 | 4.67 | 4.19 | 4.6 | |||||

| InSea2® | 30 | 1 | 1.5 | ±0.36 | 2.22 | 2.32 | 3.05 | 2.82 | 3.09 | ±0.48 | |

| 2 | - | 2.09 | 2.69 | 3.25 | 3.39 | 3.99 | |||||

| 3 | - | 3.52 | 3.95 | 3.45 | 3.59 | 4.39 | |||||

| Choice Reaction Time Accuracy (%) | Placebo | 29 | 1 | 97.6 | ±0.36 | 96.7 | 96.6 | 95.6 | 95.9 | 96.2 | ±0.55 |

| 2 | - | 96.6 | 96.4 | 96.7 | 95.2 | 95.8 | |||||

| 3 | - | 96.5 | 95.8 | 96.2 | 95.3 | 95.4 | |||||

| InSea2® | 30 | 1 | 96.2 | ±0.73 | 96.3 | 95.9 | 96 | 96 | 95.9 | ±0.54 | |

| 2 | - | 95.7 | 95.9 | 96.1 | 95.5 | 95.9 | |||||

| 3 | - | 95.3 | 95.4 | 94.4 | 95.7 | 96.2 | |||||

| Choice Reaction Time (ms) | Placebo | 29 | 1 | 436.4 | ±14.6 | 425.1 | 443.2 | 466 | 474.4 | 475.9 | ±21.1 |

| 2 | - | 473.9 | 476.6 | 516.3 | 506.7 | 524.8 | |||||

| 3 | - | 472.4 | 498.7 | 479.8 | 523.2 | 485 | |||||

| InSea2® | 30 | 1 | 406.3 | ±7.50 | 429.5 | 448.5 | 457.4 | 468 | 478 | ±20.7 | |

| 2 | - | 451.9 | 478.8 | 487.5 | 524.4 | 489.8 | |||||

| 3 | - | 477.9 | 513.5 | 498 | 559.6 | 496.6 | |||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haskell-Ramsay, C.F.; Jackson, P.A.; Dodd, F.L.; Forster, J.S.; Bérubé, J.; Levinton, C.; Kennedy, D.O. Acute Post-Prandial Cognitive Effects of Brown Seaweed Extract in Humans. Nutrients 2018, 10, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010085

Haskell-Ramsay CF, Jackson PA, Dodd FL, Forster JS, Bérubé J, Levinton C, Kennedy DO. Acute Post-Prandial Cognitive Effects of Brown Seaweed Extract in Humans. Nutrients. 2018; 10(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010085

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaskell-Ramsay, Crystal F., Philippa A. Jackson, Fiona L. Dodd, Joanne S. Forster, Jocelyn Bérubé, Carey Levinton, and David O. Kennedy. 2018. "Acute Post-Prandial Cognitive Effects of Brown Seaweed Extract in Humans" Nutrients 10, no. 1: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010085

APA StyleHaskell-Ramsay, C. F., Jackson, P. A., Dodd, F. L., Forster, J. S., Bérubé, J., Levinton, C., & Kennedy, D. O. (2018). Acute Post-Prandial Cognitive Effects of Brown Seaweed Extract in Humans. Nutrients, 10(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010085